Abstract

A coupling mechanism that can permanently fix a forcefully contracting muscle to a bone anchor or any totally inert prosthesis would meet a serious need in orthopaedics. Our group developed the OrthoCoupler™ device to satisfy these demands. The objective of this study was to test OrthoCoupler’s performance in vitro and in vivo in the goat semitendinosus tendon model. For in vitro evaluation, 40 samples were fatigue-tested, cycling at 10 load levels, n=4 each. For in vivo evaluation, the semitendinosus tendon was removed bilaterally in 8 goats. Left sides were reattached with an OrthoCoupler, and right sides were reattached using the Krackow stitch with #5 braided polyester sutures. Specimens were harvested 60 days post-surgery and assigned for biomechanics and histology. Fatigue strength of the devices in vitro was several times the contractile force of the semitendinosus muscle. The in vivo devices were built equivalent to two of the in vitro devices, providing an additional safety factor. In strength testing at necropsy, suture controls pulled out at 120.5 ± 68.3 N, whereas each OrthoCoupler was still holding after the muscle tore, remotely, at 298±111.3N (mean ± SD)(p<0.0003). Muscle tear strength was reached with the fiber-muscle composite produced in healing still soundly intact. This technology may be of value for orthopaedic challenges in oncology, revision arthroplasty, tendon transfer, and sports-injury reconstruction.

Keywords: Tendon repair, prosthesis, revision surgery, muscle, biomaterials

Introduction

A permanent artificial tendon that can securely fix a contracting muscle to a bone anchor or any inert prosthesis would meet a need in orthopaedics, with numerous applications [1–3]. Such a device would biologically interface with muscle proximally and provide a link, amenable to established engineering attachment means, at prosthetic interfaces distally. No prior artificial tendons have succeeded [4, 5], while others have explored autogenous bone block techniques [5, 6]. A successful artificial tendon would expand effective treatment in four important applications:

Rendering complete or segmental prosthetic bones functional. Segmental bone prostheses have been developed [5] for upper [4] and lower [6] extremities primarily for oncological use. With prosthetic femurs, tendons not removed as part of the treatment [3] have generally been sutured to the implant. They become fixed with only a fibrous envelope, allowing gait [7], but with less than normal function. Bone block transfer with tendons has had limited success [8–10]; augmentation with a range of tissue factors still restored strength to less than half that of controls [5].

Extensive muscle re-direction for neurological deficit. Rehabilitation sometimes follows the “borrowing” of neo-extensor muscles from a flexor group, or vice versa, reattaching and retraining when natural extensors are destroyed by cerebral palsy or peripartum brachial plexus injury. In spastic cerebral palsy, symptoms can be addressed by operations such as the Green procedure for forearm musculature [1]. Conversely, other procedures such as bilateral posterior adductor transfers to the ischium and iliopsoas transfers have fared less well, and the procedures have been abandoned by some clinicians [11, 12]. Traditional tendon transfer operations have been hampered due to length constraints [11]. An artificial tendon could be made to any length.

Revision arthroplasty. With young, active patients receiving total joints, many clinicians believe that second and third revisions will become more common [4]. A safe and reliable muscle re-coupler that can be re-attached to revision components could be very useful.

Sports-injury reconstruction. For any injury involving tendon, a means of firmly joining to the accompanying muscle(e.g., the posterior tibial musculature, the quadriceps femoris, the subscapularis, and the suprascapularis)by a durable prosthesis could provide an effective treatment[12–14].

We have explored a new approach based on the hypothesis that a low-mass, high-surface-area configuration designed to transfer force by shear could transfer physiologic loads without pressure-damage to tissue. Two considerations led to this hypothesis. First, the surface area—the interface presented by bundles of fine fibers implanted in tissues—multiplied by minimal interstitial tissue pressures and minimal coefficients of friction should withstand high disruption forces. The second consideration was tissue response. Most implants, of implants, from pacemakers to joint prostheses to tissue-expanders, become macro-encapsulated. Despite the low calculable cumulative mass of the fibers per se, feasibility would be lost if each 12 to 25 micron fiber became walled off. Earlier work, however, by Davila [15] and Bruck [16] on size-dependency showed that no poorly-vascularized capsule developed around implants of <50 microns in diameter. Our preliminary studies [17–23]confirmed this finding.

