Abstract

Natural killer (NK) cell alloreactivity, which may contribute to the graft-versus-leukemia effect of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), is influenced by the interaction of killer-cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIRs) on donor NK cells and their ligands, human leukocyte antigen (HLA) Class I molecules on recipient antigen-presenting cells. Distinct models to predict NK cell alloreactivity differ in their incorporation of information from typing of recipient and donor KIR and HLA gene loci, which exist on different autosomes and are inherited independently as haplotypes. Individuals may differ in the inheritance of the two KIR haplotypes, A and B, or in the expression of individual KIR genes. Here, we examined the effect of KIR and HLA genotype, in both the recipient and donor, on the outcome of 86 patients with advanced hematologic malignancies who received nonmyeloablative, HLA-haploidentical HSCT with high-dose, post-transplantation cyclophosphamide (Cy). Compared to recipients of marrow from donors with identical KIR gene content, recipients of inhibitory KIR (iKIR) gene-mismatched marrow had an improved overall survival (HR=0.37; CI: 0.21- 0.63; p=0.0003), event-free survival (HR=0.51; CI: 0.31- 0.84; p=0.01), and relapse rate (cause specific hazard ratio, SDHR=0.53; CI: 0.31-0.93; p=0.025). Patients homozygous for the KIR “A” haplotype, which encodes only one activating KIR, had an improved overall survival (HR=0.30; CI: 0.13-10.69; p=.004), event-free survival (HR=0.47; CI: 0.22-1.00; p=.05) and non-relapse mortality (NRM; cause specific HR=0.13; CI: 0.017-0.968; p=0.046) if their donor expressed at least one KIR B haplotype, which encodes several activating KIRs. Models that incorporated information from recipient HLA typing, with or without donor HLA typing, were not predictive of outcome in this patient cohort. Thus, nonmyeloablative conditioning and T cell-replete, HLA-haploidentical HSCTs involving iKIR gene mismatches between donor and recipient, or KIR haplotype AA recipients of marrow from KIR Bx donors, were associated with lower relapse and NRM and improved overall and event-free survival. These findings suggest that selection of donors based upon inhibitory KIR gene or haplotype incompatibility may be warranted.

Introduction

Alloreactive natural killer (NK) cells have been shown to play a significant role in the outcomes of patients with hematologic malignancies after hematopoeitic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). The molecular basis of NK cell alloreactivity is incompletely understood, but it is known to involve a dynamic balance of signals mediated through activating as well as inhibitory receptors on the NK cell. Killer cell Immunoglobulin-like Receptors (KIRs), consisting of inhibitory and activating groups, are expressed on NK cells as well as on a subset of T cells. Some of the inhibitory KIRs, or iKIRs, recognize specific HLA class I ligands including the well-defined specificity of KIR2DL2/3 for the HLA-Cw group-1 epitope, the specificity of 2DL1 for the Cw group-2 epitope, and the specificity of 3DL1 for the HLA Bw4 epitope [1].

KIR genes segregate independently of HLA genes, such that matching for HLA does not match for KIRs. The KIR genes are clustered together on chromosome 19q13.2 and, like the HLA genes, are inherited together as a haplotype [2]. Two distinct haplotypes exist, groups A and B, varying in the type and number of genes present. The KIR group A haplotype is uniform in terms of gene content (3DL3, 2DL3, 2DL1, 2DP1, 3DP1, 2DL4, 3DL1, 2DS4, and 3DL2), of which all but one encode inhibitory receptors. In contrast, the KIR group B haplotype is more diverse in the KIR genes it contains, has more activating receptors, and is characterized by the 2DL2, 2DS1, 2DS2, 2DS3, and 2DS5 genes [2]. Individual KIR genes are highly polymorphic [3], second in polymorphism only to the HLA genes. The functional significance of KIR gene polymorphism is not yet known, and most studies of the contribution of KIR genes to NK cell alloreactivity do not distinguish individual KIR gene alleles.

