Summary

Notch signaling is one of the most important pathways in development and homeostasis, and is altered in multiple pathologies. Study of Drosophila eye development shows that Notch signaling depends on the HLH protein Extramacrochaetae. Null mutant clones show that extramacrochaetae is required for multiple aspects of eye development that depend on Notch signaling, including morphogenetic furrow progression, differentiation of R4, R7 and cone cell types, and rotation of ommatidial clusters. Detailed analysis of R7 and cone cell specification reveals that extramacrochaetae acts cell autonomously and epistatically to Notch, and is required for normal expression of bHLH genes encoded by the E(spl)-C which are effectors of most Notch signaling. A model is proposed in which Extramacrochaetae acts in parallel to or as a feed-forward regulator of the E(spl)-Complex to promote Notch signaling in particular cellular contexts.

Keywords: extra macrochaetae, Drosophila eye, Notch signaling, R7 cell, eye development, cell fate specification

INTRODUCTION

The Notch signaling pathway is one of the cell-cell communication pathways that are most widely used for cell fate specification (Bray, 2006). During Drosophila eye development, Notch signaling is important for the growth of the eye imaginal disc (the retinal primordium), for the definition of its dorsal and ventral hemispheres, and for the movement of the wave of differentiation that crosses the eye disc called the morphogenetic furrow. Within the morphogenetic furrow, Notch is essential for the lateral inhibition that specifies an array of single R8 photoreceptor cells through the negative regulation of a proneural bHLH gene, atonal (ato). Posterior to the morphogenetic furrow, Notch signaling is required for the induction of other retinal cell types including R4 photoreceptor cells, R7 photoreceptor cells, and non-neuronal cone cells, as well as rotation of the developing ommatidial clusters (Nagaraj et al., 2002).

Specification of R7 photoreceptor cells also requires Notch signaling as well as the receptor tyrosine kinase Sevenless (Sev) (Cooper and Bray, 2000; Tomlinson and Struhl, 2001; Doroquez and Rebay, 2006). A group of cells that include the precursors of the R1, R6 and R7 photoreceptor cells, and the cone cells, constitute the “R7 equivalence group”. Contact with the R8 cell induces activation of Sev in the R7 precursor. Contact with the R1 and R6 photoreceptors that express the ligand Delta (Dl) activates Notch in the R7 and cone cell precursors. In this combinatorial system, synergistic activation of Sev and Notch signaling is required for R7 development. Failure to activate receptor tyrosine kinases causes the presumptive R7 photoreceptor to acquire a cone cell fate. Conversely, ectopic Sev activity transforms cone cells into supernumerary R7 cells. In the absence of Notch activity the presumptive R7 photoreceptor acquires R1/R6 photoreceptor fate instead. Conversely, ectopic activation of Notch signaling in R1/R6 photoreceptor pair directs these photoreceptors to develop as ectopic R7 photoreceptor cells.

The canonical Notch signaling pathway involves ligand-dependent release of the Notch intra-cellular domain, which enters the nucleus and activates transcription by complexing with the DNA-binding protein Suppressor-of-Hairless [Su(H)] and the co-activator Mastermind (Mam) (Bray, 2006). As each Notch molecule can be activated once only, and the cleaved intracellular domain is thought to turn over rapidly, the response to the binding of each ligand molecule may be short-lived (Fryer et al., 2004). Many aspects of Notch function are mediated through the transcription of target genes within the E(spl)-Complex, which includes seven bHLH proteins that act as transcriptional repressors of other genes. The function of Notch was first studied during neurogenesis, where Notch mediates lateral inhibition through E(spl)-mediated repression of proneural bHLH genes. Class II bHLH genes, such as the ato gene that is required for R8 photoreceptor specification (Jarman et al., 1994), define proneural regions competent to give rise to neural precursor cells as heterodimers with the ubiquitously-expressed Class I bHLH gene Daughterless (Da) (Doe and Skeath, 1996; Hassan and Vassin, 1996; Massari and Murre, 2000).

In addition to transcriptional regulation by Notch, proneural bHLH gene function can also be modulated post-translationally by the Extra-macrochaetae protein (Campuzano, 2001). The extramacrochaetae (emc) gene encodes a helix-loop-helix protein without any basic DNA-binding domain. Emc antagonizes bHLH proteins’ function by forming non-functional heterodimers with them. Emc has mammalian homologs, the Inhibitor of differentiation (Id) proteins, that are implicated in development and cancer (Ruzinova and Benezra, 2003; Iavarone and Lasorella, 2004). In Drosophila, the emc gene has been thought to provide an initial prepattern that influences the patterning of neurogenesis (Ellis et al., 1990; Garrell and Modolell, 1990; Brown et al., 1995; Campuzano, 2001). This conclusion, however, has been based on the study of weak, hypomorphic mutant alleles. Imaginal disc clones homozygous for null alleles of emc do not survive, suggesting that the gene must have additional roles that remain to be elucidated (Garcia Alonso and Garcia-Bellido, 1988; de Celis et al., 1995; Campuzano, 2001). In addition, more recent studies suggest that Emc function may be linked to Notch signaling. Studies of wing and ovary development show that Notch signaling enhances expression of emc enhancer traps, and that emc is required for aspects of Notch function in those organs (Baonza et al., 2000; Adam and Montell, 2004). By contrast, emc was reportedly repressed by Notch signaling during eye development (Baonza and Freeman, 2001).

In the course of investigating emc as a possible cell cycle target of Notch signaling, we have discovered that the lethality of emc null mutant cells can be delayed very substantially using the Minute technique to provide a growth advantage, and through their study that emc is required for many aspects of Drosophila eye development. We present an outline of these requirements for emc. In addition, we now find that emc transcription is not repressed by Notch signaling in eye development as reported previously, but may be enhanced as also reported for the wing and ovary. A detailed analysis of the role of emc in R7 and cone cell development shows that Notch requires emc to induce R7 and cone cell fates. These findings add to the evidence that emc contributes to Notch signaling, perhaps by promoting E(spl)-C expression.

METHODS

Mosaic Induction

Clones of cells homozygous mutant for genes were obtained by FLP-FRT mediated mitotic recombination technique (Xu and Rubin, 1993; Newsome et al., 2000). For non-Minute genotypes, larvae were subjected to 1 hour heat shock at 37 °C at 60 ± 12 hours after egg laying and were dissected 72 hours later. For Minute genotypes, heat shock was administered at 84 ± 12 hours after egg laying and were dissected 72 hours later. ‘Flip-out’ clones were generated by subjecting larvae to heat shock at 37 °C for 30 minutes at 60 ± 12 hours after egg laying and were dissected 72 hours later.

Flies were maintained at 25°C unless mentioned otherwise.

All genotypes are described in the Figure legends.

Drosophila Strains

The following Drosophila strains were used: w; P{PZ}emc04322 (Rottgen et al., 1998); UAS-Ser [line #19] (Li and Baker, 2004); UAS-Dl (Jönsson, 1996); UAS-Nintra (Fuerstenberg and Giniger, 1998); act>CD2>GAL4, UAS-GFP (Pignoni and Zipursky, 1997; Neufeld et al., 1998); mam10 (Lehmann, 1983); Su(H)Δ47 [w+ l(2)35Bg+] (Morel and Schweisguth, 2000); E(spl)grob32.2p[gro+] (Heitzler et al., 1996); emcAP6 (Ellis, 1994); [UbiGFP] M(3)67C FRT80 (Janody et al., 2004); E(spl)mδ 0.5-lacZ ry+ (Cooper and Bray, 1999) and Cyo [w+, sev-Nact] (Fortini et al., 1993); UAS-Da (Hinz et al., 1994); sev-Gal4 (Brand and Perrimon, 1993); UAS-E(spl)-mδ (de Celis et al., 1996).

Temperature-Sensitive Studies

Nts/Y larvae were reared at 25°C (Cagan and Ready, 1989). Larvae were transferred to the restrictive temperature 31°C for 3 hours prior to dissection.

Immunohistochemistry

Labeling of eye discs involving guinea pig anti-Runt 1/1500 (Duffy et al., 1991), mouse anti-Svp 1/1000 (Kanai et al., 2005), mouse anti-Pros 1/25 (MR1A), mouse anti-Cut 1/20 (2B10) (both were obtained from Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank) and rabbit anti-DPax-2 1/50 (Fu and Noll, 1997) were performed as described (Domingos et al., 2004). Other antibody and DRAQ5 labelings were performed as described (Firth et al., 2006). Images were recorded using BioRad Radiance 2000 Confocal microscope and processed using NIH Image J and Adobe Photoshop 9.0 software. Other primary antibodies used were: mouse anti-βGal 1/100 (mAb40-1a), rat anti-ELAV 1/50 (7E8A10) (both were obtained from DSHB), guinea pig anti-Sens 1/500 (Nolo et al., 2000), rabbit anti-Emc 1/8000 [A gift from Y. N. Jan (Brown, 1995 #9)], rabbit anti-Salm 1/50 (Kuhnlein et al., 1994), mouse anti-Hairy 1/50 (Brown et al., 1995), anti-E(spl) (mAb323) 1/1 (Jennings et al., 1994 ) and anti-GFP 1/500 (Invitrogen).

