Abstract

We evaluated the benefits of training work skills in a simulated situation to adults with autism by examining their performance at a job site. In the first study, simulation training on new work tasks included the same materials and job coach from the job setting (i.e., a common stimuli approach to promote generalization). In the second study, each participant received training on new work tasks using materials that were different from those in the job setting. In both studies, simulation training was accompanied by improvement in each participant's subsequent job performance. Results are discussed regarding the importance of using research-based procedures in supported work versus practices that are currently popular but not necessarily based on research. Working guidelines are offered for using simulation training to promote more success in supported work among adults with disabilities on the severe end of the autism spectrum.

Descriptors: adults, autism, generalization, job skills, simulation training, supported work

Behavior analysis has made substantial contributions in the area of teaching people with autism. Use of behavioral procedures to promote skill development has not only benefited this population, it has led to increased interest in, and demand for, behavior analysis services (Jacobson & Holburn, 2004). Perhaps most noteworthy, behavioral approaches have helped many individuals with autism function in schools and other community settings in unprecedented ways.

In large part, the success of behavior analysis for promoting community participation has involved children and adolescents with autism, with considerably less success among adults (McClannahan, MacDuff, & Krantz, 2002). Currently, there are far fewer community-based services for adults with autism than services for children and adolescents (Holmes, 2000). There also has been much less research in this area with adults (McClannahan et al.). The relative lack of success regarding community participation is particularly true for adults with more severe disabilities (Orsmond, Krauss, & Seltzer, 2004).

Supported work is one area in which successful community participation by adults with autism is especially lacking (Holmes, 2000). Despite advances in promoting supported work among people with disabilities, relatively few adults with severe disabilities such as autism are employed in community jobs (Conley, 2007). The vast majority of these individuals either do not work or work only to a limited degree in sheltered settings (Conley; White & Weiner, 2004). One reason for the relative lack of supported work opportunities is the amount of training adults with severe disabilities often require to perform job duties. Providing extensive on-the-job training is costly for an employer (Cimera, 2006). In addition, adults with severe disabilities typically work on a part-time basis when they do obtain supported jobs (Garcia-Iriarte, Balcazar, & Taylor-Ritzler, 2007). This limits the amount of time available to train skills on the job while ensuring that the job duties are completed (Reid & Green, 2007).

Recently, we evaluated an approach to teaching supported work skills to adults with autism that involved supplementing on-the-job training with training in simulation when supported workers were not at the job site (Lattimore, Parsons, & Reid, 2006). Simulation training was investigated for several reasons. First, as just noted, there is often limited opportunity for on-the-job training due to the part-time nature of most supported jobs. Training in simulation increases the opportunities to teach job skills. Second, simulation training has been conspicuously absent from currently recommended practices for promoting supported work (Wehman, Brooke, & Revell, 2007), although early behavioral research demonstrated an effective technology for training in simulation (Repp, Favell, & Munk, 1996). More pointedly, as part of the popular support movement for involving people with disabilities in community environments, it is consistently recommended to avoid training in segregated settings separate from actual job sites (Wehman et al.; White & Weiner, 2004). The Lattimore et al. investigation suggested that a previously developed technology of teaching (i.e., behavioral simulation training) may warrant re-emphasis to enhance success in community-based, supported work.

Specifically, the Lattimore et al. (2006) investigation suggested that on-the-job training supplemented with simulation training resulted in faster skill acquisition than on-the-job training alone. However, two important questions related to best practices were left unanswered. First, does simulation training enhance job performance with newly assigned tasks when it is provided prior to on-the-job training? In our previous study, simulation training was conducted while workers were receiving on-the-job training. Providing simulation training with jobs that are likely to be assigned to supported workers may enhance their performance when they subsequently begin performing the duties on the job. Second, is simulation training beneficial if the actual work materials can not be transported away from the job site and, thus, used in training? Our previous investigation involved work tasks that allowed simulation training to be conducted with the same work materials used at the job site. Using the same materials at the simulation and job sites represented a common stimuli approach to training (Stokes & Baer, 1977) that likely facilitated generalization from the simulated site to the actual job. However, many jobs involve materials that can not be removed from a job site.

