Abstract

Although severe life stress frequently precipitates the onset of major depression, little is known about the basic nature of stressors in this general category of adversity and how exposure to different life events might be related to clinical aspects of the disorder. We addressed this issue by introducing, and examining the effects of, targeted rejection (TR), which involves the exclusive, active, and intentional social rejection of an individual by others. Twenty-seven adults with major depressive disorder were administered an interview-based measure of life stress. Severe life events that occurred prior to the onset of depression were subsequently coded as TR or as non-TR. Participants who experienced a pre-onset severe TR event became depressed approximately three times faster than did their non-TR counterparts. These findings highlight the potential importance of TR as a marker of hastened depression onset and demonstrate how refining characterizations of stress may advance our understanding of depression.

Stressful life events, such as the death of a spouse or the termination of an important job, have long been postulated to produce depression. Consistent with this formulation is a large literature documenting an association between severe life events and the subsequent onset of major depressive disorder (MDD; Hammen, 2005; Monroe, Slavich, & Georgiades, 2009; Paykel, 2003). Despite this robust association, however, little is known about the basic nature of the stressors within this general class of stress called “severe stress” and how differences among such life events might be relevant to clinical phenomena, such as the timing of the onset of MDD. This lack of knowledge is due in part to the fact that severe stress has largely been conceptualized as a broad construct within which events of different types are treated as functionally equivalent with respect to their impact.

Against this backdrop is a small body of research highlighting the utility of examining the effects of specific types of life stress (e.g., Keller, Neale, & Kendler, 2007; Kendler, Hettema, Butera, Gardner, & Prescott, 2003). The most widely studied stressor in this context is interpersonal loss (Paykel, 2003), which is understandable given the evolutionarily adaptive benefits that accompany the maintenance of close social bonds. These benefits are evident from primate studies, in which social isolation has been found to predict a lower likelihood of survival (Kling, Lancaster, & Benitone, 1970; Silk, Alberts, & Altmann, 2003; see Baumeister & Leary, 1995). These benefits are also recognized in theories of human development (Ainsworth, 1991; Bowlby, 1969, 1973, 1980), in which the need for nurturance and protection, each critical to survival, are postulated to drive an attachment system that monitors infants’ proximity to their primary caregiver and produces distress when a safe distance is exceeded (Gilbert, 1992).

Given the fundamental importance of social bonds to human functioning, it is not surprising that interpersonal loss events have been accorded a central role in many contemporary theories of depression, including those that are primarily psychodynamic (Blatt, 2004), cognitive (Beck, 1967, 1976), and social (Brown & Harris, 1978) in nature. One point generally not appreciated in these literatures, however, is that interpersonal loss encapsulates a wide variety of life events. One can lose a loved one, for example, to death or to the breakup of a relationship. Although both of these types of loss events are unpleasant, the “ingredients” of the two experiences differ in important ways. For instance, whereas death is finite, irreversible, and irredeemable, break-ups contain elements of premeditation, intentionality, uncertainty, and humiliation. Rejection events are a particularly noxious type of interpersonal loss in this regard, as they imply devaluation or reduced attractiveness by one’s social network (Gilbert, 1992). Central to such experiences is social-evaluative threat, which may provoke negative self-related appraisals that give rise to shame and humiliation (Gruenewald, Kemeny, Aziz, & Fahey, 2004), ultimately leading to despair and depression (Ayduk, Downey, & Kim, 2001). Along these lines, rejection has been found to predict depression among children who are rejected by parents (Lefkowitz & Tesiny, 1984; Puig-Antich et al., 1985) and by peers (French, Conrad, & Turner, 1995; Panak & Garber, 1992; Rudolph, Hammen, & Burge, 1994), as well as among adolescents who are judged to be “rejected” by self-, mother-, and teacher-reports (Nolan, Flynn, & Garber, 2003; see Garber & Horowitz, 2002).

In the present study, we introduce and examine the effects of a specific type of rejection that we hypothesize is associated with a relatively quick onset of depression, given the fundamental motivation that humans possess to maintain social bonds and the poignant manner in which rejection threatens this process. We call this type of rejection targeted rejection (TR) and define it as social rejection that is directed at, and meant to affect, a single person, and that involves an active and intentional severing of relational ties with that person. Stressors occurring in the relationship domain are a good example of TR when, for example, an individual’s partner terminates his or her relationship with the person. This can be contrasted with a similar, but non-TR breakup, in which either the individual initiates the breakup or the breakup is mutual. TR may also occur in the achievement domain when, for example, an individual (and only that individual) is fired from his or her job. This event, too, may be contrasted with a non-TR job loss in which the person either resigns or is fired as the result of company layoffs. (See Table 1 for additional examples.)

TABLE 1.

