Summary

Sphingolipids are a ubiquitous class of lipids present in a variety of organisms including eukaryotes and bacteria. In the last two decades, research has focused on characterizing the individual species of this complex family of lipids, leading to a new field of research called sphingolipidomics. There are at least 500 (and perhaps thousands) different molecular species of sphingolipids in cells, and in Arabidopsis alone, it has been reported that there are at least 168 different sphingolipids. Plant sphingolipids can be divided into four classes: glycosyl inositol phosphoceramides (GIPCs), glycosylceramides, ceramides, and free long chain bases (LCBs). Numerous enzymes involved in plant sphingolipid metabolism have now been cloned and characterized, and, in general, there is broad conservation in the way sphingolipids are metabolized in animals, yeast and plants. Here, we review the diversity of sphingolipids reported in the literature, some of the recent advances in our understanding of sphingolipid metabolism in plants, and the physiological roles that sphingolipids and sphingolipid metabolites play in plant physiology.

Keywords: ceramides, free long chain bases, glycosyl inositol phosphoceramides, glycosylceramides, sphingolipids

I. Introduction

Sphingolipids are a ubiquitous class of lipids present in a variety of organisms including eukaryotes and bacteria (reviewed in Sperling & Heinz, 2003; Lynch & Dunn, 2004; Merrill et al., 2007, 2009; Spiegel & Milstein, 2003; Hannun & Obeid, 2008; Pruett et al., 2008). In the last two decades, research has focused on characterizing the individual species of this complex family of lipids, leading to a new field of research called sphingolipidomics (Merrill et al., 2005, 2007; Bielawski et al., 2006; Sullards et al., 2007; Pruett et al., 2008). Due to the complexity of sphingolipids, and their diversity between plants and also between organs within the same plant, powerful analytical tools are required to directly identify individual molecules. Some of the techniques used include capillary gas chromatography, infra-red spectrometry, high-performance liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry (Cahoon & Lynch, 1991; Sullards et al., 2000; Ng et al., 2001; Ternes et al., 2002; Bielawski et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2006; Markham et al., 2006; Markham & Jaworski, 2007; Shi et al., 2007). It is noteworthy that the success of LC/MS/MS approaches for characterizing sphingolipids is dependent on the development of efficient extraction protocols due to the diverse polarity associated with sphingolipids (Markham et al., 2006; Merrill et al., 2007, 2009).

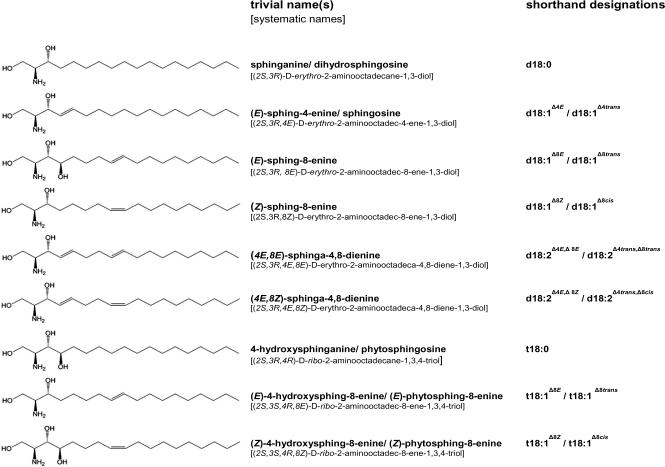

The composition of sphingolipid species within a given plant or organ/tissue is given the term `sphingolipidome' (Spassieva & Hille, 2003, Pruett et al., 2008, Merrill et al., 2009). Although there is great diversity in the composition of the sphingolipidome from different species, they are nevertheless made up of a basic building block comprising an amino alcohol long chain base (LCB), composed predominantly of 18 carbon atoms. The LCB is characterized by the presence of a hydroxyl group at C1 and C3 and an amine group at C2 (2-amino-1,3-dihydroxyalkane; Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Structures of representative C18 long chain bases (LCBs) found in plants. Trivial names and systematic names are consistent with IUPAC (http://www.chem.qmul.ac.uk/iupac/lipid/) regulations and shorthand designations are given for each LCB. All dihydroxy (d) and trihydroxy (t) LCBs are naturally occurring in plants with D-erythro and D-ribo configurations, respectively. These LCBs are detected as part of ceramides, complex sphingolipids or as free LCBs.

