Abstract

Tumor angiogenesis is the result of an imbalance between positive and negative angiogenic factors released by tumor and host cells into the microenvironment of the neoplastic tissue. The stroma constitutes a large part of most solid tumors, and cancer-stromal cell interactions contribute functionally to tumor growth and metastasis. Activated fibroblasts and macrophages in tumor stroma play important roles in angiogenesis and tumor progression. In gastric cancer, tumor cells and stromal cells produce various angiogenic factors, including vascular endothelial growth factor, interleukin-8, platelet-derived endothelial cell growth factor, and angiopoietin. In addition, Helicobacter pylori infection increases tumor cell expression of metastasis-related genes including those encoding several angiogenic factors. We review the current understanding of molecular mechanisms involved in angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis of human gastric cancer.

1. Introduction

Gastric cancer is the world's second leading cause of cancer death [1]. In Asian countries such as Korea and China, gastric cancer is the leading cause of cancer death. Conventional therapies for advanced-stage gastric cancer include surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy, but the prognosis for advanced-stage disease remains poor. Novel therapeutic strategies are needed, but their development depends on understanding cancer biology, especially changes that occur on the molecular level. A large number of genetic and epigenetic alterations in oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes as well as genetic instability determine the multistep process of gastric carcinogenesis [2]. In addition, the molecular events that characterize gastric cancer differ, depending on the histologic type, whether intestinal- or diffuse-type gastric cancer [2].

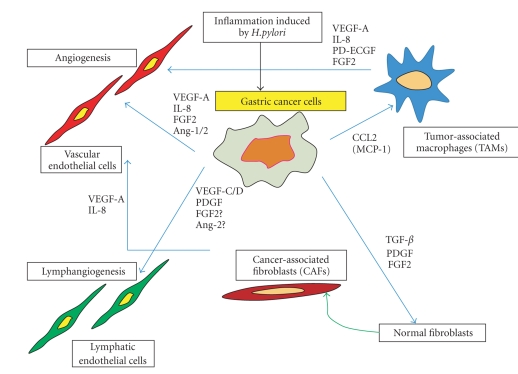

Tumor tissue, including gastric cancer, consists of both tumor cells and stromal cells. Tumor growth and metastasis are determined not only by tumor cells themselves but also by stromal cells. Recent studies have shown that interactions between tumor cells and activated stromal cells create a unique microenvironment that is crucial for tumor growth and metastasis (Figure 1) [3, 4]. The organ-specific microenvironment can influence the growth, vascularization, invasion, and metastasis of human neoplasms [5].

Figure 1.

Interaction between gastric cancer cells and stromal cells influences angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis through various angiogenic factors and cytokines.

Angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis are both essential for tumor growth and metastasis. Increased vascularity enhances the growth of primary neoplasms by supplying nutrients and oxygen, and it provides an avenue for hematogenous metastasis [6, 7]. Weidner et al. [8] first reported a direct correlation between the incidence of metastasis and the number and density of blood vessels in invasive breast cancers. Similar studies have confirmed this correlation in gastrointestinal cancers [9–12]. Induction of angiogenesis is mediated by a variety of molecules released by tumor cells as well as host stromal cells [6, 7]. Clinical prognosis depends on whether lymph node metastasis has occurred. The growth of lymphatic vessels (lymphangiogenesis) in the tumor periphery correlates with lymphatic metastasis in cases of gastric cancer [13, 14]. Lymphangiogenesis is regulated by members of the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) family and their receptors. Herein, we discuss the role of angiogenic and lymphangiogenic factors in the growth and metastasis of human gastric cancer.

2. Tumor Angiogenesis in Gastric Cancer

2.1. VEGF-A

Gastric cancer cells produce various angiogenic factors. Of these, VEGF (now termed VEGF-A) is considered one of the strongest promoters of angiogenesis of gastrointestinal tumors [15]. VEGF-A is released by cancer cells. Fibroblasts and inflammatory cells in tumor stroma are also sources of host-derived VEGF-A [16]. VEGF-A, also known as vascular permeability factor, is a secreted protein that may, in addition, play a pivotal role in hyperpermeability of the vessels [17]. Several groups of investigators have reported a correlation between VEGF-A expression and microvessel density (MVD) of human gastric cancer [11, 18, 19]. VEGF-A-positive tumors have been shown to have a poorer prognosis than that of VEGF-A-negative tumors [10, 12, 20].

The prognosis of gastric cancer depends on both histologic type and disease stage [21]. Intestinal-type gastric cancer tends to metastasize to the liver in a hematogenous manner. In contrast, diffuse-type gastric cancer is more invasive; dissemination is predominantly peritoneal. Factors responsible for liver metastasis and peritoneal dissemination have not yet been identified, however, we have found that the angiogenic phenotype differs between intestinal-type and diffuse-type gastric cancers [11, 19]. In comparison to diffuse-type gastric cancer, the intestinal-type is more dependent on angiogenesis. Intestinal-, but not diffuse-type, tumors have been shown to express high levels of VEGF-A, and the level of VEGF-A expression correlates significantly with vessel count [11, 19]. In contrast, fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-2 expression is higher in diffuse-type tumors, especially scirrhous-type tumors [22]. These findings suggest that VEGF-A promotes angiogenesis and progression of human gastric cancers, especially those of the intestinal-type.

