Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to develop and evaluate a pictorial, web-based version of the NCI Diet History Questionnaire (Web-PDHQ).

Design

The Web-PDHQ and paper version of the Diet History Questionnaire (Paper-DHQ) were administered four weeks apart with 218 participants randomized to order. Dietary data from the Web-PDHQ and Paper-DHQ were validated using a randomly selected 4-day food recordfood record recording period (including a weekend day) and two randomly selected 24-hour. dietary recalls during the four weeks intervening between these two diet history administrations.

Setting

Research office in Reston, VA, USA.

Participants

Computer literate men and women recruited from newspaper advertisements.

Results

Mean correlation of energy and the 25 examined nutrients between the Web-PDHQ and Paper-DHQ was 0.71 and 0.51, unadjusted and energy-adjusted by the residual method, respectively. Moderate mean correlations (unadjusted 0.41 and 0.38; energy-adjusted 0.41 and 0.34) were obtained between both the Web-PDHQ and Paper-DHQ with the 4-day food recordfood record on energy and nutrients, but the correlations between the Web-PDHQ and Paper-DHQ with the 24 hr. recalls, were modest (unadjusted 0.31 and 0.29; energy-adjusted 0.37 and 0.26). A subset of participants (n=48) completing the Web-PDHQ at the initial visit performed a retest on the same questionnaire one week later to determine test-retest reliability, and unadjusted mean correlation was 0.82.

Conclusions

These data indicate that the Web-PDHQ has comparable reliability and validity as the Paper-DHQ, but did not improve the relationship of the DHQ to other food intake measures (e.g. food recordsfood records, 24 hr. recall).

Introduction

Food Frequency Questionnaires are often used to measure diet in observational studies because they provide a standardized and cost-efficient approach for collecting data on usual food intake. Many food frequency questionnaires have been developed and used in a variety of ways, ranging from capturing usual intake among large, population-based samples (1) to tailoring the questionnaire to measure intake of a particular nutrient, food, or food group in small, specialized groups. Validation studies have found weak correlations between food frequency questionnaires and other dietary assessment measures, including food records (2), 24-hour. recalls (3), and biomarkers (4). The research community is actively debating whether future nutrition research should incorporate food frequency questionnaires (5–8). Given that few suitable alternatives currently exist for large studies, it is worthwhile to consider potential improvements in the analysis and administration of food frequency questionnaires.

24-hourAdministration of food frequency questionnaires is typically paper-based rather than web-based. Web-based administration of the questionnaire may impact the data quality in several ways. Participants with internet access can complete a food frequency questionnaire at any time from any location with centralized monitoring of participant completion. Missing data can be minimized by adding alerts to users and automating skip or branching logic. Data processing can be facilitated by eliminating scanning of paper forms. Web-based administration can also offer aids such as illustrations of food portions to improve portion size estimation and recognition of the food. The use of food pictures may also reduce the reading level needed to complete a food frequency questionnaire. The use of computer-based questionnaires, however, may exclude segments of the population without access to or ability to use computers.

Web-based versions of two of the more widely-used questionnaires have been developed and are available (9,10), but no published data estimate how the aforementioned factors associated with web-based administration influence relative validity and reliability of dietary assessment. Though other paper-based food frequency questionnaires include pictures to depict portion sizes, the impact of pictures on food frequency questionnaire has not been previously reported.

A web-based pictorial diet history questionnaire (Web-PDHQ) was developed by adding pictures to the National Cancer Institute's Diet History Questionnaire (DHQ) (1) to represent portion sizes. The hypothesis was that participants would be able to provide more accurate and complete accounts of usual intake using the Web-PDHQ since portion size estimates should be improved using a pictorial form of a diet history. A randomized, controlled trial (n=218) was conducted to determine whether the Web-PDHQ provided an improved estimation of dietary intake compared to a non-pictorial, paper-based version (Paper-DHQ) of the same questionnaire.

Methods

Development of the Web-PDHQ

A registered dietitian obtained, prepared, and measured foods described in the National Cancer Institute's Diet History Questionnaire using standard measuring cups and a portion control scale. Foods were placed in the center of a plate with common utensils to provide perspective. Each food portion was professionally photographed using a high quality digital camera from an angle and distance comparable to the view of these foods while sitting at a table. The resulting photographs were reviewed and prepared in jpeg format for use on the web site. Photographs were linked with the 124 items from the National Cancer Institute's Diet History Questionnaire asking users to indicate the frequency and amount of consumption of each particular food over the past year. In accordance with the Diet History Questionnaire, users were first asked to identify the frequency of consumption for an individual food. Once it was identified that the food was consumed, users were presented with a display of the food in the portion sizes specified on the DHQ (typically 2 portion sizes) and asked to select the amount typically eaten at one sitting.

