Abstract

This paper reviews evidence for deficits in goal regulation in bipolar disorder. A series of authors have described mania as related to higher accomplishment, elevated achievement motivation, and ambitious goal setting. These characteristics appear to be evident outside of episodes, and to some extent, among family members of people with a history of mania. In addition, people with a history of mania demonstrate intense mood reactivity, particularly in response to success and reward. During positive moods, they appear to experience robust increases in confidence. These increases in confidence, coupled with a background of ambitious goals, are believed to promote excessive pursuit of goals. This excessive goal engagement is hypothesized to contribute to manic symptoms after an initial life success.

1. Introduction

Genetic vulnerability has been estimated to account for as much as 85% of the variance in who develops mania (McGuffin et al., 2003; Vehmanen, Kaprio, & Loennqvist, 1995). Nonetheless, there is tremendous variability in the course of bipolar disorder, both between and within individuals. To understand this variability, it is important to identify triggers that determine how and when the biological vulnerability is expressed. This article examines the idea that the genetic vulnerability to mania is expressed behaviorally in dysregulated goal pursuit, and that excessive goal pursuit serves as a trigger for manic symptoms.

Over the past 100 years, clinicians and researchers have described various facets of goal setting and goal pursuit among people with a history of mania. The first part of this article reviews this evidence. Early studies focused on high accomplishment, both by persons with a history of mania and by their family members. A second set of studies examined traits that may explain accomplishment among these people, including achievement motivation and high ambitions. A third body of literature centers on mood reactivity and related cognitive changes that occur among people with a history of mania under certain goal-related circumstances. In particular, a set of studies is examined that focuses on confidence during positive moods.

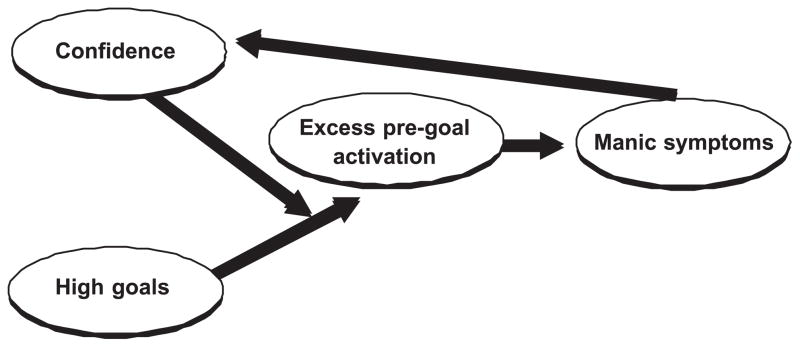

The final section of this paper presents a model that focuses on two themes in goal regulation: constantly high ambitions and fluctuating confidence. It is argued that bursts of extreme confidence, against a background of stably high ambitions, contribute to excessive goal pursuit, which can spiral into mania. The article closes with a brief discussion of future research goals and clinical implications.

This paper focuses on mania. As such, this paper will review studies that have focused on bipolar I disorder, defined by the presence of at least one full manic episode, bipolar II disorder, which is defined on the basis of hypomania (less severe periods of manic symptoms), and studies of people at-risk for the development of mania. Parallels and distinctions across these three populations will be noted where possible. Unfortunately, many relevant studies examined bipolar disorder as a whole, without distinguishing mania from depression. These studies are surely relevant to mania, because the diagnostic definition of bipolar disorder does not require an episode of depression (APA, 2002). Indeed, in community samples, 25–33% of individuals with a lifetime history of mania report no episodes of depression (Karkowski & Kendler, 1997; Kessler, Rubinow, Holmes, Abelson, & Zhao, 1997; Weissman & Myers, 1978). Nonetheless, the failure to disentangle these aspects of bipolar disorder raises an ambiguity in some of the research. Where analyses differentiate mania from depression, it will be noted.

2. Review of existing evidence

2.1. Achievement by people with a history of mania

High levels of accomplishment among people with mood disorders were noted almost 100 years ago. For example, Stern (1913) examined the occupational status of 1326 individuals admitted to the Psychiatric Clinic in Freiburg between 1906 and 1912. He found that patients with affective psychosis or their fathers were more likely to be professionals than were patients with schizophrenia or their fathers. Consistent with this, a report concerning the United States census data on hospital admissions (Tietze, Lemkau, & Cooper, 1941) stated that people with manic-depression were more likely than those with schizophrenia to come from higher economic classes. Over the next several decades links between high socioeconomic status (SES) and manic-depression were replicated in other studies of public hospital admissions (Faris & Dunham, 1939; Malzberg, 1956), particularly first admissions (Gershon & Liebowitz, 1975). Although those early studies did not typically differentiate people with a history of mania from those with depression, a recent study of first admissions suggested that blue-collar backgrounds were less common among people with both depression and mania than those with schizophrenia (Bromet et al., 1996).

Intrigued by these early findings, researchers began to study whether bipolar disorder conferred social advantages compared to the absence of disorder. The research literature burgeoned. By 1967, Dohrenwend and Dohrenwend identified 30 studies of SES and mental illness. However, the findings were inconsistent and did not always support links between bipolar disorder and social accomplishment. One methodological issue that could explain the inconsistency is that most studies were based on treatment samples, recruited from either public or private hospitals (Dohrenwend & Dohrenwend, 1967). These hospitals were quite stratified economically, an effect that was further enhanced by the fact that the hospital system at that time typically had separate hospitals for African Americans, who often were paid less than Caucasian Americans (Malzberg, 1956). The range of social class was limited within each sample, which would constrain the magnitude of correlations between SES and diagnosis.

The Dohrenwends identified seven studies of social class and psychiatric disorder that included treated and untreated cases. In each study, mania was underrepresented in lower classes. The same pattern was observed in studies conducted in Manhattan, Iceland, Japan, and Germany (Dohrenwend & Dohrenwend, 1967) and has since been replicated in Italy (Lenzi et al., 1993). These findings do not appear to be an artifact of greater awareness of diagnosis among upper class individuals—the association has been documented in epidemiological studies that have used standardized, reliable diagnostic interviews. For example, Weissman & Myers (1978), in their epidemiological study of 988 persons in urban areas of the United States, found that a history of mania was more common among social classes I and II (4.6%) than in Class III (1%), IV (0.9%), or V (0%). It should be noted that not every epidemiological study has replicated this finding (Kessler, Rubinow, Holmes, Abelson, & Zhao, 1997). Nonetheless, nine out of 10 studies of treated and untreated cases have found that a history of mania is associated with higher SES. This pattern was to the opposite of that observed for other major psychiatric disorders, including major depression (Bebbington, 1991; Weissman et al., 1993).

Interpretation of these findings, though, is somewhat complicated. Many of the early studies on SES and hospital admission were conducted at a time when a person might be hospitalized in early adulthood and remain institutionalized for decades. That is, these early studies may be most relevant for understanding social status early in life. As such, these studies are difficult to interpret: social status could reflect a patient’s early accomplishments or their family status. Even some community studies examine SES using broad definitions that blur patient and family accomplishments. Hence, there is a need for studies that examine the individual achievements of patients, as well as those of their family members.

In one recent community study, those with bipolar disorder were no more likely to graduate college by early adulthood than the general population (Lewinsohn, Seeley, Buckley, & Klein, 2002). The null findings are not surprising, though, for the following reason: symptoms of mania undermine social and occupational functioning (see Hammen & Cohen, 2004 for a review). Approximately one-third of people hospitalized for mania remain unemployed for a year thereafter (Harrow, Goldberg, Grossman, & Meltzer, 1990). As described by Adler (1964), “brilliant beginnings and sudden anticlimaxes are repeated at intervals through life histories” (p. 27, cited in Peven & Shulman, 1983). Given that symptoms interfere with functioning, high accomplishments are more likely to be documented in studies that consider successes either before illness onset or at maximum lifetime levels.

