In recent years, the Council on Education for Public Health (CEPH) in the United States has placed particular emphasis on practice-based learning in public health graduate programs. In its guidance to the schools of public health, CEPH states that “a planned, supervised, and evaluated practice experience is an essential component of a public health professional degree program.”1 Such practice-based experience (or “practicum”) can be beneficial to both the student and the community organization.2

Accordingly, the University of Texas School of Public Health (UTSPH) has made a practicum of three to nine credit hours mandatory for all students in the master of public health (MPH) program.3 Concrete plans for the practice-based learning experience are designed by the student in close consultation with a faculty sponsor and a community preceptor. Students engaged in a practicum are also required to complete an online course on principles of public health practice that is delivered using Blackboard™ Learning System, a learning management software.4 At the end of the practicum, students and community preceptors complete confidential evaluation forms. Each student also submits an abstract of his or her practicum experience to the Office of Public Health Practice at UTSPH. A compilation of all student abstracts is made available to students and faculty through an e-book for shared learning, and selected abstracts have also been published in the Texas Public Health Journal for wider dissemination.5

This article describes one student's experience during a practicum conducted in spring 2009 as part of the MPH (epidemiology) program at UTSPH. It was developed as an applied epidemiology project—part of a larger National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded community-based tobacco intervention trial in India called Project ACTIVITY, which stands for Advancing Cessation of Tobacco in Vulnerable Indian Tobacco-Consuming Youth. This trial is being implemented by UTSPH in collaboration with the nongovernmental organization (NGO) Health-Related Information Dissemination Amongst Youth (HRIDAY) in Delhi, India.6 In addition, the student was invited to participate in a Global Youth Meet on tobacco control (GYM 2009) and to present at the 14th World Conference on Tobacco or Health (WCTOH) in India during the same period.7,8 The UTSPH Office of Public Health Practice approved this semester-long practicum, which involved seven weeks of on-site fieldwork in India and eight weeks of distance-based research in Houston, Texas. The focus of this article is on the experiences from the seven weeks spent during fieldwork in India.

With recent calls for evidence-based public health policies, more practice-based research is needed to generate the required evidence.9 Schools of public health are in a unique position to conduct such practice-based research and simultaneously train future public health professionals. As many of the health challenges become global, public health students stand to benefit immensely from hands-on practical experiences in multicultural and/or international settings.

THE PRACTICUM

An international collaboration

The premise for designing this practicum was formed by a longstanding international public health collaboration between research teams in the U.S. and India. The primary institutional partners in this collaboration were the UTSPH's Michael and Susan Dell Center for Advancement of Healthy Living (Dell Center) and HRIDAY.10 This binational team consists of investigators who have implemented and disseminated intervention research on chronic disease prevention and youth health promotion for more than two decades, including research related to reducing tobacco use and obesity among youth. For example, this team was a successful applicant in the NIH Fogarty International Center's original International Tobacco and Health Research and Capacity Building Program with Project MYTRI—Mobilizing Youth for Tobacco Related Initiatives in India—a school-based tobacco intervention trial.11

Staff members from both teams have often traveled to each others' sites for meetings, consultations, fieldwork, and research presentations. This has facilitated cordial and productive working relationships between both teams at all staff levels. Likewise, human and -institutional capacity building of both teams has been an integral component of all their collaborative projects. HRIDAY staff have been supported for participation at international conferences and trained in principles of epidemiology and intervention design by UTSPH faculty and staff associated with these projects. The practicum discussed in this article was developed in this context, with an objective of strengthening technical capacity of the U.S. team to conduct large-scale intervention studies in challenging community-based settings in India.

Assignment I: Project ACTIVITY

The goal of this trial was to test the efficacy of a comprehensive, community-based tobacco control intervention among disadvantaged young people aged 10 to 19 years living in low-income communities in Delhi. In 2008, HRIDAY conducted a census of 14 selected slum communities, covering approximately 15,000 households. Following this census, communities were randomly assigned to intervention or control groups. Approximately 4,000 young people from sampled households in the intervention communities will receive a comprehensive two-year intervention composed of peer leader training and interactive activities to enhance their motivation to quit tobacco use and develop advocacy skills for tobacco control. During these two years, approximately 4,000 young people in the control communities will receive periodic free eye examinations. The main outcome measures will be prevalence rates and quit rates of tobacco use in intervention and control communities. To gather baseline indicators for the entire study sample for future evaluation of this trial, a survey of approximately 8,000 young people in intervention and control communities was planned in spring 2009.

