Abstract

Patients’ experience of stereotype threat in clinical settings and encounters may be one contributor to health care disparities. Stereotype threat occurs when cues in the environment make negative stereotypes associated with an individual’s group status salient, triggering physiological and psychological processes that have detrimental consequences for behavior. By recognizing and understanding the factors that can trigger stereotype threat and understanding its consequences in medical settings, providers can prevent it from occurring or ameliorate its consequences for patient behavior and outcomes. In this paper, we discuss the implications of stereotype threat for medical education and trainee performance and offer practical suggestions for how future providers might reduce stereotype threat in their exam rooms and clinics.

KEY WORDS: stereotypes, disparities, experience, performance, training

In an experiment that is now considered a modern classic in social psychology,1,2 black and white undergraduates at the University of Michigan were given a test comprised of difficult items from the verbal section of the Graduate Record Examination. Half of these students were told that they were taking an intelligence test; the other half was told that the test was not diagnostic of intellectual ability. In a stunning finding (since replicated numerous times), black students performed worse than their white counterparts when the task was framed as an intelligence test, but performed equally well as whites when the test was framed as non-diagnostic of intelligence.

INTRODUCTION

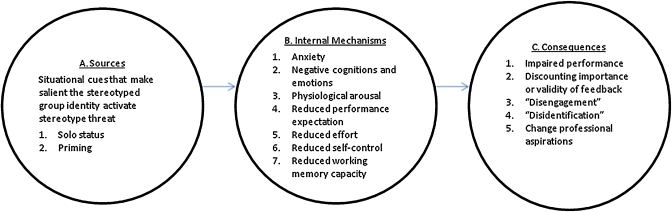

Claude Steele and Joshua Aronson, the authors of the above study, coined the term “stereotype threat” to explain this pattern of results.2 Stereotype threat occurs when cues in the environment make negative stereotypes associated with an individual’s group status salient, triggering physiological and psychological processes--including anxiety,3 negative cognitions and emotions,4,5 physiological arousal,6,7 and reductions in performance expectations,8,9 effort,10 self-control,11 and working memory capacity12--that have detrimental consequences for behavior. (See Fig. 1.) Stereotype threat has been shown to lead to lower performance on tests of intellectual ability for blacks,2,13,14 Latinos,14,15 and low socio-economic status individuals;16,17 poorer math performance among women;3,13,14 poorer social skills among individuals with schizophrenia;18 and poorer performance on tests of cognitive ability for the elderly,19–22 drug users,23 and individuals with mental illness,24 and head injuries.18,25 Stereotype threat has also been shown to lead individuals to discount the importance or validity of performance feedback, such as believing that the results of math tests or intelligence tests are unfair.26,27 Individuals may also “disengage” from domains that are perceived as threatening, in which they view the domain (e.g., academics) as unimportant.28 In the longer term, stereotype threat can result in disidentification, in which minorities define their group’s identity in ways that distinguish it from the majority group and no longer view the domain as central to their identity, and as a result, stop expending effort in this domain.29,30 Stereotype threat has also been shown to alter professional aspirations31 and to produce more guarded ways that members of different groups interact with each other.32

Figure 1.

Sources, mechanisms and consequences of stereotype threat.

In this article we draw upon empirical studies on stereotype threat, including meta-analyses and systematic reviews,13,14,33 to gain insight into potential sources, consequences of, and ways to reduce stereotype threat for minority patients and for minority and non-minority medical trainees.

STEREOTYPE THREAT AND MINORITY PATIENTS

Potential Sources of Stereotype Threat in Clinical Settings

Qualitative studies of minority patients suggest stereotype threat is likely to be triggered by features in the clinical setting that makes salient the stereotype of minority patients as unintelligent, “second class citizens”; and unworthy of good care (i.e., wasting the provider’s time).34–38 This experience of stereotype threat in healthcare settings is illustrated by the following quotations:

“My name is... [a common Hispanic surname] and when they see that name, I think there is...some kind of prejudice of the name...there’s a lack of respect. They think they can get away with a lot because “Here’s another dumb Mexican.” –Mexican American patient (p. 393)36

...The system gets the concept of black people off the 6 o’clock news, and they treat us all the same way. Here’s a guy coming in here with no insurance. He’s a low breed.

–Black patient (p. 2071)35

Such beliefs are likely to have multiple causes, including experiences of discrimination and disrespectful treatment in healthcare and in other settings, and more subtle perceptions of being perceived stereotypically by healthcare professionals.39–41 Indeed, evidence shows that healthcare providers hold conscious and unconscious negative stereotypes of non-white patients, tending to view them as less educated and less likely to be adherent than their white counterparts,.42–46 However, the important point about stereotype threat is it can occur regardless of whether or not the provider holds negative racial stereotypes or manifests racial bias. Rather, stereotype threat is aroused by the target’s activation of a specific stereotype about a social group to which he or she belongs.47

Potential Consequences of Stereotype Threat for Minority Patients

Adherence to treatment. Stereotype threat might contribute to racial disparities in non-adherence to treatment in three ways.48–54 First, numerous studies have shown that stereotype threat reduces working memory capacity12,55 and cognitive performance.13 In clinical encounters, this would translate into diminished ability to process information and follow treatment instructions. Second, stereotype threat has been shown to have negative effects on performance expectations,8,9 and self-control.11 For patients, this might translate into both lowered self-efficacy regarding ability to adhere to treatment. Third, stereotype threat has been linked to lower effort,10 potentially translating to lower motivation to adhere to recommendations.