Examples of Targeted Rejection and Nontargeted Rejection Events

| Life Domain of Event |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Event Type | Work | School | Relationship |

| Targeted Rejection | Subject, a highly specialized chemical engineer, is fired by manager who says that Subject failed to follow “safety protocol.” Jobs of comparable status and pay are scarce. | Subject, a third-year graduate student, fails qualifying examination for the second time. The education committee asks Subject to leave the program, as per the program’s guidelines. | Subject wants to talk about spending more time with partner, who Subject has been seeing for three years. Partner says the issue cannot be resolved and unexpectedly terminates their relationship. |

| Nontargeted Rejection | Subject is laid off with two coworkers, as their boss announces the merger of their workgroup with another to “improve the department’s efficiency.” Financial hardship ensues. | Subject, a medical student, is caught cheating on an exam and will need to retake the course. The transgression will be permanently noted in Subject’s file and all future recommendation letters. | Subject finds a series of sexually explicit e-mails on Spouse’s computer, revealing Spouse’s longstanding unfaithfulness. Subject moves out and ends the six-year relationship. |

These brief examples highlight two core features of TR: (a) the subject is the primary target of the event; and (b) the most salient feature of the event is the rejection of the targeted individual by another person or group of persons. Based on these two core features, three additional characteristics of TR are worth noting:

Intent to Reject. The targeted component of TR assumes active rejection of the subject by another person or group of persons. TR is thus characterized in part by an intent to reject the subject and does not include rejection that results from inaction (e.g., the gradual demise of a relationship through mutual social disengagement) or negligence (e.g., a job loss due to administrative error).

Isolated Impact. The targeted component of TR also assumes that only one person (i.e., the target of the rejection) experiences the direct impact of the rejection. Although other people may be affected indirectly by the rejection, only the target is actively being rejected. Thus, TR is characterized by isolated impact in which only the target individual experiences the crux of the rejection.

Social Demotion. Finally, TR refers to the actual loss, rather than to the thwarted gain, of social status. In other words, TR involves social demotion that results from the severing of a relational tie (e.g., going from having a job or partner to not having a job or partner). The loss of potential social promotion (e.g., being turned down for a date with a potential partner or being turned down for a potential job) is not TR because it does not entail being excluded or shunned by an individual or group with which the person has an ongoing, established social bond.

To examine the effect of TR on the timing of the onset of depression, we compared individuals who had experienced a severe TR event prior to the onset of depression with those who had experienced a pre-onset severe event that was not defined as TR. We predicted that individuals who had experienced a severe TR event would become depressed more quickly than would their counterparts who had experienced a pre-onset severe non-TR event. This prediction was based on the formulation that humans possess a fundamental drive to maintain close social bonds and, conversely, that separating from key social entities has historically posed a challenge to the survival of social animals. Events reminiscent of such outcomes should thus produce immediate and intense distress (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). Specific psychobiological processes may also hasten the onset of depression following exposure to TR. For example, TR events, which involve exclusive, active, and intentional social rejection and demotion, may engender feelings of shame (Leary, 2007), and shame, in turn, is known to be associated with psychoneuroimmunological responses that promote depressotypic behaviors, including immediate disengagement and withdrawal (see Dickerson, Gruenewald, & Kemeny, 2004). From this perspective, depression could still reasonably develop following major forms of non-TR life stress, but given the absence of TR and its downstream psychobiological consequences, a particularly quick onset of depression would not be expected.

METHOD

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURES

Participants were 27 adults (23 females) between the ages of 19 and 57 (M = 32.67, SD = 11.12). These individuals, all diagnosed with MDD, were drawn from a larger investigation (see Gotlib, Kasch, et al., 2004; Gotlib, Krasnoperova, Yue, & Joormann, 2004; Monroe, Slavich, Torres, & Gotlib, 2007a, 2007b), with the limiting requirement for participation in the present study being the presence of a severe life event within one year prior to the onset of depression. Most participants were single (n = 18, 66.67%), with 8 (29.63%) married or living with a domestic partner and 1 (3.70%) divorced. Ethnicity was primarily Asian (n = 12, 44.44%) and Caucasian (n = 11, 40.74%), followed by African American (n = 2, 7.41%) and Latino or Hispanic (n = 2, 7.41%). The sample was generally well-educated, with 16 participants (59.26%) having completed college, 5 (18.52%) reporting graduate or professional education beyond college, and 6 (22.22%) reporting some college or less. Finally, the sample was varied with respect to annual income, with 6 participants (22.22%) earning under $10,000, 4 (14.81%) earning between $10,000 and $25,000, 7 (25.93%) earning between $25,000 and $50,000, 4 (14.81%) earning between $50,000 and $75,000, and 4 (14.81%) earning more than $75,000.1

Participants were recruited through advertisements posted in community locations and through referrals from two outpatient psychiatry clinics at Stanford University. Upon expressing interest in the study, individuals were screened by telephone to recruit those with a high likelihood of current MDD with a recent onset of the disorder (96.3% of participants had an onset within 2 years). Individuals who passed this telephone screen were invited to complete a diagnostic interview and a battery of self-report questionnaires at Stanford University. To be included in the study, participants had to meet Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.; DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 2000) criteria for current MDD, as assessed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1995). These diagnostic interviews were conducted by advanced graduate students and post-baccalaureate research assistants. To assess diagnostic inter-rater reliability, an independent trained rater kept blind to group membership subsequently evaluated 15 SCID audiotapes selected at random from the parent project, which included individuals with depression, panic disorder, social phobia, and no psychopathology. In all 15 of the reassessed cases, the rerating matched the original diagnosis, κ = 1.00.2 Individuals were excluded if they had current comorbid panic disorder or social phobia; a lifetime history of mania, hypomania, or primary psychotic symptoms; a recent history (i.e., past 6 months) of alcohol or psychoactive substance abuse or dependence; or a history of brain injury or mental retardation. Participants who met these diagnostic requirements were invited for an additional session in which their life stress was assessed (see below). All participants provided written informed consent and were paid $25 per hour.

