Abstract

Introduction

Medical-legal partnerships (MLPs) bring together medical professionals and lawyers to address social causes of health disparities, including access to adequate food, housing and income.

Setting

Eighty-one MLPs offer legal services for patients whose basic needs are not being met.

Program Description

Besides providing legal help to patients and working on policy advocacy, MLPs educate residents (29 residency programs), health care providers (160 clinics and hospitals) and medical students (25 medical schools) about how social conditions affect health and screening for unmet basic needs, and how these needs can often be impacted by enforcing federal and state laws. These curricula include medical school courses, noon conferences, advocacy electives and CME courses.

Program Evaluation

Four example programs are described in this paper. Established MLPs have changed knowledge (MLP | Boston—97% reported screening for two unmet needs), attitudes (Stanford reported reduced concern about making patients “nervous” with legal questions from 38% to 21%) and behavior (NY LegalHealth reported increasing resident referrals from 15% to 54%) after trainings. One developing MLP found doctors experienced difficulty addressing social issues (NJ LAMP—67% of residents felt uncomfortable).

Discussion

MLPs train residents, students and other health care providers to tackle socially caused health disparities.

Key words: medical-legal partnerships (MLPs), health disparities, health care training

INTRODUCTION

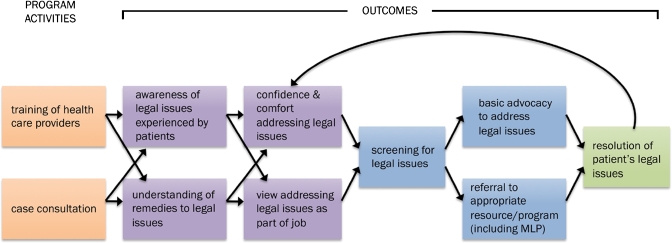

Medical-legal partnerships (MLPs), first developed at Boston Medical Center in 1993, combine the skill sets of medical professionals and lawyers to treat and teach social determinants of health.1 In 2009, the National Center for Medical-Legal Partnership was formed to guide the continuing expansion of this model nationwide.2 The principal goal of MLPs is to ensure that laws impacting health are implemented and enforced, particularly among vulnerable populations.3 Common barriers to good health include food and income insecurity, lack of health insurance, inappropriate education or utilities access, poor housing conditions, and lack of personal stability and safety. Where possible, MLPs strive to identify and address legal problems early, through nonstressful and administrative legal solutions, before legal needs become crises requiring litigation (Fig. 1).4

Figure 1.

Proposed conceptual framework of MLP education program effectiveness (developed by Mark Hansen).

Given that over half of poor and moderate-income individuals experience multiple legal problems,5 the addition of lawyers to the medical team can promote health and address barriers to effective health care.6 These non-medical needs have legal solutions that, if addressed, can diminish health disparities. A recent Robert Wood Johnson report cited MLPs as an action step for health care providers to address social disparities.7 This article will feature selected MLP programs to illustrate how MLPs teach physicians and other health care providers to address health disparities. These four programs were selected on the basis of their successful educational curricula and innovative practices, developed jointly by doctors and lawyers. They exemplify a wide range of practice settings: a legal service-based, multi-disciplinary, multi-hospital site; a community hospital residency-based program; a safety net hospital with multiple community clinics; and a site that developed a joint law school and medical school course.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

In 2008, there were 81 MLP sites serving 160 hospitals and health centers across the US (site map at www.medical-legalpartnership.org). Education of physicians and other health care professionals is an essential component of the MLP model.8 In 2008, MLP lawyers nationwide conducted 870 training sessions for health care and legal staff, reaching 17,606 people. MLP curricula have been incorporated into 29 residency programs. Twenty-five medical schools participate in MLPs, with 17% having a dedicated MLP course and 20% offering MLP electives. Four partnerships offer joint medical and law student courses.

Curricula at the various MLPs are developed locally by medical and legal professionals. The mnemonic I-HELPSM is often used to teach the broad topics, though sites designate different sub-areas to represent their patient population’s varying legal needs. These include income supports (e.g., health insurance, food stamps, disability benefits), housing (e.g., affordability, conditions and utility access), employment/education, legal status (immigration) and personal stability (includes advanced care directives, domestic violence and guardianship issues).9

Four MLP programs, their educational curricula (Table 1) and available evaluation data are described below. These data are the result of preliminary pilot studies. These trainings and the corresponding pilot studies are done with residents with diverse backgrounds interested in primary and subspecialty care, and are part of their required curriculum. Curricula are case-based and delivered in many formats (Table 1). Evaluations received IRB approval at local institutions.

