Abstract

Mice whose γ-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) β3 subunit gene is inactivated (‘β3 knockout mice’) have been previously shown to have epilepsy, hypersensitive behavior, cleft palate, and a high incidence of neonatal mortality. In this study, we analyze whole-cell responses to GABA in neurons from β3+/+, β3+/− and β3−/− mice. We demonstrate markedly decreased responses to GABA in both hippocampal and dorsal root ganglion neurons isolated from β3−/− mice without major differences in the GABA concentration-response curves. We also utilize the subunit selective pharmacology of Zn2+ and the anticonvulsant drug loreclezole to help infer the presence of β2 and γ subunits in the GABAA receptors remaining in neurons from β3−/− mice.

γ-Aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptors mediate most of the rapid inhibitory synaptic transmission in the mammalian brain. GABAA receptors are pentameric complexes consisting of subunits which assemble to form a ligand-gated chloride channel. To date, 16 GABAA subunits have been identified and cloned (α1–6, β1–4, γ1–4, δ, ε) [1,12,14]. GABAA receptors are modulated by clinically important drugs such as the benzodiazepines, general anesthetics, and barbiturates [5,11].

The β3 subunit is a major constituent of neuronal GABAA receptors and is the predominant β subunit isoform mRNA in a number of brain and spinal cord regions [9,10,20]. β3 subunit mRNA is particularly abundant in the prenatal and neonatal brain, which suggests a possible role in development [10]. Recently, mice in which the GABAA β3 subunit gene was inactivated (‘β3 knockout mice’) were demonstrated to have epilepsy, hypersensitive behavior, cleft palate, and a high incidence of neonatal mortality [6]. The phenotype of the β3 knockout mice strengthens the hypothesis that deficits in GABAA receptor-mediated transmission may underlie certain forms of epilepsy [13] and indicates the importance of GABAA receptor function in development and behavior. In the present study, we studied the function of GABAA receptors in the brain and spinal cord of these animals.

The production and phenotypic characterization of β3 knockout mice has been previously described in detail [6]. For the experiments involving cultured hippocampal neurons, the hippocampus was microdissected, and neurons were dissociated from brains of 1-day-old mouse pups by methods described by Jones and Harrison [7], placed onto a layer of confluent mouse cortical astrocytes on a glass cover slip and maintained in tissue culture for 4–5 days prior to recording. For the experiments involving acutely dissociated dorsal root ganglion neurons (DRGs), DRGs were dissociated from postnatal day 1 mouse pups [18], plated onto poly-D-lysine coated coverslips and used for recordings within 12 h.

For all electrophysiological experiments, coverslips containing neurons were transferred to a chamber which was continuously perfused with extracellular medium containing (in mM): 145 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1.5 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 5.5 D-glucose, and 10 HEPES/NaOH (pH 7.4, osmolarity 320–330 mosmol). Recordings were made using the whole-cell patch-clamp technique [6,8]. The intracellular solution contained (in mM): 145 N-methyl-D-glucamine hydrochloride, 5 K2ATP, 5 HEPES/KOH, 2 MgCl2, 0.1 CaCl2, and 1.1 EGTA/KOH (pH 7.2, osmolarity 315 mosmol). Neurons were voltage-clamped at −60 mV. Since the intracellular and extracellular solutions contained approximately equal concentrations of chloride ions, the chloride equilibrium potential was approximately 0 mV.

GABA and other drugs were rapidly applied (>1 ml/min) to neurons by local perfusion using a motor-driven solution exchange device (Bio Logic Rapid Solution Changer RSC-100; Molecular Kinetics, Pullman, WA, USA) as previously described [8]. Responses were low-pass-filtered at 5 kHz and digitized (TL-1–125 interface; Axon Instruments) using pCLAMP5 and stored for off-line analysis. Drugs used in this study were methohexital sodium (Brevital® sodium; Eli Lilly, Indianapolis, IN, USA) and zinc chloride (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). Loreclezole was a kind gift from Janssen Pharmaceutica (Beerse, Belgium).