LIFE STRESS ASSESSMENT

Life stress was assessed from one year prior to the onset of depression up to the day of the interview using the Life Events and Difficulties Schedule (LEDS; Brown & Harris, 1978). This system first employs a two-hour semi-structured interview in which the interviewer systematically inquires about potential stressors. Next, the interviewer presents the reported events to a panel of raters who judge each stressor using a 520-page manual that outlines explicit rules for rating life stress. The manual also includes 5,000 case vignettes that are used as anchors in the rating process. Ratings are made independently by each rater and are then finalized after a consensus discussion that considers extensive information about the event, the context surrounding the event, and the individual’s biographic circumstances (i.e., contextual ratings; see Brown & Harris, 1978, 1989).

In the present study, after the LEDS interview was completed at Stanford University, the interviewer presented the detailed life stress information to a panel of trained raters at the University of Oregon during a 1.5- to 2-hour conference call. The number of raters per case ranged from one to four, with the majority of cases involving three or four raters.3 These raters were kept blind to participants’ subjective responses to the events (e.g., how often they cried) and to the relevant study variables (e.g., timing of the onset of depression) to limit the influence of these clinical features of depression on the ratings of life stress.

Of particular interest in the present study were events rated as severe, which have been found to reliably predict the onset of depression (Brown & Harris, 1989). After being identified, these events were carefully examined during the rating session for the purpose of classifying them as TR or non-TR. If the event was a job loss, clarifying questions included: Was the subject fired and, if so, why? What were the social circumstances before, during, and after the firing? Did others lose their job at this time for related reasons? If the event was a relationship breakup, clarifying questions included: How long were the two people dating? Who initiated the breakup? If the subject’s partner initiated the breakup, was the subject in favor of the breakup? What were the consequences of the breakup in terms of future interactions? After discussing the characteristics of a given event in light of these questions, a consensus rating was obtained with respect to whether the event was TR.4 Overall, the LEDS has established psychometric validity and is regarded as a state-of-the-art instrument for assessing diverse types of stress (Dohrenwend, 2006; Hammen, 2005; Monroe, 2008). Inter-rater agreement for the present project ranged from.72 to.79 (M =.76; Cohen’s kappa, corrected for differences in the number of raters per event; Uebersax, 1982).

TIME TO ONSET OF DEPRESSION

Time to onset of depression, indexed as the number of days between the occurrence of an event and the onset of depression, was calculated for each severe life event that participants experienced prior to onset. Depression onset dates were obtained in the SCID and were verified at the beginning of the LEDS interview. Dating for severe events was established during the LEDS interview as each event was discussed.

DATA ANALYSES

Preliminary analyses were conducted on the major demographic variables to ensure that these factors could not significantly affect tests of the primary study hypothesis. Cox regression survival analyses were then run to predict time to onset of depression for participants with a pre-onset severe TR or non-TR event.5 We followed these tests with secondary analyses that explored alternative explanations for our findings, focusing on the possible relations of life domain and depression history to time to onset of depression. Finally, qualitative analyses were conducted to examine specific characteristics of these events (e.g., loss, danger, humiliation) in relation to onset.

RESULTS

DEMOGRAPHIC VARIABLES

Major demographic variables, including sex, age, marital status, ethnicity, and income, were unrelated to the presence of a severe TR event, and to the number of days between severe TR and non-TR events and the onset of depression (i.e., time to onset; p >.4 for all tests).