Peripheral blood VEGF-A levels, that is, serum and/or plasma concentrations of VEGF-A, have been examined in patients with malignant disease. Ohta et al. [23] examined VEGF-A levels in peripheral blood and the tumor drainage vein and then evaluated these in relation to clinicopathologic features of gastric cancer. They found that the peripheral blood plasma VEGF-A level is increased in patients with venous invasion and that the increase correlates with lymph node metastasis. The level of VEGF-A in plasma from peripheral veins is a sensitive marker for the progression of gastric cancer.

2.2. Interleukin (IL)-8

IL-8 is a multifunctional cytokine that can stimulate division of endothelial cells. IL-8 can induce migration of some tumor cells [24] and has been implicated in the induction of angiogenesis in such diverse diseases as psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis and in some malignant diseases. IL-8 is a known angiogenic factor present in human lung cancer [25, 26] and is also produced by melanomas [27] and bladder [28] and prostate [29] cancers. We examined expression of IL-8 in human gastric cancer and found that most tumor tissues express IL-8 at levels higher than those in the corresponding normal mucosa [29, 30]. The IL-8 mRNA level in neoplasms correlates strongly with vascularization, suggesting that IL-8 produced by tumor cells regulates neovascularization. To provide evidence for a causal role of IL-8 in angiogenesis and tumorigenicity of human gastric cancer, we introduced the IL-8 gene into several human gastric cancer cell lines. Gastric cancer cells transfected with the IL-8 gene and injected orthotopically into the gastric wall of nude mice produce fast-growing, highly vascular neoplasms [31].

Gastric cancer cells express not only IL-8 but also IL-8 receptor A (CXCR1) and IL-8 receptor B (CXCR2) [32]. In vitro treatment of human gastric cancer cells (MKN-1 cells) with exogenous IL-8 enhances the expression of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9, VEGF-A, and IL-8 mRNAs. In contrast, such treatment decreases expression of E-cadherin mRNA. IL-8 treatment increases the invasive capacity of gastric cancer cells, and IL-8 expression is associated with MMP-9 activity. Collectively, these findings indicate that human gastric cancer cells express receptors for IL-8 and that IL-8 may have autocrine/paracrine roles in the progressive growth of human gastric cancer.

The prognosis for patients with gastric cancer expressing high levels of IL-8 and VEGF-A is significantly poorer than that for patients whose tumors express low levels [20]. A high level of IL-8 in the drainage vein of gastric cancer is associated significantly with a relatively short disease-free survival period [33].

2.3. Platelet-Derived Endothelial Cell Growth Factor (PD-ECGF)

PD-ECGF, an endothelial cell mitogen that was initially purified to homogeneity from human platelets, has chemotactic activity for endothelial cells in vitro and is angiogenic in vivo [34]. PD-ECGF was shown to be identical to thymidine phosphorylase, an enzyme involved in pyrimidine nucleoside metabolism [35]. PD-ECGF expression is elevated in several types of solid tumor including colon cancer [36, 37]. We reported that PD-ECGF is associated with angiogenesis of human colon cancer [38]. PD-ECGF is expressed at high levels in vascular tumors that express low levels of VEGF-A [38]. In such colon cancers, the major source of PD-ECGF is the infiltrating cells. A positive association between PD-ECGF expression and MVD has also been reported for human gastric cancer [39–41]. In human gastric cancer, PD-ECGF is expressed more frequently in infiltrating cells than in tumor epithelium [39]. An association exists between PD-ECGF expression by infiltrating cells, VEGF-A expression by tumor epithelium, and vessel counts in intestinal-type gastric cancer but not in diffuse-type gastric cancer [39].

2.4. Angiopoietin

The angiopoietin family growth factors have been identified as ligands for Tie-2. Angiopoietin-1 activates Tie-2, leading to receptor autophosphorylation upon binding, and it simulates endothelial cell migration in vitro and contributes to blood vessel stabilization by recruitment of pericytes [42]. Angiopoietin-2 is a natural antagonist for Tie-2 receptor [43]. As such, it antagonizes angiopoietin-1-vessel maturation and regulates blood vessel growth, regression, or sprouting, depending on the presence of VEGF [43]. VEGF-A/VEGFR2 is mainly involved in the initiation of angiogenesis, whereas the angiopoietin/Tie2 system is related to remodeling and maturation of vessels [44]. Angiopoietin-1 and -2 are reported to be highly expressed in human gastric cancer [45, 46]. Inhibition of angiopoietin-1 by antisense expression vector was shown to reduce tumorigenesis and angiogenesis of gastric cancer xenografts in nude mice [47]. Production of angiopoietin-2 also contributes to tumor angiogenesis of gastric cancer in the presence of VEGF by induction of proteases in endothelial cells [48].

