Abstract

The conjugation of Halteria grandinella was studied in protargol preparations. The isogamontic conjugants fuse partially with their ventral sides to a homopolar pair. The first maturation division generates dramatic transformations: (i) the partners obtain an interlocking arrangement; (ii) the number of bristle kineties decreases from seven to four in each partner; and (iii) the right conjugant loses its buccal membranelles, the left the whole adoral zone. The remaining collar membranelles arrange around the pair’s anterior end and are shared by both partners; finally, the couple resembles a vegetative specimen in size and outline. The vegetative macronucleus fragments before pycnosis. The micronucleus performs three maturation divisions, but only one derivative each performs the second and third division. The synkaryon divides twice, producing a micronucleus, a macronucleus anlage, and two disintegrating derivatives. Scattered somatic kinetids occur during conjugation, but disappear without reorganization. An incomplete oral primordium originates in both partners. The conjugation of Halteria grandinella resembles in several respects that of hypotrich spirotrichs; however, the majority of morphological, ontogenetical, and ultrastructural features still indicates an affiliation with the oligotrich and choreotrich spirotrichs. Accordingly, the cladistic analysis still contradicts the genealogy based on the sequences of the small subunit rRNA gene.

Keywords: Ciliary pattern, Conjugation, Hypotrichs, Oligotrichs, Phylogeny, Halteria

Introduction

Although conjugation was quite often studied in euplotids and hypotrichs, the investigations usually concentrated on the nuclear events and the reorganization of the ventral ciliature. Only one study describes conjugation in choreotrichs (Ota and Taniguchi 2003), and data about oligotrichs and halteriids are restricted to anecdotal observations on live or preserved specimens (Buddenbrock 1920; Gourret and Roeser 1888; Leegaard 1915; Montagnes and Humphrey 1998; Penard 1916; Szabó 1934; Tamar 1974). Hence, the conjugation of a halteriid ciliate, viz., the widely distributed Halteria grandinella (Müller, 1773) Dujardin, 1841, is described in the present paper.

The morphology, ontogenesis, and ultrastructure of halteriids indicate an affiliation with the oligotrich and choreotrich ciliates (Agatha 2004; Agatha and Strüder-Kypke 2007; Foissner et al. 2007), while the sequence of the small subunit ribosomal RNA (SSrRNA) gene assigns the halteriids to the hypotrichs, i.e., H. grandinella is the adelphotaxon of Oxytricha granulifera (Agatha and Strüder-Kypke 2007; Shin et al. 2000). Therefore, an attempt is made to reconcile the classical and molecular genealogies by including the new conjugation features into the cladistic analysis.

Materials and methods

Substrate samples were taken between June and October 1991 in the River Amper, an outlet of the Ammersee (Lake Ammer) near Munich, Southern Germany. Halteria specimens were isolated from the raw cultures and cultivated in Eau de Volvic enriched with some squashed wheat grains to stimulate growth of bacteria, viz., the main food of H. grandinella. Spontaneous mass conjugation occurred after a developmental peak. Protargol impregnation followed protocol A in Foissner (1991). Counts and measurements were performed at × 1000 magnification and refer to only one mate if not stated otherwise. The illustrations were made with a drawing device. The conjugation events were reconstructed from the protargol preparations, which show the ciliary pattern and nuclear apparatus usually very well. The various macronucleus and micronucleus stages are distinguished by their shapes and different affinities to protargol. Since the nuclear phenomena were normal (Raikov 1972) and the conjugation took place in a rather young, flourishing culture, the events observed probably represent the common pattern in Halteria. The duration of the phases could not be estimated. The slides were deposited in the Biology Centre of the Museum of Upper Austria (LI) in A-4040 Linz, Austria, with the relevant specimens/couples marked by black ink circles on the cover glass. Usually, several conjugating couples per stage could be studied (in total 179 pairs were statistically analyzed), whereas the number of exconjugants (n = 8) was insufficient to investigate ciliary and nuclear reconstruction.

Detailed morphometrics were helpful for recognizing the various morphological changes. A summary of these data is presented in Figs 45, 46, while tabulated details are available in an electronic appendix of the paper’s on-line version and a forthcoming monograph on the aloricate oligotrichs. As concerns the vegetative specimens, they are similar to populations described previously (Song and Wilbert 1989), i.e., the prepared cells are about 23 μm across and have seven somatic kineties, 16 or 17 (x̅ = 16) collar membranelles, and seven or eight (x̅ = 7) buccal membranelles (Figs 1–4).

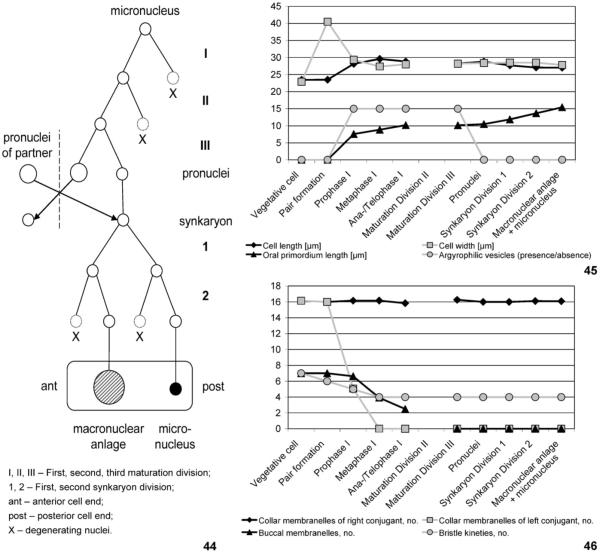

Figs 44–46.

Processes during conjugation of Halteria grandinella. 44. Nuclear events. There are three maturation and two synkaryon divisions, producing one macronucleus anlage (hatched circle) and one micronucleus (filled circle). The arrangement of the derivatives (open circles) mainly follows the pattern observed in the conjugants, i.e., the conjugant’s anterior cell end is on the left side of the scheme and the posterior end on the right. 45, 46. Transformations of conjugants. The most dramatic events take place during the prophase and metaphase of the first maturation division: the couple’s length increases, the couple’s width decreases, oral primordia originate, argyrophilic vesicles appear, the buccal membranelles of both conjugants disintegrate, the collar membranelles of the left conjugant disintegrate, and the number of bristle kineties is reduced from seven to four in each partner. Note that we probably missed the second maturation division.