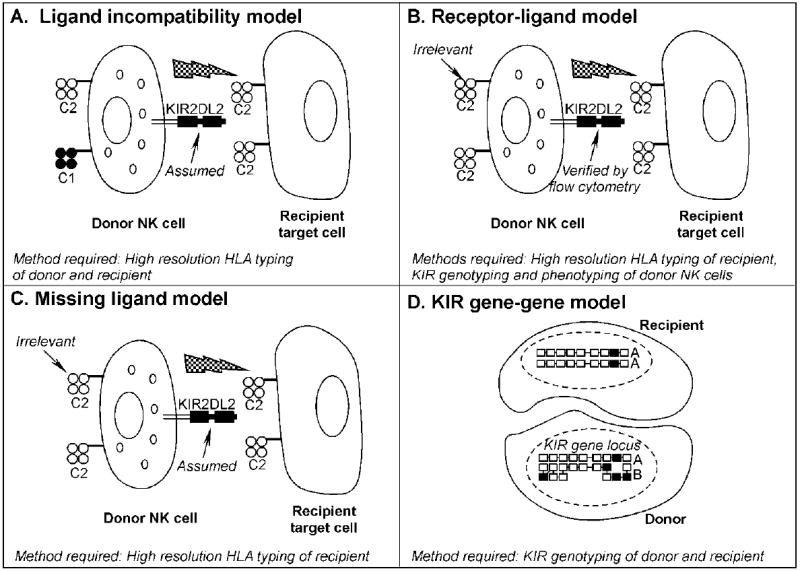

In the setting of allogeneic HSCT, donor NK cells may attack recipient cells that lack the appropriate HLA class I ligands for the donor iKIR. After allogeneic HSCT, NK cells are the first lymphocyte subset to reconstitute peripheral blood [4-6]. While some studies have demonstrated a beneficial effect of NK cell alloreactivity on HSCT outcomes [5,7-10], others have shown inferior rates of relapse and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) [11,12], and still others have reported that NK cell alloreactivity has no effect on HSCT outcomes [10,13]. Reasons for these conflicting results include the heterogeneity in HSCT protocols employed, namely differences in inclusion criteria, the HSCT preparative regimen and graft content, the degree of donor HLA-incompatibility, and post-transplant immunosuppression. At least four models of NK cell alloreactivity (Figure 1) have been proposed to predict HSCT outcomes: 1) KIR ligand incompatibility, or ligand-ligand model [7,11,14-16] (Figure 1A); 2) receptor-ligand model [9] (Figure 1B); 3) missing ligand model [5,8] (Figure 1C); and 4) KIR gene-gene model [10,13] (Figure 1D). Contradictory results obtained from these models have made it difficult to conclude which model is most predictive of transplant outcome.

Figure 1.

Models of natural killer cell alloreactivity after allogeneic cell transplantation. A. The KIR ligand incompatibility, or ligand-ligand model predicts NK cell alloreactivity in the GVH direction (depicted by jagged arrow) when the recipient lacks expression of an inhibitory KIR ligand, in this case a member of the HLA-C1 group, that is present in the donor. This model assumes the presence of functional donor NK cells expressing KIR2DL2, the receptor for HLA-C1 molecules, as their inhibitory receptor. B. The receptor-ligand model predicts NK cell alloreactivity in the GVH direction when the recipient lacks the expression of an HLA ligand for a verified donor inhibitory KIR. The HLA type of donor cells is not considered in this model. C. The missing ligand model predicts NK cell alloreactivity in the GVH direction when recipient cells lacks expression of at least one of the HLA ligands (C1, C2, or –Bw4) for a verified donor inhibitory KIR. As in B., the HLA type of the donor is not considered in this model. D. The KIR gene-gene model predicts NK alloreactivity when the donor and recipient are mismatched for KIR gene content. This model characterizes the KIR genotype of both donor and recipient and asks whether differences in the expression of individual inhibitory or stimulatory genes between the donor and the recipient KIR (i.e. donor includes inhibitory KIR genes that the recipient is missing or vice versa) have any effect on the outcome of allogeneic SCT. Inhibitory KIR genes are shown here as unshaded boxes, whereas black boxes represent activating KIR genes. In the example shown, the donor has several activating and inhibitory genes that the recipient lacks. This example also illustrates the KIR haplotype characterization. In this case, the donor is haplotype group B, based on the presence of several activating KIR genes, while the recipient is haplotype group A based on the presence of inhibitory genes and only one activating gene.

To evaluate the impact of KIR mismatches on HSCT outcome measures, we performed a retrospective study of 86 patients with high-risk hematologic malignancies who had been transplanted between 1999 and 2007 with T-replete bone marrow from haploidentical donors after nonmyeloablative conditioning with a novel post-transplantation immunosuppressive regimen including post-transplantation cyclophosphamide (Cy). Using three of the four models (ligand incompatibility, missing-ligand, and gene-gene models) we determined that donor-recipient inhibitory KIR gene-gene mismatches as well as KIR haplotype group A recipients of B donors have improved clinical outcomes. Because most patients have multiple potential haploidentical donors, this might allow optimal donor selection to improve BMT outcome.

Patients

The study population consisted of 86 consecutive patients who were enrolled on one of two similar clinical trials, J9966 (Phase I) and J0457 (Phase II) at Johns Hopkins between 1999 and 2007. The primary outcomes of 40 of these patients have been reported previously [17]. Utilizing the models of NK cell alloreactivity, the outcomes of these 40 patients and an additional 46 consecutively enrolled patients have been included here. Eligible patients were 0.5-70 years of age, with high-risk hematologic malignancies as previously described [17] for whom standard allogeneic (HLA-matched, related or unrelated) or autologous BMT was unavailable or inappropriate. The protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions. All patients signed consent forms approved by the Institutional Review Board.

HLA and KIR typing

HLA typing prior to alloBMT was performed as previously reported [17]. The presence or absence of KIR genes was determined using PCR sequence- specific amplification from genomic DNA extracts prepared by an automated procedure using the GENOM™-4 (Genovision Cytomics, Exton, PA). KIR genes/allele groups were amplified using specific primer sets (Pel-Freez, Dynal Biotech, Oslo, Norway) for the KIR genes recognized by the international nomenclature committee of the World Health Organization [1]. The KIR amplicons were visualized with ethidium bromide after agarose gel electropheresis.

Potential KIR alloreactivity was assessed by three of the four models described previously: ligand incompatibility, missing ligand and gene-gene models. High resolution HLA typing was used to assign donor and recipient alleles of HLA-B and HLA-C to iKIR ligand groups [14,18] and to determine donor/recipient iKIR ligand compatibility. An iKIR gene-gene mismatch was defined as an iKIR gene that was present in the donor but absent in the recipient, or vice versa. The KIR haplotype model was used to categorize all donors and recipients as having one of two KIR genotypes: AA which is homozygous for group A KIR haplotypes, or Bx, which contains either one (AB) or two (BB) group B haplotypes. The inheritance of at least one B haplotype was determined by the expression of specific activating KIR genes and one inhibitory KIR as determined by the gene-gene model that are not components of the group A haplotypes.