Study Participants

Participants were recruited from advertisements placed in the Washington Post. Adults aged 18 years or older who were computer literate, defined as using the internet at least 3 times per week, were eligible to participate in the study. The study was approved by the PICS Institutional Review Board and each participant provided written, informed consent.

Study Design

The study was conducted between April and July 2006 at the PICS office in Reston, VA. Two hundred and eighteen participants were assigned to complete two versions of the Diet History Questionnaire spaced 4-weeks apart: the internet-based, pictorial version (Web-PDHQ) and the traditional paper and pencil version (Paper-DHQ). The order of the administration was randomly assigned using the random numbers generator located at www.random.org.

Study Procedures

Participants were screened via phone and scheduled for an initial appointment. At the first visit, participants reviewed and signed informed consent, completed a demographic questionnaire, and were weighed using a Tanita digital scale (Model WB-110A).

Based on the randomization assignment, the participant was asked to complete either the self-administered Web-PDHQ or the Paper-DHQ. During the subsequent four-week period, the dietary intake of participants was assessed using a 4-day food record and two 24-hour. dietary recalls. Timing of food records was assigned as 4 consecutive days to include one weekend day and was determined during the initial visit. The 24 hr. recalls were administered on two nonconsecutive days which were randomly assigned by the research assistant based upon a randomization table. The assigned research assistant attempted to contact the participant in the morning and afternoon, if necessary, on the assigned day to collect 24 hr. recall data. If they were not able to collect the information on that day, additional calls would be made for 2 consecutive days in an attempt to collect data for the 24 hrs prior. food recordfood recordEach participant was provided with a 24-hour recall kit containing measurement tools to facilitate portion size estimation. Procedures for administering 24-hour recalls were adapted for use without an automated system from the USDA multiple pass format (quick list, time, occasion, and place, forgotten foods list, food details, and review) (11,12). A registered dietitian trained research assistants to conduct telephone interviews. Data collection was completed on a standardized form using standardized language across all participants and participants were asked to refer to their food portion estimation handouts throughout the interview. Data collection began with the first thing the participant ate or drank when they awoke the morning before through 24-hours later.

Fifty participants who received the Web-PDHQ were randomly selected to assess test-retest reliability of the Web-PDHQ. One week after the initial visit, these participants were asked to repeat the Web-PDHQ. Test-retest participants who did not have access to a high speed internet connection were asked to return to the PICS office for an additional visit to complete this repeat administration.

At the conclusion of the four-week period, all participants returned to the research office and the other diet history questionnaire was administered. Food records were reviewed with participants to insure writing was legible and records were complete. Participants rated usability of both the Web-PDHQ and Paper-DHQ. Using 10-point Likert Scales, participants were asked to rate ease of use, ability to change answers, and ability to accurately estimate portion sizes. For the Web-PDHQ only, participants rated the usefulness of the pictures of each portion size.

Statistical analysis

Both the Paper-DHQ and Web-PDHQ were processed using the National Cancer Institute's Diet*Calc software which provides raw energy and nutrient intake estimates (13). The data were ported into both SPSS (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and STATA Version 8.2 (STATA, College Station, TX, USA) for analysis. Food intake obtained from the food recordsfood records and 24 hr. recalls were entered and analyzed using ESHA FoodProcessor SQL (ESHA, Version 9.5.0, Salem, OR). A registered dietitian coded all food records, and trained research assistants coded 24-hour recalls. No formal quality control measures were implemented to assess intra-individual variability in the coding of 24-hour recalls.

Descriptive statistics were computed to describe participant characteristics and nutrient intake measured by the four nutrient assessment methods. Due to non-normality, Box-Cox transformations were applied to energy and nutrient intakes.

