Abstract

Objective

Substrates of placental efflux transporters could compete for a single transporter, which could result in an increase in the transfer of each substrate to the fetal circulation. Our aim was to determine the role of placental transporters in the biodisposition of oral hypoglycemic drugs that could be used as monotherapy or in combination therapy for gestational diabetes.

Study design

Inside-out brush border membrane vesicles from term placentas were used to determine the efflux of glyburide, rosiglitazone, and metformin by P-gp, Breast Cancer Resistance Protein (BCRP), and Multidrug Resistance Protein (MRP1).

Results

Glyburide was transported by MRP1 (43 ± 4%); BCRP (25 ± 5%); and P-gp (9 ± 5%). Rosiglitazone was transported predominantly by P-gp (71 ± 26%). Metformin was transported by P-gp (58 ± 20%) and BCRP (25 ± 14%).

Conclusion

Multiple placental transporters contribute to efflux of glyburide, rosiglitazone, and metformin. Administration of drug combinations could lead to their competition for efflux transporters.

Keywords: efflux transporter, gestational diabetes, oral hypoglycemic agent, placenta

INTRODUCTION

Normal pregnancy is associated with metabolic changes leading to decreased insulin sensitivity and reduced glucose tolerance, however 3– 5% of pregnant women proceed to develop gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM).1 Treatment of GDM includes dietary regulation, exercise, home blood glucose monitoring and in some cases pharmacotherapy with insulin or oral hypoglycemic agents. However, metabolic changes occurring during pregnancy to accommodate the development of the fetoplacental unit usually alter the pharmacokinetics of administered medications, thus requiring dose adjustment. One of the goals of the Obstetric-Fetal Pharmacology Research Unit (OPRU) is to investigate the pharmacokinetics of oral hypoglycemic agents during pregnancy. As a center of the OPRU, our laboratory is investigating the role of the human placenta in the disposition of the oral hypoglycemic drugs: glyburide, metformin, and rosiglitazone.

Placental disposition of a drug depends on many factors including: its physicochemical properties (charge, molecular weight, protein binding); physiological properties of the placenta (blood flow, gestational age); the expression and activity of metabolizing enzymes and efflux transporters. In recent years, a large number of transporters were identified in human placental syncytiotrophoblast.2,3 In general, efflux transporters localized in the apical membranes of the syncytiotrophoblast extrude their substrates (endogenous compounds or medications) from the feto-placental unit to the maternal circulation thus decreasing fetal exposure. P-glycoprotein (P-gp; ABCB1 gene product), multidrug resistance-associated protein 1 (MRP1; ABCC1 gene product) and the breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP; ABCG2 gene product) are highly expressed in placental tissue.4 The activities of P-gp, BCRP, and MRP1 in the fetal-to-maternal efflux of substrates across the apical membrane 5–7 appear to have a major role in protecting the fetus from exposure to xenobiotics and endogenous metabolites present in the maternal circulation.

P-gp, BCRP, and MRP1 have wide and overlapping substrate specificity, and drugs – if co-administered – could compete with each other for one or more of the transporters.8 Therefore, human placental disposition of a drug and its efflux in the fetal-to-maternal direction may differ depending on whether it is used as monotherapy or in combination therapy. The use of combinations of oral hypoglycemic drugs for the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) proved to be effective.9 For example, Glucovance, a combination of metformin and glyburide, is considered safe for use during pregnancy. Furthermore, in patients with inadequate glycemic control despite established glyburide/metformin therapy, the addition of rosiglitazone improves glucose tolerance.10 Due to their effectiveness in the non-pregnant patient, it is plausible that the co-administration of glyburide, rosiglitazone, and metformin may be a therapeutic option for pregnant patients with uncontrolled GDM.