Table 1.

Description of Selected Medical Legal Partnership Programs

| Types of teaching methods | MLP programs using these types of methods | Examples of topics covered | Types of educational settings | Evaluation methods | Lessons learned |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Didactic sessions | LegalHealth | Bring advocacy to practice | Grand rounds | Pre-post test evaluations | Important to have take-home messages clear |

| Legal Assistance to Medical Patients (LAMP) | Forms 101 (disability,others) | Resident conferences | Case-based learning essential | ||

| Medical Legal Partnership | Boston (MLP | Boston) | Improving your patient’s housing | Rotation block conferences | |||

| Pennisula Family Advocacy Program (FAP) | Your patient and the workplace | Staff meetings | |||

| Immigrants and health care system | CME/advocacy Boot camps | ||||

| Health and legal decision making | |||||

| Direct one-on-one teaching around cases | LegalHealth | Income supports | Continuity clinics | Qualitative evaluations | Feedback as crucial teachable moments |

| Legal Assistance to Medical Patients (LAMP) | Housing and utilities | Primary care outpatient blocks | |||

| Medical Legal Partnership | Boston (MLP | Boston) | Employment and education | Inpatient wards | |||

| Pennisula Family Advocacy Program (FAP) | Legal status (i.e., immigration) | ||||

| Personal stability (i.e., advanced directives, guardianship) | |||||

| Block courses or rotations (required or elective) | Medical Legal Partnership | Boston (MLP | Boston) | Learn social disparities in health | Electives | Pre-post evaluation | Model grids essential |

| Pennisula Family Advocacy Program (FAP) | Learn legal topic knowledge above | Required courses | Qualitative evaluation | Project examples helpful | |

| Apply knowledge for use in project around legal solutions to disparities | Poverty simulations | Project evaluation | |||

LEGALHEALTH

LegalHealth, a division of the New York Legal Assistance Group, has weekly, onsite legal clinics at 16 teaching hospitals, community hospitals or health clinics, and trains physicians and social workers at those sites.10 LegalHealth serves over 3,500 patients annually, operating legal clinics within internal medicine, geriatrics, oncology, palliative care, family medicine, pediatrics, emergency medicine and social work departments.11 Core trainings are listed in Table 1.

Pre- and post-survey data evaluating LegalHealth training curricula were collected from three hospitals at which 143 residents completed pre-surveys and 48 residents completed post-surveys (33% response rate). The data revealed changes in attitude about the responsibility of the physician to help patients find free legal services (21% to 52%) and changes in behavior in referring patients to legal services (15% to 54%), in assisting patients with obtaining government benefits (45% to 54%) or obtaining appropriate housing (24% to 37%). Changes in knowledge regarding completion of forms for patients seeking government benefits increased (42% to 62%).

Legal Assistance to Medical Patients (LAMP)

The Legal Assistance to Medical Patients (LAMP) program is a collaboration between Legal Services of New Jersey and Newark Beth Israel Medical Center (NBIMC) medical and pediatric residency programs. In its first year, the LAMP program received 175 referrals, leading to 100 active cases, the majority from internal medicine. The most common issues were disability-related income supports, Medicaid and other public benefits, housing, family law, immigration and guardianship. Approximately 20 teaching sessions were conducted during the year on topics similar to those developed by LegalHealth (see table).

During development of the LAMP program, 114 residents responded to a survey regarding their knowledge of and attitudes about legal issues among their patients. While 57% felt it was likely that “free access to an attorney can help patients” in their practice, only 33% felt “comfortable raising and discussing legal issues” with them. Follow-up survey data are not yet available, but referrals from residents have steadily increased over the year, and many residents commented on feeling relief knowing that they have this resource available for their patients.

MLP | Boston

Medical-Legal Partnership | Boston12 is the founding site of the National MLP Network. It serves more than 1,500 patients annually at Boston Medical Center (BMC) and six community health centers, and teaches residents, students and health care providers in internal medicine, geriatrics, oncology, infectious disease, family medicine and pediatrics (Table 1). Three examples of innovative curricula developed by MLP | Boston are described below.

Leadership in Advocacy Block (LAB)

Piloted during the 2008–09 academic year, the Leadership in Advocacy Block (LAB) is a 4-week course required of Boston University Primary Care Training (PCT) Program interns in Internal Medicine. Beginning in 2009–10, LAB also will be offered to Boston University School of Medicine fourth year students and all PCT medical residents.