The purpose of this investigation was to explore these two unanswered questions with adults who had been diagnosed with autism. The adults participated in two studies. In Study 1, we provided simulation training of supported work skills before the adults received on-the-job training with newly assigned work tasks. In Study 2, we again evaluated simulation training but with materials and equipment that were different than those used at the actual job site.

Method

Participants and Settings

Three supported workers who were diagnosed with autism and profound intellectual disabilities participated. Mr. Moss and Mr. Jones, both of whom were 30 years old, and Mr. Glen, age 41, were selected because they were adults with characteristics of severe autism and they worked at the same company. Additionally, the company manager frequently added new work tasks for the workers to perform as part of their jobs. Mr. Moss had an additional diagnosis of Fragile X Syndrome. Mr. Moss and Mr. Jones responded to simple vocal directions accompanied by manual signs. Mr. Glen, who had a severe hearing loss, responded to a small number of manual signs. Each worker's expressive communication primarily involved pointing or leading support personnel to desired objects. All workers displayed stereotypic behavior (e.g., finger gazing, body rubbing) and challenging behavior such as aggression and property destruction, although the latter behavior occurred infrequently at work. Intervention procedures were carried out by the job coach (experimenter) who routinely worked with the supported workers. The job coach had 11 years of supported work experience.

The primary setting was a small publishing company in which the 3 participants had been working on a part-time basis for 11 years. Work duties involved clerical and office cleaning tasks that varied over time based on the needs of the company. Simulation training occurred in a classroom of an adult education program for persons with developmental disabilities on the campus of a residential facility. The supported workers attended the adult education program on weekdays when not at work at the publishing company.

Study 1

Job Tasks

Each supported worker received training on one or two tasks, representing newly assigned work duties that the worker had not performed previously. Mr. Moss and Mr. Glen were taught to prepare folders with advertising material (e.g., place a company logo sticker on the outside of the folder, collate and place fliers in the inside folder pocket). Mr. Jones was taught to prepare folders and information notebooks (e.g., open a notebook binder, place packets of pages in the three-ring binders). A task analysis was developed for each job. The folder preparation and notebook preparation tasks consisted of 19 and 22 steps, respectively. (All task analyses are available at http://www.abainternational.org/BAinPractice.asp). The dependent variable was the percentage of task steps performed independently. To be performed independently, a task step had to be correctly completed by the worker without a preceding prompt (vocal, gestural, or physical) that directed the worker to complete the designated step.

Observation System and Interobserver Agreement

Each worker was observed individually during observation probes as he worked on the newly assigned task at the employing company. The purpose of the observation probes was to evaluate performance on the assigned tasks before and after simulation training. During the observations, each task-analyzed step was recorded as being completed independently or with job coach assistance. Observations were conducted by experimenters from within the workroom of the supported workers or from the doorway to the workroom.

Two experimenters collected data simultaneously but independently during 40% of all probes for each worker, task, and condition. Level of agreement between the two observers was then calculated for reliability purposes. Interobserver agreement was determined on a step-by-step basis, using the formula of number of agreements divided by number of agreements plus disagreements, multiplied by 100%. Overall agreement for independently completed task steps averaged 95% (range, 89% to 100%), occurrence agreement averaged 90% (range, 63% to 100%), and nonoccurrence agreement averaged 85% (range, 33% to 100%).

Baseline Observation Probes

Prior to training, observation probes were conducted on the new tasks assigned to each worker. The purpose of these probes was to evaluate the participants' accuracy in completing the tasks prior to training. The probes were conducted at the publishing company during the regular work time. A probe was initiated by the job coach placing the materials needed to begin a task in the worker's view on the work table and providing a general vocal cue (“work”) or for Mr. Glen, the sign “work.”