RNA in situ Hybridization

RNA in situ probe design, preparation and detection were performed as described (Firth and Baker, 2007). Hybridization was performed at 55°C.

Primers used for the first PCR reaction [See Materials and Methods (Firth and Baker, 2007)] to amplify transcribed regions of emc genomic DNA:

Forward Primer 5’ GGCCGCGGGCATCTCTTCAACGCTCCTT 3’

Reverse Primer 5’ CCCGGGGCTGCTGCTGAGTTGGTTGTTC 3’

RESULTS

emc transcriptional reporters coincide with Notch activity

To evaluate the relationship between emc and Notch signaling, expression of the emc gene was visualized during developing third instar Drosophila larval eye using enhancer trap lacZ insertion lines P{PZ}emc04322 and P{PZ}emc03970 (Figs. 1, 2 and data not shown). emc-lacZ was expressed in all cells in the developing eye, but the level of expression varied. Expression was reduced inside the morphogenetic furrow, just before Senseless expression started, and rebounded posterior to the furrow at around column 2 to 3, similar to previous observations made with an antibody (Figure 1A) (Brown et al., 1995).

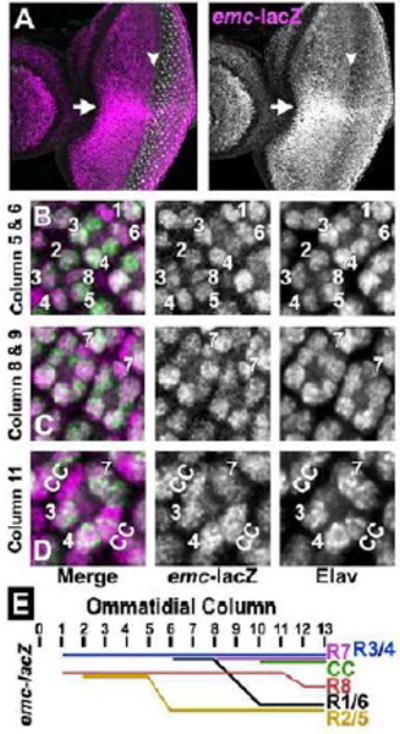

Figure 1. emc-LacZ expression in eye development.

(A) emc-lacZ (P{PZ}emc04322/+) is shown in magenta and R8 photoreceptor cells are visualized by Senseless expression (in green). emc-lacZ is expressed in all cells in the eye imaginal disc. emc-lacZ expression is sharply elevated along the dorso-ventral equator (indicated by white arrow). emc-lacZ expression is higher in the ventral half compared to the dorsal half. LacZ expression is down-regulated at the morphogenetic furrow just before Sens expression starts in the intermediate groups (white arrowhead) and again elevated posterior to furrow around column 2 to 3.

In (B-D) emc-lacZ is shown in magenta and all differentiating neurons are marked by Elav expression (in Green).

(B) In column 5, lacZ is expressed mainly in R3/ R4 and at a lower level in R2/ R5 and R8 cells. In column 6, lacZ expression is higher in R3/ R4 and in R1/ R6.

(C) emc-lacZ expression in R7 in columns 8 to 9.

(D) By column 11 to 12, lacZ expression is higher in R3/R4 and R7 than in other photoreceptor cells. Cone cells also express elevated emc-lacZ.

(E) Schematic representation of dynamic emc-lacZ levels in ommatidial cells posterior to the morphogenetic furrow.

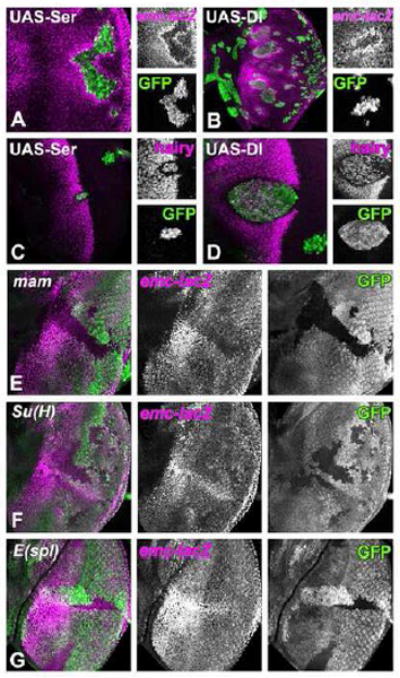

Figure 2. emc-LacZ transcription is regulated by Notch.

Clones of cells over-expressing either Ser (A and C) or Dl (B and D) are identified by the presence of GFP (green) in third instar eye imaginal discs.

(A) emc-lacZ expression (in magenta) is elevated in cells adjacent to the Ser over-expressing clones, while lacZ expression is autonomously reduced inside the clone.

(B) emc-lacZ expression (in magenta) is elevated in neighboring cells to Dl over-expressing clones, while lacZ expression is autonomously reduced inside the clone. Note that the range at which Dl induces emc-lacZ is greater than that of Ser. Dl non-autonomy also extends beyond neighboring cells in loss of function experiments. (Baker and Yu, 1997)

(C) Hairy expression (in magenta) is lost from cells surrounding the Ser over-expressing clones, while expression is maintained inside the clone.

(D) Hairy expression (in magenta) is suppressed in cells adjacent to the Dl overexpressing clone.

Mutant clones in panels (E-G) are visualized by the loss of GFP expression (green). emc-lacZ expression is shown in magenta.

(E) emc-lacZ expression is autonomously reduced in the absence of mam. No elevation occurs in equatorial cells mutant for mam.

(F) emc-lacZ expression is reduced in the absence of Su(H).

(G) emc-lacZ expression is not reduced in the absence of E(spl)-Complex. Neither the basal level if emc-LacZ nor higher emc-LacZ near the equator are affected in the two clones shown here.

Genotypes: (A) ywhsF; UAS-Ser/+; act>CD2>GAL4, UAS-GFP/ P{PZ}emc04322; (B) ywhsF; UAS-Dl/+; act>CD2>GAL4, UAS-GFP/ P{PZ}emc04322; (C) ywhsF; UAS-Ser / +; act>CD2>GAL4, UAS-GFP/+; (D) ywhsF; UAS-Dl/+; act>CD2>GAL4, UAS-GFP/+; (E) ywhsF; FRT42 mam10/ FRT42 [UbiGFP]; P{PZ}emc04322/+; (F) ywhsF; Su(H)Δ47 [w+ l(2)35Bg+] FRT40/ [UbiGFP] FRT40; P{PZ}emc04322/+; (G) ywhsF; P{PZ}emc04322 FRT82 E(spl)grob32.2p[gro+]/ FRT82 [UbiGFP].

Anterior to the morphogenetic furrow, emc-lacZ expression was higher in the ventral disc compared to the dorsal disc, and especially elevated along the dorso-ventral equator. Posterior to the morphogenetic furrow, emc-lacZ levels remained constant in undifferentiated cells that have basal nuclei, but were dynamic in differentiating ommatidial cells (Figure 1E). As soon as R3, R4 and R8 nuclei were identified by Elav expression, their emc-lacZ levels were at a high level similar to that of basal nuclei of undifferentiated cells. In addition, emc-lacZ was sometimes even higher in R4 than in R3. R2 and R5 cells always had lower emc-lacZ levels. emc-lacZ was high in R1/R6 nuclei when first identified around column 6, but decreased from column 8 onwards (Figure 1B, C). By contrast, emc-lacZ was high in nuclei of R7 and cone cell precursors from their appearance in columns 8 and 10, respectively (Figure 1C, D). emc-lacZ remained high in R3/R4 and R7 photoreceptors and in cone cells (Figure 1D), while dropping in R8 cells (Figure 1E). In conclusion, emc transcription was often elevated where Notch signaling is required, such as at the equator, and in the developing R4, R7 and cone cells.

An emc transcription reporter is elevated by Notch signaling

The emc-lacZ pattern was not what was expected if emc transcription is repressed by Notch signaling (Baonza and Freeman, 2001). The relationship between Notch signaling and emc expression was investigated using clones of cells ectopically expressing Notch ligands Delta (Dl) and Serrate (Ser), repeating the work of Baonza and Freeman (2001). We found that emc-lacZ expression was elevated non-autonomously in cells surrounding ligand-expressing clones, regardless of location in the eye imaginal disc (Figure 2A,B). Expression of Dl or Ser also led to autonomous down-regulation of emc-lacZ expression inside the clone. Both results indicate induction of emc-lacZ by Notch signaling. Notch signaling is increased in cells adjacent to the clones expressing Dl or Ser, while cis-inactivation of Notch signaling inside the clone reduced emc-lacZ expression. For comparison, we also examined hairy, a gene that is repressed by Notch signaling (Baonza and Freeman, 2001; Fu and Baker, 2003). Clonal over-expression of Dl or Ser repressed hairy non-autonomously, while hairy expression was maintained within the clones (Figure 2C,D). Notch ligands clearly had opposite effects on expression of emc and hairy, non-autonomously inducing emc-LacZ but repressing hairy.

