SYNOPSIS

Objective

Homeless individuals frequently use emergency departments (EDs), but previous studies have investigated local rather than national ED utilization rates. This study sought to characterize homeless people who visited urban EDs across the U.S.

Methods

We analyzed the ED subset of the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS-ED), a nationally representative probability survey of ED visits, using methods appropriate for complex survey samples to compare demographic and clinical characteristics of visits by homeless vs. non-homeless people for survey years 2005 and 2006.

Results

Homeless individuals from all age groups made 550,000 ED visits annually (95% confidence interval [CI] 419,000, 682,000), or 72 visits per 100 homeless people in the U.S. per year. Homeless people were older than others who used EDs (mean age of homeless people = 44 years compared with 36 years for others). ED visits by homeless people were independently associated with male gender, Medicaid coverage and lack of insurance, and Western geographic region. Additionally, homeless ED visitors were more likely to have arrived by ambulance, to be seen by a resident or intern, and to be diagnosed with either a psychiatric or substance abuse problem. Compared with others, ED visits by homeless people were four times more likely to occur within three days of a prior ED evaluation, and more than twice as likely to occur within a week of hospitalization.

Conclusions

Homeless people who seek care in urban EDs come by ambulance, lack medical insurance, and have psychiatric and substance abuse diagnoses more often than non-homeless people. The high incidence of repeat ED visits and frequent hospital use identifies a pressing need for policy remedies.

Cities in the United States reported a 12% increase in homelessness from 2007 to 2008, despite national, state, and local efforts to provide housing.1 In the Annual Homeless Assessment to Congress, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) estimated that 759,000 people were homeless on a single night in 2006.2 Homelessness is associated with significant morbidity and mortality,3 and homeless patients are likely to have multiple acute and chronic health issues. A previous study found that age-adjusted mortality was 3.5 times greater for homeless compared with non-homeless individuals.4 Furthermore, homeless people often have mental illness and substance abuse issues5,6 in addition to being subject to trauma.7

Homeless people are often uninsured and face significant barriers to accessing health care.8 Competing demands for shelter, food, and safety supersede the need to obtain primary medical care for many homeless individuals.9 As a result, homeless individuals will often use the emergency department (ED) for routine, non-emergent medical needs.10–12 Homeless people are three times more likely to use the ED than non-homeless people13 and may contribute to ED overcrowding.14

The often transient or episodic nature of homelessness makes it extremely difficult to characterize this population. Nearly all of the published studies examining ED visits by homeless people are limited to single cities and hospitals,10,13–17 even though the regulatory frameworks for ED practice (e.g., the Emergency Medicine Treatment and Active Labor Act) and for homeless policy itself are developed at the national level. An accurate portrait of the national impact of homelessness on EDs is a necessary prerequisite for informed policy development directed toward improved care for homeless individuals and reduced costs associated with ED use by homeless people.18

We sought to characterize visits made by homeless individuals to urban EDs in the U.S. during a two-year period, and to assess whether homelessness itself, or characteristics commonly associated with homelessness, independently predicted ED use.

METHODS

Design

We performed a descriptive, cross-sectional secondary analysis of the ED components of the 2005 and 2006 National Hospital Ambulatory Care Surveys (NHAMCS-ED).19,20 These surveys are four-stage probability samples of ED visits conducted annually by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) within the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Statistical methods have been published by NCHS.21 The Thomas Jefferson University Hospital Institutional Review Board exempted this study from review.

Sampling is national in scope, but excludes long-stay, federal, military, and Veterans Administration hospitals. NHAMCS-ED obtains nationally representative estimates by randomly sampling at four stages, beginning with geographic units closely related to counties, then hospitals, then emergency service areas within each sampled hospital, and finally individual clinical encounters. In the last stage, patient records are chosen from consecutive visits using a random start followed by every nth patient record. Each ED contributes patients during a four-week period that is repeated every 16 months. Of EDs that were approached, 91% (n=352) and 87% (n=362) participated in the survey in 2005 and 2006, respectively. In the entire U.S., there were 4,014 EDs in 2005 and 4,061 EDs in 2006.22,23 Each encounter yielded a one-page patient record form, which was abstracted from clinical records by local ED personnel trained by field representatives from the U.S. Census Bureau.

