Abstract

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) is now widely used to study human brain function. Alert monkey fMRI experiments have been used to localize functions and to compare the workings of the human and the monkey brain. Monkey fMRI poses considerable challenges because of the monkey's small brain and naturally uncooperative disposition. While training can encourage monkeys to be more obliging during scanning, the usual procedure is to hold the monkey's head motionless by means of a surgically implanted head post. Such implants are invasive and require regular maintenance. In order to overcome these problems we developed a technique for holding monkeys' heads motionless during scanning using a custom-fitted plastic helmet, a chin strap, and a mild suction supplied by a vacuum blower. This vacuum helmet method is totally non-invasive and has shown no adverse effects after repeated use for several months. The motion of a trained monkey's head in the helmet during scanning was comparable to that of a trained monkey implanted with a conventional head post.

Keywords: monkeys, fMRI, helmet

INTRODUCTION

Decades of work using invasive neurophysiological recording techniques in macaques have provided us with extensive knowledge about the functional organization of the primate brain. Indeed, the macaque monkey model is the basis for much of our understanding of sensory, motor, and cognitive processing in humans. Noninvasive imaging techniques, such as positron emission tomography (PET), functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI, and magneto-encephalography (MEG), now provide a wealth of information on the workings of the human brain. To compare monkey and human brain data and to take advantage of the localizing power of fMRI, several laboratories have started doing functional MRI on monkeys. Some early monkey fMRI studies were done on anesthetized animals and proved its usefulness in localizing early sensory processes (Logothetis et al. 1999). Using anesthetized monkeys has the advantage that it does not require restraint or extensive training, but it cannot be used to map higher cognitive functions, therefore most laboratories have worked out ways to scan alert behaving monkeys (Dubowitz et al. 1998; Stefanacci et al. 1998; Logothetis et al. 1999; Vanduffel et al. 2001; Andersen et al. 2002; Tsao et al. 2003a; Tsao et al. 2003b; Gamlin et al. 2006; Keliris et al. 2007; Hadj-Bouziane et al. 2008; Maier et al. 2008; Durand et al. 2009; Goense et al. 2009; Peeters et al. 2009).

Scanning awake monkeys is uniquely challenging. The main difficulty is that computing a reliable activation map requires a stationary brain—the activity-driven signal changes are small, and movement of the brain inside the magnetic field produces inconsistencies in phase and amplitude, which can generate blurring and ghosting motion artifacts larger than the activation signals. In most laboratories a head-post that is surgically implanted onto the skull is used to keep the monkey's head stationary during the scan session. Metal headposts have been used for decades in neurophysiological recording, and plastic versions are now used for fMRI. The acrylic used to cement the post to the skull can cause scanning artifacts, can damage the underlying skull, and requires regular maintenance.

Several laboratories have tackled the challenge of non-invasive imaging of alert monkeys: Howell and colleagues developed a plastic helmet filled with expandable foam that fits snugly to the subject's head. This method allows PET scanning of alert monkeys (Howell et al. 2001), but the encompassing foam does not allow visual stimulation. Others have scanned alert marmosets in restraint chairs (Ferris et al. 2001; Ferris et al. 2004), but putting the animal in this restraint requires anesthesia, which must then be reversed for scanning. Another fMRI approach used with macaques (Andersen et al. 2002; Joseph et al. 2006) still requires ear-bars and skull pins.

In order to circumvent the problems of surgery, chronic acrylic implants, and susceptibility artifacts from the acrylic, we developed a non-invasive method for stabilizing monkeys' heads in a scanner. We found that head motion in our method is comparable to that of a head-post fixed monkey.

METHODS

Four rhesus macaque monkeys participated in these experiments: three males, 3, 3.5 and 10 years old weighing, respectively, 5.5, 6, and 10kg, and one 6.5kg female. The oldest male monkey has a delrin headpost affixed to his skull with ceramic screws and dental acrylic (Vanduffel et al. 2001) and has had several years of experience being scanned repeatedly (Tsao et al. 2003a; Tsao et al. 2006). The two smaller male monkeys had no headpost implants and had 3 months biweekly training restrained by the vacuum helmet in a mock scanner before being scanned in a real scanner.