To assess concurrent validity, nutrient values obtained from the Web-PDHQ were compared to the Paper-DHQ, food recordfood record, and the average of the two 24 hr. recalls using Pearson correlations. Reliability was measured using Pearson correlation coefficients between Web-DHQ 1 and 2 among the subset of 50 participants asked to complete the questionnaire twice. Data were not corrected for attenuation due to random error associated with within-person variability (errors between the comparison dietary assessment methods are correlated, thereby violating one of the assumptions underlying this approach). Correlations were adjusted for energy intake using the residual approach. Overall and sex-specific estimates were calculated, but data were combined by sex for presentation since stratified estimates were similar by gender. food recordsfood recordsfood recordfood record

Results

Study Participants

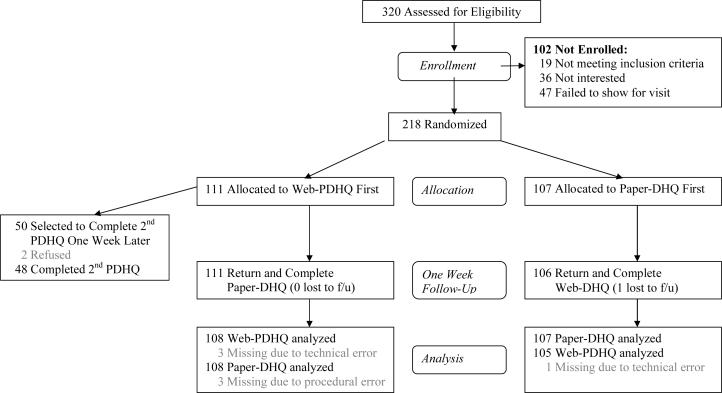

Of the 218 participants enrolled in the study, 217 completed the web-based PDHQ and 215 completed the paper-based DHQ (Figure 1). Four Web-PDHQ's were excluded from the analysis due to a technical problem resulting in data loss. Three Paper-DHQ's were missing due to procedural errors. All 217 participants who completed the study returned a completed food recordfood record. Three participants did not complete one of the two recalls, but all 218 participants completed at least one recall. Two of the fifty participants randomly assigned to repeat the Web-PDHQ one week later declined to complete the second administration.

Figure 1.

Study Participant Flow in the Web-based Pictorial DHQ trial.

The majority of the study participants were female, White, and all reported at least twelve years of education (Table 1). Consistent with the mean age and education level, 49% were employed with 34% retired, 11% homemakers, 3% unemployed, 2% disabled, and 1% students. Sixty-four percent were married or living with a partner.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants in the Web-PDHQ Validity Trial (n=218).

| Characteristic | Mean ± SD or Frequency n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 54.9 ± 14.4 |

| Female | 165 (75.6) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 27.2 ± 6.2 |

| Ethnicity | |

| White | 190 (87.2) |

| Black | 21 (9.6) |

| Asian | 5 (2.3) |

| American Indian/ Alaska Native | 2 (1.0) |

| Hispanic | 10 (4.6) |

| Education | |

| High School | 20 (9.2) |

| Some College | 40 (18.3) |

| College Degree | 54 (24.8) |

| Post-college | 104 (47.8) |

Mean height was 66 inches (SD = 4) and mean weight was 168 lbs. (SD =42) ranging from 101 to 353 lbs. Thirty-one percent (n=67) of the study sample was overweight (BMI 25–30) and 27% (n=59) were obese (BMI>30). Twenty-nine percent reported having received some form of prior instruction in food portion estimation.

Comparison between dietary assessment measures

Table 2 presents medians and inter-quartile ranges obtained from the Web-PDHQ, Paper-DHQ, 4-day food recordfood record and the average of the two 24-hour recalls for each of the food label nutrients. Median values for the Web-PDHQ were similar to the Paper-DHQ as well as the other two dietary assessment measures, but the Web-PDHQ produced slightly higher energy and nutrient values compared to the Paper-DHQ.

Table 2.

Summary of energy and nutrient median (IQR*) estimates by dietary assessment method.

| Energy or Nutrient | Paper-DHQ n=215 | Web-PDHQ n=213 | 24-hour. Recalls n=218 | Food recordFood record n=217 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy (kcal) | 1625 (1226, 2050) | 1757 (1331, 2320) | 1950 (1573, 2377) | 1803 (1541, 2115) |

| Protein (g) | 64.2 (46.0, 86.2) | 68.9 (51.3, 94.8) | 75.4 (34.0, 95.0) | 73.8 (62.3, 89.4) |

| Carbohydrate (g) | 195.7 (145.0, 254.7) | 219.8 (165.6, 291.9) | 241.9 (197.1, 294.9) | 222.5 (183.1, 261.3) |

