INTRODUCTION

Numerous studies have documented alcohol's complex effects on health and mortality. Pearl first showed in 1923 that alcohol consumption and mortality had a U-shaped association, with intermediate alcohol consumption associated with lower mortality than either complete abstention or heavy alcohol use. [1] Many studies since have confirmed these results, with moderate drinkers (1 drink/day) having a lower mortality than either heavier drinkers or non-drinkers. [2-12]

However, people who drink alcohol are markedly different from people who do not drink alcohol and concerns remain that the lower mortality associated with moderate drinking may be due primarily to the favorable risk factor profile commonly seen in moderate drinkers. [13-15] Few epidemiologic studies have accounted for the wide range of risk factors that might confound the association between alcohol consumption and mortality. For example, while many studies have adjusted for traditional risk factors (demographic variables, smoking, binge drinking, obesity, exercise and comorbidities), few have adjusted for functional limitations that have been shown to be a powerful independent predictor of mortality. [16, 17] Furthermore, few studies have considered socioeconomic status (SES) beyond education or psychosocial factors such as depression, social support or religiosity. All of these factors are associated with mortality and are likely to differ between drinkers and non-drinkers, [14, 18-23] suggesting they may be important confounders of the alcohol-mortality relationship.

The history of estrogen replacement therapy (ERT) highlights the importance of considering these nontraditional risk factors. While ERT was shown to be protective in observational studies, [24] randomized trials demonstrated no benefit and possible harm. [25, 26] Subsequent studies have suggested that inadequate adjustment for confounders, particularly SES, may account for some of the erroneous conclusions drawn from the original observational studies. [27] Like users of ERT, moderate drinkers are more likely to be of higher SES and have better overall health, [14] suggesting that the apparent survival benefit of moderate alcohol use may also be due to the associated favorable risk factor profile seen in moderate drinkers.

Thus, our objective was to examine the relationship between alcohol and all-cause mortality, taking into account a wide range of risk factors that may confound this relationship. Besides accounting for the “traditional” risk factors that previous investigators have identified (age, gender, race and ethnicity, smoking, binge drinking, obesity, exercise and comorbidities) we also adjusted for functional limitations (ADLs, IADLs and mobility), SES (education, income and wealth) and psychosocial factors (depressive symptoms, social support, religiosity) [16-19, 23, 28] to determine whether accounting for these nontraditional confounding factors would eliminate the survival advantage for moderate drinkers.

METHODS

Participants

We studied community-dwelling participants interviewed in the 2002 wave of the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a nationally representative sample of all persons in the contiguous US age 55 and over. Data were collected primarily through telephone interviews, with an overall response rate of 81%. [29]

A total of 15,071 community-dwelling subjects age 55-110 were interviewed in 2002 for the HRS. We excluded participants if critical data needed for the analysis were missing such as 2006 vital status (196), alcohol consumption (3), comorbidities (20), functional status (4), education (4) and race (2). Subjects who reported no alcohol intake in 2002, but did report alcohol use in 2000 or 1998 were excluded (n=2323) to minimize the chances of classifying subjects who stop drinking due to worsening health as non-drinkers. Our final analytic sample consisted of 12,519 participants with 1338 individuals (11%) dying by 2006.

Measures: Outcome

The outcome of interest was death by the year 2006. Per HRS protocol, participants were considered deceased when a death was reported by the patient's proxy (usually a spouse) during the follow up interview in 2006. [29]

Measures: Primary Predictor

Alcohol consumption was ascertained by self-report. Subjects were asked, “Do you ever drink any alcoholic beverages such as beer, wine, or liquor?” If subjects reported no alcohol intake in 1998, 2000 and 2002, they were classified as non-drinkers.

If subjects endorsed current alcohol use, they were asked, “In the last three months, on average, how many days per week have you had any alcohol to drink?” and “...on the days you drink, about how many drinks do you have?” The frequency and amount of reported alcohol use allowed us to follow the convention of previous authors [11, 30] and categorize subjects into six categories: (1) Non-drinker, (2) <1 drink/week (<2g alcohol/day), (3) <1 drink/day (2-6.9g alcohol/day), (4) 1 drink/day (7-20.9g alcohol/day), (5) 2 drinks/day (21-34.9g alcohol/day) and (6) 3+ drinks/day (>35g alcohol/day).