Diagnoses and medications were coded, data were edited for consistency, and data entry was subjected to a 10% quality-control check. Item nonresponse rates were generally less than 5%. Exceptions in 2006 were “seen in ED within last 72 hours” (11.0%), “discharged within the last seven days” (25.4%), “length of in-patient stay” (12.3%), “time waiting to see a physician” (13.5%), and “time spent in the ED” (5.2%). The exceptions in 2005 were similar to those in 2006. Some items with nonresponse were imputed. To counter potential imbalances in sampling and produce unbiased annual estimates, weights were assigned to each record. These weights inflate point estimates by reciprocals of selection probabilities, adjustment for nonresponse, population ratio adjustments, and weight smoothing.24 Although survey data collection involved both urban and rural EDs, this analysis was limited to urban ED visits because there were only five patient record forms marked “homeless” from rural EDs.

The NHAMCS-ED first tallied homeless status in 2005 and did not discriminate chronic from short-term homelessness. A patient residence item contained checkboxes for private residence, nursing home, other institution, other residence, or homeless. Of 69,454 forms filled out in 2005 and 2006, 449 were checked as homeless. Given this sample size, we examined bivariate and multivariable associations with a limited group of variables chosen on the basis of a priori clinical relevance rather than empirical strength of association.

Analysis

The analytic dependent variable was homeless status. Predictor variables included a range of characteristics shown to be potentially relevant in homeless service utilization research.8,10,14,15 We used Stata® version 10.0 for all statistical analyses.25 Significance tests and confidence intervals [CIs] were obtained using Stata's “svy” programs (tabulation and logistic regression), which adjust standard errors for correlation within primary sampling units and allow the use of probability weights to obtain national estimates.

RESULTS

There were 234 million weighted ED visits in the U.S. in 2005 and 2006. During this two-year period, ED visits made by homeless individuals from all age groups numbered 1.1 million, or 0.5% of total ED visits. The majority of these (96%) were made by individuals older than 18 years of age. Homeless individuals made 550,000 ED visits (95% CI 419,000, 682,000) annually, or 72 visits per 100 homeless individuals per year during 2005–2006, based on a count of 759,000 people homeless on a single night in 2006.2 In comparison, the overall population made 115.3 million visits annually, or 40 visits per 100 people per year. In 2005, there were 469,000 urban ED visits by homeless people (95% CI 321,000, 616,000). In 2006, the number of homeless visits increased to 628,000 (95% CI 429,000, 828,000).

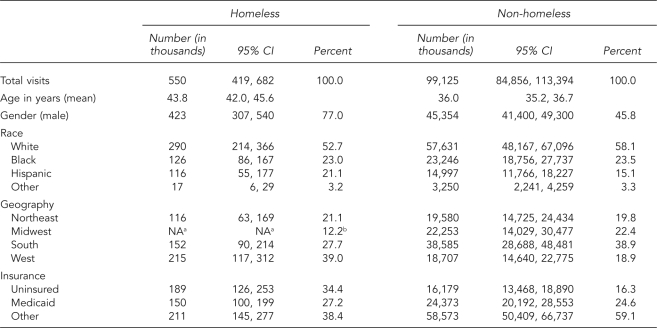

Tables 1 and 2 illustrate bivariate relationships between homeless status and demographic and clinical variables. Homeless ED visitors were older and more often uninsured than non-homeless ED visitors. In unadjusted comparisons, a similar percentage of homeless and non-homeless individuals had Medicaid coverage. Homeless people also arrived more frequently by ambulance and were more often treated for an acute injury, alcohol or other drug use, or psychiatric issues than other people.

Table 1.

Annual emergency department visits, by demographic characteristics and homeless status: NHAMCS-ED, U.S., 2005–2006

aEstimates of the number of homeless visits for the Midwest did not meet standards for reliability or precision as determined by the National Center for Health Statistics.

bBecause precise numbers of Midwestern homeless visits could not be estimated, a percentage is offered based on subtraction of the percentages from the three other regions.