Conditioning regimen and postgrafting immunosuppression (Fig. 2)

Figure 2.

Nonmyeloablative haploidentical BMT conditioning and postgrafting immunosuppresive regimen.

Patients on the two protocols were treated according to the previously published regimens [17] described in Figure 2, which differed in terms of postgrafting immunosuppression. Patients treated on J9966 received either one dose of post-transplantation Cy and twice daily mycophenolate mofetil (MMF; Cellcept®, Roche Laboratories, Nutley, NJ) (Hopkins A; n=20) or two doses of post-transplantation Cy (Hopkins B; n=40) and thrice daily MMF. Patients on J0457 received two doses of post-transplantation Cy and thrice daily MMF (n=26). All patients were intended to be treated as outpatients. Pharmacologic prophylaxis of GVHD was initiated on the day following completion of post-transplantation Cy. Acute GVHD was graded according to the Keystone Criteria [19]. First-line therapy for clinically significant acute GVHD consisted of methylprednisolone 1-2.5 mg/kg/day IV plus full-dose tacrolimus or full-dose tacrolimus plus resumption of MMF.

Statistical methods

Patient outcomes were updated most recently on December 8, 2008. A description of protocol specific phase I and II parameters for J9966 Hopkins A and B, and for J0457 has been previously published [17]. Probabilities of overall and event-free survival were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method [20] and compared using the log-rank statistic [21] or the Cox proportional hazards regression model [22]. Stratified Cox regression models were used to obtain KIR mismatch multivariate estimates specific for lymphoid and myeloid disease types by including stratum-covariate interaction effects. Probabilities of acute and chronic GVHD, relapse, and NRM were summarized using cumulative incidence estimates [23]. Death without engraftment was considered a competing risk for engraftment; death with relapse was a competing risk for relapse; relapse was a competing risk for NRM; graft failure, relapse, or death without GVHD was considered competing risks for GVHD. The hazard of failure for each of these endpoints was compared using proportional subdistribution hazard regression models for competing risks endpoints [24,25]. All p values are two-sided and all confidence intervals (CIs) are 95% CIs. Computations were performed using the Statistical Analysis System, or R.

Results

Patient and graft characteristics

Characteristics of the 86 patients enrolled in the studies are listed in Table 1. All study subjects had poor-risk hematologic malignancies, as previously defined [17]. Eighteen percent of the patients were from ethnic minority groups.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| No. Patients | 86 |

| Median Age, yr (range) | 48 (1-71) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 52 (60) |

| Female | 34 (40) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Caucasian | 70 (82) |

| African American | 14 (16) |

| Asian | 2 (2) |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | |

| AML | 25 (30) |

| ALL | 7 (8) |

| MDS | 8 (9) |

| CML/CMML | 11 (13) |

| CLL | 8 (9) |

| HL | 7 (8) |

| NHL | 14 (16) |

| MM/Plasmacytoma | 6 (7) |

Abbreviations: AML, acute myeloid leukemia; ALL, acute lymphocytic leukemia; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; CML, chronic myelogenous leukemia; CMML, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; HL, Hodgkin lymphoma; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; MM, multiple myeloma

Characteristics of the donors and grafts are listed in Table 2. The numbers of HLA allele mismatches in the host-versus-graft (HVG) or graft-versus-host (GVH) directions are listed. Donors differed from their recipients at a median of four HLA loci in both the HVG and GVH directions. More than 50% of donor-recipient pairs were mismatched for at least 4 HLA loci.

Table 2.

Donor and Graft Characteristics (n=86)

| Median Age, yr (Range) | 44 (21-69) | |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 40 (47) | |

| Female | 46 (53) | |

| Relationship, n (%) | ||

| Parent | 23 (27) | |

| Sibling | 43 (50) | |

| Child | 20 (23) | |

| CD3+ cells/kg × 10-7 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 3.8 (1.3) | |

| CD34+ cells/kg × 10-6 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 4.3 (1.7) | |

| Infused MNC/kg × 10-8 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 1.5 (0.9) | |

| HLA Mismatches1, n (%) | HvG Direction | GvH Direction |

| 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| 1 | 3 (4) | 4 (5) |

| 2 | 8 (10) | 8 (10) |

| 3 | 22 (28) | 24 (31) |

| 4 | 31 (40) | 34 (44) |

| 5 | 13 (17) | 7 (9) |

| Median (Range) | 4 (0-5) | 4 (0-5) |

Abbreviations: MNC, mononuclear cell count; HvG, host-versus- graft; GvH, graft-versus-host; SD, standard deviation

n=78

KIR Mismatches

The ligand incompatibility model predicted the lowest frequency of NK alloreactive donors, (26/86, 30%), only about half as many as predicted by the other methods: missing ligand model (57/84, 68%) and the gene-gene model for inhibitory KIR (49/85, 58%). Of 85 evaluable patients, 30 had KIR haplotype mismatches (AA donor into Bx recipient, 10/85, [12%], and Bx donor into AA recipient, 20/85, [24%]); the remaining 55 recipient-donor pairs (65%) were haplotype-compatible (AA donor into AA recipient, 15/85, [18%], and Bx donor into Bx recipient, 40/85, [47%]).

