Abstract

Objective: To measure the health of a representative sample of the population of the United Kingdom by using the EuroQoL EQ-5D questionnaire.

Design: Stratified random sample representative of the general population aged 18 and over and living in the community.

Setting: United Kingdom.

Subjects: 3395 people resident in the United Kingdom.

Main outcome measures: Average values for mobility, self care, usual activities, pain or discomfort, and anxiety or depression.

Results: One in three respondents reported problems with pain or discomfort. There were differences in the perception of health according to the respondent’s age, social class, education, housing tenure, economic position, and smoking behaviour.

Conclusions: The EQ-5D questionnaire is a practical way of measuring the health of a population and of detecting differences in subgroups of the population.

Key messages

Measurement of health outcome requires the observation of states of health

Patients’ involvement in recording and assessing their own state of health is a major element in the process of evaluating the impact of health care

The EuroQoL EQ-5D questionnaire highlights variations in states of health which are consistent with previously published results

High degrees of pain are reported in the general population. A category for pain is absent and thus undetected in the survey of disability by the Office of Population Censuses and Surveys

Introduction

The measurement of health is central to the evaluation of health care. By observing the extent of changes in health the benefits and disbenefits of health care for both patients and groups of patients can be evaluated; over the past 25 years several generic measures of health have been developed for use in this way.1–8 These instruments were designed for use as general purpose measures of health, independent of diagnostic categorisation or disease severity. Information based on such measures is useful for establishing the degrees of morbidity in the community, enabling different population subgroups to be compared, which would help in assessing health needs or in informing those responsible for allocating health resources. Periodic reassessment of health could provide important data on the extent of any changes in the health of a population—for example, the extent to which the population is achieving national targets for health. If such standardised information was also routinely collected on individual patients it would provide a simple means of evaluating the outcomes of their health care.

We report on a study in which the EuroQoL EQ-5D questionnaire9 was fielded in a survey of the population of the United Kingdom, conducted as part of a wider study of practical ways of measuring health related quality of life.10

Subjects and methods

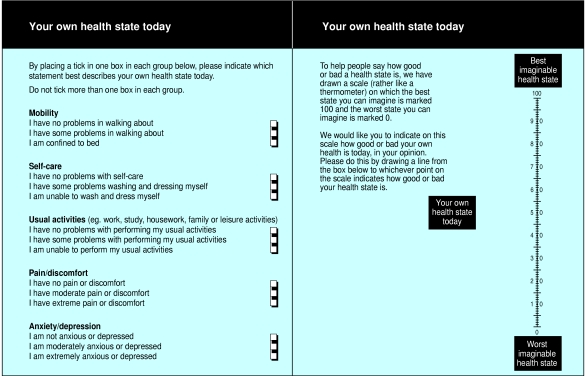

EQ-5D questionnaire

The EQ-5D questionnaire is a generic measure of health status developed by the EuroQoL Group, an international research network established in 1987 by researchers from Finland, the Netherlands, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. The EQ-5D questionnaire defines health in terms of five dimensions: mobility, self care, usual activities (work, study, housework, family, or leisure), pain or discomfort, and anxiety or depression. Each dimension is subdivided into three categories, which indicate whether the respondent has no problem, a moderate problem, or an extreme problem (appendix). Combinations of these categories define a total of 243 health states. The EQ-5D questionnaire comprises two pages; on the first page respondents record the extent of their problem in each of the five dimensions and on the second page they record their perception of their overall health on a visual analogue scale (0 denoting the worst imaginable health state and 100 denoting the best imaginable health state). The validity and reliability of the EQ-5D questionnaire have been tested,11–13 as has its application in a range of patient groups.14–16 Since the original survey reported here, the EQ-5D questionnaire has been fielded in three national surveys, including the English national health survey—an interview-based survey of about 16 000 people. The EQ-5D questionnaire has also been used in population surveys in Spain, Germany, and Canada.