3. Tumor Lymphangiogenesis in Gastric Cancer

The VEGF family includes VEGF-A, -B, -C, -D, -E, and -F and placental growth factor (PlGF) [49]. VEGF-C and VEGF-D are ligands for VEGF receptor (VEGFR)-3 and VEGFR-2. VEGFR-3 is a tyrosine kinase receptor, that is, expressed predominantly in the endothelium of lymphatic vessels [50]. Skobe et al. [51] described VEGF-C as a lymphangiogenic factor that can selectively induce hyperplasia of the lymphatic vasculature. A significant correlation between lymph node metastasis and VEGF-C expression has been reported in gastric cancer [13, 14]. Onogawa et al. [52] examined expression of VEGF-C and VEGF-D by immunohistochemistry in 140 archival surgical specimens of submucosally invasive gastric cancer. VEGF-C immunoreactivity was associated with lymphatic invasion, lymph node metastasis, and increased MVD. There was no association between VEGF-D immunoreactivity and clinicopathologic features. These results suggest that VEGF-C is a dominant regulator of lymphangiogenesis in early-stage human gastric cancer.

VEGFRs are expressed by a wide variety of cancer cell lines. VEGF-A and VEGFR-1/2 are coexpressed in a number of cancers, including cancers of the breast [53], prostate [54], colon [55], and pancreas [56, 57], suggesting that VEGF-A directly influences tumor cell growth via an autocrine mechanism. VEGFR-3 has also been detected on several types of malignant cells, although the significance of such expression remains unclear. We recently examined the expression and function of VEGFR-3 in gastric cancer cells [58]. In vitro treatment of gastric cancer cell line KKLS, which expresses VEGFR-3, with the ligand of this receptor, VEGF-C, stimulated cell proliferation and increased expression of mRNAs encoding cyclin D1, PlGF, and autocrine motility factor [58]. Thus, VEGF-C may act in both an autocrine fashion and paracrine fashion to promote angiogenesis and further the growth of human gastric cancer.

Other growth factors are reported to be lymphangiogenic, such as FGF-2 [59] and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-BB [60]. The lymphangiogenic effect of FGF-2 appears to be indirect, that is, it occurs via VEGF-C or -D. We recently found that gastric cancer cells produce PDGF-BB and that dilated lymphatics in the tumor periphery express PDGF receptor-β (Kodama et al., unpublished data), suggesting that PDGF-BB is a regulator of lymphangiogenesis in gastric cancer. Angiopoietin-2 is crucial for establishing the lymphatic vasculature. VEGF-C/VEGFR-3 signaling is a key primary proliferation pathway for lymphatic vessels, whereas angiopoietin-2 is important in later remodeling stages [61]. The importance of FGF-2, PDGF-BB, and angiopoietin-2 for lymphatic metastasis of human gastric cancer is still unknown.

4. Tumor-Stromal Cell Interaction in Tumor Angiogenesis

Tumor stroma consists of activated fibroblasts (myofibroblasts), smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells, and inflammatory cells, including macrophages. Macrophages migrating to tumor stroma are called tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs). The role of TAMs in tumor progression is complicated. Although activated macrophages may have antitumor activity, tumor cells are reported to escape the antitumor activity of TAMs [62]. It has become clear that TAMs are active players in the process of tumor progression and invasion. Indeed, removal of macrophages by genetic mutation has been shown to reduce tumor progression and metastasis [63]. One important characteristic of macrophages is the potential for angiogenic activity. Activated macrophages produce various factors that induce angiogenesis in wound repair [64] and in chronic inflammatory diseases [65, 66]. Upon activation by cancer cells, TAMs can release diverse growth factors, proteolytic enzymes, and cytokines. In clinical studies, high numbers of TAMs have been shown to correlate with high vessel density and tumor progression [67–69]. We previously reported that TAM infiltration into tumor tissue correlates significantly with tumor vascularity in human esophageal and gastric cancers [67, 68]. Ishigami et al. [69] also found direct associations between the degree of TAM infiltration and depth of tumor invasion, nodal status, and clinical stage in cases of gastric cancer. Macrophage recruitment is mediated by a variety of chemoattractants, including monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1/CCL2) and macrophage inflammatory protein 1α (MIP-1α/CCL3). Of the CC chemokines, MCP-1 is one of the most potent [70]. We found that MCP-1 produced by tumor cells is associated significantly with macrophage infiltration and malignant behavior, such as angiogenesis, tumor invasion, and lymphatic infiltration [67, 68]. Transfection of the MCP-1 gene into gastric cancer cells was shown to cause strong infiltration of macrophages into tumors and enhanced tumorigenicity and metastatic potential in a mouse orthotopic implantation model [71]. Because activated macrophages produce VEGF-A, IL-8, FGF-2, and PD-ECGF, MCP-1 expressed by gastric cancer cells plays a role in angiogenesis via recruitment and activation of macrophages.

