SYNOPSIS

Objective

Streptococcus pneumoniae (S. pneumoniae) causes significant mortality throughout the United States and greater mortality among American Indian/Alaska Natives. Vaccination reduces S. pneumoniae illness. We describe the methods used to achieve the Healthy People 2010 coverage rate goals for adult pneumococcal vaccine among those at high risk for severe disease in this population.

Methods

We implemented a pneumococcal vaccination project to bolster coverage followed by an ongoing multidisciplinary program. We used community, home, inpatient, and outpatient vaccinations without financial barriers together with data improvement, staff and patient education, standing orders, and electronic and printed vaccination reminders. We reviewed local and national coverage rates and queried our electronic database to determine coverage rates.

Results

In 2007, pneumococcal vaccination coverage rates among people ≥65 years of age and among high-risk people aged 18–64 years were 96.0% and 61.2%, respectively, exceeding Healthy People 2010 goals. Government Performance and Results Act analyses reports revealed a 2.7-fold increase (36.0% to 98.0%) of coverage from 2000 to 2007 among people ≥65 years of age at Whiteriver Service Unit in Whiteriver, Arizona.

Conclusions

We achieved pneumococcal vaccination rates in targeted groups of an American Indian population that reached Healthy People 2010 goals and were higher than rates in other U.S. populations. Our program may be a useful model for other communities attempting to meet Healthy People 2010 goals.

Streptococcus pneumoniae (S. pneumoniae) results in more deaths than any other vaccine-preventable disease in the United States.1 Death rates for pneumonia and influenza in American Indians and Alaska Natives (AIANs) of all ages were 33% greater than the U.S. rate of 23.7 per 100,000 population during 1999–2001,2 and AIANs aged 65–74 years had 15% higher death rates from pneumonia and influenza from 1994 to 1996 than the U.S. population of the same age during 1995.3

Diabetes has a substantial impact on deaths associated with pneumonia and influenza,4 and AIAN adults have an age-specific prevalence of diabetes that is two to three times higher than that for U.S. adults.5 In 1992, White Mountain Apaches had the highest rate of invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) of any population studied,6 and the pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPV) is effective for most high-risk conditions of that population.7 Additionally, use of the PPV as a preventive measure to mitigate secondary bacterial pneumonia deaths following influenza infection has been suggested as a planning strategy for an influenza pandemic.8,9

The Healthy People 2010 goal for pneumococcal vaccination coverage is 90% among noninstitutionalized people aged ≥65 years, and 60% for high-risk adults aged 18–64 years.10 Two national 2007 surveys11,12 reported that 57.7% and 65.6% of U.S. adults aged ≥65 years, respectively, had ever received a pneumococcal vaccination; the latter survey reported 32.8% coverage of high-risk adults aged 18–64 years. According to a nationwide 2007 Indian Health Service (IHS) Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA) report,13 79% of AIANs aged ≥65 years had ever received a pneumococcal vaccination.

During 2001–2003, the IHS Whiteriver Service Unit (WRSU) carried out an IHS grant-funded vaccination project to increase PPV coverage among people aged ≥55 years and adults with diabetes. After increasing coverage among these groups through the grant project, a multidisciplinary vaccination program maintained and improved rates among the project population groups and other high-risk groups, achieving Healthy People 2010 goals for PPV receipt. In this analysis, we characterize the successful PPV project and program and report vaccination rates for AIANs ≥65 years of age and high-risk adults aged 18–64 years through 2007 in this American Indian (AI) community.

METHODS

Health facility and service population description

WRSU is a rural, 40-bed IHS hospital and outpatient facilities complex on the White Mountain Apache Tribe Fort Apache Indian Reservation in eastern Arizona, with a user population of >16,000 people. Health services are provided to AIANs through IHS at no charge to the individual. The hospital provides adult and pediatric inpatient care, a birthing center and obstetric services, ambulatory surgery, and multiple support services. Outpatient services include a hospital-based clinic; an emergency department and urgent care services; a satellite clinic; and dental, optometry, physical therapy, pharmacy, and other support services.

