Late transition metal carbenes are versatile intermediates and can undergo a wide range of highly valuable and often difficult transformations including C–H insertion/functionalization, cyclopropanation, and formation of reactive ylides.1 It is not surprising that the generation of these species has been subjected to intensive studies. Of particular practical importance are methods that are highly reliable and do not require the assistance/participation of a tethered functional group.2 The most useful method of this kind is metal-catalyzed decomposition of diazo compounds, especially relatively stable α-diazo carbonyl compounds. Consequently, there are a plethora of versatile synthetic methods developed based on these compounds using transition metals such as Rh and Cu.3 However, diazo compounds are: a) hazardous and potentially explosive; b) mostly prepared from carbonyl precursors without much enhancing molecular complexity, thus diminishing efficiency in synthetic sequences.

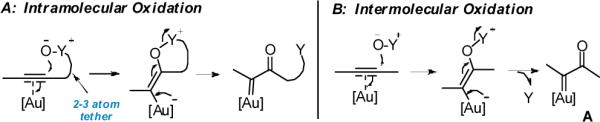

Recent rapid development in gold catalysis offers alternative approaches4 to generate α-oxo metal carbenes (gold as the metal) via intramolecular oxidation of alkynes. While several versatile synthetic methods have been developed based on this strategy, the required oxidants had to be tethered to the C–C triple bond in optimal distances (Scheme 1A).5 This requirement of intramolecularity imposes significant structural constraints on both substrates and products and severely limits the synthetic potential of this chemistry. So far no success has been reported with external oxidants (Scheme 1B).6 Significantly, the intermolecular approach makes alkynes equivalent to α-diazo ketones without their afore-mentioned drawbacks and, moreover, offers much synthetic flexibility in comparison to the intramolecular one! Herein, we report the first example of accessing α-oxo gold carbenes via intermolecular oxidation of terminal alkynes under mild reaction conditions and its application in a simple but efficient preparation of dihydrofuran-3-ones. Notably, the existing synthetic methods for this useful class of O-heterocycles7 typically require multiple steps and/or rather functionalized substrates.8

Scheme 1.

Access to α-Oxo Gold Carbenes: Intra- vs Intermolecuar oxidation

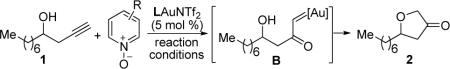

We began with using homopropargylic alcohol 1 as substrate, anticipating that an intramolecular O–H insertion by the gold carbene moiety in B would be facile and productive (Table 1). After limited success using various sulfoxides as external oxidants, we turned to pyridine N-oxides, hoping to limit the known 3,3-rearrangement.6 To our delight, dihydrofuran-3-one 2 was indeed formed using the parent pyridine N-oxide albeit in only 9% yield (entry 1). We suspected that basic pyridine formed during the reaction might deactivate IPrAuNTf2.9 The addition of acids indeed substantially improved the reaction (entries 2–6), and the yields were around 50–56% using strong acids (entries 3–6); moreover, the stronger the acid was, the faster the reaction proceeded. Consequently, the reaction could be performed conveniently at room temperature (entries 4–6) with acceptable reaction times. We chose MsOH to further optimize the reaction conditions, hoping to balance the reaction time and the acidity of the reaction system. A range of substituted pyridine N-oxides were examined and some were shown in entries 7–10. 3,5-Dichloropyridine N-oxide and 2-bromopyridine N-oxide turned out to work equally well. The reaction conditions were further improved by lowering the acid amount without sacrificing much of the yield (entry 11). Surprisingly, Ph3PAuNTf2 performed better than IPrAuNTf2 (entries 13 and 14), which was advantageous due to its lower cost. Of note, PtCl2 and AuCl3 led to poor results (13 % and 15%, respectively), and no reaction was observed in the absence of a metal catalyst.

Table 1.

