Abstract

Primitive myeloid leukemic cell lines can be driven to differentiate to monocyte-like cells by 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25(OH)2D3), and, therefore, 1,25(OH)2D3 may be useful in differentiation therapy of myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS). Recent studies have provided important insights into the mechanism of 1,25(OH)2D3-stimulated differentiation. For myeloid progenitors to complete monocytic differentiation a complex network of intracellular signals has to be activated and/or inactivated in a precise temporal and spatial pattern. 1,25(OH)2D3 achieves this change to the ‘signaling landscape’ by: i) direct genomic modulation of the level of expression of key regulators of cell signaling and differentiation pathways, and ii) activation of intracellular signaling pathways. An improved understanding of the mode of action of 1,25(OH)2D3 is facilitating the development of new therapeutic regimens.

Keywords: Vitamin D3, Deltanoids, Leukemia, Differentiation therapy, Cell signaling

1. Introduction

Treatment of human myeloid leukemia cells, including HL60 myeloblastic cells [1-4], U937 monoblastic cells [5], and THP-1 cells [6], with physiological concentrations of 1,25(OH)2D3 induces their differentiation into functional monocytes. For complete functional differentiation to occur the leukemic cells have to be exposed to 1,25(OH)2D3 for between 36-48 hours as during this period ‘differentiating’ adherent CD14-expressing HL60 cells revert to an undifferentiated phenotype if 1,25(OH)2D3 is removed [7-9]. Examination of the behavior of single HL60 myeloid cells exposed to 1,25(OH)2D3 revealed a complex response as to cell behavior - there is an initial burst of proliferation which gives way to growth arrest and terminal differentiation [10,11].

Direct regulation of the transcription of genes encoding proteins that control the cell cycle, prevention of apoptosis and differentiation is important to 1,25(OH)2D3-driven monocytic differentiation. Increased expression and/or activation of several intracellular signaling pathways is also crucial. These include several protein kinase C (PKC) isoforms [12,13], the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-AKT pathway [6,14-16], the p42 extracellular regulated kinase (p42-ERK), p38-ERK and the c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNK) families of mitogen activated protein kinases (MAPKs) [17-22]. Pharmacological or genetic blockade of these pathways abrogates 1,25(OH)2D3-driven monocytic differentiation. Control of these signaling pathways is necessarily complex since they have to be both temporally and spatially integrated so that the correct sequence of regulatory signals are generated in response to 1,25(OH)2D3. Importantly, it is increasingly apparent that pathways are interconnected into networks, with nodal points at which several pathways intersect. While these networks have not been well delineated at this time, some suggested interactive pathways are presented in the Figures 1-3, and an example of a nodal point may be c-Raf 1 [23]. In this review we examine the signaling interplay that is provoked by 1,25(OH)2D3.

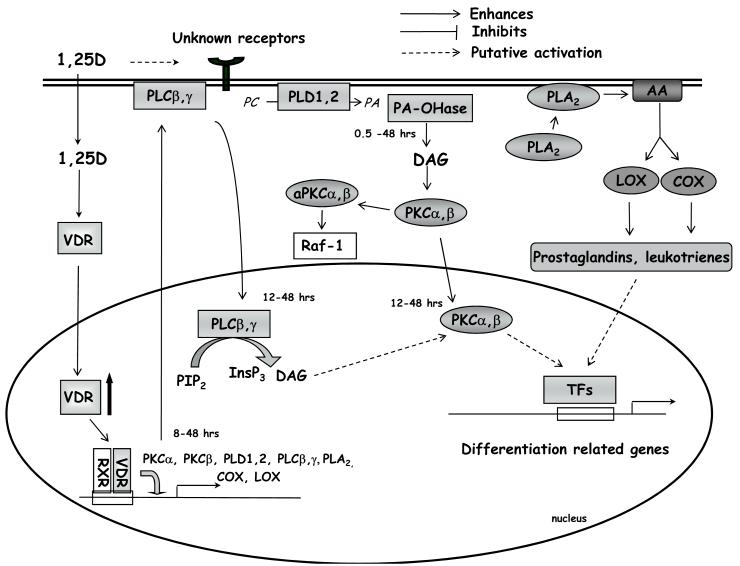

Figure 1. Activities of lipid signalling pathways during 1,25(OH)2D3-driven monocytic differentiation.

1,25(OH)2D3 crosses the cell membrane and binds to VDR in the cytosol. Ligated VDR translocates to the cell nucleus and, as a heterodimer with RXR, activates transcription of 1,25(OH)2D3-regulated genes. In addition, 1,25(OH)2D3, through an unknown mechanism, slowly activates and induces nuclear translocation of PLC isoforms. This leads to production of DAG and InsP3 and to an increase in intracellular Ca2+. Another source of DAG is provided by activated PLD, followed by the action of phosphatidate phosphohydrolase (PA-OH-ase). Increased levels of DAG and Ca2+ cause activation of PKCα and β, which is indispensable for cell differentiation. Activation of PLA2 causes production of prostaglandins and leukotrienes, which, through unknown mechanisms, influence monocytic cell differentiation. For references see text. Signal transduction downstream to Raf-1 will be discussed in next figures.

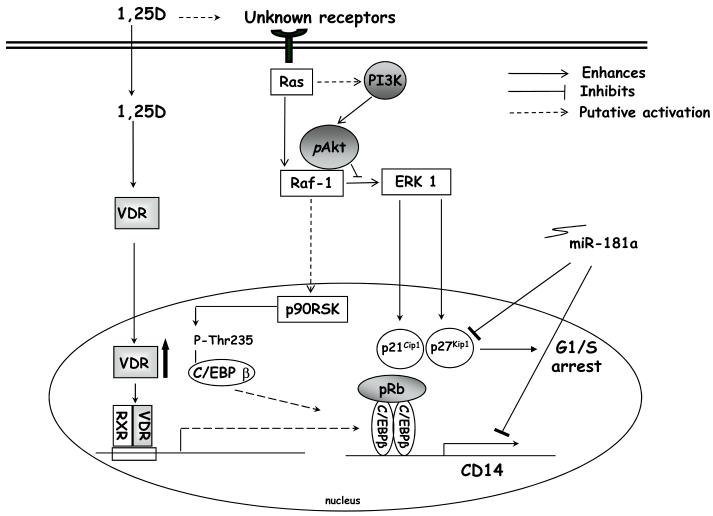

Figure 3. Examples of known signal transducers at late (24-48h) stages of 1,25(OH)2D3-induced monocytic differentiation.

At later stages of 1,25(OH)2D3-induced monocytic differentiation there is increased expression of the transcription factor C/EBPβ. C/EBPβ is then phosphorylated and translocates to the cell nucleus, where it regulates many differentiation-related genes. Activation of the Ras-Raf-ERK1 signal transduction pathway may contribute to increases in the cyclic dependent kinase inhibitors p21CIP-1/waf-1 and p27KIP-1, which causes cell cycle arrest. Activated Akt (pAkt) may inhibit the activation of ERK by binding to Raf. Increases in the cyclic dependent kinase inhibitors appear to be reversed by high levels of either miR-181a.

2. Translocation of vitamin D receptor (VDR) to the nucleus plays a central role in 1,25(OH)2D3-induced monocytic differentiation

Vitamin D receptor (VDR) is a member of the nuclear hormone receptor super family, and 1,25(OH)2D3 acts similarly to the other steroid hormones, such as the thyroid hormone. VDR functions as a ligand-activated transcription factor. Ligated VDR forms a heterodimer with the retinoid X receptor (RXR) which regulates target genes by binding to vitamin D response elements (VDREs) in the promoter regions of genes resulting in either gene activation or repression [24-26]. Similarly, the VDR can directly interact with a number of other proteins which can regulate its activity. For instance, VDR and β-catenin can physically interact so that β-catenin functions are suppressed and VDR transcriptional activities are enhanced [27]. Conversely, the promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger protein (PLZF), which is often over-expressed in acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL), physically interacts with VDR in U937 myeloid cells, neutralizes VDR function, and blocks 1,25(OH)2D3-stimulated monocytic differentiation [28].

CD34+ve progenitor cells from VDR knockout mice failed to differentiate into monocytes when challenged with 1,25(OH)2D3 in vitro [29]. However, the production of monocytes (and other blood cells) appears to be normal in VDR knockout mice suggesting that VDR may not be absolutely essential for monocyte differentiation in vivo [29]. Whether the latter is true in humans is not known. However, myeloid progenitors isolated from patients with type II vitamin D resistant rickets (which contain non-functional mutated VDRs) are refractory to 1,25(OH)2D3-induced differentiation [30]. Similarly, reducing VDR protein levels by antisense oligonucleotides [31] reduces the sensitivity of U937 cells to 1,25(OH)2D3-driven differentiation [Hughes, unpublished observations]. Treatment of THP-1 cells with lipopolysaccharide reduces VDR expression and interferes with 1,25(OH)2D3-driven monocytic differentiation [32]. Conversely, topoisomerase II inhibitors potentiate 1,25(OH)2D3-induced monocytic differentiation of HL60 and U937 cells, and this relates to increased VDR expression [33].

