Abstract

Improved methods are needed for routine, inexpensive monitoring of biomarkers that could facilitate earlier detection and characterization of cancer. Suspended microchannel resonators (SMRs) are highly sensitive, batch-fabricated microcantilevers with embedded microchannels that can directly quantify adsorbed mass via changes in resonant frequency. As in other label-free detection methods, biomolecular measurements in complex media such as serum are challenging due to high background signals from non-specific binding. In this report, we demonstrate that carboxybetaine-derived polymers developed to adsorb directly onto SMR SiO2 surfaces act as ultra-low fouling and functionalizable surface coatings. Coupled with a reference microcantilever, this approach enables detection of activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule (ALCAM), a model cancer biomarker, in undiluted serum with a limit of detection of 10 ng/mL.

Improved methods for quantifying biomarkers in blood are necessary for earlier detection and characterization of cancer, with the ultimate goal of improving treatment1. Traditional detection methods are based on a sandwich configuration in which primary antibodies adsorbed on a surface concentrate a target molecule, a labeled secondary antibody provides specificity, and signal amplification is performed to detect physiologically relevant target concentrations. The classic example, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), is widely used in clinical laboratories. Recent efforts have been directed towards making labeling approaches more sensitive and specific, less reagent-intensive, and easier to perform and multiplex. These include immuno-PCR2, rolling circle amplification3, proximity ligation4, protein chips5, microfluidic arrays6, Luminex7 and biobarcode nanoparticles8.

Label-free approaches are based on direct readout of target presence9 and offer a simple one-step assay that conserves reagents and minimizes fluidic handling. Label-free surface plasmon resonance (SPR)10 and quartz crystal microbalances11 are routinely used for measuring biomolecular binding kinetics, but they are not widely applied to biomolecular detection because they tend to be less sensitive than labeled approaches and are prone to high background noise by nonspecific binding (fouling) from complex mixtures such as serum12. Mass spectroscopy can also be used for biomarker detection13, but high equipment costs limit the potential for routine widespread use.

The ideal label-free sensor would have high sensitivity (comparable to or better than ELISA, 0.1 ng/mL ALCAM limit of detection in a commercial kit14), require little or no sample preparation, enable multiplexed measurements, and be inexpensive to manufacture and use. Several approaches have been recently reported that push the boundaries of each of these characteristics. Vahala and colleagues demonstrated optical microcavities with a 5 aM limit of detection of interleukin-2 in 10% serum15. Lieber and colleagues reported multiplexed detection with silicon nanowires, including prostate specific antigen (PSA) at 0.9 pg/mL in desalted donkey serum16. SPR imaging mode for array-based simultaneous detection of hundreds of targets has been reported17,18 and array-based SPR is currently commercialized19 as a platform for screening drug candidates.

Microcantilevers20-23 are highly sensitive to samples in either purified or simulated media (for example, containing BSA or fibrinogen24). They can be scaled to array formats25, but detection in undiluted serum has only been demonstrated with the “dip and dry” method26 or following mass-label amplification27. Suspended microchannel resonators (SMRs)28 are vacuum-packaged silicon microcantilevers with embedded microchannels of picoliter-scale volume (see Figure 1) whose resonant frequency quantifies the mass of the microcantilever. Adsorption of biomolecules to microchannel surfaces displaces an equivalent volume of running solution. The increased density of the biomolecules relative to the displaced solution (proteins are typically 1.35 g/mL)29 results in a net addition of mass, equivalent to the buoyant mass of the bound biomolecules. This changes the microcantilever resonant frequency in proportion to the amount of bound biomolecules. SMRs are batch fabricated in a commercial MEMS foundry at approximately 200 devices per 6 inch silicon wafer. Suitable scale-up could make the SMR a platform for routine, inexpensive monitoring of cancer biomarkers with extremely low sample volume and preparation requirements.