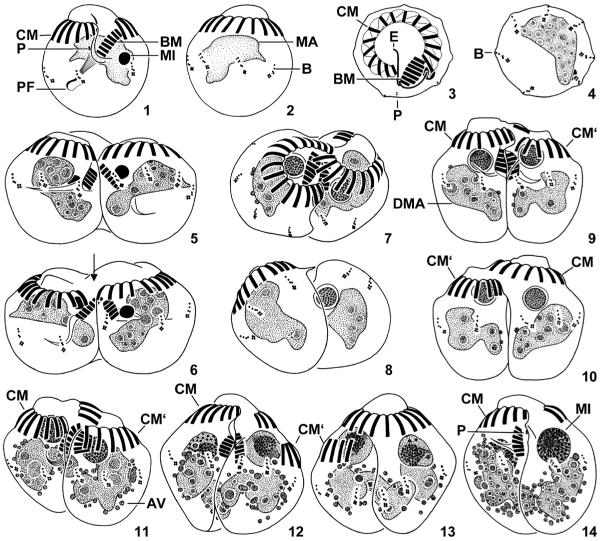

Figs 1–14.

Halteria grandinella, vegetative specimens (1–4) and conjugants during first maturation division (5–14) after protargol impregnation. 1, 2. Ventral and dorsal view. 3, 4. Top and posterior polar view. 5, 6. Pair formation. Arrow marks cytoplasmic bridge between partners. 7, 8. Oblique top and posterior polar view of pair showing the interlocking arrangement of conjugants. 9–14. Ventral (9, 11, 12, 14) and dorsal (10, 13) view of pairs during prophase stage 1 (9, 10), stage 2 (11), stage 3 (12, 13), and stage 4 (14). The left partner is slightly shifted posteriorly and loses its collar membranelles. AV – argyrophilic vesicles, B – bristle kineties, BM – buccal membranelles, CM – collar membranelles of vegetative cell or right conjugant, CM‘ – collar membranelles of left conjugant, DMA – degenerating vegetative macronucleus, E – endoral membrane, MA – macronucleus, MI – micronucleus, P – paroral membrane, PF – pharyngeal fibres. Scale bar 10 μm.

Terminology of conjugation follows Corliss (1979), Raikov (1972), and Xu and Foissner (2004), while that of the spirotrichs follows Berger (2006), who maintained the naming of Ehrenberg and Stein, using Euplota Ehrenberg, 1830 (e.g., Euplotes, Uronychia, Aspidisca; now widely named Hypotrichida) and Hypotricha Stein, 1859 (e.g., Oxytricha, Stylonychia; now widely named Stichotrichida). The numbering of the somatic kineties is according to Deroux (1974). A further term needs to be explained: soon after pair formation, one partner is slightly shifted posteriorly in relation to the other; later, it becomes the “left partner” in respect to the gap in the shared portion of the membranellar zone, which is supposed to mark the couple’s “ventral side”.

Results

Pair formation (Figs 5, 6, 45, 46)

Two just formed couples were available, preconjugants were apparently not generated. Conjugants fuse to a homopolar pair, forming a cytoplasmic bridge between their peristomes. Probably, conjugation is isogamontic.

Partners are of same size and shape as vegetative cells, pairs thus about 23 × 41 μm in size. Macronucleus without replication band. Micronucleus separates from macronucleus and migrates into anterior cell half (“early micronuclear migration”; Paulin 1996), about 3 μm across, homogenously and darkly stained. Number of visible bristle kineties reduced from seven to six, i.e., the ventral rows become located in the cleft between the partners and probably disintegrate. Adoral zone of membranelles unchanged, surrounds the about 1 μm high frontal plate. Endoral membrane apparently disintegrates; paroral membrane not recognizable. Pharyngeal fibres present in both partners.

First maturation division – prophase (Figs 7–15, 44–46)

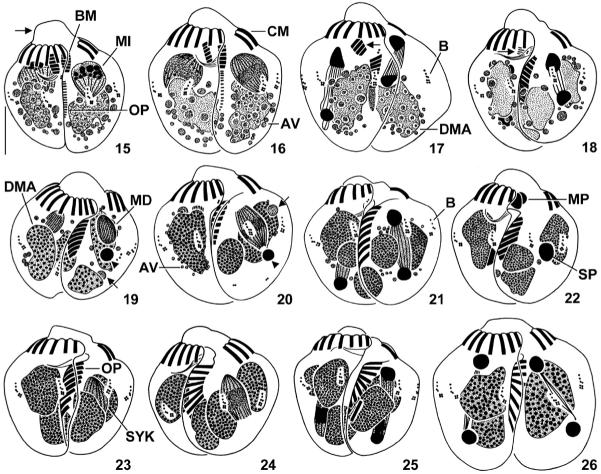

Figs 15–26.

Halteria grandinella, conjugants during first (15–18) and third (19–21) maturation division, reciprocal fertilization (22), and first synkaryon division (23–26) after protargol impregnation. 15. Ventral view of pair during prophase stage 5 (“parachute” stage). Arrow marks elevated frontal plate of peristomial field. The oral primordia commence to develop in the cleft between the conjugants. 16. Ventral view of pair during metaphase. 17, 18. Ventral view of pairs during anaphase and telophase. In both partners, the buccal portion (arrows) of the adoral zone of membranelles starts to degenerate, and the macronucleus has split into usually two fragments (18). 19, 20. Ventral view of pairs during prophase and metaphase. A darkly impregnated pycnotic derivative (arrowheads) is invariably posterior to the dividing derivative, while the position of the faintly impregnated one (arrows) is more variable. The buccal membranelles disappeared in both partners. Note the faintly impregnated granules (probably somatic dikinetids) in the posterior portion of the metaphase couple (20). 21. Ventral view of pair during telophase. 22. Ventral view of pair during exchange of the migratory pronuclei. 23–26. Ventral view of pairs during prophase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase. Note the disappearance of the argyrophilic vesicles and the spreading of the membranelles in the oral primordium. AV – argyrophilic vesicles, B – bristle kineties, BM – buccal membranelles, CM – collar membranelles of right conjugant, DMA – degenerating vegetative macronucleus and its fragments, MD – maturation derivatives, MI – micronucleus derivatives, MP – migratory pronuclei, OP – oral primordium, SP – stationary pronuclei, SYK – synkaryon. Scale bar 10 μm.