Much of the work concerning lifetime accomplishments has focused on highly creative individuals. Kay Jamison (1996) brought public attention to creativity and mental illness when she published an extensive list of famous authors, and artists who are believed to have suffered from mania. The few available studies provide evidence consistent with Jamison’s biographical research. For example, Andreasen (1987) found that 30 writers who were enrolled in the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, one of the most prestigious national forums for writers, were more likely to meet criteria for mania or hypomania than 30 controls (43% compared to 10%). Similarly, in a study of nationally recognized writers and artists, 25% reported extended periods of elated moods, and 33% of poets reported receiving treatment for mania (Jamison, 1989). Hence, in samples defined by creative accomplishments, manic or hypomanic symptoms appear to be overrepresented. These studies, though, started with the exceptional accomplishments, and then assessed the rates of symptoms. This might suggest more widespread effects than exist in the general population of people with bipolar disorder. These studies do not inform us about how common such accomplishments are for persons with a history of mania.

A few studies have focused on mean levels of lifetime accomplishment among broader samples of persons with a history of mania. In one study of 34,457 people hospitalized for mental illness, people with manic-depressive disorder were more likely to be professionals than other patients (Odegaard, 1956). Results of other studies suggested that patients with manic-depressive disorder have higher lifetime educational attainment compared to both normative levels (Petterson, 1977) and patients with neurotic disorders (Parker, Spielberger, Wallace, & Becker, 1959). DeLong and Aldershof (1983) reported a greater likelihood of exceptional math, artistic, or language skills among 11 individuals with early onset mania. In sum, these early findings suggest above average attainment among individuals with a history of mania.

In these studies of lifetime educational accomplishment, early researchers generally did not use objective measures to confirm diagnoses or accomplishments. A few studies of accomplishment have confirmed diagnoses, however. Woodruff, Robins, Winokur, and Reich (1971) found that 29 participants with bipolar disorder completed significantly more years of schooling than 41 participants with unipolar disorder. In this study, bipolar and unipolar groups did not differ on occupational prestige.1

Other studies suggest that mania versus hypomania may be associated with distinct patterns. For example, Coryell et al. (1989) studied 442 probands with major depression, 64 with bipolar II disorder, and 88 with bipolar I disorder recruited from university outpatient psychiatry clinics. The three groups did not differ on rates of college graduation, and the women did not differ by group on the Hollingshead status rating of the best position held. However, men in the bipolar II group had held significantly higher occupational positions than men in the bipolar I group, who did not differ from men with depression. Similarly, Richards, Kinney, Lunde, and Benet (1988) found that people with a history of hypomanic episodes, but not those with a history of manic episodes, reported higher lifetime creativity scores compared to nondisturbed controls. These findings suggest that severe mania may undermine accomplishments, whereas hypomanic symptoms may promote creativity and occupational advancement compared to other patients or to the general population.

As with studies of lifetime accomplishment, little research on premorbid function is available. In the available studies, researchers have tended to compare people with a history of mania to those with schizophrenia and other mental illnesses and to focus on problems rather than strengths (Bromet et al., 1996; Cannon, Jones, Gilvarry, & Rifkin, 1997; Gilvarry et al., 2000). Further, in some studies, it is not clear whether functioning was measured before illness onset (cf. Cannon, Jones, Gilvarry, & Rifkin, 1997). As noted by Kutcher, Robertson, and Bird (1998), premorbid studies are difficult to conduct, as individuals may experience a long prodrome before a full-blown manic episode or diagnosis emerges. In one survey, people reported that it took an average of 8 years from the time of first symptom until they received a diagnosis of bipolar disorder (Lish, Dime-Meenan, Whybrow, Price, & Hirschfeld, 1994). Careful assessments must be used to document symptoms that emerged before treatment and diagnosis, and given that onset is typically during late adolescence, researchers must use instruments that are tailored for children and adolescents (Youngstrom, Findling, & Feeny, 2004). Most studies of functioning do not meet these criteria.

In one study of functioning before the onset of mania, Kutcher, Robertson, and Bird (1998) found that 30% of children had interpersonal relationships that were excellent and above normative expectations, and approximately 2/3 had academic performance in the good to excellent range. Unfortunately, the absence of a control group precludes statements regarding strengths compared to the general population. The findings, however, do suggest the need for studies of premorbid accomplishment in people who do and do not develop mania.

To summarize the evidence reviewed in this section, many early researchers found that people who were hospitalized for mania demonstrated higher SES levels than other hospitalized patients. Although findings from hospital admission studies were not entirely consistent, many epidemiological studies have documented the same pattern. That is, most studies of treated and untreated cases have found that a history of mania is associated with higher SES compared to no mental illness. Unfortunately, studies of SES may blur distinctions between patient and family member accomplishments. Studies of patient accomplishment are complicated to conduct. Because episodes interfere with role performance, it is important to be sensitive to the trajectory of social and occupational functioning across the life course. Studies of maximum lifetime accomplishment and premorbid successes appear most helpful on this front. The few available studies, along with case reports and biographical analyses, suggest that people with a history of manic symptoms are overrepresented in samples of highly accomplished creative individuals. People with a history of hypomanic episodes report more creative, educational, and occupational attainments across the life course than people with depression or those with no psychiatric diagnoses. One study of premorbid function suggests that people who develop manic episodes may experience above average interpersonal and academic functioning before illness onset. Severe manic episodes, however, may interfere with occupational and educational accomplishments.

2.2. Achievement by family members of people with a history of mania

There is also clinical literature and evidence pertaining to family members of people with mania. Myerson and Boyle (1941) were among the first to examine the family accomplishments of people treated for manic-depression. Working with the Committee on Heredity and Eugenics of the American Neurological Association, they developed an argument against sterilization that drew on the remarkable successes of these families.

…In these families, we find a spread of talent of the most significant nature. There have been several governors of Massachusetts. There have been a great many Federal judges, including chief justices of the Supreme court, numerous members of the Constitutional Congress and of the Senate and House of Representatives which succeed these bodies; Secretaries of State; ambassadors to the great foreign powers; great and significant lawyers; founders of institutions of all types—colleges, churches, business houses of the most significant importance. The people of these families have built railroads, financed and carried through in important measure all of the great enterprises around which American industrial life has been built in the last century. In practically every family, there have been members who devoted themselves to the accumulation of riches in a most successful way… These families have also boasted presidents of the United States, philosophers of international importance, writers who have founded schools of literature; scientists in every field from astronomy to chemistry; medical men galore, around whose names significant developments have clustered…(pp. 16–17).

Beyond these observations, empirical studies have provided evidence for high achievement among the family members of people with a history of mania. For example, in three studies, family members of bipolar probands were found to have higher lifetime occupational and educational attainment than family members of unipolar probands, who appeared comparable to the general population (Coryell et al., 1989; Tsuchiya, Agerbo, Byrne, & Mortensen, 2004; Woodruff, Robins, Winokur, & Reich et al., 1971). In two studies that examined family diagnostic status these advantages among the family members of bipolar individuals were true for affected and unaffected individuals. For example Richards, Kinney, Lunde, and Benet (1988) reported higher Lifetime Creativity scores among the nonaffected family members of patients with a history of mania compared to normal controls. However, Coryell found the most striking advantages for the family members who had had at least hypomanic episodes.

One conflicting finding in this respect has emerged. An epidemiological study that included 16 adolescents with mania, compared to those with no mental illness, found that parental education levels did not differ (Lewinsohn, Klein, & Seeley, 1995). With this exception, however, mania has been associated with higher lifetime achievement among family members in available studies.