Our device, the OrthoCoupler, is the converse of plant roots in soft soil. Instead of living filaments growing into an inert matrix, bundles of inert fibers are exposed to a living matrix (muscle), which infiltrates the polymer fibers. Either composite exhibits strength exceeding that of the soft matrix, be that soil or muscle. Placement of unbraided, needle-drawn bundles fibers rapidly results in a stable biomechanical composite structure, with adjacent prosthetic fibers rarely in contact [21]. Studies of similar technology for muscle harnessing for circulatory power and for tissue-to-tissue coupling showed bonding strength greater than the muscle itself[17, 18, 20–23]. These studies found infection to be rare(1 occult infection in 189 animals), likely due to preserved vascularity and lack of truly locked-in interstices.

In the present study, we tested three hypotheses:(1) in vitro fatigue strength of the OrthoCoupler exceeds the contractile force of goat semitendinosus muscle;(2) the device in vivo can join this muscle to an implant with higher separation strength at 60 days than the state-of-the-art (Krackow-stitched sutures);(3) ingrowth of muscle tissue occurs among the anchoring fibers as seen histologically.

Materials and Methods

Experimental design

For in vitro evaluation, 4 OrthoCouplers were fatigue-tested at 3 Hz at each of 10 load levels(159, 239, 250, 270, 290, 310, 330, 350, 370, and 390N)until failure or 107 cycles. For in vivo evaluation, 8mature goats (46 to 69 kg, Janet Kelley, Fulton, MI)had the semitendinosus tendon removed bilaterally from its tibial insertion. Left sides were re-attached with an OrthoCoupler; right sides were reattached using the Krackow stitch. Specimens were harvested 60 days post-surgery and used for biomechanics (n = 8) and histology (n = 5, same animals used for biomechanics).

Device specifications and preparation

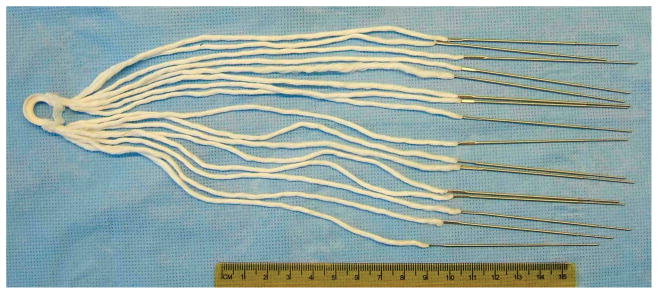

The OrthoCoupler is a series of needle-drawn bundles of several hundred to a few thousand fine polymer fibers. For this research, each bundle was2,30412-μm polyester (polyethylene terephthalate, PET)fibers (Milliken & Co., Spartanburg, SC)swaged into the heel of a straight 7.5 cm needle(laboratory-made, using stainless steel wire and hypodermic tubing from McMaster-Carr, Aurora, OH). Polyester was chosen for its history in use as sutures, meshes, and vascular grafts. The OrthoCoupler had 8(in vitro) or 16(in vivo) of these needle-drawn bundles, assembled in a looped design, with each filament continuing uninterrupted from the proximal end, through the distal “loop”, and back to the proximal end (Fig. 1). This allows the distal loop to be prefabricated as a high-strength composite of the filaments in a matrix of silicone rubber (Shin-Etsu 1300T, durometer 40A, Shin-Etsu Silicones of America, Inc, Akron OH). Solid silicone rubber was chosen for durability.

Figure 1. OrthoCoupler device.

All but 35–40 mm is trimmed away from the bundles upon implantation. Each of the 18,432fibers from the upper 8 needles continues uninterrupted, through the distal loop, to the lower 8, thus presenting twice that number (36,864) of fiber-segments to the muscle; this looped design simplifies bone-plate fixation versus tying and reduces potential stress concentration versus clamping.

The looped design is advantageous because a simple knob is sufficient to attach to the prosthesis, simplifying fixation. Since no free exists requiring clamping or knotting, stress concentration are reduced. Encasing the loop in rubber creates a solid structure that can be customized to the prosthesis. In this study, a stainless steel bone plate illustrated this mechanical attachment.

Each of the 18,432fibers from the upper 8 needles continued uninterrupted to the lower 8, thus presenting twice that number—36,864, or 16 bundles of 2,304 fibers each—of fiber-segments for a 35–40 mm long insertion path. The total polymer surface presented to tissue was ~556cm2 (36,864 fibers × 4cm insertion length × π× 12×10−4 cm diam.). The implant’s bulk within the muscle was low: 0.167 cm3 and <0.25g(<2% of the muscle mass). This quantity of 12-μm fibers was selected to achieve a 1 to 2% cross-section ratio of polymer to muscle, keeping interface area proportionally consistent with work in other muscles [17–23]. Chosen based on assumptions of contractile force, coefficient of friction, and interstitial pressure [20], this proportion has produced closures whose strengths exceeded controls in previous studies, both sutured and unoperated, and did not elicit fibrosis or lead to swelling.

