Abstract

Theory suggests that shame should be positively related to aggression while guilt may serve as a protective factor. Little research has examined mediators between the moral emotions and aggression. Results using path analyses in four diverse samples were consistent with a model of no direct relationship between shame-proneness and aggression. There was, however, a significant indirect relationship through externalization of blame, but mostly when aggression was measured using self-report. Guilt-proneness, on the other hand, showed a direct negative relationship to aggression whether using self-report or other reports of aggression. Guilt was also inversely related to aggression indirectly through externalization of blame and empathy. Identifying these differing mechanisms may be useful in developing more effective interventions for aggressive individuals.

Keywords: Shame, Guilt, Aggression, Externalization of Blame, Empathy

TO THE EDITOR: Dan Savage’s article [“Fear the Geek”] touched a chord with me. I was one of those outcasts who was mercilessly teased…The morning after the Columbine High shootings, I read the profiles of the gunmen on CNN’s website. When I read the accounts about how they were “outcasts” and how others teased them, it brought back a lot of strong emotions and painful memories from my school years. My heart goes out to those killed and injured in the shootings… But I also could relate to the overwhelming sense of rage and shame of the two gunmen, and apparently that was the impetus behind what they did.

Brian Heath http://www.thestranger.com/seattle/Letters?issue=1038

Anecdotal accounts of events leading up to school shootings suggest shame may be a root cause of some violence. Overwhelming feelings of shame and guilt may cause individuals to aggress. Yet shame and guilt are also often described as “moral” emotions that help keep us on the moral path – e.g. resisting temptation, inhibiting aggression, and doing the right thing. So, do these moral emotions lead to aggression or are they protective factors? Or does the relationship depend on the moral emotion as well as the outcome of interest?

Previous research suggests that shame is positively linked to hostility and aggression, whereas guilt is negatively related to these “externalizing” dimensions (Bennett, Sullivan, & Lewis, 2005; Ferguson, Stegge, Miller, & Olsen, 1999; Tangney, Wagner, Hill-Barlow, Marschall, & Gramzow, 1996). But most research has confounded aggression with other constructs (e.g., anger, hostility) and few have examined mediators of the links between moral emotions and aggression. This article has three goals. First, we examine the relationship of moral emotions to more precisely operationalized measures of verbal and physical aggression in four independent samples. Second, we go beyond self-reports of aggressive behavior by examining observational, parental, and teacher reports of aggression. Third, we extend the literature by evaluating key mediational hypotheses regarding the functional nature of these relationships.

Although shame and guilt are regarded as moral emotions that regulate social behavior, there are important conceptual differences between the two (Lewis, 1971; Tangney, Stuewig, & Mashek, 2007; Tracy & Robins, 2006). Both shame and guilt are “negative” or uncomfortable emotions. Shame, however, involves a negative evaluation of the entire self vis-à-vis social and moral standards. Guilt focuses on specific behaviors (not the self) that are inconsistent with such standards. Further, shame and guilt lead to different “action tendencies” (Lindsay-Hartz 1984). Guilt is apt to motivate reparations. Shame is apt to motivate efforts to hide or disappear.

Research has shown that the propensity to experience shame is associated with a variety of psychological problems including posttraumatic stress disorder, obsessive-compulsiveness, psychoticism, anxiety, and depression (Ferguson, Stegge, Eyre, Vollmer, & Ashbakr, 2000; Orth, Berking, & Burkhardt, 2006; Quiles & Bybee, 1997; Tangney, Wagner, & Gramzow, 1992a). The unique variance in guilt, on the other hand, is typically either unrelated or inversely related to psychological problems (Bybee, Zigler, & Berliner, 1996; Gramzow & Tangney, 1992; Quiles & Bybee, 1997).1 Less work has examined the relationship between the moral emotions and aggression, and typically the extant research has focused not on aggressive behavior, per se, but on related psychological phenomena such as externalization of blame (a cognitive attributional construct), anger (an emotion), hostility (a cognitive-affective attitude) or some combination.

Lewis (1971) first noted that patients’ shame often co-occurred with feelings of humiliated fury. Lewis suggested that unlike its gentler sister guilt, painful feelings of shame can elicit defensiveness, anger, and overt aggression. Essentially, shame-rage or humiliated fury is thought to represent a defensive response to a wounded self. When experiencing shame, people evaluate the self as worthless, defective, and inferior. Feeling powerless and in pain, shamed individuals may become angry, blame others, and aggressively lash out in an attempt to regain a sense of agency and control (Scheff, 1987; Gilligan, 1996; Tangney, 1992; Tangney & Dearing, 2002).

Although often referred to as an empirically established direct relationship, the few studies that address the shame-aggression link often do not distinguish physical aggression from other related constructs, such as problem behavior, anger, hostility, or externalization of blame – constructs that may or may not have a theoretically and empirically justified link to shame. For example, Paulhus, Robins, Trzesniewski, and Tracy, (2004) reported a positive relationship between shame and aggression. Aggression, however, was measured using the total score from the Aggression Questionnaire (Buss & Durkee, 1957) which combines verbal aggression, physical aggression, anger, and hostility. As such it is difficult to distinguish the true nature of the relationship between shame and aggression, specifically.2 Other studies speak indirectly to the possible shame-aggression link, sometimes showing a positive association between shame-proneness and externalizing symptoms (Ferguson, et al., 1999), but in others no direct relationship (Bennett et al., 2005). Again, these findings do not speak to the strict relationship between shame and physical aggression because externalizing symptoms are often measured as a mix of not only verbal and physical aggressive items but delinquent and other more non-specific items (e.g. loud, moody, excess talking, and stubborn).3

In a study of undergraduates, Tangney, Wagner, Fletcher, and Gramzow (1992b) found no relationship between shame-proneness and measures of assault and verbal hostility. Shame-proneness was more clearly (positively) associated with subscales assessing irritability, resentment, and indirect hostility. In a subsequent series of studies, however, Tangney, Wagner, et al., (1996) found positive correlations between shame-proneness and physical aggression in independent samples of adults, adolescents and children, and positive relationships between shame-proneness and verbal aggression for adults, college students, adolescents, and children.

In sum, although some studies found a relationship between shame and aggression others did not. Use of measures that confound aggression with other constructs such as anger and hostility may be muddying the true relationship of shame to aggression. This may be important because withdrawal, a hallmark of shame, is contradictory to approach-oriented behaviors such as physical aggression that tend to draw more attention to the shame-prone individual. Other related constructs such as anger or externalization of blame do not necessarily have to be directly expressed to others, and seem to have more consistent relationships with shame (Bennett et al., 2005; Harper, Austin, Cercone, & Arias, 2005; Tangney, Wagner, et al., 1996). It is possible a narrower operationalization of aggressive behavior may help clarify this relationship.

In contrast to shame, guilt involves negative evaluations of a specific behavior that are not generalized to the core self. Although painful, guilt is not associated with a wounded self and the consequent impulse to lash out at others. Instead “shame-free” guilt can lead individuals to apologize or to make amends (Ketelaar & Au, 2003; Lindsay-Hartz, 1984). As such “shame-free” guilt may serve a protective function against aggression.

Consistent with this notion, empirical studies of children, adolescents, college students, and adults provide clear evidence of a negative relationship between guilt and aggression, broadly (Paulhus, et al., 2004; Ferguson, et al., 1999 for boys but not girls) or more precisely defined (Tangney, Wagner, et al., 1992b, 1996). Regarding shame, findings have been less consistent but on balance suggest a positive link between shame and aggression.

Less clear is why guilt and shame are negatively and positively related to aggression, respectively. A better understanding of cognitive and affective mediators would have important theoretical and applied implications. To date, empirical research has considered simple direct relationships between shame and aggression (and related constructs). Clinical and theoretical accounts, however, typically postulate mechanisms that might mediate this relationship, but few have been tested. Lewis (1971), Scheff (1987), and others suggest shame-prone individuals may shift responsibility to others when their wounded self is attacked. In other words, “I feel so bad” can quickly turn to “how could you make me feel this way?!” This defensive response or tendency to scapegoat others may be reflected in feelings of anger and a tendency to externalize blame that, in turn, leads to verbal and physical aggression.