2.3. Why the high attainments?

Most of the findings reviewed here suggest that high levels of lifetime accomplishment can be documented among people with manic symptoms, particularly among those who experience hypomanic rather than manic episodes. Moreover, four of five studies suggest that family members of people with a history of mania demonstrate high levels of accomplishment. How are these effects to be explained?

A successful family can provide opportunities for offspring who are bipolar, as well as other family members. Although it leaves open the question of how these families accomplished more in the first place, this raises questions about the relative importance of environmental and biological pathways.

One study of adopted offspring provides tentative clues regarding this issue. McNeil (1971) studied adoptees who had and had not achieved national recognition for creative accomplishments. As with research described above, he found that rates of mental illness were higher (30%) in highly creative individuals than in less creative individuals (10%). Rates of mental illness in the adoptive parents were not associated with creativity in the offspring. On the other hand, mental illness in the biological parents was associated with creativity in the offspring; 27.7% of the nationally prominent individuals had mentally ill biological parents, compared to approximately 10% of the less creative individuals. These findings suggest that links between creativity and mental illness are more genetic than environmental. Unfortunately, this study did not specifically examine mania, but rather bipolar disorder without differentiation of mania and depression. Nonetheless, as mania is more strongly associated with creativity than are other mental illnesses, the findings do have some bearing.

How might a genetic link be mediated? One possibility is that higher accomplishment would result if the genetic vulnerability to mania were linked to high IQ. To the contrary, several studies show that people with a history of mania perform more poorly than nondisturbed controls on IQ measures (Bromet et al., 1996; Martinez-Aran et al., 2000; van Gorp, Altshuler, Theberge, & Mintze, 1999). The only study to find higher IQ among persons with bipolar disorder (Mason, 1956) used the Army General Classification Test. This test, by virtue of the multiple-choice format, has been found to yield higher scores for people who are willing to guess (Duncan, 1947). As is discussed below, confidence may be elevated for people with bipolar disorder at times, suggesting a potential willingness to guess. Alternatively, the Mason study may offer a better estimate of premorbid IQ than other studies, because most participants were tested before the illness was full-blown.

Because of the influence of symptoms and medications on IQ scores (Judd, 1979), studies of unaffected family members are particularly important. There is no support for this hypothesis of higher IQ in these studies. Offspring of persons with mania have been found to have IQ scores that are lower than or comparable to the general population and other psychiatric control groups (Decina et al., 1983; Waters, Marchenko-Bouer, & Smiley, 1981; Worland & Hesselbrock, 1980). In sum, higher IQ does not appear to explain the attainment associated with a history of mania.

2.4. Achievement motivation

Another possibility is that genetic vulnerability to mania could be related to traits other than intelligence that promote achievement. Among healthy individuals, setting high goals facilitates achievement on tasks, and one of the best predictors of high goal setting is achievement motivation (Locke & Latham, 2002). Given this, the temperamental quality of achievement motivation and the related outcome of high goal setting seem important to examine in relation to mania.

Early clinical observations suggested elevated drive, ambition, and achievement motivation were characteristic of the family members of people with a history of mania (Spielberger, Parker, & Becker, 1963). For example, family members of people with mania were described as upward striving and achievement focused (Cohen et al., 1959) and as competitive and ‘striving for prestige and social approval’ (Gibson, 1958). Authors often interpreted familial elevations of achievement motivation as evidence that maladaptive family environments elicit symptoms of mania. As a consequence, this literature was ignored once the high heritability for this disorder became apparent. Few scholars, it seems, considered the possibility that these family traits could themselves be a manifestation of underlying genetic vulnerability. Perhaps because of this, apparently no one has used standardized measures to assess achievement motivation within family members.

As with families, clinicians have reported high goals, drive, and work motivation among individuals with a history of mania (Akiskal, Hirschfeld, & Yerevanian, 1983). For example, in a case report of 17 patients with a history of mania, Peven and Shulman (1983) noted, “…their goals are to achieve prominence and prestige, but these goals are inappropriately high” (p. 13).

Congruent with clinical observations, empirical studies indicate that a history of mania is associated with traits related to setting and valuing goals. Indeed, only one study failed to document higher emphasis on goals among individuals with a history of mania, and that study may have been limited by the reliance on only 16 participants (Becker & Altrocchi, 1968).

Other studies have consistently found that a history of mania is associated with stronger emphasis on goals, even during euthymic periods. For example, persons with remitted bipolar disorder endorsed valuing achievement more than healthy controls did on a brief self-report measure (Spielberger, Parker, & Becker, 1963). In that study, 93% of individuals with a history of mania endorsed the item, “I nearly always strive hard for personal achievement.”

Two studies have found that compared to individuals with no mood disorder, individuals with a history of mania in remission are more likely to endorse items reflecting perfectionism and the need to achieve goals on the dysfunctional attitudes scale (Lam, Wright, & Smith, 2002; Scott, Stanton, Garland, & Ferrier, 2000). Items on this scale include “A person should do well on everything he undertakes” and “If I try hard enough, I should be able to excel at anything I attempt.” Hence, people with a history of mania appear to be more motivated to achieve high goals than other people.

A reasonable question would be whether this motivation to achieve is just a state-dependent feature of mania. Two sorts of evidence provide help in determining whether this motivation is a constant trait-like characteristic or is just present during symptomatic periods. First, empirical studies of achievement motivation have assessed people with bipolar disorder during remission (Lam Wright, & Smith, 2002; Meyer, Johnson, & Winters, 2001; Scott, Stanton, Garland, & Ferrier, 2000). In these studies, lifetime mania has related to valuing goals, even after controlling for baseline subsyndromal mood symptoms (Johnson, Ruggero, & Carver, in press). Second, current symptoms of mania do not correlate with achievement motivation (Lozano & Johnson, 2001; Scott et al., 2000). Hence, it appears that the emphasis on ambitious goals is not the result of current affect or manic symptoms. One caveat is important though. It may be that this high ambition reflects the presence of a single symptom of mania, that of grandiosity. We are unaware of studies that have carefully tested overlap between this single symptom and ambition. Acknowledging this gap in the literature, though, it seems that the data so far suggest that high ambition is stably high, independent of symptoms.

Could this emphasis on ambitious goals be a scar from prior experience of mania? Symptoms of mania interfere with accomplishment. Perhaps the emphasis on reaching goals among people with bipolar disorder is merely a consequence of having experienced the devastating impact of episodes on achievement. One way to examine this possibility is to study persons with a vulnerability to hypomanic symptoms who have not yet encountered the social and occupational adverse consequences of manic episodes. The hypomanic personality scale (HPS) was developed to identify persons at-risk for the development of manic symptoms in the future (Eckblad & Chapman, 1986). In a 10-year prospective study, more than 75% of individuals with high scores on the HPS developed manic or hypomanic episodes (Kwapil et al., 2000).

Like individuals with a history of mania, undergraduates with high HPS scores report setting higher goals. To examine lifetime goals, Johnson and Carver (under review) developed the Ambition Survey, which asks individuals the extent to which they hold goals such as making more than 10 million dollars, becoming famous, ruling a country, and having 50 or more lovers. Among 160 undergraduates, vulnerability to hypomania was correlated significantly with high goals on the ambition scale. These findings were replicated in a second sample of over 300 undergraduates. The correlation between vulnerability to hypomania and scores on the ambition scale was not explained by current depression symptoms, lifetime depression symptoms or current hypomanic symptoms. In sum, people who are vulnerable to mania endorse holding higher life ambitions.