| Fat (g) | 63.0 (40.5, 82.2) | 67.9 (48.7, 86.5) | 69.3 (40.8, 92.5) | 66.7 (53.6, 81.9) |

| Saturated Fat (g) | 18.6 (11.8, 25.7) | 20.6 (14.8, 27.1) | 21.6 (15.0, 28.8) | 20.4 (15.6, 28.4) |

| Monounsaturated Fat (g) | 23.9 (15.4, 31.9) | 25.4 (18.3, 33.7) | 17.5 (10.1, 24.9) | 20.2 (14.6, 25.5) |

| Polyunsaturated Fat (g) | 14.1 (9.1, 20.4) | 16.0 (11.8, 21.4) | 9.1 (4.7, 15.0) | 10.7 (7.8, 14.2) |

| Cholesterol (mg) | 161 (103, 216) | 169 (124, 252) | 187 (122, 289) | 220 (142, 310) |

| Dietary fiber (g) | 18.5 (12.7, 24.0) | 18.7 (13.6, 28.8) | 19.7 (14.1, 27.1) | 18.5 (13.9, 25.0) |

| Vitamin A (IU) | 9179 (5476, 15010) | 9765 (6601, 18427) | 5399 (2868, 9924) | 7677 (4499, 11848) |

| Vitamin A (mcg RE) | 1252 (834, 1860.1) | 1308 (931, 2291) | 808 (492, 1258) | 1065 (707, 1536) |

| Vitamin E (mg α-TE) | 9.6 (6.5, 13.4) | 7.7 (7.2, 14.9) | 5.0 (2.9, 9.0) | 6.3 (4.5, 10.4) |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 117 (76, 178) | 140 (87, 200) | 89 (56, 139) | 96 (58, 149) |

| Thiamin (mg) | 1.3 (0.9, 1.7) | 1.5 (1.0, 1.9) | 1.0 (0.8, 1.4) | 1.3 (1.0, 1.6) |

| Riboflavin (mg) | 1.6 (1.2, 2.1) | 1.7 (1.3, 2.4) | 1.2 (0.9, 1.6) | 1.5 (1.2, 1.9) |

| Niacin (mg) | 20.1 (14.0, 25.6) | 21.2 (15.7, 28.5) | 15.6 (11.2, 21.2) | 9.8 (14.9, 24.7) |

| Folate (mg) | 345 (241, 470) | 382 (269, 561) | 250 (187, 381) | 350 (258, 441) |

| Vitamin B6 (mg) | 1.7 (1.3, 2.3) | 1.9 (1.4, 2.6) | 1.2 (0.8, 1.7) | 1.6 (1.1, 2.1) |

| Calcium (mg) | 691 (480, 987) | 776 (570, 1103) | 678 (520, 975) | 771 (595, 980) |

| Iron (mg) | 13.4 (9.8, 17.9) | 14.9 (10.4, 19.9) | 13.1 (10.6, 18.1) | 14.5 (11.0, 18.1) |

| Magnesium (mg) | 323 (238, 410) | 341 (256, 468) | 223 (152, 293) | 264 (210, 332) |

| Phosphorous (mg) | 1116 (812, 1478) | 1218 (915, 1683) | 818 (615, 1055) | 1034 (808, 1281) |

| Zinc (mg) | 9.5 (6.9, 13.4) | 11.1 (7.8, 17.5) | 6.4 (4.9, 8.9) | 8.4 (6.4, 11.6) |

| Potassium (mg) | 2935 (2183, 3887) | 3226 (2456, 4220) | 2113 (1560, 2908) | 2546 (1958, 3040) |

| Vitamin B12 (mg) | 3.5 (2.4, 5.1) | 3.9 (2.8, 6.3) | 2.7 (1.5, 4.2) | 3.6 (2.3, 5.4) |

| Sodium (mg) | 2502 (1756, 3253) | 2773 (1981, 3609) | 2941 (2013, 3904) | 2605 (2016, 3251) |

IQR=inter-quartile range (25th percentile, 75th percentile)

Concurrent Validity

Unadjusted correlations between Box-Cox transformed values obtained from the Web-PDHQ and Paper-DHQ ranged from 0.60 for Zinc to 0.81 for Vitamin A.(Table 3). Energy-adjusted correlations were lower, ranging from 0.28 to 0.73. food recordsfood recordsModerate mean correlations (unadjusted 0.41 and 0.38; energy-adjusted 0.41 and 0.34) were obtained between both the Web-PDHQ and Paper-DHQ with the 4-day food record on energy and nutrients, but the correlations between the Web-PDHQ and Paper-DHQ with the 24 hr. recalls, were modest (unadjusted 0.31 and 0.29; energy-adjusted 0.37 and 0.26). food recordfood recordPaper-DHQ correlations with the 24-hour recall and food recordfood record were similar to the Web-PDHQ correlations.

