Abstract

Reactive oxygen species play a major role in neurodegeneration. Increasing concentrations of peroxide induce neural cell death through activation of pro-apoptotic pathways. We now report that hydrogen peroxide generated sn-2 oxidized phosphatidylcholine (OxPC) in neonatal rat oligodendrocytes and that synthetic oxidized phosphatidylcholine (1-palmitoyl-2-(5′-oxo)valeryl-sn-glycero-3 phosphorylcholine, POVPC) also induced apoptosis in neonatal rat oligodendrocytes. POVPC activated caspases 3 and 8, and neutral sphingomyelinase (NSMase), but not acid sphingomyelinase. Downstream pro-apoptotic pathways activated by POVPC treatment included the Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) proapoptotic cascade and the degradation of phospho-Akt. Activation of NSMase occurred within 1h, was blocked by inhibitors of caspase 8, increased mainly C18 and C24:1-ceramides, and appeared to be concentrated in detergent-resistant microdomains (Rafts). We conclude that OxPC initially activates NSMase and converts sphingomyelin into ceramide, to mediate a series of downstream pro-apoptotic events in oligodendrocytes.

Keywords: oligodendroytes, caspases, sphingomyelinases, peroxides, oxidized phosphatidylcholine

Introduction

Oxidized phosphatidylcholine and OxPC-apolipoproteins have been characterized in tissues of patients with inflammatory disease (Friedman et al., 2002; Edelstein et al., 2003). The sn-2 polyunsaturated fatty acids in phosphatidylcholine are oxidized by ROS to fatty acid hydroperoxides, malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxynonenal (Friedman et al., 2002) and OxPC, most commonly 1-palmitoyl-2-arachidonoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphorylcholine. OxPC then forms a covalent Schiff base and Michael-type adducts with lysine residues or the oxidized-aldehyde-containing phospholipids can undergo aldol condensation and polymerization to form antigenic polymers. The OxPC antigen (POVPC) is specifically recognized by both the B-1 cell natural antibody T15, and the experimentally derived monoclonal antibody EO6 (Chang et al., 2004). The pathological significance of the POVPC antigen (Shaw et al., 2000; Friedman et al., 2002; Chang et al., 2004) was suggested by the fact that it was a highly effective competitor of EO6 binding to OxLDL. Further, both the EO6 antibody and the POVPC adduct with lysine or BSA were able to block the binding and uptake of OxLDL by macrophages (Chang et al., 2004). A recent report (Chang et al., 2004) suggests that thymocytes undergoing apoptosis also generate OxPC on their cell surface and it was concluded that apoptosis leads to generation of immunostimulatory, oxidation-specific neoepitopes which could induce autoimmune responses. Recent work from this laboratory (Qin et al., 2007) showed that both OxPC and OxPC-modified protein could be detected in brain of patients with the inflammatory demyelinating disease multiple sclerosis. Since oxidative stress may activate sphingomyelinase-dependent apoptotic pathways leading to ceramide formation (Walton et al., 2006: Jana & Pahan, 2007) and based on the detection of OxPC in autopsy brain samples from patients with demyelinating disease, we sought to evaluate the generation and mechanism of action of OxPC in neonatal rat oligodendrocytes (NRO).

In neurodegenerative disease it is likely that OxPC, and proteins modified by the OxPC generated by neuroinflammation, may be involved in abnormal signaling and the aim of this work was to try to identify these interactions. Since there is also growing in vivo evidence to support the idea that regulation of ceramide is critical to normal brain function and prior evidence in smooth muscle cells (Loidl et al., 2003) that OxPC could activate NSMase we initially looked at sphingomyelinases and the role of ceramide in POVPC action. Previous work has suggested that ceramide levels may be elevated in neurodegenerating brain (Puranam et al., 1997) and ceramide levels have been shown to increase in both cultured neurons (Wiesner & Dawson, 1996; Yu et al., 2000, Venkatamaran & Futerman, 2000) and oligodendrocytes (Testai et al., 2004a) undergoing apoptosis, conditions which are said to generate POVPC, at least in thymocytes (Chang et al., 2004). Ceramide has been implicated as either an effector or an enhancer in both the death receptor (cytokine) and stress (Akt/bcl2 family) pathways which lead to cell death (Goswami & Dawson, 2000, Chalfant et al., 2002) and ceramide is unique in its ability to causing mitochondrial membrane permeability and cytochrome c release (Siskind et al., 2006). Many studies implicate a neutral sphingomyelinase (NSMase2) as the source of this ceramide in apoptosis (Kolesnick & Hannun, 1999; Karakashian et al., 2004; Wiesner et al., 1997; Marchesini et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2004; Testai et al., 2004a; Chen et al., 2006). An important role for ASMase in generating pro-apoptotic ceramide has also been observed in neuronal cerebral ischemia (Yu et al., 2000) and cytokine action (Gulbins & Kolesnick, 2002), so it was important to assess the relative contribution of these two SMases in cell death. OxPC has been shown to play an important, if controversial role in lung injury (Nonas et al., 2006) where it attenuates Toll-like receptor 9-mediated NFκB activation (Ma et al., 2004) so we initiated this study to determine which signaling pathways might be activated by POVPC in primary oligodendrocyte cultures (NRO).

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and Drugs

NBD-C6-sphingomyelin, NBD-C6-Erythro-ceramide and C2-ceramide were purchased from Matreya Inc. (Pleasant Gap, PA). Staurosporine, MTT, H2O2, GW4869, Myriocin Immobilon-P, Superblock, anti-mouse conjugated secondary antibodies, PeroxiDetect™ kit, and Hoechst 33285, were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). POVPC was from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc. (Alabaster, AL). Silica gel HPTLC plates were from Whatman (Clifton, NJ) and the BioRad protein assay kit was from BioRad (Hercules, CA). Chloroform, methanol, and acetic acid used for HPTLC were ACS grade from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). Constructs containing the genes for SMS1 and SMS2 were generous gifts from Dr.Christophe Poirier (University of Chicago). HMU-PC was purchased from Moscerdam Substrates, Amsterdam, Holland. Centricon YM-10 was from Amicon/Millipore Corp. (Bedford, MA). RT-PCR primers for NSMase2 were from Integrated DNA Technologies(Coralville, IA). Monoclonal antibody EO6 was a generous gift from Dr. J. Witztum (University of California, San Diego). The antibodies for NSMase2, p-AKT and p-SAPK/JNK were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA) and Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA), respectively.

Cell culture

NRO were isolated by the Bottenstein (1986) modification of the method of McCarthy and deVellis (1980) in which the first shake is done at 7 days and then at one week intervals with shakes 2–4 giving the highest yield of astrocyte and microglia free oligodendrocyte (NRO) preparations (Scurlock & Dawson, 1999; Testai et al., 2004a). NRO were differentiated for 6 days prior to use.

HOG cells were grown in monolayers on 60 or 100 mm tissue culture dishes in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% gentamicin. HOG cells were originally derived from a human oligodendroglioma and express some characteristics of immature oligodendrocytes (Post & Dawson, 1992; Buntinx et al., 2003).

Generation of stably transfected cell lines

The Vector pCMV 3X-FLAG (Sigma) was used to overexpress NSMase2 in HOG cells. Stable clones were selected on the basis of neomycin (G418-sulfate) resistance (Goswami et al., 2005) and cultured in the presence of neomycin as described above. SMS catalyzes the conversion of ceramide and phosphatidylcholine to sphingomyelin and diacylglycerol. To study ceramide/sphingolipid homeostasis we cloned SMS1 (mouse cDNA using an ECOR1 site) into expression vector pCAGGS, which has a chicken c-actin promoter with rabbit beta-globin polyA tail and SMS2 into pCMV sport6 vector (Invitrogen Inc) (Goswami et al., 2005). Following transfection by electroporation, stable clones were established using neomycin selection as described previously for NSMase2 overexpression (Goswami et al., 2005). All clones were assayed for SMS activity by in vitroassay as described below.