Reaction Conditions Optimization.a

| entry | L | Rb | acidb | conditions | yieldc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | IPr | H | - | DCE, 60 °C, 10 h | 9%d |

| 2 | IPr | H | Cl3CCO2H | DCE, 60 °C, 10 h | 32%e |

| 3 | IPr | H | F3CCO2H | DCE, 60 °C, 5.5 h | 56% |

| 4 | IPr | H | F3CCO2H | DCE, rt, 8 h | 53% |

| 5 | IPr | H | MsOH | DCE, rt, 4.5 h | 51% |

| 6 | IPr | H | TfOH | DCE, rt, 2 h | 54% |

| 7 | IPr | 3-Br | MsOH | DCE, rt, 2.5 h | 64% |

| 8 | IPr | 3,5-Cl2 | MsOH | DCE, rt, 2.5 h | 68% |

| 9 | IPr | 2-Br | MsOH | DCE, rt, 3.5 h | 68% |

| 10 | IPr | 4-Ac | MsOH | DCE, rt, 8 h | 52% |

| 11 | IPr | 2-Br | MsOHf | DCE, rt, 3.5 h | 65% |

| 12 | Et3P | 2-Br | MsOHf | DCE, rt, 3.5 h | 64% |

| 13 | Ph3P | 2-Br | MsOH f | DCE, rt, 2.5 h | 78% g |

| 14 | Ph3P | 3,5-Cl2 | MsOH f | DCE, rt, 2.5 h | 75% |

[1] = 0.05 M; DCE: 1, 2-dichloroethane.

2 equivalent.

Estimated by 1H NMR using diethyl phthalate as internal reference.

75% conversion.

68% conversion.

1.2 equivalent.

76% isolated yield.

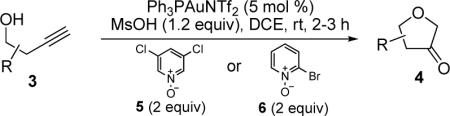

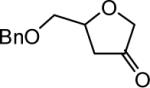

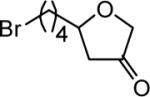

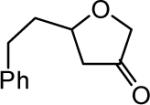

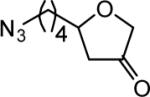

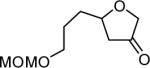

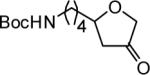

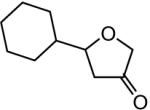

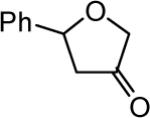

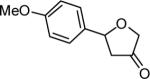

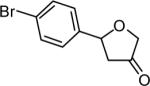

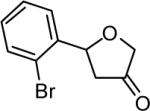

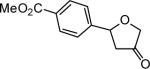

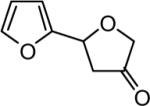

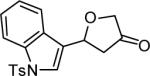

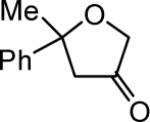

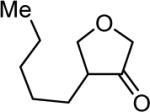

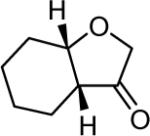

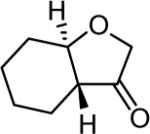

The reaction scope was then promptly studied. As shown in Table 2, this reaction proceeded well with various substrates, and the yields ranged from 55% (entry 12) to 88% (entry 18); moreover, a variety of functional groups were tolerated. Several conclusions can be drawn from these studies: a) this gold-catalyzed oxidative strategy is a reliable method for accessing α-oxo gold carbenes, and may allow predictable synthetic designs; the exceptions were terminal alkynes that can undergo facile cyclization by tethered nucleophiles (e.g., 5-exo-dig cyclization in the case of bishomopropargylic alcohols, which led to low efficiency); b) the reaction system was mildly acidic, and both Boc and MOM groups were tolerated (entries 5–6); although MsOH (pKa, −2.6) is a strong acid, the excess pyridine N-oxide (pKa, 0–1)10 acted as a base and tempered the reaction acidity; the mild acidity of the reaction was also evident with furan and indole substrates (entries 13 and 14); c) a general trend can be deduced based on the results of a series of aryl substrates (e.g., entries 8, 9, 12 and 13): the more nucleophilic the HO group is, the more efficient the reaction is; this is in agreement with the fact that better yields were frequently obtained with R = aliphatic or functionalized aliphatic groups (entries 2, 5, 17 and 18); d) for the furan (entry 13) and indole (entry 14) substrates, no 5-exo-dig or 6-endo-dig11 cyclization to the arene ring was observed, reflecting the facile nature of the oxidation; e) finally, the efficient formation of strained 5,6-trans-fused 4r suggests the synthetic potential of this chemistry and again the mild nature of the reaction as its epimerization was observed during purification using either neutral alumina or silica gel columns.