The LAB has four components:

Clinical experiences with vulnerable populations, such as those who are homeless, transgender and undergoing methadone treatment;

Didactic sessions focused on the legislative process, media advocacy and physicians’ role in advocacy at the individual and systemic levels;

Community exposures such as tours of homeless shelters, urban neighborhoods, the state house and housing court;

Project work to address a socially caused health disparity of their choice, such as methadone treatment in prison, access to alternative medicine and the role of physicians in palliative care.

The five interns gave the rotation 5 out of 5 points, with more formal evaluation occuring over the next year. Qualitative feedback included “I feel much more encouraged in my ability as an MD to make changes.” The residency director now views this as “an essential component of internal medicine training” and is investing in further in-depth evaluation.

Advocacy Boot Camps

On a quarterly basis, MLP | Boston offers Advocacy Boot Camp (ABC), a 3-h advocacy training session for physicians and allied health providers. CME credits, including risk management, and social worker credits are offered. Topics reflect all I-HELPSM areas.

In 2008, 76 (84%) of 90 participants completed evaluations. Sixty-seven of 76 (89%) indicated that they would make changes in their practice after attending the session. One example is the training on custody, paternity, birth certificates and domestic violence; all 29 people attending returned evaluations. Twenty-four of 27 (83%) reported they planned to make changes to their practice after training. Twenty-eight (97%) participants reported they could “screen” for two unmet basic needs after training.

Poverty Simulation

During resident orientation at the Boston Combined Residency in Pediatrics (BCRP), MLP | Boston facilitates a 2-h Poverty Simulation for 35 interns, and this will be conducted with internal medicine in May 2010. The Poverty Simulation was developed by the Missouri Association for Community Action to educate about the day-to-day realities of poverty.13 During four 15-min sessions, participants assume roles representing 4 weeks in the life of a low-income family. Activities include paying bills, buying food and working. This is followed by a reflection session to discuss the meaning and relevance to medical practice. Nineteen residents evaluated this exercise after participating in 2008; 74% strongly agreed and 21% somewhat agreed the experience helped them understand poverty. All participants agreed “This experience has helped me better understand how poverty can affect health” (42% strongly, 58% somewhat).

Peninsula Family Advocacy Program (FAP)

Established in 2004, Peninsula Family Advocacy Program (FAP) is a collaboration among Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital at Stanford, Ravenswood Family Health Center in East Palo Alto, San Mateo Medical Center and its affiliated clinics and the Legal Aid Society of San Mateo County. In 2008, FAP provided advice, representation or referrals to approximately 280 individuals and families.

An evaluation of pediatric interns was conducted from 2005 to 2007. Interns were evaluated during their community advocacy block and received didactic training following I-HELP training topics (Table 1). Sixty interns completed pre-surveys prior to training; 19 completed post-surveys via SurveyMonkey online. One example of the evaluation showed intern attitudes to legal screening for needs improved, as fewer providers reported concerns about making patients “nervous” with legal questions (from 38% to 21%).

In 2007, FAP developed an interdisciplinary course for law and medical students: “Medical-Legal Issues in Children’s Health.” Annually, ten medical, law and social work students learn about the legal basis for social determinants of health and advocacy skills as they impact on the individual and policy level. The course is structured around a series of lectures and discussions with a service learning component including collaborative case and policy work. Qualitative feedback includes: course does a whole lot to empower medical students to effective action and advocacy; seeing how lawyers prioritize components of a patient case differently than physicians gave me a new perspective on how I might approach a patient; offers an initial channel to begin conversation on how we can work together.

DISCUSSION

Social causes of health disparities can be difficult to teach to trainees and harder to address in medical practice. Medical-legal partnership (MLP) has been cited as an innovation to address unmet needs, such as food, housing and income, that can drive disparities. While this innovation originated and has grown in pediatrics, it is extremely relevant to internal medicine practice and training, particularly given the fact that many training programs serve largely indigent adult patient populations, whether urban or rural. Medical-legal partnerships have a particularly powerful role in the management of chronic disease in the context of multidisciplinary medical homes.