NHAMCS-ED = National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey—Emergency Department

CI = confidence interval

NA = not applicable

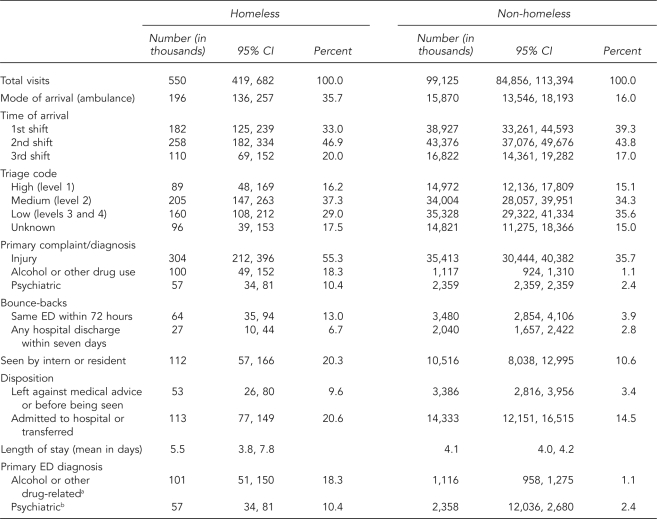

Table 2.

Annual emergency department visits, by clinical characteristics and homeless status: NHAMCS-ED, U.S., 2005–2006

aICD-9 codes 291-292, 303-305

bICD-9 codes 290, 293-302, 306-319

NHAMCS-ED = National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey—Emergency Department

CI = confidence interval

ED = emergency department

ICD-9 = International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision

Importantly, visits by homeless people were far more likely to be characterized by recent use of the ED or hospital admission. Specifically, homeless people were three times more likely to be classified as having undergone evaluation in the same ED within the preceding three days (13.0% homeless vs. 3.9% non-homeless), and more than twice as likely to involve a return (e.g., bounce-back) to the ED after a hospitalization within the previous week (6.7% homeless vs. 2.8% non-homeless).

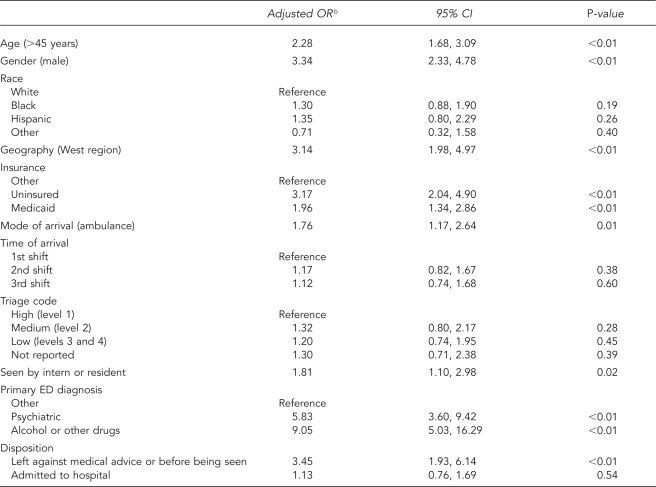

Table 3 presents the results of a multiple logistic regression analysis of the variables described in Tables 1 and 2, excluding disposition and length of stay for in-patients. Because of missing responses, variables related to recent prior use of EDs or the hospital were also excluded. Demographic variables independently associated with ED visits by homeless people included male gender, being uninsured, aged >45 years, and Western geographic region. Additionally, in this adjusted analysis, both Medicaid and uninsured status were associated with homelessness relative to “other” status (e.g., insured through Medicare or private insurance). Conversely, there was no independent association between race and homelessness among this sample of ED visits. Homelessness was independently associated with the following clinical variables: arrival to the ED by ambulance, evaluation by a physician-in-training, and leaving the ED before treatment was completed. Time of patient arrival and level of triage on presentation were factors not shown to be independently associated with ED visits by homeless individuals.

Table 3.

Characteristics associated with homelessness among a national cohort of 1.1 million ED visits in the U.S., NHAMCS-ED, 2005–2006a

aAnalysis of 1.1 million weighted ED visits during the years 2005–2006, for characteristics associated with homeless status as the dependent variable, among 234 million visits, with 1.1 million visits classified as “homeless.”

bAdjusted OR represents the association between each characteristic and the odds of the visit being classified as homeless, relative to it not being so classified, adjusting for all other characteristics shown in the table.