If the worker did not correctly initiate the first step of the task analysis within 10 s of the initial cue, the job coach completed the step out of view of the worker so that the materials would be ready for the worker to initiate the second step of the task analysis. The latter process involved the job coach taking the materials necessary to complete the step, turning his back to the worker so that the worker could not see the job coach's actions, completing the step with the materials, and then replacing the materials in front of the worker. If the worker made a response other than correctly completing the first step, the job coach interrupted the response and completed the step out of the worker's view. Each time the job coach completed a step for the worker, the job coach then repeated the general cue to work. If a worker completed a step independently, the job coach did not interact with the worker and let the worker continue proceeding through the task analysis. The process continued until the task was completed. Probes were conducted in this manner because they allowed the worker an opportunity to complete each step without any job coach assistance (i.e., without prompts, models, or reinforcement). This would permit us to evaluate the effects of simulation training on subsequent job performance.

During the baseline phase, the participants followed their usual work schedules at the publishing company, working approximately 1.5 hours per work day. Mr. Moss and Mr. Glen worked 2 mornings per week and Mr. Jones worked 1 morning per week. When not participating in a probe session, the workers worked on other tasks with another job coach, usually involving placement of tabs and labels on advertising fliers.

Simulation Training Sessions

These sessions occurred at the adult education program for each worker on weekdays when workers were not at the job site. To enhance generalization from the simulation site to the job site, stimuli from the job site were incorporated into the simulation training sessions. Specifically, the same job coach who conducted job-site sessions conducted simulation training sessions, and task materials used at the job site were taken to the adult education building to use in the simulation sessions. The effect of simulation training on job performance was evaluated by introducing the training at different points in time across participants (and, for Mr. Jones only, across two job tasks).

To initiate training, the job coach placed the work materials on a table in the worker's view and provided a cue to begin work. If the worker did not initiate a given step in the task analysis within 10 s of the general cue to work or began to make an error on any step, the job coach physically guided the worker through completion of the step. As the worker began to correctly complete a step without physical assistance by the coach, full physical guidance was reduced to partial physical guidance and then to shadowing. Partial physical guidance involved the job coach placing his hands on the worker's arm(s) such that some but not all of the worker's movements necessary to complete the step were guided by the job coach. Shadowing involved the job coach keeping his hands within approximately 9 cm of the worker's arm(s) throughout the worker's movements. The partial physical guidance and shadowing allowed the job coach to immediately interrupt a worker's incorrect action and prevent any step from being completed incorrectly. Interruption occurred as soon as a worker made an incorrect movement associated with a task step.

The physical guidance and shadowing were faded to vocal and/or gestural prompts as the worker became more proficient. However, if incorrect actions continued after a vocal or gestural prompt, the job coach quickly interrupted the worker's movements and provided a physical prompt. Prevention of errors was considered critical to minimize practice of incorrect performance and prevent material waste when work products would be considered unusable by the employing company (e.g., placing a logo sticker upside down on a folder). A total task procedure was used in which training occurred on each subsequent step in the task analysis in the manner just described. Praise was provided either vocally or with signing for approximately every fourth step completed correctly, which approximated the reinforcement schedule used by job coaches at the job site.

Each simulation training session consisted of 10 training trials, requiring between 10 min and 30 min. The goal for simulation training was completing at least 80% of the steps of the task analysis independently during a training session. The 80% criterion had been previously established at the company for workers who attended work with the support of a job coach. Mr. Moss required 5 simulation training sessions to reach criterion (conducted across 5 days), Mr. Glen required 2 simulation sessions (2 days), and Mr. Jones required 3 for the folder task (3 days) and 2 for the notebook task (2 days).

Post-Simulation Training Observation Probes

When a worker met criterion with simulation training at the adult education site, on-the-job observations were initiated at the publishing company in the same manner as the baseline observation probes described earlier. The purpose of these observations was to determine if the workers would perform the steps of the jobs without assistance following simulation training. As soon as a worker completed at least 80% of a given job's steps independently during an observation probe at the company, the worker began performing that task as part of the regular job routine.

