Abstract

Purpose

To characterize the ZBED4 cDNA identified by subtractive hybridization and microarray of retinal cone degeneration (cd) adult dog mRNA from mRNA of normal dog retina.

Methods

The cDNA library obtained from subtractive hybridization was arrayed and screened with labeled amplicons from normal and cd dog retinas. Northern blot analysis was used to verify ZBED4 mRNA expression in human retina. Flow cytometry sorted peanut agglutinin (PNA)-labeled cones from dissociated mouse retinas, and quantitative RT-PCR (QPCR) was used to measure ZBED4 mRNA levels in these cone cells. Immunohistochemistry localized ZBED4 in human retinas. Expression of ZBED4 mRNA transiently transfected into HEK293 cells was analyzed by immunofluorescence. ZBED4 subcellular localization was determined with Western blot analysis.

Results

One of 80 cDNAs differentially expressed in normal and cd dog retinas corresponded to a novel gene, ZBED4, which is also expressed in human and mouse retinas. ZBED4 mRNA was found to be present in cone photoreceptors. When ZBED4 cDNA was transfected into HEK293 cells, the expressed protein showed nuclear localization. However, in human retinas, ZBED4 was localized to cone nuclei, inner segments, and pedicles, as well as to Müller cell endfeet. Confirming these immunohistochemical results, the 135-kDa ZBED4 was found in both the nuclear and cytosolic extracts of human retinas. ZBED4 has four predicted DNA-binding domains, a dimerization domain, and two LXXLL motifs characteristic of coactivators/corepressors of nuclear hormone receptors.

Conclusions

ZBED4 cellular/subcellular localization and domains suggest a regulatory role for this protein, which may exert its effects in cones and Müller cells through multiple ways of action.

Gene expression is mediated by the coordinated action of regulatory factors that bind to specific DNA or RNA sequences or interact with proteins. Zinc-finger proteins are one of the most common regulatory factors in eukaryotes. One subclass of these proteins has the recently described BED finger DNA-binding domain, characterized by the signature Cx2CxnHx3–5[H/C] (xn is a variable spacer) and the presence of two highly conserved aromatic amino acids (tryptophan and phenylalanine) at its N terminus. BED finger proteins are thought to function as either transcription activators or repressors by modifying local chromatin structure on binding to GC-rich sequences.1–3

Although cones are our most used photoreceptors, their relative paucity in the mammalian retina in comparison to rods has delayed the study of their molecular nature. In our attempt to find new genes expressed in cones, subtractive hybridization was performed using normal and cone degeneration (cd) adult dog retinal mRNA libraries. As a result, a transcript coding for a novel BED finger protein was identified. We report on the cloning and characterization of the ZBED4 (KIAA0637) cDNA and its encoded protein, which in human retina is expressed in cones and in Müller cell endfeet. Our results add one more gene to the list of those expressed in cones that can be screened for mutations in the DNA of patients affected with cone and cone–rod dystrophies. In addition, further study of ZBED4 will provide an understanding of the mechanisms by which this protein contributes to normal visual function.

Methods

Animal and Human Tissues

C57Bl/6J and rd mice were obtained from our colonies, bred from stock originated at the Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Mouse eyes were quickly enucleated after death and the retinas dissected and frozen. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the approved UCLA Animal Care and Use Committee protocol and the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. Retinas from 2-year-old normal and cd dogs were kindly provided by Gustavo Aguirre (University of Pennsylvania, School of Veterinary Medicine). Healthy human donor eyes were obtained from the National Disease Research Interchange (Philadelphia, PA) and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. The donor eyes were managed in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

RNA Isolation

Total RNA was extracted from mouse and human retinas (TRIzol; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Poly A+ RNA was obtained with an mRNA purification kit (Oligotex; Qiagen, Valencia, CA). RNA quality was assessed with a bioanalyzer (model 2100; Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA), quantified (NanoDrop spectrophotometer; NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE), and stored at −80°C.

Microarray Construction

Representational difference analysis (RDA) subtraction of mRNAs from adult normal and cd dog retinas was performed as previously described.4 The output of the second round of RDA was subcloned using a cloning kit (TOPO TA; Invitrogen) to create a minilibrary in a bacterial host. Following the well-established protocol of Weldford et al.,5 2000 clones were randomly picked and then transferred into 96-well plates containing glycerol-based medium for growth and long-term storage at −80°C. The individual inserts from each colony were amplified by using vector-specific primers to generate sufficient material for cDNA microarray printing. Microarrays were prepared in the UCLA Microarray DNA Facility, as previously described.5,6

Probe Labeling and Hybridization to Microarrays

Two micrograms of normal and cd dog RDA amplicons were labeled with Cy3- and Cy5-dCTP, respectively, using random primers and Klenow enzyme.6 Arrayed cDNAs were first hybridized with these labeled amplicons and 40 of the clones that had the brightest signal with the normal amplicons were sequenced yielding only eight unique fragments. These were mixed and used as a probe for repetitive hybridization of the arrayed library, eliminating in this way a large number of clones and creating a nonredundant set. From this set, only the normal and cd mRNAs that were differentially expressed were sequenced (ABI Prism 3100 Genetic Analyzer; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Microarray Image Acquisition and Data Analysis

The image corresponding to each fluorophore was captured by using an epiconfocal scanner (GMS 418; Affymetrix, Palo Alto, CA) at a resolution of 10 nm and analyzed (Scanalyze software; version 2.44).7 Hybridization signals for each probe were normalized using the Cy5/Cy3 intensity ratio of a housekeeping gene, GAPDH, which was also spotted onto the glass microarrays.

RT-PCR and Cloning

Total adult mouse retinal RNA was treated to eliminate possible genomic DNA contamination (Turbo DNA-free kit; Ambion, Austin, TX) and then reverse transcribed (Superscript II reverse transcriptase; Invitrogen) with oligo(dT) primers. PCR was performed as follows using a polymerase mix (Advantage 2; BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ), 0.2 mM dNTP and 0.2 μM appropriate PCR primers: 94°C for 2 minutes; 35 cycles at 95°C for 30 seconds, 60°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 1 minute, followed by 72°C for 10 minutes. Purified PCR products were cloned into the pCRII vector (TOPO cloning kit; Invitrogen) and sequenced.