The link of anger and externalization of blame with antisocial and aggressive behavior is well established (Anderson & Bushman, 2002; Colder & Stice, 1998; Quigley & Tedeschi, 1996; Rothbart, Ahadi, & Hershey, 1994). Aggressive and antisocial individuals often use cognitive distortions to justify their activities (Bandura, Caprara, Barbaranelli, Pastorelli & Regalia, 2001; Henning, Jones & Holdford, 2005; Sykes & Matza, 1957). Externalizing blame onto other people, institutions, and situations is one such strategy. These distortions are not just “after the fact” rationalizations but are beliefs and attitudes that theoretically contribute to antisocial behavior and specifically aggression (Guererra & Slaby, 1990; Maruna & Copes, 2005).

Research consistently shows a positive link between shame-proneness and anger, hostility, and externalization of blame (Bennett et al., 2005; Hoglund & Nicholas, 1995; Tangney, Wagner et al., 1992b; Tangney, Wagner et al., 1996). In one of the few tests of mediation (Harper et al., 2005), male college students’ anger fully mediated the relationship between shame and psychological abuse of a partner. Unclear is whether externalization of blame mediates the relationship between shame and aggression and if this generalizes to non-college samples.

Guilt-prone individuals, on the other hand, should have less need to deflect blame outward, should be more inclined to accept responsibility, and more likely to be empathetic towards others. Research confirms that the propensity to experience “shame-free” guilt is inversely related to anger, hostility, and externalization of blame (Tangney & Dearing, 2002), but it is still an open question if these factors mediate guilt’s relationship with aggression.

Rather than fostering anger and blame, “shame-free” guilt has been consistently linked to other-oriented empathy (Joireman, 2004; Leith & Baumeister, 1998; Tangney & Dearing, 2002). Other-oriented empathy in turn is negatively correlated with a range of antisocial behaviors, including aggression (Jolliffe & Farrington, 2004; Miller & Eisenberg 1988), and, although thus far untested, theory suggests that empathy may mediate the inverse relation of guilt and aggression (Tangney & Dearing, 2002). Conversely, research shows that “guilt-free” shame is generally unrelated to empathic concern, and only occasionally negatively correlated with perspective taking (Joireman, 2004; Tangney, 1991; Tangney & Dearing, 2002).

Although the observed links of shame to externalization of blame and guilt to empathy and externalization of blame are suggestive, to date, no one has conducted a comprehensive test of mediators. The current study extends previous research by moving beyond an examination of direct simple effects, to test a larger multivariate model (see Figure 1). Due to the generally inconsistent relationship between shame and aggression, and the inclusion of cognitive factors in many measures of aggression, we expected that any relationship of shame to aggression would only be indirect through the cognitive construct of externalization of blame (i.e. no direct effect of shame to aggression). Negative feelings of shame should lead to externalization of blame, which in turn should lead to higher levels of verbal and physical aggression. Furthermore, based on prior research, there should be no relationship between shame and other oriented empathy.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model of the relationship between the moral emotions and aggression

Guilt, on the other hand, should be negatively related to externalization of blame and should facilitate empathic processes thus reducing outward directed aggression. In their review of the relationship of shame and guilt to different forms of risky behavior, Stuewig and Tangney (2007) observed that guilt (as compared to shame) was more strongly and consistently related to behaviors of an externalizing nature such as aggression and delinquency. In one study Stuewig and McCloskey (2005) found no relationship between shame and delinquency, but guilt proneness was inversely related to delinquency even controlling for other variables, including conduct disorder symptoms in childhood and parenting in adolescence. As such, there may be both direct and indirect relationships between guilt to aggression.

This hypothesized model (Figure 1) was tested in four independent samples drawn from different populations, using slightly different measures of shame and guilt and both self-reports and other reports of aggression.

Participants and Procedures

Sample 1 was drawn from a study of 250 college students (mean age=20, SD=5.2, range =18–55) examining personality traits and other correlates of forgiveness (Tangney, Boone & Dearing, 2005). Included were paper-and-pencil measures of the constructs of interest to this article (shame, guilt, externalization of blame, empathic concern, perspective taking, verbal and physical aggression). Most participants were female (74%); the sample was diverse with 50.6% Caucasian, 18.6% Asian, 10.9% African American, 6.5% Latino, 5.3% Middle Eastern, and 8.1% “Other.” Students completed questionnaires in three sessions (45–60 minutes each) on separate days. Informed consent forms described the investigation as “a psychological study to learn more about emotions, perceptions, and styles of thinking among normal, young adults.” The voluntary and confidential nature of the study was emphasized.

Sample 2 was from a study of moral emotions of 234 early adolescents (Tangney & Dearing, 2002) (mean age=12.7 years, SD=.61, range=11–14). The sample was 57% female and the racial/ethnic composition was: 64.2% Caucasian, 26.7% African American, 3.5% Asian, 1.7% Latino, and 3.9% “Other.” The sample was initially studied in 1990 (Wave 1), when the index children were in the 5th grade. Children were recruited from 9 public elementary schools in an ethnically and socioeconomically diverse suburb of Washington DC. Letters describing the nature of the study were sent to the parents of all 5th-grade students at participating schools. Only those students for whom we received a signed form granting permission, and who themselves agreed to participate, were included in the study. The data analyzed here are from Wave 2 only, when the children were followed up in the 7th/8th grade. Wave 2 was selected because it contained all measures relevant to the research questions proposed here.

Sample 3 was composed of 507 pre- and post-trial inmates held in a metropolitan area county jail who participated in a larger longitudinal study of moral emotions and criminal recidivism.4 Most (70%) were male; average age was 32 years (SD = 10, range=18–69), and participants varied in race/ethnicity: 44.2% African American, 36.3% Caucasian, 9.1% Latino, 3% Asian, 4.1% “Mixed,” and 3.3% “Other.” Participants were charged with at least one felony; 83% had prior jail experience and 54% had a previous felony conviction. This was largely a sample of serious offenders. Shortly after assignment to the jail’s “general population,” trained research assistants invited eligible inmates to participate in a multi-phase study with assurances of the voluntary and confidential nature of the project. In particular, it was emphasized that the decision to participate or not would have no bearing on their status at the jail nor their release date. Interviews were conducted in the privacy of professional visiting rooms, used by attorneys, or secure classrooms. In addition, we obtained a Certificate of Confidentiality from the Department of Health and Human Services to protect the data. Inmates who completed the 4–6 session intake assessment received a $15–18 honorarium.

Sample 4 was composed of 250 at-risk youth in middle adolescence (mean age = 15, SD = 1.9, range=11–18, 52% female) involved in a longitudinal study of the effect of marital violence on children’s mental health. The ethnic distribution was approximately 41% Anglo-European, 36% Hispanic, 6% African American, 4% Native American, and 13% other. The original sample was composed of abused and non-abused mothers and one of their children (McCloskey, Figueredo, & Koss, 1995). Women from both groups responded to posters and advertisements throughout the community. Abused women were uniquely solicited from battered women’s shelters as well as with targeted posters asking for women who had been abused during the past year. The first year of interviews (Time 1) were completed in 1991 (see McCloskey, et al., 1995 for further details). Participants were re-interviewed 6 years later at which time measures of shame and guilt were collected (Stuewig & McCloskey, 2005). The data used here were from that second time point only. All mothers provided informed consent and children provided written assent prior to participating. Trained interviewers conducted separate face-to-face interviews with mothers and children. Confidentiality was assured, and a Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained.