The female monkey had a delrin headpost affixed to the skull with ceramic screws and dental acrylic and was scanned several times with the headpost, then, during a routine cage transfer, she leaped through the door of her cage and knocked the headpost off. The scalp skin was immediately sutured closed over the headpost site, and after 5 months of rest she was trained to use the helmet in a mock scanner and later scanned using the helmet. We used this female monkey to directly compare movement during scanning with a headpost vs the helmet.

Helmet and vacuum details

The helmet was fabricated by first making a 3D digital model of the monkey's head, based on a plaster cast and an anatomical MRI. We then constructed a 3D digital model of a helmet that would fit around the head model using SolidWorks 3D CAD software (Concord MA). The design incorporated a post for attaching the helmet to the scanning chair, grooves for silicon tubing, and two ports for vacuum. The helmet was then manufactured directly from the digital model by stereo-lithography from a UV polymerized resin (Vaupell, Agawam, MA). Two rings of soft silicon tubing were bonded into concentric shallow grooves inside the helmet and served to partially seal and cushion the monkey's head inside the helmet. The monkey's fur was not shaved or trimmed. A Velcro chin strap and a vacuum of 2 pounds/sq inch (psig) held the monkey's head stationary in the helmet (Figure 1). The chinstrap and helmet alone allowed rotation of the head inside the helmet, but the gentle suction provided enough friction against the silicon rings that it inhibited the monkey from moving his head. We initially used a household canister vacuum, with a bleed valve to reduce the vacuum, and subsequently switched to a quieter industrial vacuum (Fuji regenerative blower model VFD3S, maximum vacuum 4.8 psi) fitted with a relief valve (Fuji VV5) to keep the vacuum under 2psig. No adverse effects, such as bruising or swelling, have been observed after several months of use as long as the pressure is kept at or under −2 psig.

Figure 1.

The vacuum helmet (left) and an alert monkey (right) sitting calmly, in the helmet, ready to be scanned.

Training

Each monkey was trained to sit in a horizontal chair and was habituated to recorded sounds of MR scanning in a mock MR bore. It sat comfortably on its haunches, in a “sphinx” position. The monkeys' daily water access was delayed prior to each training or scanning session, and behavioral control was achieved using operant conditioning techniques. The monkeys were trained on a fixation task, and gaze direction was monitored using a pupil–corneal reflection tracking system (RK-726PCI, ISCAN, Cambridge, MA). The monkeys were rewarded with water or juice drops for maintaining fixation within a square fixation window (2° on a side). In order to encourage sustained periods of fixation, the interval between rewards was decreased systematically (from 2000 to 1000 msec) as the monkey maintained fixation within the window during the trials; as the scan progressed the intervals were further decreased to maintain motivation. After fixation performance reached asymptote in the mock scanner (after 20–50 training sessions), the monkeys were scanned in a 3-T horizontal GE Signa Excite scanner.

Scanning

A custom-made 4 channel receive coil (Resonance Innovations LLC, Omaha, NE) fitted around the helmet and covered the entire brain. In order to enhance contrast, before each scanning session each monkey was injected with microparticular iron oxide contrast agent (Leite et al. 2002; Leite and Mandeville 2006). For one functional mapping session with a helmet-restrained monkey we injected i.v. 20mg/kg of P904, a nanosized ultrasmall particle of iron oxide (USPIO) kindly supplied by Guerbet (Guerbet Research, Aulnay-Sous-Bois, France). For a second functional scan session in the same monkey (generating the results shown in figure 5) we used 12mg/kg Feraheme (AMAG Pharmaceuticals, Cambridge, MA) which is an iron oxide nanoparticle with a polyglucose sorbitol coaboxymethylether coating. We obtained comparable contrast enhancement with the two agents, but the Feraheme had a much longer half life (>15 hours compared to 1.5 hours for the P904). Each session consisted of 10-30 functional scans, each scan lasting 260 seconds (100 seconds for some of the earlier scan sessions). The raw movement data shown in figures 2 & 4 were taken during a single, typical, scan session for each monkey; the averaged data in figures 3 & 4 were averaged from 200 scans made during 8-10 scan sessions, and comprised 16000 functional volumes. The scans that were averaged comprised all the scan sessions for that particular monkey over a several-week period, with the only selection criterion being that the monkey fixated more than 80% of the duration of the scan (except for the female monkey who does not fixate as well, and for whom the criterion was 70%). The activation maps shown in figure 5 for the helmeted monkey were calculated from 20 scans from one scan session (260 functional volumes, 9100 slices), using the following scanning parameters: 2-D Gradient-Echo Planar Imaging (GE-EPI); Repetition Time (TR) = 2 Sec, Echo Time (TE) = 20 msec; 64 × 64 matrix; 1.5 × 1.5 × 1.5 mm voxels; 35 contiguous slices. Slices were horizontal and covered the entire brain. In a separate session, a higher resolution anatomical scan (1.0 × 1.0 ×1.0 mm) was obtained using a small volume coil (a commercial GE “knee” coil) while the monkey was anesthetized with Ketamine and Xylazine. For the anatomical scan in figure 6 we used the same coil as for the functional scans and the following scan parameters: 3-D Fast Spoiled Grass Sequence with Inversion Recovery Preparation (IRFSPGR), Echo Time (TE) = 3.4 msec; 128 × 128 matrix; 0.5 × 0.5 × 1 mm voxels; coronal slices.