Fifty-two couples with an average size of 28 × 29 μm were available. Conjugants ventrally concave and interlocking, i.e., insert left half of ventral side into the partner’s furrow; one partner slightly shifted posteriorly (Figs 7–13). Outline of couples achieves that of vegetative cells, i.e., length:width ratio becomes about 1:1 due to (i) the interlocking arrangement causing a decrease in width by about 10 μm and (ii) an increase in length by about 5 μm partially caused by an elevation of the anterior partner’s frontal plate (Fig. 15). Vegetative macronucleus with slightly irregular surface; nucleoli 1–4 μm across, distinctly reduced in number. Argyrophilic vesicles (possibly autophagosomes) 0.5–3 μm across accumulate around macronucleus and persist until formation of pronuclei (Figs 9–15). Micronucleus in anterior cell half, distinctly inflated, five distinct stages can be distinguished: stage 1 about 6.1 μm across, with a circa 0.5 μm wide bright margin surrounding a densely granular and darkly impregnated centre (Figs 7–10); stage 2 about 6.3 μm across, densely granular and darkly impregnated, contains an eccentric dark spot (Fig. 11); stage 3 about 7.3 μm across, with lightly stained and slightly granular material surrounding a mushroom-shaped structure composed of a darkly impregnated “head” and a slightly brighter “stalk” with a minute chromatic body at the base (Figs 12, 13); stage 4 about 7.8 μm across, with lightly stained material surrounding an eccentric, ellipsoidal, and darkly impregnated structure from which darkly stained strings extend radially (Fig. 14); stage 5 (“parachute” stage; zygotene; Raikov 1972) about 8.4 × 7.8 μm in size, with argyrophilic strings originating from a darkly impregnated granular mass in the broadly rounded nuclear end and converging on a small chromatic body beneath the narrowed nuclear end (Fig. 15). Number of visible bristle kineties further reduced from six to five at beginning (micronucleus stage 1) and from five to four at end (micronucleus stage 5) of prophase, possibly because contact of conjugants becomes more intimate and drives further kineties into the cleft between the partners; no further reduction in number or changes in structure of bristle kineties during the following phases of conjugation. A differential disintegration of the oral ciliature causes a dimorphism of the partners, i.e., the collar membranelles of the more posteriorly located conjugant disintegrate, while the collar membranelles of the anterior conjugant arrange around the pair’s apical end, forming a membranellar zone for both partners; gap of remaining zone portion fixes couple’s ventral and dorsal side as well as right (anterior) and left (posterior) partner. Buccal zone portion reduced by successive disintegration of membranelles, commencing at both ends of zone, shortened by about one third at end of prophase (micronucleus stage 5). Paroral membrane of right conjugant occasionally recognizable until metaphase of second synkaryon division, that of left partner not recognizable. Pharyngeal fibres or funnel present until separation of partners. An oral primordium up to 10 μm long originates as a longitudinally orientated cuneate field of basal bodies simultaneously on ventral side of both partners during micronucleus stages 4 and 5; membranelles immediately differentiate in the primordium’s anterior portion.

First maturation division – metaphase (Figs 16, 44–46)

Thirteen couples were available. Nucleoli further reduced in number. Micronucleus obliquely orientated in anterior cell half, about 9 × 7 μm in size, with meiotic spindles connecting nuclear poles with paired chromosomes (number could not be estimated). Collar zone portion of left partner completely disintegrated, buccal zone portion of both partners further reduced. Oral primordium up to 12 μm long and apparently without undulating membranes; number of membranelles difficult to ascertain, but apparently slightly higher than in later phases of conjugation.

First maturation division – anaphase and telophase (Figs 17, 18, 44–46)

Six couples were available. Vegetative macronucleus roughly ellipsoidal during anaphase (Fig. 17), while usually fragmented into one large and one small nodule in telophase conjugants (Fig. 18); filled with fine granules, nucleoli about 1 μm across. Micronucleus longitudinally orientated in cell centre: anaphase micronucleus about 13 × 3 μm in size, composed of meiotic spindles connecting bases of darkly impregnated, roughly cone-shaped nuclear ends (Fig. 17); telophase micronucleus about 18 × 3 μm in size, composed of meiotic spindles connecting two darkly impregnated globules (Fig. 18). Besides the four distinct bristle kineties, faintly impregnated granules (probably somatic dikinetids) in several couples until separation of partners (Figs 20, 29, 35, 37), occasionally arranged like somatic anlagen in dividers, i.e., in an anterior and posterior row apparently originating de-novo between two parental kineties each (Figs 27, 28). Bulge of right partner’s frontal plate slightly shifted rightwards. Buccal zone portion almost disappeared.

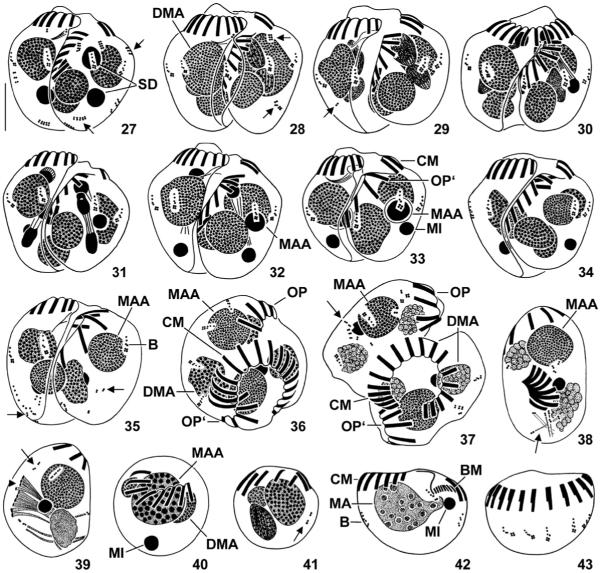

Figs 27–43.

Halteria grandinella, conjugants during (27–32) and after (33–37) second synkaryon division and exconjugants (38–43) after protargol impregnation. 27–29. Ventral view of pairs during interphase, prophase, and metaphase. Note the short and faintly impregnated rows of granules (arrows; probably somatic kinetids). 30–32. Dorsal (30) and ventral (31, 32) view of pairs during anaphase (31) and telophase (30, 32). The posterior division product of the more anterior derivative becomes the macronucleus anlage, the posterior division product of the more posterior derivative represents the developing micronucleus; their sister derivatives disintegrate. 33–35. Ventral view of pairs during late stages of conjugation. Occasionally, scattered somatic kinetids (arrows; 35) occur. 36, 37. Top view of pairs just before separation of conjugants. Note the slightly disordered somatic ciliature (arrow; 37). 38–43. Exconjugants. The globular specimens (40, 41) might not be viable. Arrows (38, 39, 41) mark scattered somatic kinetids. Arrowhead (39) denotes forming or disintegrating membranelles. B – bristle kineties, BM – buccal membranelles of exconjugant, CM – collar membranelles of right conjugant or exconjugant, DMA – degenerating fragments of vegetative macronucleus, MA – new vegetative macronucleus, MAA – macronucleus anlage, MI – developing or mature micronucleus, OP – oral primordium of right conjugant, OP’ – oral primordium of left conjugant, SD – synkaryon derivatives. Scale bar 10 μm.

Due to the lack of distinct morphological changes in the couples, the reconstruction of the following conjugation phases was difficult; frequently, only the shape of the oral primordium indicated the affiliation to a certain stage. Apparently, we missed the interphasic stages and the second division of the maturation process.

