Abstract

Beneficial bacteria interact with plants by colonizing the rhizosphere and roots followed by further spread through the inner tissues, resulting in endophytic colonization. The major factors contributing to these interactions are not always well understood for most bacterial and plant species. It is believed that specific bacterial functions are required for plant colonization, but also from the plant side specific features are needed, such as plant genotype (cultivar) and developmental stage. Via multivariate analysis we present a quantification of the roles of these components on the composition of root-associated and endophytic bacterial communities in potato plants, by weighing the effects of bacterial inoculation, plant genotype and developmental stage. Spontaneous rifampicin resistant mutants of two bacterial endophytes, Paenibacillus sp. strain E119 and Methylobacterium mesophilicum strain SR1.6/6, were introduced into potato plants of three different cultivars (Eersteling, Robijn and Karnico). Densities of both strains in, or attached to potato plants were measured by selective plating, while the effects of bacterial inoculation, plant genotype and developmental stage on the composition of bacterial, Alphaproteobacterial and Paenibacillus species were determined by PCR-denaturing gradient gel-electrophoresis (DGGE). Multivariate analyses revealed that the composition of bacterial communities was mainly driven by cultivar type and plant developmental stage, while Alphaproteobacterial and Paenibacillus communities were mainly influenced by bacterial inoculation. These results are important for better understanding the effects of bacterial inoculations to plants and their possible effects on the indigenous bacterial communities in relation with other plant factors such as genotype and growth stage.

Keywords: PCR-DGGE, Methylobacterium, Paenibacillus, Multivariate analysis, Bacterial inoculation

Introduction

Species composition in bacterial communities associated with plants fluctuates qualitatively and quantitatively depending on the growth stage of the host plant. A wide diversity of bacteria can interact with plants, resulting in a wide spectrum of bacterial communities that differ per plant species and that contribute differently to plant development and health (Hallmann et al. 1997). Interactions between bacteria and plants mainly occur at two locations, near or at the surface of roots (rhizosphere communities) and inside plants and/or plant roots (endophytic communities). The rhizosphere is defined as the region in the soil that is mostly influenced by roots exudates, mucilage from root caps and sloughed-off cells however, the definition of the rhizosphere may be broader as it would also include the roots themselves (Hartmann et al. 2008). Although the physical limits of this environment are not always clear, it must be considered as a hot spot for bacterial interaction with plants as often demonstrated by the occurrence of higher bacterial densities (De Boer et al. 2006). The endophytes are defined as a group of bacteria that can be isolated from surface-disinfected plants that do not visibly harm plants (Hallmann et al. 1997), neither these bacteria evoke the development of internal or external structures in plant roots, like in the cases of rhizobia and mycorrizal fungi interactions with plants (Azevedo et al. 2000; Hardoim et al. 2008). There is no single plant species on earth that is devoid of endophytes, and involved bacterial groups have different kinds of interactions with plants (Rosenblueth and Martinez-Romero 2006). Some of these interactions can be nutrient acquisition for plants, induction of systemic resistance and suppressive activities against organisms that cause diseases and pests in plants. In fact, endophytic bacteria are good candidates for bacterial inoculations of plants in which they act as plant-growth promoting agents. However, for that purpose only limited information is available on the effects of bacterial inoculation on indigenous microbial communities associated with plants, especially in relation with other plant-related and environmental parameters.

Different biotic and abiotic factors influence plant development and the composition of bacterial communities associated with them (Kozdroj and van Elsas 2000; Marschner and Baumann 2003). The composition of bacterial communities associated with plants differ per plant species (Salles et al. 2004), cultivar type (Dunfield and Germida 2004; Kuklinsky-Sobral et al. 2004) and even subtle differences in species compositions were found between transgenic plants and their isogenic non-modified parent lines (Andreote et al. 2008, 2009a, b; Rasche et al. 2006). When bacteria are introduced into plants, they may survive and proliferate in the plant host and may even induce shifts in microbial communities of its natural or newly inoculated host species (Andreote et al. 2009c, 2004; Khan et al. 2007). Effects of bacterial inoculation on bacterial community composition in plants are seldomly studied and most likely these effects coincide with other effects like the ones caused by environmental and plant-related changes and these factors all together determine the final bacterial community composition in plants.

Multivariate analysis of PCR-DGGE fingerprints is an approach that is commonly used for calculation of the impacts of environmental and plant-related factors on microbial community composition in ecosystems (Ramete 2007). This approach was applied for the first time in the analysis of factors influencing bacterial communities in soils (Steenwerth et al. 2002) and later in the analyses of effects caused by field history and plant growth on the structure of Burkholderia spp. in the rhizosphere (Salles et al. 2004), and on the presence or absence of roots on the Pseudomonas spp. community composition in soils (Costa et al. 2006). Recently, the effects of pH, fertilization and soil storage on the structure of bacterial communities in soil were calculated by multivariate analysis (Tzeneva et al. 2009).

