Abstract

We apply latent class analysis (LCA) to quantify multidimensional patterns of weight-loss strategies in a sample of 197 women, and explore the degree to which dietary restraint, disinhibition, and other individual characteristics predict membership in latent classes of weight-loss strategies. Latent class models were fit to a set of 14 healthy and unhealthy weight-loss strategies. BMI, weight concern, body satisfaction, depression, dietary disinhibition and restraint, and the interaction of disinhibition and restraint were included as predictors of latent class membership. All analyses were conducted with PROC LCA, a recently developed SAS procedure available for download. Results revealed four subgroups of women based on their history of weight-loss strategies: No Weight Loss Strategy (10.0%), Dietary Guidelines (26.5%), Guidelines+Macronutrients (39.4%), and Guidelines+Macronutrients+Restrict ive (24.2%). BMI, weight concerns, the desire to be thinner, disinhibition, and dietary restraint were all significantly related to weight-control strategy latent class. Among women with low dietary restraint, disinhibition increases the odds of engaging in any set of weight-loss strategies vs. none, whereas among medium- and high-restraint women disinhibition increases the odds of use of unhealthy vs. healthy strategies. LCA was an effective tool for organizing multiple weight-loss strategies in order to identify subgroups of individuals who have engaged in particular sets of strategies over time. This person-centered approach provides a measure weight-control status, where the different statuses are characterized by particular combinations of healthy and unhealthy weight-loss strategies.

Introduction

The current preoccupation with weight loss and dieting is reflected in the fact that Americans now spend over $33 billion dollars on diet-related products and services (1). In many studies, dieting is assessed by the use of a single question in which participants are simply asked to self-identify as currently dieting or not dieting. These studies reveal that dieting among women of all ages and body weights has become normative such that one in three American women report currently trying to lose weight (2). However, French et al. (3,4) suggest that a variety of specific weight-control strategies may be included under the rubric of “dieting” and that these differ in the extent to which they are consistent with current Dietary Guidelines (5). Specifically, women trying to lose weight frequently report using healthy weight-loss strategies (e.g., increase exercise, decrease fat, etc.) but a smaller percentage also report engaging in unhealthy weight-control behaviors, such as fasting or vomiting. Thus, assessing specific weight-control strategy use may be more informative than asking women to self-identify as “dieting.”

Modeling multidimensional patterns of behavior suggests the need to move away from variable-centered approaches such as regression analysis, toward person-centered approaches. As an example, a recent study used cluster analysis to identify three groups of overweight/obese individuals with disordered eating based on indicators of two restraint subscales (6). This approach revealed that the group characterized by high scores on items measuring both regimented and high lifestyle restraint had greater eating-specific pathology. Recent advances in statistical methods and software have opened up new possibilities for person-centered approaches to modeling patterns of behavior. One of these methods, latent class analysis (LCA) (7), is appropriate for identifying underlying (latent) subgroups in a population based on a set of indicators and examining the relations between individual characteristics and subgroup membership. LCA provides a way to identify subgroups of individuals who share similar patterns of weight-control strategies. The main objective of this study is to introduce LCA as an approach for identifying subgroups of women characterized by the weight-loss strategies they have used. This approach will provide substantially more information about individual differences in what constitutes dieting than simple, unidimensional reports of general dieting.

Although greater body dissatisfaction, greater weight concerns, and dietary restraint and disinhibition have been associated with self-reported dieting (8–15), their association with using specific combinations of healthy and/or unhealthy weight-control strategies is less well understood. Although several studies have demonstrated that restraint and disinhibition interact to affect weight status and dieting (16–18), no research has examined the moderating effect of restraint and disinhibition among women using specific weight-loss strategies. Thus, a secondary goal of this research is to examine relations between psychosocial characteristics and membership in weight-loss strategies latent classes.

The Weight Control Scale developed by French et al. (4) is used to address these questions. Based on previous research (3,4), we hypothesized that (i) distinct weight-loss strategy use groups will be identified, including a large group of women engaging in exclusively healthy weight-loss behaviors and a smaller group of women engaging in a combination of healthy and unhealthy strategies; (ii) BMI, weight concerns, dietary restraint, and disinhibited eating will strongly relate to the subgroups; and (iii) the odds of using healthy vs. unhealthy weight-loss strategies would vary by restraint and disinhibition level.

Methods and Procedures

Participants

Participants included 197 non-Hispanic white women living in central Pennsylvania recruited as part of a longitudinal study designed to examine parental influences on girls’ growth and development. Families with age-eligible female children within a 5-county radius were identified using available marketing information (Metromail, Chicago, IL). These families received mailings providing information about the study and were recruited using follow-up phone calls. Families were also recruited for participation using flyers and newspaper advertisements posted in local communities. Inclusion criteria focused on daughters’ characteristics: girls lived with both parents, did not have severe food allergies or chronic medical problems affecting food intake, and were not consuming vegetarian diets (absence of dietary restrictions involving animal products). Families were not recruited based on child or parent weight status or concern about weight. Only data for mothers are considered in this study. At study entry, women completed a series of self-report questionnaires during a scheduled visit to the laboratory. There were no missing data on reported weight-control strategies. The Pennsylvania State University Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures, and women provided consent for their family’s participation in the study before the initiation of data collection.