Survey design and methods

Members of the public aged 18 and over were interviewed as part of a national survey. No upper age limit was stipulated. The sample was based on addresses in England, Scotland, and Wales, selected by postcode.17 Eighty postcode areas were chosen, proportionately to the number of addresses in each area, after these areas had been stratified by regional health authority, socioeconomic group, and population density. Seventy six addresses were selected from each postcode area, yielding a total of 6080 addresses. At each of these addresses one adult aged 18 or over was selected using a Kish grid.18 Individuals in institutions, hostels, care homes, or bed and breakfast accommodation were excluded from the sample. Of the selected addresses, 12% were unproductive as they were non-residential, empty, or untraceable. The final sample comprising 3395 subjects was representative of the general population with respect to age, sex, and social class. During the interview, respondents completed the EQ-5D questionnaire and provided information on age, sex, marital state, education, employment, housing tenure, and smoking behaviour. The interviews took place during the last quarter of 1993.

Analysis mainly compared the differences between the population subgroups. It was hypothesised that more health problems would be reported with increasing age, with lower social class, for those registered sick or disabled, and for smokers. χ2 Tests were used for the analysis of the descriptive profile data, and Student’s t test was used to test for subgroup differences in the visual analogue scale data.

Results

A moderate problem on at least one dimension was reported by 42% of respondents, whereas only 6% of respondents reported any extreme problem (table 1). Problems were most often recorded in the pain or discomfort dimension. In subsequent analyses, moderate and extreme categories of each dimension were combined.

Table 1.

Numbers (percentages) of respondents reporting a problem in each EuroQoL dimension

| EuroQoL dimension | Problem

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate | Extreme | Any | |

| Mobility | 620 (18.3) | 3 (0.1) | 623 (18.4) |

| Self care | 139 (4.1) | 5 (0.1) | 144 (4.2) |

| Usual activities | 481 (14.2) | 70 (2.1) | 551 (16.3) |

| Pain/discomfort | 988 (29.2) | 129 (3.8) | 1117 (33.0) |

| Anxiety/depression | 648 (19.1) | 62 (1.8) | 710 (20.9) |

| Any dimensions* | 1441 (42.4) | 212 (6.2) | 1456 (43.1) |

Although row totals within dimension are internally consistent, there is apparent anomaly in the final row. 1441 respondents reported a moderate problem in at least one dimension and 212 reported an extreme problem; these two dimensions are not mutually exclusive as respondents may have reported an extreme problem in one dimension, with no intermediate level of problem being reported for remaining dimension. Hence total of 1456 does not equate to addition of two previous table entries.

The mean state of health recorded on the visual analogue scale was 82.5 (SD 17).

Health and age

The rates of reported problems increased significantly with age (P<0.001) for all dimensions (table 2); an exception to this general pattern was the anxiety/depression dimension, which peaked at 28% of respondents aged 60 to 69 and then decreased slightly.

Table 2.

Numbers (percentages) of respondents reporting any problem, by age group and sex

| EuroQoL dimension | Age group (years)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20-29 | 30-39 | 40-49 | 50-59 | 60-69 | 70-79 | ⩾80 | |

| Mobility | |||||||

| All respondents | 31 (5.0) | 53 (7.8) | 56 (10.3) | 101 (21.9) | 140 (29.3) | 162 (39.8) | 80 (56.7) |

| Men | 15 (5.7) | 24 (8.0) | 23 (9.3) | 53 (25.9) | 73 (34.6) | 57 (33.5) | 21 (45.7) |

| Women | 16 (4.5) | 29 (7.6) | 33 (11.1) | 48 (18.7) | 67 (25.1) | 105 (44.3) | 59 (62.1) |

| Self care | |||||||

| All respondents | 6 (1.0) | 11 (1.6) | 23 (4.2) | 24 (5.2) | 27 (5.7) | 30 (7.4) | 23 (16.3) |