Measures: Traditional Covariates

Predictor variables were ascertained by self-report. For demographics, participants were asked about their age, gender, race and ethnicity. For smoking, participants were asked, “Have you ever smoked cigarettes?” and “Do you smoke cigarettes now?” Participants were also asked about their weight and height, which allowed for calculation of body mass index (BMI). Participants were also asked about binge drinking (4+ drinks on one occasion) or vigorous exercise (sports, heavy housework or physical labor 3+ times/week).

For chronic conditions, participants were asked, “Have you ever had, or has a doctor told you, that you have/had X?” For many chronic conditions, follow-up questions provided information on the severity of disease. For example, participants who reported a history of diabetes mellitus were asked if they used insulin or had kidney disease. We examined a total of 7 conditions with up to 3 levels of severity: hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cancer, chronic lung disease, heart disease, congestive heart failure and stroke.

Measures: Function, SES and Psychosocial Covariates

For functional limitations, participants were asked “Because of a health or memory problem, do you have any difficulty with X?” Difficulties in 5 activities of daily living (ADL: bathing, dressing, eating, transferring and toileting); 5 instrumental activities of daily living (IADL: shopping, preparing meals, using the telephone, managing medications and managing finances) and walking were determined. For walking, participants were divided into 4 levels of severity: “difficulty walking 1 block,” “walks one to several blocks,” “walks several blocks but unable to jog 1 mile,” and “able to jog 1 mile.”

For socioeconomic status (SES), participants were asked about the highest educational degree that they obtained. Income from employment, Social Security, pensions, retirement account distributions and other sources were summed to determine the annual income for each participant. Wealth was determined by summing assets (including real estate, vehicles, retirement and bank accounts, Treasury bills and bonds) minus debts (mortgages and loans). [31] Because of the positively skewed nature of these variables, we categorized wealth (quartiles) and income (quintiles) for analysis.

For psychosocial factors, we assessed depressive symptoms using a modified 8-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression (CES-D) Scale. [32, 33] Participants were asked “Did you feel depressed much of time during the past week?” Similar questions explored other depressive symptoms including restless sleep, feelings of loneliness and sadness, decreased energy and enjoying life. Previous research focusing on social support have utilized questions such as, “How often do you get together with people...?” [18] or “Do you have someone you can count on for help?” [34] Our study participants were asked, “How often do you get together with your neighbors just to chat or for a social visit?” and “If you needed help with basic personal care activities like eating or dressing, do you have relatives or friends (besides your husband/wife/partner) who would be willing and able to help you over a long period of time?” For the importance of religion, we used the same question utilized by previous researchers, [28] asking, “How important is religion in your life; is it very important, somewhat important, or not too important?”

Statistical Analysis

Using maximum likelihood estimation multivariate logistic regression, we determined the relationship between various levels of alcohol consumption and 4-year mortality. Initially, we examined the relationship between alcohol and mortality only adjusting for demographic variables. Our subsequent analyses adjusted for traditional confounding factors (smoking, obesity, binge drinking, vigorous exercise and comorbidities) and nontraditional confounding factors (functional limitations, SES, depression, social support and religiosity) to determine the relative importance of each factor in confounding the alcohol-mortality relationship.

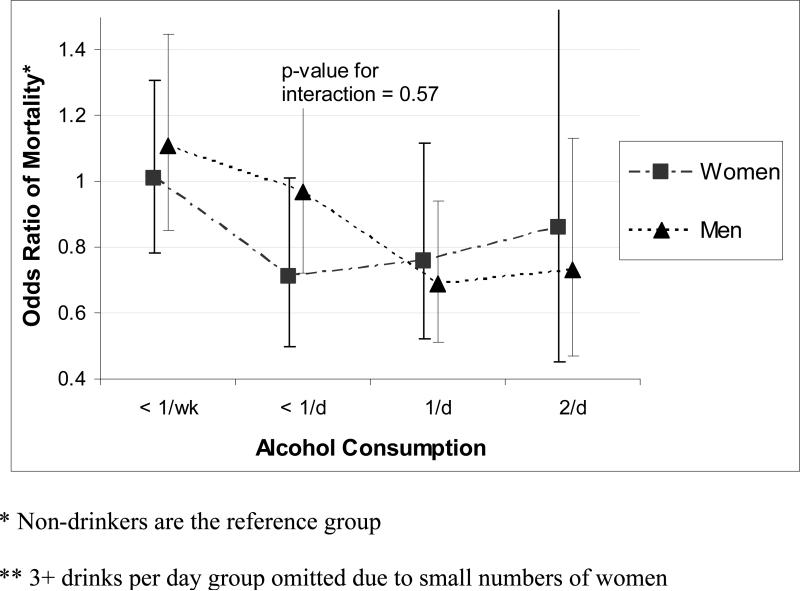

Previous work has suggested that the relationship between alcohol and mortality may differ between men and women. [3, 35] Thus, we performed gender-stratified analyses and determined the significance of a gender-alcohol interaction term in our multivariate models.