The aim of this study is to calculate the effects of inoculation, plant genotype and growth stage on the composition of plant-associated communities using multivariate analysis. This information will be important for further research on the development of bacterial inoculation approaches based on endophytic isolates.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and selection of rifampicin resistant derivatives

The strains used in this study were previously isolated from surface-sterilized plants and were identified on the basis of near-full 16S rRNA gene sequences as Paenibacillus sp. (strain E119) and Methylobacterium mesophilicum (strain SR1.6/6). Strain E119 was obtained from the bacterial collection at Plant Research International (Wageningen, The Netherlands). This strain was originally isolated as an endophyte from surface-sterilized potato plants. Strain SR1.6/6 was obtained from the collection of the Microbial Genetics group, at ESALQ/USP (Piracicaba, Brazil). This strain was originally isolated as an endophyte from surface-sterilized citrus plants (Araújo et al. 2002).

For enrichment of rifampicin resistant derivatives, cells of both strains were cultured to a density of about 109 CFU/ml in liquid TSB medium. Cell pellets from 10 ml cultures were harvested by centrifugation at 10,000g for 5 min and were suspended in 100 μl of sterilized water and spread plated onto TSA (TSB with 1.2% agar) amended with 50 μg/ml rifampicin. After 3 days of incubation at 28°C, colonies were picked from these plates and streaked to purity. DNA extracts made from wild type and rifampicin resistant cells of both strains were PCR amplified using the BOXA1R primer (Louws et al. 1999). Those mutants showing an identical BOX fingerprint pattern as their respective parent (rifampicin sensitive) strain were selected and these mutants were denoted as E119rp and SR1.6/6rp. The stability of the rifampicin resistance marker was evaluated by cultivation of mutants without antibiotics followed by plating on TSA either and not amended with 50 μg/ml rifampicin.

Potato plant growth and plant inoculation

Potato plants were used in this study due to its importance as Dutch and Brazilian crop, the facilities to work with these plants at the Plant Research International (Wageningen, The Netherlands) and due to the amount of knowledge on the microbial communities associated to this crop (Rasche et al. 2006; van Overbeek and van Elsas 2008). Plant inoculations were performed with the original strains and with spontaneous rifampicin resistant derivatives thereof. Three cultivars of potato plants were used: Eersteling, Karnico and Robijn. These cultivars all originated from The Netherlands, and main characteristics of each cultivar are presented in Table 1. Major differences between cultivars were genotype, periods in flowering and tuber development and resistance to plant diseases.

Table 1.

Characteristics of potato cultivars used in this study

| Eersteling | Robijn | Karnico | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Origin | The Netherlands | The Netherlands | The Netherlands |

| Pedigree | Mutant from Duke of York | Rode Star × Preferent | Astarte × SVP AM 66 42 |

| Period for maturity | Precocious | Very late | Late |

| Usage of plants | Feeding | Starch and feeding | Starch and dry organic matter |

| Resistance to diseases | Low | Low | High |

Data were retrieved from www.davesgarden.com, www.europotato.org and http://www.dpw.wau.nl

For plant growth, in vitro transplants were grown for 1.5 months in MS agar medium (Murashige and Skoog 1962) at a 16 h photoperiod and a temperature range of between 25 and 28°C before experimentation. For introduction into plants, cells of strains E119rp and SR1.6/6rp, grown in liquid TSB medium amended with 50 μg/ml rifampicin, were harvested by centrifugation at 10,000g for 5 min. Cell suspensions made in sterilized water and reaching densities of about 106 CFU/ml were used for all plant treatments. Therefore, roots of in vitro transplants were immersed in the bacterial cell suspension for 1 h and then treated transplants were placed into 2 l pots filled with potting soil. Control plants were similarly treated but then roots were immersed in sterilized water only. Pots with plants were transferred to the greenhouse and were daily supplied with water to compensate for water loss. The temperature was set between 22 and 25°C using a 12 h photoperiod. During the first 5 days, plants were covered with plastic bags to avoid dehydration.

Bacterial isolation from inoculated potato plants

Plant colonization by strains E119rp and SR1.6/6rp was determined one and two months after plant inoculation, corresponding to the juvenile (growth stage 1) and the flowering growth stages (growth stage 6), according to the potato development system described by Hack et al. (1993). In each of the samplings, four replicates per treatment were used. For bacterial isolation, roots and stem parts were separated from plants that were taken out of the pots. For bacterial isolation from roots, the entire root system free of potting soil, by rinsing in fresh tap water, was used (encompassing rhizoplane and endophytic bacteria), whereas for assessment of endophytic colonization by both strains, stem parts of about 1–2 cm above soil level (stem base) were used. Stem base samples were surface-sterilized by immersion in 70% ethanol for 1 min followed by immersion in 2% sodium hypochlorite for 3 min and finalized by two times rinsing in sterile water.

All root and surface-sterilized stem base samples were first weighed and then transferred to sterile plastic bags filled with 3 ml of sterile deionized water. Roots and stems were homogenized by hammering and resulting homogenates were used for plating and DNA extractions. For plating, serial tenfold dilutions made in sterile tap water were plated onto 5% TSB agar medium supplemented with 0.1% glucose, either or not amended with 50 μg/ml rifampicin. Plates were incubated at 25°C and daily monitored during 5 days for colony development. Total heterotrophic CFU numbers were determined from agar medium without rifampicin, whereas CFU numbers of the introduced rifampicin strains were determined on the same plates with rifampicin. For the last, the identity of the colonies were checked by BOX-PCR fingerprint comparisons with respective wild type strains.