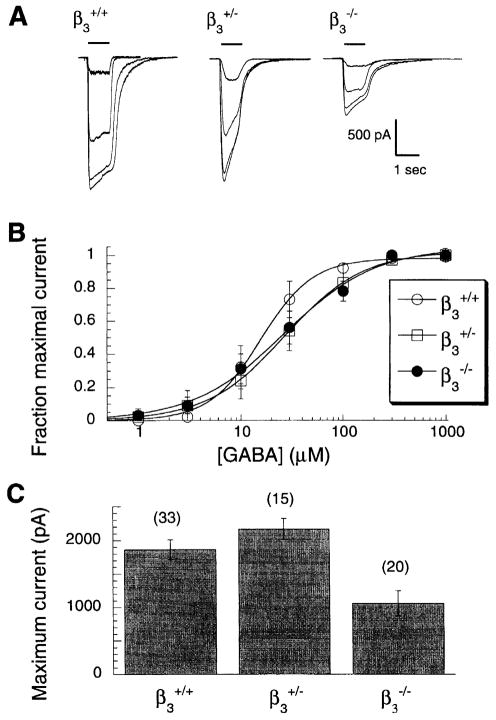

A marked reduction in the maximal amplitude of GABA-evoked whole cell currents was observed in hippocampal neurons from β3−/− mice. Mean maximal GABA responses recorded in hippocampal neurons from β3 mice were nearly 50% lower than those from neurons of either β3+/+ and β3+/− mice (Fig. 1). This is very similar to the reported 50% decrease in the Bmax for [3H]muscimol binding in whole brain homogenates from β3−/− versus β3+/+ mice [6]. This suggests that there are fewer GABAA receptors in neurons from β3−/− mice. The amplitudes of GABA-evoked currents in hippocampal neurons from β3+/+ or β3+/− mice do not differ significantly (Fig. 1C). The GABA concentration-response relationships for neurons from β3+/+, β3+/−, and β3−/− mice are very similar, although the Hill slopes for neurons from β3+/− and β3−/− mice differ significantly from those from β3+/+ mice (P < 0.001 for each of the Hill slopes of β3+/− and β3−/− mice versus β3+/+ mice). Similar small differences in GABA concentration-response relationships have also been noted in recombinant studies of GABAA receptor subunit combinations containing either the β2 or β3 subunit isoform [3].

Fig. 1.

GABA-evoked whole cell currents from cultured hippocampal neurons isolated from newborn β3+/+, β3+/−, and β3−/− mice. (A) Representative currents from individual neurons from each group in response to GABA (10 μM, 30 μM, 100 μM and 1 mM). The bar above the trace represents the duration of GABA application. (B) Pooled GABA concentration-response curves (5 ≤ n ≤ 10) yielding EC50 values of 15.9 ± 0.7 μM, 27.4 ± 0.9 μM, 26.8 ± 3.5 μM for β3+/+, β3+/− and β3−/− mice, respectively. The Hill slopes were 1.7 ± 0.1, 1.1 ± 0.03 and 1.0 ± 0.1. (C) Pooled data for maximal GABA current amplitudes (mean ± SEM) for neurons tested. Numbers above bars indicate number of neurons contributing to mean value. The maximal response to 1 mM GABA for hippocampal neurons from β3−/− mice differs significantly from that for both β3+/+ (P < 0.002) and β3+/− (P < 0.0001) mice (Student’s unpaired t-test). Maximal GABA current amplitudes for hippocampal neurons from β3+/+and β3+/− mice do not differ significantly from each other.

In marked contrast to the situation in hippocampal neurons, where substantial GABA-evoked currents are observed in neurons from β3−/− mice, maximal GABA responses are drastically reduced in DRGs from β3−/− mice [6]. In particular, a majority (>80%) of DRGs from β3−/− mice (27/36 cells) respond to a maximal GABA concentration (1 mM) with less than 100 pA of current.