A role for the formation of VDR-RXR heterodimers during differentiation was revealed by the enhancement of 1,25(OH)2D3-induced HL60 monocyte differentiation by RXR agonists, and abrogation by RXR antagonists, but not by RAR antagonists [34]. RXRα is the principal partner for VDR binding and formation of this heterodimer is an absolute requirement for translocation to the nucleus and the activation of gene transcription [35]. Prevention of VDR-RXR hetero-dimerization, and subsequent recruitment of transcriptional co-activators, has been observed to reduce 1,25(OH)2D3-stimulated monocytic differentiation of myeloid cell lines [34,36-38]. Similarly, preventing the association of the VDR/RXR heterodimer with VDREs, by co-expression of DR3-VDRE oligonucleotide decoys, reduced 1,25(OH)2D3-mediated monocytic differentiation of HL60 cells [39].

In unstimulated cells most of the VDR is found in the cytoplasm, and upon 1,25(OH)2D3 stimulation rapidly translocates to the nucleus [40-44]. This requires activation of the mitogen activated kinase (MAPK) and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathways [43]. Additionally, VDR expression increases within a few hours of exposure of myeloid leukemic cells to 1,25(OH)2D3 [32,40-44]. This is due to increased transcription (which is indirect as the VDR gene does not have a VDRE) and, perhaps, a reduction in proteosome-mediated degradation of VDR [43]. It has recently been shown that the cardiotonic steroid bufalin enhances VDR-mediated gene trans-activation, and hence monocytic differentiation, in HL60 cells by prolonging the period that the VDR is retained in the nucleus after 1,25(OH)2D3 stimulation, probably by preventing degradation of the VDR [45,46]. That translocation of the VDR to the nucleus is required for monocytic differentiation is evidenced by the following observations: i) VDR failed to accumulate in the nucleus in 1,25(OH)2D3-resistant HL60 cells [41] and THP-1 sub-lines [40], and ii) in HL60 cells there is a correlation between the potency of side chain-modified vitamin D analogs in inducing differentiation and their ability to drive nuclear localization of VDR [44]. Interestingly, over-expression of the AML-associated gene translocation products PLZF-RARα, PML-RARα and AML-ETO-1 in U937 cells blocked 1,25(OH)2D3-stimulated translocation of the VDR to the nucleus and reduced the responsiveness of cells to 1,25(OH)2D3-stimulated monocytic differentiation [47,48].

3. Activities of lipid signaling pathways are increased during 1,25(OH)2D3-driven monocytic differentiation

3.1 Increased expression and activation of protein kinase C isoforms is important

The PKC family is made up of a number of highly homologous serine/threonine kinases, that differ in their activation requirements and substrate specificities [49]. Members of the family play important regulatory roles in many aspects of hematopoietic cell function including differentiation [50]. An early indication that activation of PKC is important to monocytic differentiation can be taken from the observation that a single dose of the potent but relatively non-specific PKC activator 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate (TPA), which cannot be metabolized, differentiates myeloid progenitor cell lines towards monocytes, whereas multiple doses of 1,2-dioctanylglycerol, a metabolized PKC activator (t½ ~ 8 hours), are needed to achieve differentiation. This relatively crude experiment suggests that a long lasting PKC signal is required for cells to complete the monocytic differentiation program, but does not identify which of the PKC isoforms are involved [51].

Myeloid cells express all three subclasses of PKC isoforms [52], including the classical diacylglycerol (DAG)- and calcium-activated PKC isozymes (α, βI, βII and γ). PKCα and PKCβI/βII are important in different facets of 1,25(OH)2D3-induced monocytic differentiation and in particular, PKCα is important in the maintenance of terminal differentiation [52]. The failure of KG-1a cells to differentiate may relate to a low basal level of PKCβ and a failure to up-regulate expression in response to TPA [53]. Resistance of a HL60 sub-line to TPA-mediated monocytic differentiation appears to be associated with failure of a cytosol-to-membrane translocation of PKC isoforms [54].

PKC activity is increased following 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment of myeloid cell lines. In particular, PKCα and PKCβI/βII activity starts to increase ~ 6-8 hours after exposure to 1,25(OH)2D3 and remains elevated for several days (see figure 1) [51,53,55-58]. The importance of PKC to 1,25(OH)2D3-mediated monocytic differentiation has been revealed by a number of approaches. Pre-treatment of cells with small molecule inhibitors of specific PKC isoforms and antisense oligonucleotides against PKCβI or PKCβII block 1,25(OH)2D3-driven monocytic differentiation [58]. Treatment of myeloid cell lines with sub-differentiating concentrations of 1,25(OH)2D3 for at least 12-24 hours, but for no more than 36-48 hours, ‘primes’ the cells so that they become ‘supersensitive’ to the differentiating actions of TPA. This involves the activation of classical PKC isoforms and tyrosine kinases [59,60]. Similarly, treatment of a HL60 sub-line that is resistant to TPA-mediated monocytic differentiation with a low concentration of 1,25(OH)2D3 for 24 hours restores sensitivity to TPA. This appears to be mediated by an increase in the level of expression of PKCβ (figure 1) [61]. There are many examples of synergy between 1,25(OH)2D3 and PKC-activating phytochemicals in inducing monocytic differentiation. For example, both silibinin or artemisinin synergise with 1,25(OH)2D3 and increase the expression and activities of PKCβ and PKCα. Accordingly, HL-60 cell differentiation induced by silibinin or artemisinin in combination with 1,25(OH)2D3 is blocked by PKC inhibitors [62,63].

3.2. Nuclear translocation and activation of phospholipase C by 1,25(OH)2D3

Increased cellular levels of both DAG and calcium are required for the activation of the classical PKC isoforms [49,50]. Phospholipase C (PLC) hydrolyses phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PtdIns(4,5)P2) to generate DAG and inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate (Ins(1,4,5)P3), a second messenger involved in the release of calcium [49,50]. 1,25(OH)2D3 does not produce a rapid (within minutes of stimulation) Ins(1,4,5)P3-dependent increase in [Ca2+]i in HL60 cells [21,64]. Therefore, any changes in [Ca2+]i seen in myeloid leukemic cell lines must rely on direct activation of store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE). Indeed, in HL60 cells [Ca2+]i rises slowly to 20-30% above basal after 72-96 hours exposure to 1,25(OH)2D3 [21,64]. A similar response is seen following stimulation of freshly isolated human peripheral blood mononuclear (PBM) cells with 1,25(OH)2D3. In PBM the 1,25(OH)2D3-stimulated increase in [Ca2+]i was produced by classical SOCE mechanisms :- an initial depletion of intracellular calcium stores followed by a prolonged period of calcium entry due to activation of a Ca2+ release activated Ca2+ channel (CRAC) [65]. However, neither activation nor pharmacological inhibition of internal calcium stores or calcium influx have a significant effect on 1,25(OH)2D3 provoked monocytic differentiation of HL60 cells [21].

Treatment of HL60 or THP-1 myeloid leukemic cells with exogenous PtdIns-specific PLC is sufficient to induce monocytic differentiation, which is associated with persistent activation of several classical PKC isoforms [66,67]. However, 1,25(OH)2D3 failed to stimulate PLC activity in HL60 cells. Also, inhibitors and activators of PLC activity failed to have any effect on 1,25(OH)2D3-mediated differentiation [21]. Even so, the 1,25(OH)2D3-mediated monocytic differentiation of HL60 cells is associated with an increased nuclear expression of several PLC isoforms. Detection of intranuclear PLCβ2 and PLCγ2 increases progressively from around 48 hours post exposure to 1,25(OH)2D3, and peaks at ~96 hours, while PLCβ3 increases between 48-72 hours, and then decreases until 96 hours post 1,25(OH)2D3 [68,69]. As yet, the importance of these increases is unclear, though it is possible that increased intra-nuclear levels of PtdIns(4,5)P2 can have effects on chromatin structure and RNA processing [70].

3.3. Phospholipase D is activated by 1,25(OH)2D3

DAG can be obtained from the breakdown of membrane phospholipids, such as phosphatidylcholine, by the sequential actions of phospholipase D (PLD) and phosphatidate phosphohydrolase (Figure 1) [71]. PLD activity is increased during monocytic differentiation of U937 cells, induced by dibutyryl cyclic AMP [72], and during GM-CSF/IL-4-stimulated differentiation of monocytes into macrophages [73]. TPA-induced monocytic differentiation of U937 cells is augmented by the PLD activator Se-methylselenocysteine or by over-expression of PLD-1 [74]. 1,25(OH)2D3-stimulated PLD activity has been observed in HL60, U937, THP-1 and NB4 cells [21], and inhibitors of PLD and phosphatidate phosphohydrolase blocked the 1,25(OH)2D3-stimulated differentiation of HL60, U937 and THP-1 cells [21,75,76]. Hence, PLD-mediated generation of DAG, which in turn activates PKC isoforms, appears to be important to 1,25(OH)2D3-driven monocytic differentiation.

3.4. 1,25(OH)2D3-induced stimulation of phospholipase A2 generates a differentiation enhancing signal

The PLA2 super family of enzymes hydrolyses a variety of phospholipids generating a free fatty acid (e.g. arachidonic acid), and lysophospholipid. Myeloid cells contain each of the five main types of PLA2:- the secreted (sPLA2’s), the cytosolic (cPLA2’s), the Ca2+-independent (iPLA2’s), the PAF acetylhydrolases, and the lysosomal PLA2’s. 1,25(OH)2D3 caused PLA2-mediated release of arachidonic acid from HL60 and U937 cells, starting within a few hours and lasting at least 48 hours (figure 1) [77-79]. Addition of exogenous arachidonic acid potentiated 1,25(OH)2D3-mediated monocytic differentiation [79]. In keeping with all of this, inhibition of PLA2 (with dexamethasone) blocked TPA-induced monocytic differentiation of HL60 cells and 1,25(OH)2D3-stimulated monocytic differentiation of U937 cells. Arachidonic acid can be further metabolized in myeloid cells, by either the cycloxygenases (to produce prostaglandins) or lipoxygenase (to produce leukotrienes) pathways. However, to date no prostaglandins or leukotrienes have been identified that either inhibit or potentiate 1,25(OH)2D3-mediated monocytic differentiation.