The primary care staff at WRSU includes 20 physicians and eight nurse practitioners or physician assistants, representing 25 full-time equivalent clinical providers. There are approximately 1,500 WRSU hospital admissions, 1,200 transfers to other facilities, and 162,000 medical staff provider and nursing visits at WRSU annually. More than 96% of ambulatory visits are from Apache, Navajo, or Hopi tribal members.

Pneumococcal Vaccination Grant Project and Maintenance Program

In 2001, WRSU was awarded an IHS grant to fund a pilot site project to improve GPRA measures. One measure was the GPRA indicator for pneumococcal vaccination among adults with diabetes and people aged 55 years and older. The intent of the project was to improve the quality of vaccination records and to increase the PPV coverage of people with diabetes and adults ≥55 years of age. The ≥55 age category was chosen because a study on the White Mountain Apache Tribe Fort Apache Indian Reservation revealed higher IPD rates than other populations6 and this age category could be vaccinated with the resources available for the project. Vaccinations, previously recorded on paper (“hard copy” records) with subsequent electronic data entry into the electronic database, were updated so that all pneumococcal vaccinations for people with diabetes and people ≥55 years of age had an accurate electronic vaccination record. Vaccinations were administered at residents' homes, nine reservation work sites, and an elderly nutrition site by project nurses and during inpatient and outpatient visits by WRSU staff.

Following the vaccination project, the WRSU PPV vaccination program has been similar year to year, subject to modifications based on previous years' experience and advancements in the WRSU electronic health record (EHR). Vaccinations took place within WRSU facilities but generally were no longer administered in the field or at people's homes, as community vaccinations were an outreach provision through the vaccine project but not part of the vaccination program. WRSU adopted an informal (unwritten) policy following the project to vaccinate all AIANs ≥50 years of age due to the high rates of IPD in the WRSU population, and all people with high-risk conditions for IPD in accordance with Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommendations.14 This policy was formally adopted and placed on written and electronic reminders in 2006.

The EHR features a reminder tab that displays health maintenance recommendations, including vaccinations. However, diabetes was the only high-risk condition other than age among electronic reminders, as reminders are developed and upgraded through database software nationally and field facilities may only designate age groups and reminders for those with diabetes but not other high-risk conditions. At WRSU, the age-group reminder was set at age 50 and reminders for people with diabetes remained active. Vaccination reminders were also present on a paper health summary in hard copy charts. After the vaccination project was initiated in 2001, all vaccinations were documented electronically, which automatically updated health summaries in both hard copy health records and the EHR so that patients' vaccination status was subsequently immediately available throughout the service unit. A diabetes department, in operation before the vaccination project, continued to vaccinate people with diabetes through nurse educator visits and diabetes case management.

Changes since 2000 include PPV administered in patient examination rooms and during nursing screening instead of exclusively in a separate treatment room; initiation of an injection room for the specific purpose of providing injections, including vaccinations, to people without a primary provider appointment; primary care team dialysis center visits, which resulted in vaccination status documentation and referral of those not yet vaccinated; and PPV refusal documentation in patients' medical records. EHR visit documentation began with outpatient clinics in 2005 and was later extended to inpatient care in 2007; exceptions included emergency, urgent, and obstetrics inpatient and labor evaluation care not yet transitioned to the EHR.

Standing orders, reminders on patients' health summaries within paper medical records, and electronic reminders in the EHR permitted nurses to identify people in targeted groups and to vaccinate them immediately. Unvaccinated patients in targeted groups seen by medical providers were counseled and vaccinated in all outpatient and inpatient settings. Hospitalized patients often received vaccination immediately prior to discharge. All health care, including PPV administration within WRSU, was provided to AIANs without charge.

Revaccination is recommended by ACIP to people ≥65 years of age who received vaccine at least five years previously and were aged <65 years at the time of vaccination, and for immunocompromised people if at least five years have elapsed since receipt of first dose.

Health staff and public information

Pneumococcal vaccine recommendations and information were provided to WRSU clinicians using verbal communications and e-mails that promoted education and vaccination, and policies were placed in policy notebooks and electronically on the WRSU server. Formal policy referenced ACIP recommendations for PPV indications.14 Selected WRSU nurses attended two-day annual statewide immunization workshops that addressed pneumococcal vaccination among other immunizations. A vaccine information statement15 was provided to all people interested in or receiving vaccination, and translation or further explanation was available upon request. Clinical staff also provided information during individual visits or telephone calls.