We further analyzed emc-lacZ expression in mutant clones of Notch pathway genes, including mam, a transcriptional co-activator of Notch (Bray, 2006). Cells mutant for mam had lower expression of emc-lacZ (Figure 2E). When mam mutant clones spanned the equator, emc-lacZ was no longer elevated compared to other regions (Figure 2E). Similar results were observed in clones of cells mutant for Su(H), the transcription factor of the Notch pathway (Bray, 2006)(Figure 2F). By contrast, emc-lacZ expression was affected little in clones of cells mutant for the E(spl)-Complex, and E(spl)-C clones still elevated emc-lacZ at the equator (Figure 2G). The E(spl)-C encodes multiple bHLH proteins that are transcribed by Su(H) and Mam to mediate gene repression in response to Notch (Bray, 2006). Taken together, these results indicate that a basal level of emc-LacZ expression occurs independently of Notch, but that Notch signaling elevates emc-LacZ near the equator and posterior to the furrow. Thus, the eye disc resembles developing wings and ovaries, where Notch signaling also stimulates emc-LacZ expression (Baonza et al., 2000; Adam and Montell, 2004). Notch regulation of emc-LacZ depended on Su(H) and Mam, but not on E(spl).

Expression of the emc transcript and protein

Enhancer trap expression may reflect only a subset of endogenous regulation, and be affected by the stability of the reporter protein, so it was important to examine endogenous gene expression. In situ hybridization with an anti-sense probe for the transcribed region revealed widespread transcription that was reduced in the morphogenetic furrow region but otherwise appeared uniform (Figure 3A, B). Negative control hybridizations with sense strand probes, and positive control hybridizations of wing discs with emc and of eye discs with string (stg) provided confidence that this signal reflected emc transcript (Supplemental Figure S1).

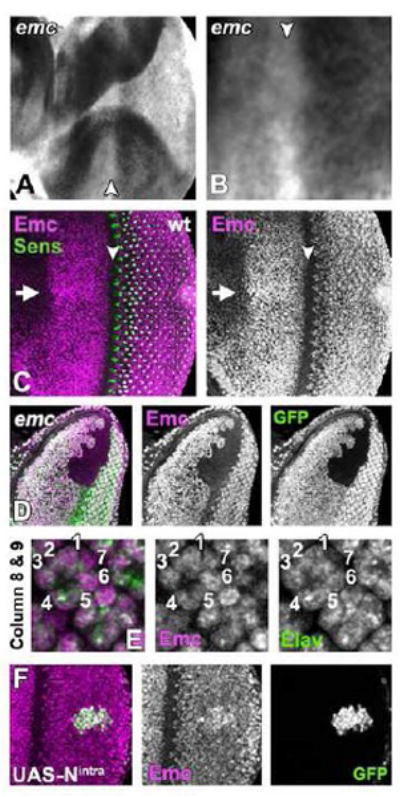

Figure 3. Expression of emc transcript and protein.

(A) In situ hybridization detected emc transcript in cells anterior and posterior to the furrow, but little in the morphogenetic furrow (arrowhead).

(B) An enlargement of the morphogenetic furrow region (arrowhead), showing the emc transcript down-regulation.

(C) Emc protein (magenta) is expressed in all cells anterior to and posterior to the furrow (arrowhead), but absent from the furrow before Sens expression starts (green) and again elevated posterior to furrow, first in cells between precluster groups similar to the upregulation of emc transcript. Emc is elevated along the dorso-ventral equator (arrow).

(D) Anti-Emc antibody labelling (magenta) is completely absent from emc null clones (marked by the absence of GFP).

(E) Emc protein (magenta) is almost expressed equally in differentiating photoreceptor cells (Elav expression in green). Columns 8-9 are shown.

(F) Emc protein (magenta) is elevated in cells over-expressing activated Notch and GFP (green).

Genotypes: (A-C and E) w; (D) ywhsF; emcAP6 FRT80/ [UbiGFP] M(3)67C FRT80 and (F) ) ywhsF; UAS-Nintra/+; act>CD2>GAL4, UAS-GFP/+.

A polyclonal antiserum revealed a distribution of Emc protein similar to the transcript (Brown et al., 1995) (Figure 3C). Protein was detected in nuclei of all cells anterior to and posterior to the morphogenetic furrow, but absent from the furrow itself. As seen with enhancer traps, Emc protein was higher near the equator. Unlike the enhancer traps, Emc protein levels appeared relatively uniform in all nuclei posterior to the furrow (Figure 3E). Protein distribution was the same in eye discs heterozygous for the emc-LacZ, which is a hypomorphic emc allele (Supplemental Figure S2). The antibody was specific, as no labeling of emc mutant clones was detected (Figure 3D).

Unlike emc-LacZ, Emc protein expression was not affected in Su(H) null mutant clones; they expressed normal levels of Emc protein, regardless of position within the eye disc (data not shown). By contrast, over-expression of the Notch intracellular domain led to increased levels of Emc protein in many cells (Figure 3F). These studies confirm that Notch signaling does not repress Emc expression, but suggest that Notch signaling contributes less to the endogenous level of expression than was indicated by enhancer trap studies, although ectopic Notch can increase Emc expression. We will return to the difference between emc-LacZ and Emc protein in the Discussion.

emc is required for eye patterning but not cell viability

Previously, emc null mutations were reported to be cell lethal in imaginal discs (Garcia Alonso and Garcia-Bellido, 1988; de Celis et al., 1995; Campuzano, 2001). We found that when clones of cells homozygous for null allele emcAP6 were induced in a background heterozygous for a Minute (M) mutation, so that the emc mutant cells had a growth advantage (Morata and Ripoll, 1975), homozygous emc null cells survived in the larval and pupal stages. In experiments that made use of constitutive flipase (eyeless-FLP) (Figure 4C-E) to recombine almost all M/emc cells to either emc/emc or M/M genotypes, it was even possible to study eye imaginal discs almost entirely comprised of emc null cells, the M/M genotype being cell lethal.

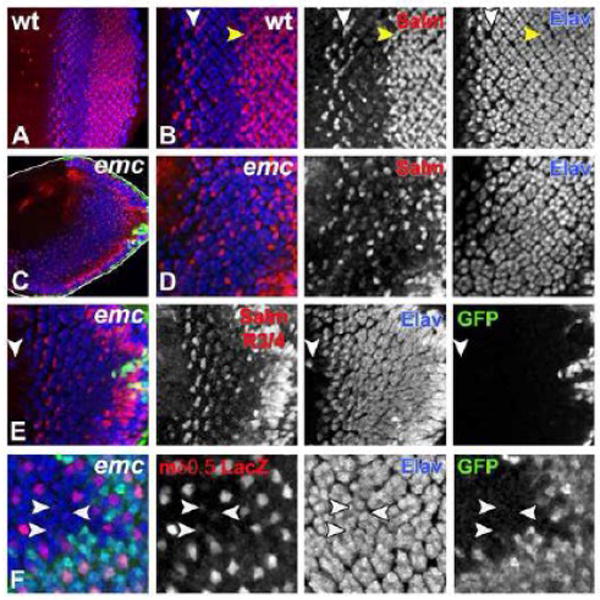

Figure 4. emc is Required for Eye Patterning.

Developing third instar eye imaginal disc is shown with anterior to the left and with dorsal side up. emc mutant clones in (C-F) are marked by the absence of GFP (in green). All differentiating neurons are marked by Elav (in blue).

(A) Wild type developing third instar eye imaginal disc is shown, where Salm (in red) labels developing R3/ R4 photoreceptors, R7 photoreceptors and cone cells.

(B) An enlargement of the image shown in (A), where white arrowhead indicates Salm expression (in red) in developing R3/ R4 photoreceptor pair and yellow arrowhead indicates Salm expression in R7 photoreceptors and cone cells.

(C) In absence of emc morphogenetic furrow (MF) progression is accelerated in ventral half compared to the dorsal half. Disc outline is highlighted in white.

(D) An enlargement of the image shown in (C), where in absence of emc very few cells differentiate as R7 photoreceptors or cone cells, which are visualized by Salm (in red). This panel shows a projection of the entire R7 and cone cell layers, and includes some Salm expressing R3/R4 pairs. emc mutant ommatidia contain irregular numbers of photoreceptor neurons. The arrangement of ommatidia posterior to the MF is also abnormal.

(E) In eye discs mutant for emc almost all ommatidia rotated in the same direction. Ommatidia in the dorsal eye rotated in the normal direction, but almost all ventral ommatidia rotated in the same direction as the dorsal ommatidia did. This panel shows a projection of the Salm expression in layers containing R3/R4 cells only. Occasionally, ectopic neurons differentiate ahead of the MF (white arrowhead).

(F) R4 photoreceptor specific expression of mδ 0.5-lacZ (in red) is reduced in absence of emc and also lost from some emc ommatidia (white arrowhead). This panel shows a projection of all the R4 layers.

Genotypes: (A, B) w; (C-E) yweyF; emcAP6 FRT80/ [UbiGFP] M(3)67C FRT80; (F) ywhsF; E(spl)mδ 0.5-lacZ ry+/+; emcAP6 FRT80/ [UbiGFP] M(3)67C FRT80.

