Summary

Unlike humans, who have a continuous row of teeth, mice have only molars and incisors separated by a toothless region called a diastema. Although tooth buds form in the embryonic diastema, they regress and do not develop into teeth. Here, we identify members of the Sprouty (Spry) family, which encode negative feedback regulators of fibroblast growth factor (FGF) and other receptor tyrosine kinase signaling, as genes that repress diastema tooth development. We show that different Sprouty genes are deployed in different tissue compartments—Spry2 in epithelium and Spry4 in mesenchyme—to prevent diastema tooth formation. We provide genetic evidence that they function to ensure that diastema tooth buds are refractory to signaling via FGF ligands that are present in the region and thus prevent these buds from engaging in the FGF-mediated bidirectional signaling between epithelium and mesenchyme that normally sustains tooth development.

Introduction

Mammalian teeth develop as a result of signaling interactions between epithelium (derived from oral ectoderm) and mesenchyme (derived from cranial neural crest) (reviewed by Tucker and Sharpe, 2004). As these two tissues interact, the developing tooth progresses through four stages. First, the epithelium thickens to form a placode. Next, the epithelium invaginates into the underlying mesenchyme, while the prospective dental mesenchyme condenses around it, forming a tooth bud. Subsequently, the epithelium folds and extends farther into the mesenchyme, surrounding the dental mesenchyme to form a cap and then a bell stage tooth germ.

Epithelial morphogenesis and growth of the dental mesenchyme during the cap and bell stages are thought to be controlled by signals produced by the enamel knot, a morphologically distinct region of the epithelium containing densely-packed, nonproliferating cells (reviewed by Thesleff et al., 2001). Enamel knot activity is proposed to be mediated, at least in part, by FGF4 and FGF9, members of the fibroblast growth factor family of secreted signaling molecules. These proteins signal to the mesenchyme by activating the mesenchyme-specific “c” isoform of FGF receptors (FGFRs) and are thought to maintain Fgf3 expression in the dental mesenchyme. In turn, FGF3 (and FGF10) signal to the epithelium, where they regulate cell proliferation and morphogenesis, by activating the epithelium-specific FGFR “b” isoform (see Figure 6A). This model, which is based primarily on gain-of-function studies in organ culture and gene expression analyses, has been difficult to test genetically because inactivating each of these FGF family members individually has no effect on molar development (Harada et al., 2002; X. Sun, I. Thesleff, and G.R.M., unpublished data; O.K. and G.R.M., unpublished observations). This is presumably because of functional redundancy between Fgf4 and Fgf9 in the epithelium and Fgf3 and Fgf10 in the mesenchyme. The finding that tooth development is arrested at the bud stage when the b isoform of FGFR2 is specifically deleted in mice supports this hypothesis (De Moerlooze et al., 2000).

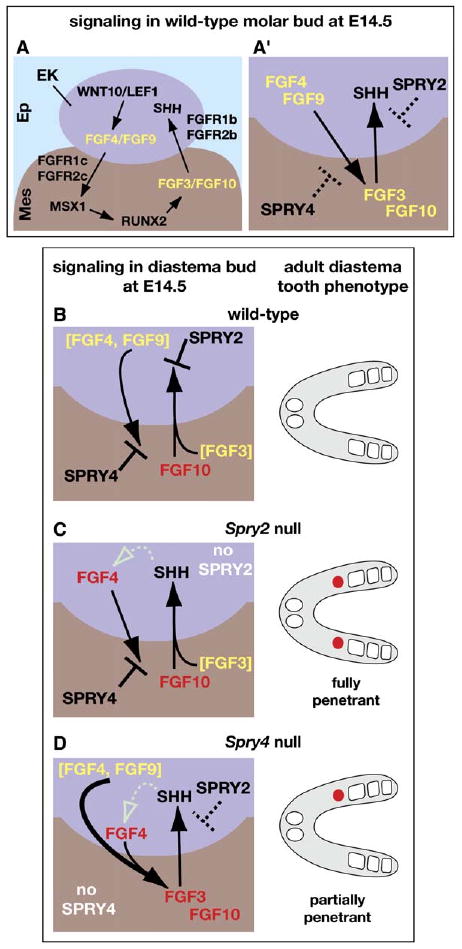

Figure 6.

Model for Dual Control of Diastema Tooth Development by Sprouty Genes

Arrows indicate a stimulatory effect, and the symbol ⊥ indicates an inhibitory effect of one signaling molecule on the expression of another. Yellow or red lettering indicates that an FGF ligand was produced in the M1 tooth germ or diastema bud, respectively. (A) Schematic representation of FGF-dependent reciprocal signaling between the enamel knot (EK) in the epithelium (Ep) and the dental mesenchyme (Mes) and the regulatory interactions that control it in a cap-stage molar tooth germ. This model is based largely on data from gene-expression studies and manipulations of tooth germs in vitro (Kettunen et al., 2000; Kratochwil et al., 2002). (A′) Condensed version of the model shown in (A) depicting Spry2 and Spry4 function. The dashed symbols indicate that Sprouty proteins do not prevent FGF signaling in molar tooth germs. (B) In wild-type diastema buds, FGF10 is produced in the mesenchyme, but any FGF4, FGF9, or FGF3 available was produced in the adjacent M1 tooth germ (brackets). SPRY2 in the epithelium and SPRY4 in the mesenchyme block signaling via FGF3/FGF10 and FGF4/FGF9, respectively, preventing Shh, Fgf4, and Fgf3 expression. Consequently, the diastema bud regresses, and no supernumerary teeth form. (C) In Spry2-null diastema buds, hypersensitivity of the enamel knot to FGF signaling enables FGF10 produced in the diastema bud mesenchyme, in conjunction with FGF3, produced in the M1 tooth germ, to induce/maintain Shh expression. Fgf4 expression is also induced/maintained, possibly in response to SHH signaling (dotted open arrow). However, FGF4 cannot signal to the mesenchyme due to antagonism by SPRY4, preventing Fgf3 expression. SHH and FGF4 produced in Spry2-null diastema buds enable virtually all of them to develop into supernumerary teeth (red circles). (D) In 15%–20% of Spry4-null diastema buds, hypersensitivity of the mesenchyme to FGF signaling, possibly FGF4/FGF9 produced in the M1 tooth germ, results in induction of Fgf3 expression in diastema bud mesenchyme (thicker arrow). The sum total of mesenchymal FGFs is then sufficient to overcome the antagonistic effects of SPRY2, resulting in Shh and Fgf4 expression, which in turn maintains Fgf3 expression and leads to formation of a diastema tooth.

The discovery of genes that encode antagonists of FGF signaling provided new opportunities for exploring FGF function in development (reviewed by Thisse and Thisse, 2005). The sprouty (spry) gene was first identified as a negative feedback regulator of FGF-mediated tracheal branching in Drosophila. FGF signaling induces D. spry expression, and via this effect, the FGF pathway limits the range of its own signaling activity (Hacohen et al., 1998). Subsequent experiments showed that D. spry also regulates epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor and other receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) signaling pathways (Casci et al., 1999; Kramer et al., 1999; Reich et al., 1999). There are four vertebrate orthologs of D. spry. In mice, Spry1, Spry2, and Spry4 are widely expressed in the embryo (de Maximy et al., 1999; Minowada et al., 1999; Zhang et al., 2001). Sprouty family members have been shown to function intracellularly to negatively regulate FGF and other RTK signaling through diverse biochemical mechanisms, often via effects on the RAS-MAPK pathway, although the mechanism of Sprouty function remains controversial (reviewed by Kim and Bar-Sagi, 2004 and Mason et al., 2006).

