Summary

Although Tintinnopsis cylindrica Daday, 1887 is apparently widely distributed in the plankton of marine and brackish coastal waters, its ciliary pattern remained unknown. Without detailed knowledge of the cell morphology, however, the proposed synonymies cannot be proved. Hence, the cell and lorica features of T. cylindrica are redescribed from live and protargol-impregnated specimens collected in mixo-polyhaline basins at the German North Sea coast. An improved species diagnosis and a comprehensive unified terminology are provided. The somatic ciliary pattern of T. cylindrica is complex, comprising a ventral, dorsal, and posterior kinety as well as a right, left, and lateral ciliary field. Accordingly, the species differs from its congener T. cylindrata that has merely a right and left ciliary field and ventral organelles. On the other hand, the genera Codonella, Codonellopsis, Cymatocylis, Helicostomella, Leprotintinnus, and Stenosemella share this pattern. The oral primordium of T. cylindrica develops hypoapokinetally posterior to the lateral ciliary field as in Codonella cratera and Cymatocylis convallaria.

Keywords: biogeography, ciliary pattern, ecology, morphology, ontogenesis, taxonomy, Tintinnina

INTRODUCTION

Entz (1884, 1909b), Bütschli (1887-1889), Daday (1887), Brandt (1907), Schweyer (1909), and Hofker (1931) emphasized the significance of cytological features for a natural tintinnid taxonomy. Nevertheless, the majority of the ~ 1,200 tintinnid species was described in the following years, using merely lorica features (e.g., Kofoid and Campbell 1929, 1939). It was only in the eighties and nineties of the last century, that the investigation of the cell morphology experienced a renaissance by the redescription of 16 tintinnid species (Foissner and Wilbert 1979, Song and Wilbert 1989, Blatterer and Foissner 1990, Foissner and O’Donoghue 1990, Sniezek et al. 1991, Snyder and Brownlee 1991, Choi et al. 1992, Song 1993, Wasik and Mikołajczyk 1994, Petz et al. 1995). The number of reinvestigated species is, however, still too low for a revision of the classification and a comparison with the gene trees (Snoeyenbos-West et al. 2002, Strüder-Kypke and Lynn 2003). Hence, a further tintinnid species, viz., Tintinnopsis cylindrica, is redescribed in the present paper, including both, features of the lorica and the cell.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Collection

The samples were collected between 1991 and 1993 in the basins of two polders, viz., the Beltringharder Koog and the Speicherkoog Dithmarschen, at the North Sea coast of Schleswig-Holstein, northern Germany. These shallow (up to 15 m deep) basins contain brackish water of changing salinities as they are temporarily connected with the Wadden Sea by sluice gates and have freshwater inflow by rainwater, ground water, and streams. Likewise, they are characterized by reduced tidal currents, high turbidity, and eutrophication due to nutrient loads drained from agricultural areas. The abiotic factors that prevailed during the investigation period were described in detail by Agatha et al. (1994) and Riedel-Lorjé et al. (1998). Samples were taken monthly by bucket from December to February, fortnightly in March and November, and weekly during all other months at the bank of the basins. One subsample was immediately preserved with 1% Lugol’s iodine solution and analyzed latest six month after sampling for abundances (Agatha et al. 1994), while an unpreserved subsample was used for taxonomical investigations.

Taxonomic studies

All observations are from field material as culture trials failed, using a temperature of ~ 12°C, a 12 h light to 12 h dark cycle with an irradiance of ~ 15 μE m−2 s−1, and a mixture of flagellates from the sampling sites as prey. Cell movement was studied in a Petri dish (~ 6 cm across; water depth ~ 2.5 cm) under a dissecting microscope at ~ 20°C. Cell morphology was investigated under a compound microscope equipped with a high-power oil immersion objective as well as bright-field and interference contrast optics. Protargol impregnation followed the protocol of Song and Wilbert (1995). For scanning electron microscopy, cells were fixed for 30 min in a modified Parducz’ solution made of 6 parts of 2% OsO4 (w/v) in sea water and one part of saturated aqueous HgCl2 (Valbonesi and Luporini 1990); further steps followed Foissner (1991).

Counts and measurements on protargol-impregnated cells were performed at ×1,000; in vivo measurements were made at ×40-1,200.

The kinetal density index is the ratio of kinety number to cell circumference posterior to the membranellar zone [kineties/μm] in protargol-impregnated cells (Snyder and Brownlee 1991). Usually, it was impossible to count all somatic kineties in a specimen as the curved and densely spaced ciliary rows could not be discerned in the laterally orientated fields; hence, the kinetal index was not calculated.

Illustrations

Drawings of live specimens summarize information and are based on mean measurements, while those of protargol-impregnated specimens were made with a camera lucida. The kinetal map depicts the morphostatic ciliary pattern of a protargol-impregnated specimen in two dimensions (Foissner and Wilbert 1979, Choi et al. 1992), that is, the cortex is drawn as cut longitudinally along the dorsal kinety; it is also based on mean measurements. Horizontal bars symbolize the collar membranelles, diagonal bars those membranelles that are partially or entirely in the buccal cavity, namely, the elongated collar membranelles and the buccal membranelles. The ratio of cell circumference to length of kineties is 1:1. Kinetids are equidistantly arranged in the ciliary rows and the kinety curvature is neglected, except for the ventral and last kinety whose course might be of taxonomic significance. The somatic cilia are symbolized by oblique lines, differences in their length are not considered.

Neotype material

A slide with protargol-impregnated neotype specimens is deposited with the relevant cells marked in the Biology Centre of the Museum of Upper Austria (LI) in A-4040 Linz (Austria). The reasons for and the problems with neotypification are discussed by Foissner (2002), Foissner et al. (2002), and Corliss (2003).

RESULTS

Terminology

Since more than thirty years, the orders Halteriida and Oligotrichida have been separated from the order Choreotrichida by the shape of the adoral zone of membranelles (C-shaped vs. ring-shaped; Fauré-Fremiet 1970). However, Kim et al. (2005) discovered a new member of the family Strombidinopsidae (order Choreotrichida) with a slightly open membranellar zone, representing a transitional stage. Hence, a different terminology for the large and small membranelles/polykinetids in the Halteriida and Oligotrichida (anterior and ventral membranelles) on the one hand and the Choreotrichida (external and internal membranelles) on the other hand seems not any longer justified. Accordingly, a unifying and neutral terminology concerning the oral ciliature is introduced here. Additionally, the confusing terminology of the somatic ciliary components and some further features in the suborder Tintinnina is unscrambled here.

Adoral zone of membranelles

The adoral zone of membranelles is an orderly arrangement of membranelles around the peristomial field, terminating in the buccal cavity. The term was probably introduced by Bütschli (1887-1889) and is favoured, as the younger term “oral polykinetids” (Sniezek et al. 1991, Snyder and Brownlee 1991, Choi et al. 1992, Wasik and Mikołajczyk 1994) is restricted to the basal bodies of the membranelles and their associated fibres; both are only recognizable after silver impregnation. Furthermore, the expression “adoral zone of membranelles” is also used in the related class Hypotrichea (hypotrichs and stichotrichs).

Collar membranelles

The collar membranelles form a closed zone on the peristomial rim and constitute the anterior portion of the oral primordium in early dividers. They have larger polykinetids and longer cilia than the buccal membranelles. Some collar membranelles are elongated into the eccentric buccal cavity (praeorale Membranellen, Foissner and Wilbert 1979; Buccalmembranellen, Blatterer and Foissner 1990; somatic adoral membranelles, Foissner and O’Donoghue 1990). Although there are several other names for these membranelles (adorale Pectinellen, Entz 1909b; Membranulae, Entz 1929; Peristomal-Pektinellen, Entz 1937; adoral membranelles, Foissner and Wilbert 1979, Foissner and O’Donoghue 1990, Petz and Foissner 1993; external membranelles, Petz et al. 1995), the term “collar membranelles” is chosen, as it clearly explains the position of the membranelles and can also be used for the large membranelles in the Halteriida and Oligotrichida.

Buccal membranelles

The buccal membranelles are entirely situated in the buccal cavity and constitute the posterior portion of the oral primordium in early dividers. Note that some authors do not differentiate between elongated collar membranelles and buccal membranelles, but lump them to infundibular membranelles/polykinetids (e.g., Wasik and Mikołajczyk 1994). The term “buccal membranelles” is preferred instead of “internal membranelles” (Petz et al. 1995), as it clearly describes the position of the membranelles in the buccal cavity and is also applicable for the small membranelles in the Halteriida and Oligotrichida.

Endoral membrane

The endoral membrane extends across the peristomial field into the buccal cavity. It is usually named paroral membrane; however, due to its monostichomonad structure and probable homology to the endoral membrane of the stichotrichs, halteriids, oligotrichids, and most hypotrichs, this undulating membrane should likewise be called endoral membrane (Agatha 2004a, b).

Numbering of somatic kineties

The numbering commences with the ventral kinety or, when this ciliary row is absent, with the leftmost kinety of the right ciliary field and continues in clockwise direction when the cell is viewed from anterior (Chatton et al. 1931). Despite the fact that this numbering opposes that in the closely related suborder Strobilidiina (order Choreotrichida; Deroux 1974), it is maintained here to avoid confusion.

Ventral kinety

The ventral kinety is on the left side of the right ciliary field and on the right side of the oral primordium. It is the longest entirely monokinetidal ciliary row on the ventral side (Figs 1b, f). Although older expressions existed (frange bordante, frange ondulante, Fauré-Fremiet 1924; ciliary membrane, Campbell 1926, Kofoid and Campbell 1939, Tappan and Loeblich 1968), the term “ventral kinety” was introduced by Snyder and Brownlee (1991) to indicate the position of the ciliary row.

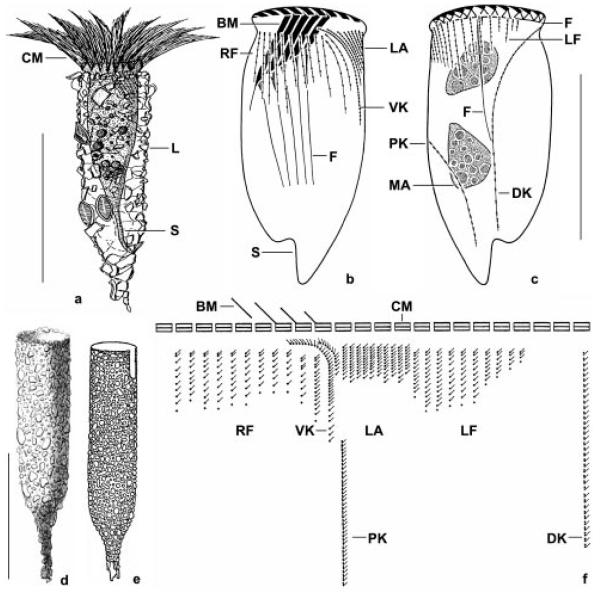

Figs 1a-f.