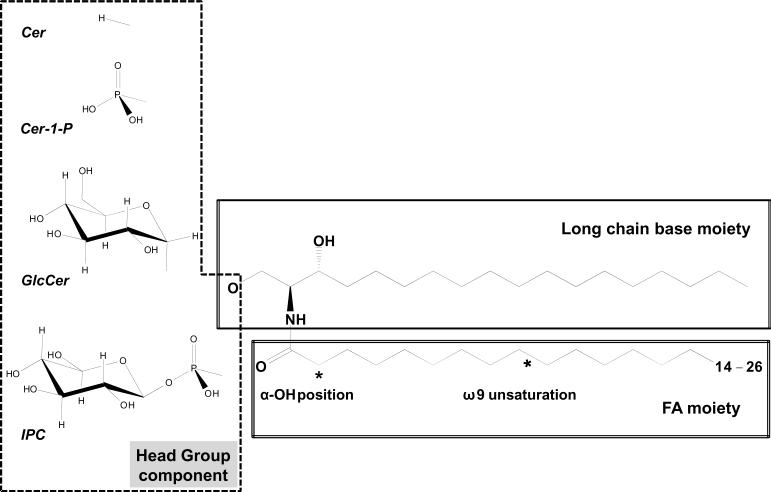

To form a ceramide, the amine group of the LCB is acylated with a fatty acid (FA) generally composed of 14–26 carbon atoms in plant cells (Sperling & Heinz, 2003; Lynch & Dunn, 2004). This N-acyl-LCB is the backbone of the sphingolipids detected in cells, and therefore the basic building block for the synthesis of more complex sphingolipids. The basic ceramide structure can be further modified through changes in chain length, methylation, hydroxylation and/or degree of desaturation of both the LCB and FA moieties (Fig. 2). Further modifications involves the conjugation of the primary hydroxyl (OH) group of the LCB moiety (Fig. 2), resulting in a polar headgroup which can be a phosphoryl group (ceramide-phosphates), mono- or pluri-hexose (glycosylceramides), and an inositol-phosphate group (IPC) (Fig. 2) (Sperling & Heinz, 2003; Spassieva & Hille, 2003; Lynch & Dunn, 2004).

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of complex sphingolipids from plants. The general structure of complex sphingolipids is based on a hydrophobic ceramide core and a hydrophilic head group. The ceramide core is made up of two moieties, a long chain base (LCB) and a fatty acid (FA) linked via an amide bond. The LCB moiety can vary and some of the common LCBs are shown in Fig. 1. The FA can vary in length, unsaturation and hydroxylation. The ceramide core shown here is dihydroceramide, which is a biosynthetic precursor of ceramide cores in the de novo pathway. GlcCER, glycosylceramide; IPC, inositolphospho ceramide. IPC can be further glycosylated with different sugar residues.

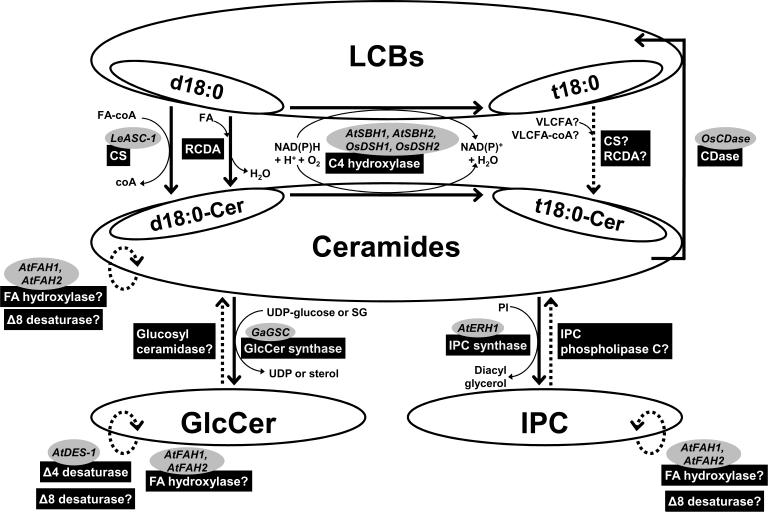

There are at least 500 (and perhaps thousands) different molecular species of sphingolipids in cells (Vesper et al., 1999; Hannun & Luberto, 2000; Futerman & Hannun, 2004). In Arabidopsis alone, it has been reported that there are at least 168 different sphingolipids (Markham & Jaworski, 2007) and 30 different ceramide cores have been identified in rye leaves (Cahoon & Lynch, 1991). It is therefore no surprise that the potential exists, in any organism, for the generation of highly diverse and complex sphingolipids through diversity in the composition of the FA, LCB, and headgroup modifications. Plant sphingolipids can be divided into: glycosyl inositol phosphoceramides (GIPCs), glycosylceramides, ceramides, and free LCBs. The structures of GIPCs, glycosylceramides, ceramides, and LCBs are illustrated in Figs 1 and 2, and Tables 1–6. Numerous enzymes involved in plant sphingolipid metabolism have now been cloned and characterized. In general, there is broad conservation in the way sphingolipids are metabolized in animals, yeast and plants. Sphingolipids can be formed by two pathways: the de novo pathway, starting with the condensation of a serine with an acyl-CoA; and the salvage pathway, where ceramides and LCBs are released from more complex sphingolipids, followed by channelling of the metabolites formed into the synthetic pathway (Merrill, 2002; Hannun & Obeid, 2008; Kitatani et al., 2008) (Figs 3, 4). In the following sections, we shall review the functions of the major plant sphingolipid classes. For in-depth reviews of plant sphingolipid metabolism, readers are referred to excellent reviews by Spassieva & Hille (2003), Sperling & Heinz (2003), and Lynch & Dunn (2004).