3.5. Sphingomyelinase is activated by 1,25(OH)2D3

Sphingolipid breakdown products (ceramide, sphingosine and sphingosine-1-phosphate) are a new class of lipids that regulate proliferation, apoptosis and differentiation [80]. A transient rise in ceramide has been observed during TPA- and 1,25(OH)2D3-stimulated monocytic differentiation of HL60 cells [81-83]. Post-1,25(OH)2D3-treatment there is also increased expression and activation of a Mg2+-independent neutral sphingomyelinase in HL60 cells [84] and an acidic sphingomyelinase in THP-1 cells [85]. Furthermore, treatment of HL60 cells with exogenous bacterial sphingomyelinase enhanced the ability of low doses of 1,25(OH)2D3 to induce monocytic differentiation [81]. Synthetic ceramides when added with sub-threshold concentrations of 1,25(OH)2D3 triggered HL60 cells to differentiate to monocytes without further conversion to sphingosine [81], suggesting that ceramide is a mediator of myeloid cell differentiation. Recently, it has been shown that 1,25(OH)2D3-mediated monocytic differentiation is potentiated by several ceramide derivatives, via modulation of the activity of a signaling pathway involving PI3K, PKC, JNK and ERK [86].

Ceramide can be further metabolised to sphingosine (by ceramidase) and sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P, by sphingosine kinase), and activation of sphingosine kinase generates an anti-apoptotic signal during 1,25(OH)2D3-mediated monocytic differentiation. The mechanism by which 1,25(OH)2D3-stimulated S1P production prevents apoptosis in myeloid cells is not understood.

4. The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-Akt-1 signaling pathway plays an important role in 1,25(OH)2D3-stimulated monocytic differentiation

Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases (PI3Ks) generate lipid second messengers that control many aspects of cell function, including growth, differentiation survival, metabolism and motility [87,88]. In mammalian cells eight distinct PI3K isoforms have been described. These are divided into three sub-classes depending on subunit composition and mode of activation [89]. The class I PI3Ks are heterodimers composed of a catalytic subunit (p110α, p110β, p110γ) which physically associates with a regulatory subunit (p85 in the case of p110α, β, and δ or p87/p101 for p110γ). Both p110α and p110β are found in most cells whilst p110δ and p110γ are usually only found in cells of hematopoietic origin [90]. Upon receptor activation, class I PI3Ks synthesize the messenger lipids PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 and PtdIns(3,4)P2 in the plasma membrane where they coordinate the recruitment and activation of pH-domain containing protein effectors (e.g, the serine kinase Akt, sometimes called protein kinase B) [91]. PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 is required for translocation of Akt to the plasma membrane where it is activated by sequential phosphorylation by phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1 (PDK-1) and mammalian target of rapamycin complex 2 (mTORC2) or DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK) [92,93]. Pharmacological or genetic inhibition of several components of the PI3K signaling pathway point to an important role in both the survival and proliferation of hematopoietic progenitors and in myeloid differentiation [94-98]. For example, Akt plays important roles during lineage specification of hematopoietic progenitor cells whereby increasing Akt activity promoted neutrophil and monocyte development, whilst reducing its activity resulted in eosinophil differentiation [98]. Transplantation of CD34+ve cells ectopically expressing constitutively active Akt into NOD/SCID mice resulted in enhanced neutrophil and monocyte development [98].

Inhibitor studies suggest that activation of both PI3K and Akt are crucial to 1,25(OH)2D3-mediated protection against apoptosis and induction of monocytic differentiation [6,14-16,99]. For example, the 1,25(OH)2D3-mediated increase in the expression and activity of steroid sulphatase (a marker of myeloid differentiation) was blocked by pharmacological and genetic inhibition of either PI3K or Akt and involved activation of the transcription factor NF-κB by a PI3K/Akt-dependent mechanism [15]. CD11b and CD14 are two cell surface markers that are commonly used to assess the progress of 1,25(OH)2D3-stimulated monocytic differentiation. However, no recognizable VDREs can be found in the promoter regions of either gene. Binding of several universal transcription factors to their cognate response elements in the promoter region of the CD11b and CD14 genes has been associated with their up-regulation during monocytic differentiation. For example, PU.1, Sp1 and perhaps c-jun have been reported to regulate expression from the CD11b promoter [100,101]. Similarly, Sp1 can activate the CD14 promoter in myeloid cells [102-105]. Although not formally demonstrated at the CD14 promoter in myeloid cells, it has been shown that 1,25(OH)2D3 affects the transcription of several genes following the binding of a VDR-Sp1 complex to an Sp1 response element [106-108] Transcription of the CD14 gene is regulated also by a C/EBPβ transcription factor [103], whose expression is regulated by 1,25(OH)2D3 [19,37]. A 1,25(OH)2D3-stimulated increase in the activity and binding of the myeloid zinc finger-1 (MZF-1) transcription factor to the proximal promoter of CD11b and of CD14 may be essential for expression of CD11b and CD14. Both the DNA binding functions and the transcriptional activity of MZF-1 are dependent on a 1,25(OH)2D3-driven activation of PI3K [109].

5. 1,25(OH)2D3 modulates mitogen activated protein kinase signaling pathways

The mitogen activated kinases (MAPKs) are a family of serine threonine kinases that play important roles in coupling cell surface receptors to changes in transcriptional programs. The MAPKs are grouped into 3 principal families: the extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases (ERKs): the p38 MAPKs and the c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNKs) [110] (see Figures 2 and 3). MAPK signaling involves the creation of a multi-protein signaling complex (a signalosome) and cellular targets include transcription factors that drive differentiation [111,112]. Recent evidence suggests that the MAPK family plays an important role in regulating many aspects of hematopoiesis [113]. As discussed below, 1,25(OH)2D3-mediated monocytic differentiation is associated with increased ERK and JNK activity and is augmented by inhibiting p38 MAPK, but most likely only its α and β isoforms (Zhang J and Studzinski GP, unpublished data). In contrast, all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA)-mediated granulocytic differentiation of HL60 cells is thought to be associated with selective utilisation of ERK MAPKs, but not JNK or p38 MAPKs [114].

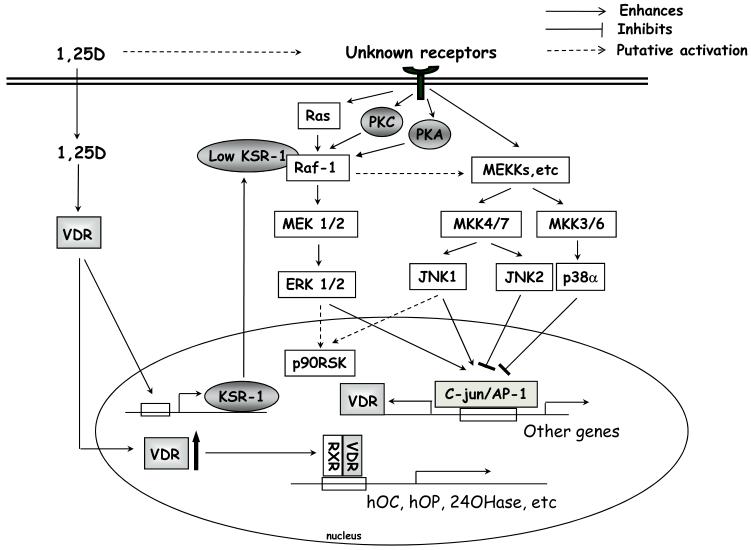

Figure 2. Reported signal transducers at early (0-24h) stages of 1,25(OH)2D3-induced monocytic differentiation.

1,25(OH)2D3, through an unknown mechanism, induces rapid activation of various MAPKs which leads to an increase in AP-1 activity. Ras-Raf-ERK activation is additionally modulated by KSR-1, which is up-regulated by 1,25(OH)2D3. Activation of ERK1/2 and JNK1 positively regulates cell differentiation, while p38 MAPK α/β and JNK2 have a negative influence. There is also a potential negative feedback mechanism between p38 MAPK and ERK MAPK signal transduction pathways, as ERK activities increase when p38 α/β is inhibited.

5.1 Activation of the Ras-Raf-ERKs signaling pathway has multiple roles in 1,25(OH)2D3-stimulated growth arrest and monocytic differentiation

The ERK MAPKs are activated in response to both tyrosine kinase- and G-protein-coupled receptors. Following activation of the small G-protein Ras [110-112], the serine/threonine kinase Raf-1 is recruited to the plasma membrane and activated by multi-site phosphorylation by PKC, protein kinase A and the Src family of tyrosine kinases. In the classical MAPK- ERK pathway, activated Raf-1 phosphorylates mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAP) kinase (MEK-1) which in turn phosphorylates and activates the p42 ERK1 and the closely related p44 ERK2 MAPKs. Active ERK is then released from MEK to dimerize and translocate into the nucleus [110-112,115]. The 1,25(OH)2D3-stimulated p42 ERK MAPK pathway activates the C/EBP family of transcription factors, which play an important role in driving monocytic differentiation [19].