Table 3.

Pearson correlations between dietary assessment measures, unadjusted and adjusted for energy intake by the residual method.

| Nutrient Measured a | Web-PDHQ/Paper-DHQ n=210 | Web-PDHQ/Food recordFood record n=213 | Paper DHQ/Food recordFood record n=214 | Web-PDHQ/Recalls n=218 | Paper DHQ/24-hour. Recalls n=214 | Food recordFood Record/24-hour Recall n=217 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy (kcal) | 0.66 | 0.39 | 0.30 | 0.18 | 0.24 | 0.56 |

| Protein (g) | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 0.69 | 0.40 | 0.38 | 0.33 | 0.32 | 0.58 |

| Adjusted | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.24 | 0.45 | 0.24 | 0.43 |

| Carbohydrate (g) | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 0.67 | 0.44 | 0.44 | 0.24 | 0.31 | 0.54 |

| Adjusted | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.23 | 0.38 | 0.28 | 0.34 |

| Fat (g) | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 0.65 | 0.37 | 0.33 | 0.15 | 0.21 | 0.47 |

| Adjusted | 0.40 | 0.39 | 0.21 | 0.30 | 0.14 | 0.31 |

| Saturated Fat (g) | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 0.70 | 0.44 | 0.36 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.51 |

| Adjusted | 0.54 | 0.56 | 0.30 | 0.29 | 0.16 | 0.42 |

| Monounsaturated Fat (g) | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 0.64 | 0.34 | 0.33 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.39 |

| Adjusted | 0.40 | 0.36 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.09 | 0.27 |

| Polyunsaturated Fat (g) | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 0.63 | 0.28 | 0.25 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.35 |

| Adjusted | 0.38 | 0.21 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.28 |

| Cholesterol (mg) | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 0.72 | 0.53 | 0.46 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.54 |

| Adjusted | 0.65 | 0.64 | 0.45 | 0.44 | 0.34 | 0.51 |

| Dietary fiber (g) | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 0.78 | 0.58 | 0.60 | 0.48 | 0.51 | 0.59 |

| Adjusted | 0.65 | 0.55 | 0.50 | 0.57 | 0.49 | 0.56 |

| Vitamin A (IU) | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 0.81 | 0.46 | 0.51 | 0.36 | 0.38 | 0.35 |

| Adjusted | 0.73 | 0.46 | 0.51 | 0.40 | 0.39 | 0.35 |

| Vitamin A (mcg RE) | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 0.79 | 0.44 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.33 | 0.39 |

| Adjusted | 0.69 | 0.44 | 0.49 | 0.37 | 0.35 | 0.38 |

| Vitamin E (mg α-TE) | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 0.62 | 0.21 | 0.26 | 0.18 | 0.25 | 0.40 |

| Adjusted | 0.33 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.14 | 0.17 | 0.37 |

| Vitamin C (mg) | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 0.79 | 0.56 | 0.54 | 0.44 | 0.48 | 0.63 |

| Adjusted | 0.72 | 0.57 | 0.53 | 0.47 | 0.49 | 0.63 |

| Thiamin (mg) | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 0.73 | 0.40 | 0.33 | 0.35 | 0.29 | 0.43 |

| Adjusted | 0.47 | 0.46 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.20 | 0.39 |

| Riboflavin (mg) | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 0.74 | 0.34 | 0.29 | 0.33 | 0.20 | 0.41 |

| Adjusted | 0.54 | 0.43 | 0.25 | 0.43 | 0.20 | 0.38 |

| Niacin (mg) | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 0.70 | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.34 | 0.31 | 0.35 |

| Adjusted | 0.43 | 0.31 | 0.23 | 0.29 | 0.18 | 0.28 |

| Folate (mg) | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 0.75 | 0.49 | 0.42 | 0.27 | 0.23 | 0.37 |

| Adjusted | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.37 | 0.34 | 0.22 | 0.36 |

| Vitamin B6 (mg) | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 0.76 | 0.41 | 0.35 | 0.42 | 0.32 | 0.36 |