DNA extraction from roots and surface-sterilized stem samples and PCR-DGGE analyses

Aliquots of 500 μl of root and surface-sterilized stem homogenates were submitted to DNA extraction using the DNeasy Plant Mini for DNA Isolation kit (Qiagen, Germany) and DNA extractions were executed according to the manufacturer instructions. The DNA yield and quality were checked by agarose gel electrophoresis, run at a voltage of 5 V/cm, in a 1.0% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide and DNA was visualized under UV.

Bacterial PCR-DGGE analysis was performed using the primers U968-GC and R1387 (Heuer et al. 1997). In order to avoid chloroplast competition during PCR amplification, a preceding amplification step was performed using primer 799F in combination with 1492R (Chelius and Triplett 2001). Alphaproteobacterial PCR-DGGE was performed using the system described by Gomes et al. (2001) and Paenibacillus PCR-DGGE according to the system described by Da Silva et al. (2003). All PCRs were performed with an initial amount of approximately 10 ng of extracted DNA.

DGGE was performed as described previously (Muyzer et al. 1993) using the Ingeny phorU2 apparatus (Ingeny International, Goes, The Netherlands). PCR samples were loaded onto 6% (w/v) polyacrylamide gels in 0.5X TAE buffer. Polyacrylamide gels were made with denaturing gradients ranging from 45 to 65%, run for 16 h at 100 V at 60°C, after which they were soaked for 1 h in SYBR Green I nucleic acid stain (1:10 000 dilution; Molecular Probes, Leiden, the Netherlands) and visualized under UV. PCR-DGGE fingerprints were digitized for later analyses.

One contiguous DGGE band was selected for identification. This band was sliced out from the gel, soaked in sterile water for 1 h to elute DNA from the gel and submitted for further PCR amplification using primers R1387 and U968-GC (Heuer et al. 1997). The resulting PCR amplicon was loaded onto fresh DGGE gels to check for band purity and co-migration with the selected band in the community fingerprint. Thus selected amplicon was then purified and subjected for sequencing using the facilities of Greenomics (Plant Research International, Wageningen, NL). The generated sequence was deposited at GenBank under the accession code GU176321.

PCR-DGGE fingerprint analyses

Digitized PCR-DGGE fingerprints were analyzed using GelComparII software (Applied Maths, Belgium). Individual bands in fingerprints were normalized on the basis of three marker lanes loaded on different positions in the gel and band intensity relative to the total intensity per lane were calculated for each fingerprint. Thus obtained output was used for further cluster and multivariate analyses. Clustering analysis was performed using the UPGMA algorithm and the Pearson correlation index was calculated from the fingerprints. The correlations between individual bands in PCR-DGGE fingerprints and environmental variables (bacterial inoculation, plant genotype and stage of development) were determined by multivariate analysis using Canoco for Windows 4.5 software (Biometris, Wageningen, The Netherlands), following the same procedures as described before (Andreote et al. 2009c; Ramete 2007; Ter Braak and Šmilauer 2002).

Briefly, detrended correspondence analysis (DCA) was performed first to calculate gradient distribution of the ‘species’ in the PCR-DGGE fingerprints. At normal distribution of ‘species’ in the fingerprints (gradient in the first axis > 4.0), data were analyzed by canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) and at linear distributions (gradient in the first axis < 4.0) data were analyzed by Redundancy Analysis (RDA). For statistical analyses of correlations between ‘species’ and ‘environmental’ factors a MonteCarlo permutation test was included, based on 499 unrestricted permutations. In addition to P-values, values of Lambda 1 were obtained as a quantification of the amount of variance explained by each environmental factor.

Results and discussion

Beneficial bacterial populations occur in plants as natural components of the indigenous plant-associated bacterial community, but they can also be introduced into plants causing direct or indirect effects on plant metabolism. Bacterial inoculation of plants may lead to shifts in the composition of plant-associated bacterial communities (Andreote et al. 2006; Viebahn et al. 2005) and this on its turn may also lead to differences in plant metabolism. Community shifts upon inoculation with the endophytic M. mesophilicum SR1.6/6 strain has been demonstrated before in periwinkle plants (C. roseus) (Andreote et al. 2006). On the other hand, differences in plant metabolism can also affect the composition of associated bacterial communities which are expected to occur in different cultivars of the same plant species and during plant growth. Here we found clear effects of inoculation, plant genotype and plant growth stage on the structure of naturally occurring plant-associated bacterial communities.