At study entry, the average age of participants was 35.4 (s.d. = 4.8). Reported household income was less than $20,000 for 7%, between $20,000 and $35,000 for 22%, between $35,000 and $50,000 for 35%, and above $50,000 for 36%. Thirty-five percent of women had a high school diploma, 50% had an associates degree or technical training, and 15% had a bachelor’s or master’s degree. Mean weight was 71.1 kg (s.d. = 16.3 kg; weight ranged from 45.5 to 149.1 kg) and mean BMI was 26.4 (s.d. = 6.1; BMI ranged from 17.7 to 56.2).

Measures

Weight-loss strategies

A wide range of healthy and unhealthy weight-loss strategies were assessed at wave 1 using an amended version of the Weight Loss Behavior Scale (4). This instrument consists of 24 items assessing the use of a set of specific weight-loss strategies used to lose weight during adulthood (example items include increasing exercise, eating less high-carbohydrate foods, and using diet pills). Items were measured on a 3-point response scale ranging from 0 (never since 18 years) to 2 (always). Dichotomous indicators of each weight-control strategy were created for this study: coded two if they have engaged in the behavior in their lifetime and one if they have not. These items were used as indicators of weight-loss strategies latent classes.

BMI and weight status

Height and weight measurements were assessed in triplicate by a trained staff member following the procedure outlined by Lohman et al. (19). Average height and weight were used to calculate BMI (weight (kg)/height (m)2).

Weight concerns

An amended version of the Weight Concerns Scale (20) was used to measure fear of weight gain, worry over weight and body shape, importance of weight, diet history, and perceived fatness at study entry. The measure consists of five items, each coded on a 5-point Likert response scale. An average Weight Concerns Scale score was created by calculating the mean of all five items and then standardizing the variable. In this study, internal consistency score of weight concerns was 0.82.

Desire to be thinner

The Body Figures Rating Scale developed by Stunkard, Sorenson, and Schulsinger measures perceptions about body size and is made up of nine body figures varying in shape (21). Participants indicate the figure that represents their ideal self and the figure that represents their actual self. A discrepancy score is created to represent the individual’s level of body satisfaction. Positive values indicate the desire to be heavier, zero values indicate body satisfaction, and negative values indicate the desire to be thinner or lose weight. For this study, a dichotomous variable was created to indicate women who expressed a desire to be thinner (coded one) and those who did not (coded zero).

Depression

Depression was assessed using the 20 item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale developed by Radloff (22). The Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale was designed to measure depressive symptoms, with a focus on depressed mood among adults in nonclinical populations. Participants indicate on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (rarely or none of the time) to 3 (most or all of the time) how frequently in the past week they have experienced a particular symptom. Scores range from 0 to 60. This scale also demonstrates good reliability (α = 0.89).

Dietary restraint and disinhibition

The Eating Inventory developed by Stunkard and Messick (23) was used to assess dietary restraint (21 items) and dietary disinhibition (16 items) at study entry. The restraint scale measures cognitive control of eating (e.g., “I consciously hold back at meals in order not to gain weight”). The dietary disinhibition scale measures loss of cognitive control of eating (e.g., “Sometimes when I start eating, I just can’t seem to stop”). Scores for each subscale are calculated by summing respective items. Both scales were standardized for this study. Internal consistency coefficients for restraint and disinhibition subscales were 0.87 and 0.83, respectively; the scales were not significantly correlated (r = 0.12, P = 0.09).

Analytic strategy: LCA

Latent class theory is a measurement theory, which posits that an underlying grouping variable (i.e., a latent class variable) is not observed but can be inferred from a set of categorical indicators. Often the latent class variable is used to organize multiple dimensions of behavior, such that individuals in each latent class share common behavior patterns. For example, Lanza and Collins (24) found five latent classes of sexual risk behavior, ranging from a latent class of nondaters to one characterized by multiple sexual partners with inconsistent condom use. LCA is similar in spirit to other “person-centered” approaches such as the more familiar cluster analysis, where individuals are grouped together based on common characteristics. Several conceptual introductions to LCA and extensions, such as including covariates to predict latent class membership, have appeared in the literature (7,25).

Parameters estimated in LCA include class membership probabilities and item-response probabilities. Class membership probabilities are of primary interest in most applications of LCA; they represent the proportion of a population expected to belong in each latent class. By definition, these probabilities sum to one. Item-response probabilities are parameters that link each observed item to each estimated latent class. They represent the probability of different responses to the items, conditional on latent class membership. The matrix of item-response probabilities provides the basis on which each latent class is interpreted and labeled. When covariates are included in the latent class model, odds ratios are obtained which describe the increase in odds of membership in a particular latent class (relative to a reference latent class) corresponding to a one-unit change in the covariate.

In order to reduce sparseness in the observed data contingency table, which is particularly important with a sample of this small size, an exploratory factor analysis was conducted to gain insight into the dimensionality of the weight-loss strategies reported by women. These results may suggest individual weight-loss strategies that can be combined with others in the latent class model without much loss of information. Once a final set of weight-loss strategy indicators was selected, latent class models with different numbers of latent classes were compared using the Akaike’s Information Criterion, Bayesian Information Criterion, and model interpretation.