Activated fibroblasts in cancer stroma are prominent modifiers of tumor progression and are therefore called cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) [72, 73]. CAFs have gene expression profiles that are distinct from those of normal fibroblasts [74], and they acquire a modified phenotype, similar to that of fibroblasts associated with wound healing. Tumor tissue contains abundant growth factors, cytokines, and matrix-remodeling proteins; thus, tumors are likened to wounds that never heal [75]. Although the mechanisms that regulate activation of fibroblasts in tumors are not fully understood, PDGF, transforming growth factor-β, and FGF-2 are known to be partly involved [72, 73, 76]. We previously reported that CAFs and pericytes express PDGF receptor, and targeting the PDGF receptor on stromal cells inhibits growth and metastasis of human colon cancer [76, 77]. Therefore, CAFs might serve as novel therapeutic targets in cancer patients.

5. Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) Stimulates Angiogenesis of Gastric Cancer

A recent advance in understanding the pathogenesis of gastric cancer is recognition of the role of H. pylori in gastric carcinogenesis. H. pylori infection is thought to contribute significantly to the pathogenesis of atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, and peptic ulcer. Epidemiologic studies have indicated that infection with H. pylori is a risk factor for gastric cancer, and in 1994 the WHO/IARC classified this bacterium as a definite biologic carcinogen [78]. In addition, inoculation of the stomach of Mongolian gerbils with H. pylori was shown to be associated with the occurrence of chronic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, and adenocarcinoma [79, 80]. A recent study showed that H. pylori penetrates normal, metaplastic, and neoplastic epithelia to cause a strong immune-inflammatory response and promote gastric carcinogenesis [81]. H. pylori is a potent activator of nuclear factor-kB (NF-kB) in gastric epithelial cells. Activation of NF-kB by H. pylori infection induces a variety of cytokines, angiogenic factors, MMPs, and adhesion molecules [82, 83]. The relation between H. pylori infection and angiogenesis has been studied increasingly over the past few years. We reported previously that H. pylori-infected gastric cancer patients show greater tumor vascularity than that of gastric cancer patients after H. pylori eradication [84], suggesting that H. pylori infection influences angiogenesis of gastric cancer. Some studies suggested that the cagA-positive H. pylori strain plays an important role in tissue remodeling, angiogenesis, cancer invasion, and metastasis [85–87]. Crabtree et al. [85] reported that H. pylori infection induces IL-8 production by gastric epithelium. We found that coculture of gastric cancer cells with H. pylori induces expression of mRNAs encoding IL-8, VEGF-A, angiogenin, urokinase-type plasminogen activator, and MMP-9 by gastric cancer cells [86]. Wu et al. [87] also reported that H. pylori influences expression of VEGF-A and MMP-9 and promotes gastric cell invasion via COX-2- and NF-kB-mediated pathways. Expression of COX-2 was found to correlate significantly with VEGF expression and MVD in gastric cancer [88, 89].

6. Antiangiogenic Therapy Against Gastric Cancer

A novel category of anticancer drugs, “molecular-targeted drugs”, has become available. Angiogenesis is considered one of the most important molecular targets for anticancer therapy because it is essential for tumor growth and metastasis. VEGF is one of the most potent angiogenic factors and is expressed in almost all human solid tumors investigated, such as colorectal, esophageal, gastric, lung, breast, renal, and ovarian cancers [9, 12, 15, 90]. In these cancers, expression of VEGF correlates with advanced stage disease and poor prognosis. Therefore, inhibiting VEGF is a rational strategy for treating cancer [91]. Bevacizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that targets VEGF. Significant prolonged survival has been reported in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer treated with bevacizumab in combination with cytotoxic chemotherapy [92]. Similar improvement were observed in patients with breast and non-small cell lung cancers. A randomized trial evaluating the efficacy of this agent in patients with gastric cancer (the AVAGAST study) is now being conducted internationally; Japan and Korea are included [93]. Several other strategies targeting the VEGF signaling pathway have been developed, including use of soluble receptors binding directly to VEGF ligand, anti-VEGFR antibodies, and VEGR tyrosine kinase inhibitors. These next-generation targeted agents are being evaluated in early clinical studies [91, 93].

7. Future Perspectives

Tumor cells are genetically unstable and biologically heterogeneous, and these are the principal causes of the failure of systemic chemotherapies. It has been believed that endothelial cells and CAFs in tumor stroma are genetically stable and that these cells will not become drug resistant in response to antivascular therapy. However, recent studies showed that endothelial cells in certain tumor vessels are aneuploid and that they express neoplastic markers [94]. Recently, investigators have come to appreciate the significance of other cell types, such as pericytes and vascular smooth muscle cells, that make up vascular structures and are essential for the function and survival of endothelial cells. The structure and function of vessels differ in different tissues and in tumors at different sites. Inhibition of activated stromal cell components including TAMs and CAFs may effectively alter the tumor microenvironment involved in tumor angiogenesis and progression. Understanding the cellular and molecular mechanisms that regulate vascularization of tumors may facilitate development of effective antivascular therapies.

