Abstract

Being discriminated against is an unpleasant and stressful experience, and its connection to reduced psychological well-being is well-documented. The present study hypothesized that a sense of control would serve as both mediator and moderator in the dynamics of perceived discrimination and psychological well-being. In addition, variations by age, gender, and race in the effects of perceived discrimination were explored. Data from the Midlife Development in the United States (MIDUS) survey (N = 1,554; age range = 45 to 74) provided supportive evidence for the hypotheses. The relationships between perceived discrimination and positive and negative affect were reduced when sense of control was controlled, demonstrating the role of sense of control as a mediator. The moderating role of sense of control was also supported, but only in the analysis for negative affect: the combination of a discriminatory experience and low sense of control markedly increased negative affect. In addition, age and gender variations were observed: the negative impact of perceived discrimination on psychological well-being was more pronounced among younger adults and females compared to their counterparts. The findings elucidated the mechanisms by which perceived discrimination manifested its psychological outcomes, and suggest ways to reduce adverse consequences associated with discriminatory experiences.

Recent studies have repeatedly demonstrated that the experience of being treated unfairly or discriminated against is associated with reduced mental health (e.g., Barnes, Mendes de Leon, Wilson, Bienias, Bennett, & Evans, 2004; Kessler, Mickelson, & Williams, 1999; Noh, Beiser, Kaspar, Hou, & Rummens, 1999; Williams, Yu, Jackson, & Anderson, 1997). Discrimination may result from a variety of factors including age, gender, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, physical appearance, and social class (Carr & Friedman, 2005; Williams et al., 1997). Whatever the source, perceived discrimination is known to contribute to the higher rates of psychological distress found among socially disadvantaged populations (Kessler et al., 1999; Thoits, 1983). Based on a large-scale national survey from the Midlife Development in the United States (MIDUS) study, Kessler and colleagues (1999) found that a surprisingly high proportion of the U.S. population (61%) reports experiences of discrimination in their daily life. Despite such evidence, there remains a paucity of research addressing perceived discrimination as a life stress and examining the intervening factors for this stressor (Dion, 2002; Kessler et al., 1999; Thoits, 1983). The pervasiveness of discriminatory experience and its adverse psychological consequences call attention to further research on the issue of discrimination.

The present study explored the dynamics of perceived discrimination and psychological well-being, with a focus on sense of control. Sense of control refers to the extent to which individuals perceive that they have personal power and control over their life and environment (e.g., Lachman & Weaver, 1998; Pearlin & Schooler, 1978; Zarit, Pearlin, & Schaie, 2003). An impressive body of literature demonstrates the significant benefits of feelings of control, and there is now a consensus that sense of control facilitates positive adaptation under stressful life conditions and promotes physical and emotional well-being (Jang, Graves, Haley, Small, & Mortimer, 2003; Johnson & Kreuger, 2005; Lachman & Weaver, 1998; Roberts, Dunkle, & Haug, 1994; Zarit et al., 2003).

Although sense of control is typically treated as a personal disposition or attribute, social and interpersonal factors should not be ignored (Krause, 1997; Schieman, 2003). Because humans are social beings and do not live in a vacuum, all individuals are constantly involved in interactions with others in everyday life. Such social interactions and interpersonal relationships, if positive, may bolster self-worth and feelings of control (Krause, 1977; Shorey, Cowan, & Sullivan, 2002; Verkuyten, 1998). In contrast, perceptions of disrespect and discrimination may erode personal control (Moradi & Hasan, 2004; Ruggiero & Taylor, 1997). The interplay among perceived discrimination, sense of control, and psychological well-being carries important social implications; however, few researchers have considered their dynamics.