Communication. Because it increases anxiety3 and physiological arousal, 6,7 stereotype threat might impair the patient’s communication skills, reducing fluency, self-disclosure, and response to the provider’s questions. Stereotype threat, then, might be one factor underlying poorer quality of clinical encounters for black compared with white patients (e.g., lower levels of positive affect, patient participation, shared decision-making; and less time spent by providers in relationship-building behaviors.)56–59 Poorer and less participatory communication is associated with lower patient adherence, utilization, self-management, and symptom recovery.60–67

Discounting feedback. Stereotype threat also has been shown to lead individuals to discount the importance or validity of feedback in domains in which he or she feels threatened. 26,27,68 In the context of healthcare. a diabetic patient experiencing stereotype threat might discount feedback about elevated HbA1c levels, or a smoker might dismiss information about the negative effects of smoking.

Disengagement. Stereotype threat is an unpleasant experience and may lead to avoidance of and disengagement from situations in which the threat occurs.33 If going to the doctor engenders feelings of inferiority, the patient might be more likely to avoid those experiences. This might help explain greater likelihood among minorities of missing appointments,69 and delaying or failing to obtain needed medical care and preventive health care services.40,53

Disidentification. Disidentification—a long term consequence of stereotype threat in which individuals cease to identify with the domain within which they consistently experience the threat70—would help explain the tendency of racial/ethnic minorities to view health promotion behaviors (e.g., exercising and healthy eating) as “white” and unhealthy behaviors (e.g., eating fast food and red meat) as characteristic of their racial/ethnic group.71 This is problematic since individuals are more likely to engage in behaviors that are central to their self-concept.72,73 Thus, a minority patient may, because of disidentification, detach her identity from the value of living a healthy lifestyle--no longer viewing health behaviors as important to self-worth. This may reduce motivation to adhere to medication, diet and lifestyle recommendations.

Reinforcing of stereotypes. If experiencing stereotype threat leads minority patients to behave in ways that are consistent with stereotypes, the provider’s racial stereotypes are likely to be reinforced. Hence, providers may be more likely to use race in making clinical decisions, resulting in racial disparities in processes and outcomes of care.42–44,74

Reducing Stereotype Threat for Minority Patients

As Steele has argued, “even though the stereotypes held by the larger society might be difficult to change, it is possible to create niches in which negative stereotypes are felt not to apply.”75 That is, stereotype threat, which is elicited by specific cues in a setting, can be avoided or ameliorated directly by managing the signals present in that context, creating “identity-safe” environments that “challenge the validity, relevance, or acceptance of negative stereotypes linked to stigmatized social identities.”31(p. 278) Even small changes, such as giving an individual the opportunity to affirm his or her valued characteristics,76,77 can have important, immediate effects. Below (and summarized in Table 1) we explore how physicians can cultivate “identity-safe niches” in exam rooms and clinics.

Elicit the patient’s values and strengths. In field and laboratory experiments with female college students,76 African American seventh grade students,78 and white college students,79 those who were randomly assigned to engage in “self-affirmation” (i.e., to focus on and affirm their valued characteristics and strengths) were less likely to experience the adverse effects of stereotype threat on academic performance than those who were not. Moreover, in one study, the benefits of self-affirmation persisted two years after the intervention.77 This research underscores the importance of giving patients from stigmatized groups the opportunity to demonstrate their competence, intelligence, and worthiness. For instance, in discussing a health problem that will require significant behavioral change, the physician might ask the patient about a time in his life in which he has dealt with a significant challenge, and encourage him to discuss the qualities within himself that helped him overcome it. This emphasizes that the provider cares about and values the patient’s unique perspective and hence should help diminish the patient’s fear of being viewed stereotypically.62

Invoke high standards and assurance of the patient’s ability to meet those standards. Studies conducted in educational settings suggest that critical feedback that invokes negative racial or ethnic stereotypes related to intelligence or capability is likely to be particularly threatening for members of minority groups.80 As a result, minority patients might discount this feedback by disengaging and eventually might disidentify with the domain. In primary care, raising concerns about non-adherence, smoking, or excess weight, then, have the potential to activate stereotype threat, and diminish motivation to change.80 Evidence from two laboratory experiments suggests that performance feedback is least likely to activate stereotype threat when it communicates high performance standards with assurance that the individual is capable of meeting those standards.80 The provider then, might emphasize that she is setting “a high bar” for the patient because she is confident that he will be able to be successful (e.g., at behavior change, at achieving health-related goals). This style of feedback is associated with increased acceptance of the feedback and motivation to improve80 and is likely to enhance patient adherence to treatment protocols.62

Provide external attributions for patients’ anxiety and difficulties. One way in which stereotype threat impairs performance is by engendering anxiety and negative thoughts about one’s abilities, such as one’s lack of intelligence or competence. Several experiments have been able to reduce stereotype threat by getting individuals to attribute anxiety and/or task difficulty to external circumstances rather than lack of ability.81,82 In clinical settings this might entail a provider checking in with a patient who seems anxious and distracted, reassuring her that such feelings are widespread among patients and offering her practical coping techniques (e.g., take a friend or family member with her, come into the exam room with a few questions, etc). Similarly, for a patient who has had difficulties adhering to treatment, the provider might explain how these are common problems for patients; help identify barriers to adherence, and work together to come up with a plan to overcome them.