References

- 1.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. Ca: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2005;55(2):74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith MG, Hold GL, Tahara E, El-Omar EM. Cellular and molecular aspects of gastric cancer. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2006;12(18):2979–2990. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i19.2979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454(7203):436–444. doi: 10.1038/nature07205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whiteside TL. The tumor microenvironment and its role in promoting tumor growth. Oncogene. 2008;27(45):5904–5912. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fidler IJ. Critical factors in the biology of human cancer metastasis: twenty-eighth G.H.A. Clowes memorial award lecture. Cancer Research. 1990;50(19):6130–6138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Folkman J. How is blood vessel growth regulated in normal and neoplastic tissue? G.H.A. Clowes memorial award lecture. Cancer Research. 1986;46(2):467–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Folkman J. What is the evidence that tumors are angiogenesis dependent? Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1990;82(1):4–6. doi: 10.1093/jnci/82.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weidner N, Semple JP, Welch WR, Folkman J. Tumor angiogenesis and metastasis—correlation in invasive breast carcinoma. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1991;324(1):1–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199101033240101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takahashi Y, Kitadai Y, Bucana CD, Cleary KR, Ellis LM. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptor, KDR, correlates with vascularity, metastasis, and proliferation of human colon cancer. Cancer Research. 1995;55(18):3964–3968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanigawa N, Amaya H, Matsumura M, et al. Extent of tumor vascularization correlates with prognosis and hematogenous metastasis in gastric carcinomas. Cancer Research. 1996;56(11):2671–2676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takahashi Y, Cleary KR, Mai M, Kitadai Y, Bucana CD, Ellis LM. Significance of vessel count and vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptor (KDR) in intestinal-type gastric cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 1996;2(10):1679–1684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maeda K, Chung Y-S, Ogawa Y, et al. Prognostic value of vascular endothelial growth factor expression in gastric carcinoma. Cancer. 1996;77(5):858–863. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19960301)77:5<858::aid-cncr8>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amioka T, Kitadai Y, Tanaka S, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor-C expression predicts lymph node metastasis of human gastric carcinomas invading the submucosa. European Journal of Cancer. 2002;38(10):1413–1419. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(02)00106-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yonemura Y, Endo Y, Fujita H, et al. Role of vascular endothelial growth factor C expression in the development of lymph node metastasis in gastric cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 1999;5(7):1823–1829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yancopoulos GD, Davis S, Gale NW, Rudge JS, Wiegand SJ, Holash J. Vascular-specific growth factors and blood vessel formation. Nature. 2000;407(6801):242–248. doi: 10.1038/35025215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fukumura D, Xavier R, Sugiura T, et al. Tumor induction of VEGF promoter activity in stromal cells. Cell. 1998;94(6):715–725. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81731-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Senger DR, Galli SJ, Dvorak AM, Perruzzi CA, Harvey VS, Dvorak HF. Tumor cells secrete a vascular permeability factor that promotes accumulation of ascites fluid. Science. 1983;219(4587):983–985. doi: 10.1126/science.6823562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown LF, Berse B, Jackman RW, et al. Expression of vascular permeability factor (vascular endothelial growth factor) and its receptors in adenocarcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract. Cancer Research. 1993;53(18):4727–4735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamamoto S, Yasui W, Kitadai Y, et al. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in human gastric carcinomas. Pathology International. 1998;48(7):499–506. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1998.tb03940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kido S, Kitadai Y, Hattori N, et al. Interleukin 8 and vascular endothelial growth factor—prognostic factors in human gastric carcinomas? European Journal of Cancer. 2001;37(12):1482–1487. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00147-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duarte I, Llanos O. Patterns of metastases in intestinal and diffuse types of carcinoma of the stomach. Human Pathology. 1981;12(3):237–242. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(81)80124-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tanimoto H, Yoshida K, Yokozaki H, et al. Expression of basic fibroblast growth factor in human gastric carcinomas. Virchows Archiv B. 1991;61(4):263–267. doi: 10.1007/BF02890427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ohta M, Konno H, Tanaka T, et al. The significance of circulating vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) protein in gastric cancer. Cancer Letters. 2003;192(2):215–225. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(02)00681-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang JM, Taraboletti G, Matsushima K, Van Damme J, Mantovani A. Induction of haptotactic migration of melanoma cells by neutrophil activating protein/interleukin-8. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1990;169(1):165–170. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)91449-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strieter RM, Polverini PJ, Arenberg DA, et al. Role of C-X-C chemokines as regulators of angiogenesis in lung cancer. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 1995;57(5):752–762. doi: 10.1002/jlb.57.5.