Summary

Vertebrates sequester iron from invading pathogens, and conversely, pathogens express a variety of factors to steal iron from the host. Recent work has demonstrated that in addition to iron, vertebrates sequester zinc and manganese both intracellularly and extracellularly to protect against infection. Intracellularly, vertebrates utilize the ZIP/ZnT families of transporters to manipulate zinc levels, as well as Nramp1 to manipulate manganese levels, respectively. Extracellularly, the S100 protein calprotectin sequesters manganese and potentially zinc to inhibit microbial growth. To circumvent these defenses, bacteria possess high affinity transporters to import specific nutrient metals. Limiting the availability of zinc and manganese as a mechanism to defend against infection expands the spectrum of nutritional immunity and further establishes metal sequestration as a key defense against microbial invaders.

Introduction

Transition metals such as iron, zinc, manganese, and copper have numerous biological roles as both structural and catalytic cofactors for proteins and therefore these metals are essential for life [1]. The importance of transition metals to cellular physiology is underscored by analyses of protein databases, which suggest that approximately 30% of all proteins interact with a metal cofactor [2,3]. In keeping with the strict requirement for metals in a variety of cellular processes, transition metals are essential for proper vertebrate immune function [4]. Transition metals are also critical for microbial invaders, as bacterial pathogens must acquire nutrient metal in order to cause disease. The strict requirement for these elements during pathogenesis is due to their involvement in numerous processes ranging from bacterial metabolism to accessory virulence factor function [3]. Vertebrates exploit the bacterial requirement for transition metals by sequestering these elements, a concept termed nutritional immunity [5]. This review will focus on recent advances in our understanding of nutritional immunity with an emphasis on the host factors that sequester these elements from invading pathogens.

The most well studied example of nutritional immunity is sequestration of iron by the vertebrate host. Numerous host and bacterial factors have been characterized that are critical for the struggle for iron between host and pathogen. It is clear that the outcome of this competition influences the result of infection, and this topic has been reviewed elsewhere [5,6]. This review will focus on the struggle for non-iron transition metals during infection, a topic that has recently received considerable attention. Specifically, we will discuss recent evidence suggesting that transition metal sequestration by the host extends beyond iron, and includes manganese and zinc. Furthermore, we will examine the intersection between transition metal availability and bacterial pathogenesis, discussing mechanisms employed by bacteria to overcome nutritional immunity.

The struggle for zinc

Zinc is the second most abundant transition metal within the vertebrate host and has been suggested to interact with as many as 10% of host proteins [7]. Tissue levels of zinc range from 0.8 μg/g in serum, to between 100 and 200 μg/g in spleen, liver, and kidney [8,9]. In vertebrates, zinc functions as a protein cofactor and can have both catalytic and structural roles. Zinc is critically important for proper immune function as even a mild zinc insufficiency results in widespread defects in both innate and adaptive immunity [4]. Despite the fact that chronic zinc deficiency results in pleiotropic effects on the immune system, there is increasing evidence suggesting that the host actively sequesters zinc during infection to hinder microbial growth.

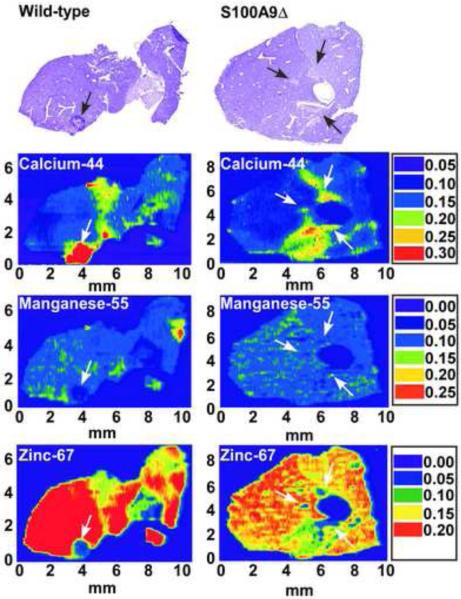

An appreciation that zinc sequestration occurs upon microbial infection resulted from technical advances that permit imaging of metal distribution within vertebrate tissue sections. Laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) produces a two-dimensional image of metal distribution within tissue sections, and can be used to monitor the impact of infection on elemental localization. LA-ICP-MS revealed that tissue abscesses caused by Staphylococcus aureus are virtually devoid of detectable zinc. This is in contrast to the high levels of zinc in surrounding healthy tissue (Figure 1) [10]. Although the factors responsible for sequestering zinc within abscesses are unknown, the lack of nutrient zinc within the abscess appears to represent an immune strategy to control infection.