Northern Blot Analysis

Two micrograms of polyA+ RNA obtained from human retinal tissue and Y79 retinoblastoma (Y79) cells were electrophoresed on 1.2% denaturing formaldehyde agarose gels and transferred to membranes (Hybond N+; Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). Human retinal cDNA fragments amplified from the 5′ (HZB4) or 3′(HZB22) sequences of ZBED4 (Table 1) were labeled with 32P-dCTP and used as probes in the hybridizations.6

Table 1.

PCR Primers

| Primer | Forward | Reverse | Fragment Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| HZB4 | 5′-CAGCCGGAGTAGTTATGGTCA-3′ | 5′-GCAGACACACTGCCATTTTC-3′ | 557 |

| HZB22 | 5′-GCGTTAGCAGCCTGTACCA-3′ | 5′-AATGCCACGTCTCTGTCGTA-3′ | 532 |

| KpnI-ZB-SmaI | 5′-TTGGTACCTATGGAGGATAAGCAAGAAAC-3′ | 5′-ACATCTTCCCGGGATACATC-3′ | 1232 |

| SmaI-ZB-HindIII | 5′-TATCCCGGGAAGATGTGTCCA-3′ | 5′-GAAGCTTTGTAGCGAGGGTC-3′ | 1825 |

| Pf1M1-ZB-NotI | 5′-CAAGAGCCAGAGGATGGTGCAGAACTTAC-3′ | 5′-TGGCGGCCGCTCATCAATACTGAAAGCATATTAAAG-3′ | 985 |

| ZB-38 (ZBED4) | 5′-TCGTGGCCTGGGCTGTCTACCTTA-3′ | 5′-GGGCTTCTGAAAACGCACCTTGAC-3′ | 382 |

| ZB-27 (ZBED4) | 5′-GCTCACTGGGTCACCTTCGCATCC-3′ | 5′-CCAGGCTTCCCACCAACACTCCAG-3′ | 144 |

| mA1 (mouse β-actin) | 5′-GACATCCGTAAAGACCTCTAT-3′ | 5′-TTGATCTTCATGGTGCTAGGA-3′ | 122 |

| mA2 (mouse β-actin) | 5′-CCTAAGGCCAACCGTGAAAAGATG-3′ | 5′-ACCGCTCGTTGCCAATAGTGATG-3′ | 430 |

| PDEα | 5′-ATCTTGGAAAGGCATCATTTGG-3′ | 5′-GCGATTCAGGTTCTGGAAGATATT-3′ | 81 |

| PDEα′-1 | 5′-AAGAGAACCATGTTTCAAAAGATC-3′ | 5′-GGAGGTTACATATTTGATGGTTTCTTC-3′ | 81 |

| PDEα′-2 | 5′-CTGGGGGTGATCTTCAAAAAG-3′ | 5′-GTTCACTGCCATGACCACAG-3′ | 498 |

Quantitative Real-Time RT-PCR

QPCR was performed on first-strand cDNAs as previously described.8 Primers for selected genes were designed using Primer 3 Internet software (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/provided in the public domain by the Whitehead Institute, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA) and synthesized by Invitrogen (Table 1).9 Briefly, the QPCR reaction was performed in SYBR Green master mix and the corresponding primer sets, using a quantitative PCR system (MX3000P; Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The melting curves of PCR products were monitored to ensure that a single melting curve was obtained. For analysis of the real-time PCR data, signals from each sample were normalized to values obtained for a housekeeping gene, β-actin, which was assayed simultaneously with experimental samples. Primer pairs were subjected to an efficiency test described in ABI’s User Bulletin 2. For those primer pairs with a very close efficiency, duplicate PCR reactions were performed, and the mean of the two reactions was used to calculate the relative gene expression (x-fold change) between the test and control samples. For this, the comparative threshold cycle (Ct) method (ΔΔCt) was used, which corrects for any difference in the expression of the internal normalization gene (β-actin). For primer pairs with different efficiencies, the relative expression level of the experimental to the control samples was obtained by using a standard curve for each target gene. This curve was generated with 10-fold serial dilutions of the normal cDNA samples ranging from 0.01 to 100 ng.

Cell Dissociation and Flow Cytometry

Mouse retinas (40 –90 days old) were digested with papain (15 U/mL). Dissociated cells were collected by centrifugation (800 rpm, 10 minutes), resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 1% BSA, and incubated with diluted (1:250) FITC-conjugated peanut agglutinin (PNA; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 30 minutes at room temperature. The cells were then washed with PBS/1% BSA, adjusted to 1 × 106 cells/mL, immediately sorted by flow cytometry (FACScan; BD Biosciences), and analyzed (Cellquest software; BD Biosciences). Sorted cells were collected by centrifugation and cDNAs were synthesized (One-Step Cells-to-cDNA II kit; Ambion) and subjected to QPCR with primer sets PDEα, ZB-27, PDEα′-1, and mA1 (Table 1). All experiments were repeated at least three times, and the results were corroborated using different primer sets: ZB-38, mA2, and PDEα′-2 (Table 1).

In Situ Hybridization

In situ hybridization using 8-μm frozen sections of human retina embedded in OCT was performed as previously described.10 Two fragments of the human ZBED4 cDNA, one generated with the HZB22 (532 bp) and the other with the HZB4 (557 bp) sets of primers (Table 1) were subcloned into the pCRII plasmid vector (Invitrogen) for generation of riboprobes. The antisense and sense digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled RNA riboprobes were synthesized with SP6 and T7 RNA polymerases (according to the DIG Labeling Kit protocol; Roche, Indianapolis, IN) and purified by spin columns (NucWay; Ambion). Sections were permeabilized with proteinase K (1 μg/mL). Prehybridization was performed at 70°C for 30 minutes in 50% formamide, 5× SSC, 50 μg/mL yeast RNA, 50 μg/mL heparin, and 1% SDS mixture, and hybridization took place overnight at 70°C in a humidified chamber. Sections were then washed with 5× SSC and 1% SDS in 50% formamide at 70°C, 2× SSC in 50% formamide at 65°C, and Tris-buffered saline-0.1% Tween-20 at room temperature. Sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated sheep anti-DIG antibody (1:200; Roche) in 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) 140 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 1% Tween-20, and 1% sheep serum; washed; and incubated with nitro-blue tetrazolium (NBT) and 5-bromo-4 chloro-3 indolyl phosphate (BCIP) to visualize the mRNA. The reaction was stopped with acidic PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20.