The devices were cleaned and sterilized. An ultrasonic bath (Quantrex, L&R Ultrasonics, Kearny, NJ), was used for one 15-min wash cycle at 50° C, in a 0.4% solution of Sodium Lauryl Sulfate (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) in deionized water, followed by three 15-minute deionized water rinses and air-drying. Devices were then packaged in a gas permeable seal and peel pouch (Instant Sealing Sterilization Pouch, Fisher Scientific), sterilized using an ethylene oxide kit (Anprolene, Andersen Sterilizers, Inc., Haw River, NC), and allowed to outgas in a ventilated exhaust hood for 72 hrs.

In vitro fatigue testing

40 OrthoCouplers were fatigue-tested at 3 Hz at the 10 load levels. The loads ranged from 30% to 73% of the maximum load of 531 N for the device alone, determined in pilot work as the mean tensile strength (889N) minus two std. devs.(std. dev. = 179N). The testing apparatus was custom built to allow simultaneous cycling of up to 16specimens (Fig. 2). The testing apparatus was displacement controlled. Creep was not measured; any slack was eliminated as it occurred by fine manual adjustment. Photographs were taken each minute to record failures. The muscle-end of each specimen was potted in a cylindrical block of silicone rubber (Shin-Etsu 1300T, durometer 40A) contained in PVC holders(lab-made using PVC pipe fittings from McMaster-Carr)mounted to the test platform such that all 16specimens were radially oriented in a circular array. The prosthesis-end of each specimen was attached in series to a spring unit (laboratory-made using stainless-steel spring from McMaster-Carr), and all units were attached to a central, motor-driven translating hub (laboratory-made, motor from Bodine Electric Co., Chicago, IL). Each unit consisted of one or two (in parallel) helical extension springs (spring constant of 1200); the number of coils per spring determined the force per spring at the given displacement (32 mm). Mounting of the holders was adjustable to ensure that each spring unit underwent 32 mm of lengthening per cycle.

Figure 2. Fatigue Test Rig.

The device was run at 3Hz, near continually, for successive sets of samples and a cumulative elapsed time of about 6 months. Photo images recorded each minute established failure times. Continuous ‘web-cam’ images and data sampling allowed off-site monitoring on a 24-hour basis.