Loss-of-function analyses in mice have shown that Sprouty genes are required for normal development of many organs. For example, in Spry1-null mice there is excess budding of the Wolffian duct during kidney development due to hypersensitivity of the duct to GDNF, a ligand for the RET RTK (Basson et al., 2005). Spry2 nulls have several abnormalities including a severe hearing loss due to a postnatal cell fate transformation in the auditory epithelium. This defect can be partially rescued by reducing Fgf8 gene dosage (Shim et al., 2005), providing evidence that in this developmental context, Spry2 affects FGF signaling.

Here, we report that although Spry2 and Spry4 are expressed in different tissue compartments during tooth development (epithelium and mesenchyme, respectively), loss of function of either gene results in the same phenotype, i.e., formation of teeth in a region, called the diastema, that is normally toothless. These will hereafter be referred to as “diastema teeth.” We suggest a model to explain how Sprouty genes function during odontogenesis to prevent development of diastema teeth, based on evidence that they serve to block FGF-mediated crosstalk between the epithelium and mesenchyme.

Results

Spry2-Null Mice Have Teeth in the Diastema, but Molar Morphology Is Normal

Mice have fewer teeth than most mammals, with only one incisor and three molars in each dental quadrant. The incisor and most anterior molar are separated by a toothless diastema. We found that adult mice homozygous for a null allele of Spry2 (Shim et al., 2005) have a tooth in the diastema, just anterior to the first molar (M1) (Figures 1A–1D). Of 55 Spry2−/− animals examined, 92% had bilateral, 5% had unilateral, and 3% had no diastema teeth in the lower jaw. In contrast, diastema teeth were observed in the upper jaw in <5% of Spry2−/− animals. Their Spry2+/− littermates had normal dentition (n = 17). Thus, loss of Spry2 function causes the formation of supernumerary teeth in the mandible but does not significantly affect the maxilla.

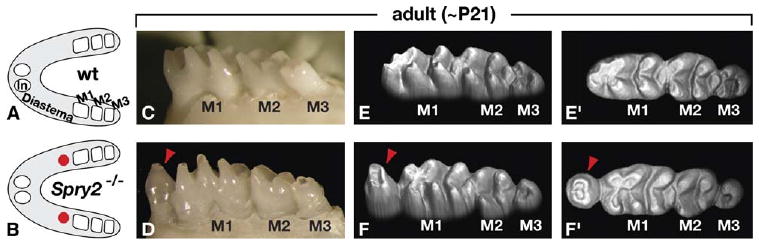

Figure 1.

Loss of Spry2 Function Causes Formation of Teeth in the Diastema

(A and B) Schematic representations of mandibles from wild-type (wt) and Spry2−/− (null) mice at ∼21 days after birth (∼P21) (anterior to the left). Spry2-null mandibles almost always contained bilateral supernumerary teeth in the diastema (red circles), just anterior to the first molar (M1).

(C and D) Side views of the molar region of wild-type and Spry2-null mice. Red arrowhead points to a diastema tooth. (E–F′) 3D models based on laser scans of wild-type and Spry2-null teeth (E and F, side views; E′ and F′, top views of the same models). Note the altered cusps of M1 immediately posterior to the supernumerary tooth (red arrowhead) but the relatively normal cusp patterns more posteriorly in the Spry2-null specimen. The third molar (M3) is smaller and the cusps less visible in the Spry2-null sample, due to delayed eruption, which is also observed in other mutants with diastema teeth (Kangas et al., 2004) (J.J., unpublished data).

We found that the morphology of Spry2-null molar cusps was essentially normal, except that in the anterior end of M1, immediately adjacent to a diastema tooth, the cusps were further apart than in wild-type molars (Figures 1E–1F′). This resulted in shortening of M1, an effect seen in other mutant mice with diastema teeth (Kangas et al., 2004; Kassai et al., 2005), possibly because of the close packing of adjacent teeth. However, in the remainder of M1, as well as in the second and third molars (M2 and M3) of Spry2-null animals, there were no consistent differences in cusp morphology as compared with wild-type, although the mutant molars were generally slightly smaller and erupted slightly later than those in wild-type mice. This contrasts with what is observed in other mouse mutants with altered tooth number, in which there are extensive modifications of molar shape, such as changes in cusp position, cusp number, and formation of additional crests (Kangas et al., 2004; Kassai et al., 2005). Thus, Spry2 is required to prevent formation of diastema teeth and does so without significantly affecting the shapes of other teeth.

Supernumerary Teeth in Spry2-Null Adults Result from Persistence of Embryonic Diastema Buds that Develop Active Enamel Knots

Although the diastema is toothless in wild-type adult mice, tooth primordia develop in the embryonic diastema but then undergo apoptosis and regress (Peterkova et al., 2002). To explore whether these transiently present buds abnormally persist in Spry2-null embryos, we compared tooth morphogenesis in wild-type and Spry2-null embryos by performing a 3D reconstruction analysis of serial sections through mandibular diastema and molar regions on embryonic day (E) 14.5 and E15.5 (Figures 2A–2D). Consistent with previous reports (Peterkova et al., 2002), in E14.5 wild-type mandibles, we observed a thickening at the anterior end of the M1 tooth germ, which appeared to be the remnant of the regressing diastema tooth bud (Figure 2A). At this embryonic age, the M1 tooth germ was at the cap stage and contained a well-developed enamel knot (Figure 2A and data not shown). At E15.5, the diastema bud could no longer be discerned, the M1 tooth germ was at the late cap or cap-bell transition stage, and M2 was just beginning to develop (Figure 2B). In contrast, in Spry2-null embryos, at E14.5, the diastema bud was a robust swelling just anterior to M1 (Figure 2C), and by E15.5, it had clearly developed into a distinct tooth germ (Figure 2D). Thus, the supernumerary teeth in Spry2-null adults form as a result of abnormal survival and development of diastema tooth buds.

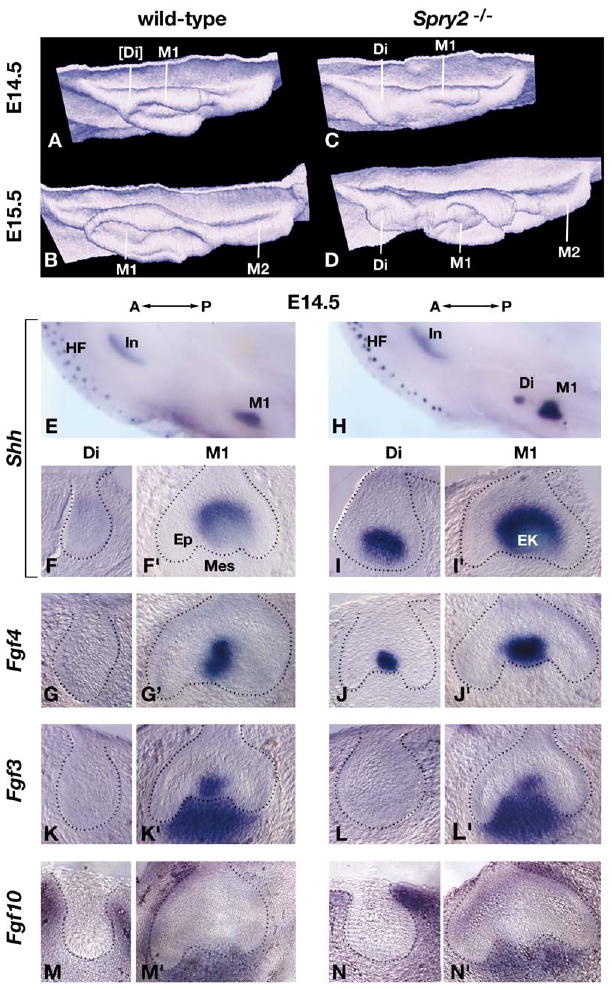

Figure 2.

