Abstract

AIMS

To characterize the effects of levofloxacin on QT interval in healthy subjects and the most appropriate oral positive control treatments for International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) E14 QT/QTc studies.

METHODS

Healthy subjects received a single dose of levofloxacin (1000 or 1500 mg), moxifloxacin (400 mg) or placebo in a four-period crossover design. Digital 12-lead ECGs were recorded in triplicate. Measurement of QT interval was performed automatically with subsequent manual onscreen over-reading using electronic callipers. Blood samples were taken for determination of levofloxacin and moxifloxacin concentrations.

RESULTS

Mean QTcI (QT interval corrected for heart rate using a correction factor that is applicable to each individual) was prolonged in subjects receiving moxifloxacin 400 mg compared with placebo. The largest time-matched difference in QTcI for moxifloxacin compared with placebo was observed to be 13.19 ms (95% confidence interval 11.21, 15.17) at 3.5 h post dose. Prolonged mean QTcI was also observed in subjects receiving levofloxacin 1000 mg and 1500 mg compared with placebo. The largest time-matched difference in QTcI compared with placebo was observed at 3.5 h post dose for both 1000 mg and 1500 mg of levofloxacin [mean (95%) 4.42 ms (2.44, 6.39) in 1000 mg and 7.44 ms (5.47, 9.42) in 1500 mg]. A small increase in heart rate was observed with levofloxacin during the course of the study. However, moxifloxacin showed a greater increase compared with levofloxacin.

CONCLUSIONS

Both levofloxacin and moxifloxacin can fulfil the criteria for a positive comparator. The ICH E14 guidelines recommend a threshold of around 5 ms for a positive QT/QTc study. The largest time-matched difference in QTc for levofloxacin suggests the potential for use in more rigorous QT/QTc studies. This study has demonstrated the utility of levofloxacin on the assay in measuring mean QTc changes around 5 ms.

Keywords: clinical trial, healthy subject, levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, QTc

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ABOUT THIS SUBJECT

New drugs are expected to undergo rigorous clinical electrocardiographic evaluation (‘thorough QT/QTc study’) during their early clinical development in order to determine any affect on cardiac repolarization.

The fluoroquinolone antibiotic moxifloxacin (400 mg) has been used as a positive comparator for thorough QT/QTc studies due to its QT prolongation (QTcF) of between 6 and 10 ms.

Positive comparators that are able to produce mean changes close to the regulatory guidelines of 5 ms, and which can be detected by the assay in use, would enable a more rigorous evaluation of the assay conditions used in evaluating new chemical entities.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

This thorough QT/QTc study directly compares the effects of two doses of levofloxacin and moxifloxacin on QTc in the same healthy subjects.

Mean QTc was prolonged in subjects receiving levofloxacin compared with placebo as determined by both individual and Fridericia's heart rate correction methods.

The largest time-matched differences in QTc for two doses of levofloxacin compared with placebo suggest the potential for using levofloxacin in more rigorous QT/QTc studies, providing a robust evaluation of the assay conditions used in determining potential effects on cardiac repolarization.

There is evidence to suggest that levofloxacin moderately increases heart rate in a dose-dependent fashion.

Introduction

It is well known that some drugs cause delayed cardiac repolarization, which could potentially lead to the development of cardiac arrhythmias such as torsades de pointes and other ventricular tachyarrhythmias. The effect of drugs on cardiac repolarization is of great concern, especially in the early stages of clinical development. This effect can be measured as prolongation of the QT interval on the surface electrocardiogram (ECG). Due to its inverse relationship to heart rate, the measured QT interval is normally transformed by various heart rate correction formulae into a value known as the ‘corrected QT’ (QTc) interval, which is independent of heart rate. The majority of drug-induced QT/QTc prolongation appears to be mediated through blockade of the IKr ion channel responsible for the rapid delayed rectifier current involved in repolarization of the ventricular action potential.

Therefore new drugs are expected to undergo rigorous clinical electrocardiographic evaluation during their early clinical development, usually including a single clinical trial dedicated to the evaluation of their effects on cardiac repolarization (‘thorough QT/QTc study’) [1]. The aim of the thorough QT/QTc study is to determine whether a drug has a threshold effect on cardiac repolarization as detected by QT/QTc prolongation. According to the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) guideline, the sensitivity target of a thorough QT/QTc study is defined as a mean increase in QTc interval of approximately 5 ms, and an upper limit of the 95% two-sided confidence interval (CI) around the mean effect on QTc of 10 ms [2].

The effect of the fluoroquinolone antibiotics on QT intervals in humans, together with their relative safety in terms of prolongation of QTc interval, has been the basis for the use of these agents as positive comparators for thorough QT/QTc study [3, 4]. Among these, moxifloxacin is known to influence ventricular repolarization and therefore has been used as one of the desirable drugs for a positive control treatment [5–7]. By inhibiting IKr channels, moxifloxacin can lead to an average QT prolongation (QTcF) of between 6 and 10 ms at a dose of 400 mg and approximately double the increase in prolongation at a dose of 800 mg with very little effect on heart rate [2, 8].