These emc mutant eye discs differed from wild type in many respects (Figure 4A-E). emc mutant eye discs had an overall narrower shape (Figure 4C). Morphogenetic furrow progression was accelerated in the ventral half compared to that of dorsal half (Figure 4C). Patterning of the developing eye field was severely affected. The number of photoreceptor neurons per ommatidium was irregular as was the arrangement of photoreceptor neurons within ommatidial clusters (Figure 4D). Occasionally, ectopic Elav positive differentiating neurons were seen ahead of the morphogenetic furrow (Figure 4E).

When emc mutant eye discs were labeled with Spalt major (Salm) (Figure 4D), a marker for R7 photoreceptor cells, cone cells, and R3/R4 cells (Domingos et al., 2004), we observed almost complete loss of R7 photoreceptor cells and a significant reduction in cone cell numbers (compare Figs. 4B and 4D). Another defect concerned ommatidial rotation. In emc mutant eye discs, ommatidia rotated normally in the dorsal half, but whereas in wild type ommatidia in the ventral eye rotate oppositely, almost all ventral ommatidia in emc mutant eye rotated in the same direction as in the dorsal half (compare Figs 4B and 4E). R4 photoreceptor specification was also affected. This was clear in smaller emc clones produced by inducible flipase (hsp70-FLP). Activation of Notch signaling and subsequent development of R4 photoreceptor cells can be monitored using the mδ 0.5-lacZ transgene (Cooper and Bray, 1999). The expression of mδ 0.5-lacZ was occasionally reduced or absent from presumptive R4 photoreceptor cells that were emc mutant (23% of 287 ommatidia; Figure 4F). It is unlikely that failed R4 differentiation is responsible for the ommatidial rotation defect, because the R4 phenotype was less penetrant and not limited to the ventral ommatidia. These observations showed that Emc activity was required for multiple aspects of Drosophila eye development, many of which are also known to be regulated by Notch signaling.

Emc activity is required autonomously to maintain R7 photoreceptor cell fate

Detailed analysis focused on R7 development, where emc mutations had highly penetrant effects. R7 specification requires Notch signaling to direct R7 cells away from R1 or R6 fates (Cooper and Bray, 2000; Tomlinson and Struhl, 2001). If emc was required for Notch signaling in this decision, then we would expect that absence of emc should result in cell-autonomous failure of all aspects of R7 photoreceptor specification, that emc mutant cells should develop as R1 or R6 cells, and that emc mutations should be epistatic to Notch activity.

To examine the role of emc further, we analyzed R7 development in emc null clones with additional R7 photoreceptor markers, and clones that were induced using hsFLP occupied only part of the retina, so that cell-autonomy could be assessed. The presumptive R7 cells could be identified by position, since they continue to express Elav. Runt is expressed in R8 photoreceptor cells from column 1 onwards and in R7 photoreceptor cells from column 8 or 9 onwards (Kaminker et al., 2002). In emc mutant ommatidia, Runt was lost from 97% of the presumptive R7 photoreceptor cells (n=87), while R8 photoreceptor cells continued to express Runt (Figure 5A). The emc mutant R7 photoreceptor cells maintained their neuronal identity, as they remained positive for the neuronal marker Elav. In wild type, Prospero (Pros) is expressed in R7 photoreceptor cells from column 7 or 8 onwards (Kauffmann et al., 1996). Inside emc mutant clones Pros expression in R7 cells began at a reduced level and disappeared 2 to 3 columns later (Figure 5B). In wild type, Salm expression starts in R7 at column 9 (Domingos et al., 2004), but in emc clones Salm disappeared after 2 to 3 columns (data not shown). All these effects on R7 were cell-autonomous. These observations confirm that emc is required for the appropriate differentiation of R7 photoreceptor cells. The transient expression of Pros and Salm suggested that emc might be more important for the maintenance of R7 fate than for its initiation.

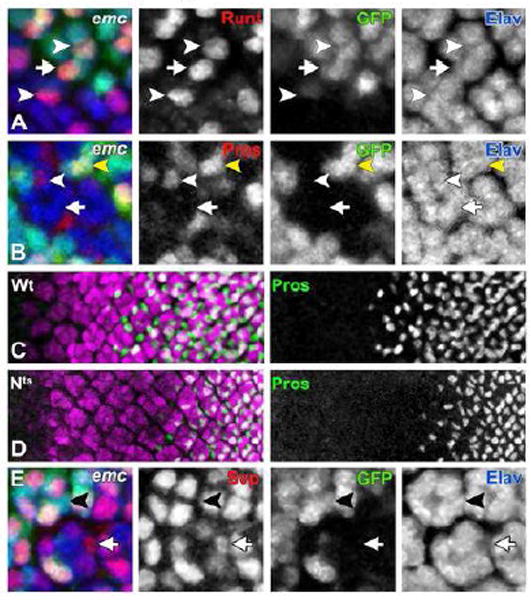

Figure 5. emc is Required for R7 Photoreceptor Differentiation.

In (A, B and E) all differentiating neurons are marked by Elav (in blue) and emc mutant cells are identified by the absence of GFP expression (in green).

(A) Runt (in red) is expressed in R7 (white arrow) and R8 (white arrowhead) photoreceptor cells outside emc clone. Inside emc clone, Runt expression is autonomously lost from R7 cells, while expression in R8 cells remains unaffected (white arrowhead).

(B) Pros expression (in red) in presumptive R7 photoreceptor cells initiates in emc mutant ommatidia (white arrowhead) at a much-reduced level compared to the Pros expression level in R7 cells outside the clonal boundary (yellow arrowhead). This Pros expression in emc mutant R7 cells disappears after 2-3 columns. White arrow points to a Pros negative emc mutant cell in the R7 position.

In panels (C) and (D), all differentiating neurons are visualized by Elav (in magenta). R7 and cone cells are labeled in green (anti-Pros).

(C) Pros expression in R7 cells in wild type eye imaginal disc starts from column 7-8.

(D) Nts animals are exposed to the restrictive temperature for 3 hours before dissection. Pros expression in R7 and cone cells in these flies is delayed by 2 columns starting from column 9-10, but continues even in presence of reduced N signaling.

(E) Svp (in red) in non-mutant ommatidia is expressed in R3/R4 and R1/R6 cells, but not in R7 cells (black arrowhead). In emc mutant ommatidia presumptive R7 cells occasionally express Svp (white arrow).

Genotypes: (A, B and E) ywhsF; emcAp6 FRT80/ [UbiGFP] M(3)67C FRT80; (C) w and (D) Nts/Y.

The role of Notch signaling was re-examined to evaluate both R7 initiation and maintenance. In Nts animals shifted to the restrictive temperature for 3 hours, which is the time required for the differentiation of about two columns, initiation of Pros expression was delayed by two columns, indicating that Pros expression had not initiated while Notch function was reduced (Figure 5C, D). However, Nts did not affect more posterior columns, where Pros expression had already initiated at the beginning of the temperature shift. We conclude that Notch signaling is required for R7 specification, but not required continuously to maintain R7 fate. These findings suggested that both Notch and emc were required for R7 photoreceptor differentiation, but Notch may be required earlier or more stringently than emc.

Emc mutant R7 cells display R1/6-like properties

If emc, like Notch, is part of the choice of R7 over R1 or R6 fates, then we would expect additional cells to express R1/R6 cell markers inside emc mutant clones. This was tested by examining expression of Sevenup (Svp), which is expressed in R3/R4 and R1/R6 photoreceptor cells (Mlodzik et al., 1990). Inside emc mutant clones the Elav-expressing cells in the R7 position often expressed Svp (47% of 86 ommatidia; Figure 5E). These observations support the idea that emc is part of the Notch signaling pathway required to direct cells towards R7 photoreceptor specification from a default R1/6 pathway.

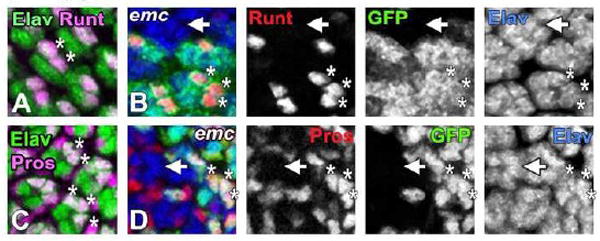

Emc is epistatic to Notch in R7 photoreceptor differentiation

To address the relationship of Emc to Notch signaling, the requirement for emc was examined in ectopic R7 cells. If emc was required downstream of Notch, one would expect that ectopic Notch activity would require emc function to transform R1 and R6 cells into ectopic R7 cells. Eye discs where constitutively active form of Notch, Nact, was expressed under the control of the sevenless enhancer were examined. In sev-Nact flies, Nact is expressed in R3/R4 photoreceptor cells, in the R7 equivalence group of R1/R6, and R7 photoreceptors and in the cone cells, as well as transiently in two “mystery cells” that are later incorporated into the undifferentiated cell pool. Previous studies established that sev-Nact causes development of supernumerary R7 photoreceptor cells in expense of R1/R6 photoreceptor fate (Figure 6A and C) (Cooper and Bray, 2000; Tomlinson and Struhl, 2001). By contrast, 80% of emc mutant ommatidia in sev-Nact background completely lacked R7 expression of Runt (n=107), and the remainder had only one Runt expressing, R7-like cell whereas sev-Nact ommatidia always have 2-3 (Figure 6B). Similar results were obtained with the R7 marker Pros (Figure 6D). These results indicate that emc is epistatic to Notch in R7 differentiation, consistent with the model that emc acts downstream of Notch, or parallel to Notch, during R7 specification.