Data and definitions

All queries were performed using the Resource and Patient Management System (RPMS) database (Office of Information Technology, IHS, Albuquerque, New Mexico). RPMS is an IHS software package used to compile the patient registry and electronically record information from medical records following every patient encounter. Data are recorded into the database directly from EHR entries and through data entry following visits recorded on paper charts from clinics or services not yet using the EHR.

We evaluated GPRA reports to compare recent and historic local and national PPV coverage, and performed a separate database analysis for high-risk groups in 2007. GPRA analyses had been performed previously for quality improvement purposes, used throughout the IHS to assess progress in multiple areas of health-care provision including pneumococcal vaccination coverage, as mandated by federal law for facilities receiving federal funds. Annual GPRA reports include data collected through fiscal years ending on September 30. GPRA analyses are standardized throughout the IHS and use database queries for all indicators. National GPRA PPV analyses are only available for the risk group of adults ≥65 years of age using the GPRA active clinical population, and locally for people ≥65 years of age and people with diabetes using active clinical, active diabetic, and user population definitions. Pneumococcal vaccination indicator analysis uses three population definitions. For WRSU, these are:

The GPRA user population, defined as AIANs alive throughout the evaluation period residing in a community within the WRSU “catchment area” (which includes the 2,500-square-mile reservation and non-reservation communities up to 75 miles from the hospital) who had a WRSU visit during the three years prior to the end of the report period;

The GPRA active clinical population, defined as people who met the criteria for the GPRA user population and had two visits to medical clinics in the three years prior to the end of the report period; and

The GPRA active diabetic population, defined as people among the active clinical population who had diabetes diagnosis confirmed at least one year prior to the report period, and had at least two WRSU visits in the past year and two diabetes-related visits ever.

These population definitions are established at a national level and were used in this study to allow consistent comparisons. Within our user population, 14,549 people of all ages are listed as living on the Fort Apache reservation, compared with the 2000 U.S. Census figure of 12,429. The user population definition excludes AIANs in the service unit registry who list an address within the service unit catchment area but have not visited the service unit in three years, so that those who have moved away, died, or received services elsewhere without database recognition are not included in GPRA measures. There are 3,388 people in the registry of this designation who do not meet the user population definition. A total of 1,089 (32%) are 20–29 years of age, and six are more than 100 years of age (likely deceased but unrecognized as such in the registry).

We performed 2007 database query analysis of risk groups ending December 31, 2007, using the GPRA user population, as the user population is a standard population definition used throughout the IHS that facilitates comparison with other IHS facilities and captures a large proportion of the community population. Medical conditions were identified through database queries using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes for high-risk conditions diagnosed at least one year prior to the last day of the study period (December 31, 2007). We performed a separate query for people receiving immunosuppressive therapy, as this information could not be captured through an ICD-9 code query.

We considered an individual to have an indication for PPV if he or she was ≥18 years of age with an underlying condition as defined by ACIP14 addressed at least once in the previous five years, or ≥65 years of age. We defined alcoholism as a clinical diagnosis of alcoholism, a history of complications related to alcohol use, or one or more medical visits associated with alcohol use in the previous five years. We defined generalized malignancy as a malignant neoplasm spread beyond an in-situ lesion or a neoplasm treated with systemic chemotherapy or radiation. We reviewed purpose-of-visit narratives to verify staging status of neoplasms, and used manual and/or electronic reviews to verify diagnoses and conditions. We reviewed purpose-of-visit narratives and records of people with diagnoses listed fewer than three times during 2003–2007 to verify diagnosis.

Analysis

Because GPRA analyses for PPV coverage do not evaluate high-risk condition groups other than those ≥65 years of age or people with diabetes, we performed database queries for 2007 PPV coverage rates for all high-risk conditions among those aged 18–64 and ≥65 years. In this analysis, we used the GPRA user population because the user population may reflect the actual residential population more closely than the active clinical population. We performed database queries and electronic and manual chart reviews to determine number of refusals and to adjust for inaccurate or incomplete query information.