Provide cues that diversity is valued. Recent studies point to the importance of creating environments that signal that diverse racial and ethnic groups are valued. In one series of studies, black professionals were presented with corporate materials in which the company’s philosophy about diversity (a “color blind” approach in which a diverse workforce was trained to “embrace their similarities” versus an approach that touted the benefits of diversity) and minority representation (low versus high) were systematically varied.83 Identity threat was most activated in settings in which there was a low minority representation and when the company advocated a color blind philosophy. Interestingly, explicit information that the company valued diversity offset the stereotype threat associated with low minority representation. To the extent that providers have some control over how their particular clinic or facility is run, they might be able to create an identity-safe environment by signaling that they value racial and ethnic diversity. Steps should be taken to ensure high standards of treatment by all employees so that all patients feel valued. Physicians might consider posting “mission statements” that state their commitment to diversity, which could be reinforced by cues in the physical environment, such as images of highly valued ethnic minority role models and artwork that reflects the achievements of the community. Finding ways to communicate an inclusive and welcoming environment is integral to reducing stereotype threat and promoting optimal health and health-seeking behaviors, especially for underserved and minority patients.84

Recruit and retain underrepresented minority providers. In a number of experiments, exposure to African American and female role models who behaved in counter-stereotypic ways reduced the effects of stereotype threat on performance among women and African Americans.85–91 This underscores the importance of recruiting and retaining medical students from underrepresented minority (URM) groups, since the presence of URM physicians will help provide an identity-safe environment. Unfortunately, the considerable evidence that stereotype threat diminishes the academic performance of URMs,13,92 suggests that the same processes occur in graduate medical education, diminishing the goal of increasing the number of URM physicians -- a point which we expand upon in the following section.

Table 1.

Strategies to Reduce Stereotype Threat for Minority Patients and Minority and Majority Trainees

| Target of strategy | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Interventions that reduced stereotype threat | Minority patients | Minority trainees | Majority trainees |

| Self-affirmation exercise76–79 | Teach providers to elicit the patient’s values and strengths in clinical encounters | Provide opportunities to affirm values and strengths during medical education | Provide opportunities to affirm their egalitarian values before activities that may activate fears about own racism (such as cultural competency training) |

| Performance feedback that communicates high standards with assurance that the individual is capable of meeting those standards80 | Teach providers to invoke high standards and assurance of the patient’s ability to meet those standards | Teach medical school faculty to provide feedback to trainees that invokes high standards and assurance of the trainee’s ability to meet those standards | |

| Encouraging individuals to attribute anxiety and/or difficulty to external causes81 | Teach providers to provide external attributions for patients’ anxiety and difficulties | Create opportunities for trainees to attribute difficulties to external causes | |

| Education about the possible effects of stereotype threat on performance82 | Educate minority trainees about the effects of stereotype threat on academic performance | Educate white trainees about the effects of stereotype threat on communication with minority patients | |

| Cues indicating an identity-safe environment (e.g., high minority representation, valuing of diversity)/absence of cues indicating an identity threatening environment (e.g., indications of sexism; low minority representation; “color blind” philosophy) 83,107 | Provide cues that diversity is valued and ensure respectful treatment by all staff | Provide cues that diversity is valued and recruit/retain minority faculty and students. Reduce discrimination, harassment, verbal abuse, and disrespectful treatment | |

| Cues indicating “fair practices” (auditing practices to guard against discrimination)83 | Provide cues (e.g., signs) indicating that the clinic is committed to fair and equal treatment | Put into place and make students aware of procedures to monitor potential instances of discrimination | |

| Exposure to role models who exhibit counter-stereotypic behavior85–91 | Recruit and retain minority providers | Recruit and retain minority faculty | |

| Having individuals identify their demographic characteristics at the end rather than the beginning of test.111,112 | Modify test instructions to reduce stereotype threat | ||

| Promote interracial friendship and communication29,73,127 | Structured interracial “dialogue groups”113–115 | Structured interracial “dialogue groups”113–115 | |

| Adopt a promotion rather than a prevention focus128 | Frame interracial interactions as opportunities to learn rather than situations in which one will be judged32 | ||

STEREOTYPE THREAT AND UNDERREPRESENTED MINORITY TRAINEES

Stereotype threat might also influence patient outcomes through its effect on diversity of the health care work force. Many policy-makers and medical educators have postulated that racial disparities in healthcare could be decreased by increasing the number of physicians from underrepresented minority groups (blacks, Native Americans, Mexican Americans, and mainland Puerto Ricans), who currently comprise only about 6% of practicing physicians.93–96 In addition to the potential of URM physicians to reduce stereotype threat, they also are more likely to practice in underserved areas, treat minority patients, and have greater cultural competency with members of their own minority group.93–95

Unfortunately, there are a number of barriers to increasing the number of URM physicians in the workforce in the United States—some of which may be caused or made greater by stereotype threat. These barriers include lower rates of college matriculation and graduation among URM groups;93 lower acceptance rates to medical school due largely to lower scores on the Medical College Admission Test (MCAT);93 and poorer performance in and higher rates of attrition from medical school.97–100 Moreover, because they tend to score lower than non-URMs on Step One of the United States Medical Licensing Exam (USMLE), they are less likely to be offered a residency interview.101 In addition, members of URM groups tend to perform less well in medical school than their MCAT scores predict, in contrast to whites who tend to perform better than predicted by MCAT scores.14,73,98

Numerous studies documenting the deleterious effect of stereotype threat on academic performance13,14,33 suggest that stereotype threat might play a role at each of these junctures--reducing the performance of URM undergraduates in college, decreasing their likelihood of graduating, diminishing their performance on the MCAT, USMLE, and other tests,14 contributing to apprehension and reticence during clinical clerkships, and potentially reducing evaluation of their clinical performance.102 In addition to the sources of stereotype threat present in standardized testing situations, URM trainees are likely to experience other cues that activate threat, such as being mistaken for housekeepers, orderlies, and nurses; feeling socially and numerically isolated among white-majority medical school cohorts, experiencing a lack of URM faculty role models, discrimination, and feeling pressure to represent their entire race in the classroom and in clinical settings.103,104 The following quotation exemplifies the predicament in which URM trainees may find themselves.

