Abstract

Background & Aims

Levator ani syndrome (LAS) might be treated using biofeedback to teach pelvic floor relaxation, electrogalvanic stimulation (EGS), or massage of levator muscles. We performed a prospective, randomized controlled trial to compare the effectiveness of these techniques and assess physiological mechanisms for treatment.

Methods

Inclusion criteria were Rome II symptoms plus weekly pain. Patients were categorized as “highly likely” to have LAS if they reported tenderness with traction on the levator muscles, or as “possible” LAS if they did not. All 157 patients received 9 sessions including psychological counseling plus biofeedback, EGS, or massage. Outcomes were reassessed at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months.

Results

Among patients with “highly likely” LAS, adequate relief was reported by 87% for biofeedback, 45% for EGS, and 22% for massage. Pain days per month decreased from 14.7 at baseline to 3.3 after biofeedback, 8.9 after EGS, and 13.3 after massage. Pain intensity decreased from 6.8 (0–10 scale) at baseline to 1.8 after biofeedback, 4.7 after EGS, and 6.0 after massage. Improvements were maintained for 12 months. Patients with only a “possible” diagnosis of LAS did not benefit from any treatment. Biofeedback and EGS improved LAS by increasing the ability to relax pelvic floor muscles and evacuate a water-filled balloon, and by reducing the urge and pain thresholds.

Conclusions

Biofeedback is the most effective of these treatments, and EGS is somewhat effective. Only patients with tenderness on rectal examination benefit. The pathophysiology of LAS is similar to that of dyssynergic defecation.

Keywords: Proctalgia, Biofeedback, Electrogalvanic stimulation, Dyssynergic defecation

Introduction

Levator ani syndrome (LAS) is defined by chronic or recurring episodes of rectal pain or aching in the absence of structural or systemic disease explanations for these symptoms1. The diagnosis is said to be “highly likely” if the patient reports tenderness on palpation of the levator ani muscles and only “possible” in the absence of tenderness. The Rome III criteria2 use the term “chronic proctalgia” to refer to the same symptoms. This syndrome affects an estimated 6.6% of adults3. The pain may be severe and is associated with increased work absenteeism3. There is no consensus on its pathophysiology, although chronic tension or “spasm” of the striated pelvic floor muscles is the most common view2.

The three most frequently recommended treatments for LAS1, 2 are biofeedback to teach relaxation of the pelvic floor muscles4-8, electrogalvanic stimulation (EGS)6, 9-11, and digital massage of the levator muscles8. Uncontrolled trials support the efficacy of each of these, but reported rates of improvement have been highly variable12, 13. The goals of this randomized controlled trial were (1) to identify which of these treatments yields the greatest clinical benefit and estimate the proportion of patients likely to respond, (2) determine whether clinical benefits are sustained for at least 12 months, (3) determine which physiological measures change with treatment, and (4) identify patient characteristics that predict who is most likely to benefit from these treatments. An additional goal was to compare patients with a highly likely diagnosis to those with a possible diagnosis of LAS.

A physiological assessment which included anorectal manometry and balloon defecation was carried out at baseline and at 1 and 3 months follow-up in order to test the following hypotheses: (1) Patients who achieve adequate relief of LAS will exhibit greater reductions in resting anal canal pressure than patients who do not. (2) Adequate relief of LAS will be associated with the ability to evacuate a 50-ml water-filled balloon.

Methods

Subjects

All patients referred to the Valeggio sul Mincio Section, Division of Gastroenterology of the University of Verona at Verona and Valeggio sul Mincio-Department of Biomedical and Surgical Sciences during a 6-year period (October 2000 to November 2006) with chronic or recurrent rectal pain or aching suggestive of LAS were screened (Figure 1). Inclusion criteria were chronic or recurrent rectal pain or aching for at least 12 weeks in the last year, with pain or discomfort lasting at least 20 minutes1. For this study, subjects were further required to have at least one episode of rectal pain per week during a 4-week run-in. Individuals aged 18-70 who fulfilled all of these symptom criteria and had none of the exclusion criteria (see below) were classified as “highly likely” LAS if they reported tenderness with palpation of the levator ani muscles and as “possible” LAS if they did not report tenderness. The examination for tenderness involved pressing vigorously three times in random order on the posterior, left, and right aspects of the pelvic floor, and was reported as positive only if the patient reported tenderness on two out of three trials in the same location.

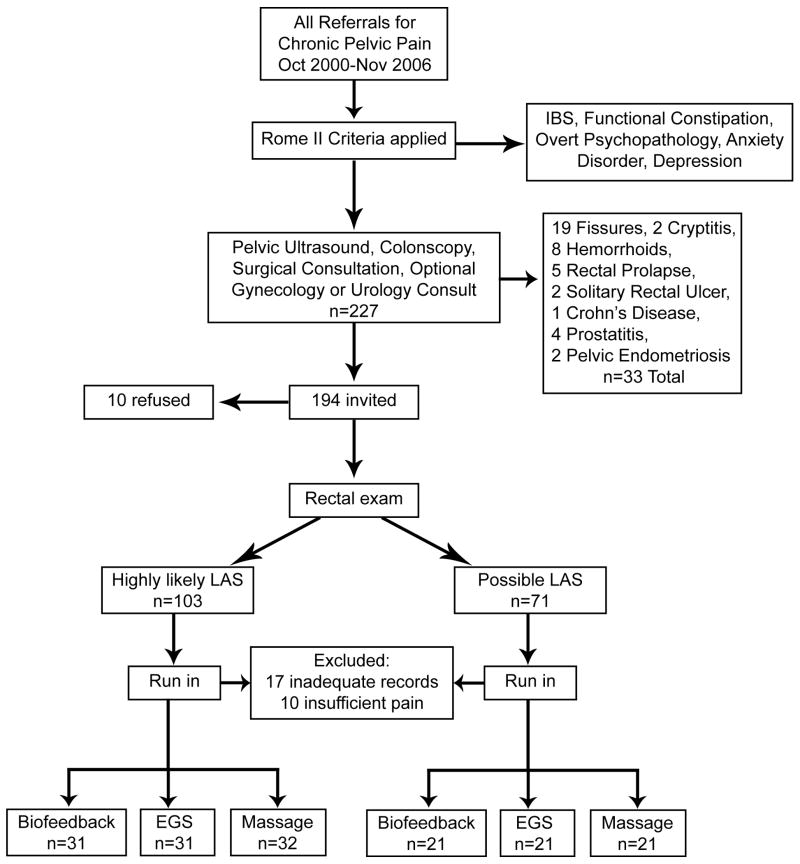

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing the disposition of all subjects considered for the trial.