Potato plant colonization by strains E119rp and SR1.6/6rp

No significant differences in the total number of heterotrophic bacteria were found between plants of the different cultivars at the roots or inside surface-sterilized stems (endosphere). Only at one occasion a significant difference was found in the number of endophytic bacteria which was lower in plants of cultivar Eersteling than in those of the other cultivars at the second sampling (Tables 2 and 3). Rifampicin-resistant derivatives of strain E119 and SR1.6/6 were only recovered from inoculated plants and CFU numbers were always higher in the roots than in the surface-sterilized stems. Also, the introduced populations appeared to be stable during plant growth, although numbers had decreased at the second sampling when plants were in the flowering stage (Tables 2 and 3). In general, densities of strain SR1.6/6rp cells inside, or attached to plants were higher than those of strain E119rp (Tables 2 and 3). Rifampicin resistance marker stability tests with derivatives of both strains did not reveal any loss of this phenotype during growth in liquid medium and therefore it seems unlikely that observed lower inoculant strain numbers in flowering plants resulted from marker instability. However, marker instability has been found before in other plant-bacterium combinations (Chen et al. 1995; McInroy et al. 1996) and it can not be totally excluded that under conditions specifically prevailing in potato plants marker loss in one or both strains might have occurred.

Table 2.

Total heterotrophic bacterial and target strains (CFU numbers) in roots samples

| Cultivars | Inoculation | Total community | Population of target bacteria | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 month after inoculation | 2 months after inoculation | 1 month after inoculation | 2 months after inoculation | ||

| Eersteling | Control | 7.83 ± 0.10 | 7.12 ± 0.19 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| E119 | 7.93 ± 0.24 | 6.77 ± 0.15 | 1.59 ± 1.09 | 2.97 ± 0.22 | |

| SR1.6/6 | 7.71 ± 0.44 | 7.11 ± 0.35 | 4.06 ± 0.17 | 3.76 ± 0.56 | |

| Robijn | Control | 7.51 ± 0.31 | 7.06 ± 0.28 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| E119 | 7.90 ± 0.19 | 6.79 ± 0.16 | 2.48 ± 0.75 | 2.59 ± 0.58 | |

| SR1.6/6 | 7.96 ± 0.21 | 7.08 ± 0.29 | 3.88 ± 0.13 | 4.13 ± 0.46 | |

| Karnico | Control | 8.19 ± 0.40 | 7.27 ± 0.49 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| E119 | 7.90 ± 0.25 | 6.89 ± 0.39 | 3.45 ± 0.34 | 2.04 ± 1.40 | |

| SR1.6/6 | 7.94 ± 0.21 | 7.12 ± 0.52 | 4.40 ± 0.18 | 4.01 ± 0.20 | |

Average values from four plants are calculated from Log-transformed CFU numbers and expressed per g plant and standard deviation are indicated

Table 3.

Total heterotrophic bacterial and target strains (CFU numbers) in endophytic samples

| Cultivars | Inoculation | Total community | Population of target bacteria | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 month after inoculation | 2 months after inoculation | 1 month after inoculation | 2 months after inoculation | ||

| Eersteling | Control | 6.03 ± 0.35 | 3.90 ± 0.52 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| E119 | 5.08 ± 0.23 | 4.30 ± 0.14 | 0.22 ± 0.27 | 0.33 ± 0.66 | |

| SR1.6/6 | 5.97 ± 0.60 | 4.52 ± 0.46 | 2.34 ± 0.46 | 1.11 ± 0.65 | |

| Robijn | Control | 6.88 ± 0.06 | 5.29 ± 0.91 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| E119 | 5.38 ± 1.28 | 4.86 ± 0.24 | 0.66 ± 0.58 | 1.34 ± 0.91 | |

| SR1.6/6 | 4.84 ± 0.59 | 4.67 ± 0.92 | 1.82 ± 0.67 | 0.95 ± 1.00 | |

| Karnico | Control | 5.37 ± 0.75 | 5.13 ± 0.70 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| E119 | 4.93 ± 0.54 | 4.93 ± 1.22 | 0.59 ± 0.79 | 1.97 ± 1.61 | |

| SR1.6/6 | 4.99 ± 1.21 | 4.37 ± 1.62 | 0.86 ± 0.85 | 0.68 ± 0.82 | |

Average values from four plants are calculated from Log-transformed CFU numbers and expressed per g plant and standard deviation are indicated

Endophytic colonization of Karnico plants by strain SR1.6/6rp was log 0.86 CFU per g plant, whereas in Eersteling and Robijn plants values were higher, respectively log 2.34 and log 1.82 CFU per g plant. Possibly, defense mechanisms towards SR1.6/6rp cells in Karnico plants is somewhat higher than in plants of the other two cultivars which may reflect the higher resistance level against invading plant pathogens in Karnico plants. Another option is that lower SR1.6/6rp cell numbers is caused by a stronger competition with the indigenous plant-associated microbial community which differs between cultivars (see later). Strain E119rp CFU numbers in the endosphere of potato plants of all three cultivars at flowering were between 0.22 and 0.66 CFU per g plant and these numbers were not in line with the CFU numbers found for strain SR1.6/6rp. It is clear that selective processes present in potato plants are different for the two introduced bacterial strains.