Measures

Shame, Guilt, and Externalization of Blame

Samples 1, 2, and 3 used different versions of the Test of Self-Conscious Affect (TOSCA); convergent and divergent validity for the TOSCA scales have been documented elsewhere (see Tangney, 1991; Tangney, Wagner, et al., 1992a). Sample 4 used the Adolescent Shame Measure (ASM; Reimer, 1995). Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, and reliabilities.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for the major constructs in each sample

| Construct | Sample | Measure | Mean (SD) | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shame | 1. | TOSCA | 2.8 (.57) | .73 |

| 2. | TOSCA-A | 2.5 (.51) | .76 | |

| 3. | TOSCA-SD | 2.5 (.82) | .59 | |

| 4. | ASM | 2.8 (.69) | .81 | |

| Guilt | 1. | TOSCA | 3.8 (.47) | .70 |

| 2. | TOSCA-A | 3.7 (.58) | .84 | |

| 3. | TOSCA-SD | 4.3 (.53) | .80 | |

| 4. | ASM | 3.7 (.62) | .78 | |

| Externalization of Blame | 1. | TOSCA | 2.5 (.50) | .65 |

| 2. | TOSCA-A | 2.6 (.59) | .82 | |

| 3. | TOSCA-SD | 2.0 (.68) | .82 | |

| 4. | ASM | 2.2 (.54) | .75 | |

| Empathic Concern | 1. | IRI | 4.0 (.61) | .72 |

| 2. | IRI | 3.6 (.69) | .75 | |

| 3. | IRI (modified) | 3.1 (.40) | .69 | |

| 4. | IRI | 3.8 (.72) | .66 | |

| Perspective Taking | 1. | IRI | 3.5 (.64) | .71 |

| 2. | IRI | 3.1 (.63) | .61 | |

| 3. | IRI (modified) | 3.1 (.41) | .70 | |

| Verbal Aggression | 1. | ARI | 2.2 (.82) | .77 |

| 2. | ARI-A | 2.8 (.88) | .81 | |

| 2. | Teacher Report | 3.1 (1.8) | - | |

| 3. | PAI | 11.5 (3.3) | .66 | |

| 3. | Jail Infractions | 1.1 (2.4) | - | |

| Physical Aggression | 1. | ARI | 1.6 (.60) | .71 |

| 2. | ARI-A | 2.5 (.94) | .85 | |

| 2. | Teacher Report | 2.3 (1.5) | - | |

| 3. | PAI | 5.5 (2.4) | .66 | |

| 4. | YCBC | .24 (.41) | .74 | |

| 4. | Buss & Perry | 2.8 (.99) | .75 | |

| 4. | Projective | 1.6 (1.1) | .86 | |

| 4. | CBCL (mom) | .26 (.40) | .81 |

The TOSCA (Tangney, Wagner, & Gramzow, 1989) used for Sample 1 consists of a series of brief scenarios (10 negative and 5 positive), each followed by several associated responses. Aggregating across scenarios, the TOSCA yields indices of shame-proneness, guilt-proneness, and externalization of blame. For example, for the scenario “You are driving down the road and hit a small animal,” the shame response is “You would think: I’m terrible,” the guilt response is “You would probably think it over several times wondering if you could have avoided it,” and the externalization of blame response is “You would think the animal shouldn’t have been on the road.” Participants rate how likely they would be to respond in each manner on a scale of 1 = “not at all likely” to 5 = “very likely.” Thus, it is possible for a respondent to endorse multiple responses (e.g., he/she can endorse shame, guilt, both or neither) to any given scenario.

For Sample 2, we used The Test of Self-Conscious Affect-Adolescent Version (TOSCA-A; Tangney, Wagner, Gavlas & Gramzow, 1991b), which was modeled after the TOSCA using age appropriate scenarios. For the scenario “You trip in the cafeteria and spill your friend’s drink,” the shame response is “I would be thinking that everyone is watching me and laughing,” the guilt response is “I would feel very sorry. I should have watched where I was going,” and the externalization of blame response is “I would think: “I couldn’t help it: The floor was slippery.”

For Sample 3, we used The Test of Self-Conscious Affect for Socially Deviant Populations (TOSCA-SD; Hanson & Tangney, 1996), designed specifically for use with incarcerated individuals and other “socially deviant” populations. The TOSCA-SD is composed of 13 brief scenarios. Among offenders, the shame subscale composed of five negative self-appraisal items appeared to offer the most valid index of shame-proneness (Hanson, 1996), thus the five negative self-appraisal items were used to form the shame scale for the current analyses. For example, for the scenario “You go out on a date with a woman/man and have sex. Afterwards she/he says that she/he felt forced into it,” the shame response is “you would think: ‘I am a disgusting person’,” the guilt response is “You would try to understand what you did to hurt him or her,” and the externalization of blame response is “You would think that she/he really enjoyed it and is just trying to get back at you.” The TOSCA-SD has demonstrated reliability and validity in preliminary studies of prison inmates (Hanson, 1996).

For Sample 4, we used The Adolescent Shame Measure (ASM; Reimer, 1995), which was modeled after the TOSCA-A. Previous studies showed that shame and guilt from the ASM had adequate internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = .77 and .72, respectively) and showed construct validity, in that it was associated in theoretically consistent ways with the TOSCA-A, self-esteem, self-consciousness, and depressed mood among adolescents (Reimer, 1995). The ASM is composed of 13 brief scenarios. An example is “You do your homework carelessly and you get a bad grade,” the shame response is “I would feel like I can’t do anything right,” the guilt response is “I would feel bad that I didn’t work harder,” and the externalization of blame response is “I would feel angry that my teacher is such a hard marker.”

Empathic Concern and Perspective Taking

The Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI; Davis, 1983), a paper-and-pencil measure of cognitively-oriented and emotionally-oriented empathy, was used in all samples. The Empathic Concern Scale assesses the extent to which respondents experience “other-oriented” feelings of compassion and concern (e.g., “I often have tender, concerned feelings for people less fortunate than me”). The Perspective Taking Scale assesses the ability to “step outside of the self” and take another’s perspective (e.g., “Before criticizing somebody, I try to imagine how I would feel if I were in their place”). Davis (1980, 1983; Davis & Oathout, 1987) has provided evidence supporting the reliability and validity of his measure. In Samples 1 and 2 empathic concern and perspective taking were measured on a 5-point scale; in Sample 3 a 4- point scale was used. In Sample 4 a 5-point scale was used and only the Empathic Concern Scale was administered.

Verbal and Physical Aggression (Self-Report)

For Sample 1, we used The Anger Response Inventory (ARI; Tangney, Wagner, Marschall, & Gramzow, 1991), a scenario-based self-report measure that is composed of common situations likely to elicit anger. Aggregating across different scenarios, the ARI yields indices specific to verbal and physical aggression. Individuals are asked to imagine themselves in each situation and rate on a 5-point scale from 1=“not likely” to 5=“very likely” whether they would actually engage in a specified action. Verbal aggression responses include verbal confrontation such as yelling or screaming at a person. Physical aggression responses address physical contact such as hitting or pushing a person. Several independent studies provide support for the reliability and validity of the ARI (Tangney, Hill-Barlow, et al., 1996; Tangney, Wagner, et al., 1996).

For Sample 2, we used The Anger Response Inventory-Adolescent Version (ARI-A; Tangney, Wagner, Gavlas, & Gramzow, 1991a) a modified version of the adult ARI with age-appropriate scenarios and responses that yield subscales including verbal and physical aggression.

For Sample 3, we used a modified version of the verbal and physical aggression subscales of The Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI; Morey, 1991). To avoid confounding aggression with cognitive-affective constructs such as temper, hostility, or anger, items that did not explicitly assess verbal or physical aggression were dropped (for example, “People are afraid of my temper.”). This resulted in a five item verbal aggression scale (e.g. I’m not afraid to yell at someone to get my point across) and a three item physical aggression scale (e.g. Sometimes I’m very violent); each item was rated on a 4-point scale then summed.

For Sample 4, we did not have a measure of verbal aggression. To create a robust assessment of physical aggression, we used three separate scales of aggression as indicators for a latent construct of physical aggression in the path model:

Youth Child Behavior Checklist (YCBC; Achenbach, 1991b)

As with the Sample 3 PAI, we chose a subset of items that explicitly measured physical aggression: “I get in many fights,” “I physically attack people,” “I threaten to hurt people,” and excluded more ambiguous items (e.g. I show off or clown around). Responses were rated on a 3 point scale from 0 to 2.