We used GPRA analysis reports, using GPRA active clinical population definitions and database queries, to compare WRSU 2007 PPV coverage rates with rates in previous years and to aggregate rates of the IHS, as GPRA reports are standardized and reported annually. National GPRA analyses of health indicators are performed using data from up to 191 health-care facilities and more than 1.2 million patients throughout the Indian health delivery network, although not all facilities participate in each health indicator analysis.

GPRA reports used the GPRA active diabetic population (locally) and the GPRA active clinical population ≥65 years of age (locally and nationally). Those with a documented PPV receipt any time prior to the end of the report period are identified as vaccinated against pneumococcus, and because GPRA tracks people who are offered vaccine, refusals are categorized as vaccinated. All others are considered unvaccinated. The 2007 non-GPRA database analysis counted refusals as unvaccinated.

RESULTS

Vaccination project and GPRA reports

During the vaccination project of 2001–2003, we reviewed health records of 2,295 AIAN residents of the service population and updated electronic database vaccination records from hard copy health records. Grant contractors worked 540 hours, administered 480 PPVs, and updated 508 additional vaccinations from paper to EHRs during the project.

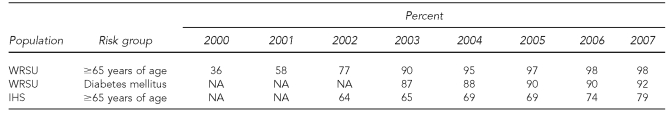

GPRA PPV coverage increased from 36% to 81% among people ≥65 years of age from October 2000 to March 2003 and to 90% by September 2003 (Table 1). People with diabetes had 67% coverage by March 2003 and 87% coverage by September 2003 (coverage prior to 2003 not available). During 2003–2007, PPV coverage increased from 90% to 98% and 87% to 92% among those ≥65 years of age and people with diabetes, respectively, by GPRA reports. During the same interval, national aggregate IHS PPV coverage rates for people ≥65 years of age increased from 65% to 79%. Aggregate IHS-wide coverage rates are not available prior to 2003, and numerator/denominator values and other high-risk group coverage rates are not available for any year. Among AIANs ≥65 years of age, only three refusals (<1%) were documented among people who did not receive PPV at some other time at WRSU.

Table 1.

Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine coverage at WRSU in people >65 years of age and adults with diabetes, and among all reporting IHS facilities in people >65 years of age, 2000–2007 (GPRA active clinical populations)a

aSources: GPRA FY04 performance report executive summary. Rockville (MD): Department of Health and Human Services (US); 2004. GPRA FY05 12-area summary report. Rockville (MD): Department of Health and Human Services, Indian Health Service (US); 2005. GPRA FY07 12-area summary report. Rockville (MD): Department of Health and Human Services, Indian Health Service (US); 2007.

WRSU = Whiteriver Service Unit

IHS = Indian Health Service

GPRA = Government Performance and Results Act

NA = not available

2007 WRSU user population high-risk group rates

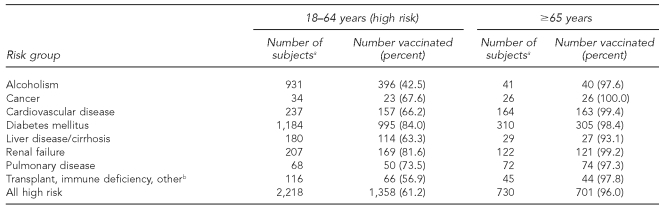

The WRSU PPV coverage rate was 96.0% among people ≥65 years of age and 61.2% among high-risk people aged 18–64 years in the GPRA user population by the end of 2007 (Table 2). Our analysis revealed PPV coverage was ≥93% for any high-risk subgroup among those ≥65 years of age and ranged between 42.5% and 84.0% among high-risk subgroups aged 18–64 years. Vaccination of high-risk subgroups among people 18–64 years of age with alcoholism and immune deficiency (e.g., transplant recipients, immune deficiency conditions, chronic immunosuppressive medications, and asplenia) fell below the Healthy People 2010 goal of 60% coverage (42.5% and 56.9%, respectively); all other high-risk condition subgroups reached PPV coverage rates ≥63.3%. 2007 PPV coverage rates differ between GPRA reports (Table 1) and database analyses (Table 2) among those ≥65 years of age and people with diabetes because of different population definitions (active clinical vs. user population, respectively), differing study period end dates (September 30 and December 31, respectively), and because GPRA analyses count refusals as vaccinated.