| Men | 3 (1.1) | 6 (2.0) | 10 (4.0) | 13 (6.3) | 15 (7.1) | 13 (7.6) | 5 (10.9) |

| Women | 3 (0.8) | 5 (1.3) | 13 (4.4) | 11 (4.3) | 12 (4.5) | 17 (7.2) | 18 (18.9) |

| Usual activity | |||||||

| All respondents | 44 (7.1) | 59 (8.6) | 59 (10.8) | 101 (21.9) | 118 (24.7) | 107 (26.3) | 62 (44.0) |

| Men | 23 (8.7) | 22 (7.3) | 23 (9.3) | 51 (25.0) | 61 (28.9) | 42 (24.7) | 19 (41.3) |

| Women | 21 (5.9) | 37 (9.7) | 36 (12.1) | 50 (19.4) | 57 (21.4) | 65 (27.4) | 43 (45.3) |

| Pain/discomfort | |||||||

| All respondents | 98 (15.8) | 132 (19.3) | 141 (25.9) | 202 (43.7) | 221 (46.2) | 228 (56.0) | 85 (60.3) |

| Men | 39 (14.8) | 56 (18.7) | 59 (24.0) | 85 (41.5) | 105 (49.8) | 86 (50.6) | 25 (54.3) |

| Women | 59 (16.6) | 76 (19.8) | 82 (27.5) | 117 (45.5) | 116 (43.4) | 142 (59.9) | 60 (63.2) |

| Anxiety/depression | |||||||

| All respondents | 83 (13.4) | 119 (17.4) | 102 (18.7) | 126 (27.2) | 134 (28.0) | 103 (25.3) | 35 (24.8) |

| Men | 27 (10.2) | 46 (15.3) | 39 (15.8) | 53 (25.9) | 54 (25.6) | 29 (17.1) | 8 (17.4) |

| Women | 56 (15.8) | 73 (19.1) | 63 (21.1) | 73 (28.3) | 80 (30.0) | 74 (31.2) | 27 (28.4) |

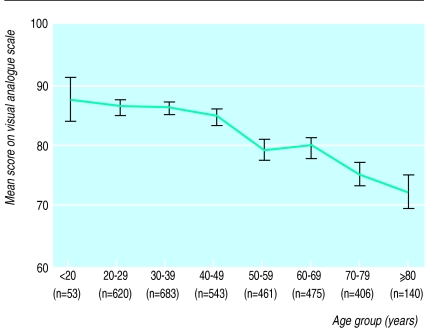

Figure 1 shows the mean visual analogue scale values for each age group and the 95% confidence interval. The mean value decreased from about 87 in the youngest age group to 72 in the oldest age group. Mean values did not differ significantly in the 20 to 49 age range but decreased significantly for respondents aged ⩾50 (P<0.001).

Figure 1.

Mean self rated health status of respondents

Health and sex

Women aged ⩾70 tended to report higher rates of problems than did men of the same age (table 2). A systematic difference in rates was found across all age groups on the anxiety/depression dimension, with women reporting significantly higher rates than men (P<0.05). No significant differences were found in the visual analogue scale scores for men and women.

Health and marital status

Respondents who were widowed, separated, or divorced reported significantly more problems on all five dimensions (P<0.001). Scores on the visual analogue scale for this group were also significantly lower than for respondents living alone or for those with a partner (means 77, 84, and 84 respectively, P<0.001).

Health and social class

After the effects of age were controlled for, there were significant differences in the rates of reported problems when respondents were grouped according to social class (table 3).

Table 3.