Tintinnopsis cylindrica (a-d, f) and a supposed synonym (e) from life (a, e), after protargol impregnation (b, c, f), and preserved with mercuric chloride (d). a - a representative specimen from the neotype population; b, c - ciliary pattern of ventral and dorsal side. Note the fibres that are associated with the oral and somatic ciliature; d - a lorica from the type population (from Daday 1887); e - Tintinnopsis kofoidi (from Hada 1932a); f - kinetal map of a morphostatic specimen. BM - buccal membranelle, CM - collar membranelles, DK - dorsal kinety, F - probably fibrillar structures, L - lorica, LA - lateral ciliary field, LF - left ciliary field, MA - macronuclear nodules, PK - posterior kinety, RF - right ciliary field, S - stalk, VK - ventral kinety. Scale bars: 100 μm (a, d, e); 50 μm (b, c).

Right ciliary field

The right ciliary field is on the right side of the ventral kinety, the ventral organelles, or a blank stripe. The name for this ciliary field on the right cell side was introduced by Snyder and Brownlee (1991).

Dorsal kinety

The dorsal kinety is separate from the right and left ciliary field between which it is situated dorsally. It is the longest kinety, usually extending from the membranellar zone to the base of the stalk. The term was introduced by Choi et al. (1992). Foissner and Wilbert (1979), Foissner and O’Donoghue (1990), and Petz et al. (1995) named it “ventral kinety”, although this ciliary row is on the cell side almost opposite to the eccentric buccal cavity.

Left ciliary field

The left ciliary field is on the left side of the dorsal kinety. Its ciliary rows are more closely spaced than those of the right ciliary field. The name for this ciliary field on the left cell side was introduced by Snyder and Brownlee (1991).

Lateral ciliary field

The lateral ciliary field is between the ventral kinety and the left ciliary field, with which it is occasionally lumped (Laval-Peuto 1994, Wasik and Mikołajczyk 1994). The term was introduced by Fauré-Fremiet (1924), and there are two similar expressions: Lateralfeld (Foissner and Wilbert 1979) and lateral field of kineties (Petz et al. 1995).

Posterior kinety

The posterior kinety is posterior to the lateral ciliary field. The term was introduced by Choi et al. (1992) and is favoured, as the names “Ventro-Lateralkinete” (Foissner and Wilbert 1979, Foissner and O’Donoghue 1990, Petz and Foissner 1993) and “dorsolateral kinety” (Petz et al. 1995) do not emphasize its unique position in the posterior cell portion.

Ventral organelles

The ventral organelles comprise a transverse (V1) and an oblique (V2) organelle, i.e., two short dikinetidal kineties posterior to the ventral collar membranelles. The term was introduced by Foissner and Wilbert (1979).

Capsules

Capsules are probably extrusive organelles that are attached to the cell membrane of cytoplasmic extensions, such as, accessory combs, striae, and tentaculoids. They are subspherical, 200-600 nm in size, and often form clusters; three morphotypes are known (Laval-Peuto and Barria de Cao 1987). Laval (1971 cited in Laval 1972) introduced the term “capsules torquées”, but in the English literature only “capsules” is used (Hedin 1975, Gold 1979, Laval-Peuto et al. 1979, Capriulo et al. 1986, Wasik and Mikołajczyk 1992); the older expressions “Bacterioidkörperchen” (Entz 1909b) and “trichocysts” (Campbell 1926) are less specific and are thus rejected.

Accessory combs

Accessory combs are conspicuous intermembranellar ridges. The term was introduced by Campbell (1926); the alternative names “Begleitkämme” (Entz 1909b) and “crêtes adorales” (Laval-Peuto 1994) were rarely used in the literature.

Striaes

Striae are beaded, longitudinal cytoplasmic strands that are enclosed together with an collar membranelle by the perilemma (Laval 1972, Laval-Peuto 1994). The term was introduced by Entz (1929) and more often used than the expressions “lames de revêtement” (Laval-Peuto et al. 1979) and “Deckplättchen” (Entz 1909b).

Tentaculoids

Tentaculoids are small, finger-like, and possibly contractile cytoplasmic extensions between the collar membranelles (Corliss 1979, Laval-Peuto and Brownlee 1986). The term was introduced by Haeckel (1873).

Lorica

A lorica is a house, fitting the cell loosely, with an anterior (oral) and occasionally posterior (aboral) opening. It is carried about by free-swimming species or fixed to the substratum by sessile ones (Corliss 1979). A lorica should not be confused with the distended and often reticulate posterior cell surface of the related Oligotrichida.

Protolorica

A protolorica is built by the proter just after cell division (Laval-Peuto and Brownlee 1986).

Paralorica

A paralorica is a replacement lorica formed by a morphostatic cell (Laval-Peuto and Brownlee 1986).

Epilorica

An epilorica is a spiralled or annulated portion frequently added to the anterior end of a protoor paralorica (Laval-Peuto and Brownlee 1986).

Tintinnopsis cylindrica Daday, 1887 (Figs 1-3, Table 1)

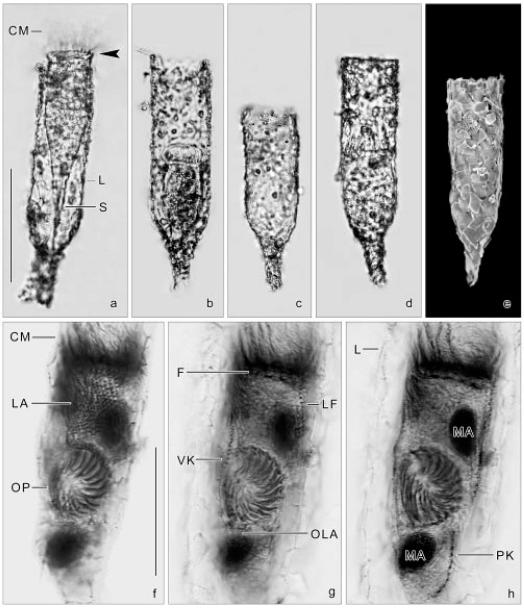

Figs 3a-h.

Tintinnopsis cylindrica from life (a-d), in the scanning electron microscope (e), and after protargol impregnation (f-h). a-d - lateral views showing lorica variability, concerning the degree of incrustrated particles and length of the cylindroidal portion. Accessory combs (arrowhead; a) are rarely recognizable; e - the lorica wall has many silt particles and fragments of diatom frustules incrustrated; f-h - same middle divider at three focal planes. The new oral apparatus develops in a subsurface pouch posterior to the proter’s lateral ciliary field. CM - collar membranelles, F - probably fibrillar structures, L - lorica, LA - proter’s lateral ciliary field, LF - left ciliary field, MA - macronuclear nodules, OLA - opisthe’s lateral ciliary field, OP - oral primordium, PK - posterior kinety, S - stalk, VK - ventral kinety. Scale bars: 100 μm (a-e); 50 μm (f-h).

Table 1.

Tintinnopsis cylindrica morphometric data. Measurements in μm. CV - coefficient of variation in %, M - median, Max - maximum, Min - minimum, n - number of individuals investigated, SD - standard deviation, SE - standard error of arithmetic mean, - arithmetic mean.

| Characteristicsa | M | SD | SE | CV | Min | Max | n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lorica, total lengthb | 151.3 | 148.0 | 25.1 | 5.2 | 16.6 | 75.0 | 220.0 | 23 |

| Lorica, oral diameterb | 48.4 | 49.0 | 5.2 | 1.1 | 10.8 | 34.0 | 56.0 | 23 |

| Lorica length:oral diameter, ratiob | 3.2 | 3.0 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 19.4 | 1.6 | 5.2 | 23 |

| Lorica, length of cylindroidal portionb | 98.1 | 95.0 | 18.1 | 4.7 | 18.4 | 69.0 | 144.0 | 15 |

| Lorica, length of tapered portionb | 26.2 | 28.0 | 8.5 | 2.2 | 32.6 | 6.0 | 38.0 | 15 |

| Lorica, process lengthb | 22.1 | 20.0 | 9.7 | 2.4 | 43.9 | 0.0 | 38.0 | 15 |

| Lorica, process diameterb | 10.1 | 10.0 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 7.3 | 8.0 | 11.0 | 15 |

| Cell, length | 71.0 | 68.5 | 12.8 | 2.6 | 18.0 | 52.0 | 89.0 | 24 |

| Cell, width | 31.7 | 32.5 | 6.2 | 1.3 | 19.5 | 22.0 | 48.0 | 24 |

| Macronuclei, length | 15.6 | 16.0 | 4.5 | 1.0 | 29.2 | 9.0 | 23.0 | 19 |

| Macronuclei, width | 8.1 | 8.0 | 2.3 | 0.5 | 28.2 | 3.0 | 12.0 | 19 |

| Macronuclei, number | 2.0 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 19 |

| Micronuclei, diameter | 2.0 | 2.0 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 34.0 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 14 |

| Micronuclei, number | 2.0 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 14 |

| Ventral kinety, lengthc | 22.1 | 23.0 | 3.7 | 1.4 | 16.8 | 17.0 | 28.0 | 7 |

| Ventral kinety, number of kinetids | 35.8 | 33.0 | 12.3 | 5.5 | 34.4 | 25.0 | 55.0 | 5 |

| Dorsal kinety, lengthc | 46.8 | 43.5 | 9.4 | 4.7 | 20.2 | 40.0 | 60.0 | 4 |

| Dorsal kinety, number of kinetids | 36.1 | 36.0 | 9.6 | 3.6 | 26.5 | 25.0 | 55.0 | 7 |

| Posterior kinety, lengthc | 33.4 | 31.0 | 14.6 | 6.5 | 43.7 | 19.0 | 50.0 | 5 |

| Posterior kinety, number of kinetids | 26.1 | 21.0 | 10.7 | 3.6 | 41.0 | 15.0 | 45.0 | 9 |