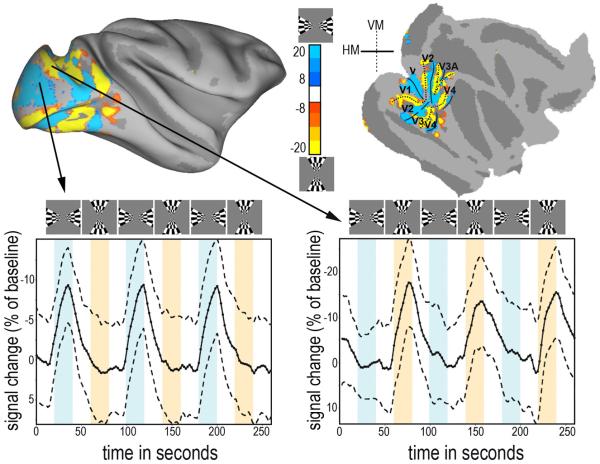

Figure 5.

Semi-inflated (top-left) and flattened (top-right) brain maps showing significant activation in response to horizontal (red) and vertical (blue) meridian stimuli viewed by an alert monkey non-invasively restrained by a vacuum helmet. (bottom) Time course of the mutually exclusive signal changes ± standard deviation in response to alternating horizontal (bottom-left) and vertical (bottom-right) meridians from two 4.5 × 4.5 × 4.5 mm ROIs as indicated calculated from 20 scans obtained in a single scanning session. Activations are both large and negative, compared to BOLD signal, because the monkey was injected with the iron oxide contrast agent Feraheme prior to scanning; the agent causes a decrease in the baseline and an inversion of signal (Leite et al. 2002). The functional activation maps were overlaid on the F99 atlas in Caret (Van Essen 2002); http://sumsdb.wustl.edu/sums/macaquemore.do. Areal borders were drawn by hand according to alternating meridians.

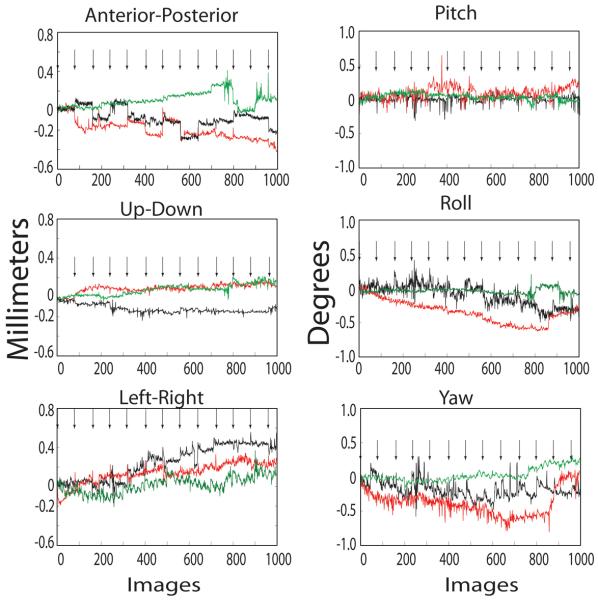

Figure 2.