In contrast, levofloxacin has been shown to have effects on IKr channels at only relatively high concentrations [6]. Previous studies have demonstrated that the effects of a single 1000 mg dose of levofloxacin (which is greater than a recommended dose of 750 mg) on QTc intervals were considerably less than those measured after a single 800 mg dose of moxifloxacin. However, significant changes in QT/QTc intervals were observed after exposure to 1500 mg levofloxacin [7, 9, 10]. Unlike moxifloxacin, single 1000 mg and 1500 mg doses of levofloxacin also increased heart rate in healthy subjects [9]. These findings suggest that higher doses of levofloxacin may have the potential for influencing ventricular repolarization. However, according to more recent publications, no effect of levofloxacin on QT/QTc intervals was evident at any dose [11, 12]. Therefore, the clinical relevance of using levofloxacin in QT/QTc studies remains uncertain.

The aim of this study was to characterize the most appropriate oral positive control treatments for ICH E14 QT/QTc studies. A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, double dummy, 4 × 4 crossover study design was employed in this study to evaluate if levofloxacin and moxifloxacin could be used effectively as a positive comparator in QT/QTc studies according to the definition of the ICH E14 guidelines [2].

Methods

Subjects

The study population consisted of 64 healthy, nonsmoking, male and female subjects with a mean age of 29 ± 7 years, with a body mass index (BMI) in the range 19.9–28.7 kg m−2. Subjects were excluded (i) if they had clinically significant medical history or family history of congenital long QT syndrome, (ii) if they had an abnormal ECG (PR consistently < 120 or >230 ms, QRS consistently > 120 ms, QTcB > 430 ms for men and >450 ms for women) and (iii) if they used concomitant medication or any medication that would interfere with levofloxacin/moxifloxacin absorption or elimination. Pregnant or lactating women were also excluded. All subjects provided written informed consent prior to any study-specific procedures being undertaken.

Study design

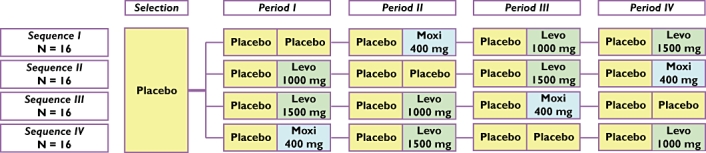

This was a single-centre, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, double dummy, 4 × 4 crossover study (Figure 1). Eligible subjects were randomized into a four-period crossover comparison of placebo, moxifloxacin and levofloxacin. Each period consisted of 2 days, one placebo baseline day (P1D01, P3D01, P5D01 and P7D01) and one treatment day (P1D02, P3D02, P5D02 and P7D02), separated by a 2-day wash-out period (72 h). The wash-out period of 72 h was selected on the basis of the pharmacokinetic terminal half-life and the effect on the QT interval of the investigational drugs. The pharmacodynamic effect of moxifloxacin on QT can be described as an anticlockwise hysteresis, i.e. the pharmacodynamic effect outlasts the plasma concentration of moxifloxacin. The lack of a carry-over effect was confirmed by comparing raw pharmacokinetic data at zero hour time point and baseline QTc values for all periods (data not shown). Pharmacokinetic and ECG profiling was performed over a 24 h period after each dose of study medication. Subjects received single oral doses of moxifloxacin 400 mg (Izilox®; Bayer Pharma SAS, Puteaux, France), levofloxacin 1000 mg and 1500 mg (Tavanic®; Laboratoire Aventis, Groupe Sanofi-aventis, Paris, France), and placebo in a random order with a 2-day wash-out between doses. All subjects were hospitalized over 17 nights in order to avoid any possible bias on diet restrictions and to standardize the conditions between each ECG evaluation day. The study was approved by the local ethics committee (Covance Clinical Research Unit, Independent Ethics Committee, Leeds, UK) and the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Authority, and was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Figure 1.

Summary of study design – a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, double dummy, 4 × 4 crossover study

ECG assessments and QTc evaluation

Twelve-lead ECGs were recorded using a MAC1200® recorder (GE Healthcare, Slough, UK) and stored electronically on the MUSE CV® information system (GE Healthcare). The recordings were made for 24 h after dosing with placebo/moxifloxacin/levofloxacin on P1D02, P3D02, P5D02 and P7D02 (Figure 1). ECG recordings were taken at −2, −1 and 0 h predosing to establish a baseline, and then at 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3, 3.5, 4, 4.5, 5, 5.5, 6, 6.5, 7, 7.5, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 and 24 h post dose on day P1D01. For the remaining study days (P1D02, P3D01, P3D02, P5D01, P5D02, P7D01, P7D02), ECG recordings were taken at 0 h predose and then 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3, 3.5, 4, 8, 12 and 24 h post dose. At each time point, ECGs were recorded in triplicate to reduce the variance and improve the precision of measurement. Each ECG lasted 10 s and triplicates were performed at 1-min intervals during 3 min. Before any ECG recordings were made, subjects maintained an undisturbed supine resting position for at least 10 min and avoided postural changes during the ECG recordings. During hospitalization, subjects were served the same light lunch (3–4 h) and light dinner (10–11 h) post dose. On treatment days, no breakfast was served and the subjects fasted until lunch.

Data analysis and statistical methods

The effect on QT/QTc interval was analysed using the largest time-matched mean difference between moxifloxacin/levofloxacin and placebo (baseline adjusted). ECGs were taken in triplicate at each time point and the QTc interval was expressed as the mean of these three values. Each treatment period had a baseline day and treatment day. For each treatment the QT/QTc interval value change at each time point was expressed as the difference between baseline and treatment day from baseline (ΔQTc). The effect size was then determined as the time-matched, baseline-adjusted QT/QTc interval value for levofloxacin/moxifloxacin vs. placebo (ΔΔQTc) [13]. Measurement of the QT interval was performed automatically with subsequent manual on-screen over-reading using electronic callipers (MUSE CV® Interval Editor; GE Healthcare) by cardiologists with extensive experience with manual QT measurement (including on-screen measurement with electronic callipers) from the Department of Cardiological Sciences (St George's University of London, UK). After inclusion, the over-reading cardiologists were blinded to time, date, treatment and any data identifying the subject. All ECGs for each subject were over-read by two cardiologists whose readings were then compared and validated. During this study, the ECG reader intravariability was assessed by repeating 10% of all QT measurements (selected at random) to ensure the quality of manual ECG assessments.