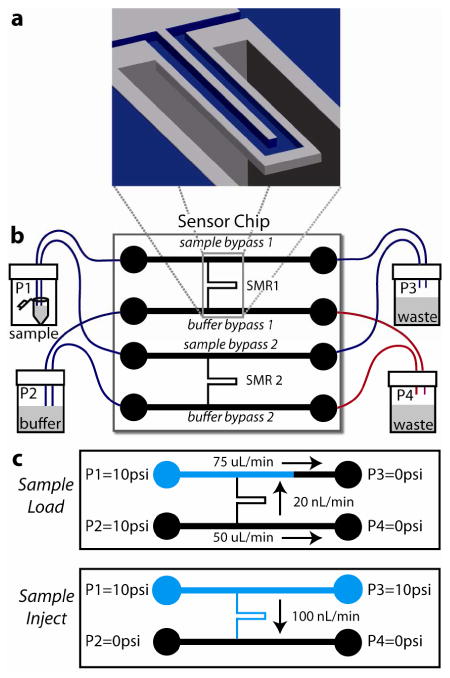

Figure 1.

Suspended microchannel resonator (SMR) system schematic. (a) Cut-away view of SMR microcantilever. The U-shaped sensor channel has a 3 × 8 μm cross section and is embedded in a resonating silicon beam extending 200 μm into a vacuum packaged cavity. (b) Sensor chip with 2 SMRs addressable by bypass channels connected by Teflon tubing to pressure-controlled vials off-chip; one SMR is used as a control (reference) sensor. Blue tubing: ID 225 μm, red tubing: ID 150 μm. (c) Fluid delivery schemes: Sample Load fills sample bypass channels with sample (blue) while the microcantilevers and buffer bypasses are flushed with running buffer (black), Sample Inject delivers a sharp concentration sample to the microcantilevers. Figures not to scale.

We have previously demonstrated28 the detection of immuno-based protein binding within the SMR, however the method reported therein was insufficiently specific for sensing in a complex media. Herein, we report an improved label-free surface binding assay for the SMR which enables picomolar detection of a protein target in serum. These improvements were made possible by using a super-low fouling surface based on zwitterionic polymers and a reference microcantilever. Similar polymers have been used in SPR systems to improve specificity of biomolecular detection in undiluted human serum and plasma30,31. In this report, we demonstrate that these surfaces in SMRs can be used to enable detection of activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule (ALCAM) in undiluted serum with a limit of detection of 10 ng/mL. ALCAM is a 105 kDa glycoprotein identified as a potential biomarker for various carcinomas; it is typically found in blood serum at concentrations ≈84 ng/mL, with levels over 100 ng/mL potentially indicating pancreatic carcinoma32.

Materials and Methods

Suspended Microchannel Resonator

The design and structure of SMRs has been described previously28. Briefly, each SMR chip contains two vacuum packaged microcantilevers of resonant frequency ≈200kHz with embedded U-shaped microchannels of dimensions 3 μm × 8 μm × 200 μm (height × width × length). Each microcantilever is connected on either end to much larger bypass channels (0.03 × 0.1 × 12 mm, height × width × length) to allow fast exchange of samples. For small, evenly distributed changes in microcantilever mass, changes in resonant frequency can be described by eq 1:

| (1) |

where f is the resonant frequency and m is the microcantilever mass. Changes in mass (Δm) result only from the contents of the fluidic channel, which includes both the bulk fluid and molecules which adsorb to the channel surfaces.

SMRs were calibrated by measuring the resonance frequency of microcantilevers filled with solutions of known density, resulting in a coefficient of volumetric density change per frequency change. This is converted to surface mass density change by multiplying by microcantilever volume over surface area. Assuming biomolecular densities of 1.35 g/mL29 and running buffer density 1 g/mL, measured buoyant mass is converted to absolute mass by multiplying by the ratio of biomolecular density over buoyant density (1.35 g/mL over 0.35 g/mL). Experiments in this report were performed on three different SMR chips whose six microcantilevers had calibration coefficients of 46±0.4 (mean ± s.d.) ng/cm2/Hz.

During an experiment, both microcantilever frequencies were measured continuously and independently, to allow implementation of a differential sensing scheme with appropriately functionalized sensing and control microcantilevers. Data was acquired in LabVIEW from two synchronized frequency counters (Agilent 53181A) at 2 Hz sampling rate and analyzed in MATLAB. A water bath maintained chip temperature at 25 °C.