Expression Construct

To produce full-length protein, three ZBED4 cDNA fragments were amplified by RT-PCR from mouse retinal RNA using three primer sets containing the desired restriction enzyme recognition sites (KpnI-ZB-SmaI, SmaI-ZB-HindIII, and Pf1M1-ZB-NotI; Table 1). The resultant PCR products were purified with the PCR gel extraction kit (Qiagen) and cloned into the pCRII vector (Invitrogen). All three recombinants were restriction mapped, and those containing the expected insert size were sequenced, digested with the appropriate restriction enzymes, and subcloned in order into the pcDNA4/HisMax A vector between its KpnI/NotI cloning sites. The CMV promoter of this vector drove expression of the ZBED4 fusion protein with the Xpress epitope at its N terminus (see Fig. 5A).

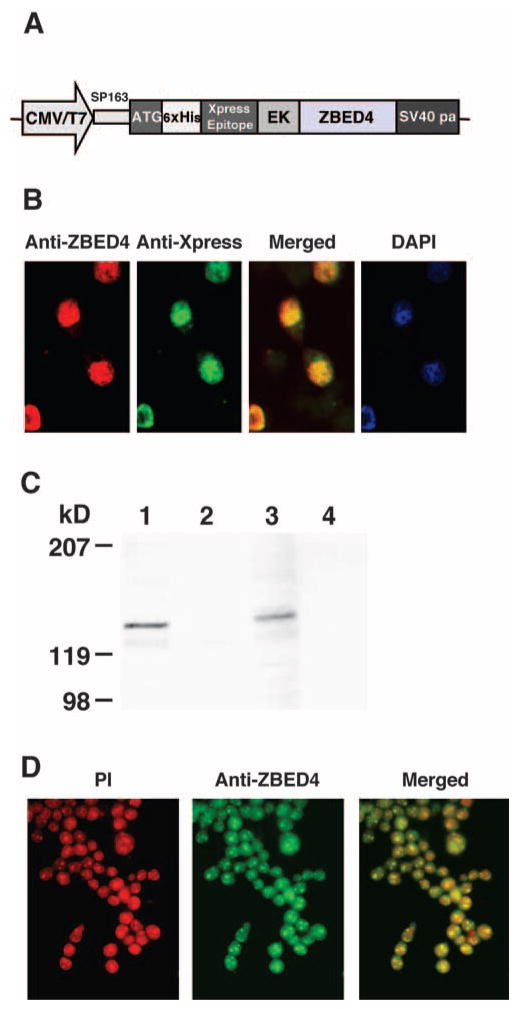

Figure 5.

Distribution of expressed ZBED4 in HEK293. (A) ZBED4 expression construct. (B) Immunocytochemical detection of the ZBED4 protein after transient transfection of the expression vector into HEK293 cells. Cells were double stained with antibodies against ZBED4 and Xpress and the resultant images were merged. Nuclear localization of expressed ZBED4 was detected by both antibodies and confirmed by staining with DAPI. (C) Western blot of nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts of HEK293 cells transfected for 24 or 72 hours. The blot was hybridized with anti-Xpress antibody. The expressed protein was present in the nuclear extract, confirming its immunocytochemical localization. Lanes 1 and 3: nuclear extracts; lanes 2 and 4: cytosolic extracts; lanes 1 and 2: extracts obtained after transfecting cells for 24 hours; lanes 3 and 4: extracts obtained after transfecting cells for 72 hours. (D) Localization of ZBED4 protein in Y79 cells. Note the granular pattern of ZBED4 staining in the nuclei.

Transient and Stable Transfections

Y79 retinoblastoma (Y79) and human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and were grown and transfected as previously described,10 using the pcDNA4/HisMax-ZBED4 expression construct and a transfection reagent (PolyFect Transfection Reagent; Qiagen). All experiments included the pcDNA4/HisMax plasmid without insert as an internal normalization control. Cells were harvested 24, 48, and 72 hours after transient transfection for analysis of newly synthesized protein. Linearized plasmid was used to achieve stable transfection of HEK293 cells, and positive clones were selected (Zeocin; Invitrogen).

Generation of Anti-ZBED4 Antibodies

Two ZBED4 peptides containing amino acids 8–25 (N terminus) and 1061–1083 (C terminus) were synthesized and used to immunize rabbits to generate anti-ZBED4 antibodies. These were affinity purified (ProSci, Poway, CA).

Protein Extraction and Immunoblot Analysis

Nuclear and cytoplasmic protein extracts from transfected cells, mouse thymus, and human retinas were prepared with nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction reagents (NE-PER; Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). Fifty micrograms of extracted proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE on 7.5% gels (Pierce Biotechnology). Blots were incubated with primary antibodies (1:1000 dilution) and secondary anti-rabbit IgG antibodies labeled with alkaline phosphatase (1:5000 dilution; Vector Laboratories). Western blots were visualized with either of two kits (the Amplified-Alkaline Phosphatase kit; BioRad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, or the Enhanced Chemiluminescence kit [ECL]; Amersham).

RNA Interference

Three siRNA sequences were chosen from the ZBED4 open reading frame (GenBank Accension No. NM014838 and gene ID9889) to target ZBED4: nt 2589–2601, 5′-GGUAUGUAUGAUAAUGUGA-3′ (S1); nt 548–566, 5′-GGAAGAUGAUGAUGGAAUU-3′ (S2); and nt 608–626, 5′-GGAGGACAUGAAGCAGACA-3′ (S3). The dsRNA nucleotides were chemically synthesized and annealed by Ambion, Inc. GAPDH siRNA was used as the positive control; the three negative controls were (1) cells transfected without addition of siRNA, to determine any nonspecific effects that could be caused by the transfection reagent; (2) cells transfected with a nonsilencing siRNA with no homology to any known mammalian gene, to determine whether changes in gene expression were nonspecific; and (3) nontransfected cells to allow measurement of the basal level of gene expression.