The following four QT correction formulae were initially calculated in each subject:

Individual correction (QTcI) (linear and nonlinear models)

Population-based correction (QTcP) optimized for all the data of the study pooled together (linear and nonlinear models)

Fridericia's correction (QTcF = QT/RR°,33)

Bazett's correction (QTcB = QT/RR°,5).

All evaluable ECGs were included in the QT correction analysis except for those that were excluded by the cardiologists. Among these four correction formulae, the best correction was determined by the statistician under blinded conditions based on the mean squared error approach. Having considered the number of available ECGs per subject and the heart rate range, the primary criterion was determined to be QTcI in this study as the most accurate heart rate correction [2]. However, QTcF, which has been widely used in many QTc studies, was also employed as the secondary measurement to compare our data with previously published results. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.1 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

The treatment effect of moxifloxacin 400 mg, levofloxacin 1000 mg and levofloxacin 1500 mg compared with placebo on the QTc change (primary safety criterion) per time point was estimated using a mixed model taking into account the cross-over design, with gender, baseline, period and carry-over effect as covariates, and subject as random effect: a 95% CI of the difference between adjusted treatments means was derived.

Sample size was estimated on QTc interval change for a difference between levofloxacin (1000 mg or 1500 mg) or moxifloxacin (400 mg) vs. placebo, using two-sided Student's t-test for paired samples at 5% type I error on the safety set [14]. For an 8.5 ms intraindividual variability (within-subject SD), and under the hypothesis of a withdrawal rate of 15%, 64 subjects were necessary to reach statistical significance in the comparison between treatments, with a power of 85%, assuming a difference of at least 5 ms.

Pharmacokinetic assessments

Pharmacokinetic samples were taken to quantify the single-dose moxifloxacin and levofloxacin concentrations during ECG assessments and to investigate any relationship between concentration and QTc for moxifloxacin and levofloxacin. Blood samples (6 ml) were taken at 0 h predose and at 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3, 3.5, 4, 8, 12 and 12 h post dose with moxifloxacin or levofloxacin on days P1D02, P3D02, P5D02 and P7D02 (Figure 1). Plasma samples for moxifloxacin and levofloxacin concentrations were analysed using liquid chromatography with mass spectrometry. Plasma concentrations of moxifloxacin and levofloxacin were determined according to validated methods over a nominal calibration range of 0.1–15 µg ml−1 in plasma. Pharmacokinetic analysis was performed using WinNonlin® software version 3.3 (Pharsight Corp., Mountain View, CA, USA). Noncompartmental pharmacokinetic analyses were performed on the individual plasma concentrations of moxifloxacin and levofloxacin, and the maximum observed plasma concentration (Cmax), time to Cmax (tmax), plasma concentration at 24 h post dosing (C24), and area under the plasma concentration–time curve over 24 h (AUC24) were calculated.

Safety assessments

All adverse events (AEs) were recorded from the first dose of study medication until the follow-up visit, either when reported spontaneously or following direct, nonleading questions. The intensity and potential relationship with the study drugs of each of the reported AEs were assessed. Vital signs, blood pressure (systolic and diastolic) and heart rate were regularly measured during the study. Laboratory investigations including haematology, biochemistry and urinalysis were performed during the screening period and at follow-up. Any clinically relevant abnormalities in vitals signs or laboratory tests were reported as AEs.

Results

Subject demographics and disposition

A total of 175 participants were screened, and 64 subjects were actually included in the study and randomized to one of four treatment sequences. All of the subjects were White, with a mean age of 29 ± 7 years, 53.1% (n= 34) of the subjects were male and 46.9% (n= 30) were female. All subjects had a BMI that ranged from 19.9 to 28.7 kg m−2 with a mean value of 24.1 ± 2.3 kg m−2. None of the randomized subjects received any concomitant treatment during the course of the study. Three subjects were withdrawn, two due to AEs (see ‘Safety and tolerability’) and one for a nonmedical reason. The ECG data from all 64 subjects were included in the descriptive and statistical QTc analysis.