| Left ciliary field, number of kineties | 10.4 | 11.0 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 14.5 | 8.0 | 12.0 | 8 |

| 1. kinety in left field, length | 2.4 | 2.0 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 31.3 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 8 |

| 1. kinety in left field, number of kinetids | 2.9 | 3.0 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 22.3 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 8 |

| 2. kinety in left field, length | 3.9 | 4.0 | 1.6 | 0.6 | 42.4 | 2.0 | 7.0 | 8 |

| 2. kinety in left field, number of kinetids | 3.9 | 3.5 | 2.0 | 0.7 | 50.6 | 2.0 | 8.0 | 8 |

| 3. kinety in left field, length | 5.8 | 5.0 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 20.3 | 5.0 | 8.0 | 8 |

| 3. kinety in left field, number of kinetids | 5.5 | 5.0 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 19.4 | 4.0 | 7.0 | 8 |

| 4. kinety in left field, length | 8.3 | 8.5 | 2.9 | 1.0 | 35.3 | 3.0 | 12.0 | 8 |

| 4. kinety in left field, number of kinetids | 7.9 | 8.0 | 2.6 | 0.9 | 33.6 | 3.0 | 11.0 | 8 |

| 5. kinety in left field, length | 9.8 | 10.0 | 2.5 | 0.9 | 26.1 | 6.0 | 15.0 | 8 |

| 5. kinety in left field, number of kinetids | 9.8 | 9.5 | 2.0 | 0.7 | 20.3 | 7.0 | 13.0 | 8 |

| 6. kinety in left field, length | 10.6 | 9.5 | 2.8 | 1.0 | 26.6 | 8.0 | 16.0 | 8 |

| 6. kinety in left field, number of kinetids | 10.1 | 10.0 | 1.6 | 0.6 | 16.2 | 8.0 | 13.0 | 8 |

| 7. kinety in left field, length | 11.1 | 9.0 | 4.2 | 1.5 | 37.7 | 8.0 | 20.0 | 8 |

| 7. kinety in left field, number of kinetids | 10.1 | 9.5 | 2.7 | 1.0 | 27.1 | 7.0 | 16.0 | 8 |

| 8. kinety in left field, length | 11.5 | 9.5 | 4.8 | 1.7 | 41.3 | 8.0 | 19.0 | 8 |

| 8. kinety in left field, number of kinetids | 11.5 | 10.5 | 4.0 | 1.4 | 35.1 | 7.0 | 18.0 | 8 |

| 9. kinety in left field, length | 11.7 | 11.0 | 4.5 | 1.7 | 38.7 | 6.0 | 18.0 | 7 |

| 9. kinety in left field, number of kinetids | 12.0 | 12.0 | 4.4 | 1.7 | 36.6 | 7.0 | 18.0 | 7 |

| 10. kinety in left field, length | 11.4 | 8.0 | 5.6 | 2.5 | 49.5 | 6.0 | 18.0 | 5 |

| 10. kinety in left field, number of kinetids | 11.0 | 10.0 | 3.4 | 1.5 | 30.8 | 7.0 | 15.0 | 5 |

| 11. kinety in left field, length | 10.6 | 10.0 | 4.8 | 2.2 | 45.5 | 5.0 | 16.0 | 5 |

| 11. kinety in left field, number of kinetids | 10.6 | 9.0 | 3.6 | 1.6 | 34.4 | 7.0 | 15.0 | 5 |

| 12. kinety in left field, length | 11.5 | - | - | - | - | 9.0 | 14.0 | 2 |

| 12. kinety in left field, number of kinetids | 11.0 | - | - | - | - | 8.0 | 14.0 | 2 |

| Lateral ciliary field, number of kineties | 11.1 | 10.0 | 2.9 | 1.1 | 25.6 | 8.0 | 16.0 | 7 |

| Right ciliary field, number of kineties | 10.6 | 11.0 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 12.0 | 9.0 | 12.0 | 7 |

| 1. kinety of right field, length | 16.3 | 15.0 | 3.9 | 1.6 | 24.1 | 13.0 | 23.0 | 6 |

| 1. kinety of right field, number of kinetids | 14.3 | 14.0 | 4.1 | 1.4 | 28.5 | 9.0 | 19.0 | 8 |

| 2. kinety of right field, length | 11.0 | 10.5 | 2.8 | 1.1 | 25.1 | 7.0 | 15.0 | 6 |

| 2. kinety of right field, number of kinetids | 7.3 | 7.0 | 1.8 | 0.7 | 25.3 | 5.0 | 11.0 | 8 |

| 3. kinety of right field, length | 9.6 | 9.0 | 2.3 | 0.9 | 24.0 | 7.0 | 14.0 | 7 |

| 3. kinety of right field, number of kinetids | 6.4 | 6.0 | 1.7 | 0.6 | 26.4 | 5.0 | 9.0 | 8 |

| 4. kinety of right field, length | 9.5 | 9.5 | 2.4 | 1.0 | 25.6 | 6.0 | 13.0 | 6 |

| 4. kinety of right field, number of kinetids | 6.8 | 6.0 | 2.1 | 0.8 | 31.4 | 5.0 | 10.0 | 8 |

| 5. kinety of right field, length | 10.3 | 9.5 | 3.8 | 1.5 | 36.6 | 5.0 | 16.0 | 6 |

| 5. kinety of right field, number of kinetids | 6.6 | 6.0 | 2.4 | 0.8 | 36.0 | 4.0 | 11.0 | 8 |

| 6. kinety of right field, length | 13.2 | 14.0 | 3.2 | 1.3 | 24.2 | 8.0 | 17.0 | 6 |

| 6. kinety of right field, number of kinetids | 8.4 | 8.0 | 2.8 | 1.0 | 33.1 | 5.0 | 13.0 | 8 |

| 7. kinety of right field, length | 13.4 | 14.0 | 3.8 | 1.7 | 28.2 | 9.0 | 17.0 | 5 |

| 7. kinety of right field, number of kinetids | 8.6 | 8.0 | 3.2 | 1.2 | 37.4 | 6.0 | 14.0 | 7 |

| 8. kinety of right field, length | 14.4 | 17.0 | 4.5 | 2.0 | 31.3 | 9.0 | 18.0 | 5 |

| 8. kinety of right field, number of kinetids | 9.1 | 7.0 | 3.8 | 1.4 | 41.6 | 6.0 | 15.0 | 7 |

| 9. kinety of right field, length | 13.5 | 12.5 | 3.3 | 1.7 | 24.6 | 11.0 | 18.0 | 4 |

| 9. kinety of right field, number of kinetids | 10.3 | 9.5 | 3.6 | 1.8 | 35.1 | 7.0 | 15.0 | 4 |

| 10. kinety of right field, length | 12.0 | 11.0 | 2.6 | 1.5 | 22.0 | 10.0 | 15.0 | 3 |

| 10. kinety of right field, number of kinetids | 9.0 | 8.0 | 2.6 | 1.5 | 29.4 | 7.0 | 12.0 | 3 |

| 11. kinety of right field, length | 15.0 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| 11. kinety of right field, number of kinetids | 8.0 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| 12. kinety of right field, length | 10.5 | - | - | - | - | 9.0 | 12.0 | 2 |

| 12. kinety of right field, number of kinetids | 8.0 | - | - | - | - | 7.0 | 9.0 | 2 |

| Collar membranelles, numberd | 21.7 | 22.5 | 1.8 | 0.7 | 8.1 | 19.0 | 23.0 | 6 |

| Buccal membranelle, number | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 18 |

Data are based, if not stated otherwise, on protargol-impregnated and mounted specimens from field material

material preserved with Lugol’s iodine solution

measured as cord of organelle

counted in properly orientated morphostatic specimens or oral primordia of middle dividers.

1887 Tintinnopsis Davidoffii var. cylindrica - Daday, Mitt. zool. Stn Neapel 7: 553.

1907 Tintinnopsis cylindrica - Wright, Ann. Rep. Dept. of Marine and Fisheries, Fisheries Branch, Ottawa 39: 11 (raise to species rank).

1913 Tintinnopsis radix forma cylindrica - Laackmann, Akad. Wiss. Wien, Math. nat. Kl. 122: 145.

1929 Tintinnopsis davidoffi var. cylindrica Daday, 1887 - Kofoid and Campbell, Univ. Calif. Publs Zool. 34: 33 (first revisers).

1929 Tintinnopsis cylindrica Daday - Kofoid and Campbell, Univ. Calif. Publs Zool. 34: 33 (first revisers).

1932 Tintinnopsis kofoidi sp. nov. - Hada, Zool. Inst., Fac. Sci. Hokkaido Imp. Univ., Sapporo 30: 210 (new subjective synonym).

1981 Tintinnopsis kofoidii - Hargraves, J. Plankton Res. 3: 85.

1983 Tintinnopsis kofoidi - Stoecker et al., Mar. Biol. 75: 293 (growth experiments).

1986 Tintinnopsis kofoidi - Verity, Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 29: 117 (growth rates).

1990 Tintinnopsis kofoidi - Kamiyama and Aizawa, Bull. Plankton Soc. Jap. 36: 137 (excystment).

1997 Tintinnopsis kofoidi - Kamiyama, J. Oceanogr. 53: 299 (excystment).

2005 Tintinnopsis cylindrica - Kamiyama and Matsuyama, J. Plankton Res. 27: 307 (ingestion rate).

Non Tintinnopsis cylindrica n. sp. - Daday, 1892, Természetr. Füz. 15: 201 (junior homonym; now Tintinnopsis cylindrata Kofoid and Campbell, 1929).

Non Tintinnopsis cylindrica Daday - Entz, 1905, Áll. Közl. 4: 204 (now Tintinnopsis cylindrata Kofoid and Campbell, 1929).

Non Tintinnopsis cylindrica (Daday) - Entz, 1909a, Math. naturw. Ber. Ung. 25: 204 (now Tintinnopsis cylindrata Kofoid and Campbell, 1929).

Non Tintinnopsis cylindrica Daday - Entz, 1909b, Arch. Protistenk. 15: 118 (now Tintinnopsis cylindrata Kofoid and Campbell, 1929).

Non Tintinnopsis cylindrica Daday - Jaczó, 1940, Fragm. faun. hung. 3: 59 (now Tintinnopsis cylindrata Kofoid and Campbell, 1929).

Non Tintinnopsis cylindrica sp. n. - Meunier, 1910, Campagne Arctique de 1907: 140 (junior homonym; now Tintinnopsis spiralis Kofoid and Campbell, 1929).