Because of our concerns about residual confounding, we augmented our primary analyses with a propensity score analysis comparing non-drinkers with moderate drinkers (1 drink per day). [36, 37] We determined the propensity of each subject of being a moderate drinker through logistic regression using the covariates from our primary analysis. We divided subjects into quintiles of propensity [38, 39] and found that in the lowest propensity quintile, there were very few moderate drinkers (n=35) compared to non-drinkers (n=1438). We omitted the lowest propensity quintile from further analysis and compared moderate drinkers to non-drinkers adjusting for propensity of moderate drinking along with our other covariates.

We also performed sensitivity analyses to determine the robustness of our findings. Previous researchers have proposed the “sick quitter” hypothesis, suggesting that the higher mortality seen in abstainers may be due to subjects in poor health stopping or curtailing their alcohol use. [15, 40, 41] We addressed this issue in two ways. First, we examined “recent quitters” (subjects who reported using alcohol in 1998 or 2000 but reported no alcohol in 2002) and found that these subjects had nearly identical rates of mortality compared to “non-drinkers” (subjects who reported no alcohol use in 1998, 2000 and 2002). Thus, we present our primary results with the recent quitters excluded. Second, as a sensitivity analysis, we excluded subjects who reported “Fair” or “Poor” overall health in 2002. Because our results were unchanged, we report our primary results with these subjects included. Second, we examined the effect of accounting for vigorous exercise and binge drinking as confounding factors. Because our results were unchanged, we report our primary results without these factors. Third, we examined the alcohol-mortality relationship at different ages. Given current concerns that maximum safe amounts of alcohol may be lower in men over 65, [42] we performed separate analyses for subjects under 65 and over 65. Because we found that our age-stratified results were similar to our non-stratified results, we report our primary, non-stratified results.

All statistics were performed using Intercooled Stata software (version 9.1; Stata Corporation, College Station, TX). The Committee on Human Research of the University of California, San Francisco and the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Research and Development committee approved this study.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the Participants

With the exception of smoking, which was more prevalent among moderate drinkers than non-drinkers (16% versus 12%), moderate drinkers had a more favorable risk factor profile across virtually every measure examined. (Table 1) For example, compared to non-drinkers, moderate drinkers were more highly educated (37% college compared to 14%), had more wealth (52% $300,000+ wealth compared to 21%) and reported fewer functional limitations (18% difficulty with walking several blocks compared to 41%). Moderate drinkers were more likely to be white (87% compared to 71%) and had lower rates of heart disease (20% compared to 29%). The mean age of our cohort was 69, with heavier drinkers being younger. Sixty percent of participants were women, with women overrepresented in the non-drinker group (70%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants

| Amount of Alcohol Consumed | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Drinker (n=5672) | <1/week (n=2327) | <1/day (n=1901) | 1/day (n=1691) | 2/day (n=550) | 3+/day (n=378) | |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age, mean (SD) | 71 (9) | 69 (9) | 68 (9) | 68 (9) | 68 (8) | 67 (8) |

| Women, % | 70 | 61 | 55 | 45 | 37 | 17 |

| Race/Ethnicity, % | ||||||

| White | 71 | 83 | 85 | 87 | 88 | 86 |

| Black | 18 | 11 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 8 |

| Other | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Hispanic | 10 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| Currently Smoking?, % | 12 | 12 | 11 | 16 | 23 | 32 |

| Body Mass Index, mean (SD) | 28 (6) | 28 (5) | 27 (5) | 26 (4) | 26 (4) | 26 (4) |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Cancer | 13 | 14 | 14 | 15 | 17 | 14 |

| Heart Disease | ||||||

| None | 71 | 78 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 |

| Angina | 26 | 20 | 18 | 19 | 18 | 19 |

| Heart Attack within 2 years | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| CES-D score, mean (SD) | 1.8 (2) | 1.3 (2) | 1.1 (2) | 1.1 (2) | 1.1 (2) | 1.5 (2) |