Reverse Transcriptase–Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) for NSMase2 mRNA Expression in NRO with or without treatment by POVPC

Total RNA was extracted from cultured neonatal oligodendrocytes (NRO) with or without POVPC treatment using Qiagen total RNA extract kit (Valencia, CA), RT-PCR were executed by RT-PCR one step kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and primer-pairs specific to a rat NSMase2 fragment sequence (973bp), by using Upper 5′ TACATCGCCTGTACACACCTGCAT 3′ and Lower 5′ TGAACCCTGGACAAAGCTCGAGAA3′ primers. Briefly, the reaction mixture was prepared in PCR tubes according to the kit menu and put into a Perkin Elmer GeneAMP PCR System 2400. The programming RT-PCR procedure consisted of reverse transcription (50°C for 30 min), initial PCR activation (95°C for 15 min), then 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 sec., 55°C for 30 sec. and 72°C for 1 min, followed by a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. The RT-PCR amplified samples were visualized on 1.2% Agarose gels using ethidium bromide.

Sphingomyelinase assay

Cells were treated with drugs at the concentrations and times indicated, harvested, and washed with PBS, and the pellets were resuspended and lysed in 25 mM Tris.HCl, 150 mM NaCl and 1% Triton X-100, pH 7.4 and aliquots (10–20 μg protein) mixed with the fluorogenic substrate HMU-PC (Testai et al., 2004a, b). For NSMase the incubation was at 37 °C in pH 7.4 PBS containing 0.5 mM MgCl2. The presence of phosphate was previously shown to inhibit any ASMase activity (Testai et al., 2004a). For ASMase the incubation was done at pH 4.5, 150 mM sodium acetate buffer containing 1mM EDTA to block any NSMase activity. The HMU released was followed fluorometrically in a 96-well FLX microplate reader. The enzyme activity was calculated from the slope of the graph of intrinsic fluorescence plotted against time and standardized by μg of protein (Testai et al., 2004a, b).

Sphingomyelin synthase assay

Cells (106) were treated as described and mechanically harvested cells were homogenized and 2+sonicated in 0.2 ml of 10mM Tris.HCl buffer pH 7.4 containing 1 mM EDTA and no Mg2+. Extracts (50 μg protein) were incubated at 37°C with NBD-Cer (1 μg) and exogenous PC (20 μg) as the phosphorylcholine donor as described previously (Yamaoka et al., 2004; Taguchi et al., 2004) for up to 24h. The fluorescent NBD metabolites were extracted with chloroform-methanol (2:1:0.01N-HCl v/v), the lower phase subjected to HPTLC and NBD-lipids quantified with a BioRad Chemi-doc XRS scanner, using Quantity One software.

Analysis of Ceramides and sphingosines by LC/MS/MS

Analyses of ceramides were performed via combined liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) by Dr.Evgeny Berdyshev, the University of Chicago, Dept of Medicine Core Facility as described previously (Kilkus et al., 2008). C17-Cer (30.0 pmols) was used as the internal standard. The API-4000 Q-trap triple quadrupole-ion trap hybrid mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) was interfaced with an automated Agilent 1100 series liquid chromatograph and autosampler (Agilent Technologies, Wilmington, DE). The sphingolipids were ionized via electrospray ionization (ESI) with positive ion ESI detection and multiple reaction monitoring (MRM).

Caspase Assays

Cells were treated with drugs at the concentrations and times indicated, harvested, and washed with PBS, and the pellets were resuspended and lysed in 25 mM Tris.HCl, 150 mM NaCl and 1% Triton X-100, pH 7.4. Hydrolysis of the caspase 3 (DEVD-AFC) or the caspase 8 (IETD-AFC) substrates was determined using 5–10 μg of cell extract in 100 μl of 25 mM HEPES buffer containing 2 mM dithiothreitol and 5 mM EDTA, pH 7.4. The reaction was followed for 3 hr in an FLX microplate fluorescence reader at 37°C set at 400 nm excitation and 505 nm emission. Enzyme activity was calculated from the slope of intrinsic fluorescence plotted against time and standardized by μg of protein.

Isolation of Detergent-Resistant Membranes

Cell pellets were lysed in 1.5 ml of 25 mM MES, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM Na3VO4, pH 6.5, supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail [leupeptin, phenylmethylsulfonyfluoride (PMSF), and aprotinin] for 1 hr at 4°C. After being homogenized 10 times in a loose-fit Dounce homogenizer, lysates were mixed with 1.5 ml of 80% sucrose in MBS (25 mM MES, 150 mM NaCl, pH 6.5) and overlayered with 3 ml 30% sucrose in MBS and then with 3 ml of 5% sucrose in MBS. After centrifugation for 18 hr at 31,000 rpm in an SW40 rotor, 1ml fractions were collected. The Raft fraction was typically found between fractions 3 and 4 and is flotillin-2 positive (Kilkus et al., 2003). The 1ml fractions were concentrated by centrifugation through Centricon YM-10 cellulose filters with a 10 kDa molecular weight cutoff and analyzed for lipids by HPTLC, for protein and for enzymatic activity.

Cell viability assays

Cells were plated in 24 well culture plates for MTT assay, which was carried out as described previously (Wiesner et al., 1997). DNA fragmentation was determined as the soluble DNA secreted into the culture medium following induction of apoptosis (Dawson et al., 2004). Quantitation was done by reference to calf DNA and the fluorescence from DNA binding to Hoechst 33258, as described previously (Dawson et al., 2004).

Measurement of lipid hydroperoxide formation by H202 treatment of NRO

NRO were treated with 200 μM H2O2 for 1h. The lipids were extracted in chloroform:methanol as previously described (Qin et al., 2007) and the lipid hydroperoxides were measured by using the PeroxiDetect™ kit and according to manufacture’s instructions.

The EO6 monoclonal antibody detection of OxPC epitope formation in NRO

Lipids were extracted with chloroform: methanol (C-M) (2:1 v/v), concentrated under nitrogen to prevent further oxidation, resuspended in 10ul of C-M (2:1) then applied as a dot to the IP membrane. Detection of oxidized products with mouse monoclonal antibody EO6 was performed by first blocking the Immobilon-P membrane with Superblock (Pierce) for 2h at room otemperature followed by incubation overnight at 4 °C with EO6 (1:500 dilution) in 10% Superblock. After washing (3 times for 20 min each), the membrane-bound antigens were visualized with goat anti-mouse IgM (mu-chainspecific) alkaline phosphatase-conjugated antibody (1:4,000 dilution). The dot blots were scanned by a Bio-Rad ChemiDoc XRS and the images quantified in Quantity One 4.5.0 software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Hydrogen peroxide induced formation of OxPC in NRO detected by immunofluorescence staining

NRO were grown in 4-well tissue culture slides, and treated with or without 100 μM H2O2 for 1–24h. Cells were rinsed in PBS 2 times and fixed in freshly prepared 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 1h. After removing the fixative and rinsing 3 times with PBS, the slides were incubated in PBS/1% Triton X-100 for 10 min at room temperature, then PBS/1% Triton X-100/2% normal goat serum (NGS) for 5 min at room temperature 3 times for a total of 15 min. The primary mouse antibody EO6 was diluted in PBS/1% Triton X-100/2% NGS (1:200) and incubated with cells overnight at 4 °C. After rinsing 6 times with PBS for 5 min at room temperature, cells were incubated with the secondary antibody anti-mouse IgM-Cy3 (1:1000) for 1 h, then rinsed with PBS. 1 Drop of 2% n-propyl gallate in PBS:glycerol (1:1) was added to each well and the slide sealed with nail polish. The immunofluorescence reaction was followed and microscopy documented using an Axiovert S100 TV (Carl Zeiss, Inc).

