Abstract

Purpose

Our purpose was to evaluate the impact of post-mastectomy breast reconstruction on the timing of chemotherapy.

Methods

We included Stage I–III breast cancer patients from eight National Comprehensive Cancer Network institutions for whom guidelines recommended chemotherapy. Surgery type was categorized as breast conserving surgery (BCS), mastectomy alone, mastectomy with immediate reconstruction (M+IR), or mastectomy with delayed reconstruction (M+DR). A Cox regression analysis was used to assess the association between surgery type and timing of chemotherapy initiation.

Results

Of the 3,643 patients, only 5.1% received it ≥ 8 weeks from surgery. In the multivariate analysis, higher stage, Caucasian and Hispanic race/ethnicity, lower body-mass index and absence of comorbid conditions were all significantly associated with earlier time to chemotherapy. There was also significant interaction between age, surgery and chemotherapy delivery. Among women <60, time to chemotherapy was shorter for all surgery types compared to M+IR (statistical significant for all surgery types in the youngest age group and for BCS in women 40 – <50 years old). In contrast, among women ≥60, time to chemotherapy was shorter among women receiving M+IR or M+DR compared with those undergoing BCS or mastectomy alone, a difference that was statistically significant for the M+IR vs. BCS comparison.

Conclusions

Immediate post-mastectomy breast reconstruction does not appear to lead to omission of chemotherapy, but it is associated with a modest, but statistically significant, delay in initiating treatment. For most, it is unlikely that this delay has any clinical significance.

Keywords: breast reconstruction, breast cancer, chemotherapy, NCCN

Post-mastectomy breast reconstruction is an integral part of breast cancer care. Breast reconstruction, especially when performed at the time of the mastectomy, has been associated with improved psychosocial well-being and high levels of patient satisfaction.1–5 In particular, reconstruction can have a positive influence on women’s body image, sexuality, and social well-being, thus having a long-term impact in the cancer survivorship period.6 However, less than 20% of women receive reconstruction at the time of the mastectomy.7 There is also wide geographic variation in the use of reconstruction, raising the concern that there may be unmet need and access barriers to reconstructive surgery.7, 8

One barrier to the use of immediate breast reconstruction – that is reconstruction performed at the time of mastectomy – is the concern that complications of reconstruction may unduly delay the initiation of systemic chemotherapy or lead to its omission altogether.9 Adjuvant chemotherapy in appropriately selected breast cancer patients is a life-saving intervention. Delay in initiating adjuvant treatment may compromise its effectiveness, and omitting it will have even more serious consequences.10

Little is known about the impact of immediate breast reconstruction on the administration of adjuvant chemotherapy. Immediate breast reconstruction offers better aesthetic results, cushions the psychological impact of the breast amputation, and decreases healthcare costs by decreasing the number of operations the patient requires.3, 9, 11, 12 However, immediate reconstruction is associated with higher surgical complication rates compared to those performed after the mastectomy,13 which could delay the timing of chemotherapy delivery, and might lead some patients to forego chemotherapy altogether. Previous studies have not found an association between immediate breast reconstruction and delayed chemotherapy;14–21 however, these have been small, single-center studies with limited ability to generalize to other healthcare settings due to the high variability of surgical techniques and patient-level factors across medical centers. Furthermore, these studies have looked exclusively at the timing of chemotherapy among treated patients, so they could not determine whether reconstruction had an effect on the use of adjuvant therapy.

We sought to examine the impact of breast reconstruction on the delivery of chemotherapy using a large, multi-center cohort of patients. Specifically, we wanted to 1) describe the effect of the primary surgery type on the use and timing of adjuvant therapy, controlling for patient factors, and 2) identify factors associated with a significant delay or omission of adjuvant chemotherapy.

Methods

Study Population

Our study population consisted of 3,643 women with Stage I–III unilateral breast cancer who were treated at one of the eight participating National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) institutions between July 1, 1997 and December 31, 2003 for whom NCCN guidelines recommended adjuvant chemotherapy. Patients were eligible for this analysis if they received their definitive surgery at the NCCN institution and continued to receive their care there for at least one year after first presentation. The data base includes information on receipt of chemotherapy regardless of the administering institution for patients who continue to be seen in the NCCN center. We limited the sample to patients for whom the version of the NCCN guidelines in effect at the time of their diagnosis recommended adjuvant chemotherapy.22, 23 This was done for two reasons. First, we were not interested in capturing information on whether type of surgery resulted in delayed initiation of a treatment that was not indicated. Second, defining our cohort by clinical indication rather than chemotherapy administration allowed us to examine the effect of surgery type not just on the timing but also on the use of adjuvant chemotherapy. Patients who received either 1) neoadjuvant systemic or radiation therapy (N = 635), 2) radiation therapy prior to initiation of adjuvant therapy (N = 34) or 3) breast reconstruction more than a day after completion of their primary surgery but before the initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy (N = 8) were not eligible for this analysis since these patterns of care would confound an analysis of the relationship between primary surgery type and time to initiation of adjuvant treatment. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from each institution.