Table 1.

Main characteristics of plant glycosyl inositol phosphoceramides (GIPCs)

| Family | Species | Tissue | Core headgroup | Addtional sugars | LCB profile (mol%) | FA composition (mol%) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PGL | |||||||

| Linaceae |

Linum

usitatissimum |

seed | Ara, Gal, Man, Fuc |

70 % t18:1Δ8 17 % t18:0 |

44% αOH C24 17% αOH C25 11% αOH C26 |

a – d | |

|

| |||||||

| CPPS | |||||||

| Poaceae | PGL | ||||||

| Zea Mays | seed | Ara, Gal | t18:0 | 65% (αOH C24; αOH C26) 24% (C16; C18) 11% C24 |

a – c | ||

| CPPS | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Triticum

aestivum |

seed | (inositol-P, GlcN, Ara,Gal, Man) | t18:0 | a | |||

|

| |||||||

| (inositol-P, GlcN, Ara, Gal, Man) | |||||||

| Fabaceae | Glycine max | seed | t18:0 t18:1Δ8 |

95% (C16; C18) 5% αOH C24 |

a, c | ||

| CPPS | Ara, Gal, Fuc, Man |

||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Arachis

hypogaea |

seed | (inositol-P, GlcN, Ara,Gal, Man) | a | ||||

|

| |||||||

|

Phaseolus

vulgaris |

leaf | hexosamine- hexuronic acid- inositol-P |

Ara, Gal, Man |

53% t18:1Δ8 32% t18:0 |

48% αOH C24 20% αOH C22 10% αOH C26 |

d | |

|

| |||||||

| Malvaceae |

Gossypium spp. |

seed | (inositol-P, GlcN, Ara,Gal, Man) | t18:0 | a | ||

|

| |||||||

| Asteraceae |

Helianthus

annus |

seed | (inositol-P, GlcN, Ara,Gal, Man) | t18:0 | a | ||

|

| |||||||

|

Carthamus

tinctorius |

seed | CPPS | Ara, Gal, Fuc, Man |

c | |||

|

| |||||||

| Solanaceae | PSL-I | [Ara2Gal2]; Ara3Gal2]; Ara4Gal2] |

52–58% αOH C24 10–18% αOH C25 11–13% αOH C26 10–12% αOH C22 |

e – h | |||

|

Nicotiana

tabacum |

leaf | PSL-II | [Ara3Gal]; [Ara2or3Gal2]; [Ara2Gal2Man] |

50–55% αOH C24 11–17% αOH C22 11–13% αOH C26 10–13% αOH C25 |

e,f | ||

| GPC | Ara, Gal | h | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Brassicaceae |

Arabidopsis

thaliana |

leaf | 73% t18:1Δ8 15% t18:0 |

αOH C24:1 > αOH C24 > αOH C20 > αOH C26 =αOH C16 |

i, j | ||

The name of the core headgroup followed the defunct name given to the GIPCs and are detailed in Table 2. The early characterization on seeds did not establish a model for the structure of the headgroup but only the rough composition, which is indicated between brackets. The number of additional sugars has been determined up to 13 and more in tobacco leaves (Kaul & Lester, 1978). Ara, arabinose; Fuc, fucose; Gal, galactose; Man, mannose. References:

Table 6.

Main characteristics of the long chain base (LCB) moiety of plant ceramides

| Family | Species | Tissue | d18 | d18:1Δ4E | d18:1Δ8E | d18:1Δ8Z | d18:24EΔ8E | t18:04EΔ8Z | t18:0 | t18:1Δ8E | t18:1Δ8Z | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poaceae | seed bran | 2.2 | 0.5 | 7.4 | 1.6 | 2.6 | 68.8 | 16.9 | a | |||

|

|

||||||||||||

| Oryza sativa | endosperm | 10.1 | 5.8 | <0.1 | 4.7 | 24.4 | 45.8 | 9.2 | a | |||

|

|

||||||||||||

| leafy stem | 1.8 | <0.1 | 4.3 | 0.2 | 1.5 | 83 | 9.2 | b | ||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Brassicaceae | Arabidopsis thaliana | leaf | 1.1 | 15.9–47.7 | 49.3–76.3 | 2.9–6.7 | f, g | |||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Fabaceae | Pisum sativum | seed | 3.1 | 1.6 | 35.1 | 60.2 | c | |||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Phaseolus vulgaris | leaf | 24 | 54ξ | d | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Solanaceae | Solanum tuberosum | tuber | 7.4ξ | 57.5ξ | 35.1ξ | e | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Convolvulaceae | Ipomoea batatas | tuber | 10.3ξ | 37.9ξ | 51.7ξ | e | ||||||

The data reported here are expressed in mol% of total ceramide, except § (wt%).