Loss of Spry2 Function Results in Persistence of the Diastema Bud Enamel Knot

(A–D) 3D reconstructions of dental epithelium (viewed from the perspective of the mesenchyme) in wild-type and Spry2−/− posterior mandibles at E14.5 and E15.5 (anterior is to the left). The approximate positions of the diastema (Di), first molar (M1), and second molar (M2) tooth germs are indicated. The square brackets indicate that the diastema bud in panel (A) is regressing.

(E–N′) Gene expression was analyzed by in situ hybridization in whole mount followed by serial sectioning of control (wild-type or Spry2+/−) and Spry2-null mandibles at the stages indicated. Examples of the whole-mount preparations are shown in panels (E) and (H). In the remaining panels, for each probe, sections from the same mandible are shown; the section on the left was taken from a more anterior region and illustrates the diastema (Di) tooth germ, and the one on the right (′) illustrates the M1 tooth germ. In Spry2-null diastema and all M1 tooth germs, the sections pass through or are adjacent to the enamel knot. Shh and Fgf4 expression is detected exclusively in the enamel knot, and Fgf3 expression is detected in both enamel knot and dental mesenchyme. The dotted lines demarcate the boundary between epithelium and mesenchyme. Abbreviations: A, anterior; EK, enamel knot; Ep, epithelium; HF, hair follicles; In, incisor; Mes, mesenchyme; P, posterior.

Since tooth development is dependent on the presence of a functional enamel knot, we assayed wild-type and mutant embryonic tooth germs for the expression of two genes, Shh and Fgf4, that reflect enamel knot activity (Vaahtokari et al., 1996) (Figures 2E–2J′ and data not shown). In control (wild-type or Spry2+/−) mandibles at E14.5, Shh and Fgf4 expression was readily detected in sections through M1 tooth germs but not in more anterior sections, where the diastema bud remnants were localized (Figure 2E–2G′). In contrast, in Spry2-null embryos, Shh and Fgf4 expression was readily detected in both diastema and M1 tooth germs at E14.5 and E15.5 (Figures 2H–2J′ and data not shown). We also assayed for other genes that might play a role in promoting the development of diastema buds into teeth, including Bmp4 (Neubuser et al., 1997), Activin (Ferguson et al., 1998), Ectodin (Kassai et al., 2005), and Lef1 (Kratochwil et al., 2002), by examining their expression in whole mount at E14.5. We found no obvious difference in the levels or domains of their expression in control versus Spry2-null dental epithelium or mesenchyme (not shown), suggesting that Spry2 acts downstream of these pathways. Together, these data show that the diastema buds in Spry2-null mice contain a functional enamel knot, which presumably enables them to develop into teeth.

The Expression Patterns of Sprouty, FGF Receptor, and FGF Ligand Genes Suggest a Mechanism whereby Loss of Spry2 Function Leads to Diastema Tooth Formation

To determine how loss of Spry2 function results in enamel knot gene expression, we first analyzed the Spry2 expression pattern by in situ hybridization. Because Sprouty proteins function intracellularly to antagonize RTK signaling (reviewed by Kim and Bar-Sagi, 2004 and Mason et al., 2006), such assays identify the primary site(s) of Spry2 function. In wild-type diastema and M1 tooth germs at E14.5, we detected abundant Spry2 expression throughout the epithelium adjacent to dental mesenchyme, including the M1 enamel knot. Much lower levels of Spry2 RNA were detected throughout the rest of the dental epithelium and in the M1 dental mesenchyme (Figures 3A and 3A′). We also detected Spry1 RNA at a low level in diastema buds and at a higher level in M1 tooth germs. Expression was widespread throughout the M1 epithelium and mesenchyme, but appeared to be specifically excluded from the enamel knot (Figures 3B and 3B′). In contrast, we detected Spry4 RNA exclusively in dental mesenchyme in both diastema and M1 tooth germs (Figures 3C and 3C′). Comparable expression patterns were observed at E12.5 and E13.5 (not shown).

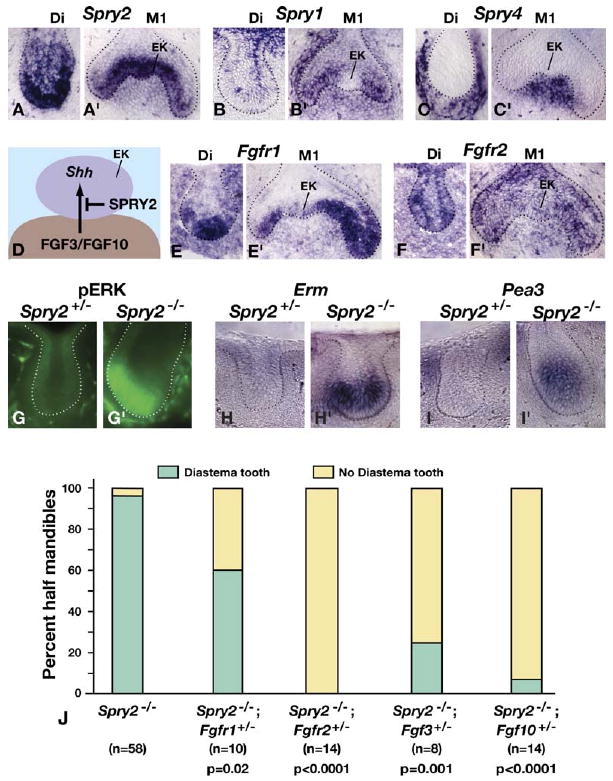

Figure 3.

Molecular and Genetic Evidence that Supernumerary Tooth Formation Results from Hypersensitivity to FGF Signaling

(A–C′ and E–F′) Sprouty and FGF receptor family gene expression was assayed by in situ hybridization of frontal sections of E14.5 mandibles. For each probe, sections of the diastema and M1 tooth germs were taken from the same embryo (see legend to Figure 2). Note that expression of Fgfr1 and Fgfr2 is detected in the enamel knot (EK).

(D) A model for the effect of SPRY2 on FGF signaling from the dental mesenchyme to the enamel knot.

(G and G′) Immunolocalization of pERK in control and Spry2 diastema buds at E14.5.

(H–I′) Analysis by in situ hybridization for expression of Erm and Pea3, which are thought to be direct targets of RTK signaling, in E14.5 control and Spry2-null diastema buds. Assays were performed as described for gene-expression studies in Figure 2.