TARGETED REJECTION AND TIME TO ONSET OF DEPRESSION

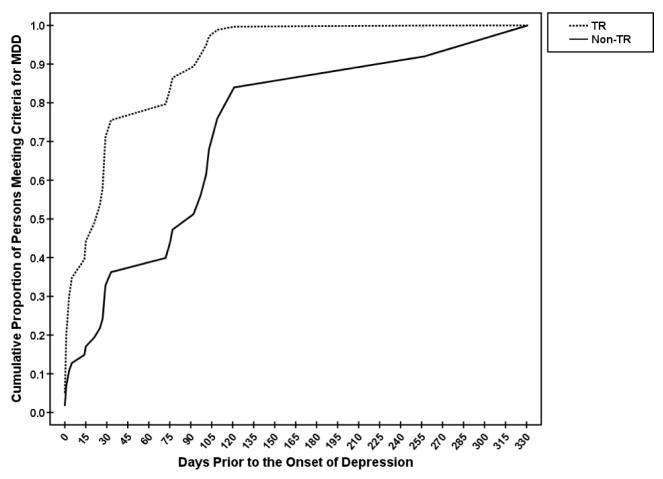

We predicted that individuals who had experienced a severe TR event prior to the onset of their depression (n = 16) would become depressed more quickly than would their counterparts who had experienced a pre-onset severe event that was not defined as TR (n = 11). As predicted, pre-onset TR status was significantly associated with onset of depression, χ2(1, N = 27) = 6.39, p =.011, R2 =.21, with exposure to TR predicting significantly shorter time to onset (b = 1.14, p =.015, odds ratio = 3.13, 95% confidence interval = 1.24–7.86). Nearly half of participants (44%) who experienced a severe TR event became depressed within 15 days and 75% became depressed within 30 days, compared to only 18% and 27%, respectively, for the non-TR event group (see Figure 1). Follow-up descriptive analyses revealed that the average time to onset of depression was 30.4 days ( SD = 35.3) for the TR event group, compared to 107.5 days (SD = 101.4) for the non-TR event group.

FIGURE 1.

Cumulative proportion of persons meeting criteria for MDD over time, stratified by exposure to a pre-onset severe targeted rejection (TR) event versus a pre-onset severe nontargeted rejection (Non-TR) event.

In our sample, 19 participants experienced one pre-onset severe event, seven experienced two severe events, and one experienced three severe events. These latter two groups of individuals complicated the aforementioned analyses of time to onset, given that time to onset presumes the existence of only one event date and one depression onset date. To address this issue, for the analyses just described, we selected the severe TR event over the severe non-TR event for participants who experienced more than one pre-onset severe life event. As an alternative approach, we reanalyzed these data after selecting the severe TR event or severe non-TR event that was closest in proximity to the onset of depression for participants who experienced more than one pre-onset severe event, yielding a distribution of n = 14 and n = 13, respectively, for the TR and non-TR event groups. This selection strategy did not alter the basic finding: TR status was significantly associated with onset of depression, χ2(1, N = 27) = 4.50, p =.034, R2 =.15, with exposure to TR predicting significantly shorter time to onset (b = 0.90, p =.039, odds ratio = 2.46, 95% confidence interval = 1.20–5.81).

SECONDARY ANALYSES: LIFE DOMAIN, DEPRESSION HISTORY, AND TIME TO ONSET OF DEPRESSION

One alternative explanation for the TR effect concerns the differential impact that events in different life domains (e.g., relationship, work/school, health) may have on the timing of the onset of depression. For example, TR could be more frequently present or more influential in the relationship domain than in the work/school or health domain, and it may be life domain, and not the presence of TR specifically, that predicts the timing of the onset of depression. To test this possibility, we reclassified events as having occurred in the relationship domain (n = 14), work/school domain (n = 7), or health domain (n = 6). Time to onset of depression, however, was unrelated to life domain, χ2(2, N = 27) = 0.76, p =.693, R2 =.03.

Another possibility is that time to onset of depression varies as a function of history of depression, such that those with a greater personal history of depression (i.e., more prior episodes) may become depressed more quickly than their less vulnerable counterparts. This effect would be consistent with the stress sensitization model, which posits that progressively less severe doses of stress may gain the capability to trigger a depressive episode more quickly over successive recurrences of depression and exposures to stress (see Monroe & Harkness, 2005). Furthermore, individuals with a greater personal history of depression may be more likely to generate severe TR events in their lives (i.e., “stress generation”; see Hammen, 1991). Considered together, then, prior history of depression may be related to both the generation of TR and the timing of the onset of depression. Examining these relations revealed that the presence of a pre-onset TR event was moderately related to depression history, t (25) = 1.56, p =.132, d = 0.64, but in the direction opposite of what would be predicted by the stress generation hypothesis (TR group: M = 2.4 lifetime episodes, SD = 2.0; non-TR group: M = 3.6 lifetime episodes, SD = 1.9). Depression history, however, was unrelated to time to onset (b = −0.10, p =.391), and after adjusting for depression history (entered in Step 1 of the Cox regression equation), TR status (entered in Step 2) was still significantly associated with onset of depression, χ2(1, N = 27) = 5.86, p =.016, R2 =.20, with exposure to TR predicting significantly shorter time to onset (b = 1.11, p =.020, odds ratio = 3.02, 95% confidence interval = 1.19–7.70).

QUALITATIVE ANALYSES OF TARGETED REJECTION AND TIME TO ONSET OF DEPRESSION

The main finding from these analyses is that, on average, TR events are associated with a significantly quicker onset of depression than non-TR events, even after adjusting for history of depression. Still, considerable variability in time to onset of depression, especially for non-TR events (SD = 107.5 days), suggests that timing of onset may be influenced by the presence of stressor characteristics other than TR. Qualitative analyses designed to examine these characteristics suggested that for participants exposed to a non-TR event, relatively quick onset (i.e., in less than 30 days) was precipitated primarily by serious health events that involved low personal control and danger, and which forecasted the potential loss of a key individual. The present data contained two such events: mother’s ruptured appendix and father’s liver cancer. The third non-TR event that precipitated onset in less than 30 days was a non-TR job loss that involved elements of humiliation. Variability in time to onset of depression for TR events, in contrast, did not appear to be explained by the presence of events involving these stressor characteristics.

