Abstract

Cell adhesion and migration are important features in tumor invasion, being mediated in part by integrins (extracellular matrix receptors). Integrins are significantly decreased in human prostate cancer. An exception is α6 integrin (laminin receptor) which persists during prostate tumor progression. We have selected high (DU-H) and low (DU-L) expressors of α6 integrin from a human prostate tumor cell line, DU145, to assess experimentally the importance of α6 integrin in tumor invasion. DU-H cells exhibited a four-fold increased expression of α6 integrin on the surface compared to DU-L cells. Both cell types contained similar amounts of α3 and α5 integrin. The DU-H cells contained α6 subunits complexed with both the β1 and β4 subunits whereas DU-L cells contained α6 complexed only with β4. DU-H cells were three times more mobile on laminin as compared to DU-L, but adhered similarly on laminin. Adhesion and migration were inhibited with anti-α6 antibody. Each subline was injected intraperitoneally into SCID mice to test its invasive potential. Results showed greater invasion of DU-H compared to DU-L cells, with increased expression of α6 integrin on the tumor at the areas of invasion. These data suggest that α6 integrin expression is advantageous for prostate tumor cell invasion.

Keywords: basement membrane, cell adhesion, extracellular matrix, laminin, prostate cancer

Introduction

Cell adhesion and migration are important features that influence the ability of malignant cells to invade and metastasize to distant tissues [1]. Cell adhesion to the extracellular matrix (ECM) is mediated largely through the integrins, a group of heterodimeric transmembrane proteins [2]. These heterodimers are formed by a combination of an α and a β subunit. There are currently 14 α and 8 β subunits [2, 3]. Ligand specificity is mainly defined by this subunit combination though it may depend also on the cell type and environmental factors [2].

Cell binding to laminin (LM), a major component of the basal lamina, has been implicated in the invasive and metastatic processes [1, 4]. Laminin binding is mediated through several integrins, primarily α6β1 and α6β4 [5–8], but also α7β1, α3β1, α2β1, and α1β1 have been implicated in certain cell types [9–12].

The α6 integrin subunit comprises 1050 amino acids synthesized as a single chain, which is cleaved into a heavy and a light chain [13, 14]. As a result of alternative splicing, α6-A and α6-B variants are formed, differing from each other only in their short cytoplasmic tail [13, 15].

Integrin α6β1 is expressed in a wide variety of cells, including epithelial and endothelial cells, where it usually shows a polarized distribution to the basolateral surface [16–18]. This integrin is linked indirectly to the actin cytoskeleton. In contrast, integrin α6β4 is localized to hemidesmosomes in several epithelia [19, 20], where it is linked to the cytokeratin cytoskeletal network [21, 22].

The role of α6 integrins in tumor invasion and metastasis has been assessed from different standpoints [23–25]. For example, human melanoma cells injected into nude mice were diminished in their metastatic potential by anti-α6 antibodies, probably by decreasing the rate of cellular retention in the lungs [26]. Neoplastic transformation of fibroblasts [27] or chemically transformed cells [28] resulted in an increased expression of α6 integrin. Histopathologically, the picture is varied. Tumors such as human breast and renal carcinomas are reported to show a decrease of several types of integrins including α6 and β4 and to show an unpolarized pattern [29–32]. On the other hand, breast carcinomas that preserve α6 integrin expression are associated with reduced survival [33], suggesting an important role in tumor progression. Other human tumors show an increase in α6 but usually in a non-polar distribution: pancreatic carcinoma, head and neck squamous cell carcinomas, seminomas, and melanomas [34–38]. In prostate cancer, we have found previously that several of the integrins are down-regulated [39]. However, the α6 integrin persists during tumor progression and in some cases increases its expression in an altered unpolarized pattern on the tumor cell surfaces [39, 40]. The β4 integrin subunit is undetectable in primary prostate carcinoma, suggesting that the α6β1 heterodimer is predominant in progressing tumors. Integrin α6 may be increased in lymph-node metastatic lesions, suggesting that it could play a role in this process [40].

In this study we have analysed the role of α6 in the invasive phenotype of human prostate carcinoma cells (DU145) by selecting cell subpopulations with high and low surface expression of the α6 integrin. We have used these subpopulations to compare the effect of the α6 integrin on several invasive features: cell adhesion and migration in vitro, breaching of a basal lamina and migrating through the stroma in vivo.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

DU145 human prostate carcinoma [41] and JAR choriocarcinoma [42] cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD, USA). DU145 cells were originated from a prostate carcinoma brain metastasis. Cells were maintained in IDMEM medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (all from Gibco) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air, 5% CO2.

Antibodies

The GoH3 anti-α6 integrin antibody was obtained from Accurate Chemical & Scientific (Westbury, NY, USA). Anti-β1 (P4C10), anti-α5 (P1D6), anti-β4 (3E1) and anti-α3 (P1B5) integrin antibodies were obtained from Gibco BRL (Gaithersburg, MD, USA).

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)

DU145 cells in suspension were incubated with GoH3 anti-α6 antibody (1:100) for 30 min at 4°C, washed several times with medium, then incubated with FITC-conjugated anti-rat antibody for 30 min at 4°C, and washed several times. Cells were selected with a FACS starplus cell sorter (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) for their higher or lower α6 expression by collecting the cells from the 2% ‘tails’ as determined by FACS. The sorted cells were expanded in vitro and resorted seven times following the same procedure.

Biotinylation and immunoprecipitation of cell surface integrins

Using modifications from previous protocols [43, 44], cells were grown to early confluency in 100 mm tissue culture dishes and washed with HEPES buffer (20 mm HEPES, 130 mm NaCl, 5 mm KCl, 0.8 mm MgCl2, 1.0 mm CaCl2, pH 7.45). The cells were then incubated with 2 ml of HEPES buffer supplemented with Sulfosuccinimidyl hexanoate conjugated biotin (500 µg/ml) (NHS-LC-Biotin, Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) to label cell surface proteins for 30 min at 4°C. Cells were washed three times and lysed in lysis buffer (PBS containing 1% NP-40, 10 mm EDTA and antiproteases: PMSF, 2 mm; leupeptin and aprotinin, 1 µg/ml). The extract was briefly sonicated and centrifuged to remove insoluble material, then precleared with protein G-Sepharose (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden). Anti-integrin antibodies (5 µl/ml) were added and incubated overnight at 4°C. The integrin/antibody complexes were immunoprecipitated with protein G-Sepharose, washed with lysis buffer three times and eluted by boiling in sample buffer for 5 min. Proteins were separated in 7.5% SDS-PAGE, electrotransferred to nitrocellulose, incubated with peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin and visualized by chemiluminescence (ECL Western Blotting Detection System, Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL, USA).