Using the selected model, prediction of weight-loss strategies latent class membership proceeded in two steps. First, each of the following variables was included separately in the latent class model in order to examine the extent to which the covariate predicted membership in the weight-loss strategies latent classes: BMI, weight concern, body satisfaction (i.e., the desire to be thinner), depression, disinhibition, and dietary restraint. Next, an overall model predicting latent class membership from the entire set of covariates was estimated in order to examine the unique contribution of each covariate. In addition, the interaction between disinhibition and dietary restraint was included to test whether level of dietary restraint moderates the relation between disinhibition and latent class membership.

More technical details of LCA with covariates can be found elsewhere (7,25,26). All analyses were conducting using PROC LCA (16); this SAS procedure and its corresponding user’s guide are freely available for download at http://methodology.psu.edu/. Note that we include sample PROC LCA syntax in the Supplementary Appendix online.

Results

Latent class indicators

Preliminary factor analyses were conducted to create several aggregated superordinate weight-control strategy indicators. The original list of 24 weight-loss strategies was reduced to 14 general weight-loss strategies; the prevalence of each general strategy appears in Table 1. Items that did not load on any primary factors, such as eating less high-carbohydrate foods, were retained as unique latent class indicators.

Table 1.

Percent of total sample (N = 197) and probability of women reporting “ever using” each weight-loss strategy given latent class membership

| Total sample | Latent class | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight-loss strategy | Percent reporting yes | No Weight Loss Strategy (10.0%) | Dietary Guidelines (26.5%) | Guidelines+Macro.(39.4%) | Guidelines+Macro.+Restrictive (24.2%) |

| Eat more fruits and vegetables | 86 | 0.05 | 0.82 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Increasing exercise | 86 | 0.09 | 0.89 | 0.97 | 0.98 |

| Eat less fat | 86 | 0.05 | 0.86 | 1.00 | 0.96 |

| Eliminate sweets, junk food, snacking | 89 | 0.14 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.98 |

| Reduce amount of food and total calories | 89 | 0.10 | 0.92 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Change type of foods eaten | 78 | 0.00 | 0.59 | 0.96 | 1.00 |

| Eat less meat | 65 | 0.00 | 0.46 | 0.77 | 0.91 |

| Eat less high-carbohydrate foods | 41 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.61 | 0.69 |

| Skipping meals | 48 | 0.10 | 0.36 | 0.41 | 0.90 |

| Appetite suppressants, liquid diets, diet pills | 36 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.37 | 0.83 |

| Decrease alcohol consumption | 36 | 0.04 | 0.17 | 0.39 | 0.63 |

| Fasting | 18 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.67 |

| Attend weight-loss support groups with or without food | 19 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.34 | 0.25 |

| Laxatives or enemas, diuretics, vomiting | 10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.33 |

Participants were asked whether they had used each weight-loss strategy as an adult (from 19 years of age to present).

Macro., macronutrient.

Four-class model of weight-loss strategies

Models with one through four latent classes were compared in order to select a model with the optimal balance of fit and parsimony (model identification for models involving more than four latent classes was not sufficient to allow reliable estimation). For all models, the 14 items listed in Table 1 were included as the latent class indicators. Based on the Akaike’s Information Criterion (1,071 for model with one latent class, 616 with two, 498 with three, and 480 with four), the Bayesian Information Criterion (1,117 for model with one latent class, 711 with two, 642 with three, and 675 with four), and a careful inspection of the parameter estimates we selected the four-class model.