Methods.

The main tasks related to Project ACTIVITY that were assigned to the UTSPH student included (1) development of study protocols and surveys for the baseline survey, (2) assisting in preparation of and participating in training activities for the project team and field-workers, (3) joining field-worker teams for data collection (youth interviews) in the communities, and (4) collating information and materials for development of intervention materials for the first year.

For a month, the student worked at the HRIDAY office as part of a diverse team of project officers, social scientists, field-workers, and community coordinators. During the first two weeks, the interview questionnaire and informed consent documents were drafted, finalized, and translated into Hindi, the local language in Delhi. Because individual residential units in slums are very closely located without formal house numbers or street names, a visual mapping of the communities was also conducted during this time (Photo 1). Once the questionnaires were finalized, we organized a two-day field-worker training workshop (Photo 2). The purpose of this workshop was to bring the entire team together, discuss the objectives of the project and baseline survey, assign field-workers to teams and communities, present and discuss the questionnaires, and participate in data collection exercises. We also discussed strategies to deal with potential challenges and bottlenecks that could arise during data collection. The workshop was highly interactive, and project staff collected several suggestions from the field-workers, some of whom had worked in community projects for nearly a decade.

Photo 1.

Fieldwork community, Delhi, India, January 2009

Photo 2.

Field-workers practice interviews using the questionnaire they developed for Project ACTIVITY, Delhi, India, January 2009

By the end of the second week, we had finalized the interview questionnaires, community-based sample lists, and fieldwork plans, and begun data collection. On a typical day, a team of field-workers would leave from the HRIDAY office with necessary materials in vehicles that were rented specifically for the project. With only an hour's break for lunch, the project staff spent the majority of the eight to 10 daily working hours conducting door-to-door visits of the sampled households to speak with parents and young people. As required by the ethics boards in India and the U.S., we obtained informed consent from both parents and children before sitting down at an agreeable spot near their house for an interview (Photos 3 and 4). Each interview lasted 30 to 45 minutes, at the end of which the young people were given a stationery case to thank them for their participation. When parents and/or young people were not present in the house or were otherwise occupied, we would schedule a suitable day and time for the interview and revisit the household at that time. Back in the office, field-workers and community coordinators cleaned and filed each interview questionnaire per the approved research protocol. In addition to data collection activities, we allotted some time each week for collecting and reviewing intervention materials used by other NGOs to provide health promotion programs to disadvantaged youth in Delhi. This gave us an overview of current youth health initiatives, which aided intervention development for Project ACTIVITY.

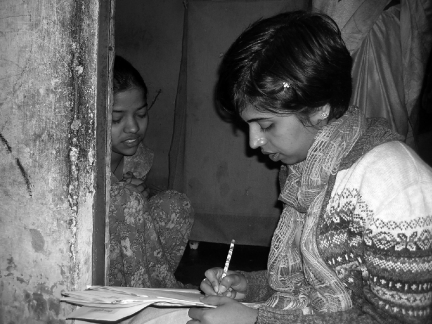

Photo 3.

Student author from University of Texas School of Public Health conducts an interview with a young person as part of Project ACTIVITY, Delhi, India, January 2009

Photo 4.

A field-worker conducts an interview with a young person outside his house in a slum community, Delhi, India, January 2009

Outcomes.

During the month the student spent at the HRIDAY office, data collection for the baseline survey was successfully initiated. Similarly, consensus was reached on the key intervention components for the first year. Throughout the month, the student actively participated in regular meetings of the project team in the Delhi office and communicated using e-mail and Skype™ with her faculty adviser in the U.S.12 She was able to get on-the-job training in field epidemiology and apply her theoretical knowledge of survey methods to all assigned tasks. Assisting the field-worker training and lending support to the community coordinators in management of field-worker teams helped her understand the importance of effective teamwork in large epidemiologic projects.

Challenges.