Third maturation division (Figs 19–21, 44–46)

Twenty-two couples were available. Intimate contact of partners slightly loosened in couple’s anterior portion, resulting in a small, inverted drop-shaped opening between cytoplasmic bridge and oral primordia. Height of right partner’s frontal plate slightly decreased. Vegetative macronucleus in two, rarely one, three, or four fragments filled with darkly impregnated granules. Up to three maturation derivatives: invariably one dividing derivative; one darkly impregnated derivative (probably a product of second maturation division) about 3 μm across posterior to dividing derivative, disintegrates during anaphase; and one lightly impregnated derivative (probably a product of first maturation division) about 2 μm across anterior or posterior to remaining derivatives, disintegrates during prophase (Figs 19, 20). Prophase derivative in anterior cell half, about 7 × 4 μm in size, with mitotic spindles (Fig. 19). Metaphase derivative in anterior cell half, about 12 × 5 μm in size, with mitotic spindles connecting nuclear poles with segregating chromatids (Fig. 20). Anaphase derivative near cell centre, about 15 × 2 μm in size, with mitotic spindles connecting bases of darkly impregnated, roughly cone-shaped nuclear ends. Telophase derivative near cell centre, about 15 × 3 μm in size, composed of mitotic spindles connecting two darkly impregnated globules (Fig. 21). All buccal membranelles resorbed. Oral primordium curved and slightly obliquely orientated, with fewer membranelles than collar portion of adoral zone, i.e., usually comprises only nine membranelles.

Pronuclei (Figs 22, 44–46)

Five couples were available. Pronuclei about 4 × 3 μm in size. Stationary pronucleus in posterior cell half and broadly ellipsoidal. Migratory pronucleus near cytoplasmic bridge connecting partners, globular to broadly obconical. When migratory pronuclei have been exchanged, the stationary pronucleus migrates to mid-body. Oral primordium curved and slightly obliquely orientated, with 9–11 membranelles. Bases of new membranelles commence to spread, of same length as parental collar membranelles, except for the distally shortened and two-rowed posteriormost one.

First synkaryon division (Figs 23–26, 44–46)

Seventeen couples were available. Fragments of vegetative macronucleus contain dark granules, which are fine during prophase, metaphase, and anaphase, while somewhat coarser during telophase. Argyrophilic vesicles around fragments of vegetative macronucleus disappeared. Synkaryon longitudinally orientated in cell centre. Prophase synkaryon about 8 × 5 μm in size, with mitotic spindles (Fig. 23). Metaphase synkaryon about 10 × 5 μm in size, with mitotic spindles connecting nuclear poles with segregating chromatids (Fig. 24). Anaphase synkaryon about 16 × 4 μm in size, with mitotic spindles connecting bases of darkly impregnated, roughly cone-shaped nuclear ends (Fig. 25). Telophase synkaryon about 17 × 3 μm in size, composed of mitotic spindles connecting two darkly impregnated globules (Fig. 26).

Interphase between first and second synkaryon division (Figs 27, 44–46)

Four couples were available. Fragments of vegetative macronucleus filled with coarse, dark granules. One interphase synkaryon derivative each in anterior and posterior cell portion; anterior derivative broadly ovoidal and slightly larger than globular posterior one (about 5.3 × 4 μm vs. 4 × 4 μm). Oral primordium obliquely orientated and distinctly curved due to spreading of membranellar bases.

Second synkaryon division (Figs 28–32, 44–46)

Thirty-two couples were available. Fragments of vegetative macronucleus contain fine, dark granules during prophase and metaphase, becoming coarse during anaphase and telophase. Synkaryon derivatives almost longitudinally orientated. Anterior derivative usually divides faster than posterior (Figs 30, 32). Prophase derivatives arranged one after the other, about 6 × 4 μm in size, with mitotic spindles and some darkly impregnated granules (Fig. 28). Metaphase derivatives arranged one after the other, about 8 × 4 μm in size, with mitotic spindles connecting nuclear poles with segregating chromatids (Fig. 29). Anaphase derivatives overlapping, about 12 × 3 μm in size, with mitotic spindles connecting bases of darkly impregnated nuclear ends (Fig. 31). Telophase derivatives overlapping, about 15 × 3 μm in size, composed of mitotic spindles connecting two darkly impregnated globules (Figs 30–32). The posterior division product of the more anterior derivative becomes the macronucleus anlage, which is about 5 μm across and has an about 0.5 μm wide bright margin surrounding a darkly impregnated centre. The posterior division product of the more posterior derivative becomes the micronucleus, which is about 3 μm across, i.e., of same size as the two pycnotic derivatives, but more homogenously stained. Paroral membrane likely resorbed. Oral primordium distinctly curved and further inclined, forming an angle of 30–38° with main body axis due to the spreading bases of the membranelles bearing short cilia.

Late couples (Figs 33–37, 44–46)

Twenty-six couples were available. Cleft between partners widens. Right partner’s frontal plate as high as in vegetative cells. Fragments of vegetative macronucleus irregular, composed of darkly impregnated granules (Figs 33–36), becoming frothy before separation of conjugants (Fig. 37). Up to four synkaryon derivatives: the macronucleus anlage, the developing micronucleus, and up to two pycnotic derivatives. Macronucleus anlage usually in cell centre and anterior to developing micronucleus, globular to broadly ellipsoidal, about 6 μm across after second synkaryon division, with an about 1 μm wide, bright margin surrounding a homogenously and darkly impregnated centre. Developing micronucleus about 3 μm across and homogenously stained. Pycnotic derivatives usually anterior to macronucleus anlage and about 3 μm across, represent sister nuclei of macronucleus anlage and developing micronucleus. Collar membranelles of right conjugant unchanged even in very late pairs (Fig. 37). Pharyngeal fibres or funnel present in both partners. Oral primordium distinctly curved, forms an angle of 30–45° with main body axis just after second synkaryon division, later turns out of the cleft between the partners by anticlockwise rotation (Figs 36, 37).

Exconjugants (Figs 38–43)

Eight specimens were available, probably representing five types of non-feeding exconjugants.

Type 1 about 30 × 18 μm in size (n = 4; Fig. 38). Macronucleus anlage in anterior cell half, about 9 μm across, contains fine, darkly impregnated granules. Micronucleus near cell centre, about 3 μm across, homogenously and darkly impregnated. Usually two disintegrating frothy macronucleus fragments: fragment in anterior cell portion about 4–5 μm across, that in posterior portion about 8 × 6 μm in size. Some scattered somatic kinetids associated with fibrous structures 13–18 μm long. Invariably eight membranelles arranged in a C-shaped, slanted zone; bases 5–6 μm long, bearing 9–10 μm long cilia. Buccal cavity, pharyngeal fibres/funnel, endoral membrane, and paroral membrane not recognizable. Oral primordium in centre of dorsal side, C-shaped, composed of eight membranelles.

Type 2 probably represents a late exconjugant, differing from vegetative specimens in a subglobular cell shape, a shallow buccal depression, several kinetids near the buccal vertex (possibly the developing paroral and endoral membrane), and the lack of pharyngeal fibres (n = 1; Figs 42, 43).

For the morphology of the remaining rare exconjugant types, the reader is referred to the illustrations (Figs 39–41).

Discussion

Table 1 compares the conjugation of Halteria grandinella with that of related taxa, viz., the euplotids, hypotrichs, oligotrichs, and choreotrichs.

Table 1.