Figure 6. emc is epistatic to Notch in R7 fate determination.

All neurons are visualized by Elav expression [in (A) and (C) by green and in (B) and (D) by blue]. emc mutant clones in panels (B) and (D) are marked by the absence of GFP expression (in green).

(A) In sev-Nact ommatidia elevated Notch signaling induces Runt expression (in magenta) in R7 cells and in one or both of the R1/R6 cells (white asterisks in a representative ommatidia) and in R8 cells (confocal layers containing R8 nuclei have been omitted for clarity).

(B) In sev-Nact background, most of the emc mutant ommatidia failed to express Runt (in red) in R1/6/7 trio (white arrow). Runt expression in supernumerary R7 cells is maintained in non-mutant ommatidia (white asterisks in one representative ommatidia). Runt expression in R8 cells is not shown.

(C) sev-Nact induces Pros expression (in magenta) in R7 cells and in one or both of the R1/ R6 cells. White asterisks in two representative ommatidia marks such supernumerary R7 cells that are positive for both Pros and Elav. Other Pros positive, but Elav negative cells indicate non-neuronal cone cells.

(D) In emc mutant ommatidia made in sev-Nact background, Pros expression (in red) is lost from most of the R1/6/7 trio (arrowhead). Outside of the clone Pros expression continued in multiple photoreceptor cells (white asterisks in one representative ommatidia). emc mutant non-neuronal cone cells still express Pros.

Genotypes: (A and C) w; Cyo [w+, sev-Nact]/+; (B and D) ywhsF; Cyo [w+, sev-Nact]/+; emcAP6 FRT80/ [UbiGFP] M(3)67C FRT80.

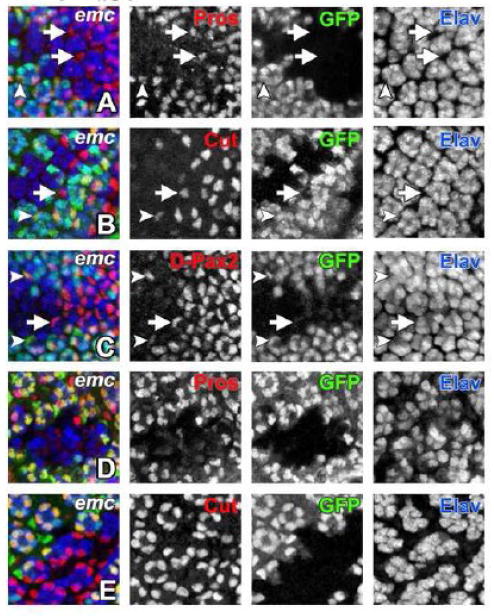

Emc is required for cone cell development

In addition to R7, Notch is also required to specify non-neuronal cone cells (Flores et al., 2000). The Notch pathway is expected to be shared between cone cells and R7 cells, the difference being that R7 cells experience Sevenless signaling in addition. Consistent with this expectation, cone cell markers Salm, Pros, Cut and D-Pax2 (Blochlinger et al., 1993; Kauffmann et al., 1996; Fu and Noll, 1997) were all affected in emc mutant clones. Onset of Pros and Salm expression in cone cells was significantly delayed, by 3 to 4 columns (Figure 7A and data not shown). Onset of Cut and D-Pax2 was delayed by 2 to 3 columns (Figure 7B, C). In addition, the number of differentiating cone cells was reduced. On average, 2.6 cells express Cut and 2.5 cells express D-Pax2 per emc mutant ommatidia (n=45 and n=25, respectively), compared to exactly 4 in wild type. We could see using the nuclear dye DRAQ5 than some ommatidia contained cells in cone cell positions that failed to express cone cell Cut, although in other ommatidia the apical nuclear migration typical of cone cells was either delayed or absent (data not shown). When emc clones were studied in pupal retinas (24 hours APF), 2.2 Cut-expressing cells were found per ommatidium (n=51), and none of these cells expressed Pros or Salm (Figure 7D, E and data not shown). Therefore, emc was required for both the timely onset of cone cell differentiation and number of cells that express cone cell properties, although emc mutations had less penetrant effects on cone cells than on R7 cells.

Figure 7. Cone cell differentiation requires emc.

In all panels emc mutant cells are marked by the absence of GFP expression (in green) and neurons are visualized by Elav expression (in blue).

(A) In emc mutant ommatidia onset of Pros expression (in red) in cone cells is delayed by 3-4 columns (white arrow) compared to non-mutant ommatidia (white arrowhead). There are fewer number of Pros positive cone cells inside the emc clone.

(B) Induction of Cut expression (in red) in emc mutant cone cells is delayed by 2-3 columns (white arrow) than non-mutant ommatidia (white arrowhead). There are also missing cone cells inside emc clone.

(C) Expression of another cone cell marker D-Pax2 (in red) is also delayed by 2-3 columns in emc mutant ommatidia (white arrow) compared to non-mutant ommatidia (white arrowhead). There is also less than regular number of four cone cells per mutant ommatidia.

(D) At 24 hours APF, Pros expression (in red) is completely lost from emc mutant cone cells.

(E) emc mutant cone cells continue to express Cut (in red) at 24 hours APF. At this stage there are still fewer number of cone cells per mutant ommatidia.

Genotype: (A-E) ywhsF; emcAP6 FRT80/ [UbiGFP] M(3)67C FRT80.

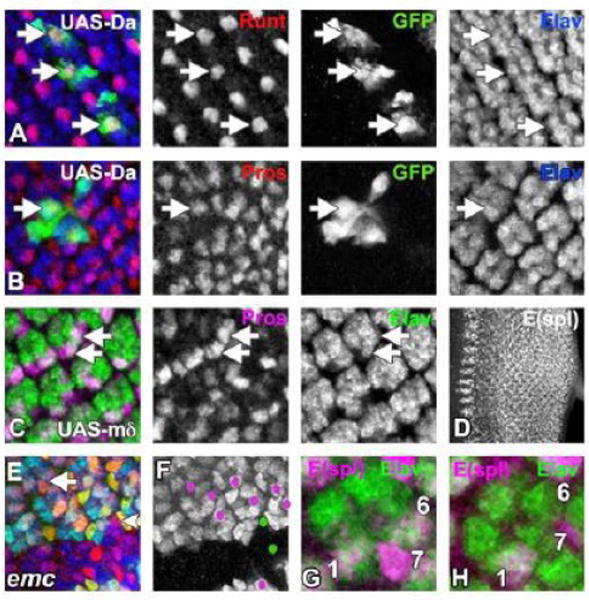

Other bHLH transcription factors in R7 development

Emc inhibits DNA binding by bHLH transcription factors by forming non-functional heterodimers with them (Campuzano, 2001). The requirement for emc therefore suggests that R7 development might depend on a bHLH transcription factor. Emc has been shown to interact with the bHLH protein Daughterless (Da) (Van Doren et al., 1991; Alifragis et al., 1997). Emc might promote R7 development by sequestering Da away from a complex required for R1/6 fate. Da was over-expressed in small flip-out clones to test whether Da redirected R7 cells to R1/6 fates. R7 development was not affected by Da over-expression, as judged from normal Runt and Pros expression (Figure 8A, B). As clones of da mutant cells also form R1, 6 and R7 fate normally (Brown et al., 1996), there is no evidence that da affects R1/6 or R7 development.

Figure 8. Emc and bHLH Proteins in R7 Development.

Clones of cells in third instar eye imaginal discs over-expressing Da (A and B) are identified by the presence of GFP (in green). All differentiating neurons are visualized by Elav expression [in (A-C) and (E) by blue and in (G) and (H) by green].

(A) Runt expression (in red) in R7 photoreceptor cells remained unchanged (white arrow) when Da was over-expressed. For clarity, basal layers where Runt is expressed in R8 cells are omitted.

(B) R7 cells continued to express Pros (in red) even in presence of high levels of Da (white arrow).

(C) E(spl)-mδ is being over-expressed using sev-Gal4. In some ommatidia elevated expression of E(spl)-mδ induces Pros (in red) expression in one or two extra photoreceptor cells in addition to the normal R7 cell (white arrow). In this background, R3/R4 photoreceptor pairs also express Pros (Data not shown).

(D) Wild type developing third instar eye imaginal disc is stained with mAb323, which detects at least 5 of the 7 bHLH transcription of E(spl) family.

(E) An emc mutant clone (lacking GFP in green), labelled for E(spl) protein expression (mAb323 in red) and photoreceptors (Elav in blue). E(spl) expression in emc mutant R7 cells (eg arrowhead) is delayed compared to wild type ommatidia (eg arrow).

(F) The same emc clone as panel (E). E(spl)-expressing cells in the R7 position are indicated by magenta dots out side of the clone and by green dots within the emc clone.