Exclusion criteria based on Rome II included (1) fulfilling Rome II symptom criteria for irritable bowel syndrome or functional constipation, (2) overt psychopathology or daily use of anxiolytic or antidepressant medications, or (3) pelvic diseases that could produce similar symptoms. The medical examination to exclude pelvic diseases consisted of digital rectal examination by a gastroenterologist, colonoscopy, pelvic ultrasound, and surgical consultation in all patients, plus referral to a gynecologist or urologist when indicated by clinical history or findings. Patients with prior exposure to any of the three treatments were also excluded.

As shown in Figure 1, 227 patients meeting symptom criteria for LAS underwent medical screening for other diseases leading to the exclusion of 33 patients. The remaining 194 patients were given a full description of the study including all elements of informed consent and were invited to participate; however, 10 refused leaving 184 to be screened by a 4-week run-in. At the end of the run-in, an additional 27 patients were excluded (17 for keeping inadequate records and 10 for having less than weekly episodes of rectal pain). The remaining 157 patients were randomized to the three treatment arms. This study was conducted in accord with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki as amended in 1989 (www.fda.gov/oc/health/helsinki89.html) and CONSORT guidelines14. Ethics approval was obtained from the Internal Review Board of the Department of Biomedical and Surgical Sciences of the University of Verona.

Study design

This was a parallel group study with stratified randomization to insure equal ratios of “certain” to “possible” LAS diagnoses in each treatment arm. All patients first underwent a 4-week run-in period to confirm inclusion criteria. The run-in also constituted a baseline assessment for comparison to post-treatment outcomes. Stratified randomization was accomplished by preparing two sets of sealed envelopes containing group assignments ahead of time and shuffling these; at the end of the run-in, eligible subjects were assigned to a treatment group by opening the next envelope from the appropriate set depending on whether the subject had a certain or a possible diagnosis of LAS. The principal investigator (GC) prepared the envelopes containing randomization codes and shuffled these prior to study initiation. The next treatment assignment was not predictable. Treatment involved 9 sessions for all treatment arms. All patients were requested to complete follow-up assessments 1, 3, and 6 months after the end of treatment, and all subjects who reported adequate relief at 6 months follow-up were telephoned at 12 months to ask about adequate relief. The primary outcome was a report of adequate relief. All outcome assessment was carried out by a nurse co-investigator who was blind to treatment assignment. This study is registered in ClinicalTrials.gov as NCT00947180.

Treatment

Biofeedback

The biofeedback treatment was identical to that described for dyssynergic defecation15, 16. This biofeedback protocol was selected because it was known to be effective for reducing pelvic floor muscle tension in a different disorder, pelvic floor dyssynergia15, 16. However, the investigators did not initially assume that the pathophysiology of dyssynergic defecation would be identical to that of LAS. Biofeedback training involved 5 weekly training sessions. Patients were first taught to strain more effectively by holding their breath, lowering their diaphragm, and contracting abdominal wall muscles. Next they were taught to relax pelvic floor muscles during straining using a surface intra-anal EMG probe connected to a portable biofeedback instrument (Myotron-120, Enting Instruments & Systems, Dorst, The Netherlands). The averaged EMG signal was displayed in microvolts. In the final phase of training, patients practiced defecating a 50-ml air-filled balloon while the therapist gently pulled on the plastic tube connected to the balloon. Five 30-minute biofeedback sessions were followed by 4 sessions of counseling to provide contact time with the therapist and counseling that was equivalent to the other two study arms. Counseling involved discussions of the circumstances of pain episodes in order to identify possible triggers for pain and teach strategies to avoid or cope with these trigger situations.

Electrogalvanic stimulation

Nine 30-45 minutes treatment sessions with high-voltage EGS were delivered 3 times/week using a commercially available self-retaining intra-anal probe (Sohn's Electrode, Electro-Med Health Industries, Miami, Florida) connected to an electrogalvanic stimulator (Model 100-2, Electro-Med Health Industries, Miami, Florida). Because no optimal treatment parameters for LAS have been established, we used the stimulation protocol we previously described for dyssynergic defecation17. Pulse frequency was 80 cycles per second. Voltage was gradually increased from 0 to 150-350 volts, depending on the patient's tolerance. Counseling was provided during these sessions using the same techniques described for the biofeedback arm.

Digital massage and sitz baths

Three times each week for a total of 9 clinic visits, the therapist massaged the patient's levator muscles following a previously described protocol8. Digital pressure was applied as strongly as the patient could tolerate, rotating the finger from side to side. The number of times this maneuver was performed in each therapeutic session was 4-6 in the initial session, based on the patient's tolerance, and was increased up to 20 times per session in subsequent sessions. Patients were taught to perform digital massage on themselves and instructed to do this twice a day at home after taking a warm sitz bath. Counseling was also provided following the protocol described above. Sessions lasted 30-45 minutes. Because self-treatment by inserting a finger into the rectum twice a day may be objectionable to some patients, they were questioned about adherence at every follow-up visit. All patients reported massaging their pelvic floor muscles twice a day during the first month, but by 3 months most were practicing massage only once a day, and by 6 months most had discontinued digital massage.

Physiological assessment

Anorectal manometry and balloon expulsion tests were carried out prior to the run-in and at the 1-month and 3-month follow-up points. The purposes of the baseline anorectal manometry test were (1) to confirm that LAS is associated with elevated anal canal pressure and (2) to identify predictors of response to therapy. The purpose of the baseline balloon defecation test was to determine whether the same physiological mechanism is responsible for LAS and dyssynergic defecation. The post-treatment anorectal manometry and balloon expulsion tests served to evaluate the mechanisms responsible for clinical improvement.