Acute GVHD, Non-relapse Mortality (NRM), Relapse, Overall survival (OS), and Event Free Survival (EFS)

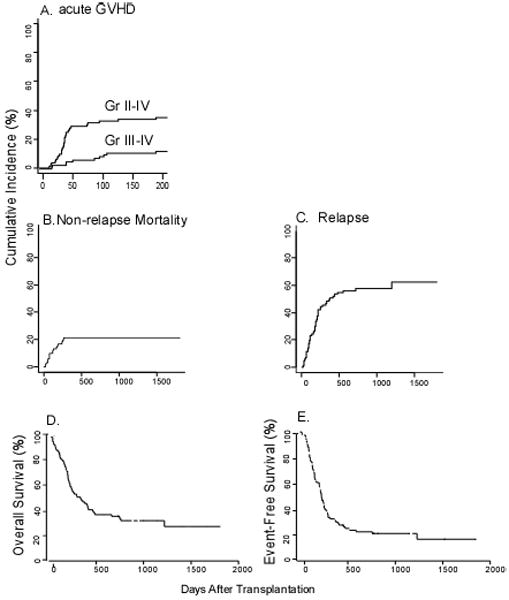

The probabilities of grades II-IV and III-IV acute GVHD by day 100 were 33% and 8% and by day 200 were 35% and 12%, respectively (Fig. 3A). The cumulative incidences of NRM at 100 days and at 1 year after transplantation were 9% and 21%, respectively (Fig 3B), and the probabilities of relapse at 1 and 2 years after transplantation were 50% and 58%, respectively (Fig 3C). There was no difference in relapse rate between those patients with lymphoid and myeloid malignancies (cause specific HR=1.03; CI: 0.59-1.8; p=0.91).

Figure 3.

Overall outcomes among nonmyeloablative haploidentical BMT recipients. Cumulative incidence of (A) acute GVHD, grades II-IV and III-IV. (B) Non-relapse mortality. (C) Relapse. (D) Overall survival. (E) Event-free survival.

At a median follow-up among survivors of 916 days (range, 112-1808 days), the actuarial overall survivals at 1 and at 2 years after transplantation were 46% and 34%, respectively (Fig 3D). The actuarial EFS at 1 and at 2 years were 30% and 23%, respectively (Fig 3E). In univariate analysis, OS and EFS were significantly higher in patients whose donors were more mismatched in the GVH direction (4-5 mismatches versus 1-3 mismatches, HR=0.5; CI: 0.29-0.86; p=0.01 and HR 0.5; CI: 0.3-0.84; p=0.01). There was no statistically significant difference in any outcome between the groups of patients who received one versus two doses of post-transplantation Cy (data not shown).

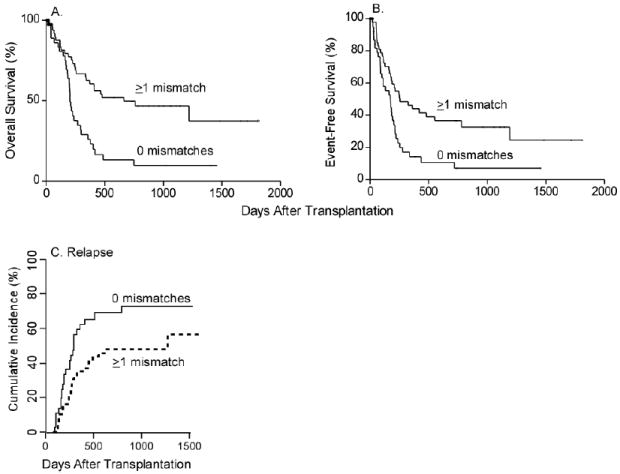

Inhibitory KIR Gene Mismatches

Donor/recipient pairs who differed in iKIR gene content had a significantly improved OS (HR=0.37; CI: 0.21-0.63; p=0.0003) and EFS (HR=0.51; CI: 0.31-0.84; p=0.01) (Figure 4 A,B) when compared to those patient-donor pairs with identical iKIR gene content. The overall survival benefit of iKIR gene mismatches was found in patients with lymphoid diseases (HR=0.44; CI: 0.20-0.93; p=0.03) as well as in patients with myeloid diseases (HR=0.32; CI: 0.15-0.69, p=0.004). Furthermore, patient-donor pairs with inhibitory KIR gene mismatches had a lower rate of relapse than those without mismatches (cause specific HR=0.53; CI: 0.31-0.93; p=0.025) (Figure 4C). There was no significant difference in NRM between those patient-donor pairs with inhibitory KIR mismatches as compared to those without (cause specific HR=0.95; CI: 0.36-2.52; p=0.92). To explore further the influence of inhibitory KIR mismatches on OS and EFS, a multivariate analysis was performed with disease type (myeloid versus lymphoid), number of HLA mismatches in the GVH and HVG direction, graft CD3 count, CMV status, and one versus two doses of post transplant Cy as candidate predictors. In the final model adjusting for HLA allele mismatches, the benefit of inhibitory KIR gene mismatching on OS and EFS remained significant (HR 0.4; CI: 0.23-0.71; p=0.002 and HR 0.51; CI: 0.3-0.87; p=0.01, respectively) (Table 3A,D). When performing a multivariate analysis for OS and EFS stratified by disease type (myeloid versus lymphoid), patients with lymphoid disease and inhibitory KIR mismatches had an improved OS (Table 3B; HR 0.41; CI: 0.18-0.93; p=0.03) with a trend towards an improved EFS (Table 3E; HR 0.54; CI: 0.25-1.16; p=0.11), while those patients with myeloid disease and inhibitory KIR mismatches had an improved OS and EFS (HR 0.34; CI: 0.15-0.77; p=0.01 and HR=0.47; CI: 0.22-0.98; p=0.05) (Table 3 B,E). There were no significant differences in acute or chronic GVHD, NRM, or engraftment failure between patient-donor pairs with or without inhibitory KIR genotype mismatches (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Gene-gene inhibitory KIR mismatches and overall survival, event free-survival, and relapse (A) Overall Survival (OS). (B) Event-Free Survival (EFS). (C) Cumulative incidence of relapse.