(G) A single ommatidium from wild type eye disc stained with mAb323 (in magenta) is shown. R1, R6 and R7 cells label with mAb323. Elav labels all photoreceptors (in green).

(H) A single emc mutant ommatidium at the same stage as panel (G). Only the R1 cell is labelled by mAb323 (magenta).

Genotypes: (A and B) ywhsF; UAS-Da/+; act>CD2>GAL4, UAS-GFP/+; (C) sev-Gal4/ UAS-E(spl)-mδ (D and G) w; (E, F and H) ywhsF; emcAP6 FRT80/ [UbiGFP] M(3)67C FRT80. For (A-C) flies were raised at 29°C.

The E(spl)-C encodes another class of bHLH proteins, required for many aspects of Notch signaling (Bray, 2006). It has been reported previously that over-expression of E(spl)-mδ with sev-Gal4 caused loss of R1/R6 specification (Cooper and Bray, 2000). We found that some of these cells developed as R7-like cells that expressed Pros and Runt, in 14% [n=612] of ommatidia (Figure 8C). As some of the E(spl)-C proteins are subject to inhibitory phosphorylations that limit their effectiveness in over-expression experiments, and it remains possible that they are involved in normal R7 specification (Karandikar et al., 2004). In normal development, mδ 0.5-lacZ transgene expression was weak and inconsistent in R7 precursors, and an mδ antibody, mAb174, did not label R7 precursors (data not shown). Another antibody, mAb323, detects up to five E(spl) bHLH proteins (Jennings et al., 1994). Several ommatidial cells were labelled by mAb323 (Baker et al., 1996; Dokucu et al., 1996) (Figure 8D). These included R4 cells (column 2/3 to column 6/7), R1/6 cells (column 6 onwards), R7 cells (column 8/9 to columns 15/16), and cone cells (column 10 or 11 onwards) (Figure 8D, and data not shown). The expression of E(spl) proteins detected by mAb323 was delayed by 2 to 3 columns in R7 cells (Figure 8E, F), and sometimes delayed or absent from emc mutant R1/6 cells (Figure 8G-H). Cone cell expression was delayed by 2 to 3 columns (data not shown). Taken together, these findings suggest that Notch signaling acts through E(spl) bHLH genes to specify R7 cells, and that emc is required for R7 fate in part through a contribution to E(spl) bHLH gene expression.

DISCUSSION

Both Notch and emc gene were first discovered through their roles in restricting neurogenesis to particular times and locations. They were thought to antagonize the function of proneural bHLH proteins through independent mechanisms (Campuzano, 2001; Bray, 2006). Notch signaling activates transcription of a set of bHLH repressor proteins encoded at the E(spl) locus, which repress proneural gene transcription, whereas Emc antagonizes proneural protein function through inactive heterodimer formation. Several studies have now suggested greater functional links between Notch and Emc than originally assumed. We confirm through studies of Drosophila eye development that Emc contributes positively to Notch signaling, and report studies of null mutant development that demonstrate that Emc is required for full activation of the E(spl)-C of Notch target genes and for many aspects of Notch signaling.

Notch and emc expression

Our studies using enhancer traps to report emc transcription led to a picture of eye development remarkably similar to that reported for wing and ovary development. In all three tissues, Notch signaling appears to contribute levels of emc transcription that are elevated above a Notch-independent baseline. In the eye, this included elevated emc transcription in the ventral compartment, straddling the boundary between ventral and dorsal compartments, and the maintenance of high emc-LacZ levels in ommatidial cells where Notch signaling occurs, including the R3/R4 equivalence group, the R1/R6/R7 equivalence group, and the cone cells. Transcriptional stimulation required Su(H) and mam, but not E(spl), placing Notch activation of emc parallel to Notch activation of E(spl), similar to the wing and ovary (Baonza et al., 2000; Adam and Montell, 2004).

The effect of Notch signaling in the eye on emc-LacZ reporters has been studied previously, but with an opposite interpretation that Notch represses emc (Baonza and Freeman, 2001). We have performed ligand ectopic-expression experiments similar to those of the previous authors. They did not note the non-autonomous activation of emc-LacZ by ectopic Dl (although it is visible in their figures), and interpreted the modest autonomous reduction of emc-LacZ as an effect of Notch activity rather than of cis-inactivation. We are confident that our interpretation that Notch activates emc-LacZ expression is correct, because this is supported by the cell autonomous effects of ectopic Notch-intra expression and of mam and Su(H) loss-of-function clones, and also by studies of hairy, a gene that there is agreement that Notch represses(Baonza and Freeman, 2001)(Fu and Baker, 2003). Baonza and Freeman also claimed that Ser was unable to regulate emc-LacZ, contrary to our results, but they relied on a UAS-Ser strain that we have found to be very weak (see Li and Baker, 2004 for comparison of UAS-Ser transgenes). The evidence that we now present clearly shows that emc is not repressed by Notch signaling during eye development, and this also undermines the suggestion that downregulating emc is the mechanism of the ‘proneural enhancement’ function of Notch (Baonza and Freeman, 2001).

We also examined emc expression directly by in situ hybridization and antibody studies. Unexpectedly, some of the modulation seen with enhancer traps was not seen at the RNA or protein levels. Given that Notch regulation of emc enhancer traps has now been reported in three independent studies, and with three independent enhancer trap insertions, it seems likely that there is in fact an input of Notch signaling on emc transcription. This might not be detected through studies of the RNA or protein because of exaggerated sensitivity to some aspects of transcriptional regulation by enhancer traps, stability of the Emc protein rendering protein levels less sensitive to changes in transcription levels, or to homeostatic mechanisms that acts post-transcriptionally. It is not certain that the contribution of Notch-regulation of emc to Notch or emc function is very significant, however, although it could contribute to robustness or dynamic aspects.

Requirement for emc in eye patterning

Studies of hypomorphic emc mutations revealed only subtle effects during eye development (Brown et al., 1995). It had been thought that complete absence of emc function could not be studied due to cell lethality. However, using the Minute technique to provide an advantageous environment permitted cells lacking emc function to survive until late pupal stages, indicating that emc is not essential for survival at all stages. Although emc is likely to have roles in cell growth and survival, this paper focuses on post-mitotic cells. Loss of emc affected morphogenetic furrow movement, specification of R4, R7, and cone cells, and ommatidial rotation. All these processes are also regulated by Notch activity (Baker and Yu, 1997; Fanto and Mlodzik, 1999; Cooper and Bray, 2000; Baonza and Freeman, 2001; Tomlinson and Struhl, 2001). Whereas Notch is generally essential, the degree of requirement for emc varied from stringent in the case of R7 cells to mild in the case of R4 cells. Notably, lateral inhibition of R8 cells depends strictly on Notch (Baker, 2002; Frankfort and Mardon, 2002), but was not detectably affected by emc mutations.

emc, Notch and differentiation of ommatidial cells

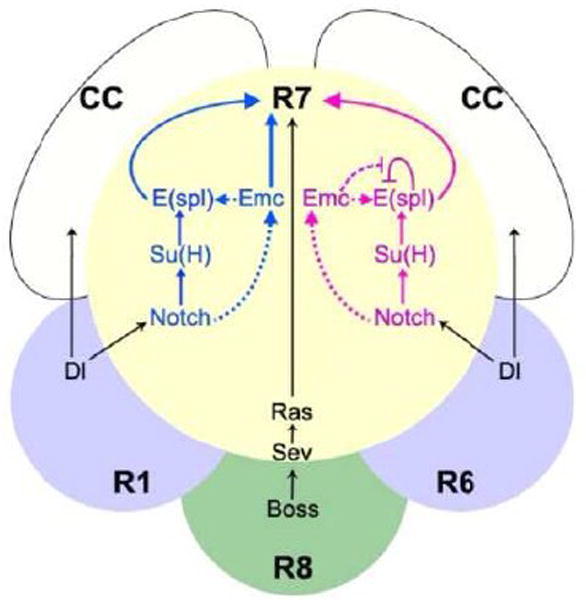

R7 photoreceptor differentiation failed almost completely in emc mutant clones. Our results support the idea that emc contributes to the specification of R7 cells by Notch (Figure 9). First, the requirement for emc in R7 development was cell-autonomous, as expected for an effector of R7 fate. Secondly, emc mutant cells failing to differentiate as R7 often expressed R1/6-like characteristics, similar to cells that lack Notch signaling. Although we could not obtain emc null cells in the adult, it is worth mentioning that a previous study of the hypomorphic emc1 allele illustrated adult cells with R1/6-like morphology in the position that would normally be occupied by R7 (see Figure 2A of (Brown et al., 1995). Thirdly, emc function was required for ectopic Notch activity to transform R1/6 cells to R7 fates. Such epistasis is consistent with emc function downstream of or parallel to Notch. Finally, because Notch activity normally defines R7 fate in combination with Sevenless activity, and cells that activate only Notch become non-neuronal cone cells, it was expected that emc would also be required for cone cell differentiation, as proved to be the case.

Figure 9. Model for the contribution of Emc to R7 specification.