ED = emergency department

NHAMCS-ED = National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey—Emergency Department

OR = odds ratio

CI = confidence interval

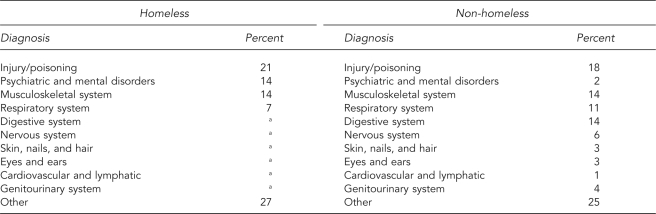

The primary diagnoses, as broken down by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes for ED visits by homeless and non-homeless individuals, are presented in Table 4. Both groups were most often diagnosed with an injury or poisoning. However, while homeless visitors were often diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder, non-homeless people were only rarely assigned this diagnosis.

Table 4.

Primary diagnoses for emergency department visits by homeless and non-homeless people in the U.S., NHAMCS-ED, 2005–2006

aSample size too small to calculate

NHAMCS-ED = National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey—Emergency Department

DISCUSSION

Homelessness affects major U.S. cities across the nation. To our knowledge, this study is the first to attempt to characterize ED visits made by homeless individuals in the U.S. from a national perspective.

We found that ED visits by homeless people represent a very small percentage (0.5%, weighted) of total ED visits across the U.S. However, on any given day, homeless people are estimated to represent one-quarter of a percent of the general population, given the U.S. Census Bureau projections for 2006.26 When analyzing chronic ED users, a San Francisco study found that homelessness was the characteristic most predictive of ED use.14 Homeless patients have previously been shown to comprise as much as 30% of an ED's yearly adult census.15 While the prior homeless ED studies relied on geographically local samples, this study underscores that the health service challenges attached to homelessness are national in scope.

Treating homeless patients is costly. A New York City study on public hospitals showed excess costs associated with in-patient hospital admissions for the homeless population.16 We did not demonstrate a significant difference between homeless and non-homeless people for length of stay of hospitalized patients, but the comparison was very imprecise, with the 95% CIs spanning four days. Homeless individuals are more likely to use ambulance services because they lack transport to a health-care facility.6,27,28 This study confirmed that association. It also identified an increased tendency toward ED use shortly after recent hospital care. This tendency leads to significant monetary costs and exacerbates an already overburdened emergency care network.

Factors that were associated with homeless individuals' visits to the ED included acute injuries and primary diagnoses related to psychiatric illness and substance abuse, both of which are long-recognized vulnerabilities of the homeless population. Prior studies have shown that homeless people live in fear of being subject to violence.3,29 The popular press has publicized some episodes of violence directed toward homeless individuals.30–32 The high prevalence and co-occurrence of psychiatric illness with substance abuse in the homeless population can make this population difficult to treat.5,33,34

These national ED data also show that homeless individuals are more likely than non-homeless individuals to be seen by physicians-in-training (residents and interns). The implications of this finding remain opaque, however, as all individuals seen by physicians-in-training must by law also be evaluated by attending physicians and, therefore, should be receiving the same baseline level of care.

Given increasing public concern regarding overcrowding of EDs, efforts to humanely avert demand associated with homelessness should be of policy interest. For clinicians working in EDs, comprehensive planning of discharges is required because of homeless people's comorbid psychiatric and substance abuse issues and their lack of consistent and safe shelter.35,36 More comprehensive discharge planning and specialized ED-based programs have been shown to decrease ED visits by the homeless.26,37,38 Policy makers charged with unburdening overloaded hospitals and EDs may wish to consider medically supervised recovery environments, termed “medical respite programs,” now operating in more than 35 sites across the country. Availability of such programs has been associated with reduced hospital readmission in two observational studies, and a third multisite study is presently underway.39,40 A nationally prominent housing intervention may reduce the burden of homelessness on public resources (including EDs). Specifically, “Housing First” approaches focus on providing housing without requiring abstinence or treatment for medical or mental problems.41 Several recent studies have demonstrated that this type of program can reduce costs and improve health outcomes.42–44

Limitations

The estimated number of homeless ED visits, although high, is likely to be an undercount because homeless people may not volunteer housing status and ED staff may fail to inquire about or record this information, as homeless status is not a required item in clinical charts. Furthermore, when homeless patients are seen in the ED, they may not be easily identifiable on chart review because the patient will often list a shelter, friend or family's house, or a fictitious address as their primary residence. Enumerating the homeless is difficult in all circumstances, but especially in the retrospective chart review used for NHAMCS-ED. However, while absolute counts are likely to be underestimates, the relationship between homeless status and other variables is less likely to be biased.