| Adjusted | 0.46 | 0.52 | 0.42 | 0.46 | 0.36 | 0.40 |

| Calcium (mg) | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 0.75 | 0.46 | 0.37 | 0.38 | 0.30 | 0.52 |

| Adjusted | 0.60 | 0.52 | 0.44 | 0.55 | 0.37 | 0.60 |

| Iron (mg) | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 0.74 | 0.45 | 0.40 | 0.35 | 0.27 | 0.40 |

| Adjusted | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.25 | 0.35 |

| Magnesium (mg) | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 0.72 | 0.48 | 0.41 | 0.44 | 0.40 | 0.50 |

| Adjusted | 0.51 | 0.48 | 0.34 | 0.48 | 0.29 | 0.45 |

| Phosphorous (mg) | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 0.71 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.35 | 0.34 | 0.41 |

| Adjusted | 0.46 | 0.40 | 0.27 | 0.42 | 0.22 | 0.31 |

| Zinc (mg) | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 0.60 | 0.33 | 0.32 | 0.27 | 0.21 | 0.25 |

| Adjusted | 0.28 | 0.27 | 0.22 | 0.19 | 0.12 | 0.17 |

| Potassium (mg) | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 0.74 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.38 | 0.42 | 0.51 |

| Adjusted | 0.54 | 0.47 | 0.41 | 0.49 | 0.38 | 0.46 |

| Vitamin B12 (mg) | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 0.69 | 0.29 | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.24 | 0.25 |

| Adjusted | 0.59 | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.31 | 0.23 | 0.23 |

| Sodium (mg) | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 0.71 | 0.36 | 0.30 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.45 |

| Adjusted | 0.69 | 0.44 | 0.49 | 0.37 | 0.35 | 0.38 |

Test-retest reliability

Mean reported intake was generally higher for the first Web-PDHQ administration compared to the second (Table 4). Mean unadjusted correlation between the two Web-PDHQ administrations within a 4-week period was 0.82.

Table 4.

Summary of energy and nutrient median (IQR) estimates for Web-PDHQ administrations spaced 1-week apart.

| Energy or Nutrient | Initial Web-PDHQ n=48 | Repeat Web-PDHQ n=48 | Unadjusted Pearson Correlation Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy (kcal) | 1814 (1418, 2370) | 1864 (1111, 2123) | 0.82 |

| Protein (g) | 78.7 (53.4, 103.9) | 69.2 (45.8, 89.9) | 0.79 |

| Carbohydrate (g) | 218.7 (174.4, 287.0) | 198.6 (142.3, 260.0) | 0.80 |

| Fat (g) | 67.6 (49.8, 100.5) | 69.3 (43.0, 85.4) | 0.82 |

| Saturated Fat (g) | 21.8 (14.3, 32.5) | 21.5 (13.5, 27.5) | 0.83 |

| Monounsaturated Fat (g) | 25.0 (18.1, 37.5) | 26.1 (16.5, 32.0) | 0.82 |

| Polyunsaturated Fat (g) | 15.8 (11.9, 22.3) | 14.6 (10.1, 19.8) | 0.77 |

| Cholesterol (mg) | 184 (142, 284) | 200 (105, 238) | 0.80 |

| Dietary fiber (g) | 22.8 (13.7, 27.7) | 17.3 (11.4, 22.0) | 0.82 |

| Vitamin A (IU) | 9504 (5579, 16958) | 7702 (5061, 12585) | 0.86 |

| Vitamin A (mcg RE) | 1241 (830, 2071) | 1098 (761, 1622) | 0.85 |

| Vitamin E (mg α-TE) | 10.9 (7.7, 14.3) | 9.8 (7.1, 12.5) | 0.72 |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 151 (85, 175) | 105 (63, 160) | 0.82 |