Figure 1. Zinc and manganese are found at reduced levels at localized sites of infection as compared to surrounding healthy tissues.

Laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) of S. aureus infected organs from wild-type and calprotectin-deficient mice. Top panel shows hematoxylin-eosin stains of S. aureus infected livers. Bottom panels show LA-ICP-MS analysis maps for Ca2+ (calcium-44), Mn2+ (manganese-55), and Zn2+ (zinc-67). Arrows denote the site of abscesses. Scales are presented in arbitrary units. Adapted from Corbin et. al. [10]

In addition to extracellular zinc sequestration, infected vertebrates can also decrease cellular zinc concentrations to protect against intracellular pathogens. Phagocytic and antigen presenting cells of the immune system engulf bacteria into phagosomes, which subsequently merge with lysosomes subjecting engulfed bacteria to an onslaught of antimicrobial factors. ZIP8, which belongs to the Zrt Irt protein family of zinc transporters, is expressed by macrophages and IFN-γ stimulated T cells [11,12]. In stimulated T cells ZIP8 associates with the lysosomal protein Lamp1 suggesting an association with the lysosome [12]. In transfected human embryonic kidney cells ZIP8 also associated with lysosomes [11]. Initial studies have suggested that ZIP8 transports zinc, consistent with its assignment as a Zrt Irt family member [11]. In support of this, T cells decrease lysosomal zinc levels upon activation and cells over-expressing ZIP8 have increased cytosolic zinc levels [11,12]. Taken together, these results are consistent with a model whereby ZIP8 is oriented to transport zinc from the lysosome into the cytoplasm as a mechanism to disrupt zinc-dependent bacterial processes.

In addition to decreasing lysosomal zinc levels, vertebrates also reduce cytoplasmic zinc levels in response to bacterial infection. Stimulation of dendritic cells with lipopolysacharide results in decreased expression of ZIP importers and increased expression of ZnT zinc exporters, resulting in reduced cytosolic zinc levels [13,14]. While it is clear that vertebrates alter lysosomal and cytoplasmic zinc levels in response to bacterial pathogens, it is unclear if this response directly impacts the offending organisms. Alterations in zinc concentrations impacts T-cell development as well as dendritic cell activation and maturation, [4,12-14] making it difficult to determine the impact of reduced zinc levels on microbial growth and virulence. Additional studies are needed to untangle the multiple effects of altered zinc levels during bacterial infection.

While the mechanisms and function of zinc sequestration by the host are unclear, shortages in available zinc clearly have the potential to disrupt a number of bacterial processes that are critical to infection. Bacteria are predicted to incorporate zinc into approximately 4–6% of all proteins [15]. Zinc is utilized to control bacterial gene expression, for general cellular metabolism, and as a cofactor of virulence factors. Examples of bacterial proteins that utilize zinc include the iron responsive regulator Fur, alcohol dehydrogenases, lyases, hydrolases, and Cu/Zn superoxide dismutases [3,16]. One mechanism by which bacteria overcome zinc sequestration is by expressing high affinity zinc transporters. At least two categories of zinc uptake systems are present in bacteria. The most prevalent zinc transporter family is homologous to the high affinity ZnuABC transport systems in Escherichia coli [17]. Znu-like systems are found in a wide variety of Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria [17]. The second category of zinc transporters is similar to the eukaryotic ZIP family transporters, however ZIP homologs have only been identified in E. coli [17]. Interestingly, bacterial zinc and manganese transporters both belong to the cluster 9 family of ABC transporters [17]. This similarity makes a priori identification of the transported substrate difficult. For example, the metal binding protein PsaA from Streptococcus pneumoniae has been shown to transport manganese in vivo but it contains zinc-coordinating histidine and aspartic acid residues that are highly conserved among zinc transporters [17,18]. Another example is TroA, which is a component of the Treponema pallidum TroABC transport system. TroA is homologous to the manganese binding protein MntA from Bacillus subtilis and hence was predicted to be a manganese transport protein. However, crystallographic studies and heterologous expression in E. coli suggest that TroA is a zinc transporter [17,19,20]. A final example of the difficulty in making metal substrate predictions is the MntABC system from Neisseria meningitidis, which transports both manganese and zinc with equal affinity [21]. These examples highlight the need for careful biochemical studies to evaluate the substrate of putative zinc and manganese transporters. While it is difficult to predict the substrate of putative transporters, inactivation of ZnuABC transport systems in several bacterial pathogens, including Campylobacter jejuini, Salmonella enterica, Haemophilus ducreyi, Uropathothogenic E. coli, Brucella abortus, and Streptococcus pyogenes results in reduced virulence or colonization [22-28]. In addition to the Znu-like ABC transporters bacteria may possess other mechanisms for battling zinc sequestration within the host. Supporting this idea is the recent observation that the ESX-3 secretion system from Mycobacterium tuberculosis is necessary for growth in zinc-limited conditions and has been postulated to secrete a factor involved in zinc acquisition [29]. Additional studies are necessary to fully define the repertoire of zinc acquisition systems expressed by bacteria and the role that zinc sequestration by the host plays in controlling bacterial infection.