The day before transfection, 2× 105 HEK293 or Y79 cells were seeded into six-well plates with culture medium containing serum and antibiotics. The next day, 12 μL of transfection reagent (HiPerfect; Invitrogen) was added to 300 ng siRNAs in 100 μL culture medium without serum. The samples were incubated for 5 to 10 minutes at room temperature to allow the formation of transfection complexes. The complexes were added drop-wise onto 50% to 80% confluent cells to a final siRNA concentration of 10 nM. Transfected cells were harvested after 24, 48, and 72 hours to monitor gene silencing by QPCR and Western blot analysis.

Immunostaining of Cultured Cells

Transfected HEK293 or Y79 cells on coverslips were permeabilized with 100% methanol for 6 minutes at −20°C, rinsed three times in PBS, blocked with 3% BSA in PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 (PBST) for 45 minutes, and incubated for 2 hours with N terminus anti-ZBED4 rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:200 dilution) and subsequently 1 hour with fluorescein- or rhodamine-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Next, the transfected cells were incubated 1 hour with a mouse monoclonal antibody (1:100 dilution, anti-Xpress-FITC; Invitrogen). The cells were washed three times in PBST, stained with propidium iodide (PI) or with 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) for nuclei detection and viewed by fluorescence microscopy.

Immunostaining of Human Retinal Sections

Human retinas were embedded in OCT (Sakura Finetek USA., Inc., Torrance, CA). Frozen sections (8 μm) were cut on a cryostat (Leica CM1850; McBain Instruments, Chatsworth, CA). Before immunofluorescent staining, the sections were fixed for 5 minutes at room temperature in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, washed with PBS and reacted with the same primary and secondary antibodies described in the prior section. To show the colocalization of ZBED4 with cone cells and Müller cells, sections were also incubated with rhodamine-conjugated PNA (1:250, 1 hour; Vector Laboratories, catalog no. RL-1072) and goat anti-human vimentin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, catalog no. V-4630), respectively, along with the corresponding secondary antibodies. Images were obtained with a digital camera (MagnaFire; Optronics, Goleta, CA) attached to a microscope (model BX40; Olympus USA, Melville, NY) and were merged using the camera’s software (MagnaFire 2.1; Optronics). Negative controls (preimmune serum instead of primary antibody or omission of primary antibody) were included with each experiment. ZBED4 rabbit polyclonal antibody pre-absorbed with ZBED4 peptide was used to stain some tissues.

Database Analyses

Amino acid identity/similarity searches were performed using the National Center for Biotechnology (NCBI) Database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST), the NCBI BLAST 2 at the Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics site (http://au.expasy.org/tools/blast/), and the University of California at Santa Cruz genome Bioinformatics (http://genome.ucsc.edu). Secondary structure predictions were made using the PSIPRED method at http://bioinf.cs.ucl.ac.uk/psipred/psiform.html (University College, London, UK).

Results

Microarray Screening of cDNAs Identifies Clones Expressed in Cone Photoreceptors

Two thousand cDNA clones obtained from the subtraction of cd from normal dog retinal mRNAs4 were screened using microarrays. Eighty nonredundant clones differentially expressed in normal versus cd dog retinas were sequenced. Several of these clones encoded cone-specific proteins (i.e., cone opsin; cone transducin-α2, -β3, and -γ8; and cone cGMP-PDE α′ subunit), and eight clones did not correspond to any characterized gene (Table 2). Their sequences were analyzed using different databases to reveal predicted structures, domains, or specific elements. On the basis of this analysis, we focused our studies on the 6.9-kb ZBED4 cDNA (GenBank accession number NM014838; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Genbank; provided in the public domain by the National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, MD). Since canine tissues were not readily available, our first task was to isolate the mouse and human homologues of this cDNA by RT-PCR and cloning, using the databases’ sequence information. The human ZBED4 gene is 36.2 kb long, has two exons, and maps to chromosome 22.

Table 2.

List of the Isolated cDNAs Resulting from Microarray Analysis of Subtracted Adult Retinal cd Dog mRNAs from mRNAs of Normal Dog Retina