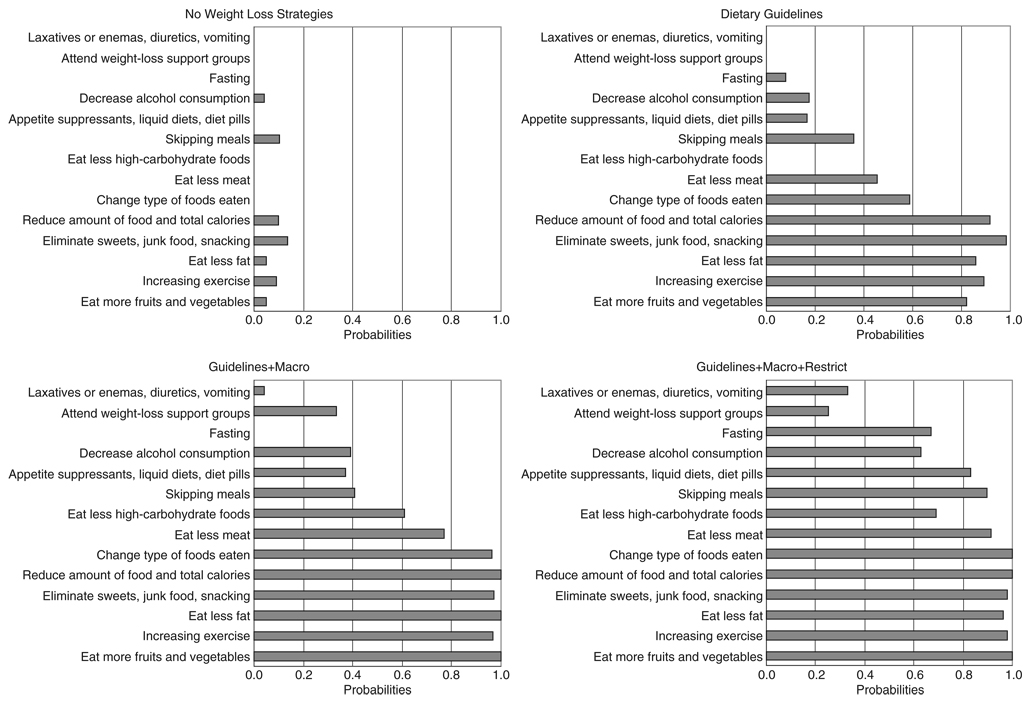

Table 1 also shows the probability of endorsing each weight-loss strategy for individuals in each of the four latent classes. These item-response probabilities provide a basis for interpreting and labeling the four latent classes. For example, a particular latent class is characterized by weight-loss strategies with probabilities close to one (indicating that individuals in that class are likely to report having tried those particular strategies) but not by strategies with probabilities close to zero (indicating that they are unlikely to have tried those strategies). As shown in Table 1, 10% of individuals were expected to belong in latent class 1, characterized by a low probability of reporting each weight-control strategy; these individuals will be referred to as the “No Weight Loss Strategies” latent class. Individuals in latent class 2 (26.5%), the “Dietary Guidelines” latent class, have a high probability of reporting use of strategies consistent with healthy practices present in current guidelines, such as increased fruits and vegetables intake, increased exercise, decreased fat intake, eliminating certain foods, and reducing calories. Latent class 3 (39.4%) was referred to as “Guidelines+Macronutrient” because they have a high probability of reporting trying a low-carbohydrate diet. Finally, latent class 4, which will be labeled “Guidelines+Macronutrient+ Restrictive” (24.2%), is comprised of individuals who report having tried nearly all weight-loss strategies, including both healthy and unhealthy strategies. This is the only subgroup of individuals who were likely to report skipping meals; use of appetite suppressants/liquid diets/diet pills; reducing alcohol consumption; and fasting. Figure 1 depicts the item-response probabilities for each of the four latent classes.

Figure 1.

Probability of reporting each weight-loss strategy conditional on membership in latent class (N = 197). Weight-loss latent classes were identified using latent class analysis: women reporting that they use No Weight Loss Strategies (10.0%), Dietary Guidelines (26.5%), Dietary Guidelines+Macronutrient (39.4%), or Dietary Guidelines+Macronutrients+Restrictive strategies (24.2%).

Characteristics predicting latent class membership

The following individual characteristics were included as independent predictors of the latent classes of weight-loss strategies: BMI, weight concern, body satisfaction (i.e., the desire to be thinner), depression, disinhibition, and dietary restraint. As shown in Table 2, all covariates except depression were significantly related to latent class membership (P < 0.001 for each covariate). Table 2 shows the increase in odds of membership in the Dietary Guidelines, Guidelines+Macronutrients, and G uidelines+Macronutrients+Restrictive latent classes relative to the No Weight Loss Strategy latent class corresponding to a one-unit increase in the covariate. For example, for every one-unit increase in BMI there is a 60% increase in odds of membership in the Dietary Guidelines class, a 90% increase in odds of membership in the Guidelines+Macronutrient class, and 70% increase in odds of membership in the Guidelines+Macro nutrient+Restrictive latent class relative to the No Weight Loss Strategy class. Weight concern, the desire to be thinner, and dietary restraint were most strongly related to membership in the Guidelines+Macronutrient+Restrictive class relative to the No Weight Loss Strategy class (odds ratio (OR) = 9.5, OR = 124.8, and OR = 36.0, respectively). A one-unit increase in disinhibition was equally predictive of membership in the Guidelines+Macronutrient class and Guidelines+Macronutrient+Restrictive class relative to the No Weight Loss Strategy class (OR = 19.4 and OR = 19.9, respectively). Next, the Dietary Guidelines group was re-specified as the reference class to examine the extent to which the covariates increased the odds of membership in an unhealthy weight-loss strategies class relative to a healthy weight-loss strategies class. A similar pattern of results emerged such that the strongest predictor of membership in the Guidelines+Macronutrient+Restrictive class relative to the Dietary Guidelines class was body satisfaction (OR = 9.4), followed by dietary restraint (OR = 5.1), weight concern (OR = 3.1), and disinhibition (OR = 2.7).

Table 2.