The struggle for manganese

Manganese is essential to all forms of life. In vertebrate tissues, manganese concentrations range from 0.3–2.9 μg/g with higher concentrations present in metabolically active tissues such as bone, liver, pancreas, and kidneys [30]. Manganese plays an essential role in many cellular processes including lipid, protein and carbohydrate metabolism and is used by a diverse array of enzymes [1]. Unlike zinc, there is little information regarding the effects of manganese deficiency on immune development and function. There are, however, limited data suggesting that toxic levels of manganese may impair immune function [31]. Further, emerging data have revealed that vertebrates resist bacterial infections through manganese sequestration.

As is the case with zinc, LA-ICP-MS analysis of staphylococcal infection found that abscesses are devoid of detectable manganese, while the surrounding healthy tissues are replete with the metal [10]. Subsequent studies revealed that the host protein calprotectin is necessary for sequestration of manganese within abscesses (Figure 1) [10]. Calprotectin is a member of the S100 family of proteins whose contribution to nutritional immunity is discussed below. In addition to localized sequestration of manganese within tissues during infection, there is growing evidence that vertebrates limit manganese availability as a mechanism to protect against intracellular pathogens. The host protein Nramp1, is expressed by many cell types including neutrophils and macrophages, and has been shown to associate with the lysosomal marker Lamp1 [32]. Additionally, Nramp1 has been suggested to transport iron and manganese out of the lysosome [32-34]. Salmonella strains with defects in manganese transport (lacking sitABCD and/or mntH), exhibit decreased survival in primary Nramp1 +/+ peritoneal macrophages, but not in Nramp1−/− peritoneal macrophages [35,36]. In experiments employing an oral route of infection and C57BL/6 congenic mice, sitABCD and mntH mutants were markedly decreased in virulence in Nramp1 (+/+) but not Nramp1 (−/−) mice [35,36]. Taken together, these data suggest a broad role for extracellular manganese chelation and intracellular manganese transport in protecting against bacterial infection. Manganese sequestration by the host may be particularly important to the control of pathogens that have evolved to substitute manganese for iron in metalloproteins, as is the case with Borrelia burgdorferi, the causative agent of lyme disease [37]. Additional investigations are needed to fully define the extent that manganese chelation inhibits pathogenesis and to identify the host factors responsible for this arm of nutritional immunity.

Given the fact that a number of bacterial proteins are manganese dependent, it is clear that host-mediated manganese sequestration also has the potential to disrupt bacterial pathogenesis. Bacterial proteins that utilize manganese include phosphoglyceromutase, enolase, pyruvate kinase, PEP carboxylase, PEP carboxykinase, type I protein phosphatases, EAL domain containing cyclic diguanylate-specific phosphodiesterases, ppGpp synthetases, and Mn-dependent superoxide dismutases and catalases [35,38]. Furthermore, the attenuated virulence of Salmonella manganese transport mutants in Nramp1-competent mice suggests that the expression of high affinity transporters allows the bacterium to overcome manganese sequestration [35,36]. Two classes of manganese importers have been described in bacteria, Nramp homologs and MntABC transporter systems [35]. The MntABC transport systems are similar to the zinc transport systems discussed above and appear to be the most prevalent manganese transport system in bacteria [17,35]. While not as widely distributed as the MntABC transporters, bacterial Nramp manganese transporters are present in both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria [35]. Loss of known or predicted manganese transport systems has been shown to result in decreased virulence in a number of bacterial species including Brucella abortus, Yesinia pestis, S. aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae and Streptococcus pyogenes [39-45]. However, the Y. pestis and S. pyogenes systems also transport iron making it difficult to link loss of virulence to manganese transport in these cases [42,44-46]. While there are no available data examining the role of manganese transport systems in animals incapable of extracellular manganese sequestration, work with Salmonella supports a model whereby manganese transport systems allow bacteria to combat intracellular manganese sequestration [35,36]. Additional investigations are necessary to fully evaluate the contribution of bacterial manganese transport systems to pathogenesis, particularly in mice that are incompetent for sequestration of extracellular manganese. Studies are also necessary to fully define the bacterial systems that combat manganese sequestration during infection.