Numbers (percentages) of respondents reporting any problem, by age group and social class (based on respondent’s own current or most recent occupation as classified by registrar general)

| EuroQoL dimension | Age group (years)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20-29 | 30-39 | 40-49 | 50-59 | 60-69 | 70-79 | ⩾80 | |

| Mobility | |||||||

| Social class: | |||||||

| I and II | 6 (3.6) | 18 (7.6) | 15 (7.6) | 17 (14.3) | 42 (28.4) | 24 (29.6) | 11 (47.8) |

| III | 12 (4.4) | 21 (7.3) | 26 (11.8) | 47 (23.5) | 56 (26.7) | 80 (39.8) | 36 (57.1) |

| IV and V | 11 (7.7) | 9 (6.3) | 15 (12.4) | 36 (26.5) | 40 (36.7) | 52 (46.4) | 28 (59.6) |

| Self care | |||||||

| Social class: | |||||||

| I and II | 1 (0.6) | 4 (1.7) | 7 (3.5) | 5 (4.2) | 7 (4.8) | 3 (3.7) | 3 (13.0) |

| III | 2 (0.7) | 4 (1.4) | 10 (4.5) | 10 (5.0) | 12 (5.7) | 17 (8.5) | 7 (11.8) |

| IV and V | 2 (1.4) | 2 (1.4) | 6 (5.0) | 9 (6.7) | 7 (6.4) | 10 (8.9) | 11 (23.4) |

| Usual activities | |||||||

| Social class: | |||||||

| I and II | 11 (6.5) | 16 (6.8) | 19 (9.6) | 17 (14.3) | 37 (25.0) | 19 (23.5) | 8 (34.8) |

| III | 16 (5.9) | 20 (7.0) | 23 (10.4) | 45 (22.5) | 46 (21.9) | 54 (26.9) | 28 (44.4) |

| IV and V | 13 (9.1) | 18 (12.6) | 16 (13.2) | 38 (27.9) | 32 (29.6) | 32 (28.6) | 21 (44.7) |

| Pain/discomfort | |||||||

| Social class: | |||||||

| I and II | 24 (14.3) | 39 (16.5) | 38 (19.2) | 33 (27.7) | 62 (41.9) | 36 (44.4) | 9 (39.1) |

| III | 42 (15.6) | 45 (15.7) | 69 (31.4) | 98 (49.0) | 93 (44.3) | 111 (55.2) | 43 (68.3) |

| IV and V | 26 (18.2) | 41 (28.7) | 33 (27.3) | 69 (50.7) | 62 (56.9) | 77 (68.8) | 29 (61.7) |

| Anxiety/depression | |||||||

| Social class: | |||||||

| I and II | 15 (8.9) | 37 (15.6) | 31 (15.7) | 25 (21.0) | 28 (18.9) | 14 (17.3) | 6 (26.1) |

| III | 36 (13.3) | 47 (16.4) | 41 (18.6) | 59 (29.4) | 58 (27.6) | 55 (27.4) | 13 (20.6) |

| IV and V | 25 (17.5) | 33 (23.1) | 29 (24.0) | 39 (28.7) | 45 (41.3) | 31 (27.7) | 14 (29.8) |

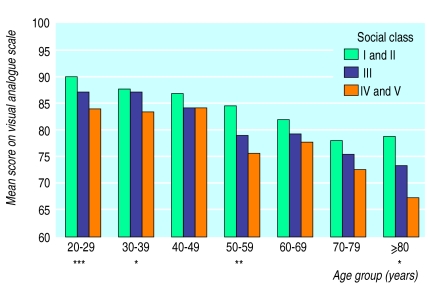

Rates of reported problems from respondents in social classes III and IV were between 20% and 120% higher than rates in respondents from social classes I and II; the largest differences were for the pain/discomfort (P<0.01) and anxiety/depression (P<0.01) dimensions. Rates did not differ significantly for the mobility and self care dimensions. Figure 2 shows that respondents from social classes I and II had consistently higher levels of reported health as measured by the visual analogue scale than respondents from the two other social classes. Respondents from social classes I and II had a 5 point advantage on the visual analogue scale over respondents from social classes IV and V of the same age group. The difference was significant for all age groups except for respondents aged 40 to 49 years. The mean scores on the visual analogue scale for respondents from social classes I and II remained above the level of the youngest respondents from social classes IV and V until the 50 to 59 age group.