Microscopy

For indirect immunofluorescence, cells were grown on glass coverslips, washed with PBS, incubated with anti-α6 antibody for 30 min at 4°C, washed and then incubated with FITC-conjugated anti-rat antibody for 30 min at 4°C. After the incubation, the cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde and the coverslips mounted onto the slides with Elvanol. The preparations were analysed by confocal fluorescence microscopy using a Zeiss LSM10 instrument using a scan time of 16 s.

Fresh frozen samples of mouse diaphragm were obtained at necropsy and snap frozen at −140°C in isopentane, supercooled in liquid nitrogen and sectioned on a cryostat and immunoreacted with antibody specific for α6 integrin. Additional specimens fixed in 10% formalin and paraffin-embedded were sectioned, rehydrated and stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Adhesion assays

ELISA Multiwell plates (96) were coated with 10 µg or 5 µg of EHS laminin or fibronectin (Collaborative Research, Bedford, MA, USA), respectively. Cells (3 × 104) were overlaid on coated wells and incubated with or without antibody for 1 h at 37°C. Unattached cells were removed by washing three times with HEPES buffer. Cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde and dried. Attached cells were stained with 0.1% Crystal Violet solution, washed, and the retained dye eluted with Sorensen solution (9 mg of trisodium citrate in 305 ml of H2O, 195 ml of 0.1 n HCl and 500 ml of ethanol). Absorbance at 540 nm was determined with an ELISA reader.

Cell migration assays

Non-tissue culture Petri dishes were coated with laminin (Collaborative Research) at different concentrations (0–20 µg/cm2) for 2h and then blocked with 1% denatured albumin for 2 h. The cells were added and allowed to attach overnight. The Petri dish was sealed and transferred to a heated stage microscope (Nikon) adapted for video microscopy using an Hitachi solid state camera interfaced with a Macintosh Quadra 800 computer. Random cell migration was determined by measuring displacement of cell centroids as a function of time. Seventy to 100 cells were analysed for each condition.

Tumor growth in SCID mice

Male SCID mice, 5–6 weeks old, were innoculated intraperitoneally with 5–20 × 106 cells resuspended in PBS. Necropsy was done 31 days later. The diaphragm was dissected out and weighed. The specimen was divided with portions fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and processed according to standard procedures for hemotoxylin and eosin staining. An additional portion was snap frozen, sectioned in a cryostat and processed for indirect immunofluorescence. Several transverse sections were examined for breaching of mesothelial basement membrane and the depth of diaphragm invasion.

Results

Selection of stable subpopulations of DU145 cells expressing high and low amounts of α6 integrin