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith DR, Polverini PJ, Kunkel SL, et al. Inhibition of interleukin 8 attenuates angiogenesis in bronchogenic carcinoma. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1994;179(5):1409–1415. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.5.1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singh RK, Gutman M, Radinsky R, Bucana CD, Fidler IJ. Expression of interleukin 8 correlates with the metastatic potential of human melanoma cells in nude mice. Cancer Research. 1994;54(12):3242–3247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tachibana M, Miyakawa A, Nakashima J, et al. Constitutive production of multiple cytokines and a human chorionic gonadotrophin β-subunit by a human bladder cancer cell line (KU-19-19): possible demonstration of totipotential differentiation. British Journal of Cancer. 1997;76(2):163–174. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greene GF, Kitadai Y, Pettaway CA, von Eschenbach AC, Bucana CD, Fidler IJ. Correlation of metastasis-related gene expression with metastatic potential in human prostate carcinoma cells implanted in nude mice using an in situ messenger RNA hybridization technique. American Journal of Pathology. 1997;150(5):1571–1582. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kitadai Y, Haruma K, Sumii K, et al. Expression of interleukin-8 correlates with vascularity in human gastric carcinomas. American Journal of Pathology. 1998;152(1):93–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kitadai Y, Takahashi Y, Haruma K, et al. Transfection of interleukin-8 increases angiogenesis and tumorigenesis of human gastric carcinoma cells in nude mice. British Journal of Cancer. 1999;81(4):647–653. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kitadai Y, Haruma K, Mukaida N, et al. Regulation of disease-progression genes in human gastric carcinoma cells by interleukin 8. Clinical Cancer Research. 2000;6(7):2735–2740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Konno H, Ohta M, Baba M, Suzuki S, Nakamura S. The role of circulating IL-8 and VEGF protein in the progression of gastric cancer. Cancer Science. 2003;94(8):735–740. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2003.tb01511.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ishikawa F, Miyazono K, Hellman U, et al. Identification of angiogenic activity and the cloning and expression of platelet-derived endothelial cell growth factor. Nature. 1989;338(6216):557–562. doi: 10.1038/338557a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moghaddam A, Bicknell R. Expression of platelet-derived endothelial cell growth factor in Escherichia coli and confirmation of its thymidine phosphorylase activity. Biochemistry. 1992;31(48):12141–12146. doi: 10.1021/bi00163a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reynolds K, Farzaneh F, Collins WP, et al. Association of ovarian malignancy with expression of platelet-derived endothelial cell growth factor. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1994;86(16):1234–1238. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.16.1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Toi M, Inada K, Hoshina S, Suzuki H, Kondo S, Tominaga T. Vascular endothelial growth factor and platelet-derived endothelial cell growth factor are frequently coexpressed in highly vascularized human. Clinical Cancer Research. 1995;1(9):961–964. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takahashi Y, Bucana CD, Liu W, et al. Platelet-derived endothelial cell growth factor in human colon cancer angiogenesis: role of infiltrating cells. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1996;88(16):1146–1151. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.16.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takahashi Y, Bucana CD, Akagi Y, et al. Significance of platelet-derived endothelial cell growth factor in the angiogenesis of human gastric cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 1998;4(2):429–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maeda K, Chung Y-S, Ogawa Y, et al. Thymidine phosphorylase/platelet-derived endothelial cell growth factor expression associated with hepatic metastasis in gastric carcinoma. British Journal of Cancer. 1996;73(8):884–888. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saito H, Tsujitani S, Oka S, et al. The expression of thymidine phosphorylase correlates with angiogenesis and the efficacy of chemotherapy using fluorouracil derivatives in advanced gastric carcinoma. British Journal of Cancer. 1999;81(3):484–489. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Davis S, Aldrich TH, Jones PF, et al. Isolation of angiopoietin-1, a ligand for the TIE2 receptor, by secretion-trap expression cloning. Cell. 1996;87(7):1161–1169. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81812-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maisonpierre PC, Suri C, Jones PF, et al. Angiopoietin-2, a natural antagonist for Tie2 that disrupts in vivo angiogenesis. Science. 1997;277(5322):55–60. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5322.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sato TN, Tozawa Y, Deutsch U, et al. Distinct roles of the receptor tyrosine kinases Tie-1 and Tie-2 in blood vessel formation. Nature. 1995;376(6535):70–74. doi: 10.1038/376070a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang J, Wu K, Zhang D, et al. Expressions and clinical significances of angiopoietin-1, -2 and Tie2 in human gastric cancer. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2005;337(1):386–393. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nakayama T, Yoshizaki A, Kawahara N, et al. Expression of Tie-1 and 2 receptors, and angiopoietin-1, 2 and 4 in gastric carcinoma; immunohistochemical analyses and correlation with clinicopathological factors. Histopathology. 2004;44(3):232–239. doi: 10.1111/j.0309-0167.2004.01817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang J, Wu K-C, Zhang D-X, Fan D-M. Antisense angiopoietin-1 inhibits tumorigenesis and angiogenesis of gastric cancer. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2006;12(15):2450–2454. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i15.2450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Etoh T, Inoue H, Tanaka S, Barnard GF, Kitano S, Mori M. Angiopoietin-2 is related to tumor angiogenesis in gastric carcinoma: possible in vivo regulation via induction of proteases. Cancer Research. 