S100 Proteins

As discussed earlier, abscesses produced in response to S. aureus infection in mice are severely restricted in manganese and zinc (Figure 1) [10]. Recent studies have suggested that the host protein calprotectin (also known as S100A8/S100A9, calgranulin A and B, MRP-8 and MRP-9, L1, and the cystic fibrosis antigen) contributes to manganese and zinc sequestration during infection. Calprotectin is a heterodimer of S100A8 and S100A9 that accounts for 40–50% of the protein constituent of the neutrophil cytoplasm [47]. Calprotectin binds zinc in vitro and can be found in abscesses at concentrations up to 1 mg/ml [48]. Interestingly, despite in vitro evidence supporting zinc chelation by calprotectin, calprotectin-deficient C57BL/6 (S100A9−/−) mice infected with S. aureus do not exhibit noticeable alterations in zinc distribution as compared to wildtype animals. Conversely, staphylococcal abscesses from mice lacking calprotectin are replete with manganese, suggesting that calprotectin is required for removal of manganese from the staphylococcal abscess (Figure 1). This increase in available manganese in abscesses of calprotectin-deficient animals coincides with increased bacterial burden in these organs, suggesting that calprotectin-mediated manganese chelation is required to protect against microbial infection [10]. In support of these in vivo findings, calprotectin binds manganese in vitro and inhibits bacterial growth in a contact-independent manner that is reversible upon addition of either excess manganese or zinc [10]. Structural analyses predict that calprotectin has two transition metal binding sites capable of binding either zinc or manganese [49-51], providing a potential mechanistic explanation for why either metal is able to reverse growth inhibition. These later predictions have yet to be experimentally validated. It remains to be determined whether calprotectin binds zinc in vivo, or if there are other mechanisms for zinc chelation in vertebrates. In addition to calprotectin, human neutrophils also express S100A12 (calgranulin C), which binds both zinc and copper in vitro, and possesses antimicrobial activity [50-52]. Although the mechanism of antimicrobial action remains unclear, it has been suggested that S100A12-copper complexes produce superoxide at sites of infection [50]. However, in light of the data indicating that calprotectin inhibits microbial growth through manganese and zinc sequestration, it is tempting to speculate that the antimicrobial activity of S100A12 may occur through nutrient metal sequestration.

While there is a paucity of in vivo data regarding the contribution of S100 proteins to controlling microbial infection, the distribution of S100 proteins in vertebrates suggests that nutrient metal chelation may be a broad strategy to combat bacterial invaders. Calprotectin and S100A12 are found at diverse sites of inflammation [47,52]. Additionally, calprotectin and S100A12 accumulate to high concentrations in the sputum of cystic fibrosis patients during exacerbations and in the stomachs of children colonized by Helicobacter pylori [53-56]. The keratinocyte proteins S100A7 (psoriacin) and S100A15 also have antimicrobial activity [57,58]. When purified from human cells the antimicrobial activity of S100A7 can be reversed by the addition of zinc suggesting that S100A7 may inhibit microbial growth through zinc chelation. Metal-independent mechanisms of microbial inhibition have also been proposed for S100A7 [59,60]. While it is clear that calprotectin inhibits microbial growth through nutrient metal chelation, additional studies are needed to more fully define the contribution of other S100 proteins to nutritional immunity.