Surgical implantation

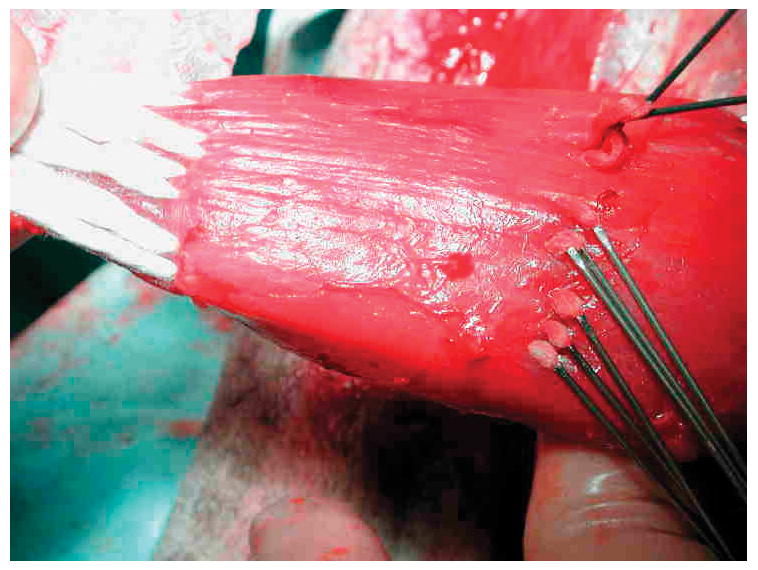

Procedures were performed under general anesthesia (intramuscular Ketamine and Rompun, 11mg and 0.2 mg/kg, respectively) followed by isoflurane inhalation titrated to effect. The University of Cincinnati Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all procedures. The hair was clipped and skin prepared with iodophor solution over both sides of the anterior neck and both hind legs. A 6 cm longitudinal incision was made medial to the proximal tibia, transverse to the semitendinosus muscle, and carried down sharply to the level of the muscle. The resting muscle length was recorded with the stifle and hock in 90° flexion, measuring the distance from the musculotendinous junction to the anterior tibial ridge. This length was later used to position the OrthoCoupler at the proper tension. Semitendinosus tendon was removed bilaterally from its tibial insertion, removing periosteum at the insertion site, and fixing a laboratory-machined stainless steel plate to the tibia. Its neurovascular supply was left intact. Left sides were re-attached with an OrthoCoupler (Fig. 3) as follows. Each needled bundle was inserted into the muscle stump after tenotomy, and exited the muscle about 4 cm proximally. After all bundles were advanced until no slack remained distally, they were tied to one another in adjacent pairs at the proximal exit points in square knots, and the excess was cut off and discarded along with the needles. Right sides (controls) were reattached using the Krackow stitch with #5 braided polyester sutures (Ticron, Davis & Geck, Wayne NJ)by the senior oncology surgeon of our team. Wounds were closed with 2–0 Vicryl (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ)for muscle and subcutaneoustissueand3–0 Dexon (Davis & Geck) for subcuticular tissue. Animals were maintained for 60 days, with pain management early postoperatively and regular walking exercise there after. One animal was lost from fracture at the bone plate screws at 4 days; all others ambulated spontaneously and well at 24–48 hrs. In one goat, the contralateral control was omitted because of local skin inflammation noted during skin prep.

Figure 3. OrthoCoupler surgical implantation.

Needles were subsequently removed, after bundles had been advanced through the tissue and trimmed.

Mechanical testing

Within 1 day of euthanasia, specimens were harvested and kept at −80°C until thawing and testing. The bone segment containing the proximal insertion of the muscle was dissected from the pelvis and captured in a fixture(Fig. 4)on a materials testing frame (858 Bionix MTS Corp, Eden Prairie, MN); the gap between steel rods was wide enough for the muscle but not the bone to pass through. The tibial bone plate was bolted to a fixture above, and the specimen loaded at 1 mm/sec while monitoring load and grip-to-grip displacement. The rate was chosen to allow direct observation of the failure mechanism—pull-out versus tearing or other mode. Failure force was determined as the maximum force achieved. The specimen was grossly inspected, and failure mode of failure—(a) muscle failure with muscle-prosthetic bond intact, (b) prosthetic failure or prosthetic pull-out or (c) some combination—was recorded.

Figure 4. Mechanical testing.

Explanted specimens were gripped via the boneplate above and intact femoral insertion below. All experimental couplings remained intact, exceeding muscle strength. All suture controls pulled out of the muscle.

Histology

Experimental and control specimens from 5 animals were fixed in 10% buffered formalin, processed, and paraffin embedded to allow 5 μm sections to be cut through the repair sites, mounted on glass slides, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin and Masson’s trichrome. Attention was given to the separation of prosthetic filaments by in-growing connective tissue and to the prevalence and nature of inflammatory cells relative to the inflammatory response witnessed with the OrthoCoupler. Ingrowth and deposition of collagenous tissue were evaluated with the aid of trichrome stained sections.

Statistical analysis

A paired Student t test was used to compare the repair strengths. Significance at the p < 0.05 level was required.

Results

In vitro fatiguetTesting

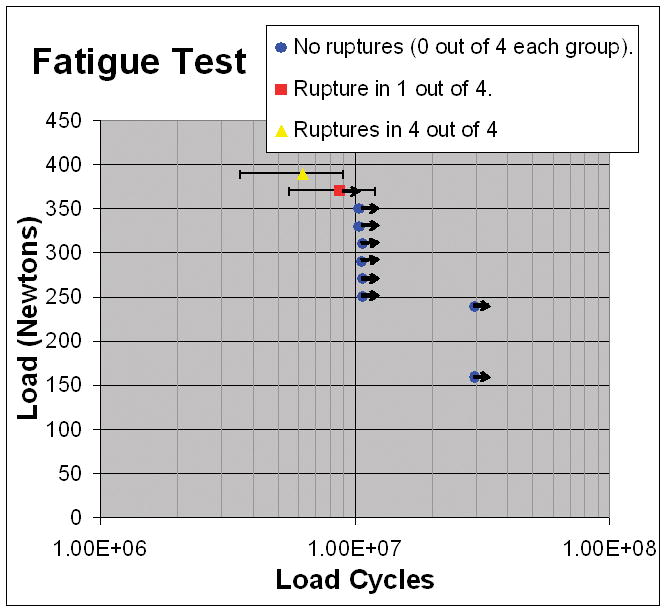

No failures occurred in the 32samples subjected to ≤ 350 N (Fig. 5). One of four broke at 370 N (69.7% of tensile strength, at 3.9 million cycles) and four of four failed at 390 N (73.4% of tensile strength, at 6.3 ± 2.7 million cycles, mean ± SD). No early signs of failure were noted in the specimens that did not fail.