Fluids were delivered to the device from pressurized vials (Wheaton W224611) connected to the fluidic bypasses on the SMR via 225 μm inner diameter PTFE tubing (Upchurch 1689). Computer-controlled valves selected between atmospheric air and regulated N2 gas at 10 psi for each vial. 150 μm inner diameter tubing (red in Figure 1) was used to connect the buffer bypass to waste vials, thus when P1=P2 and P3=P4 (sample loading) fluid enters the microcantilever from the buffer side and prevents sample solution from entering the microcantilever until the pressures are switched for sample injection. To ensure surface reactions were not transport limited, flow velocity in the SMR during sample delivery was large enough to replenish analyte concentration faster than depletion due to binding33. Using conservative assumptions for ALCAM diffusivity (D=10-5 cm2/sec) and antibody-target rate constant (kON = 1.2×106 cm3/sec/mol), the Damköhler number representing the ratio of maximal binding rates over transport flux was calculated to be < 10-2.

Synthesis of DOPA2-pCBMA2

(3,4-dihydroxy-L-phenylalanine)2-(poly-carboxybetaine methacrylate)2 (DOPA2-pCBMA2) was prepared as previously described34 using atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP). Briefly, after synthesizing both the initiator, N,N'-(2-hydroxypropane-1,3-diyl)bis(3-(3,4-bis(tert-butyldimethylsilyloxy)phenyl)-2-(2-bromo-2-methylpropanamido)propanamide), and the CBMA monomer, the ATRP reaction was carried out overnight. The subsequent polymer conjugate was purified by dialysis and dried as a white powder. The tert-butyldimethylsilyloxy protecting groups were removed using 1 M tetrabutylammonium fluoride in tetrahydrofuran (THF), washed with fresh THF, and then dried under reduced pressure. The remaining white powder was aliquoted and stored at -20°C until used.

Surface Cleaning and Functionalization

Because of the inert nature of the tubing and the glass and silicon chips, harsh cleaning solutions such as sulfuric acid may be injected enabling device cleaning and re-use. Devices were cleaned as follows: after 30 min PBS rinse, freshly prepared piranha solution (3:1 mix of H2SO4 and H2O2) was injected from sample and buffer vials, while the chip was heated to 45 °C by an embedded thermoelectric module. After 30 min, channels were rinsed with deionized water (dH2O) until all traces of piranha were removed, as temperature returned to 25 °C. Fresh dH2O was then injected for 60 min, followed by 30 min of ethanol, followed by 20 min of N2 gas. Devices were then typically stored dry overnight. Prior to use, fresh dH2O was injected for 60 minutes and flow rates were checked visually (by counting the rate of drop formation in waste vial tubes) to ensure sensor and control SMRs had similar flow rates. Cleaned devices typically returned to within 1 Hz of pre-experiment frequencies.

For poly(ethyleneglycol) (PEG) fouling tests, poly(L-lysine)-PEG (SuSoS AG, SZ25-46) was reconstituted in PBS at 1 mg/mL and injected for 10 min, resulting in an adsorbed coating as described previously with a similar, biotinylated reagent28. For all other experiments, DOPA2-pCBMA2 was reconstituted in dH2O-HCl (pH 3.0) to a concentration of 2.5 mg/mL and sonicated for 25 minutes. THF was added to cloud point (≈75% additional volume), and the mixture was injected for 20 minutes, followed by 10 min dH2O injection to quantify adsorption (see Figure 2). For antibody functionalization, carboxylate groups of the DOPA2-pCBMA2 surface were activated by injection of a freshly prepared solution of N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) (0.05 M) and N-ethyl-N'-(3-diethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC) (0.2 M) in dH2O for 7 min. NHS/EDC was injected through the buffer bypass so as to activate the microcantilever but not the sample bypass surfaces. The dual bypass design enables this targeted functionalization scheme and prevents target depletion along non-sensing surfaces. Sodium acetate buffer (SA; 10 mM, pH 5.0) was briefly injected to obtain a stable baseline. A solution of antibodies at 50 μg/mL in 1% PBS in dH2O (pH 10.0) was injected for 14 min. The functionalized surface was washed for 10 min with 10mM phosphate buffer containing 0.75 M NaCl, pH 8.2, to remove all noncovalently bound ligands. During the protein immobilization, the residual activated groups of DOPA2-pCBMA2 were deactivated. To quantify the amount of immobilized antibodies, SA buffer was injected again for 5 min. A minimum antibody coverage of 90 ng/cm2 was chosen, and the antibody functionalization procedure (beginning with the NHS/EDC injection) was repeated for experiments whose initial coverage fell below this value. The functionalized surface was then rinsed with PBS for 10 min. Devices filled with stationary PBS were stored for up to 60 min before being used for the experiments shown herein.