R7 photoreceptor specification occurs in response to signaling from R8 through Boss and Sevenless, and signaling from R1 and R6 through Delta and Notch. Emc acts downstream or parallel to Notch in R7 photoreceptor development as well as in cone cells. The ‘blue’ and ‘magenta’ models shown are not mutually exclusive. In the ‘blue’ model, Notch signals through Su(H) to E(spl), and Emc acts in parallel to specify R7 fate. In the ‘magenta’ model, Emc acts by permitting E(spl) expression, perhaps through antagonizing E(spl) auto-repression. N signaling has an effect on emc transcription but not on Emc protein levels. We suppose that the role of Emc in cone cell development is mechanistically similar to its role in R7.

There were differences between emc and Notch mutant phenotypes. Some R7 markers were transiently expressed in emc mutant cells, at lower than normal levels, but this initial R7-like development was not maintained. Initial R7-like development was not seen in Notch mutations. Another difference was noted in cone cell development: Notch was essential, but emc mutations reduced cone cell differentiation by 40%. The expression of R1/6 markers by emc mutant R7 cells also occurred less frequently than when Notch itself was mutated. Taken together, these data suggest that Notch signaling in R7 and cone development depends on emc in part. Consistent with this, we were not able to mimic Notch signaling and to convert R1/6 cells into R7 through ectopic emc expression. One simple model is that emc and E(spl)-C genes act in parallel to induce cone cell and R7 cell fates (‘blue’ model in Figure 9). However, at least some E(spl) gene expression depends on emc, consistent with a more direct role for emc in Notch signaling.

Emc and bHLH Transcription factors

Emc is a HLH protein that functions by competitive inhibition of bHLH transcription factors through inactive heterodimer formation (Campuzano, 2001). The main Class II proneural bHLH protein known to function in eye development is Atonal (Jarman et al., 1994; Baker, 2002; Frankfort and Mardon, 2002). There was little requirement for emc in the specification of R8 cells by Ato. There could be other proneural genes similar to ato whose role in eye development is not yet known, but so far all Class II proteins have required the Class I bHLH transcription factor Da. Da can also act as a homodimer, without Class II partners, but Emc protein also heterodimerizes with and inactivates Da. All in all, it is expected that any effect of emc loss-of-function on proneural bHLH proteins should be mimicked by Da over-expression. We found that R7 cells were unaffected by Da over-expression. Although the level of over-expression could have been insufficient, genetic mosaic analysis shows that da is dispensable for R1/6 development (Brown et al., 1996). These observations raise the possibility that emc might function independently of proneural bHLH genes (Figure 9).

Recently, it’s been reported that the chick Emc homolog Id1 heterodimerizes with Hes1, a chick homolog of E(spl). The effect is to oppose Hes1 auto-repression, prolonging the Hes1-mediated response to Notch (Bai et al., 2007). E(spl) gene may auto-repress in Drosophila also (Kramatschek and Campos-Ortega, 1994; Oellers et al., 1994), and although it has been claimed that Emc does not heterodimerize with E(spl) bHLH proteins (Baonza et al., 2000), we did find that emc was required for the proper level and timing of E(spl) expression in multiple cell types (Figure 8). Our results suggest that Emc acts at least in part through bHLH proteins that are encoded by the E(spl)-C (Figure 9, ‘magenta’ model), although we do not know the molecular mechanism connecting Emc and the E(spl)-C. Because we found examples where E(spl) expression was delayed in emc mutant cells, our results suggest that emc may accelerate and intensify the response to Notch, rather than prolonging the response as in the chick. To the extent that emc expression may be activated by Notch signaling, this could represent a ‘feed-forward’ class of regulatory mechanism (Alon, 2007).