The transplacental transfer of glyburide, rosiglitazone, and metformin have been individually documented using dual perfusion of human placental lobule (DPPL).11–14 Asymmetric placental transfer of these drugs favoring fetal-to-maternal transport and/or low placental tissue accumulation revealed during DPPL suggest the involvement of efflux transporters in their distribution. Indeed, recent investigations indicated a role for placental ABC transporters in the transplacental distribution of glyburide.16,17 However, it remains unclear whether glyburide, rosiglitazone, and metformin are transported by one or more of the same placental transporters. Two medications transferred by the same transporter could, in the case of combination therapy, introduce competition for their efflux and consequently increase their concentration in the fetal circulation. Thus, the aim of this investigation was to identify the involvement of human placental ABC transporters responsible for the efflux of glyburide, rosiglitazone, and metformin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals

[3H]-rosiglitazone (specific activity, 50 Ci/mmol) and [14C]-metformin (specific activity, 50mCi/mmol) were purchased from American Radiolabeled Chemicals, Inc (Saint Louis, MO), and [3H]-glyburide (specific activity, 44.6 Ci/mmol) from Perkin-Elmer (Boston, Mass). All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Dallas, TX) unless otherwise noted.

Clinical Material

Placentas from uncomplicated term pregnancies were obtained immediately after vaginal or abdominal deliveries from the labor and delivery ward of the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX, according to a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB # 02-106). Any evidence or history of maternal infection, systemic diseases, and drug or alcohol abuse during pregnancy excluded the placenta from this investigation.

Preparation of Placental Brush Border Inside-Out Vesicles

Placental brush border membrane inside-out vesicles (IOVs) were prepared according to a previously reported method.8,18 Tissue was dissected from the maternal side and rinsed twice in 0.9% NaCl, transferred to sucrose-HEPES-Tris (SHT) buffer (250 mM sucrose, 10mM HEPES-Tris, pH 7.4), and stirred for one hour to disrupt brush border membranes (all steps in preparation were carried out at 4°C). The tissue lysate was filtered through two layers of woven cotton gauze, and the tissue was discarded. The brush border membrane was isolated using differential centrifugation and re-suspended in SHT buffer with a 26-gauge needle. To maximize the proportion of IOVs, affinity chromatography was used to separate right side out vesicles (ROVs) according to a method previously reported from our laboratory.8

Vesicles were aliquoted and immediately stored at −80°C until use. ATP-dependent transport activity was verified an aliquot from each placental preparation, and those with low or no detectible ATP-dependent transport after thawing were excluded from the pool. The pool was prepared using membrane preparations of 60 placentas obtained from uncomplicated term pregnancies. The large pool size reduces the confounding variable of inter-individual variation in the activity of transporters, and provides multiple and long-term use of the same lot of membranes.

Uptake by Membrane Vesicles

The activity of placental efflux transporters was determined by uptake of the radiolabeled isotopes of [3H]-glyburide, [3H]-rosiglitazone, and [14C]-metformin, by placental IOVs according to a previously reported protocol.18 Each reaction was carried out in buffer (250 mM sucrose, 10 mM HEPES-Tris) containing 4 mM MgCl2, 10 mM creatine phosphate, 100 μg/ml creatine phosphokinase, either 2 mM ATP or 3 mM NaCl, and placental IOVs at a concentration of 0.05 μg/μL (7 μg total protein). The reaction was initiated by the addition of drug ([3H]-glyburide, [3H]-rosiglitazone, or [14C]-metformin, at a final concentration of 100 nM. The concentration of 100nM was chosen based on placental tissue concentration of glyburide and rosiglitazone determined from perfusion experiments.11,13,15 The concentration of metformin was selected in the nanomolar range because organic cation transporters of the placenta are known to transport metformin in the micromolar range and we were aiming to minimize interference from these transporters.19 The reaction was terminated after 1 minute by the addition of 1 mL ice cold buffer; the 1 minute time point was selected from the initial linear portion of the time-dependent transport curve of P-gp substrate, paclitaxel, in placental brush border membrane vesicle preparations.8 Vesicles were isolated by rapid filtration using a Brandel Cell Harvester, and the amount of radiolabeled substrate retained on the filter was determined by liquid scintillation analysis. Active transport was calculated as the difference in the amount of drug uptake in the presence and absence of ATP and expressed as pmol/mg protein*min. P-gp-mediated transport (TP-gp) was determined by the addition of P-gp inhibitor, verapamil (600 μM).20 BCRP-mediated transport (TBCRP) was determined by the addition of BCRP-selective inhibitor, 25 nM KO143.21 MRP1-mediated transport (TMRP1) was determined by the addition of MRP1 inhibitor, indomethacin (100 μM).22 Total ABC protein-mediated transport (TABC) was determined for P-gp, BCRP, and MRP1 using 1 μM KO143.