Value independent of the isomer configuration.

References: Fujino et al. (1985)

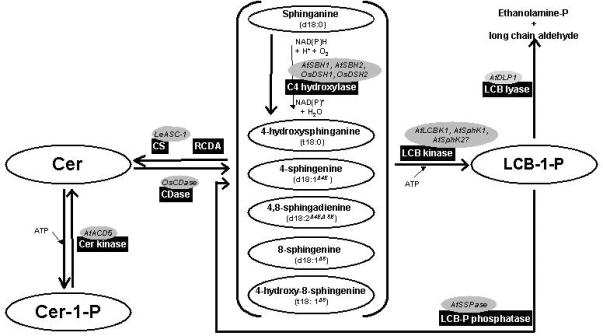

Fig. 3.

Schematic representation of the sphingolipid biosynthesis pathway in plants. All metabolic steps indicated by a plain arrow have been demonstrated in vitro. Activities are indicated in black boxes. Genes which have been cloned are indicated in dark grey ovals. The substrates for desaturation and fatty acid (FA) hydroxylase remain to be determined. Although ceramidase (CDase) activity has been detected, the substrate specificity remains to be characterized. Note that reverse CDase activity (RCDA) and CDase are activities from the same enzyme. LCB, long chain base; IPC, inositolphospho ceramide.

Fig. 4.

Schematic representation of the sphingolipid metabolic pathway for phosphorylation of ceramides and long chain bases (LCBs) in plants. Activities are indicated in black boxes. Genes which have been cloned are indicated in dark grey ovals. The substrate specificity has been characterized for LCB lyase and LCB kinase. Biochemical properties of LCB-P phosphatase remain to be determined.

II. Ceramide metabolism

Ceramide can be formed via 2 pathways, FA-coA-dependent and free FA-dependent pathways. The FA-coA-dependent pathway is the major route through which ceramide is synthesized in plants (reviewed by Sperling & Heinz, 2003; Lynch & Dunn, 2004). The formation of the ceramide core (comprising the LCB and the FA moieties) occurs via the condensation of a FA with the amino group of sphinganine (dihydrosphingosine, d18:0). This reaction is catalyzed by dihydroceramide synthase (DHCS; E.C. 2.3.1.24) and the reaction is FA-CoA dependent. Plant DHCSs have been shown to utilize a range of FA-coA (C16 to C24) but not α-OH FA-coA as substrates (reviewed by Sperling & Heinz, 2003; Lynch & Dunn, 2004). However, the major forms of ceramide, glycosylceramide and GIPC contain α-OH FAs, suggesting that FA hydroxylation is likely to be downstream of ceramide formation. Ceramides can also be formed from the N-acylation of the amino group of a LCB with a free FA acting as the acyl donor (Merill, 2002; Spassieva & Hille, 2003; Sperling & Heinz, 2003, Lynch & Dunn, 2004). This reaction is catalyzed by the reverse activity of ceramidases.

Once the dihydroceramide (d18:0-ceramide) is formed, it can be further modified by C4-hydroxylation of the LCB moiety to yield phytoceramide (t18:0-ceramide), although this reaction can also occur through the use of sphinganine (d18:0) as the substrate in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (Wright et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2008). The ceramides can then be channelled for further modifications (Fig. 3), resulting in the formation of more complex sphingolipids like GIPCs and glycosylceramides (Fig. 3). They can also be used as substrates for the synthesis of ceramide phosphates (Liang et al., 2003; Fig. 4). Ceramides can also be broken down by the activity of ceramidases (CDases) leading to the formation of free LCBs.

Plant glycosylceramide synthases has been characterized using different microsomal preparations (Nakayama et al., 1995; Lynch et al., 1997; Cantatore et al., 2000) and an orthologue from cotton has been cloned (Leipelt et al., 2001). It is generally accepted that glycosylceramides are synthesized in the ER and/or plasma membrane whereas GIPCs are synthesized in the Golgi (Bromley et al., 2003; Hillig et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2008). The initial committed step of GIPC synthesis is the formation of IPC that requires the transfer of inositol phosphate from the phospholipid phosphatidylinositol (PI) to ceramide. This reaction results in the release of diacylglycerol by-products and is catalyzed by an IPC synthase.

