Abstract

Epithelial-stromal interactions play a crucial role in normal embryonic development and carcinogenesis of the human breast while the underlying mechanisms of these events remain poorly understood. To address this issue, we constructed a physiologically relevant, three-dimensional (3D) culture surrogate of complex human breast tissue that included a tri-culture system made up of human mammary epithelial cells (MCF10A), human fibroblasts and adipocytes, i.e., the two dominant breast stromal cell types, in a Matrigel™/collagen mixture on porous silk protein scaffolds. The presence of stromal cells inhibited MCF10A cell proliferation and induced both alveolar and ductal morphogenesis and enhanced casein expression. In contrast to the immature polarity exhibited by co-cultures with either fibroblasts or adipocytes, the alveolar structures formed by the tri-cultures exhibited proper polarity similar to that observed in breast tissue in vivo. Only alveolar structures with reverted polarity were observed in MCF10A monocultures. Consistent with their phenotypic appearance, more functional differentiation of epithelial cells was also observed in the tri-cultures, where casein α- and -β mRNA expression was significantly increased. This in vitro tri-culture breast tissue system sustained on silk scaffold effectively represents a more physiologically relevant 3D microenvironment for mammary epithelial cells and stromal cells than either co-cultures or monocultures. This experimental model provides an important first step for bioengineering an informative human breast tissue system, with which to study normal breast morphogenesis and neoplastic transformation.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths for women in the United States [1,2]. Carcinoma development in the breast correlates with a complex set of phenotypic changes in mammary epithelial cells and their associated stroma [3–5]. However, despite increasing evidence of the critical role played by the microenvironment in establishing normal mammary tissue architecture and its aberrant behavior in the initiation and development of cancer [6–9], more accurate explanations of these processes at different levels of biological complexity will benefit from the use of relevant surrogate in vitro model systems for such studies.

Several cell lines have been used in two-dimensional (2D) culture to investigate cellular events in mammary morphogenesis and carcinogenesis because of their homogeneity, ease of genetic modification and scalable expansion for biochemical procedures. However, these stationary 2D cell cultures recapitulate neither tissue architecture nor functions of the mammary epithelium in vivo, and are inadequate for assessing the role of the stroma in physiological development and carcinogenesis of breast tissue [10–12]. Organ culture provides an intact tissue microenvironment [13–15], but difficulties in obtaining specimens and poor viability of the tissues in culture represent major obstacles for its wide adoption as a reliable experimental model. Animal models and in vivo studies are costly and complex with problems of unpredictable characteristics and ethical approval [16–18]. Thus, significant potential exists with tissue engineered three-dimensional (3D) in vitro models, to bridge the gap between what is known from 2D cell culture models and whole-animal systems. Bissell and her colleagues have pioneered 3D gel models to reconstruct normal and malignant breast tissue architecture [10,19–21]. Currently, heterotypic co-cultures of luminal and myoepithelial cells, tumor and fibroblasts/or endothelial cells are available, for the study of cell-cell and cell-ECM interactions [22–25]. However, a lack of increasingly complex and sustainable models, utilizing more than two cell types and extracellular matrix (ECM) closely resembling the tissue in vivo, still persists. This is important as it has been shown that both ECM composition and/or the presence of stromal cells are capable of modulating the epithelial phenotype in 3D culture models [25–27].

Although progress has been made in constructing mammary epithelial cell cultures in vitro by utilizing hydrogel culture systems, such as collagen and/or Matrigel, [19,26,28,29], their spontaneous gel contraction, limited mass transport and rapid degradation after transplantation limit their further applications in the field of breast tissue engineering. Polymer based scaffolds fabricated with various matrix molecules provide a skeletal network in which epithelial cells can be cultured and acinar structure can be maintained [30,31]. However, technical difficulties arise when mimicking the physiological in vivo state such as maintenance of tissue compliance and compatibility of the scaffolds with cells. Construct failure could be a consequence of matrix collapse and the loss of the required oxygen and nutrient transport, leading to necrosis and loss of tissue function. In contrast, silk proteins, naturally occurring degradable fibrous proteins, provide unique mechanical properties, exhibit excellent biocompatibility and present controlled slow degradation [32–35]. These features offer major benefits in the establishment of long-term 3D cultures of breast tissue in vitro as well as for their in vivo transplantation. Based on previous observations using Matrigel plus collagen-I that revealed the role of fibroblasts as mediators of ductal morphogenesis [26], we have developed a model in which human breast epithelial cells were successfully co-cultured with preadipocytes on Matrigel-collagen I on porous silk scaffolds. This model displayed an even more differentiated/complex phenotype [27].

In the present study, we describe a more complex, 3D heterogeneous culture system of breast architecture. The model was generated utilizing porous silk scaffolds by incorporating two types of breast stromal cells, fibroblasts and adipocytes, along with human breast epithelial cells. We hypothesized that the silk-based porous scaffolds supplemented with ECM molecules such as collagen and/or Matrigel would provide a unique microenvironment in which epithelial cells could be stably cultivated with multiple types of stromal cells, mimicking the local tissue niche in vivo. Thus, this strategy would facilitate the generation of tissue-like structures that more closely resemble the in vivo mammary architecture and function. The novel 3D heterogeneous tri-culture model described here was characterized for tissue morphology and function. We showed that epithelial cells were capable of organizing into relevant in vivo breast structures with a more differentiated phenotype and function when cultured in the presence of extracellular matrix and both stromal cell types.