The effect of metformin on rosiglitazone transport by P-gp was determined using varying concentrations of cold metformin measuring its inhibition of [3H]-rosiglitazone uptake by placental IOVs.

RESULTS

Glyburide Transport

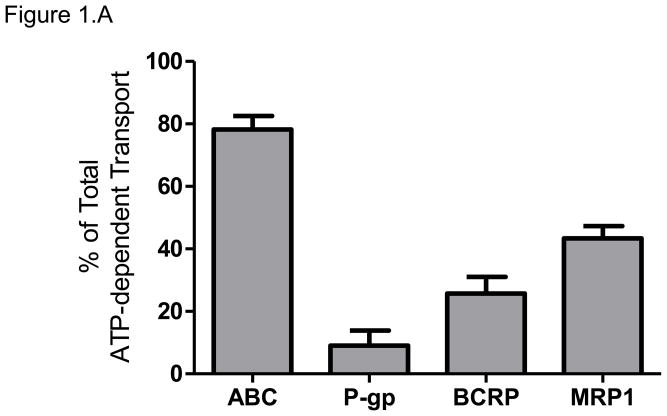

The total ATP-dependent uptake of [3H]-glyburide, at its concentration of 100 nM, by placental IOVs was 3.2 ± 0.3 pmol/mg protein*min. Inhibition of P-gp by verapamil decreased [3H]-glyburide uptake by 9 ± 5%. Inhibition of BCRP by 25 nM KO143 decreased [3H]-glyburide uptake by 25 ± 5%. Inhibition of MRP1 by indomethacin decreased [3H]-glyburide uptake by 43 ± 4%. Total inhibition of P-gp, BCRP, and MRP1 using 1 μM KO143 decreased [3H]-glyburide uptake by 78 ± 4 %. The contributions of each transporter to the total efflux were MRP1>BCRP> P-gp (Figure 1.A).

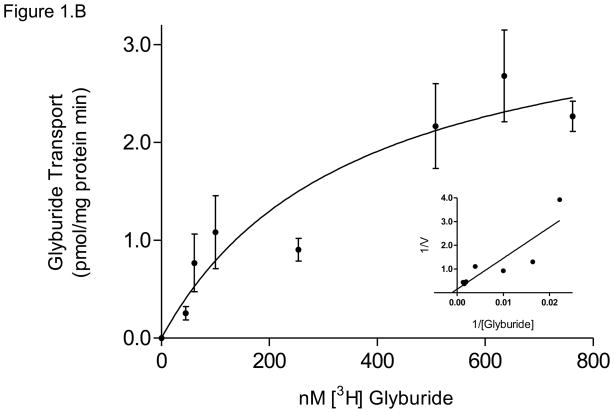

Figure 1. Glyburide efflux by placental ABC Transporters.

(A) The relative contributions of P-gp, BCRP, and MRP1 to glyburide efflux were determined using chemical inhibition of ATP-dependent transport of 100nM [3H]-glyburide in placental IOVs (pool of 60 preparations). Uptake was measured for 1 minute in placental IOVs (protein concentration of 0.05 μg/μL) in the presence/absence of inhibitor selective for P-gp (600 μM verapamil), BCRP (25 nM KO143), MRP1 (100 μM indomethacin), or total P-gp + BCRP + MRP (1 μM KO143).

(B) MRP1 displayed apparent Kt of 360 ± 195 nM glyburide and Vmax = 3.6 ± 0.9 pmol/mg protein*min for ATP-dependent glyburide transport, with corresponding Lineweaver-Burk plot (inset). Data are presented as mean ± SEM of 4–8 experiments.

The activity of MRP1, the major transporter responsible for the efflux of glyburide in this study, exhibited ATP-dependent transport with an apparent Kt of 358 ± 195 nM and Vmax of 3.6 ± 0.9 pmol/mg protein*min (Figure 1.B).