Table 3.

Overall and Event-free survival: Multivariate Analysis

| A. Overall Survival and inhibitory KIR gene mismatches | |||

| HR | 95% CI | P | |

| Inhibitory KIR gene mismatches | 0.4 | 0.23-0.71 | 0.002 |

| ≥ 4 HLA allele mismatches (GVH) | 0.58 | 0.34-1.02 | 0.06 |

| B. Overall Survival and inhibitory KIR gene mismatches stratified by disease type | |||

| HR | 95% CI | P | |

| Inhibitory KIR gene mismatches (lymphoid) | 0.41 | 0.18-0.93 | 0.03 |

| Inhibitory KIR gene mismatches (myeloid) | 0.34 | 0.15-0.77 | 0.01 |

| ≥ 4 HLA allele mismatches (GVH) | 0.53 | 0.3-0.94 | 0.03 |

| Age >50 | 1.56 | 0.88-2.77 | 0.13 |

| C. Overall Survival and Haplotype | |||

| HR | 95% CI | P | |

| Bx donor to AA recipient | 0.35 | 0.14-0.85 | 0.02 |

| ≥ 4 HLA allele mismatches (GVH) | 0.53 | 0.3-0.93 | 0.03 |

| Age >50 | 1.45 | 0.83-2.55 | 0.19 |

| Lymphoid malignancy | 1.11 | 0.64-1.94 | 0.71 |

| AA donor to Bx recipient | 0.36 | 0.12-1.03 | 0.06 |

| Bx donor to Bx recipient | 0.53 | 0.27-1.06 | 0.07 |

| D. Event-Free Survival and inhibitory KIR gene mismatches | |||

| HR | 95% CI | P | |

| Inhibitory KIR gene mismatches | 0.51 | 0.3-0.87 | 0.01 |

| ≥ 4 HLA allele mismatches (GVH) | 0.57 | 0.33-0.96 | 0.03 |

| E. Event-free survival and inhibitory KIR gene mismatches stratified by disease type | |||