IPC synthase activity has been characterized in wax bean microsomes (Bromley et al., 2003). The IPC synthase activity was detected in a variety of plants and relatively high levels of activities were detected in the Fabaceae (Bromley et al., 2003). IPC synthase is able to catalyse IPC synthesis using non-hydroxy and hydroxyceramide as substrate. However, the wax bean IPC synthase exhibits greater activity towards ceramides with α-OH FA (Bromley et al., 2003). IPC synthase has been shown to be an important regulator of plant ceramide pool. In the Arabidopsis IPC synthase mutant erh1, the level of ceramides is dramatically increased and the plants exhibit enhanced hypersensitive response (HR)-like cell death when challenged with powdery mildew (Wang et al., 2008).

To date, α-hydroxylation of the FA moiety of plant sphingolipids have not been characterized in vitro, although ceramide synthase has been shown to be inhibited by α-OH FA, and as such, it is generally believed that α-hydroxylation occurs after ceramide core formation (Sperling & Heinz, 2003; Warnecke & Heinz, 2003; Lynch & Dunn, 2004). The α-hydroxylase activity in the protozoan Tetrahymena pyriformis has then been demonstrated to prefer FA from ceramide or complex sphingolipids (Kaya et al., 1984). The yeast gene, FAH1/SCS7, was shown by deletion/disruption to be involved in the α-hydroxylation of C26 very long chain fatty acid (VLCFA) (reviewed by Sperling & Heinz, 2003, Lynch & Dunn, 2004). Two putative α-hydroxylase (AtFAH) homologues have been identified in Arabidopsis and both homologues were able to restore α-hydroxylase activity in the fah1Δ yeast mutant strain (Nagano et al., 2009). Interestingly, the Arabidopsis α-hydroxylases lack the cytochrome b5 (cyt b5) domain, unlike its yeast counterpart (reviewed by Sperling & Heinz, 2003, Lynch & Dunn, 2004). Nagano et al. (2009) showed that the AtFAHs can interact with the Arabidopsis cytochrome b5 (AtCb5) and that the AtFAH-AtCb5 complex is subjected to regulation by the Arabidopsis Bax inhibitor-1 (AtBl-1) protein, leading the authors to suggest that AtBl-1, through its interaction with the AtCb5-AtFAH complex can regulate cell death via changes in the levels of α-OH ceramides with VLCFAs (Nagano et al., 2009).

The observations that ceramide may be involved in regulating plant programmed cell death has led to efforts to understand how ceramides may be metabolized through the action of ceramidases (CDases). Much of our understanding of the function of CDases (E.C. 3.5.1.23) was derived from work involving animal cells and yeast (Mao et al., 2000a,b; Mao & Obeid, 2008). In animals, CDases are regarded as major regulators of ceramide-induced apoptosis (Choi et al., 2003; Hannun & Obeid, 2008; Mao & Obeid, 2008) as they are key enzymes intimately involved in regulating the levels of ceramides and 4-sphingenine (sphingosine, d18:1Δ4E), and hence sphingenine-1-phosphate (S1P, d18:1Δ4E-1-P). These 3 sphingolipid metabolites have been shown to be key bioactive mediators of cellular processes governing growth, differentiation, apoptosis and survival (Spiegel & Milstien, 2003; Hannun & Obeid, 2008; Mao & Obeid, 2008). As such CDases are key enzymes regulating the availability of sphingosine and S1P, thereby affecting the balance of ceramide/sphingenine/S1P in animal cells (Spiegel & Milstien, 2003; Hannun & Obeid, 2008; Mao & Obeid, 2008).

Ceramidases degrade ceramides by hydrolyzing the N-acyl linkage between the LCB and FA moieties. Diverse CDases have been characterized, and they exhibit differences in their subcellular localization, substrate specificities and pH optima. In general, CDases are classified according to their pH optima as acidic CDases, neutral CDases and alkaline Cdases (Table 7). Readers are referred to Mao & Obeid (2008) for an excellent review of human CDases. The neutral CDase family is by far the best characterized of all 3 classes of CDases. They have been shown to be involved in key developmental processes in mammals. In human mesengial cells and rat hepatocytes, neutral CDase activity was shown to be modulated in response to various stimuli like cytokines and growth factors leading to control of cellular proliferation and differentiation (Coroneos et al., 1995; Nikolova-Karakashian et al., 1997). Knockdown of neutral CDases in zebrafish during embryogenesis have been shown to result in abnormal development, likely from dysfunction in the circulatory system (Yoshimura et al., 2004). Neutral CDases are considered as rate-limiting enzymes for the production of 4-sphingenine (d18:1Δ4E). This free LCB is produced in animal cells only through the salvage pathway and not by de novo synthesis. Metabolism of ceramide by neutral CDases is therefore an important contributing factor for regulating S1P (d18:1Δ4E-1-P) signalling through the generation of 4-sphingenine (d18:1Δ4E) (Mao & Obeid, 2008). As such, it has been proposed that neutral CDases are key modulators of cellular processes and signalling as they regulate the availability of the ceramide and LCB pools through their enzymatic activity (El Bawab et al., 2002; Tani et al., 2005; Mao & Obeid, 2008).