Rosiglitazone Transport

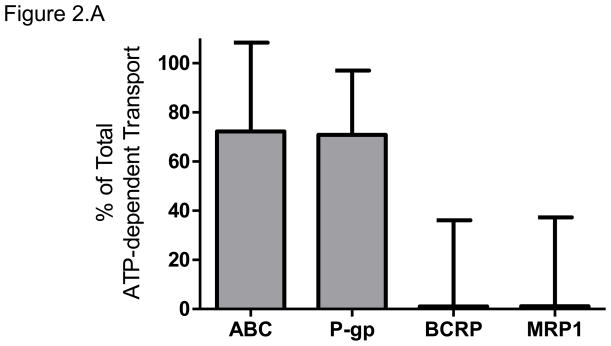

The total ATP-dependent uptake of [3H]-rosiglitazone, at its concentration of 100 nM, by placental IOVs was 1.2 ± 0.2 pmol/mg protein*min. Inhibition of P-gp by verapamil decreased [3H]-rosiglitazone uptake by 71 ± 26%. Inhibition of BCRP by 25 nM KO143 and inhibition of MRP1 by indomethacin had no effect on rosiglitazone uptake. The inhibition of P-gp, BCRP, and MRP using 1 μM KO143 decreased rosiglitazone uptake by 72 ± 36 %. Taken together, P-gp was responsible for of ATP-dependent rosiglitazone efflux, with negligible contributions by BCRP and MRP1 (Figure 2.A).

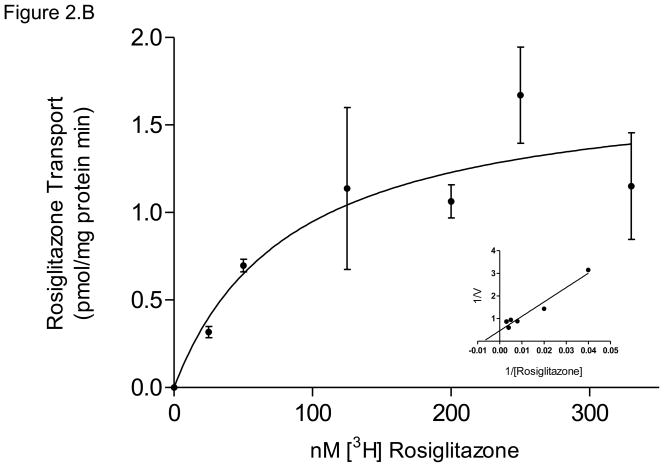

Figure 2. Rosiglitazone efflux by placental ABC Transporters.

(A) The relative contributions of P-gp, BCRP, and MRP1 to rosiglitazone efflux were determined using chemical inhibition of ATP-dependent transport of 100nM [3H]-rosiglitazone in placental IOVs (pool of 60 preparations). Uptake was measured for 1 minute in placental IOVs (protein concentration of 0.05 μg/μL) in the presence/absence of inhibitor selective for P-gp (600 μM verapamil), BCRP (25 nM KO143), MRP1 (100 μM indomethacin), or total P-gp + BCRP + MRP (1 μM KO143).

(B) P-gp displayed apparent Kt of 84 ± 47 nM rosiglitazone and Vmax = 1.7 ± 0.3 pmol/mg protein*min for ATP-dependent rosiglitazone transport, with corresponding Lineweaver-Burk plot (inset). Data are presented as mean ± SEM of 4–8 experiments.

The activity of P-gp, the major transporter responsible for rosiglitazone efflux in this study, exhibited ATP-dependent transport with an apparent Kt of 84 ± 47 nM and Vmax of 1.7 ± 0.3 pmol/mg protein*min (Figure 2.B).

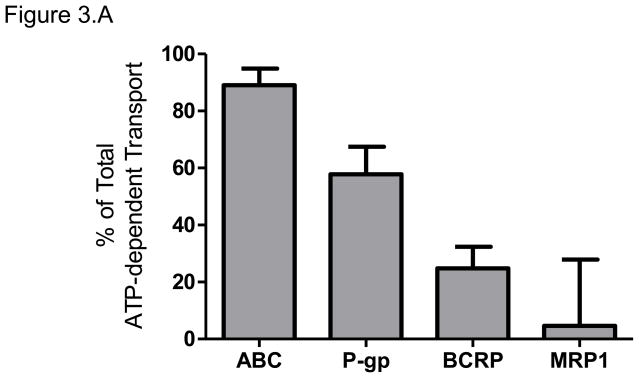

Metformin Transport

The total ATP-dependent uptake of [14C]-metformin, at a concentration of 100 nM, by placental IOVs was 35 pmol/mg protein*min. Inhibition of P-gp by verapamil decreased [14C]-metformin uptake by 58 ± 10%. Inhibition of BCRP by 25 nM KO143 decreased [14C]-metformin uptake by 25 ± 8%. Inhibition of MRP1 using indomethacin had no effect on [14C]-metformin uptake. The inhibition of P-gp, BCRP, and MRP using 1 μM KO143 decreased [14C]-metformin uptake by 89 ± 6 %. Therefore, the majority of ATP-dependent [14C]-metformin effux was achieved by P-gp, followed by BCRP (Figure 3.A).