| Thiamin (mg) | 1.5 (1.1, 1.9) | 1.4 (0.9, 1.7) | 0.83 |

| Riboflavin (mg) | 1.7 (1.4, 2.5) | 1.6 (1.2, 2.3) | 0.85 |

| Niacin (mg) | 21.6 (16.4, 27.7) | 19.4 (13.4, 24.9) | 0.80 |

| Folate (mg) | 375 (278, 555) | 351 (240, 463) | 0.80 |

| Vitamin B6 (mg) | 2.0 (1.4, 2.5) | 1.5 (1.2, 2.3) | 0.85 |

| Calcium (mg) | 858 (619, 1322) | 696 (527, 1110) | 0.83 |

| Iron (mg) | 14.9 (11.0, 19.9) | 14.0 (10.5, 18.0) | 0.80 |

| Magnesium (mg) | 373 (264, 458) | 313 (233, 405) | 0.81 |

| Phosphorous (mg) | 1233 (1020, 1786) | 1196 (855, 1527) | 0.83 |

| Zinc (mg) | 13.8 (8.7, 19.4) | 10.7 (6.7, 18.5) | 0.81 |

| Potassium (mg) | 3502 (2551, 4187) | 2862 (2144, 3835) | 0.83 |

| Vitamin B12 (mg) | 4.2 (3.2, 6.6) | 4.1 (2.4, 6.4) | 0.81 |

| Sodium (mg) | 2834 (2136, 4008) | 2813 (1803, 3596) | 0.82 |

Usability Ratings

Subjective ratings were on a scale of 1 to 10 with 10 being the most favorable. Mean ratings for ease of completion were 9.4 (SD=1.2) out of 10 for both the Web-PDHQ and 9.2 (SD=1.4) Paper-PDHQ. Participants rated the Paper-DHQ as more amenable to modifying responses compared to the Web-PDHQ (Mean 9.4,SD= 2.8 versus 8.7, SD=2.2, p=0.003). Participants rated their ability to accurately estimate portion sizes slightly higher with the Web-PDHQ mean of 8.2 (SD=1.6) compared to the Paper-DHQ mean of 7.8 (SD=2.0) (p=0.01). For the Web-PDHQ, 66% of participants (n=214) relied on the pictures for at least half of the questions with only 9% stating that they didn't use the pictures at all.

Discussion

These data support comparable validity and reliability of the web-based, pictorial Diet History Questionnaire (DHQ) compared to the traditional paper-based DHQ. Mean unadjusted correlation of energy and the 25 examined nutrients between the paper and web-based versions of the Diet History Questionnaire administered one month apart was 0.71. Mean energy-adjusted correlation between the two DHQ's were lower (r=0.51). This is contrary to other FFQ validation studies, as energy adjustment typically does not affect or improves correlations (1). However, previous validation studies excluded individuals reporting extreme energy intakes. We chose not to exclude data based on reported energy intake as we were concerned this would lead to an inflated estimate of relative validity and reliability.

In the sub-sample of individuals (n=48) repeating the Web-PDHQ one week later, the correlations between the two Web-PDHQ administrations ranged from 0.77 to 0.85. These test-retest reliabilities are higher than the range of test-retest reliabilities (0.5 to 0.7) reported for other food frequency questionnaires(14).

With the notable exception of energy, the correlations between the Web-PDHQ and both the food record and 24-hour. recalls were also consistent with what has been reported in the literature (1). This is likely due to the differences in approach for data with extreme energy intakes. Similar to the current study, the Eating at America's Table Study reported deattenuated, unadjusted correlations ranging from 0.4 to 0.6 between the Diet History Questionnaire and four 24-hour. recalls (1). Though not directly comparable to the present study because four 24-hour recalls over a 1-yr period were used as the criterion measure rather than food records, the similarity in the correlation coefficients between the two studies supports the consistency of the measurement properties of the Web-PDHQ and the paper-based Diet History Questionnaire.

The correlations between the Web-PDHQ and 24-hour. recalls were lower than those using the Paper-DHQ or food records as the comparison measure. Two days of dietary recalls in a one month period may have been insufficient to account for the intra-individual variation in food intake being reported over a one year period for both forms of the DHQ. In addition to intra-individual variation, other potential sources of error include portion size estimation errors, staff experience conducting 24 hr. recalls, and nutrient analysis differences between the ESHA FoodProcessor Database and Diet*Calc Software.

Although entry criteria were broad in an attempt to improve generalizability, our study population was predominantly white, female, older, and more educated than the general U.S. adult population. As a result, one of the potential advantages of using a pictorial DHQ, improved understanding and assessment in those with limited reading ability, likely had limited impact on this highly educated sample. Future research should assess if a pictorial DHQ increases the reliability and validity of responses from low literacy participants.