| cDNAs | Number of Isolated cDNA Clones |

|---|---|

| Cone opsin | 3 |

| ATPase, H+ transporting, lysosomal, subunit 1 | 4 |

| Cone transducin α2 | 2 |

| Cone transducin β3 | 1 |

| Cone transducin γ8 | 1 |

| CRX | 2 |

| PDEα′ | 3 |

| Dog Na/Cl dependent taurine | 4 |

| Dog glycoprotein 80 | 5 |

| Dog mitochondrial genome (different regions) | 32 |

| Hydroxyl methylbilane synthase | 1 |

| Kinesin | 6 |

| Phosphatidyl serine receptor (PTDSR) | 2 |

| Ribosomal protein | 2 |

| Vascular protein sorting 35 (VPS 35) | 4 |

| Unknown cDNAs | 8 |

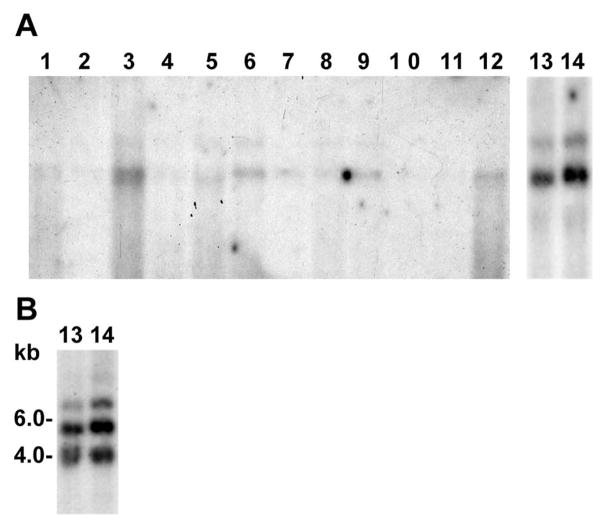

ZBED4 mRNA in Human and Mouse Retinas

The HZB22 probe (Table 1) from the ZBED4 3′ UTR was hybridized to blots containing mRNAs from multiple human tissues (OriGene Technologies, Inc., Rockville, MD), retina and cone-derived Y79 cells. Because the multitissue blot had 2 μg of mRNA per lane, the same amount of human retina and Y79 cell mRNAs was loaded on another blot to be able to compare the hybridization results. Two transcripts were detected in several tissues, approximately 7 and 5 kb long, with the shorter transcript hybridizing more intensely than the longer one (Fig. 1A). Lanes 13 and 14 show that the two transcripts of ZBED4 mRNA are also expressed in human retina and Y79 cells. This second blot was also hybridized with the HZB4 probe from the human ZBED4 5′ UTR (Table 1) and an additional transcript of 4 kb was detected (Fig. 1B). Our results are in agreement with what is now found in the NCBI database, where three ZBED4 mRNAs are described (accession numbers NM014838, BC167155, and BC117670). These three transcripts have the same open reading frame encoding 1171 amino acids (predicted molecular mass of 130 kDa) and vary in the length of their 5′ and 3′ UTRs. Of note, Northern blot analysis of mouse tissues showed only the ~5-kb transcript and higher expression of ZBED4 mRNA in thymus than in retina (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Northern blot analyses show ZBED4 mRNA in various human tissues and Y79 cells. (A) A human multitissue blot, and a separate blot containing human retina and Y79 cells mRNAs were probed with a 32P-labeled ZBED4 cDNA. Two transcripts were detected when using a 3′ UTR probe (HZB22). (B) An additional 4-kb transcript was detected in retina and Y79 cells when using a 5′ UTR probe (HZB4). Lanes: 1, brain; 2, colon; 3, heart; 4, kidney; 5, liver; 6, lung; 7, muscle; 8, placenta; 9, small intestine; 10, spleen; 11, stomach; 12, testis; 13, retina; and 14, Y79 cells.

ZBED4 mRNA in Mouse and Human Cones

To examine whether ZBED4 mRNA is expressed in photoreceptors, we performed RT-PCR using 80-day-old normal and mutant rd mouse retinas. The rd mouse is affected by an early-onset photoreceptor degeneration, with rods degenerating quickly after postnatal day 8 and no longer present in the 30-day retina. In contrast, cones degenerate at a much slower rate and are still detected in the retina by postnatal day 80. Cells of the inner retinal layers show morphologic changes several months after the rd photoreceptors have died.11,12 Therefore, comparison of the expression of ZBED4 and the rod-specific PDEα and cone-specific PDEα′ mRNAs in normal and rd 80-day-old retinas, allowed us to determine ZBED4 mRNA presence in mouse photoreceptor cells and also to discriminate its localization between rods and cones. As expected, no PDEα transcript and lower than normal levels of PDEα′ mRNA were detected in the 80-day-old rd retina (Fig. 2A). ZBED4 showed significantly less mRNA in rd than in normal retina. These results suggest that the ZBED4 transcript is expressed in cone photoreceptors and possibly in cells of the inner retinal layers.

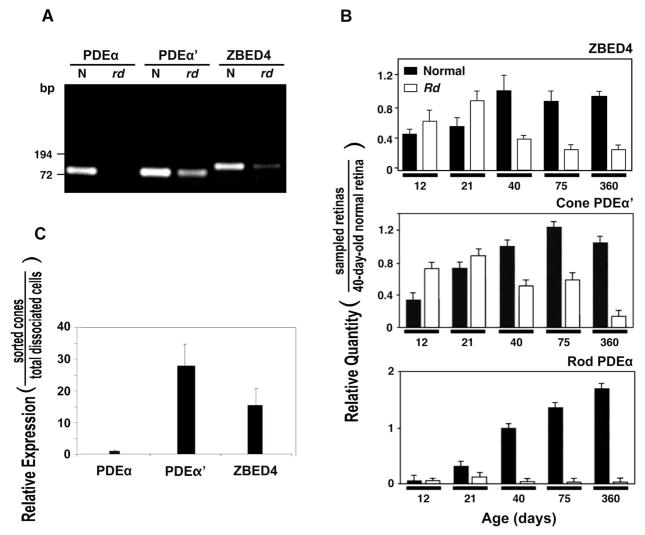

Figure 2.

Expression level of ZBED4 and cell-specific marker mRNAs in normal and rd mouse retinas and in cone-sorted cells. (A) RT-PCR amplification of 80-day-old normal and rd mouse retinal mRNAs using primer sets, PDEα (for PDEα) and PDEα′-1 (for PDEα′) and ZB27 (for ZBED4). The resulting RT-PCR products were separated on a 1.2% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide. ZBED4 is expressed in rd retina but at a lower level than in normal retina, similar to the expression of PDEα′, suggesting the presence of ZBED4 mRNA in cones but not ruling out its expression in the inner retina. (B) Quantitative real-time RT-PCR. Levels of ZBED4 mRNA in normal and rd mouse retinas at different times of postnatal development relative to those of 40-day-old normal retina were compared to the relative levels of cell-specific markers expressed in the same samples (normalized to β-actin mRNA level using primer set mA1; Table 1). Rod-specific marker: PDEα; cone-specific marker: PDEα′. (C) Relative expression of rod PDEα, cone PDEα′, and ZBED4 mRNA between flow cytometry–sorted mouse cones and dissociated retinal cells measured by QPCR using β-actin cDNA as normalizer. The primer sets are described in Table 1.

Quantification of the relative amount of ZBED4, PDEα, and PDEα′ mRNAs at different times during postnatal development in normal and rd mouse retinas showed that the ZBED4 mRNA level is not significantly different from normal in rd retinas during rod degeneration (between P12 and P21) when the PDEα level is much lower in rd than in control retinas (Fig. 2B). But ZBED4 mRNA decreases considerably at the time when cones begin degenerating (between P21 and P40), as it happens with cone-specific PDEAα′ mRNA. Since ZBED4 mRNA level does not vary much between 40 and 360 days in normal and rd retinas, it suggests the presence of some ZBED4 mRNA in the inner retina.

