Abstract

Background

Lymphocytic enterocolitis is a malabsorptive syndrome characterized by severe small bowel villous abnormality and crypt hyperplasia and dense infiltrate of lymphocytes throughout the gastrointestinal tract.

Methods

We present two patients with lymphocytic enterocolitis refractory to usual medical therapy who were treated with tumor necrosis factor antagonists.

Results

Both patients had clinical improvement in diarrheal symptoms and intestinal histological abnormalities.

Conclusions

TNF-α antagonists such as infliximab or adalimumab may be a new treatment option for patients with severe refractory lymphocytic enterocolitis not responding to corticosteroids.

Keywords: lymphocytic enterocolitis, diarrhea, refractory sprue, tumor necrosis factor antagonist

Introduction

Microscopic colitis is a recognized cause of chronic watery diarrhea in middle-aged patients with macroscopically normal endoscopic examinations (1). The diagnosis is made by microscopic evaluation of the colorectal mucosa which shows inflammatory cells in the epithelium with histopathologic variations ranging from collagenous to lymphocytic colitis. This process is not always limited to the colon, but can, in the lymphocytic form, present as a “pan-intestinal disease”. Lymphocytic enterocolitis is a “sprue like” syndrome with severe small bowel villous abnormality and crypt hyperplasia and dense infiltrate of lymphocytes throughout the gastrointestinal tract (2). These patients do not respond to gluten withdrawal. Although not previously utilized in microscopic colitis, tumor necrosis factor antagonists can eradicate aberrant clonal populations of lymphocytes, as occurs in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. We discuss two patients with lymphocytic enterocolitis treated with infliximab or adalimumab with the cessation of voluminous diarrhea.

Case 1

A 71 year old white female presented to the Johns Hopkins Hospital with a history of increasing watery diarrhea over two months. Previously, she had one to two formed stools a day. Without history of infections or environmental exposures, she developed non-bloody, watery diarrhea measuring 8–10 liters per day. She had been hospitalized twice with hypokalemia, hypotension, non-anion gap acidosis, and acute renal failure. Stool output fell to 5 liters per day while fasting and on IV fluids. She complained of fatigue, decreased appetite, and abdominal bloating. Her past medical history is notable for hypertension, hypothyroidism, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes. Her daily medications included insulin glargine injections and levothyroxin sodium orally. She did not smoke or use alcohol, and family history was noncontributory.

Upon admission to the Johns Hopkins Hospital, she had recently finished a 10 day course of ciprofloxacin for presumed infectious diarrhea with no improvement. She was afebrile, had postural hypotension, and a tympanitic abdomen with diffuse tenderness and hyperactive bowel sounds. She had 3+ pitting edema of bilateral lower extremities. Laboratory studies revealed anemia (HCT 29), hypoproteinemia, hypoalbuminemia, and hypokalemia. TSH was 100 uIU/mL despite levothyroxin. Stool studies for pathogens were negative and stool collection revealed steatorrhea (fecal fat 9.9g/24hr). An empiric course of Augmentin was given for presumed infectious diarrhea versus bacterial overgrowth with no improvement.

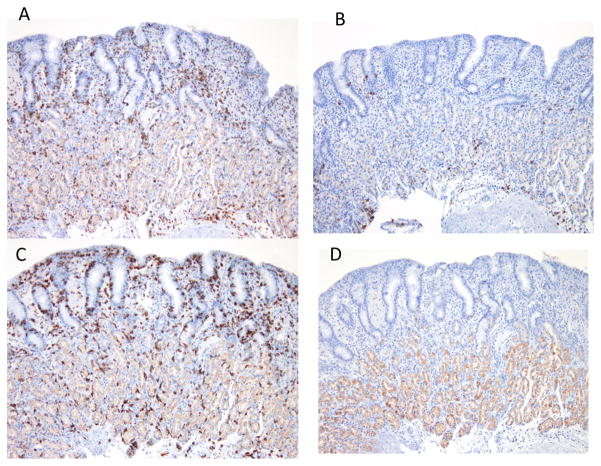

A somatostatin scan was negative for neuroendocrine tumor. Upper GI with small bowel series demonstrated rapid transit, a featureless colon, and significant small bowel thickening. Upper and lower endoscopic studies were macroscopically normal. Gastric biopsies revealed active chronic gastritis with prominent lymphocytic gastritis in the absence of Helicobacter Pylori. Duodenal mucosal biopsies showed prominent chronic inflammatory changes of the lamina propria with architectural distortion and atrophy of the villi (Figure 1A). There was moderate infiltration of intraepithelial lymphocytes and flattening of the villi. Colonoscopy biopsies showed similar findings with prominent lymphocytosis of the lamina propria, intraepithelial lymphocytosis, and widening of the spaces between the crypts due to the inflammatory process (Figure 1C). These findings were consistent with lymphocytic enterocolitis. Additional evaluation (Figure 2) revealed that intraepithelial lymphocytes were T-cell suppressor lymphocytes (immunohistochemical staining positive for CD3 and CD8 and negative for CD20 and CD4 markers) consistent with previous findings in microscopic colitis (3).