Mediating Effects

Several potential pathways exist between perceived discrimination and psychological well-being. Perceived discrimination, for example, may not only have direct effects on psychological well-being, but also have indirect effects through a lowering of feelings of control. In other words, sense of control may serve as an internal mechanism by which the experience of discrimination manifests its psychological consequences. Salient to the present investigation is empirical evidence for the mediating role of sense of control among racial/ethnic minorities. Although based on small and non-representative samples of racial/ethnic minorities, several studies have found that feelings of control served as an intervening step between discriminative stressors and psychological outcomes (e.g., Branscombe & Ellemers, 1998; Moradi & Hasan, 2004; Ruggiero & Taylor, 1997). Given the high incidence of discriminatory experience in overall populations (e.g., Kessler et al., 1999), the mediating role of sense of control needs to be further explored with national data encompassing diverse populations.

Moderating Effects

Another important area of investigation is a possible interaction between perceived discrimination and sense of control. It is expected that the negative impacts of perceived discrimination on psychological well-being would be modified (e.g., attenuated or intensified) by the level of sense of control. A high level of sense of control may buffer the negative consequences of discrimination; whereas the combination of a discriminatory experience and low sense of control may markedly reduce one’s status of well-being (Cassidy, O’Connor, Howe, & Warden, 2004).

Additionally, potential modifications by age, gender, and race need to be considered since they may alter the relationships between perceived discrimination and psychological well-being. Previous studies report age variations, showing that the adverse mental health consequences of discrimination were lower among older adults compared to younger ones (Kessler et al., 1999). The response to and consequences of discriminatory social interactions may reflect individual differences in vulnerability or perceptual tolerance with the experiences (Barnes et al., 2004). The basic demographic characteristics, age, gender, and race, may not only be major sources of discrimination (e.g., ageism, sexism, and racism) but also determine the magnitude of psychological influence by the discriminatory experiences.

Taking the existing research into account, the present study explored the dynamics of perceived discrimination, sense of control, and psychological well-being, focusing on the mediating and moderating roles of sense of control. Additionally, modifications by age, gender, and race in the linkages between perceived discrimination and psychological well-being were assessed.

METHODS

Sample

The data were from the Midlife Development in the United States (MIDUS) survey conducted by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Network on Successful Midlife Development in 1995 and early 1996. A national probability sampling with random digit dialing procedures was used to recruit English-speaking and non-institutionalized adults aged 25 to 74 across 48 states. The survey was conducted with two methods: telephone survey (70% response rate) and self-administered mail survey (87%). The total number of individuals who returned the mail survey questionnaire was 3,032. More detailed information on the MIDUS project can be found elsewhere (e.g., Kessler et al., 1999; Lachman & Weaver, 1998). Given the specific interest in middle-aged and older adults, the present analysis is based on subjects aged 45 to 74 (N = 1,651). Among them, those who had more than 10% missing information in the study variables (N = 97) were excluded, leaving 1,554 subjects for analysis.

Measures

Perceived Discrimination

A 9-item instrument (Williams et al., 1997) assessed the frequency of maltreatment or disrespects by others in daily life. It is notable that the scale is not designed to measure specific types of discrimination (e.g., ageism, sexism, racism). Instead the instrument included statements such as “You are treated with less courtesy than other people,” “You are treated with less respect than other people,” and “People act as if they think you are dishonest.” Participants were asked to indicate their response with a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (often). Total scores were computed, with higher scores indicating more frequent experiences of discrimination. Internal consistency of the scale was high in the present sample (α = 0.93).

Sense of Control

Based on Lachman and Weaver’s (1998) expansion of Pearlin and Schooler’s (1978) original measure of sense of mastery, twelve questions were asked. The scale included four positively worded items (e.g., “I can do just about anything I really set my mind to do,” and “What happens to me in the future mostly depends on me.”) and eight negatively worded items (e.g., “I often feel helpless in dealing with problems of life,” and “Sometimes I feel I am being pushed around in my life.”). Participants were asked to indicate how they agreed with each statement using a 7-point scale. Negatively worded items were reverse-coded and all responses were summed for total scores. Total scores range from 7 to 84 with higher scores indicating greater levels of sense of control. The utility and psychometric properties of the instrument have been validated in several studies (e.g., Lachman & Weaver, 1998; Prenda & Lachman, 2001). In the present sample, a satisfactory internal consistency was found (α = 0.85).