| Rare Social Visits | 31 | 28 | 24 | 24 | 28 | 29 |

| Religion very important, % | 80 | 65 | 58 | 52 | 43 | 39 |

| Socioeconomic Status | ||||||

| College degree or higher, % | 14 | 24 | 34 | 37 | 36 | 28 |

| $300K+ Wealth, % | 21 | 37 | 49 | 52 | 49 | 39 |

| Function | ||||||

| 1+ ADLs reported as “difficult” | 20 | 12 | 9 | 9 | 6 | 10 |

| Difficulty walking several blocks | 41 | 37 | 20 | 18 | 22 | 23 |

SD is standard deviation

CES-D is Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression (range 0-8)

ADL is activity of daily living

The relationship between alcohol and mortality was U-shaped, with the highest mortality of 14% among non-drinkers, reaching a nadir of 7% in moderate drinkers (1 drink/day), and rising to 12% in subjects reporting 3+ drinks/day. (Table 2)

Table 2.

Odds Ratios of 4-year Mortality with Differing Levels of Alcohol Consumption

| Amounts of Alcohol Consumed | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Drinker (n=5672) | <1/week (n=2327) | <1/day (n=1901) | 1/day (n=1691) | 2/day (n=550) | 3+/day (n=378) | |

| Mortality, (%) | 14 | 10 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 12 |

| Adjusted for: | ||||||

| Demographics only | Ref | 0.80 (0.67-0.94) | 0.56 (0.46-0.69) | 0.50 (0.40-0.62) | 0.65 (0.47-0.90) | 0.96 (0.68-1.35) |

| Demographics and Traditional Risk factors | Ref | 0.93 (0.78-1.10) | 0.67 (0.54-0.83) | 0.57 (0.46-0.72) | 0.67 (0.47-0.94) | 1.03 (0.72-1.47) |

| Demographics, CES-D, Social Support and Religion | Ref | 0.91 (0.77-1.08) | 0.68 (0.55-0.83) | 0.60 (0.48-0.75) | 0.75 (0.53-1.05) | 1.01 (0.71-1.44) |

| Demographics and Socioeconomic Status | Ref | 0.91 (0.77-1.08) | 0.69 (0.56-0.84) | 0.62 (0.50-0.77) | 0.77 (0.55-1.07) | 1.09 (0.77-1.53) |

| Demographics and Functional Limitations | Ref | 0.96 (0.80-1.14) | 0.74 (0.60-0.91) | 0.65 (0.52-0.81) | 0.79 (0.56-1.11) | 1.11 (0.78-1.58) |

| Fully Adjusted | Ref | 1.06 (0.89-1.28) | 0.85 (0.68-1.06) | 0.72 (0.57-0.91) | 0.78 (0.55-1.11) | 1.11 (0.77-1.60) |

| Fully Adjusted with Propensity Adjustment | Ref | 0.62 (0.48-0.80) | ||||

Demographic variables include age, gender and race/ethnicity

Traditional risk factors include comorbidities, smoking and obesity

CES-D is Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression (range 0-8)

The Relationship Between Alcohol and Mortality, Accounting for other Risk Factors

When we only adjusted for demographic variables (age, gender, race and ethnicity), all levels of alcohol consumption were associated with decreased odds of mortality, with an Odds Ratio (OR) of mortality in moderate drinkers (1 drink/day) of 0.50 (95% CI: 0.40–0.62). (Table 2, Line A) When we also accounted for traditional risk factors (comorbidities, smoking and obesity), we found that the association between alcohol and mortality was lessened, to an OR of 0.57 (95% CI: 0.46–0.72) (Table 2, Line B). Individual nontraditional risk factors attenuated the relationship between alcohol and mortality at least as much as traditional risk factors. For example, accounting for SES (Table 2, Line D) reduced the odds ratio to 0.62 (95% CI: 0.50 – 0.77) and accounting for functional limitations, reduced the OR to 0.65 (95% CI: 0.52 – 0.81). Accounting for all nontraditional risk factors (SES, functional status and psychosocial factors) simultaneously led to a marked attenuation of the alcohol-mortality relationship. For example, when nontraditional risk factors were considered in addition to traditional risk factors, moderate drinkers’ (1 drink/day) odds of mortality were attenuated from an OR of 0.57 (95% CI: 0.46–0.72) to 0.72 (95% CI: 0.57–0.91). The addition of nontraditional risk factors improved our ability to predict mortality, with the likelihood ratio test highly significant at p<0.001. Thus, accounting for all risk factors (comorbidities, smoking, obesity, functional, SES and psychosocial factors) explained almost half of the protective effect of alcohol, with the OR for moderate drinkers moving from 0.50 (95% CI: 0.40–0.62) to 0.72 (95% CI: 0.57–0.91).