Neotype material

Neotypified from plankton of the mixo-polyhaline basin (54°32′58″ N, 08°52′59″ E) in the Beltringharder Koog, as (i) no type material is available, (ii) the original description lacks many morphologic features, and (iii) the species has several proposed subjective synonyms.

Improved diagnosis (based on data from the type and neotype population)

Lorica on average 150-240 μm long and 45-50 μm wide orally, with agglutinated particles; Pasteur pipette-shaped, viz., cylindroidal for on average 65-75% of total length, posteriorly tapered, merging into straight cylindroidal process ~ 20 μm long and 10-15 μm wide. Cell on average 125-210 × 40-45 μm and elongate obconical, highly contractile. 2 macronuclear nodules and 2 micronuclei. Ventral kinety commences anterior to right ciliary field, consists of ~ 36 monokinetids. On average 11 kineties in right and 10 in left ciliary field, all composed of monokinetids and one anterior dikinetid, except for second and third ciliary row with two anterior dikinetids. About 36 dikinetids in dorsal kinety and 26 in posterior kinety, with a cilium only at each posterior basal body. Lateral ciliary field composed of ~ 11 monokinetidal kineties. On average 22 collar membranelles of which 4 extend into buccal cavity; single buccal membranelle. Marine and brackish waters.

Description of polder specimens

Loricae 75-220 μm long and 34-56 μm wide orally after preservation with Lugol’s iodine solution; Pasteur pipette-shaped, viz., cylindroidal for about two thirds of total length, anterior end transversely truncate, posteriorly tapered, merging into cylindroidal process. Process aborally open and usually transversely truncate, straight, 8-11 μm in diameter but highly variable in length possibly because it easily breaks off (Table 1). Matrix hyaline, incrustrated to various degrees by particles of non-biogenic origin (probably silt particles), diatom frustules and their fragments, and green globular organisms; no distinct spiralled or annulated structures recognizable (Figs 1a, d, e; 3a-e).

Fully extended cells 75-185 × 30-55 μm in vivo, elongate obconical, body proper gradually merges into slender, wrinkled stalk, attached to tapered portion of lorica (Figs 1a; 2c, d; 3a); disturbed or preserved cells contracted by ~ 40% and almost ellipsoidal (Figs 1b, c; 2a, b; 3b, d; Table 1). One ellipsoidal macronuclear nodule each in anterior and posterior cell half, with some large (~ 4 μm across) and several small (1-2 μm across) dark inclusions (probably nucleoli). Micronuclei adjacent to macronuclear nodules, globular, faintly impregnated with protargol. No contractile vacuole recognized. Cytopyge near mid-body. Myonemes not impregnated. Accessory combs rarely recognized in vivo (Fig. 3a), while striae, tentaculoids, and capsules not recognizable. Cytoplasm colourless, finely granulated, contains food vacuoles with coccal organisms (4-9 μm across) as well as centric (5-8 μm across) and pennate (10-16 × 2-3 μm) diatoms. Swims slowly (~ 0.1 mm s−1) forward, twitches back on obstacles. Disturbed specimens retract quickly (< 1 sec) into posterior portion of lorica, with motionless collar membranelles bent to centre of peristomial field (Fig. 3b); lorica abandonment never observed. When inconvenience stops, specimens slowly (> 1 min) extend and spread out the collar membranelles almost perpendicularly (Fig. 1a).

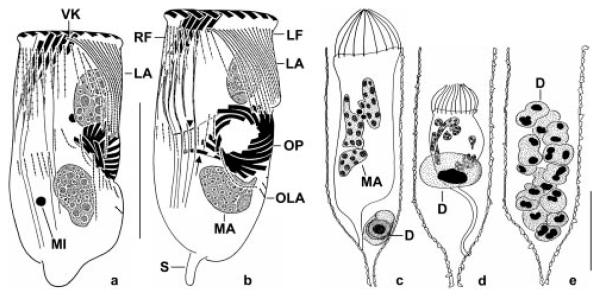

Figs 2a-e.

Tintinnopsis cylindrica after protargol impregnation. a, b - ventral views of middle dividers showing the oral primordium in a subsurface pouch posterior to the proter’s lateral ciliary field whose kineties are distinctly longer than in morphostatic specimens (cp. Figs 1b, c, f). Note the replication bands in the macronuclear nodules (b). Arrow marks the single buccal membranelle of the opisthe. Arrowhead denotes the short endoral membrane of the opisthe; c-e - lateral views of specimens in successive stages of dinoflagellate infection. The dinoflagellate completely sucks out the tintinnid cell (c, d), before it obtains the sporogenetic stage (e). Note the morphologic changes of the macronuclear nodules due to the infection (c, d). D - parasitic dinoflagellate (probably Duboscquella sp.), LA - proter’s lateral ciliary field, LF - left ciliary field, MA - macronuclear nodules, MI - micronuclei, OLA - opisthe’s lateral ciliary field, OP - oral primordium, RF - right ciliary field, S - contracted stalk, VK - ventral kinety. Scale bars: 50 μm.

General pattern of somatic ciliature as described in ’Terminology’ (Figs 1b, c, f). Length of kineties and number of kinetids usually highly variable possibly due to basal body proliferation or resorption in postdividers (see below; Table 1). Ventral kinety commences anterior to second or third kinety of right ciliary field, performs distinct leftward curvature, terminating near anterior end of posterior kinety, composed of densely spaced monokinetids; cilia decrease in length from ~ 11 μm in anterior portion to 3-4 μm in posterior. Kineties of right ciliary field composed of monokinetids and one anterior dikinetid, except for its first and second kinety that probably have two dikinetids anteriorly; cilia 2-4 μm long, except for the 9-11 μm long anteriormost dikinetidal cilia (soies, Fauré-Fremiet 1924), often apparently absent in posteriormost kinetids. Dorsal kinety commences at same level as right and left ciliary field and curves leftwards to base of stalk; cilia ~ 10 μm long and only at each posterior dikinetidal basal body. Posterior kinety commences in second quarter of cell posterior to last or penultimate kinety of lateral ciliary field and curves rightwards to base of stalk; cilia 6-7 μm long and only at each posterior dikinetidal basal body. Kineties of left ciliary field composed of monokinetids and one anterior dikinetid, almost gradually elongated from left to right; cilia 2-4 μm long, except for the 9-11 μm long anteriormost dikinetidal cilia (soies, Fauré-Fremiet 1924), often apparently absent in posteriormost kinetids. Kineties of lateral ciliary field commence ~ 1 μm anterior to those of left and right ciliary field, densely spaced and slightly curved, except for the rightmost kinety that extends parallel to the distinctly curved ventral kinety, 8-10 μm long (n = 6), composed of closely spaced monokinetids with cilia 2-4 μm long. Longitudinal argyrophilic fibres connect kinetids in ciliary rows.

Oral apparatus occupies anterior cell portion, perpendicular to main cell axis. Collar membranelles form closed spiral on peristomial rim, 1-2 μm apart, composed of three rows of basal bodies with cilia up to 25-30 μm long (Figs 1a-c; 3a). Two argyrophilic fibre bundles extend from each collar membranelle rightwards and leftwards, merging into a horizontally orientated circular fibre underneath the membranellar zone. Another argyrophilic fibre bundle commences at the left half of the circular fibre and extends posteriorly, terminating between the posterior and dorsal kinety (Fig. 1c). Eccentric buccal cavity contains one buccal membranelle and the proximal portions of four elongated collar membranelles, each associated with a longitudinal argyrophilic fibre bundle extending to the posterior quarter of cell proper (Fig. 1b). Endoral membrane inconspicuous, as apparently short and restricted to the buccal cavity.

Ontogenesis

Only few sufficiently impregnated division stages were found in the preparations (Figs 2a, b; 3f-h). Stomatogenesis commences with the apokinetal development of a small, cuneate field of basal bodies posterior to the lateral ciliary field. The oral primordium sinks into a subsurface pouch and membranelles differentiate. The posterior portion of the oral primordium performs a distinct rightwards curvature until the opisthe’s right side faces the proter’s ventral side. The endoral membrane is apparently very short and entirely located in the buccal cavity. In middle dividers, the proter’s ciliary fields are elongated compared to morphostatic specimens: the left field by ~ 80%, the right field by ~ 50%, and the lateral field by ~ 240%. In the opisthe, the right field is about one third shorter than in morphostatic specimens, whereas the lateral field is almost of same length; length of the left ciliary field is not recognizable. The ventral kinety curves along the lower right margin of the oral primordium. One replication band each traverses the macronuclear nodules. Only when the new oral apparatus evaginates, the two nodules fuse. Loricae embracing a resting cyst were not found.

DISCUSSION

Comparison of populations

The loricae from the type population are longer than those of the polder specimens (243 μm vs. 75-220 μm), while the oral diameter is almost identical (45 μm vs. 48 μm; Daday 1887). According to Laval-Peuto and Brownlee (1986), the oral diameter of a lorica is the least variable dimension and a taxonomically reliable character, whereas its length increases during lorica formation. Hence, the identification of the polder specimens with Tintinnopsis cylindrica is beyond reasonable doubt, especially, as Daday (1887) observed a similar number of collar membranelles and a similar position of the two macronuclear nodules. Schweyer (1909) recognized tentaculoids which were not found in the polder specimens; however, these organelles are probably contractile (Laval-Peuto 1994) and their absence should thus not be overestimated.

The literature data concerning the lorica dimensions of T. cylindrica and its synonyms fall into a size range of 105-300 × 33-60 μm (Brandt 1907; Okamura 1907; Laackmann 1913; Rossolimo 1922; Wailes 1925, 1943; Hada 1932a, c, 1937; Marshall 1934; Orsi 1936; Balech 1948, 1951; Biernacka 1948; Silva 1952; Cosper 1972; Gold and Morales 1975; Bakker and Phaff 1976; Kršinić 1980; Rampi and Zattera 1982; Stoecker et al. 1983; Yoo et al. 1988; Lipej 1992).