Psychological Well-being

Based on the Bradburn’s (1969) two-factor model, positive and negative affects were adopted as indices of psychological well-being. Six items for each affect scale were selected from a variety of well-validated scales, including the Affect Balance Scale (Bradburn, 1969), the University of Michigan’s Composite International Diagnostic Interview (Kessler, Andrews, Moroczek, Ustun, & Wittchen, 1998), and the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (Radloff, 1977). For positive affect, participants were asked to report how often they had felt cheerful, in good spirits, extremely happy, calm and peaceful, satisfied, and full of life during the past 30 days. The items for negative affect assessed the frequency of feeling sad, nervous, restless, hopeless, everything was an effort, and worthless during the past 30 days. Responses were coded as 1 (none of the time) to 5 (all the time). Higher scores in each domain indicate greater levels of positive affect and negative affect, respectively. Internal consistency of the scale was high in the present sample (α = 0.91 for positive affect; α = 0.87 for negative affect).

Other variables included age (in years), gender (1 = male, 2 = female), and race1 (1 = White, 2 = non-White).

RESULTS

Descriptive Information and Bivariate Correlations among Study Variables

The average age of the sample was 56.8 (SD = 8.30) with a range from 45 to 74. The sample had a relatively equal gender distribution (52% female), and a majority were White (91%). Scores for perceived discrimination and sense of control averaged 12.4 (SD = 4.59) and 65.2 (SD = 13.1), respectively. The means for positive affect and negative affect were 20.5 (SD = 4.38) and 9.01 (SD = 3.61). In a supplementary analysis, age (11.2%), gender (12.4%), and race (9.5%) were most frequently endorsed as a major reason for discrimination.

At the bivariate level, those who were younger or minorities were more likely to report perceived discrimination. A greater sense of control was associated with being younger, male, and reporting less discrimination. Higher levels of positive affect and lower levels of negative affect were commonly observed among those who were younger, male, lower on perceived discrimination, and with a greater sense of control. All correlation coefficients were below .50 except for the correlation between positive and negative affect (r = −.62, p < .001). However, collinearity was not an issue since these two variables were treated as separate outcomes in regression analyses. Descriptive information of and correlations among study variables are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Information and Bivariate Correlations

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | M/SD (%) | Range | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | .01 | −.04 | −.12*** | −.07*** | .12*** | −.08*** | 56.87 / 8.30 | 45–75 | ||

| 2. Gender (female) | .00 | .01 .36*** |

−.13*** | −.08** | .14*** | (51.8) | ||||

| 3. Race (non-White) | −.04 | .01 | .02 | (8.8) | ||||||

| 4. Perceived discrimination | −.15*** | −.13*** | .22*** | 12.4 / 4.59 | 9–36 | .93 | ||||

| 5. Sense of control | .44*** | −.49*** | 65.2/13.1 | 12–84 | .85 | |||||

| 6. Positive affect | −.62*** | 20.5 / 4.38 | 6–30 | .91 | ||||||

| 7. Negative affect | 9.01/3.61 | 6–30 | .87 |

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Multivariate Test for a Mediating Effect

Prior to testing the regression models, a preliminary assessment was conducted. Even though the literature suggests that sense of control and psychological well-being represent distinctive, albeit interrelated constructs (e.g., Bienenfeld, Koenig, Larson, & Sherrill, 1997), we examined collinearity. The variance inflation factors (VIF) used for this assessment did not detect the presence of collinearity between sense of control and the measures of psychological well-being. The computed values of VIF ranged from 1.01 to 1.18; these values are far less than 4, the standard indicator of multicollinearity.