Measures

All variables used in the analysis were obtained from the NCCN Breast Cancer Outcomes Project Database. Definitive surgery was assigned after considering all breast-directed surgical procedures and was classified as BCS, mastectomy only, mastectomy with immediate breast reconstruction (M+IR), or mastectomy with delayed breast reconstruction (M+DR). Reconstruction was considered “immediate” if it was either started or completed on the same day as the mastectomy, and “delayed” otherwise.

Other variables in the analysis included: type of reconstructive surgery (implant, pedicle transverse rectus abdominus myocutaneous flap (TRAM), free TRAM requiring microvascular surgery, other rotational flap and other free flap); NCCN institution; race/ethnicity (Caucasian, Hispanic, African-American, other); median household income (< $35,426, $35,426 - < $44,639, $44,639 - <$58,844, $58,844 - $159,538, unknown); age at diagnosis; body mass index (BMI) (< 25 kg/m2, 25–35 kg/m2, >35 kg/m2, unknown); AJCC stage at diagnosis (I, II, III); tumor size (≤2 cm, >2–5 cm, >5 cm, unknown); number of positive lymph nodes (0, 1–3, 4–9, ≥10, unknown); Charlson comorbidity score (0,1, ≥2); NCCN breast cancer guideline that the patient was eligible for based on clinical characteristics; and participation in an adjuvant therapy clinical trial.

Adjuvant chemotherapy was defined as systemic cancer-directed therapy given after completion of definitive surgery and prior to any recurrence. Time to adjuvant chemotherapy was the interval from the last definitive surgical procedure to the first dose of adjuvant chemotherapy. For the descriptive analyses, time to chemotherapy was reported as a categorical variable (<8 weeks, ≥8 weeks, and no chemotherapy). In the logistic model, the outcome variable was defined as adjuvant chemotherapy initiated prior to recurrence. In the time to event multivariable analysis, time to chemotherapy from definitive surgery was analyzed as a continuous variable.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analyses were conducted with time to treatment as a categorical variable. For the time to event analysis, we first assessed the association of other variables with the continuous time to chemotherapy variable in univariate Cox regression. Based on variables with p < 0.20, we then constructed a multivariable Cox proportional hazards model to assess the impact of type of definitive surgery on chemotherapy administration, controlling for other factors. In the results of this analysis, a hazard ratio (HR) > 1 for a particular group indicates that chemotherapy was initiated earlier in that group compared with the reference category group, while a HR < 1 indicates that treatment was delayed compared with the reference category. The final multivariable model included only those terms significant at p < 0.05, including significant interactions terms. All analyses were conducted using SAS V9.1.3 software. All modeling reports 95% confidence intervals (CI) and two-sided p-values. The assumption of the proportional hazards was tested and met.

Results

Table 1 displays the study sample characteristics by receipt of chemotherapy grouped as: early (< 8 weeks), late (≥ 8 weeks), or no chemotherapy. The majority of patients (59.2%) had BCS, 21.7% had mastectomy only, 16.4% had M+IR and 2.7% had M+DR. Of the 696 patients who had mastectomy with either immediate or delayed reconstruction, 49.7% had an implant, 22.1% had a free TRAM flap, and 18.5% had a pedicle TRAM flap. Of the 3,643 breast cancer patients for whom NCCN guidelines recommended adjuvant chemotherapy, 67.4% received it early (within 8 weeks), 5.1% received it late (≥ 8 weeks) and 27.5% did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy at any time point. Overall, 98% of patients who received chemotherapy started the treatment within 12 weeks postoperatively.

Table 1.

Study Sample Characteristics (N=3,643)*

| Time from Definitive Surgery to Chemotherapy | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early** (N = 2,454) | Late^ (N = 186) | No Chemotherapy (N = 1,003) | ||||

| N | (Row %) | N | (Row %) | N | (Row %) | |

| Type of Surgery | ||||||

| Mastectomy with Immediate Reconstruction | 446 | (74.8) | 53 | (8.9) | 97 | (16.3) |

| Breast Conserving Surgery | 1387 | (64.4) | 91 | (4.2) | 677 | (31.4) |

| Mastectomy alone | 534 | (67.4) | 39 | (4.9) | 219 | (27.7) |

| Mastectomy with Delayed Reconstruction | 87 | (87.0) | 3 | (3.0) | 10 | (10.0) |