The current study provides evidence to support the validity of a new administration method for a cognitively-based FFQ (15). We had hypothesized that pictures of actual food portions would improve the accuracy of the DHQ by reducing the measurement error due to food portion estimation errors, but the addition of the food pictures did not appear to improve the relationship of the DHQ to other food intake measures. This could be because food portion reporting was not improved by the pictorial representations or because the combination of prior experience with portion estimation in this sample (29% received prior training) and the portion estimation training required to complete the 24 hr. recalls and food recordsfood records for this study reduced the effect of the pictorial representations on food portion estimation. Although the Web-PDHQ does not appear to be superior to the DHQ on concurrent validity with other food intake measures, there are practical advantages of a web-based DHQ including remote administration, immediate nutrient analyses, and potential reductions in missing responses which may be of value for some research purposes. The Web-PDHQ does appear to be strongly associated with the paper-DHQ and has similar psychometric properties as the paper-DHQ, indicating that these two forms of DHQ administration produce comparable results.

References

- (1).Subar AF, Thompson FE, Kipnis V, Midthune D, Hurwitz P, McNutt S, et al. Comparative validation of the Block, Willett, and National Cancer Institute food frequency questionnaires: the Eating at America's Table Study. Am.J.Epidemiol. 2001 Dec 15;154(12):1089–1099. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.12.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Freedman LS, Potischman N, Kipnis V, Midthune D, Schatzkin A, Thompson FE, et al. A comparison of two dietary instruments for evaluating the fat-breast cancer relationship. Int.J.Epidemiol. 2006 May 3; doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Schatzkin A, Kipnis V, Carroll RJ, Midthune D, Subar AF, Bingham S, et al. A comparison of a food frequency questionnaire with a 24-hour recall for use in an epidemiological cohort study: results from the biomarker-based Observing Protein and Energy Nutrition (OPEN) study. Int.J.Epidemiol. 2003 Dec;32(6):1054–1062. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyg264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Subar AF, Kipnis V, Troiano RP, Midthune D, Schoeller DA, Bingham S, et al. Using intake biomarkers to evaluate the extent of dietary misreporting in a large sample of adults: the OPEN study. Am.J.Epidemiol. 2003 Jul 1;158(1):1–13. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Kristal AR, Peters U, Potter JD. Is it time to abandon the food frequency questionnaire? Cancer Epidemiol.Biomarkers Prev. 2005 Dec;14(12):2826–2828. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-ED1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Willett WC, Hu FB. Not the time to abandon the food frequency questionnaire: point. Cancer Epidemiol.Biomarkers Prev. 2006 Oct;15(10):1757–1758. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Kristal AR, Potter JD. Not the time to abandon the food frequency questionnaire: counterpoint. Cancer Epidemiol.Biomarkers Prev. 2006 Oct;15(10):1759–1760. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Willett WC, Hu FB. The food frequency questionnaire. Cancer Epidemiol.Biomarkers Prev. 2007 Jan;16(1):182–183. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).NutritionQuest [Accessed 11/15, 2007];NutritionQuest: Questionnaires and Screeners. Available at: http://www.nutritionquest.com/products/questionnaires_screeners.htm.

- (10).National Cancer Institute Risk Factor Monitoring and Methods, Cancer Control and Population Sciences. [Accessed 11/15, 2007];Diet History Questionnaire: Web-based DHQ. 2007 Available at: http://riskfactor.cancer.gov/DHQ/webquest/

- (11).Conway JM, Ingwersen LA, Moshfegh AJ. Accuracy of dietary recall using the USDA five-step multiple-pass method in men: an observational validation study. J.Am.Diet.Assoc. 2004 Apr;104(4):595–603. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Conway JM, Ingwersen LA, Vinyard BT, Moshfegh AJ. Effectiveness of the US Department of Agriculture 5-step multiple-pass method in assessing food intake in obese and nonobese women. Am.J.Clin.Nutr. 2003 May;77(5):1171–1178. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.5.1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).National Cancer Institute Risk Factor Monitoring and Methods, Cancer Control and Population Sciences. [Accessed 11/15, 2007];Diet History Questionnaire: Diet*Calc Software. 2007 Available at: http://riskfactor.cancer.gov/DHQ/dietcalc/index.html.

- (14).Cade J, Thompson R, Burley V, Warm D. Development, validation and utilisation of food-frequency questionnaires - a review. Public Health Nutr. 2002 Aug;5(4):567–587. doi: 10.1079/PHN2001318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Thompson FE, Subar AF, Brown CC, Smith AF, Sharbaugh CO, Jobe JB, et al. Cognitive research enhances accuracy of food frequency questionnaire reports: results of an experimental validation study. J.Am.Diet.Assoc. 2002 Feb;102(2):212–225. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]