The number of visits to EDs by homeless individuals in the dataset was limited to only two years because the NHAMCS-ED survey first began recording homeless status in 2005. As a result, the unweighted sample size for visits by homeless individuals was only 449. Because of limited statistical power, we assessed only a few of many potential explanatory variables and aggregated categories for some variables (e.g., insurance status and ED diagnosis) based on a priori reasoning, previous literature, and category size.

CONCLUSIONS

Because data on homelessness are now being collected with the NHAMCS-ED annually, regular review of this resource will provide important information in trends of ED use. Although our findings could suggest that national ED usage by homeless people is less than that previously reported in single hospital or city-based ED studies, the prevalence of homeless visitors to the ED is still high. The high frequency of repeat ED visits identifies a systemic shortcoming and underscores the need for policy remedies for homelessness in the U.S.

REFERENCES

- 1.U.S. Conference of Mayors. Hunger and Homelessness Survey: a status report on hunger and homelessness in America's cities—a 25-city survey. 2008. Dec, [cited 2009 Aug 16]. Available from: URL: http://usmayors.org/pressreleases/documents/hungerhomelessnessreport_121208.pdf.

- 2.Khadduri J, Culhane DP, Buron L, Cortes A, Holin MJ, Poulin S. The second annual homeless assessment report to Congress. Washington: Department of Housing and Urban Development (US), Office of Community Planning and Development; March 2008; [cited 2008 Dec 18]. Also available from: URL: http://www.hudhre.info/documents/2ndHomelessAssessmentReport.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levy BD, O'Connell JJ. Health care for homeless persons. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2329–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp038222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hibbs JR, Benner L, Klugman L, Spencer R, Macchia I, Mellinger A, et al. Mortality in a cohort of homeless adults in Philadelphia. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:304–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199408043310506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fischer PJ, Breakey WR. The epidemiology of alcohol, drug, and mental disorders among homeless persons. Am Psychol. 1991;46:1115–28. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.46.11.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim MM, Swanson JW, Swartz MS, Bradford DW, Mustillo SA, Elbogen EB. Healthcare barriers among severely mentally ill homeless adults: evidence from the five-site health and risk study. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2007;34:363–75. doi: 10.1007/s10488-007-0115-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heslin KC, Robinson PL, Baker RS, Gelberg L. Community characteristics and violence against homeless women in Los Angeles County. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2007;18:203–18. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2007.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kushel MB, Vittinghoff E, Haas JS. Factors associated with the health care utilization of homeless persons. JAMA. 2001;285:200–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.2.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gelberg L, Gallagher TC, Andersen RM, Koegel P. Competing priorities as a barrier to medical care among homeless adults in Los Angeles. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:217–20. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.2.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han B, Wells BL. Inappropriate emergency department visits and use of the Health Care for the Homeless Program services by homeless adults in the northeastern United States. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2003;9:530–7. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200311000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Toole TP, Conde-Martel A, Gibbon JL, Hanusa BH, Freyder PJ, Fine MJ. Where do people go when they first become homeless? A survey of homeless adults in the USA. Health Soc Care Community. 2007;15:446–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2007.00703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kessell ER, Bhatia R, Bamberger JD, Kushel MB. Public health care utilization in a cohort of homeless adult applicants to a supportive housing program. J Urban Health. 2006;83:860–73. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9083-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kushel MB, Perry S, Bangsberg D, Clark R, Moss AR. Emergency department use among the homeless and marginally housed: results from a community-based study. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:778–84. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.5.778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mandelberg JH, Kuhn RE, Kohn MA. Epidemiologic analysis of an urban, public emergency department's frequent users. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:637–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb02037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D'Amore J, Hung O, Chiang W, Goldfrank L. The epidemiology of the homeless population and its impact on an urban emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8:1051–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2001.tb01114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salit SA, Kuhn EM, Hartz AJ, Vu JM, Mosso AL. Hospitalization costs associated with homelessness in New York City. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1734–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199806113382406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Padgett DK, Struening EL, Andrews H, Pittman J. Predictors of emergency room use by homeless adults in New York City: the influence of predisposing, enabling and need factors. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41:547–56. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00364-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruger JP, Richter CJ, Spitznagel EL, Lewis LM. Analysis of costs, length of stay, and utilization of emergency department services by frequent users: implications for health policy. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:1311–7. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nawar EW, Niska RW, Xu J. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2005 emergency department summary. Adv Data. 2007;386:1–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pitts SR, Niska RW, Xu J, Burt CW. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2006 emergency department summary. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2008;6:1–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sirken MG, Shimizu I, French DK, Brock DB. Manual on standards and procedures for reviewing statistical reports. Hyattsville (MD): National Center for Health Statistics; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Hospital Association. AHA hospital statistics 2008. Chicago: American Hospital Association; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Hospital Association. AHA hospital statistics 2007. Chicago: American Hospital Association; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Center for Health Statistics (US). Public-use data file documentation NHAMCSH, MD. 2008. [cited 2008 Dec 18]. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd.htm.