| Patient Age at Diagnosis | ||||||

| <40 | 402 | (89.7) | 22 | (4.9) | 24 | (5.4) |

| 40–49 | 901 | (83.3) | 58 | (5.4) | 123 | (11.4) |

| 50–59 | 725 | (74.4) | 53 | (5.4) | 197 | (20.2) |

| ≥60 | 426 | (37.4) | 53 | (4.7) | 659 | (57.9) |

| Stage at Diagnosis | ||||||

| Stage I | 659 | (49.1) | 53 | (3.9) | 630 | (46.9) |

| Stage II | 1730 | (77.9) | 127 | (5.7) | 365 | (16.4) |

| Stage III | 65 | (82.3) | 6 | (7.6) | 8 | (10.1) |

| Path Tumor Size | ||||||

| ≤2 cm | 1348 | (60.6) | 103 | (4.6) | 773 | (34.8) |

| >2–5 cm | 981 | (78.4) | 72 | (5.8) | 198 | (15.8) |

| >5 cm | 84 | (80.0) | 7 | (6.7) | 14 | (13.3) |

| Unknown/missing | 41 | (65.1) | 4 | (6.3) | 18 | (28.6) |

| Number of Positive Nodes | ||||||

| 0 | 1106 | (57.4) | 88 | (4.6) | 734 | (38.1) |

| 1–3 | 1019 | (78.6) | 70 | (5.4) | 208 | (16.0) |

| 4–9 | 226 | (83.4) | 21 | (7.7) | 24 | (8.9) |

| 10 or more | 99 | (86.1) | 7 | (6.1) | 9 | (7.8) |

| N/A | 4 | (12.5) | 0 | (0.0) | 28 | (87.5) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| Caucasian | 2052 | (67.0) | 155 | (5.1) | 854 | (27.9) |

| Hispanic | 138 | (71.1) | 13 | (6.7) | 43 | (22.2) |

| African-American | 176 | (66.7) | 13 | (4.9) | 75 | (28.4) |

| Other | 88 | (71.0) | 5 | (4.0) | 31 | (25.0) |

| Median Household Income (quartiles) | ||||||

| Q1: $0–<$35,426 | 562 | (63.9) | 50 | (5.7) | 267 | (30.4) |

| Q2: $35,426–<$44,639 | 582 | (66.2) | 58 | (6.6) | 239 | (27.2) |

| Q3: $44,639–<$58,844 | 588 | (66.9) | 47 | (5.3) | 244 | (27.8) |

| Q4: $58,844–$159,538 | 632 | (71.8) | 27 | (3.1) | 221 | (25.1) |

| Foreigner | 26 | (81.3) | 2 | (6.3) | 4 | (12.5) |

| Unknown | 64 | (68.1) | 2 | (2.1) | 28 | (29.8) |

| Comorbidity Score | ||||||

| 0 | 2091 | (71.1) | 148 | (5.0) | 701 | (23.8) |

| 1 | 265 | (54.9) | 28 | (5.8) | 190 | (39.3) |

| ≥2 | 98 | (44.5) | 10 | (4.5) | 112 | (50.9) |

| Body Mass Index | ||||||

| < 25 kg/m2 | 1050 | (72.6) | 49 | (3.4) | 348 | (24.0) |

| 25–35 kg/m2 | 1036 | (64.4) | 90 | (5.6) | 483 | (30.0) |

| >35 kg/m2 | 252 | (63.2) | 36 | (9.0) | 111 | (27.8) |

| Unknown | 116 | (61.7) | 11 | (5.9) | 61 | (32.4) |

| Type of Reconstruction | ||||||

| No Reconstruction | 1921 | (65.2) | 130 | (4.4) | 896 | (30.4) |

| Implant | 264 | (76.3) | 20 | (5.8) | 62 | (17.9) |

| Pedicle TRAM flap | 105 | (81.4) | 17 | (13.2) | 7 | (5.4) |

| Free TRAM flap | 115 | (74.7) | 12 | (7.8) | 27 | (17.5) |

| Other rotational flap | 37 | (72.5) | 5 | (9.8) | 9 | (17.6) |

| Other free flap | 12 | (75.0) | 2 | (12.5) | 2 | (12.5) |

| Institution | ||||||

| A | 111 | (66.5) | 11 | (6.6) | 45 | (26.9) |

| B | 443 | (73.2) | 24 | (4.0) | 138 | (22.8) |

| C | 259 | (65.6) | 40 | (10.1) | 96 | (24.3) |

| D | 415 | (62.5) | 30 | (4.5) | 219 | (33.0) |

| E | 263 | (63.2) | 18 | (4.3) | 135 | (32.5) |

| F | 168 | (76.7) | 3 | (1.4) | 48 | (21.9) |

| G | 386 | (70.1) | 32 | (5.8) | 133 | (24.1) |

| H | 409 | (65.3) | 28 | (4.5) | 189 | (30.2) |

| Guideline | ||||||

| Stage I/II node negative, Tubular/Colloid, Tumor Size >=3 cm | 3 | (33.3) | 0 | (0.0) | 6 | (66.7) |

| Stage I/II node negative, HR negative, Tumor Size > 1 cm | 427 | (78.3) | 38 | (7.0) | 80 | (14.7) |

| Stage I/II node negative, HR positive, Tumor Size >1–3 cm | 602 | (46.7) | 41 | (3.2) | 645 | (50.1) |

| Stage I/II node negative, HR positive, Tumor Size >3 cm | 78 | (67.2) | 9 | (7.8) | 29 | (25.0) |

| Stage I/II node positive, HR negative | 335 | (85.7) | 28 | (7.2) | 28 | (7.2) |

| Stage I/II node positive, HR positive | 944 | (77.7) | 64 | (5.3) | 207 | (17.0) |

| Stage IIIA with T3N1 | 65 | (82.3) | 6 | (7.6) | 8 | (10.1) |

Newly diagnosed Stage I, II, and III BCA patients who presented at NCCN institution from July 30, 1997 to December 31, 2003, received definitive surgery, and were recommended to receive adjuvant chemotherapy based on NCCN guidelines (v. 1997 – v. 2003).