Using Baron and Kenny’s (1986) criteria for mediation, the mediating model of sense of control was tested. The criteria included whether

there was a significant association between the independent (perceived discrimination) and dependent (positive affect or negative affect) variables,

there was a significant association between independent (perceived discrimination) and presumed mediator (sense of control) variables,

there was a significant association between presumed mediator (sense of control) and dependent (positive affect or negative affect) variables, and

after controlling the mediator (sense of control), the previously significant relationship between independent (perceived discrimination) and dependent (positive affect or negative affect) variables decreased or became non-significant.

For the two outcome measures, separate models were estimated. All analyses were conducted with a control for the effects of age, gender, and race.

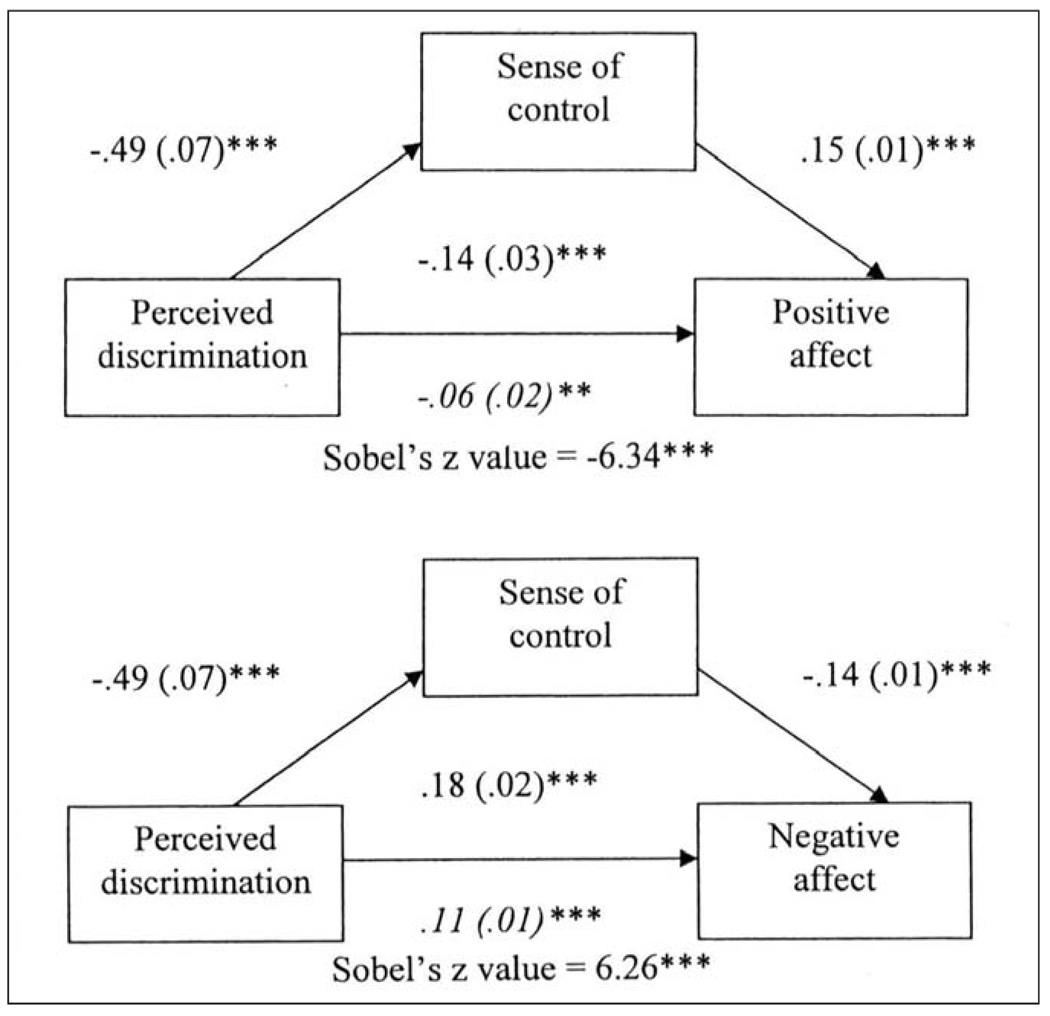

A series of regression analyses were conducted, and the results are summarized in Figure 1 (regression tables are not shown). The regression coefficients of the three paths among the independent variable (perceived discrimination), presumed mediator (sense of control), and dependent variable (positive affect or negative affect) were all significant. When sense of control was controlled, there was a reduction in the regression coefficients of perceived discrimination on both positive and negative affect, satisfying the Baron and Kenny’s criteria.