Materials and Methods

Cell maintenance culture and differentiation

MCF10A cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) were cultivated in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM)/F12 supplemented with 0.1 μg/ml cholera toxin, 10 μg/ml insulin, 0.5 μg/ml hydrocortisone, 20 ng/ml human epidermal growth factor (hEGF), 5% horse serum and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (P/S) solution (all from Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Human mammary fibroblasts (HMF, passage 3–6, ScienCell™, Carlsbad, CA) were cultured in low glucose-DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% P/S solution (Invitrogen). Human adipose-derived stem cells (hASCs, P0) were kindly provided by Prof. Jeffrey Gimble (Pennington Biomedical Research Center, LA), and were expanded in DMEM/F12 containing 1.0 g/L glucose, 10% FBS (Invitrogen). After hASCs reached confluence for 1–2 days, an adipocyte differentiation medium (medium I) composed of 3% FBS, 1% P/S, 1 μM insulin (all from Invitrogen), 500 μM isobutylmethylxanthine (IBMX), 1 μM dexamethasone (Dex), 17 μM D-pantothenate acid, 5 μM thiazolidinedione (TZD) and 33 mM biotin (all from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in DMEM/F12 was added to induce their differentiation (designated as day 0–7). After 1-week (i.e. on day 8), the medium was replaced with adipocyte maintenance media II (similar to medium I, but no IBMX or TDZ). Cells were then fed every other day with medium II until they were used for either histology characterization or tri-culture/co-culture experiments. For tri-culture experiments, a combined medium (Table 1) was used, which has been previously tested to assure proper growth and behavior of each type of cells. All cells were incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2.

Aqueous-derived silk scaffold preparation

Three-dimensional (3D) aqueous-derived silk fibroin scaffolds were prepared according to the procedures described in our previous studies [32–35]. Briefly, a 6.5% (w/v) silk fibroin solution was prepared from Bombyx mori silkworm cocoons (kindly supplied by supplied by Tajima Shoji Co, Yokohama, Japan). To form the scaffolds, granular NaCl particles was added to the silk fibroin solution in Teflon cylinder containers (4 g NaCl/2 mL) and allowed to dry for 1–2 days. Then the containers were immersed in water to extract the salt from the porous scaffolds for 2 days. The pore size of the resultant scaffolds was 500–650 μm, as evaluated by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Zeisss ULTRA 55, Solms, Germany). Finally, the scaffolds were cut into discs (5 mm diameter × 2.5 mm thickness) and autoclaved for cell culture experiments. Before cell seeding, the scaffolds were conditioned with the tri-culture or co-culture medium overnight.

Three-dimensional cultures on silk scaffolds

The mixed Matrigel™-collagen gel was prepared using a 1:1 volume ratio of growth factor reduced (GFR)-Matrigel™ and type I rat tail collagen solution (all from BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) keeping the final collagen concentration at 1.0 mg/ml. In tri-culture, MCF10A cells, HMF and pre-differentiated hASCs (on day 9~10) were mixed with the Matrigel™-collagen solution and seeded on the preconditioned silk scaffolds in a 2:1:1 ratio keeping the number of MCF10A cell constant (60,000 cells/scaffold). After gelation at 37°C for 2 hours, the cell-loaded scaffolds were transferred into non-tissue culture treated 12-well plates; the combined medium was added gently to avoid disturbing the scaffolds. Co-cultures and monocultures of MCF10A cells in the same conditions with the same seeding density served as controls (Table 1). All cultures were incubated in a 37°C, 5% CO2 in a 100% humidified incubator for two weeks and the medium was changed every other day.

To distinguish epithelial cells from the stromal cells within the tri-cultures or co-cultures, CellTracker™ DiI and CellTracker™ Green CMFDA (Invitrogen) were applied to label MCF10A cells and stromal cells (including HMF and hASCs) separately as described previously [34]. Briefly, adherent cells at desired confluence were incubated with the pre-warmed medium containing 25 μM CellTracker™ for 30–40 minutes under growth conditions. Then, the dye was replaced with fresh, pre-warmed medium and the cells were incubated for another 30 minutes at 37°C. After washing with PBS two times, the labeled cells were harvested for seeding on silk scaffolds. Morphologic development was observed by either phase contrast microscopy (Zeiss Axiovert S100) or confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM, Leica SP2, Oberkochen, Germany).

Cell viability and proliferation

Cell viability was assessed by calcein-AM/EthD-1 staining (Invitrogen) as described previously [36]. Only live cells with intracellular esterase activity can digest non-fluorescent calcein-AM into fluorescent calcein. Dead or dying cells containing damaged membranes allowed the entrance of EthD-1 to stain the nuclei. Images were captured by a Leica SP2 CLSM. To determine cell proliferation on the 3D silk scaffold, samples were harvested at indicated time points (from day 1 to day 11), and the DNA contents were measured by using PicoGreen DNA Assay following the protocols of the manufacturer (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Samples (n=3 per group in the same experiment, three repeats) were measured by a micro-plate fluorometer (λex=480 nm, λem=530 nm).

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

Scaffolds loaded with cells were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (EM Sciences, Fort Washington, PA) at pH 7.4 for 2–4 hours. After a post-fixation with 2% osmium tetroxide in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (EM Sciences) for 2 h, samples were dehydrated in a series of graded ethanol, and then embedded in Epon 812. Ultrathin (60–90 nm) sections were prepared for ultrastructure evaluation with an EM201 TEM (Philips, USA).

Histology and immuno-fluorescence/immuno-histochemistry staining

Constructs were harvested and fixed in 4% formaldehyde for histological and immuno-fluorescence staining at indicated time points. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and phalloidin-FITC staining (Invitrogen) were conducted as described previously [36]. For morphometric analysis, three experiments for each condition were analyzed and for each experiment, eight to ten arbitrarily chosen fields per section were examined. Images were captured using a Leica microscope. The total number of ductal and alveolar structures was counted per section and the percentage of duct-like structure was expressed as % epithelial structures per total epithelial structure. For immuno-fluorescence staining, briefly, after sequential treatment of antigen retrieval (~95°C for 15 min), permeabilizing and blocking, sections (~5 μm) were incubated with mouse anti-human antibodies as follows: anti-Ki67 (1:80, BD Biosciences), anti-GM130 (1:80, BD Biosciences), anti-sialomucin (1:20, Abcam, Cambridge, MA), anti-casein (1:20, Abcam,), anti-E-cadherin (1:40, Abcam) and anti-collagen IV (1:40, Abcam). Adjacent sections served as negative controls, which were processed according to the same procedures except with incubation with PBS buffer instead of the primary antibodies. FITC or TRITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:100, Sigma) were used as secondary antibodies. For Ki67 staining, a mouse ABC staining kit from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA) was used following the manufacturer’s protocol, and the number of positive staining cells in different microscopic fields (at least 10 microscopic fields per slide, 3 slides per group) was counted under an upright microscope (Olympus BH-2). Human normal breast tissue sections (provided by Tufts Medical Center, Boston, MA) served as positive controls. Either propidium iodide (PI, 5 μg/ml, Invitrogen) or DAPI (2 μg/ml, Research Organics, Cleveland, OH) was used to counter-stain the cell nucleus. Images were captured with a Leica SP2 CLSM.