Separate from the literature on goal setting and achievement motivation, there is an extensive literature on personality traits in bipolar disorder, particularly extraversion. If achievement striving and extroversion are correlated, one might expect that persons with a history of mania would be high in extroversion. The findings have been inconsistent (see Klein, Durbin, Shankman, & Santiago, 2002, for review). Although many studies have found elevated extroversion levels among people with a history of mania, others have failed to find this pattern. Achievement striving, however, is only one facet within measures of extroversion; indeed, it is not always part of extroversion. On the NEO (Costa & McCrae, 1985), achievement striving is one facet of conscientiousness. Although there have been numerous studies of extroversion and affectivity in bipolar disorder, these studies have not typically examined specific facets, and broader personality studies do not seem to have included specific analyses of achievement striving.

2.4.1. Summary of achievement orientation

Some evidence has emerged to support the idea that an achievement-oriented temperament underlies the higher accomplishments among people with hypomania, as well as family members of people with mania.2 A series of clinicians have described elevated achievement motivation and drive among patients with bipolar disorder and their family members. The small empirical literature indicates that people with bipolar disorder display high ambitions. More specifically, these ambitions are captured on measures of investment in goals and setting high goals. These traits appear stable, regardless of whether manic symptoms are present, and have been documented in samples with clinically diagnosed bipolar disorder as well as samples defined by mild vulnerability to hypomania. The general pattern of the evidence is congruent with the idea that genetic vulnerability to mania could be expressed in higher achievement motivation and goal setting throughout the life course.

There are several gaps in this research, however. Strikingly, there is no research on these traits among unaffected family members of bipolar probands. Given their accomplishments and the clinical observations, one would expect to find higher goal setting and more emphasis on achieving goals in the families of people with bipolar disorder. If so, this would support the intriguing idea that the temperamental qualities that are part of the vulnerability for this devastating disorder also promote adaptive outcomes, such as greater productivity. At times, ambitious goals are necessary for societal accomplishments. As noted by Peven and Shulman (1983), “Perhaps we should give thanks to our ancestor of the ice age who looked around one chilly day and enthusiastically said to his fellows, ‘I know a great place down south. Why don’t we pack up and move down there and get out of this cold?’” (p. 15).

Whether family members display these characteristics or not, it seems that these goal-setting tendencies have adaptive consequences for some people and maladaptive consequences for others. That is, family members seem to accomplish more, as do people with hypomanic symptoms. For people with full-blown bipolar disorder, accomplishments are often thwarted. For most people, valuing goals simply helps accomplish more (Locke & Latham, 2002) and does not promote mania. Something, then, must differentiate the way in which this goal striving plays itself out in people with full-blown manic episodes. Because no studies have compared goal setting in people with full-blown manic episodes, those with hypomania, and those at risk, there is little empirical evidence to address this issue. However, it may be that the nature of goals is more moderated among people with less severe forms of the disorder, and that this allows for more realistic planning and accomplishment.

Despite gaps in our knowledge, it is important to note that these high goals appear to be constant and not shift with mood changes among persons who are vulnerable to mania. Thus, other variables must be involved in the genesis of manic symptoms. What factors differentiate persons for whom these typically beneficial traits are associated with increased risk of manic episodes? What variables might interact with high goal setting to trigger manic episodes?

2.5. Heightened emotional reactivity

Despite the fact that high levels of emotion are part of the symptom definition, it is only recently that anyone started to ask whether people with bipolar disorder are hyperreactive outside episodes. People with bipolar spectrum disorder have been found to report greater variability in their self-report of daily affect even when euthymic (e.g., see Lovejoy & Steuerwald, 1995). In a controlled laboratory experiment, persons with bipolar disorder in remission have been found to react to small failures on anagram tasks with more performance decrement on subsequent tasks than people with no mood disorder (Ruggero, 2003). In another study, those with bipolar spectrum disorders were found to react to a difficult math task with more prolonged cortisol elevations (a sign of emotionality) compared to people with no mood disorder (Goplerud & Depue, 1985).

There is some evidence that people with bipolar disorder are particularly reactive to positive and incentive stimuli as compared to aversive stimuli. Two studies that bear on this issue used the self-report behavioral inhibition/behavioral activation scales (BIS/BAS; Carver & White, 1994) to measure self-report sensitivity to incentive and threat stimuli. Items on the BAS reward responsiveness scale assess the propensity to experience excitement and energy during and after goal attainment. Items on the BIS scale assess the propensity to experience anxiety in response to threat and punishment. Persons with bipolar disorder and those with elevated HPS scores both have significantly higher scores on the reward responsiveness scale than age-matched nondisturbed persons, even during periods of recovery (Meyer, Johnson, & Carver, 1999; Meyer, Johnson, & Winters, 2001). Responsiveness to threat was higher than normative levels only among persons who were experiencing current depression (Meyer et al., 2001). This pattern suggests that high emotional responsiveness to reward in particular is linked to bipolar disorder.

Although the above studies have relied on self-report of emotional responsiveness, there is also evidence of differential psychophysiological reactivity, particularly to positive stimuli. In one study, people with high vulnerability to bipolar disorder (elevated HPS scores) had greater psychophysiological reactivity than other people to positive stimuli (pleasant pictures) but not to aversive stimuli (Sutton & Johnson, 2002). Hence, on both self-report and psychophysiological indices, there is evidence that bipolar disorder is associated with emotional hyperreactivity to positive stimuli.

This emotional reactivity also appears to be predictive of the course of disorder. For example, mood instability between episodes has been found to be a robust predictor of relapse after a life stressor (Aronson & Shukla, 1987). Although this study did not differentiate positive versus negative mood instability and did not differentiate mania from depression, other studies suggest that reactivity to positive stimuli is predictive of the course of manic symptoms. In another study, BAS reward responsiveness predicted increases in manic symptoms over time, but BIS did not (Meyer, Johnson, & Winters, 2001). In a prospective study of life events, scores on an interview-based measure of manic symptoms increased after major life successes but did not change after negative life events (Johnson et al., 2000; Johnson et al., 2003a). Hence, early evidence suggests that positive reactivity is more involved in the course of mania than negative reactivity is.

In sum, mood reactivity appears to be present in mania-vulnerable persons even outside episodes. These patterns have been noted in people at risk for bipolar disorder, as well as those with a history of manic episodes. Even when they are euthymic, people with bipolar disorder appear to experience frequent and intense emotions in response to environmental conditions. These responses may be particularly strong in contexts involving positive and incentive stimuli. Emotional reactivity, and particularly emotional reactivity to positive stimuli, appears to be a predictor of the course of manic symptoms over time.

2.5.1. Cognitive reactions to positive moods and success in bipolar disorder

What else happens when people with a vulnerability to mania experience this emotional reactivity? The valence of ongoing cognition appears closely linked to mood among persons with bipolar disorder. A series of studies have identified cognitive processes that are mood-state dependent in bipolar disorder. One is an increase in accessibility of mood-congruent memories. For example, researchers have documented that during hypomanic states, persons with bipolar disorder experience more than three times as many positive as negative memories (Eich, Macaulay, & Lam, 1997; Weingartner, Miller, & Murphy, 1977), even though they recall an equivalent number of positive and negative memories during depressed states. Although these studies did not include control participants, other studies suggest that during good moods, people remember about 10% more positive memories compared to unpleasant moods (Eich, Macaulay, & Ryan, 1994). That is, the nature of recall appears more mood-state dependent for people with mania than it does for other people. Cognition regarding the self also appears to fluctuate with manic and depressive symptoms. Among people with bipolar disorder, self-esteem has been found to correlate with manic symptoms (Lyon, Startup, & Bentall, 1999) with euphoria in particular (Perugi et al., 2001), and inversely with depressive symptoms (Lyon et al., 1999). Self-esteem appears more mood-state dependent in persons vulnerable to bipolar symptoms than in other persons. That is, among students who are highly vulnerable to mania, daily mood changes had more dramatic implications for reported self-esteem levels than among the students with low vulnerability to mania (Johnson & Ruggero, 2003a). Hence, people with a history of mania appear to experience powerful cognitive changes in response to a given mood change.