Table 7.

Classification and characteristics of known neutral ceramidases

| Source | Isoform | Molecular mass (kDa) |

pH optimum |

Substrate utilization |

RCDA / pHRCDA optimum |

Glycosylation | Subcellular localization | Predicted TM / topogenesis |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | nd | ~9 | d18:1Δ4-Cer | ? | high (N-glycosylation) | cytosol | 0 / | b | |

|

|

|

||||||||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 70 | ~7–8.5 | d18:1Δ4-Cer = d18:0-Cer |

+ / ~7 | extracellular, periplasm | a – e | |||

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Drosophila melanogaster | 79 | ~6.5–7.5 | d18:1Δ4-Cer | + | extracellular, periplasm | f, g | |||

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Dictyostelium discoideum | 93 | ~3 | d18:1Δ4-Cer | + / ~5 | extracellular, periplasm | 1 / secretory | h | ||

|

| |||||||||

| Danio rerio | ~7.5 | d18:1Δ4-Cer | ? | high (N-glycosylation) | ER, Golgi, PM, extracellular | i | |||

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Mus musculus | 94 | ~7–8.5 | d18:1Δ4-Cer > d18:0-Cer |

+ | PM, extracellular + endosome-like organelles (liver isoform) | j – m | |||

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Rattus norvigecus | kidney | 112 | ~5.5–7.5 | d18:1Δ4-Cer | ? | PM |

n | ||

| liver | nd | ? | ? | ? | endosome-like organelles |

n | |||

| intestine | 116 | ~5.5–6.5 | d18:1Δ4-Cer | ? | ? |

o | |||

| brain | 90–95 | ~7–10 | αOH-d18:1Δ4-Cer >> d18:1Δ4-Cer |

+ / ~6–7 | ? | p – r | |||

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Homo sapiens | long isoform | 142§ | ~7–8.5 | d18:1Δ4-Cer | + | ER, Golgi, PM, extracellular |

s, t | ||

| short isoform | 140§ | ~7–9.5 | d18:1Δ4-Cer | ? | ER, Golgi, extracellular; mitochondrial |

k, s | |||

| intestine | 116 | ~6–8 | d18:1Δ4-Cer | + / ~5–7.5 | ? | u | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Oryza sativa | nd | ~5–7 | d18:1Δ4-Cer | ER, Golgi | v | ||||

Molecular mass (kDa) when expressed in HEK293 cells

Not for liver neutral CDase, localized in endosome-like organelles.

SphCER, sphingosine-ceramide; dihydroCER, dihydrosphingosine-ceramide; TM, transmembrane domain; ER, endoplasmic reticulum. All enzymes have been cloned except for the rat and human intestine counterparts.

References: Okino et al. (1998

In contrast to the situation in animals and yeast, much less is known about CDases in plants. Lynch (2000) used a biochemical approach to show that a CDase activity can be isolated from plant membrane fractions. Optimal activity was observed from pH 5.2 to 5.6 and Ca2+ is required as a cofactor. Sequence mining (BLAST) of the rice genome using the human neutral CDase protein sequence showed the presence of one neutral CDase (OsCDase) with the gene ID LOC_Os01g43520 (Pata et al., 2008). The biochemical characterization of OsCDase established a broad pH optimum in the acidic to neutral range (Pata et al., 2008; Table 7). This feature could underline a relatively large spectrum of roles for OsCDase as the genome of rice showed the presence of only one putative alkaline CDase bearing sequence similarities to the yeast phytoCDases. Sequence analysis indicated that plants do not possess proteins bearing any sequence similarities to acid CDases.

Analysis of substrate utilization by OsCDase revealed a substrate preference for ceramide (d18:4Δ4-ceramide) and not phytoceramide (t18:0-ceramide) (Pata et al., 2008). This is interesting as d18:4Δ4-ceramide is not the major ceramide species in fungi and plants (Ohnishi et al., 1985; Sperling & Heinz, 2003; Dunn et al., 2004; Lynch & Dunn, 2004). The substrate specificity of OsCDase for d18:4Δ4-ceramide is consistent with it being a member of the neutral CDase family as only the alkaline CDases have been shown to hydrolyze t18:0-ceramide (Mao & Obeid, 2008). Sphingolipidomic analyses of ceramide species following expression of OsCDase in the yeast double knockout mutant, Δypc1Δydc1, which lacks the yeast CDases also showed that both d18:0-ceramide (dihydroceramide) and t18:0-ceramide are unlikely to be substrates for OsCDase (Pata et al., 2008). Reverse ceramidase activity (RCDA) has been reported in several members of the neutral CDase family (Table 7; Okino et al., 1998; Kita et al., 2000; El Bawab et al., 2000; Wu et al., 2007), and analyses of yeast sphingolipids following induction of OsCDase expression in the double knockout mutant, Δypc1Δydc1, showed elevated levels of t18:0-ceramide with FA chain lengths of C26 and C28 (Pata et al., 2008). This observation points to the possibility that OsCDase may exhibit RCDA, leading to elevated levels of these 2 t18:0-ceramide species (Fig. 4). The main route for ceramide formation is via ceramide synthase. For example, in plant preparations, RCDA is <5% of ceramide synthase activity (Sperling & Heinz, 2003; Lynch & Dunn, 2004). For this reason, RCDA was proposed to occur to prevent cytotoxicity (Sperling & Heinz, 2003) or when ceramide synthase is inhibited (Mao et al., 2000a,b).