(J) Effects on supernumerary tooth formation of reducing dosage of the indicated genes in Spry2-null animals. For each animal examined, the left and right sides of the mandible were scored independently for the presence of a diastema tooth. Data on Spry2-null littermates from all of the crosses used to generate animals with reduced gene dosage were pooled. p values were calculated with the Fisher exact test.

Data from gene expression studies and manipulations of tooth germs in vitro have suggested that Shh expression in the enamel knot is induced/maintained by signaling from mesenchyme to epithelium via FGF3 and FGF10 (Kettunen et al., 2000; Kratochwil et al., 2002). Since Spry2 is expressed in the enamel knot epithelium, this raises the possibility that the normal function of SPRY2 is to prevent Shh expression in the diastema bud by inhibiting FGF signaling from the mesenchyme (Figure 3D). This hypothesis relies on the assumption that FGF receptor (FGFR) genes function in the enamel knot. Although it has previously been reported that none of the FGFR genes are expressed in the enamel knot (Kettunen et al., 1998), we detected weak expression of both Fgfr1 and Fgfr2 in the wild-type molar enamel knot at E13.5 and E14.5 (Figures 3E′ and 3F′ and data not shown). More importantly, in the epithelium of the diastema bud, where the enamel knot would be localized if the bud developed, we observed Fgfr1 expression at a high level and Fgfr2 at a lower level at E13.5 and E14.5 (Figures 3E and 3F and data not shown).

These data suggest a model whereby lack of SPRY2 function renders the diastema bud epithelium hypersensitive to FGF signaling from the mesenchyme, thereby maintaining Shh expression. In principle, either FGF3 or FGF10 could be a mesenchymal FGF that performs this function. However, we never detected Fgf3 RNA in the diastema bud of either control or Spry2-null embryos at E14.5 (n = 20) or E15.5 (n = 10) (Figures 2K and 2L and data not shown), but it was detected at high level in the mesenchyme (and enamel knot) of the nearby M1 tooth germs (Figures 2K′ and 2L′). Fgf10 RNA was detected at low levels in wild-type and Spry2-null embryos at E13.5, E14.5, and E15.5, in a long swath in the mesenchyme of the region containing the diastema and molar tooth germs (Figures 2M–2N′ and data not shown). Based on these findings, we propose that in Spry2-null embryos, FGFs produced in the mesenchyme are sufficient to induce and/or maintain expression of Shh and perhaps also other genes, such as Fgf4, that are required for enamel knot function, thereby enabling diastema buds to form teeth.

Loss of Spry2 Function Causes Hypersensitivity to FGF Signaling in Diastema Bud Epithelium

One prediction that follows from the hypothesis that Spry2 functions to inhibit FGF signaling in diastema bud epithelium is that in the absence of Spry2 function, we should detect elevated FGF signaling. Phosphorylation of MAP kinase (ERK) is considered an indication of FGFR activation, although it also reflects signaling via other RTKs (Eswarakumar et al., 2005). Using an antibody that detects only the phosphorylated form of ERK (pERK) (Corson et al., 2003), we observed little or no staining in control and extensive staining in Spry2-null diastema buds at E14.5 (Figures 3G and 3G′). In addition, we detected elevated expression of Erm and Pea3, two genes considered to be direct targets of RTK signaling (O'Hagan and Hassell, 1998; Roehl and Nusslein-Volhard, 2001), in Spry2-null epithelium as compared with control diastema bud epithelium (Figures 3H–3I′). These data indicate that loss of Spry2 function results in an increase in RTK signaling in diastema bud epithelium.

If it is true that loss of Spry2 function leads to tooth development by rendering diastema bud epithelium hypersensitive to FGF signaling, then reducing dosage of the relevant FGF receptor gene(s) should eliminate the supernumerary teeth. To test this prediction, we produced Spry2-null animals that were wild-type for FGFR genes, or in which Fgfr1 or Fgfr2 gene dosage was reduced, and scored each half of the mandible (hm) for the presence or absence of a supernumerary tooth. In those Spry2-null animals from these crosses with wild-type FGFR gene dosage, all but one hm had a diastema tooth (Figure 3J). In contrast, heterozygosity for a null allele of Fgfr1 (Trokovic et al., 2003) reduced the frequency of supernumerary tooth formation to 60%, and heterozygosity for a null allele of Fgfr2 (Yu et al., 2003) reduced it to 0%. These data provide genetic evidence that diastema tooth formation in the absence of SPRY2 is due to excess signaling via FGFR1 and FGFR2. Furthermore, we found that heterozygosity for a null allele of either Fgf3 (Alvarez et al., 2003) or Fgf10 (Min et al., 1998) in Spry2-null animals almost completely prevented diastema tooth formation (Figure 3J), indicating that FGF3 and FGF10 are ligands to which Spry2-null diastema buds are hypersensitive.

Loss of Spry4 Function also Causes Teeth to Develop in the Diastema

It has been proposed that one function of FGF4 produced in the enamel knot is to induce Fgf3 expression in the dental mesenchyme (Kettunen et al., 2000; Kratochwil et al., 2002). Surprisingly, Fgf3 RNA was not detected in Spry2-null diastema buds (Figure 2L) despite the presence of a functional enamel knot expressing Fgf4 (Figure 2J). One explanation for this observation might be that Spry4, which is abundantly expressed in dental mesenchyme (Figures 3C and 3C′), antagonizes the response to FGF signaling from the enamel knot and thus prevents Fgf3 expression (Figure 4A). To explore the function of Spry4 in diastema tooth development, we produced mice carrying a Spry4-null allele (Figure 5), by using the same strategy that we previously employed to generate a Spry2 mutant allelic series (Shim et al., 2005). Adults homozygous for the Spry4-null allele were viable and fertile.

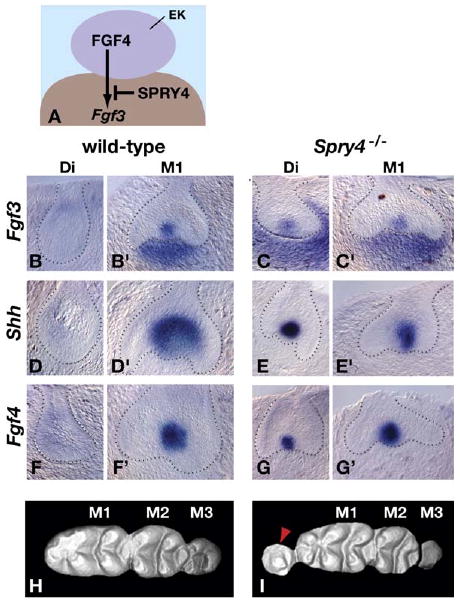

Figure 4.

Loss of Spry4 Function Results in Diastema Tooth Formation

(A) A model for the effect of SPRY4 on FGF signaling from the enamel knot to the dental mesenchyme.

(B–G′) In situ hybridization analysis of gene expression in frontal sections of control (wild-type or Spry4+/−) and Spry4-null diastema (Di) and first molar (M1) tooth germs at E14.5. The dotted lines demarcate the boundary between epithelium and mesenchyme.

(H and I) Three-dimensional models based on laser confocal scans (anterior to the left) of wild-type and Spry4-null teeth (viewed from the top). Note the relatively normal cusp morphology in the molars posterior to the supernumerary tooth (red arrowhead) in the Spry4-null specimen, excluding the anterior cusp of M1. Eruption of M3 is delayed in the Spry4-null mouse, and the cusps are not yet visible.