Comparison with similar species

There are several species and subspecies from marine and brackish waters which might be synonyms of Tintinnopsis cylindrica: T. davidoffii with two globular macronuclear nodules in posterior cell half; T. davidoffii var. longicauda and T. curvicauda with a curved lorica process (Daday 1887); T. pseudocylindrica with irregular aboral opening (Hada 1964); T. fracta with an obliquely truncate lorica process (Brandt 1906, 1907); T. coronata with an irregularly expanded oral lorica rim (Kofoid and Campbell 1929); T. levigata with a lorica 50-70 × 20-30 μm in size (Wailes 1925); T. platensis without agglutinated particles at the lorica process (Cunha and Fonseca 1917); T. aperta (Brandt 1906, 1907), T. lindeni (Daday 1887), T. panamensis, and T. tocantinensis (Kofoid and Campbell 1929) with a bulbous zone between the cylindroidal portion and the lorica process; Codonella annulata with an annulated lorica structure (Daday 1886); C. radix with a lorica up to 480 μm long (Imhof 1886); and Tintinnus annulatus, T. helix (Claparède and Lachmann 1859), and T. fistularis (Möbius 1887) with a spiralled lorica structure. The often very short descriptions of these taxa consider only or mainly lorica features, using small discrepancies in structure and shape for the establishment of a new species or variation. Although the formation of spiralled or annulated lorica structures is part of the life cycle in several tintinnids (paralorica and epilorica; Laval-Peuto 1981, 1994) and the lorica process might vary in shape and size due to environmental conditions, investigations of the cell morphology are required to justify a synonymization of the species mentioned above.

In only 16 tintinnid species, the main cytological features are known. The general ciliary pattern of T. cylindrica matches that of Codonella cratera (Foissner and Wilbert 1979), Stenosemella lacustris (Foissner and O’Donoghue 1990), Codonellopsis glacialis, Cymatocylis calyciformis (Petz et al. 1995), and the Cymatocylis affinis/convallaria-group (Wasik and Mikołajczyk 1994, Petz et al. 1995). Small and Lynn (1985), Laval-Peuto and Brownlee (1986), and Laval-Peuto (1994) provided some original or modified illustrations from Brownlee’s unpublished Master and Doctoral Theses, showing protargol-impregnated tintinnids with an apparently similar ciliary pattern: Tintinnopsis baltica, T. subacuta, Stenosemella steini, Favella sp., Climacocylis scalaroides, and Protorhabdonella simplex. Furthermore, the somatic ciliature of Tintinnopsis rapa, T. fimbriata, T. tubulosoides, T. campanula, Helicostomella subulata, and Leprotintinnus pellucidus are very much alike (own observ.). Further studies are required to elucidate whether the observed subtle differences in the structure, position, and curvature of the kineties are species- or genus-specific. On the other hand, the congener Tintinnopsis cylindrata resembles Tintinnidium fluviatile and Tintinnidium pusillum in the presence of ventral organelles and the absence of a dorsal kinety, a posterior kinety, and a lateral ciliary field (Foissner and Wilbert 1979). Nevertheless, its generic affiliation is not changed as the ciliary pattern of the type species of the genus Tintinnopsis, T. beroidea, is unknown.

Ontogenetic comparison

In only seven tintinnid species, ontogenesis was investigated after protargol impregnation: Tintinnopsis sp., Favella sp. (Brownlee 1983, Laval-Peuto 1994), Tintinnopsis cylindrata, Tintinnidium pusillum, T. semiciliatum, Codonella cratera (Petz and Foissner 1993), and Cymatocylis convallaria (Petz et al. 1995). Tintinnopsis cylindrata and the Tintinnidium species differ from Tintinnopsis cylindrica in the ciliary pattern (see above); hence, they are excluded from the following comparison.

The division stages of T. cylindrica match the observations on Codonella cratera (Petz and Foissner 1993), Cymatocylis convallaria (Petz et al. 1995), and apparently Favella sp. (Laval-Peuto 1994) very well in the position of the oral primordium. Likewise, the kineties of the proter are elongated and those of the opisthe are shortened compared to morphostatic specimens, indicating a resorption of basal bodies by the proter and a second round of basal body proliferation by the opisthe in late dividers or postdividers (this study, Brownlee 1983, Petz and Foissner 1993). Petz and Foissner (1993) assumed that an anteriorly elongated ventral kinety occurs only in dividers or postdividers, while we agree with Petz et al. (1995) in regarding it as the morphostatic state of the ciliary row.

Occurrence and ecology

The following compilation comprises merely records of Tintinnopsis cylindrica and the synonyms mentioned above. Note that only few of them were substantiated by morphometric data and/or illustrations (see ’Comparison of populations’) and that the morphologic variability of the species is unknown; thus, misidentifications cannot be excluded.

Daday (1887) discovered T. cylindrica in the Gulf of Naples. In the Mediterranean Sea and adjacent brackish water lagoons, the species was also found by several other authors (Brandt 1906, 1907; Schweyer 1909; Laackmann 1913; Orsi 1936; Rampi 1939, 1948, 1950; Margalef and Morales 1960; Kršinić 1979, 1980, 1987; Rassoulzadegan 1979; Rampi and Zattera 1982; Lakkis and Novel-Lakkis 1985; Lipej 1992; Lam-Hoai et al. 1997; Rougier and Lam Hoai 1997; Ounissi and Frehi 1999; Lam-Hoai and Rougier 2001; Sabancý and Koray 2001; Modigh and Castaldo 2002; Moscatello et al. 2004; Balk’s and Wasik 2005). Likewise, it was recorded in the North Atlantic (Wright 1907; Silva 1952; lorica of T. cylindrica less distinctly tapered, Cosper 1972; Gold and Morales 1975; Hargraves 1981; Stoecker et al. 1983; Verity 1986, 1987; Middlebrook et al. 1987; Sanders 1987; Gilron and Lynn 1989; Pilling et al. 1992; Leakey et al. 1993; Pierce and Turner 1994; Paulmier 1995; Tempelman and Agatha 1997; Urrutxurtu et al. 2003; Urrutxurtu 2004), South Atlantic (Balech 1948, 1951; Akselman and Santinelli 1989), Red Sea (Aboul-Ezz et al. 1995), Indian Ocean (Krishnamurthy and Santhanam 1978; Krishnamurthy et al. 1979, 1987; Damodara Naidu 1983; Damodara Naidu and Krishnamurthy 1985), North Pacific (Okamura 1907; Wailes 1925, 1943; Hada 1932a, b, c, 1937; Wang and Nie 1934; Konovalova and Rogachenko 1974; Yoo et al. 1988; Yoo and Kim 1990; Kamiyama and Aizawa 1990, 1992; Kamiyama and Tsujino 1996; Kamiyama 1997; Uye et al. 2000; Kamiyama et al. 2001; Kamiyama and Matsuyama 2005), and South Pacific (Brandt 1906, 1907; Marshall 1934; Burns 1983). Tintinnopsis cylindrica also occurred in the brackish waters of the Black (Rossolimo 1922) and Baltic Sea (Brandt 1906, 1907; T. cylindrica with exceptionally long lorica process, Biernacka 1948, 1968) and lagoons at the coast of the North Atlantic (this study, Bakker and Pauw 1975, Bakker and Phaff 1976, Bakker 1978, Agatha and Riedel-Lorjé 1997, Riedel-Lorjé et al. 1998), North Pacific (Hada 1937, Godhantaraman and Uye 2003), and Indian Ocean (Godhantaraman 2001, 2002). Accordingly, records substantiated by morphometric data are available from marine and brackish waters of subarctic, temperate, subtropical, and equatorial areas, while the species was apparently not found in polar regions. The spatial distribution of T. cylindrica might, however, change when further species or subspecies will definitely be synonymized and the morphologic variability of the species is better known.

In the polder basins, Tintinnopsis cylindrica was mainly recorded at salinities higher than 10‰ and temperatures above 8°C, that is, mostly during summer. It occasionally dominated the tintinnid community and had maximum abundances of ~ 4,400 individuals per litre in September 1991 and July 1992 in the mixo-polyhaline basins of the Beltringharder Koog and Speicherkoog Dithmarschen. The seasonal dynamics observed in the polder basins match the findings from other regions (Hada 1937; Bakker and Pauw 1975; Bakker and Phaff 1976; Bakker 1978; Hargraves 1981; Sanders 1987; Verity 1987; Leakey et al. 1993; Pierce and Turner 1994; Kamiyama and Tsujino 1996; Godhantaraman 2001, 2002).

Specimens infested by a parasitic dinoflagellate, probably Duboscquella sp., were occasionally found (Figs 2c-e). Hada (1932a) as well as Akselman and Santinelli (1989) described similar infection stages in Tintinnopsis kofoidi, whereas the infection was interpreted as sexual reproduction in the possibly synonymous species Tintinnus helix (Laackmann 1907). While the infection rate was apparently low in the polder basins, Duboscquella sp. significantly decimated ciliate stocks at the northeast coast of the USA (Coats and Heisler 1989).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a project of the Austrian Science Foundation dedicated to S. Agatha (FWF project P17752-B06) and a grant of the Federal Environmental Agency, Environmental Research Plan of the Minister for the Environment, Nature, Conservation and Nuclear Safety of the Federal Republic of Germany dedicated to J. C. Riedel-Lorjé (Grant 108 02 085/01). We thank K.-J. Hesse and B. Egge (Forschungs- und Technologie-Zentrum, University of Kiel, Germany) for the chemical analyses of the water samples and W. Foissner for his constructive criticism.