Real-time RT-PCR analysis

For related gene expression analysis by real time RT-PCR, scaffolds loaded with MCF10A (labeled by DiI CellTracker™) and stromal cells (labeled by CMFDA CellTracker™) were cut into smaller pieces, and all the cells were harvested by multi-treatments with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA solution at 37°C. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS, Tufts Medical Center) was used to sort the different types of cells [MCF10A (DiI, red), stromal cells (CMFDA, green)]. Total RNA was extracted using an RNAeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) following the supplier’s instructions and the concentration was determined by OD260. After reverse transcription using a high-capacity cDNA archive kit (ABI Biosystems, Foster City, CA), real-time PCR was conducted with TaqMan Gene Expression assay kits (Applied Biosystems) to detect transcript levels of casein-α (Hs_00157136) and casein-β (Hs_00914395). The data were analyzed by ABI Prism 7000 Sequence Detection Systems version 1.0 software as described before [30,32]. Relative expression level for each target gene was normalized by the Ct value of human GAPDH (HS_99999905) (2ΔCt formula, Perkin Elmer User Bulletin #2). Each sample was analyzed in triplicate.

Statistical Analysis

All reported values were averaged (n=3 repeats except for specific experiments where explanations are provided) and expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical differences were determined by Student’s two-tailed t test and differences were considered statistically significant at p<0.05.

Results

Proliferation of epithelial cells and/or stromal cells on 3D silk scaffolds

Before defining tri-culture effects on epithelial cells, optimization of a tri-culture medium was conducted in which equal volumes of MCF10A maintenance medium, HMF medium and pre-differentiated hASC medium II were used. On 3D silk scaffolds, the total cell number in each group (monoculture, co-culture and tri-culture groups) increased gradually during 9 days of culture in the defined tri-culture medium (Fig. 1A). Additionally, preliminary studies also revealed that no obvious difference existed between the native medium and the tri-culture medium when the cells were assayed for growth curves by the MTT method in a 2D culture system (data not shown). Thus, we concluded that the tri-culture medium was capable of supporting the growth of the three cell types.

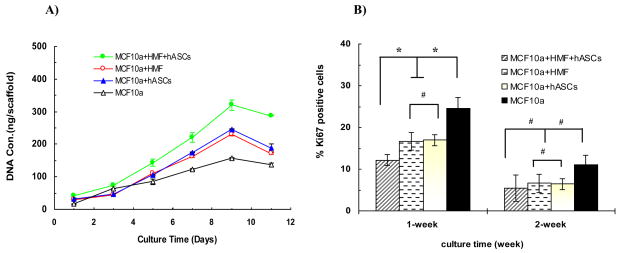

Fig. 1.

(A) DNA quantification analysis by PicoGreen™ DNA assay showed cells proliferating over time in different experimental groups. (B) Quantitative analysis of Ki67+ staining MCF10A cells counted in different microscopic fields. An inhibitory effect of stromal cells on epithelial cell growth was observed in the tri-cultures and co-culture during the first week. A significant difference between tri-culture and co-cultures was observed (*p < 0.05), while no difference exists between the two co-culture groups (#p > 0.05). The percentage of positive staining cells in each group decreased over time.

To determine the effect of stromal cells (HMF or/and adipocytes) on the proliferation of MCF10A cells, Ki67 expression, a marker for cellular proliferation, was assessed by immuno-histochemical staining. After one-week culture on the silk scaffolds, the number of Ki67+ MCF10A cells was lower in both the tri-cultures and the co-cultures than that in the monoculture of MCF10A cells (*p<0.05) (Fig. 1B), which is consistent with our previous study of interactions between epithelial cells and adipocytes, indicating that the stromal cells present in the tri-culture or co-culture system exerted an inhibitory effect on the proliferation of MCF10A cells. No significant difference was noted between the two co-culture groups (#p>0.05). However, the inhibitory effect was enhanced by the addition of more than one type of stromal cells, since a significant difference was observed between the tri-culture group and the co-culture groups (*p<0.05). The percentage of Ki67 positive cells decreased over time in all of the four groups. After two weeks in culture, it seemed that a relatively higher percentage of Ki67+ cells existed in the monoculture group, while this difference did not reach significant statistical level when compared with the other groups.

Growth profiles of epithelial cells on 3D silk scaffolds

Epithelial structures began to organize by day two after seeding on the scaffolds, and by day 5, some alveolar and duct-like structures were formed by MCF10A cells in the tri-cultures. These structures could be identified based on the use of CellTracker™ staining (Fig. 2). With longer time in culture, the number of alveolar structures decreased while the number of duct-like structures increased. Similar growth profiles including acinar and duct-like structures were also observed in the co-cultures with either HMF or adipocytes. However, when compared with the tri-cultures, these same structures appeared approximately one day later in the co-cultures, which reflects a synergistic effect of HMF and hASCs on the morphogenesis of epithelial structures. No obvious difference was observed between the two co-culture groups with respect to the emerging time of the epithelial structures (Fig. 2b–c). In contrast to the tri-culture and co-culture groups, only acinar structures were observed in the monocultures of MCF10A cells, even though the culture time was prolonged past the original two weeks for two additional weeks (Fig. 2 d1-d3), an event that has been reported in our previous studies both in self-standing Matrigel-collagen gels and Matrigel-collagen gels on silk scaffolds [26,34].