In serum-starved HL60 and NB4 cells, 1,25(OH)2D3-stimulates an increase in p42 ERK activity (as assessed by its phosphorylation status) which starts within minutes and lasts less than an hour (Figure 2) [21,116-118]. This rapid time frame remains to be demonstrated in non-starved cells. Under both conditions, there is a more persistent delayed increase, lasting between 24-48 hours, and then ERK activity gradually fades [21,23]. A kinetically similar increase in Raf-1 activity is observed [23,116]. The initial rise in p42 ERK activation following 1,25(OH)2D3-stimulation of HL60 cells was blocked by pharmacological antagonists of VDR, but not by RXR antagonists [15]. Inhibitors of PKCα, Src tyrosine kinase and Ras-Raf-1 interactions blocked 1,25(OH)2D3-induced activation of the p42 ERK MAPK [21,117,118]. Thus, components of the canonical pathway appear to mediate 1,25(OH)2D3 activation of p42 ERKs. Inhibitor studies suggest that activation of p42 ERK MAPK signaling cascade is essential to 1,25(OH)2D3-stimulated monocytic differentiation of myeloid cells (Figures 2 and 3). However, the specificity of many of the small molecule inhibitors used in the above studies has been questioned, especially when compounds are used at high concentrations [119-122]. Therefore, it seems desirable that the conclusions based on pharmacological inhibition alone be reinforced by the use of more specific genetic or molecular biological approaches.

Raf-1 and its binding partners play roles in 1,25(OH)2D3-stimulated monocytic differentiation. Compounds that prevent the recruitment of Ras and Raf-1 to the plasma membrane, or block the physical association of Ras with Raf-1, block 1,25(OH)2D3-mediated monocytic differentiation [21]. Similarly, transfection of myeloid leukemic cell lines with antisense Raf-1 or short interfering mRNAs (siRNA) against Raf-1 reduced 1,25(OH)2D3-stimulated monocytic differentiation [23,123]. In contrast, sensitivity of myeloid cell lines to 1,25(OH)2D3-induced monocytic differentiation was enhanced by over-expression of Raf-1 [23], by direct small molecule Raf-1 activators [21] or indirect Raf-1 activation [124].

The transcription factor C/EBPβ, and its association with the retinoblastoma protein (Rb), are essential for 1,25(OH)2D3 stimulated monocytic differentiation. Up-regulation of C/EBPβ and retinoblastoma protein (Rb) expression in response to 1,25(OH)2D3 stimulation appears to be mediated by activation of the Raf-1/MEK/ERK MAPK signaling cascade [123]. Genetic knockdown of the Raf-1 prevents the 1,25(OH)2D3-induced up-regulation in C/EBPβ of Rb expression, and abolished C/EBPβ binding to Rb [123].

Raf-1 appears to have an additional signaling role during terminal monocytic differentiation of HL60 cells. This is mediated via Raf-1 activation of p90 ribosomal S6 kinase (p90 RSK), and independent of p42 ERK activation. During the later stages of 1,25(OH)2D3-stimulated HL60 differentiation, p90 RSK is still active when MEK and ERK activation has returned to basal levels [23]. Late p90 RSK activity was not reduced by inhibition of MEK or ERK, but was abrogated by Raf-1 inhibition. Interestingly, p90 RSK plays a role in activating C/EBPβ in many cell systems [125,126], and this could be important to monocytic differentiation.

There also seems to be a novel regulatory link between the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway and the p42 ERK pathway. As described above, 1,25(OH)2D3 stimulates an initial increase in Akt activity lasting for ~48-72 hours which then fall away as the cells enter growth arrest and terminal differentiation. Activated Akt can bind to and inactivate Raf-1 signaling [Figure 3]. Wang et al [123] have reported that over-expression of Akt inhibited p42 MAPK signaling, down-regulated p21CIP-1/waf-1 and p27KIP-1 and blunted differentiation in response to 1,25(OH)2D3, while knockdown of Akt (by RNA interference) gave reverse effects. Therefore, the loss of Akt activity seen prior to 1,25(OH)2D3-induced growth arrest of myeloid cells seems to remove a functional brake on the p42 ERK signaling pathway. Wang et al [123] propose that as Akt activity wanes Raf-1 is released from the inhibitory Akt-Raf-1 complex, leaving it free to activate MEK and p42 ERK. It was also suggested that an indirect activation of p42 ERK is an absolute requirement for the 1,25(OH)2D3-mediated expression of p21CIP-1/waf-1 and p27KIP-1 in myeloid cells, and hence for growth arrest and terminal differentiation [123].

Several scaffolding proteins that modulate Raf-1 function are direct 1,25(OH)2D3 targets in myeloid cells. For example, transcription of the genes encoding the scaffolding protein kinase suppressor of ras-1 (KSR-1) and KSR-2 are directly increased by ligated VDR [127,128]. Both KSR-1 and KSR-2 can associate with and phosphorylate Raf-1 in a stimulus-dependent manner in several model systems, and can act as scaffolds to facilitate the assembly at the cell membrane of Raf-1 protein and its downstream targets [129,130]. However, the scaffold function of KSR-2, though likely on structural grounds, has not been formally demonstrated. Scaffolding protein, such as KSR1 can play an important part in regulating the intensity, duration and specificity of signaling pathways. Importantly, the relative stoichiometry of a scaffold protein and its binding partners are important to signaling, since as the level of expression of the scaffolding protein and Raf-1 approach parity, an optimal differentiation inducing signal is generated [112]. Conversely, an excess of a scaffold protein actually inhibits downstream signaling by titrating the client proteins, binding them individually rather than to the same scaffold molecule at the same time [130-132].

Manipulating KSR-1 and KSR-2 expression can influence the sensitivity of myeloid leukemic cell lines to differentiating stimuli (Figures 2, 3). Anti-sense knockdown of KSR-1 reduced monocytic differentiation induced by low concentrations of 1,25(OH)2D3. At low 1,25(OH)2D3 concentrations, p42 ERK MAPK and p90 RSK activation was also diminished following KSR-1 knockdown [133]. Ectopic expression of a KSR-1 construct amplified the monocytic differentiation-inducing signals at low 1,25(OH)2D3 concentrations [133], while siRNA knockdown of KSR-2 reduced the proportion of highly differentiated monocyte-like cells in HL60 cultures treated with 1,25(OH)2D3 [128]. Knockdown of KSR-2 has also revealed a role in increased cell survival indicating that optimal differentiation to monocytes requires enhanced anti-apoptotic (including Bcl-2/Bax- and Bcl-2/Bad-mediated) events [128].

5.2. Inhibiting p38 MAP kinase signaling potentiates 1,25(OH)2D3-mediated monocytic differentiation

The p38 MAPK family is made up of four members: p38α, p38β, p38γ and p38δ [134,135]. These proteins are encoded by separate genes and are approximately 60% identical at the amino acid level. All four members of the p38 family are thought to be expressed in myeloid cells or their precursors, with p38α being the most abundant and p38β, p38γ and p38δ expressed to a lesser extent [136,137, Studzinski, unpublished observations]. It is thought that each of the p38 isoforms may play important roles in regulating several aspects of myeloid cell proliferation and differentiation although, the exact function of each of the p38 isoforms is still unclear. Multiple stimuli activate the members of the p38 MAPK family by phosphorylation mediated by the following kinase cascade:- the MAPK kinases MKK 3 and MKK6 are the primary upstream activators of p38 MAPK, although MKK4 has also been shown to activate p38 MAPK in some cell types [134,135]. A variety of upstream MAPK Kinase Kinases (MAP3Ks), including Tpl2/cot-1, are known to phosphorylate and activate specific MKKs in different cell types [134,135,138]. p38 MAPK can also be activated by autophosphorylation [134,135].

One study has suggested that lower than normal levels of phosphorylated p38 (an indirect measurement of its activation status) can be observed in hematopoietic progenitors found in bone marrow core biopsy samples from patients with myeloproliferative disorders and this has been suggested to be involved the increased proliferation seen in these cells [139]. In contrast, p38 MAP kinase activity appears to be constitutively activated in myeloid cells from patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) [139,140]. This has been correlated with incomplete differentiation and enhanced apoptosis of MDS hematopoietic progenitors [139,140]. In keeping, pharmacologic inhibitors of p38α/β decrease apoptosis in MDS CD34+ve progenitors and which leads to dose-dependent increases in myeloid colony formation. Similarly, siRNA knockdown of p38 leads to enhancement of hematopoiesis in MDS progenitors grown ex vivo [139-142].

The effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 on p38 MAPK activity in myeloid cells is quite complex. In HL60 cells 1,25(OH)2D3 caused a fairly rapid and long lasting (~ 24 hours) activation of p38 [18], followed by a fairly rapid return to basal level [18]. However, the degree of monocytic differentiation induced by low doses of 1,25(OH)2D3 in myeloid leukemic cells is enhanced by specific inhibition of p38α and β [143-145]. Similarly, treatment of freshly isolated human monocytes with ouabain, which increases p38 activity, was associated with loss of expression of CD14 [146]. Inhibition of p38 MAPK activity was associated with an increase in the activity of the p42 ERK and particularly the JNK MAPK signaling pathways in myeloid cells [143-145] and hepatocytes [147]. Hence, there appears to be either negative cross-talk or a negative feedback loop between the MAPK signaling cascades.