- 25.Census Bureau (US). Annual estimates of the population for the United States, regions, states, and for Puerto Rico: April 1, 2000, to July 1, 2006. [cited 2008 Dec 18]. Available from: URL: http://www.census.gov/popest/states/NST-ann-est2006.html.

- 26.StatCorp. Stata®: Version 10.0. College Station (TX): StataCorp.; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dunford JV, Castillo EM, Chan TC, Vilke GM, Jenson P, Lindsay SP. Impact of the San Diego Serial Inebriate Program on use of emergency medical resources. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;47:328–36. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pearson DA, Bruggman AR, Haukoos JS. Out-of-hospital and emergency department utilization by adult homeless patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50:646–52. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Daiski I. Perspectives of homeless people on their health and health needs priorities. J Adv Nurs. 2007;58:273–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.The homeless and hate crimes. Los Angeles Times. 2008 Oct 30;A22 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Green A. Attacks on the homeless rise, with youths mostly to blame. The New York Times. 2008 Feb 15;A12 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raghunathan A. Attacks on homeless rising. St. Petersburg Times. 2007 Feb 19;3B [Google Scholar]

- 33.Folsom DP, Hawthorne W, Lindamer L, Gilmer T, Bailey A, Golshan S, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for homelessness and utilization of mental health services among 10,340 patients with serious mental illness in a large public mental health system. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:370–6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.2.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McNiel DE, Binder RL. Psychiatric emergency service use and homelessness, mental disorder, and violence. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56:699–704. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.6.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Backer TE, Howard EA, Moran GE. The role of effective discharge planning in preventing homelessness. J Prim Prev. 2007;28:229–43. doi: 10.1007/s10935-007-0095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simmons WJ. Discharging the homeless. Hosp Health Netw. 2007;81:10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Okin RL, Boccellari A, Azocar F, Shumway M, O'Brien K, Gelb A, et al. The effects of clinical case management on hospital service use among ED frequent users. Am J Emerg Med. 2000;18:603–8. doi: 10.1053/ajem.2000.9292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pope D, Fernandes CM, Bouthillette F, Etherington J. Frequent users of the emergency department: a program to improve care and reduce visits. CMAJ. 2000;162:1017–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Buchanan D, Doblin B, Sai T, Garcia P. The effects of respite care for homeless patients: a cohort study. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1278–81. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.067850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kertesz SG, Posner MA, O'Connell JJ, Swain S, Mullins AN, Shwartz M, et al. Post-hospital medical respite care and hospital readmission of homeless persons. J Prev Interv Community. 2009;37:129–42. doi: 10.1080/10852350902735734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsemberis S, Gulcur L, Nakae M. Housing First, consumer choice and harm reduction for homeless individuals with a dual diagnosis. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:651–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.4.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Larimer ME, Malone DK, Garner MD, Atkins DC, Burlingham B, Lonczak HS, et al. Health care and public service use and costs before and after provision of housing for chronically homeless persons with severe alcohol problems. JAMA. 2009;301:1349–57. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sadowski LS, Kee RA, VanderWeele TJ, Buchanan D. Effect of a housing and case management program on emergency department visits and hospitalizations among chronically ill homeless adults: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2009;301:1771–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kertesz SG, Weiner SJ. Housing the chronically homeless: high hopes, complex realities. JAMA. 2009;301:1822–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]