Data collection from young people in slum communities is a challenging endeavor, and research teams can encounter several inhibiting factors. During the baseline survey for Project ACTIVITY, special efforts were made to overcome factors such as parent refusal, interview scheduling problems, field-worker safety, and other logistic issues. Field-workers were provided with parent information sheets and trained in alleviating parental concerns about granting consent for their children's participation. Field-workers maintained detailed response logs and revisited households two to three times, sometimes after regular work hours or on weekends, to complete interviews. Community coordinators were responsible for the safety of their respective field-workers and were provided with first-aid kits, discretionary nutrition funds, and other support, as needed. Of course, some untoward incidents did occur; for example, a project officer in the field was bitten by a stray dog and offered appropriate medical treatment.

Next steps.

Back at UTSPH, the student continued to provide epidemiologic support to the ongoing data collection and intervention development in Delhi. Baseline data collection was completed in May 2009, with a response rate of greater than 70%. Having completed the MPH program, the student recently became a full-time research coordinator at the UTSPH Dell Center. As a new member of this binational research collaboration, she remains closely engaged with data management, analysis plans, and intervention plans for Project ACTIVITY. The excellent rapport built with project staff during fieldwork in India has proved to be a key asset for smooth coordination of all ongoing activities.

Assignment II: GYM 2009 on tobacco control

The second such global gathering ever, GYM 2009 was organized by HRIDAY in partnership with the Salaam Bombay Foundation in Mumbai as a logistic partner.7,8 GYM 2009 was organized as a preconference workshop before the 14th WCTOH. The event was attended by 134 youth delegates (aged 16 to 25 years) and their adult chaperones from 27 countries worldwide and seven Indian states. The focus of GYM 2009 was on two particularly timely issues in tobacco control—smoke-free environments and a ban on tobacco advertising and promotion. Over the course of two days, youth delegates were provided multiple opportunities to discuss and debate these issues. Following the workshop, youth delegates had the opportunity to attend various scientific sessions at the WCTOH and to participate in tobacco control advocacy.

Methods.

The main tasks related to GYM 2009 assigned to the UTSPH student included 1 reviewing curriculum for the youth workshop, 2 facilitating assigned youth group discussions on policy and skill-building during GYM 2009, and 3 assisting with youth advocacy activities during the WCTOH. Each day, the youth workshop began with a plenary session, where experts from institutions such as the World Health Organization (WHO) engaged participants in conversations about important movements in tobacco control, including the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC) and the MPOWER Report.13,14 Representatives from NGOs also participated in the plenary sessions to share their experiences in tobacco control advocacy. After the plenary sessions, delegates broke out into small groups specific to the six WHO world regions. Facilitators led participants through a curriculum on skill-building and advocacy, with a series of exercises to empower them with communication and leadership skills (Photo 5). During these exercises, the student facilitated discussions among delegates from Southeast Asia and guided them in writing mock individual and regional project plans by identifying goals, activities, and resources. Delegates chose various objectives for writing these plans, such as strengthening local enforcement of smoke-free policies and making educational institutions smoke-free. At the WCTOH, young people organized a march to express their support and solidarity for smoke-free environments and the WHO FCTC, and presented their regional action plans to international experts during the closing ceremony (Photo 6).

Photo 5.

Skill-building youth workshops at the Global Youth Meet, Mumbai, India, March 2009

Photo 6.

Smoke-free Mumbai march led by youth delegates, Mumbai, India, March 2009

Outcomes.

Findings from youth discussions and exercises indicated that delegates at GYM 2009 were aware of the tobacco control policies and challenges specific to their local communities and countries. Young people were eager to learn more about how they could promote tobacco control action in their local communities. Each delegate had an opportunity to establish linkages with other motivated youth activists to mobilize peers and motivate local governments for tobacco control. The regional action plans that the young people presented at the WCTOH were very well received by all delegates. The UTSPH student was able to perform her role as a facilitator for the youth discussions very well. Her oral and written communication skills, excellent technical understanding of evidence-based tobacco control interventions, and ability to effectively lead a team of more than 50 youth delegates were valuable during GYM 2009. At the same time, she had the opportunity to learn about youth-led tobacco control initiatives in various countries around the world.

Challenges.

Organizing and facilitating a workshop with young people from multiple nationalities and diverse educational backgrounds was challenging and required diligent attention from organizers and facilitators alike. Each day, young people were provided with “tobacco-free” time for cultural exchange where they had an opportunity to bond as a group. This relationship-building in turn facilitated vibrant interactions during plenary sessions and small-group discussions. Another factor that helped maintain youth interest was the opportunity to participate in the 14th WCTOH and obtain ideas for future academic and professional opportunities from leading international public health experts.