Anorectal manometry technique

The manometry catheter (model R6B; Mui Scientific, Missisauga, Ontario, Canada) had a disposable latex balloon on its tip that could be distended with air using a hand-held syringe, and it had 4 perfusion ports spaced 1 cm apart beginning 2 cm below the balloon to measure anal canal pressures. The inner diameter of each of the 4 perfusion catheters was 0.8 mm, and they were perfused with degassed water at a rate of 0.5mL/min using a low compliance pump (Arndorfer Medical Specialties, Greendale, WI). The outer diameter of the catheter was 4.5 mm. Pressures were recorded and displayed using a model GR800 polygraph (Aspen Medical, Dingwall, Scotland). Previously described procedures18 were used to measure (1) anal canal resting pressure (defined as the average of 4 pressure sensors in the region of highest pressure during stationary pull-through), (2) response to straining to defecate (whether a paradoxical increase in anal canal pressure, an incomplete relaxation, or a normal relaxation), (3) lowest (threshold) volume of rectal distention required to elicit a rectoanal inhibitory reflex (RAIR), (4) urge threshold defined as the minimum volume of rectal distention required to elicit a sensation of urgency to defecate, (5) pain tolerance defined as the maximum volume of rectal distention that the patient was able (willing) to tolerate, and (6) compliance of the rectum defined as the pressure in the distending balloon when 100 ml of air was inflated. (The last is an inverse measure of compliance; higher balloon pressures at 100 ml distention reflect decreased compliance.) Manometric tracings were scored manually by one investigator who was blind to the patient's treatment group.

Balloon defecation test

A lubricated Foley catheter was inserted into the rectum and filled with 50 ml of water. The patient was asked to expel this balloon within 5 minutes while sitting on a toilet in a private bathroom, and the test was scored as successful or failed.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was the patient's response at one month follow-up to the question, “Compared to before you started treatment, have you experienced adequate pain relief (Yes or No)”. The adequate relief question was repeated at 3 and 6 months follow-up for all patients, and patients reporting adequate relief at 6 months were asked about adequate relief by telephone at 12 months follow-up. All adequate relief questions were asked by a registered nurse who was unaware of treatment assignment. Patients who did not return for follow-up or who did not respond to the adequate relief question were treated as non-responders in the intent-to-treat analysis at each assessment point.

Multiple secondary end points were used to support the primary outcome:

Subjective pain improvement was evaluated on an ordinal scale at 1, 3, and 6 months follow-up by asking the patient, “Compared to before you started treatment, how would you rate your pain?” Possible answers were: -2 = a lot worse, -1 = a little worse, 0 = same as before, +1 = a little better, +2 = fairly better, and +3 = a lot better or cured.

Number of days per month with rectal pain was inferred from a 30-day symptom log kept during run-in and prior to scheduled follow-up appointments at 1, 3, and 6 months. The therapist was kept blind to diary responses.

Visual analog scale (VAS) ratings of pain (10 cm lines anchored with the words “pain free” at the left end and “worst pain ever experienced” at the right end) were completed weekly during the 30-day symptom diary. Patients were asked to rate the worst pain experienced during the previous week. The average of the 4 weekly VAS ratings was calculated for baseline and each follow-up point.

Self-reported stool frequency was assessed at baseline and at the 6-month follow-up visit by asking the patient how many bowel movements they remembered having in the previous week.

Statistical power and analysis plan

The primary efficacy analysis was a Chi square test of the proportion of subjects reporting adequate relief one month after treatment ended. There were no missing data at one month. For subsequent follow-up points, subjects with missing data on adequate relief were assumed to be non-responders and analysis was by intent-to-treat. Sample size was based on feasibility, i.e., the number of potential subjects available within a 6-year period. However, statistical power was calculated to be approximately 77% to detect a 25% difference between groups in the proportion reporting adequate relief at an unadjusted alpha of 0.025.

After analyzing the pooled sample, we separated the patients into those with a highly likely diagnosis of LAS vs. those with a possible diagnosis and repeated the efficacy analysis for each of these subsets.

Three of the secondary outcome measures (number of pain days per month, average VAS pain rating, and number of stools per week) were continuous, and the other secondary outcome measure was an ordinal scale rating (subjective improvement in pain). These were analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA), and missing values were replaced by the last observation carried forward. These secondary outcomes were analyzed first in all patients with chronic proctalgia and then separately for those with a highly likely and those with a possible diagnosis of LAS. The physiological mediator variables were analyzed by ANOVA (for continuous variables) or Chi square (for dichotomous variables) at each follow-up interval without replacement of missing values. General linear modeling19 for repeated measures was used to assess the impact of treatment on average stool frequency, and logistic regression was used to evaluate patient characteristics that predict who will respond to biofeedback training with adequate relief of pain. For all analyses, p<0.025 was considered significant.