Regular Job Routine and Follow-Up Observations

Observations were conducted of the worker performing the task as part of his regular job routine. The job routine involved a job coach providing an instruction to perform the task, intermittently praising correct performance, and interrupting the supported worker's actions if incorrect performance occurred. The interruption involved a correction procedure similar to training in terms of the job coach providing a more helpful prompt following the error. Follow-up observations were subsequently conducted to assess long-term maintenance of the improvements in performing the job tasks. During the follow-up periods, the participants worked on the target tasks periodically (approximately at least every 2 weeks) in addition to working on other tasks at the company. A company supervisor made periodic checks of the quality of the completed work as part of the usual work routine. Throughout the investigation, the company deemed all work products completed by each supported worker usable.

Results and Discussion

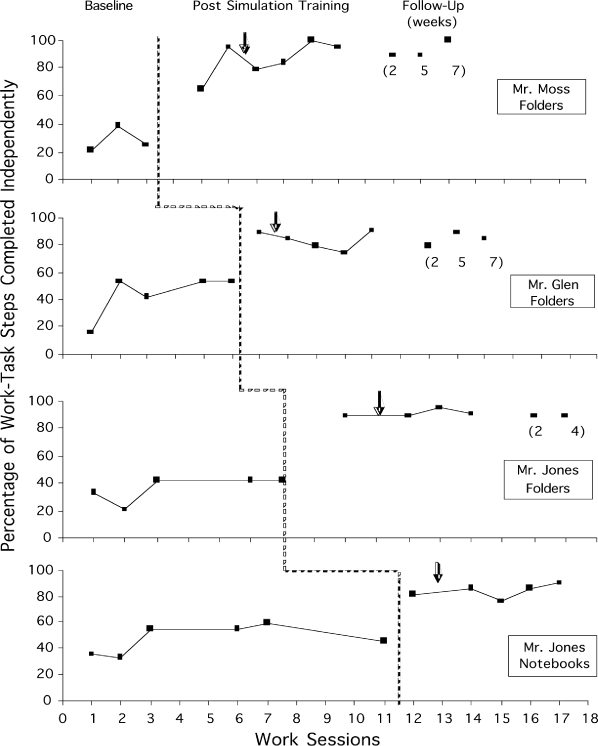

Figure 1 shows the percentage of job-task steps completed independently by each worker during observation probes at the job site. During baseline, each supported worker completed a relatively low percentage of work-task steps independently. In contrast, each worker showed immediate increases in performance after simulation training alone. All workers met the company-based criterion of 80% correctly completed steps on the first or second job-site observation. Subsequently, during the regular job routine, each worker maintained this performance. Follow-up observations (folder task only for Mr. Jones) across a 2- to 7-week period indicated that independent performance maintained except on one occasion for Mr. Glen (at 79%).

Figure 1.

Percentage of work steps completed independently by each worker during each observation probe at the job site before and after simulation training. Arrows indicate when a worker met the company-based, on-the-job performance criterion and began working in accordance with the regular job routine.

Results appear to provide further support for the utility of simulation training. These participants showed a substantial increase in independent job performance with newly assigned tasks when simulation training was provided prior to on-the-job training. Thus, workers with autism who initially receive simulation training at another (non-work) site may require less job-site training of new work skills.

Study 2

Similar to the work tasks in the Lattimore et al. (2006) study, the work tasks in Study 1 involved materials that could be easily transported to another site for simulation training. As discussed earlier, using the same materials in simulation training as used on the job likely enhanced generalization of newly acquired work skills from the simulation site to the job setting. We were interested in determining if similar results could be obtained when the materials used during simulation training were different than those needed for the actual job. Thus, in Study 2, the same individuals were taught new work tasks that required equipment that could not be transported to the simulation site. Hence, in contrast to Study 1 in which simulation training occurred in a different setting than the actual job but with the same materials and same job coach, the setting and job materials were different across the two sites and only the job coach remained the same.