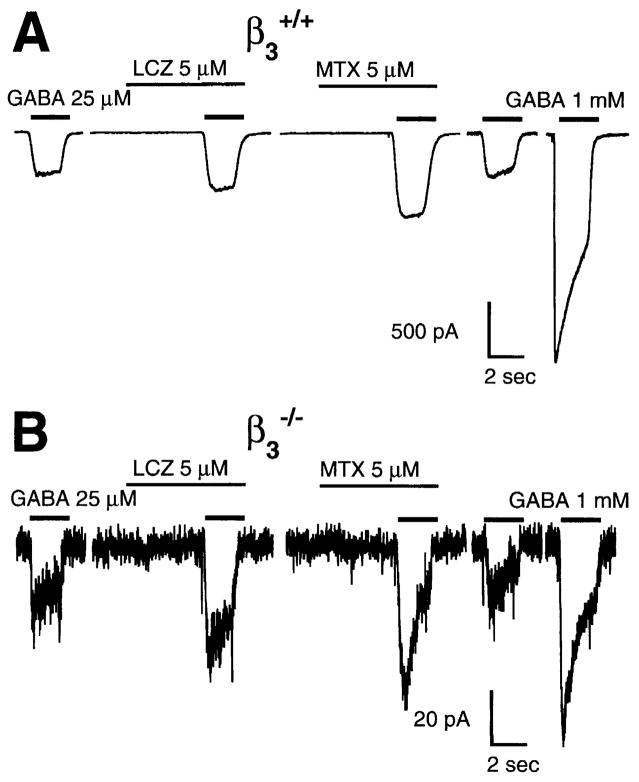

Since in situ hybridization studies have shown that the β3 subunit is the predominant GABAA receptor β subunit isoform mRNA in neonatal rat DRGs [10], GABA currents in DRGs can reveal whether there is any replacement of the lost β3 subunit by another β subunit isoform. A useful pharmacological tool to distinguish between GABAA β subunit isoforms is the anticonvulsant drug loreclezole, which has been demonstrated to have a much higher apparent affinity at GABAA receptors containing β2 or β3 subunits, relative to those containing β1 subunits [17,19]. Only a very small minority of DRG neurons from β3−/− mice have whole-cell GABA currents large enough to perform potentiation experiments (approximately 1 in every 15 cells tested), but in these cells we determined that submaximal (EC20) GABA currents from β3+/+, β3+/− and β3−/− mice were all potentiated equally by a low concentration (5 μM) of loreclezole, consistent with most or all GABAA receptors in DRGs from all three genotypes of mice containing β2 and/or β3 subunits (Fig. 2). Mean data for potentiation by 5 μM loreclezole were: β3+/+(52.3 ± 15.1% potentiation, n = 8), β3+/− (34.1 ± 8.3, n =8), and β3−/− (56.1 ± 27, n = 3). The barbiturate methohexital also potentiated submaximal GABA currents in neurons from all three mouse genotypes (Fig. 2). Mean data for potentiation by 5 μM methohexital were: β3+/+ (82.7 ± 24.7% potentiation, n = 5), β3+/− (100.1 ± 31.5, n = 4), and β3−/− (134.0 ± 22.2, n = 3). We also studied the effect of Zn2+, which has a much higher apparent affinity for GABAA receptors lacking a γ subunit; in particular, currents at GABAA αβ receptors can be inhibited completely by low micromolar concentrations of Zn2+ [2,16]. There was very little inhibition by a low concentration of zinc chloride (10 μM) for GABA currents from DRGs from either β3+/+ (9.7 ± 3.1% inhibition of EC50 GABA current, n = 4) or β3−/− mice (3.4 ± 13.4% inhibition, n = 4).

Fig. 2.

Low concentrations of loreclezole (LCZ) and the barbiturate methohexital (MTX) enhance submaximal GABA currents in DRGs from both β3+/+ and β3−/− mice. Potentiation of approximately EC20 (25 μM) GABA responses by LCZ and MTX at DRGs from both β3+/+ mice (A) and β3−/− mice (B). Note the much lower amplitude of currents in response to the maximal concentration (1 mM) of GABA in the neuron from the β3−/− mouse, which accounts for the noisier appearance of the traces from β3−/− cells.

In the present report, we have extended previous observations observations [6] to show a clear reduction in GABA-evoked currents in hippocampal neurons of β3−/− mice. The approximately 50% reduction in functional GABAA receptors in hippocampal neurons from β3−/− mice is consistent with evidence from in situ hybridization experiments demonstrating substantial expression of β3 mRNA in the CA1 neurons of the hippocampus [9]. The GABA currents in the hippocampal neurons from β3 mice presumably reflect β2 subunit-containing GABAA receptors since β2 mRNA is also detected in appreciable amounts in the hippocampus [9].

Pharmacological experiments in sensory neurons support the idea that there is little or no replacement of the product of the inactivated β3 subunit gene by another β subunit isoform. Potentiation experiments using loreclezole show that the small GABA currents in a minority of DRG cells from β3−/− mice probably result from β2-containing GABAA receptors, which are also likely to be present even in β3+/+ mice, since β2 mRNA is detectable at low levels in neonatal animals [10]. This is consistent with the β1 isoform being predominantly expressed in glial cells [4,15]. In addition, most or all of the GABAA receptors in DRG cells from β3−/− mice still contain the γ subunit (i.e. they are probably αxβ2γ receptors) since there is little or no inhibition of GABA currents by micromolar concentrations of Zn2+.