There were 150 students in my class, 13 were black, five of the blacks graduated...It was hard to stay focused. I had to put extra energy into the work. People were looking, people were watching. The assumption was, ‘You’re dumb.” You have to maximize everything. For example, a white boy goes into class to take a test and he just has to worry and concentrate on the test. Every time a black boy goes into the class he has to try hard to stay focused on the work, on the content, because he’s worrying about what the professor thinks of him, what the other students think of him, whether or not he has on the right clothes, or is acting the right way...etc...There’s just a lot of garbage that you end up fighting off and trying to spend all your energy being focused.

–African-American female physician105 (pp. 807–808)

Reducing Stereotype Threat for URM Trainees

There has been little attention to stereotype threat among medical students, with only one published article describing an attempt (unsuccessful) to reduce stereotype threat among URM medical students.106 Studies conducted with other populations suggest potential strategies to reduce stereotype threat among medical students and trainees (See Table 1).

Create identity safe environments. As discussed above, the likelihood stereotype threat will occur is reduced in the presence of cues indicating an identity-safe environment (e.g., high minority representation, valuing of diversity) but is increased by cues indicating identity threat (e.g., indications of prejudice; low minority representation; “color blind” philosophy). 83,107 In creating identity-safe environments, an obvious place to start is to reduce the discrimination, harassment, verbal abuse, and disrespectful treatment that is experienced by many trainees but is most likely to be experienced by blacks.108–110 Although such mistreatment is harmful for all students, it is likely to be particularly threatening for members of minority groups, who are faced with the possibility that such mistreatment is due to their race. Medical schools might also emphasize that the program values multiple perspectives and views diversity as an asset;73 and increase efforts to recruit and retain minority faculty. There is also evidence that cues indicating “high fairness” (in this case, auditing practices that guard against discrimination) can increase trust and reduce identity threat among ethnic minorities, even in settings with cues that invoke stereotype threat.83

Incorporate strategies to reduce stereotype threat in standardized testing situations. It is recommended that existing stereotype reduction strategies that have successfully reduced the racial achievement gap in standardized testing and academic performance be incorporated in graduate medical education and existing programs designed to prepare undergraduate URM for medical careers. This includes modifying test instructions to reduce the salience of race and ethnicity by having individuals identify their demographic characteristics at the end rather than the beginning of a standardized test,111,112 and teaching students about stereotype threat before taking the test.82 It is important to note, however, that the single study we were able to locate, which adapted a prior intervention that successfully reduced the negative effects of stereotype threat among African American adolescents (a written self-affirmation intervention)77,78,92 for use with UK medical students was not effective at reducing ethnic disparities in performance on written and clinical assessments,106 highlighting potential challenges in translating such interventions.

Structured opportunities for dialogue among URM and white/non-URM trainees. Structured “dialogue groups” that allow individuals of different races and ethnicities to share and reflect upon their experiences with one another, over a sustained period of time, can help foster interracial/interethnic friendships and increase comfort and understanding between group members.113–115 Providing white and minority students the opportunity to discuss their academic difficulties also allows minority students to see that the problems they experience are a common consequence of the stresses of medical education rather than due entirely to their race or their individual deficiencies.29,73

Teach faculty how to provide effective feedback. Medical schools might also teach faculty how to provide effective feedback that emphasizes that the faculty member is using high standards and has confidence in the students’ ability to meet those standards, which (as described in the previous section) has been shown to reduce stereotype threat experienced by racial minority students when receiving critical feedback.

STEREOTYPE THREAT AND WHITE TRAINEES

Several studies have shown that white individuals are aware of the stereotype of the “white racist,”116–119 and that the anxiety associated with this threat has negative cognitive and behavioral consequences: the impairment of working memory120 caused by self-regulatory behaviors (e.g., monitoring or regulating one’s behaviors to avoid appearing prejudiced),117,118,120,121 “distancing” behaviors (e.g., fidgeting, avoiding eye contact), and increases in implicit (unconscious) pro-white bias.79,120,122 In one series of experiments, the threat of appearing racist activated the “white racist” stereotype and led whites to physically distance themselves from African American conversation partners.32 Interestingly, this distancing behavior was not associated with implicit or explicit racism,32 suggesting that stereotype threat alone is a sufficient condition for racial bias. Within the domain of healthcare, a recent study found that physicians experience anxiety when interacting with black or Latino patients and that self-reported ratings of interracial anxiety were associated with lower patient ratings of encounter quality among non-white patients.123

These consequences of stereotype threat are, ironically, likely to reduce the quality of communication with minority patients and increase the extent to which white providers’ diagnostic and therapeutic decision-making will be influenced by racial stereotypes.42–44,74 It may be that the same patient behaviors that result from the minority patient’s experience of stereotype threat (e.g., exhibiting unease, speaking little) are perceived by the provider as evidence of mistrust or disengagement, setting up negative expectations for the clinical encounter.

Reducing Stereotype Threat for White Trainees

Although more research is needed, it is prudent that training aimed at improving the care of minority patients are constructed in a way that minimizes stereotype threat associated with the fear of being perceived as racist. Table 1 provides examples of potential strategies, based on the stereotype threat literature. One study has shown that affirming one’s egalitarian values reduced the negative consequences of stereotype threat related to “white racism.” Trainees could be given the opportunity for self-affirmation before activities, such as cultural competency training, that might activate stereotype threat among whites. In addition, trainees might be taught about stereotype threat, because this can help reduce it.124

It is further recommended that formal and informal educational activities adopt a “promotion focus” aimed at promoting equal treatment of all races/ethnicities rather than a “prevention focus,” aimed at avoiding bias. A prevention focus involves a sensitivity to negative outcomes, arouses negative emotions such as guilt and anxiety, and produces an avoidance motivation. An example is “strategic color blindness,” in which whites try to “avoid” noticing or mentioning race—a strategy that can increase stereotype threat.124 By contrast, a promotion focus directs attention to potential positive outcomes and benefits, elicits positive emotions associated with making progress, and generates an approach orientation. This might involve teaching trainees to view interracial interactions as opportunities to learn rather than a situation in which they will be judged.32 Finally, increasing the number of minority medical students and providing structured activities to foster the type of sustained, interracial dialogue that can lead to interracial friendship among medical trainees125,126 is a particularly powerful, promotion-oriented approach for reducing stereotype threat among white and non-white trainees.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a VA HSR&D Merit Review Entry Program award to Diana Burgess, Ph.D.