Results

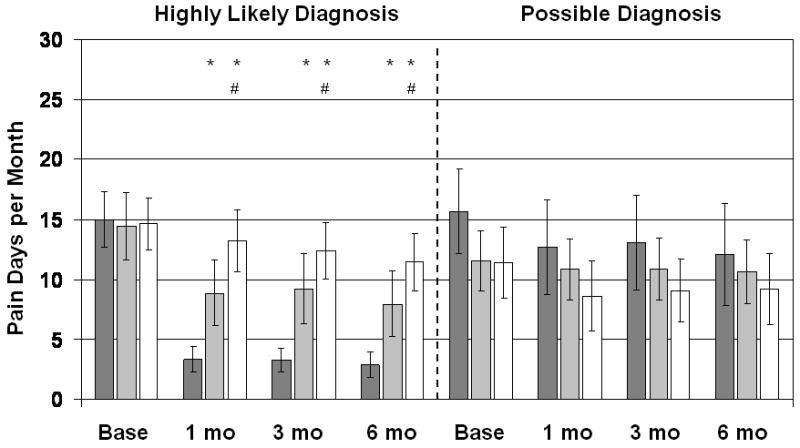

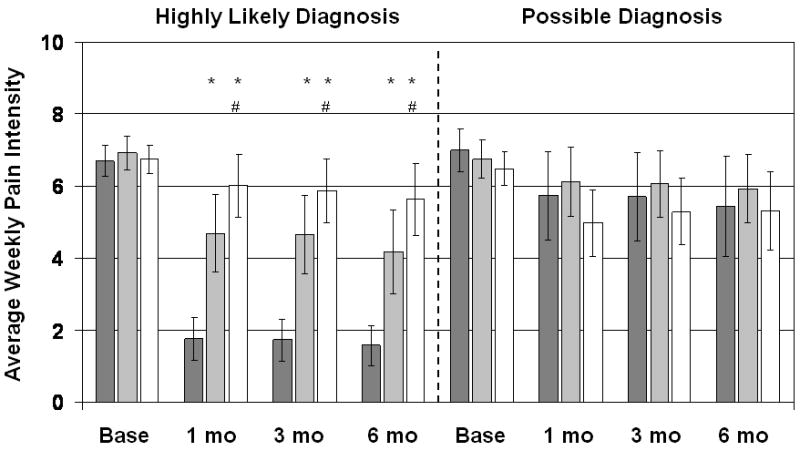

The groups were similar in age, sex, duration of illness, baseline stool frequency, and prior use of medications to manage their chronic proctalgia (Table 1). Most had tried narcotics and antispasmodic medications without significant benefit. Due to stratification, the proportion of subjects with a highly likely diagnosis was similar in all three treatment groups (Figure 1). There were no differences at baseline in the number of days per month with pain or the average intensity of pain (Figures 2-3).

Table 1. Characteristics of Sample.

| Highly Likely LAS Diagnosis | Possible LAS Diagnosis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biofeedback | EGS | Massage | Biofeedback | EGS | Massage | |

| Age (years, Mean±S.D.) | 41.0±10.0 | 42.5±10.4 | 41.7±11.1 | 41.4±10.3 | 42.4±9.4 | 42.2±9.0 |

| Sex (male, %) | 19% | 26% | 34% | 33% | 29% | 25% |

| Symptom duration (mo, Mean±S.D.) | 17.1±4.3 | 16.1±4.3 | 15.9±3.9 | 16.8±4.8 | 16.8±4.8 | 16.8±4.9 |

| Stools per Week (Mean±S.D.) | 6.3+0.8 | 6.6+1.0 | 6.7+0.7 | 6.5+0.8 | 6.5+0.9 | 6.2+0.9 |

| Diazepam use (%) | 58% | 39% | 41% | 76% | 33% | 38% |

| Antispasmodics (%) | 71% | 81% | 69% | 62% | 81% | 52% |

| NSAIDs (%) | 19% | 19% | 19% | 14% | 33% | 38% |

| Narcotics (%) | 77% | 94% | 94% | 81% | 90% | 90% |

Figure 2.

Number of pain days for the previous month. Dark gray bars are Biofeedback-treated patients, light gray bars are EGS-treated patients, and white bars are patients treated with digital massage and sitz baths. Vertical lines show 95% confidence intervals. Patients with a highly likely diagnosis of LAS are shown separately from patients with only a possible diagnosis. *Significantly different from the Biofeedback group at p<0.025; #significantly different from the EGS group at p<0.025.

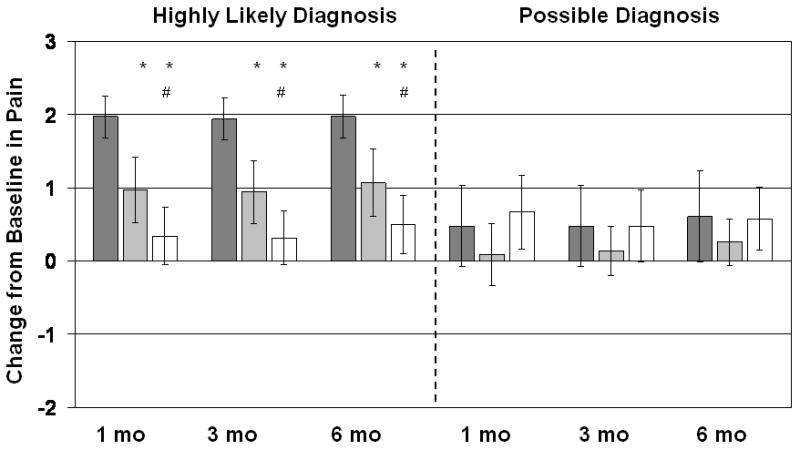

Figure 3.

Average of weekly pain intensity rating for previous month. Pain was rated on a 10cm visual analog scale for the worst rectal pain in the previous week. Dark gray bars are Biofeedback-treated patients, light gray bars are EGS-treated patients, and white bars are patients treated with digital massage and Sitz baths. Vertical lines show 95% confidence intervals. Patients with a highly likely diagnosis of LAS are shown separately from patients with only a possible diagnosis. *Significantly different from the Biofeedback group at p<0.025; #significantly different from the EGS group at p<0.025.

Comparison of treatments

Table 2 shows the intent to treat analysis for the primary outcome measure, adequate relief of pain. Patients with a highly likely diagnosis and those with a possible diagnosis of LAS were pooled. These data show that biofeedback treatment was superior to both EGS and massage at all follow-up points, but EGS and massage were not significantly different from each other.

Table 2. Percent Reporting Adequate Relief (Patients with a highly likely and a possible diagnosis of LAS combined).

| Assessment Interval | Biofeedback % (n) |

EGS % (n) |

Massage % (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Month | 59.6% E,M 31) |

32.7% (17) |

28.3% (15) |

| 3 Months | 57.7% E,M (30) |

38.8% (15) |

20.8% (11) |

| 6 Months | 57.7% E,M (30) |

26.5% (14) |

20.8% (11) |

| 12 Months | 57.7% E,M (30) |

26.5% (14) |

20.8% (11) |

Patients with missing data for any reason were assumed to be non-responders and were retained in the analysis

Biofeedback superior to EGS, p<0.01.