Odds ratios for individual effects of predictors on membership in weight-loss strategies latent class

| P value | No Weight Loss Strategy (10.0%) | Dietary Guidelines (26.5%) | Guidelines+Macro. (39.4%) | Guidelines+Macro.+Restrictive (24.2%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Weight Loss Strategy as reference class | |||||

| BMI | ** | (1.0) | 1.6 | 1.9 | 1.7 |

| Weight concern (z-score) | ** | (1.0) | 3.0 | 6.9 | 9.5 |

| Body satisfaction | ** | (1.0) | 13.2 | 76.6 | 124.8 |

| Depression | * | (1.0) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 |

| Disinhibition (z-score) | ** | (1.0) | 7.3 | 19.4 | 19.9 |

| Dietary restraint (z-score) | ** | (1.0) | 7.0 | 22.1 | 36.0 |

| Dietary Guidelines as reference class | |||||

| BMI | ** | 0.6 | (1.0) | 1.2 | 1.1 |

| Weight concern (z-score) | ** | 0.3 | (1.0) | 2.3 | 3.1 |

| Body satisfaction | ** | 0.1 | (1.0) | 5.8 | 9.4 |

| Depression | * | 1.0 | (1.0) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Disinhibition (z-score) | ** | 0.1 | (1.0) | 2.7 | 2.7 |

| Dietary restraint (z-score) | ** | 0.1 | (1.0) | 3.2 | 5.1 |

Predictors entered in separate logit models; reference latent class has odds ratio of 1.0 (listed in parentheses). Increase in log-odds of membership in latent class relative to membership in reference class corresponding to one-unit change in predictor.

Macro., macronutrient.

P < 0.10.

P < 0.001.

Results of the overall model predicting latent class membership from the entire set of covariates, including the interaction between disinhibition and dietary restraint, are shown in Table 3. P values are reported for the overall effect of each covariate controlling for the others. BMI, weight concern, and body satisfaction were no longer significant predictors when included in the overall model, although disinhibition (P < 0.05) and dietary restraint (P < 0.001) significantly predicted weight-loss strategies latent class membership. The interaction of disinhibition and dietary restraint was also significant (P < 0.05) indicating that moderation was present. To facilitate interpretation of this interaction, we calculated the ORs that correspond to a one-unit change in disinhibition for low, medium, and high values of dietary restraint (see Table 4). “Low” corresponds to 1 s.d. below the mean in dietary restraint, “medium” corresponds to the mean level of restraint, and “high” corresponds to one standard deviation above the mean level of restraint. Among low restraint women, a one-unit increase in disinhibition corresponds to higher odds of membership in the Dietary Guidelines class, Guidelines+Macronutrients class, and Guidelines+Macro nutrients+Restrictive class relative to the No Weight Loss Strategy class (OR = 2.3, OR = 2.9, and OR = 4.4, respectively). However, among these women an increase in disinhibition corresponds to only a small increase of odds in the Guidelines+Macronutrients class and Guidelines+Macronutrients+Restrictive class relative to the Dietary Guidelines class (OR = 1.3 and OR = 1.9, respectively). In other words, among women in the low-restraint group, disinhibition was most strongly related to the incidence of any weight-loss strategies, as opposed to the incidence of healthy or unhealthy weight-loss strategies in particular.

Table 3.

Parameter estimates from full prediction models for latent class membership

| P value | No Weight Loss Strategy (10.0%) | Dietary Guidelines (26.5%) | Guidelines+Macro. (39.4%) | Guidelines+Macro.+Restrictive (24.2%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Weight Loss Strategy as reference class | |||||

| Intercept | (0.0) | −3.80 | −5.28 | −4.17 | |

| BMI | * | (0.0) | 0.23 | 0.34 | 0.27 |

| Weight concern (z-score) | ns | (0.0) | 0.23 | 0.90 | 0.85 |

| Body satisfaction | ns | (0.0) | 1.60 | 1.46 | 0.83 |

| Depression | ns | (0.0) | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.08 |

| Disinhibition (z-score) | ** | (0.0) | −1.26 | 0.31 | 0.59 |

| Dietary restraint (z-score) | † | (0.0) | 0.98 | 2.53 | 2.75 |

| Disinhibition × restraint | ** | (0.0) | −2.07 | −0.75 | −0.88 |

| Dietary Guidelines as reference class | |||||

| Intercept | 3.80 | (0.0) | −1.48 | −0.37 | |

| BMI | * | −0.23 | (0.0) | 0.11 | 0.03 |

| Weight concern (z-score) | ns | −0.23 | (0.0) | 0.67 | 0.62 |

| Body satisfaction | ns | −1.60 | (0.0) | −0.14 | −0.77 |

| Depression | ns | −0.05 | (0.0) | −0.03 | 0.03 |

| Disinhibition (z-score) | ** | 1.26 | (0.0) | 1.57 | 1.85 |

| Dietary restraint (z-score) | † | −0.98 | (0.0) | 1.54 | 1.76 |

| Disinhibition × restraint | ** | 2.07 | (0.0) | 1.32 | 1.19 |

Parameter estimates are β-coefficients from logistic regression model predicting latent class membership from set of predictors entered together.

Macro., macronutrient; ns, nonsignificant.

P < 0.10.

P < 0.05.

P < 0.01.

P < 0.001.

Table 4.