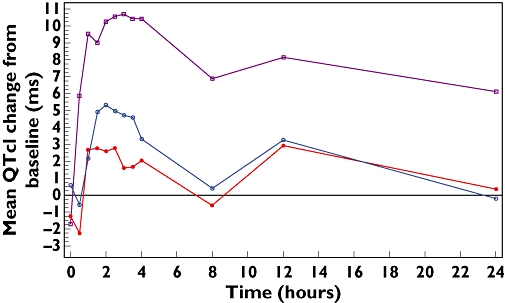

Effect of moxifloxacin 400 mg on QTc

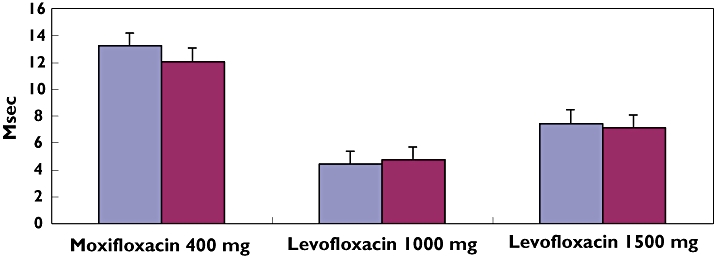

Mean QTcI was prolonged in subjects receiving moxifloxacin 400 mg compared with placebo (Figure 2). From 0.5 h onwards, the point estimate of the difference from placebo in QTcI ranged from 5.83 to 13.19 ms. The largest time-matched difference in QTcI for moxifloxacin compared with placebo was observed at 3.5 h post dose (mean 13.19 ms, 95% CI 11.21, 15.17) (Table 1) (Figure 3). A similar pattern was seen when heart rate was corrected using QTcF, with the largest time-matched difference in QTcF occurring at 3.5 h post dose (mean 12.03 ms, 95% CI 10.06, 14.00) (Figure 3). Mean baseline QTc measurements for the two correction formulae and both moxifloxacin and placebo were similar (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Mean QTcI change from baseline against time for moxifloxacin 400 mg, levofloxacin 1000 mg and levofloxacin 1500 mg. Lev 1000 mg ( ); Lev 1500 mg (

); Lev 1500 mg ( ); Moxi 400 mg (

); Moxi 400 mg ( )

)

Table 1.

Largest time-matched QTcI and QTcF (ms) change from P-baseline to P-post-baseline comparison between moxifloxacin 400 mg, levofloxacin 1000 mg, levofloxacin 1500 mg and placebo

| Moxifloxacin 400 mg | Placebo | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| QTcI | (n= 62) | (n= 62) | |

| P-baseline | Mean ± SD | 402.4 ± 11.1 | 403.0 ± 11.1 |

| P-post-baseline | 412.8 ± 12.4 | 400.2 ± 11.4 | |

| P-post-baseline – P-baseline | 10.4 ± 6.1 | −2.8 ± 6.1 | |

| Statistical analysis of change | Estimate (1) | 13.19 (1.00) | |

| 95% CI (2) | (11.21, 15.17) | ||

| Levofloxacin 1000 mg | Placebo | ||

| (n= 63) | (n= 62) | ||

| P-baseline | Mean ± SD | 402.8 ± 10.4 | 403.0 ± 11.1 |

| P-post-baseline | 404.5 ± 11.3 | 400.2 ± 11.4 | |

| P-post-baseline – P-baseline | 1.7 ± 6.8 | −2.8 ± 6.1 | |

| Statistical analysis of change | Estimate (3) | 4.42 (1.00) | |

| 95% CI (4) | (2.44, 6.39) | ||

| Levofloxacin 1500 mg | Placebo | ||

| (n= 62) | (n= 62) | ||

| P-baseline | Mean ± SD | 403.1 ± 12.7 | 403.0 ± 11.1 |

| P-post-baseline | 407.7 ± 13.3 | 400.2 ± 11.4 | |

| P-post-baseline – P-baseline | 4.6 ± 6.5 | −2.8 ± 6.1 | |

| Statistical analysis of change | Estimate (5) | 7.44 (1.00) | |

| 95% CI (6) | (5.47, 9.42) | ||

| Moxifloxacin 400 mg | Placebo | ||

| QTcF | (n= 62) | (n= 62) | |

| P-baseline | Mean ± SD | 402.0 ± 11.1 | 402.9 ± 11.4 |

| P-post-baseline | 411.4 ± 13.5 | 400.0 ± 11.8 | |

| P-Post-baseline – P-baseline | 9.4 ± 6.4 | −2.8 ± 6.3 | |

| Statistical analysis of change | Estimate (1) | 12.03 (1.00) | |

| 95% CI (2) | (10.06, 14.00) | ||

| Levofloxacin 1000 mg | Placebo | ||

| (n= 63) | (n= 62) | ||

| P-baseline | Mean ± SD | 402.4 ± 11.1 | 402.9 ± 11.4 |

| P-post-baseline | 404.4 ± 11.3 | 400.0 ± 11.8 | |

| P-post-baseline – P-baseline | 2.1 ± 6.9 | −2.8 ± 6.3 | |

| Statistical analysis of change | Estimate (3) | 4.73 (0.99) | |

| 95% CI (4) | (2.78, 6.99) | ||

| Levofloxacin 1500 mg | Placebo | ||

| (n= 62) | (n= 62) | ||

| P-baseline | Mean ± SD | 402.8 ± 12.9 | 402.9 ± 11.4 |

| P-post-baseline | 407.1 ± 12.9 | 400.0 ± 11.8 | |

| P-post-baseline – P-baseline | 4.3 ± 6.0 | −2.8 ± 6.3 | |

| Statistical analysis of change | Estimate (5) | 7.12 (0.99) | |

| 95% CI (6) | (5.16, 9.09) |

(1) Estimate (standard error) of the adjusted changes differences: moxifloxacin 400 mg minus placebo. (2) 95% CI of the adjusted changes differences between moxifloxacin 400 mg and placebo. (3) Estimate (standard error) of the adjusted changes differences: levofloxacin 1000 mg minus placebo. (4) 95% CI of the adjusted changes differences between levofloxacin 1000 mg and placebo. (5) Estimate (standard error) of the adjusted changes differences: levofloxacin 1500 mg minus placebo. (6) 95% CI of the adjusted changes differences between levofloxacin 1500 mg and placebo.