Next steps.

GYM 2009 youth delegates have stayed connected as part of the Youth for Health15 movement, through online platforms such as Facebook, and through the GYM website. The Dell Center is currently exploring funding streams to provide mini-grants to selected youth groups for implementing evidence-based interventions on tobacco control (as well as on healthy diets and physical activity). Similarly, we continue to seek platforms where young people can share their ideas and network with other public health groups. To illustrate, selected youth advocates will present their GYM 2009 experiences and tobacco control activities at a summer 2009 teen tobacco control summit in Houston.

DISCUSSION

Opportunities

Credit for the success of this practice-based learning experience goes to several facilitating factors. The expertise and experience of the public health scientists and practitioners at UTSPH and HRIDAY provided a solid basis for this challenging student experience. The Dell Center and HRIDAY have an established record of success in promoting youth health in the U.S. and other international settings. This experience ensured detailed planning and smooth implementation of the baseline survey as well as GYM 2009. Another critical factor was an excellent trusting partnership, which the U.S. research team has built over the years with HRIDAY in India. These teams have been conducting collaborative research for more than a decade now, which translated itself into a willingness to share information, embrace different perspectives, and resolve any problems that typically arise in partnership projects. Thus, HRIDAY was an excellent community site for this student practicum. HRIDAY staff members at all levels were willing to exchange ideas and share their experiences about community-based research implementation in India.

Additionally, the student had successfully completed core epidemiology courses prior to the practicum, which enabled her to provide excellent technical assistance in development of the interview questionnaire, field-worker training, and data collection efforts. The competencies that she built during the MPH program (such as applying epidemiologic concepts to public health practice, using behavioral and social sciences to plan public health interventions, designing evaluation strategies, and communicating with diverse audiences) were particularly valuable throughout the practicum. Furthermore, being well-versed in English and local Indian languages, the student did not face any language barriers in training local field-workers, collecting data, and visiting other local organizations.

Barriers

A common barrier that U.S. public health students can face in international field assignments is building trust with local organizations in a new country.16 This practicum highlights the importance of a preexisting collaboration with the chosen community organizations and also the willingness of local staff to host the student. Students may encounter cultural differences with the study subjects during fieldwork and also at the community organization hosting the students. Thus, for any student undertaking a practicum, the importance of quick learning skills, respectful communication, diplomatic skills, and an open-minded, transparent work ethic cannot be overemphasized.

Another concern is scarce institutional funding for practice-based experience.17 Supporting student field experiences through large grants such as Project ACTIVITY should be promoted as a norm in schools of public health. Students stand to gain much by participating in practical assignments, and will also bring lessons learned in the field back to the classroom. Funding agencies should be sensitized about the CEPH recommendation for all MPH students to have a direct practical experience before completion of their degree program.

Lessons learned

The Institute of Medicine has defined public health as “what we do collectively to assure conditions by which people can be healthy.”18 This article provides some valuable lessons on how students can become active participants in such collective action through an international practice-based learning experience. First, the student, faculty, and community organization should develop a detailed practicum plan and have a clear understanding of each person's responsibilities and the expected results. In this case, the practicum plan was especially useful to the community preceptor in assigning appropriate field activities to the student and evaluating the practicum experience at the end.

Second, a good theoretical foundation with courses related to epidemiologic methods and field surveys should be built before entering the field. For example, students selected for such a practicum should demonstrate sound knowledge of basic epidemiology, survey methods, basic biostatistics, and community-based health research. Completion of courses or seminars in global health and epidemiology of the specific disease being researched would be additional valuable assets.

Third, students should be encouraged to approach the community site as a real classroom where they may learn how to build productive partnerships with community organizations. Students can be encouraged to build these skills by volunteering with local health departments, for example, through initiatives such as the Student Epidemic Intelligence Society at UTSPH.19

Finally, students should try to familiarize themselves with the cultural context of the communities where the fieldwork will be conducted to ensure productive participation. In this practicum, the faculty adviser provided ample opportunities to the student for interacting with the organization in Delhi via telephone and e-mail, before she was sent for the field assignment. Thus, the student had a fair idea about the work culture and community setting of the organization where she was based during the practicum.