The Physical Aggression Scale (Buss & Perry, 1992) contains the items “Once in a while I can’t control the urge to strike another person,” “Given enough reason, I may hit another person,” and “If somebody hits me, I hit back.” Responses ranged from 1= “extremely unlike me” to 5 = “extremely like me”.

Projective Measure of Aggression (McCloskey & Stuewig, 1996), composed of six scenarios, tests how quickly a subject would resort to physical violence in an escalating conflictual situation. Situations ranged from dirty looks to sexual jealousy. Scenarios for boys and girls were the same except worded so that all aggression was directed against a same sex peer.

An interviewer read each scenario, for example “You are waiting for friends outside a fast food restaurant and you put your pager down on the bench to pick up your drink. When you turn around you see a girl putting your pager into her pocket. When you go over and confront her she denies taking it. What would you do?” If the subject did not spontaneously report physical violence (participants often stated they would say “well I saw you take it, now give it back”), interviewers asked a series of scripted probes. First they asked “what if she refused to return it and called you a name?” If the subject did not indicate he or she would use physical violence, the interviewer next probed “what if she refused to return it and told you to get lost or else?” If still no physical violence was reported, interviewers asked a final question, “what if she then shoved you?” Each scenario was coded to capture with how little provocation the subject responded to with physical violence. Responses were coded 0=“never responded with violence” to 4=“responded with physical violence immediately.” An exploratory factor analysis of the 6 items indicated a single factor that explained 62% of the variance (eigenvalue=3.7, next highest eigenvalue=.79 explaining only 13%). All items loaded on this one factor at at least .45.

Verbal and Physical Aggression (Behavioral, Parent, and Teacher Report)

To supplement self-reports of aggression we examined teacher reports of aggression for Sample 2, disciplinary infractions while in jail for Sample 3 (which occurred after initial interview), and maternal reports of aggression for Sample 4. These non self-report measures of aggression (and for Sample 3 also longitudinal) were substituted for self-reports in a second series of analyses testing the theoretical model.

For Sample 2, middle school teachers (the teacher identified by schools as having the most contact with each student – typically the homeroom teacher) completed a measure that loosely parallels constructs assessed by the ARI-Adolescent Version. Teachers were asked to “please think back to the times when you have seen this student angry, then rate how typical each of the following responses are for this student.” Verbal aggression was measured with one item (“tends to lash out verbally at someone else when angry”) and physical aggression was measured with one item (“tends to strike out physically at the person he or she is angry with”), each rated on a 7 point scale where 1 = “not at all like” to 7 = “very much like.” Teachers’ reports were available for 163 of the 234 adolescents. (Teacher data were only available from students who remained in the public school system. A substantial number of students in these communities transferred to private schools when transitioning to middle school.)

For Sample 3, we collected and coded deputies’ reports of 460 inmates’ jail infractions. Jail infractions were coded into four categories: (1) physical aggression (7.6% of the sample were cited for a physical violation such as fighting, assaulting another inmate, assaulting employee or visitor); (2) verbal aggression (5.7% were cited for verbal violations such as threatening bodily harm, cursing and abusing an employee or visitor); (3) defiant behavior (27.2%, such as refusing to obey a direct order, interfering with an employee in the performance of duties, vandalism, having contraband); and (4) other (4.3%, such as kicking or banging on doors, excessive horseplay). Although physical infractions would have fit the conceptual focus of this paper best, there were so few of these (7.6% of the sample) that we decided to use the number of any infractions incurred by the participant while incarcerated (range = 0 to 23).

For Sample 4, interviewers administered the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991a) to mothers. We chose 4 items that measured physical aggression: “cruelty, bullying, or meanness to others,” “gets in many fights,” “physically attacks people,” and “threatens people.” Due to the skewed nature of the variable (skewness=1.8), a square root transformation was performed prior to analyses (M = .33, SD = .39, skewness=.72 for transformed variable). Mother’s report was available for 246 of the adolescents.

Results

Zero Order Correlations

Across samples, shame was generally positively correlated with externalization of blame, empathic concern, and perspective taking (Table 2). Guilt was generally negatively correlated with externalization of blame and positively correlated with both types of empathy. When examining aggression (Tables 2 and 4), shame was sometimes positively related (one correlation), sometimes negatively related (six correlations), and sometimes unrelated (six correlations) to the different reports of aggression. Guilt, on the other hand, was significantly negatively correlated with both verbal and physical aggression in eleven of the correlations (the other two were non-significant but negative in sign).

Table 2.

Zero-Order correlations of all self-report variables

| Sample | Shame | Guilt | Ext. of Blame | Empathic Concern | Persp. Taking | Verbal Agg | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guilt | 1. | .46* | |||||

| 2. | .38* | ||||||

| 3. | .24* | ||||||

| 4. | .64* | ||||||

| Ext. | 1. | .36* | .07 | ||||

| 2. | .30* | −.30* | |||||

| 3. | .12* | −.42* | |||||

| 4. | .11 | −.22* | |||||

| EC | 1. | .13* | .34* | −.13* | |||

| 2. | .23* | .54* | −.22* | ||||

| 3. | .17* | .45* | −.37* | ||||

| 4. | .43* | .54* | −.23* | ||||

| PT | 1. | −.01 | .22* | −.11 | .43* | ||

| 2. | .18* | .44* | −.21* | .48* | |||

| 3. | .12* | .42* | −.16* | .50* | |||

| Verb Agg. | 1. | −.01 | −.28* | .28* | −.38* | −.33* | |

| 2. | .25* | −.09 | .41* | −.10* | −.17* | ||

| 3. | −.12* | −.32* | .27* | −.26* | −.25* | ||

| Phys. Agg. | 1. | .06 | −.27* | .30* | −.30* | −.19* | .62* |

| 2. | .01 | −.33* | .41* | −.34* | −.27* | .68* | |

| 3. | −.07 | −.33* | .31* | −.24* | −.19* | .54* | |

| 4.a | −.16* | −.33* | .36* | −.32* | -- | -- | |

| −.28* | −.38* | .32* | −.26* | -- | -- | ||

| −.19* | −.34* | .24* | −.16* | -- | -- |

p<.05

There were 3 separate measures of physical aggression for Sample 4 (Buss & Perry’s Physical Aggression Scale, The Projective Scale, YCBC)

Table 4.

Correlations of self-report variables to behavioral and other reports

| Sample 2 | Sample 3 | Sample 4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teacher Report | Jail Records | Mother Report | ||

| Verbal Agg | Phys Agg | Jail Infractions | Phys Agga | |

| Shame | −.05 | −.18* | −.04 | −.14* |

| Shame Residual | .04 | −.09 | −.04 | −.02 |

| Guilt | −.21** | −.22** | −.01 | −.19** |

| Guilt Residual | −.21** | −.18* | .00 | −.13* |

| Ext of Blame | .18* | .09 | .02 | .06 |

| Empathic Concern | −.09 | −.12 | −.03 | −.16* |

| Perspective Taking | −.11 | −.11 | .10* | -- |

| Verbal Aggression | .02 | −.10 | .08 | -- |

| Physical Aggressionb | .27** | .26** | .14* | .26** |

| .28** | ||||

| .31** | ||||

p<.05,

p<.01

Mother’s report of aggression was transformed using a square root transformation

There were 3 separate measures of self-report of physical aggression for Sample 4 (Buss & Perry’s Physical Aggression Scale, The Projective Scale, YCBC)

Correlations with “Guilt-Free” Shame and “Shame-Free” Guilt

Because shame and guilt are both negative self-evaluative emotions they are positively correlated, on average about .4; yet, theoretically, the important features of each should be most evident when the effects of the other have been partialled out (see footnote 1). Such an approach untangles opposing influences that, at the bivariate level, suppress detection of lawful, clinically informative relationships in a more complex space (Paulhus, et al., 2004; Tangney & Dearing, 2002; however, see Lynam, Hoyle, & Newman, 2006, on possible pitfalls of partialling). To model this important unique variance, we conducted semi-partial correlations to examine the correlates of “shame-free” guilt and “guilt-free” shame.