5.3 The role of the c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNKs) family of MAP kinases in 1,25(OH)2D3-driven monocytic differentiation of myeloid cells

Three classes of the c-jun N-terminal kinase family (JNK) of MAP kinases are encoded by jnk1, jnk2, jnk3 genes, and 10 separate JNK isoforms result from alternative splicing of these gene transcripts [148-150]. HL60-40AF cells express both JNK1 and JNK2 [151], whilst in THP-1 myeloid leukemic cells JNK1β1, JNK2α1, and JNK2α2 are found [152]. Recent evidence suggests that JNK1 and JNK2 may have mutually antagonistic roles in the regulation of monocytic differentiation [151].

1,25(OH)2D3 stimulation of myeloid cells is associated with a fairly rapid but persistent increase in JNK phosphorylation and activity [18,153]. Pharmacological inhibition of JNK abrogated 1,25(OH)2D3-mediated monocytic differentiation [153]. Translocation of JNK to the nucleus is essential to 1,25(OH)2D3-mediated monocytic differentiation [151]. Further insight to the importance of JNK to monocytic differentiation came from studies using the HL60-40AF cell line, which is resistant to the differentiating effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 [42,154]. In this cell line, 1,25(OH)2D3 failed to stimulate JNK activity. Resistance of HL60-40AF cells to 1,25(OH)2D3 was reversed by co-treatment with 1,25(OH)2D3, carnosic acid (a plant derived antioxidant), and the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203,580 (DCS cocktail) [42,145,151] which increased total JNK activity [155]. The central role of JNKs was reinforced by the observation that the degree of 1,25(OH)2D3-mediated differentiation and JNK activity in HL60 myeloblastic cells were augmented in parallel following co-stimulation with ceramide derivatives [86].

It is now clear that the interplay between JNK1 and JNK2 is important to resistance of HL60-40AF cells to 1,25(OH)2D3 [151]. In unstimulated HL60-40AF cells the basal level of JNK2 activity was found to be much higher than the basal activity of JNK1. In control HL60 cells the reverse was true and phosphorylated JNK1 (p-JNK) translocated to and accumulated in the nucleus within a few hours of stimulation with 1,25(OH)2D3, while in HL60-40AF cells, expression of p-JNK1 was restricted to the cytosol. Hence, exclusion of p-JNK1 from the nucleus may be restraining differentiation in HL60-40AF cells. Consistent with this notion, in HL60-40AF cells the DCS cocktail partially restored the appearance of phosphorylated p-JNK1 in the nucleus, and of phosphorylated c-Jun (a marker of JNK1 activation). This indicated that an imbalance in nuclear JNK2 and JNK1 signaling restrains monocytic differentiation. When siRNA was used to knock-down JNK1 in HL60-40AF cells, the ability of the DCS cocktail to induce differentiation was reduced and this was associated with reduced activation of the c-Jun/AP-1 transcription factor complex. On the other hand, knock-down of JNK2 amplified the effectiveness of the DCS cocktail as revealed by up-regulation of activated JNK1 and increased activities of the JNK-regulated transcription factors which are essential for monocytic differentiation (e.g c-Jun, ATF2 and Jun B as well as C/EBPβ)[151]. These results show that JNK2 signaling is restraining JNK1’s activity in driving 1,25(OH)2D3-stimulated monocytic differentiation.

6. Role of microRNA in 1,25(OH)2D3-stimulated monocytic differentiation

MicroRNAs are small, noncoding and highly conserved RNA molecules that regulate expression of genes post-transcriptionally by binding to the 3′-UTR regions of the mRNAs [156,157]. Many studies have demonstrated the importance of individual microRNAs to diverse physiological processes, including hematopoietic cell development [158-161]. Several microRNAs are widely expressed in hematopoietic cells, and their altered expression (e.g. by chromosomal translocations) has been correlated with leukemia [162,163].

MicroRNAs are down-regulated, in a dose- and time-dependent manner, during 1,25(OH)2D3-stimulated monocytic differentiation of HL60 and U937 cells (Figure 3) [164]. The microRNAs down-regulated are members of the miR-181 family; the one most markedly down-regulated was miR-181a. In silico studies have revealed miR-181a binding sites in human and mouse p27Kip1 3′-UTRs. In myeloid leukemia cells treated with 1,25(OH)2D3, miR-181a contributes to the control of G1 to S phase transition by modulating expression of the cell cycle regulator p27Kip1. MiR-181a also inhibits 1,25(OH)2D3-induced expression of CD14 and markedly reduces G1 arrest of the cells. In proliferating HL60 cells, there is a high level of expression of miR-181a and the levels of p27Kip1 mRNA and protein are low and insufficient to inhibit Cdk4/6 activity and trigger cell cycle arrest. 1,25(OH)2D3 down-regulates the level of miR-181a, resulting in an increase first in the level of p27Kip1 mRNA, and then protein, leading to G1 block [164]. Similarly, down regulation of miR-181a and a concomitant rise in the level of expression of p27kip1 mRNA prior to G1 arrest has been associated with TPA-induced monocytic differentiation of HL60 cells [165]. It is tempting to speculate that down-regulation of miR-181b during ATRA-induced granulocytic differentiation of APL cells might also relate to cell cycle control [166]. These studies are consistent with the report that levels of expression of miRNA-181a are higher in poorly differentiated AML blasts (M1 and M2 subtypes) than in subtypes M4 and M5, which show partial monocytic differentiation [167]. Together, the above studies [166-167] support the hypothesis that a high constitutive level of expression of miR-181 family members may contribute to the malignant transformation of myeloid cells.

7. Strategies for improving the clinical utility of 1,25(OH)2D3

Animal studies have shown that 1,25(OH)2D3 significantly prolongs the survival of mice transplanted with leukemic cells by promoting cell differentiation [168,169]. However, oral administration of supra-physiological doses of 1,25(OH)2D3 to MDS patients has only produced modest increases in neutrophil and platelet counts in a small minority of patients treated [170-174]. There were no significant increases in patient survival. Moreover, a significant proportion of AMLs are either refractory, or rapidly acquire resistance, to 1,25(OH)2D3-mediated differentiation. The clinical utility of 1,25-(OH)2D3 in these patients has also been compromised by the severe toxicity of therapeutic doses of 1,25(OH)2D3, primarily by potentially fatal drug-induced hypercalcemia [175].

Attempts to resolve the hypercalcemia problem have focused on the generation 1,25(OH)2D3 analogs (‘deltanoids’), with reduced calcemic activity whilst retaining the ability to induce growth arrest and differentiation. Hundreds of such compounds have been developed [176] ; some of them are used in the treatment of psoriasis [177], but their usefulness in treating MDS and AML has yet to be demonstrated. For example, the non-calcemic deltanoid 1α-hydroxyvitamin D3 (1α(OH)D3) was more effective than 1,25(OH)2D3 in in vitro studies [168], but no clear beneficial effect was seen in MDS patients treated with the compound [170,172]. Similarly, 19-Nor-1,25(OH)2D2 (Paricalcitol, Zemplar) is a potent inducer of monocytic differentiation in myeloid leukemic cell lines in vitro [178], but real clinical benefit in MDS patients has not been observed [179]. Other low calcemic analogs which deserve further attention include 1,25-dihydroxy-16-ene-5,6-trans-cholecalciferol (Ro25-4020), which significantly prolonged the survival time of mice inoculated with the myeloid leukemic cell line WEHI 3BD+ at concentrations that did not affect calcium levels [180]. To date, the anti-leukemic effects of this compound have not been evaluated in humans [180]. The Gemini family of non-calcemic vitamin D analogs [181] are also worthy of examination in patients. These compounds are considerable more potent than 1,25(OH)2D3 at driving growth arrest and monocytic differentiation of a variety of myeloid leukemic cell lines in vitro [182]. One of the family members, 1,25-dihydroxy-21(3-hydroxy-3-methyl-butyl)-19-nor-cholecalciferol (19-nor-Gemini; Ro27-5646), has shown some promise in a mouse model of myeloid leukemia at non-toxic doses [183]. However, the effects of the Gemini family of compounds have not been evaluated in human subjects.

An important issue as to the failure of early clinical trials of 1,25(OH)2D3 for treatment of MDS and AML is the heterogeneous nature of these diseases. It has recently become appreciated that a detailed understanding of a patient’s cytogenetic and ‘genomic’ background has contributed to the introduction of more effective ‘patient-specific’ chemotherapeutic regimes [184], therefore it is likely that similar considerations will help identify subgroups of patients who will respond favourably to differentiation therapies from those that will not [184]. A new WHO classification of AML identifies four main groups: AML with recurrent genetic abnormalities, AML with MDS-related changes, therapy-related myeloid neoplasms, and AML not otherwise specified [185]. The first group contains diseases that are different as to genetic background, prognosis and treatment. For example, APL patients with specific chromosomal translocation t(15;17)(q22;q12), which generates the PML-RARα fusion protein, are unresponsive to the differentiating effect of ‘physiological’ doses ATRA but the blockage in differentiation can be overcome by supra-physiological amounts of ATRA, especially if combined with arsenic trioxide. ATRA treatment of APL patients significantly improved clinical outcomes [186,187]. Similarly, 5-10% of paediatric patients with leukaemia have chromosomal translocations involving 11q23 breakage. This is prevalent in patients with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL), acute myelogenous leukaemia (AML) of the M4 and M5 types according to the French-American-British (FAB) classification and mixed lineage leukaemia (MLL), and is usually associated with a poor clinical outcome. A panel of cell lines with translocations involving 11q23 has been established, each of which exhibit a differing sensitivity to ATRA- or 1,25(OH)2D3-induced differentiation [188]. Those cell lines in which expression of the cyclin-dependent kinase 4 and 6 (CDK4 and CDK6) inhibitor p16 is compromised by the presence of 11q23 translocations failed to respond to either ATRA or 1,25(OH)2D3, whereas those cell lines that express p16 responded to both ATRA and 1,25(OH)2D3 [188]. It is, therefore, possible that differentiation therapy using 1,25(OH)2D3 or other deltanoids might be limited to a specific sub-type(s) of AML. In vitro studies are underway to identify whether AML subtypes can be further classified by their sensitivity or resistance to 1,25(OH)2D3-driven differentiation. Therefore, perhaps only those patients who carry favourable mutations or cytogenetic abnormalities should be included in clinical trials of deltanoids.