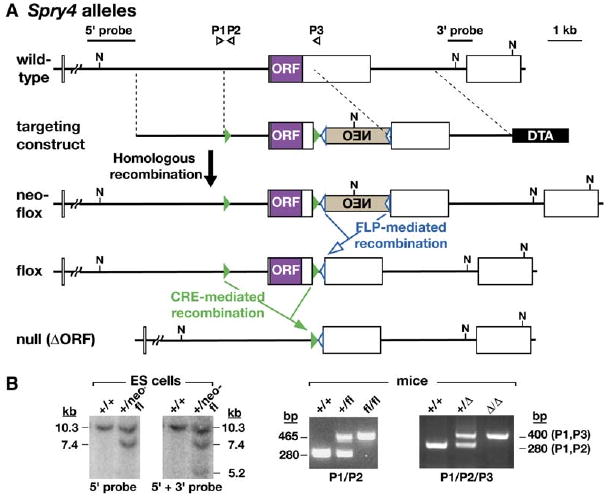

Figure 5.

Production of a Spry4 Mutant Allelic Series

(A) Schematic representation of the Spry4 wild-type allele, targeting construct, and Spry4neo-flox allele produced by gene replacement in ES cells. A horizontal line and boxes represent Spry4 intron and exon sequences, respectively. A purple box represents the Spry4 open reading frame (ORF; contained within a single exon). Positive and negative selection during targeting were provided by a neomycin-resistance (NEO) expression cassette (tan box), inserted in reverse orientation to the Spry4 gene, and a diphtheria toxin A (DTA) expression cassette (black box), respectively, each under the control of a Pgk1 promoter. Open blue and filled green triangles represent frt and loxP sites, the recognition sites for Flp and Cre recombinases, respectively. The two pairs of dotted parallel lines demarcate the regions in which homologous recombination occurred. The positions of the probes and primers (P1–P3) used for genotyping the various alleles are indicated. Mice heterozygous for Spry4neo-flox were produced as described in Experimental Procedures and mated to flp transgenic mice (Rodriguez et al., 2000) to generate animals carrying the Spry4flox conditional null allele. Mice heterozygous for Spry4flox were mated to β-actin-cre transgenic mice (Lewandoski et al., 2000) to generate animals carrying the Spry4ΔORF-null allele. N, NcoI restriction enzyme site. (B) Identification of ES cells and mice carrying Spry4 mutant alleles. Correctly targeted ES cells carrying Spry4neo-flox were identified by Southern blotting DNA digested with NcoI and by using the probes indicated. Mice heterozygous or homozygous for Spry4flox or Spry4ΔORF were identified by a PCR assay by using the primers indicated.

We detected Fgf3 RNA in diastema tooth germs in 17% of hm from Spry4-null animals examined at E14.5 (n = 42) (Figures 4B–4C′). A similar percentage of Spry4-null diastema tooth germs were found to express Shh (20% of hm; n = 60) and Fgf4 (15% of hm; n = 20), but no Shh or Fgf4 expression was detected in the diastema buds of their wild-type or Spry4+/− littermates at E14.5 (Figures 4D–4G′). Significantly, diastema teeth were present at the same frequency in Spry4-null adults (16% of hm; n = 94) as abnormal gene expression was seen in Spry4-null embryos. These supernumerary teeth were almost always unilateral. As in Spry2-null mice, the molar cusp patterns were essentially normal in Spry4-null mice (Figures 4H and 4I). Thus our data suggest that SPRY4 functions to repress diastema bud development by preventing FGF signaling from maintaining Fgf3 expression in the dental mesenchyme.

Discussion

The toothless diastema has been a feature of mouse dentition for over 50 million years. Lineages with diastemata have arisen independently several times during evolution, often as a result of a decrease in tooth number. In mice, the mechanisms for preventing tooth formation in the diastema appear to range from a block in initiation of tooth development, in the anterior region near the incisors, to suppression of tooth development beyond the bud stage, in the posterior region adjacent to the molars (Peterkova et al., 2002). Here, we demonstrate that Sprouty genes are essential components of the molecular machinery that normally prevents embryonic diastema tooth buds from developing into teeth and that different Sprouty genes cooperate to ensure that the diastema remains toothless.

FGF Signaling in Diastema versus Molar Buds

Our data show that in the tooth buds that form in the wild-type embryonic diastema, the genetic program that normally controls progression from the bud to the cap stage is not active. Thus, we found that by E14.5, expression of Shh, Fgf4, and Fgf3 was not detected in wild-type diastema buds (Figure 2). We made an effort to determine whether this observation reflected a lack of induction of gene expression or a failure to maintain it after it was initiated. Expression of these three genes was invariably detected by whole-mount in situ hybridization in wild-type embryos at E13.5-E14.0. In almost all cases, the signal in the prospective molar region was restricted to a single domain, presumably the M1 bud. However, occasionally we detected two adjacent but distinct domains of Shh expression in the molar region: a small and relatively weak anterior and a larger and stronger posterior expression domain (not shown) (Kangas et al., 2004). These results suggest that the diastema bud expresses Shh but only transiently and at low level. We did not detect similar dual domains of Fgf4 or Fgf3 expression in the wild-type molar region, suggesting that these FGF genes are never expressed in the diastema bud. However, our finding that Sprouty genes, which are known to be downstream targets of RTK signaling, are robustly expressed in diastema buds from at least E12.5 (Figure 3 and data not shown) suggests that these tooth germs have been exposed to FGF or other RTK signaling.

Based on these data, we suggest that one mechanism by which diastema bud development is normally suppressed is via inhibition of FGF gene expression, including Fgf4 in the enamel knot and Fgf3 in the dental mesenchyme. In the developing molars, several factors are required for expression of FGF genes (Figure 6A), including the LEF1 transcription factor, whose expression is regulated by WNT10 (Kratochwil et al., 2002). BMP signaling may also be involved since the BMP and FGF signaling pathways interact during molar development, both at the time when it is initiated (Neubuser et al., 1997) and at later stages (Bei and Maas, 1998; Kassai et al., 2005). Differences in expression of one or more of these molecules between diastema and M1 buds at early stages may account for the lack of FGF gene expression in diastema buds and its abundance in M1 buds by E14.5.

A Model for Sprouty Gene Function in Suppressing Diastema Tooth Development

We show that in the absence of Spry2 function the diastema bud persists and develops into a tooth (Figures 1 and 2), that phosphorylation of ERK and expression of RTK signaling target genes is increased in diastema bud epithelium (Figure 3), and that decreases in dosage of genes that encode FGF ligands expressed in dental mesenchyme or FGF receptors can rescue the Spry2 loss-of-function phenotype (Figure 3). These data provide strong support for the hypothesis that loss of Spry2 function results in the development of diastema teeth by causing increased sensitivity of diastema bud epithelium to FGF signaling. Likewise, we suggest that the reason that loss of Spry4 function results in a similar phenotype, i.e., diastema tooth formation (Figure 4), is that it causes hypersensitivity of diastema bud mesenchyme to FGF signaling.