Figure 5. Fatigue Results.

Each point represents 4specimens. Error bars show one standard deviation. Arrows “→” indicate specimens intact when testing ceased.

Mechanical testing after in vivo implantation

All specimens were undisturbed where visible both proximally and distally, both at harvest and after testing. They thus appeared to remain intact in the implantation region, while muscle belly tore only remotely proximal to the device. Every control failed by pull-out of Krackow sutures. Failure forces (Table 1) for muscle-tearing of the OrthoCouplers were 2.5 times higher (p<0.0003) than for suture pull-out in the controls 298 ± 111.3Nvs. 120.5±68.3N.

Table 1.

Failure forces for OrthoCoupler and control specimens at 60 days post-surgery (p = 0.0003; Student t test for paired data).

| Failure forces (N) | Paired data | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goat | Control | OrthoCoupler | Control | OrthoCoupler |

| 1 | 61 | 247 | 61 | 247 |

| 2 | 115 | 213 | 115 | 213 |

| 3 | 95 | 268 | 95 | 268 |

| 4 | 48 | 186 | 48 | 186 |

| 5 | 185 | 437 | 185 | 437 |

| 6 | --- | 387 | -- | -- |

| 7 | 219 | 437 | 219 | 437 |

| Mean | 120.5 | 310.7 | 120.5 | 298 |

| SD | 68.3 | 107.0 | 68.3 | 111.3 |

Histology

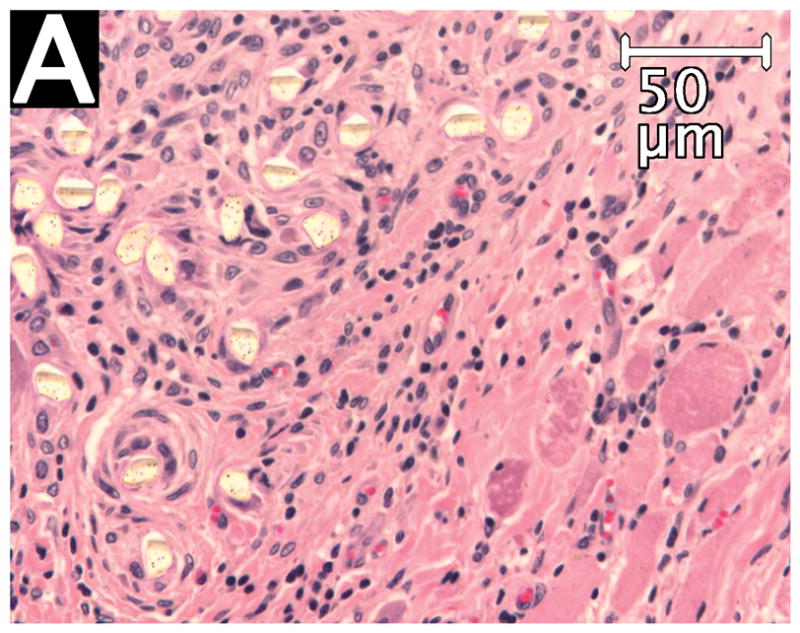

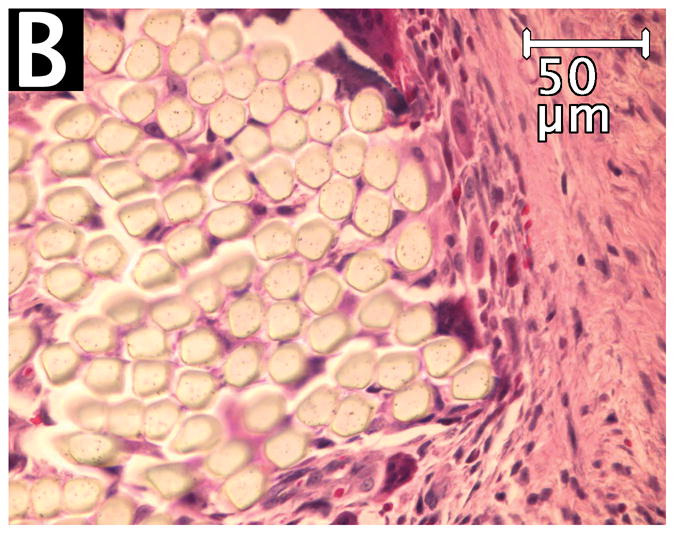

On the experimental side, the fiber-containing regions had remained intact even after mechanical testing, since these specimens failed by tear of native muscle remote from the region of the implant. On the control side, suture pullout left only one end of one suture loop in the tissue. No evidence of microencapsulation or compromise of vascularity was noted in the experimental sections. The filaments of the OrthoCoupler were widely separated with the surrounding healing and inflammatory process extending into the interstices (Fig. 6A). Control sutureshad no such fiber separation, remaining compactly organized (Fig. 6B). In both experimental and control specimens, prosthetic material was surrounded by collagen deposition and inflammatory tissue, including numerous multinucleated giant cells and proliferating granulation tissue(not shown). The inflammatory response was similar to that seen at interfacial tissue, after similar time periods, with conventional synthetic sutures. No infection was observed in any specimen.

Figure 6. Hematoxylin/eosin staining of experimental OrthoCoupler (A) and control suture (B).

The filaments of the OrthoCoupler devices were widely separated with the surrounding healing and inflammatory process extending into the interstices. Control sutures had no such interstices, remaining compactly organized.

Discussion

Our objective was to test the performance of the OrthoCoupler in vitro and in vivo in the goat semitendinosus tendon model. The in vitro fatigue results established mechanical reliability. Data showed 100% durability at stresses up to 350 N, almost six times the predicted maximal skeletal muscle contractile force [24]of the semitendinosus muscle. Testing at 370N showed 75% durability through 10million cycles. The design was dictated by the expected strength of the tissue-to-prosthesis bond, this being far lower than the ultimate or fatigue strengths of the device alone.