Odds ratios reflecting effect of disinhibition on odds of membership in weight-loss strategies latent class for women with low-, mean-, and high-dietary restraint

| Weight-loss strategies latent class |

Level of dietary restraint | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Mean | High | |

| No Weight Loss Strategy as reference class | |||

| Dietary Guidelines | 2.3 | 0.3 | 0.0 |

| Guidelines+Macronutrient | 2.9 | 1.4 | 0.6 |

| Guidelines+Macronutrient+Restrictive | 4.4 | 1.8 | 0.8 |

| Dietary Guidelines as reference class | |||

| Guidelines+Macronutrient | 1.3 | 4.8 | 18.0 |

| Guidelines+Macronutrient+Restrictive | 1.9 | 6.4 | 20.9 |

Odds ratios represent the increase in odds of membership in a particular weight-loss strategies latent class (relative to the specified reference latent class) corresponding to a one-unit increase in disinhibition. For example, among low-restraint women a one-unit increase in disinhibition corresponds to being 2.3 times more likely to be in the Dietary Guidelines class relative to being in the No Weight Loss Strategy class.

Turning to the high-restraint women, Table 4 shows that a one-unit increase in disinhibition corresponds to lower odds of membership in the Dietary Guidelines class, Guidelines+Macronutrients class, and Guidelines+Macronutrients+Restrictive class relative to the No Weight Loss Strategy class (OR = 0.0, OR = 0.6, and OR = 0.8, respectively), but substantially higher odds of membership in the Guidelines+Macronutrients class and Guidelines+Macronutrients+Restrictive class relative to the Dietary Guidelines class (OR = 18.0 and OR = 20.9, respectively). In other words, among the high-restraint women, a one-unit increase in disinhibition relates to lower odds of weight control in general. However, given that they are engaging in some set of weight-loss strategies, they are substantially more likely to engage in unhealthy restrictive strategies vs. healthy ones. For example, among high-restraint women, a one-unit increase in disinhibition corresponds to being 20.9 times more likely to be in the Guidelines+Macronutrient+Restrictive class relative to the Dietary Guidelines class.

In sum, among low-restraint women (i.e., women who report lower cognitive control of food intake), disinhibition (i.e., the loss of cognitive control of food intake) increased the odds of engaging in any weight-loss strategies vs. none, whereas among medium- and high-restraint women disinhibition increased the odds of engaging in unhealthy vs. healthy weight-loss strategies. There was a stronger effect of disinhibition on unhealthy vs. healthy weight-loss behavior as dietary restraint increased.

Discussion

Results of the LCA analyses revealed four distinct groups of women defined by the patterns of weight-loss strategies they used in their attempts to lose weight. These patterns differed in the range of strategies used, and as predicted in the extent to which the strategies endorsed were limited to those consistent with current dietary guidelines, or also included unhealthy approaches. Typologies of weight-loss strategy use also differed on several independent psychosocial factors that have previously been linked to dieting (8–15). Specifically, weight concerns, the desire to be thinner, dietary restraint, and disinhibition were most strongly related to membership in the Guidelines+Macronutrient+Restrictive class relative to the No Weight Loss Strategy. Furthermore, the effect of disinhibition on use of unhealthy vs. healthy weight-control strategy use varied at different levels of dietary restraint.

The primary aim of this study was to introduce LCA as a person-centered approach for identifying subgroups of women characterized by the weight-loss strategies they have used. Our finding demonstrated that LCA was an effective tool for organizing multiple weight-loss strategies, providing a more nuanced understanding of weight-loss strategies used by women than what could be obtained from any single questionnaire item that assesses “global reports of dieting” (such as “Have you ever dieted?”). By taking a latent variable approach, we were able to describe how the 14 different weight-loss strategies can be used in different combinations within groups of individuals, and then relate the latent classes to a variety of individual characteristics. As hypothesized and similar to previous reports (4,14,15,27), greater body dissatisfaction, restrained and disinhibited eating, and weight concerns were predictive of reduced macronutrient intakes and engagement in unhealthy, restrictive weight-loss strategies.

A secondary aim of this research was also to examine the interactive effect between restraint and disinhibition on the reported use of a combination of healthy and or unhealthy weight-loss strategies. Although no study, to date, has posed this question, we hypothesized that level of restraint and disinhibition would predict group membership differently based on previous research suggesting that dietary restraint is a multidimensional construct, encompassing both past and current dieting (12,28) and evidence that restraint moderates the impact of disinhibition on body weight and dieting (16–18). As predicted, our results revealed that disinhibition increased the odds of engaging in any weight-loss strategy when restraint was low; whereas, disinhibition increased the odds of engaging in unhealthy compared to healthy weight-loss strategies when restraint was high. Several observational feeding studies have demonstrated that highly restrained eaters compared to unrestrained eaters tend to eat greater amounts of highly palatable “forbidden” foods and binge more frequently (29,30). In combination, these findings suggest that being both highly restrained and disinhibited may be a strong predictor of unhealthy, extreme weight-loss behavior that may ultimately be counterproductive.

This study relied on a single scale reflecting dietary restraint, although we also modeled weight-loss strategy latent classes as a function of rigid restraint and flexible restraint subscales. Not surprisingly, as the subscales were highly correlated (r = 0.79), results based on each subscale were nearly identical to those based on the single dietary restraint scale. Although Stice et al. (31,32) suggest that dietary restraint is not a valid measure of caloric intake or short-term caloric restriction, it is unclear whether self-reported use of unhealthy weight-loss strategies is predictive of caloric intake. Thus, additional research is warranted.