Interestingly, Sprouty genes are required to prevent diastema tooth development even though there is little or no FGF gene expression in wild-type diastema buds. A model for how they might function is illustrated in Figure 6. In molar tooth germs (Figure 6A′), although Sprouty genes are expressed and presumably modulate FGF signaling, they do not block the activity of either mesenchymal (FGF3 and FGF10) or epithelial (FGF4 and FGF9) FGFs. In wild-type diastema buds (Figure 6B), the only FGF gene expression we detected was that of Fgf10. We found no conclusive evidence that Fgf3 or Fgf4 are expressed in the wild-type diastema bud between E11.5 and E15.5, and we did not detect expression of Fgf8, Fgf9, or Fgf20 at any of these stages. Thus, we propose that the normal function of Spry2 is to prevent the relatively low level of signaling via FGF10 produced in diastema bud mesenchyme from inducing/maintaining Shh expression. However, since we found that reducing Fgf3 gene dosage in Spry2-null mice prevents diastema tooth formation, Spry2 must also normally function to prevent signaling via FGF3 from inducing/maintaining Shh expression. In light of our evidence that Fgf3 is never expressed in the wild-type diastema bud, it seems likely that the source of FGF3 is the adjacent M1 tooth germ. Likewise, the normal function of Spry4 in the mesenchyme is to prevent any epithelial FGF signals, including FGF4 and FGF9 produced in the adjacent M1 tooth germ from inducing/maintaining Fgf3 expression. As a result of the combined activities of Spry2 and Spry4, the diastema bud regresses and there are no teeth in the adult diastema.

According to our model, in the absence of Sprouty gene function, diastema bud tissues become hypersensitive to FGF signaling, and the diastema bud is sustained and develops into a tooth. In the case of the Spry2-null diastema bud (Figure 6C), our genetic data argue that it is both FGF10 (produced in diastema bud mesenchyme) and FGF3 (produced in the M1 tooth germ) that induces/maintains Shh expression. Fgf4 expression is also induced/maintained in the Spry2-null enamel knot, but the factors responsible for this effect have not been identified. SHH activity is one possible candidate, by analogy to its function in the limb bud where it is required to upregulate/maintain the expression of Fgf4, Fgf9, and Fgf17 (Sun et al., 2000). However, in vitro studies aimed at demonstrating that SHH can induce Fgf4 expression in tooth germ epithelium have thus far been unsuccessful (J.J. and I. Thesleff, unpublished data). WNT activity might be involved since Fgf4 is known to be a downstream target of WNT signaling in the developing molar (Kratochwil et al., 2002). However, we detected no expression of the WNT target gene Lef1 in the diastema bud region of Spry2-null embryos (not shown). Interestingly, the FGF4 that is produced in the Spry2-null diastema buds is prevented from inducing/maintaining Fgf3 in the mesenchyme, presumably by SPRY4 and other factors that are produced there. Despite the lack of Fgf3 expression, the SHH and FGF4 produced in the enamel knot are sufficient to sustain development of the Spry2-null diastema buds, and teeth almost always form in the diastema.

In the case of the Spry4-null diastema bud (Figure 6D), FGF signaling from the epithelium is sufficient to induce Fgf3 expression in mesenchyme that is hypersensitive to FGF signaling due to the loss of Spry4 function. Because Fgf4 and Fgf9 are not expressed in wild-type diastema buds, we speculate that this inducing signal is FGF4/FGF9 from the nearby M1 tooth germ, or perhaps some other epithelial FGF. FGF3, in conjunction with FGF10, then overcomes the antagonistic effects of SPRY2 and induces/maintains Shh expression in the enamel knot. As in Spry2-null diastema buds, Fgf4 expression is also induced/maintained in the enamel knot by unknown factors. This FGF4 presumably contributes to the signal that maintains Fgf3 expression, leading to diastema tooth formation, although at low frequency (16%). The penetrance of the diastema tooth phenotype can be increased ∼3-fold in Spry4-null animals by heterozygosity for a Spry1-null allele (Basson et al., 2005), whereas heterozygosity for a Spry2-null allele has no effect (data not shown). Because Spry1 is expressed in both mesenchyme and epithelium, whereas Spry2 is expressed primarily in the epithelium, together these data suggest (but do not prove) that mesenchymal SPRY1 cooperates with SPRY4 to antagonize FGF signaling to the mesenchyme. Interestingly, Spry1-null adults have grossly normal dentition (not shown), indicating that Spry1 is functionally redundant with Spry4, and Spry1 function in the diastema bud is only revealed in a Spry4-null context.

The model we discuss here for Sprouty gene function in mouse odontogenesis is analogous to the proposed role for Sprouty genes in other developmental systems. Perhaps the most pertinent example comes from studies of Spry1 function in kidney morphogenesis, where SPRY1 acts to ensure that the Wolffian duct anterior to the normal site of ureteric bud formation is refractory to GDNF produced at an earlier stage, thereby preventing supernumerary ureteric buds from developing (Basson et al., 2005). In that case, Sprouty genes are expressed throughout the Wolffian duct, including the region where the ureteric bud normally forms, but they do not block its development. This is remarkably similar to what is observed during mouse odontogenesis, where development of one tooth primordium—the diastema bud—is repressed by Sprouty genes, but development of the nearby molar bud is not. The molecular mechanisms that enable cells in molar tooth germs to escape the inhibitory effects of Sprouty gene expression remain to be elucidated. However, it seems likely that at least part of the reason why they do so is that molar tooth germs express higher levels of FGF genes, and perhaps other molecules that favor progression of tooth development, than do diastema buds.

Other Pathways Affecting Diastema Tooth Development

Diastema teeth similar to those observed in Sprouty mutant mice have been found in other mouse mutants. For example, they have been reported in mice carrying a hypomorphic allele of Polaris (Zhang et al., 2003), a gene required for assembly of cilia and for normal SHH signaling (Huangfu and Anderson, 2005; Haycraft et al., 2005). Overexpression of Ectodysplasin (Eda), a member of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) family of signaling molecules, also results in formation of diastema teeth (Mustonen et al., 2003), as does inactivation of Ectodin, a gene that encodes an inhibitor of BMP activity (Kassai et al., 2005). The latter effect may be due to upregulation of TNF signaling as expression of Edar, the Ectodysplasin receptor, was found to be increased in Ectodin-deficient molar tooth germs (Supplemental Data in Kassai et al., 2005). As yet, no molecular analysis of the diastema buds in any of these mutants has been reported, so it is not known if there are changes in gene expression similar to those that we observed in Sprouty mutants. There are, however, some intriguing differences between the final phenotypes. In particular, in Polaris mutants, diastema teeth are found in both the mandible and maxilla, whereas in Sprouty mutants and in mice overexpressing Eda, for reasons that are not yet understood, they are found almost exclusively in the mandible. Furthermore, overexpression of Eda and loss of Ectodin function primarily cause large changes in the shapes of the other teeth, particularly in cusp morphology, whereas the effects of loss of Sprouty gene function are essentially restricted to promoting development of diastema teeth. This distinction is critical because during evolution, changes in tooth number have frequently occurred without a concomitant change in the morphology of the adjacent teeth. This evolutionary evidence suggests that there must be decoupled developmental mechanisms controlling tooth number and shape. Our data identify Sprouty genes as potential mediators of evolutionary changes specifically in tooth number and implicate regulation of FGF signaling in this process.