As seen in Tables 3 and 4, when using these semi-partial correlations the results for shame and guilt diverge even more. Shame, independent of guilt, remained positively correlated with externalization of blame and now became generally uncorrelated with empathy. When considering the shame to aggression link using the shame residuals, eight correlations were positive (four significantly) and five negative (none were significant). “Shame-free” guilt, on the other hand, remained negatively correlated with aggression and externalization of blame and positively correlated to empathic concern and perspective taking.

Table 3.

Semi-partial correlations of shame and guilt to self-report variables

| Sample | Shame Residual | Guilt Residual | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Externalization of Blame | 1. | .37** | −.11 |

| 2. | .46** | −.45** | |

| 3. | .22** | −.46** | |

| 4. | .33** | −.38** | |

| Empathic Concern | 1. | −.03 | .32** |

| 2. | .01 | .50** | |

| 3. | .07 | .42** | |

| 4. | .11 | .34** | |

| Perspective Taking | 1. | −.13* | .26** |

| 2. | −.01 | .41** | |

| 3. | .03 | .40** | |

| Verbal Aggression | 1. | .13* | −.31** |

| 2. | .31** | −.20** | |

| 3. | −.05 | −.30** | |

| Physical aggression | 1. | .20** | −.33** |

| 2. | .15* | −.36** | |

| 3. | .01 | −.32** | |

| 4.a | .07 | −.30** | |

| −.04 | −.27** | ||

| .04 | −.29** |

There were 3 separate measures of physical aggression for Sample 4 (Buss & Perry’s Physical Aggression Scale, The Projective Scale, YCBC)

Note. Semi-partial correlations reflect the unique amount of variance explained by shame or guilt when controlling for the other (i.e. the guilt residual reflects “shame-free” guilt).

p<.05,

p<.01

Path Analyses

Covariance matrices were imported and analyzed in Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 2004) using Maximum Likelihood estimation. We hypothesized that any relationship between shame and aggression would be indirect through externalization of blame, whereas the relationship between guilt and aggression would be partially mediated by empathy and externalization of blame. Thus we fixed the direct paths between shame and empathic concern, shame and perspective taking, and shame and physical and verbal aggression to zero. All other parameters were freely estimated.

The estimated model fit the data in all four samples using self-reports of aggression (see Figure 2).5 Because we were especially interested in the shame to aggression link, we ran a second model in each sample allowing the direct paths from shame to aggression to be freely estimated and then examined the chi-square difference test between the two models. For Samples 1, 3, and 4 the chi-square difference was test was non-significant (X2(2)=3.4; X2(2)=3.9; X2(1)=1.4; all ps > .05). For Sample 2, there was a significant improvement in fit (X2(2)=9.1, p<.05). Here, the direct pathway from shame to verbal aggression was positive and significant (β = .17, p <.05), but there was no relationship from shame to physical aggression (β = .00, p >.05). In each of the 4 samples, the indirect effects did not substantially change when the direct paths from shame to verbal and physical aggression were freed. These results generally suggest that we should accept the more parsimonious a priori model where the shame to aggression link was set to zero.

Figure 2.

Model of significant paths (p < .05) for each sample using self-reports of aggression

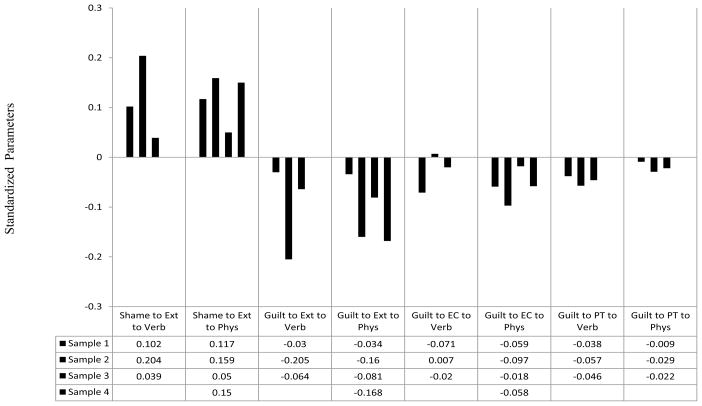

Significant pathways are shown in Figure 2, while strength of direct and indirect pathways are shown in Figures 3 and 4 respectively. As shown, the higher the shame the higher the externalization of blame, which in turn was related to higher levels of both verbal and physical aggression. Indirect effects were tested in Mplus. The indirect path from shame to verbal aggression through externalization of blame was statistically significant for each sample. The indirect path from shame to physical aggression through externalization of blame was also significant for each sample. In other words, the relationship between shame and aggression was only indirect through externalization of blame; individuals high in shame-proneness were more likely to blame others leading to a greater propensity for verbal and physical aggression.

Figure 3.

Standardized parameter estimates for the model’s direct effects from all four samples using self-reports of aggression.

Figure 4.

Standardized parameter estimates for the model’s indirect effects from all four samples using self-reports of aggression.

Guilt was significantly negatively related to externalization of blame in three samples (see Figures 2 and 3) and showed a trend in the other (p=.074). Guilt was positively related to both empathic concern and perspective taking in all samples. Empathic concern and perspective taking were generally negatively related to both types of aggression although these effects were smaller and not consistently significant (Figures 2 and 3). In fact, perspective taking was not statistically significantly related to physical aggression in any of the samples. Additionally, guilt continued to show a direct effect to both verbal and physical aggression, where those high in guilt were less likely to exhibit aggressive behaviors.

Overall, the indirect relationship of guilt to aggression through externalization of blame and empathy was negative (Figure 4). There were significant indirect effects of guilt to verbal aggression through externalization of blame for Samples 2 and 3, through empathic concern for Sample 1, and through perspective taking for Samples 1 and 3, with a trend for Sample 2. There were also significant indirect effects of guilt to physical aggression through externalization of blame for Samples 2, 3, and 4 and through empathic concern for Samples 1 and 2. Generally, individuals high in guilt-proneness showed lower levels of externalization of blame that, in turn, was related to lower levels of aggression. In conjunction, individuals high in guilt-proneness showed higher levels of empathy that in turn was related to lower levels of aggression.

Beyond Self-Reports: Behavioral, Parent, and Teacher Reports of Aggression

The findings from all four samples have two significant limitations. First, all measures were self-report. While self-report is important and, when measuring certain low base-rate constructs such as aggression, may give the most accurate picture of such behavior, it can also be criticized (e.g., method variance, measure of what people feel or how they see themselves, not what they do). Second, all analyses used a cross-sectional design. In order to address these limitations teacher reports of aggression, disciplinary infractions while in jail, and maternal reports of aggression were substituted for self-reports in Samples 2, 3, and 4, and the models were then rerun in each sample (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Model of significant paths (p < .08) for each sample using behavioral or other reports of aggression.

Correlations of the teacher, behavioral, and mother reports of aggression with the self-reports of aggression are presented in Table 4. As in other multi-informant studies of aggression (Achenbach, McConaughy, and Howell, 1987), teachers’ reports of verbal and physical aggression were only moderately correlated with self-reports of physical aggression (.27 and .26) and neither was related to self-reports of verbal aggression. Similarly, jail infractions and maternal reports also showed a small to moderate correlation with self-reports.

For Sample 2, to test the full model we used Mplus’s full information maximum likelihood estimation in order to take advantage of the full sample of 234 adolescents. The estimated model using teacher reports of aggression fit the data well (X2(4)=3.7, p=.44, CFI=1.0, RMSEA=.00, SRMR=.02). As can be seen in Figure 5, externalization of blame was not related to teachers’ reports of physical aggression but was marginally positively related to teachers’ reports of verbal aggression (β = .14, p = .065). There was also evidence of a marginally significant indirect effect of shame to verbal aggression through externalization of blame (β = .07, p = .072). No indirect effect was found for physical aggression. In addition, guilt showed a significantly negative direct effect to teachers’ reports of both verbal (β = −.19, p < .05) and physical (β = −.21, p < .05) aggression, as well as a marginally significant indirect effect to verbal aggression through externalization of blame (β = −.07, p = .072). Neither empathic concern nor perspective taking was related to teachers’ reports of adolescents’ aggression.