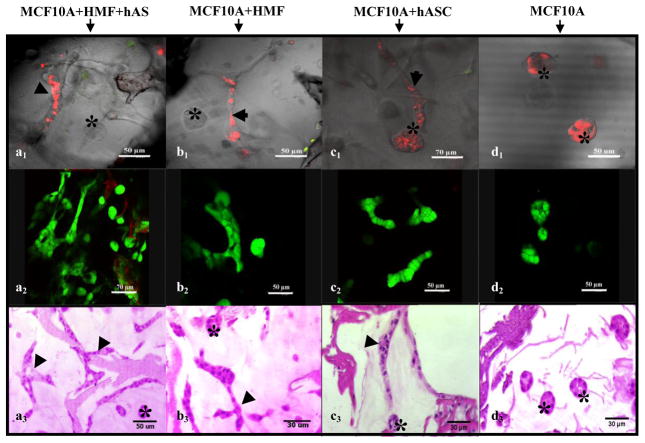

Fig. 2.

Growth profile and viability of MCF10A cells in different cultures developed on silk scaffolds (at day 6). CLSM images showed both alveolar and duct-like structures formed in co-cultures (Top row, a1-c1), while only alveolar structures were observed in the monocultures (d1). (Red, MCF10A cells labeled with Di I™; Green, stromal cells labeled with CMFDA). Viability of MCF10A cells in different groups detected by viability staining (middle row, a2-d2)). H&E staining showed morphological characteristics of the epithelial structures formed by MCF10A cells in different groups (bottom row, a3-d3). (Arrowhead notes duct-like structure, asterisk notes alveolar structure).

Between day 4 and day 10, the size of acinar and duct-like structures in the tri-cultures increased with time when observed under the phase contrast microscope. But after two weeks in culture, it was difficult to observe any structures by phase contrast microscopy due to the poor transparency of the scaffolds. This loss in resolution was likely due to the higher cell numbers and the enriched ECMs secreted by the stromal cells during this time frame. In addition, once the 3D cultures were cultivated for more than three weeks, no typically well-organized epithelial structures were observed by H&E staining (data not shown). It appears that the structures formed earlier begin to merge with each other. This phenomenon is somewhat similar to what we described as happening after 6 weeks when cells were grown in collagen gels [26].

The viability of the cells on silk scaffolds was also evaluated by calcein-AM/EthD-1 staining. After one week in culture, the majority of the cells in each group (tri-culture, co-cultures and monoculture) exhibited good viability (Fig. 2 a2-d2) suggesting that both the silk scaffolds and the culture matrix provided a suitable microenvironment for the growth of the epithelial and stromal cells. This outcome is consistent with our previous study [27], providing further evidence of the potential of the silk scaffolds in bioengineering more complex 3D systems for breast tissue.

Morphological characteristics of the epithelial structures formed on 3D silk scaffolds

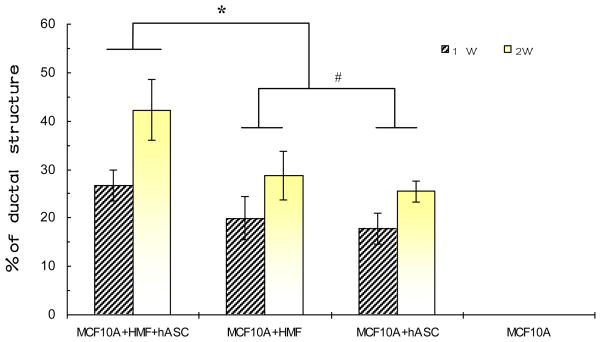

In addition to our observations under phase contrast microscopy, H&E staining revealed detailed morphological characteristics of epithelial cells in each group of cultures. Either in tri-cultures or in co-cultures, MCF10A cells formed both acinar and duct-like structures in the Matrigel™-collagen matrix; in contrast, the same cells exclusively formed alveolar structures in the monocultures (Fig. 2 a3-d3). Compared with the co-cultures, based on counting all the epithelial structures (including both alveolar and duct-like structure) in different microscopic fields (Fig. 3, 10 fields per section, 5 sections/group, randomly selected from 3 different experiments) the percentage of duct-like structures was higher in the tri-cultures,. However, no obvious difference was observed between the two co-culture groups with respect to the percentage of duct-like structures

Fig. 3.

Quantitative analysis of the percentage of duct-like epithelial structures generated by MCF10A cells in the different groups. Compared with the co-cultures, the highest percentage of ductal structures (Nduct/N(acini +duct) ×100%) was found in the tri-culture (*p < 0.05). No significant difference exists between the two co-culture groups (#p > 0.05). The percentage of ductal structures in each group increased over time.

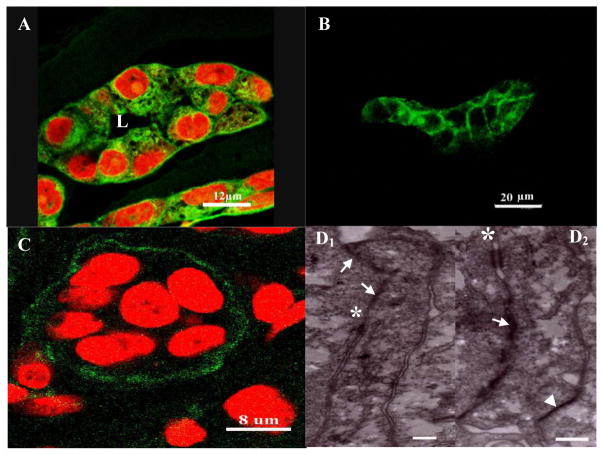

As early as one week of culture, lumena were observed in the center of the acinar structures as evidenced by the phalloidin-FITC labeled actin staining (Fig. 4A). In addition, E-cadherin, a transmembrane glycoprotein that mediates calcium-dependent intercellular adhesion [37], was observed in both acinar and duct-like structures (Fig. 4B). More importantly, ultrastructural analysis using TEM revealed the existence of several junctions such as tight junctions, desmosomes and hemi-desmosomes in the epithelial acini. The basement membrane was also found at the basal side of the alveolar structures as evidenced by anti-collagen IV immunostaining, providing further evidence for the tissue-like integrity of the epithelial structures formed on the 3D silk scaffolds (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Morphological characteristics of the epithelial structures formed by MCF10A cells on silk scaffold: phalloidin-FITC staining (A) showed lumen formation in the alveolar structure. Positive E-cadherin and collagen IV staining indicated the presence of tight junctions and basement membrane and thus the integrity of the tissue-like structures (B). TEM images showed the ultrastructures of epithelial MCF10 cells in the tri-cultures (D1–2). Cell-cell junctions, such as tight junctions (white arrows), desmosomes (white asterisk) and hemi-desmosomes (white arrowhead) were observed (scale bar=300nm).