Early delivery of chemotherapy is receipt less than 8 weeks from definitive surgery

Late delivery of chemotherapy is receipt 8 weeks or more from definitive surgery

In a logistic model controlling for age, stage, race and ethnicity, income, comorbidity, BMI, NCCN institution, and NCCN guideline, there was no effect of surgery type on use of adjuvant chemotherapy (p=0.33). Based on an a priori hypothesis that the effect might differ by patient age, we also did an analysis to assess for an interaction between age and surgery type and found no association.

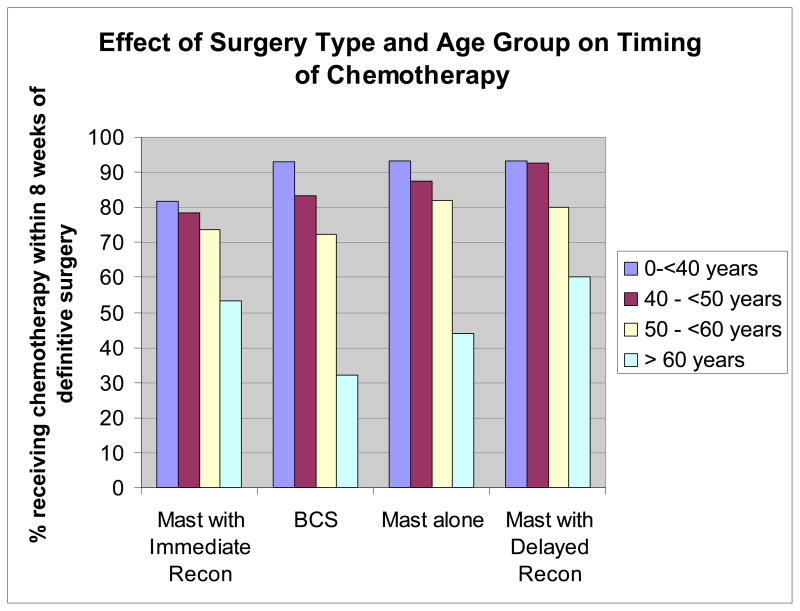

As shown in Figure 1, the relationship between surgery type and time to initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy varied by patient age. For patients younger than 50, the proportion of patients initiating chemotherapy within 8 weeks was lower for M+IR than for any of the other treatment approaches. In contrast, among patients over age 60, patients who opted for mastectomy with either immediate or delayed reconstruction were more likely to receive chemotherapy within 8 weeks.

Figure 1.

Proportion of Patients who Received Chemotherapy within 8 Weeks of Definitive Surgery by Patient Age and Type of Surgery

Because of the marked difference in the relationship between surgery type and chemotherapy by patient age, the results of univariate analyses are difficult to interpret. Therefore, in Table 2, we present the multivariable results of the time to chemotherapy analysis, including interactions between age and surgery type. In this analysis, a hazard ratio >1 indicates that patients in that category were more likely to receive chemotherapy early than patients in the reference category. As shown in the table, higher stage, Caucasian and Hispanic race versus African American, lower BMI and absence of comorbid conditions were all associated with earlier time to chemotherapy. The effect of surgery type depended on age. Controlling for all other factors, among women under age 60, time to chemotherapy was shorter for all surgery types compared to M+IR. These differences reached statistical significance for all surgery types in the youngest age group, and for BCS in women 40 – <50 years of age. In contrast, among women 60 years old or older, time to chemotherapy was shorter among women receiving reconstruction (immediate or delayed) compared with those undergoing BCS or mastectomy alone, a difference that was statistically significant for the M_IR vs. BCS comparison.

Table 2.

Multivariable Results of Patient and Clinical Factors Significantly Associated with the Timing of Post-Operative Adjuvant Chemotherapy (N = 3,643)

| Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main Effects Terms | |||

| Stage at Diagnosis | <.0001 | ||

| Stage I | Ref | ||

| Stage II | 1.76 | 1.55 – 2.01 | |

| Stage III | 1.98 | 1.50 – 2.63 | |

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.0347 | ||

| Caucasian | Ref | ||

| Hispanic | 1.02 | 0.85 – 1.21 | |

| African-American | 0.80 | 0.68 – 0.93 | |

| Other | 0.98 | 0.79 – 1.21 | |

| Median Household Income (quartiles) | 0.0110 | ||

| Q1: $0–<$35,426 | Ref | ||

| Q2: $35,426–<$44,639 | 1.03 | 0.92 – 1.15 | |

| Q3: $44,639–<$58,844 | 1.03 | 0.91 – 1.16 | |

| Q4: $58,844–$159,538 | 1.11 | 0.98 – 1.25 | |

| Foreigner | 2.02 | 1.36 – 3.01 | |

| Unknown | 1.15 | 0.88 – 1.48 | |

| Comorbidity Score | <.0001 | ||

| 0 | Ref | ||

| 1 | 0.94 | 0.83 – 1.06 | |

| ≥2 | 0.59 | 0.48 – 0.72 | |

| Body Mass Index | 0.0119 | ||

| < 25 kg/m2 | Ref | ||

| 25–35 kg/m2 | 0.90 | 0.83 – 0.98 | |

| >35 kg/m2 | 0.83 | 0.72 – 0.94 | |

| Unknown | 0.85 | 0.71 – 1.04 | |

| NCCN Institution | <.0001 | ||

| E | Ref | ||

| A | 0.95 | 0.76 – 1.19 | |

| B | 1.10 | 0.94 – 1.29 | |

| C | 0.95 | 0.80 – 1.13 | |

| D | 1.01 | 0.86 – 1.17 | |

| F | 1.10 | 0.94 – 1.28 | |

| G | 1.18 | 1.01 – 1.38 | |

| H | 1.79 | 1.46 – 2.19 | |

| Guideline | <.0001 | ||

| Stage I/II node positive, HR positive | Ref | ||

| Stage I/II node negative, Tubular/Colloid, Tumor Size >=3 cm | 0.34 | 0.11 – 1.06 | |

| Stage I/II node negative, HR negative, Tumor Size > 1 cm | 1.20 | 1.05 – 1.36 | |

| Stage I/II node negative, HR positive, Tumor Size >1–3 cm | 0.64 | 0.56 – 0.74 | |

| Stage I/II node negative, HR positive, Tumor Size >3 cm | 0.76 | 0.61 – 0.95 | |

| Stage I/II node positive, HR negative | 1.18 | 1.04 – 1.33 | |

| Stage IIIA with T3N1 | LC* | LC* | |

| Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interaction Terms | ||||

| Type of Definitive Surgery by Age at Diagnosis | 0.0009 | |||

| 0-<40 years | Mastectomy with Immediate Reconstruction | Ref | ||

| Breast Conserving Surgery | 1.79 | 1.43 – 2.25 | ||

| Mastectomy alone | 1.53 | 1.13 – 2.06 | ||

| Mastectomy with Delayed Reconstruction | 2.27 | 1.49 – 3.46 | ||

| 40 – <50 years | Mastectomy with Immediate Reconstruction | Ref | ||

| Breast Conserving Surgery | 1.38 | 1.18 – 1.63 | ||

| Mastectomy alone | 1.18 | 0.96 – 1.45 | ||

| Mastectomy with Delayed Reconstruction | 1.38 | 0.98 – 1.96 | ||

| 50–<60 years | Mastectomy with Immediate Reconstruction | Ref | ||

| Breast Conserving Surgery | 1.18 | 0.96 – 1.44 | ||

| Mastectomy alone | 1.22 | 0.96 – 1.55 | ||

| Mastectomy with Delayed Reconstruction | 1.44 | 0.88 – 2.34 | ||

| ≥ 60 years | Mastectomy with Immediate Reconstruction | Ref | ||

| Breast Conserving Surgery | 0.70 | 0.50 – 0.97 | ||

| Mastectomy alone | 0.79 | 0.56 – 1.11 | ||

| Mastectomy with Delayed Reconstruction | 1.50 | 0.64 – 3.54 | ||

Linear combination of Stage III did not fit in the multivariate model.

A hazard ratio (HR) > 1 for a particular group indicates that chemotherapy was initiated earlier in that group compared with the reference category group, while a HR < 1 indicates that treatment was delayed compared with the reference category.