Conjugation characteristics indicating the phylogenetic relationships of Halteria grandinella. Shared or unique features of Halteria grandinella are in bold

| Characteristics | Euplotidsa | Hypotrichsb |

Halteria

grandinella c |

Oligotrichsd | Aloricate choreotrichse |

Loricate choreotrichsf |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fragmentation of vegetative macronucleus | + (mainly) | + (mainly) | + | ? | − | ? |

| Conjugants’ arrangement | Axes parallel | Axes oblique | Axes parallel; interlocking |

Axes parallel | Axes parallel; interlocking |

Axes parallel |

| Right conjugant, reduction of adoral zone | Proximal; rest not shared |

Proximal; rest shared |

Proximal; rest shared |

Proximal (?); rest not shared |

Proximal; rest not shared |

?; rest not shared |

| Left conjugant, reduction of adoral zone | Proximal | Distal | Complete | Proximal (?) | Proximal | ? |

| Conjugants in paired state | Isomorphic | Dimorphic | Dimorphic | Isomorphic | Isomorphic | Isomorphic |

| Derivatives performing second maturation division | All | All (mainly) | One | ? | All | All |

Diller (1966, 1975), Tuffrau et al. (1976), Turner (1930), Wichterman (1967).

Gregory (1923), Hammersmith (1976), Moldenhauer (1965), Ricci and Banchetti (1981), Tuffrau et al. (1981).

This study, Szabó (1934), Tamar (1974).

SA own data.

Preconjugants and preliminary division of micronucleus

While preconjugants are not produced in the taxa under consideration, a preliminary division of the micronucleus developed convergently in euplotids and peritrichs (this study; Raikov 1972).

Type of conjugation

Except for a few hypotrichs with total conjugation (Heckmann 1965; Heumann 1975), the taxa under consideration have a temporary, bizygotic conjugation (this study; Hammersmith 1976; Laval-Peuto 1983; Ota and Taniguchi 2003; Raikov 1972; Rosati et al. 1998; Tuffrau et al. 1981). Replication bands are not observed in the conjugants of hypotrichs (Adl and Berger 2000), choreotrichs (Ota and Taniguchi 2003), and H. grandinella (this study), while they might occur in Euplotes during the preliminary or third maturation division (Rao 1964; Turner 1930) and in Aspidisca during the first maturation division (Diller 1975).

Morphology of conjugants

All taxa under consideration have an isogamontic conjugation (SA own data; this study; Diller 1975; Laval-Peuto 1983; Raikov 1972; Ricci and Banchetti 1981; Rosati et al. 1998), and thus show the most common pattern (Raikov 1972). However, Gold and Pollingher (1971) observed anisogamontic conjugation in long term cultures of the loricate choreotrich (tintinnid) Tintinnopsis beroidea. While the partners remain isomorphic in euplotids, oligotrichs, and choreotrichs, the conjugants soon become dimorphic in hypotrichs (Hammersmith 1976; Moldenhauer 1965; Tuffrau et al. 1981) and halteriids (this study) mainly due to a differential resorption of the ciliary organelles (see below).

Arrangement of conjugants, morphology of pairs, and separation of partners

All taxa under consideration have a homopolar pair formation, while the heteropolar arrangement occasionally observed in the loricate choreotrichs (tintinnids) is attributed to the manipulation (Laval-Peuto 1983) or the contraction of the conjugants (Laackmann 1906). In hypotrichs, the left anterior portion of one partner fuses with the right one of the other, so that their ventral sides face the substrate (Gregory 1923; Tuffrau et al. 1981). In euplotids, the ventral side of the right conjugant covers the partner dorsolaterally (e.g., Aspidisca; Diller 1975; Rosati et al. 1998) or the ventral sides of the partners overlap laterally (e.g., Euplotes; Diller 1966). Likewise, the ventral sides face in choreotrichs, oligotrichs, and halteriids (this study; SA own data; Laval-Peuto 1983; Penard 1916; Szabó 1934; Tamar 1974); however, the conjugants of halteriids and the aloricate choreotrich Pelagostrobilidium obtain an interlocking arrangement (this study; Ota and Taniguchi 2003; Szabó1934; Tamar 1974). Since such an arrangement is unknown for oligotrichs and loricate choreotrichs, it might represent an adaptation to the jumping movements performed by the two taxa. Accordingly, the interlocking arrangement is considered a convergent apomorphy of halteriids and strobilidiid choreotrichs. As in H. grandinella (this study), the left conjugant of the hypotrich Stylonychia is slightly more posterior than the right (Zou and Ng 1991).

The conjugation of H. grandinella is unique in that it embraces dramatic changes in the size, shape, and ciliature of the conjugants and couples, especially during the first maturation division (Figs 45, 46), providing the couple with the appearance of vegetative cells.

The conjugants separate after the synkaryon divisions in hypotrichs (Adl and Berger 2000; Moldenhauer 1965; Ricci and Banchetti 1981), choreotrichs (Ota and Taniguchi 2003), and H. grandinella (this study), whereas before or during these divisions in euplotids (Diller 1975; Rao 1964; Turner 1930; Wichterman 1967).

Maturation and synkaryon divisions

The maturation and synkaryon divisions are not necessarily synchronous in hypotrichs (Adl and Berger 2000; Gregory 1923), tintinnids (Laackmann 1906), and H. grandinella (this study). In probably all taxa under consideration, the prophase of the first maturation division includes the “parachute” stage (this study; Adl and Berger 2000; Ammermann 1965; Gregory 1923; Moldenhauer 1965; Raikov 1972; Turner 1930).

Euplotids, hypotrichs, and choreotrichs show three maturation and two synkaryon divisions; both products of the first maturation division apparently undergo the second division (Adl and Berger 2000; Diller 1975; Laackmann 1906; Ota and Taniguchi 2003; Turner 1930). Accordingly, these taxa represent the most common pattern (Miyake 1996; Raikov 1972). In H. grandinella, only one (usually the anterior) derivative of the first maturation division performs the second division, while the sister nucleus degenerates (Figs 19, 20, 44). The arrangement of the derivatives also suggests that only the anterior product of the second maturation division performs the third division, while the sister nucleus again degenerates (Figs 19, 44). Likewise, only one derivative of the first maturation division participates in the second division in the hypotrich Oxytricha bifaria (Ricci and Banchetti 1981), the cyrtophorid Chilodonella, and the peniculine Paramecium bursaria (Raikov 1972). Since the latter pattern is less widely distributed, it is assumed to represent the apomorphic character state. Probably, it developed independently in O. bifaria and H. grandinella as the alternative is less parsimonious (see ‘Phylogenetic aspects’). The pronuclei originate from sister nuclei in aloricate choreotrichs (Ota and Taniguchi 2003), several hypotrichs (Ricci and Banchetti 1981) and euplotids (Wichterman 1967), and in H. grandinella (Fig. 44).