Conclusions

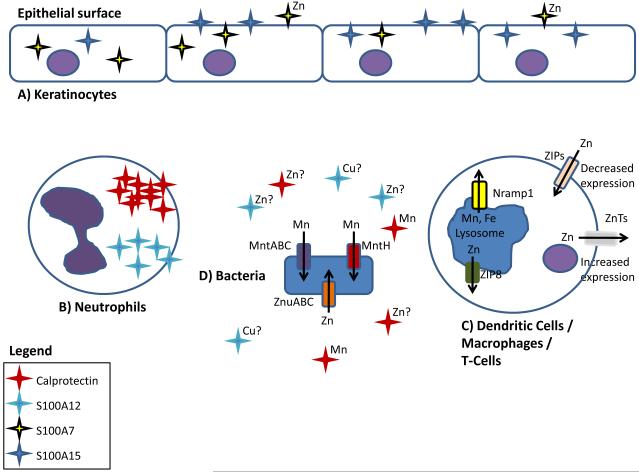

It is becoming clear that in addition to exploiting a pathogen’s need for iron as a defense strategy, vertebrates also sequester zinc and manganese (Figure 2). These observations expand the concept of nutritional immunity beyond iron and provide insights into how vertebrates defend against microbial invaders. These emerging findings raise the possibility that nutritional immunity extends to other essential transition metals, such as copper or nickel. In addition to high-affinity transport systems, bacterial pathogens may express siderophore-like molecules to facilitate the acquisition of non-iron transition metals. This idea is supported by work in methanotrophs which has shown that methanobactin facilitates copper acquisition through mechanisms analogous to siderophore-mediated iron capture [61]. To fully understand the struggle for transition metals within the vertebrate host detailed biological and chemical studies are needed. Studies investigating the competition between host and pathogen for non-iron transition metals will provide substantial insights into host defenses and bacterial physiology, and potentially lead to the development of novel therapeutics exploiting the bacterial metal requirement.

Figure 2. The battle for nutrient metal at the host pathogen interface.

Based on available literature, the following represents a working model describing the competition for non-iron metals between vertebrates and bacterial pathogens. (A) Keratinocytes express the antimicrobial compounds S100A7 and S100A15 to sequester metals and prevent infection. Following microbial infection, (B) the neutrophil proteins S100A8/S100A9 (calprotectin) and S100A12 bind manganese/zinc and copper/zinc, respectively. (C) Activated dendritic cells alter the expression of ZIP importers and ZnT exporters resulting in reduced cytoplasmic levels of zinc. ZIP8 is expressed by macrophages, dendritic cells, and T cells and results in decreased lysosomal zinc concentrations. Nramp1 is widely expressed by phagocytic cells and transports manganese out of the lysosome. (D) To compete with host-mediated zinc and manganese sequestration bacteria express high affinity metal transporters.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely apologize to our colleagues whose work we were unable to cite due to space limitations. This publication was made possible by NIH grant #U54 AI057157 from the Southeastern Regional Center of Excellence for Emerging Infections and Biodefense, and NIAID grants AI069233 and AI073843 to EPS. TKF is supported by National Institutes of Health fellowship T32 HL094296-02. The manuscript’s contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference Notes

Of special interest

#1 A detailed analysis of protein databases to determine the number of proteins that use metals as a cofactor, and the diversity of metals used by these proteins.

#27 An elegant study that evaluates the substrate of a zinc transporter and its contribution to virulence of S. pyogenes.

Of outstanding interest

#10 By applying LA-ICP-MS to the study of microbial infection in vivo, this work reveals that vertebrates remove manganese and zinc at sites of infection and manganese sequestration is mediated by the host protein calprotectin.

#36 This work demonstrates that manganese transporters are necessary for Salmonella virulence in Nramp1 expressing mice but not congenic Nramp1 deficient mice.

#58 In this study the authors identified S100A7 as the primary antimicrobial component of healthy skin. This work shows that S100A7 prevents colonization by E. coli and demonstrates that antimicrobial activity is reversed by the addition of zinc.