Propensity Score Analysis of Non-drinkers and Moderate Drinkers

Our propensity score analysis suggested a stronger association between moderate alcohol use and decreased mortality compared to our traditional regression analysis. The OR's of mortality for moderate drinkers in our propensity-adjusted analysis was 0.62 (95% CI: 0.48–0.80) compared to 0.72 (95% CI: 0.57–0.91) in our regression analysis. (Table 2) The survival advantage for moderate drinkers was consistent across propensity for moderate drinking, with moderate drinkers in each quintile showing lower mortality rates than non-drinkers. (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Mortality in Non-Drinkers and Moderate Drinkers by Propensity Quintile

Gender Stratified Results

Our gender stratified analysis results were consistent with previous studies, suggesting that the amount of alcohol associated with the lowest mortality may be different among men and women. (Figure 2) In women, the lowest mortality was associated with subjects drinking <1 drink or 1 drink/day, whereas in men, the lowest mortality was associated with subjects drinking 1 or 2 drinks/day. However, our formal test for gender effect modification of the alcohol-mortality relationship was not statistically significant at p=0.57.

Figure 2.

Gender Differences in the Alcohol Mortality Relationship

DISCUSSION

While numerous previous studies have suggested that moderate drinkers have a survival advantage over non-drinkers, the interpretation of these studies is complex because moderate drinkers differ from non-drinkers in many characteristics that may confound this relationship. Few studies have adjusted for all these characteristics, and to our knowledge, no studies have simultaneously adjusted for functional status and SES. The central hypothesis for this study was that adjustment for these factors would explain the mortality advantage associated with moderate drinking.

We did find that moderate drinkers had a number of highly favorable characteristics including much lower rates of functional impairment, and considerably higher SES. We also showed that these factors are very important confounders of the alcohol-mortality relationship. Accounting for nontraditional risk factors (SES, functional status, and psychosocial factors) decreased the strength of association between moderate drinking and mortality from an OR of 0.57 to 0.72. Nonetheless, contrary to our hypothesis, even after extensive adjustment, moderate alcohol consumption was still associated with a substantial survival benefit.

There are two plausible interpretations of our results. First, by demonstrating a large protective association between moderate drinking and mortality even after extensive adjustment for powerful prognostic factors such as SES and functional status, our results significantly strengthens the evidence that moderate drinking leads to lower rates of overall mortality. On the other hand, a skeptic might reasonably note that adjustment for SES and functional status had a substantial impact on the alcohol-mortality relationship. It is quite plausible that moderate drinkers had other unmeasured favorable prognostic characteristics, and that adjustment for these characteristics could fully explain the alcohol mortality relationship. Given the complex web of associations between alcohol use, mortality and numerous risk factors, we believe this is a question that can only be answered through a randomized controlled trial examining clinical endpoints. [43] To date, trials examining alcohol have been short, small and focused on surrogate outcomes, [44-46] limiting their ability to address the central question of whether the survival benefit of moderate alcohol use seen in observational studies is causally due to alcohol. Clearly, a large, long-term trial examining clinical endpoints poses substantial logistical and ethical challenges. [47] But given the great public health implications of moderate alcohol use and the current clinical equipoise regarding the overall benefit or harm, we believe that the time has come to perform such a trial.

Our propensity score analysis results showed that our traditional multivariate analysis may have underestimated the protective effects of moderate alcohol use. After removing non-drinking subjects who had very few comparable moderate drinking counterparts in the lowest propensity quintile, our propensity results showed that moderate drinkers’ OR for mortality was 0.62, compared to 0.72 from our non-propensity analysis. One possible explanation for this difference could be that non-drinking subjects in the lowest quintile of propensity who were omitted may have been healthier in unmeasured ways than non-drinking subjects in other quintiles of propensity. Omitting these healthier non-drinkers would enrich the remaining non-drinking population with less healthy subjects at higher risk of mortality, increasing the apparent beneficial effects of moderate drinking.