PCR-DGGE detection of strains E119rp and SR1.6/6rp in potato plants

In bacterial-, alphaproteobacterial- and Paenibacillus PCR-DGGE fingerprints from strain E119rp- and SR1.6/6rp-inoculated and control plants, no bands were found that co-migrated with bands made from pure culture DNA extracts of both strains. This indicates that strain E119rp- and SR1.6/6rp-cell numbers in roots and endospheres are below the limits of detection for all applied PCR-DGGE systems. This in contrary to Pseudomonas putida strain P9 which was always present as a root-colonizing and endophytic bacterium in plants of the same cultivars at the young and flowering growth stages (Andreote et al. 2009d). It was estimated that bacterial populations contributing to fractions of 1% or higher of the total bacterial community are detectable by PCR-DGGE (Oros-Sichler et al. 2007). Considering this estimation, it is clear that the two introduced populations represent only minor fractions (below 1%) of the total root-associated and endophytic communities present in potato plants. However, the observed low density levels of the two introduced populations do not exclude any possible effects on the composition of the indigenous microbial community associated with potato plants, and possibly also not on plant metabolism.

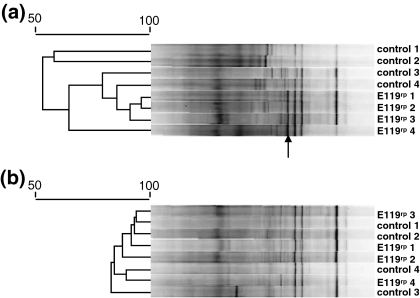

PCR-DGGE fingerprints of SR1.6/6rp- and E119rp-treated and control plants made with all three systems were visually distinguishable from each other and this observation was later confirmed by multivariate analysis on the same fingerprints. In Paenibacillus-specific PCR-DGGE fingerprints made of strain E119rp-treated roots of Robijn plants, a conspicuous band was observed that was absent in corresponding fingerprints of control plants (Fig. 1). Sequence analyses of this band revealed that it was affiliated with an uncultured Paenibacillus sp. (96% of similarity). This conspicuous band was only present in PCR-DGGE fingerprints of young plants and not in that of flowering plants. There may be an interaction between this species and the introduced strain E119rp at, or inside the roots resulting in transient growth stimulation upon inoculation with strain E119rp cells. Interestingly, a phylogenetically close relative of strain E119rp, Paenibacillus illinoisensis, was able to induce systemic resistance in pepper plants (Jung et al. 2006). Possibly, strain E119rp has a similar effect in potato plants and may stimulate or suppress bacterial groups associated to the root system and interior parts of potato plants.

Fig. 1.

Comparison between PCR-DGGE fingerprints for Paenibacillus sp. made from Robijn roots from juvenile (1-month old) (a) and flowering (two-months old) (b) plants. Dendrograms were made by Pearson correlation and arrow indicates the conspicuous band only present in E119rp inoculated juvenile plants

Correlation between environmental variables and the composition of bacterial communities

DCA analysis on species distribution in bacterial PCR-DGGE fingerprints revealed gradient lengths of between 4.61 and 4.72 in size justifying the use of canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) for these fingerprints, whereas for Alphaproteobacterial and Paenibacillus PCR-DGGE fingerprint gradient lengths were between 2.04 and 3.32, justifying the use of redundancy analysis (RDA) for the latter ones (Table 4).

Table 4.

Statistical parameters calculated by multivariate analyses with inclusion of a Monte Carlo permutation test of bacterial, alphaproteobacterial and Paenibacillus PCR-DGGE fingerprints

| Targeted community | Plant Niche | Quantitative and nominal variables | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient | Analysis | Months | Karnico | Eersteling | Robijn | SR1.6/6rp | E119rp | ||

| Bacteria | Roots | 4.61 | CCA | 0.64* | 0.48* | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.05 |

| Endophytes | 4.72 | CCA | 0.72* | 0.50* | 0.27* | 0.33* | 0.09 | 0.08 | |

| Alphaproteobacteria | Roots | 2.04 | RDA | 0.04* | 0.47* | 0.20* | 0.11 | 0.03 | ND |

| Endophytes | 3.32 | RDA | 0.15* | 0.17* | 0.32* | 0.13 | 0.06 | ND | |

| Paenibacillus spp. | Roots | 2.98 | RDA | 0.06* | 0.17* | 0.52* | 0.13* | ND | 0.02* |

| Endophytes | 3.17 | RDA | 0.05* | 0.12* | 0.32* | 0.40* | ND | 0.01 | |

Values for Lambda 1 indicate the amount of variance explained by each individual environmental parameter

*Variables statistically significant with P < 0.05 according to the MonteCarlo permutation test