References

- 1.Andreini C, Bertini I, Cavallaro G, Holliday GL, Thornton JM. Metal ions in biological catalysis: from enzyme databases to general principles. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2008;13:1205–1218. doi: 10.1007/s00775-008-0404-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waldron KJ, Rutherford JC, Ford D, Robinson NJ. Metalloproteins and metal sensing. Nature. 2009;460:823–830. doi: 10.1038/nature08300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waldron KJ, Robinson NJ. How do bacterial cells ensure that metalloproteins get the correct metal? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:25–35. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wintergerst ES, Maggini S, Hornig DH. Contribution of selected vitamins and trace elements to immune function. Ann Nutr Metab. 2007;51:301–323. doi: 10.1159/000107673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weinberg ED. Iron availability and infection. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1790:600–605. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schaible UE, Kaufmann SH. Iron and microbial infection. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:946–953. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andreini C, Banci L, Bertini I, Rosato A. Counting the zinc-proteins encoded in the human genome. J Proteome Res. 2006;5:196–201. doi: 10.1021/pr050361j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gurusamy K, Davidson BR. Trace element concentration in metastatic liver disease: a systematic review. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2007;21:169–177. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Y, Tang JW, Ma WQ, Feng J. Dietary Zinc Glycine Chelate on Growth Performance, Tissue Mineral Concentrations, and Serum Enzyme Activity in Weanling Piglets. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s12011-009-8437-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corbin BD, Seeley EH, Raab A, Feldmann J, Miller MR, Torres VJ, Anderson KL, Dattilo BM, Dunman PM, Gerads R, et al. Metal chelation and inhibition of bacterial growth in tissue abscesses. Science. 2008;319:962–965. doi: 10.1126/science.1152449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Begum NA, Kobayashi M, Moriwaki Y, Matsumoto M, Toyoshima K, Seya T. Mycobacterium bovis BCG cell wall and lipopolysaccharide induce a novel gene, BIGM103, encoding a 7-TM protein: identification of a new protein family having Zn-transporter and Zn-metalloprotease signatures. Genomics. 2002;80:630–645. doi: 10.1006/geno.2002.7000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aydemir TB, Liuzzi JP, McClellan S, Cousins RJ. Zinc transporter ZIP8 (SLC39A8) and zinc influence IFN-gamma expression in activated human T cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;86:337–348. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1208759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murakami M, Hirano T. Intracellular zinc homeostasis and zinc signaling. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:1515–1522. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00854.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kitamura H, Morikawa H, Kamon H, Iguchi M, Hojyo S, Fukada T, Yamashita S, Kaisho T, Akira S, Murakami M, et al. Toll-like receptor-mediated regulation of zinc homeostasis influences dendritic cell function. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:971–977. doi: 10.1038/ni1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andreini C, Banci L, Bertini I, Rosato A. Zinc through the three domains of life. J Proteome Res. 2006;5:3173–3178. doi: 10.1021/pr0603699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vallee BL, Auld DS. Zinc coordination, function, and structure of zinc enzymes and other proteins. Biochemistry. 1990;29:5647–5659. doi: 10.1021/bi00476a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hantke K. Bacterial zinc uptake and regulators. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2005;8:196–202. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lawrence MC, Pilling PA, Epa VC, Berry AM, Ogunniyi AD, Paton JC. The crystal structure of pneumococcal surface antigen PsaA reveals a metal-binding site and a novel structure for a putative ABC-type binding protein. Structure. 1998;6:1553–1561. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(98)00153-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee YH, Dorwart MR, Hazlett KR, Deka RK, Norgard MV, Radolf JD, Hasemann CA. The crystal structure of Zn(II)-free Treponema pallidum TroA, a periplasmic metal-binding protein, reveals a closed conformation. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:2300–2304. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.8.2300-2304.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hazlett KR, Rusnak F, Kehres DG, Bearden SW, La Vake CJ, La Vake ME, Maguire ME, Perry RD, Radolf JD. The Treponema pallidum tro operon encodes a multiple metal transporter, a zinc-dependent transcriptional repressor, and a semi-autonomously expressed phosphoglycerate mutase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:20687–20694. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300781200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lim KH, Jones CE, vanden Hoven RN, Edwards JL, Falsetta ML, Apicella MA, Jennings MP, McEwan AG. Metal binding specificity of the MntABC permease of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and its influence on bacterial growth and interaction with cervical epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 2008;76:3569–3576. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01725-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davis LM, Kakuda T, DiRita VJ. A Campylobacter jejuni znuA orthologue is essential for growth in low-zinc environments and chick colonization. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:1631–1640. doi: 10.1128/JB.01394-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ammendola S, Pasquali P, Pistoia C, Petrucci P, Petrarca P, Rotilio G, Battistoni A. High-affinity Zn2+ uptake system ZnuABC is required for bacterial zinc homeostasis in intracellular environments and contributes to the virulence of Salmonella enterica. Infect Immun. 2007;75:5867–5876. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00559-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lewis DA, Klesney-Tait J, Lumbley SR, Ward CK, Latimer JL, Ison CA, Hansen EJ. Identification of the znuA-encoded periplasmic zinc transport protein of Haemophilus ducreyi. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5060–5068. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.10.5060-5068.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sabri M, Houle S, Dozois CM. Roles of the extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli ZnuACB and ZupT zinc transporters during urinary tract infection. Infect Immun. 2009;77:1155–1164. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01082-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim S, Watanabe K, Shirahata T, Watarai M. Zinc uptake system (znuA locus) of Brucella abortus is essential for intracellular survival and virulence in mice. J Vet Med Sci. 2004;66:1059–1063. doi: 10.1292/jvms.66.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weston BF, Brenot A, Caparon MG. The metal homeostasis protein, Lsp, of Streptococcus pyogenes is necessary for acquisition of zinc and virulence. Infect Immun. 2009;77:2840–2848. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01299-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campoy S, Jara M, Busquets N, Perez De Rozas AM, Badiola I, Barbe J. Role of the high-affinity zinc uptake znuABC system in Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium virulence. Infect Immun. 2002;70:4721–4725. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.8.4721-4725.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Serafini A, Boldrin F, Palu G, Manganelli R. Characterization of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis ESX-3 conditional mutant: essentiality and rescue by iron and zinc. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:6340–6344. doi: 10.1128/JB.00756-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aschner JL, Aschner M. Nutritional aspects of manganese homeostasis. Mol Aspects Med. 2005;26:353–362. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakata A, Araki S, Park SH, Park JT, Kim DS, Park HC, Yokoyama K. Decreases in CD8+ T, naive (CD4+CD45RA+) T, and B (CD19+) lymphocytes by exposure to manganese fume. Ind Health. 2006;44:592–597. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.44.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cellier MF, Courville P, Campion C. Nramp1 phagocyte intracellular metal withdrawal defense. Microbes Infect. 2007;9:1662–1670. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jabado N, Jankowski A, Dougaparsad S, Picard V, Grinstein S, Gros P. Natural resistance to intracellular infections: natural resistance-associated macrophage protein 1 (Nramp1) functions as a pH-dependent manganese transporter at the phagosomal membrane. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1237–1248. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.9.1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peracino B, Wagner C, Balest A, Balbo A, Pergolizzi B, Noegel AA, Steinert M, Bozzaro S. Function and mechanism of action of Dictyostelium Nramp1 (Slc11a1) in bacterial infection. Traffic. 2006;7:22–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Papp-Wallace KM, Maguire ME. Manganese transport and the role of manganese in virulence. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2006;60:187–209. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.60.080805.142149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zaharik ML, Cullen VL, Fung AM, Libby SJ, Kujat Choy SL, Coburn B, Kehres DG, Maguire ME, Fang FC, Finlay BB. The Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium divalent cation transport systems MntH and SitABCD are essential for virulence in an Nramp1G169 murine typhoid model. Infect Immun. 2004;72:5522–5525. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.9.5522-5525.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Posey JE, Gherardini FC. Lack of a role for iron in the Lyme disease pathogen. Science. 2000;288:1651–1653. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5471.1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zaharik ML, Finlay BB. Mn2+ and bacterial pathogenesis. Front Biosci. 2004;9:1035–1042. doi: 10.2741/1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dintilhac A, Alloing G, Granadel C, Claverys JP. Competence and virulence of Streptococcus pneumoniae: Adc and PsaA mutants exhibit a requirement for Zn and Mn resulting from inactivation of putative ABC metal permeases. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:727–739. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5111879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berry AM, Paton JC. Sequence heterogeneity of PsaA, a 37-kilodalton putative adhesin essential for virulence of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect Immun. 1996;64:5255–5262. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.5255-5262.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anderson ES, Paulley JT, Gaines JM, Valderas MW, Martin DW, Menscher E, Brown TD, Burns CS, Roop RM., 2nd The manganese transporter MntH is a critical virulence determinant for Brucella abortus 2308 in experimentally infected mice. Infect Immun. 