Figure 2.

Effect of social class on self rated health status. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001

Health and education

When respondents were classified by education rather than by social class, a similar pattern of differences emerged. Respondents who had received higher or further education reported significantly lower rates of problems with mobility (P<0.05), usual activities (P<0.05), pain/discomfort (P<0.01), and anxiety/depression (P<0.01) than did those who had received no education after leaving school. A similar pattern was seen on the visual analogue scale, with significantly higher scores reported for those who had received higher or further education (P<0.001).

Health and economic status

Significantly higher rates of problems were reported by respondents who were unemployed, sick or disabled, or retired, compared with those in employment or full time education (P<0.001) (table 4). Rates of reported problems for unemployed people were almost twice those of respondents in a salaried job.

Table 4.

Numbers (percentages) of respondents reporting problems, by employment

| EuroQoL dimension

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment | No of respondents | Mobility | Self care | Usual activities | Pain/discomfort | Anxiety/depression |

| Studying | 92 | 5 (5.4) | 1 (1.1) | 8 (8.7) | 20 (21.7) | 15 (16.3) |

| Salaried job | 1636 | 106 (6.5) | 11 (0.7) | 109 (6.7) | 337 (20.6) | 223 (13.6) |

| Unemployed | 196 | 24 (12.2) | 5 (2.6) | 21 (10.7) | 53 (27.0) | 52 (26.5) |

| Sick or disabled | 128 | 101 (78.9) | 48 (37.5) | 110 (85.3) | 112 (86.8) | 79 (61.2) |

| Retired | 761 | 280 (36.8) | 53 (7.0) | 211 (27.7) | 393 (51.6) | 186 (24.4) |

| Looking after home | 524 | 93 (17.7) | 23 (4.4) | 79 (15.1) | 179 (34.2) | 138 (26.3) |

The table excludes 45 respondents whose employment was classed as other and 12 respondents whose details were missing.

When respondents were grouped according to housing tenure, significantly higher rates of problems were recorded on all the dimensions for those living in rented property compared with owner occupiers.

The mean scores on the visual analogue scale of people in work or of people who were studying was significantly higher than for people who were unemployed (87.5 and 82.0 respectively, P<0.001). Similarly, the scores of owner occupiers were significantly higher than for people who rented their accommodation (85.1 and 77.2 respectively, P<0.001).

Health and smoking behaviour

Respondents who smoked reported significantly higher rates of problems than non-smokers on all dimensions. Non-smokers also recorded significantly higher scores on the visual analogue scale than respondents who smoked (83.4 and 80.4 respectively, P<0.001).

Analysis of variance

Analysis of variance was used to investigate the collective influence of background variables. With the score on the visual analogue scale as the dependent variable and age as a covariate, a main effects model indicated a significant contribution for education (P<0.01), employment (P<0.001), and smoking behaviour (P<0.001). Housing tenure, marital status, and social class were not significant variables in this model.

Disability rates from other national surveys

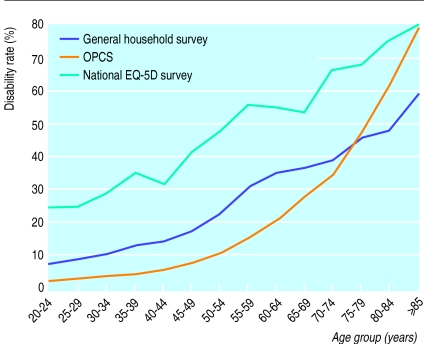

Respondents who reported any problem in any dimension could be distinguished from respondents who reported no problems whatsoever. This dichotomy can be used to form an arbitrary definition of disability, enabling data to be compared with the findings of other surveys. The general household survey incorporates questions on longstanding illness and recent interference with usual activities.19 The responses to these questions are combined to give rates of limiting longstanding illness which are published annually. The disability survey by the Office of Population Censuses and Surveys conducted in 1985 included a questionnaire comprising 10 categories: locomotion, reaching and stretching, dexterity, seeing, hearing, personal care, continence, communication, behaviour, and intellectual functioning.20 The rates of disability in people grouped into five year age groups were reported in this survey.20 These data were plotted against disability rates determined from our survey (fig 3). Disability rates based on responses to the EQ-5D questionnaire were 20% to 25% higher than rates from the general household survey for all age groups and about 30% to 40% higher than the 1985 disability survey, until the age of 80.