ND non-determined values

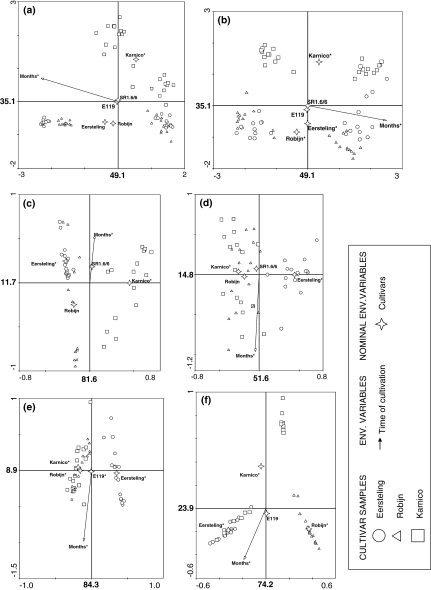

Plant growth stage was the most important factor influencing the composition of the bacterial communities in roots and surface-sterilized stems of potato plants as demonstrated by the closest correlation of this vector with the first axis of the ordination diagram (Fig. 2). This effect was significant and Lambda 1 values were between 0.64 and 0.72 (Table 4), demonstrating that most of the variance in bacterial species composition can be explained by plant growth. Cultivar effects were overall more correlated with the second axis and the bacterial species composition in the roots of Karnico plants were more distinct than in those of the other two cultivars, whereas for the endophytes bacterial species composition of all three cultivars were clearly distinguishable from each other (Fig. 2). No clear effect of plant inoculation on bacterial species composition was found in PCR-DGGE fingerprints made from all root and surface-sterilized stem samples.

Fig. 2.

Ordination diagrams made by multivariate analysis of PCR-DGGE fingerprints made with bacterial, alphaproteobacterial and Paenibacillus primers. Separate analysis were performed for DGGE patterns obtained with primers for the domain Bacteria (a, b), Alphaproteobacteria (c, d) and Paenibacillus spp. (e, f). Also different communities were evaluated individually for roots (a, c, e) and endophytic (b, d, f). All environmental variables influencing in each analysis are presented, however, only those with significant effect (P < 0.05), according to the Monte Carlo permutation test, is marked with *. Values represent the percentage of the correlation species-environmental variable explained in each axis

The contribution of the same factors on alphaproteobacterial and Paenibacillus communities tended to be different from the bacterial ones as cultivar type and plant inoculation were more correlated to the first, and growth stage to the second axis in the ordination diagram. The alphaproteobacterial species compositions in roots of the different cultivars were significantly different from each other and also were the ones of both plant growth stages. The endophytic alphaproteobacterial species composition was also different between cultivars and between both plant growth stages. No significant differences in alphaproteobacterial species composition were found in roots and in surface-sterilized stems between SR1.6/6rp- and E119rp-treated and control plants. The Paenibacillus species compositions in roots of potato plants were significantly different between both growth stages, between the three cultivar types and between ER119rp-treated versus SR1.6/6rp and control plants. The endophytic Paenibacillus species composition was significantly different between both growth stages and between the three cultivar types, but not between control and inoculated plants.

Clear effects of plant growth stage, cultivar type and occasionally of plant treatment on bacterial, Alphaproteobacterial and Paenibacillus species composition at the roots and inside plants was demonstrated. Bacteria used for inoculation of potato plants in this study were selected for their possible interaction with plants. Strain SR1.6/6 belong to the group of Methylobacterium species and members of this group are known for their endophytic nature (Omer et al. 2004) and induction of systemic resistance in nuts and rice plants (Madhaiyan et al. 2006). However, the effect of inoculation of strain SR1.6/6 on the Alphaproteobacteria community composition was less clear than in other plant species (Andreote et al. 2006). This indicate that the effect of treatment with strain SR1.6/6 cells differ per plant species which possibly reflect the variation in defense mechanisms that might exist between plant species to ward off this, and possibly also other related bacterial species. Paenibacillus species are not so well known for their endophytic nature, but their role in the induction of systemic resistance in plants has been demonstrated before (Jung et al. 2006). Induced resistance may lead to enhanced plant defense activities towards particular groups of micro-organisms, explaining observed shifts in plant-associated bacterial communities upon inoculation of potato plants with strain E119 cells. Induction of systemic resistance in potato plants upon inoculation with cells of both strains was not demonstrated in this study, but will be investigated in future research in our laboratories.

Another important point concerning the differential effects of bacteria on the natural communities is related to the used systems. The stronger effect of Paenibacillus sp. inoculation on the plant might be simply due to the use of a narrower molecular method (based on the genus) than for Alphaproteobacteria (based on the class). Performing the same analyses with other bacterial groups could provide more support for our presented discussion. Although some tentative work have been made (Andreote et al. 2009b), an efficient system for detection of the genus Methylobacterium is not yet available for environmental samples.

In conclusion, the effect of bacterial treatment on the associated microbial community structure of potato plants was demonstrated for two taxonomically distinct bacterial groups. Shifts in plant-associated microbial communities can be an important side effect of bacterial treatments of plants, e.g. for biological control purposes. These effects have hardly been explored so far and need further attention in scientific literature. The results of this work will contribute to a better understanding about the performance of biological control agents in different agricultural crop systems.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Netherlands Genomics Initiative (Ecogenomics program) and the Dutch Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food quality (Knowledge-based funding program on sustainable agriculture, theme 4). We thank CAPES for the fellowship provided to F.D.A (process 2990/05-9).