DISCUSSION

Despite general consensus that severe life events are strongly associated with the onset of MDD, little is known about how stressors within this broad class of stress might have differential effects on clinically important phenomena related to depression. We addressed this issue by introducing a specific type of stress, targeted rejection (TR), and by examining its impact on the timing of the onset of depression. As predicted, participants who had experienced a severe TR event prior to the onset of depression became depressed more quickly (i.e., approximately three times faster) than did their counterparts who had experienced a severe life event that was not defined as TR. History of depression could have theoretically influenced time to onset, so we reexamined the relation of TR to onset of depression while considering participants’ number of lifetime episodes of MDD. Depression history, however, was unrelated to time to onset, and after adjusting for number of lifetime episodes of MDD, exposure to TR still significantly predicted shorter time to onset. We further explored this effect by qualitatively examining variability in time to onset of depression within the TR and non-TR event categories, and this analysis suggested that for non-TR events, hastened onset was precipitated primarily by serious health events involving elements of low personal control, danger, and potential interpersonal loss. The presence of events involving these stressor characteristics, however, did not help to explain variability in time to onset for TR events. Overall, these findings are consistent with previous work showing specificity in the association between exposure to certain forms of severe stress (e.g., interpersonal loss, rejection) and the onset of major depression (see Kendler et al., 2003; Monroe, Rohde, Seeley, & Lewinsohn, 1999). These findings also demonstrate how refining characterizations of severe life stress may enhance the prediction of key clinical aspects of the disorder.

We also tested whether life domain (i.e., relationship, work/school, health) was related to the timing of the onset of depression. This permitted us to compare our findings for TR with those based on more traditional distinctions that have been made in order to examine potential specificity in the association between different types of life events and the onset of depression. Unlike TR status, however, life domain was unrelated to time to onset of depression. Although caution is warranted given the sample size in this study, this comparison controls for the possibility that TR is associated with life domain which, in turn, accounts for the differences obtained with respect to time to onset of depression. Along these lines, we argue that life domain should not simply be used as a proxy for a stressor characteristic, given that events like TR may occur in multiple life domains. Moreover, it may be the particular characteristic of interest (e.g., TR), not the life domain in which an event occurs, that is more relevant to clinical aspects of depression.

Underscoring the significance of our finding for TR is the fact that TR and non-TR events generally shared many of the same characteristics and, by definition, were differentiated only with respect to their TR status. TR and non-TR events, for example, were equated on severity in that all events were rated as severe, and both types of events included interpersonal stressors. In addition, both the TR and non-TR event category contained events that were the result of participants’ actions and behaviors to varying degrees, meaning that dependent and partially dependent events were not associated with TR exclusively, but instead were represented among these events more generally. Indeed, all of the TR events and 8 of 11 of the non-TR events were rated dependent or partially dependent using LEDS criteria. TR and non-TR events shared other qualities as well, but the point is that differentiating events with respect to TR alone had unique significant predictive utility.

We did not examine potential mechanisms by which TR hastens the onset of depression, but several are possible. Situations involving social evaluation and rejection, for example, are known to engender feelings of shame (Leary, 2007; Tangney, Stuewig, & Mashek, 2007), and TR may be especially associated with shame given the manner in which such events threaten a person’s social status and image (Dickerson, Gruenewald, et al., 2004). Partly through its relation to shame, TR may also activate components of the immune system that initiate depressotypic changes in motivation and behavior (Dickerson, Kemeny, Aziz, Kim, & Fahey, 2004). Of particular relevance in this regard are proinflammatory cytokines, which have been found to be associated with decreased food and water consumption, reduced responsiveness to reward (i.e., anhedonia), increased social withdrawal, and the onset of malaise (see Dantzer, O’Connor, Freund, Johnson, & Kelley, 2008). Related to this process is the fact that exposure to rejection increases cortisol secretion (Blackhart, Eckel, & Tice, 2007; Gunnar, Sebanc, Tout, Donzella, & van Dulmen, 2003; Stroud, Salovey, & Epel, 2002; see also Dickerson & Kemeny, 2004). Although cortisol helps regulate proinflammatory cytokine production under normal conditions, proinflammatory cytokines may themselves disrupt cortisol signaling and thus the regulatory capability of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, further increasing risk for depression (Robles, Glaser, & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2005).

Specific neurobiological pathways may also be implicated in hastening the onset of depression insofar as they subserve the heightened sensitivity of humans to social rejection. Along these lines, rejection has been found to be associated with activation in the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, a brain region also involved in the processing of physical pain (Eisenberger, Lieberman, & Williams, 2003; Lieberman, 2007). This is notable because it suggests that physical injuries and injuries to one’s social bonds, both of which have historically represented potential threats to survival, may share an underlying neural circuitry that becomes activated in the presence of cues indicating impending danger (Eisenberger & Lieberman, 2004; see MacDonald & Leary, 2005). Activation in these particular brain regions, however, may be preferentially associated with life events that are reminiscent of TR.