Figure 1.

Mediating effects of sense of control in the relationship between perceived discrimination and psychological well-being.

Note: Numbers indicate unstandardized regression coefficients and standard errors in parentheses. The values italicized represent the indirect effect of perceived discrimination on positive and negative affect after controlling for the effects of sense of control. All analyses were conducted with a control for age, gender, and race.

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

As a way to quantify the degree of reduction in regression coefficients, each mediation model was assessed with the Sobel test, a statistical method for determining the influence of a mediator on an outcome variable (MacKinnon & Dwyer, 1993). The degree of reduction in regression coefficients was found to be statistically significant for positive affect (z = −6.34, p < .001) and for negative affect (z = 6.26, p < .001.)

Multivariate Test for a Moderating Effect

For the research question concerning with the moderating effects, hierarchical regression analyses were conducted, assessing both direct and interactive roles of the predictive variables. Table 2 summarizes the regression models. These models were estimated with the predictors entered in the following order:

age, gender, and race,

perceived discrimination, and

sense of control.

Table 2.

Regression Models of Positive Affect and Negative Affect

| Positive affect | Negative affect | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step | Predictor | β | t | ΔR2 | β | t | ΔR2 |

| 1 | Age | .13 | 4.97*** | .02*** | −.08 | −3.37*** | .03** |

| Gender | −.08 | −2.95** | .14 | 5.35*** | * | ||

| Race | .02 | .90 | .02 | .75 | |||

| 2 | Perceived discrimination | −.14 | −5.23** | .02*** | .23 | 8.42*** | |

| 3 | Sense of control | .43 | −18.5*** | .18*** | −.46 | −20.6*** | .04** |

| 4 | Discrimination × Age | .03 | 1.42 | .00 | −.05 | −2.29* | * |

| Discrimination × Gender | −.07 | −.89 | .27 | 3.69*** | .21** | ||

| Discrimination × Race | −.11 | −1.33 | −.03 | −.37 | * | ||

| Discrimination × Control | .00 | .02 | −.11 | −4.57*** | .02** | ||

| Overall R2 | .22*** | .30*** | * | ||||

| F | 47.2 | 70.8 | |||||

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

βs represent standard regression coefficients in each step after controlling for the previous blocks.

In addition to the direct effect model, interactions of perceived discrimination with age, gender, race, and sense of control were tested as a final step. The analyses were designed to assess whether the impact of perceived discrimination on psychological well-being is altered by age, gender, race, and the level of sense of control. In computing interaction terms, centered scores were used to avoid multicollinearity between direct effects and interaction terms (Aiken & West, 1991).

In the direct effect models of both positive and negative affect, age, gender, perceived discrimination, and sense of control were identified as common significant predictors. Greater levels of psychological well-being, as indicated by a higher positive affect or a lower negative affect, were observed among those who were older, male, with less perceived discrimination, and higher sense of control. The amount of variance explained by the direct effect model was 22% for positive affect (F = 84.2, p < .001) and 28% for negative affect (F = 114.1, p < .001). The entry of interaction terms did not improve the model of positive affect, but it contributed significantly to the model of negative affect, accounting for an additional 2% of explained variance (F = 2.2, p < .001). Among the four interaction terms entered, three terms (Discrimination × Age, Discrimination × Gender, and Discrimination × Control) reached statistical significance.