| HR | 95% CI | P | |

| Inhibitory KIR gene mismatches (lymphoid) | 0.54 | 0.25-1.16 | 0.11 |

| Inhibitory KIR gene mismatches (myeloid) | 0.47 | 0.22-0.98 | 0.05 |

| ≥ 4 HLA allele mismatches (GVH) | 0.52 | 0.3-0.89 | 0.02 |

| Age >50 | 1.48 | 0.86-2.53 | 0.15 |

| F. Event-free survival and haplotype | |||

| HR | 95% CI | P | |

| Bx donor to AA recipient | 0.49 | 0.21-1.14 | 0.1 |

| ≥ 4 HLA allele mismatches (GVH) | 0.54 | 0.31-0.93 | 0.03 |

| Age >50 | 1.47 | 0.86-2.51 | 0.16 |

| Lymphoid malignancy | 1.06 | 0.63-1.79 | 0.82 |

| AA donor to Bx recipient | 0.8 | 0.32-2.03 | 0.64 |

| Bx donor to Bx recipient | 0.71 | 0.36-1.38 | 0.31 |

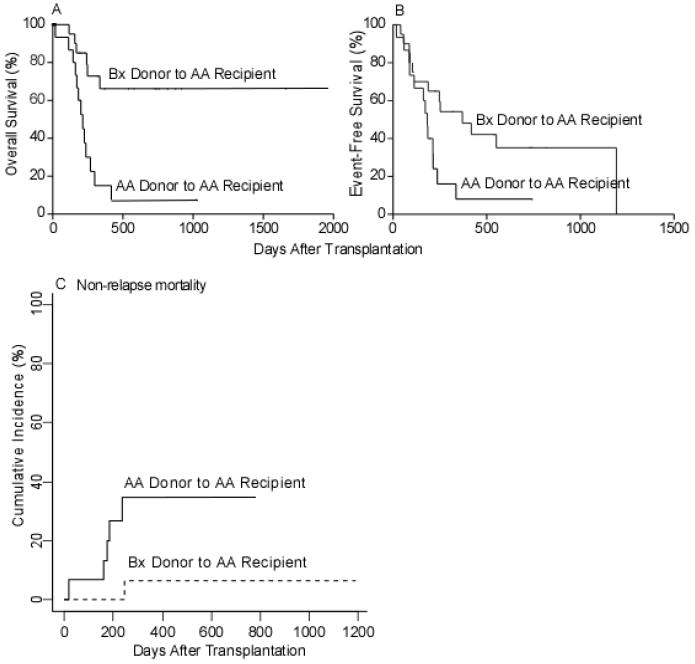

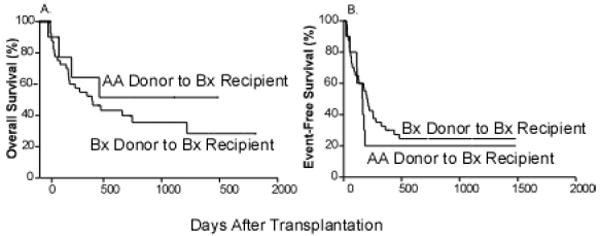

Haplotype Mismatches

Patients and donors were classified as either having genotype AA or Bx, as described in the Methods section. Since the recipient’s KIR haplotypes are fixed but donors can be selected based upon KIR haplotype, we analyzed the effect of donor KIR haplotype on the outcome of SCT. Patients with the AA haplotype had a significantly improved OS (HR=0.30; CI: 0.13-0.71; p=0.01) and EFS (HR=0.47; CI: 0.22-1.00; p=.05) if their donor had a Bx haplotype (mismatched) rather than an AA haplotype (matched) (Figure 5A,B). AA recipients of marrow from Bx donors also had a lower NRM (HR=0.13; CI: 0.017-0.968; p=0.046) (Figure 5C). No effect was seen on relapse rate (HR 1.05, CI: 0.44-2.51; p=0.91). To explore further the influence of donor KIR haplotypes, a multivariate analysis was constructed adjusted for significant clinical and demographic factors including age, disease status, and number of HLA allele mismatches in the GVH direction. After adjustment, the benefit of transplantation on OS using haplotype B donors for haplotype A recipients remained significant (Table 3C; HR 0.35; CI: 0.14-0.85; p=0.02) and marginally significant for EFS (Table 3F; HR 0.49; CI: 0.21-1.14; p=0.1).

Figure 5.

Overall survival, event free-survival, and non-relapse mortality for haplotype A recipients of B donors (A) Overall survival. (B) Event-Free survival. (C) Cumulative incidence of non-relapse mortality

For patients with haplotype Bx, there was no difference in OS or EFS based on donor haplotype (HR=0.69; CI: 0.27-1.78; p=0.44 and HR=1.28; CI: 0.58-2.80, p=0.54, respectively) (Figure 6A, B). There were no significant differences in relapse, engraftment failure, acute or chronic GVHD based on donor-recipient haplotype combinations (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Overall and event free-survival for haplotype B recipients of A donors (A) Overall survival. (B) event-free survival.

Other Models

When we utilized the other proposed models (ligand-incompatibility, missing ligand, and gene-gene for stimulatory KIR), we saw no significant differences in any patient outcomes (data not shown). Patient-donor pairs with stimulatory KIR gene mismatches did show a trend toward an improved overall survival (HR=0.59; CI: 0.34-1.00; p=0.05), and those with receptor-ligand mismatches did show a trend toward a significant increase in aGVHD (cause specific HR=2.18; CI: 0.914-5.20; p=0.08).

Discussion

In this nonmyeloablative haploidentical HSCT study utilizing T-cell replete grafts and a novel post-transplantation immunosuppressive regimen including Cy for high-risk, poor-prognosis hematologic malignancy patients, we found that regardless of disease type, patient-donor pairs with inhibitory KIR gene mismatches had improved OS, EFS, and a lower rate of relapse. Additionally, we found that KIR genotype AA transplant recipients of KIR genotype Bx donors (Bx→AA) had an improved OS, EFS, and significantly lower non-relapse mortality. Since most patients have multiple potential haploidentical donors, this might allow for optimal donor selection to improve outcomes after T cell replete haploidentical BMT.

These results are particularly noteworthy because our regimen included T-cell replete grafts. T-cell depletion is thought to facilitate NK-cell recovery and perhaps NK alloreactivity [26], and the majority of work identifying a benefit of NK cell alloreactivity in the haploidentical setting has been done with T-cell depleted grafts [11,14,27-29]. Furthermore, the benefit of NK alloreactivity has been demonstrated predominantly after HSCTs that have not included post-transplantation immunosuppressive agents, unlike our novel regimen that includes post-transplantation Cy, MMF, and tacrolimus. It is possible that post-transplantation Cy eliminates the recently activated T cells responsible for interfering with effective NK cell reconstitution and alloreactivity. It is also possible that the benefit of KIR mismatches in prior studies using T cell replete grafts was outweighed by higher rates of GVHD and thus higher rates of NRM, and that the elimination of host-reactive T cells by post-transplantation Cy unmasks the benefit of KIR genotype and haplotype mismatches. Further laboratory studies to look at the mechanism of Cy-induced T cell tolerance and characterize NK cell reconstitution after this transplant regimen are ongoing.

A benefit of iKIR gene mismatching, as is seen most clearly in Figure 4, implies that donor NK cell alloreactivity depends upon the iKIR gene repertoire of the recipient. We can envision two possibilities for how recipient iKIR genes, via the NK or T cells that express them, can influence donor NK and/or T cell alloreactivity. First, allelically variable peptide sequences from recipient iKIR molecules may be presented by recipient HLA Class I molecules, thereby acting as minor histocompatibility antigens to stimulate a graft-versus-tumor response from donor T cells. A second possibility is that, prior to transplantation, the relative expression of HLA Class I alleles on tumor cells is selected by recipient NK cells and their iKIRs to levels that permit the tumor to escape recipient NK cell cytotoxicity. However, this level of HLA Class I molecule expression, which has effectively been “imprinted” by recipient NK cells, may not be optimally tuned to avoid donor NK cell killing, thereby leading to an enhanced NK cell-mediated graft-versus-tumor effect.