REFERENCES

- Aboul-Ezz SM, El-Serehy HA, Samaan AA, El-Rahman N. S. Abd. Distribution of planktonic protozoa in Suez Bay (Egypt) Bull. Nat. Inst. Oceanogr. Fish., A.R.E. 1995;21:183–204. [Google Scholar]

- Agatha S. A cladistic approach for the classification of oligotrichid ciliates (Ciliophora: Spirotricha) Acta Protozool. 2004a;43:201–217. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agatha S. Evolution of ciliary patterns in the Oligotrichida (Ciliophora, Spirotricha) and its taxonomic implications. Zoology. 2004b;107:153–168. doi: 10.1016/j.zool.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agatha S, Riedel-Lorjé JC. Taxonomy and ecology of some Oligotrichea from brackish water basins at the west coast of Schleswig-Holstein (northern Germany) J. Euk. Microbiol. 1997;44:27A. [Google Scholar]

- Agatha S, Hesse K-J, Nehring S, Riedel-Lorjé JC. Plankton und Nährstoffe in Brackwasserbecken am Rande des Schleswig-Holsteinischen Wattenmeeres unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Ciliaten und Dinoflagellaten-Dauerstadien sowie blütenbildender und toxischer Formen. Umweltbundesamt; Berlin: 1994. pp. 1–242. Report No. 10802085/01. [Google Scholar]

- Akselman R, Santinelli N. Observaciones sobre dinoflagelados parasitos en el litoral Atlantico sudoccidental. Physis, B. Aires, Sec. A. 1989;47:43–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker C. Some reflections about the structure of the pelagic zone of the brackish Lake Grevelingen (SW-Netherlands) Hydrobiol. Bull. 1978;12:67–84. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker C, de Pauw N. Comparison of plankton assemblages of identical salinity ranges in estuarine tidal, and stagnant environments II. Zooplankton. Neth. J. Sea Res. 1975;9:145–165. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker C, Phaff WJ. Tintinnida from coastal waters of the S.W.-Netherlands I. The genus Tintinnopsis Stein. Hydrobiologia. 1976;50:101–111. [Google Scholar]

- Balech E. Tintinnoinea de Atlantida (R. O. del Uruguay) (Protozoa Ciliata Oligotr.) Comun. Mus. Argent. Cienc nat. Bernardino Rivadavia, Ser. cienc. zool. 1948;7:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Balech E. Nuevos datos sobre Tintinnoinea de Argentina y Uruguay. Physis, B. Aires. 1951;20:291–302. [Google Scholar]

- Balk’s N, Wasik A. Species composition of the tintinnids found in the neritic water of Bozcaada Island, Aegean Sea, Turkey. FEB. 2005;14:327–333. [Google Scholar]

- Biernacka I. Tintinnoinea in the Gulf of Gdańsk and adjoining waters. Biul. Morsk. Labor. Ryb. w Gdyni. 1948;4:73–91. (in Polish with English summary) [Google Scholar]

- Biernacka I. Influence de la salinité et de la thermique sur les protistes de la mer Baltique et de la lagune de la Vistule. Ekol. Polska, Ser. A. 1968;16:261–278. [Google Scholar]

- Blatterer H, Foissner W. Beiträge zur Ciliatenfauna (Protozoa: Ciliophora) der Amper (Bayern, Bundesrepublik Deutschland) Arch. Protistenk. 1990;138:93–115. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt K. Die Tintinnodeen der Plankton Expedition. Tafelerklärungen nebst kurzer Diagnose der neuen Arten. In: Hensen V, editor. Ergebn. Plankton-Exped. Humboldt-Stiftung 3 La. Lipsius and Tischer; Kiel, Leipzig: 1906. pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt K. Die Tintinnodeen der Plankton Expedition. Systematischer Teil. In: Hensen V, editor. Ergebn. Plankton-Exped. Humboldt-Stiftung 3 La. Lipsius and Tischer; Kiel, Leipzig: 1907. pp. 1–488. [Google Scholar]

- Brownlee DC. Stomatogenesis in the tintinnine ciliates with notes on lorica formation. J. Protozool. 1983;30:1A. [Google Scholar]

- Burns DA. The distribution and morphology of tintinnids (ciliate protozoans) from the coastal waters around New Zealand. N. Z. J. Mar. Freshwater Res. 1983;17:387–406. [Google Scholar]

- Bütschli O. Erster Band. Protozoa. III. Abtheilung. Infusoria und System der Radiolaria. In: Bronn HG, editor. Klassen und Ordnungen des Thier-Reichs, wissenschaftlich dargestellt in Wort und Bild. C. F. Winter’sche Verlagshandlung; Leipzig: 1887-1889. pp. 1098–2035. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell AS. The cytology of Tintinnopsis nucula (Fol) Laackmann with an account of its neuromotor apparatus, division, and a new intranuclear parasite. Univ. Calif. Publs Zool. 1926;29:179–236. [Google Scholar]

- Capriulo GM, Taveras J, Gold K. Ciliate feeding: effect of food presence or absence on occurrence of striae in tintinnids. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1986;30:145–158. [Google Scholar]

- Chatton E, Lwoff A, Lwoff M, Monod J-L. La formation de l’ébauche buccale postérieure chez les ciliés en division et ses relations de continuité topographique et génétique avec la bouch antérieure. C. R. Soc. Biol. 1931;107:540–544. [Google Scholar]

- Choi JK, Coats DW, Brownlee DC, Small EB. Morphology and infraciliature of three species of Eutintinnus (Ciliophora; Tintinnina) with guidelines for interpreting protargol-stained tintinnine ciliates. J. Protozool. 1992;39:80–92. [Google Scholar]

- Claparède É, Lachmann J. Études sur les infusoires et les rhizopodes. Mém. Inst. natn. génev. 1859;6:261–482. (year 1858) [Google Scholar]

- Coats DW, Heisler JJ. Spatial and temporal occurrence of the parasitic dinoflagellate Duboscquella cachoni and its tintinnine host Eutintinnus pectinis in Chesapeake Bay. Mar. Biol. 1989;101:401–409. [Google Scholar]

- Corliss JO. Characterization, Classification and Guide to the Literature. 2nd ed Pergamon Press; Oxford, New York, Toronto, Syndney, Paris, Frankfurt: 1979. The Ciliated Protozoa. [Google Scholar]

- Corliss JO. Comments on the neotypification of protists, especially ciliates (Protozoa, Ciliophora) Bull. zool. Nom. 2003;60:48–49. [Google Scholar]

- Cosper TC. The identification of tintinnids (Protozoa: Ciliata: Tintinnida) of the St. Andrew Bay system, Florida. Bull. Mar. Sci. 1972;22:391–418. [Google Scholar]

- Cunha A. M. da, Fonseca O. da. O microplancton do Atlantico nas imediaȩões de Mar del Plata. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 1917;9:140–142. [Google Scholar]

- von Daday E. Ein kleiner Beitrag zur Kenntnis der Infusorien-Fauna des Golfes von Neapel. Mitt. zool. Stn Neapel. 1886;6:481–498. [Google Scholar]

- von Daday E. Monographie der Familie der Tintinnodeen. Mitt. zool. Stn Neapel. 1887;7:473–591. [Google Scholar]

- von Daday E. Die mikroskopische Thierwelt der Mezöséger Teiche. Természetr. Füz. 1892;15:166–207. [Google Scholar]

- Naidu W. Damodara. Tintinnida (Protozoa: Ciliata) - a vital link in the estuarine food web. Mahasagar Bull. Nat. Inst. Oceanogr. 1983;16:403–407. [Google Scholar]

- Damodara Naidu W, Krishnamurthy K. Biogeographical distribution of tintinnids (Protozoa: Ciliata) from Porto Novo waters. Mahasagar Bull. Nat. Inst. Oceanogr. 1985;18:417–423. [Google Scholar]

- Deroux G. Quelques précisions sur Strobilidium gyrans Schewiakoff. Cah. Biol. mar. 1974;15:571–588. [Google Scholar]

- Entz G., sen. Über Infusorien des Golfes von Neapel. Mitt. zool. Stn Neapel. 1884;5:289–444. [Google Scholar]

- Entz G., jun. Az Édesvízi Tintinnidák. Áll. Közl. 1905;4:198–218. [Google Scholar]

- Entz G., sen Die Süsswasser-Tintinniden. Math. naturw. Ber. Ung. 1909a;25:197–225. [Google Scholar]

- Entz G., jun. Studien über Organisation und Biologie der Tintinniden. Arch. Protistenk. 1909b;15:93–226. [Google Scholar]

- Entz G., jun. Über Struktur und Funktion der Membranulae der Tintinniden, speziell von Petalotricha ampulla. X. Congr. Int. Zool., Sec. V Evertébrés. 1929:887–895. [Google Scholar]

- Entz G., jun Fibrillen in “Favella Ehrenbergii” Jörgensen (“Ciliata, Oligotricha”) Int. Congr. Zool. 1937;14:1446–1448. [Google Scholar]

- Fauré-Fremiet E. Contribution a la connaissance des infusoires planktoniques. Bull. biol. Fr. Belg. 1924;6(Suppl.):1–171. [Google Scholar]

- Fauré-Fremiet E. Remarques sur la systématique des ciliés Oligotrichida. Protistologica. 1970;5:345–352. (year 1969) [Google Scholar]

- Foissner W. Basic light and scanning electron microscopic methods for taxonomic studies of ciliated protozoa. Eur. J. Protistol. 1991;27:313–330. doi: 10.1016/S0932-4739(11)80248-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foissner W. Neotypification of protists, especially ciliates (Protozoa, Ciliophora) Bull. zool. Nom. 2002;59:165–169. [Google Scholar]

- Foissner W, O’Donoghue PJ. Morphology and infraciliature of some freshwater ciliates (Protozoa: Ciliophora) from Western and South Australia. Invert. Taxon. 1990;3:661–696. [Google Scholar]

- Foissner W, Wilbert N. Morphologie, Infraciliatur und ökologie der limnischen Tintinnina: Tintinnidium fluviatile Stein, Tintinnidium pusillum Entz, Tintinnopsis cylindrata Daday und Codonella cratera (Leidy) (Ciliophora, Polyhymenophora) J. Protozool. 1979;26:90–103. [Google Scholar]

- Foissner W, Agatha S, Berger H. Soil ciliates (Protozoa, Ciliophora) from Namibia (Southwest Africa), with emphasis on two contrasting environments, the Etosha region and the Namib Desert. Part I: Text and line drawings. Part II: Photographs. Denisia. 2002;5:1–1459. [Google Scholar]

- Gilron GL, Lynn DH. Assuming a 50% cell occupancy of the lorica overestimates tintinnine ciliate biomass. Mar. Biol. 1989;103:413–416. [Google Scholar]

- Godhantaraman N. Seasonal variations in taxonomic composition, abundance and food web relationship of microzooplankton in estuarine and mangrove waters, Parangipettai region, southeast coast of India. Indian J. Mar. Sci. 2001;30:151–160. [Google Scholar]

- Godhantaraman N. Seasonal variations in species composition, abundance, biomass and estimated production rates of tintinnids at tropical estuarine and mangrove waters, Parangipettai, southeast coast of India. J. Mar. Syst. 2002;36:161–171. [Google Scholar]

- Godhantaraman N, Uye S. Geographical and seasonal variations in taxonomic composition, abundance and biomass of microzooplankton across a brackish-water lagoonal system of Japan. J. Plankton Res. 2003;25:465–482. [Google Scholar]

- Gold K. Scanning electron microscopy of Tintinnopsis parva: studies on particle accumulation and the striae. J. Protozool. 1979;26:415–419. [Google Scholar]