Conclusions

The study of emc null mutant clones shows that, in addition to contributing to a prepattern that defines where proneural potential can develop, emc also contributes to multiple episodes of Notch signaling in eye development. Although the contribution of Notch signaling to emc expression is probably small, and is not detectable at the protein level, Emc is nevertheless essential for normal Notch signaling. One mechanism for emc function is through its requirement for the expression of genes in the E(spl)-C that are the main effectors of Notch signaling. These findings suggest that some of the roles of Id genes in mammalian differentiation and cancer may be related to Notch signaling, which also inhibits differentiation and is implicated in cancer (Aster et al., 2008; Watt et al., 2008).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank P. M. Domingos, P. Heitzler, R. Mann and the National Drosophila Stock Center at Bloomington for Drosophila strains. We thank P. M. Domingos, Y. N. Jan, H. Bellen, S. Bray and the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank for antibodies. We thank P. M Domingos and A. Jenny for comments on the manuscript. Supported by a Grant from the NIH (GM47892). Data in this paper are from a thesis to be submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Phiosophy in the Graduate Division of Biomedical Sciences, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Yeshiva University, USA.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adam JC, Montell DJ. A role for extra macrochaetae downstream of Notch in follicle cell differentiation. Development. 2004;131:5971–80. doi: 10.1242/dev.01442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alifragis P, Poortinga G, Parkhurst SM, Delidakis C. A network of interacting transcriptional regulators involved in Drosophila neural fate specification revealed by the yeast two-hybrid system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:13099–104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.13099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alon U. Network motifs: theory and experimental approaches. Nature. 2007;450:450–461. doi: 10.1038/nrg2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aster JC, Pear WS, Blacklow SC. Notch signaling in leukemia. Annual review of Pathology. 2008;3:587–613. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathmechdis.3.121806.154300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai G, Sheng N, Xie Z, Bian W, Yokota Y, Benezra R, Kageyama R, Guillemot F, Jing N. Id sustains Hes1 expression to inhibit precocious neurogenesis by releasing negative autoregulation of Hes1. Dev Cell. 2007;13:283–97. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker NE, Yu S, Han D. Evolution of proneural atonal expression during distinct regulatory phases in the developing Drosophila eye. Current Biology. 1996;6:1290–1301. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)70715-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker NE, Yu S. Proneural function of neurogenic genes in the developing Drosophila eye. Current Biology. 1997;7:122–132. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00056-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker NE. Notch and the patterning of ommatidial founder cells in the developing Drosophila eye. Results and Problems in Cell Differentiation. 2002;37:35–58. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-45398-7_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baonza A, de Celis JF, Garcia-Bellido A. Relationships between extramacrochaetae and Notch signalling in Drosophila wing development. Development. 2000;127:2383–93. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.11.2383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baonza A, Freeman M. Notch signalling and the initiation of neural development in the Drosophila eye. Development. 2001;128:3889–98. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.20.3889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blochlinger K, Jan LY, Jan YN. Postembryonic patterns of expression of cut, a locus regulating sensory organ identity in Drosophila. Development. 1993;117:441–50. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.2.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand AH, Perrimon N. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development. 1993;118:401–415. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.2.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray SJ. Notch signalling: a simple pathway becomes complex. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:678–89. doi: 10.1038/nrm2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown NL, Sattler CA, Paddock SW, Carroll SB. Hairy and emc negatively regulate morphogenetic furrow progression in the Drosophila eye. Cell. 1995;80:879–87. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90291-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown NL, Paddock SW, Sattler CA, Cronmiller C, Thomas BJ, Carroll SB. Daughterless is required for Drosophila photoreceptor cell determination, eye morphogenesis, and cell cycle progression. Developmental Biology. 1996;179:65–78. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cagan RL, Ready DF. Notch is required for successive cell decisions in the developing Drosophila retina. Genes Dev. 1989;3:1099–112. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.8.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campuzano S. Emc, a negative HLH regulator with multiple functions in Drosophila development. Oncogene. 2001;20:8299–8307. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper MT, Bray SJ. Frizzled regulation of Notch signalling polarizes cell fate in the Drosophila eye. Nature. 1999;397:526–30. doi: 10.1038/17395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper MT, Bray SJ. R7 photoreceptor specification requires Notch activity. Curr Biol. 2000;10:1507–10. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00826-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Celis JF, Baonza A, Garcia-Bellido A. Behavior of extramacrochaetae mutant cells in the morphogenesis of the Drosophila wing. Mech Dev. 1995;53:209–21. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(95)00436-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Celis JF, de Celis J, Ligoxygakis P, Preiss A, Delidakis C, Bray S. Functional relationships between Notch, Su(H) and the bHLH genes of the E(spl) complex: the E(spl) genes mediate only a subset of Notch activities during imaginal development. Development. 1996;122:2719–28. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.9.2719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doe CQ, Skeath JB. Neurogenesis in the insect nervous system. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1996;6:18–24. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(96)80004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dokucu ME, Zipursky SL, Cagan RL. Atonal, Rough and the resolution of proneural clusters in the developing Drosophila retina. Development. 1996;122:4139–4147. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.12.4139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domingos PM, Brown S, Barrio R, Ratnakumar K, Frankfort BJ, Mardon G, Steller H, Mollereau B. Regulation of R7 and R8 differentiation by the spalt genes. Dev Biol. 2004;273:121–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doroquez DB, Rebay I. Signal integration during development: mechanisms of EGFR and Notch pathway function and cross-talk. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2006;41:339– 85. doi: 10.1080/10409230600914344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy JB, Kania MA, Gergen JP. Expression and function of the Drosophila gene runt in early stages of neural development. Development. 1991;113:1223–30. doi: 10.1242/dev.113.4.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis HM, Spann DR, Posakony JW. Extramacrochaetae, a negative regulator of sensory organ development in Drosophila, defines a new class of helix-loophelix proteins. Cell. 1990;61:27–38. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90212-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis HM. Embryonic expression and function of the Drosophila helix-loop-helix gene, extramacrochaetae. Mech Dev. 1994;47:65–72. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(94)90096-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanto M, Mlodzik M. Asymmetric Notch activation specifies photoreceptors R3 and R4 and planar polarity in the Drosophila eye. Nature. 1999;397:523–6. doi: 10.1038/17389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firth LC, Li W, Zhang H, Baker NE. Analyses of RAS regulation of eye development in Drosophila melanogaster. Methods Enzymol. 2006;407:711–21. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)07056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firth LC, Baker NE. Spitz from the retina regulates genes transcribed in the second mitotic wave, peripodial epithelium, glia and plasmatocytes of the Drosophila eye imaginal disc. Dev Biol. 2007;307:521–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.04.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores GV, Duan H, Yan H, Nagaraj R, Fu W, Zou Y, Noll M, Banerjee U. Combinatorial signaling in the specification of unique cell fates. Cell. 2000;103:75–85. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00106-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortini ME, Rebay I, Caron LA, Artavanis-Tsakonas S. An activated Notch receptor blocks cell-fate commitment in the developing Drosophila eye. Nature. 1993;365:555–7. doi: 10.1038/365555a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankfort BJ, Mardon G. R8 development in the Drosophila eye: a paradigm for neural selection and differentiation. Development. 2002;129:1295–1306. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.6.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryer CJ, White JB, Jones KA. Mastermind recruits CycC:CDK8 to phosphorylate the Notch ICD and coordinate activation with turnover. Mol Cell. 2004;16:509– 20. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu W, Noll M. The Pax2 homolog sparkling is required for development of cone and pigment cells in the Drosophila eye. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2066–78. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.16.2066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu W, Baker NE. Deciphering synergistic and redundant roles of Hedgehog, Decapentaplegic and Delta that drive the wave of differentiation in Drosophila eye development. Development. 2003;130:5229–39. doi: 10.1242/dev.00764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuerstenberg S, Giniger E. Multiple roles for notch in Drosophila myogenesis. Dev Biol. 1998;201:66–77. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.8944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Alonso LA, Garcia-Bellido A. Extramacrochaetae, a trans-acting gene of the Achaete-Scute Complex of Drosophila involved in cell communication. Roux’s Archives of Developmental Biology. 1988;197:328–338. doi: 10.1007/BF00375952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrell J, Modolell J. The Drosophila extramacrochaetae locus, an antagonist of proneural genes that, like these genes, encodes a helix-loop-helix protein. Cell. 1990;61:39–48. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90213-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan B, Vassin H. Regulatory interactions during early neurogenesis in Drosophila. Dev Genet. 1996;18:18–27. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6408(1996)18:1<18::AID-DVG3>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heitzler P, Bourouis M, Ruel L, Carteret C, Simpson P. Genes of the Enhancer of split and achaete-scute complexes are required for a regulatory loop between Notch and Delta during lateral signalling in Drosophila. Development. 1996;122:161–71. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.1.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinz U, Giebel B, Campos-Ortega JA. The basic-helix-loop-helix domain of Drosophila lethal of scute protein is sufficient for proneural function and activates neurogenic genes. Cell. 1994;76:77–87. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90174-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iavarone A, Lasorella A. Id proteins in neural cancer. Cancer Letters. 2004;204:189–196. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3835(03)00455-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janody F, Lee JD, Jahren N, Hazelett DJ, Benlali A, Miura GI, Draskovic I, Treisman JE. A mosaic genetic screen reveals distinct roles for trithorax and polycomb group genes in Drosophila eye development. Genetics. 2004;166:187–200. doi: 10.1534/genetics.166.1.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarman AP, Grell EH, Ackerman L, Jan LY, Jan YN. Atonal is the proneural gene for Drosophila photoreceptors. Nature. 1994;369:398–400. doi: 10.1038/369398a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings B, Preiss A, Delidakis C, Bray S. The Notch signalling pathway is required for Enhancer of split bHLH protein expression during neurogenesis in the Drosophila embryo. Development. 1994;120:3537–3548. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.12.3537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jönsson F, Knust E. Distinct functions of the Drosophila genes Serrate and Delta revealed by ectopic expression during wing development. Dev Genes Evol. 1996;206:91–101. doi: 10.1007/s004270050035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminker JS, Canon J, Salecker I, Banerjee U. Control of photoreceptor axon target choice by transcriptional repression of Runt. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:746–50. doi: 10.1038/nn889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanai MI, Okabe M, Hiromi Y. Seven-up controls switching of transcription factors that specify temporal identities of Drosophila neuroblasts. Dev Cell. 2005;8:203–13. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karandikar UC, Trott RL, Yin J, Bishop CP, Bidwai AP. Drosophila CK2 regulates eye morphogenesis via phosphorylation of E(spl)M8. Mech Dev. 2004;121:273–86. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauffmann RC, Li S, Gallagher PA, Zhang J, Carthew RW. Ras1 signaling and transcriptional competence in the R7 cell of Drosophila. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2167–78. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.17.2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramatschek B, Campos-Ortega JA. Neuroectodermal transcription of the Drosophila neurogenic genes E(spl) and HLH-m5 is regulated by proneural genes. Development. 1994;120:815–26. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.4.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhnlein RP, Frommer G, Friedrich M, Gonzalez-Gaitan M, Weber A, Wagner-Bernholz JF, Gehring WJ, Jackle H, Schuh R. Spalt encodes an evolutionarily conserved zinc finger protein of novel structure which provides homeotic gene function in the head and tail region of the Drosophila embryo. Embo J. 1994;13:168–79. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06246.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann R, Jimenez F, Dietrich U, Campos-Ortega JA. On the phenotype and development of mutants of early neurogenesis in Drosophila melanogaster. Roux Arch dev Biol. 1983;192:62–74. doi: 10.1007/BF00848482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Baker NE. The roles of cis-inactivation by Notch ligands and of neuralized during eye and bristle patterning in Drosophila. BioMed Central Developmental Biology. 2004;4:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-4-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massari ME, Murre C. Helix-loop-helix proteins: regulators of transcription in eucaryotic organisms. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:429–40. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.2.429-440.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mlodzik M, Hiromi Y, Weber U, Goodman CS, Rubin GM. The Drosophila seven-up gene, a member of the steroid receptor gene superfamily, controls photoreceptor cell fates. Cell. 1990;60:211–24. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90737-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morata G, Ripoll P. Minutes: mutants of Drosophila autonomously affecting cell division rate. Developmental Biology. 1975;42:211–221. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(75)90330-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morel V, Schweisguth F. Repression by suppressor of hairless and activation by Notch are required to define a single row of single-minded expressing cells in the Drosophila embryo. Genes Dev. 2000;14:377–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagaraj R, Cannon J, Banerjee U. Cell fate specification in the Drosophila eye. In: Moses K, editor. Drosophila Eye Development. Vol. 37. Springer; 2002. pp. 73–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neufeld TP, de la Cruz AF, Johnston LA, Edgar BA. Coordination of growth and cell division in the Drosophila wing. Cell. 1998;93:1183–93. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81462-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newsome TP, Asling B, Dickson BJ. Analysis of Drosophila photoreceptor axon guidance in eye-specific mosaics. Development. 2000;127:851–60. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.4.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolo R, Abbott LA, Bellen HJ. Senseless, a Zn finger transcription factor, is necessary and sufficient for sensory organ development in Drosophila. Cell. 2000;102:349–62. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oellers N, Dehio M, Knust E. bHLH proteins encoded by the Enhancer of split complex of Drosophila negatively interfere with transcriptional activation mediated by proneural genes. Mol Gen Genet. 1994;244:465–473. doi: 10.1007/BF00583897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pignoni F, Zipursky SL. Induction of Drosophila eye development by decapentaplegic. Development. 1997;124:271–8. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.2.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottgen G, Wagner T, Hinz U. A genetic screen for elements of the network that regulates neurogenesis in Drosophila. Mol Gen Genet. 1998;257:442–51. doi: 10.1007/s004380050668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruzinova MB, Benezra R. Id proteins in development, cell cycle and cancer. Trends in Cell Biology. 2003;13:410–418. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(03)00147-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson A, Struhl G. Delta/Notch and Boss/Sevenless signals act combinatorially to specify the Drosophila R7 photoreceptor. Mol Cell. 2001;7:487–95. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00196-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Doren M, Ellis HM, Posakony JW. The Drosophila extramacrochaetae protein antagonizes sequence-specific DNA binding by daughterless/achaete-scute protein complexes. Development. 1991;113:245–55. doi: 10.1242/dev.113.1.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt FM, Estrach S, Amber CA. Epidermal Notch signalling: differentiation, cancer, and adhesion. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 2008;20:171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu T, Rubin GM. Analysis of genetic mosaics in developing and adult Drosophila tissues. Development. 1993;117:1223–37. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.4.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.