Further studies using QPCR on mouse cone cells sorted by activated flow cytometry supported the predominant expression of ZBED4 in cones over rods. Dissociated retinal cells were labeled with FITC-conjugated PNA (PNA binds preferentially to galactosyl (β-1,3) N-acetylgalactosamine, which is present in the matrix surrounding cones but not rods) and sorted by flow cytometry. Of the total dissociated cells, 4.23% were cones, in agreement with the number of cones known to be present in mouse retina. QPCR using mRNAs of sorted and dissociated retinal cells and appropriate primers for ZBED4, cone PDEα′, and rod PDEα mRNAs showed, as expected, barely detectable rod PDEα mRNA and approximately 29- and 16-fold more PDEα′ mRNA and ZBED4 mRNA, respectively, than PDEα mRNA in the cone enriched cell fraction (Fig. 2C).

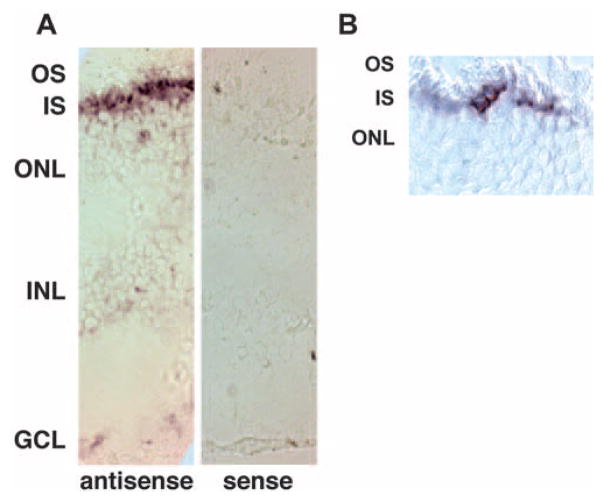

In human retina, in situ hybridization using a ZBED4 antisense riboprobe showed a strong, patchy positive signal in the inner segment of photoreceptor cells, suggesting ZBED4 mRNA presence in cones (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

In situ hybridization shows ZBED4 mRNA localized to inner segments of human photoreceptor cells in human retina. (A) Sections (8 μm thick) of fixed and cryoprotected human retina were hybridized with either antisense or sense ZBED4 digoxigenin (DIG)–labeled riboprobes. ZBED4 message localized to the inner segment of presumptive cone cells; no signal was detected with the sense probe. (B) Higher magnification of a labeled retinal section showing patchy expression of ZBED4, suggesting its expression in cone cells. OS, outer segments; IS, inner segments; ONL, outer nuclear layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; GCL, ganglion cell layer. Magnification: (A) ×200; (B) ×400.

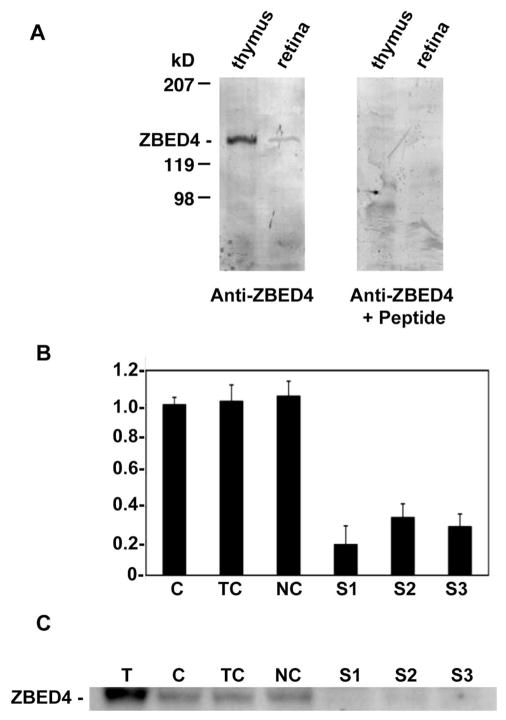

Specificity of ZBED4 Antibodies

The apparent molecular mass of ZBED4 (Fig. 4A) is 135 kDa, as expected from the predicted sequence of the protein. Preabsorption of ZBED4 antibodies with the peptides used to generate them showed no ZBED4 band on Western analysis of both thymus and retina homogenates (Fig. 4) and no immunostaining on retinal tissue sections (see Fig. 6D). Furthermore, successful silencing of ZBED4 expression in HEK 293 (Fig. 4B) and Y79 cells (data not shown) with the use of three siRNAs targeting different regions of ZBED4 mRNA, allowed us to confirm the specificity of our antibodies against ZBED4. In the same Western blot, the protein was recognized by the ZBED4 antibodies in control samples but was absent or barely detected in the lanes containing samples treated with the siRNA oligomer duplexes that had depleted the cellular levels of ZBED4 (Fig. 4C). In contrast, antibodies against GAPDH (Ambion, Inc.) showed comparable amounts of this protein in each lane (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Specificity of anti-ZBED4 antibodies. (A) Protein extracts from both thymus and retina were separated on a Tris/Tricine-buffered 6% acrylamide/3% cross-linking gel and transferred onto PVDF membranes. Blots were incubated with the N terminus ZBED4 antibody (left) at a 1:3000 dilution. For the competition reaction (right), the antibody was incubated overnight with a 3000 molar excess of the peptide used to generate it. The labeled band that corresponds to ZBED4, apparent molecular mass of 135 kDa, is absent in the anti-ZBED+peptide blot. Similar results were obtained with the C terminus ZBED4 antibody. (B, C) Y79 cells were transiently transfected with siRNA duplexes targeted to the 5′ or 3′ regions of ZBED4 mRNA. (B) Ninety-six hours after transfection, total RNA was extracted, reverse transcribed, and subjected to QPCR. The level of mRNA expression in all samples is relative to that in control cells (C) and shows the silencing of ZBED4 in HEK 293 cells after transiently transfecting all three siRNAs. ZBED4 antibodies barely detected or did not detect at all the expression of ZBED4 in the silenced samples. C, control cells; TC, cells with transfection reagent only; NC, negative control (totally unrelated to ZBED4 siRNA); S1, S2, S3, double-stranded ZBED4 RNA oligomers (siRNAs). (C) Protein extracts from transfected HEK 293 cell lysates were assayed for ZBED4 gene silencing by Western blot analysis.