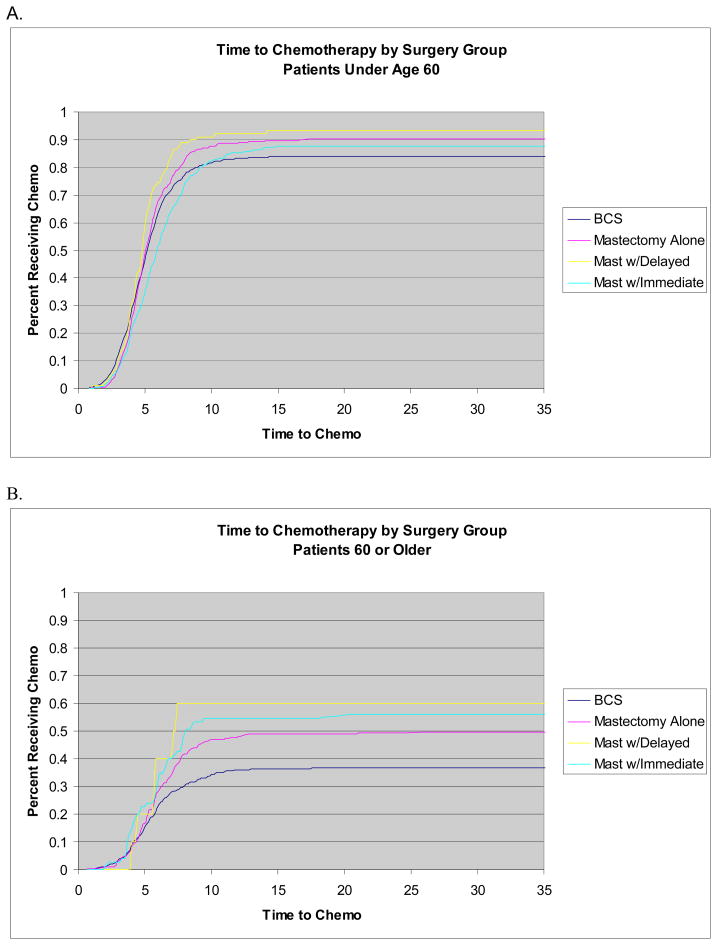

Figure 2 shows the time to treatment for the entire patient sample by surgery type among women less than 60 years of age (Panel A) and age 60 or older (Panel B). Because of the similarity in the multivariable results across age strata below age 60, we aggregated those patients for this analysis. Among women less than 60, the median time to initiation of treatment was 5.29 weeks for BCS, 5.14 weeks for mastectomy alone, 4.86 weeks for M+DR, and 6.00 weeks for M+IR. Among women 60 and older, fewer than half the women who received BCS or mastectomy alone received chemotherapy so there was no median time to treatment initiation for those groups. Median time to treatment for women who received M+DR was 7.14 weeks compared with 8.14 weeks among women treated with M+IR. Among the subset of patients who received chemotherapy, the median time to chemotherapy for those <60 years and >60 was: 4.86 and 5.43 weeks for BCS; 5.00 and 5.86 weeks for mastectomy alone; 5.57 and 5.93 weeks for M+IR; 4.79 and 5.79 weeks for M+DR, respectively.

Figure 2.

Time to chemotherapy by surgery group for patients under age 60 (Panel A) and 60 or older (Panel B). The sample population for <60 years included 1,454 BCS, 440 mastectomy alone, 521 mastectomy with immediate reconstruction and 90 with mastectomy and delayed reconstruction. The sample population for ≥60 years included 701 BCS, 352 mastectomy alone, 75 mastectomy with immediate reconstruction and 10 mastectomy with delayed reconstruction.

Discussion

In this large, multi-center cohort of breast cancer patients, we found that immediate reconstruction did not increase the chance that adjuvant chemotherapy would be omitted in women likely to benefit from it. Immediate reconstruction was associated with an increase in the time to chemotherapy initiation compared with all other treatment strategies among women less than 60 years of age, but the magnitude of the delay was quite modest. Among women less than 60 years of age, median time to chemotherapy after mastectomy with immediate reconstruction was 6.00 weeks compared to 5.29 weeks after BCS. In contrast, among women 60 years old or older, time to chemotherapy was shorter among women receiving reconstruction (immediate or delayed) compared with those undergoing BCS or mastectomy alone.

It is highly unlikely that a one week delay in the initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy that is otherwise administered within proven time frames impacts long-term survival. In all clinical trials demonstrating effectiveness of chemotherapy, treatment started within eight weeks of the last surgery. There are no data to show improved outcomes when chemotherapy is initiated within shorter times. The Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative group and the British Columbia Cancer Agency have found no difference in survival between patients given chemotherapy early, such as 3 weeks, compared to those that received treatment up to 12 weeks postoperatively.10, 24 At the extreme of starting chemotherapy before surgery (neoadjuvant), available data show no advantage of this early therapy compared to post-operative therapy started within eight weeks of surgery. However, delays greater than three months have been associated with diminished relapse-free survival and overall survival.10 In our series, 98% of breast cancer patients who received chemotherapy started the treatment within 12 weeks postoperatively across all medical centers and all surgical treatments.

Previous studies have not found immediate post-mastectomy breast reconstruction to delay the delivery of adjuvant chemotherapy.14–21 However, these studies have been limited by retrospective designs and small, single-center patient cohorts. More importantly, these studies defined their patient cohorts as those who received chemotherapy rather than whether chemotherapy was indicated. It is important to evaluate omission of treatment, along with delays in administration. By defining our study population by whether chemotherapy was indicated, rather than received, we were able to show that immediate breast reconstruction is not associated with any significant omission in chemotherapy treatment.

The aesthetic, psychological and financial benefits of immediate breast reconstruction are clear. However, support for this approach among clinicians caring for women with breast cancer could depend on their perceptions about whether it compromises optimal chemotherapy and thus survival.25 A recent survey of medical oncologists found that nearly 40% are concerned that immediate post-mastectomy breast reconstruction interferes with adjuvant oncologic therapy.26 Our results suggest that this concern is unwarranted regarding chemotherapy. Recommendations regarding immediate breast reconstruction may also be influenced by the likelihood that the patient will also need adjuvant post-mastectomy chest wall and nodal radiation. Radiation improves survival in certain subsets of women with positive nodes.27 Reconstruction may affect the technical delivery of radiation,28 and radiation may adversely affect the cosmetic result of reconstruction.29 Though there is no uniform consensus, this concern leads some oncologists to recommend delayed reconstruction in women who are likely to receive radiation. The NCCN guidelines state that delayed reconstruction is preferred in this situation (a Category 2B recommendation). This may account for the documented lower use of immediate breast reconstruction in NCCN centers in those women with more advanced cancer stage and larger tumors.30