Table 2.

People ever receiving pneumococcal vaccine by risk group, Whiteriver Service Unit, Indian Health Service, 2007 (GPRA user population, registry database)

aSome subjects are included in more than one risk group.

bCategory includes people with transplants and immune deficiency disorders (e.g., human immunodeficiency virus, chronic immunosuppressive medications, and asplenia).

GPRA = Government Performance and Results Act

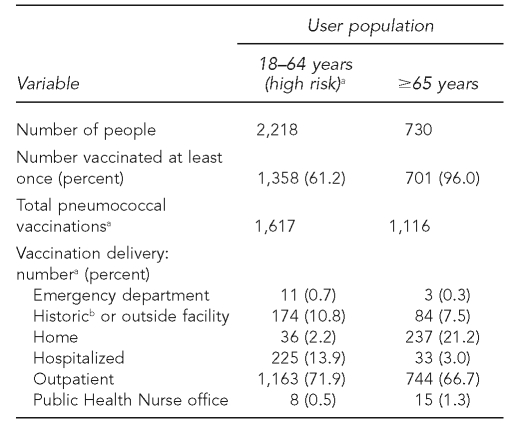

Our analysis revealed that 71.9% and 66.7% of people aged 18–64 years and ≥65 years of age, respectively, were vaccinated as outpatients (Table 3). A greater percentage of people ≥65 years of age compared with those aged 18–64 years were vaccinated at home (21.2% vs. 2.2%), and a greater percentage of people 18–64 years of age compared with those aged ≥65 years were vaccinated during hospitalization (13.9% vs. 3.0%). Historic vaccinations at undocumented locations and vaccinations received at outside facilities were more common among people 18–64 years of age than among those ≥65 years of age (10.8% vs. 7.5%). Few vaccinations in either group were given in the emergency department or at the Public Health Nursing office. Among 278 people who received PPV at least five years before age 65, 220 (79%) were revaccinated after age 65 as recommended by ACIP (data not shown).

Table 3.

Pneumococcal vaccination ever and delivery method in the user population by age group, Whiteriver Service Unit, Indian Health Service, 2007

aSome people were vaccinated more than once.

bHistoric includes records updated electronically from paper records without documented location and vaccinations reported historically by patients.

DISCUSSION

We achieved Healthy People 2010 goals for PPV coverage rates in targeted groups of an AI population that were higher than rates in other U.S. populations. We attribute these accomplishments to the vaccination project undertaken in 2001 and the multidisciplinary approach used in our vaccination program. Specifically, the vaccination program included staff and community education, standing orders, reminders for vaccination, multiple facility locations and opportunities to vaccinate, and vaccination of outpatient and hospitalized patients without financial barriers, following an initial vaccination project that provided community and home vaccinations with electronic vaccination data reconciliation in addition to ongoing vaccination program services.

Vaccination project and program

The IHS grant-supported vaccination project was a successful program, more than doubling PPV coverage rates among people ≥65 years of age. Because pneumococcal vaccination has been shown to reduce IPD in most risk groups of this population,7 and studies have shown that pneumococcal vaccination improves health and saves medical expenses,16,17 we believe the project had a significant impact in these areas. Grants to support similar projects may ultimately improve health and decrease health costs in other populations. Data reconciliation (updating paper records to electronic vaccination records) contributed significantly, allowing electronic queries to capture 508 vaccinations previously available only by paper records and establishing a continuous, accurate electronic vaccination record that is immediately accessible throughout WRSU.