Raikov (1972) classified the hypotrichs and euplotids in the “nuclear reconstruction type II” because of two synkaryon divisions. In the “subtype Euplotes”, the macronucleus anlage and the developing micronucleus are sister nuclei, while the other synkaryon derivatives degenerate, as described in Euplotes cristatus by Wichterman (1967). However, the nuclear reconstruction is apparently variable in euplotids: in several Euplotes species, the macronucleus anlage and the developing micronucleus are separated by the first synkaryon division and their sister nuclei degenerate as in H. grandinella (Fig. 44; this study; Diller 1966; Rao 1964; Turner 1930), whereas Aspidisca costata and Diophrys scutum belong to the “subtype Stylonychia”, in which the macronucleus anlage and the two developing micronuclei are again separated by the first synkaryon division, but only one derivative, viz., the sister nucleus of the macronucleus anlage, degenerates as in the aloricate choreotrich Pelagostrobilidium and several hypotrichs (Adl and Berger 2000; Diller 1975; Ota and Taniguchi 2003; Raikov 1972; Ricci and Banchetti 1981).

The posteriormost derivative of the second synkaryon division becomes the micronucleus in H. grandinella (this study) and often one or the only micronucleus in euplotids (Diller 1975; Turner 1930) and hypotrichs (Moldenhauer 1965; Ricci and Banchetti 1981). The macronucleus anlage originates from the first or second derivative (counted from the anterior cell end) in the hypotrich Urostyla polymicronucleata (Moldenhauer 1965), while from the third derivative in H. grandinella (Fig. 44), the hypotrich Oxytricha (Ricci and Banchetti 1981) as well as in the euplotids Aspidisca (Diller 1975) and Euplotes (Turner 1930).

Fate of vegetative macronucleus

The vegetative macronucleus breaks into pieces prior to pycnosis in most spirotrichs (Raikov 1972), including H. grandinella (this study). In some spirotrichs, the aloricate choreotrich Pelagostrobilidium (Ota and Taniguchi 2003), and a few further taxa (Raikov 1972), however, the vegetative macronucleus disintegrates without fragmentation; this probably represents the apomorphic state, which developed convergently in the taxa mentioned above. The fragmentation takes place during the first maturation division in hypotrichs (Ammermann 1965; Gregory 1923; Moldenhauer 1965; Ricci and Banchetti 1981) and H. grandinella (this study), whereas during the preliminary division (Wichterman 1967) or during/after the synkaryon divisions in euplotids (Diller 1975; Turner 1930). A segregation of argyrophilic and thus probably DNA-containing material from the macronucleus fragments occurs during the maturation divisions in H. grandinella (Fig. 46), the tintinnids (Laackmann 1906), and the hypotrichs Sterkiella and Oxytricha (Adl and Berger 2000; Gregory 1923), while after the synkaryon formation in the hypotrich Stylonychia (Moldenhauer 1965).

Resorption of ciliature in couples

Since a bipartition in buccal and collar membranelles is untypical for euplotids and hypotrichs, the adoral zone of membranelles is regarded as an entity here. Generally, the proximal portion of the membranellar zone is reduced in one partner (Fig. 45; Diller 1966, 1975; Ota and Taniguchi 2003; Tuffrau et al. 1981). In the other partner, the fate of the membranellar zone is apparently taxon-specific: in euplotids, the aloricate choreotrich Pelagostrobilidium, and apparently oligotrichs, the proximal portion disintegrates (SA own data; Diller 1966, 1975; Ota and Taniguchi 2003; Tuffrau et al. 1976; Turner 1930); in hypotrichs, the distal portion disintegrates (Hammersmith 1976; Moldenhauer 1965; Tuffrau et al. 1981); and in H. grandinella, the whole adoral zone disintegrates (Fig. 45). Hence, the dimorphism of the hypotrichs and H. grandinella is probably achieved by different disintegration events. Accordingly, the loss of merely the distal membranelles and the disintegration of all membranelles are regarded as two unordered apomorphic states.

While the two membranellar zones remain separate in the euplotids, choreotrichs, and apparently oligotrichs (SA own data; Buddenbrock 1920; Gourret and Roeser 1888; Laval-Peuto 1983; Leegaard 1915; Penard 1916), the remaining distal zone portion, namely, that of the right partner, is shared by the two conjugants in the hypotrichs and H. grandinella; this was not recognized by Szabó (1934) and Tamar (1974). It possibly represents a strong apomorphy of hypotrichs and halteriids; however, it is not a synapomorphy as a common origin of the feature, necessitating several convergences, is less parsimonious (see ‘Phylogenetic aspects’). This is substantiated by the different composition of the adoral zone in middle conjugants: in hypotrichs, the distal zone portion is provided by one partner and the proximal portion by the other, whereas the zone is formed by merely one partner in H. grandinella as the other has lost all membranelles (see above). Despite the taxon-specific differences, however, the partial or entire disintegration of the oral ciliature together with the disappearance of the buccal cavity and the cytopharynx is quite common during conjugation (Raikov 1972). While the distal portion of the old adoral zone is still recognizable in exconjugants of euplotids (Diller 1966; Tuffrau et al. 1976; Turner 1930) and the aloricate choreotrich Pelagostrobilidium (Ota and Taniguchi 2003), it disintegrates prior to the partners’ separation in hypotrichs (Gregory 1923; Moldenhauer 1965; Tuffrau et al. 1981). In H. grandinella, the right partner’s collar membranelles are still present in couples just before separation, while they are absent in the available exconjugants (Figs 38–41, 46); hence, their fate is unknown.

Among the taxa under consideration, the exconjugants of H. grandinella are unique in their strongly reduced or absent somatic ciliature (Figs 38–41) caused by (i) the intimate contact (interlocking arrangement) driving some kineties into the cleft between the partners where they probably disintegrate; (ii) the resorption of the remaining kineties in very late conjugants or early exconjugants; and (iii) the absence of a reconstruction during conjugation (see below). The exconjugants of euplotids, hypotrichs, oligotrichs, and aloricate choreotrichs, however, have a well developed somatic ciliature (SA own data; Diller 1966, 1975; Ota and Taniguchi 2003; Tuffrau et al. 1981).

Reconstruction of ciliature

In euplotids (Diller 1966; Turner 1930), the aloricate choreotrich Pelagostrobilidium (Ota and Taniguchi 2003), and in H. grandinella (Fig. 46), the oral primordium originates during the prophase of the first maturation division, while only during the exchange of the migratory pronuclei in hypotrichs (Gregory 1923; Moldenhauer 1965). This new adoral zone of membranelles is shortened in the euplotid Euplotes (Diller 1966; Tuffrau et al. 1976), the hypotrich Stylonychia (Moldenhauer 1965; Tuffrau et al. 1981), and H. grandinella (this study), whereas it is complete in the hypotrich Oxytricha (Gregory 1923) and the aloricate choreotrich Pelagostrobilidium (Ota and Taniguchi 2003).