Translation in mm (left) and rotation in degrees (right), normalized to the position at the beginning of each scan, during a single, typical, scan session for two vacuum-helmeted alert male monkeys (red & green traces) and a head-post restrained alert male monkey (black traces). X-axis is image number; one image was taken every 2 seconds. Most of the large position shifts occurred between scans; each scan onset is indicated by an arrow.

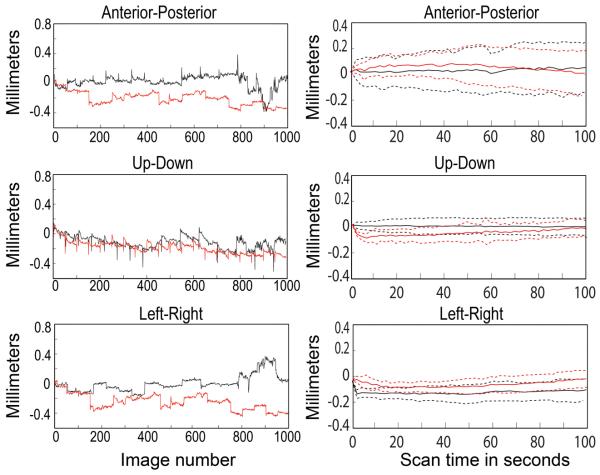

Figure 4.

Translational movements exhibited by one alert female monkey restrained using a helmet (red traces) or by a head-post (black traces). Left, movements during 20 consecutive 100 second (50 images) scans each during two different scan sessions, normalized to the position at the beginning of the session. Right, average movement, normalized to the position at the beginning of each scan, ± standard deviation for all 20 scans under each restraint condition.

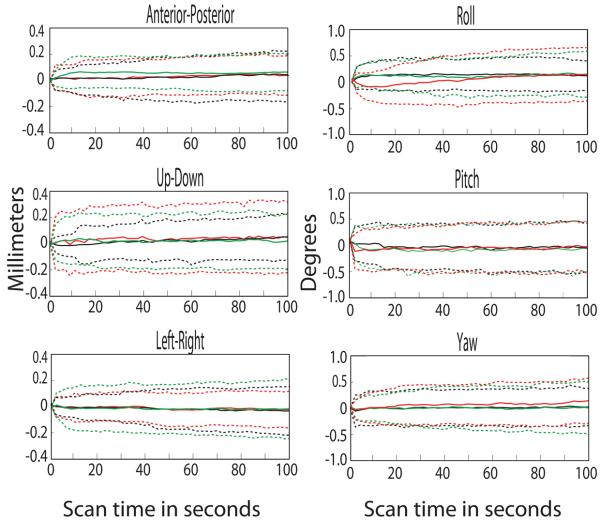

Figure 3.

Average brain movement, normalized to the position at the beginning of each scan, over the first 100 seconds of each scan for three alert monkeys ± standard deviation, averaged over 200 scans; for the two helmeted male monkeys in red & green and the head-post restrained male monkey in black.

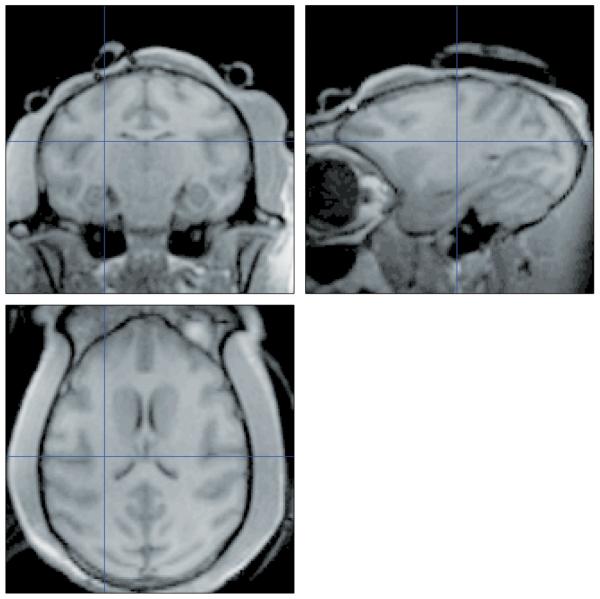

Figure 6.

Anatomical scans for monkey F1obtained during one 4 minute anatomical scan using the same helmet and coil as was used for the functional imaging. The section plane was coronal, so any changes in position during the scan should result in blurring or shifts in position between anterior and posterior sections, yet no difference in resolution is apparent between the coronal and the horizontal or sagittal reconstructions.