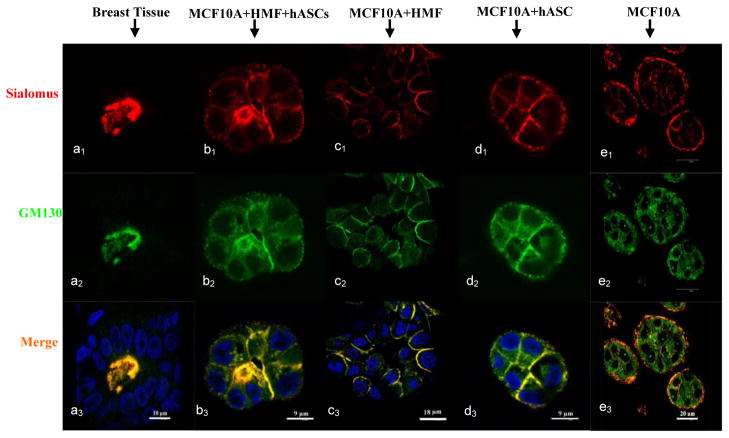

To further characterize the functional polarity of the epithelial structures, the expression pattern of two important markers, GM130, a member of the Golgi family of coiled-coil proteins, and sialomucin, a heavily glycosylated protein produced by epithelial tissues, were evaluated by immunostaining. As shown in Fig. 5(a1-a3), these markers were expressed, as expected, at the apical side of human mammary acini in vivo (positive control). A similar expression pattern was observed in the tri-cultures with both HMFs and adipocytes, where their expression was mostly on the apical side of epithelial cells (Fig. 5b1-b3). In contrast, the expression of GM130 and CD164 in the co-cultures with either HMFs or adipocytes was more enriched on the apical and lateral sides of the MCF10A cells instead of the apical side (Fig. 5d1-d3, 5c1-c3), which is similar to the expression pattern in the co-cultures with pre-differentiated hASCs that we reported previously [27]. This result pointed to the “immaturity” of the alveolar structures formed on the silk scaffolds during co-culture. Interestingly, a reverse polarity was observed in the monoculture group where these two markers adopted a basal location instead of either apical or lateral locations (Fig. 5e1-e3), as reported in our previous study [27].

Fig. 5.

Immunostaining with sialomucin (red) and GM130 (green) showed the polarity of the alveolar structures formed by tri-cultured MCF10A cells on silk scaffold (b1-b3, day 6), which is similar to the positive control of human native breast tissue (a1-a3) in comparison to the co-cultures (c1-c3, d1-d3). The cell nucleus was counter-stained by DAPI (blue). Reversed polarity was also observed in the monoculture (e1-e3, day 6).

Functional differentiation of the epithelial structures formed on silk scaffolds

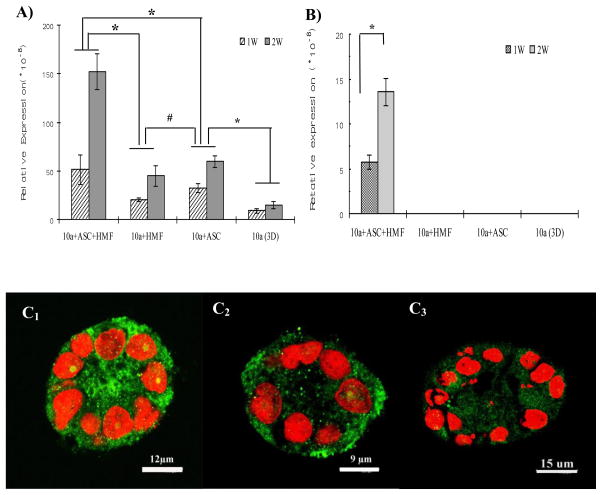

To determine whether the presence of more than one type of stromal cells could enhance the functionality as well as the morphological differentiation of MCF10A cells on silk scaffolds, casein gene expression, a critical indicator for functional differentiation of mammary epithelial cells, was analyzed by real-time RT-PCR. As shown in Fig. 6A, compared with the monocultures, α-casein mRNA level was significantly up-regulated in the tri-cultured and co-cultured MCF10A cells. However, the highest expression level was observed in the tri-cultures when compared with the co-cultures with either HMFs or adipocytes. More importantly, β-casein gene expression was observed only in the tri-cultures in the presence of both HMFs and predifferentiated hASCs, while no β-casein mRNA was detectable in MCF10A cells either in co-culture groups or in monoculture (Fig. 6B). In addition, both α-casein and β-casein expression in the tri-cultures increased with time (α-casein gene expression level in the co-cultures also increased with time), which indicates culture time might be another important parameter to contribute to generating more differentiated epithelial structures on the silk scaffold systems.

Fig 6.

Transcript expression levels of α-casein (A) and β-casein (B) by real-time RT-PCR at the indicated time points. A significant increase in the expression of both α and β-casein was detected in MCF10A cells with both stromal cells. (n=3, *p < 0.05, #p > 0.05). Consistent with the result of RT-PCR, a more intensely stained casein protein was observed in the tri-culture group (C1) in comparison with co-culture group with HMF (C2) and monoculture group (C3) when detected by immunostaining.

Consistent with the mRNA expression level assayed by real-time RT-PCR, a more intensely stained casein protein was observed in the tri-culture group in comparison with either co-culture groups or monoculture group when tested by immunostaining (Fig. 6C1-C3). These data provide further evidence that stromal cells present in tri-cultures contribute to MCF10A cell functional differentiation on the 3D silk scaffolds.