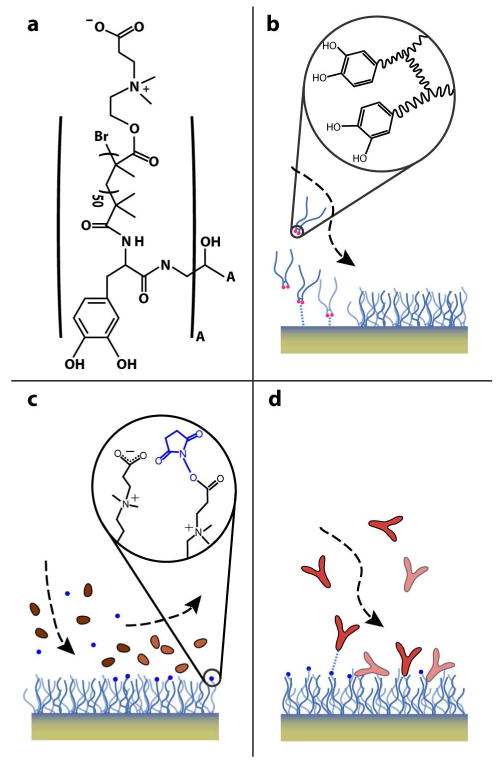

Figure 2.

DOPA2-pCBMA2 adsorption and antibody functionalization schematic. (a) The structure of the DOPA2-pCBMA2 polymer is shown; “A” represents the structure inside the large parentheses, two of which are connected by a R-COH-R bridge. The polymer adsorbs directly onto the thin SiO2 layer of the Si microcantilever surfaces (b), immobilizing a monolayer of 275-360 ng/cm2. (c) Terminal carboxylic acids are transformed to reactive NHS esters by injection of a mixture of NHS and EDC. (d) NHS-esters react with primary amines on IgG antibodies to covalently bind them to the surface.

Sensing antibodies were mouse anti-ALCAM monoclonal IgGs (R&D systems, MAB6561). Control antibodies were whole goat IgG (Abcam, AB37373). Sensing and control microcantilevers were alternated to ensure they would be equivalent.

Measurement of Nonspecific Protein Adsorption and Protein Binding

To test nonspecific protein adsorption, aliquots of fetal bovine serum stored at -20 °C (Sigma Aldrich, F2442) were thawed, centrifuge-filtered (Millipore, UFC30LG25) and injected for 5 min in the sensing microcantilever functionalized with anti-ALCAM IgG. PBS was injected in the identically functionalized control microcantilever. No blocking step was performed.

For protein binding experiments, human recombinant ALCAM/Fc chimera (R&D Systems, 656-AL-100) was reconstituted in PBS with 1 mg/mL BSA and 0.01% Tween-20, then spiked into serum to a final concentration range of 10 to 1,000 ng/mL. Sample solutions were injected for 10 min followed by PBS rinsing. Prior to sample injections, a blocking solution of 1 mg/mL BSA in PBS was injected for 5 min, followed by 10 min injection of blank (pure) serum.

Results and Discussion

DOPA2-pCBMA2 functionalization

We have previously demonstrated28 PEG-based SMR surface coatings for biomolecular detection, a technique useful for quantifying purified targets in solution. In non-purified solutions such as serum, the variability of non-specific binding severely limited biomolecular resolution. Jiang and colleagues have previously demonstrated the ability of zwitterionic polymers containing the carboxybetaine moiety to significantly reduce nonspecific adsorption from 100% human serum and plasma, improving on traditional PEG surfaces30. Briefly, hydration plays a key role in the prevention of non-specific protein binding. Zwitterions effectively shield a surface from biomolecular binding by forming a strong hydration layer via electrostatic interactions, compared to the weaker binding of water to PEG, which is based on hydrogen bonding35. Furthermore, such surface chemistries were shown to obtain the abundant functional groups necessary for efficient immobilization of protein probes such as antibodies. However, attaching these carboxybetaine polymers to sensor surfaces required the use of organic solvents and copper based catalytic systems.