An aspect of cognition that appears particularly mood-state dependent is self-efficacy or confidence. The influence of manic symptoms on confidence was observed by the second century AD:

“If mania is associated with joy, the patient may laugh, play, dance night and day, and go to the market crowned as if victor in some contest of skill… The ideas the patients have are infinite… believ[ing] they are experts in astronomy, philosophy, or poetry…” Aretaeus of Cappadocia, as cited in Akiskal, 1996, p. 5S.

Empirical research has supported the relationship between current hypomanic symptoms and confidence. For example, in a study of 464 college students, current hypomanic symptoms correlated with higher expectations of attaining upcoming goals (Meyer, Beevers, & Johnson, 2004).

This particular link–from positive mood to confidence–may be especially important. If emotional hyperresponsiveness to positive outcomes is put together with the close link between positive feelings and confidence, it suggests a sequence in which success results in elevated confidence. Two other studies suggest support for that line of thought, by showing that for people who are vulnerable to bipolar disorder, success expectancies increase dramatically after a success experience. In one study, undergraduates who did and did not report hypomanic symptoms were asked to return for an experiment 6 weeks later in the semester. After sham success feedback, undergraduates with a history of recent hypomanic symptoms were more likely to attribute their success to internal factors and to expect success on the next task than they were in the absence of success feedback; controls did not show these effects (Stern & Berrenberg, 1979). Perhaps most strikingly, the undergraduates with a recent history of hypomanic symptoms reported that they could do well in guessing the results of a coin toss–a chance task–after an initial success. After neutral feedback, in contrast, the groups did not differ on any cognitive measures.

Recently, we replicated and extended these findings (Johnson, Ruggero, & Carver, in press). Among undergraduates, current hypomanic symptoms were associated with higher success expectancies but only after an initial success. This study went one step farther, however. It asked about the consequences of this greater confidence of success. Specifically, after the initial success, students were given a choice of difficulty levels for an upcoming eye–hand task. Students with a vulnerability to hypomanic symptoms chose a more difficult task for themselves than those who were not vulnerable to hypomanic symptoms. Hence, after an initial success, persons with vulnerability to hypomania appear to expect more success, and they also appear more willing to pursue difficult goals.

We found a similar pattern of findings among persons with bipolar I disorder. That is, after a success, persons with bipolar I disorder chose more difficult goals than control participants (Johnson & Ruggero, 2003b).

Setting these higher goals may have important repercussions for the course of disorder. That is, high scores on the NEO achievement-striving scale, including items capturing high investment in goals and newly formed goals, were found to predict increases in manic symptoms over 6 months, but not to predict depressive symptoms (Lozano & Johnson, 2001). Hence, ambitious goal setting appears to predict the course of manic symptoms.

There is also some evidence that people may pursue goals with less regard to consequences as they become more manic. That is, as people experience increases in manic symptoms, they report higher levels of fun seeking (Meyer, Johnson, & Winters, 2001), a scale designed to capture the pursuit of goals without regard to risks or danger (Carver & White, 1994). Similarly, during manic episodes, people with bipolar disorder perform more poorly in recognizing facial negative affect (Lembke & Ketter, 2002). Hence, as symptoms increase, people with bipolar disorder not only may be engaged in goal pursuit, but they may be less aware of danger signs.

An interesting pattern emerges from this group of findings. People who have either a history of mania or a vulnerability to mania appear to be more emotionally reactive, particularly to positive experiences, than other people. This does not seem to be state dependent. That is, even persons with this history who are currently euthymic report an elevated emotional responsiveness to rewards. In contrast, a history of mania or a vulnerability to mania relates only modestly to greater confidence. That is, when the person is asymptomatic and no specific event has taken place, vulnerability either does not correlate with confidence (Johnson & Ruggero, 2003a; Johnson, Ruggero, & Carver, in press; Meyer, Beevers, & Johnson, in press; Stern & Berrenberg, 1979) or correlates only modestly with confidence for future goals (Eckblad & Chapman, 1986; Meyer & Krumm-Merabet, 2003; Ruggero, 2003). Elevations in confidence appear to emerge more strongly after success or in the presence of already existing hypomanic symptoms, symptoms that typically follow from success. Elevated expectancy, then, is largely state dependent. Similarly, a decrease in awareness of danger appears to be state dependent.

To summarize the points made in these sections, people with bipolar disorder seem to experience greater mood reactivity to environmental circumstances than those without bipolar disorder do. This reactivity may be more pronounced for positive stimuli. When they are manic, people with bipolar disorder remember the positive moments in their life much more readily than the negative moments, and they see themselves much more positively than they do at other times. They show large increases in confidence after initial successes or when they are experiencing hypomanic symptoms. After small successes or in the presence of mild hypomanic symptoms, people with bipolar history or vulnerability appear to perceive their life goals and specific tasks as more attainable, they are more likely to tackle difficult tasks, and they are less likely to perceive cues of danger. Interestingly, these processes appear to require a trigger: people with bipolar disorder do not appear to exhibit robustly elevated confidence in their success during euthymic periods in the absence of recent success or positive moods. Hence, success seems to promote greater goal pursuit among persons vulnerable to bipolar disorder. This goal pursuit may help explain the greater risk of manic symptoms after major life successes, described above (Johnson et al., 2000). It does appear that elevated goal pursuit predicts increases in mania over time (Lozano & Johnson, 2001).

It must be acknowledged that each of the phenomena discussed here, including high goal setting, emotional reactivity to successes, and increased optimism after an initial success, occurs in at least a mild form among people with no mood disorder. The national euphoria engendered by stock market increases in the late 1990s is a good example of the universality of overly optimistic responses to good news. Certainly, over-engagement in goal pursuit can be observed in people who do not have bipolar disorder. Even though people with bipolar disorder appear to endorse higher than average levels of goal setting, and during mania, higher confidence, one might expect the distribution of scores to overlap with the general population. Do the constant high goals together with the volatile emotional reactions and confidence after success constitute enough to account for the spiral into mania? Or is something else needed? Basic research suggests that dopaminergic pathways from the nucleus accumbens to the prefrontal cortex are activated when people anticipate reward (Knutson, Adams, Fong, & Hommer, 2001). Bipolar disorder has been hypothesized to be the result of dysregulation in this pathway (Depue, Collins, & Luciana, 1996; Hestenes, 1992). Hence, one might expect people with bipolar disorder to have greater difficulty achieving emotional and behavioral control with challenges to the reward system. Excessive goal pursuit may provide this challenge.

3. Achievement and confidence: an integrative model

Summarizing across clinical observations and research findings, two patterns emerge. First, high goal setting appears to be a stable characteristic among persons with bipolar disorder. Second, unrealistically high success expectancies emerge with symptoms of hypomania and after initial successes. These two patterns suggest a tentative way of thinking about goal regulation in mania, as displayed in Fig. 1. High goal setting alone does not trigger episode onset, as this characteristic appears to be present throughout the life course. Rather, confidence about salient goals seems to fluctuate with manic symptoms. Judgments about the likelihood of success seem only slightly elevated for people with vulnerability to bipolar disorder, until an initial success occurs or hypomanic symptoms arise from some other source. With an initial success or hypomanic symptoms, people with bipolar disorder seem to develop unrealistically high confidence. This unrealistic confidence may fuel excessive behavioral involvement in ever-higher goals, particularly for persons who already had high ambitions at baseline. This excessive behavioral activation and goal pursuit may help explain the increases in manic symptoms after successes (Johnson et al., 2000). In line with this logic, Beck and Weishaar (1995) argued that “overly optimistic expectations provide vast sources of energy and drive the manic individual into continuous goal-directed activity.”