We found an interesting interaction between patient age, type of surgical treatment and delivery of chemotherapy. Our results are consistent with other studies showing that older patients are less likely to receive chemotherapy and also less likely to receive immediate breast reconstruction.31 However, our data suggest that older women who undergo immediate breast reconstruction may be more likely to receive adjuvant chemotherapy. These results did not reach statistical significance in multivariable modeling, perhaps because of small sample size. But if confirmed in larger studies, this would suggest that immediate breast reconstruction in those ≥ 60 years of age could be a marker for a more aggressive treatment philosophy by that patient, or overall more vigorous health as perceived by their providers. Our results offer additional support of the safety of breast reconstruction in well-selected older women.13

We found that in addition to age, other clinical and socio-demographic characteristics place patients at increased risk for delayed chemotherapy. From a clinical standpoint, post-surgical wounds and infections often are the primary reasons delaying chemotherapy. There has been well-established evidence linking patient obesity with postoperative complications.13, 32 Our data show a significant association between obesity and high comorbidity score with delayed chemotherapy delivery. Quality efforts should be aimed at improving patient selection for elective breast reconstructive surgery. Surgeons should be encouraged to delay breast reconstruction in these high risk populations; in particular, those with a BMI > 35 kg/m2 and a comorbidity score ≥ 2.

Patient race was also a significant predictor of delayed chemotherapy in our study. The reasons may be multifactorial. Compared to Caucasian women, African-Americans experience the greatest delay in breast cancer diagnosis,33 present with more aggressive disease,34 have limited knowledge regarding their reconstructive options35 and are significantly less likely to receive reconstruction at the time of the mastectomy.7, 8 We carefully controlled for clinical characteristics in our analysis by including not only stage, but also NCCN guideline, a more granular measure of factors relevant to clinical decision making, and used a standardized measure of comorbidity. Therefore, non-clinical factors may also be playing a role. A prior analysis of NCCN data found no effect of race on reconstruction after mastectomy,36 suggesting that the factors that influence time to chemotherapy may differ from those that influence treatment choice

Limitations

Ours is an observational study not a controlled randomized trial, so we cannot rule out unaccounted for factors that could be associated with both treatment choice and timing of chemotherapy delivery. More importantly, our outcomes reflect the experience of high volume cancer centers and may not reflect practices in the community setting. Our database only captures information on margins from the definitive pathology report, so we cannot report on the frequency with which margins were thought to be negative intra-operatively, but reported as positive after definitive review. While this is a theoretical disadvantage of immediate reconstruction, it would not be expected to increase the time to initiation of chemotherapy. We also do not have information on surgical complications so we cannot comment on how those factors affected treatment timing. Lastly, we have not yet followed these patients long enough to assess the impact of delays in chemotherapy on long-term survival or recurrence.

Clinical Implications

Immediate post-mastectomy breast reconstruction does not appear to lead to omission of adjuvant chemotherapy, but it is associated with a very modest, but statistically significant, delay in initiating treatment. For the typical patient, it is unlikely that this delay has any clinical significance. However, for patients who are higher risk of delay on the basis of socio-demographic and clinical characteristics, the additional delay associated with immediate reconstruction should be considered. These higher risk groups would include patients with lower stage disease, morbid obesity, or serious comorbid conditions, as well as African Americans. Future efforts should be aimed at educating healthcare providers about these vulnerable populations and implementing strategies to either delay reconstruction in these groups or to facilitate the processes of care through: a) improved communication between physicians through multi-disciplinary cancer clinics and b) aggressive treatment of post-operative complications to expedite recovery.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Support: This work was supported by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and P50 CA89393 from the National Cancer Institute to Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

Statement of Financial Interest: The authors have no financial or commercial interests related to this research.