Although homology is assumed (Agatha and Strüder-Kypke 2007), the somatic kineties behave differently during ontogenesis in the taxa under consideration: they show an intrakinetal proliferation of basal bodies in euplotids, oligotrichs, choreotrichs, and most hypotrichs, whereas halteriids (Fauré-Fremiet 1953; Petz and Foissner 1992) and the urostylids Thigmokeronopsis and Apokeronopsis (Hu et al. 2004; Petz 1995; Shao et al. 2007; Wicklow 1981) generate the somatic ciliary rows apokinetally in two anlagen each between the parental kineties. Since the first cortical reorganization during conjugation is assumed to be homologous to the asexual mode of cortical development (Zou and Ng 1991), a similar behaviour to that mentioned above is expected. Indeed, the somatic kineties are completely renewed in hypotrichs (Tuffrau et al. 1981). However, the other taxa show deviations from the expected pattern: (i) the ciliary rows are apparently unchanged in euplotids (Diller 1966), oligotrichs (SA own data), and aloricate choreotrichs (Ota and Taniguchi 2003), and (ii) the denovo originating somatic kinetids in H. grandinella are rather scattered and disappear without any obvious reorganization (this study).

Phylogenetic aspects

The conjugation of H. grandinella provides several characteristics to be included in the cladistic analysis: (i) features that are unique to H. grandinella and thus corroborate the monophyly of the halteriids; (ii) features that are shared with the hypotrichs and hence support the SSrRNA trees; and (iii) a feature which is also found in the aloricate choreotrich Pelagostrobilidium and thus substantiates the traditional classification. The unique traits are (i) the complete loss of the adoral zone of membranelles in one partner and (ii) the participation of only one derivative of the first maturation division in the second division. Three features indicate a close relationship between H. grandinella and the hypotrichs: (i) the fragmentation of the vegetative (old) macronucleus, however, representing the plesiomorphic character state; (ii) the transient dimorphism; and (iii) the common usage of the right conjugant’s distal portion of the membranellar zone. The single feature indicating a close relationship between H. grandinella and the aloricate choreotrich Pelagostrobilidium, viz., the interlocking arrangement of the partners, might represent only a convergent adaptation to the jumping movements of the taxa. Nevertheless, eight further morphologic, ontogenetic, and ultrastructural characters, the product of many genes, support a sister group relationship between the halteriids and the cluster of oligotrichs and choreotrichs (Agatha 2004; Agatha and Strüder-Kypke 2007; Foissner et al. 2007): (i) the globular to obconical cell shape; (ii) the apical position of the adoral zone of membranelles; (iii) the absence of cirri; (iv) the shortened somatic kineties; (v) the enantiotropic division mode; (vi) the de-novo origin of the undulating membrane/s; (vii) the bipartited and granular ectocyst; and (viii) the cyst surface with fibrous lepidosomes. Although one might argue that the first four features represent adaptations to the planktonic life style, the latter four characters, including the important enantiotropic division mode, are hardly interpretable as convergences. Furthermore, there is no firm evidence that the planktonic life style causes a halteriid organization in hypotrichs. Unfortunately, the post-conjugation events which might contain some further phylogenetic information could not be followed. Hence, the phylogenetic position of H. grandinella remains uncertain, but the majority of cladistic features still indicates a close relationship to the oligotrich and choreotrich spirotrich ciliates.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Study supported by the Austrian Science Foundation (FWF; projects P17752-B06, P20461-B17, and P19699-B17). The authors wish to thank Helmut Berger, Salzburg, Austria, for providing a comprehensive list of papers on euplotid and hypotrich conjugation.

References

- Adl SM, Berger JD. Timing of life cycle morphogenesis in synchronous samples of Sterkiella histriomuscorum. II. The sexual pathway. J. Euk. Microbiol. 2000;47:443–449. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2000.tb00073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agatha S. A cladistic approach for the classification of oligotrichid ciliates (Ciliophora: Spirotricha) Acta Protozool. 2004;43:201–217. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agatha S, Strüder-Kypke MC. Phylogeny of the order Choreotrichida (Ciliophora, Spirotricha, Oligotrichea) as inferred from morphology, ultrastructure, ontogenesis, and SSrRNA gene sequences. Eur. J. Protistol. 2007;43:37–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ejop.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammermann D. Cytologische und genetische Untersuchungen an dem Ciliaten Stylonychia mytilus Ehrenberg. Arch. Protistenk. 1965;108:109–152. +Plate 23; with English summary. [Google Scholar]

- Berger H. Monograph of the Urostyloidea (Ciliophora, Hypotricha) Monographiae Biol. 2006;85(i–xv):1–1303. [Google Scholar]

- Buddenbrock W. Beobachtungen über einige neue oder wenig bekannte marine Infusorien. Arch. Protistenk. 1920;41:341–364. von. +Plates 16, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Corliss JO. The Ciliated Protozoa. Characterization, Classification and Guide to the Literature. second ed. Pergamon Press; Oxford, New York, Toronto, Sydney, Paris, Frankfurt: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Deroux G. Quelques précisions sur Strobilidium gyrans Schewiakoff. Cah. Biol. Mar. 1974;15:571–588. [Google Scholar]

- Diller WF. Correlation of ciliary and nuclear development in the life cycle of Euplotes. J. Protozool. 1966;13:43–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1966.tb01868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diller WF. Nuclear behavior and morphogenetic changes in fission and conjugation of Aspidisca costata (Dujardin) J. Protozool. 1975;22:221–229. [Google Scholar]

- Fauré-Fremiet E. La bipartition énantiotrope chez les ciliés oligotriches. Arch. Anat. Microsc. Morph. Exp. 1953;42:209–225. [Google Scholar]

- Foissner W. Basic light and scanning electron microscopic methods for taxonomic studies of ciliated protozoa. Eur. J. Protistol. 1991;27:313–330. doi: 10.1016/S0932-4739(11)80248-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foissner W, Müller H, Agatha S. A comparative fine structural and phylogenetic analysis of resting cysts in oligotrich and hypotrich Spirotrichea (Ciliophora) Eur. J. Protistol. 2007;43:295–314. doi: 10.1016/j.ejop.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold K, Pollingher U. Microgamete formation and the growth rate of Tintinnopsis beroidea. Mar. Biol. 1971;11:324–329. [Google Scholar]

- Gourret P, Roeser P. Description de deux infusoires du Port de Bastia. J. Anat. Physiol. 1888;23:656–664. +Plate 25. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory LH. The conjugation of Oxytricha fallax. J. Morph. 1923;37:555–581. [Google Scholar]

- Hammersmith RL. Differential cortical degradation in the two members of early conjugant pairs of Oxytricha fallax. J. Exp. Zool. 1976;196:45–69. doi: 10.1002/jez.1401960106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckmann K. Totale Konjugation bei Urostyla hologama n. sp. Arch. Protistenk. 1965;108:55–62. +Plate 18. [Google Scholar]