In order to better understand the moderating relationships, the total sample was stratified into two groups based on each of the three moderating factors, and the correlations between perceived discrimination and negative affect in the subgroups were compared using Fisher’s r-to-z transformation, a statistical method to determine the difference between independent correlation coefficients (Steiger, 1980). Table 3 demonstrates comparative analyses with subgroups. With respect to age, the total sample was stratified based on median age: the two groups consisted of those who were middle-aged (age range = 45 to 54; N = 749) and those who were older (age range = 55 to 74; N = 775) with a comparable number of subjects in each group. The correlation between perceived discrimination and negative affect was stronger in the middle-aged group compared with the older adult group, and the difference in coefficients was statistically significant (t = 3.86, p < .01). With respect to the gender factor, females (N = 785) presented a stronger association between perceived discrimination and negative affect than males (N = 739), and the difference was statistically significant (t = 4.48, p < .001). When the sample was divided into low and high groups based on median score for sense of control (67), the correlation coefficient between perceived discrimination and negative affect was stronger in the low control group (N = 704) than that in the high control group (N = 778). The difference between coefficients in the low and high control groups was shown to be statistically significant (t = 3.17, p < .01).

Table 3.

Correlation Coefficients between Perceived Discrimination and Negative Affect in Subgroups by Moderating Factors

| Grouping by a moderating factor | Correlation coefficient between perceived discrimination and negative affect (r) |

t |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| Middle age (N = 749) | .29*** | 3.86*** |

| Old age (N = 775) | .10** | |

| Gender | ||

| Male (N = 739) | .09*** | 4.48*** |

| Female (N = 785) | .31*** | |

| Sense of control | ||

| Low control group (N = 704) | .25*** | 3.17*** |

| High control group (N = 778) | .09* | |

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

DISCUSSION

The present study focused on perceived discrimination, a stressful experience that is not uncommon yet is relatively understudied (e.g., Dion, 2002; Kessler et al., 1999; Thoits, 1983). The primary goal of the analyses was to explore internal mechanisms underlying in the relationships between the experiences of discrimination and psychological well-being, focusing on the mediating and moderating roles of sense of control. The results, obtained from a series of multivariate analyses with 1,554 individuals from the Midlife Development in the United States (MIDUS) survey, provided support for the hypothesized models.

The main focus of the present study was to better understand the intervening and interactive roles of the predictors. In the initial direct effect model, age, gender, perceived discrimination, and sense of control were identified as significant determinants of psychological well-being, indicated by both positive and negative affect. The findings are consistent with previous literature showing a positive connection of psychological well-being with advanced age, male gender, lack of discriminatory experience, and feelings of control (e.g., Kessler et al., 1999; Lachman & Weaver, 1998; Mroczek & Kolarz, 1998).

The mediation analyses provided support for the idea that the adverse effect of perceived discrimination on psychological well-being is not only direct but also indirect through a lowering of the sense of control for both positive and negative affect. These results build on the past research that has suggested the salience of a mediation of sense of control with relatively small samples of racial/ethnic minorities (e.g., Branscombe & Ellemers, 1998; Moradi & Hasan, 2004; Ruggiero & Taylor, 1997). The mediation model, supported by the present analysis, elucidates internal mechanisms by which psychological well-being of the population can be protected in the face of discriminatory experiences.

Another notable finding of the present study was the interactive role of perceived discrimination and sense of control in predicting negative affect. The negative impact of discrimination on psychological well-being was shown to be pronounced among those with a lower sense of control; whereas those with a higher sense of control were less affected by the discriminatory experiences. The findings suggest that sense of control protects individuals from the adversities of discrimination and enable them to remain resilient. The moderating or buffering effects of sense of control help identify individuals who are particularly vulnerable to psychological distress when faced with discriminatory experiences.