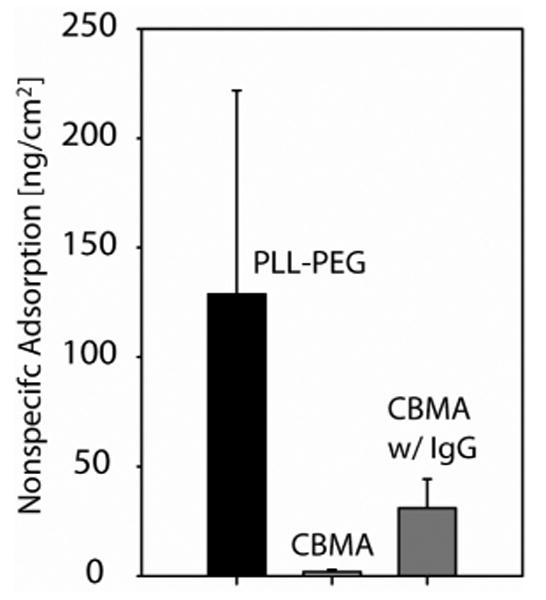

The SMR's SiO2 sensor surface is packaged in a chip and can only be accessed via bypass channels, which limits available reaction conditions and necessitates a different strategy for utilizing carboxybetaine groups. To this end, polymer conjugates based on the adhesive DOPA and pCBMA were created. After first testing these conjugates using an SPR biosensor36, the appropriate environment necessary for adsorption onto SMRs was determined. Addition of THF was found to greatly promote DOPA2-pCBMA2 adsorption, which we suspect is due to a decrease in formation of micelles from the amphipathic polymer as the mixture polarity decreased. Optimized conditions led to monolayer surface coverage of 275-360 ng/cm2, which enabled the direct ALCAM detection in serum by decreasing the background noise due to non-specific protein binding compared to our previous PLL-PEG surface functionalization scheme (see Figure 3). Although a detailed mechanism of adsorption on SiO2 surfaces is not known, Messersmith and colleagues previously demonstrated DOPA terminated polymers to be highly adhesive to TiO2 surfaces37.

Figure 3.

Total nonspecific adsorption after serum injection over PLL-PEG and DOPA2-pCBMA2 surface coatings with and without antibody (IgG) functionalization; n=3, error bar is 1 s.d. Serum incubation time was 5 minutes, followed by surface washing with PBS for 10 min. The adsorbed layer density was assumed to be 1.35 mg/mL.