Fig. 1.

A model of goal regulation deficits and mania.

Consider a hypothetical scenario of a person who has always harbored the idea that it would be important and exciting to make a personal contribution to the world, perhaps through a position of political importance. The goal was always there, albeit quiescent. When this person’s mood is stable, he values the goal and imagines it would be exciting if it were possible to attain it. But it feels a little unrealistic and out of reach. Imagine now that this person experiences a small political success, perhaps with a neighborhood or workplace issue. His confidence of success shoots upward to an unrealistic level. Convinced of his ability, he begins a campaign for national political office. His activity level increases, so that he can no longer find time for sufficient sleep. The sleep loss then accelerates the display of manic symptoms more dramatically (Colombo, Benedetti, Barbini, Campori, & Smeraldi, 1999). Mania, then, could be considered the synergistic manifestation of two phenomena: high goals, resolutely pursued due to an unrealistic sense of confidence. Some of these patterns may form a recursive loop, as described by Robert Schumann, who spent the last months of his life in an asylum and is believed to have suffered from bipolar disorder.

And so it is throughout human life—the goal we have attained is no longer a goal, and we yearn, and strive, and aim ever higher and higher, until the eyes close in death, and the storm-tossed body and soul lie slumbering in the grave. Robert Schumann, cited in Jamison (1996, p. 201).

Having defined two key characteristics, high goal setting and unrealistically high success expectancies, it is important to consider how closely tied to specific diagnostic conditions these are. Both characteristics have been documented for people with mild vulnerability to hypomanic symptoms, as well as those with full-blown manic symptoms. That is, these traits appear associated with mild forms of bipolar disorder, consistent with the idea that manic and hypomanic episodes lie on a continuum, sharing key biological and psychological commonalities. It is not clear at this point whether these characteristics are more prominent in bipolar I disorder than they are in bipolar II disorder, or whether different features differentiate bipolar I disorder from bipolar II disorder (Judd et al., 2003).

This paper has focused on goal regulation in regard to mania, setting aside the question of depression. This reflects the belief that separate models of psychosocial vulnerability to depression and mania can be developed (Johnson & Meyer, 2004), congruent with recent findings that the genetic vulnerability to mania and depression are correlated, but separable (McGuffin et al., 2003). The evidence reviewed here suggests that mania, and not unipolar depression, is related to uniquely high emphasis on goal motivation and more robust increases in confidence after success. Certainly, then, it seems reasonable to suggest that mania will be more strongly associated with goal regulation processes than depression will. Nonetheless, some authors have found that deficits in responsivity to reward are associated with depression (Henriques & Davidson, 2000). Among people with bipolar disorder, increases in depression levels appear to suppress reward responsivity on a temporary basis (Meyer, Johnson, & Winters, 2001). Although these findings would suggest that depression would decrease goal accomplishment, others have found that a history of depression is common among highly creative people (Andreasen, 1987). Clearly then, depression may be an important consideration for many aspects of goal regulation. Perhaps most importantly, it must be acknowledged that most people with a history of mania will experience major depressive episodes. Given that it may not be possible to entirely disentangle mania and depression, it is important to consider potential links between goal regulation and depression.

What implications would goal regulation problems have for the depressive side of bipolar disorder? Some have suggested that depression functions as a mechanism to help individuals to disengage from goals that are not achievable (Nesse, 2000). Hence, it seems reasonable to suggest that during periods of depression, people with bipolar disorder may demonstrate less goal pursuit than they would during other times. A more important question, though, may be whether deficits in goal regulation contribute to episodes of bipolar depression. Theorists have suggested that subjective difficulty attaining goals may trigger depression (Carver & Scheier, 1998). Empirical research supports both perfectionism (one version of holding goals too steadfastly; Hewitt, 1996) and difficulty obtaining goals (Abramson, 2000) as risk factors for depression. Certainly, setting highly ambitious goals and perceiving them as central would increase the likelihood of this state, if confidence ever waned. Although the evidence suggests that success inflates confidence in someone who is vulnerable to mania, if that person experiences enough failure, the confidence must return to lower levels, potentially inducing depression. Given these models, there is a need for research on how goal dysregulation in bipolar disorder contributes to the onset and maintenance of depressive symptoms.

Beyond understanding more about the heterogeneity within mood disorders, there are almost no studies available to compare these patterns in bipolar disorder to those seen with other psychopathologies. It would be particularly intriguing to compare bipolar disorder to psychopathologies that may involve deficits in reward sensitivity, such as conduct disorder (Quay, 1993), psychopathy (Newman, Patterson, & Kosson, 1987), or compulsive gambling (McDaniel & Zuckerman, 2003). Of note, researchers studying these conditions have often used quite sophisticated laboratory and psychophysio-logical paradigms, which may be quite appropriate for understanding bipolar disorder. Such studies could help us begin to define which aspects of goal regulation are uniquely disturbed in bipolar disorder compared to other conditions.

4. Future research and implications

Although one can draw a picture from the findings in this field, the current state of the empirical evidence is weak. There are several fundamental needs.

There is a need for epidemiological studies of accomplishment in family members of people with bipolar disorder.

There is a need for studies of premorbid levels of creativity, productivity, and accomplishment among people with bipolar disorder.

Because so many different measures have been used to assess setting high goals, valuing those goals, and feeling positive after achieving goals, there is a need for research to assess which facets of goal-setting are most closely tied to bipolar disorder. In evaluating the specific facets, it would be helpful to examine how independent these goal-setting traits are from positive affectivity (Watson & Clark, 1992), dominance (Mehrabian, 1997), and conceptual over-inclusiveness, and to use measures of achievement motivation that do not rely on self-report.

More detailed specification of relevant parameters will set the stage for examining temperament in family members of bipolar probands, and eventually, for behavioral genetics research on the joint heritability of bipolar disorder and goal-setting traits.

There is a need for research considering the biological correlates of reward and goal pursuit in bipolar disorder, using psychophysiological and functional imaging approaches.

More research is needed on how confidence shifts serve as a trigger of enhanced goal pursuit and whether confidence can be influenced after a success. The literature on expressed emotion suggests that families often experience considerable difficulty giving feedback to people with bipolar disorder; more controlled studies on responses to feedback, though, are needed.

There is a need for studies of culture and bipolar disorder. Although several previous studies have suggested comparable rates of lifetime prevalence of bipolar disorder across countries (Weissman et al., 1996), one might expect the course of disorder to be less pernicious in countries with less emphasis on goals and achievement. Although few studies have examined cross-cultural differences in the course of disorder, clinical reports from China describe lower relapse rates in bipolar disorder, and one study of a rural Indian sample traced an increase in the rate of mania over a 20-year period as SES and materialistic values increased (Nandi, Banerjee, Nandi, & Nandi, 2000). Cultural studies, then, may provide a helpful way to disentangle genetic vulnerability from environmental influences.

In short, the current review suggests strong correspondence across diverse observations. The issue of goal pursuit appears in writings about bipolar disorder from a diverse range of authors. But this review also suggests the need for more research on the nature of goal regulation in bipolar disorder.

4.1. Clinical issues

If excessive goal pursuit is closely tied to the onset of manic symptoms, then this process seems ripe for the development of psychosocial interventions. Such interventions could target the background of high goal setting and the overemphasis on accomplishment at baseline. Intriguingly, some persons with bipolar disorder seem to use goal moderation as a way to cope with early symptoms of mania, even without receiving behavioral interventions (see Lam, Wong, & Sham, 2001). Moreover, behavioral interventions could be developed to help persons monitor their expectations for success and to limit excessive goal pursuit, particularly during early stages of hypomania. Such interventions could help people understand and benefit from the strengths of the disorder but also could provide strategies for testing the accuracy of confidence and the realism of goal setting.