Differentiation therapy strategies can be devised from our understanding of 1,25(OH)2D3-driven signaling pathways. Toxicity can be avoided by combining relatively low doses of deltanoids which have low calcemia-inducing activity with signal transduction pathway enhancers. For example, 1,25(OH)2D3-induced monocytic differentiation of HL60 cells in vitro may be enhanced by co-treatment with ascorbic acid and vitamin E [189] by a mechanism that is believed to involve pertubations in arachidonic acid metabolism and cyclic AMP generation [79]. Other antioxidants such as carnosic acid, curcumin, ebselen and silibinin are also effective in potentiating monocytic differentiation of cells treated with low concentrations of 1,25(OH)2D3 in vitro [145]. Recently, it was reported that in a mouse model of AML, Balb/c mice inoculated with murine WEHI-3B D leukemia cells, treatment of the mice with a low calcemic deltanoid (19-nor-Gemini) and carnosic acid markedly extended the life span of leukemia-bearing mice [183]. The myelodysplastic disease was reverted to normal and there was no significant liver toxicity or hypercalcemia. Hence, a combination of an antioxidant and a deltanoid may be useful in the treatment of AML. As described above, inhibition of p38 MAPKα/β markedly enhances monocytic differentiation of HL60 cells treated with a low dose of 1,25(OH)2D3. A combination of carnosic acid and an inhibitor of p38MAPKα/β is extremely effective at increasing the sensitivity of HL60 cells to 1,25(OH)2D3-stimulated differentiation in vitro and ex vivo [42,145]. It would be interesting to examine whether a further increase in survival can be obtained in the Balb/c model by adding a p38 inhibitor to the cocktail. Inhibitors of p38 kinase are very promising agents for combination therapy, since several of them are now in pre-clinical and clinical trials to treat inflammatory diseases [190,191]. Such studies will establish doses that are safe to use in the clinic. However, it seems likely that the role of different isoforms of p38MAPK will have to be separately delineated. Thus, signaling of differentiation by 1,25(OH)2D3 remains a fertile field for further pre-clinical investigations.

Acknowledgements

The authors’ experimental work was supported by the NIH grants from the National Cancer Institute RO1 CA 44722 and 5RO1 119242 (GPS), and by Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education grants 2622/P01/2006/31 and 2132/B/P01/2008/34 (EM). We also thank James Imm for comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest.