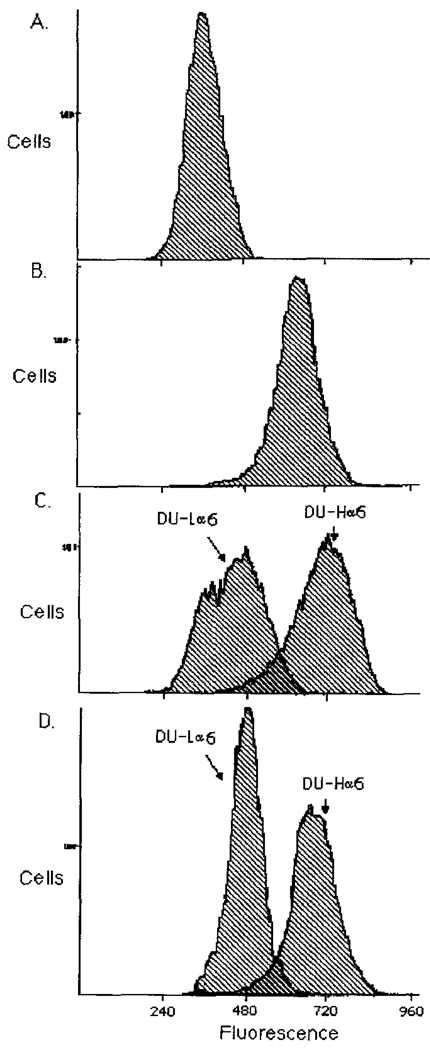

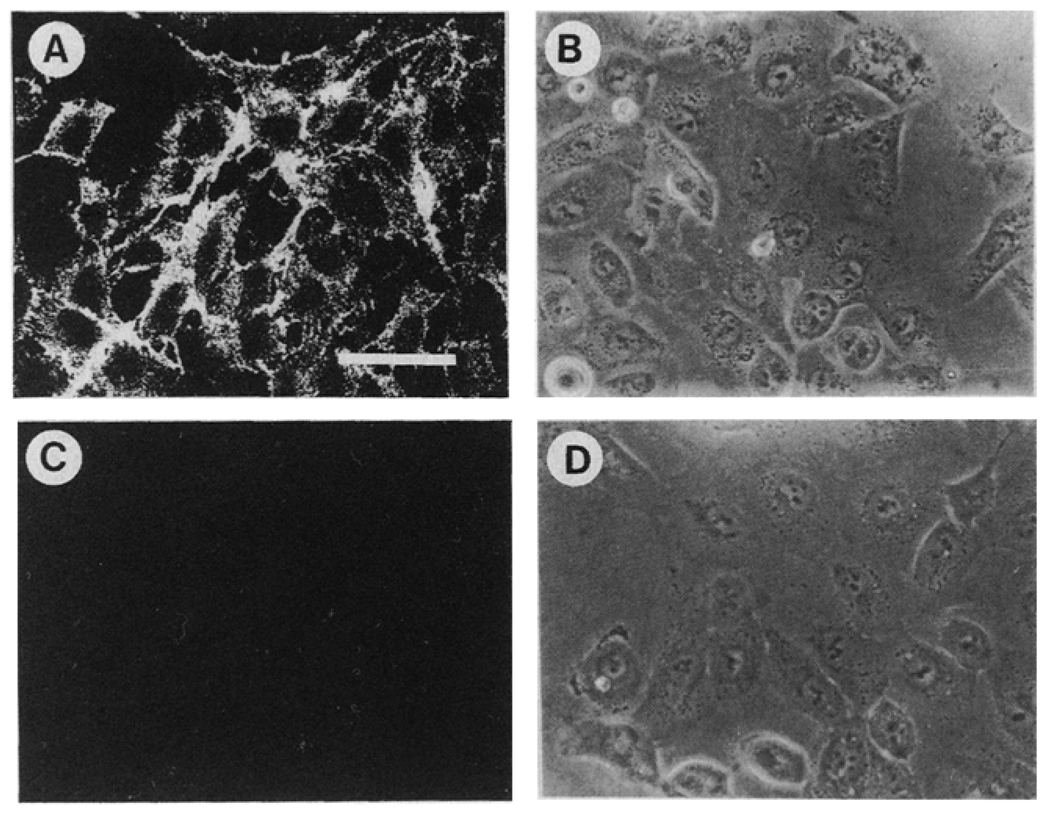

Cell subpopulations of DU145 human prostate carcinoma cells containing high and low amounts of α6 integrin were selected by repeated sorting in a FACS system (Figure 1). After seven sortings, the high α6 integrin expressors (DU-H) showed an approximate four-fold increase in surface expression of α6 as compared to the low α6 integrin expressors (DU-L), as estimated by the difference in the fluorescence mean channel of the two populations (representing a log scale, there is a doubling in the fluorescence intensity for each 75 channel difference approximately) (Figure 1C). Two months later, the cell population maintained the selected phenotype indicating that a stable difference in integrin expression was obtained (Figure ID). The distribution of α6 integrin in DU-H cells was focal, intracellular and intercellular while that in DU-L cells was mostly negative (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Selection of high (DU-H) and low (DU-L) expressers of α6 integrin and FACS analysis. Cells were selected for their high or low α6 expression by collecting the cells from the 2% ‘tails’ as determined by fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS). Sorted cells were expanded in vitro and resorted seven times following the same procedure. Fluorescence is represented in channels. Approximately 75 channels constitute a doubling of fluorescence intensity. (A) Fluorescent cell distribution of negative control cells (reacted with secondary antibody only). (B) Fluorescent cell distribution of pre-sorted DU145 cells. (C) Fluorescent cell distribution of high and low α6 integrin expressers after seven rounds of sorting. (D) Two months after the last sort.

Figure 2.

Distribution of α6 integrin by indirect immunofluorescence microscopy. Cells were grown on coverslips, washed with PBS, incubated with anti-α6 antibody (GoH3) for 30 min at 4°C, washed and then incubated with FITC-conjugated anti-rat antibody for 30 min at 4°C, then fixed with 4% formaldehyde and mounted with Elvanol. Preparations were analysed by confocal fluorescence microscopy (A and C) or phase contrast microscopy (B, D). (A and B) DU-H. (C and D) DU-L. Bar = 50 µm.

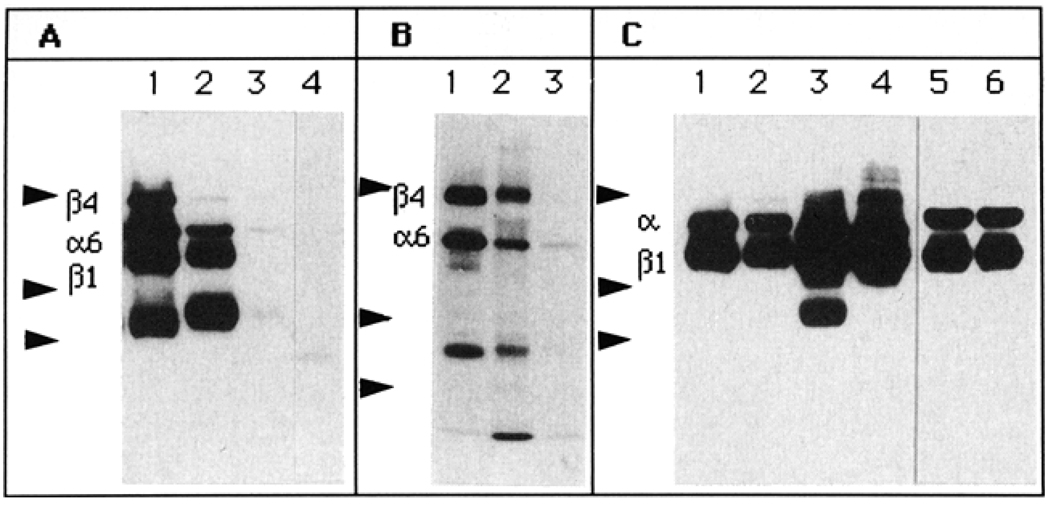

The DU-H cells express both α6β1 and α6β4 integrins and the DU-L cells only express α6β4

The integrin composition of the high and low α6 integrin expressors was determined by immunoprecipitation of surface biotinylated integrins and analysis by gel electrophoresis. The JAR choriocarcinoma cell line was used as a positive control (Figure 3A, lane 1; Figure 3B, lane 1). The DU-H cells showed higher amounts of α6 than the DU-L cells, consistent with FACS analysis (Figure 3A, lanes 2 and 3). The composition of the heterodimer was different between the cell lines. The high expressors contained both β1 and β4 integrin chains coupled to α6; in contrast, the DU-L cells contained only the β4 chain coupled to the α6 chain. A five-fold increase in the amount of immunoprecipitated α6 integrin from the DU-L cells still contained no β1 (data not shown). Lower molecular weight bands (approximately 80 kDa) were co-immunoprecipitated with the anti-α6 antibody in the three cell lines. These bands have not yet been identified but may probably represent proteolytic products of α6 integrin [45, 46]. Similar cleavage products of integrins have also been found in α4 integrins [47]. Immunoprecipitation of the β4 integrin was consistent with the α6 immunoprecipitations.

Figure 3.

Biotinylation and immunoprecipitation of cell surface integrins from DU-H and DU-L cells. Integrins were immunoprecipitated from surface biotinylated cells as described in Materials and methods. The proteins were separated in 7.5% SDS-PAGE, electrotransferred to nitrocellulose, incubated with peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin and visualized by chemiluminescence. (A) α6 integrin was immunoprecipitated with GoH3 antibody (lanes 1–3) or control IgG antibody (lane 4). Lane 1, JAR cells (used as a positive control); lanes 2 and 4, DU-H; lane 3, DU-L. (B) β4 integrin was immunoprecipitated with 3E1 antibody (lanes 1–3). Lane 1, JAR cells; lane 2, DU-H; lane 3, DU-L. (C) α5 (lanes 1 and 2), β1 (lanes 3 and 4), and α3 (lanes 5 and 6) integrins were immunoprecipitated with P1D6, P1D6 and P1B5 antibodies, respectively. Lanes 1, 3, 5, DU-H; lanes 2, 4, 6, DU-L. Arrowheads (top to bottom): protein molecular weight markers of 200, 97 and 68 kDa.

Both cell sublines express similar amounts of α3, α5 and β1

Other integrins were immunoprecipitated to determine if the selection was specific for the α6 integrin. Figure 3C indicates that the α3 (lanes 1 and 2), α5 (lanes 3 and 4) and β1 (lanes 5 and 6) integrin content was similar in both cell sublines, confirming that our selection for differential expression was restricted to the α6 integrin.

Both cell sublines attach to laminin and fibronectin to a similar extent but by different mechanisms

The consequences of α6 expression in the selected sublines was assessed by three different functional assays. These included determining changes in cell adhesion to laminin or other ECM molecules, changes in cell migration and invasion of the cells through a SCID mouse diaphragm in vivo.