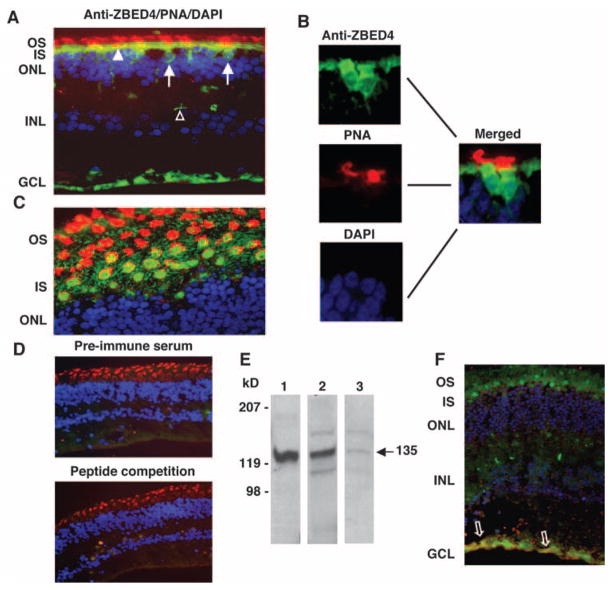

Figure 6.

Localization of ZBED4 in human retina. (A, C) Human retinal sections were double-stained with N terminus ZBED4 antibody followed by FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (green), rhodamine-conjugated PNA (red), and DAPI (blue). (A) Cone nuclei (arrows) and inner segments (arrowheads) are stained green, and the cone matrix is stained red. Note also the anti-ZBED4 staining of the innermost layer of the retina and of the cone pedicles (open arrowhead). (B) Magnified images individually stained with anti-ZBED4, PNA, and DAPI with the use of appropriate filters, and the merging of the three images. (C) An obliquely cut retinal section shows the cone inner segment localization of ZBED4 surrounded by PNA-stained cone extracellular matrix. OS, outer segments; IS, inner segments; ONL, outer nuclear layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; GCL, ganglion cell layer. (D) Top: section incubated with rabbit preimmune serum, rhodamine-conjugated PNA and DAPI. Bottom: section incubated with ZBED4 antibody that had been absorbed with the ZBED4 peptide used to generate it, rhodamine-conjugated PNA and DAPI. The absence of ZBED4 staining validates the ZBED4 antibody specificity. (E) Western blot of proteins from the nuclear extract of mouse thymus (lane 1) and from the nuclear (lane 2) and cytosolic (lane 3) fractions of human retina. ZBED4 (arrow) is very abundant in mouse thymus nuclei; therefore, it was used as a positive control in all Western blot analyses. (F) An obliquely cut human retinal section double-labeled with rabbit polyclonal anti-ZBED4 (green) and anti-human vimentin (red); nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Arrows: colocalization of vimentin and ZBED4 in Müller cell endfeet. Magnification: (A, D, F) ×400; (C) ×600.

Subcellular Localization of ZBED4 in Cultured Cells

HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with a ZBED4 expression construct tagged at the N terminus with both Xpress and poly-histidine (6-His) epitopes (Fig. 5A). The expressed fusion protein was localized to the nuclei of transfected cells using anti-Xpress-FITC mouse monoclonal and anti-ZBED4 polyclonal antibodies (Fig. 5B). This subcellular localization was corroborated on Western blots of subcellular fractions of transfected cells, using the same anti-Xpress (Fig. 5C). Endogenous ZBED4 was also localized to the nucleus of permeabilized Y79 cells, showing a granular pattern (Fig. 5D).

ZBED4 Protein in Nuclei and Cytoplasm of Cones and in Müller Cell Endfeet of the Human Retina

Immunohistochemistry was performed on sections of three different donor human retinas. ZBED4 was present in the nucleus and inner segment of cones, in cone pedicles, and in the innermost retinal layer (Fig. 6A). It was totally absent from the outer segments (stained with rhodamine-conjugated PNA). Figure 6B shows the individually magnified images (anti-ZBED4, PNA, and DAPI) and the merged image of a section containing two cone cells.

To better visualize the exact localization of ZBED4, oblique sections of the retina were stained as described earlier. Figure 6C clearly shows ZBED4 in the inner segments of cones, which are surrounded by the PNA-labeled matrix. Sections stained with preimmune serum and with antibody against ZBED4 that had been preabsorbed with the peptide used to generate it showed no positive signal (Fig. 6D).

Cellular fractionation of human retinas was performed to separate nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts, followed by Western blot analysis of the samples (Fig. 6E). The ZBED4 antibody specifically identified the 135-kDa protein in both the nuclear and cytosolic extracts of human retina, confirming the immunocytochemical localization of ZBED4 to the nuclear and cytosolic compartments of human cones. The Western blot also showed the presence of two extra bands in the nuclear and cytosolic fractions of human retinal tissue. The origin of these bands remains unknown.

To determine whether the anti-ZBED4 staining of the innermost retinal cell layer was specific for ganglion cells or the endfeet of Müller cells, we used markers of these cell types in double-labeling experiments. Only the antibody against vimentin, a Müller glial cell marker, gave a signal (Fig. 6F). Furthermore, vimentin and ZBED4 colocalized at the Müller cell end-feet.

Discussion

We have isolated and characterized a human cDNA encoding a novel 1171-amino-acid protein, ZBED4, with the typical features of a nuclear regulatory protein. The ZBED4 amino acid sequence contains four zinc-finger BED domains with the characteristic Cx2CxnHx3–5[H/C] signature in the amino-terminal half, an hATC dimerization domain in the carboxyl-terminal region, and two nuclear receptor–interacting modules (LXXLL) at positions 199–203 and 359–363.

The presence of four zinc-finger BED domains suggests that ZBED4 may modulate chromatin structure as part of a coactivator complex and facilitate the activation potential of nuclear receptors and other factors. Another possibility is that ZBED4 may also bind insulator DNA sequences directly assisting in the process of gene transcription.

The hATC dimerization domain of ZBED4 also makes this protein a member of the human hAT transposase family. Yamashita et al.13 reported that the hATC domain in proteins of this family has conserved hydrophobic amino acids that function in self-association, a feature that is essential for nuclear accumulation and DNA binding. We confirmed ZBED4 dimerization, in vivo (data not shown). Furthermore, these authors showed that self-association of hATC-containing proteins is involved in nuclear granular pattern formation. Of interest, we observed a granular pattern in the nuclei of Y79 cells immunostained with ZBED4 antibodies (Fig. 5D). Thus, it is possible that these granular structures result from self-association of ZBED4 into a core that further associates with other proteins.