A total of 480 PPVs were provided during the project, which bolstered coverage rates to the Healthy People 2010 goal of 90% for people ≥65 years of age in 2003. Thereafter, rates continued to improve through use of the maintenance vaccination program as indicated by the GPRA report values shown in Table 1. Although the vaccination project improved coverage rates by the greatest magnitude, the maintenance program was effective in improving coverage rates from 90% to 98% among those ≥65 years of age despite the challenge of vaccinating people targeted but not successfully vaccinated during the project. In addition, the maintenance program was successful in achieving coverage rate goals in risk groups not addressed by the vaccination project.

Standing orders and vaccination reminders

Use of standing orders and vaccination of hospitalized people are effective and recommended tools for vaccination.18,19 We found standing orders greatly facilitated vaccination in clinics. Patients vaccinated during nurse screening provided efficient patient flow and opportunities for clinicians to explore patient concerns regarding vaccination refusals. This may contribute to improved vaccination coverage because studies have found that the most important factor in vaccine acceptance is a recommendation by a health-care provider,18,20 and individuals occasionally accept vaccination on their provider's recommendation after initial refusal.

Reminders for vaccination available in both EHRs and paper charts enhanced and supported the use of standing orders and provided clinicians an efficient mechanism for vaccination updates. In one study, electronic reminders increased inpatient PPV ordering by more than 40-fold over those without electronic reminders.19

Vaccination rate comparisons

All high-risk subgroup coverage rates met Healthy People 2010 goals except for alcoholism and immune deficiency subgroups among people 18–64 years of age (42.5% and 56.9%, respectively). People with alcoholism may have lower vaccination rates because it is a risk group for which PPV does not significantly reduce IPD,7 and providers may see no benefit to their vaccination. Additionally, alcohol-associated visits take place more commonly in the emergency department than in continuity clinics, and different care priorities, time, and workload demands in the emergency department may result in fewer PPV administrations in that setting. Nonetheless, the emergency department can be an important place to provide vaccinations.21,22

People with immune deficiencies—human immunodeficiency virus, disorders of the immune system, transplant recipients, chronic immunosuppressive medications, or asplenia—were also in a high-risk subgroup of those aged 18–64 years who did not meet Healthy People 2010 coverage goals. Most people in this subgroup were taking immunosuppressive medications for arthritis, and arthritis is not listed as a high-risk condition in ACIP guidelines, potentially resulting in provider oversight. However, ACIP recommends that people taking chronic immunosuppressive medications receive PPV, and more support is mounting that PPV receipt is important among people with rheumatic diseases.23 Lack of proven efficacy, as stated in ACIP guidelines,14 should not preclude vaccination for these groups, as the high risk for disease and the potential benefits and safety of the vaccine justify vaccination.

Although 2007 PPV coverage rates reported for U.S. populations and U.S. AIANs11,24,25 are lower than those achieved at WRSU, different methods (phone reports vs. GPRA record queries) were used to determine these rates. U.S. AIAN PPV coverage rates among people ≥65 years of age are reported at 79% through GPRA reports, and U.S. population surveys reported rates of 57.5% and 65.6% in separate surveys.11,12 However, a study comparing AIAN and U.S. population PPV coverage rates from 2003 to 2005 reported that white populations had higher PPV coverage rates than AIANs (63.7% vs. 61.7%, respectively), using the same method (phone reports) for both populations.24 We feel our rates are accurate, as the database queries include all people in the WRSU registry and a comparison of WRSU registry and U.S. Census figures indicate that most, if not all, of residents on the White Mountain Apache Tribe reservation are in the WRSU registry. Our database indicates that a large majority—83% of those in the registry, and >100% of U.S. Census figures—of the population visits WRSU at least once every three years (a GPRA user population criterion), likely because of availability of a wide range of health services without charge and lack of other medical facilities nearby (30- to 60-mile distances for most local residents).