References

- 1.Dean C, Chetty U, Forrest AP. Effects of immediate breast reconstruction on psychosocial morbidity after mastectomy. Lancet. 1983;320:459–462. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)91452-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenqvist S, Sandelin K, Wickman M. Patients’ psychological and cosmetic experience after immediate breast reconstruction. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1996;22(3):262–6. doi: 10.1016/s0748-7983(96)80015-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stevens LA, McGrath MH, Druss RG, Kister S, Gump F, Forde K. The psychological impact of immediate breast reconstruction for women with early breast cancer. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 1984;73:619. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198404000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilkins EG, Cederna PS, Lowery JC, Davis J, Kim H, et al. Prospective analysis of psychosocial outcomes in breast reconstruction: one-year postoperative results from the Michigan Breast Reconstruction Outcome Study. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2000;106:1014–25. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200010000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alderman AK, Wilkins E, Lowery J, et al. Determinants of patient satisfaction in post-mastectomy breast reconstruction. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2000;106:769–776. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200009040-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atisha D, Alderman AK, Lowery JC, et al. Prospective analysis of long-term psychosocial outcomes in breast reconstruction: two-year postoperative results from the Michigan Breast Reconstruction Outcomes Study. Ann Surg. 2008;247(6):1019–28. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181728a5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alderman AK, Wei Y, Birkmeyer JD. Use of breast reconstruction after mastectomy following the Women’s Health and Cancer Rights Act. JAMA. 2006;295(4):387–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.4.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alderman AK, McMahon L, Wilkins EG. The national utilization of immediate and early delayed breast reconstruction & the impact of sociodemographic factors. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2003;11:695–703. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000041438.50018.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rainsbury DM. Recent trends in breast reconstruction. Hosp Med. 1999;60(7):486–90. doi: 10.12968/hosp.1999.60.7.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lohrisch C, Paltiel C, Gelmon K, et al. Impact on survival of time from definitive surgery to initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy for early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(30):4888–94. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.6089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noone RB, Murphy JB, Spear SL, Little JW., 3rd A 6-year experience with immediate reconstruction after mastectomy for cancer. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;76(2):258–69. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198508000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wellisch DK, Schain WS, Noone RB, Little JW., 3rd Psychosocial correlates of immediate versus delayed reconstruction of the breast. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;76(5):713–8. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198511000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alderman AK, Wilkins E, Kim M, Lowery J. Complications in post-mastectomy breast reconstruction: two year results of the Michigan breast reconstruction outcome study. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2002;109:2265–2274. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200206000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rey P, Martinelli G, Petit JY, et al. Immediate breast reconstruction and high-dose chemotherapy. Ann Plast Surg. 2005;55(3):250–4. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000174762.36678.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taylor CW, Kumar S. The effect of immediate breast reconstruction on adjuvant chemotherapy. Breast. 2005;14(1):18–21. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caffo O, Cazzolli D, Scalet A, et al. Concurrent adjuvant chemotherapy and immediate breast reconstruction with skin expanders after mastectomy for breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2000;60(3):267–75. doi: 10.1023/a:1006401403249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Allweis TM, Boisvert ME, Otero SE, et al. Immediate reconstruction after mastectomy for breast cancer does not prolong the time to starting adjuvant chemotherapy. Am J Surg. 2002;183(3):218–21. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(02)00793-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson CR, Brown IM, Weiller-Mithoff E, et al. Immediate breast reconstruction does not lead to a delay in the delivery of adjuvant chemotherapy. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2004;30(6):624–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yeh KA, Lyle G, Wei JP, Sherry R. Immediate breast reconstruction in breast cancer: morbidity and outcome. Am Surg. 1998;64(12):1195–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gouy S, Rouzier R, Missana MC, et al. Immediate reconstruction after neoadjuvant chemotherapy: effect on adjuvant treatment starting and survival. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12(2):161–6. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mortenson MM, Schneider PD, Khatri VP, et al. Immediate breast reconstruction after mastectomy increases wound complications: however, initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy is not delayed. Arch Surg. 2004;139(9):988–91. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.9.988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Winn RJ National Comprehensive Cancer Network. The NCCN guidelines development process and infrastructure. Oncology (Williston Raprk) 2000;14:26–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carlson R the NCCN Breast Cancer Guideline Panel. (c) National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc; The NCCN Breast Cancer clinical practice guidelines in oncology, version (1997–2004) Available at: http://www.nccn.org. To view most recent and complete version of the guideline, go online to www.nccn.org. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cold S, During M, Ewertz M, et al. Does timing of adjuvant chemotherapy influence the prognosis after early breast cancer? Results of the Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group (DBCG) Br J Cancer. 2005;93(6):627–32. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Polychemotherapy for early breast cancer: an overview of the randomised trials. Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group. Lancet. 1998;352(9132):930–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wanzel KR, Brown MH, Anastakis DJ, Regehr G. Reconstructive breast surgery: referring physician knowledge and learning needs. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110(6):1441–50. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000030458.86726.50. discussion 1451–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kronowitz SJ, Robb GL. Breast reconstruction with postmastectomy radiation therapy: current issues. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114(4):950–60. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000133200.99826.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Motwani SB, Strom EA, Schechter NR, et al. The impact of immediate breast reconstruction on the technical delivery of postmastectomy radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;66(1):76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spear SL, Ducic I, Low M, Cuoco F. The effect of radiation on pedicled TRAM flap breast reconstruction: outcomes and implications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115(1):84–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Christian CK, Niland J, Edge SB, et al. A multi-institutional analysis of the socioeconomic determinants of breast reconstruction: a study of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Annals of Surgery. 2006;243(2):241–9. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000197738.63512.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Balasubramanian BA, Gandhi SK, Demissie K, et al. Use of adjuvant systemic therapy for early breast cancer among women 65 years of age and older. Cancer Control. 2007;14(1):63–8. doi: 10.1177/107327480701400109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chang DW, Wang B, Robb GL, et al. Effect of obesity on flap and donor-site complications in free transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap breast reconstruction. [see comment] Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery. 2000;105(5):1640–8. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200004050-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gorin SS, Heck JE, Cheng B, Smith SJ. Delays in breast cancer diagnosis and treatment by racial/ethnic group. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(20):2244–52. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.20.2244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ghafoor A, Jemal A, Ward E, et al. Trends in breast cancer by race and ethnicity. CA Cancer J Clin. 2003;53(6):342–55. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.53.6.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morrow M, Mujahid M, Lantz PM, Janz N, Fagerlin A, et al. Correlates of breast reconstruction. Results from a population-based study. Cancer. 2005;104:2340–2346. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Greenberg CC, Schneider EC, Lipsitz SR, et al. Do variations in provider discussions explain socioeconomic disparities in postmastectomy breast reconstruction? J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206(4):605–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]