Western blotting of proteins

Protein extracts from cell cultures were subjected to SDS-gel electrophoresis and blotting with antibodies. Western blot analysis was carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions and positive bands were detected with a chemiluminescence kit from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). Representative Western blots were scanned by a Bio-Rad ChemiDoc XRS and the images quantified in Quantity One 4.5.0 software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Statistical analysis

Results are based on experiments run in triplicate (n=3) at least twice. Statistical analyses were performed by Student’s t-test and results were considered statistically significant when p<0.05.

Results

H2O2 and POVPC treatment increased cell death in a dose-dependent manner

NRO cells were incubated overnight with different concentrations of H202 or POVPC and induced apoptosis was measured by both the MTT and the DNA fragmentation assays (Fig. 1). H2O2 (panels A and B) and POVPC (panels C and D) induced cell death in a dose dependent manner. The IC50 for H2O2 and POVPC were approximately 100 μM and 15 μM, respectively. Phase microscopic examination of the NRO cells (panels E and F) revealed significant loss of processes after 1h of 10 μM POVPC treatment with retention of many cell bodies, which were intact as measured by the MTT assay.

Fig. 1. Viability studies on NRO cells incubated with H2O2 or POVPC.

NRO cells were incubated 18 hours with H2O2 (A and B) or POVPC (C and D). Both treatments induced apoptosis measured by DNA fragmentation (A and C) and MTT assay (B and D) in a dose-dependent manner. E: Phase microscopic appearance of NRO used in these studies. F: Phase appearance after treatment with 10 μM POVPC for 1h, showing loss of processes with maintenance of intact cell bodies. Results are based on triplicate experiments run in triplicate (n=3) Similar results were obtained with HOG cells (data not shown).

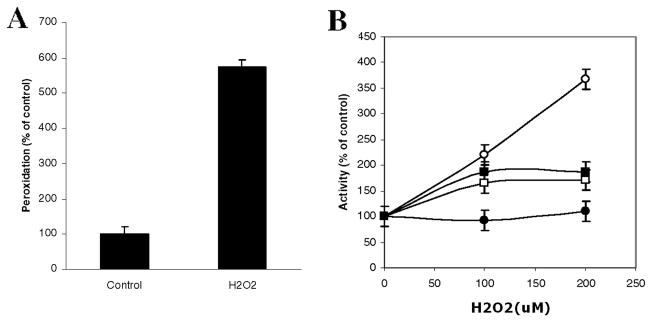

H2O2 generates peroxides and activates caspases 3 and 8 and NSMase but not ASMase in NRO

NRO treated with 200 μM H2O2 generated lipid hydroperoxides as quantified by the PeroxiDetect™ kit (Fig. 2A). After as little as 1h incubation with increasing concentrations of H2O2 the activity of caspases 3 and 8 and NSMase increased, whereas ASMase activity remained unchanged (Fig. 2B). Similar results were obtained with HOG cells (data not shown, Fig. 8 and Qin et al (2008)).

Fig. 2. H2O2 generates peroxides and activates caspases 3 and 8 and NSMase but not ASMase in NRO.

A: Cells were treated with H2O2 and peroxidation measured as described in the text. B: NRO cells were incubated for 1h with increasing concentrations of H2O2. The activity of caspases 3 (■) and 8 (□) and NSMase (○) increased in a dose-dependent manner while ASMase (●) activity remained unchanged. Results are based on duplicate experiments run in triplicate (n=3)

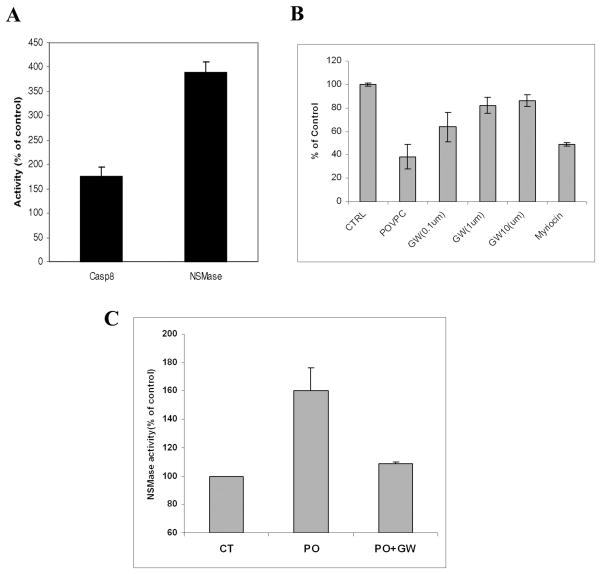

Fig. 8. Evidence for activation of caspase 8 and NSMase in Rafts of HOG cells and NSMase inhibitor GW4869 protect POVPC induced HOG cell apoptosis.

A: HOG cells were incubated with and without POVPC (10 μM) for 1h and showed similar elevations of caspase 8, NSMase and caspase 3 as observed in NRO. HOG cells were harvested and the Raft fraction isolated by sucrose-density gradient fractionation as described in the text. Both caspase 8 and NSMase activities were seen to be elevated in the Raft fraction (Fraction 4 in the sucrose-density gradient) when expressed as percentage relative to control cells.

B: HOG cells were pre-incubated with and without NSMase inhibitor GW4869 (0.1, 1 and 10 μM GW) and SPT inhibitor Myriocin (5 μM) for 30 minutes, prior to adding POVPC (15 μM) for a further 24 h. Control (CTRL) is 100%. Cell viability was determined by MTT assay.

C: HOG cells were pre-incubated with and without GW4869 (10 μM), for 30 min., POVPC (15 μM) was added (PO), cells were incubated for an additional 2 h., harvested and NSMase activity compared to control (CT). All results are based on 2 experiments run in triplicate.

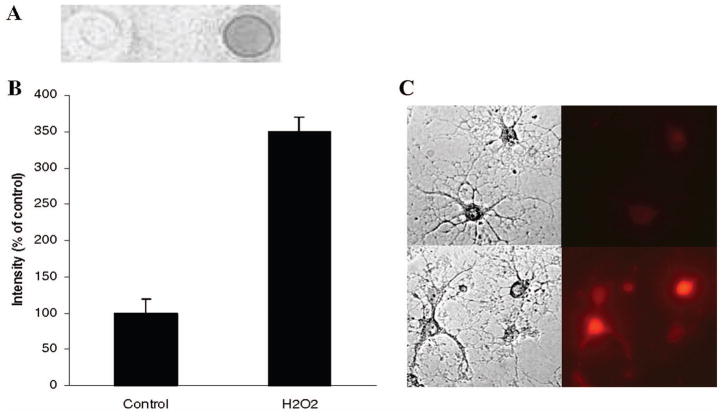

Treatment of culture neonatal rat oligodendrocytes (NRO) with H2O2 induces EO6 positive staining

Cultured oligodendrocytes treated briefly (1h) with 200 μM H2O2 showed a dramatic increase in lipid EO6 immunoreactivity and this increased over a period of 48h at lower concentrations of H202, such as 100 μM (Fig. 3A). Quantification of the dot blot analysis of lipid extracts following similar treatment showed the formation of OxPC was 3.5-fold (Fig. 3B). Staining of NRO with EO6 as described in methods showed the increased staining of the cells and processes (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3. Immunocytochemistry with EO6.