Clinical articles have highlighted the importance of excessive optimism in this disorder (Leahy, 1999). However, the available adjunctive psychosocial treatments for bipolar disorder have not targeted goal regulation. Current interventions appear to be much more promising in reducing levels of depression as opposed to mania (Scott, 2004). The mechanisms involved in protecting against mania have not received much attention, but it appears that currently available interventions improve outcomes for mania largely through fostering increases in medical adherence rather than changes in underlying behavioral mechanisms (Johnson, 2002; Leahy, 2004).

The need for novel treatment approaches that are tailored more specifically to mania is highlighted by the evidence of the severe consequences of this illness, despite important gains in pharmacological and psychological treatments. Bipolar disorder accounts for almost half of the inpatient mental health care costs in this country (Kent, Fogartee, & Yellowless, 1995; Johnson, LoPiccolo, Eisdorfer, & Brickman, 2003), and the rate of completed suicide in bipolar disorder is 12–15 times that of the general population (Angst, Stassen, Clayton, & Angst, 2002). Forming a better model of behavioral risk factors should help provide specific intervention ideas for this disorder.

Psychological and behavioral innovations may also inform understanding of biological mechanisms. For example, better descriptions of this behavioral pattern may help inform about advantages that are conferred by the biological vulnerability to bipolar disorder. Better descriptions may also facilitate an integrative model of how biological treatments work: even among persons with no mood disorder, lithium has been found to quell drive (Jamison, 1996; Judd, 1979). Hopefully, psychological manifestations, such as goal-setting traits and confidence fluctuations, can be integrated with an understanding of biological risk in this disorder.

Footnotes

The author is grateful to Charles S. Carver, Ian Gotlib, Jeanne Tsai, Camilo Ruggero, and Amy Cuellar for their helpful comments throughout the writing process.

Results of this study were limited by the exclusion of probands who did not complete high school and those who had not held a full-time position.

Other traits may also help explain the accomplishment associated with mania. For example, people with bipolar disorder and those who are vulnerable to mania have been found to obtain high scores on measures of conceptual over-inclusiveness (Andreasen & Powers, 1974; Johnson & Feldman, 2003), defined as a tendency to accept a broader range of objects as good exemplars of a category. This trait has been found to correlate with creative output (Andreasen & Powers, 1975; Schooler & Melcher, 1995). Hence, ambitious goal setting could be one of a set of traits that help promote creative accomplishments in patients with a history of mania and their families.

References

- Abramson LY. Optimistic cognitive styles and invulnerability to depression. In: Gillham JE, editor. The science of optimism and hope: Research essays in honor of Martin E. P. Seligman. Philadelphia, PA: Templeton Foundation Press; 2000. pp. 75–98. [Google Scholar]

- Adler A. Problems of neurosis. New York, NY: Harper and Row; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Akiskal HS. The prevalent clinical spectrum of bipolar disorders: Beyond DSM-IV. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1996;16:4S–14S. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199604001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiskal HS, Hirschfeld RMA, Yerevanian BI. The relationship of personality to affective disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1983;40:801–810. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790060099013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, quick reference text revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC. Creativity and mental illness: Prevalence rates in writers and their first-degree relatives. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1987;144:1288–1292. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.10.1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NJ, Powers PS. Overinclusive thinking in mania and schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1974;125:452–456. doi: 10.1192/bjp.125.5.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NJ, Powers PS. Creativity and psychosis: An examination of conceptual style. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1975;32:70–73. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1975.01760190072008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angst F, Stausen HH, Clayton PJ, Angst J. Mortality of patients with mood disorders: Follow-up over 34 to 38 years. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2002;68:167–181. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00377-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronson TA, Shukla S. Life events and relapse in bipolar disorder: The impact of a catastrophic event. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1987;75:571–576. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1987.tb02837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bebbington PE. The epidemiology of affective disorders. In: Bebbington PE, editor. Social psychiatry: Theory, methodology, and practice. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers; 1991. pp. 265–304. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Weishaar ME. Cognitive therapy. In: Corsini RJ, Wedding D, editors. Current psychotherapies. 5. Itasca, IL: Peacock; 1995. pp. 229–261. [Google Scholar]

- Becker J, Altrocchi J. Peer conformity and achievement in female manic-depressives. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1968;73:585–589. doi: 10.1037/h0026605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromet EJ, Jandorf L, Fennig S, Lavelle J, Kovasznay B, Ram R, et al. The Suffolk County Mental Health Project: Demographic, per-morbid and clinical correlates of 6-month outcome. Psychological Medicine. 1996;26:953–962. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700035285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon M, Jones P, Gilvarry C, Rifkin L. Premorbid social functioning in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: Similarities and differences. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154:1544–1550. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.11.1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF. On the self-regulation of behavior. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, White TL. Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: The BIS/BAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:319–333. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MB, Baker G, Cohen RA, Fromm-Reichmann F, Weigert E. An intensive study of twelve cases of manic-depressive psychotics. In: Bullard DM, editor. Psychoanalysis and psychotherapy (selected papers of Frieda Fromm–Reichmann) Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1959. pp. 227–274. [Google Scholar]

- Colombo C, Benedetti F, Barbini B, Campori E, Smeraldi E. Rate of switch from depression into mania after therapeutic sleep deprivation in bipolar depression. Psychiatric Research. 1999;86:267–270. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(99)00036-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coryell W, Endicott J, Keller M, Andreasen N, Grove W, Hirschfeld RMA, et al. Bipolar affective disorder and high achievement: A familial association. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1989;146:983–988. doi: 10.1176/ajp.146.8.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, McCrae RR. The NEO personality inventory manual. Odessa, Fl: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Decina P, Kestenbaum CJ, Farber S, Kron L, Gargan M, Sackeim HA, et al. Clinical and psychological assessment of children of bipolar probands. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1983;140:548–553. doi: 10.1176/ajp.140.5.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLong GR, Aldershof AL. An association of special abilities with juvenile manic-depressive illness. In: Obler LK, Fein D, editors. The exceptional brain: Neuropsychology of talent and special abilities. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1983. pp. 387–395. [Google Scholar]

- Depue RA, Collins PF, Luciana M. A model of neurobiology–environment interaction in developmental psychopathology. In: Lenzenweger MF, Haugaard JJ, editors. Frontiers of developmental psychopathology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996. pp. 44–76. [Google Scholar]

- Dohrenwend BS, Dohrenwend BP. Field studies of social factors in relation to three types of psychological disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1967;72:369–378. doi: 10.1037/h0024853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan AJ. Some comments on the Army General Classification Test. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1947;31:143–149. doi: 10.1037/h0054632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckblad M, Chapman LJ. Development and validation of a scale for hypomanic personality. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1986;95:214–222. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.95.3.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eich E, Macaulay D, Lam RW. Mania, depression, and mood dependent memory. Cognition and Emotion. 1997;11:607–618. [Google Scholar]

- Eich E, Macaulay D, Ryan L. Mood-dependent memory for events of the personal past. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1994;123:201–215. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.123.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faris REL, Dunham HW. Mental disorders in urban areas. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Gershon ES, Liebowitz JH. Sociocultural and demographic correlates of affective disorders in Jerusalem. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:37–50. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson RW. The family background and early life experience of the manic-depressive patient. Psychiatry. 1958;21:71–90. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1958.11023116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilvarry C, Takei N, Russell A, Rushe T, Hemsley D, Murray RM. Premorbid IQ in patients with functional psychosis and their first-degree relatives. Schizophrenia Research. 2000;41:417–429. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00092-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goplerud E, Depue RA. Behavioral response to naturally occurring stress in cyclothymia and dysthymia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1985;94:128–139. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.94.2.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Cohen A. Psychosocial functioning. In: Johnson SL, Leahy RL, editors. Psychological treatment of bipolar disorder. NY, NY: Guilford Press; 2004. pp. 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- Harrow M, Goldberg JF, Grossman LS, Meltzer HY. Outcome in manic disorders: A naturalistic follow-up study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1990;47:665–671. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810190065009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriques JB, Davidson RJ. Decreased responsiveness to reward in depression. Cognition and Emotion. 2000;14:711–724. [Google Scholar]