LCA has conceptual parallels to cluster analysis in that both statistical methods share the goal of identifying subgroups, or clusters, of individuals with similar characteristics, although in cluster analysis the indicators are continuous variables (as opposed to categorical ones in LCA). Cluster analysis relies on fairly arbitrary rules for selecting the number of clusters. In addition, this approach does not incorporate measurement error despite the fact that individual items do not correspond perfectly with cluster membership. LCA is a measurement model for categorical latent variables. The item-response probabilities account for the fact that items do not perfectly relate to latent class membership and quantify measurement error, and model fit statistics can be used to help determine the optimal number of latent classes. Recent advances in software availability, including PROC LCA (16; available for download at http://methodology.psu.edu) used in this study, as well as extensions to the statistical model, have resulted in increased use of LCA in the behavioral sciences. This method has great potential for improving our ability to measure complex behavioral statuses such as weight-loss strategies and disordered eating. Specifically, LCA provides more nuanced descriptions of individuals allowing for better measurement, and therefore understanding, of the complex behaviors involved in weight control.

Although not a primary aim, this study also examined whether women who employ particular sets of weight-loss strategies are more likely to be overweight than those who use different (or no) weight-loss strategies. To explore this, we used recommendations made by the World Health Organization (33) to classify women as either normal (N = 94; BMI <25) or overweight (N = 103, BMI ≥25). Results revealed that overweight women were much more likely to be in the Guidelines+Macronutrient class (57.6% vs. 20.1% among normal-weight women) and less likely to be in the No Weight Loss Strategy class (0.0% vs. 20.1% among normal-weight women) or Dietary Guidelines class (18.8% vs. 42.3% among normal-weight women). These findings suggest that interventions could be targeted toward women using particular weight-control strategies. Interestingly, the percentage of women in the Guidelines+Macronutrient+Restrictive class was similar for normal and overweight women, with 17.5% and 23.6%, respectively. Moreover, although the data were not presented, post hoc analyses revealed that overweight women reported significantly greater weight concerns, depression scores, disinhibited and restrained eating and a greater percent reported a desire to be thinner compared to normal-weight women.

This study is not without limitations. First, this sample was racially and demographically homogenous, and included only women, this may be one reason why it was not necessary to control for certain variables such as age, income, education, or maternal work hours. Therefore, these results may be limited in terms of how they would generalize to men and other ethnic, racial, income, or education groups. A second limitation is that, as with any study, generalizability of findings may be limited by the timing of data collection. In this case, the identification of a Guidelines+Macronutrient latent class may partly be driven by fad diets that were commonly practiced at the time of the study. For example, the popularity of low-carbohydrate diets during the late 1990s may have contributed to our ability to identify this unique class. Third, weight-loss strategy use was self-reported, which may be biased (likely reflecting underreporting of unhealthy behaviors).

In conclusion, four subgroups of women were identified based on a set of 14 healthy and unhealthy weight-loss strategies: the No Weight Loss Strategy class, the Dietary Guidelines class, the Guidelines+Macronutrients class, and the Guidelines+Macronutrients+Restrictive class. BMI, weight concerns, the desire to be thinner, disinhibition, and dietary restraint were all significantly related to weight-loss strategies latent class membership. Among women with low dietary restraint, disinhibition increased the odds of engaging in any weight-loss strategies vs. none, whereas among medium- and high-restraint women disinhibition increases the odds of engagement in unhealthy vs. healthy weight-loss strategies. LCA was demonstrated to be an effective method for quantifying multidimensional patterns of women’s weight-loss strategies. This person-centered approach provided a detailed measure of weight-loss behavior, where different latent classes are characterized by particular combinations of healthy and unhealthy weight-loss strategies. An important future direction will be to study the relation among weight-loss strategy latent classes and more distal outcomes such as weight and weight change, as well as continued unhealthy weight-loss practices.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant NIH HD 32973, The National Dairy Council, and by the National Institute on Drug Abuse grants P50DA10075 and R03DA023032. The services provided by the General Clinical Research Center of the Pennsylvania State University (supported by the NIH Grant M01 RR10732) are appreciated. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or the National Institutes of Health. We thank Brittany Rhoades for helpful comments on an early draft of the manuscript.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is linked to the online version of the paper at http://www.nature.com/oby

DISCLOSURE

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cleland R, Graybill DC, Hubbard V, et al. Commercial weight loss products and programs: what consumers stand to gain and lose. A public conference on the information consumers need to evaluate weight loss products and programs. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2001;41:45–70. doi: 10.1080/20014091091733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kruger J, Galuska DA, Serdula MK, Jones DA. Attempting to lose weight: specific practices among U.S. adults. Am J Prev Med. 2004;26:402–406. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.French SA, Jeffery RW, Murray D. Is dieting good for you? Prevalence, duration and associated weight and behaviour changes for specific weight loss strategies over four years in US adults. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999;23:320–327. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.French SA, Perry CL, Leon GR, Fulkerson JA. Dieting behaviors and weight change history in female adolescents. Health Psychol. 1995;14:548–555. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.14.6.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Department of Health and Human Services and US Department of Agriculture. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2005. 2005 January;