The significant interaction of perceived discrimination with age and gender illustrates age and gender variations in responding to the experiences of discrimination. Results suggested that the impacts of perceived discrimination on negative affect were particularly greater for younger individuals and females. The reduced impact of discriminatory experiences among older adults may reflect an accommodation akin to desensitization to noxious stimuli. Years of exposure to discrimination may have led to the development of effective coping strategies, or perhaps to stress resilience. Also, there may be cohort differences in the perceptions of and reactions to discrimination. Unlike younger cohorts who have been exposed to social unacceptability of discrimination, the older subjects in this study were raised during the periods where discrimination was often an unavoidable fact of life regardless of race and gender (Barnes et al., 2004). It is also possible that older individuals may be more likely to use strategies of psychological denial or avoidance when they were encountered discriminatory experiences. Indeed, there has been some discussion in the literature that denial of discriminatory experiences may have beneficial outcomes (e.g., Ruggiero & Taylor, 1997). The observed gender difference in response to discriminatory experience is not surprising because women are generally known to be more sensitive to interpersonal conflicts than men (e.g., Kendler, Thornton, & Prescott, 2001).

Some limitations to the present study should be noted. Since the present study was based on a cross-sectional design, caution must be exercised in drawing causal inferences from the data. Inferential statistics would benefit from an assessment of dynamic changes over time with longitudinal study designs. Also, given the disproportionate size of non-Whites in the sample, potential racial variation is in need of further assessment. The approach to minority classification used in the MIDUS survey was also a source of concern, since the single identifier employed a mix of racial and ethnic categories. For the present analyses, we recoded responses into dichotomous categories of “White” and “non-White.” It is quite possible that some unknown proportion of those in the “White” category were actually individuals with Hispanic origins. The potential inclusion of both non-Hispanic Whites and Hispanics in the White category, as well as the mix of various minority groups in the non-White category may explain why race as a variable did not contribute significantly in the present analyses.

Despite the aforementioned limitations, the present study expands our knowledge base and provides important implications for research and practice. The MIDUS data provided a unique opportunity to explore an important social issue of discrimination and its consequences at a national level. Our study confirmed previous findings that experiences of discrimination are not uncommon and are associated with lower levels of psychological well-being. More importantly, the analyses also identified pathways by which discrimination may affect psychological well-being. From a practical perspective, the mediating and moderating effect model suggests that the personal feelings of control should be targeted for intervention and counseling programs. Bolstering personal control may be a useful intervention for preventing and alleviating negative psychological consequences related to discrimination. Interventions should help individuals perceive themselves as positive and worthy members of a group and society and develop positive self-identity. For example, it is known that establishment of positive group identity helps individuals cope with stigma or prejudice against certain groups (e.g., Branscombe & Ellemers, 1998; Noh et al., 1999.) While our findings suggest an avenue for interventions at an individual level, it should not be ignored that the elimination of potential sources of problems represents the most effective way of dealing with the issue. Thus, elimination of discrimination should be a target of social policies and programs. Our study calls attention to the heightened need for advocacy and education in order to help ensure that all members of our society are more aware of and respectful of diversity, and to help ensure the creation of social environments that do not trigger perceptions of discrimination.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the anonymous reviewers for their comments on an earlier version of this article.

Footnotes

The project was supported by the MIDUS Pilot Research Grant Program (PO1 AG020166—Integrative Pathways to Health and Illness.

The original MIDUS data included 2,241 Whites, 122 Black and/or African American, 15 Native American or aleutian Islander, 25 Asian or Pacific Islander, 67 other, and 19 multicultural. Due to a relatively small size of the minority groups, it was necessary to create a dichotomized variable.

REFERENCES

- Aiken L, West S. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes L, Mendes de Leon C, Wilson R, Bienials J, Bennett D, Evans D. Racial differences in perceived discrimination in a community population of older Blacks and Whites. Journal of Aging and Health. 2004;16:315–337. doi: 10.1177/0898264304264202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron R, Kenny D. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienenfeld D, Koenig H, Larson D, Sherrill K. Psychological predictors of mental health in a population of elderly women: Test of an explanatory model. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 1997;5:43–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradburn N. The structure of psychological well-being. Chicago, IL: Aldine; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Branscombe N, Ellemers N. Coping with group-based discrimination: Individualistic versus group-based strategies. In: Swim JK, Stangor C, editors. Prejudice: The target’s perspective. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1998. pp. 243–265. [Google Scholar]