Previous studies have suggested a survival advantage for very low levels of alcohol consumption (<1 drink/week). [3, 48, 49] Some have used these results as evidence that the association between moderate alcohol use and mortality is due to unmeasured confounding, since it seems biologically implausible that such low levels of alcohol could have significant health effects. When we accounted for previously unmeasured nontraditional risk factors (functional limitations, SES and psychosocial factors), we found that the survival benefit for rare drinkers (<1 drink/week) disappeared. Our findings suggest that the survival benefit in rare drinkers is not due to alcohol, but the favorable risk factor profile commonly seen in rare drinkers.

Our gender stratified results showed that the level of alcohol use associated with the lowest mortality was <1 drink/day to 1 drink/day in women, and 1 to 2 drinks/day in men. (Table 3) Our results are similar to those found in previous studies [8, 30] and are congruent with current US Department of Agriculture recommendations for maximum safe alcohol use (<2 drinks/day for men, and <1 drink/d for women). [50]

Our results provide a compelling illustration of the importance of adjusting for nontraditional risk factors such as SES and functional status in observational studies of health risk factors. While it is well known that these factors are powerful prognostic markers, few observational studies of health risks routinely adjust for these factors. The failure to adjust for these factors is now believed to be a major reason observational studies of estrogen use led to erroneous conclusions. Collection of data on function and SES should be routine in observational studies, and it should be standard practice to report adjustment for these factors in observational research.

Our results should be interpreted in the context of previous studies. First, by demonstrating that the protective effect of moderate alcohol use persists even after adjustment for functional status, SES and psychosocial factors, our study lends further support to the hypothesis that moderate alcohol use decreases mortality. Second, previous studies (including several examining the HRS cohort) have concluded that alcohol use has a U-shaped relationship with disability as well as mortality, with moderate use associated with less disability compared to complete abstention or heavy use. [48, 51-53] Thus, our results add to the literature by providing further evidence that moderate alcohol use is associated with decreased mortality as well as decreased disability even after extensive adjustment.

Our study has several limitations. First, our observational cohort study design precludes conclusions regarding causality. Thus, although our study provides supporting evidence for the beneficial effects of moderate alcohol use, questions regarding a causal relationship between moderate drinking and mortality must await a randomized trial. Second, information regarding alcohol use and other risk factors were obtained through subject report. This is a limitation that is shared with virtually all alcohol studies. Since respondents generally underestimate their alcohol intake, [12, 54] the specific amounts of alcohol associated with health outcomes should be interpreted with caution. Finally, while an important strength of our study was our extensive adjustment for possible confounders, over-adjustment may have occurred if we adjusted for a factor on the causal pathway between alcohol and mortality. We believe over-adjustment is less of a concern since all risk factor data was obtained simultaneously, making it less likely that one predictor (such as alcohol) is causing another factor (such as functional decline).

In summary, we found that moderate alcohol use is associated with many favorable nontraditional risk factors, including higher SES and fewer functional limitations. Accounting for these nontraditional risk factors had a significant impact on the alcohol-mortality relationship, eliminating the survival advantage for subjects who used alcohol rarely (<1 drink/week) and diminishing the survival advantage for moderate alcohol drinkers (1 drink/day).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The National Institute on Aging (NIA) supports the Health and Retirement Study (U01AG09740). This project was sponsored by a grant R01-AG023626. Dr. Lee was supported by the Hartford Geriatrics Health Outcomes Research Scholars Awards Program and the KL2RR024130 from the National Center for Research Resources, a component of the NIH. Dr. Covinsky was supported by grant K24-AG029812 from the NIA. This work was presented at the Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM) California Regional Meeting in March 2008, SGIM National Meeting in April 2008.

Sponsor's Role:

The funding sources had no role in the design or conduct of the study, data management or analysis, manuscript preparation or review.