Previous studies have examined the effect of donor and recipient KIR genotypes on the outcome of allogeneic HSCT [13,30,31]. One study found a 100% risk of GVHD after unrelated donor BMT when the donor contained KIR genes absent in the recipient, as compared to a 60% risk of GVHD with other combinations [13]. Another study has shown significantly higher rates of graft rejection in KIR genotype identical versus mismatched BMTs [32]. The presence of specific KIR genes has also been shown to influence the prognosis of or modulate certain autoimmune and infectious diseases [33-37].

Previous studies have also shown a benefit of transplants from Bx donors [38,39]. In the setting of T cell-replete, HLA-matched sibling BMT involving CMV positive recipients and their CMV positive donors, recipients of haplotype B donors had only a 24% rate of CMV reactivation, whereas recipients of haplotype A donors had a 71% rate of CMV reactivation [40]. These results had not previously been shown with HLA-haploidentical donor BMT involving T-cell depletion, suggesting that the protective effect of donor CMV-specific cells might depend upon the KIR genotype/haplotype of the donor and the presence of donor lymphocytes at the time of transplantation. In another study, AML recipients of grafts from KIR haplotype B donors had a significantly improved EFS secondary to a markedly reduced NRM after T cell-depleted, HLA-haploidentical HSCT [41]. In agreement with Cooley et al., despite the benefit of haplotype Bx donors for A recipients, we did not observe a benefit from increased numbers of activating KIR genes or the presence of KIR2DS2 in the donor [39]. Likewise, we did not find any significant effect on outcome from the presence of KIR2DS1 and 2DS2 in the donor, or donors with more than four activating KIRs as has been previously shown [30,39,42].

In contrast to our study, detrimental effects of activating or haplotype B donors have also been reported [31,43]. In HLA-matched related BMTs, the presence of activating KIR, or haplotype B donors, has been correlated with increased rates of aGVHD [31] and relapse [43] in patients with myeloid malignancies.

Although the underlying mechanisms are still unclear, our results suggest that donor/recipient mismatches of inhibitory KIR genes or specific KIR gene haplotypes are associated with improved OS and EFS after T cell-replete, HLA-haploidentical bone marrow transplantation with post-transplantation cyclophosphamide for hematologic malignancies. We are currently investigating whether donor and recipient KIR genes influence the outcome of T cell-replete, HLA-haploidentical SCT with post-transplantation Cy after myeloablative conditioning. Since KIR genotyping is simple, dependable, and relatively inexpensive, the prospective selection of KIR mismatched donors to improve HSCT outcomes remains a promising and feasible goal.