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- Andreote FD, Gullo MJM, Lima AOS, Maccheroni W, Jr, Azevedo JL, Araujo WL. Impact of genetically modified Enterobacter cloacae on indigenous endophytic community of Citrus sinensis seedlings. J Microbiol. 2004;42:169–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreote FD, Lacava PT, Gai CS, Araújo WL, Maccheroni W, Jr, van Overbeek LS, van Elsas JD, Azevedo JL. Model plants for studying the interaction between Methylobacterium mesophilicum and Xylella fastidiosa. Can J Microbiol. 2006;52:419–426. doi: 10.1139/W05-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreote FD, Mendes R, Dini-Andreote F, Rossetto PB, Labate CA, Pizzirani-Kleiner CA, van Elsas JD, Azevedo JL, Araújo WL. Transgenic tobacco revealing altered bacterial diversity in the rhizosphere during early plant development. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 2008;93:415–424. doi: 10.1007/s10482-007-9219-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreote FD, Rossetto PB, Mendes R, Avila LA, Labate CA, Pizzirani-Kleiner AA, Azevedo JL, Araújo WL. Bacterial community in the rhizosphere and rhizoplane of wild type and transgenic eucalyptus. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;25:1065–1073. doi: 10.1007/s11274-009-9990-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andreote FD, Carneiro RT, Salles JF, Marcon J, Labate CA, Azevedo JL, Araújo WL. Culture-independent assessment of Alphaproteobacteria related to order Rhizobiales and the diversity of cultivated Methylobacterium in the rhizosphere and rhizoplane of transgenic eucalyptus. Microbial Ecol. 2009;57:82–93. doi: 10.1007/s00248-008-9405-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreote FD, Azevedo JL, Araújo WL. Assessing the diversity of bacterial communities associated with plants. Braz J Microbiol. 2009;40:417–432. doi: 10.1590/S1517-83822009000300001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreote FD, Araújo WL, Azevedo JL, van Elsas JD, Nunes da Rocha U, van Overbeek LS. Endophytic colonization of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) by a novel competent bacterial endophyte, Pseudomonas putida strain P9, and its effect on associated bacterial communities. Appl Environ Microb. 2009;75:3396–3406. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00491-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araújo WL, Marcon J, Maccheroni W, Jr, van Elsas JD, van Vuurde JWL, Azevedo JL. Diversity of endophytic bacterial populations and their interaction with Xylella fastidiosa in citrus plants. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:4906–4914. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.10.4906-4914.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo JL, Maccheroni Jr W, Pereira JO, Araújo WL (2000) Endophytic microorganisms: a review on insect control and recent advances on tropical plants. Elect J Biotechnol [online]. (http://www.ejbiotechnology.info/content/vol3/issue1/full/4/index.html). ISSN 0717-3458