- 6.White MA, Masheb RM, Grilo CM. Regimented and lifestyle restraint in binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2009;42:326–331. doi: 10.1002/eat.20611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lanza ST, Collins LM, Lemmon DR, Schafer JL. PROC LCA: A SAS procedure for latent class analysis. Struct Equation Model. 2007;14:671–694. doi: 10.1080/10705510701575602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lowe MR. Restrained eating and dieting: replication of their divergent effects on eating regulation. Appetite. 1995;25:115–118. doi: 10.1006/appe.1995.0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stice E, Bearman SK. Body-image and eating disturbances prospectively predict increases in depressive symptoms in adolescent girls: a growth curve analysis. Dev Psychol. 2001;37:597–607. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.37.5.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodrick GK, Poston WS, Foreyt JP. Methods for voluntary weight loss and control: update 1996. Nutrition. 1996;12:672–676. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(96)00243-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cachelin FM, Regan PC. Prevalence and correlates of chronic dieting in a multi-ethnic U.S. community sample. Eat Weight Disord. 2006;11:91–99. doi: 10.1007/BF03327757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lowe MR. The effects of dieting on eating behavior: a three-factor model. Psychol Bull. 1993;114:100–121. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.1.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lowe MR, Timko CA. What a difference a diet makes: towards an understanding of differences between restrained dieters and restrained nondieters. Eat Behav. 2004;5:199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Putterman E, Linden W. Appearance versus health: does the reason for dieting affect dieting behavior? J Behav Med. 2004;27:185–204. doi: 10.1023/b:jobm.0000019851.37389.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson LA, Eyler AA, Galuska DA, Brown DR, Brownson RC. Relationship of satisfaction with body size and trying to lose weight in a national survey of overweight and obese women aged 40 and older, United States. Prev Med. 2002;35:390–396. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2002.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hays NP, Bathalon GP, McCrory MA, et al. Eating behavior correlates of adult weight gain and obesity in healthy women aged 55–65 y. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;75:476–483. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/75.3.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williamson DA, Lawson OJ, Brooks ER, et al. Association of body mass with dietary restraint and disinhibition. Appetite. 1995;25:31–41. doi: 10.1006/appe.1995.0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lawson OJ, Williamson DA, Champagne CM, et al. The association of body weight, dietary intake, and energy expenditure with dietary restraint and disinhibition. Obes Res. 1995;3:153–161. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1995.tb00131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lohman T, Roche A, Martorell R. Anthropometric Standardization Reference Manual. Illinois: Human Kinetics Book; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Killen JD, Taylor CB, Hayward C, et al. Pursuit of thinness and onset of eating disorder symptoms in a community sample of adolescent girls: a three-year prospective analysis. Int J Eat Disord. 1994;16:227–238. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199411)16:3<227::aid-eat2260160303>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stunkard AJ, Sørensen T, Schulsinger F. Use of the Danish Adoption Register for the study of obesity and thinness. Res Publ Assoc Res Nerv Ment Dis. 1983;60:115–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-reported depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stunkard AJ, Messick S. The three-factor eating questionnaire to measure dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger. J Psychosom Res. 1985;29:71–83. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(85)90010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lanza ST, Collins LM. A new SAS procedure for latent transition analysis: transitions in dating and sexual risk behavior. Dev Psychol. 2008;44:446–456. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.2.446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Collins LM, Lanza ST. Latent Class and Latent Transition Analysis for the Social, Behavioral, and Health Sciences. New York: Wiley; in press. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lanza ST, Lemmon DR, Schafer JL, Collins LM. PROC LCA & PROC TLA User’s Guide Version 1.1.1 beta 2007. University Park: The Methodology Center, Penn State; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Provencher V, Drapeau V, Tremblay A, et al. Eating behaviours, dietary profile and body composition according to dieting history in men and women of the Québec Family Study. Br J Nutr. 2004;91:997–1004. doi: 10.1079/BJN20041115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lowe MR, Foster GD, Kerzhnerman I, Swain RM, Wadden TA. Restrictive dieting vs. “undieting” effects on eating regulation in obese clinic attenders. Addict Behav. 2001;26:253–266. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00106-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soetens B, Braet C, Van Vlierberghe L, Roets A. Resisting temptation: effects of exposure to a forbidden food on eating behaviour. Appetite. 2008;51:202–205. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mills JS, Palandra A. Perceived caloric content of a preload and disinhibition among restrained eaters. Appetite. 2008;50:240–245. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stice E, Cooper JA, Schoeller DA, Tappe K, Lowe MR. Are dietary restraint scales valid measures of moderate- to long-term dietary restriction? Objective biological and behavioral data suggest not. Psychol Assess. 2007;19:449–458. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.4.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stice E, Fisher M, Lowe MR. Are dietary restraint scales valid measures of acute dietary restriction? Unobtrusive observational data suggest not. Psychol Assess. 2004;16:51–59. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.16.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.World Health Organization. Geneva, Switzerland: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic. Report of a WHO Consultation on Obesity World Health Organization. 1998 [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.