Footnotes

| Elements of Financial/Personal Conflicts | SJL | RLS | BAW | KL | HLC | KEC | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Employment or Affiliation | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Grants/Funds | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Honoraria | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Speaker Forum | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Consultant | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Stocks | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Royalties | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Expert Testimony | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Board Member | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Patents | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Personal Relationship | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

REFERENCES

- 1.Pearl R. Alcohol and Mortality. In: Starling E, editor. The Action of Alcohol on Man. Longmans, Green and Co; London: 1923. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellison RC. Balancing the risks and benefits of moderate drinking. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;957:1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb02900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fuchs CS, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, et al. Alcohol consumption and mortality among women. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1245–1250. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505113321901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gmel G, Gutjahr E, Rehm J. How stable is the risk curve between alcohol and all-cause mortality and what factors influence the shape? A precision-weighted hierarchical meta-analysis. Eur J Epidemiol. 2003;18:631–642. doi: 10.1023/a:1024805021504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gronbaek M, Deis A, Becker U, et al. Alcohol and mortality: is there a U-shaped relation in elderly people? Age Ageing. 1998;27:739–744. doi: 10.1093/ageing/27.6.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klatsky AL, Udaltsova N. Alcohol Drinking and Total Mortality Risk. Annals of Epidemiology. 2007;17:S63–67. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moore AA, Giuli L, Gould R, et al. Alcohol use, comorbidity, and mortality. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:757–762. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rehm J, Gutjahr E, Gmel G. Alcohol and All-Cause Mortality: A Pooled Analysis. Contemporary Drug Problems. 2001;28:337–361. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reid MC, Boutros NN, O'Connor PG, et al. The health-related effects of alcohol use in older persons: a systematic review. Subst Abus. 2002;23:149–164. doi: 10.1080/08897070209511485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Room R, Babor T, Rehm J. Alcohol and public health. Lancet. 2005;365:519–530. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17870-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thun MJ, Peto R, Lopez AD, et al. Alcohol consumption and mortality among middle-aged and elderly U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1705–1714. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199712113372401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poikolainen K. Alcohol and mortality: a review. J Clin Epidemiol. 1995;48:455–465. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)00174-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fillmore KM, Golding JM, Graves KL, et al. Alcohol consumption and mortality. I. Characteristics of drinking groups. Addiction. 1998;93:183–203. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.9321834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naimi TS, Brown DW, Brewer RD, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors and confounders among nondrinking and moderate-drinking U.S. adults. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28:369–373. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shaper AG, Wannamethee G, Walker M. Alcohol and mortality in British men: explaining the U-shaped curve. Lancet. 1988;2:1267–1273. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)92890-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inouye SK, Peduzzi PN, Robison JT, et al. Importance of functional measures in predicting mortality among older hospitalized patients. JAMA. 1998;279:1187–1193. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.15.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee SJ, Lindquist K, Segal MR, et al. Development and validation of a prognostic index for 4-year mortality in older adults. JAMA. 2006;295:801–808. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.7.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greenfield TK, Rehm J, Rogers JD. Effects of depression and social integration on the relationship between alcohol consumption and all-cause mortality. Addiction. 2002;97:29–38. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Makela P. Alcohol-related mortality as a function of socio-economic status. Addiction. 1999;94:867–886. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.94686710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nielsen NR, Schnohr P, Jensen G, et al. Is the relationship between type of alcohol and mortality influenced by socio-economic status? J Intern Med. 2004;255:280–288. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2003.01268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodgers B, Korten AE, Jorm AF, et al. Risk factors for depression and anxiety in abstainers, moderate drinkers and heavy drinkers. Addiction. 2000;95:1833–1845. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.9512183312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schnohr C, Hojbjerre L, Riegels M, et al. Does educational level influence the effects of smoking, alcohol, physical activity, and obesity on mortality? A prospective population study. Scand J Public Health. 2004;32:250–256. doi: 10.1080/14034940310019489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murray RP, Rehm J, Shaten J, et al. Does social integration confound the relation between alcohol consumption and mortality in the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial (MRFIT)? J Stud Alcohol. 1999;60:740–745. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grady D, Rubin SM, Petitti DB, et al. Hormone therapy to prevent disease and prolong life in postmenopausal women. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117:1016–1037. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-117-12-1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hulley S, Grady D, Bush T, et al. Randomized trial of estrogen plus progestin for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in postmenopausal women. Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study (HERS) Research Group. JAMA. 1998;280:605–613. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.7.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Humphrey LL, Chan BK, Sox HC. Postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy and the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:273–284. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-4-200208200-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Michalak L, Trocki K, Bond J. Religion and alcohol in the U.S. National Alcohol Survey: how important is religion for abstention and drinking? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;87:268–280. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sample Sizes and Response Rates (2002 and beyond) [Aug 21, 2008];2007 Mar 2; [on-line] Available at: http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/intro/sho_uinfo.php?hfyle=sample_new_v3&xtyp=2.