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

References

- 1.Devine PG, Brodish AB. Modern classics in social psychology. Psychol Inq;14(3–4):196–202

- 2.Steele CM, Aronson J. Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;69(5):797–811. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spencer SJ, Steele CM, Quinn DM. Stereotype threat and women’s math performance. J Exp Soc Psychol. 1999;35:4–28. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keller J, Dauenheimer D. Stereotype threat in the classroom: dejection mediates the disrupting threat effect on women’s math performance. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2003;29(3):371–381. doi: 10.1177/0146167202250218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cadinu M, Maass A, Rosabianca A, Kiesner J. Why do women underperform under stereotype threat? Evidence for the role of negative thinking. Psychol Sci. 2005;16(7):572–578. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.01577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Croizet JC, Despres G, Gauzins ME, Huguet P, Leyens JP, Meot A. Stereotype threat undermines intellectual performance by triggering a disruptive mental load. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2004;30(6):721–731. doi: 10.1177/0146167204263961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blascovich J, Spencer SJ, Quinn D, Steele C. African Americans and high blood pressure: the role of stereotype threat. Psychol Sci. 2001;12(3):225–229. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cadinu M, Maass A, Frigerio S, Impagliazzo L, Latinotti S. Stereotype threat: the effect of expectancy on performance. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2003;33(2).

- 9.Kray LJ, Thompson L, Galinsky A. Battle of the sexes: gender stereotype confirmation and reactance in negotiations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2001;80(6):942–958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stone J. Battling doubt by avoiding practice: the effects of stereotype threat on self-handicapping in white athletes. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2002;28(12).

- 11.Smith JL, White PH. An examination of implicitly activated, explicitly activated, and nullified stereotypes on mathematical performance: it’s not just a woman’s issue. Sex Roles. 2002;47(3–4).

- 12.Schmader T, Johns M. Converging evidence that stereotype threat reduces working memory capacity. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;85(3):440–452. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.3.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nguyen HH, Ryan AM. Does stereotype threat affect test performance of minorities and women? A meta-analysis of experimental evidence. J Appl Psychol. 2008;93(6):1314–1334. doi: 10.1037/a0012702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walton GM, Spencer SJ. Latent ability: grades and test scores systematically underestimate the intellectual ability of negatively stereotyped students. Psychol Sci. 2009;20(9):1132–1139. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gonzales PM, Blanton H, Williams KJ. The Effects of stereotype threat and double-minority status on the test performance of Latino women. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2002;28:659–670. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Croizet J-C, Claire T. Extending the concept of stereotype and threat to social class: the intellectual underperformance of students from low socioeconimic backgrounds. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1998;24:588–594. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spencer B, Castano E. Social class is dead. Long live social class! Stereotype threat among low socioeconomic status individuals. Soc Justice Res. 2007;20:418–432. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henry JD, Hippel CV, Shapiro L. Stereotype threat contributes to social difficulties in people with schizophrenia. Br J Clin Psychol. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Horton S, Baker J, Pearce GW, Deakin JM. On the malleability of performance: implications for seniors. J Appl Gerontol. 2008;27:446–465. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hess TM, Auman C, Colcombe SJ, Rahhal TA. The impact of stereotype threat on age differences in memory performance. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2003;58(1):P3–11. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.1.p3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hess TM, Hinson JT, Hodges EA. Moderators of and mechanisms underlying stereotype threat effects on older adults’ memory performance. Exp Aging Res. 2009;35(2):153–177. doi: 10.1080/03610730802716413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chasteen AL, Bhattacharyya S, Horhota M, Tam R, Hasher L. How feelings of stereotype threat influence older adults’ memory performance. Exp Aging Res. 2005;31(3):235–260. doi: 10.1080/03610730590948177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cole JC, Michailidou K, Jerome L, Sumnall HR. The effects of stereotype threat on cognitive function in ecstasy users. J Psychopharmacol. 2006;20(4):518–525. doi: 10.1177/0269881105058572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quinn DM, Kahng SK, Crocker J. Discreditable: stigma effects of revealing a mental illness history on test performance. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2004;30(7):803–815. doi: 10.1177/0146167204264088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suhr JA, Gunstad J. “Diagnosis Threat”: the effect of negative expectations on cognitive performance in head injury. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2002;24(4):448–457. doi: 10.1076/jcen.24.4.448.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keller J. Blatant stereotype threat and women’s math performance: Self-handicapping as a strategic means to cope with obtrusive negative performance expectations. Sex Roles. 2002;47(3–4).

- 27.Klein O, Pohl S, Ndagijimana C. The influence of intergroup comparisons on Africans’ intelligence test performance in a job selection context. J Psychol. 2007;141(5). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Hippel W, Hippel C, Conway L, Preacher KJ, Schooler JW, Radvansky GA. Coping with stereotype threat: denial as an impression management strategy. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2005;89(1):22–35. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steele CM, Spencer SJ, Aronson J. Contending with group image: the psychology of stereotype and social identity threat. Adv Exp Soc Psychol. 2002;34:379–440. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Osborne JW. Race and academic disidentification. J Educ Psychol. 1997;89(4).