2001;61(5):2145–2153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Otrock ZK, Makarem JA, Shamseddine AI. Vascular endothelial growth factor family of ligands and receptors: review. Blood Cells, Molecules, and Diseases. 2007;38(3):258–268. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kaipainen A, Korhonen J, Mustonen T, et al. Expression of the fms-like tyrosine kinase 4 gene becomes restricted to lymphatic endothelium during development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1995;92(8):3566–3570. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Skobe M, Hawighorst T, Jackson DG, et al. Induction of tumor lymphangiogenesis by VEGF-C promotes breast cancer metastasis. Nature Medicine. 2001;7(2):192–198. doi: 10.1038/84643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Onogawa S, Kitadai Y, Amioka T, et al. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-C and VEGF-D in early gastric carcinoma: correlation with clinicopathological parameters. Cancer Letters. 2005;226(1):85–90. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.de Jong JS, van Diest PJ, van der Valk P, Baak JPA. Expression of growth factors, growth inhibiting factors, and their receptors in invasive breast cancer. I: an inventory in search of autocrine and paracrine loops. Journal of Pathology. 1998;184(1):44–52. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199801)184:1<44::AID-PATH984>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Harper ME, Glynne-Jones E, Goddard L, Thurston VJ, Griffiths K. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression in prostatic tumours and its relationship to neuroendocrine cells. British Journal of Cancer. 1996;74(6):910–916. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kuwai T, Nakamura T, Kim S-J, et al. Intratumoral heterogeneity for expression of tyrosine kinase growth factor receptors in human colon cancer surgical specimens and orthotopic tumors. American Journal of Pathology. 2008;172(2):358–366. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Itakura J, Ishiwata T, Shen B, Kornmann M, Korc M. Concomitant over-expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptors in pancreatic cancer. International Journal of Cancer. 2000;85(1):27–34. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(20000101)85:1<27::aid-ijc5>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.von Marschall Z, Cramer T, Höcker M. De novo expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in human pancreatic cancer: evidence for an autocrine mitogenic loop. Gastroenterology. 2000;119(5):1358–1372. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.19578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kodama M, Kitadai Y, Tanaka M, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor C stimulates progression of human gastric cancer via both autocrine and paracrine mechanisms. Clinical Cancer Research. 2008;14(22):7205–7214. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kubo H, Cao R, Bräkenhielm E, Mäkinen T, Cao Y, Alitalo K. Blockade of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-3 signaling inhibits fibroblast growth factor-2-induced lymphangiogenesis in mouse cornea. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99(13):8868–8873. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062040199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cao R, Björndahl MA, Religa P, et al. PDGF-BB induces intratumoral lymphangiogenesis and promotes lymphatic metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2004;6(4):333–345. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gale NW, Thurston G, Hackett SF, et al. Angiopoietin-2 is required for postnatal angiogenesis and lymphatic patterning, and only the latter role is rescued by angiopoietin-1. Developmental Cell. 2002;3(3):411–423. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00217-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lewis CE, Pollard JW. Distinct role of macrophages in different tumor microenvironments. Cancer Research. 2006;66(2):605–612. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Condeelis J, Pollard JW. Macrophages: obligate partners for tumor cell migration, invasion, and metastasis. Cell. 2006;124(2):263–266. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Leibovich SJ, Wiseman DM. Macrophages, wound repair and angiogenesis. Progress in Clinical and Biological Research. 1988;266:131–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Koch AE, Polverini PJ, Leibovich SJ. Stimulation of neovascularization by human rheumatoid synovial tissue macrophages. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1986;29(4):471–479. doi: 10.1002/art.1780290403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wolf JE., Jr. Angiogenesis in normal and psoriatic skin. Laboratory Investigation. 1989;61(2):139–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ohta M, Kitadai Y, Tanaka S, et al. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression correlates with macrophage infiltration and tumor vascularity in human esophageal squamous cell carcinomas. International Journal of Cancer. 2002;102(3):220–224. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ohta M, Kitadai Y, Tanaka S, et al. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression correlates with macrophage infiltration and tumor vascularity in human gastric carcinomas. International Journal of Oncology. 2003;22(4):773–778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ishigami S, Natsugoe S, Tokuda K, et al. Tumor-associated macrophage (TAM) infiltration in gastric cancer. Anticancer Research. 2003;23(5):4079–4083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fuentes ME, Durham SK, Swerdel MR, et al. Controlled recruitment of monocytes and macrophages to specific organs through transgenic expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1. Journal of Immunology. 1995;155(12):5769–5776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kuroda T, Kitadai Y, Tanaka S, et al. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 transfection induces angiogenesis and tumorigenesis of gastric carcinoma in nude mice via macrophage recruitment. Clinical Cancer Research. 