Biofeedback superior to massage, p<0.01.

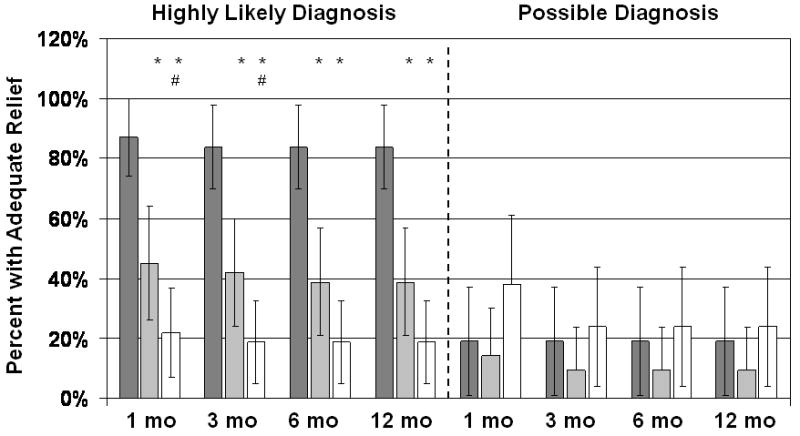

Figure 4 divides the patients into those with a highly likely diagnosis of LAS vs. those with a possible diagnosis and shows the 95% confidence intervals for the responder rate at each time point. Significant improvements in adequate relief occurred exclusively in patients with a highly likely diagnosis of LAS. Moreover, among those with a highly likely diagnosis of LAS, EGS was significantly better than massage at 1 and 3 months but not at 6 or 12 months follow-up.

Figure 4.

Percent reporting adequate relief at follow-up. Dark gray bars are Biofeedback-treated patients, light gray bars are EGS-treated patients, and white bars are patients treated with digital massage and sitz baths. Vertical lines show 95% confidence intervals. Patients with a highly likely diagnosis of LAS are shown separately from patients with only a possible diagnosis. *Significantly different from the Biofeedback group at p<0.025; #significantly different from the EGS group at p<0.025.

Analyses of the secondary outcome variables confirmed the results of the primary analysis: For patients with a highly likely diagnosis of LAS, subjective ratings of improvement in pain (Figure 5) increased significantly more with biofeedback than with EGS or massage, and the EGS group reported significantly more improvement than the massage group at 1, 3, and 6 months follow-up. The number of days per month with pain (Figure 2) decreased significantly more with biofeedback than with massage or EGS at all follow-up points, and EGS was significantly better than massage at all follow-up points. The average VAS rating of pain (Figure 3) likewise decreased significantly more with biofeedback than with EGS or massage, and the EGS group improved significantly more than the massage group. Patients with a possible diagnosis of LAS did not show significant treatment benefits on any of the secondary outcomes.

Figure 5.

Subjective change in pain, rated -2 for “a lot worse”, -1 for “a little worse”, 0 for “same as before”, +1 for “a little better”, +2 for “fairly better”, and +3 for “a lot better or cured”. Dark gray bars are Biofeedback-treated patients, light gray bars are EGS-treated patients, and white bars are patients treated with digital massage and sitz baths. Vertical lines show 95% confidence intervals. Patients with a highly likely diagnosis of LAS are shown separately from patients with only a possible diagnosis. *Significantly different from the Biofeedback group at p<0.025; #significantly different from the EGS group at p<0.025.

Physiological differences between patients with a highly likely diagnosis vs. those with a possible diagnosis of LAS

The principal differences separating those who reported tenderness on palpation of the levator muscles (highly likely diagnosis) from those who did not report tenderness were (1) failure to decrease anal canal pressures when straining and (2) inability to evacuate a 50 ml water-filled balloon: 14% of those with a highly likely diagnosis decreased anal canal pressures when straining compared to 71% of those with only a possible diagnosis, and 13% with a highly likely diagnosis were able to defecate a 50-ml water filled balloon compared to 71% of those with only a possible diagnosis of LAS. On all other physiological variables measured, patients with a highly likely diagnosis of LAS were not different from patients with a possible diagnosis of LAS.

Mechanism of treatment

Table 3 shows changes in physiological measures from baseline to 1 month and 3 months following treatment in each treatment group. In those with a highly likely diagnosis of LAS (left side of Table 3), biofeedback training was associated with restoration of the ability to relax anal canal pressures when straining (94% successful) and ability to defecate a water-filled balloon (97% successful). Patients treated with EGS also showed significant improvements in ability to relax pelvic floor muscles when straining and ability to pass a water-filled balloon, but they were significantly less likely to be successful than patients treated with biofeedback (Table 3, left side). Patients treated with massage did not significantly improve their ability to relax anal canal pressures, but they did show significant improvements in their ability to evacuate water-filled balloons.

Table 3. Physiological Measures.

| Highly Likely Diagnosis of LAS | Possible Diagnosis of LAS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Baseline | 1 Month FU | 3 Month FU | Baseline | 1 Month FU | 3 Month FU | |

| Anal Pressure with Straining (% relaxing) |

Biofeedback | 13% | 94%* | 93%* | 57%D | 81%* | 78%* |

| EGS | 10% | 52%* B | 56%* B | 65% D | 71% | 71% | |

| Massage | 10% | 29% B | 35% B E | 90% D | 90% D | 89% D | |

| Balloon Defecation (% successful) |

Biofeedback | 16% | 97%* | 97%* | 62% D | 86%* | 83%* |

| EGS | 3% | 45%* B | 48%* B | 65% D | 71% | 71% | |

| Massage | 19% | 35%* B | 42%* B | 86% D | 90% D | 89% D | |

| Resting Anal Canal Pressure (mmHg) |

Biofeedback | 69.06±11.45 | 68.94±11.01 | 68.17±11.14 | 67.38±9.52 | 66.38±10.08 | 66.42±9.47 |

| EGS | 68.03±7.32 | 67.52±7.25 | 67.52±7.57 | 68.90±11.23 | 66.90±11.12 | 66.84±10.82 | |

| Massage | 68.91±12.16 | 65.10±9.82* | 64.31±8.83* | 70.90±5.75 | 68.48±6.23 | 68.37±6.75 | |