Discussion

Three-dimensional in vitro breast tissue surrogate systems provide a well-defined microenvironment to study morphogenesis and carcinogenesis, in contrast to the conventional 2D culture and the complex host environment of an in vivo model [38]. These 3D tissue systems can also improve our understanding of homeostasis, cellular differentiation and tissue organization. In the studies reported here, a more physiologically relevant, 3D tri-culture model of human breast tissue was developed for the study of normal human breast development. This new tissue system is an extension of our previous work on interactions between MCF10A cells and pre-differentiated adipocytes on silk scaffolds [27], in which human mammary epithelial cells, fibroblasts and pre-differentiated hASCs were cultured on silk scaffolds supplemented with collagen I and GFR Matrigel™. To our knowledge, this study is the first to utilize two types of human mammary stromal cells cultured together with human breast epithelial cells within a silk scaffold and surrounded by ECM, offering significant advantages over previously described less complex models. For example, this system can now be utilized to advance our understanding of how these types of cells sense signals in 3D microenvironments and how these signals are processed to influence mammary epithelium behavior. Moreover, based on our previous studies on silk-based tissue engineering [27,32–35], the porous silk scaffolds used in the tri-culture model not only provided architectural and physical support for the cells, but also conferred variable mechanical properties on this 3D culture model, allowing the study of mechanochemical signaling of epithelial/stroma regulation in vitro. This is important because an abnormal tissue rigidity exhibited by excessive stroma has been shown to actively promote neoplastic transformation of epithelial cells through cytoskeletal tension [39].

To characterize the 3D tri-culture model in vitro, we first evaluated the influence of stromal cells on the proliferation of epithelial cells. A synergistic inhibitory effect of fibroblasts and pre-differentiated hASCs was observed in the 3D tri-culture group, as shown by a lower percentage of Ki67 positive staining MCF10A cells when compared with either the monoculture or the co-culture groups. This inhibitory effect was most likely attributed to the capability of stromal cells to alter the differentiation status of the epithelial cells. This observation is consistent with the more differentiated phenotype exhibited by the tri-cultured or co-cultured MCF10A cells. After a two-week culture, no obvious difference was observed between these culture systems, which might in part be explained by either decreased oxygen transfer within the scaffold during prolonged static culture or the growth arrest of MCF10A cells.

Both alveolar and duct-like structures were generated in the tri-culture and co-cultures; in contrast, when MCF10A cells were cultured alone, only alveolar structures were observed. This result is consistent with our previous findings on self-standing Matrigel-collagen gels [26]. These results indicate that stromal cells promote ductal morphogenesis by epithelial cells. Detailed mechanisms of ductal morphogenesis by the epithelium remain unknown, but controlled migration and invasion of epithelial cells through the stromal ECM are believed to be involved in the ductal branching of the human mammary gland, which is strongly influenced by various ill-defined growth factors, hormones, and adhesion molecules, as well as the complex ECM [23,26,40]. In addition, fibroblasts regulate mammary epithelial branching predominantly through the secretion of soluble factors, such as hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), matrix metallopeptidase 3 (MMP-3), matrix metallopeptidase 2 (MMP-2), insulin-like growth factor (IGF) [40,41]. We also observed that HGF secreted by human pre-differentiated hASCs affected the duct-like structure formation by MCF10A cells in co-cultures [27]. More extensive studies will be needed to fully characterize this phenomenon.

Besides the effect on ductal morphogenesis, differentiated epithelial structures were also observed in the tri-cultures and co-culture as evidenced by the expression pattern of sialomucin and GM130 proteins, as well as a more intensely stained casein protein. However, a more “mature” polarity was exclusively observed in the tri-cultures, where the expression pattern of sialomucin and GM130 mimicked the breast tissue in vivo, when compared with the “immature” polarity exhibited by the co-cultures. This result indicates that either fibroblasts or pre-differentiated hASCs contribute to the appropriate polarity of MCF10A cells in 3D co-culture systems; moreover, once they were incorporated within a same 3-D system, a synergistic effect on the extent of the epithelium polarization was generated.

Cell polarization is a critical feature of mammary glandular epithelium in vivo, and thus it has become an important parameter to evaluate an experimental epithelial model in vitro. Loss of epithelial cell polarity has been correlated with increased cell proliferation and carcinogenesis [42]. However, how polarity is generated and maintained has not been fully elucidated. A number of studies suggest that adhesion mediated through either cell-cell or cell-ECM interactions, is important in controlling epithelial polarity. Polarity is thought to be triggered by extrinsic cues (namely cell-cell and cell-ECM adhesion) leading to asymmetry in the membranes at the site of the cue, and this signaling is then transmitted throughout the rest of the cells [43]. These “symmetry-breaking” adhesive cues could involve any member of the cellular junction complexes (tight junction, desmosomes, hemidesmosomes) and even laminin-1 which was identified as an essential determinant of mammary acini polarity [44]. Inside-out polarity formed in collagen gel- embedded human primary mammary epithelial cells could be corrected by either laminin-1 addition or normal myoepithelial cell (secreting laminin-1) co-culture. In the present study, an inside-out polarity observed in the monoculture of MCF10A cells might be explained by (1) impaired cell junction formation, or (2) insufficient laminin-1 in the culture matrix or (3) less capability of laminin-1 synthesis by MCF10A cells in the monoculture. Tri-cultures or co-cultures with stromal cells completely or partly reversed the polarity. Thus, we speculate that the specific microenvironment provided by the mammary stromal cells not only promote cell junction formation by MCF10A cells, but also enhance their capability of producing more laminin-1. This further points to the potential of stromal cells to generate more differentiated epithelial structures.