Job Tasks, Observation System, and Interobserver Agreement

Each worker was taught to perform two new job tasks: cleaning sinks and mirrors in the company bathroom and washing cups in the break room. The former task consisted of 20 task-analyzed steps (e.g., pick up spray bottle, spray mirror left of center) and the latter consisted of 33 steps (e.g., put stopper in sink, adjust faucet over right side of sink). The definitions and observation system were identical to those described in Study 1. Interobserver agreement checks occurred during 30% of all probe observations for each supported worker and task. Overall agreement for independent task completion averaged 92% (range, 84% to 100%), occurrence agreement averaged 89% (range, 79% to 100%), and nonoccurrence agreement averaged 85% (range, 50% to 100%).

Procedures

The procedures described for Study 1 (baseline observation probes, simulation training, post-simulation training observation probes, regular job routine and follow-up) were replicated in Study 2 with the following exceptions. First, the materials used in the simulation training sessions were different than the materials used on the job. Simulation training involved the existing mirror and sink in a bathroom at the adult education site for the sink-and-mirror cleaning task, and coffee cups and a sink in the kitchen at that site for the cup-washing task. Additionally, the cleaning spray bottle and cleaning cloth that were used with the sink-and-mirror task at the simulation site were similar to but not the same as the materials used at the job site. The soap bottle and wash cloth that were used to wash cups at the simulation site were also similar but not identical to materials used at the job site.

The second exception was that only 3 training trials were conducted during each simulation session (compared to 10 trials in Study 1). Fewer trials were conducted because the tasks in Study 2 required more time to complete than those in Study 1. However, the criterion for completing simulation training (80% independent performance) was the same as in Study 1. For the sink-and-mirror cleaning task, Mr. Moss required 7 simulation sessions to reach criterion (conducted across 7 days), Mr. Glen required 8 (7 days), and Mr. Jones required 12 (12 days). For the cup-washing task, the 3 supported workers required 11, 2, and 5 simulation sessions (requiring 11, 2, and 5 days), respectively.

The third exception pertained to the post-simulation training phase at the job site. If a worker did not reach the 80% criterion after three post-simulation training observation probes, the regular job routine was then initiated. If the worker did not continue to improve with the regular job routine after several work sessions, two additional training trials were added to the regular job routine (i.e., cleaning the sink and mirror or washing cups in the sink three times instead of one time). For evaluation purposes, observational data were collected during the first trial as had occurred with preceding on-the-job sessions.

The effects of simulation training on job performance were evaluated by introducing the training at different points in time across participants and across each participant's two job tasks.