Concluding Remarks

One of the most intriguing aspects of this study is our discovery that different members of the Sprouty gene family are deployed in different tissues to modulate the reciprocal signaling between epithelium and mesenchyme, thereby ensuring that a particular process—in this case diastema tooth formation—is prevented. Thus, Spry2 in the epithelium, and Spry4 in the mesenchyme, apparently perform the same function. It seems likely that similar use of complementary expression patterns of different Sprouty family members to finely tune signaling between epithelium and mesenchyme is made in other developmental contexts and that additional examples of such dual negative control of signaling between tissues will be uncovered by future studies of Sprouty and other gene families that encode antagonists of intercellular signaling.

Experimental Procedures

Mouse Lines

The targeting vector used to produce the Spry4neo-flox allele in ES cells was constructed with ∼8.6 kb of Spry4 genomic DNA isolated from a P1 strain 129/Ola ES cell library (Genome Systems, St. Louis) and was electroporated into E14Tg2a.4 ES cells. 2/206 ES cell clones assayed by Southern blotting were found to be correctly targeted. Germline transmission of the Spry4neo-flox allele was obtained following injection of a correctly targeted ES cell line into C57BL/6 blastocysts (performed by the Stanford University Transgenic Research Facility). Lines carrying the Spry4flox conditional and Spry4ΔORF-null alleles were derived by crossing mice carrying Spry4neo-flox to Flp- and Cre-expressing mice, as described in the legend to Figure 5. The sequences of the primers shown in Figure 5 are: P1, 5′-CAGGACTTGGGAGTGCTTCCTTAG-3′; P2, 5′-CCTCCTAGTACCTTTTTGGGGAGA G -3′; P3, 5′-TACAGCAGGAATGGCTACGGTG-3′. For both P1/P2 and P1/P3 primer combinations, standard PCR conditions were used with an annealing temperature of 57°C. The Spry4-null allele was maintained on a mixed genetic background.

3D Analysis of Adult Molar Shape

Selected jaw specimens were scanned with a Nextec Hawk laser scanner with 10 μm measurement sampling intervals, and each tooth row was scanned from four different directions. Tooth shapes were rendered and cusp features were examined in three dimensions as previously described (Kassai et al., 2005). Tooth crown features from 24 Spry2-null, 24 Spry4-null, and 19 wild-type mandibles were scored as characters and morphologies were compared as previously described (Kangas et al., 2004). Shape data are stored in a comparative MorphoBrowser database at http://www.biocenter.helsinki.fi/bi/evodevo/morphobrowser/.

Gene Expression Analysis

To stage embryos, noon of the day when a vaginal plug was detected was considered E0.5. RNA in situ hybridization was performed according to standard protocols on jaws that were fixed in 4% PFA and either embedded in OCT and cryosectioned (10 μm intervals) before hybridization (Figure 3) or hybridized in whole-mount and then sectioned on a vibratome (30 μm intervals) (Figures 2 and 4). To generate digoxigenin-labeled probes, we used plasmids containing mouse Activin, Bmp4, Ectodin, Erm, Fgf3, Fgf4, Fgf8, Fgf9, Fgf10, Fgf20, Fgfr1, Fgfr2, Lef1, Pea3, Shh, Spry1, Spry2, and Spry4 sequences for in vitro transcription.

3D Reconstructions of Embryonic Tooth Germs

The contours of the mandibular dental and adjacent oral epithelium were drawn from serial frontal sections (7 μm intervals), and three-dimensional images were generated as previously described (Lesot et al., 1996).

pERK Immunohistochemistry

Mandibles were dissected in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). After embedding in 4% agarose, serial 100 μm vibratome sections were cut. Sections were washed in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Triton X-100 (TBST), blocked in 3% bovine serum albumin in TBST, and incubated overnight in anti-phosphoERK antibody (Cell Signaling, #9101) diluted 1:100 in TBST. After washing, sections were incubated overnight with the anti-rabbit Alexa 488 secondary antibody (Molecular Probes) at 1:200 in TBST and then washed prior to mounting in Vectashield (Vector Laboratories). Samples were examined on a Leica fluorescent microscope.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. M. Lewandoski, D. Ornitz, A. McMahon, and S. McConnell for helping us to obtain the mutant mouse lines used in this study and Drs. I. Thesleff and S. Arber for in situ probes. We are grateful to C. Ahn, P. Ghatpande, and A. Nemati for excellent technical assistance and S. Churava, M. Rothova, T. Boran, and J.J. Fluck for preparation of data for 3D reconstructions. We also thank Drs. L. Hlusko, U. Grieshammer, A. Basson, M. Davis, and A. Evans for helpful discussion and advice and our laboratory colleagues for critical reading of the manuscript. Contributors to this work were supported by: a Pediatric Scientist Development Program award from the National Institutes of Health (K12-HD00850 to O.K.); KO8 awards from the National Institutes of Health (CA60538 to G.M. and HD047674 to B.D.Y.). This work was supported by grants from the Grant Agency of the Czech Republic (GACR) (304/05/2665), the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic (ASCR) (AV0Z 50390512), and the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic (COST B23.002) to R.P. and M.P., the Academy of Finland to J.J., and from the National Institutes of Health (RO1 CA78711) to G.R.M.