Antibody Functionalization and ALCAM detection

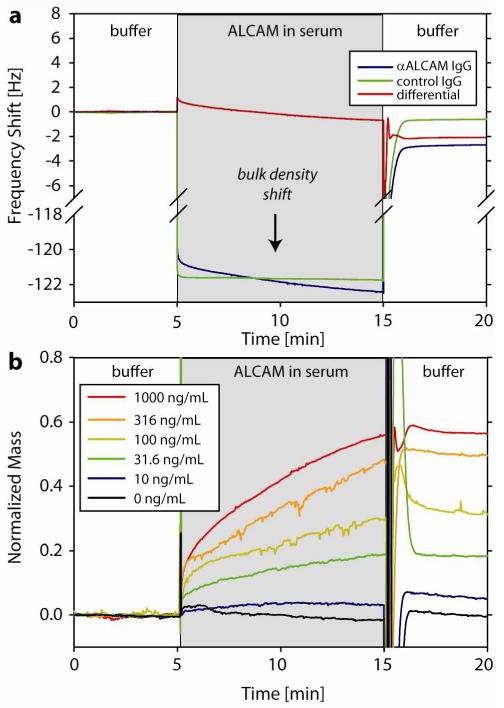

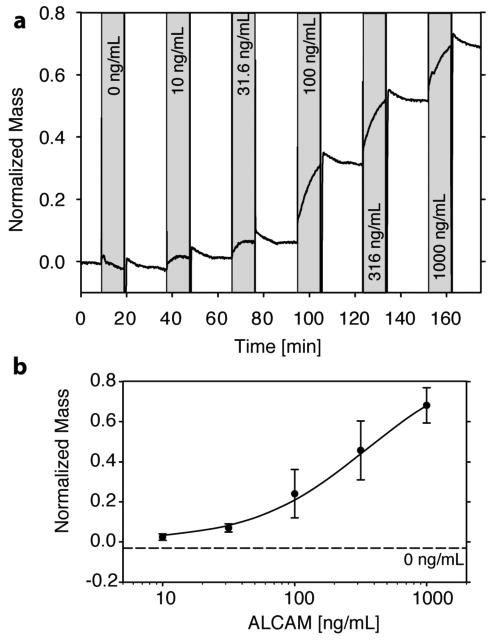

Figure 4 summarizes the dose-response behavior of de novo functionalized DOPA2-pCBMA2 surfaces to varying concentrations of ALCAM in serum. Serum is denser than the PBS buffer by 1.25%, which results in a −121 Hz bulk density shift during the injection (Figure 4a). This shift is not consistent for both microcantilevers due to microcantilever calibrations differing by ≈1% and serum's inhomogeneous density. This leads the differential response during sample injection to be offset by approximately 1 Hz. In Figure 4b, these offsets have been removed for clarity by a MATLAB script that aligns the end of the binding trace during injection with the equilibrium value at the end of the buffer rinse.

Figure 4.

Sensor response to ALCAM-spiked serum on DOPA2-pCBMA2 surfaces functionalized with anti-ALCAM IgG (sensing) and whole goat IgG (control). (a) The mass of specifically bound ALCAM can be quantified by the change in the differential frequency before and after injection of 1,000 ng/mL ALCAM. Serum is denser than the PBS running buffer by 1.25%, which results in a -121 Hz bulk density shift during sample injection for both microcantilevers. (b) Dose-response traces for ALCAM injections on de novo functionalized SMR surfaces. The transition from sample to buffer at t=15 min momentarily exhibits large fluctuations due to non-synchronous rinsing of sensor and control SMRs.

Because the IgG antibody functionalization is performed in situ, surface loading of anti-ALCAM IgG can be quantified for each experiment. The IgG loading was found to vary across the 6 experiments in Figure 4b (101.2 to 211.6 ng/cm2), likely due to the rapid breakdown of activated NHS-esters and sensitivity to small changes in pH during the IgG functionalization reaction. ALCAM binding data is thus presented as normalized mass units which are calculated as the change in signal due to ALCAM divided by the anti-ALCAM IgG coverage [Hz] of that experiment. We assumed that the number of active ALCAM binding sites would be linearly correlated with the level of immobilized anti-ALCAM IgG. This interpretation was supported by the consistent ratio of ALCAM signal at saturating concentrations to IgG loading, 0.68±0.09 (mean ± s.d.). We found no significant correlation between the level of control IgG and ALCAM binding.

To demonstrate repeatability of the dose-response, serial injections of increasing ALCAM concentrations were performed with buffer rinsing but no regeneration of microcantilever surfaces (Figure 5). This approach has the advantages of efficient reagent consumption and shorter experiments38. For an ALCAM concentration of 10 ng/mL, with anti-ALCAM IgG loading of 101.2 ng/cm2, ALCAM loading was 3.9 ng/cm2. These SMR results were similar in specificity and sensitivity to the response with the same anti-ALCAM and ALCAM reagents and a similar carboxybetaine-based surface as measured in a custom-built SPR30.

Figure 5.

Serial injections of increasing ALCAM concentrations allow construction of a dose-response curve with the same SMR surface. (a) Samples were injected for 10 min each (shaded bars) with 18 min PBS rinse between samples. (b) Cumulative binding signals (n=3), error bars ±1 s.d. The mean response to pure serum (negative control) is plotted as a dashed line (s.d. = 0.02). The response for each concentration is calculated relative to the initial baseline after the 18 min PBS rinse. The solid line is a variance weighed fit to the Langmuir equation.