- Heumann J. Conjugation in the hypotrich ciliate, Paraurostyla weissei (Stein): a scanning electron microscope study. J. Protozool. 1975;22:392–397. [Google Scholar]

- Hu X, Warren A, Song W. Observations on the morphology and morphogenesis of a new marine hypotrich ciliate (Ciliophora, Hypotrichida) from China. J. Nat. Hist. (London) 2004;38:1059–1069. [Google Scholar]

- Laackmann H. Ungeschlechtliche und geschlechtliche Fortpflanzung der Tintinnen. Wiss. Meeresunters., Abt. Kiel. 1906;10:13–38. +Plates 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Laval-Peuto M. Sexual reproduction in Favella ehrenbergii (Ciliophora, Tintinnina). Taxonomical Implications. Protistologica. 1983;19:503–512. with French summary. [Google Scholar]

- Leegaard C. Untersuchungen über einige Planktonciliaten des Meeres. Nytt. Mag. Naturvid. 1915;53:1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Miyake A. Fertilization and sexuality in ciliates. In: Hausmann K, Bradbury PC, editors. Ciliates: Cells as Organisms. G. Fischer Verlag; Stuttgart, Jena, Lübeck, Ulm: 1996. pp. 243–290. [Google Scholar]

- Moldenhauer D. Zytologische Untersuchungen zur Konjugation von Stylonychia mytilus und Urostyla polymicronucleata. Arch. Protistenk. 1965;108:63–90. +Plates 19–22; with English summary. [Google Scholar]

- Montagnes DJS, Humphrey E. A description of occurrence and morphology of a new species of red-water forming Strombidium (Spirotrichea, Oligotrichia) J. Euk. Microbiol. 1998;45:502–506. [Google Scholar]

- Ota T, Taniguchi A. Conjugation in the marine aloricate oligotrich Pelagostrobilidium (Ciliophora: Oligotrichia) Eur. J. Protistol. 2003;39:149–160. [Google Scholar]

- Paulin JJ. Morphology and cytology of ciliates. In: Hausmann K, Bradbury PC, editors. Ciliates: Cells as Organisms. G. Fischer Verlag; Stuttgart, Jena, Lübeck, Ulm: 1996. pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Penard E. Le Strombidium mirabile. Mém. Soc. Phys. Hist. nat. Genève. 1916;38:227–251. +Plate 8. [Google Scholar]

- Petz W. Morphology and morphogenesis of Thigmokeronopsis antarctica nov. spec. and T. crystallis nov. spec. (Ciliophora, Hypotrichida) from Antarctic sea ice. Eur. J. Protistol. 1995;31:137–147. [Google Scholar]

- Petz W, Foissner W. Morphology and morphogenesis of Strobilidium caudatum (Fromentel), Meseres corlissi n. sp., Halteria grandinella (Müller), and Strombidium rehwaldi n. sp., and a proposed phylogenetic system for oligotrich ciliates (Protozoa, Ciliophora) J. Protozool. 1992;39:159–176. [Google Scholar]

- Raikov IB. Nuclear phenomena during conjugation and autogamy in ciliates. In: Chen T-T, editor. Research in Protozoology IV. Pergamon Press; Oxford, New York, Toronto, Sydney, Braunschweig: 1972. pp. 147–289. [Google Scholar]

- Rao MVN. Nuclear behavior of Euplotes woodruffi during conjugation. J. Protozool. 1964;11:296–304. [Google Scholar]

- Ricci N, Banchetti R. Nuclear phenomena of vegetative and sexual reproduction in Oxytricha bifaria Stokes (Ciliata, Hypotrichida) Acta Protozool. 1981;20:153–164. [Google Scholar]

- Rosati G, Verni F, Dini F. Mating by conjugation in two species of the genus Aspidisca (Ciliata, Hypotrichida): an electron microscopic study. Zoomorphology. 1998;118:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Shao C, Hu X, Warren A, Al-Rasheid KAS, Al-Quraishy SA, Song W. Morphogenesis in the marine spirotrichous ciliate Apokeronopsis crassa (Claparède & Lachmann, 1858) n. comb. (Ciliophora: Stichotrichia), with the establishment of a new genus, Apokeronopsis n. g., and redefinition of the genus Thigmokeronopsis. J. Euk. Microbiol. 2007;54:392–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2007.00278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin MK, Hwang UW, Kim W, Wright A-DG, Krawczyk C, Lynn DH. Phylogenetic position of the ciliates Phacodinium (order Phacodiniida) and Protocruzia (subclass Protocruziidia) and systematics of the spirotrich ciliates examined by small subunit ribosomal RNA gene sequences. Eur. J. Protistol. 2000;36:293–302. [Google Scholar]

- Song W, Wilbert N. Taxonomische Untersuchungen an Aufwuchsciliaten (Protozoa, Ciliophora) im Poppelsdorfer Weiher, Bonn. Lauterbornia. 1989;3:1–221. [Google Scholar]

- Szabó M. Beiträge zur Kenntnis der Gattung Halteria (Protozoa, Ciliata) Arb. Ung. Biol. ForschInst. 1934;7:95–106. with Hungarian summary. [Google Scholar]

- Tamar H. Further studies on Halteria (Weitere Studien an Halteria) Acta Protozool. 1974;13:177–190. +Plates 1–3; with German summary. [Google Scholar]

- Tuffrau M, Tuffrau H, Genermont J. La reórganisation infraciliaire au cours de la conjugaison et l’origine du primordium buccal dans le genre Euplotes. J. Protozool. 1976;23:517–523. [Google Scholar]

- Tuffrau M, Fryd-Versavel G, Tuffrau H. La reórganisation infraciliaire au cours de la conjugaison chez Stylonychia mytilus. Protistologica. 1981;17:387–396. [Google Scholar]

- Turner JP. Division and conjugation in Euplotes patella Ehrenberg with special reference to the nuclear phenomena. Univ. Calif. Publs Zool. 1930;33:193–259. +Plates 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Wichterman R. Mating types, breeding system, conjugation and nuclear phenomena in the marine ciliate Euplotes cristatus Kahl from the Gulf of Naples. J. Protozool. 1967;14:49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Wicklow BJ. Evolution within the order Hypotrichida (Ciliophora, Protozoa): ultrastructure and morphogenesis of Thigmokeronopsis jahodai (n. gen., n. sp.); phylogeny in the Urostylina (Jankowski, 1979) Protistologica. 1981;17:331–351. [Google Scholar]

- Xu K, Foissner W. Body, nuclear, and ciliary changes during conjugation of Protospathidium serpens (Ciliophora, Haptoria) J. Euk. Microbiol. 2004;51:605–617. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2004.tb00594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou SF, Ng SF. Commitment to the first cortical reorganization during conjugation in Stylonychia mytilus: an argument for homology with cortical development during binary fission. J. Protozool. 1991;38:192–200. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.