References

- Alvarez Y, Alonso MT, Vendrell V, Zelarayan LC, Chamero P, Theil T, Bosl MR, Kato S, Maconochie M, Riethmacher D, Schimmang T. Requirements for FGF3 and FGF10 during inner ear formation. Development. 2003;130:6329–6338. doi: 10.1242/dev.00881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basson MA, Akbulut S, Watson-Johnson J, Simon R, Carroll TJ, Shakya R, Gross I, Martin GR, Lufkin T, McMahon AP, et al. Sprouty1 is a critical regulator of GDNF/RET-mediated kidney induction. Dev Cell. 2005;8:229–239. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bei M, Maas R. FGFs and BMP4 induce both Msx1-independent and Msx1-dependent signaling pathways in early tooth development. Development. 1998;125:4325–4333. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.21.4325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casci T, Vinos J, Freeman M. Sprouty, an intracellular inhibitor of Ras signaling. Cell. 1999;96:655–665. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80576-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corson LB, Yamanaka Y, Lai KM, Rossant J. Spatial and temporal patterns of ERK signaling during mouse embryogenesis. Development. 2003;130:4527–4537. doi: 10.1242/dev.00669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Maximy AA, Nakatake Y, Moncada S, Itoh N, Thiery JP, Bellusci S. Cloning and expression pattern of a mouse homologue of drosophila sprouty in the mouse embryo. Mech Dev. 1999;81:213–216. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00241-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Moerlooze L, Spencer-Dene B, Revest J, Hajihosseini M, Rosewell I, Dickson C. An important role for the IIIb isoform of fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2) in mesenchymal-epithelial signalling during mouse organogenesis. Development. 2000;127:483–492. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.3.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eswarakumar VP, Lax I, Schlessinger J. Cellular signaling by fibroblast growth factor receptors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16:139–149. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson CA, Tucker AS, Christensen L, Lau AL, Matzuk MM, Sharpe PT. Activin is an essential early mesenchymal signal in tooth development that is required for patterning of the murine dentition. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2636–2649. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.16.2636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacohen N, Kramer S, Sutherland D, Hiromi Y, Krasnow MA. sprouty encodes a novel antagonist of FGF signaling that patterns apical branching of the Drosophila airways. Cell. 1998;92:253–263. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80919-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada H, Toyono T, Toyoshima K, Yamasaki M, Itoh N, Kato S, Sekine K, Ohuchi H. FGF10 maintains stem cell compartment in developing mouse incisors. Development. 2002;129:1533–1541. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.6.1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haycraft CJ, Banizs B, Aydin-Son Y, Zhang Q, Michaud EJ, Yoder BK. Gli2 and Gli3 localize to cilia and require the intraflagellar transport protein polaris for processing and function. PLoS Genet. 2005;1:e53. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huangfu D, Anderson KV. Cilia and Hedgehog responsiveness in the mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:11325–11330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505328102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kangas AT, Evans AR, Thesleff I, Jernvall J. Nonindependence of mammalian dental characters. Nature. 2004;432:211–214. doi: 10.1038/nature02927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassai Y, Munne P, Hotta Y, Penttila E, Kavanagh K, Ohbayashi N, Takada S, Thesleff I, Jernvall J, Itoh N. Regulation of mammalian tooth cusp patterning by ectodin. Science. 2005;309:2067–2070. doi: 10.1126/science.1116848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettunen P, Karavanova I, Thesleff I. Responsiveness of developing dental tissues to fibroblast growth factors: expression of splicing alternatives of FGFR1, -2, -3, and of FGFR4; and stimulation of cell proliferation by FGF-2, -4, -8, and -9. Dev Genet. 1998;22:374–385. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6408(1998)22:4<374::AID-DVG7>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettunen P, Laurikkala J, Itaranta P, Vainio S, Itoh N, Thesleff I. Associations of FGF-3 and FGF-10 with signaling networks regulating tooth morphogenesis. Dev Dyn. 2000;219:322–332. doi: 10.1002/1097-0177(2000)9999:9999<::AID-DVDY1062>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, Bar-Sagi D. Modulation of signalling by Sprouty: a developing story. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:441–450. doi: 10.1038/nrm1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer S, Okabe M, Hacohen N, Krasnow MA, Hiromi Y. Sprouty: a common antagonist of FGF and EGF signaling pathways in Drosophila. Development. 1999;126:2515–2525. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.11.2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kratochwil K, Galceran J, Tontsch S, Roth W, Grosschedl R. FGF4, a direct target of LEF1 and Wnt signaling, can rescue the arrest of tooth organogenesis in Lef1(−/−) mice. Genes Dev. 2002;16:3173–3185. doi: 10.1101/gad.1035602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesot H, Vonesch JL, Peterka M, Tureckova J, Peterkova R, Ruch JV. Mouse molar morphogenesis revisited by three-dimensional reconstruction. II. Spatial distribution of mitoses and apoptosis in cap to bell staged first and second upper molar teeth. Int J Dev Biol. 1996;40:1017–1031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewandoski M, Sun X, Martin GR. Fgf8 signalling from the AER is essential for normal limb development. Nat Genet. 2000;26:460–463. doi: 10.1038/82609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason JM, Morrison DJ, Basson MA, Licht JD. Sprouty proteins: multifaceted negative-feedback regulators of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min H, Danilenko DM, Scully SA, Bolon B, Ring BD, Tarpley JE, DeRose M, Simonet WS. Fgf-10 is required for both limb and lung development and exhibits striking functional similarity to Drosophila branchless. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3156–3161. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.20.3156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minowada G, Jarvis LA, Chi CL, Neubuser A, Sun X, Hacohen N, Krasnow MA, Martin GR. Vertebrate Sprouty genes are induced by FGF signaling and can cause chondrodysplasia when overexpressed. Development. 1999;126:4465–4475. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.20.4465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustonen T, Pispa J, Mikkola ML, Pummila M, Kangas AT, Pakkasjarvi L, Jaatinen R, Thesleff I. Stimulation of ectodermal organ development by Ectodysplasin-A1. Dev Biol. 2003;259:123–136. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00157-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neubuser A, Peters H, Balling R, Martin GR. Antagonistic interactions between FGF and BMP signaling pathways: a mechanism for positioning the sites of tooth formation. Cell. 1997;90:247–255. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80333-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Hagan RC, Hassell JA. The PEA3 Ets transcription factor is a downstream target of the HER2/Neu receptor tyrosine kinase. Oncogene. 1998;16:301–310. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterkova R, Peterka M, Viriot L, Lesot H. Development of the vestigial tooth primordia as part of mouse odontogenesis. Connect Tissue Res. 2002;43:120–128. doi: 10.1080/03008200290000745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich A, Sapir A, Shilo B. Sprouty is a general inhibitor of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling. Development. 1999;126:4139–4147. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.18.4139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez CI, Buchholz F, Galloway J, Sequerra R, Kasper J, Ayala R, Stewart AF, Dymecki SM. High-efficiency deleter mice show that FLPe is an alternative to Cre-loxP. Nat Genet. 2000;25:139–140. doi: 10.1038/75973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roehl H, Nusslein-Volhard C. Zebrafish pea3 and erm are general targets of FGF8 signaling. Curr Biol. 2001;11:503–507. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim K, Minowada G, Coling DE, Martin GR. Sprouty2, a mouse deafness gene, regulates cell fate decisions in the auditory sensory epithelium by antagonizing FGF signaling. Dev Cell. 2005;8:553–564. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Lewandoski M, Meyers EN, Liu YH, Maxson RE, Jr, Martin GR. Conditional inactivation of Fgf4 reveals complexity of signalling during limb bud development. Nat Genet. 2000;25:83–86. doi: 10.1038/75644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thesleff I, Keranen S, Jernvall J. Enamel knots as signaling centers linking tooth morphogenesis and odontoblast differentiation. Adv Dent Res. 2001;15:14–18. doi: 10.1177/08959374010150010401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thisse B, Thisse C. Functions and regulations of fibroblast growth factor signaling during embryonic development. Dev Biol. 2005;287:390–402. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trokovic R, Trokovic N, Hernesniemi S, Pirvola U, Vogt Weisenhorn DM, Rossant J, McMahon AP, Wurst W, Partanen J. FGFR1 is independently required in both developing mid- and hindbrain for sustained response to isthmic signals. EMBO J. 2003;22:1811–1823. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker A, Sharpe P. The cutting-edge of mammalian development; how the embryo makes teeth. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:499–508. doi: 10.1038/nrg1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaahtokari A, Aberg T, Jernvall J, Keranen S, Thesleff I. The enamel knot as a signaling center in the developing mouse tooth. Mech Dev. 1996;54:39–43. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(95)00459-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu K, Xu J, Liu Z, Sosic D, Shao J, Olson EN, Towler DA, Ornitz DM. Conditional inactivation of FGF receptor 2 reveals an essential role for FGF signaling in the regulation of osteoblast function and bone growth. Development. 2003;130:3063–3074. doi: 10.1242/dev.00491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Lin Y, Itaranta P, Yagi A, Vainio S. Expression of Sprouty genes 1, 2 and 4 during mouse organogenesis. Mech Dev. 2001;109:367–370. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00526-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Murcia NS, Chittenden LR, Richards WG, Michaud EJ, Woychik RP, Yoder BK. Loss of the Tg737 protein results in skeletal patterning defects. Dev Dyn. 2003;227:78–90. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]