A strength of the present study is the use of a state-of-the-art measure of life stress, the LEDS, in a sample of clinically depressed individuals. This is notable because the vast majority of studies on life stress and depression have utilized self-report checklist measures of stress for which the limitations (e.g., variability in reporting, as well as confounding between life stress and the symptoms of depression) are well documented (see Dohrenwend, 2006). Moreover, the LEDS was important as it permitted us to examine severe life events with excellent resolution, allowing us to differentiate types of severe stressors in general and interpersonal loss events in particular.

The LEDS was also useful for helping us to begin to understand why TR is so psychologically noxious. For example, we observed that TR events do not typically involve only one rejection source. Although the TR events were initiated by one person, as they unfolded the rejection tended to spread to other people in the social network with whom the initiator of the rejection had alliances. For example, if the source of the rejection was a boss, then the rejection spread to employees in the company who, in order to preserve their own status, subtly sided with the manager. If the source of the rejection was a romantic partner, then the rejection spread to mutual friends who remained loyal to the breakup initiator and shunned the rejected partner. This interpersonal process highlights the subtle yet potent way in which a seemingly circumscribed rejection event may affect peoples’ relationships with others in their wider social circle. In many cases, being rejected by one person does not just mean being rejected by that person alone; it means being rejected (albeit in more subtle ways) by those who have an alliance with the source of the rejection, a process we call rejection reverberation.

Several limitations of the present study should also be noted. First, our sample was relatively small and primarily female, with high proportions of Asian and Caucasian individuals. These characteristics may limit the generalizeability of our findings. Second, given our definition of TR, it was not possible to determine if a particular aspect of TR (e.g., intent to reject, isolated impact, social demotion) was more responsible for its effects than were other aspects. Although we believe that TR captures these features in a coherent and psychologically meaningful way, experimental manipulations of TR and related types of stress are necessary to more precisely specify the deleterious characteristics of stress. This type of work could also help to establish causal links between TR and the aforementioned psychobiological mechanisms that are known to increase risk for depression. Third, since our goal was to further characterize severe life stress, the present data speak to persons experiencing this class of stress most directly and may or may not extend to those who develop depression following less severe forms of TR. Finally, our assessment of TR was based on retrospective reports of depressed individuals, which were inevitably influenced by participants’ memories and motivations. To limit the effect of these factors on our index of stress, we utilized a state-of-the-art measure that employs a trained interviewer and an independent team of trained raters. The advantage of this method in terms of minimizing reporting biases, however, is difficult to assess, and virtually all research on life stress and depression is burdened by this methodological issue.

Looking forward, there are several interesting questions for future research to pursue. For example, is exposure to TR associated with risk for depression (i.e., in addition to variation in time to onset of the disorder)? This might be expected, but has yet to be demonstrated. In addition, how do factors like sex, ethnicity, and personality (e.g., rejection sensitivity and neuroticism) moderate the effects of TR on depression, given differences in how subgroups of individuals value connectedness and experience rejection? Individuals of Asian and Caucasian decent, for example, are known to ascribe to different worldviews (Markus & Kitayama, 1991), and TR may thus have differential effects across these groups. Finally, does exposure to TR or to other types of life stress predict specific symptom profiles or subtypes of depression? If depressive states have been finely tuned to help humans manage diverse adverse circumstances, then certain symptoms may be linked to particular external precipitants (de Kloet, Joëls, & Holsboer, 2005; Keller & Nesse, 2005; Keller et al., 2007; Nesse, 2000). Alternatively, MDD could be the product of an adaptive system functioning outside of its adaptive range, in which case the relation of stress to specific depressive symptoms might be relatively weak. Yet another possibility is that life stress has a pathoplastic (i.e., symptom modification) role for some subtypes of depression and not for others.

There are also broader questions concerning the mechanisms that underlie the onset of depression, and how such mechanisms may differ in kind, operation, or arrangement as a function of exposure to different types of precipitating life events. For example, do all depressions develop by way of a similar cognitive, physiological, and neurobiological pathway? The present findings bring this question to the forefront, given how quickly some participants became depressed versus others. Severe stress has gained popularity as a seemingly obvious and straightforward explanatory construct in depression (Monroe & Slavich, 2007), but this characterization is oversimplified, and considering the relation of particular stressors to potentially different pathways to depression might help reveal exactly how stress leads to changes in emotion and behavior, and ultimately depression.

To our knowledge, the present study is one of the first to refine characterizations of severe life stress and to use such information in predicting the specific timing of the onset of depression based on a priori hypotheses concerning the relation of stress to depression. Along these lines, we conclude that exposure to TR is associated with the hastened onset of major depression. Additional research is warranted, however, to elucidate other important forms and features of severe stress. Such work would permit us to examine with greater specificity the link between various stressors and the many clinical features of depression (Brown, Harris, & Hepworth, 1995). Advances on this front could also help form the theoretical foundation needed to develop a taxonomy of life stress (Monroe et al., 2009; Nesse, 2000), bringing us closer to understanding more precisely why severe stress is so likely to be followed by depression.