Figure 3.

Disability rates from three national surveys

Discussion

This survey provides an important insight into the health status of the population of the United Kingdom at any one time. Although extreme problems with mobility and self care were rarely reported in this survey, there was a high level of reported problems with pain or discomfort. Over 50% of respondents aged ⩾70 and about 20% of the youngest respondents reported some problem in this dimension. This finding has important implications. Pain does not seem to be a dimension of interest in a national disability survey despite being widely experienced in the community. The omission of a pain category means that it is assigned a zero weight, despite good evidence that it has a powerful influence on society’s valuations of states of health.21 These factors combine to disadvantage a significant proportion of the general population.

Significant differences were found between population subgroups with respect to age, social class, marital status, employment, education, and smoking behaviour. These findings compare with findings reported elsewhere.22–24 Disability rates based on the EuroQoL classification reflected similar trends to those seen in the general household survey and surveys of the Office of Population Censuses and Surveys, although rates in these surveys were somewhat lower as they were based on a narrower definition of disability.

Population averages

The representativeness of the survey suggests that the results are indicative of the average health status in the general population of the United Kingdom, although it should be borne in mind that sampling was limited to individuals living in the community and tended to exclude people who had extreme problems with mobility or with self care and therefore likely to be dependent on others for their daily needs. Current investigation of specific patient groups—for example, people attending their general practice surgeries—reveals a wider distribution of reported problems. Thus, to the extent that this survey excluded people who were likely to yield responses indicating more severe problems, the results may well underestimate the health related quality of life of the general population.

Our data can be treated as descriptive population “norms.” As such, they could provide baseline values for monitoring variations in health for specific population groups, particularly if this information was also linked to local epidemiological data. In aggregate form, such information could be used to complement national targets by providing a measure based on health status rather than mortality. The capacity of the EQ-5D questionnaire to generate quantifiable and usable information on the health status of a population led to its inclusion in the 1996 health survey for England.25

Measuring outcomes

However, it is the measurement of change in health status for which the need is greatest. There can be few circumstances in which healthcare workers are not concerned with the measurement of outcome, and the EQ-5D questionnaire provides the capacity to measure change in health status, and hence outcomes, in a simple standardised way. The information on self reported problems recorded on the first page of the EQ-5D questionnaire identifies a unique health status for which there is a corresponding index value based on the views of the general population.21 Changes in health status and the value of that change can be used to quantify outcomes for clinical and economic evaluation; the latter role was recommended for the EQ-5D questionnaire in a report commissioned by the United States Department of Public Health.26 There is “an increasing consensus regarding the centrality of the patient’s point of view in monitoring medical care outcomes,”6 and the EQ-5D questionnaire has the obvious potential to contribute to that process. The national survey data reported in this paper show what can be achieved by using an uncomplicated instrument for measuring health status. The further exploitation of its potential is open to us all.

Figure.

Appendix

EQ-5D questionnaire

Acknowledgments

Survey work for the 1993 survey was conducted by Social and Community Planning Research, and we thank the trained fieldwork staff for their help in the collection of the data.

Footnotes

Funding: The project was funded by the Department of Health. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily of the Department of Health.

Conflict of interest: None.