Figure 3.

Largest time-matched difference from placebo in QTc: (QTcI and QTcF). QTcI ( ); QTcF (

); QTcF ( )

)

Effect of levofloxacin 1000 mg and 1500 mg on QTc

Prolonged mean QTcI was also observed in subjects receiving levofloxacin 1000 mg and 1500 mg compared with placebo (Figure 2). From 1 h onwards, the point estimate of the difference from placebo in QTcI ranged from 0.05 to 4.42 ms with levofloxacin 1000 mg, whereas it ranged from 0.97 to 7.44 ms with levofloxacin 1500 mg. The largest time-matched difference in QTcI compared with placebo was observed at 3.5 h post dose for both 1000 mg and 1500 mg of levofloxacin (mean 4.42 ms, 95% CI 2.44, 6.39 in 1000 mg and 7.44 ms, 95% CI 5.47, 9.42 in 1500 mg) (Table 1) (Figure 3). In a similar manner, the largest time-matched difference in QTcF was observed at 3.5 h post dose (mean 4.73 ms, 95% CI 2.78, 6.99 in levofloxacin 1000 mg and mean 7.12 ms, 95% CI 5.16, 9.09 in levofloxacin 1500 mg) (Figure 3). Mean baseline QTc measurements for the two correction formulae and both doses of levofloxacin and placebo were similar (Table 1).

For both treatments we found a marked gender difference when using the individual correction factor, whereas no gender difference was observed when using Fridericia's correction factor (data not shown). The largest time-matched difference in QTcI at 3.5 h post dose for men (moxifloxacin 400 mg, levofloxacin 1000 mg and levofloxacin 1500 mg) was 11.83 ms (8.87, 14.79), 2.92 ms (−0.07, 5.90) and 6.59 ms (3.60, 9.58) and for women was 14.93 ms (11.71, 18.14), 6.14 ms (2.98, 9.30) and 8.40 ms (5.21, 11.59), compared with the largest time-matched difference in QTcF at 3.5 h post dose for men who had values of 11.41 ms (8.39, 14.44), 4.33 ms (1.28, 7.37), 7.31 ms (4.27, 10.36) and for women who had values of 12.98 ms (9.70, 16.26), 5.29 ms (2.07, 8.52) and 6.91 ms (3.65, 10.16).

Categorical analysis

No subject at any time in the study had a QTcI > 450 ms. A similar pattern was seen with the other three heart rate corrections, with no subjects having a maximum QTcF value > 450 ms. With the exception of one female subject, all subjects had changes from baseline in QTcI which were ≤ 30 ms. The female subject was receiving moxifloxacin treatment and had an increase from baseline of 33 ms at 1 h post dose. There were no changes from baseline in QTcI that were >60 ms at any measurement time point.

Heart rate change from baseline and moxifloxacin/levofloxacin concentration

Both the 1000 mg and 1500 mg doses were associated with a small increase in heart rate change compared with baseline (Figure 4). However, moxifloxacin showed a greater increase in heart rate compared with levofloxacin.

Figure 4.

Heart rate change from baseline against plasma concentration for moxifloxacin 400 mg, levofloxacin 1000 mg and levofloxacin 1500 mg. Lev 1000 mg ( ); Lev 1500 mg (

); Lev 1500 mg ( ); Moxi 400 mg (

); Moxi 400 mg ( )

)

Pharmacokinetics of moxifloxacin and levofloxacin

Following a single oral administration of moxifloxacin 400 mg, mean maximum plasma concentrations were reached after 0–0.5 h at a level of 2.5 µg ml−1. Mean exposure (AUC24) was approximately 26 µg h−1 ml−1 (Table 2). The moxifloxacin parameters observed in this study were in the same range as those presented previously in the literature [15–18]. Following a single administration of levofloxacin 1000 mg, mean maximum plasma concentrations were reached after 0–0.5 h at a level of 10 µg ml−1. As shown in Table 2, mean exposure (AUC24) was approximately 100 µg h−1 ml−1. Mean maximum plasma concentrations were reached after 0–0.5 h at a level of 13 µg ml−1 following a single administration of levofloxacin 1500 mg. Mean exposure (AUC24) was approximately 150 µg h−1 ml−1 (Table 2). Levofloxacin parameters observed in this study were in the same range as those presented in the literature [9, 19, 20].

Table 2.

Pharmacokinetic parameters for plasma concentration of moxifloxacin and levofloxacin

| Moxifloxacin (400 mg) | |

|---|---|

| n | 62 |

| Cmax, µg ml−1 | 2.5 ± 0.81 (2.4) |

| tmax, h | 1.6 [0.58–4.1] |

| AUC24, µg h−1 ml−1 | 26 ± 5.0 (25) |

| Levofloxacin (1000 mg) | |

| n | 63 |

| Cmax, µg ml−1 | 9.6 ± 2.1 (9.5) |

| tmax, h | 2.1 [1.1–4.1] |

| AUC24, µg h−1 ml−1 | 99 ± 17 (96) |

| Levofloxacin (1500 mg) | |

| n | 62 |

| Cmax, µg ml−1 | 13 ± 2.1 (13) |

| tmax, h | 2.6 [1.1–8.1] |

| AUC24, µg h−1 ml−1 | 150 ± 26 (146) |

Mean ± SD (median). tmax expressed as median [range].