2005;11(21):7629–7636. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Orimo A, Gupta PB, Sgroi DC, et al. Stromal fibroblasts present in invasive human breast carcinomas promote tumor growth and angiogenesis through elevated SDF-1/CXCL12 secretion. Cell. 2005;121(3):335–348. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.De Wever O, Mareel M. Role of tissue stroma in cancer cell invasion. Journal of Pathology. 2003;200(4):429–447. doi: 10.1002/path.1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Allinen M, Beroukhim R, Cai L, et al. Molecular characterization of the tumor microenvironment in breast cancer. Cancer Cell. 2004;6(1):17–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dvorak HF. Tumors: wounds that do not heal: similarities between tumor stroma generation and wound healing. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1986;315(26):1650–1659. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198612253152606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kitadai Y, Sasaki T, Kuwai T, et al. Expression of activated platelet-derived growth factor receptor in stromal cells of human colon carcinomas is associated with metastatic potential. International Journal of Cancer. 2006;119(11):2567–2574. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kitadai Y, Sasaki T, Kuwai T, Nakamura T, Bucana CD, Fidler IJ. Targeting the expression of platelet-derived growth factor receptor by reactive stroma inhibits growth and metastasis of human colon carcinoma. American Journal of Pathology. 2006;169(6):2054–2065. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kitadai Y, Sasaki T, Kuwai T, Nakamura T, Bucana CD, Fidler IJ. Schistosomes, liver flukes and Helicobacter pylori. IARC working group on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. Lyon, 7–14 June 1994. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. 1994;61:1–241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Watanabe T, Tada M, Nagi H, Sasaki S, Nakao M. Helicobacter pylori infection induces gastric cancer in Mongolian gerbils. Gastroenterology. 1998;115(3):642–648. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70143-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Honda S, Fujioka T, Tokieda M, Satoh R, Nishizono A, Nasu M. Development of Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric carcinoma in mongolian gerbils. Cancer Research. 1998;58(19):4255–4259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Necchi V, Candusso ME, Tava F, et al. Intracellular, intercellular, and stromal invasion of gastric mucosa, preneoplastic lesions, and cancer by Helicobacter pylori . Gastroenterology. 2007;132(3):1009–1023. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sharma SA, Tummuru MKR, Blaser MJ, Kerr LD. Activation of IL-8 gene expression by Helicobacter pylori is regulated by transcription factor nuclear factor-κB in gastric epithelial cells. Journal of Immunology. 1998;160(5):2401–2407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hatz RA, Rieder G, Stolte M, et al. Pattern of adhesion molecule expression on vascular endothelium in Helicobacter pylori-associated antral gastritis. Gastroenterology. 1997;112(6):1908–1919. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.pm9178683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sasaki A, Kitadai Y, Ito M, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection influences tumor growth of human gastric carcinomas. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2003;38(2):153–158. doi: 10.1080/00365520310000636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Crabtree JE, Wyatt JI, Trejdosiewicz LK, et al. Interleukin-8 expression in Helicobacter pylori infected, normal, and neoplastic gastroduodenal mucosa. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 1994;47(1):61–66. doi: 10.1136/jcp.47.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kitadai Y, Sasaki A, Ito M, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection influences expression of genes related to angiogenesis and invasion in human gastric carcinoma cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2003;311(4):809–814. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.10.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wu C-Y, Wang C-J, Tseng C-C, et al. Helicobacter pylori promote gastric cancer cells invasion through a NF-κB and COX-2-mediated pathway. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2005;11(21):3197–3203. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i21.3197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Joo Y-E, Rew J-S, Seo Y-H, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 overexpression correlates with vascular endothelial growth factor expression and tumor angiogenesis in gastric cancer. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 2003;37(1):28–33. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200307000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Uefuji K, Ichikura T, Mochizuki H. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression is related to prostaglandin biosynthesis and angiogenesis in human gastric cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 2000;6(1):135–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kitadai Y, Haruma K, Tokutomi T, et al. Significance of vessel count and vascular endothelial growth factor in human esophageal carcinomas. Clinical Cancer Research. 1998;4(9):2195–2200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Iwasaki J, Nihira S-I. Anti-angiogenic therapy against gastrointestinal tract cancers. Japanese Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009;39(9):543–551. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyp062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W, et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;350(23):2335–2342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ohtsu A. Chemotherapy for metastatic gastric cancer: past, present, and future. Journal of Gastroenterology. 2008;43(4):256–264. doi: 10.1007/s00535-008-2177-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Streubel B, Chott A, Huber D, et al. Lymphoma-specific genetic aberrations in microvascular endothelial cells in B-cell lymphomas. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;351(3):250–259. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]