- Chelius MK, Triplett EW. The diversity of archaea and bacteria in association with the roots of Zea mays L. Microbial Ecol. 2001;41:252–263. doi: 10.1007/s002480000087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Bauske EM, Musson G, Rodriguez-Kabana G, Kloepper JW. Biological-control of Fusarium-wilt on cotton by use of endophytic bacteria. Biol Control. 1995;5:83–91. doi: 10.1006/bcon.1995.1009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Costa R, Salles JF, Berg G, Smalla K. Cultivation-independent analysis of Pseudomonas species in soil and in the rhizosphere of field-grown Verticillium dahliae host plants. Environ Microbiol. 2006;8:2136–2149. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva KRA, Salles JF, Seldin L, van Elsas JD. Application of a novel Paenibacillus-specific PCR-DGGE method and sequence analysis to assess the diversity of Paenibacillus spp. in the maize rhizosphere. J Microbiol Meth. 2003;54:213–231. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7012(03)00039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Boer W, Kowalchuk GA, van Veen JA. ‘Root-food’ and the rhizosphere microbial community composition. New Phytol. 2006;170:3–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunfield KE, Germida JJ. Impact of genetically modified crops on soil- and plant-associated microbial communities. J Environ Qual. 2004;33:806–815. doi: 10.2134/jeq2004.0806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes NCM, Heuer H, Schonfeld J, Costa R, Mendonca-Hagler L, Smalla K. Bacterial diversity of the rhizosphere of maize (Zea mays) grown in tropical soil studied by temperature gradient gel electrophoresis. Plant Soil. 2001;232:167–180. doi: 10.1023/A:1010350406708. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hack H, Gall H, Klemke T, Klose R, Meier U, Stauss R, Witzenberger A. Phanologische entwicklungsstadien der Kartoffel (Solanum tuberosum L.) Nachrbl Dtsch Pflanzenschutzd. 1993;45:11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hallmann J, QuadtHallmann A, Mahaffee WF, Kloepper JW. Bacterial endophytes in agricultural crops. Can J Microbiol. 1997;43:895–914. doi: 10.1139/m97-131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hardoim PR, van Overbeek LS, van Elsas JD. Properties of bacterial endophytes and their proposed role in plant growth. Trends Microbiol. 2008;16:463–471. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann A, Lemanceau P, Prosser JI. Multitrophic interactions in the rhizosphere. Rhizosphere microbiology: at the interface of many disciplines and expertises. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2008;65:179. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2008.00558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuer H, Krsek M, Baker P, Smalla K, Wellington EMH. Analysis of actinomycete communities by specific amplification of genes encoding 16S rRNA and gel-electrophoretic separation in denaturing gradients. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3233–3241. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.8.3233-3241.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung WJ, Jin YL, Park RD, Kim KY, Lim KT, Kim TH. Treatment of Paenibacillus illinoisensis suppresses the activities of antioxidative enzymes in pepper roots caused by Phytophthora capsici infection. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2006;22:901–907. doi: 10.1007/s11274-006-9131-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khan MS, Zaidi A, Wani PA. Role of phosphate-solubilizing microorganisms in sustainable agriculture—a review. Agron Sustain Dev. 2007;27:29–43. doi: 10.1051/agro:2006011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kozdroj J, van Elsas JD. Response of the bacterial community to root exudates in soil polluted with heavy metals assessed by molecular and cultural approaches. Soil Biol Biochem. 2000;32:1405–1417. doi: 10.1016/S0038-0717(00)00058-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuklinsky-Sobral J, Araujo WL, Mendes R, Geraldi IO, Pizzirani-Kleiner AA, Azevedo JL. Isolation and characterization of soybean-associated bacteria and their potential for plant growth promotion. Environ Microbiol. 2004;6:1244–1251. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2004.00658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louws FJ, Rademaker JLW, de Bruijn FJ. The three Ds of PCR-based genomic analysis of phytobacteria: diversity, detection, and disease diagnosis. Ann Rev Phytopathol. 1999;37:81–125. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.37.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhaiyan M, Reddy BVS, Anandham R, Senthilkumar M, Poonguzhali S, Sundaram SP, Sa TM. Plant growth-promoting Methylobacterium induces defense responses in groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) compared with rot pathogens. Curr Microbiol. 2006;53:270–276. doi: 10.1007/s00284-005-0452-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marschner P, Baumann K. Changes in bacterial community structure induced by mycorrhizal colonisation in split-root maize. Plant Soil. 2003;251:279–289. doi: 10.1023/A:1023034825871. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McInroy JA, Musson G, Wei G, Kloepper JW. Masking of antibiotic-resistance upon recovery of endophytic bacteria. Plant Soil. 1996;186:213–218. doi: 10.1007/BF02415516. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T, Skoog F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bio assays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol Plant. 1962;15:473–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1962.tb08052.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muyzer G, Dewaal EC, Uitterlinden AG. Profiling of complex microbial populations by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis analysis of polymerase chain reaction amplified genes coding for 16S ribosomal RNA. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:695–700. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.3.695-700.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omer ZS, Tombolini R, Gerhardson B. Plant colonization by pink-pigmented facultative methylotrophic bacteria (PPFMs) FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2004;47:319–326. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6496(04)00003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oros-Sichler M, Costa R, Heuer H, Small K. Molecular fingerprinting techniques to analyze soil microbial communities. In: van Elsas JD, Jansson JK, Trevors JT, editors. Modern soil microbiology. 2. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2007. pp. 355–386. [Google Scholar]

- Ramete A. Multivariate analyses in microbial ecology. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2007;62:142–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2007.00375.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasche F, Hodl V, Poll C, Kandeler E, Gerzabek MH, van Elsas JD, Sessitsch A. Rhizosphere bacteria affected by transgenic potatoes with antibacterial activities compared with the effects of soil, wild-type potatoes, vegetation stage and pathogen exposure. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2006;56:219–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2005.00027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblueth M, Martinez-Romero E. Bacterial endophytes and their interactions with hosts. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2006;19:827–837. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-19-0827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salles JF, van Veen JA, van Elsas JD. Multivariate analyses of Burkholderia species in soil: effect of crop and land use history. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:4012–4020. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.7.4012-4020.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steenwerth KL, Jackson LE, Calderon FJ, Stromberg MR, Scow KM. Soil microbial community composition and land use history in cultivated and grassland ecosystems of coastal California. Soil Biol Biochem. 2002;34:1599–1611. doi: 10.1016/S0038-0717(02)00144-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ter Braak CJF Šmilauer P (2002) CANOCO Reference Manual and CanoDraw for Windows User’s Guide: Software for Canonical Community Ordination (version 4.5). 500 pp

- Tzeneva VA, Salles JF, Naumova N, de Vos WM, Kuikman PJ, Dolfing J, Smidt H. Effect of soil sample preservation, compared to the effect of other environmental variables, on bacterial and eukaryotic diversity. Res Microbiol. 2009;160:89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Overbeek L, Van Elsas JD. Effects of plant genotype and growth stage on the structure of bacterial communities associated with potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2008;64:283–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2008.00469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viebahn M, Doornbos R, Wernars K, van Loon LC, Smit E, Bakker P. Ascomycete communities in the rhizosphere of field-grown wheat are not affected by introductions of genetically modified Pseudomonas putida WCS358r. Environ Microbiol. 2005;7:1775–1785. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]