Acknowledgments

This work was sponsored by National Institute of Mental Health Re search Grants MH60802 to Scott M. Monroe and MH59259 to Ian H. Gotlib. Preparation of the present report was supported by a Society in Science: Branco Weiss Fellowship and by Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award MH019391-17 to George M. Slavich. We thank Lauren Anas, Erica Aronson, Kathryn Dingman, Corrie Doyle, Julien Guillaumot, Danielle Keenan-Miller, and Keely Muscatell for helping with the stress assessment procedure, and Faith Brozovich for assisting with data management. We also thank Margaret Kemeny and Keely Muscatell, and two anonymous reviewers, for their helpful comments on previous versions of this report.

Footnotes

Two participants declined to report their annual income.

This represents excellent reliability, although we note that the interviewers used the “skip out” strategy of the SCID, which may have reduced the opportunities for the independent rater to disagree with the diagnoses (Gotlib, Kasch, et al., 2004; Gotlib, Krasnoperova, et al., 2004).

Raters were trained by Scott M. Monroe, who was trained in the LEDS system by Tirril Harris. Scott M. Monroe served as a rater for all but one of the rating sessions.

For case exemplars and more detailed instructions on rating TR, go to http://www.targetedrejection.com

Cox regression survival analyses are well-suited for these types of data, as distributions for time to an event, such as the onset of depression, are usually dissimilar from the normal and often nonsymmetric, posing violations to which liner regression is not robust.

Contributor Information

GEORGE M. SLAVICH, University of California, San Francisco

TIFFANY THORNTON, University of Oregon.

LEANDRO D. TORRES, University of California, San Francisco

SCOTT M. MONROE, University of Notre Dame

IAN H. GOTLIB, Stanford University

References

- Ainsworth MDS. Attachments and other affectional bonds across the life cycle. In: Parkes CM, Stevenson-Hinde J, Marris P, editors. Attachment across the life cycle. London: Routledge; 1991. pp. 33–51. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4 Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ayduk O, Downey G, Kim M. Rejection sensitivity and depressive symptoms in women. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2001;27:868–877. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Leary MR. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117:497–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT. Depression: Clinical, experimental, and theoretical aspects. New York: Harper and Row; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT. Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. New York: New American Library; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Blackhart GC, Eckel LA, Tice DM. Salivary cortisol in response to social rejection and acceptance by peers. Biological Psychology. 2007;75:267–276. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatt SJ. Experiences of depression: Theoretical, clinical, and research perspectives. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. New York: Basic Books; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Vol. 2. Separation, anxiety, and anger. New York: Basic Books; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Vol. 3. Loss: Sadness and depression. New York: Basic Books; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Brown GW, Harris TO. Social origins of depression: A study of psychiatric disorder in women. New York: The Free Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Brown GW, Harris TO. Depression. In: Brown GW, Harris TO, editors. Life events and illness. London: The Guilford Press; 1989. pp. 49–93. [Google Scholar]

- Brown GW, Harris TO, Hepworth C. Loss, humiliation and entrapment among women developing depression: A patient and non-patient comparison. Psychological Medicine. 1995;25:7–21. doi: 10.1017/s003329170002804x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzer R, O’Connor JC, Freund GG, Johnson RW, Kelley KW. From inflammation to sickness and depression: When the immune system subjugates the brain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2008;9:46–57. doi: 10.1038/nrn2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kloet ER, Joëls M, Holsboer F. Stress and the brain: From adaptation to disease. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2005;6:463–475. doi: 10.1038/nrn1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson SS, Gruenewald TL, Kemeny ME. When the social self is threatened: Shame, physiology, and health. Journal of Personality. 2004;72:1191–1216. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson SS, Kemeny ME. Acute stressors and cortisol responses: A theoretical integration and synthesis of laboratory research. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130:355–391. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.3.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson SS, Kemeny ME, Aziz N, Kim KH, Fahey JL. Immunological effects of induced shame and guilt. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2004;66:124–131. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000097338.75454.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohrenwend BP. Inventorying stressful life events as risk factors for psychopathology: Toward resolution of the problem of intracategory variability. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132:477–495. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.3.477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger NI, Lieberman MD. Why rejection hurts: A common neural alarm system for physical and social pain. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2004;8:294–300. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger NI, Lieberman MD, Williams KD. Does rejection hurt? An fMRI study of social exclusion. Science. 2003;302:290–292. doi: 10.1126/science.1089134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer MB, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis\disorders—patient edition. New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1995. SCID-I/P, Version 2.0. [Google Scholar]

- French DC, Conrad J, Turner TM. Adjustment of antisocial and nonantisocial rejected adolescents. Development and Psychopathology. 1995;7:857–874. [Google Scholar]