A: Dot blot of NRO lipids before (left) and after (right) treatment with H2O2 and detection of OxPC with the EO6 monoclonal antibody as described in the text.

B: Quantification of the dot blot shown in Panel A.

C: Staining of NRO with EO6

Upper panels: Phase contrast image and fluorescent staining of untreated NRO.

Lower panels: Phase contrast image and fluorescent staining of NRO treated for 1h with 100 μM H2O2. Fluorescent staining was done with EO6 as the primary antibody as described in the text. Results are based on duplicate experiments run in triplicate (n=3)

POVPC activates caspase 3 and 8 and NSMase (but not ASMase) and increases C18:0 and C24:1 ceramides levels

NRO cells were incubated with increasing concentrations of POVPC for 1h. The cells were harvested and the activity of capases 3 and 8 and SMases determined as described methods. POVPC activated caspases 3 and 8 and NSMase by 2 to 4-fold in NRO in a dose-dependent manner whereas ASMase and other lysosomal enzymes, such as PPT, were unaffected (Fig. 4A–B). The cells were also incubated with 10 μM of POVCP for different periods of time. Caspases 3 and 8 and NSMase activation occurred within the first 30–60 min whereas ASMase and other lysosomal enzymes, such as PPT, were unaffected (Fig. 4C–D). Similar results were observed in HOG cells (data not shown). MS analysis (see Supplemental Table 1) showed that the 40% increase in ceramides observed following POVPC treatment was mainly in the C18:0 and C24:1 species.

Fig. 4. POVPC activates caspase 3, 8 and NSMase in NRO cells.

A: Activity of caspase 3 (■) and 8 (□) in NRO cell extracts following 1h of incubation with different concentrations of POPVC. Palmitoyl-protein thioesterase activity (△) was also measured in similar conditions and used as a negative control.

B: Activity of NSMase (○) and ASMase (●) in NRO cell extracts following 1h of incubation with different concentrations of POPVC.

C: Time course of caspase 3 (■) and 8 (□) activities following incubation of NRO cells with POPVC 10 μM for 30 min, 1h and 2h. Palmitoyl-protein thioesterase activity (△) was also measured in similar conditions and used as a negative control.

D: Time course of NSMase (○) and ASMase (●) activities following incubation of NRO cells with POPVC 10 μM for 30 min, 1h and 2h. Similar results were obtained with HOG cells (Fig. 8). Results are based on 3 experiments run in triplicate (n=3)

POVPC increases NSMase2 expression and protein levels in NRO as measured by by RT-PCR and Western blot

NRO cultures were incubated with or without POVPC (0, 10 μM and 20 μM POVPC) for 2h, cells were harvested and total RNA and protein were extracted. RT-PCR (Fig. 5A) and Western blot analyses (Fig. 5B, C) were carried out and we could show that both NSMase2 mRNA and protein expression levels increased in POVPC-treated cells compared to that without treatment cells (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. NSMase2 expression increased in NRO treated by POVPC.

A: RT-PCR showing increased NSMase2 expression in POVPC treated cells.

Lane 1, NRO without POVPC treatment; Lane 2 and 3, NRO with POVPC treatment (10 and 20 μM POVPC for 2 hrs); Lane 4, Blank, 18s rRNA as control.

B and C: Western blot showing increased NSMase2 expression in POVPC treated cells.

Lane 1, NRO without POVPC treatment; Lane 2 and 3, NRO with POVPC treatment (10 and 20 μM POVPC for 2 hrs), β-actin as control. Results are representative of 3 experiments.

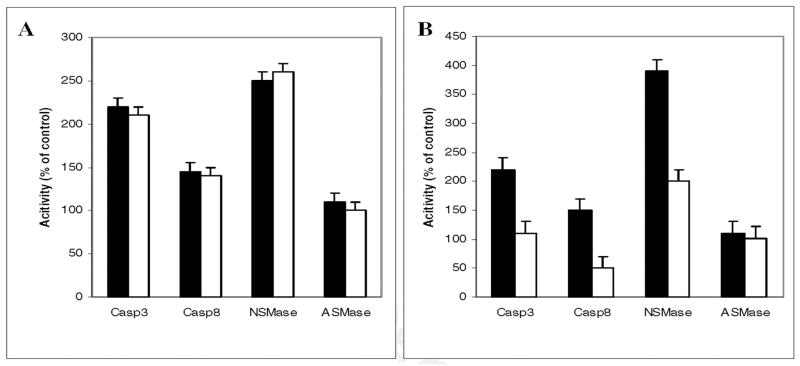

OxPAPC also activates caspase-8, NSMase and caspase 3

Another OxPC (OxPAPC, generated by exposing 1-palmitoyl-2-arachidonoyl-sn-glycero-3--phosphorylcholine to air for 72h) was also a potent an activator of caspases 3 and 8 and NSMase as was POVPC (Fig. 6A). The activation of caspases 3 and 8 and NSMase was selectively blocked by treatment with caspase 8 inhibitor IETD-fmk (Fig. 6B) confirming that they are downstream of caspase 8.

Fig. 6. Comparable effect of POVPC and OxPAPC on NRO pro-apoptotic enzymes.

A: NRO cells were incubated for 1h with OxPAPC (open bars) or POVPC (solid bars) 10 μM. The cells were harvested and the activities of caspase 3, caspase 8, NSMase and ASMase determined and expressed as percentage of the control.

B: NRO cells were incubated for 1h with POVPC (10 μM) in the presence (solid bars) and absence (open bars) of the caspase 8 inhibitor IETD-fmk (20 μM). The cells were harvested and the activities of caspase 3, caspase 8, NSMase and ASMase determined and expressed as percentage of the control. Results are based on 2 experiments run in triplicate. Similar results were obtained with HOG cells (Fig. 8).