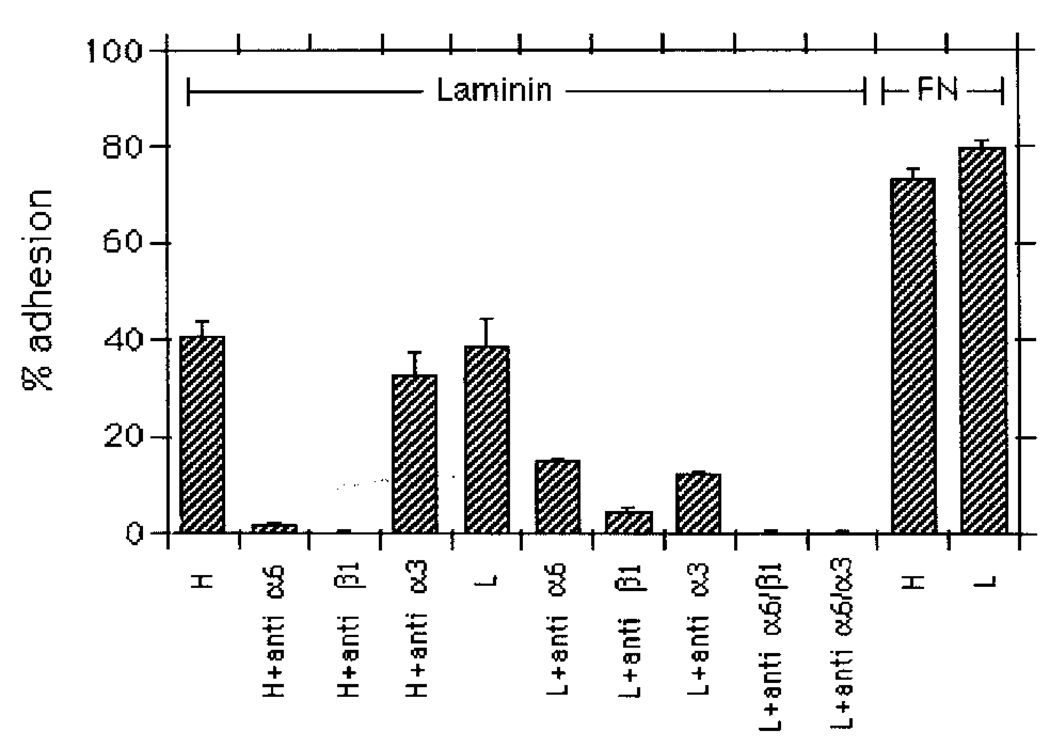

The extent of cellular adhesion to laminin was similar for both cell populations (Figure 4). However, the adhesion of the DU-H cells depended completely on the α6 integrin since the anti-α6 antibody inhibited adhesion to laminin. On the other hand, the DU-L cells were only partially inhibited with the anti-α6 antibody. We investigated which other integrins participated in the DU-L cell adhesion to laminin and found that a β1 integrin (probably α3β1) was participating in laminin adhesion. A partial inhibition of DU-L cells to laminin occurred by incubation of the cells with either β1 or α3 antibodies. The anti-α6 antibody combined with either anti-β1 or anti-α3 inhibited adhesion to laminin completely, confirming the sufficiency of the interaction. The DU-H cells were inhibited by an anti-β1 antibody but not by an anti-α3 antibody. The adhesion to fibronectin was similar in both cell sublines.

Figure 4.

Attachment of DU-H and DU-L cells to laminin and fibronectin. Cells were tested for their adhesive ability on laminin and fibronectin in the presence or absence of specific antibodies as described in Materials and methods. Results are expressed as a percentage of the total number of applied cells which were attached after 1 h of incubation. H, DU-H; L, DU-L; anti-α6, anti-α6 antibody (GoH3, 20 µl/ml); anti-β1, anti-β1 antibody (P4C10, 5 µl/ml); anti-α3, anti-α3 antibody (P1B5, 10 µl/ml); FN, fibronectin.

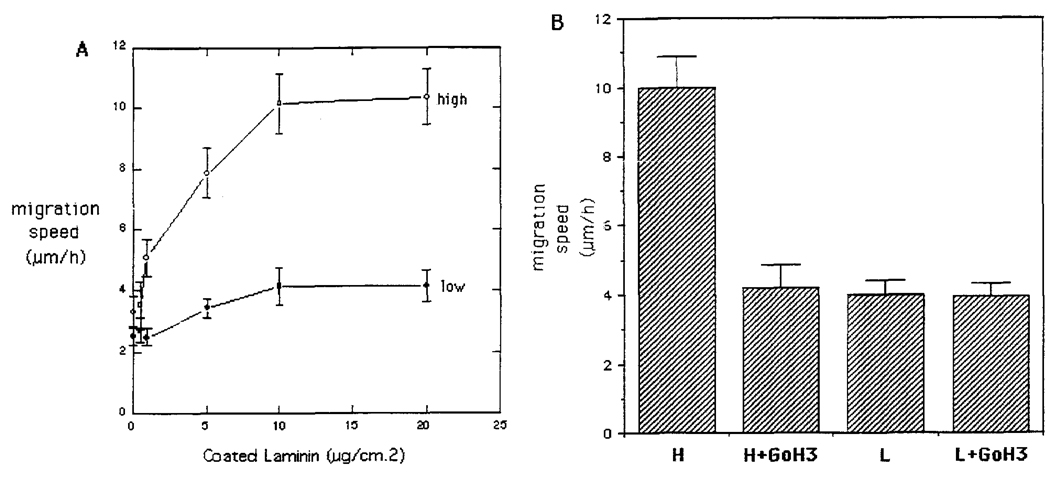

The high α6 integrin expressors migrate faster than α6 low expressors on laminin

The importance of α6 integrin in cell movement on laminin was assessed by comparing the random migration speeds of the high and low α6 integrin sublines. Videomicroscopic analysis of cells moving on different amounts of coated laminin (Figure 5A) showed that the low α6 expressors moved 2.5-fold slower than the high expressors. The involvement of α6 was confirmed by inhibiting cell movement with anti-α6 antibody (Figure 5B). The DU-H cells were largely inhibited, most of the cells rounding up soon after the antibody addition. The remaining movement seen here was probably due to cell rolling more than ameboid movement, as observed in time-lapse video recording. The α6 antibody alone or the α3 antibody alone did not have any effect on the low expressors, which preserved both their speed and spreading.

Figure 5.

Migration of DU-H cells and DU-L cells on laminin. Videomicroscopic analysis of cell migration was performed on cells grown in laminin-coated dishes (0–20 µg/cm2). Random cell migration was determined by measuring the displacement of centroids as a function of time. Seventy to 100 cells were analysed for each condition. (A) Random migration of DU-H and DU-L on laminin at different concentrations. (B) Inhibition of migration with anti-α6 antibody (20 µl/ml) of DU-H cells and DU-L cells on laminin (10 µg/cm2).