2009;77:3466–3474. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00444-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bearden SW, Perry RD. The Yfe system of Yersinia pestis transports iron and manganese and is required for full virulence of plague. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:403–414. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Horsburgh MJ, Wharton SJ, Cox AG, Ingham E, Peacock S, Foster SJ. MntR modulates expression of the PerR regulon and superoxide resistance in Staphylococcus aureus through control of manganese uptake. Mol Microbiol. 2002;44:1269–1286. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Janulczyk R, Ricci S, Bjorck L. MtsABC is important for manganese and iron transport, oxidative stress resistance, and virulence of Streptococcus pyogenes. Infect Immun. 2003;71:2656–2664. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.5.2656-2664.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun X, Baker HM, Ge R, Sun H, He QY, Baker EN. Crystal structure and metal binding properties of the lipoprotein MtsA, responsible for iron transport in Streptococcus pyogenes. Biochemistry. 2009;48:6184–6190. doi: 10.1021/bi900552c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Perry RD, Mier I, Jr., Fetherston JD. Roles of the Yfe and Feo transporters of Yersinia pestis in iron uptake and intracellular growth. Biometals. 2007;20:699–703. doi: 10.1007/s10534-006-9051-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gebhardt C, Nemeth J, Angel P, Hess J. S100A8 and S100A9 in inflammation and cancer. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;72:1622–1631. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Clohessy PA, Golden BE. Calprotectin-mediated zinc chelation as a biostatic mechanism in host defence. Scand J Immunol. 1995;42:551–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1995.tb03695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brodersen DE, Nyborg J, Kjeldgaard M. Zinc-binding site of an S100 protein revealed. Two crystal structures of Ca2+-bound human psoriasin (S100A7) in the Zn2+-loaded and Zn2+-free states. Biochemistry. 1999;38:1695–1704. doi: 10.1021/bi982483d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moroz OV, Antson AA, Grist SJ, Maitland NJ, Dodson GG, Wilson KS, Lukanidin E, Bronstein IB. Structure of the human S100A12-copper complex: implications for host-parasite defence. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2003;59:859–867. doi: 10.1107/s0907444903004700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moroz OV, Burkitt W, Wittkowski H, He W, Ianoul A, Novitskaya V, Xie J, Polyakova O, Lednev IK, Shekhtman A, et al. Both Ca2+ and Zn2+ are essential for S100A12 protein oligomerization and function. BMC Biochem. 2009;10:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-10-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pietzsch J, Hoppmann S. Human S100A12: a novel key player in inflammation? Amino Acids. 2009;36:381–389. doi: 10.1007/s00726-008-0097-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McMorran BJ, Patat SA, Carlin JB, Grimwood K, Jones A, Armstrong DS, Galati JC, Cooper PJ, Byrnes CA, Francis PW, et al. Novel neutrophil-derived proteins in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid indicate an exaggerated inflammatory response in pediatric cystic fibrosis patients. Clin Chem. 2007;53:1782–1791. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.087650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Foell D, Seeliger S, Vogl T, Koch HG, Maschek H, Harms E, Sorg C, Roth J. Expression of S100A12 (EN-RAGE) in cystic fibrosis. Thorax. 2003;58:613–617. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.7.613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gray RD, MacGregor G, Noble D, Imrie M, Dewar M, Boyd AC, Innes JA, Porteous DJ, Greening AP. Sputum proteomics in inflammatory and suppurative respiratory diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:444–452. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200703-409OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Leach ST, Mitchell HM, Geczy CL, Sherman PM, Day AS. S100 calgranulin proteins S100A8, S100A9 and S100A12 are expressed in the inflamed gastric mucosa of Helicobacter pylori-infected children. Can J Gastroenterol. 2008;22:461–464. doi: 10.1155/2008/308942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Buchau AS, Hassan M, Kukova G, Lewerenz V, Kellermann S, Wurthner JU, Wolf R, Walz M, Gallo RL, Ruzicka T. S100A15, an antimicrobial protein of the skin: regulation by E. coli through Toll-like receptor 4. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:2596–2604. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Glaser R, Harder J, Lange H, Bartels J, Christophers E, Schroder JM. Antimicrobial psoriasin (S100A7) protects human skin from Escherichia coli infection. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:57–64. doi: 10.1038/ni1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee KC, Eckert RL. S100A7 (Psoriasin)--mechanism of antibacterial action in wounds. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:945–957. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Michalek M, Gelhaus C, Hecht O, Podschun R, Schroder JM, Leippe M, Grotzinger J. The human antimicrobial protein psoriasin acts by permeabilization of bacterial membranes. Dev Comp Immunol. 2009;33:740–746. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Balasubramanian R, Rosenzweig AC. Copper methanobactin: a molecule whose time has come. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2008;12:245–249. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.01.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]