Since number of jail infraction in Sample 3 is a count variable with a significantly skewed distribution (70% had no infractions), we ran a negative binomial model using maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors. Additionally, we included the log of number of days incarcerated as an offset variable in order to adjust for differing amounts of time spent in jail. The chi-square statistic and other fit indices cannot be computed using this type of estimation technique, however, the significance of pathways can be evaluated. Only guilt and perspective taking showed a relationship to jail infractions. Those higher in guilt-proneness tended to commit fewer jail infractions (β = −.17, p = .078). Contrary to expectations perspective taking was positively related to number of jail infractions (β = .37, p < .05).

For Sample 4, we ran the model on all 250 adolescents using full information maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors. The model showed a good fit to the data (X2(2)=4.5, p=.10, CFI=.98, RMSEA=.07, SRMR=.03). Similar to the other models, the higher the guilt the lower the physical aggression (β = −.14, p < .05). None of the other variables were significantly related to aggression and there were no significant indirect effects.

Discussion

To date, research on the relationship between the moral emotions and aggression has typically employed measures that confound aggression with related cognitive and affective constructs, i.e. anger and hostility. Additionally, there is little research on potential mediators between the moral emotions and aggression. In this article we examined the relationship of moral emotions to more precisely defined measures of verbal and physical aggression in multiple data sets, varying in age and other demographics, and evaluated several potential cognitive and affective mediators suggested by theory. Overall the hypothesized model (see Figure 1) fit the four distinct data sets well.

Although a great deal of data were presented in this article, we believe much of it can be boiled down to five main points. (1) Models were consistent in showing no direct relationship between shame and aggression. (2) Models were consistent in showing no direct relationship between shame and a deficit in other-oriented empathy. (3) There was evidence for an indirect relationship between shame and aggression through externalization of blame, but mostly when aggression was measured using self-report. (4) There was consistent evidence that guilt is directly related to low levels of aggression, whether using self-report or other reports of aggression. (5) There was evidence of an indirect relationship between guilt and aggression through externalization of blame and empathy, but mostly when aggression was measured using self-report. The heterogeneity of the different samples and similarity of findings lend weight to the robustness of these results.

Shame

Although often assumed, the link between shame and aggressive behavior has not been studied extensively. In four independent studies, we found little evidence that shame-proneness plays a direct inhibitory role on aggression. In fact, path analyses testing the full model were consistent with the hypothesis of no direct relationship between shame-proneness and physical or verbal aggression. Rather, when there was a relationship, it was indirect through externalization of blame. Shame-proneness individuals exhibited elevated levels of externalization of blame that, in turn, was related to self-reported physical and verbal aggression.

The propensity to shift responsibility and react defensively converges with clinical and theoretical descriptions of how shame may be transformed into maladaptive responses, such as hostility, anger and sometimes aggression (Lewis, 1971; Scheff, 1987). A cognitive style of blaming may also be an important mechanism that helps account for the descriptions of bypassed, unresolved, or unacknowledged shame discussed in the literature (Harris, 2006; Lewis, 1995; Scheff, 1987). We do not know, however, if this shifting of blame then helps individuals regulate their feelings of shame and/or how quickly this process might happen. Additionally, this cognitive style of externalizing blame may work with other cognitive-affective tendencies in leading to aggression. Tedeschi and Nesler (1993) suggested that while blame may precede anger, it is also possible that anger and blame work together leading to fury (Quigley & Tedeschi, 1996). Similarly, other cognitive styles or attributional biases may play a role. It is possible that these other constructs interact with each other and it is in those situations that shame may have the strongest influence on aggression. For example, while shame-prone individuals may be more likely to blame others, it is only when situational anger is added to the mix that there may be eruptions into aggression and violence.

Guilt

The direct relationship of guilt to aggression was consistent and robust. This finding was true for self-reports, teacher-reports, mother-reports, and jail infractions. Guilt also influenced self-reports of physical and verbal aggression indirectly through externalization of blame. Individuals high in guilt-proneness exhibited lower levels of externalization of blame that, in turn, were associated with less aggression. There was also evidence of an indirect link between guilt and self-reports of aggression through empathy, where guilt-prone individuals displayed more empathy, which related to lower levels of aggression.

These two indirect pathways for guilt (through externalization of blame and through empathy) are especially noteworthy because the model tested was also consistent with the hypothesis of no relationship between shame-proneness and either form of other oriented empathy. So while the differential effects of shame and guilt may travel through externalization of blame, the path through empathy is unique to guilt.

It is possible that the guilt-empathy link is partially due to higher levels of self-reflection on the part of guilt-prone individuals. Self-reflection (as opposed to self-rumination which characterizes shame-prone individuals) is generally considered a positive characteristic. Those high in self-reflection may think more about what they did and why they did it in a curious fashion rather than being motivated by distress and obsessing over the behavior and themselves (Trapnell & Campbell, 1999). Joireman (2004) found that self-reflection partially mediated the relationship of guilt to perspective taking but not to empathic concern. This tendency toward not only thinking about one’s own feelings but also other people’s thoughts and feelings may play a role in inhibiting aggression (Leith & Baumeister, 1998).

Behavioral, Parent, and Teacher Reports

Interpreting the paths of shame and guilt to aggression through externalization of blame and empathy must be tempered by the fact that these indirect effects held only for self-reports of aggression. In the full models (Figure 5) externalization of blame showed only one marginally significant path toward aggression (teacher reports of verbal aggression). Empathic concern was unrelated to other reports of aggression and the only relationship for perspective taking was contrary to expectation in that, among jail inmates, those reporting higher levels of perspective taking were more likely to be written up for a jail infraction.6

The modest correlations between self-reports and other reports of aggression are common in the literature (Achenbach, et al., 1987). These low correlations may reflect differences in situation or context (e.g. behavior in a school may be different from behavior at home). Or the low concordance may reflect differences in perspectives (self versus other, teacher versus deputy, etc). Investigating and trying to parse out the differences in these perspectives would be informative (Kraemer, et al., 2003). Perhaps some of the relationships among shame, externalization of blame and aggression has more to do with self-perception than actual behavior. Then again, it might be that the type of aggression that is affected by shame or externalization of blame is not seen by others. Individuals who externalize blame may see themselves as aggressors but they may act this way less often in view of others. Here, moderators may play an important role. For example, in certain situations (e.g. high anger arousal), or for certain individuals (e.g. low ability to regulate emotion), aggressive behavior in the view of others may emerge. Examining these moderating relationships at the situational level and the dispositional level, and across levels, may be especially fruitful. Given these possible sources of variance, the consistent negative relationship between guilt and aggression is especially impressive.

Limitations and Future Directions

Although some longitudinal data were considered (Sample 3), it is important to replicate these findings in additional longitudinal studies. In addition, models should be tested that take into account other individual difference variables, in order to rule out alternative hypotheses. For example, self-esteem has been shown to be concurrently and prospectively negatively related to aggression and other externalizing behaviors (Donnellan, Trzesniewski, Robins, Moffitt, & Caspi, 2005). We believe, however, that these results will generally hold up because although shame and self-esteem are moderately negatively correlated, the relationship of self-esteem and guilt is generally small (Tangney & Dearing, 2002).

Another limitation is that the measures of shame and guilt were dispositional measures. When describing shame-fury episodes, most clinical accounts describe “in the moment” situations. Although we believe that dispositional effects reflect processes at the state level, using diary methods, experiential sampling methods, or experimental designs to examine how shame and guilt relate to aggression in the moment would be a useful and important avenue to explore.

In this article, we made sharp theoretical and empirical distinctions between internally experienced emotions and cognitions on one hand, and behavior, on the other. We also distinguished between verbal and physical aggression, but other distinctions (e.g., indirect vs. direct, covert vs. overt, reactive vs. proactive) may make theoretical sense when investigating the correlates of these self-conscious emotions. Furthermore, aggregate measures of aggression may not be the best reflection of the true shame and aggression relationship. Shame-prone individuals may be more vulnerable to infrequent yet explosive incidences of aggression as opposed to chronic levels of aggressive behavior.