The β3 knockout mouse appears to be a good model to examine the physiological and behavioral consequences of the lack of a significant fraction of the total GABAA receptor population. The reduced pre- and post-synaptic inhibition resulting from the absence of many functional GABAA receptors may well result in the hypersensitive behavior and epilepsy seen in β3−/− mice and may also contribute to the developmental problems (e.g. cleft palate and early mortality) evident in some of these mice.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Shubha Tole for her help with hippocampal dissections. MDK is supported by National Institute of Mental Health training fellowship MH11504.

References

- 1.Davies PA, Hanna MC, Hales TG, Kirkness EF. Insensitivity to anaesthetic agents conferred by a class of GABAA receptor subunit. Nature (London) 1997;385:820–823. doi: 10.1038/385820a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Draguhn A, Verdorn TA, Ewert M, Seeburg PH, Sakmann B. Functional and molecular distinction between recombinant rat GABAA receptor subtypes by Zn2+ Neuron. 1990;5:781–788. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90337-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ducic I, Caruncho HJ, Zhu WJ, Vicini S, Costa E. γ-Aminobutyric acid gating of Cl− channels in recombinant GABAA receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;272:438–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gu Q, Perez-Velazquez JL, Angelides KJ, Cynader MS. Immunocytochemical study of GABAA receptors in the cat visual cortex. J Comp Neurol. 1993;333:94–108. doi: 10.1002/cne.903330108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harris RA, Mihic SJ, Dildy-Mayfield JE, Machu TK. Actions of anesthetics on ligand-gated ion channels: role of receptor subunit composition. FASEB J. 1995;9:1454–1462. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.14.7589987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Homanics GE, DeLorey TM, Firestone LL, Quinlan JJ, Handforth A, Harrison NL, Krasowski MD, Rick CEM, Korpi ER, Makela R, Brilliant MH, Hagiwara N, Ferguson C, Snyder K, Olsen RW. Mice devoid of γ-aminobutyric type A receptor β3 subunit have epilepsy, cleft palate, and hypersensitive behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:4143–4148. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.4143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones MV, Harrison NL. Effects of volatile anesthetics on the kinetics of inhibitory postsynaptic currents in cultured rat hippocampal neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1993;70:1339–1349. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.4.1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krasowski MD, O’Shea SM, Rick CEM, Whiting PJ, Hadingham KL, Czajkowski C, Harrison NL. α subunit isoform influences GABAA receptor modulation by propofol. Neuropharmacology. 1997;36:941–949. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00074-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laurie DJ, Wisden W, Seeburg PH. The distribution of thirteen GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs in the rat brain. III. Embryonic and postnatal development. J Neurosci. 1992;12:4151–4172. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-11-04151.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma W, Saunders PA, Somogyi R, Poulter MO, Barker JL. Ontogeny of GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs in rat spinal cord and dorsal root ganglia. J Comp Neurol. 1993;338:337–359. doi: 10.1002/cne.903380303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Macdonald RL, Olsen RW. GABAA receptor channels. Ann Rev Neurosci. 1994;17:569–602. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.17.030194.003033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKernan RM, Whiting PJ. Which GABAA -receptor subtypes really occur in the brain? Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:139–143. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)80023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olsen RW, Avoli M. GABA and epileptogenesis. Epilepsia. 1997;38:399–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1997.tb01728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rabow LE, Russek SJ, Farb DH. From ion currents to genomic analysis: recent advances in GABAA receptor research. Synapse. 1995;21:189–274. doi: 10.1002/syn.890210302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosier A, Arckens L, Orban GA, Vandesande F. Immunocytochemical detection of astrocyte GABAA receptors in cat visual cortex. J Histochem Cytochem. 1993;41:685–692. doi: 10.1177/41.5.8385682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smart TG, Moss SJ, Xie X, Huganir RL. GABAA receptors are differentially sensitive to zinc: dependence on subunit composition. Br J Pharmacol. 1991;103:1837–1839. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12337.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wafford KA, Bain CJ, Quirk K, McKernan RM, Wingrove PB, Whiting PJ, Kemp JA. A novel allosteric modulatory site on the GABAA receptor β subunit. Neuron. 1994;12:775–782. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90330-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.White G. Heterogeneity in EC50 and nH of GABAA receptors on dorsal root ganglion neurons freshly isolated from adult rats. Brain Res. 1992;585:56–62. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91190-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wingrove PB, Wafford KA, Bain C, Whiting PJ. The modulatory action of loreclezole at the γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptor is determined by a single amino acid in the β2 and β3 subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4569–4573. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wisden W, Laurie DJ, Monyer H, Seeburg PH. The distribution of 13 GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs in the rat brain. I. Telencephalon, diencephalon, mesencephalon. J Neurosci. 1992;12:1040–1062. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-03-01040.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]