| RAIR Threshold (ml) |

Biofeedback | 17.10±5.23 | 16.13±5.58 | 15.67±5.04* | 18.10±6.02 | 18.10±8.14 | 15.56±5.11 |

| EGS | 16.77±5.99 | 17.74±5.60 | 17.04±5.42 | 15.24±5.12 | 15.24±5.12 | 15.26±5.13 | |

| Massage | 16.56±6.02 | 16.13±4.95 | 16.54±4.85 | 18.57±6.55 | 18.57±5.73 | 18.95±6.58 | |

| Urge Threshold (ml) |

Biofeedback | 64.52±26.44 | 51.61±8.98* | 51.67±9.13* | 61.90±21.82 | 52.38±10.91 | 52.78±11.79 |

| EGS | 62.90±22.24 | 53.23±12.49* | 53.57±13.11* | 52.38±10.91 | 54.76±10.04 | 55.26±15.17 | |

| Massage | 56.25±16.80 | 54.84±15.03 | 53.85±13.59 | 52.48±10.91 | 52.38±10.91 | 55.00±0.0 | |

| Maximum Tolerable Volume (ml) |

Biofeedback | 250.00±69.52 | 229.03±44.30* | 226.67±44.98* | 247.62±58.04 | 235.71±57.32 | 233.33±48.51 |

| EGS | 258.06±67.20 | 238.71±51.17* | 240.74±53.77* | 240.48±70.03 | 238.10±65.01 | 236.84±54.88 | |

| Massage | 251.56±61.55 | 250.00±56.27 | 246.15±58.18 | 269.05±60.16 | 259.52±53.90 | 257.89±53.39 | |

| Compliance (mmHg) |

Biofeedback | 14.06±3.91 | 14.68±3.74* | 14.57±3.79 | 15.05±3.67 | 15.24±3.52 | 15.11±3.53 |

| EGS | 13.77±3.32 | 13.61±3.20 | 13.22±3.20 | 14.05±3.50 | 14.10±3.39 | 14.37±3.29 | |

| Massage | 14.66±4.28 | 14.52±4.08 | 14.46±3.63 | 14.38±2.97 | 14.29±3.23 | 14.26±3.00 | |

Data shown are means ± standard deviations.

Between times of assessment, different from baseline, p<0.025.

Between treatment conditions, different from biofeedback group, p<0.025.

Between treatment conditions, different from EGS group, p<0.025.

Comparison of highly likely diagnosis to possible diagnosis of LAS, p<0.025.

In patients with only a possible diagnosis of LAS (right side of Table 3), biofeedback was associated with significant increases in the proportion of patients who could relax anal canal pressures when straining and the proportion who could evacuate a 50-ml water filled balloon. However, among those with only a possible diagnosis of LAS, neither EGS nor massage was associated with significant improvement in these parameters.

For patients with a highly likely diagnosis of LAS (left side of Table 3), treatment with biofeedback was also associated with significant decreases in urge threshold and maximum tolerable volume at both 1 and 3 month follow-up assessments, and increased compliance at one month. EGS produced similar changes in urge threshold and maximum tolerable volume, but massage did not. Massage was associated with a significant reduction in resting anal canal pressure, which was not seen in the biofeedback and EGS treatment arms. For patients with only a possible diagnosis of LAS (right side of Table 3), none of these physiological parameters were significantly improved by biofeedback, EGS, or massage.

The data in Table 3 suggest that the mechanism for achieving adequate relief of rectal pain was an improvement from being unable to relax anal canal pressures during straining to being able to do so, and/or an improvement from being unable to evacuate a 50-ml water filled balloon to an ability to do so. In a post hoc test of this hypothesis, we pooled all subjects regardless of treatment group and level of diagnostic confidence and compared those who showed an improvement in either of these parameters to those who showed no change (where no change could mean either inability to relax pelvic floor muscles and/or defecate a balloon at baseline which remained the same after treatment, or no change could mean that the patient was able to relax pelvic floor muscles and/or defecate a balloon at baseline and could also do so after treatment). This analysis showed that 94.2% of those who demonstrated improved pelvic floor dysfunction reported adequate relief whereas only 13.6% of those whose pelvic floor function was unchanged following treatment reported adequate relief (χ2=93.14, p<0.001).

The pathophysiology of LAS revealed by these analyses appears identical to that seen in pelvic floor dyssynergia type constipation1, 15. To explore this similarity, we compared stool frequency at baseline to stool frequency recorded at six month follow-up using General Linear Models for repeated measures19. Average stool frequency at baseline was within the normal range at 6.5 stools per week because the exclusion criteria required that any patient who met criteria for functional constipation be excluded. Nevertheless, 6 months following treatment stool frequency had increased significantly to 7.6 stools per week in patients who reported adequate relief while stool frequency remained unchanged at 6.6 stools per week in patients who did not report adequate relief (F=137.03, p<0.001). Neither type of treatment nor level of diagnostic confidence was significantly related to the magnitude of this increase in stool frequency.

Patient characteristics recorded prior to treatment that predict response to biofeedback

Logistic regression was used to identify baseline variables that could predict adequate relief at one-month follow-up for patients treated with biofeedback. Baseline observations could account for 86.7% of the variance in outcome (Nagelkerke's R2, χ2=53.424, p<0.001), with the best predictors being tenderness on physical examination (p=0.014) and a higher urge threshold (p=0.045). Inability to pass a 50-ml water-filled balloon and failure to relax anal canal pressures when straining were also highly correlated with response to treatment, but they dropped out of the regression analysis due to their high correlation with another predictor variable, pain on physical examination.

Adverse events

No adverse events were reported.