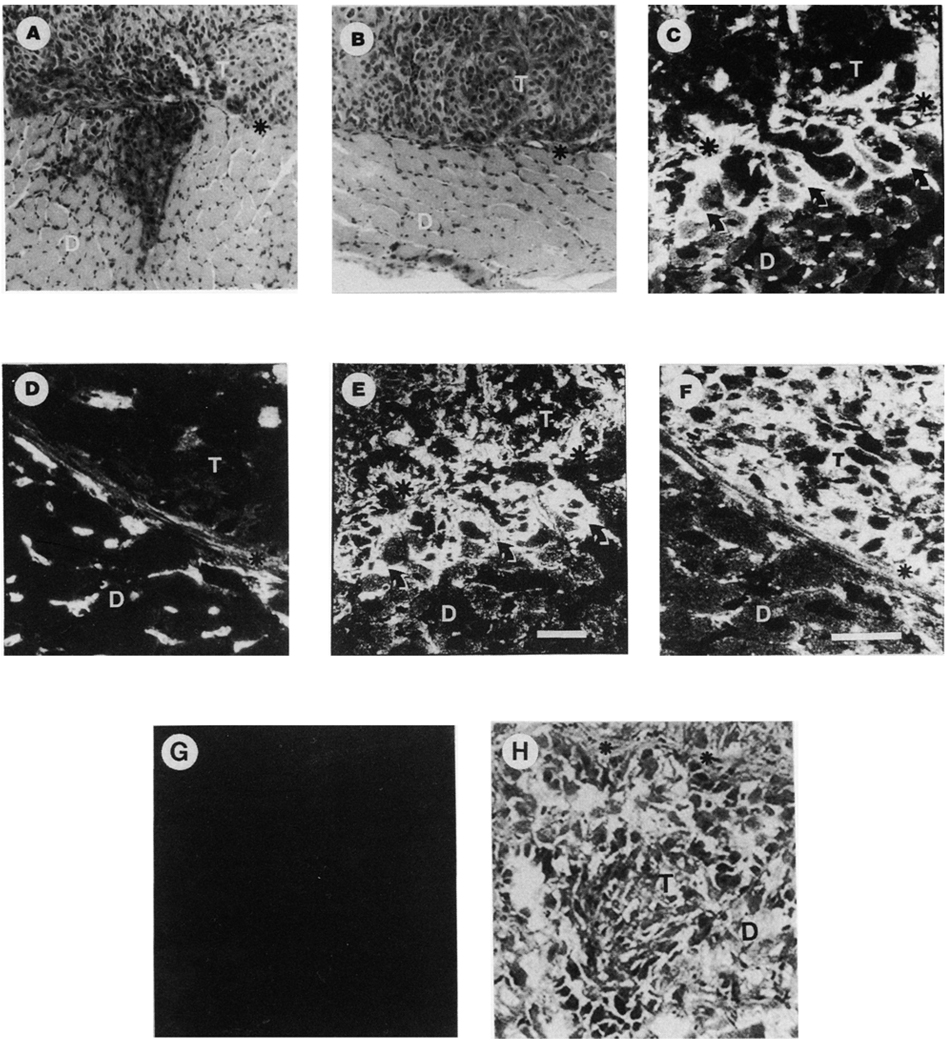

Increased invasive ability of DU-H tumors into the mouse diaphragm

The α6 sublines were assessed in their invasive ability in SCID mice by determining their capacity to breach the diaphragm basement membrane and invade its stroma. This model is practical as it allows evaluation of the frequency of basement membrane breaching and of the depth of invasion by the tumor (Figure 6A and B). Initial experiments indicated that the low α6 expressors showed an increased proliferation rate in comparison to the high α6 expressors after injection into the mice (data not shown). Accordingly, the number of cells injected into the mice was adjusted to achieve a similar tumor burden and size on the diaphragm. At a similar tumor burden, the high expressors resulted in an increased invasion (Table 1, Figure 6A). The increased invasion was characterized by multiple basement membrane breaching points and penetration into the underlying muscle in 80% of the cases. The cells were observed between the muscle fibers, suggesting a migration path along the surface of the muscle. The low expressors showed superficial invasion in one case (20%) and were negative in the other mice (Table 1, Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Invasion of SCID mouse diaphragm by DU-H and DU-L cells. Cells were injected intraperitoneally in SCID mice and grown for 31 days. Diaphragm samples were fixed in formalin or frozen, sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. (A) Highly invasive tumor (DU-H). (B) Non-invading tumor (DU-L). (C–G) Indirect immunofluorescent analysis of DU-H and DU-L tumors. Frozen sections of tumor-invaded diaphragms from innoculated SCID mice with DU-H (C, E) and DU-L (D, F) were immunostained with anti-α6 integrin (C, D) or human anti-keratin (E, F) antibodies. As a control, contiguous frozen sections of DU-H tumors were stained with the secondary antibody only (G) and hematoxylin and esoin stain (H). Asterisks denote the normal diaphragm boundaries. T, tumor; D, diaphragm. Arrows indicate the invasive edges of the tumor. Bars = 50 µm. Note the invasion edge of the tumor is surrounding muscle fibers and expressing α6 integrin.

Table 1.

Invasive ability of DU-H and DU-L cells injected into SCID mice

Penetration and migration through the diaphragm.

Diaphragm with tumor was dissected and weighed (mg). Tumor weight=total diaphragm with tumor weight–mean weight of normal diaphragm. The mean weight of a normal diaphragm was 80 mg.

Microscopic analysis of the frozen sections of the mouse diaphragm by indirect immunofluorescence indicated that the tumor arising from the DU-H cells was positive for α6 (Figure 6C and E). Of particular interest was the increased expression of the integrin on the surface of the cells at the invasion sites as compared to the expression level within the tumor mass. Analysis of the digital images by quantitation of the pixel density indicated a three-fold elevation in expression (data not shown). The DU-L cells showed also moderate positivity for α6 (Figure 6D and F) but no evidence of a preferential pattern of expression along the boundaries of the diaphragm was noted.

Discussion

We have investigated the influence that α6 integrin has on the invasive potential of prostate tumor cells. We chose as a model a human prostatic carcinoma cell line, DU145, which was previously characterized for its adhesive properties and integrin profile [45]. We selected cell populations from the original cell line which contained high and low surface expression of the α6 integrin. The high α6 integrin expressors (DU-H) showed a four-fold increase in α6 as compared to the low α6 expressors (DU-L). The selected phenotype continues to be stable 2 months after the selection.

A biochemical analysis of the integrin composition showed that DU-H cells expressed both α6β1 and α6β4 integrins in contrast to DU-L which only expressed lower levels of α6β4. Yet both cell sublines produced similar amounts of α3, α5 and β1 integrins, showing that the integrin difference was restricted to α6, mainly α6β1.