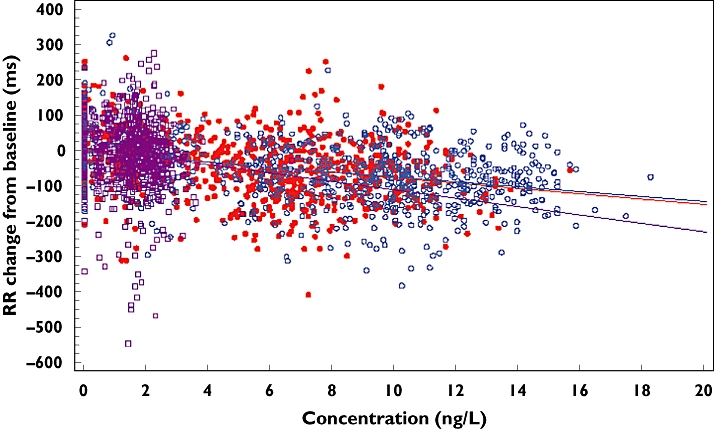

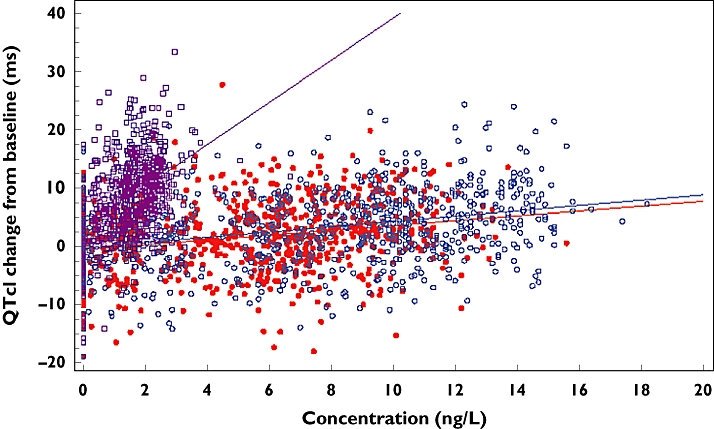

Relationship between QTcI change from baseline and moxifloxacin or levofloxacin concentration

This analysis showed an increase in individually corrected QTcI change from baseline over the range of levofloxacin concentrations studied. The slope (both the levofloxacin 1000 mg and 1500 mg doses had similar slopes) predicted an increase in QTcI change from baseline of approximately 2.5 ms per 7 ng l−1 (Figure 5). This corresponded to an increase in QTcI change of approximately 7.5 ms at the higher end of the concentration range studied (0–20 ng l−1). Moxifloxacin was found to have a change of approximately 2.5 ms per 0.7 ng l−1 corresponding to approximately a 22 ms increase in QTcI change at the higher end of the moxifloxacin concentration range (0–6 ng l−1).

Figure 5.

QTcI change from baseline against plasma concentration for moxifloxacin 400 mg, levofloxacin 1000 mg and levofloxacin 1500 mg. Lev 1000 mg ( ); Lev 1500 mg (

); Lev 1500 mg ( ); Moxi 400 mg (

); Moxi 400 mg ( )

)

Safety and tolerability

Overall, both moxifloxacin and levofloxacin were well tolerated by healthy subjects in this study. A total of 39 AEs were reported during the study. Thirty-four (53.1%) subjects reported AEs that were considered to be mild and two (3.1%) reported AEs that were considered to be moderate. No subject reported a severe AE. AEs considered to be related to study treatment were reported by 9.3% subjects on levofloxacin 1000 mg, 18.8% subjects on levofloxacin 1500 mg, 10.9% subjects on moxifloxacin, and 6.3% subjects on placebo. No serious or severe AEs were observed. The most frequent AEs included nausea and dizziness, both of which are expected as known drug reactions to both moxifloxacin and levofloxacin. The number of reported AEs was similar between the three treatments with no unexpected AEs observed. Nausea was reported by three (4.7%) subjects (three instances) following levofloxacin 1000 mg treatment. During levofloxacin 1500 mg treatment nausea was reported by seven (10.9%) subjects (seven instances), postural dizziness by two (3.1%) subjects (two instances) and dizziness by two (3.1%) subjects (two instances). Nausea was reported by six (9.4%) subjects (six instances) following moxifloxacin 400 mg treatment. Following placebo treatment, dizziness was reported by two (3.1%) subjects (three instances). No clinically significant changes were seen in laboratory parameters or in vital signs. Only two subjects were withdrawn due to AEs. One subject (Subject 10018) suffered from sustained supraventricular tachycardia and the second (Subject 20010) suffered from anxiety. Both AEs occurred following treatment with moxifloxacin 400 mg.

Discussion

The ICH E14 guidelines state that a negative thorough QT/QTc study is one where the largest time-matched mean difference between the drug and placebo for QTc is not greater than 5 ms, with a CI interval that excludes an effect of ≥10 ms. The use of positive controls that routinely produce relatively large signals such as a mean increase of ≥10 ms may have some value in establishing the validity of new methodologies or in providing a background for the effects of the investigational drug. However, it may not provide a convincing demonstration of the assay sensitivity. Therefore, it is possible that a higher-than-expected effect size for a particular positive control would raise questions about the sensitivity of the individual study [7]. This scenario has been discussed in the ICH E14 implementation group Questions and Answers document in relation to assessing the adequacy of positive controls in thorough QT/QTc studies [21]. This document highlights the importance of the size of the effect of the positive control when assessing the ability of the study to detect changes around regulatory guidelines of 5 ms.