The data presented here illustrates a common disconnect between the sensor technology and the surface chemistry used to develop a bioassay. On one hand the SMR's mass resolution, which is a function of the frequency resolution of the entire system and mass sensitivity of the SMR, is 0.01 ng/cm2 in a 1 Hz bandwidth28. Conservative improvements in microcantilever dimensions such as reducing wall thickness by 33% would result in an order of magnitude improvement in this sensitivity. On the other hand, for an observed mass signal to be indicative of a target concentration, specificity must be adequate as well. An arbitrary but commonly used standard defines the limit of detection as greater than 3 times the standard deviation of the response to negative controls (here, pure serum) injections, found to be 2.6 ng/cm2. This more rigorous standard captures both the variability in nonspecific binding from sensor and control surfaces and the effects of sensor drift from the sample injection and rinsing time, which occurs over time scales of 20 minutes. The 200-fold difference between the SMR limit of detection and the assay limit of detection suggests that further improvements in biomolecular resolution should be pursued in step with improvements in the resolution of the individual sensors.

Conclusions

We have demonstrated that SMRs functionalized with DOPA2-pCBMA2 surfaces combined with a differential sensing scheme can quantify concentrations of ALCAM, a model cancer biomarker, at physiologically relevant concentrations (10 to 1,000 ng/mL) in undiluted mammalian serum. Micromechanical resonators have hitherto been limited to higher concentrations, multiple assay steps and/or targets in purified or artificial solutions. Label-free detection in serum was enabled by the use of a zwitterionic, DOPA2-pCBMA2-functionalized surface which significantly reduced non-specific binding relative to previously reported surfaces. Appropriately functionalized, this surface binds the target molecule, which is detected as a change in resonance frequency proportional to the additional mass of the proteins bound to the sensor surface. SMR signals demonstrate the expected dose-response behavior.

Applicability of this assay to clinical cancer biomarker screening will require further advances in functionalization scheme, device design and multiplexing capabilities. IgG loading variability in the current work was partly accounted for by normalization but would lead to unacceptable uncertainty in a clinical laboratory setting. Differences in non-specific binding between the sample and reference microcantilevers may be reduced by adopting more closely integrated sensing and control SMRs, which could be achieved with a single bypass channel feeding multiple microcantilevers. Increasing the number of resonant channels per chip in both serial and parallel configurations will also increase sensitivity and assay throughput.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the National Cancer Institute contract R01CA119402 and SAIC-Frederick contract 28XS119. M.G.V.M. was supported by the NIH Biotechnology Training Program. N.D.B. was supported by an IGERT fellowship from the University of Washington Center for Nanotechnology.