In yeast, the sur2 gene encodes the enzyme responsible for the C4-hydroxylation of C18 and C20 LCBs. The C4 hydroxylase uses both d18:0-ceramide and tfree sphinganine (d18:0) as substrates (Dickson & Lester, 2002; Obeid et al., 2002; Dickson et al., 2006). Recently Chen et al. (2008) showed that a double T-DNA knockout of the sur2 homologues (SBH1, SBH2) resulted in Arabidopsis plants lacking trihydroxy LCBs (4-hydroxysphinganine, t18:0 and 4-hydroxy-8-sphingenine, t18:1Δ8). They also observed significant increases in total sphingolipid content, notably those of the complex sphingolipids and free LCBs (Chen et al., 2008). In this mutant plant, complex sphingolipids and ceramides containing the C16 FA moiety appear to be elevated compared to complex sphingolipids and ceramides containing VLCFAs (≥ C20) (Chen et al., 2008). The authors proposed the existence of an alternative ceramide synthesis pathway in plants using 4-hydroxysphinganine (t18:0) as the LCB moiety and VLCFA as the acyl donor (Chen et al., 2008). With this in mind, it is possible that the RCDA encoded by the neutral CDase homologues in plants, for example, OsCDase (Pata et al., 2008) may be responsible for the `alternative' ceramide synthesis pathway in plants.

III. Physiological functions of plant sphingolipid classes

1. Physiological functions of glycosyl inositol phosphoceramiades (GIPCs)

In the late 50s, Carter and colleagues focused their interest on inositol sphingolipids, which at that time, were thought to be specific to the plant kingdom, and were named phytoglycolipids (Carter et al., 1958). The name phytoglycolipid is now defunct and these compounds are now referred to as GIPCs (Spassieva & Hille, 2003; Worrall et al., 2003; Lynch & Dunn, 2004). GIPCs are predominant forms of complex sphingolipids common to plants and fungi, but not present in animal cells (Obeid et al., 2002; Warnecke & Heinz, 2003; Worrall et al., 2003; Lynch & Dunn, 2004). Although GIPCs belong to one of the earliest classes of plant sphingolipids to be identified (Carter et al., 1958; Carter & Koob 1969; Kaul & Lester, 1975, 1978; Hsieh et al., 1978, 1981), very few GIPCs have been fully characterized to date (Tables 1, 2) due to their high polarity and relatively poor recovery from traditional extraction techniques (Spassieva & Hille, 2003; Sperling et al., 2005; Markham et al., 2006).

Table 2.

Structure of the core headgroups in glycosyl inositol phosphoceramides (GIPCs)

| Headgroup name | Headgroup structure | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| PGL | glucosamine-hexuronic acid-inositol-P | a,b |

| | ? | ||

| Man | ||

|

| ||

| CPPS | hexuronic acid-inositol-P | c |

|

| ||

| PSL-I | N-acetylglucosamine (α1→4)-glucuronic acid (α1→2)-myo-inositol-1-O-P | e – h |

|

| ||

| PSL-II | glucosamine-glucuronic acid-inositol-P | e,f |

|

| ||

| GPC | N-acetylglucosamine (α1→4)-glucuronic acid (α1→2)-myo-inositol-1-O-P | |

| | | h | |

| (?→1α) Man | ||

Two different classes of GIPCs were characterized by Carter and co-workers: PGL (phytoglycolipid) and CPPS (ceramide phosphate polysaccharide). The latter is devoid of hexosamine. The link position of the Man group was not determined with precision but later appeared to be on the inositol group of a GPC core (glycophosphoceramide) co-purified with a Gal(α→4)-PSL-I core (phosphosphingolipid) (Hsieh et al., 1981). References:

The cellular localization of a molecule is likely to reveal insights into its function. Few data are available for the cellular localization of GIPCs although it is widely assumed that they are localized to the plasma membrane (Lynch & Dunn, 2004; Worrall et al., 2003; Sperling et al., 2005). The relatively similar composition and proportion of LCB between the plasma membrane and the GIPC fraction isolated from Arabidopsis leaves appear to lend credence to this assumption although direct evidence for the cellular localization and transbilayer distribution of GIPCs in plant membranes are still lacking (Sperling & Heinz, 2003, Lynch & Dunn, 2004, Sperling et al., 2005; Markham et al., 2006; Markham & Jaworski, 2007).