Consistent with the more differentiated phenotype exhibited by epithelial cells in tri-culture, a higher expression of casein transcripts was also induced in the tri-cultured MCF10A cells when compared with those cultures under co-culture or monoculture condition. This observation confirms a report where casein and lipid accumulation were enhanced significantly when co-culturing rat mammary epithelial organoids with adipocytes [45] which highlights the critical role of stromal cells in regulating the functionality of mammary epithelial cells. In addition, a synergistic effect of the stromal cells (both HMF and hASCs) on the functionality of epithelial cells was also observed, as evidenced by the fact that β-casein gene expression was exclusively detected in the tri-culture group. This synergistic effect might in part be explained by the unique microenvironment constructed by more than one type of stromal cell, as well as the epithelial cells embedded within the ECM on the 3D silk scaffolds. It has been demonstrated that milk proteins, especially β-casein regulation in mammary epithelial cells was dependent on the surrounding culture microenvironment. Little or no β-casein mRNA was detected in casein gene-transfected mouse mammary epithelial cells grown on plastic pedri dish for 6 days, even in the presence of lactogenic hormones, while significantly higher β-casein expression level was observed when the same cells were cultured in the 3D reconstituted basement membrane (RBM) matrix [46]. Our current study is somewhat consistent with their conclusions, further demonstrating the influence of culture microenvironment on epithelial cells behaviors. While in contrast to the higher β-casein expression displayed by the RMB-embedded epithelial cells in Schmidhauser et al’s report, here, little or no expression of β-casein mRNA was detected in either 3D monoculture or co-culture groups. This discrepancy could in part be explained by some distinct biological properties between MCF10A cell line and those gene-transfected primary mouse epithelial cells utilized by Schmidhauser’s study. For example, increased passage number of MCF10A cells leads to a decreased functional activity when comparing with those primary epithelial cells in vitro. Thus, to further optimize the current 3D tri-culture model in vitro, primary human mammary epithelial cells will be explored in our future study.