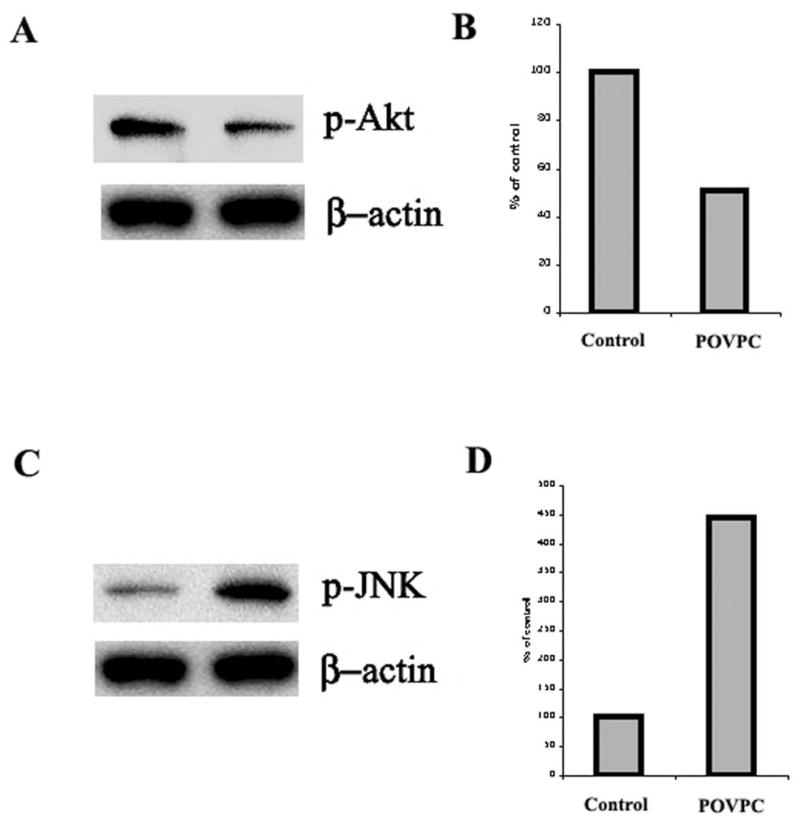

POVPC treatment of NRO decreases P-Akt and increases P-JNK

NRO cultures were treated for 1h with POVPC (10 μM), proteins extracted in SDS and blotted against antibodies specific for p-Akt and p-JNK (Fig. 7A, B). There was a 50% reduction in p-Akt (without loss of Akt (data not shown)) and a >4-fold increase in p-JNK (Fig. 7C, D).

Fig. 7. Selective inhibition of p-Akt and activation of p-JNK by POVPC.

A: Western blot showing 50% p-Akt inhibition by POVPC with β-actin as control. B. Quantification.

C: Western blot showing >4-fold p-JNK activation by POVPC with β-actin as control. Experimental details are given in the text. D: Quantification. Results are representative of triplicate experiments.

NSMase is recruited into detergent-rich microdomains by POVPC and inhibitor GW4689 to NSMase can block NSMase activity and protect cells from death

POVPC was able to activate NSMase and cause cell death in other cell lines such as a Human oligodendroglioma cell line (HOG). Detergent resistant microdomains (Rafts) were prepared from HOG cells by sucrose-density gradient fractionation as described previously (Kilkus et al., 2003). POVPC pre-treatment increased caspase 8 and NSMase activity specifically in the Raft fraction (Fig. 8A), as we have previously reported for staurosporine in HOG cells (Kilkus et al., 2003). Caspase 3 only increased in the non-Raft fraction (Testai et al., 2004a) (data not shown). HOG cells were pre-incubated with and without NSMase inhibitor GW4869 (0.1, 1 and 10 μM) and SPT inhibitor Myriocin (5 μM) for 30 min. followed by POVPC (15 μM) for 24 h. The MTT assay, showed that GW4869 can significantly increase cell viability whereas Myriocin did not (Fig. 8B). This suggests that the ceramide is of catabolic rather than biosynthetic origin as has been suggested in ischemia (Chudakova et al., 2008). We determined if GW4869 was actually inhibiting NSMase in HOG cells by pre-incubating with and without GW4869 (10 μM), for 30 minutes and then adding POVPC (15 μM) for an additional 2 h. Assay of NSMase activity showed that GW4869 reversed the POVPC activation of NSMase activity (Fig. 8C). Our results indicate that POVPC induces cell apoptosis mainly through the NSMase pathway rather than ASMase or activation of ceramide synthases.

Effect of SMS1, SMS2 and NSMase2 overexpression on the formation of NBD-SM from exogenous NBD-Cer in intact HOG cells and HOG cell homogenates

These studies were done in HOG cells since we can select for homogeneous cells all overexpressing the gene selected. The in vitro assay of sphingomyelin synthase in both SMS1 and SMS2 overexpression clones showed a more-than two fold higher activity than in HOG wild type (Fig. 9A). HOG cells were incubated for 1h with POVPC 10 μM and a 1.8-fold increase in caspase 3 activity was observed (Fig. 9B). In contrast, caspase 3 activity was unaffected by POVPC in SMS1 and SMS2 overexpressing cells (Fig. 9B).

Fig. 9. Effect of SMS overexpression on POVPC-induced activation of caspase 3.

A: Sphingomyelin synthase assay in homogenates of HOG cells in which SMS1 and SMS2 were stably overexpressed as described in the text. Results are based on 2 experiments run in triplicate.

B: HOG cells (wild type (WT) and overexpressing SMS1 and SMS2) were incubated for 1h with or without POVPC 10 μM. Caspase 3 activity was determined and expressed as percentage of the control shows that there was no elevation when SMS1 or SMS2 were stably overexpressed. Results are based on 2 experiments run in triplicate.

C: HPTLC chromatogram visualized by fluorescence intensity as described in the text. Intact, wild type (control) and HOG cells stably expressing NSMase2 (NSMase), SMS1 or SMS2 were incubated with NBC-ceramide for 3h, the lipids isolated by HPTLC, and the data for conversion to NBD-SM shown. NSMase decreases NBD-SM, whereas SMS1 and SMS2 increase it. Results are representative of triplicate experiments.

Experimental details are in the text.

Functional effects of SMS expression were verified by adding NBD-ceramide to intact SMS1 or SMS2 cells (Kilkus et al., 2008) and showing 2-fold increased conversion to SM compared to control or NSMase2 overexpressing cells (Fig. 9C). A scheme to explain these findings is illustrated (see Supplemental Fig.S1).

Discussion

Oxidative stress has been implicated in neurodegenerative disease pathogenesis and our previous work has implicated ROS, OxPC (POVPC), covalent modification of protein, disruption of RAGE function and a role for ceramide in this process in oligodendrocytes (Qin et al., 2007; 2008). For example, the demyelination and axonal degeneration associated with acute and chronic phases of Multiple Sclerosis (MS) have been associated with ROS from infiltrating macrophages and microglia, oxidation of sn-2 polyunsaturated fatty acids to form OxPCs such as POVPC, and adduct formation of these aldehydes with protein (Qin et al., 2007). The lack of accumulation of lipid peroxidation products in either grey matter or white matter from MS brains (Bizzozero et al., 2005) (in which free MDA and HNE were measured by the N-methyl-2-phenylindole method), could be explained by the ability of OxPC and HNE to form protein adducts (Berlett & Stadtman, 1997; Edelstein et al., 2003; Qin et al., 2007). Lipid peroxidation is a common process, most likely initiated by oxidative bursts from activated leukocytes or various metal ions (Berlett & Stadtman, 1997; Edelstein et al., 2003; Leitinger, 2005 ). In some tissues such as lung OxPC (and its synthetic analog POVPC) has a normal protective function in maintaining the EC barrier (Birukova et al., 2008), whereas in others such as aorta it has pro-inflammatory action (Leitinger, 2005). Although we can theorize as to how POVPC is generated in brain, we know less about what it does in brain. We now show that peroxide-stimulated oligodendrocytes can readily convert PC into POVPC and that POVPC triggers cell death by activating neutral sphingomyelinase (NSMase2) and generating specific increases in C18:0 and C24:1 ceramides.

Oxidized phosphatidylcholine(OxPC) is often associated with inflammation and pathogenesis and Isoprostane-containing OxPLs such as POVPC have been estimated to occur at 30–100 times the normal concentration(1 ng/g wet wt.) in atherosclerotic vessels (Leitinger, 2005). Their adducts with lipoproteins have been shown to disrupt LDL receptors, cholesterol homeostasis and lead to foam cell formation and atherogenesis, suggesting that the mechanism of OxPC is through receptors. POVPC and PGPC (1 palmitoyl-2-glutaroyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphorylcholine) can inhibit smooth muscle cell proliferation and are cytotoxic (Fruhwirth et al., 2006). Several morphological criteria, the presence of typical DNA fragments, and a phosphatidylserine shift towards the outer leaflet of the cell membrane suggested that POVPC-induced apoptosis was the predominant mode of cell death. In this study, POVPC-treatment led to loss of processes prior to initiation of apoptosis but the mechanism for this is not known.