Table 2.

Reaction Scopea

| entry | N-oxide | product | 4/yieldb |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 |

|

4a 68% |

| 2 | 5 |

|

4b 80% |

| 3 | 5 |

|

4c 68% |

| 4 | 5 |

|

4d 82% |

| 5 | 5 |

|

4e 62% |

| 6 | 5 |

|

4f 64% |

| 7 | 5 |

|

4g 72% |

| 8 | 6 |

|

4h 63% |

| 9 | 6 |

|

4i 75% |

| 10 | 6 |

|

4j 66% |

| 11 | 6 |

|

4k 65% |

| 12 | 6 |

|

4l 55% |

| 13 | 6 |

|

4m 76% |

| 14 | 6 |

|

4n 68% |

| 15c | 5 |

|

4o 58% |

| 16 | 5 |

|

4p 65% |

| 17d | 5 |

|

4q 82% |

| 18e | 5 |

|

4rf 88% |

[3] = 0.05 M.

isolated yields.

Time: 6h.

Time: 4 h.

Temperature: 0 °C; time: 5 h.

About 4% of 4q was formed upon silica gel column purification.

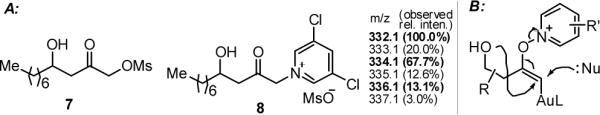

The formation of gold carbenes was supported by the isolation of mesylate 712 and the observation of pyridium 8 by crude 1H NMR and ES+MS (Figure 1A). In fact, side products of these types counted for most of the remaining substrates. Although their formation could be rationalized by an SN2′ process (Figure 1B) as well, the formation of 2 would require a disfavored 5-endo-trig cyclization;13 furthermore, the efficient and easy formation of 4r argues against this alternative kinetically. Of note, our attempts to convert 7 or 8 to 2 did not succeed even under basic conditions.

Figure 1.

In summary, we have developed a convenient and reliable access to reactive α-oxo gold carbenes via gold-catalyzed intermolecular oxidation of terminal alkynes under mild reaction conditions. This intermolecular strategy provides much improved synthetic flexibility comparing to the intramolecular ones and offers a safe and economic alternative to those based on diazo substrates. Its synthetic potential is demonstrated by expedient preparation of dihydrofuran-3-ones containing a broad range of functional groups.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank NSF (CAREER award CHE-0969157), NIGMS (R01 GM084254) and UCSB for generous financial support.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures, compound characterization data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- (1).For monographs, see: Dörwald FZ. Metal Carbenes in Organic Synthesis. Wiley-VCH: Weinheim; New York: 1999. . Barluenga J, Rodríguez F, Fañanás FJ, Flórez J. In: Metal Carbenes in Organic Synthesis. Dötz KH, editor. Berlin; Springer: 2004. pp. 59–122.. Doyle MP, McKervey MA, Ye T. Modern Catalytic Methods for Organic Synthesis with Diazo Compounds : From Cyclopropanes to Ylides. Wiley; New York: 1998. .