- Garber J, Horowitz JL. Depression in children. In: Gotlib IH, Hammen CL, editors. Handbook of depression. New York: The Guilford Press; 2002. pp. 510–540. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert P. Depression: The evolution of powerlessness. New York: The Guilford Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH, Kasch KL, Traill S, Joormann J, Arnow BA, Johnson SL. Coherence and specificity of information-processing biases in depression and social phobia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:386–398. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.3.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH, Krasnoperova E, Yue DN, Joormann J. Attentional biases for negative interpersonal stimuli in clinical depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:127–135. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenewald TL, Kemeny ME, Aziz N, Fahey JL. Acute threat to the social self: Shame, social self-esteem, and cortisol activity. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2004;66:915–924. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000143639.61693.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar MR, Sebanc AM, Tout K, Donzella B, van Dulmen MM. Peer rejection, temperament, and cortisol activity in preschoolers. Developmental Psychobiology. 2003;43:346–358. doi: 10.1002/dev.10144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Generation of stress in the course of unipolar depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:555–561. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Stress and depression. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:293–319. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller MC, Neale MC, Kendler KS. Association of different adverse life events with distinct patterns of depressive symptoms. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:1521–1529. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06091564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller MC, Nesse RM. Is low mood an adaptation? Evidence for subtypes with symptoms that match precipitants. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2005;86:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Hettema JM, Butera F, Gardner CO, Prescott CA. Life event dimensions of loss, humiliation, entrapment, and danger in the prediction of onsets of major depression and generalized anxiety. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:789–796. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kling A, Lancaster J, Benitone J. Amygdalectomy in the free-ranging vervet (Cercopithecus aethiops) Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1970;7:191–199. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(70)90006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leary MR. Motivational and emotional aspects of the self. Annual Reviews of Psychology. 2007;58:317–344. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefkowitz MM, Tesiny EP. Rejection and depression: Prospective and contemporary analysis. Developmental Psychology. 1984;20:776–785. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman MD. Social cognitive neuroscience: A review of core processes. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:259–289. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald G, Leary MR. Why does social exclusion hurt? The relationship between social and physical pain. Psychological Bulletin. 2005;131:202–223. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.2.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus H, Kitayama S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review. 1991;98:224–253. [Google Scholar]

- Monroe SM. Modern approaches to conceptualizing and measuring human life stress. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2008;4:33–52. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.4.022007.141207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monroe SM, Harkness KL. Life stress, the “Kindling” Hypothesis, and the recurrence of depression: Considerations from a life stress perspective. Psychological Review. 2005;112:417–445. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.112.2.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monroe SM, Rohde P, Seeley JR, Lewinsohn PM. Life events and depression in adolescence: Relationship loss as a prospective risk factor for first onset of major depressive disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1999;108:606–614. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.4.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monroe SM, Slavich GM. Psychological stressors, overview. In: Fink G, editor. Encyclopedia of stress. 2. Vol. 3. Oxford: Academic Press; 2007. pp. 278–284. [Google Scholar]

- Monroe SM, Slavich GM, Georgiades K. The social environment and life stress in depression. In: Gotlib IH, Hammen CL, editors. Handbook of depression. 2. New York: The Guilford Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Monroe SM, Slavich GM, Torres LD, Gotlib IH. Major life events and major chronic difficulties are differentially associated with history of major depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007a;116:116–124. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monroe SM, Slavich GM, Torres LD, Gotlib IH. Severe life events predict specific patterns of change in cognitive biases in major depression. Psychological Medicine. 2007b;37:863–871. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707000281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesse RM. Is depression an adaptation? Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57:14–20. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan SA, Flynn C, Garber J. Prospective relations between rejection and depression in young adolescents. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;85:745–755. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.4.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panak WF, Garber J. Role of aggression, rejection, and attributions in the prediction of depression in children. Development and Psychopathology. 1992;4:145–165. [Google Scholar]

- Paykel ES. Life events and affective disorders. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2003;108:61–66. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.108.s418.13.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puig-Antich J, Lukens E, Davies M, Goetz D, Brennan-Quattrock J, Todak G. Psychosocial functioning in prepubertal major depressive disorders: I. Interpersonal relationships during the depressive episode. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1985;23:8–15. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790280082008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robles TF, Glaser R, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Out of balance: A new look at chronic stress, depression, and immunity. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2005;14:111–115. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Hammen C, Burge D. Interpersonal functioning and depressive symptoms in childhood: Addressing the issue of specificity and comorbidity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1994;22:355–371. doi: 10.1007/BF02168079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silk JB, Alberts SC, Altmann J. Social bonds of female baboons enhance infant survival. Science. 2003;302:1231–1234. doi: 10.1126/science.1088580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroud LR, Salovey P, Epel ES. Sex differences in stress responses: Social rejection versus achievement stress. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;52:318–327. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP, Stuewig J, Mashek DJ. Moral emotions and moral behavior. Annual Reviews of Psychology. 2007;58:345–372. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uebersax JS. A generalized kappa coefficient. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1982;42:181–183. [Google Scholar]