References

- 1.Patrick DL, Bush JW, Chen MM. Methods for measuring levels of well-being for a health status index. Health Serv Res. 1973;11:516. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosser RM, Watts V. The measurement of hospital output. Int J Epidemiol. 1972;1:361–368. doi: 10.1093/ije/1.4.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergner M, Bobbitt RA, Kressel S, Pollard WE, Gilson BS, Morris JR. The sickness impact profile: conceptual formulation and methodology for the development of a health status measure. Int J Health Serv. 1976;6:393–415. doi: 10.2190/RHE0-GGH4-410W-LA17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hunt SM, McKenna SP, McEwen J, Backett EM, Williams J, Papp E. A quantitative approach to perceived health status: a validation study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1980;34:281–286. doi: 10.1136/jech.34.4.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Torrance GW, Furlong W, Feeny D, Boyle M. Multi-attribute preference functions. Pharmacoeconomics. 1995;7:503–520. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199507060-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sintonen H. An approach to measuring and valuing health states. Soc Sci Med. 1981;15:55–65. doi: 10.1016/0160-7995(81)90019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.EuroQoL Group. EuroQoL—a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16:199–208. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brooks RG. EuroQoL—the current state of play. Health Policy. 1996;37:53–72. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(96)00822-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams AH. The measurement and valuation of health: a chronicle. University of York: Centre for Health Economics; 1995. (Discussion paper 136.) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brazier J, Jones N, Kind P. Testing the validity of the EuroQoL and comparing it with the SF-36 health survey questionnaire. Qual Life Res. 1993;2:169–180. doi: 10.1007/BF00435221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Agt H, Essink-Bot M-L, Krabbe P, Bonsel G. Test-retest reliability of health state valuations collected with the EuroQoL questionnaire. Soc Sci Med. 1994;39:1537–1544. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Essink-Bot M-L, Krabbe P, Bonsel G, Aaronson N. An empirical comparison of four generic health status measures: the Nottingham health profile, the medical outcomes study 36-item short-form health survey, the COOP/WONCA charts, and the EuroQoL Instrument. Med Care. 1997;35:522–537. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199705000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hurst NP, Jobanputra P, Hunter M, Lambert M, Lochead A, Brown H. Validity of EuroQoL—a generic health status instrument—in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol. 1994;33:655–662. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/33.7.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sculpher M, Dwyer N, Byford S, Stirrat G. Randomised trial comparing hysterectomy and transcervical endometrial resection: effect on health related quality of life and costs two years after surgery. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1996;103:142–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1996.tb09666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hollingworth W, Mackenzie R, Todd CJ, Dixon AK. Measuring changes in quality of life following magnetic resonance imaging of the knee: SF-36, EuroQoL or Rosser index? Qual Life Res. 1995;4:325–334. doi: 10.1007/BF01593885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Erens B. Health-related quality of life: general population survey. London: Social and Community Planning Research; 1994. (Technical report.) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kish L. Survey sampling. New York: Wiley; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomas M, Goddard E, Hickman M, Hunter P. The general household survey 1992. London: HMSO; 1994. (OPCS Series GHS No 23.) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin J, Letzer H, Elliot D. The prevalence of disability among adults. OPCS surveys of disability in Great Britain. Report 1. London: HMSO, 1988.

- 21.Dolan P, Gudex C, Kind P, Williams A. A social tariff for EuroQoL: results from a UK general population survey. University of York: Centre for Health Economics; 1995. (Discussion paper 138.) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Department of Health and Social Security. Prevention and health: everybody’s business. A reassessment of public and personal health. London: HMSO; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Black D, Morris JN, Smith C, Townsend P. Black Report. Inequalities in health: report of a research working group. London: Department of Health and Social Security, 1980.

- 24.Rahkonen O, Arber S, Lahelma E. Health inequalities in early adulthood: a comparison of young men and women in Britain and Finland. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41:163–171. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00320-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prescott-Clarke P, Primatesta P, editors. Health survey for England, 1996. London: Stationery Office; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weinstein MC, Siegel JE, Gold MR, Kamlet MS, Russell LB. Recommendations of the panel on cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. JAMA. 1996;276:1253–1258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]