The ability to adhere to laminin was similar in both cell sublines, suggesting that either lower amounts of α6 integrins can accomplish attachment, or that other laminin receptors may compensate in attachment for the low α6 expression. The latter seems likely as suggested by antibody inhibition assays. DU-L cells were only partially inhibited with anti-α6 integrin antibody, suggesting the participation of other adhesion molecules. Further investigation showed that α3 integrin was also involved in the adhesion of DU-L to laminin as it was possible to partially inhibit adhesion with anti-α3 antibody. Taking into consideration that the combination of anti-α6 and anti-α3 antibodies (or anti-α6 and anti-β1) could inhibit most of the adhesion in the low expressors, one may conclude that adhesion to laminin is predominantly mediated through α6β4 and α3β1 integrins in DU-L cells. Integrin cooperation in laminin binding has been found in other cell lines as well [48–50]. It is not clear why α3 does not have a laminin binding role in the high expressors, but may reflect a competition for intracellular factors that mediate the response to laminin binding or the connection of the integrin to the cytoskeleton. For example, a recent study shows that chimeric integrins (with functional cytoplasmic tails but non-functional chimeric extracellular domains) might inhibit endogenous integrin receptor function, presumably by interacting with cytoplasmic components critical for endogenous integrin function [51]. In an analogous fashion, α6 integrin might compete with α3 integrin for similar cytoplasmic factors.

In contrast to adhesion, migration on laminin was affected by α6 integrin expression in these sublines. DU-H cells showed an increased random migration speed on laminin in relation to DU-L cells. Since the cell sublines differ primarily in the presence of α6β1, these data suggest that α6β1 increases cell migration on laminin. The inhibition of migration with α6 antibodies in the high expressors indicates a strong dependence on the α6 integrins. Although there is only half the inhibition of the apparent migration speed after antibody treatment, the high expressors assumed a round morphology. The remaining measured cellular displacement may be attributed to an integrin-independent cell rolling more than the extension of pseudo or filopodia as documented by time-lapse video-microscopy. The low expressors, though showing a slow migration speed, were not altered by anti-α6 antibodies either in their migration or in their spreading, suggesting that α6β4 may not participate in DU-L cell migration and that other cell adhesion molecules could be taking part in these actions. In this case, anti-α3 did not change the DU-L migration speed.

Previous studies have suggested the participation of α6β1 in cell migration which is consistent with our results. For example, invasion of reconstituted basement membranes in vitro by fibrosarcoma or osteosarcoma cells could be inhibited by anti-α6 antibody [28, 52]. It is interesting that the DU145 variants of α6 integrin studied here show only the α6a integrin subtype (data not shown), which has been shown to be associated with increased migration in comparison to α6β1 [53]. In human foreskin keratinocytes it has been suggested that α6β4 might restrict migration rather than promote it [49]. On the other hand, in an in vitro wound-healing explant model [54], migration of corneal epithelial cells was not inhibited by anti-β4 antibodies (only hemidesmosome formation was inhibited) but anti-α6 antibody was completely inhibitory for migration. Some studies suggest the opposite, α6β4 participating in migration [55].

Several factors may account for the apparent contradiction. For example, there may be a requirement for a threshold level of α6β4 to accomplish migration. The poor participation of α6β4 seen in DU-L cell migration might be a reflection of a small number of these receptors and could indicate that these cells require a critical amount of α6β4 receptors to accomplish migration rather than to adhere to laminin. Alternatively, the molecular features of α6β4 itself or its interaction with the cytoskeleton may be a factor. Others have reported splice variants of both α6 and β4 which also may be a factor. The interactions of these variant receptors with the cytoskeleton and its influence on cytoskeleton-dependent migration are currently unknown.

The fact that α6β1 is linked to the actin cytoskeleton makes it more likely to participate in migration than α6β4 which is linked to the intermediate filament network. The α6β4 and its associated structural proteins localize into stable anchoring structures known as hemidesmosomes. The loss of hemidesmosomes and the α6β4 integrin in prostate carcinomas has been observed by us previously [39]. The loss of the stable anchor could facilitate movement of the cell and according to our migration data, the persistence of the alternative receptor, α6β1, would provide a definite advantage in facilitating movement on a laminin substrate.

Our data suggest that α6 may have an important influence on the invasion of cells through the basement membranes and stromal tissues. We find that DU-H expressors show a considerable difference in their invasive ability of the SCID mouse diaphragm basement membrane and stroma in comparison to DU-L cells that show a low invasive ability. This is consistent with other studies done with osteosarcoma cells that showed a correlation of the in vitro invasion of reconstituted basement membranes with α6 expression [28]. In the same line of studies, mouse tail vein injections of melanoma cells have been inhibited in their metastatic potential with anti-α6 antibodies [26], or show a correlation between α6 expression and metastatic ability [56]. Our results add to these previous results that the expression of α6 integrins is correlated with invasion in vivo of basement membranes and tissue stroma.

The mechanism by which α6 facilitates invasion could be adhesion-related (as migration and contact with basement membranes), and/or signal transduction related, as an increase in other elements useful to traverse basement membranes. Some integrins have been shown to increase the signaling for protease production [57], but this has not been shown for the α6 integrins. Our data suggest that the migratory and adhesive abilities of the DU-H cells might explain in part their greater invasive ability in comparison to DU-L, but other mechanisms are likely to co-exist. It is interesting that the DU-L cells had a marked increase in their proliferation rate in vivo, which could be related to some regulatory signaling by the α6 integrins. This has been observed with other integrins. An inverse correlation between proliferation and integrin expression has been observed for α5β1 integrin where the low expressors showed a higher proliferation and tumorigenicity than the high expressors; transfection of α5 may result in decreased tumorigenicity [58, 59]. On the other hand the presence of certain integrins such as αvβ3 may show positive effects on cell proliferation [60]. In either case it underscores the participation of integrins in the proliferation process and our results suggest the participation of α6 in this process.

It is interesting that α6 integrin is increased chiefly at the sites of invasion. This suggests that expression of α6 integrins may provide an advantage mainly at the front of invasion where it might interact and be regulated by the newly available ECM. Diaphragm skeletal muscle is rich in laminin-related molecules which could facilitate migration of α6β1-containing cells. This would be relevant in prostatic carcinoma as prostate tissue is laminin rich. Laminin in the prostate gland is present surrounding smooth muscle cells, vascular structures and perineurial nerve sheaths which could provide laminin paths for the tumor cells. Indeed nerves have been shown to participate in the extracapsular dissemination of prostate carcinoma [61].

Our results indicating that α6 integrin expression correlates with prostate cell migration on laminin and invasion through stroma, together with previous histopathological studies that confirm the persistence of this integrin in prostate tumor progression [26, 39], suggest an important role of α6 integrins in this disease.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the technical assistance of Barb A. Carolus for the FACS sorting and Louis R. Breton and Virginia Clark for the sectioning and staining of the mouse tumor tissues.