CONCLUSION

Practice-based health research projects are essential to well-rounded public health training. This practicum enabled one student to develop epidemiologic practice-oriented skills, apply theoretical knowledge of community-based research to practice, and understand the complex context in which research projects in developing countries operate. With increasingly global public health challenges, applied research skills and international experience will be valuable assets for future public health professionals. Participation in bi- or multinational projects can provide unique opportunities to students for developing these skills and greatly improve the quality of their training.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the project officers, community coordinators, and field-workers at the Health Related Information Dissemination Amongst Youth (HRIDAY) office in Delhi, India. A special thanks to the communities in Delhi where the fieldwork was conducted and the youth delegates who actively participated in the Global Youth Meet.

REFERENCES

- 1.Council on Education for Public Health. Accreditation criteria for public health programs. [cited 2010 Jan 14]. Available from: URL: http://www.ceph.org/files/public/PHP-Criteria-2005.so5.pdf.

- 2.Love R. Access to healthy food in a low-income urban community: a service-learning experience. Public Health Rep. 2008;123:244–7. doi: 10.1177/003335490812300221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The University of Texas School of Public Health. Office of Public Health Practice. [cited 2010 Jan 14]. Available from: URL: http://www.sph.uth.tmc.edu/practica.

- 4.Blackboard Inc. Blackboard™ Learning System: Version 8.0. Washington: Blackboard Inc.; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.The University of Texas School of Public Health. Office of Public Health Practice: practicum abstract ebooks: student practicum abstracts in TPHA [Texas Public Health Association] Journal 2009:61(2) [cited 2010 Jan 14]. Available from: URL: http://www.sph.uth.tmc.edu/practica/default.aspx?id=5432.

- 6.HRIDAY-SHAN. Health related information dissemination amongst youth–student health action network. [cited 2010 Jan 14]. Available from: URL: http://www.hriday-shan.org.

- 7.HRIDAY-SHAN. Global Youth Meet on Tobacco Control: GYM 2009. [cited 2010 Jan 14]. Available from: URL: http://gym09.hriday-shan.org/tag/gym2009.

- 8.Salaam Bombay Foundation. 14th World Conference on Tobacco or Health; 2009 Mar 8–12; Mumbai, India. [cited 2010 Jan 14]. Available from: URL: http://www.14wctoh.org.

- 9.Green LW. Public health asks of systems science: to advance our evidence-based practice, can you help us get more practice-based evidence? Am J Public Health. 2006;96:406–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The University of Texas School of Public Health. Michael and Susan Dell Center for Advancement of Healthy Living. [cited 2010 Jan 14]. Available from: URL: http://www.sph.uth.tmc.edu/-DellHealthyLiving/default.aspx.

- 11.Perry CL, Stigler MH, Arora M, Reddy KS. Preventing tobacco use among young people in India: Project MYTRI. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:899–906. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.145433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Skype Ltd. Skype™: Version 4.0. Luxembourg: Skype Ltd.; 2008.

- 13.World Health Organization. WHO framework convention on tobacco control. [cited 2010 Jan 14]. Available from: URL: http://www.who.int/fctc/en/index.html.

- 14.World Health Organization. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2008—the MPOWER package. [cited 2010 Jan 14]. Available from: URL: http://www.who.int/tobacco/mpower/2008/en/index.html.

- 15.HRIDAY-SHAN. Youth for Health. [cited 2010 Jan 14]. Available from: URL: http://y4h.hriday-shan.org/index.php.

- 16.Zuniga Carrillo G, Donnelly KC, Cortes DE, Olivares E, Gonzalez H, Cizmas LH. Border Health 2012: binational collaboration to develop an outreach environmental educational program. Public Health Rep. 2009;124:466–71. doi: 10.1177/003335490912400319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Butler J, Quill B, Potter MA. On academics: perspectives on the future of academic public health practice. Public Health Rep. 2008;123:102–5. doi: 10.1177/003335490812300117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Institute of Medicine. The future of public health. Washington: National Academy Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 19.The University of Texas School of Public Health. Student epidemic intelligence society. [cited 2010 Jan 14]. Available from: URL: http://www.sph.uth.tmc.edu/seis/default.aspx.