The WRSU vaccination project had a very significant impact on rates that were initially low, more than doubling coverage rates at WRSU. GPRA reports reveal a steady improvement of PPV rates from WRSU and IHS facilities since 2003, indicating continuous progress and program effectiveness. We do not have information on differences or similarities between the WRSU vaccination program and vaccination programs at other IHS facilities, and services available through the IHS vary widely among tribes.26

Despite advances in vaccination programs and PPV coverage rates nationally, most populations still fall short of Healthy People 2010 goals for PPV receipt, and WRSU is challenged with further improving PPV receipt among high-risk people aged 18–64 years, especially subgroups of people with alcoholism and immune deficiency. This may be best achieved by actively administering PPV at locations where these population groups are more likely available—at the health facility in the emergency department and at specialty clinics where care is provided for those with immune deficiencies, and by adding vaccination reminders to vaccinate all people within high-risk subgroups, not just those with diabetes and within high-risk age categories. Worksite vaccine clinics will also bring vaccination to working people, and could potentially be paired with influenza vaccinations.

Limitations

Findings in this report were subject to at least two limitations. First, an underestimate of vaccination rates will result if user population members receive vaccinations outside IHS that are not documented in IHS health records. Inaccurate vaccination information may exist in records of AIANs who moved from or into the catchment areas without updating their addresses or vaccination records, or whose deaths were unrecognized by IHS.

Secondly, vaccination rates may not be accurate if significant or disproportionate segments of the population are not included in the database. However, comparison of WRSU registry and U.S. Census figures indicate that most, if not all, of residents on the White Mountain Apache Tribe reservation are in the WRSU registry, as mentioned previously. People in the registry but without a visit in three years, and therefore not in the user population, tend to be young adults who may not be living in the community or are healthy and less likely to have high-risk conditions for pneumococcal disease.

Rates used to compare WRSU with aggregate IHS totals using the GPRA active clinical population included refusals among those vaccinated (as this indicator evaluates rates of people offered vaccine), which results in an overestimate of vaccination rates. We included refusals in GPRA reports to compare WRSU and aggregate IHS rates, because refusal numbers among the aggregate IHS totals are not available and could not be excluded. However, refusals had minimal impact on WRSU rates; only 0.4% of those ≥65 years of age with documented refusals of PPV were never vaccinated. We did not include refusals among people vaccinated in the WRSU user population coverage rates (Table 2).