- 31.Davies PG, Spencer SJ, Steele CM. Clearing the air: identity safety moderates the effects of stereotype threat on women’s leadership aspirations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2005;88(2):276–287. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goff PA, Steele CM, Davies PG. The space between us: stereotype threat and distance in interracial contexts. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2008;94(1):91–107. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.94.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spencer S. Stereotype threat. Annu Rev Psychol. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Becker G, Newsom E. Socioeconomic status and dissatisfaction with health care among chronically ill African Americans. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(5):742–748. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.5.742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Becker G, Gates RJ, Newsom E. Self-care among chronically ill African Americans: culture, health disparities, and health insurance status. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(12):2066–2073. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.12.2066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grady M, Edgar T. Racial disparities in healthcare: highlights from focus group findings. In: Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparites in Healthcare. Washington: The National Academies Press; 2003. pp. 392–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hatzfeld JJ, Cody-Connor C, Whitaker VB, Gaston-Johansson F. African-American perceptions of health disparities: a qualitative analysis. J Natl Black Nurses Assoc. 2008;19(1):34–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gaston-Johansson F, Hill-Briggs F, Oguntomilade L, Bradley V, Mason P. Patient perspectives on disparities in healthcare from African-American, Asian, Hispanic, and Native American samples including a secondary analysis of the Institute of Medicine focus group data. J Natl Black Nurses Assoc. 2007;18(2):43–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blanchard J, Lurie N. R-E-S-P-E-C-T: patient reports of disrespect in the health care setting and its impact on care. J Fam Pract. 2004;53(9):721–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trivedi AN, Ayanian JZ. Perceived discrimination and use of preventive health services. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(6):553–558. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00413.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Houtven CH, Voils CI, Oddone EZ, et al. Perceived discrimination and reported delay of pharmacy prescriptions and medical tests. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(7):578–583. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0123.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burgess DJ, Ryn M, Malat J, Matoka M. Understanding the provider contribution to race/ethnicity disparities in pain treatment: insights from social cognitive research on stereotyping. Pain Med. 2006;7:119–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2006.00105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ryn M, Fu SS. Paved with good intentions: do public health and human service providers contribute to racial/ethnic disparities in health? Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):248–255. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ryn M. Research on the provider contribution to race/ethnicity disparities in medical care. Med Care. 2002;40(1 Suppl):I140–I151. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200201001-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ryn M, Burke J. The effect of patient race and socio-economic status on physicians’ perceptions of patients. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50(6):813–828. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00338-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Green AR, Carney DR, Pallin DJ, et al. Implicit bias among physicians and its prediction of thrombolysis decisions for black and white patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(9):1231–1238. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0258-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marx DM, Stapel DA. Distinguishing stereotype threat from priming effects: on the role of the social self and threat-based concerns. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2006;91(2):243–254. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saha S, Freeman M, Toure J, Tippens KM, Weeks C, Ibrahim S. Racial and ethnic disparities in the VA Health Care System: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Trinacty CM, Adams AS, Soumerai SB, et al. Racial differences in long-term adherence to oral antidiabetic drug therapy: a longitudinal cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:24. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Duru OK, Gerzoff RB, Selby JV, et al. Identifying risk factors for racial disparities in diabetes outcomes: the translating research into action for diabetes study. Med Care. 2009;47(6):700–706. doi: 10.1097/mlr.0b013e318192609d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thrasher AD, Earp JA, Golin CE, Zimmer CR. Discrimination, distrust, and racial/ethnic disparities in antiretroviral therapy adherence among a national sample of HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;49(1):84–93. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181845589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Heisler M, Faul JD, Hayward RA, Langa KM, Blaum C, Weir D. Mechanisms for racial and ethnic disparities in glycemic control in middle-aged and older Americans in the health and retirement study. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(17):1853–1860. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.17.1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Casagrande SS, Gary TL, LaVeist TA, Gaskin DJ, Cooper LA. Perceived discrimination and adherence to medical care in a racially integrated community. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(3):389–395. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0057-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Apter AJ, Boston RC, George M, et al. Modifiable barriers to adherence to inhaled steroids among adults with asthma: it’s not just black and white. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111(6):1219–1226. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schmader T, Johns M, Forbes C. An integrated process model of stereotype threat effects on performance. Psychol Rev. 2008;115(2):336–356. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.115.2.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cooper LA, Roter DL, Johnson RL, Ford DE, Steinwachs DM, Powe NR. Patient-centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(11):907–915. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-11-200312020-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cooper-Patrick L, Gallo JJ, Gonzales JJ, et al. Race, gender, and partnership in the patient-physician relationship. JAMA. 1999;282(6):583–589. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.6.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Levinson W, Hudak PL, Feldman JJ, et al. “It’s not what you say ...”: Racial disparities in communication between orthopedic surgeons and patients. Med Care. 2008;46(4):410–416. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31815f5392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gordon HS, Street RL, Jr, Kelly PA, Souchek J, Wray NP. Physician-patient communication following invasive procedures: an analysis of post-angiogram consultations. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(5):1015–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Greenlund KJ, Keenan NL, Anderson LA, Mandelson MT, Newton KM, LaCroix AZ. Does provider prevention orientation influence female patients’ preventive practices? Am J Prev Med. 2000;19(2):104–110. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00184-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Greenlund KJ, Giles WH, Keenan NL, Croft JB, Mensah GA. Physician advice, patient actions, and health-related quality of life in secondary prevention of stroke through diet and exercise. Stroke. 2002;33(2):565–571. doi: 10.1161/hs0202.102882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brown JB, Stewart M, Ryan BL. Outcomes of patient-provider interaction. In: Teresa L, Thompson AMD, Miller KI, Parrott R, editors. Handbook of Health Communication. London: LEA; 2003. pp. 141–163. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A, et al. The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract. 2000;49(9):796–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kaplan SH, Greenfield S, Ware JE., Jr Assessing the effects of physician-patient interactions on the outcomes of chronic disease. Med Care. 1989;27(3 Suppl):S110–S127. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198903001-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Greenfield S, Kaplan S, Ware JE., Jr Expanding patient involvement in care. Effects on patient outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 1985;102(4):520–528. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-102-4-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Greenfield S, Kaplan SH, Ware JE, Jr, Yano EM, Frank HJ. Patients’ participation in medical care: effects on blood sugar control and quality of life in diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 1988;3(5):448–457. doi: 10.1007/BF02595921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rao JK, Weinberger M, Kroenke K. Visit-specific expectations and patient-centered outcomes: a literature review. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9(10):1148–1155. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.10.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Steele CM. Stereotyping and its threat are real. Am Psychol. 1998;53(6):680–681. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schectman JM, Schorling JB, Voss JD. Appointment adherence and disparities in outcomes among patients with diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(10):1685–1687. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0747-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Major B, O’Brien LT. The social psychology of stigma. Annu Rev Psychol. 2005;56:393–421. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Oyserman D, Fryberg SA, Yoder N. Identity-based motivation and health. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2007;93(6):1011–1027. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.6.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Crocker J, Major B, Steel C. Social stigma. In: Gilbert D, Fiske ST, Lindzey G, editors. The Handbook of Social Psychology. Vol 2. 4. Boston: McGraw-Hill; 1998. pp. 504–553. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Steele CM. A threat in the air. How stereotypes shape intellectual identity and performance. Am Psychol. 1997;52(6):613–629. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.52.6.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Burgess DJ, Fu SS, Ryn M. Why do providers contribute to disparities and what can be done about it? J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(11):1154–1159. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30227.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Steele CM. Race and the schooling of Black Americans. The Atlantic Monthly. 1992:68–78.