POVPC was generated by and was able to mimic the pro-apoptotic actions of hydrogen peroxide in terms of ceramide increase without the other actions of hydrogen peroxide such as the release of soluble RAGE (Qin et al., 2008). The concentrations used to get the effects (5–10 μM) were comparable to those used in many previous studies (Chen et al., 2007; Birukova et al., 2008). POVPC induced the activation of caspase 8, neutral sphingomyelinase (to produce ceramide) and caspase 3 (apoptosis) as previously observed in NRO for pro-apoptotic drugs such as staurosporine (Testai et al., 2004a). The observed increase in ceramides paralleled the reduction in anti-apoptotic phospho-Akt. POVPC-induced apoptosis was blocked by both caspase-8 (IETD-fmk) and NSMase inhibitors (GW4869). However, it should be noted that although IETD-fmk is a potent inhibitor of caspase 8 it does show significant cross-reactivity towards caspases 8 and 9 (Berger et al., 2006). As with staurosporine-mediated NRO cell death (Testai et al., 2004a) acid sphingomyelinase (ASMase) did not seem to be involved. Our findings therefore differed from those of Loidl (2003) who claimed that POVPC induced apoptotic signaling in muscle cells via activation of ASMase. Oxidative stress is part of the process of inflammation (Leitinger, 2005) and POVPC also activated the JNK pathway. Again, the mechanism appeared different from that in non-neural cells such as lung, where high OxPC levels are normal and POVPC inhibits inflammation by suppressing the major LPS receptor TLR4, inactivating the co-receptors LBP and CD14 (Nonas et al., 2006; Birukova et al., 2008) and partially inhibiting IL-6 action via JAK-STAT, PI3 kinase/Akt and MAP kinase.

Relatively little is known about POVPC acting as a ligand. There is evidence for multimeric [OxPC]-n-BSA acting as a multivalent ligand for the CD36 scavenger receptor on macrophages and an equally potent ligand was made by coupling a lysyl-peptide to POVPC (Ac-TGT[POVPC-K]GY (Boullier et al., 2005)). Other studies suggest a direct action for OxPCs, for example, OxPAPC (oxidized 1-palmitoyl-2-arachidonoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphorylcholine) acting via a Gs protein-coupled receptor (Li et al., 2006). POVPC has been shown to bind to cultured human macrophages via the PAF receptor and both transduces the signals leading to the intracellular Ca2+ fluxes, and modifies the transcription levels of numerous pro-inflammatory and pro-atherogenic genes (Pegorier et al., 2006). POVPC can regulate transcription via NF-κB (Papa et al., 2004) and our data is consistent with it signaling through other pro-apoptotic pathways associated with cytokine receptors such as TRADD-TRAF2-MAP kinases (Gulbins&Kolesnick, 2002) and activation of the JNK-Bid-Smac/Diablo link to the intrinsic (mitochondrial) pathway (Papa et al., 2004). We also showed that POVPC transcriptionally increases both NSMase message RNA and protein. The classical pro-apoptotic, caspase-8-Bid-cytochrome-c pathway (shared by many cytokine receptors) is enhanced by the ability of caspase-8 to activate neutral sphingomyelinase (Testai et al., 2004a; Marchesini et al., 2003; Goswami et al., 2005). The ceramide generated may then activate a phospho-Akt-phosphatase (Chalfant et al., 2002; Goswami et al., 1999) which in turn activates the Bad-Bax-Bid complex, leading to mitochondrial-directed apoptosis (Kolesnick & Hannun, 1999; Siskind et al., 2006). However, Chen et al., (2007) have shown that cytotoxic phospholipid oxidation products can activate the intrinsic caspase cascade by direct mitochondrial damage similar to that reported to be caused by ceramide (Siskind et al., 2006), suggesting that more than one mechanism may be involved.

Maintenance of ceramide-sphingomyelin homeostasis in neural cells controls the balance between life (diacylglycerol) and death (Ceramide) and is obviously critical at all times of development (Gulbins&Kolesnick, 2002; Kolesnick & Hannun, 1999; Kilkus et al., 2008). In this study and others (Kilkus et al., 2008) it was shown that overexpressing sphingomyelin synthases (which convert Ceramide back to SM) protected against cell death, as originally suggested by Yamaoka et al. (2004). Therefore the regulation of sphingomyelin-ceramide homeostasis (Kilkus et al., 2008; Tafesse et al., 2006; 2007) is an important neural cell function necessary for survival. POVPC increases ceramide in oligodendrocytes by activating NSMases and pushes the equilibrium towards pathogenesis. We showed that both SMS1 and SMS1 were able to block this, presumably by depleting ceramide. Phospholipid oxidation to OxPAPC inhibited the LPS-mediated induction of IL-8 in endothelial cells and in smooth muscle cells via activation of NSMase and formation of ceramide in detergent-rich microdomains (DRMs) (Walton et al., 2006). POVPC and OxPAPC increased caspase 8 and NSMase in DRMs in much the same way that cytokines activated this death pathway, suggesting that POVPC action most likely occurs in detergent-rich microdomains (DRMs) or Rafts (Kilkus et al., 2003). Such microdomains are controversial because their isolation depends upon detergent solubilization. However, recent studies have shown that DRMs may be analogous to natural small lipid vesicles (exosomes) derived from the intraluminal membranes of multivesicular bodies. These are likely involved in exchange of membrane proteins in the brain and their composition is very similar to that of detergent-isolated DRMs (Trajkovic et al., 2008). In addition their secretion is dependent on NSMase activation and the formation of ceramide (Trajkovic et al., 2008). We have previously shown (Goswami et al., 2005) that activation of caspase-8 with staurosporine leads to the recruitment of SMase, (presumably palmitoylated (Tani and Hannun, 2007)) into DRMs, The ability of POVPC to activate a pathway (NSMase), most likely via a TNF family/cytokine receptor complex responsible for intraendosomal membrane transport, suggests that the overproduction of OxPCs such as POVPC in nervous tissue and concomitant production of ceramide may amplify apoptotic pathways and initiate neurodegenerative processes.

Supplementary Material

We propose the following simplified scheme to explain our data. Generation of peroxides (H202) and reactive oxygen species at the cell surface converts PC to OxPC (shown) and smaller fragments HNE and MDA (not shown). We propose that the OxPC has a higher affinity for detergent-resistant microdomains (Raft) since the sn-2 polyunsaturated fatty acid moiety is lost and this results in activation of pro-apoptotic caspase-8, leading to the recruitment of NSMase2 into rafts. NSMase becomes activated and converts SM to ceramide. Many other death domain and activator/accessory proteins are involved in this complex mechanism but are not shown for simplicity. Ceramide homeostasis is maintained largely by the antagonistic balance of NSMase and sphingomyelin synthase (SMS). Since the latter requires PC for activity, so its activity may be compromized by local membrane formation of OxPC. Elevated ceramide results in activation of an Akt-P phosphatase and activation of the pro-apoptotic Bad/Bax complex leading to cytochrome c release from mitochondria (faciliated by ceramide (or possibly the direct action of OxPC on mitochondria (Chen et al., 2007)), caspase-3, activation and c-Jun-N terminal kinase (JNK) cascade activation, leading to cell death.