Figure 1.

Case 1, Small bowel biopsy: (A) before treatment: Marked villous blunting, intraepithelial lymphocytosis and increased mixed inflammation in the lamina propria. (B) After treatment with tumor necrosis antagonist therapy: Normal appearing villi with mildly increased intra-epithelial lymphocyte infiltration. Colonic biopsy: (C) Before treatment: Marked intra-epithelial lymphocytosis and mixed inflammation in the lamina propria, (D) After treatment: Normal appearing colonic mucosa with mildly increased intraepithelial lymphocyte inflammation.

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemical staining of lymphocytic cellular infiltrate: (A) positive for CD3 (T cell marker); (B) negative for CD20 (B cell marker); (C) positive for CD8 (suppressor cell marker); (D) negative for CD 4 (helper cell marker).

Initially, the patient continued on solumedrol, tincture of opium, antibiotics, and a trial of cholestyramine. Budesonide was also tried, without improvement. Despite six weeks of IV steroids, azathioprine, and TPN, there was no improvement in the patient’s diarrhea. Treatment of her hypothyroidism with IV synthroid and tight glycemic control did not lessen the diarrhea. There were trials of metronidazole, rifaximin, and clonidine with no effect. Finally, she received infliximab at 5mg/Kg dosed at 0, 2, and 6 weeks and remained on infliximab for another 5 months with treatments every 4 weeks. With anti-TNF therapy her bowel movements returned to normal (one or two formed stool per day) over the induction phase of treatment. After treatment with infliximab, follow-up duodenal and colonic biopsies showed improvement (Fig 1B and 1D).

Case 2

A 54y.o. female with history of rheumatoid arthritis presented with chronic diarrhea (8–10 watery bowel movements per day) with a diagnosis of lymphocytic enterocolitis. The patient’s past medical history is notable for mitral valve stenosis with commissurotomy, episodic atrial fibrillation, cervical cancer, and total abdominal hysterectomy. She was started on adalimumab for her rheumatoid arthritis. Medications included etanercept 25mg once a week, prilosec 20mg daily, trazadone 50mg nightly, and omega-3 fatty acids. Laboratory testing to evaluate the diarrhea was unremarkable, and before adalimumab treatment, biopsies of the gastrointestinal tract (stomach, duodenum, and colon) showed surface epithelial injury with increased intraepithelial lymphocyte. She had previously received 2 doses of infliximab with transient improvement of her diarrhea but this was discontinued secondary to allergic reaction (mild and nonspecific rash). Her chronic diarrhea significantly decreased (2–3 semi-formed small bowel movements per day) with initiation of adalimumab. Biopsies after initiation of adalimumab revealed decreasing mucosal inflammation.

Discussion

Lymphocytic enterocolitis is a rare “sprue like” syndrome, in which patients present with malabsorptive symptoms. Histological evaluation of the gastrointestinal mucosa reveals severe villous abnormality and crypt hyperplasia of the small bowel and a dense infiltrate of lymphocytes in the small and large intestine (2). In contrast, the intestinal mucosa is typically normal on macroscopic examination.

The term lymphocytic enterocolitis was coined by DuBois et al. in 1989. These investigators evaluated 135 indexed patients with celiac sprue and 21 with lymphocytic colitis (2). Three of the 21 with lymphocytic colitis and celiac-like changes of the small bowel had no response to gluten-free diet. Consequently, it was concluded that a different entity, now known as lymphocytic enterocolitis, was present characterized by a panintestinal disease, “lymphocytic enterocolitis”, with malabsorption.

Reported complications of lymphocytic enterocolitis include T-cell lymphoma, ulcerative jejunoileitis, and collagenous sprue. In patients with lymphocytic colitis, there is a strong association with other autoimmune disorders such as hypothyroidism, diabetes, psoriasis, and celiac disease. Not surprisingly, our patient in case 1 had hypothyroidism and diabetes.

The term refractory celiac sprue has been used in the literature to designate two populations of patients. Primary refractory sprue patients never respond to a gluten free diet, and secondary refractory sprue patients are those with initial improvement but then failure with a gluten free diet over time (4). Brar et. al. reported that of the 55% of patients with primary refractory sprue, 69% had negative anti-endomysial and tissue transglutaminase antibodies (5). This argues that the label of refractory sprue misclassifies some individuals that have lymphocytic enterocolitis. Correct classification would lead to earlier appropriate management and, in severe cases, avoidance of adverse outcomes.