- 76.Martens A, Johns M, Greenberg J, Schimel J. Combating stereotype threat: the effect of self-affirmation on women’s intellectual performance. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2006;42:236–243. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cohen GL, Garcia J, Purdie-Vaughns V, Apfel N, Brzustoski P. Recursive processes in self-affirmation: intervening to close the minority achievement gap. Science. 2009;324(5925):400–403. doi: 10.1126/science.1170769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cohen GL, Garcia J, Apfel N, Master A. Reducing the racial achievement gap: a social-psychological intervention. Science. 2006;313:1307–1310. doi: 10.1126/science.1128317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Frantz CM, Cuddy AJ, Burnett M, Ray H, Hart A. A threat in the computer: the race implicit association test as a stereotype threat experience. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2004;30(12):1611–1624. doi: 10.1177/0146167204266650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cohen GL, Steele CM, Ross LD. The mentor’s dilemma: providing critical feedback across the racial divide. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1999;25(10):1302–1318. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Good C, Aronson J, Inzlicht M. Improving adolescents’ standardized test performance: An intervention to reduce the effects of stereotype threat. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2003;24:645–662. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Johns M, Schmader T, Martens A. Knowing is half the battle: teaching stereotype threat as a means of improving women’s math performance. Psychol Sci. 2005;16(3):175–179. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.00799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Purdie-Vaughns V, Steele CM, Davies PG, Ditlmann R, Crosby JR. Social identity contingencies: How diversity cues signal threat or safety for African Americans in mainstream institutions. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2008;94:615–630. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.94.4.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ford AL, Yep GA. Working along the margins: developing community-based strategies for communicating about health with marginalized groups. In: Thompson AMD TL, Miller KI, Parrott R, editors. Handbook of Health Communication. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2003. pp. 241–262. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Marx DM, Ko SJ, Friedman RA. The Obama effect: how a salient role model reduces race-based performance differences. J Exp Soc Psychol. in press.

- 86.Marx DM, Goff PA. Clearing the air: the effect of experimenter race on target’s test performance and subjective experience. Br J Soc Psychol. 2005;44(Pt 4):645–657. doi: 10.1348/014466604X17948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.McIntyre RB, Lord CG, Gresky DM, Ten Eyck LL, Jay Frye G, Bond CF. A social impact trend in the effects of role models on alleviating women’s mathematics stereotype threat. Curr Res Soc Psychol. 2005;10(9).

- 88.Marx DM, Ko SJ, Friedman RA. The “Obama effect”: how a salient role model reduces race-based performance differences. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2009;45(4).

- 89.Marx DM, Goff PA. Clearing the air: the effect of experimenter race on target’s test performance and subjective experience. Br J Soc Psychol. 2005;44(4). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 90.Marx DM, Stapel DA, Muller D. We can do it: the interplay of construal orientation and social comparisons under threat. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2005;88(3). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 91.Marx DM, Roman JS. Female role models: protecting women’s math test performance. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2002;28(9).

- 92.Walton GM, Cohen GL. A question of belonging: race, social fit, and achievement. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2007;92(1):82–96. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Education CoGM. Minorities in medicine: an ethnic and cultural challenge for physician training: U.S. department of health and human services. 2005.

- 94.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare. Washington: National Academy Press; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Minorities in Medical Education: Facts & Figures. Washington, D.C.: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2005.