As moxifloxacin produces a mean increase of ≥10 ms, it has been considered to be a good candidate for a positive comparator in QT/QTc studies, which validates new methodologies and provides a background for the effects of the investigational product. We have previously confirmed that moxifloxacin can consistently produce mean increases in QT (QTcF) of between 6 and 12 ms [1, 22]. In the present study, the observed prolongation in mean QTcF of 12.03 ms agrees well with the findings from other studies using moxifloxacin as a positive comparator [8, 23–29]. Indeed, the large increase observed in QTc with moxifloxacin (mean increase of ≥10 ms) may make it relatively easy to confirm the validity of the QT/QTc study, but it is likely to compromise the assay sensitivity. Therefore, moxifloxacin could be too strong as a positive comparator in QT/QTc studies.

In contrast, positive comparators that are known to produce mean changes close to the regulatory guidelines of 5 ms, and which can be detected by the assay in use for a particular study, would provide a more rigorous analysis of the study drug and examine its potential to prolong QTc in a more effective manner. This study has demonstrated a mean change in QTcF using levofloxacin of 4.73 ms (1000 mg) and 7.12 ms (1500 mg). This is in agreement with previously published data [9]. Therefore, levofloxacin may be a more appropriate positive comparator producing QTc changes closer to the regulatory requirements. However, other studies indicated that levofloxacin shows no effect on QTc prolongation [11, 12]. This discrepancy could be explained by a relatively small number of subjects analysed in those two studies. In addition, the higher intraindividual SD in QTc was observed probably due to the lack of triplicate ECGs. It should be noted that levofloxacin is not known to cause torsades de pointes and therefore its use as a positive comparator may not extend to the detection of prolonged QT intervals leading to torsades de pointes. Although the recommended dose for levofloxacin is around 500 mg (British National Formulary), well-conducted clinical studies have used supratherapeutic doses of between 750 and 1500 mg without any safety concerns [30]. The ability of levofloxacin to produce mean changes close to the current E14 regulatory threshold would provide a rigorous analysis of the study conditions. In order to evaluate the utility of levofloxacin in a QTc study, we employed a cross-over study design that allows for a direct QTc comparison between moxifloxacin and levofloxacin on identical subjects. In addition, QTcI was primarily used as the most rigorous QTc formula to minimize the effect of heart rate. A small increase in heart rate was observed with levofloxacin during the course of the study. However, moxifloxacin showed a greater increase compared with levofloxacin.

The subjects have well tolerated both drugs in this study. Two supratherapeutic doses of levofloxacin, 1000 mg and 1500 mg, both produced mean QTcI prolongation of 4.42 ms and 7.44 ms, respectively, with an upper limit of the 95% CI around 10 ms (1500 mg). On the other hand, moxifloxacin produced a mean QTcI prolongation of 13.19 ms with an upper limit of the 95% CI >10 ms. No outliers were observed in the moxifloxacin 400 mg, levofloxacin 1000 mg and levofloxacin 1500 mg treatment groups that resulted in QTcI values > 450 ms or a change from baseline in QTcI > 60 ms. All these findings have indicated that both moxifloxacin and levofloxacin can be used as a positive comparator in thorough QT/QTc studies. However, considering the fact that the ICH E14 guidelines recommend a threshold of >5 ms for a positive QT/QTc study, this study has clearly demonstrated the utility of levofloxacin on the assay in measuring mean QTc changes around 5 ms.

In conclusion, the data from this study have demonstrated that both levofloxacin and moxifloxacin can fulfil the criteria for a positive comparator as defined by the ICH E14 regulatory guidelines. However, by comparing these two drugs directly on the same subjects, we have shown that levofloxacin has the potential to provide a more rigorous evaluation of the assay conditions used to detect clinically significant changes in QTc when evaluating new chemical entities.

Competing interests

The study was sponsored by a pharmaceutical company unconnected to the makers of levofloxacin or moxifloxacin.

REFERENCES

- 1.Camm AJ. Clinical trial design to evaluate the effects of drugs on cardiac repolarization: current state of the art. Heart Rhythm. 2005;2(2) Suppl.:S23–9. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2004.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.ICH E14 The Clinical Evaluation of QT/QTc Interval Prolongation and Proarrhythmic Potential for Non-antiarrhythmic Drugs. International Conference on Harmonisation Step 4 Guideline, EMEA, CHMP/ICH/2/04. 25-5-2005. [PubMed]