To date, the main form of therapy reported for lymphocytic enterocolitis has been corticosteroids, based on case reports and expert opinion (1,5,6). Extrapolating from the literature and our own experience, lymphocytic enterocolitis responds to budesonide, and this should be considered the treatment of choice.

In refractory cases of lymphocytic enterocolitis not responding to steroids or other therapies such as azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine (7), there is little guidance concerning additional treatment. However, literature reports do exist of the successful treatment of refractory celiac disease with anti-TNF therapy (8, 9). Because of the histopathological similarity of lymphocytic entercolitis to celiac disease, and that cases of refractory celiac disease may, in fact, be lymphocytic enterocolitis, TNF-α antagonists were empirically tried. Infliximab, a chimeric human-murine immunoglobulin monoclonal antibody to TNF-α, inhibits pro-inflammatory cytokines (10). This agent has been shown to effect fibroblasts, neurtophils, T-cells, and B cells, with decrease in lymphocyte population. Adalimumab, a human monoclonal antibody directed against TNF-α has been used for rheumatoid arthritis and more recently for Crohn’s disease (10). In both of our patients, TNF-α antagonists eliminated the diarrhea with dramatic improvement in small bowel and colonic inflammation. Of note, etanercept, another anti TNF biological agent, failed to ameliorate diarrhea in case 2. This agent appears similarly ineffective in Crohn’s disease, possibly due to poor stability of binding to transmembrane TNF compared to other anti TNF agents (11,12).

In summary, TNF-α antagonists such as infliximab or adalimumab may be a new treatment option for these patients with severe refractory lymphocytic enterocolitis not responding to corticosteroids.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH training grant T32 07632-20

Footnotes

Each author was involved in the conception and design of this report, generation, collection and interpretation of data, the drafting and revision of the manuscript and approval of the final version of the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Schiller LR. Diagnosis and management of microscopic colitis syndrome. J clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:S27–S30. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000123990.55626.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dubois R, Lazenby A, Yardley J, Hendrix T, Bayless T, Giardiello F. Lymphocytic Enterocolitis in patients with refractory sprue. JAMA. 1989;262:935–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mosnier JF, Larvol L, Barge J, Dubois S, De La Bigne G, Henin D, Cerf M. Lymphocytic and collagenous colitis: an immunohistochemical study. Am J Gastroenterology. 1996;91:709–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verkarre V, Asnafi V, Lecomte T, Patey Mariaud-De Serre N, Leborgne M, Grosdidier E, Le Bihan C, Macintyre E, Cellier C, Cerf-Bensussan N, Brousse N. Refractory celiac sprue is a diffuse gastrointestinal disease. Gut. 2003;52:205–211. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.2.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brar P, Lee S, Lewis S, Egbuna I, Bhagat G, Green PH. Budesonide in the treatment of refractory celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterology. 2007;102:2265–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rai RM, Hendrix TR, Moskaluk C, Levine DS, Pasricha PJ. Treatment of idiopathic lymphocytic enterocolitis with oral beclomethasone dipropionate. Am J of Gastroenterology. 1997;92:147–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deslandres C, Moussavou-Kombilia JB, Russo P, Seidman EG. Steroid-resistant lymphocytic enterocolitis and bronchitis responsive to 6-Mercaptopurine in an adolescent. J Pediatri Gastroenterol Nutr. 1997;25:341–346. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199709000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gillett HR, Arnott ID, McIntyre M, Campbell S, Dahele A, Priest M, Jackson R, Ghosh S. Successful infliximab treatment for steroid-refractory celiac disease: a case report. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:800–805. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.31874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turner SM, Moorghen M, Probert CSJ. Refractory celiac diease: remission with infliximab and immunomodulators. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;17:667–9. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200506000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valesini G, Iannuccelli C, Marocchi E, Pascoli L, Scalzi V, Di Franco M. Biological and clinical effects of anti TNFalpha treatment. Autoimmun Rev. 2007;7:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sandborn WJ, Hanauer SM, Katx S, Safdi M, Wold DG, Baert RD, Tremaine WJ, Johnson T, Diehl NN, Zinsmeister AR. Etanercept for active Crohn’s disease: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:1088–94. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.28674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van den Brande JHM, Braat H, van den Brink GR, Versteef HH, Bauer CA, Hoedemaeker Ivan Montfrans C, Hommes DW, Peppelenbosch MP, van Deventer SJ. Infliximab but not etanercept induces apoptosis in lamina propria T-lymphocytes from patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1774–85. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00382-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]