References

- 1.Hanash SM, Pitteri SJ, Faca VM. Nature. 2008;452:571–579. doi: 10.1038/nature06916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sano T, Smith C, Cantor C. Science. 1992;258:120–122. doi: 10.1126/science.1439758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schweitzer B, Roberts S, Grimwade B, Shao W, Wang M, Fu Q, Shu Q, Laroche I, Zhou Z, Tchernev VT, Christiansen J, Velleca M, Kingsmore SF. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:359–365. doi: 10.1038/nbt0402-359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fredriksson S, Gullberg M, Jarvius J, Olsson C, Pietras K, Gustafsdottir SM, Ostman A, Landegren U. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:473–477. doi: 10.1038/nbt0502-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhu H, Snyder M. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2003;7:55–63. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(02)00005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fan R, Vermesh O, Srivastava A, Yen BKH, Qin L, Ahmad H, Kwong GA, Liu C, Gould J, Hood L, Heath JR. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:1373–1378. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vignali DAA. J Immunol Methods. 2000;243:243–255. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(00)00238-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stoeva SI, Lee J, Smith JE, Rosen ST, Mirkin CA. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:8378–8379. doi: 10.1021/ja0613106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qavi A, Washburn A, Byeon J, Bailey R. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2009;394:121–135. doi: 10.1007/s00216-009-2637-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rich RL, Myszka DG. J Mol Recognit. 2008;21:355–400. doi: 10.1002/jmr.928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Teichroeb J, Forrest J, Jones L, Chan J, Dalton K. J Colloid Interf Sci. 2008;325:157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2008.05.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ligler FS. Anal Chem. 2009;81:519–526. doi: 10.1021/ac8016289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diamandis EP. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2004;3:367–378. doi: 10.1074/mcp.R400007-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vaisocherová H, Faca VM, Taylor AD, Hanash S, Jiang S. Biosens Bioelectron. 2009;24:2143–2148. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Armani AM, Kulkarni RP, Fraser SE, Flagan RC, Vahala KJ. Science. 2007;317:783–787. doi: 10.1126/science.1145002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zheng G, Patolsky F, Cui Y, Wang WU, Lieber CM. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:1294–1301. doi: 10.1038/nbt1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wassaf D, Kuang G, Kopacz K, Wu Q, Nguyen Q, Toews M, Cosic J, Jacques J, Wiltshire S, Lambert J, Pazmany CC, Hogan S, Ladner RC, Nixon AE, Sexton DJ. Anal Biochem. 2006;351:241–253. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2006.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campbell CT, Kim G. Biomaterials. 2007;28:2380–2392. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Säfsten P, Klakamp SL, Drake AW, Karlsson R, Myszka DG. Anal Biochem. 2006;353:181–190. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2006.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gupta A, Akin D, Bashir R. Appl Phys Lett. 2004;84:1976–1978. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li M, Tang HX, Roukes ML. Nat Nano. 2007;2:114–120. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2006.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lang HP, Berger R, Andreoli C, Brugger J, Despont M, Vettiger P, Gerber C, Gimzewski JK, Ramseyer JP, Meyer E, Guntherodt H. Appl Phys Lett. 1998;72:383–385. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen GY, Thundat T, Wachter EA, Warmack RJ. J Appl Phys. 1995;77:3618–3622. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu G, Datar RH, Hansen KM, Thundat T, Cote RJ, Majumdar A. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:856–860. doi: 10.1038/nbt0901-856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yue M, Stachowiak JC, Lin H, Datar R, Cote R, Majumdar A. Nano Letters. 2008;8:520–524. doi: 10.1021/nl072740c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hwang KS, Lee S, Eom K, Lee JH, Lee Y, Park JH, Yoon DS, Kim TS. Biosens Bioelectron. 2007;23:459–465. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Varshney M, Waggoner PS, Tan CP, Aubin K, Montagna RA, Craighead HG. Anal Chem. 2008;80:2141–2148. doi: 10.1021/ac702153p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burg TP, Godin M, Knudsen SM, Shen W, Carlson G, Foster JS, Babcock K, Manalis SR. Nature. 2007;446:1066–1069. doi: 10.1038/nature05741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fischer H, Polikarpov I, Craievich AF. Protein Sci. 2004;13:2825–2828. doi: 10.1110/ps.04688204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vaisocherová H, Yang W, Zhang Z, Cao Z, Cheng G, Piliarik M, Homola J, Jiang S. Anal Chem. 2008;80:7894–7901. doi: 10.1021/ac8015888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang W, Xue H, Li W, Zhang J, Jiang S. Langmuir. 2009;25:11911–11916. doi: 10.1021/la9015788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Faca VM, Song KS, Wang H, Zhang Q, Krasnoselsky AL, Newcomb LF, Plentz RR, Gurumurthy S, Redston MS, Pitteri SJ, Pereira-Faca SR, Ireton RC, Katayama H, Glukhova V, Phanstiel D, Brenner DE, Anderson MA, Misek D, Scholler N, Urban ND, Barnett MJ, Edelstein C, Goodman GE, Thornquist MD, McIntosh MW, DePinho RA, Bardeesy N, Hanash SM. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e123. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Squires TM, Messinger RJ, Manalis SR. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:417–426. doi: 10.1038/nbt1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Z, Zhang M, Chen S, Horbett TA, Ratner BD, Jiang S. Biomaterials. 2008;29:4285–4291. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang Z, Chao T, Chen S, Jiang S. Langmuir. 2006;22:10072–10077. doi: 10.1021/la062175d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gao C, Li G, Xue H, Yang W, Zhang F, Jiang S. Biomaterials, submitted for publication. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dalsin J, Lin L, Tosatti S, Vörös J, Textor M, Messersmith P. Langmuir. 2005;21:640–646. doi: 10.1021/la048626g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abdiche Y, Malashock D, Pinkerton A, Pons J. Anal Biochem. 2008;377:209–217. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2008.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]