- (2).For example, Au/Pt carbenes are formed as intermediates via enyne isomerization, for reviews, see: Abu Sohel SM, Liu R-S. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009;38:2269–2281. doi: 10.1039/b807499m.. Jiménez-Núñez E, Echavarren AM. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:3326–3350. doi: 10.1021/cr0684319.. Zhang L, Sun J, Kozmin SA. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2006;348:2271–2296.. Ma S, Yu S, Gu Z. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:200–203. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502999..

- (3).For selected reviews and monographs, see: Padwa A, Pearson WH. Synthetic Applications of 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition Chemistry toward Heterocycles and Natural Products. Wiley; New York Chichester: 2002. . Davies HML, Beckwith REJ. Chem. Rev. 2003;103:2861–2904. doi: 10.1021/cr0200217.. Mehta G, Muthusamy S. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:9477–9504.. Taber DF. In: Comprehensive Organic Synthesis. Trost BM, Fleming I, Pattenden G, editors. Vol. 3. Pergamon Press; Oxford, England: 1991. pp. 1045–1062..

- (4).For examples of gold carbenes generated from diazo compounds, see: Fructos MR, Belderrain TR, de Frémont P, Scott NM, Nolan SP, Díaz-Requejo MM, Pérez PJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:5284–5288. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501056.. Li Z, Ding X, He C. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:5876–5880. doi: 10.1021/jo060016t.. Ricard L, Gagosz F. Organometallics. 2007;26:4704–4707.. Flores JA, Dias HVR. Inorg. Chem. 2008;47:4448–4450. doi: 10.1021/ic800373u.. Fedorov A, Moret M-E, Chen P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:8880–8881. doi: 10.1021/ja802060t.. Prieto A, Fructos MR, Díaz-Requejo MM, Pérez PJ, Pérez-Galán P, Delpont N, Echavarren AM. Tetrahedron. 2009;65:1790–1793..; For a carbene transfer from Cr(0), see: Fañanás-Mastral M, Aznar F. Organometallics. 2009;28:666–668..; For the use of propargylic esters in gold catalysis, see: Marion N, Nolan SP. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007;46:2750–2752. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604773.. José M-C, Elena S. Chem Eur J2007:1350–1357. doi: 10.1002/chem.200601522..

- (5).(a) Gorin DJ, Davis NR, Toste FD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:11260–11261. doi: 10.1021/ja053804t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Shapiro ND, Toste FD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:4160–4161. doi: 10.1021/ja070789e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Li G, Zhang L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007;46:5156–5159. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Cui L, Zhang G, Peng Y, Zhang L. Org. Lett. 2009;11:1225–1228. doi: 10.1021/ol900027h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Cui L, Peng Y, Zhang L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:8394–8395. doi: 10.1021/ja903531g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Yeom H-S, Lee J-E, Shin S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:7040–7043. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Yeom HS, Lee Y, Lee J-E, Shin S. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2009;7:4744–4752. doi: 10.1039/b910757f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Davies PW, Albrecht SJC. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009;48:8372–8375. doi: 10.1002/anie.200904309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).For a study on intermolecular oxidation, see: Cuenca AB, Montserrat S, Hossain KM, Mancha G, Lledós A, Medio-Simón M, Ujaque G, Asensio G. Org. Lett. 2009;11:4906–4909. doi: 10.1021/ol9020578..

- (7).A simple SciFinder search of compounds containing the dihydrofuran-3-one skeleton resulted in >5000 entries with reported biological studies.

- (8).For an example, see: Watts J, Benn A, Flinn N, Monk T, Ramjee M, Ray P, Wang Y, Quibell M. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2004;12:2903–2925. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.03.042..

- (9).de Frémont P, Marion N, Nolan SP. J. Organometallic Chem. 2009;694:551–560. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Jaffé HH, Doak GO. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1955;77:4441–4444. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Ferrer C, Echavarren AM. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006;45:1105–1109. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).6% yield of 7 was isolated in the case of Table 1, entry 14.

- (13).Baldwin JE. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1976:734–736. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.