Visual Stimuli

Visual stimuli were projected onto a screen at the end of the bore, 57 cm from the monkey's eyes. The stimuli consisted of pairs of black and white checkerboard 45° wedges flickering in counterphase at 2Hz, with a central fixation spot, on a black background, one pair centered on the horizontal meridian and the other on the vertical meridian. The vertical wedges extended 10° above and below the fixation spot; the horizontal wedges extended 10° to the left and right of fixation. The checks subtended 0.2° of visual angle in the center of the display and increased exponentially in size to 5° in the periphery. Each scan lasted 160 seconds and consisted of 20-second blocks of vertical or horizontal meridian stimuli, presented alternately, separated by 20 second blocks of fixation spot alone.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using FS-FAST and Freesurfer (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu). Only scans in which the monkey fixated within 1° of the fixation spot for >80% of the duration of the scan were used for statistical analysis. To generate the significance maps, the data were motion-corrected, quadratically detrended, and smoothed with a Gaussian kernel of 2mm full-width-at-half-magnitude. We then calculated the mean and variance of the response in each voxel to each condition across the entire scan session. Then t-tests were used to compare activity during blocks of horizontal stimulation to blocks of vertical stimulation.

Movement Estimation

We used the motion correction algorithm in FS-FAST to estimate the movement of the monkeys' heads during each scan. The scanner computes images from the Fourier spectra of the RF signals. FS-FAST aligns each calculated image in a series with the first image in that series, and determines the difference in position of the two images; this is the `movement' we report. Since body movements can distort the magnetic field and thereby distort the images of the brain, both body and head movements can contribute to the calculated position, so the estimated movement is actually an upper estimate of the head movement.

All experiments were done in accordance with procedures approved by the Harvard Medical School Standing Committee on Animals.

RESULTS

The monkeys adapted to sitting still in a helmet in a horizontal chair in a mock scanner about as well as monkeys adapt to the same procedure using a conventional headpost. At first they pulled out of the suction and shifted their head position frequently, but after several days they settled down and sat quite still for up to an hour; after 2 months of training they would sit still for two or even three hours. Monkeys with headposts also require training to learn to sit calmly with their heads fixed. The monkeys could overcome the suction using much less force than would be required to break off a head post: The vacuum exerts at most 15 pounds of force total (2psi × 7 sq. in.). Using a strain gauge to pull on a ceramic screw (Thomas Recording, Giessen, Germany) threaded into an autopsy skull we determined that a single screw can be pulled out of a skull by 20 pounds of force. Therefore we would expect a headpost held on with 10 ceramic screws to be more than 10 times stronger than the vacuum helmet. However if the monkey pulls out of the helmet we lose one scan, which is significantly less of a problem than losing a headpost.

Comparision of calculated motion for headpost and helmet restrained monkeys

We first compare the head movements during scanning between two small male monkeys held by the vacuum helmet and a large male monkey fixed with a headpost. Figure 2 compares the rotation and translation movements for the vacuum-helmeted monkeys (red and green traces) and the headpost fixed monkey (black traces) during 12 consecutive scans in one typical scan session for each monkey. The figure plots the calculated position for 960 consecutive functional volumes, compared to the first volume in the session, for each monkey. The relative position was estimated from differences between corresponding slice images in consecutive volumes. Most of the movements occurred between scans (scan starts indicated by arrows) when we often paused and the monkey was not fixating and was not rewarded. The movements in all directions were comparable between the headposted animal and the helmeted animals.

Figure 3 compares the average movements during scanning for the same three monkeys, averaged over 200 160-second scans (9 sessions each) for the helmeted monkeys (red & green) and over 200 scans (10 sessions) for the head-posted monkey; these averaged sessions represent all the sessions for these 3 monkeys over a continuous period of several weeks for each monkey except that only scans in which the monkey fixated for more than 80% of the time were used to compute this average. None of the rotation or translation parameters were significantly different between the helmeted and the head-posted monkeys (two-tailed t-test; table 1); thus the head motion using the helmet method is comparable to the head movements of monkeys restrained using a conventional headpost.

Table 1.