In vivo, the device included twice the fibers, providing an additional safety factor. Failure forces for the OrthoCoupler specimens were 2.5 times higher than controls at 60 days post surgery. While neither in vitro testing nor normal ambulation can predict the effect of extreme activities, the device held muscle to almost five times the predicted muscle contractile force before remote muscle tear. In using a standard repair as control, we did not measure the properties of an intact semitendinosus tendon. However, higher device strength would not be expected to elicit a different result. Thorough tissue integration was observed histologically without evidence of microencapsulation or compromise of vascularity, consistent with muscle viability, as suggested by the rapid ability of the goats to walk without guarding these muscles.

We believe the OrthoCoupler has implications for clinical use. Neither an extensive review by Hunter of work from 1903 through 1965 [25] nor subsequent publications [26–29] have documented a successful artificial tendon. The OrthoCoupler could potentially be used in any sports injury reconstruction in which muscle to bone reconstruction might improve on current options for direct tendon repair (e.g., supraspinatus to humerus for rotator cuff or gastrocnemius to calcaneus for Achilles [12–14]). Achilles, quadriceps, and pectoralis tendon tears and severe sprains may be amenable to OrthoCoupler prostheses securely anchored in gastrocnemius, quadriceps, and pectoralis muscles, respectively. Any tendon injury might be effectively treated with this prosthesis used to join directly to the accompanying muscle.

Prior methods have been inadequate for tendon reconstruction. These include autograft and allograft tendons to neotendons generated by ‘scaffolding’, either with carbon fibers[26, 29]that gradually fragment or absorbable suture material[27, 28]. Cords, rods, and cables—sewn to the tendon stump and to bone—work in acute trials[25, 30, 31], but the sutured connections separate after a few days to a few weeks.

Several researchers investigated the use of carbon fibers to repair connective tissues with experiments conducted on Rhesus monkeys as a flexor tendon substitute [26] and in canine triceps and quadriceps tendons [29]. Though strength, flexibility, and capacity to induce a neotendon suggested carbon fiber to be an ideal flexor tendon substitute, induction of fibrosis and accompanying increase in implant bulk resulted in failure [26]. After one year of physiologic use in dogs, the average tensile strength of the composite structure that replaced the quadriceps and triceps tendons had 88% the strength of the natural tendons. However, a significant proportion of the structure was taken up by histiofibroblasts produced by the irritation of the carbon fibers, reducing the mechanical properties over time [29]. The inflammatory response of the polyester-fiber OrthoCoupler is more similar to that of conventional synthetic sutures.