Discussion

This study compared the three most commonly recommended treatments for levator ani syndrome in an adequately-powered, randomized controlled study and demonstrated that biofeedback is significantly more effective than electrogalvanic stimulation or digital massage. When all patients meeting criteria for inclusion were included in the intent-to-treat analysis, 59.6% of biofeedback-treated patients reported adequate relief one month after treatment compared to 32.7% of EGS and 28.3% of massage treated patients. The reductions in rectal pain following biofeedback training were sustained for at least one year. When the analysis was restricted to patients with a highly likely diagnosis of LAS (i.e., those who report tenderness on palpation of the levator muscles), the proportion who reported adequate relief rose to 87.1% at one month follow-up in the biofeedback group.

The superiority of biofeedback was supported by all secondary outcomes: Biofeedback treated patients showed greater reductions in VAS ratings of pain and number of days per month with rectal pain, and they also reported greater improvement in pain on an ordinal scale at all time points. Although EGS and massage appeared to be comparable to each other when evaluated on the adequate relief measure, EGS was superior to massage on most secondary outcome measures, suggesting a possible but weaker benefit for EGS compared to biofeedback.

Previous studies of the treatment of chronic rectal pain were mostly uncontrolled case series or retrospective reports, and success rates for biofeedback6-8, EGS9-11, 13, 20, and massage21, 22 were all highly variable. A single prospective, quasi-randomized study12 compared EGS to local injection of triamcinolone acetonide, but success rates were modest: 25.8% for corticosteroid injection into the levator muscles compared to 9.1% for EGS at 12 months follow-up. Botulinum toxin injection was recently tested in a small randomized controlled trial and failed to show any benefit.23 Sacral nerve stimulation was reported to be beneficial in an uncontrolled study, but when assessed by intent to treat, only 12 of 27 patients reported benefit.24

We investigated the mechanism by which biofeedback and other treatments improve the symptoms of LAS by performing standard anorectal manometry and balloon defecation tests at baseline and at 1 and 3 months follow-up. Our a priori hypothesis was that these treatments would reduce resting anal canal pressures, improve the ability to relax the pelvic floor during straining, and improve the ability to evacuate a water-filled balloon, all of which are indications of decreased pelvic floor muscle tension. There was no significant improvement in anal canal resting pressure except in the group treated with massage. However, we did see significant improvement in the ability to relax pelvic floor muscles and to evacuate a balloon from the rectum in all patients who reported adequate relief of pain regardless of the treatment to which they were exposed. Treatment with biofeedback and EGS were also associated with increases in rectal sensitivity as shown by significant reductions in the urge threshold and the maximum tolerable volume of rectal distention in patients with a highly likely diagnosis. These changes in rectal sensitivity may have been mediated by increases in smooth muscle tone since compliance decreased at one month following biofeedback training. These findings suggest that the mechanism for treatment improvement is the same for these three treatments, although the treatments differ in how effective they are at relieving the symptoms of LAS.

The Rome II (and also the Rome III) diagnostic criteria make a distinction between patients who report tenderness on palpation of the levator muscles versus those who do not by assigning a “highly likely” diagnosis of LAS to the former group. One goal of this study was to evaluate this distinction. At baseline, we found no differences between these groups of patients with respect to pain intensity, number of days per month with pain, anal canal pressures, or rectal sensitivity. However, patients who reported tenderness on digital palpation were less likely to show relaxation of pelvic floor muscles when straining, and most were unable to evacuate a water-filled balloon (simulated defecation). There was also a striking difference in the responsiveness of these patients to all treatments considered: patients who reported tenderness on palpation were significantly more likely to benefit from biofeedback, EGS, and massage. Thus, the distinction based on whether patients report tenderness on digital palpation is an important one, and clinicians may wish to consider this physical sign a requirement for the diagnosis of LAS and for initiation of biofeedback treatment. Future research should address whether there may be a different pathophysiological explanation, or possibly a psychological basis, for rectal pain in patients with only a possible diagnosis of LAS.

These data show that the physiological mechanisms responsible for LAS and dyssynergic defecation are similar. Eight-six percent of patients with a highly likely diagnosis of LAS failed to relax pelvic floor muscles (i.e., to decrease anal canal pressures) when straining to defecate and 87% were unable to evacuate a water-filled balloon. Although the patients with LAS in this study did not have a low stool frequency suggestive of constipation, we found that patients who improved with any of the three treatments investigated (1) demonstrated improved relaxation of anal canal pressures during straining or improved ability to evacuate a water-filled balloon, and (2) showed a significant increase in stool frequency. The fact that stool frequency was within the normal range at baseline may be a consequence of our study entry criteria, which required any patient meeting criteria for functional constipation to be excluded. Moreover, a biofeedback protocol developed to treat dyssynergic defecation was the most effective treatment for LAS and was associated with improved ability to relax pelvic floor muscles when straining, and improved ability to evacuate a balloon. Thus, LAS and dyssynergic defecation appear to represent different symptom manifestations of the same underlying disorder.

These observations also show that pelvic floor dyssynergia (i.e., inability to relax pelvic floor muscles when straining to defecate) may present without symptoms of constipation or obstructed defecation, whereas we had hitherto assumed that pelvic floor dyssynergia would invariably lead to obstructed defecation. This suggest the hypothesis that other factors such as whole gut transit and stool consistency interact with pelvic floor physiology to determine which symptoms develop. Further research is needed to explore this hypothesis.

Study limitations

It was not possible to mask either patients or the therapist to treatment assignment. However, by having all outcome assessments performed by a nurse who was unaware of treatment assignment, we were able to exclude experimenter bias as an explanation for these findings. A second limitation is that there was no placebo group, so we are unable to conclude that the least effective treatment, digital massage, is better than placebo. However, we can conclude that biofeedback is more effective than EGS, which is in turn more effective than massage. A third limitation is that we did not include measures of quality of life to assess the impact of LAS on this outcome, and whether treatment of LAS mitigates this impact.

Clinical application

This study demonstrates that biofeedback is an effective treatment which can be recommended for the treatment of LAS. We have also identified criteria which can be used to select the patients most likely to have a successful outcome, namely those with tenderness on palpation of the levator ani muscles and inability to evacuate a 50-ml water filled balloon. Of equal value to clinicians, our data show that digital massage, a treatment frequently recommended for LAS, is ineffective and should be abandoned. EGS was significantly less effective than biofeedback but may retain a role in the treatment of LAS when biofeedback therapy is not available.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this manuscript was supported by grant R24 DK067674 from the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Diseases

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: No authors have a conflict of interest with respect to this manuscript.