Through MLP curricula, residents, faculty, medical students and other providers learn not only to screen and diagnose, but also learn to refer patients to lawyers as part of the health care team. These lawyers can “treat” or solve complicated social issues, and can teach how key legal rights are to health. This new curricular approach can be integral to teaching systems-based approaches to care and professionalism.14 As internal medicine creates new medical homes, integrating lawyers can be an important facet of comprehensive primary care and management of chronic diseases. MLPs can help patients with chronic disease maintain a treatment regimen, reduce stress and improve quality of life.15

While MLP education programs across the country are receiving high ratings from trainee evaluation, more systematic evaluations assessing the impact on knowledge and clinical behavior are being developed. The National Center for Medical Legal Partnership offers resources in the design, implementation and evaluation of curricula (www.medical-legalpartnership.org).

As the report of Robert Wood Johnson’s Commission to Build a Healthier America states, “Clinicians are in a unique position to identify vulnerable patients. In partnership with programs and agencies that offer legal or social services counseling and advocacy, health care providers can help patients address homelessness, help paying for groceries and meals, utility bills, and landlord remediation of safety and health problems in the home. Examples of programs that connect patients with services and resources in the greater community are the Medical-Legal Partnership.” General internists can be natural leaders in this educational innovation to teach and treat social determinants of health.

Acknowledgments

Megan Sandel and Pamela Tames would like to acknowledge funding from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation and Atlantic Philanthropies. Funding for the creation of LegalHealth’s curriculum was from the Jacob and Varleria Langeloth Foundation. Funding for the LAMP program is from the Healthcare Foundation of New Jersey, Robert Wood Tohusan Foundation and the Merck Foundation. FAP is supported by Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital at Stanford, Bernard A. Newcomb Foundation, The California Endowment, First Five San Mateo County, Philanthropic Ventures Foundation, Equal Justice Works, United Health Foundation and the National Center for Medical-Legal Partnership.

Conflicts of Interest The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

References

- 1.Zuckerman B, Sandel M, Lawton E, Morton S. Medical-legal partnerships: transforming health care. Lancet. 2008;372:1615–1617. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61670-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Center for Medical-Legal Partnership. Available at: http://www.medical-legalpartnership.org/. Accessed June 30, 2009.

- 3.Zuckerman B, Lawton E, Morton S. From principles to practice: moving from human rights to legal rights to ensure child health. Arch Dis Child. 2007;92(2):100–101. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.110361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zuckerman B, Sandel M, Smith L, Lawton E. Why pediatricians need lawyers to keep children healthy. Pediatrics. 2004;114(1):224–228. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.1.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Legal Services Corporation, Documenting the Justice Gap in America. 2005 Available at: http://www.lsc.gov/justicegap.pdf. Accessed December 15, 2009.

- 6.Williams DR, Sternthal M, Wright RJ. Social determinants: taking the social context of asthma seriously. Pediatrics. 2009;123:S174–S184. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2233H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Commission to Build a Healthier America. 2009. Beyond Health Care: New Directions for a Healthier America: 108. Available at: http://www.commissiononhealth.org/Report.aspx?Publication=64498. Accessed December 15, 2009.

- 8.Wise M, Marple K, De Vos E, Sandel M, Lawton E. Medical-Legal Partnership Network Annual Partnership Site Survey. Boston, Medical Legal Partnership Boston. 2009. Available at: http://www.medical-legalpartnership.org/sites/default/files/page/2009%20MLP%20Site%20Survey%20Report.pdf. Accessed December 15, 2009.

- 9.Kenyon C, Sandel M, Silverstein M, Shakir A, Zuckerman B. Revisiting the social history for child health. Pediatrics. 2007;120(3):e734–e738. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.LegalHealth. Available at http://www.legalhealth.org/. Accessed December 15, 2009.

- 11.Fleishman SB, Retkin R, Brandfield J, Braun V. The attorney as the newest member of the cancer treatment team. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(13):2123–2126. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.04.2788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Medical-Legal Partnership | Boston. Available at: http://www.mlpboston.org/. Accessed December 15, 2009.

- 13.Missouri Association for Community Action. “Community Action Poverty Simulation ”. Available at: http://www.communityaction.org/Poverty%20Simulation.aspx. Accessed December 15, 2009.

- 14.ACGME Outcome Project. 2007. “Common Program Requirements: General Competencies”. Available at: http://www.acgme.org/outcome/comp/GeneralCompetenciesStandards21307.pdf. Accessed December 15, 2009.

- 15.Fleishman SB, Retkin R, Brandfield J, Braun V. The attorney as the newest member of the cancer treatment team. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(13):2123–2126. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.04.2788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]