The two nuclear receptor–interacting modules (LXXLL) of ZBED4 are characteristic of coactivators/corepressors of nuclear hormone receptors (NHRs).14 –16 They are known to bind to a hydrophobic cleft in the NHR as a result of a ligand-dependent conformational change, leading to remodeling of chromatin structure, recruitment of RNA polymerase II, and transcriptional activation. In addition to mediating the effects of NHRs, some coactivators also seem to enhance the activity of other transcription factors or to modulate another coactivator’s activity.3 We are currently investigating whether ZBED4 associates directly with ligand-bound NHRs or if it acts in vivo as part of a coactivator complex. Of interest, we previously have shown the presence of estrogen receptor α (ERα) in nuclei of retinal cells, including those of rods and cones17; other NHRs may also be present in cone nuclei. In fact, we found that the promoters of genes encoding the cone proteins PDEα′, transducin-α, and retinoschisin, have not only response elements for ERα but also for the glucocorticoid receptor (unpublished data, 2007).

Our results demonstrating the expression of ZBED4 in cones and Müller cells of human retina make this protein an important candidate for mutations leading to cone and cone–rod dystrophies and other inherited retinal degenerations. Furthermore, the domains and motifs in ZBED4 amino acid sequence, as well as its subcellular localization in both the nuclei and cytoplasm of human cones, open the possibility of ZBED4’s involvement in the conformational alteration of an NHR to expose an activation domain; in the interaction with other proteins to stabilize a multiprotein coactivator complex; in the direct binding to the basal transcription machinery; in the modification of chromatin architecture as a BED domain protein; or in the direct binding to DNA, also through its BED fingers. Therefore, ZBED4 may exert its effects in the retina through multiple ways of action. Future studies based on the data presented herein will elucidate the possible roles and importance of ZBED4 in retinal function and disease.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from the National Eye Institute EY08285 (DBF) and EY07026 (Training grant) and by a UCLA Dissertation Fellowship (MS).

The authors thank Gustavo Aguirre for providing the dog retinas used in this study.

Footnotes

This work was submitted as partial fulfillment of the requirements for a PhD degree at UCLA (MS).

Disclosure: M. Saghizadeh, None; N.B. Akhmedov, None; C.K. Yamashita, None; Y. Gribanova, None; V. Theendakara, None; E. Mendoza, None; S.F. Nelson, None; A.V. Ljubimov, None; D.B. Farber, None

References

- 1.Aravind L. The BED finger, a novel DNA-binding domain in chromatin-boundary-element-binding proteins and transposases. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:421– 423. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01620-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lam E, Kano-Murakami Y, Gilmartin P, Niner B, Chua N. A metal-dependent DNA-binding protein interacts with a constitutive element of a light-responsive promoter. Plant Cell. 1990;2:857– 866. doi: 10.1105/tpc.2.9.857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mahajan MA, Murray A, Samuels HH. NRC-interacting factor 1 is a novel cotransducer that interacts with and regulates the activity of the nuclear hormone receptor coactivator NRC. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:6883– 6894. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.19.6883-6894.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akhmedov NB, Baldwin VJ, Zangerl B, et al. Cloning and characterization of the canine photoreceptor specific cone-rod homeobox (CRX) gene and evaluation as a candidate for early onset photoreceptor diseases in the dog. Mol Vis. 2002;8:79 – 84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Welford SM, Gregg J, Chen E, et al. Detection of differentially expressed genes in primary tumor tissues using representational differences analysis coupled to microarray hybridization. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:3059 –3065. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.12.3059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saghizadeh M, Brown DJ, Tajbakhsh J, et al. Evaluation of techniques using amplified nucleic acid probes for gene expression profiling. Biomol Eng. 2003;20:97–106. doi: 10.1016/s1389-0344(03)00006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eisen M. http://rana.lbl.gov/EisenSoftware.htm.

- 8.Kramerov AA, Saghizadeh M, Pan H, et al. Expression of protein kinase CK2 in astroglial cells of normal and neovascularized retina. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:1722–1736. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rozen S, Skaletsky HJ. Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. In: Krawetz S, Misener S, editors. Bioinformatics Methods and Protocols: Methods in Molecular Biology. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2000. pp. 365–386. http://jura.wi.mit.edu/rozen/papers/rozen-and-skaletsky-2000-primer3.pdfIn. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lerner LE, Peng GH, Gribanova YE, Chen S, Farber DB. Sp4 is expressed in retinal neurons, activates transcription of photoreceptor-specific genes, and synergizes with Crx. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:20642–20650. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500957200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grafstein B, Murry M, Ingoglia NA. Protein synthesis and axonal transport in retinal ganglion cells of mice lacking visual receptors. Brain Res. 1972;44:37– 48. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(72)90364-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farber DB, Flannery JG, Bowes-Rickman C. The rd mouse story: seventy years of research on an animal model of inherited retinal degeneration. In: Osborne NN, Chader GJ, editors. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research. 1. Vol. 13. New York: Pergamon Press; 1994. pp. 31–64. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamashita D, Komori H, Higuchi Y, Yamaguchi T, Osumi T, Hirose F. Human DNA replication-related element binding factor (hDREF) self-association via hATC domain is necessary for its nuclear accumulation and DNA binding. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:7563–7575. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607180200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heery DM, Kalkhoven E, Hoare S, Parker MG. A signature motif in transcriptional co-activators mediates binding to nuclear receptors. Nature. 1997;387:733–736. doi: 10.1038/42750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Darimont BD, Wagner RL, Apriletti JW, et al. Structure and specificity of nuclear receptor-coactivator interactions. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3343–3356. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.21.3343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McInerney EM, Rose DW, Flynn SE, et al. Determinants of coactivator LXXLL motif specificity in nuclear receptor transcriptional activation. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3357–3368. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.21.3357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ogueta SB, Schwartz SD, Yamashita CK, Farber DB. Estrogen receptor in the human eye: influence of gender and age on gene expression. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:1906 –1911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]