- 30.Liao Y, McGee DL, Cao G, et al. Alcohol intake and mortality: findings from the National Health Interview Surveys (1988 and 1990). Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151:651–659. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.St Clair P, Bugliari D, Chien S, et al. RAND HRS Data Documentation, Version D. RAND Center for the Study of Aging; 2004. p. 981. Apr. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Turvey CL, Wallace RB, Herzog R. A revised CES-D measure of depressive symptoms and a DSM-based measure of major depressive episodes in the elderly. Int Psychogeriatr. 1999;11:139–148. doi: 10.1017/s1041610299005694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weissman MM, Sholomskas D, Pottenger M, et al. Assessing depressive symptoms in five psychiatric populations: a validation study. Am J Epidemiol. 1977;106:203–214. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andrew MK, Mitnitski AB, Rockwood K. Social vulnerability, frailty and mortality in elderly people. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2232. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mukamal KJ, Conigrave KM, Mittleman MA, et al. Roles of drinking pattern and type of alcohol consumed in coronary heart disease in men. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:109–118. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosenbaum P, Rubin DB. The Central Role of the Propensity Score in Observational Studies for Causal Effects. Biometrika. 1983;70:44–55. [Google Scholar]

- 37.D'Agostino RB., Jr Propensity score methods for bias reduction in the comparison of a treatment to a non-randomized control group. Stat Med. 1998;17:2265–2281. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19981015)17:19<2265::aid-sim918>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. Reducing Bias in Observational Studies Using Subclassification on the Propensity Score. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1984;79:516–524. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rubin DB. Estimating causal effects from large data sets using propensity scores. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:757–763. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-8_part_2-199710151-00064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wannamethee SG, Shaper AG. Lifelong teetotallers, ex-drinkers and drinkers: mortality and the incidence of major coronary heart disease events in middle-aged British men. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26:523–531. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.3.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fillmore KM, Stockwell T, Chikritzhs T, et al. Moderate alcohol use and reduced mortality risk: systematic error in prospective studies and new hypotheses. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17:S16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.NIAAA Helping Patients Who Drink Too Much: A Clinician's Guide. 2005 NIH Publication # 07-3769. Available at: http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Practitioner/CliniciansGuide2005/guide.pdf.

- 43.Petitti DB, Freedman DA. Invited commentary: how far can epidemiologists get with statistical adjustment? Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162:415–418. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi224. discussion 419-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davies MJ, Baer DJ, Judd JT, et al. Effects of moderate alcohol intake on fasting insulin and glucose concentrations and insulin sensitivity in postmenopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;287:2559–2562. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.19.2559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marfella R, Cacciapuoti F, Siniscalchi M, et al. Effect of moderate red wine intake on cardiac prognosis after recent acute myocardial infarction of subjects with Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med. 2006;23:974–981. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shai I, Wainstein J, Harman-Boehm I, et al. Glycemic effects of moderate alcohol intake among patients with type 2 diabetes: a multicenter, randomized, clinical intervention trial. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:3011–3016. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mukamal KJ, Rimm EB. Alcohol's effects on the risk for coronary heart disease. Alcohol Res Health. 2001;25:255–261. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Byles J, Young A, Furuya H, et al. A drink to healthy aging: The association between older women's use of alcohol and their health-related quality of life. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1341–1347. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, et al. Mortality in relation to alcohol consumption: a prospective study among male British doctors. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:199–204. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005 [Mar 3, 2008];2007 June 29; Available at: http://www.health.gov/DietaryGuidelines/dga2005/document/default.htm.

- 51.Lang I, Guralnik J, Wallace RB, et al. What level of alcohol consumption is hazardous for older people? Functioning and mortality in U.S. and English national cohorts. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:49–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.01007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ostermann J, Sloan FA. Effects of alcohol consumption on disability among the near elderly: a longitudinal analysis. Milbank Q. 2001;79:487–515. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Perreira KM, Sloan FA. Excess alcohol consumption and health outcomes: a 6-year follow-up of men over age 50 from the health and retirement study. Addiction. 2002;97:301–310. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Polich JM. Epidemiology of alcohol abuse in military and civilian populations. Am J Public Health. 1981;71:1125–1132. doi: 10.2105/ajph.71.10.1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]