Clinical Implications

Identifying the differing relationships between the moral emotions (shame, guilt) and behavior (aggression) can help clinicians better serve their clients’ needs by providing a deeper understanding of the role these emotions play in various outcomes. Empirically identified mediators offer clearer points of intervention for aggression reduction programs. Specifically, the results suggest different points of intervention for people with aggressive problems stemming from maladaptive shame, as opposed to an impaired capacity for guilt. A promising avenue of intervention may be to focus on clients’ causal attributions in the face of failure or transgression. To the extent that individuals are more able and willing to take responsibility and avoid blaming others, they are less likely to engage in aggressive behavior. Many interventions designed to reduce aggression focus on empathy training (e.g., via induction procedures). The data here also suggest that such interventions may be helpful in marshalling the adaptive potential of guilt. However, guilt in and of itself still continued to be related to aggression, suggesting there are other possible points of intervention to be investigated.

Conclusions

Shame and guilt show distinct relationships to aggression, not only in sign, but via somewhat different affective and cognitive mediators. Any positive relationship of shame-proneness to aggression flowed through the inclination to attribute one’s failures and misdeeds to external causes, whereas guilt-proneness was negatively related to aggression both directly and indirectly through the capacity for empathy and an inclination to accept responsibility for failures.

When describing the correlates of shame, extant articles (including some of our previous work) cite aggression as an empirical fact. Theoretical work, too, often refers to a direct link between shame and aggression. A key conclusion from the current paper is that the relationship between shame and aggression is not so straightforward. By distinguishing aggression from other related constructs, we have set forth a more thorough model. We hope these findings will encourage individuals to devise more specific hypotheses, operationalizations, and links to further our knowledge about the dynamic relationship between the moral emotions and aggression. And we hope the current findings and subsequent follow-up research will suggest specific points of intervention with aggressive individuals.

Even with several limitations, the main findings were replicable across diverse samples that differed in a number of demographics and life circumstances. The dual mediational pathways modeled extend the literature on self-conscious emotions and aggression, identifying malleable cognitive and affective processes consistent with clinical observation and theoretically driven a priori hypotheses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 0096950, by the John Templeton Foundation, and by the National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant No. RO1-DA14694 awarded to June Tangney, and by the National Institute of Mental Health grant No. RO1-MH51428 awarded to Laura McCloskey.

Footnotes

Shame and guilt are moderately positively correlated, reflecting the fact that both are negative, self-conscious emotions that can co-occur. Of theoretical and applied importance is the capacity to feel guilt about a behavior without engaging in shame-steeped overgeneralizations to a flawed or inferior self. To measure “shame-free” guilt and “guilt-free” shame it is common to conduct semi-partial (also known as part) correlations.

In fairness, Paulhus et al.’s focus was not on aggression, but on methodological issues associated with suppressor effects relevant to the shame/guilt distinction. Nonetheless once a label (aggression) is paired with a correlation or beta weight in print, countless other papers may refer to this finding. Similarly, aggression was not the focal construct in a number of other studies cited in our review.

Because many of these non-specific items included in aggression measures are more common, they can contribute disproportionately to the variance in measures of “aggression.”

Because an aim of the larger project was to evaluate short-term interventions, selection criteria targeted inmates likely to serve at least 4 months. Eligible inmates were (1) either (a) sentenced to a term of 4 months or more, or (b) held on at least 1 felony charge other than probation violation, with no bond, or greater than $7,000 bond, (2) assigned to the jail’s medium and maximum security “general population” (e.g., not in solitary confinement owing to safety issues, not in a forensics unit for actively psychotic inmates), and (3) sufficiently proficient in English or Spanish to complete questionnaires (for more detail see Stuewig, Tangney, Mashek, Forkner, & Dearing, 2009; Tangney, Mashek, & Stuewig 2007).

Although the chi-square was significant in Sample 4 the measures of approximate fit (CFI, RMSEA, SRMR) were adequate. Nonetheless, we conducted post-hoc analyses testing three separate models substituting each measure of aggression for the latent construct. Analyses suggested that once the other variables were taken into account, there was some negative residual relationship between shame and the scenario measure of aggression. The full results of these analyses are available from the first author.

This unexpected finding may have to do with the unique characteristics of an incarcerated sample; jails have a higher percentage of psychopaths (15–25%) than community samples (1%) (Hare, 1993). Psychopathic inmates may score higher on perspective taking because they have learned to read how other people feel (Rice, Harris, & Cormier, 1992), but this skill is used to better manipulate others or to be generally disruptive. Although an intriguing finding worthy of future study, we do not think too much should be read into it based on one sample. It was largely influenced by three outliers; when these cases were dropped, the perspective taking to jail infractions link remained positive but was non-significant.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Jeffrey Stuewig, Department of Psychology, George Mason University.

June P. Tangney, Department of Psychology, George Mason University

Caron Heigel, Department of Psychology, George Mason University.

Laura Harty, Department of Psychology, George Mason University.

Laura McCloskey, Department of Public Health, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

References

- Achenbach T. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist and 1991 Profile. Burlington: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1991a. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach T. Manual for the Youth Self-Report and 1991 Profile. Burlington: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1991b. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach T, McConaughy SH, Howell CT. Child/adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: Implications of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity. Psychological Bulletin. 1987;101(2):213–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson C, Bushman B. Human Aggression. Annual Review of Psychology. 2002;53(1):27–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A, Caprara GV, Barbaranelli C, Pastorelli C, Regalia C. Sociocognitive self-regulatory mechanisms governing transgressive behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;80(1):125–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DS, Sullivan MW, Lewis M. Young children’s adjustment as a function of maltreatment, shame, and anger. Child Maltreatment. 2005;10(4):311–323. doi: 10.1177/1077559505278619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss A, Durkee A. An inventory for assessing different kinds of hostility. Journal of Consulting Psychology. 1957;21(4):343–349. doi: 10.1037/h0046900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss A, Perry M. The Aggression Questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;63(3):452–459. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.63.3.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bybee J, Zigler E, Berliner D. Guilt, guilt-evoking events, depression, and eating disorders. Current Psychology: Developmental, Learning, Personality, Social. 1996;15:113–127. [Google Scholar]

- Colder C, Stice E. A longitudinal study of the interactive effects of impulsivity and anger on adolescent problem behavior. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1998;27(3):255–274. [Google Scholar]

- Davis MH. A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. JSAS Catalog of Selected Documents in Psychology. 1980;10:85. [Google Scholar]

- Davis MH. Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1983;44:113–126. [Google Scholar]

- Davis M, Oathout H. Maintenance of satisfaction in romantic relationships: Empathy and relational competence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;53(2):397–410. [Google Scholar]

- Donnellan MB, Trzesniewski KH, Robins RW, Moffitt TE, Caspi A. Low self-esteem is related to aggression, antisocial behavior, and delinquency. Psychological Science. 2005;16(4):328–335. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.01535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson TJ, Stegge H, Eyre HI, Vollmer R, Ashbakr M. Context effects and the (mal)adaptive nature of guilt and shame in children. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs. 2000;126:319–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson T, Stegge H, Miller E, Olsen M. Guilt, shame, and symptoms in children. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35(2):347–357. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.2.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan J. Exploring shame in special settings: A psychotherapeutic study. In: Cordess C, Cox M, editors. Forensic psychotherapy: Crime, psychodynamics and the offender patient, Vol. 2: Mainly practice. London, England: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, Ltd; 1996. pp. 475–489. [Google Scholar]

- Gramzow R, Tangney J. Proneness to shame and the narcissistic personality. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1992;18(3):369–376. [Google Scholar]

- Guererra N, Slaby R. Cognitive mediators of aggression in adolescent offenders: II. Intervention. Developmental Psychology. 1990;26(2):269–277. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson RK. Coping with Culpability. Presentation at the 15th Annual Research and Treatment Conference of the Association for the Treatment of Sexual Abusers; Chicago. 1996. Nov, [Google Scholar]