Higuera et al [10] compared methods of attaching supraspinatus tendon to a titanium prosthesis in dogs using bone plates. Preparation of an autogenous bone plate was considered impractical for a clinical setting. Allogenic bone plates saturated with rhOP-1-collagen putty were compared to plates saturated with autogenous cancellous bone and marrow. At 15 weeks post-surgery the insertions had ultimate tensile strengths of 24 and 38% of the intact contralateral side, respectively, without significant differences between them. Our approach, by contrast, does not require harvesting and preparation of autogenous or allogenic tissue products and exceeds the strength of intact tissues (proximal muscle).

Melvin et al developed a coupling device the same as the present OrthoCoupler. The MyoCoupler [21] was conceived as a means to harness retrained skeletal muscle in situ to augment the contractile power of a failing heart. This device increases the force transfer surface by dispersing ultrafine polymer fibers in the distal muscle substance. Multiple 2–0 polyester sutures buttressed with Teflon pledgets were implanted bilaterally in the posterior tibial muscles of 28 rabbits for up to 90 days, with one leg as control and the other supplemented by the MyoCoupler. Pull-out strength for MyoCoupler legs(107.2N) was significantly (p < 0.001) higher than controls (52.1N). This pilot led to fruitful collaborations in the realm of cardiac-support [18, 22, 23]and inspired pursuit of orthopaedic applications.

This study is not without limitations. 1) The study only examined one time point. Future studies will need to evaluate the biomechanics of the repairs at longer time points. 2) Biological mechanisms responsible for the observed treatment-induced differences in repair biomechanics and structure must still be investigated. 3) Semi-quantitative and quantitative histology were not performed, but should be explored in future studies. 4) The local viscoelastic properties of the prosthetic-muscle composite region were not assessed; this also will be studied in future investigations. 5) Any bone anchor or prosthesis may be adapted to this loop and replaced if needed without disrupting the loop. However, this study did not investigate further bone-interface possibilities, such as integrating resorbable bone anchors with these fibers6) Although ambulation and weight-bearing was similar between operated and unoperated goats, no measurement of active force generation was done. No atrophy or fatty infiltration was observed upon dissection, but no direct comparison with normal was possible since our controls were operated as well.

The current study establishes adequacy of the coupling. The device occupies < 2% of the muscle cross-sectional area. Animals required no external fixation, support, or assistance to ambulate spontaneously at 24–48 hours. The fixation strength exceeded the passive tensile strength of the intact muscle. Histology showed fully vascularized integrated tissue, suggesting permanently sustained strength in longer-term studies (now underway), and in different tissue models. We believe this technology may be of value for clinical challenges in orthopaedic oncology, an expanded application of tendon-transfer, revision arthroplasty, and sports-injury reconstruction.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the NIH (NIAMSAR049941) given to Surgical Energetics Inc. (formerly CardioEnergetics Inc.).