- Carr D, Friedman M. Is obesity stigmatizing? Body weight, perceived discrimination, and psychological well-being in the United States. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2005;46:244–259. doi: 10.1177/002214650504600303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy C, O’Connor R, Howe C, Warden D. Perceived discrimination and psychological distress: The role of personal and ethnic self-esteem. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2004;51:329–339. [Google Scholar]

- Dion K. The social psychology of perceived prejudice and discrimination. Canadian Psychology. 2002;43:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Frazier P, Tix A, Barron K. Testing moderator and mediator effects in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2004;51:115–134. [Google Scholar]

- Jang Y, Graves AB, Haley WE, Small BJ, Mortimer JA. Determinants of a sense of mastery in African American and White older adults. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2003;53B:S221–S224. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.4.s221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson W, Krueger R. Higher perceived life control decreased genetic variance in physical health: Evidence from a national twin study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;88:165–173. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler K, Thornton L, Prescott C. Gender differences in the rates of exposure to stressful life events and sensitivity to their depressogenic effects. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:587–593. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.4.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R, Andrews A, Moroczek D, Ustun B, Wittchen H. The World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview Short-Form (CIDI-SF) International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 1998;7:171–185. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R, Mickelson K, Williams D. The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1999;40:208–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Social support and feelings of personal control in later life. In: Pierce GR, Lakey B, Sarason IG, Sarason BR, editors. Sourcebook of social support and personality. New York: Plenum Press; 1997. pp. 335–355. [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME, Weaver S. The sense of control as a moderator of social class differences in health and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:763–773. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.3.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon D, Dwyer JH. Estimating mediated effects in prevention studies. Evaluation Review. 1993;17:144–158. [Google Scholar]

- Moradi B, Hasan N. Arab American persons’ reported experiences of discrimination and mental health: The mediating role of personal control. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2004;51:418–428. [Google Scholar]

- Mroczek D, Kolarz C. The effect of age on positive and negative affect: A developmental perspective on happiness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75:1333–1349. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.5.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noh S, Beiser M, Kaspar V, Hou F, Rummens J. Perceived racial discrimination, depression, and coping: A study of Southeast Asian refugees in Canada. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1999;40:193–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin L, Schooler C. The structure of coping. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1978;19:2–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prenda K, Lachman M. Planning for the future: A life management strategy for increasing control and life satisfaction in adulthood. Psychology and Aging. 2001;16:206–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BL, Dunkle R, Haug M. Physical, psychological, and social resources as moderators of the relationship of stress to mental health of the very old. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 1994;49:S35–S43. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.1.s35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggiero K, Taylor D. Why minority group members perceive or do not perceive the discrimination that confronts them: The role of self-esteem and perceived control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;72:373–389. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.72.2.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schieman S. Perceived, generalized, and learned aspects of personal control. In: Zarit SH, Pearlin LI, Schaie KW, editors. Personal control in social and life course contexts. New York: Springer; 2003. pp. 71–82. [Google Scholar]

- Shorey H, Cowan G, Sullivan M. Predicting perceptions of discrimination among Hispanics and Anglos. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2002;24:3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Steiger J. Tests for comparing elements of a correlation matrix. Psychological Bulletin. 1980;87:245–251. [Google Scholar]

- Thoits P. Dimensions of life events that influence psychological distress: An evaluation and synthesis of literature. In: Kaplan HB, editor. Psychosocial research: Trends in theory and research. New York: Academic Press; 1983. pp. 33–103. [Google Scholar]

- Verkuyten M. Perceived discrimination and self-esteem among ethnic minority adolescents. Journal of Social Psychology. 1998;138:479–493. doi: 10.1080/00224549809600402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D, Yu Y, Jackson J, Anderson N. Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology. 1997;2:335–351. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarit S, Pearlin L, Schaie W. Personal control in social and life course contexts. New York: Springer; 2003. [Google Scholar]