Involvement of each author:

Giuseppe Chiarioni, MD, was responsible for the concept and design of the study, acquisition of the data, and interpretation of the data. He critically reviewed and revised the paper.

Adriani Nardo, MD, contributed to data acquisition and performed a critical review of the manuscript.

Italo Vantini, MD, provided technical and material support and critical review of the manuscript for intellectual content.

Antonella Romito, RN, contributed to data acquisition and critical review of the manuscript.

William E. Whitehead, PhD, was responsible for analysis and interpretation of the data, statistical analysis, drafting of the manuscript, and obtaining funding.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Whitehead WE, Wald A, Diamant NE, Enck P, Pemberton JH, Rao SSC. Functional disorders of the anus and rectum. In: Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Talley NJ, Thompson WG, Whitehead WE, editors. Rome II: The Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. 2. McLean, VA: Degnon Associates; 2000. pp. 483–501. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wald A, Bharucha AE, Enck P, Rao SSC. Functional anorectal disorders. In: Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Delvaux M, Spiller RC, Talley NJ, Thompson WG, Whitehead WE, editors. Rome III: The Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. 3 rd. McLean, Virginia: Degnon Associates; 2006. pp. 639–685. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drossman DA, Li Z, Andruzzi E, Temple RD, Talley NJ, Thompson WG, Whitehead WE, Janssens J, Funch-Jensen P, Corazziari E. U.S. householder survey of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Prevalence, sociodemography, and health impact. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1569–1580. doi: 10.1007/BF01303162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grimaud JC, Bouvier M, Naudy B, Guien C, Salducci J. Manometric and radiologic investigations and biofeedback treatment of chronic idiopathic anal pain. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991;34:690–695. doi: 10.1007/BF02050352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nicosia JF, Abcarian H. Levator syndrome. A treatment that works. Dis Colon Rectum. 1985;28:406–408. doi: 10.1007/BF02560224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ger GC, Wexner SD, Jorge JM, Lee E, Amaranath LA, Heymen S, Nogueras JJ, Jagelman DG. Evaluation and treatment of chronic intractable rectal pain--a frustrating endeavor. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:139–145. doi: 10.1007/BF02051169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilliland R, Heymen JS, Altomare DF, Vickers D, Wexner SD. Biofeedback for intractable rectal pain: outcome and predictors of success. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:190–196. doi: 10.1007/BF02054987. 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heah SM, Ho YH, Tan M, Leong AF. Biofeedback is effective treatment for levator ani syndrome. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:187–189. doi: 10.1007/BF02054986. 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sohn N, Weinstein MA, Robbins RD. The levator syndrome and its treatment with high-voltage electrogalvanic stimulation. Am J Surg. 1982;144:580–582. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(82)90586-4. 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nicosia JF, Abcarian H. Levator syndrome. A treatment that works. Dis Colon Rectum. 1985;28:406–408. doi: 10.1007/BF02560224. 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Billingham RP, Isler JT, Friend WG, Hostetler J. Treatment of levator syndrome using high-voltage electrogalvanic stimulation. Dis Colon Rectum. 1987;30:584–587. doi: 10.1007/BF02554802. 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park DH, Yoon SG, Kim KU, Hwang DY, Kim HS, Lee JK, Kim KY. Comparison study between electrogalvanic stimulation and local injection therapy in levator ani syndrome. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2005;20:272–276. doi: 10.1007/s00384-004-0662-9. 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hull TL, Milsom JW, Church J, Oakley J, Lavery I, Fazio V. Electrogalvanic stimulation for levator syndrome: how effective is it in the long-term? Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:731–733. doi: 10.1007/BF02048360. 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Altman DG, Schulz KF, Moher D, Egger M, Davidoff F, Elbourne D, Gotzsche PC, Lang T. The revised CONSORT statement for reporting randomized trials: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:663–694. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-8-200104170-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiarioni G, Salandini L, Whitehead WE. Biofeedback benefits only patients with outlet dysfunction, not patients with isolated slow transit constipation. Gastroenterol. 2005;129:86–97. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chiarioni G, Whitehead WE, Pezza V, Morelli A, Bassotti G. Biofeedback is superior to laxatives for normal transit constipation due to pelvic floor dyssynergia. Gastroenterol. 2006;130:657–664. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chiarioni G, Chistolini F, Menegotti M, Salandini L, Vantini I, Morelli A, Bassotti G. One-year follow-up study on the effects of electrogalvanic stimulation in chronic idiopathic constipation with pelvic floor dyssynergia. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:346–353. doi: 10.1007/s10350-003-0047-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scarlett YV. Anorectal manometry and biofeedback. In: Drossman DA, Shaheen NJ, Grimm IS, editors. Handbook of Gastroenterologic Procedures. 4th. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005. pp. 341–348. [Google Scholar]

- 19.SPSS I. General Linear Models. 233 South Wacker Drive, 11th Floor, Chicago, Illinois 60606: SPSS Inc.; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oliver GC, Rubin RJ, Salvati EP, Eisenstat TE. Electrogalvanic stimulation in the treatment of levator syndrome. Dis Colon Rectum. 1985;28:662–663. doi: 10.1007/BF02553445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grant SR, Salvati EP, Rubin RJ. Levator syndrome: an analysis of 316 cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1975;18:161–163. doi: 10.1007/BF02587168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thiele G. Coccygodynia: Cause and treatment. Dis Colon Rectum. 1963;6:422–436. doi: 10.1007/BF02633479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rao SS, Paulson J, Mata M, Zimmerman B. Clinical trial: effects of botulinum toxin on Levator ani syndrome--a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:985–991. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.03964.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Falletto E, Masin A, Lolli P, Villani R, Ganio E, Ripetti V, Infantino A, Stazi A, GINS (Italian Group for Sacral Neuromodulation) Is sacral nerve stimulation an effective treatment for chronic idiopathic anal pain? Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:456–462. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e31819d1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]