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible by Grant Number 1KL2RR025006-01 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR or NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Marsh SGE, Parham P, Dupont B, et al. Killer-cell Immunoglobulin-like Receptor (KIR) Nomenclature Report, 2002. Human Immunology. 2003;64:648–654. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(03)00067-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uhrberg M, Valiante NM, Shum BP, et al. Human Diversity in Killer Cell Inhibitory Receptor Genes. Immunity. 1997;7:753–763. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80394-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shilling HG, Guethlein LA, Cheng NW, et al. Allelic Polymorphism Synergizes with Variable Gene Content to Individualize Human KIR Genotype. The Journal of Immunology. 2002;168:2307–2315. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.5.2307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Young NT. Immunobiology of natural killer lymphocytes in transplantation. Transplantation. 2004;78:1–6. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000123764.10461.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsu KC, Keever-Taylor CA, Wilton A, et al. Improved outcome in HLA-identical sibling hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) predicted by KIR and HLA genotypes. Blood. 2005:2004–2012. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barao I, Murphy WJ. The immunobiology of natural killer cells and bone marrow allograft rejection. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2003;9:727–741. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruggeri L, Capanni M, Casucci M, et al. Role of natural killer cell alloreactivity in HLA-mismatched hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 1999;94:333–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsu KC, Gooley T, Malkki M, et al. KIR Ligands and Prediction of Relapse after Unrelated Donor Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation for Hematologic Malignancy. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2006;12:828–836. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leung W, Iyengar R, Turner V, et al. Determinants of Antileukemia Effects of Allogeneic NK Cells. The Journal of Immunology. 2004;172:644–650. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.1.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao Xy, Huang Xj, Liu Ky, Xu Lp, Liu Dh. Prognosis after unmanipulated HLA-haploidentical blood and marrow transplantation is correlated to the numbers of KIR ligands in recipients. European Journal of Haematology. 2007;78:338–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2007.00822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruggeri L, Mancusi A, Capanni M, et al. Donor natural killer cell allorecognition of missing self in haploidentical hematopoietic transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia: challenging its predictive value. Blood. 2007;110:433–440. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-038687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fandrich F, Lin X, Chai GX, et al. Preimplantation-stage stem cells induce long-term allogeneic graft acceptance without supplementary host conditioning. Nat Med. 2002;8:171–178. doi: 10.1038/nm0202-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gagne K, Brizard G, Gueglio B, et al. Relevance of KIR gene polymorphisms in bone marrow transplantation outcome. Human Immunology. 2002;63:271–280. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(02)00373-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruggeri L, Capanni M, Urbani E, et al. Effectiveness of Donor Natural Killer Cell Alloreactivity in Mismatched Hematopoietic Transplants. Science. 2002;295:2097–2100. doi: 10.1126/science.1068440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aversa F, Tabilio A, Velardi A, et al. Treatment of high-risk acute leukemia with T-cell-depleted stem cells from related donors with one fully mismatched HLA haplotype. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1186–1193. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199810223391702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruggeri L, Mancusi A, Burchielli E, et al. Natural killer cell recognition of missing self and haploidentical hematopoietic transplantation. Semin Cancer Biol. 2006;16:404–411. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luznik L, O’onnell PV, Symons HJ, et al. HLA-Haploidentical Bone Marrow Transplantation for Hematologic Malignancies Using Nonmyeloablative Conditioning and High-Dose, Posttransplantation Cyclophosphamide. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2008;14:641–650. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Velardi A. Role of KIRs and KIR ligands in hematopoietic transplantation. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20:581–587. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Przepiorka D, Weisdorf D, Martin P, et al. 1994 Consensus Conference on Acute GVHD Grading. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995;15:825–828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–480. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mantel N, Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. JNCI. 1959:719–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables (with discussion) J Roy Statist Soc (B) 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gooley TA, Leisenring W, Crowley J, Storer BE. Estimation of failure probabilities in the presence of competing risks: new representations of old estimators. Stat Med. 1999;18:695–706. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990330)18:6<695::aid-sim60>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gray RJ. A class of K-sample tests for comparing the cumulative incidence of a competing risk. Ann Statistics. 1988;16:1141–1154. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruggeri L, Capanni M, Mancusi A, et al. Alloreactive natural killer cells in mismatched hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood Cells, Molecules, and Diseases. 2004;33:216–221. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Handgretinger R, Chen X, Pfeiffer M, et al. Feasability and Outcome of Reduced Intensity Conditioning in Haploidentical Transplantation. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2007 doi: 10.1196/annals.1392.022. annals. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leung W, Iyengar R, Triplett B, et al. Comparison of Killer Ig-Like Receptor Genotyping and Phenotyping for Selection of Allogeneic Blood Stem Cell Donors. The Journal of Immunology. 2005;174:6540–6545. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.6540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aversa F, Terenzi A, Tabilio A, et al. Full Haplotype-Mismatched Hematopoietic Stem-Cell Transplantation: A Phase II Study in Patients With Acute Leukemia at High Risk of Relapse. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23:3447–3454. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bishara A, De Santis D, Witt CC, et al. The beneficial role of inhibitory KIR genes of HLA class I NK epitopes in haploidentically mismatched stem cell allografts may be masked by residual donor-alloreactive T cells causing GVHD. Tissue Antigens. 2004;63:204–211. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-2815.2004.00182.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun JY, Gaidulis L, Dagis A, et al. Killer Ig-like receptor (KIR) compatibility plays a role in the prevalence of acute GVHD in unrelated hematopoietic cell transplants for AML. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005;36:525–530. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shanmugaapriya S, Vikram M, Kavitha ML, et al. Effect of KIR Genotype on Outcome of Related HLA Identical Stem Cell Transplant in Patients with Beta Thalassaemia Major. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts. 2004;104:3337. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alter G, Martin MP, Teigen N, et al. Differential natural killer cell mediated inhibition of HIV-1 replication based on distinct KIR/HLA subtypes. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2007;204:3027–3036. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rauch A, Laird R, McKinnon E, Telenti A, et al. Influence of inhibitory killer immunoglobulin-like receptors and their HLA-C ligands on resolving hepatitis C virus infection. Tissue Antigens. 2007;69:237–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2006.773_4.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lorentzen AR, Karlsen TH, Olsson M, Smestad C, Mero IL, et al. Killer immunoglobulin-like receptor ligand HLA-Bw4 protects against multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2009;65:658–66. doi: 10.1002/ana.21695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shastry A, Sedimbi SK, Rajalingham R, et al. Different KIRs confer susceptibility and protection to adults with latent autoimmune diabetes in Latvian and Asian Indian populations. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2008;1150:133–38. doi: 10.1196/annals.1447.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jiao YL, Ma CY, Wang LC, et al. Polymorphisms of KIRs gene and HLA-C alleles in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: possible association with susceptibility to the disease. J Clin Immunol. 2008;28:343–349. doi: 10.1007/s10875-008-9183-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen C, Busson M, Rocha V, et al. Activating KIR genes are associated with CMV reactivation and survival after non-T-cell depleted HLA-identical sibling bone marrow transplantation for malignant disorders. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;38:437–444. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cooley S, Trachtenberg E, Bergemann TL, et al. Donors with group B KIR haplotypes improve relapse-free survival after unrelated hematopoietic cell transplantation for acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 2009;113:726–732. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-171926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cook M, Briggs D, Craddock C, et al. Donor KIR genotype has a major influence on the rate of cytomegalovirus reactivation following T-cell replete stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2006;107:1230–1232. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mancusi A, Ruggeri L, McQueen K, et al. Donor Activating Kir Genes and Survival after Haplo-Identical Hematopoietic Transplantation. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts. 2004;104:2219. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Verheyden S, Schots R, Duquet W, Demanet C. A defined donor activating natural killer cell receptor genotype protects against leukemic relapse after related HLA-identical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Leukemia. 2005;19:1446–1451. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McQueen KL, Dorighi KM, Guethlein LA, Wong R, Sanjanwala B, Parham P. Donor-Recipient Combinations of Group A and B KIR Haplotypes and HLA class I Ligand Affect the Outcome of HLA-Matched, Sibling Donor Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Human Immunology. 2007;68:309–323. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2007.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]