- Gold K, Morales EA. Seasonal changes in lorica sizes and the species of Tintinnida in the New York Bight. J. Protozool. 1975;22:520–528. [Google Scholar]

- Hada Y. Descriptions of two new neritic Tintinnoinea, Tintinnopsis japonica and Tps. kofqoidi with a brief note on an unicellular organism parasitic on the latter. Zool. Inst., Fac. Sci. Hokkaido Imp. Univ., Sapporo. 1932a;30:209–212. [Google Scholar]

- Hada Y. Report of the biological survey of Mutsu Bay. 24. The pelagic Ciliata, suborder Tintinnoinea. Sci. Rep. Tohoku Imp. Univ., Ser. 4, Biol. 1932b;7:553–573. [Google Scholar]

- Hada Y. The Tintinnoinea from the Sea of Okhotsk and its neighborhood. J. Fac. Sci. Hokkaido Univ. 1932c;2:37–59. [Google Scholar]

- Hada Y. The fauna of Akkeshi Bay IV. The pelagic Ciliata. J. Fac. Sci. Hokkaido Univ. Zool. 1937;5:143–216. [Google Scholar]

- Hada Y. New species of the Tintinnida found from the Inland Sea. Bull. Suzugamine Women’s Coll., Nat. Sci. 1964;11:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Haeckel E. Ueber einige neue pelagische Infusorien. Jen. Z. Naturw. 1873;7:561–568. [Google Scholar]

- Hargraves PE. Seasonal variations of tintinnids (Ciliophora: Oligotrichida) in Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island, U.S.A. J. Plankton Res. 1981;3:81–91. [Google Scholar]

- Hedin H. On the ultrastructure of Favella ehrenbergii (Claparéde & Lachmann) and Parafavella gigantea (Brandt), Protozoa, Ciliata, Tintinnida. Zoon. 1975;3:11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hofker J. Studien über Tintinnoidea. Arch. Protistenk. 1931;75:315–402. [Google Scholar]

- Imhof OE. Über microscopische pelagische Thiere aus den Lagunen von Venedig. Zool. Anz. 1886;9:101–104. [Google Scholar]

- Jaczó I. Die Süsswasser-Tintinniden Ungarns. Fragm. faun. hung. 1940;3:59–60. [Google Scholar]

- Kamiyama T. Effects of phytoplankton abundance on excystment of tintinnid ciliates from marine sediments. J. Oceanogr. 1997;53:299–302. [Google Scholar]

- Kamiyama T, Aizawa Y. Excystment of tintinnid ciliates from marine sediment. Bull. Plankton Soc. Jap. 1990;36:137–139. [Google Scholar]

- Kamiyama T, Aizawa Y. Effects of temperature and light on tintinnid excystment from marine sediments. Nippon Suisan Gakk. 1992;58:877–884. [Google Scholar]

- Kamiyama T, Matsuyama Y. Temporal changes in the ciliate assemblage and consecutive estimates of their grazing effect during the course of a Heterocapsa circularisquama bloom. J. Plankton Res. 2005;27:303–311. [Google Scholar]

- Kamiyama T, Tsujino M. Seasonal variation in the species composition of tintinnid ciliates in Hiroshima Bay, the Seto Inland Sea of Japan. J. Plankton Res. 1996;18:2313–2327. [Google Scholar]

- Kamiyama T, Takayama H, Nishii Y, Uchida T. Grazing impact of the field ciliate assemblage on a bloom of the toxic dinoflagellate Heterocapsa circularisquama. Plankton Biol. Ecol. 2001;48:10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Kim JS, Jeong HJ, Strüder-Kypke MC, Lynn DH, Kim S, Kim JH, Lee SH. Parastrombidinopsis shimi n. gen., n. sp. (Ciliophora: Choreotrichia) from the coastal waters of Korea: morphology and small subunit ribosomal DNA sequence. J. Euk. Microbiol. 2005;52:514–522. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2005.00062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kofoid CA, Campbell AS. A conspectus of the marine and fresh-water Ciliata belonging to the suborder Tintinnoinea, with descriptions of new species principally from the Agassiz Expedition to the eastern tropical Pacific 1904-1905. Univ. Calif. Publs Zool. 1929;34:1–403. [Google Scholar]

- Kofoid CA, Campbell AS. Reports on the scientific results of the expedition to the eastern tropical Pacific, in charge of Alexander Agassiz, by the U. S. Fish Commission Steamer “Albatross,” from October, 1904, to March, 1905, Lieut.-Commander L. N. Garrett, U. S. N., Commanding. XXXVII. The Ciliata: The Tintinnoinea. Bull. Mus. comp. Zool. Harv. 1939;84:1–473. [Google Scholar]

- Konovalova GV, Rogachenko LA. Species composition and population dynamics of planktonic infusorians (Tintinnina) in Amur Bay. Oceanol. Acad. Sci. USSR. 1974;14:561–566. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurthy K, Santhanam R. Dictyocysta seshaiyai sp. nov. (Protozoa, Ciliatea, Tintinnida) from Porto Novo, India. Arch. Protistenk. 1978;120:138–141. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurthy K, Naidu W. Damodara, Santhanam R. Further studies on tintinnids (Protozoa: Ciliata) Arch. Protistenk. 1979;122:171–180. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurthy K, Naidu W. Damodara, Ali M. A. Sultan. Community structure and organization of tintinnids (Protozoa: Ciliata) In: Thompson M-F, Sarojini R, Nagabhushanam R, editors. Indian Ocean - Biology of Benthic Marine Organisms - Techniques and Methods as Applied to the Indian Ocean. A. A. Balkema; Rotterdam: 1987. pp. 307–313. [Google Scholar]

- Kršinić F. Cruises of the research vessel “Vila Velebita” in the Kvarner region of the Adriatic Sea XI. Microzooplankton. Thalassia Jugosl. 1979;15:179–192. [Google Scholar]

- Kršinić F. Qualitative and quantitative investigations of the tintinnids along the eastern coast of the Adriatic. Acta Adriat. 1980;21:19–104. (in Croatian with English summary) [Google Scholar]

- Kršinić F. On the ecology of Tintinnines in the Bay of Mali Ston (eastern Adriatic) Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 1987;24:401–418. [Google Scholar]

- Laackmann H. Antarktische Tintinnen. Zool. Anz. 1907;31:235–239. [Google Scholar]

- Laackmann H. Adriatische Tintinnodeen. Akad. Wiss. Wien, Math. nat. Kl. 1913;122:123–167. [Google Scholar]

- Lakkis S, Novel-Lakkis V. Considerations sur la repartition des tintinnides au large de la cote libanaise. Rapp. Comm. int. Mer. Médit. 1985;29:171–172. [Google Scholar]

- Lam-Hoai T, Rougier C. Zooplankton assemblages and biomass during a 4-period survey in a northern Mediterranean coastal lagoon. Water Res. 2001;35:271–283. doi: 10.1016/s0043-1354(00)00243-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam-Hoai T, Rougier C, Lasserre G. Tintinnids and rotifers in a northern Mediterranean coastal lagoon. Structural diversity and function through biomass estimations. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1997;152:13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Laval M. Mise en évidence par la microscopie électronique d’un organite d’un type nouveau chez les ciliés Tintinnides. C. R. Acad. Sci. 1971;273:1383–1386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laval M. Ultrastructure de Petalotricha ampulla (Fol). Comparaison avec d’autres tintinnides et avec les autres ordres de ciliés. Protistologica. 1972;8:369–386. [Google Scholar]

- Laval-Peuto M. Construction of the lorica in Ciliata Tintinnina. In vivo study of Favella ehrenbergii: variability of the phenotypes during the cycle, biology, statistics, biometry. Protistologica. 1981;17:249–272. [Google Scholar]

- Laval-Peuto M. Classe des Oligotrichea Bütschli, 1887. Ordre des Tintinnida Kofoid et Campbell, 1929. In: de Puytorac P, editor. Traité de Zoologie. Anatomie, Systématique, Biologie. II. Infusoires Ciliés. 2. Systématique. Masson; Paris, Milan: 1994. pp. 181–219. [Google Scholar]

- Laval-Peuto M, de Cao M. S. Barria. Les capsules, extrusomes caracteristiques des Tintinnina (Ciliophora), permettent une classification evolutive des genres et des familles du sous-ordre. Ile Réun. Scientif. GRECO 88, Trav. C.R.M. 1987;8:53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Laval-Peuto M, Brownlee DC. Identification and systematics of the Tintinnina (Ciliophora): evaluation and suggestions for improvement. Annls Inst. océanogr., Paris. 1986;62:69–84. [Google Scholar]

- Laval-Peuto M, Gold K, Storm ER. The ultrastructure of Tintinnopsis parva. Trans. Am. microsc. Soc. 1979;98:204–212. [Google Scholar]

- Leakey RJG, Burkill PH, Sleigh MA. Planktonic ciliates in Southampton water: quantitative taxonomic studies. J. mar. biol. Ass. U.K. 1993;73:579–594. [Google Scholar]

- Lipej L. The tintinnid fauna (Tintinnina, Choreotrichida, Ciliophora) in Slovenian coastal waters. Razpr. IV. Razr. Sazu. 1992;33:93–113. [Google Scholar]

- Margalef R, Morales E. Fitoplancton de las costas de Blanes (Gerona), de julio de 1956a junio de 1959. Inv. Pesq. 1960;14:3–31. (with English summary) [Google Scholar]

- Marshall SM. The Silicoflagellata and Tintinnoinea. Scient. Rep. Gt Barrier Reef Exped., London. 1934;4:623–664. [Google Scholar]

- Meunier A. Campagne Arctique de 1907. C. Bulens; Brussels: 1910. Microplankton des Mers de Barents et de Kara. [Google Scholar]

- Middlebrook K, Emerson CW, Roff JC, Lynn DH. Distribution and abundance of tintinnids in the Quoddy Region of the Bay of Fundy. Can. J. Zool. 1987;65:594–601. [Google Scholar]

- Möbius K. Systematische Darstellung der Thiere des Plankton gewonnen in der westlichen Ostsee und auf einer Fahrt von Kiel in den Atlantischen Ocean bis jenseit der Hebriden. Ber. Komm. wiss. Unters. Deutsch. Meere, Kiel. 1887;5:108–126. [Google Scholar]

- Modigh M, Castaldo S. Variability and persistence in tintinnid assemblages at a Mediterranean coastal site. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 2002;28:299–311. [Google Scholar]