Results and Discussion

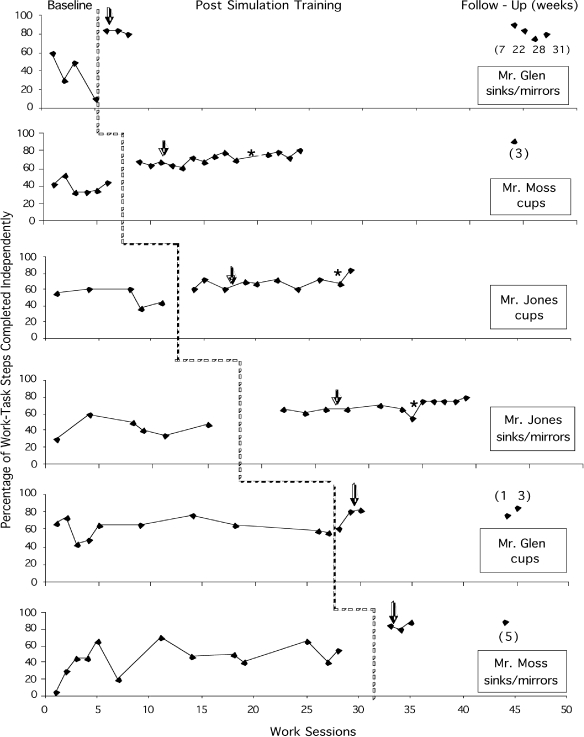

Figure 2 shows the percentage of work-task steps completed independently for each participant and work session. No supported worker performed the target tasks at criterion level during baseline, with averages across workers and tasks ranging from 38% to 62%. Following simulation training, all workers showed increased independent step completion on each target task within two job-site observation probes. However, the success of the training varied across workers and tasks. Mr. Glen met the on-the-job performance criterion on both tasks and then continued to complete the tasks at criterion level during the regular job routine with one exception (one session at 75% with the sink and mirror task). Mr. Moss met the criterion during the first post-simulation training probe with the sink and mirror task and then maintained at or above criterion during the regular job routine. With the cup-washing task, however, Mr. Moss did not meet the criterion until additional training trials were introduced into the regular job routine. Mr. Jones also required additional training trials during the regular job routine to reach the criterion level performance for both work tasks although his performance did improve above baseline after simulation training alone. Follow-up sessions conducted during the regular job routine (available for Mr. Glen and Mr. Moss only) indicated that the improved performance generally maintained across periods of 3 to 31 weeks.

Figure 2.

Percentage of work steps completed independently by each worker during each observation probe at the job site before and after simulation training. Arrows indicate when a worker began performing the task as part of the routine job and asterisks indicate when increased trials began on the job.

Results of Study 2 suggest that simulation training may be beneficial for supported workers with autism even when the work tasks require equipment that can not be transported to a simulation site for training. In several cases, simulation training alone was sufficient to promote criterion level performance on the job (both work tasks for Mr. Glen and one work task for Mr. Moss), even though the training involved materials and equipment that were different than those at the job site. Improved on-the-job performance also occurred in the other cases following simulation training, though not to criterion level (one work task for Mr. Moss and both tasks for Mr. Jones).

Conclusions and Guidelines for Practice

Results of both studies offer support for the utility of simulation training with adults who have severe autism and suggest several guidelines for practitioners in the supported work area. The most apparent guideline is that, to enhance on-the-job performance of the new work duties, simulation training should be provided when feasible before supported workers begin the new duties. Providing simulation training prior to initiating new work duties should result in less time having to be devoted to training work skills on the job. As such, simulation training could help resolve the common problem in supported jobs involving people with severe disabilities in which either the expected amount of work is not completed (due to time spent in training) or job coaches perform the work for the supported workers (Parsons, Reid, Green, & Browning, 1999).

Results of this investigation also suggest a more comprehensive guideline for practitioners. Close attention should be given to existing evidence behind what is considered best practices in supported work for people with severe disabilities. Currently, best practices recommend against simulation training away from actual job sites (Wehman et al., 2007; White & Weiner, 2004). Recommended practice is not always based on research-based evidence, however, and current approaches for attempting to involve adults with severe disabilities in supported work warrant scrutiny. Despite the intention of the supported work movement to involve people with severe disabilities in community jobs, in large part this population has not been included in supported work placements relative to adults with less serious disabilities. Relying on practices that are derived from research findings in contrast to, for example, practices that may be currently popular but do not have an underlying research base, is more likely to result in successful outcomes in supported work. Use of simulation training would seem to represent one research-based alternative to currently recommended practices that could enhance performance in community jobs.

In considering the use of simulation training as just summarized, care should be taken to avoid problems that have historically been associated with training work skills in settings separate from actual jobs. One reason for the exclusion of such training from popularly recommended practice is that many individuals with severe disabilities who receive job-related training in segregated or sheltered sites never advance to placements in community jobs (Reid & Green, 2007). That is, such training either did not promote generalization of skills to real jobs or the placement in a simulated setting was essentially seen as an acceptable outcome in and of itself. A guideline stemming from this investigation is to use simulation training to enhance skill acquisition relevant to performing in an actual job placement, not providing simulation training independently of having a real job (see also Lattimore et al., 2006).