Figure 3. Metformin efflux by placental ABC Transporters.

(A) The relative contributions of P-gp, BCRP, and MRP1 to metformin efflux were determined using chemical inhibition of ATP-dependent transport of 100nM [14C]-metformin in placental IOVs (pool of 60 preparations). Uptake was measured for 1 minute in placental IOVs (protein concentration of 0.05 μg/μL) in the presence/absence of inhibitor selective for P-gp (600 μM verapamil), BCRP (25 nM KO143), MRP1 (100 μM indomethacin), or total P-gp + BCRP + MRP (1 μM KO143).

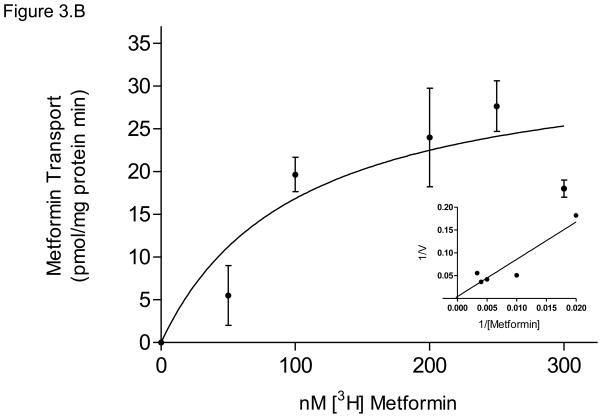

(B) P-gp displayed apparent Kt of 100 ± 85 nM metformin and Vmax = 34 ± 10 pmol/mg protein*min for ATP-dependent metformin transport, with corresponding Lineweaver-Burk plot (inset). Data are presented as mean ± SEM of 4–8 experiments.

The activity of P-gp, the major transporter responsible for metformin efflux in this study, exhibited ATP-dependent transport with an apparent Kt of 100 ± 85 nM and Vmax of 33 ± 10 pmol/mg protein*min (Figure 3.B).

Inhibition of Rosiglitazone Transport by Metformin

The effect of metformin on rosiglitazone transport by P-gp, the transporter responsible for rosiglitazone and metformin efflux in this system, was investigated. Metformin inhibited ATP-dependent transport of [3H]-rosiglitazone by 69 ± 6 % with an apparent IC50 of approximately 600 nM.

COMMENT

The goal of this investigation was to better understand the role of human placenta in fetal exposure to hypoglycemic drugs used in the treatment of GDM. To achieve this goal, we determined the activity of placental ABC transporters in the efflux of glyburide, rosiglitazone, and metformin utilizing inside out vesicle preparations obtained from placental apical membranes. Due to the reversed orientation of the transporters within the inside-out vesicles, transporter uptake of a drug into inverted vesicles represents its efflux activity. The data obtained in this investigation revealed that placental ABC transporters investigated contributed to the efflux (as determined by their uptake in IOVs) of glyburide, rosiglitazone, and metformin to different extents.

Each of the transporters, MRP1, BCRP, and P-gp, extrude glyburide from the syncytiotrophoblast tissue in the fetal-to-maternal direction. Glyburide efflux in IOVs is in agreement with previous evidence of its asymmetric transfer reported from our laboratory and by others. Previously, it was demonstrated that the fetal-to-maternal transfer of glyburide was greater than maternal-to-fetal transfer,15 and significant transfer of glyburide occurs against a concentration gradient from the fetal to the maternal circulation.23 Interestingly, verapamil (an inhibitor of P-gp) did not affect glyburide transfer during its perfusion in a placental lobule, 23 suggesting that only a minor amount of glyburide was transported by P-glycoprotein. In this investigation, we confirmed that P-gp is responsible for a small fraction of glyburide efflux, namely ~9%.