Acknowledgments

Supported by USPHS Grant NS36866. We would like to thank Lise Bude for excellent technical assistance in tissue culture and Dr. Evgeny Berdyshev, Dept. Medicine, University of Chicago, for performing the HPLC/MS/MS analyses.

Abbreviations

- ASMase

acid sphingomyelinase

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- DMSO

dimethylsulfoxide

- HMU-PC

hexamethylumbelliferyl-phosphorylcholine

- HNE

4-hydroxynonenal

- HOG

human oligodendroglioma

- HPTLC

high performance thin-layer chromatography

- JNK

Jun-N-terminal kinase

- MDA

malondialdehyde

- MES

2-[N-Morpholino] ethanesulfonic acid

- MTT

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- NSMase

neutral sphingomyelinase

- NRO

neonatal rat oligodendrocytes

- OxLDL

oxidized low density lipoprotein

- OxPC

oxidized phosphatidylcholine

- OxPAPC

oxidized 1-palmitoyl-2-arachidonoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphorylcholine

- PAF

platelet-activating factor

- PtdIns(3, 4,5)P3

phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate

- POVPC

1-palmitoyl-2-(5-oxovaleroyl)-sn-glycero-3-phosphorylcholine

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SMS

sphingomyelin synthase

- SPT

serine palmitoyl transferase

References

- Berger AB, Sexton KB, Bogyo M. Commonly used caspase inhibitors designed based on substrate specificity profiles lack selectivity. Cell res. 2006;16:961–963. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlett BS, Stadtman ER. Protein oxidation in aging, disease, and oxidative stress. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:20313–20316. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.33.20313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birukova AA, Alekseeva E, Cokic I, Turner CE, Birukov KG. Cross talk between paxillin and Rac is critical for mediation of barrier-protective effects by oxidized phospholipids. Amer J Physiol. 2008;295:L593–560. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90257.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bizzozero OA, DeJesus G, Callahan K, Pastuszyn A. Elevated protein carbonylation in the brain white matter and gray matter of patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Res. 2005;81:687–695. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottenstein JE. Growth requirements in vitro of oligodendrocyte cell lines and neonatal rat brain oligodendrocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:1955–1959. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.6.1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boullier A, Friedman P, Harkewicz R, Hartvigsen K, Green SR, Almazan F, Dennis EA, Steinberg D, Witztum JL, Quehenberger O. Phosphocholine as a pattern recognition ligand for CD36. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:969–976. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400496-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buntinx M, Vanderlocht J, Hellings N, Vandenabeele F, Lambrichts I, Raus J, Ameloot M, Stinissen P, Steels P. Characterization of three human oligodendroglial cell lines as a model to study oligodendrocyte injury: morphology and oligodendrocyte-specific gene expression. J Neurocytol. 2003;32:25–38. doi: 10.1023/a:1027324230923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalfant CE, Rathman K, Pinkerman RL, Wood RE, Obeid LM, Ogretmen B, Hannun YA. De novo ceramide regulates the alternative splicing of caspase 9 and Bcl-x in A549 lung adenocarcinoma cells. Dependence on protein phosphatase-1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:12587–12595. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112010200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang MK, Binder CJ, Miller YI, Subbanagounder G, Silverman GJ, Berliner JA, Witztum JL. Apoptotic cells with oxidation-specific epitopes are immunogenic and proinflammatory. J Exp Med. 2004;200:1359–1370. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R, Yang L, McIntyre TM. Cytotoxic phospholipid oxidation products. Cell death from mitochondrial damage and the intrinsic caspase cascade. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:24852–24850. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702865200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Lee JM, Zeng C, Chen H, Hsu CY, Xu J. Amyloid beta peptide increases DP5 expression via activation of neutral sphingomyelinase and JNK in oligodendrocytes. J Neurochem. 2006;97:631–640. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chudakova DA, Zeidan YH, Wheeler B, Yu J, Novgorodov SA, Kindy MS, Hannun YA, Gudz TI. Integrin-associated Lyn Kinase Promotes Cell Survival by Suppressing Acid Sphingomyelinase Activity. JBiol Chem. 2008;283:28806–16. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803301200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson G, Moskal JR, Dawson SA. Transfection of 2,6 and 2,3-sialyltransferase genes and GlcNAc-transferase genes into human glioma cell line U-373 MG affects glycoconjugate expression and enhances cell death. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2004;89(6):1436–1444. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelstein C, Pfaffinger D, Hinman J, Miller E, Lipkind G, Tsimikas S, Bergmark C, Getz GS, Witztum JL, Scanu AM. Lysine-phosphatidylcholine adducts in kringle V impart unique immunological and potential pro-inflammatory properties to human apolipoprotein(a) J Biol Chem. 2003;278:52841–52847. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310425200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman P, Horkko S, Steinberg D, Witztum JL, Dennis EA. Correlation of antiphospholipid antibody recognition with the structure of synthetic oxidized phospholipids. Importance of Schiff base formation and aldol condensation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:7010–7020. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108860200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fruhwirth GO, Moumtzi A, Loidl A, Ingolic E, Hermetter A. The oxidized phospholipids POVPC and PGPC inhibit growth and induce apoptosis in vascular smooth muscle cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1761:1060–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goswami R, Dawson G. Does ceramide play a role in neural cell apoptosis. J Neurosci Res. 2000;60:141–149. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(20000415)60:2<141::AID-JNR2>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goswami R, Kilkus J, Dawson SA, Dawson G. Overexpression of Akt (protein kinase B) confers protection against apoptosis and prevents formation of ceramide in response to pro-apoptotic stimuli. J Neurosci Res. 1999;57:884–893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goswami R, Ahmed M, Kilkus T, Dawson SA, Dawson G. Differential regulation of ceramide in lipid-rich microdomains (Rafts): antagonistic role of palmotoyl:protein thioesterase and neutral sphingomyelinase 2. J Neurosci Res. 2005;81:208–217. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulbins E, Kolesnick R. Acid sphingomyelinase-derived ceramide signaling in apoptosis. Sub-Cellular Biochem. 2002;36:229–244. doi: 10.1007/0-306-47931-1_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jana A, Pahan K. Oxidative stress kills human primary oligodendrocytes via neutral sphingomyelinase: Implications for Multiple Sclerosis. J Neuroimmun Pharmacol. 2007;2:184–193. doi: 10.1007/s11481-007-9066-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karakashian AA, Giltiay NV, Smith GM, Nikolova-Karakashian MN. Expression of neutral sphingomyelinase-2 (NSMase-2) in primary rat hepatocytes modulates IL-beta-induced JNK activation. FASEB J. 2004;18:968–970. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0875fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkus J, Goswami R, Dawson SA, Testai FD, Berdyshev E, Han X, Dawson G. Differential regulation of sphingomyelin synthesis and catabolism in oligodendrocytes and neurons. J Neurochem. 2008;106:1745–1757. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05490.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkus J, Goswami R, Testai FD, Dawson G. Ceramide in rafts (detergent-insoluble fraction) mediates cell death in neurotumor cell lines. J Neurosci Res. 2003;72:65–75. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolesnick R, Hannun YA. Ceramide and apoptosis. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 1999;24:224–225. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01408-5. author reply 227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JT, Xu J, Hsu CY. Amyloid beta-peptide induces oligodendrocyte death by activating the neutral sphingomyelinase-ceramide pathway. J Cell Biol. 2004;164:123–131. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200307017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitinger N. Oxidized phospholipids as triggers of inflammation in atherosclerosis. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2005;49:1063–1071. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200500086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Mouillesseaux KP, Montoya D, Cruz D, Gharavi N, Dun M, Koroniak L, Berliner JA. Identification of prostaglandin E2 receptor subtype 2 as a receptor activated by OxPAPC. Circ Res. 2006;98:642–650. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000207394.39249.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loidl A, Sevcsik E, Riesenhuber G, Deigner HP, Hermetter A. Oxidized phospholipids in minimally modified low density lipoprotein induce apoptotic signaling via activation of acid sphingomyelinase in arterial smooth muscle cells. JBiol Chem. 2003;278:32921–32928. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306088200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Z, Li J, Yang L, Mu Y, Xie W, Pitt B, Li S. Inhibition of LPS-and CpG DNA-induced TNF-alpha response by oxidized phospholipids. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286:L808–816. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00220.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchesini N, Luberto C, Hannun YA. Biochemical properties of mammalian neutral sphingomyelinase2 and its role in sphingolipid metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:13775–13783. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212262200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy K, de Vellis J. Preparation of separate astroglial and Oligodendrogial cell cultures from rat cerebral tissue. J Cell Biol. 1980;85:890–902. doi: 10.1083/jcb.85.3.890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonas S, Miller I, Kawkitinarong K, Chatchavalvanich S, Gorshkova I, Bochkov VN, Leitinger N, Natarajan V, Garcia JG, Birukov KG. Oxidized phospholipids reduce vascular leak and inflammation in rat model of acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:1130–1138. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200511-1737OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papa S, Zazzeroni F, Pham CG, Bubuci C, Franzoso G. Linking JNK signaling to NF-kB: a key to survival. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:5197–5208. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pegorier S, Stengel D, Durand H, Croset M, Ninio E. Oxidized phospholipid: POVPC binds to platelet-activating-factor receptor on human macrophages. Implications in atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2006;188:433–443. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post GR, Dawson G. Characterization of a cell line derived from a human oligodendroglioma. Mol Chem Neuropathol. 1992;16:303–317. doi: 10.1007/BF03159976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puranam K, Qian WH, Nikbakht K, Venable M, Obeid L, Hannun Y, Boustany RM. Upregulation of Bcl-2 and elevation of ceramide in Batten disease. Neuropediatrics. 1997;28:37–41. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-973664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin J, Goswami R, Balabanov R, Dawson G. Oxidized phosphatidylcholine is a marker for neuroinflammation in multiple sclerosis brain. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:977–984. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin J, Goswami R, Dawson S, Dawson G. Expression of the receptor for advanced glycation end products in oligodendrocytes in response to oxidative stress. J Neurosci Res. 2008;86:2414–2422. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scurlock B, Dawson G. Differential responses of oligodendrocytes to tumor necrosis factor and other pro-apoptotic agents: role of ceramide in apoptosis. J Neurosci Res. 1999;55:514–522. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19990215)55:4<514::AID-JNR11>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw PX, Hörkkö S, Chang MK, Curtiss LK, Palinski W, Silverman GJ, Witztum JL. Natural antibodies with the T15 idiotype may act in atherosclerosis, apoptotic clearance, and protective immunity. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1731–1740. doi: 10.1172/JCI8472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siskind LJ, Kolesnick RJ, Colombini M. Ceramide forms channels in mitochondrial outer membranes at physiologically relevant concentrations. Mitochondrion. 2006;6:118–125. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tafesse FG, Ternes P, Holthuis JC. The multigenic sphingomyelin synthase family. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(40):29421–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R600021200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tafesse FG, Huitema K, Holthuis JCM. Both sphingomyelin synthases SMS1 and SMS2 are required for sphingomyelin homeostasis and growth in human HeLa cells. J Biol Chem. 2007:M702423200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702423200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi Y, Kondo T, Watanabe M, Miyaji M, Umehara H, Kozutsumi Y, Okazaki T. Interleukin-2-induced survival of natural killer (NK) cells involving phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase-dependent reduction of ceramide through acid sphingomyelinase, sphingomyelin synthase and glucosylceramide synthase. Blood. 2004;104:3285–3293. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-0900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tani M, Hannun YA. Neutral Sphingomyelinase 2 is palmitoylated on multiple cysteine residues. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:10047–10056. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611249200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testai FD, Landek MA, Dawson G. Regulation of sphingomyelinases in cells of the oligodendrocyte lineage. J Neurosci Res. 2004a;75:66–74. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testai FD, Landek MA, Goswami R, Ahmed M, Dawson G. Acid sphingomyelinase and inhibition by phosphate ion: role of inhibition by phosphatidylmyo-inositol 3,4,5-triphosphate in oligodendrocyte cell signaling. J Neurochem. 2004b;89:636–644. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2004.02374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trajkovic K, Hsu C, Chiantia S, Rajendran L, Wenzel D, Wieland F, Schwille P, Brugger B, Simons M. Ceramide triggers budding of exosome vesicles into multivesicular endosomes. Science. 2008;319:1244–1247. doi: 10.1126/science.1153124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkataraman K, Futerman AH. Ceramide as a second messenger: sticky solutions to sticky problems. Trends in cell Biol. 2000;10:408–412. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01830-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton KA, Gugiu BG, Thomas M, Basseri RJ, Eliav DR, Salomon RG, Berliner JA. A role for neutral sphingomyelinase activation in the inhibition of LPS action by phospholipid oxidation products. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:1067–1974. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600060-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisner DA, Dawson G. Staurosporine induces programmed cell death in embryonic neurons and activation of the ceramide pathway. J Neurochem. 1996;66:1418–1425. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.66041418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesner DA, Kilkus JP, Gottschalk AR, Quintans J, Dawson G. Anti-immunoglobulin-induced apoptosis in WEHI 231 cells involves the slow formation of ceramide from sphingomyelin and is blocked by bcl-XL. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:9868–9876. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.15.9868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaoka ST, Miyaji M, Kitano Y, Umehara H, Okazaki T. Expression cloning of a human cDNA restoring sphingomyelin synthesis and cell growth in sphingomyelin synthase-defective lymphoid cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:18688–18693. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401205200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu ZF, Nikolova-Karakashian M, Zhou D, Cheng G, Schuchman EH, Mattson MP. Pivotal role for acidic sphingomyelinase in cerebral ischemia-induced ceramide and cytokine production, and neuronal apoptosis. J Molec Neurosci. 2000;15:85–97. doi: 10.1385/JMN:15:2:85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

We propose the following simplified scheme to explain our data. Generation of peroxides (H202) and reactive oxygen species at the cell surface converts PC to OxPC (shown) and smaller fragments HNE and MDA (not shown). We propose that the OxPC has a higher affinity for detergent-resistant microdomains (Raft) since the sn-2 polyunsaturated fatty acid moiety is lost and this results in activation of pro-apoptotic caspase-8, leading to the recruitment of NSMase2 into rafts. NSMase becomes activated and converts SM to ceramide. Many other death domain and activator/accessory proteins are involved in this complex mechanism but are not shown for simplicity. Ceramide homeostasis is maintained largely by the antagonistic balance of NSMase and sphingomyelin synthase (SMS). Since the latter requires PC for activity, so its activity may be compromized by local membrane formation of OxPC. Elevated ceramide results in activation of an Akt-P phosphatase and activation of the pro-apoptotic Bad/Bax complex leading to cytochrome c release from mitochondria (faciliated by ceramide (or possibly the direct action of OxPC on mitochondria (Chen et al., 2007)), caspase-3, activation and c-Jun-N terminal kinase (JNK) cascade activation, leading to cell death.