Another guideline when working with adults with severe autism in supported work is to pay close attention to variables affecting generalization from simulated settings to community jobs. Results of the two studies here suggest that the benefits of simulation training may be reduced if the simulation training setting and the job setting share fewer common stimuli. Although the somewhat differing results across the two studies may have been due to other variables (e.g., differences in the difficulty of the jobs across the studies), the results are consistent with previous behavior analysis research for promoting generalization across settings. Consequently, it is recommended to incorporate as many stimuli from the job site into simulation training as is possible (e.g., use similar materials and equipment). Following this and the other research-based guidelines noted are likely to assist adults with autism and possibly other severe disabilities to experience more success in supported work.

Footnotes

Requests for reprints should be addressed to Dennis H. Reid, Carolina Behavior Analysis and Support Center, P. O. Box 425, Morganton NC 28680.

Contributor Information

Marsha B Parsons, J. Iverson Riddle Center.

Dennis H Reid, Carolina Behavior Analysis and Support Center, Morganton, North Carolina.

References

- Cimera R. E. The monetary benefits and costs of hiring supported employees: Revisited. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation. 2006;24:137–144. [Google Scholar]

- Conley R. W. Maryland issues in supported employment. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation. 2007;26:115–121. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Iriarte E, Balcazar F, Taylor-Ritzler T. Analysis of case managers' support of youth with disabilities transitioning from school to work. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation. 2007;26:129–140. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes D. L. The years ahead: Adults with autism. In: Powers M. D, editor. Children with autism: A parent's guide. Bethesda, MD: Woodbine House; 2000. pp. 279–302. (Ed.) [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson J. W, Holburn S. History and current status of applied behavior analysis in developmental disabilities. In: Matson J. L, Laud R. B, Matson M. L, editors. Behavior modification for persons with developmental disabilities: Treatments and supports. Kingston, NY: National Association for the Dually Diagnosed; 2004. pp. 1–32. (Eds.) [Google Scholar]

- Lattimore L. P, Parsons M. B, Reid D. H. Enhancing job-site training of supported workers with autism: A re-emphasis on simulation. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2006;39:91–102. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2006.154-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClannahan L. E, MacDuff G. S, Krantz P. J. Behavior analysis and intervention for adults with autism. Behavior Modification. 2002;26:9–26. doi: 10.1177/0145445502026001002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsmond G. I, Krauss M. W, Seltzer M. M. Peer relationships and social and recreational activities among adolescents and adults with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2004;34:245–256. doi: 10.1023/b:jadd.0000029547.96610.df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons M. B, Reid D. H, Green C. W, Browning L. B. Reducing individualized job coach assistance provided to persons with multiple severe disabilities in supported work. Journal of The Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps. 1999;24:292–297. [Google Scholar]

- Reid D. H, Green C. W. Systematic instruction for applied behavior analysis. In: Wehman P, Inge K. J, Revell W. G, Brooke V. A, editors. Real work for real pay: Inclusive employment for people with disabilities. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes; 2007. pp. 163–177. (Eds.) [Google Scholar]

- Repp A. C, Favell J, Munk D. Cognitive and vocational interventions for school-age children and adolescents with mental retardation. In: Jacobson J. W, Mulick J. A, editors. Manual of diagnosis and professional practice in mental retardation. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1996. pp. 265–276. (Eds.) [Google Scholar]

- Stokes T. F, Baer D. M. An implicit technology of generalization. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1977;10:349–367. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1977.10-349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehman P, Brooke V. A, Revell W. G. Inclusive employment: Rolling back segregation of people with disabilities. In: Wehman P, Inge K. J, Revell W. G, Brooke V. A, editors. Real work for real pay: Inclusive employment for people with disabilities. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes; 2007. pp. 3–18. (Eds.) [Google Scholar]

- White J, Weiner J. S. Influence of least restrictive environment and community based training on integrated employment outcomes for transitioning students with severe disabilities. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation. 2004;21:149–156. [Google Scholar]