Data sited in this report demonstrated that MRP1 was responsible for the efflux of glyburide and its activity was greater than that of BCRP or P-gp. In most tissues, MRP1 is localized to the basolateral membrane of epithelial cells,24,25 however the placenta provides an exception because MRP1 is also detectable in the apical membrane of syncytiotrophoblast tissue.4,6 The data in this investigation suggest that MRP1 could also have a role in the efflux of compounds in the fetal-to-maternal direction. MRP1 similarly shares efflux function in the blood-brain barrier with P-gp and BCRP, where the three are co-localized in the luminal membrane of brain capillary endothelial cells.26, 27

The data obtained in this investigation indicate that P-gp and BCRP are involved in the efflux of metformin across placental apical membranes, which could explain its asymmetric fetal-to-maternal transfer and limited placental tissue retention observed in perfusion studies.8,9 To our knowledge, this is the first report to identify P-gp as a placental efflux transporter for metformin. Previously metformin was not identified as a P-gp substrate in in vivo investigations of rat intestine,28 or in Caco-2 monolayer composed of human colonic adenocarcinoma.29 However, interspecies and inter-tissue differences exist in the tissue permeability of P-gp substrates and the selectivity/specificity of the inhibitors used.30,31 Moreover, our preparations of human placental brush border membranes allowed the direct measurement of metformin efflux by physiologically-expressed membrane transporters, a determination that is difficult to quantify in vivo or in cancer cell lines. The total transport of metformin (at a final concentration of 100 nM) by the ABC transporters examined equaled 35 pmol/mg protein*min, which represents 10- and 30-fold greater transport than that of glyburide and rosiglitazone transport, respectively. The apparent Kt and Vmax of P-gp -mediated metformin transport (100 ± 85 nM and 34 ± 10 pmol/mg protein*min) are similar to that of the prototypic P-gp substrate, paclitaxel (Kt of 66 ± 38 nM and Vmax of 20 ± 3 pmol/mg protein*min)8 indicating that metformin is a high affinity substrate of placental P-gp. The distribution of metformin in non-placental tissues is significantly influenced by transporters such as Organic Cation Transporter 2 (OCT2) and genetic variation in OCT2 alters metformin biodisposition.32 Since placental P-gp is involved in metformin efflux, and functional polymorphisms in the MDR1 gene encoding P-gp affect its placental expression and transport activity,33 it is plausible that MDR1 genetic variation could significantly influence placental disposition of metformin.

P-gp was the placental transporter responsible for rosiglitazone efflux in apical membrane preparations from syncytiotrophoblast. Evidence from human brain micro vascular endothelial cells (Homes) also supports that P-gp is the major brain-to-blood transporter of rosiglitazone.34 The rate of rosiglitazone transport by P-gp was much lower than metformin (1.7 ± 0.3 vs. 36 ± 15 pmol/mg protein*min), however the two drugs have similar affinity (apparent Kt of 84 ± 47 and 100 ± 85 nM, for rosiglitazone and metformin respectively).

Two P-gp substrates with similar affinity for the transporter could introduce competition for binding and/or transport (i.e., drug-drug interaction) if they are co-administered as medications. Indeed, metformin significantly inhibited the transport of [3H]-rosiglitazone by P-gp in our IOV system. The importance of P-gp in drug–drug interactions has been identified in USFDA guidelines,35 and it is increasingly accepted that co-administration of P-gp substrates can result in competition for efflux which could affect their pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics.36 Thus, if co-administration of rosiglitazone and metformin is possible during pregnancy, the potential competition for P-gp-mediated efflux and ultimately increased placental transfer of one or both of these compounds should be considered.

In summary, the placental ABC transporters investigated (P-gp, BCRP, and MRP1) contribute to the efflux of glyburide, rosiglitazone, and metformin to a different extent. Although the role of other placental transporters cannot be ruled out at this time, this investigation revealed overlapping function of P-gp, BCRP, and MRP1 in placental apical membrane. Overlapping transporter specificity between glyburide, rosiglitazone, and metformin could have consequences if these agents are co-administered. Since transporter-mediated efflux is a determinant of placental transfer, drug-drug interactions involving the process of transporter-mediated efflux could affect the extent of fetal exposure to medications.