Mean ± s.d. of all movement parameters for the 3 male monkeys averaged over the first 100 seconds of each of 200 scans obtained during 9 sessions for M1 & M2 and 10 sessions for M3. The mean ± s.d. of all movement parameters for the female monkey helmeted or headposted were averaged over 20 scans each, each scan 100 seconds long, obtained during 1 session with a headpost and 1 session with the helmet. Movements were calculated for each TR as the change in position of the brain from the position at the beginning of each scan.

| Helmeted Monkeys | Head Posted Monkeys | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2 | F1 | M3 | F1 | |

| Left – Right in mm |

−0.042 ±0.098 |

−0.016 ±0.082 |

0.067 ±0.037 |

−0.015 ±0.067 |

−0.053 ±0.038 |

| Up –Down in mm |

0.020 ±0.153 |

−0.016 ±0.126 |

0.018 ±0.038 |

0.041 ±0.232 |

0.060 ±0.046 |

|

Anterior –Posterior in mm |

0.053 ±0.083 |

0.048 ±0.089 |

0.050 ±0.056 |

0.026 ±0.105 |

−0.035 ±0.133 |

| Pitch in deg |

0.058 ±0.489 |

0.060 ±0.499 |

0.050 ±0.240 |

0.020 ±0.426 |

−0.054 ±0.450 |

| Yaw in deg |

0.021 ±0.465 |

0.017 ±0.42 |

−0.070 ±0.300 |

0.002 ±0.510 |

0.013 ±0.190 |

| Roll in deg |

0.067 ±0.36 |

0.032 ±0.414 |

0.046 ±0.150 |

0.055 ±0.354 |

0.020 ±0.180 |

Direct comparison of head-post vs helmet in a single monkey

The female monkey had a head-post and was scanned several times before the head-post broke off. After recovery she was trained to use the helmet and scanned using the helmet. Figure 4 shows a comparison of the her translational head movements during one scan session with the head-post (black traces) compared to one session with the helmet (red traces). The graphs on the left of figure 4 show the brain positions relative to the position at the beginning of the session for 20 consecutive 100-second scans, and the graphs on the right show the average movement during one scan, relative to the position at the beginning of each scan, averaged over all 20 scans. Thus the translational movements (and rotational movements, not shown) of this one monkey using the helmet are comparable to the same monkey's movement when restrained using a head-post.

Visual topographic maps for a vacuum-helmet fixed monkey

Since our goal was to hold a monkey's head stable enough to do functional MRI, we did a simple visual mapping experiment using the helmet with one of the small male monkeys. We used flickering checkerboard wedges to map the cortical representations of the horizontal and vertical meridians. The two stimuli evoked strong activation in mutually exclusive regions of visual cortex (Figure 5). Figure 5 top-left shows significant activations (p<10−8) for horizontal meridian activity (blue) and vertical meridian activity (yellow) on a semi-inflated brain. Figure 5 top-right shows the same activations on a flattened map. The time-course of the signal changes for horizontal (bottom-left) and vertical (bottom-right) meridians from the two 3 × 3 × 3 voxel ROIs (4.5 × 4.5 × 4.5 mm) indicated are shown at the bottom. The maps are comparable with earlier published maps of visual cortex (Fize et al. 2003).

Lastly we did anatomical scans of the alert female monkey restrained by the helmet while she fixated on the screen. The images were obtained at 0.5 × 0.5 × 1mm resolution, and the 1mm sections were in the coronal plane. Because the scan lasted 4 minutes any head motion would produce shifts in position of the coronal slices between the front and the back of the brain. We did not, however, observe any evidence in the horizontal or sagittal reconstructions of any such artifacts (figure 6).

DISCUSSION

Monkey fMRI has already proven to be a profoundly useful tool for comparing and enriching human brain imaging studies with the extensive non-human primate brain data. But functional imaging requires minimal subject motion, which poses a major problem for animal imaging. Usually a plastic headpost must be affixed to the skull using ceramic screws and dental acrylic. Headposts must be regularly cleaned to prevent infection and are difficult to implant and maintain in young monkeys who have very thin skulls. Our vacuum helmet method involves no invasive procedures and can be used even on quite young monkeys. The helmet technique works well for juvenile male macaques and for adult females. We have not tried the helmet on any large mature adult males. Most labs that do functional scanning on alert monkeys using the widely available horizontal bore MRI scanners prefer to use small animals who fit more easily in the bore. Labs that do scan large males usually use the less commonly available vertical-bore scanners, and in these labs the problems with acrylic (bone resorbtion and susceptibility artifacts) can be avoided by using custom-made PEEK implants held onto the skull with ceramic screws (Keleris et al, 2007). The long-term success of implants held in place with screws alone, without acrylic, is excellent for animals with thick skulls, like adult males (Adams et al., 2007), but, in our experience, is poor for younger animals who tend to have quite thin skulls.