- Hanson RK, Tangney JP. Corrections Research. Department of the Solicitor General of Canada; Ottawa: 1996. The Test of Self-Conscious Affect—Socially Deviant Populations (TOSCA-SD) [Google Scholar]

- Hare RD. Without conscience: The disturbing world of the psychopaths among us. New York: The Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Harper FWK, Austin AG, Cercone JJ, Arias I. The Role of Shame, Anger, and Affect Regulation in Men’s Perpetration of Psychological Abuse in Dating Relationships. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2005;20:1648–1662. doi: 10.1177/0886260505278717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris N. Reintegrative shaming, shame, and criminal justice. Journal of Social Issues. 2006;62:327–346. [Google Scholar]

- Henning K, Jones A, Holdford R. ‘I didn’t do it, but if I did I had a good reason’: Minimization, Denial, and Attributions of Blame Among Male and Female Domestic Violence Offenders. Journal of Family Violence. 2005;20(3):131–139. [Google Scholar]

- Hoglund C, Nicholas K. Shame, guilt, and anger in college students exposed to abusive family environments. Journal of Family Violence. 1995;10(2):141–157. [Google Scholar]

- Joireman J. Empathy and the self-absorption paradox II: Self-rumination and self-reflection as mediators between shame, guilt, and empathy. Self and Identity. 2004;3(3):225–238. [Google Scholar]

- Jolliffe D, Farrington D. Empathy and offending: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2004;9(5):441–476. [Google Scholar]

- Ketelaar T, Au W. The effects of feelings of guilt on the behaviour of uncooperative individuals in repeated social bargaining games: An affect-as-information interpretation of the role of emotion in social interaction. Cognition & Emotion. 2003;17(3):429–453. doi: 10.1080/02699930143000662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Measelle JR, Ablow JC, Essex MJ, Boyce WT, Kupfer DJ. A new approach to integrating data from multiple informants in psychiatric assessment and research: Mixing and matching contexts and perspectives. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160(9):1566–1577. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.9.1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leith K, Baumeister R. Empathy, shame, guilt, and narratives of interpersonal conflicts: Guilt-prone people are better at perspective taking. Journal of Personality. 1998;66(1):1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis HB. Shame and guilt in neurosis. New York: International Universities Press; 1971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M. Shame: the exposed self. New York: Free Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay-Hartz J. Contrasting experiences of shame and guilt. American Behavioral Scientist. 1984;27(6):689–704. [Google Scholar]

- Lynam DR, Hoyle RH, Newman JP. The perils of partialling: Cautionary tales from aggression and psychopathy. Assessment. 2006;13(3):328–341. doi: 10.1177/1073191106290562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruna S, Copes H. What Have We Learned from Five Decades of Neutralization Research. Crime and Justice. 2005;32:221–320. [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey LA, Figueredo A, Koss M. The effects of systemic family violence on children’s mental health. Child Development. 1995;66(5):1239–1261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey LA, Stuewig J. Projective Aggressive Social Scenarios. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Miller P, Eisenberg N. The relation of empathy to aggressive and externalizing/antisocial behavior. Psychological Bulletin. 1988;103(3):324–344. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey LC. The Personality Assessment Inventory Professional Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. Third Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2004. [Google Scholar]

- Orth U, Berking M, Burkhardt S. Self-Conscious Emotions and Depression: Rumination Explains Why Shame But Not Guilt is Maladaptive. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2006;32(12):1608–1619. doi: 10.1177/0146167206292958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulhus D, Robins R, Trzesniewski K, Tracy J. Two replicable suppressor situations in personality research. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39(2):303–328. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3902_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigley B, Tedeschi J. Mediating effects of blame attributions on feelings of anger. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1996;22(12):1280–1288. [Google Scholar]

- Quiles Z, Bybee J. Chronic and predispositional guilt: Relations to mental health, prosocial behavior and religiosity. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1997;69(1):104–126. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6901_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimer M. The Adolescent Shame Measure (ASM) Temple University; Philadelphia: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart M, Ahadi S, Hershey K. Temperament and social behavior in childhood. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1994;40(1):21–39. [Google Scholar]

- Rice ME, Harris GT, Cormier CA. An evaluation of a maximum security therapeutic community for psychopaths and other mentally disordered offenders. Law and Human Behavior. 1992;16:399–412. [Google Scholar]

- Scheff T. The role of shame in symptom formation. Hillsdale, NJ, England: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1987. The shame-rage spiral: A case study of an interminable quarrel; pp. 109–149. [Google Scholar]

- Stuewig J, McCloskey L. The Relation of Child Maltreatment to Shame and Guilt Among Adolescents: Psychological Routes to Depression and Delinquency. Child Maltreatment. 2005;10(4):324–366. doi: 10.1177/1077559505279308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuewig J, Tangney JP. Shame and guilt in antisocial and risky behaviors. In: Tracy JL, Robins RW, Tangney JP, editors. The Self-Conscious Emotions: Theory and Research. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. pp. 371–388. [Google Scholar]

- Stuewig J, Tangney JP, Mashek D, Forkner P, Dearing RL. The moral emotions, alcohol dependence, and HIV risk behavior in an incarcerated sample. Substance Use and Misuse. 2009;44(4):449–471. doi: 10.1080/10826080802421274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sykes G, Matza D. Techniques of neutralization: A theory of delinquency. American Sociological Review. 1957;22:664–670. [Google Scholar]

- Tangney J. Moral affect: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61(4):598–607. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.4.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangney J. Situational determinants of shame and guilt in young adulthood. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1992;18(2):199–206. [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP, Boone A, Dearing R. Forgiving the Self: Conceptual Issues and Empirical Findings. In: Worthington E Jr, editor. Handbook of Forgiveness. NY: Brunner-Routledge; 2005. pp. 143–158. [Google Scholar]

- Tangney J, Dearing R. Shame and guilt. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP, Hill-Barlow D, Wagner PE, Marschall DE, Borenstein JK, Sanftner J, Mohr T, Gramzow R. Assessing individual differences in constructive vs. destructive responses to anger across the lifespan. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70:780–796. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.4.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangney J, Mashek D, Stuewig J. Working at the Social-Clinical-Community-Criminology Interface: The George Mason University inmate study. Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology. 2007;26(1):1–21. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2007.26.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP, Stuewig J, Mashek D. Moral emotions and moral behavior. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:345–372. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP, Wagner PE, Gavlas J, Gramzow R. The Anger Response Inventory for Adolescents (ARI-A) Fairfax, VA: George Mason University; 1991a. [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP, Wagner PE, Gavlas J, Gramzow R. The Test of Self-Conscious Affect for Adolescents (TOSCA-A) Fairfax, VA: George Mason University; 1991b. [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP, Wagner P, Gramzow R. The Test of Self-Conscious Affect (TOSCA) Fairfax, VA: George Mason University; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Tangney J, Wagner P, Gramzow R. Proneness to shame, proneness to guilt, and psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1992a;101(3):469–478. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.101.3.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangney J, Wagner P, Fletcher C, Gramzow R. Shamed into anger? The relation of shame and guilt to anger and self-reported aggression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992b;62(4):669–675. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.62.4.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP, Wagner PE, Hill-Barlow D, Marschall DE, Gramzow R. Relation of shame and guilt to constructive versus destructive responses to anger across the lifespan. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70:797–809. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.4.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP, Wagner PE, Marschall D, Gramzow R. The Anger Response Inventory (ARI) Fairfax, VA: George Mason University; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi J, Nesler M. Grievances: Development and reactions. In: Felson R, Tedeschi J, editors. Aggression and violence: Social interactionist perspectives. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association; 1993. pp. 13–45. [Google Scholar]

- Tracy J, Robins R. Appraisal Antecedents of Shame and Guilt: Support for a Theoretical Model. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2006;32(10):1339–1351. doi: 10.1177/0146167206290212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell PD, Campbell JD. Private self-consciousness and the five factor model of personality: Distinguishing rumination from reflection. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;76:284–304. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.76.2.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.