- Moscatello S, Rubino F, Saracino OD, Fanelli G, Belmonte G, Boero F. Plankton biodiversity around the Salento Peninsula (south east Italy): an integrated water/sediment approach. Sci. Mar. 2004;68(Suppl. 1):85–102. [Google Scholar]

- Okamura K. An annotated list of plankton microrganisms of the Japanese coast. An. Zool. Jap. 1907;6:125–151. [Google Scholar]

- Orsi A. Tintinnidi del Golfo di Genova. Boll. Mus. Lab. Zool. Anat. Comp. Univ. Genova. 1936;16:3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ounissi M, Frehi H. Variabilité du microphytoplancton et des Tintinnida (protozoaires ciliés) d’un secteur eutrophe du golfe d’Annaba (Méditerranée sud-occidentale) Cah. Biol. mar. 1999;40:141–153. [Google Scholar]

- Paulmier G. Les tintinnides (Ciliophora, Oligotrichida, Tintinnina) des côtes françaises de la manche et de l’Atlantique. Annls Soc. Sci. Nat. Charente-Maritime. 1995;8:453–487. [Google Scholar]

- Petz W, Foissner W. Morphogenesis in some freshwater tintinnids (Ciliophora, Oligotrichida) Eur. J. Protistol. 1993;29:106–120. doi: 10.1016/S0932-4739(11)80303-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petz W, Song W, Wilbert N. Taxonomy and ecology of the ciliate fauna (Protozoa, Ciliophora) in the endopagial and pelagial of the Weddell Sea, Antarctica. Stapfia. 1995;40:1–223. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce RW, Turner JT. Plankton studies in Buzzards Bay, Massachusetts, USA. IV. Tintinnids, 1987 to 1988. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1994;112:235–240. [Google Scholar]

- Pilling ED, Leakey RJG, Burkill PH. Marine pelagic ciliates and their productivity during summer in Plymouth coastal waters. J. mar. biol. Ass. U.K. 1992;72:265–268. [Google Scholar]

- Rampi L. Primo contributo alla conoscenza dei tintinnoidi del Mare Ligure. Atti Soc. ital. Sci. nat. 1939;78:67–81. [Google Scholar]

- Rampi L. I Tintinnoidi delle acque di San Remo II. Osservazioni e conclusioni. Boll. Pesca Piscic. Idrobiol. N.S. 1948;3:50–56. [Google Scholar]

- Rampi L. I Tintinnoidi delle acque di Monaco raccolti dall’Eider nell’anno 1913. Bull. Inst. océanogr. Monaco. 1950;965:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Rampi L, Zattera A. Chiave per la determinazione dei tintinnidi mediterranei. Comitato nazionale per la ricerca e per lo sviluppo dell’energia nucleare e delle energie alternative, ENEART/BIO. 1982;28(82):1–104. [Google Scholar]

- Rassoulzadegan F. Évolution annuelle des ciliés pélagiques en Méditerranée nord-occidentale. II. Ciliés oligotriches. Tintinnides (Tintinnina) Inv. Pesq. 1979;43:417–448. [Google Scholar]

- Riedel-Lorjé JC, Nehring S, Hesse K-J, Agatha S. Plankton und Nährstoffe in Brackwasserbecken am Rande des Schleswig-Holsteinischen Wattenmeeres unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Ciliaten und Dinoflagellaten-Dauerstadien sowie blütenbildender und toxischer Formen. 69/97. Umweltbundesamt; Texte: 1998. ökosystemforschung Wattenmeer - Teilvorhaben Schleswig-Holsteinisches Wattenmeer; pp. 1–102. [Google Scholar]

- Rossolimo L. Die Tintinnodea des Schwarzen Meeres. Russk. Arkh. Protist. 1922;1:22–34. (in Russian with German summary) [Google Scholar]

- Rougier C, Hoai T. Lam. Biodiversity through two groups of microzooplankton in a coastal lagoon (Étang de Thau, France) Vie Milieu. 1997;47:387–394. [Google Scholar]

- Sabancý F. ç., Koray T. The impact of pollution on the vertical and horizontal distribution of microplankton in Izmir Bay (Aegean Sea) EU J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2001;18:187–202. (in Turkish with English summary) [Google Scholar]

- Sanders RW. Tintinnids and other microzooplankton - seasonal distributions and relationships to resources and hydrography in a Maine estuary. J. Plankton Res. 1987;9:65–77. [Google Scholar]

- Schweyer A. Zur Kenntnis des Tintinnodeenweichkörpers, nebst einleitenden Worten über die Hülsenstruktur und die Hülsenbildung. Arch. Protistenk. 1909;18:134–189. [Google Scholar]

- Silva E. de Sousa. Tintinnoinea das águas litorais da Guiné Portuguesa. Bol. Cult. Guiné Portug. 1952;25:607–623. [Google Scholar]

- Small EB, Lynn DH. Phylum Ciliophora Doflein, 1901. In: Lee JJ, Hutner SH, Bovee EC, editors. An Illustrated Guide to the Protozoa. Society of Protozoologists, Allen Press; Lawrence, Kansas: 1985. pp. 393–575. [Google Scholar]

- Sniezek JH, Capriulo GM, Small EB, Russo A. Nolaclusilis hudsonicus n. sp. (Nolaclusiliidae n. fam.) a bilaterally symmetrical tintinnine ciliate from the lower Hudson River estuary. J. Protozool. 1991;38:589–594. [Google Scholar]

- Snoeyenbos-West OLO, Salcedo T, McManus GB, Katz LA. Insights into the diversity of choreotrich and oligotrich ciliates (Class: Spirotrichea) based on genealogical analyses of multiple loci. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2002;52:1901–1913. doi: 10.1099/00207713-52-5-1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder RA, Brownlee DC. Nolaclusilis bicornis n. g., n. sp. (Tintinnina: Tintinnidiidae): a tintinnine ciliate with novel lorica and cell morphology from the Chesapeake Bay estuary. J. Protozool. 1991;38:583–589. [Google Scholar]

- Song W. Studies on the morphology of three tintinnine ciliates from the Weddell Sea, Antarctic (Ciliophora, Tintinnina) Antarct. Res. (Chin. Ed.) 1993;5:34–42. (in Chinese with English summary) [Google Scholar]

- Song W, Wilbert N. Taxonomische Untersuchungen an Aufwuchsciliaten (Protozoa, Ciliophora) im Poppelsdorfer Weiher, Bonn. Lauterbornia. 1989;3:1–221. [Google Scholar]

- Song W, Wilbert N. Benthische Ciliaten des Süßwassers. In: Röttger R, editor. Praktikum der Protozoologie. G. Fischer; Stuttgart: 1995. pp. 156–168. [Google Scholar]

- Stoecker D, Davis LH, Provan A. Growth of Favella sp. (Ciliata: Tintinnina) and other microzooplankters in cages incubated in situ and comparison to growth in vitro. Mar. Biol. 1983;75:293–302. [Google Scholar]

- Strüder-Kypke MC, Lynn DH. Sequence analyses of the small subunit rRNA gene confirm the paraphyly of oligotrich ciliates sensu lato and support the monophyly of the subclasses Oligotrichia and Choreotrichia (Ciliophora, Spirotrichea) J. Zool. 2003;260:87–97. [Google Scholar]

- Tappan H, Loeblich AR., jun. Lorica composition of modern and fossil tintinnida (ciliate Protozoa), systematics, geologic distribution, and some new tertiary taxa. J. Paleont. 1968;42:1378–1394. [Google Scholar]

- Tempelman D, Agatha S. Biomonitoring van microzoöplankton in de Nederlandse zoute wateren 1996. Rijkswaterstaat, Rijksinstituut voor Kust en Zee. 1997;97.T0017b:1–77. [Google Scholar]

- Urrutxurtu I. Seasonal succession of tintinnids in the Nervión River estuary, Basque Country, Spain. J. Plankton Res. 2004;26:307–314. [Google Scholar]

- Urrutxurtu I, Orive E, de la Sota A. Seasonal dynamics of ciliated protozoa and their potential food in an eutrophic estuary (Bay of Biscay) Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2003;57:1169–1182. [Google Scholar]

- Uye S-I, Nagano N, Shimazu T. Abundance, biomass, production and trophic roles of micro- and net-zooplankton in Ise Bay, Central Japan, in Winter. J. Oceanogr. 2000;56:389–398. [Google Scholar]

- Valbonesi A, Luporini P. Description of two new species of Euplotes and Euplotes rariseta from Antarctica. Polar Biol. 1990;11:47–53. [Google Scholar]

- Verity PG. Growth rates of natural tintinnid populations in Narragansett Bay. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1986;29:117–126. [Google Scholar]

- Verity PG. Abundance, community composition, size distribution, and production rates of tintinnids in Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 1987;24:671–690. [Google Scholar]

- Wailes GH. Tintinnidae from the Strait of Georgia, B.C. Contr. Can. Biol. Fish., Ottawa, N.S. 1925;2:531–539. [Google Scholar]

- Wailes GH. 1. Protozoa 1f. Ciliata 1g. Suctoria. Can. Pacific Fauna. 1943;1:1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Wang CC, Nie D. On the marine protozoa of Amoy. Proc. 5th Pan-Pacific Sci. Congr. 1934:4207–4211. [Google Scholar]

- Wasik A, Mikołajczyk E. The morphology and ultrastructure of the Antarctic ciliate, Cymatocylis convallaria (Tintinnina) Acta Protozool. 1992;31:233–239. [Google Scholar]

- Wasik A, Mikołajczyk E. Infraciliature of Cymatocylis affinis/convallaria (Tintinnina) Acta Protozool. 1994;33:79–85. [Google Scholar]

- Wright RR. The plankton of eastern Nova Scotia waters. An account of floating organisms upon which young food-fishes mainly subsist. Ann. Rep. Dept. Mar. Fish., Fish. Branch, Ottawa. 1907;39:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo K-I, Kim Y-O. Taxonomical studies on tintinnids (Protozoa: Ciliata) in Korean coastal waters 2. Yongil Bay. Korean J. Syst. Zool. 1990;6:87–121. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo K-I, Kim Y-O, Kim D-Y. Taxonomical studies on tintinnids (Protozoa: Ciliata) in Korean coastal waters. 1. Chinhae Bay. Korean J. Syst. Zool. 1988;4:67–90. [Google Scholar]