Conclusion

A complex 3D human tissue culture system is described in which human breast epithelial cells were cultured with two types of predominant mammary stromal cells (human fibroblasts and adipocytes) on silk scaffolds and displayed more differentiated morphological phenotype and functional activity. This in vitro tri-culture model can be utilized to address several important issues in breast biology, including the role of cell-cell and cell-substrate interactions in regulating the response of breast epithelium to ovarian hormones, the induction of specific protein synthesis (caseins), as well as neoplastic transformation.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the significant technical contributions by Carmen Preda. This work was supported by Phillip Morris International (CS) and the NIH P41 (EB002520) Tissue Engineering Resource Center (TERC). We thank Prof. Jeff Gimble, Pennington Research Center, for the contribution of the hASCs.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mettlin C. Global breast cancer mortality statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 1999;49:138–144. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.49.3.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomsen A, Kolesar JM. Chemoprevention of breast cancer. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65:2221–2228. doi: 10.2146/ajhp070663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howlett AR, Bissell MJ. The influence of tissue microenvironment (stroma and extracellular matrix) on the development and function of mammary epithelium. Epithelial Cell Biol. 1993;2:79–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haslam SZ, Woodward TL. Reciprocal regulation of extracellular matrix proteins and ovarian steroid activity in the mammary gland. Breast Cancer Res. 2001;3:365–372. doi: 10.1186/bcr324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cunha GR, Cooke PS, Kurita T. Role of stromal-epithelial interactions in hormonal responses. Arch Histol Cytol. 2004;67:417–434. doi: 10.1679/aohc.67.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moinfar F, Man YG, Arnould L, Bratthauer GL, Ratschek M, Tavassoli FA. Concurrent and independent genetic alterations in the stromal and epithelial cells of mammary carcinoma: implications for tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2562–2566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schor SL, Schor AM. Phenotypic and genetic alterations in mammary stroma: implications for tumour progression. Breast Cancer Res. 2001;3:373–379. doi: 10.1186/bcr325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haslam SZ, Woodward TL. Host microenvironment in breast cancer development: epithelial-cell-stromal-cell interactions and steroid hormone action in normal and cancerous mammary gland. Breast Cancer Res. 2003;5:208–215. doi: 10.1186/bcr615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maffini MV, Soto AM, Calabro JM, Ucci AA, Sonnenschein C. The stroma as a crucial target in rat mammary gland carcinogenesis. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:1495–1502. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bissell MJ, Rizki A, Mian IS. Tissue architecture: the ultimate regulator of breast epithelial function. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:753–762. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2003.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pickl M, Ries CH. Comparison of 3D and 2D tumor models reveals enhanced HER2 activation in 3D associated with an increased response to trastuzumab. Oncogene. 2009;28:461–468. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim BW, Lee ER, Min HM, Jeong HS, Ahn JY, Kim JH, Choi HY, Choi H, Kim EY, Park SP, Cho SG. Sustained ERK activation is involved in the kaempferol-induced apoptosis of breast cancer cells and is more evident under 3-D culture condition. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7:1080–1089. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.7.6164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eigeliene N, Härkönen P, Erkkola R. Effect of estradiol and medroxyprogesterone acetate on morphology, proliferation and apoptosis of human breast tissue in organ cultures. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:246–259. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mehta R, Lansky EP. Breast cancer chemopreventive properties of pomegranate (Punica granatum) fruit extracts in a mouse mammary organ culture. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2004;13:345–348. doi: 10.1097/01.cej.0000136571.70998.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li AP, Bode C, Sakai Y. A novel in vitro system, the integrated discrete multiple organ cell culture (IdMOC) system, for the evaluation of human drug toxicity: comparative cytotoxicity of tamoxifen towards normal human cells from five major organs and MCF-7 adenocarcinoma breast cancer cells. Chem Biol Interact. 2004;150:129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2004.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malewicz B, Wang Z, Jiang C, Guo J, Cleary MP, Grande JP, Lü J. Enhancement of mammary carcinogenesis in two rodent models by silymarin dietary supplements. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:1739–1747. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Provenzano PP, Inman DR, Eliceiri KW, Beggs HE, Keely PJ. Mammary epithelial-specific disruption of focal adhesion kinase retards tumor formation and metastasis in a transgenic mouse model of human breast cancer. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:1551–1565. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gusterson BA, Williams J, Bunnage H, O’Hare MJ, Dubois JD. Human breast epithelium transplanted into nude mice: Proliferation and milk protein production in response to pregnancy. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1984;404:325–333. doi: 10.1007/BF00694897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barcellos-Hoff MH, Aggeler J, Ram TG, Bissell MJ. Functional differentiation and alveolar morphogenesis of primary mammary cultures on reconstituted basement membrane. Development. 1989;105:223–235. doi: 10.1242/dev.105.2.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roskelley CD, Desprez PY, Bissell MJ. Extracellular matrix-dependent tissue-specific gene expression in mammary epithelial cells requires both physical and biochemical signal transduction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:12378–12382. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nelson CM, Bissell MJ. Modeling dynamic reciprocity: Engineering three-dimensional culture models of breast architecture, function, and neoplastic transformation. Seminar in Cancer Biology. 2005;15:342–352. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olumi AF, Grossfeld GD, Hayward SW, Carroll PR, Tlsty TD, Cunha GR. Carcinoma-associated fibroblasts direct tumour progression of initiated human prostatic epithelium. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5002–5011. doi: 10.1186/bcr138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Darcy KM, Zangani D, Shea-Eaton W, Shoemaker SF, Lee PP, Mead LH, Mudipalli A, Megan R, Ip MM. Mammary fibroblasts stimulate growth, alveolar morphogenesis, and differentiation of normal rat mammary epithelial cells. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2000;36:578–592. doi: 10.1007/BF02577526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shekhar MP, Werdell J, Tait L. Interaction with endothelial cells is prerequisite for branching ductal-alveolar morphogenesis and hyperplasia of preneoplastic human breast epithelial cells: regulation by estrogen. Cancer Res. 2000;60:439–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Proia DA, Kuperwasser C. Reconstruction of human mammary tissue in a mouse model. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:206–214. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krause S, Maffini MV, Soto AM, Sonnenschein C. A novel 3D in vitro culture model to study stromal-epithelial interactions in the mammary gland. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2008;14:261–271. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2008.0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang XL, Zhang XH, Sun L, Subramanian B, Maffini MV, Soto AM, Sonnenschein C, Kaplan DL. Preadipocytes stimulate ductal morphogenesis and functional differentiation of human mammary epithelial cells in 3D silk scaffolds. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:3087–3098. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Debnath J, Muthuswamy SK, Brugge JS. Morphogenesis and oncogenesis of MCF-10A mammary epithelial acini grown in three-dimensional basement membrane cultures. Method. 2003;30:256–268. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(03)00032-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wozniak MA, Keely PJ. Use of three-dimensional collagen gels to study mechanotransuction in T47D breast epithelial cells. Biol Proced Online. 2005;7:144–161. doi: 10.1251/bpo112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dhiman HK, Ray AR, Panda AK. Characterization and evaluation of chitosan matrix for in vitro growth of MCF-7 breast cancer cell lines. Biomaterials. 2004;25:5147–5154. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sahoo SK, Panda AK, Labhasetwar V. Characterization of porous PLGA/PLA microparticles as a scaffold for three dimensional growth of breast cancer cells. Biomacromolecules. 2005;6:1132–1139. doi: 10.1021/bm0492632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Y, Kim HJ, Vunjak-Novakovic G, Kaplan DL. Stem cell-based tissue engineering with silk biomaterials. Biomaterials. 2006;27:6064–6082. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hofmann S, Knecht S, Langer R, Kaplan DL, Vunjak-Novakovic G, Merkle HP, Meinel L. Cartilage-like tissue engineering using silk scaffolds and mesenchymal stem cells. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:2729–2738. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mauney JR, Nguyen T, Gillen K, Kirker-Head C, Gimble JM, Kaplan DL. Engineering adipose-like tissue in vitro and in vivo utilizing human bone marrow and adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells with silk fibroin 3D scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2007;28:5280–5290. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Soffer L, Wang X, Zhang X, Kluge J, Dorfmann L, Kaplan DL, Leisk G. Silk-based electrospun tubular scaffolds for tissue-engineered vascular grafts. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2008;19:653–664. doi: 10.1163/156856208784089607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang X, Wang W, Ma J, Guo X, Ma X. Proliferation and differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells in APA microcapsule: A model for studying the interaction between stem cells and their niche. Biotechnol Prog. 2006;22:791–800. doi: 10.1021/bp050386n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gumbiner BM. Regulation of cadherin adhesive activity. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:399–404. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.3.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim JB, Stein R, O’Hare MJ. Three-dimensional in vitro tissue models of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2004;85:281–291. doi: 10.1023/B:BREA.0000025418.88785.2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bergstraesser LM, Weitzman SA. Culture of normal and malignant primary epithelial cell in a physiological manner simulates in vivo patterns and allows discrimination of cell type. Cancer Res. 1993;53:2644–2654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parrinello S, Coppe JP, Krtolica A, Campisi J. Stromal-epithelial interactions in aging and cancer: senescent fibroblasts alter epithelial cell differentiation. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:485–496. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Soriano JV, Pepper MS, Nakamura T, Orci L, Montesano R. Hepatocyte growth factor stimulates extensive development of branching duct-like structures by cloned mammary gland epithelial cells. J Cell Sci. 1995;108:413–430. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.2.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paszek MJ, Weaver VM. The tension mounts: Mechanics meets morphogenesis and malignancy. J of Mammary gland Biology and Neoplasia. 2004;9:325–342. doi: 10.1007/s10911-004-1404-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yeaman C, Grinidstaff KK, Nelson WJ. New perspective on mechanisms involved in generating epithelial cell polarity. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:73–98. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gudjonsson T, R⊘nnov-Jessen L, Villadsen R, Rank F, Bissell MJ, Petersen OW. Normal and tumor-derived myoepithelial cells differ in their ability to interact with luminal breast epithelial cells for polarity and basement membrane deposition. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:39–50. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.1.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zangani D, Darcy KM, Shoemaker S, Ip MM. Adipocyte-epithelial interactions regulate the in vitro development of normal mammary epithelial cells. Exp Cell Res. 1999;247:399–409. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schmidhauser C, Bissell MJ, Myers CA, Casperson GF. Extracellular matrix and hormones transcriptionally regulate bovine 18-casein 5′ sequences in stably transfected mouse mammary cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1990;87:9118–122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.23.9118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]