- Hestenes D. A neural network theory of manic-depressive illness. In: Levine DS, Leven SJ, Samuel J, et al., editors. Motivation, emotion, and goal direction in neural network. Hillsdale, NJ, USA: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1992. pp. 209–257. [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt PL. Perfectionism and depression: Longitudinal assessment of a specific vulnerability hypothesis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1996;105:276–280. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamison KR. Mood disorders and patterns of creativity in British writers and artists. Psychiatry: Journal for the Study of Interpersonal Processes. 1989;52:125–134. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1989.11024436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamison KR. Touched with fire: Manic-depressive illness and the artistic temperament. New York: Free Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL. Some unanswered questions regarding psychosocial treatments for bipolar disorder. In: Bauer Mark, Maj M, Akiskal HS, Lopez-Ibor JJ, Sartorius N., editors. Commentary on psychosocial interventions for bipolar disorder. Bipolar disorder. World Psychiatric Association, Evidence and Experience in Psychiatry. Vol. 5. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley and Sons; 2002. pp. 319–322. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, Carver CS. Goal-setting and vulnerability to bipolar disorder. under review. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, Feldman G. Hypomania, positive affect, and creativity. 2003 Manuscript in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, Kizer A, Ruggero C, Winett C, Goodnick P, Miller I. Life events as predictors of mania and depression. 2003a doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.2.268. Manuscript under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, LoPiccolo C, Eisdorfer C, Brickman A. Disregarding a prior diagnosis of mania predicts higher probability of hospitalization in a managed care setting. 2003b Manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, Meyer B. Psychosocial predictors of symptoms in bipolar disorder. In: Johnson SL, Leahy RL, editors. Psychosocial approaches to bipolar disorder. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2004. pp. 83–107. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, Ruggero C. Self-esteem and bipolar disorder. 2003a Manuscript in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, Ruggero C. Cognitive, behavioral and affective responses to reward: A study of bipolar I disorder. 2003b Manuscript in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, Ruggero C, Carver C. Cognitive, behavioral and affective responses to reward: Links with hypomanic symptoms. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, Sandrow D, Meyer B, Winters R, Miller I, Keitner G, et al. Increases in manic symptoms following life events involving goal-attainment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:721–727. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.109.4.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judd LL. Effect of lithium on mood, cognition, and personality function in normal subjects. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1979;36:860–865. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1979.01780080034010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, Coryell W, Maser J, Rice JA, et al. The comparative clinical phenotype and long term longitudinal episode course of bipolar I and II: A clinical spectrum or distinct disorders? Journal of Affective Disorders. 2003;73:19–32. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00324-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karkowski LM, Kendler KS. An examination of the genetic relationship between bipolar and unipolar illness in an epidemiological sample. Psychiatric Genetics. 1997;7:159–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent S, Fogarty M, Yellowlees P. A review of studies of heavy users of psychiatric services. Psychiatric Services. 1995;46:1247–1253. doi: 10.1176/ps.46.12.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Rubinow DR, Holmes C, Abelson JM, Zhao S. The epidemiology of DSM-III-R bipolar I disorder in a general population survey. Psychological Medicine. 1997;27:1079–1089. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797005333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein DN, Durbin CE, Shankman SA, Santiago NJ. Depression and personality. In: Gotlib IH, Hammen CL, editors. Handbook of depression. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2002. pp. 115–140. [Google Scholar]

- Knutson B, Adams CM, Fong GW, Hommer D. Anticipation of increasing monetary reward selectively recruits nucleus accumbens. Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;21:RC159. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-j0002.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutcher S, Robertson HA, Bird D. Premorbid functioning in adolescent onset bipolar I disorder: A preliminary report from an ongoing study. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1998;51:137–144. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00212-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwapil TR, Miller MB, Zinser MC, Chapman LJ, Chapman J, Eckblad M. A longitudinal study of high scorers on the hypomanic personality scale. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:222–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam D, Wong G, Sham P. Prodromes, coping strategies and course of illness in bipolar affective disorder—a naturalistic study. Psychological Medicine. 2001;31:1397–1402. doi: 10.1017/s003329170100472x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam D, Wright K, Smith N. Dysfunctional assumptions in bipolar disorder. 2002 doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00462-7. Manuscript in preparation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leahy RL. Decision making and mania. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 1999;13:83–105. [Google Scholar]

- Leahy RL. Conclusions. In: Johnson SL, Leahy RL, editors. Psychological treatment of bipolar disorder. NY, NY: Guilford Press; 2004. pp. 305–315. [Google Scholar]

- Lembke A, Ketter TA. Impaired recognition of facial emotion in mania. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:302–304. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.2.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenzi A, Lazzerini F, Marazziti D, Raffaelli S, Rossi G, Cassano GB. Social class and mood disorders: Clinical features. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 1993;28:56–59. doi: 10.1007/BF00802092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Klein DN, Seeley JR. Bipolar disorders in a community sample of older adolescents: Prevalence, phenomenology, comorbidity, and course. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34:454–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Buckley ME, Klein DN. Bipolar disorder in adolescence and young adulthood. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2002;11:461–475. doi: 10.1016/s1056-4993(02)00005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lish JD, Dime-Meenan S, Whybrow PC, Price RA, Hirschfeld RM. The National Depressive and Manic-depressive Association (DMDA) survey of bipolar members. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1994;31:281–294. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(94)90104-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke EA, Latham GP. Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey. American Psychologist. 2002;57:705–717. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.57.9.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy MC, Steuerwald BL. Subsyndromal unipolar and bipolar disorders: Comparisons on positive and negative affect. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1995;104:381–384. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.104.2.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozano BE, Johnson SL. Can personality traits predict increases in manic and depressive symptoms? Journal of Affective Disorders. 2001;63:103–111. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00191-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon HM, Startup M, Bentall RP. Social cognition and the manic defense: Attributions, selective attention, and self-schema in bipolar affective disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1999;108:273–282. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.2.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malzberg B. Mental disease in relation to economic status. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1956;123:257–261. doi: 10.1097/00005053-195603000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Aran A, Vieta E, Colom F, Reinares M, Benabarre A, Gasto C, et al. Cognitive dysfunctions in bipolar disorder: Evidence of neuropsychological disturbances. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 2000;69:2–18. doi: 10.1159/000012361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason CF. Pre-illness intelligence of mental hospital patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1956;20:297–300. doi: 10.1037/h0047921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel SR, Zuckerman M. The relationship of impulsive sensation seeking and gender to interest and participation in gambling activities. Personality and Individual Differences. 2003;35:1385–1400. [Google Scholar]

- McGuffin P, Rijsdijk F, Andrew M, Sham P, Katz R, Cardno A. The heritability of bipolar affective disorder and the genetic relationship to unipolar depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:497–502. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.5.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil TF. Prebirth and postbirth influence on the relationship between creative ability and recorded mental illness. Journal of Personality. 1971;39:391–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1971.tb00050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehrabian A. Analysis of affiliation-related traits in terms of the PAD temperament model. Journal of Psychology. 1997;131:101–117. doi: 10.1080/00223989709603508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]