The helmet technique allows us to scan monkeys without a surgically implanted headpost. The helmets cost about $300 each to manufacture, and designs for different sizes with different types of attaching posts are easily adapted from our original 3D model, which is available on request. Because the helmet is lined with two rings of soft silicone tubing, the fit does not need to be precise, and we found that one helmet design fits all four of the young (2.5-3.5 years old) male monkeys in our colony and two adult females. The helmet would not benefit those labs who want to combine fMRI with single-unit electrophysiology using an implanted chamber, but would be compatible with chronically implanted electrode arrays.

The overall movement of the head in the helmet-fixed monkeys was comparable to that of two head-post fixed monkeys, and in one monkey both methods were equally effective. Even when the head is immobilized, however, there is the additional problem that the monkey's body movement can cause distortions in the magnetic field which can cause artifacts and distortions in the reconstructed image (Goense et al. 2009); this problem is an issue no matter how the head is immobilized. The feasibility of our helmet approach to functional scanning was confirmed by a visual mapping experiment. We mapped the horizontal and vertical meridians in visual cortex and the maps were comparable to previously reported areal boundaries and representations of visual quadrants (Daniel and Whitteridge 1961; Van Essen et al. 1984; Felleman and Van Essen 1991; Fize et al. 2003).

In summary, we present a non-invasive method for holding a monkey's head still enough in a scanner to do functional MRI. The method requires extensive training, but the time required is not much greater than that necessary for training a head-posted monkey and the approach provides other benefits such as eliminating susceptibility artifacts from the acrylic and the surgery and maintenance required for chronic implants.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grant EY16187. The iron oxide contrast agent P904 was kindly provided by the Guerbet Group. We thank Joseph Mandeville, Winrich Freiwald, and Doris Tsao for advice.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Andersen AH, Zhang Z, Barber T, Rayens WS, Zhang J, Grondin R, Hardy P, Gerhardt GA, Gash DM. Functional MRI studies in awake rhesus monkeys: methodological and analytical strategies. J Neurosci Methods. 2002;118(2):141–152. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(02)00123-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel P, Whitteridge D. The representation of the visual field on the cerebral cortex in monkeys. Journal of Physiology. Journal of Physiology. 1961;159:203–221. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1961.sp006803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubowitz DJ, Chen DY, Atkinson DJ, Grieve KL, Gillikin B, Bradley WG, Andersen RA. Functional magnetic resonance imaging in macaque cortex. Neuroreport. 1998;9(10):2213–2218. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199807130-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand JB, Peeters R, Norman JF, Todd JT, Orban GA. Parietal regions processing visual 3D shape extracted from disparity. Neuroimage. 2009;46(4):1114–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felleman DJ, Van Essen DC. Distributed hierarchical processing in the primate cerebral cortex. Cereb Cortex. 1991;1(1):1–47. doi: 10.1093/cercor/1.1.1-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferris CF, Snowdon CT, King JA, Duong TQ, Ziegler TE, Ugurbil K, Ludwig R, Schultz-Darken NJ, Wu Z, Olson DP, Sullivan JM, Jr, Tannenbaum PL, Vaughan JT. Functional imaging of brain activity in conscious monkeys responding to sexually arousing cues. Neuroreport. 2001;12(10):2231–2236. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200107200-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferris CF, Snowdon CT, King JA, Sullivan JM, Jr., Ziegler TE, Olson DP, Schultz-Darken NJ, Tannenbaum PL, Ludwig R, Wu Z, Einspanier A, Vaughan JT, Duong TQ. Activation of neural pathways associated with sexual arousal in non-human primates. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2004;19(2):168–175. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fize D, Vanduffel W, Nelissen K, Denys K, Chef d'Hotel C, Faugeras O, Orban GA. The retinotopic organization of primate dorsal V4 and surrounding areas: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study in awake monkeys. J Neurosci. 2003;23(19):7395–7406. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-19-07395.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamlin PD, Ward MK, Bolding MS, Grossmann JK, Twieg DB. Developing functional magnetic resonance imaging techniques for alert macaque monkeys. Methods. 2006;38(3):210–220. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goense JB, Whittingstall K, Logothetis NK. Functional magnetic resonance imaging of awake behaving macaques. Methods. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2009.08.003. DOI: S1046-2023(09)00198-4 [pii] 10.1016/j.ymeth.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadj-Bouziane F, Bell AH, Knusten TA, Ungerleider LG, Tootell RB. Perception of emotional expressions is independent of face selectivity in monkey inferior temporal cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(14):5591–5596. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800489105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell LL, Hoffman JM, Votaw JR, Landrum AM, Jordan JF. An apparatus and behavioral training protocol to conduct positron emission tomography (PET) neuroimaging in conscious rhesus monkeys. J Neurosci Methods. 2001;106(2):161–169. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(01)00345-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph JE, Powell DK, Andersen AH, Bhatt RS, Dunlap MK, Foldes ST, Forman E, Hardy PA, Steinmetz NA, Zhang Z. fMRI in alert, behaving monkeys: an adaptation of the human infant familiarization novelty preference procedure. J Neurosci Methods. 2006;157(1):10–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keliris GA, Shmuel A, Ku SP, Pfeuffer J, Oeltermann A, Steudel T, Logothetis NK. Robust controlled functional MRI in alert monkeys at high magnetic field: effects of jaw and body movements. Neuroimage. 2007;36(3):550–570. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.02.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leite FP, Mandeville JB. Characterization of event-related designs using BOLD and IRON fMRI. Neuroimage. 2006;29(3):901–909. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leite FP, Tsao D, Vanduffel W, Fize D, Sasaki Y, Wald LL, Dale AM, Kwong KK, Orban GA, Rosen BR, Tootell RB, Mandeville JB. Repeated fMRI using iron oxide contrast agent in awake, behaving macaques at 3 Tesla. Neuroimage. 2002;16(2):283–294. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logothetis NK, Guggenberger H, Peled S, Pauls J. Functional imaging of the monkey brain. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2(6):555–562. doi: 10.1038/9210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier A, Wilke M, Aura C, Zhu C, Ye FQ, Leopold DA. Divergence of fMRI and neural signals in V1 during perceptual suppression in the awake monkey. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11(10):1193–1200. doi: 10.1038/nn.2173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peeters R, Simone L, Nelissen K, Fabbri-Destro M, Vanduffel W, Rizzolatti G, Orban GA. The representation of tool use in humans and monkeys: common and uniquely human features. J Neurosci. 2009;29(37):11523–11539. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2040-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanacci L, Reber P, Costanza J, Wong E, Buxton R, Zola S, Squire L, Albright T. fMRI of monkey visual cortex. Neuron. 1998;20(6):1051–1057. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80485-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao DY, Freiwald WA, Knutsen TA, Mandeville JB, Tootell RB. Faces and objects in macaque cerebral cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2003a;6(9):989–995. doi: 10.1038/nn1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao DY, Freiwald WA, Tootell RBH, Livingstone MS. A cortical region consisting entirely of face-selective cells. Science. 2006;311:670–674. doi: 10.1126/science.1119983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao DY, Vanduffel W, Sasaki Y, Fize D, Knutsen TA, Mandeville JB, Wald LL, Dale AM, Rosen BR, Van Essen DC, Livingstone MS, Orban GA, Tootell RB. Stereopsis activates V3A and caudal intraparietal areas in macaques and humans. Neuron. 2003b;39(3):555–568. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00459-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Essen DC. Windows on the brain: the emerging role of atlases and databases in neuroscience. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2002;12(5):574–579. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(02)00361-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Essen DC, Newsome WT, Maunsell JH. The visual field representation in striate cortex of the macaque monkey: asymmetries, anisotropies, and individual variability. Vision Research. 1984;24(5):429–448. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(84)90041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanduffel W, Fize D, Mandeville JB, Nelissen K, Van Hecke P, Rosen BR, Tootell RB, Orban GA. Visual motion processing investigated using contrast agent-enhanced fMRI in awake behaving monkeys. Neuron. 2001;32(4):565–577. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00502-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]