References

- 1.Stetler-Stevenson WG, Aznavoorian S, Liotta LA. Tumor cell interactions with the extracellular matrix during invasion and metastasis. A Rev Cell Biol. 1993;9:541–573. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.09.110193.002545. [Review.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hynes RO. Integrins: versatility, modulation, and signaling in cell adhesion. Cell. 1992;69:11–25. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90115-s. [Review.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sonnenberg A. Integrins and their ligands. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1993;184:7–35. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-78253-4_2. [Review.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castronovo V. Laminin receptors and laminin-binding proteins during tumor invasion and metastasis. Invasion Metastasis. 1993;13:1–30. [Review.] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aumailley M, Timpl R, Sonnenberg A. Antibody to integrin alpha 6 subunit specifically inhibits cell-binding to laminin fragment 8. Exp Cell Res. 1990;188:55–60. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(90)90277-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee EC, Lotz MM, Steele G, Jr, Mercurio AM. The integrin alpha 6 beta 4 is a laminin receptor. J Cell Biol. 1992;117:671–678. doi: 10.1083/jcb.117.3.671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niessen CM, Hogervorst F, Jaspars LH, et al. The alpha 6 beta 4 integrin is a receptor for both laminin and kalinin. Exp Cell Res. 1994;211:360–367. doi: 10.1006/excr.1994.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooper HM, Tamura RN, Quaranta V. The major laminin receptor of mouse embryonic stem cells is a novel isoform of the alpha 6 beta 1 integrin. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:843–850. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.3.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mercurio AM, Shaw LM. Laminin binding proteins. Bioessays. 1991;13:469–473. doi: 10.1002/bies.950130907. [Review.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collo G, Starr L, Quaranta V. A new isoform of the laminin receptor integrin alpha 7 beta 1 is developmentally regulated in skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:19019–19024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takada Y, Murphy E, Pil P, Chen C, Ginsberg MH, Hemler ME. Molecular cloning and expression of the cDNA for alpha 3 subunit of human alpha 3 beta 1 (VLA-3), an integrin receptor for fibronectin, laminin, and collagen. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:257–266. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.1.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Languino LR, Gehlsen KR, Wayner E, Carter WG, Engvall E, Ruoslahti E. Endothelial cells use alpha 2 beta 1 integrin as a laminin receptor. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:2455–2462. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.5.2455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hogervorst F, Kuikman I, van Kessel AG, Sonnenberg A. Molecular cloning of the human alpha 6 integrin subunit. Alternative splicing of alpha 6 mRNA and chromosomal localization of the alpha 6 and beta 4 genes. Eur J Biochem. 1991;199:425–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb16140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tamura RN, Rozzo C, Starr L, et al. Epithelial integrin alpha 6 beta 4: complete primary structure of alpha 6 and variant forms of beta 4. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:1593–1604. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.4.1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tamura RN, Cooper HM, Collo G, Quaranta V. Cell type-specific integrin variants with alternative alpha chain cytoplasmic domains. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:10183–10187. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.22.10183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sonnenberg A, Linders CJ, Daams JH, Kennel SJ. The alpha 6 beta 1 (VLA-6) and alpha 6 beta 4 protein complexes: tissue distribution and biochemical properties. J Cell Sci. 1990;96:207–217. doi: 10.1242/jcs.96.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hogervorst F, Admiraal LG, Niessen C, et al. Biochemical characterization and tissue distribution of the A and B variants of the integrin alpha 6 subunit. J Cell Biol. 1993;121:179–191. doi: 10.1083/jcb.121.1.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Terpe HJ, Stark H, Ruiz P, Imhof BA. Alpha-6 integrin distribution in human embryonic and adult tissues. Histochemistry. 1994;101:41–49. doi: 10.1007/BF00315830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones JC, Kurpakus MA, Cooper HM, Quaranta V. A function for the integrin alpha 6 beta 4 in the hemidesmosome. Cell Regulation. 1991;2:427–438. doi: 10.1091/mbc.2.6.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sonnenberg A, Calafat J, Janssen H, et al. Integrin alpha 6/beta 4 complex is located in hemidesmosomes, suggesting a major role in epidermal cell-basement membrane adhesion. J Cell Biol. 1991;113:907–917. doi: 10.1083/jcb.113.4.907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stepp MA, Spurr-Michaud S, Tisdale A, Elwell J, Gipson IK. Alpha 6 beta 4 integrin heterodimer is a component of hemidesmosomes. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:8970–8974. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.22.8970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gomez M, Navarro P, Quintanilla M, Cano A. Expression of alpha 6 beta 4 integrin increases during malignant conversion of mouse epidermal keratinocytes: association of beta 4 subunit to the cytokeratin fraction. Exp Cell Res. 1992;201:250–261. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(92)90272-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dedhar S. Integrins and tumor invasion. Bioessays. 1990;12:583–590. doi: 10.1002/bies.950121205. [Review.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Albelda SM. Role of integrins and other cell adhesion molecules in tumor progression and metastasis. Lab Invest. 1993;68:4–17. [Review.] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Juliano RL, Varner JA. Adhesion molecules in cancer: the role of integrins. Curr Opinion Cell Biol. 1993;5:812–818. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(93)90030-t. [Review.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruiz P, Dunon D, Sonnenberg A, Imhof BA. Suppression of mouse melanoma metastasis by ea-1, a monoclonal-antibody specific for alpha(6)-integrins. Cell Adhes Commun. 1993;1:67–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin CS, Zhang K, Kramer R. Alpha 6 integrin is up-regulated in step increments accompanying neoplastic transformation and tumorigenic conversion of human fibroblasts. Cancer Res. 1993;53:2950–2953. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dedhar S, Saulnier R. Alterations in integrin receptor expression on chemically transformed human cells: specific enhancement of laminin and collagen receptor complexes. J Cell Biol. 1990;110:481–489. doi: 10.1083/jcb.110.2.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gould VE, Koukoulis GK, Virtanen I. Extracellular matrix proteins and their receptors in the normal, hyperplastic and neoplastic breast. Cell Differ Develop. 1990;32:409–416. doi: 10.1016/0922-3371(90)90057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.D'Ardenne AJ, Richman PI, Horton MA, Mcaulay AE, Jordan S. Co-ordinate expression of the alpha-6 integrin laminin receptor sub-unit and laminin in breast cancer. J Pathol. 1991;165:213–220. doi: 10.1002/path.1711650304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Natali PG, Nicotra MR, Botti C, Mottolese M, Bigotti A, Segatto O. Changes in expression of alpha 6/beta 4 integrin heterodimer in primary and metastatic breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 1992;66:318–322. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1992.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Korhonen M, Laitinen L, Ylanne J, et al. Integrin distributions in renal cell carcinomas of various grades of malignancy. Am J Pathol. 1992;141:1161–1171. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Friedrichs K, Ruiz P, Folker F, Gille I, Terpe HJ, Imhof BA. High expression level of alpha 6 integrin in human breast carcinoma is correlated with reduced survival. Cancer Res. 1995;55:901–906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weinel RJ, Rosendahl A, Neumann K, et al. Expression and function of VLA-alpha 2, -alpha 3, -alpha 5 and -alpha 6-integrin receptors in pancreatic carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 1992;52:827–833. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910520526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosendahl A, Neumann K, Chaloupka B, Rothmund M, Weinel RJ. Expression and distribution of VLA receptors in the pancreas: an immunohistochemical study. Pancreas. 1993;8:711–718. doi: 10.1097/00006676-199311000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Waes C, Carey TE. Overexpression of the A9 antigen/alpha 6 beta 4 integrin in head and neck cancer. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1992;25:1117–1139. [Review.] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Timmer A, Oosterhuis JW, Schraffordt Koops H, Sleijfer DT, Szabo BG, Timens W. The tumor microenvironment: possible role of integrins and the extracellular matrix in tumor biological behavior of intratubular germ cell neoplasia and testicular seminomas. Am J Pathol. 1994;144:1035–1044. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mortarini R, Anichini A, Parmiani G. Heterogeneity for integrin expression and cytokine-mediated VLA modulation can influence the adhesion of human melanoma cells to extracellular matrix proteins. Int J Cancer. 1991;47:551–559. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910470413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Knox JD, Cress AE, Clark V, et al. Differential expression of extracellular matrix molecules and the alpha 6 integrins in the normal and neoplastic prostate. Am J Pathol. 1994;145:167–174. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bonkhoff H, Stein U, Remberger K. Differential expression of alpha 6 and alpha 2 very late antigen integrins in the normal, hyperplastic, and neoplastic prostate: simultaneous demonstration of cell surface receptors and their extracellular ligands. Human Pathol. 1993;24:243–248. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(93)90033-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mickey DD, Stone KR, Wunderli H, Mickey GH, Paulson DF. Characterization of a human prostate adenocarcinoma cell line (DU145) as a monolayer culture and as a solid tumor in athymic mice. In: Murphy GP, editor. Models for Prostate Cancer. New York: Alan R. Liss; 1980. pp. 67–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Patillo RA, Reickert A, Hussa R, Bernstein R, Delfs E. The JAR cell line. In Vitro. 1971;6:398–399. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Isberg RR, Leong JM. Multiple beta 1 chain integrins are receptors for invasin, a protein that promotes bacterial penetration into mammalian cells. Cell. 1990;60:861–871. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90099-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Einheber S, Milner TA, Giancotti F, Salzer JL. Axonal regulation of Schwann cell integrin expression suggests a role for alpha 6 beta 4 in myelination. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:1223–1236. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.5.1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Witkowski CM, Rabinovitz I, Nagle RB, Affinito KS, Cress AE. Characterization of integrin subunits, cellular adhesion and tumorgenicity of four human prostate cell lines. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1993;119:637–644. doi: 10.1007/BF01215981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Waleh NS, Gallo J, Grant TD, Murphy BJ, Kramer RH, Sutherland RM. Selective down-regulation of integrin receptors in spheroids of squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 54:838–843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bednarczyk JL, Szabo MC, McIntyre BW. Post-translational processing of the leukocyte integrin alpha 4 beta 1. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:25274–25281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lotz MM, Korzelius CA, Mercurio AM. Human colon carcinoma cells use multiple receptors to adhere to laminin: involvement of alpha 6 beta 4 and alpha 2 beta 1 integrins. Cell Regul. 1990;1:249–257. doi: 10.1091/mbc.1.3.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carter WG, Kaur P, Gil SG, Gahr PJ, Wayner EA. Distinct functions for integrins alpha 3 beta 1 in focal adhesions and alpha 6 beta 4/bullous pemphigoid antigen in a new stable anchoring contact (SAC) of keratinocytes: relation to hemidesmosomes. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:3141–3154. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.6.3141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hall DE, Reichardt LF, Crowley E, et al. The alpha 1/beta 1 and alpha 6/beta 1 integrin heterodimers mediate cell attachment to distinct sites on laminin. J Cell Biol. 1990;110:2175–2184. doi: 10.1083/jcb.110.6.2175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.LaFlamme SE, Thomas LA, Yamada SS, Yamada KM. Single subunit chimeric integrins as mimics and inhibitors of endogenous integrin functions in receptor localization, cell spreading and migration, and matrix assembly. J Cell Biol. 1994;126:1287–1298. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.5.1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ramos DM, Cheng YF, Kramer RH. Role of laminin-binding integrin in the invasion of basement membrane matrices by fibrosarcoma cells. Invasion Metastasis. 1991;11:125–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shaw LM, Mercurio AM. Regulation of cellular interactions with laminin by integrin cytoplasmic domains: the A and B structural variants of the alpha 6 beta 1 integrin differentially modulate the adhesive strength, morphology, and migration of macrophages. Molec Biol Cell. 1994;5:679–690. doi: 10.1091/mbc.5.6.679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kurpakus MA, Quaranta V, Jones JC. Surface relocation of alpha 6 beta 4 integrins and assembly of hemidesmosomes in an in vitro model of wound healing. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:1737–1750. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.6.1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dedhar S, Saulnier R, Nagle R, Overall CM. Specific alterations in the expression of alpha 3 beta 1 and alpha 6 beta 4 integrins in highly invasive and metastatic variants of human prostate carcinoma cells selected by in vitro invasion through reconstituted basement membrane. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1993;11:391–400. doi: 10.1007/BF00132982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Danen EH, van Muijen GN, van de Wiel-van Kemenade E, Jansen KF, Ruiter DJ, Figdor CG. Regulation of integrin-mediated adhesion to laminin and collagen in human melanocytes and in non-metastatic and highly metastatic human melanoma cells. Int J Cancer. 1993;54:315–321. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910540225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sastry SK, Horwitz AF. Integrin cytoplasmic domains: mediators of cytoskeletal linkages and extra- and intracellular initiated transmembrane signaling. Curt Opin Cell Biol. 1993;5:819–831. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(93)90031-k. [Review.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schreiner C, Fisher M, Hussein S, Juliano RL. Increased tumorigenicity of fibronectin receptor deficient Chinese hamster ovary cell variants. Cancer Res. 1991;51:1738–1740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Giancotti FG, Ruoslathi E. Fibronectin receptors suppress the transformed phenotype of Chinese hamster ovary cells. Cell. 1990;60:849–859. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90098-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Felding-Habermann B, Mueller BM, Romerdahl CA, Cheresh DA. Involvement of integrin alpha v gene expression in human melanoma tumorigenicity. J. Clin Invest. 1992;89:2018–2022. doi: 10.1172/JCI115811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Villers A, McNeal JE, Redwine EA, Freiha FS, Stamey TA. The role of perineurial space invasion in the local spread of prostate carcinoma. J Urol. 1989;142:763–768. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)38881-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]