- 3.Owens RC., Jr Risk assessment for antimicrobial agent-induced QTc interval prolongation and torsades de pointes. Pharmacotherapy. 2001;21:301–19. doi: 10.1592/phco.21.3.301.34206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rubinstein E, Camm J. Cardiotoxicity of fluoroquinolones. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2002;49:593–6. doi: 10.1093/jac/49.4.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Demolis JL, Kubitza D, Tenneze L, Funck-Brentano C. Effect of a single oral dose of moxifloxacin (400 mg and 800 mg) on ventricular repolarization in healthy subjects. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2000;68:658–66. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2000.111482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kang J, Wang L, Chen XL, Triggle DJ, Rampe D. Interactions of a series of fluoroquinolone antibacterial drugs with the human cardiac K+ channel HERG. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;59:122–6. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strnadova C. The assessment of QT/QTc interval prolongation in clinical trials: a regulatory perspective. Drug Information J. 2005;39:407–33. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morganroth J. A definitive or thorough phase 1 QT ECG trial as a requirement for drug safety assessment. J Electrocardiol. 2004;37:25–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Noel GJ, Goodman DB, Chien S, Solanki B, Padmanabhan M, Natarajan J. Measuring the effects of supratherapeutic doses of levofloxacin on healthy volunteers using four methods of QT correction and periodic and continuous ECG recordings. J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;44:464–73. doi: 10.1177/0091270004264643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Noel GJ, Natarajan J, Chien S, Hunt TL, Goodman DB, Abels R. Effects of three fluoroquinolones on QT interval in healthy adults after single doses. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2003;73:292–303. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9236(03)00009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsikouris JP, Peeters MJ, Cox CD, Meyerrose GE, Seifert CF. Effects of three fluoroquinolones on QT analysis after standard treatment courses. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2006;11:52–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-474X.2006.00082.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Makaryus AN, Byrns K, Makaryus MN, Natarajan U, Singer C, Goldner B. Effect of ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin on the QT interval: is this a significant ‘clinical’ event? South Med J. 2006;99:52–6. doi: 10.1097/01.smj.0000197124.31174.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strnadova C. The assessment of QT/QTc interval prolongation in clinical trials: a regulatory perspective. Drug Information J. 2005;39:407–33. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malik M, Hnatkova K, Batchvarov V, Gang Y, Smetana P, Camm AJ. Sample size, power calculations, and their implications for the cost of thorough studies of drug induced QT interval prolongation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2004;27:1659–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2004.00701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stass H, Dalhoff A, Kubitza D, Schühly U. Pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of ascending single doses of moxifloxacin, a new 8-methoxy quinolone, administered to healthy subjects. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:2060–5. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.8.2060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stass H, Kubitza D. Pharmacokinetics and elimination of moxifloxacin after oral and intravenous administration in man. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1999;43(Suppl. B):83–90. doi: 10.1093/jac/43.suppl_2.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aminimanizani A, Beringer P, Jelliffe R. Comparative pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the newer fluoroquinolone antibacterials. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2001;40:169–87. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200140030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sullivan JT, Woodruff M, Lettieri J, Agarwal V, Krol GJ, Leese PT, Watson S, Heller AH. Pharmacokinetics of a once-daily oral dose of moxifloxacin (bay 12-8039), a new enantiomerically pure 8-methoxy quinolone. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2793–7. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.11.2793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chien SC, Chow AT, Natarajan J, Williams RR, Wong FA, Rogge MC, Nayak RK. Absence of age and gender effects on the pharmacokinetics of a single 500-milligram oral dose of levofloxacin in healthy subjects. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1562–5. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.7.1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lubasch A, Keller I, Borner K, Koeppe P, Lode H. Comparative pharmacokinetics of ciprofloxacin, gatifloxacin, grepafloxacin, levofloxacin, trovafloxacin, and moxifloxacin after single oral administration in healthy volunteers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:2600–3. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.10.2600-2603.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.ICH E14 The Clinical Evaluation of QT/QTc Interval Prolongation and Proarrhythmic Potential for Non-antiarrhythmic Drugs. International Conference on Harmonisation. E14 Implementation and Working Group, Questions and Answers. 4-6-2008.

- 22.Dixon R, Job S, Oliver R, Tompson D, Wright JG, Maltby K, Lorch U, Taubel J. Lamotrigine does not prolong QTc in a thorough QT/QTc study in healthy subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;66:396–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2008.03250.x. Epub 2008 Jul 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hulhoven R, Rosillon D, Letiexhe M, Meeus MA, Daoust A, Stockis A. Levocetirizine does not prolong the QT/QTc interval in healthy subjects: results from a thorough QT study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63:1011–7. doi: 10.1007/s00228-007-0366-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malhotra BK, Glue P, Sweeney K, Anziano R, Mancuso J, Wicker P. Thorough QT study with recommended and supratherapeutic doses of tolterodine. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007;81:377–85. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peeters M, Janssen K, Kakuda TN, Schöller-Gyüre M, Lachaert R, Hoetelmans RM, Woodfall B, De Smedt G. Etravirine has no effect on QT and corrected QT interval in HIV-negative volunteers. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42:757–65. doi: 10.1345/aph.1K681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bloomfield D, Kost J, Ghosh K, Hreniuk D, Hickey L, Guitierrez M, Gottesdiener K, Wagner J. The effect of moxifloxacin on QTc and implications for the design of thorough QT studies. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;84:475–80. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davis JD, Hackman F, Layton G, Higgins T, Sudworth D, Weissgerber G. Effect of single doses of maraviroc on the QT/QTc interval in healthy subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;65(Suppl. 1):68–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2008.03138.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hulhoven R, Rosillon D, Bridson WE, Meeus MA, Salas E, Stockis A. Effect of levetiracetam on cardiac repolarization in healthy subjects: a single-dose, randomized, placebo- and active-controlled, four-way crossover study. Clin Ther. 2008;30:260–70. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sarapa N, Nickens DJ, Raber SR, Reynolds RR, Amantea MA. Ritonavir 100 mg does not cause QTc prolongation in healthy subjects: a possible role as CYP3A inhibitor in thorough QTc studies. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;83:153–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100263. Epub 2007 Jun 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Noel GJ, Goodman DB, Chien S, Solanki B, Padmanabhan M, Natarajan J. Measuring the effects of supratherapeutic doses of levofloxacin on healthy volunteers using four methods of QT correction and periodic and continuous ECG recordings. J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;44:464–73. doi: 10.1177/0091270004264643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]