- 96.Brotherton SE, Simon FA, Etzel SI. US graduate medical education, 2001–2002: changing dynamics. JAMA. 2002;288(9):1073–1078. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.9.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Woolf K, Haq I, McManus IC, Higham J, Dacre J. Exploring the underperformance of male and minority ethnic medical students in first year clinical examinations. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2008;13(5):607–616. doi: 10.1007/s10459-007-9067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Koenig JA, Sireci SG, Wiley A. Evaluating the predictive validity of MCAT scores across diverse applicant groups. Acad Med. 1998;73(10):1095–1106. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199810000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Huff KL, Fang D. When are students most at risk of encountering academic difficulty? A study of the 1992 matriculants to U.S. medical schools. Acad Med. 1999;74:454–460. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199904000-00047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Tekian A. Attrition rates of underrepresented minority students at the University of Illinois at Chicago College of Medicine, 1993–1997. Acad Med. 1998;73(3):336–338. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199803000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Edmond MB, Deschenes JL, Eckler M, Wenzel RP. Racial bias in using USMLE step 1 scores to grant internal medicine residency interviews. Acad Med. 2001;76(12):1253–1256. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200112000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lee KB, Vaishnavi SN, Lau SK, Andriole DA, Jeffe DB. Cultural competency in medical education: demographic differences associated with medical student communication styles and clinical clerkship feedback. J Natl Med Assoc. 2009;101(2):116–126. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30823-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Liebschutz JM, Darko GO, Finley EP, Cawse JM, Bharel M, Orlander JD. In the minority: black physicians in residency and their experiences. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98(9):1441–1448. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Odom KL, Roberts LM, Johnson RL, Cooper LA. Exploring obstacles to and opportunities for professional success among ethnic minority medical students. Acad Med. 2007;82(2):146–153. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31802d8f2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Erwin DO, Henry-Tillman RS, Thomas BR. A qualitative study of the experiences of one group of African Americans in pursuit of a career in academic medicine. J Natl Med Assoc. 2002;94(9):802–812. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Woolf K, McManus IC, Gill D, Dacre J. The effect of a brief social intervention on the examination results of UK medical students: a cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC Med Educ. 2009;9:35. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-9-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Logel C, Walton GM, Spencer SJ, Iserman EC, Hippel W, Bell AE. Interacting with sexist men triggers social identity threat among female engineers. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2009;96(6):1089–1103. doi: 10.1037/a0015703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Baldwin DC, Jr, Daugherty SR, Rowley BD. Racial and ethnic discrimination during residency: results of a national survey. Acad Med. 1994;69(10 Suppl):S19–S21. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199410000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Baldwin DC, Jr, Daugherty SR, Rowley BD. Residents’ and medical students’ reports of sexual harassment and discrimination. Acad Med. 1996;71(10 Suppl):S25–S27. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199610000-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Sheehan KH, Sheehan DV, White K, Leibowitz A, Baldwin DC., Jr A pilot study of medical student ‘abuse’. Student perceptions of mistreatment and misconduct in medical school. JAMA. 1990;263(4):533–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Stricker LJ, Ward WC. Stereotype threat, inquiring about test takers’ ethnicity and gender, and standardized test performance. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2004;34:665–693. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Danaher K, Crandall CS. Stereotype threat in applied settings re-examined. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2008;38:1639–1655. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Nagda BA. Breaking barriers, crossing borders, building bridges: communication processes in intergroup dialogues. J Soc Issues. 2006;62(3).

- 114.Nagda BA, Kim C-W, Truelove Y. Learning about difference, learning with others, learning to transgress. J Soc Issues. 2004;60(1).

- 115.Nagda BA, Zuniga X. Fostering meaningful racial engagement through intergroup dialogues. Group Process Intergroup Relat. 2003;6(1).

- 116.Vorauer JD, Main KJ, O’Connell GB. How do individuals expect to be viewed by members of lower status groups? Content and implications of meta-stereotypes. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;75(4):917–937. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.4.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Vorauer JD, Hunter AJ, Main KJ, Roy SA. Meta-stereotype activation: evidence from indirect measures for specific evaluative concerns experienced by members of dominant groups in intergroup interaction. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;78(4):690–707. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.4.690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Plant EA, Devine PG. Internal and external motivation to respond without prejudice. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;75(3):811–832. doi: 10.1177/0146167205275304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Plant EA, Devine PG. Interracial interactions: approach and avoidance. In: Elliott A, editor. Handbook of Approach and Avoidance Motivation. New York: Psychology Press; 2008. pp. 571–584. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Richeson JA, Trawalter S. Why do interracial interactions impair executive function? A resource depletion account. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2005;88(6):934–947. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.6.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Richeson JA, Shelton JN. When prejudice does not pay: effects of interracial contact on executive function. Psychol Sci. 2003;14:287–290. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.03437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Richeson JA, Trawalter S. The threat of appearing prejudiced and race-based attentional biases. Psychol Sci. 2008;19(2):98–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Saha S, Korthuis P, Cohn A, Sharp V, Moore R, Beach M. Physician interracial anxiety, patient trust, and satisfaction with HIV care. Presentation at the International Conference on Communication in Healthcare. Oslo, Norway. September 2008.

- 124.Apfelbaum EP, Sommers SR, Norton MI. Seeing race and seeming racist? Evaluating strategic colorblindness in social interaction. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2008;95(4):918–932. doi: 10.1037/a0011990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Pettigrew TF, Tropp LR. A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2006;90(5):751–783. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Page-Gould E, Mendoza-Denton R, Tropp LR. With a little help from my cross-group friend: reducing anxiety in intergroup contexts through cross-group friendship. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2008;95(5):1080–1094. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.95.5.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Pettigrew TF. Intergroup contact theory. Annu Rev Psychol. 1998;49:65–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Higgins ET. Promotion and prevention as motivational duality: implications for evaluative processes. In: Trope SCY, editor. Dual-Process Theories in Social Psychology. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 503–525. [Google Scholar]