The authors state that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- [1].Abe E, Miyaura C, Sakagami H, Takeda M, Konno K, Yamazaki T, Yoshiki S, Suda T. Differentiation of mouse myeloid cells induced by 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:4990–4994. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.8.4990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Miyaura C, Abe E, Kurabayshi T, Tanaka H, Konno K, Nishii Y, Suda T. 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 induces differentiation of human myeloid leukaemia cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1981;102:937–942. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(81)91628-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Mangelsdorf D, Koeffler HP, Donaldson C, Pike J, Haussler M. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-induced differentiation in a human promyelocytic leukaemia cell line (HL-60): receptor-mediated maturation to macrophage-like cells. J Cell Biol. 1984;98:391–398. doi: 10.1083/jcb.98.2.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Brown G, Bunce C, Rowlands D, Williams G. All-trans retinoic acid and 1α,25-di-hydroxyvitamin D3 co-operate to promote differentiation of the human promyeloid leukaemia cell line HL60 to monocytes. Leukemia. 1994;8:806–815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Tanaka Y, Shima M, Yamaoka K, Okada S, Seino Y. Synergistic effect of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and retinoic acid in inducing U937 cell differentiation. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 1992;38:415–426. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.38.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hmama Z, Nandan S, Sly L, Knutson K, Herrera-Velit P, Reiner N. 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-induced myeloid cell differentiation is regulated by a vitamin D receptor-phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signalling complex. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1583–1594. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.11.1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Bar-Shavit Z, Kahn AJ, Stone KR, Trial J, Hilliard T, Reitsma PH, Teitelbaum SL. Reversibility of vitamin D-induced leukaemia cell-line maturation. Endocrinology. 1986;118:679–686. doi: 10.1210/endo-118-2-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Studzinski G, Brelvi Z. Changes in proto-oncogene expression associated with reversal of macrophage-like differentiation of HL60 cells. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1987;79:67–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Tomoyasu S, Fukuchi K, Watanabe K, Ueno H, Hamano Y, Hisatake J, Hino K, Gomi K, Tsuruoka N. Reversibility of monocytic differentiation of HL-60 cells by 1α,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3. Leuk Res. 1997;21:217–224. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(96)00112-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Brown G, Choudhry M, Durham J, Drayson M, Michell R. Monocytically differentiating HL60 cells proliferate rapidly before they mature. Exp Cell Res. 1999;253:511–518. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Campbell M, Drayson M, Durham J, Wallington L, Siu-Caldera M, Reddy G, Brown G. Metabolism of and its 20-epi analog integrates clonal expansion, maturation and apoptosis during HL-60 cell differentiation. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1999;149:169–183. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(98)00245-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lee Y, Galoforo S, Berns C, Blackburn R, Huberman E, Corry P. Dual effect of on hsp28 and PKCβ gene expression in phorbol ester-resistant human myeloid HL-525 leukemic cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 1996;52:311–319. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(96)00209-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Shimuzu T, Taira N, Senou M, Takeda K. Involvement of diverse protein kinase C isoforms in the differentiation of ML-1 human myeloblastic leukaemia cells induced by vitamin D3 analogue KH1060 and the phorbol ester TPA. Cancer Lett. 2002;186:67–74. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(02)00235-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Marcinkowska E, Kutner A. Side chain modified vitamin D analogs require activation of both PI 3-K and erk1,2 signal transduction pathways to induce differentiation of human promyelocytic leukaemia cells. Acta Biochim Pol. 2002;49:393–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hughes P, Lee J, Reiner N, Brown G. The vitamin D receptor-mediated activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) plays a role in the 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-stimulated increase in steroid sulphatase activity in myeloid leukaemic cell lines. J Cell Biochem. 2008;103:1551–1572. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Zhang Y, Zhang J, Studzinski G. AKT pathway is activated by 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and participates in its anti-apoptotic effect and cell cycle control in differentiating HL60 cells. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:447–451. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.4.2467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Wang X, Studzinski G. Activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERKs) defines the first phase of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-induced differentiation of HL60 cells. J Cell Biochem. 2001;80:471–482. doi: 10.1002/1097-4644(20010315)80:4<471::aid-jcb1001>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ji Y, Kutner A, Verstuyf A, Verlinden L, Studzinski G. Derivatives of vitamin D2 and D3 activate three MAPK pathways and upregulate pRb expression in differentiating HL60 cells. Cell Cycle. 2002;1:410–415. doi: 10.4161/cc.1.6.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Marcinkowska E, Garay E, Gocek E, Chrobak A, Wang X, Studzinski G. Regulation of C/EBPβ isoforms by MAPK pathways in HL60 cells induced to differentiate by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312:2054–2065. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Studzinski G, Garay E, Patel R, Zhang J, Wang X. Vitamin D receptor signalling of monocytic differention in human leukaemia cells: role of MAPK pathways in transcription factor activation. Curr Top Med Chem. 2006;6:1267–1271. doi: 10.2174/156802606777864935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hughes P, Brown G. 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-mediated stimulation of steroid sulphatase activity in myeloid leukaemic cell lines requires VDRnuc-mediated activation of the RAS/RAF/ERK-MAP kinase signalling pathway. J Cell Biochem. 2006;98:590–617. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Wang Q, Wang X, Studzinski G. Jun N-terminal kinase pathway enhamces signalling of monocytic-differentiation of human leukaemia cells induced by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. J Cell Biochem. 2003;89:1087–1101. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Wang X, Studzinski GP. Raf-1 signaling is required for the later stages of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-induced differentiation of HL60 cells but is not mediated by the MEK/ERK module. J Cell Physiol. 2006;209:253–260. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Rachez C, Freedman L. Mechanism of gene regulation by vitamin D3 receptor: a network of coactivator interactions. Gene. 2000;246:9–21. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Carlberg C, Dunlop TW, Saramäki A, Sinkkonen L, Matilainen M, Väisänen S. Controlling the chromatin organization of vitamin D target genes by multiple vitamin D receptor binding sites. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;103:338–343. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Wang TT, Tavera-Mendoza LE, Laperriere D, Libby E, MacLeod NB, Nagai Y, Bourdeau V, Konstorum A, Lallemant B, Zhang R, Mader S, White JH. Large-scale in silico and microarray-based identification of direct 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 target genes. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:2685–2695. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Shah S, Islam M, Dakshanamurthy S, Rizvi I, Rao M, Herrell R, Zinser G, Valfrance M, Aranda A, Moras D, Norman A, Welsh J, Byers SW. The molecular basis of the vitamin D receptor and β-catenin crossregulation. Mol Cell. 2006;21:799–809. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Ward J, McConnell M, Carlile G, Pandolfi P, Licht J, Freedman L. The acute promyelocytic leukemia-associated protein, promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger, regulates 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-induced monocytic differentiation of U937 cells through a physical interaction with vitamin D3 receptor. Blood. 2001;98:3290–3300. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.12.3290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].O’Kelly J, Histake J, Histake Y, Bishop J, Norman A, Koeffler HP. Normal myelopoiesis but abnormal T lymphocyte responses in vitamin D receptor knockout mice. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:1091–1099. doi: 10.1172/JCI12392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Nagler A, Merchav S, Fabian I, Tatarsky I, Weisman Y, Hochberg Z. Myeloid progenitors from the bone marrow of patients with vitamin D resistant rickets (type II) fail to respond to 1,25(OH)2D3. Br J Haematol. 1987;67:267–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1987.tb02346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Hewison M, Dabrowski M, Vadher S, Faulkner L, Cockerill FJ, Brickell P, O’Riordan J, Katz D. Antisense inhibition of vitamin D receptor expression induces apoptosis in monoblastoid U937 cells. J Immunol. 1996;156:4391–4400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Pramanik R, Asplin J, Lindeman C, Favus M, Bai S, Coe F. Lipopolysaccharide negatively modulates vitamin D action by down-regulating expression of vitamin D-induced VDR in human monocytic THP-1 cells. Cell Immunol. 2004;232:137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Torres R, Calle C, Aller P, Mata F. Etoposide stimulates 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 differentiation activity, hormone binding and hormone receptor expression in HL-60 human promyelocytic cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2000;208:157–162. doi: 10.1023/a:1007089632152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Hughes PJ, Steinmeyer A, Chandraratna RA, Brown G. 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 stimulates steroid sulphatase activity in HL60 and NB4 acute myeloid leukaemia cell lines by different receptor-mediated mechanisms. J Cell Biochem. 2005;94:1175–1189. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Prüfer K, Racz A, Lin GC, Barsony J. Dimerization with retinoid X receptors promotes nuclear localization and subnuclear targeting of vitamin D receptors. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:41114–41123. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003791200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Miura D, Manabe K, Gao Q, Norman AW, Ishizuka S. 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-26,23-lactone analogs antagonize differentiation of human leukemia cells (HL-60 cells) but not of human acute promyelocytic leukemia cells (NB4 cells) FEBS Lett. 1999;460:297–230. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01347-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Ji Y, Studzinski GP. Retinoblastoma protein and CCAAT/enhancer binding protein β are required for 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-induced monocytic differentiation of HL60 cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:370–377. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Ishizuka S, Kurihara N, Hiruma Y, Miura D, Namekawa J, Tamura A, Kato-Nakamura Y, Nakano Y, Takenouchi K, Hashimoto Y, Nagasawa K, Roodman GD. 1α,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3-26,23-lactam analogues function as vitamin D receptor antagonists in human and rodent cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;110:269–277. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Ji Y, Wang X, Donnelly RJ, Uskokovic MR, Studzinski GP. Signaling of monocytic differentiation by a non-hypercalcemic analog of vitamin D3, 1,25(OH)2-5,6 trans-16-ene-vitamin D3, involves nuclear vitamin D receptor (nVDR) and non-nVDR-mediated pathways. J Cell Physiol. 2002;191:198–207. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Humeniuk-Polaczek R, Marcinkowska E. Impaired nuclear localization of vitamin D receptor in leukemia cells resistant to calcitriol-induced differentiation. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;88:361–366. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Wu-Wong J, Nakane M, Ma J, Dixon D, Gagne G. Vitamin D receptor (VDR) localization in human promyelocytic leukemia cells. Leuk Lymphoma. 2006;47:727–732. doi: 10.1080/10428190500398898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Garay E, Donnelly R, Wang X, Studzinski GP. Resistance to 1,25D3-induced differentiation in human acute myeloid leukemia HL60-40AF cells is associated with reduced transcriptional activity and nuclear localization of the vitamin D receptor. J Cell Physiol. 2007;213:816–825. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Gocek E, Kiełbiński M, Marcinkowska E. Activation of intracellular signaling pathways is necessary for an increase in VDR expression and its nuclear translocation. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:1751–1757. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.03.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Gocek E, Kiełbiński M, Wyłób P, Kutner A, Marcinkowska E. Side-chain modified vitamin D analogs induce rapid accumulation of VDR in the cell nuclei proportionately to their differentiation-inducing potential. Steroids. 2008;73:1359–1366. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2008.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Nakano H, Matsunawa M, Yasui A, Adachi R, Kawana K, Shimomura I, Makishima M. Enhancement of ligand dependent vitamin D receptor transactivation of the cardiotonic steroid bufalin. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;70:1479–1486. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Amano Y, Cho Y, Matsunawa M, Komiyama K, Makishima M. Increased nuclear expression and transactivation of vitamin D receptor by the cardiotonic steroid bufalin in human myeloid leukemia cells. J Ster Biochem Mol Biol. 2009;114:144–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2009.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Puccetti E, Obradovic D, Beissert T, Bianchini A, Washburn B, Chiaradonna F, Boehrer S, Hoelzer D, Ottmann OG, Pelicci PG, Nervi C, Ruthardt M. AML-associated translocation products block vitamin D3-induced differentiation by sequestering the vitamin D3 receptor. Cancer Res. 2002;62:7050–7058. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Racanicchi S, Maccherani C, Liberatore C, Billi M, Gelmetti V, Panigada M, Rizzo G, Nervi C, Grignani F. Targeting fusion protein/corepressor contact restores differentiation response in leukemia cells. EMBO J. 2005;24:1232–1242. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Mellor M, Parker PJ. The extended protein kinase C superfamily. Biochem J. 1998;332:281–292. doi: 10.1042/bj3320281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Tan SI, Parker PJ. Emerging and diverse roles of protein kinase C in immune cell signalling. Biochem J. 2003;376:545–552. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Aihara H, Asaoka Y, Yoshida K, Nishizuka Y. Sustained activation of protein kinase C is essential to HL-60 cell differentiation to macrophage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:11062–11066. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Seibenhener ML, Wooten MW. Heterogeneity of protein kinase C isoform expression in chemically induced HL60 cells. Exp Cell Res. 1993;207:183–188. doi: 10.1006/excr.1993.1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Hooper WC, Abraham RT, Ashendel CL, Woloschak GE. Differential responsiveness to phorbol esters correlates with differential expression of protein kinase C in KG-1 and KG-1a human myeloid leukemia cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989;1013:47–54. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(89)90126-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Slapak CA, Kharbanda S, Saleem A, Kufe DW. Defective translocation of protein kinase C in multidrug-resistant HL-60 cells confers a reversible loss of phorbol ester-induced monocytic differentiation. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:12267–12273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Obeid LM, Okazaki T, Karolak LA, Hannun YA. Transcriptional regulation of protein kinase C by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in HL-60 cells. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:2370–2374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Solomon DH, O’Driscoll K, Sosne G, Weinstein IB, Cayre YE. 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-induced regulation of protein kinase C gene expression during HL-60 cell differentiation. Cell Growth Differ. 1991;2:187–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Pan Q, Granger J, O’Connell TD, Somerman MJ, Simpson RU. Promotion of HL-60 cell differentiation by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 regulation of protein kinase C levels and activity. Biochem Pharmacol. 1997;54:909–915. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(97)00286-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Simpson RU, O’Connell TD, Pan Q, Newhouse J, Somerman MJ. Antisense oligonucleotides targeted against protein kinase Cβ and CβII block 1,25-(OH)2D3-induced differentiation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:19587–19591. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.31.19587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Bhatia M, Kirkland JB, Meckling-Gill KA. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 primes acute promyelocytic cells for TPA-induced monocytic differentiation through both PKC and tyrosine phosphorylation cascades. Exp Cell Res. 1996;222:61–69. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Berry DM, Antochi R, Bhatia M, Meckling-Gill KA. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 stimulates expression and translocation of protein kinase Cα and Cδ via a nongenomic mechanism and rapidly induces phosphorylation of a 33-kDa protein in acute promyelocytic NB4 cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:16090–16096. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.27.16090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Macfarlane DE, Manzel L. Activation of β-isozyme of protein kinase C (PKC β) is necessary and sufficient for phorbol ester-induced differentiation of HL-60 promyelocytes. Studies with PKC β-defective PET mutant. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:4327–4331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Kang SN, Lee MH, Kim KM, Cho D, Kim TS. Induction of human promyelocytic leukemia HL-60 cell differentiation into monocytes by silibinin: involvement of protein kinase C. Biochem Pharmacol. 2001;61:1487–1495. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00626-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Kim S, Kim H, Kim TS. Differential involvement of protein kinase C in human promyelocytic leukaemia cell differentiation enhanced by artemisinin. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;482:67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.09.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Gardner JP, Balasubramanyam M, Studzinski GP. Up-regulation of Ca2+ influx mediated by store-operated channels in HL60 cells induced to differentiate by 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. J Cell Physiol. 1997;172:284–295. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199709)172:3<284::AID-JCP2>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Lajdova I, Chorvat D, Jr, Chorvatova A. Rapid effects of 1,25(OH)2D3 resting human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;586:14–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Stone RM, Weber BL, Spriggs DR, Kufe DW. Phospholipase C activates protein kinase C and induces monocytic differentiation of HL-60 cells. Blood. 1988;72:739–744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Barendsen N, Chen B. Phospholipase C-induced monocytic differentiation in a human monocytic leukemia cell line THP-1. Leuk Lymphoma. 1992;7:323–329. doi: 10.3109/10428199209049785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Bertagnolo V, Marchisio M, Capitani S, Neri LM. Intranuclear translocation of phospholipase Cβ2 during HL-60 myeloid differentiation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;235:831–837. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Neri LM, Bortul R, Borgatti P, Tabellini G, Baldini G, Capitani S, Martelli AM. Proliferating or differentiating stimuli act on different lipid-dependent signaling pathways in nuclei of human leukemia cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:947–964. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-02-0086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Cocco L, Faenza I, Follo MY, Ramazzotti G, Gaboardi GC, Billi AM, Martelli AM, Manzoli L. Inositide signaling: Nuclear targets and involvement in myelodysplastic syndromes. Adv Enzyme Regul. 2008;48:2–9. doi: 10.1016/j.advenzreg.2007.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].McDermot M, Wakelam MJ, Morris AJ. Phospholipase D. Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;82:225–253. doi: 10.1139/o03-079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Burke JR, Davern LB, Gregor KR, Owczarczak LM. Differentiation of U937 cells enables a phospholipase D-dependent pathway of cytosolic phospholipase A2 activation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;260:232–239. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Kang HK, Lee HY, Lee YN, Jo EJ, Kim JI, Kim GY, Park YM, Min DS, Yano A, Kwak JY, Bae YS. Up-regulation of phospholipase Cγ1 and phospholipase D during the differentiation of human monocytes to dendritic cells. Int Immunopharmacol. 2004;4:911–920. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Lee T, Kim Y, Min do S, Park J, Kwon T. Se-methylselenocysteine enhances PMA-mediated CD11c expression via phospholipase D1 activation in U937 cells. Immunobiology. 2006;211:369–376. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].El Marjou M, Montalescot V, Buzyn A, Geny B. Modifications in phospholipase D activity and isoform expression occur upon maturation and differentiation in vivo and in vitro in human myeloid cells. Leukemia. 2000;14:2118–2127. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Di Fulvio M, Gomez-Cambronero J. Phospholipase D (PLD) gene expression in human neutrophils and HL-60 differentiation. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;77:999–1007. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1104684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Honda A, Morita I, Murota S, Mori Y. Appearance of the arachidonic acid metabolic pathway in human promyelocytic leukemia (HL-60) cells during monocytic differentiation: enhancement of thromboxane synthesis by 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;877:423–432. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(86)90208-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Honda A, Raz A, Needleman P. Induction of cyclo-oxygenase synthesis in human promyelocytic leukaemia (HL-60) cells during monocytic or granulocytic differentiation. Biochem J. 1990;272:259–262. doi: 10.1042/bj2720259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].López-Lluch G, Fernández-Ayala DJ, Alcaín FJ, Burón M, Quesada J, Navas P. Inhibition of COX activity by NSAIDs or ascorbate increases cAMP levels and enhances differentiation in 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-induced HL-60 cells. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2005;436:32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Bartke N, Hannun YA. Bioactive sphingolipids:metabolism and function. J Lipid Res. 2009;50:s91–s96. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800080-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Okazaki T, Bielawska A, Domae N, Bell RM, Hannun YA. Characteristics and partial purification of a novel cytosolic, magnesium-independent, neutral sphingomyelinase activated in the early signal transduction of 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-induced HL-60 cell differentiation. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:4070–4077. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Okazaki T, Bielawska A, Bell R, Hannun Y. Role of ceramide as a lipid mediator of 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-induced HL-60 cell differentiation. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:15823–15831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Kleuser B, Cuvillier O, Spiegel S. 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 inhibits programmed cell death in HL-60 cells by activation of sphingosine kinase. Cancer Res. 1998;58:1817–1824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Okazaki T, Bell R, Hannun Y. Sphingomyelin turnover induced by vitamin D3 in HL-60 cells. Role in cell differentiation. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:19076–19080. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Langmann T, Buechler C, Ries S, Schaeffler A, Aslanidis C, Schuierer M, Weiler M, Sandhoff K, de Jong PJ, Schmitz G. Transcription factors Sp1 and AP-2 mediate induction of acid sphingomyelinase during monocytic differentiation. J Lipid Res. 1999;40:870–880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Kim DS, Kim SH, Song JH, Chang YT, Hwang SY, Kim TS. Enhancing effects of ceramide derivatives on 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-induced differentiation of human HL-60 leukemia cells. Life Sci. 2007;81:1638–1644. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Katso R, Okkenhaug K, Ahmadi K, White S, Timms J, Waterfield MD. Cellular function of phosphoinositide 3-kinases: implications for development, homeostasis, and cancer. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2001;17:615–675. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.17.1.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Cantley CW. The phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway. Science. 2002;296:1655–1657. doi: 10.1126/science.296.5573.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Vanhaesebroeck B, Leevers SJ, Panayotou G, Waterfield MD. Phosphoinositide 3-kinases: a conserved family of signal transducers. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:267–272. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01061-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Hawkins PT, Anderson KE, Davidson K, Stephens LR. Signalling through class I PI3Ks in mammalian cells. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34:647–662. doi: 10.1042/BST0340647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Hanada M, Feng J, Hemmings BA. Structure, regulation and function of PKB/AKT-a major therapeutic target. Biochem Biophys Acta. 2004;1697:3–16. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2003.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Bozulic L, Hemmings BA. PIKKing on PKB activity by phosphorylation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21:256–261. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Bayascas JR. Dissecting the role of the 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 (PDK1) signalling pathways. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:2978–2982. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.19.6810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Haneline LS, White H, Yang FC, Chen C, Orschell C, Kapur R, Ingram DA. Genetic reduction of class IA PI-3 kinase activity alters fetal hematopoiesis and competative repopulating ability of hematopoietic stem cells in vivo. Blood. 2006;107:1375–1382. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Bugarski D, Kristic A, Mojsilovic S, Vlaski M, Petakov M, Jovcic G, Stojanovic N, Mikenkovic P. Signalling pathways implicated in hematopoietic progenitor proliferation and differentiation. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2007;232:156–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Lewis JL, Marley SB, Ojo M, Gordon MY. Opposing effects of PI3 kinase pathway activation on human myeloid and erythroid progenitor cell proliferation and differentiation in vitro. Exp Hematol. 2004;32:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2003.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Pearn L, Fisher J, Burnett AK, Darley RL. The role of PKC and PDK1 in monocyte lineage specification by Ras. Blood. 2007;109:4461–4469. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-047217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Buitenhuis M, Verhagen LP, van Deutekom HW, Castor A, Verploegen S, Koenderman L, Jacobsen SE, Coffer PJ. Protein kinase B (c-akt) regulates hematopoietic lineage choice decisions during myelopoiesis. Blood. 2008;111:112–121. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-037572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Marcinkowska E, Wiedlocha A, Radzikowski C. Evidence that phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and p70S6K protein are involved in differentiation of HL-60 cells induced by calcitriol. Anticancer Res. 1998;18:3507–3514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Pahl HL, Scheibe RJ, Zhang DE, Chen HM, Galson DL, Maki RA, Tenen DG. The proto-oncogene PU.1 regulates expression of the myeloid-specific Cd11b promoter. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:5013–5020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Chen HM, Pahl HL, Scheibe RJ, Zhang DE, Tenen DG. The Sp1 transcription factor binds the CD11b promoter specifically in myeloid cells in vivo and is essential for myeloid specific promoter activity. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:8230–8239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Zhang DE, Hetherington CJ, Tan S, Dziennis SE, Gonzalez DA, Chen HM, Tenen DG. Sp1 is critical factor for the monocyte specific expression of human CD14. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:11425–11434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Pan Z, Hetherington CJ, Zhang DE. CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein activates the CD14 promoter and mediates transforming growth factor β signaling in monocyte development. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:23242–2324. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.33.23242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Koschmieder S, Agarwal S, Radomska HS, Huettner CS, Tenen DG, Ottman OG, Berdel WE, Serve HL, Muller-Tidow C. Decitabine and vitamin D3 differentially affect hematopoietic transcripton factors to induce monocytic differentiation. Int J Oncol. 2007;30:349–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Moeenrezakhanlou A, Nandan D, Reiner NE. Identification of a calcitriol-regulated Sp-1 site in the promoter of human CD14 using a combined Western blotting electrophoresis mobility shift assay (WEMSA) Biol Proced Online. 2008;10:29–35. doi: 10.1251/bpo140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Huang YC, Chen JY, Hung WC. Vitamin D3 receptor/Sp1 complex is required for the induction of p27kip1expression by vitamin D3. Oncogene. 2004;23:4856–4861. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Cheng HT, Chen JY, Huang YC, Chang HC, Hung WC. Functional role of VDR in the activation of p27kip1 by the VDR/Sp1 complex. J Cell Biochem. 2006;98:1450–1456. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]