CONCLUSIONS

Pneumonia prevention through pneumococcal vaccination has taken on increased importance as influenza pandemic threats loom. Challenges remain for reaching Healthy People 2010 PPV goals and other health measures among AIANs and other U.S. populations.27 Additional strategies may be needed for communities to achieve 90% PPV coverage and other Healthy People 2010 objectives. WRSU has met goals for PPV coverage through its vaccination program that included a very successful grant-funded vaccination project. Grants for similar health programs may likewise improve other community health initiatives and should be made available. Facilities and communities attempting to improve PPV coverage rates may be similarly successful through data improvement; staff and patient education; standing orders; vaccination reminders; and providing community, home, inpatient, and outpatient vaccinations without financial barriers to those they serve, especially if supported by grants. Our vaccination project and ongoing program may be a useful model for other facilities or communities attempting to reach PPV coverage rates and other Healthy People 2010 objectives.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Whiteriver Service Unit (WRSU) staff for their substantial contributions to this study and the WRSU vaccination program. The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Indian Health Service.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gardner P, Schaffner W. Immunization of adults. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1252–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304293281708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Department of Health and Human Services, Indian Health Service (US) Regional differences in Indian health, 2002–2003 edition. Washington: Government Printing Office; 2008. Mar, [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of Health and Human Services; Indian Health Service (US) Indian health focus—elders, 1998–1999. Rockville (MD): IHS; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valdez R, Narayan KM, Geiss LS, Engelgau MM. Impact of diabetes mellitus on mortality associated with pneumonia and influenza among non-Hispanic black and white U.S. adults. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1715–21. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.11.1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diabetes prevalence among American Indians and Alaska Natives and the overall population—United States, 1994-–2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52(30):702–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cortese MM, Wolff M, Almeido-Hill J, Reid R, Ketcham J, Santosham M. High incidence rates of invasive pneumococcal disease in the White Mountain Apache population. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152:2277–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bliss SJ, Larzalere-Hinton F, Lacapa R, Eagle KR, Frizzell F, Parkinson A, et al. Invasive pneumococcal disease among White Mountain Apache adults, 1991–2005. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:749–55. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.7.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta RK, George R, Nguyen-Van-Tam JS. Bacterial pneumonia and pandemic influenza planning. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:1187–92. doi: 10.3201/eid1408.070751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peltola VT, Murti KG, McCullers JA. Influenza virus neuraminidase contributes to secondary bacterial pneumonia. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:249–57. doi: 10.1086/430954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Healthy People 2010: understanding and improving health. 2nd ed. Washington: Department of Health and Human Services (US); 2000. [cited 2009 Dec 22]. Also available from: URL: http://www.healthypeople.gov/document/html/volume1/14immunization.htm#_Toc494510242. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heyman KM, Schiller JS, Barnes PM. Early release of selected estimates based on data from the 2007 National Health Interview Survey. Rockville (MD): National Center for Health Statistics (US); 2008. [cited 2008 Jun 18]. Also available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/earlyrelease200806.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Euler GL, Lu P, Singleton JA. Vaccination coverage among U.S. adults, National Immunization Survey—adult, 2007. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US); 2008. [ cited 2008 Mar 26]. Also available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/stats-surv/nis/downloads/nis-adult-summer-2007.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Indian Health Service (US) Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA) 12 area summary report, appendix A-1. Rockville (MD): Department of Health and Human Services (US); 2007. [ cited 2009 Dec 22]. Also available from: URL: http://www.ihs.gov/FacilitiesServices/AreaOffices/California/uploadedfiles/gpra/GPRA-2007_12AreaReport_Public.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prevention of pneumococcal disease: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Recomm Rep. 1997;46(RR-8):1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Vaccine information statement: pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine: what you need to know. Rockville (MD): Department of Health and Human Services (US); 2007. [ cited 2009 Dec 22]. Also available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/vis/downloads/vis-ppv.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sisk JE, Moskowitz AL, Whang W, Lin JD, Fedson DS, McBean AM, et al. Cost-effectiveness of vaccination against pneumococcal bacteremia among elderly people. JAMA. 1997;278:1333–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sisk JE, Whang W, Butler JC, Sneller VP, Whitney CG. Cost-effectiveness of vaccination against invasive pneumococcal disease among people 50 through 64 years of age: role of comorbid conditions and race. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:960–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-12-200306170-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adult immunization: knowledge attitudes and practices—DeKalb and Fulton Counties, Georgia, 1988. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1988;37(43):657–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dexter PR, Perkins S, Overhage JM, Maharry K, Kohler RB, McDonald CJ. A computerized reminder system to increase the use of preventive care for hospitalized patients. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:965–70. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa010181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fiebach NH, Viscoli CM. Patient acceptance of influenza vaccination. Am J Med. 1991;91:393–400. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(91)90157-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rimple D, Weiss SJ, Brett M, Ernst AA. An emergency department-based vaccination program: overcoming the barriers for adults at high risk for vaccine-preventable diseases. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:922–30. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rudis MI, Stone SC, Goad JA, Lee VW, Chitchyan A, Newton KI. Pneumococcal vaccination in the emergency department: an assessment of need. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;44:386–92. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elkayam O, Ablin J, Caspi D. Safety and efficacy of vaccination against streptococcus pneumonia in patients with rheumatic diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2007;6:312–4. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lindley MC, Groom AV, Wortley PM, Euler GL. Status of influenza and pneumococcal vaccination among older American Indians and Alaska Natives. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:932–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.119321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kilmer G, Roberts H, Hughes E, Li Y, Valluru B, Fan A, et al. Surveillance of certain health behaviors and conditions among states and selected local areas—Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), United States, 2006. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2008;57(7):1–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zuckerman S, Haley J, Roubideaux Y, Lillie-Blanton M. Health service access, use, and insurance coverage among American Indians/Alaska Natives and whites: what role does the Indian Health Service play? Am J Public Health. 2004;94:53–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Department of Health and Human Services (US) Healthy People 2010 midcourse review: executive summary. [cited 2007 Feb 21]. Available from: URL: http://www.healthypeople.gov/Data/midcourse/pdf/ExecutiveSummary.pdf.