References

- 1.Beach WR, Strecker WB, Coe J, et al. Use of the Green transfer in treatment of patients with spastic cerebral palsy: 17-year experience. J Pediatr Orthop. 1991;11:731–736. doi: 10.1097/01241398-199111000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kvist J, Ek A, Sporrstedt K, et al. Fear of re-injury: a hindrance for returning to sports after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2005;13:393–397. doi: 10.1007/s00167-004-0591-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nerubay J, Katznelson A, Tichler T, et al. Total femoral replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988:143–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campanacci M, Capanna R, Ceervellati C, et al. Modular rotatory endoprosthesis for segmental resection of the proximal humerus: experience with thirty-three cases. In: Chao EYS, Ivins JC, editors. Tumor prostheses for bone and joint reconstruction: the design and application. New York: Thieme-Stratton; 1983. pp. 127–130. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chao EYS, Frassica FJ, Sim FH. Biology, Biomaterials and Mechanics of Prosthetic Implants. In: Simon MA, Springfield D, editors. Surgery for Bone and Soft-tissue Tumors. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1998. pp. 453–465. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ozaki T, Kunisada T, Kawai A, et al. Insertion of the patella tendon after prosthetic replacement of the proximal tibia. Acta Orthop Scand. 1999;70:527–529. doi: 10.3109/17453679909000997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Panagiotopoulos EC, Kallivokas AG, Koulioumpas I, et al. Early failure of a zirconia femoral head prosthesis: fracture or fatigue? Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2007;22:856–860. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gottsauner-Wolf F, Egger EL, Schultz FM, et al. Tendons attached to prostheses by tendon-bone block fixation: an experimental study in dogs. J Orthop Res. 1994;12:814–821. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100120609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higuera CA, Inoue N, Zhang R, et al. Orthopaedic Research Society meeting. San Francisco, CA, USA: 2004. Direct Tendon Reattachment to Metallic Implant Augmented with rhOP-1 and Allogenic Bone Plate in a Canine Model. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Higuera CA, Inoue N, Lim JS, et al. Tendon reattachment to a metallic implant using an allogenic bone plate augmented with rhOP-1 vs. autogenous cancellous bone and marrow in a canine model. J Orthop Res. 2005;23:1091–1099. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2005.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chuang DC, Ma HS, Borud LJ, et al. Surgical strategy for improving forearm and hand function in late obstetric brachial plexus palsy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109:1934–1946. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200205000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crossett LS, Sinha RK, Sechriest VF, et al. Reconstruction of a ruptured patellar tendon with achilles tendon allograft following total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-A:1354–1361. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200208000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dabernig J, Shilov B, Schumacher O, et al. Single-stage achilles tendon reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2004;52:626. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000128084.05862.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoffmann F, Schiller M, Reif G. Arthroscopic rotator cuff reconstruction. Orthopade. 2000;29:888–894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davila JC, Lautsch EV, Palmer TE. Some physical factors affecting the acceptance of synthetic materials as tissue implants. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1968;146:138–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1968.tb20278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bruck SD. Polymeric materials: current status of biocompatibility. Biomater Med Devices Artif Organs. 1973;1:79–98. doi: 10.3109/10731197309118864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franklin JE, Marler JJ, Byrne MT, et al. Fiber technology for reliable repair of skeletal muscle. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2009;90:259–266. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Melvin DB, Santamore W, Trumble DR, et al. A durable load bearing muscle-prosthetic coupling. In: Guldner NW, Klapproth P, Jarvis JC, editors. Cardiac Bioassist 2002. Aachen: Shaker Verlag; 2003. pp. 157–166. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Melvin DB, Byrne MT, Gramza BR, et al. A Novel Approach Towards the Development of an Artificial Tendon. Trans Orthop Res Soc. 2004;29:851. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Melvin DB, Glos DL, Abiog MC, et al. Coupling of skeletal muscle to a prosthesis for circulatory support. ASAIO J. 1997;43:M434–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Melvin DB, Klosterman B, Gramza BR, et al. A durable load bearing muscle to prosthetic coupling. ASAIO J. 2003;49:314–319. doi: 10.1097/01.mat.0000065369.46216.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trumble DR, Melvin DB, Byrne MT, et al. Improved mechanism for capturing muscle power for circulatory support. Artif Organs. 2005;29:691–700. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2005.29108.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trumble DR, Melvin DB, Magovern JA. Method for anchoring biomechanical implants to muscle tendon and chest wall. ASAIO J. 2002;48:62–70. doi: 10.1097/00002480-200201000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sola OM, Haines LC, Kakulas BA, et al. Comparative anatomy and histochemistry of human and canine latissimus dorsi muscle. J Heart Transplant. 1990;9:151–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hunter J. Artificial Tendons. Early Development and Application. Am J Surg. 1965;109:325–338. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(65)80081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rawlins R. The role of carbon fibre as a flexor tendon substitute. Hand. 1983;15:145–148. doi: 10.1016/s0072-968x(83)80004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Howard CB, McKibbin B, Ralis ZA. The use of Dexon as a replacement for the calcaneal tendon in sheep. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1985;67:313–316. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.67B2.3980547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldstein JD, Tria AJ, Zawadsky JP, et al. Development of a reconstituted collagen tendon prosthesis. A preliminary implantation study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;71:1183–1191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mendes DG, Iusim M, Angel D, et al. Ligament and tendon substitution with composite carbon fiber strands. J Biomed Mater Res. 1986;20:699–708. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820200604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Badylak SF, Stevens L, Janas W, et al. Cardiac assistance with electrically stimulated skeletal muscle. Med Biol Eng Comput. 1989;27:159–162. doi: 10.1007/BF02446225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farrar DJ, Hill JD. A new skeletal muscle linear-pull energy convertor as a power source for prosthetic circulatory support devices [corrected] J Heart Lung Transplant. 1992;11:S341–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]