Acknowledgments

Supported by Obstetric-Fetal Pharmacology Research Unit (OPRU) Network (#U10H0047891)

The authors thank the Perinatal Research Division for their assistance, and the Publication, Grant, & Media Support of the UTMB Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Supported by the Obstetric-Fetal Pharmacology Research Unit (OPRU) Network (#U10H0047891).

Footnotes

Presentation information: Fast Track publication, Oral Presentation #0049, SMFM Annual Meeting, Friday, Feb 5 2010, Chicago, IL.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Sarah J. HEMAUER, Email: sjhemaue@utmb.edu.

Svetlana L. PATRIKEEVA, Email: svpatrik@utmb.edu.

Tatiana N. NANOVSKAYA, Email: tnnanovs@utmb.edu.

Gary D.V. HANKINS, Email: ghankins@utmb.edu.

Mahmoud S. AHMED, Email: maahmed@utmb.edu.

References

- 1.Gabbe SG, Mestman JH, Freeman RK, Anderson GV, Lowensohn RI. Management and outcome of class A diabetes mellitus. Am J Obstet and Gyn. 1977;127:465–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(77)90436-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Syme MR, Paxton JW, Keelan JA. Drug transfer and metabolism by the human placenta. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2004;43(8):487–514. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200443080-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ganapathy V, Prasad PD, Ganapathy ME, Leibach FH. Placental transporters relevant to drug distribution across the maternal-fetal interface. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;294(2):413–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.St-Pierre MV, Serrano MA, Macias RI, et al. Expression of members of the multidrug resistance protein family in human term placenta. Am J Physiol. 2000;279(4):1495–503. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.279.4.R1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maliepaard M, Scheffer GL, Faneyte IF, et al. Subcellular localization and distribution of the breast cancer resistance protein transporter in normal human tissues. Cancer Res. 2001;61(8):3458–3464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flens MJ, Zaman GJ, van der Valk P, et al. Tissue distribution of the multidrug resistance-associated protein. Am J Pathol. 1996;148:1237–1247. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakamura Y, Ikelda S, Fukuwara T, Sumizawa T, Tani A, Akiyama S. Function of P-glycoprotein expressed in the placenta and mole. Biochem Bioph Res Co. 1997;235:849–53. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hemauer SJ, Patrikeeva SL, Nanovskaya TN, Hankins GD, Ahmed MS. Opiates inhibit paclitaxel uptake by P-glycoprotein in preparations of human placental inside-out vesicles. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;78(9):1272–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blonde L, Joyal S, Henry D, Howlett H. Durable efficacy of metformin/glibenclamide combination tablets (Glucovance) during 52 weeks of open-label treatment in type 2 diabetic patients with hyperglycaemia despite previous sulphonylurea monotherapy. Int J Clin Pract. 2004;58(9):820–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2004.00316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dailey GE, 3rd, Noor MA, Park JS, Bruce S, Fiedorek FT. Glycemic control with glyburide/metformin tablets in combination with rosiglitazone in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized, double-blind trial. Am J Med. 2004;116(4):223–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nanovskaya TN, Nekhayeva IA, Patrikeeva SL, Hankins GD, Ahmed MS. Transfer of Metformin across the dually perfused human placental lobule. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:1081–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kovo M, Kogman N, Ovadia O, Nakash I, Golan A, Hoffman A. Carrier-mediated transport of metformin across the human placenta determined by using the ex vivo perfusion of the placental cotyledon model. Prenat Diagn. 2008;28:544–548. doi: 10.1002/pd.2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nanovskaya TN, Patrikeeva S, Hemauer S, et al. Effect of albumin on transplacental transfer and distribution of rosiglitazone and glyburide. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2008;21(3):197–207. doi: 10.1080/14767050801929901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holmes HJ, Casey BM, Bawdon RE. Placental transfer of rosiglitazone in the ex vivo human perfusion model. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:1715–1719. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nanovskaya TN, Nekhayeva IA, Hankins GD, Ahmed MS. Effect of human serum albumin on transplacental transfer of glyburide. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;72:632–639. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gedeon C, Behravan J, Koren G, Piquette-Miller M. Transport of Glyburide by Placental ABC Transporters: Implications in Fetal Drug Exposure. Placenta. 2006;27(11–12):1096–102. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2005.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gedeon C, Anger G, Piquette-Miller M, Koren G. Breast cancer resistance protein: mediating the trans-placental transfer of glyburide across the human placenta. Placenta. 2008;29(1):39–43. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ushigome F, Koyabu N, Satoh S, et al. Kinetic analysis of P-glycoprotein-mediated transport by using normal human placental brush-border membrane vesicles. Pharm Res. 2003;20(1):38–44. doi: 10.1023/a:1022290523347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bourdet DL, Pritchard JB, Thakker DR. Differential substrate and inhibitory activities of ranitidine and famotidine toward human organic cation transporter 1 (hOCT1; SLC22A1), hOCT2 (SLC22A2), and hOCT3 (SLC22A3) J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;315(3):1288–97. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.091223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsuruo T, Lida H, Tsukagoshi S, Sakurai Y. Overcoming of vincristine resistance in P388 leukemia in vivo and in vitro through enhanced cytotoxicity of vincristine and vinblastine by verapamil. Cancer Res. 1981;41(5):1967–1972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allen JD, van Loevezijn A, Lakhai JM, et al. Potent and specific inhibition of the breast cancer resistance protein multidrug transporter in vitro and in mouse intestine by a novel analogue of fumitremorgin C. Mol Cancer Ther. 2002;1:417–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benyahia B, Huguet S, Declèves X, et al. Multidrug resistance-associated protein MRP1 expression in human gliomas: chemosensitization to vincristine and etoposide by indomethacin in human glioma cell lines overexpressing MRP1. J Neurooncol. 2004;66(1–2):65–70. doi: 10.1023/b:neon.0000013484.73208.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kraemer J, Klein J, Lubetsky A, Koren G. Perfusion studies of glyburide transfer across the human placenta: implications for fetal safety. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195(1):270–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borst P, Evers R, Kool M, Wijnholds J. The multidrug resistance protein family. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1461:347–357. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(99)00167-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borst P, Evers R, Kool M, Wijnholds J. A family of drug transporters: the multidrug resistance-associated proteins. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1295–1302. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.16.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Boer AG, Van der Sandt IC, Gaillard PJ. The role of drug transporters at the blood–brain barrier. Annual Reviews in Pharmacology and Toxicology. 2003;43:629–656. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.43.100901.140204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kusch-Poddar M, Drewe J, Fux I, Gutmann H. Evaluation of the immortalized human brain capillary endothelial cell line BB19 as a human cell culture model for the blood–brain barrier. Brain Research. 2005;1064:21–31. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Song NN, Li QS, Liu CX. Intestinal permeability of metformin using single-pass intestinal perfusion in rats. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(25):4064–4070. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i25.4064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Proctor WR, Bourdet DL, Thakker DR. Mechanisms underlying saturable intestinal absorption of metformin. Drug Metab Dispos. 2008;36(8):1650–8. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.020180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suzuyama N, Katoh M, Takeuchi T, et al. Species differences of inhibitory effects on P-glycoprotein-mediated drug transport. J Pharm Sci. 2007;96(6):1609–18. doi: 10.1002/jps.20787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Terasaki T, Iga T, Sugiyama Y, Hanano M. Pharmacokinetic study on the mechanism of tissue distribution of doxorubicin: Interorgan and interspecies variation of tissue-to-plasma partition coefficients in rats, rabbits, and guinea pigs. J Pharm Sci. 1984;73(10):1359–63. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600731008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi MK, Song IS. Organic cation transporters and their pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic consequences. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2008;23(4):243–53. doi: 10.2133/dmpk.23.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hemauer SJ, Nanovskaya TN, Abdel-Rahman SZ, Patrikeeva SL, Hankins GD, Ahmed MS. Modulation of human placental P-glycoprotein expression and activity by MDR1 gene polymorphisms. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009 Nov 5; doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.10.026. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Festuccia WT, Oztezcan S, Laplante M, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma-mediated positive energy balance in the rat is associated with reduced sympathetic drive to adipose tissues and thyroid status. Endocrinology. 2008;149(5):2121–30. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang SM, Temple R, Throckmorton DC, Lesko LJ. Drug interaction studies: Study design, data analysis, and implications for dosing and labeling. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapy. 2007;81:298–304. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou SF. Structure, function and regulation of P-glycoprotein and its clinical relevance in drug disposition. Xenobiotica. 2008;38(7–8):802–832. doi: 10.1080/00498250701867889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]