The Arabidopsis IPC synthase, ERH1 has been localized in the Golgi (Wang et al., 2008), and sphingolipids have been shown to be involved in Golgi and ER integrity, (Chen et al., 2008). Added to the involvement of a GIPC in the early stages of symbiosis (Perotto et al., 1995) and to the confirmed role of plant GIPCs as GPI anchors of proteins preferentially partitioned into `lipid rafts' (Bhat & Panstruga, 2005; Borner et al., 2005), GIPCs may therefore be important determinants in cell signalling, cell-cell communications and sorting of proteins akin to the role of complex sphingolipids in animal development (Worrall et al., 2003; Spassieva & Hille; 2003).

2. Physiological functions of glycosylceramides

Another class of plant sphingolipids are the glycosylceramides and they are structurally simpler compared to GIPCs (Fig. 2). They are often referred as cerebroside or glucocerebroside in the literature as they are structurally similar to galactosylceramide from brain (Spassieva & Hille, 2003; Warnecke & Heinz, 2003). The glycosylceramides are also the most extensively characterized of the sphingolipid classes in terms of their structure because they are abundant in the plant plasma and vacuolar membranes, and they are relatively easy to extract and purify (Spassieva & Hille, 2003; Warnecke & Heinz, 2003; Lynch & Dunn, 2004; Takakuwa et al., 2005). While GIPCs are unique to organisms possessing a cell wall (plant and fungi), glycosylceramides on the other hand are common to most eukaryotic organisms and few bacteria (Warnecke & Heinz, 2003).

In glycosylceramides, the headgroup hexoses are either β-glucose or β-mannose. In addition to the hexose moiety attached at C1, the FA moiety of plant glycosylceramides is usually α-hydroxylated (Lynch et al., 1992; Whitaker, 1996; Norberg et al., 1996; Sullards et al., 2000; Bohn et al., 2001). In many species, α-OH C16 is the major FA species. However in the Poaceae family, the FA moieties of glycosylceramides are very long chain fatty acids (VLCFAs; FA with ≥C20). Another characteristic of this family is the high levels of the ω9desaturated FA moiety, especially α-OH C24:1 (Imai et al., 2000). Tables 3 and 4 detail the diversity and relative abundances of the VLCFAs and LCB moieties of glycosylceramides in plants (Tables 3, 4).

Table 3.

Main characteristics of the fatty acid (FA) moiety of plant glycosylceramides

| Family | Species | Tissue | Non-OH | short αOH FA (C<20) | saturated | unsaturated αOH VLCFA | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FA | αOH VLCFA | ||||||

| Poaceae | Oryza sativa | seed bran* | 11 | 5.6–8 | 83.3–91 | a, b | |

| endosperm* | 9 | 5.4 | 86 | a | |||

| leafy stem | <1 | 2.1 | 97.9 | c | |||

| leaf | 1.5 | 94 | d | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Zea mays | leaf | 8.4 | 86.5 | d | |||

| root | 19.1 | 12.6 | 68.3 | e | |||

|

| |||||||

| Avena sativa | leaf | 6.8–7 | 12.1–77.5 | 10.8–80.5 | d, f | ||

| leaf (CA) | 5.8 | 6.9 | 87 | f | |||

| root | >90 | g | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Triticum aestivum | flour | 2 | 71.7 | 26 | h | ||

| hypocotyl | 53 | 44 | b | ||||

| leaf | 8.8 | 58.8 | 27.4 | d | |||

|

|

|||||||

| Secale cereale winter rye cv. Puma | leaf | 3–18.8 | 25–37.3 | 42.5–61 | d, f, i | ||

| leaf (CA) | 11.3 | 24.3 | 64.3 | f | |||

|

| |||||||

| Brassicaceae | Arabidopsis thaliana | leaf | 82 | 4.6 | 5.9 | j | |

| leaf (CA) | 85.2 | 5.8 | 6.5 | j | |||

|

| |||||||

| Brassica oleracea (cabbage) | leaf | 32 | 68 | d | |||

|

| |||||||

| Brassica oleracea (broccoli) | leaf | 29 | 57 | 14 | d | ||

|

| |||||||

| Fabaceae | Glycine max | seed | >95 | k | |||

|

| |||||||

| leaf | 55 | 44 | d | ||||

| Pisum sativum | seed* | 2 | 59.6 | 33.3 | l | ||

|

| |||||||

| Phaseolus vulgaris | leaf | 7 | 1 | 77 | m | ||

|

| |||||||

| Solanaceae | Solanum tuberosum | leaf | 82 | 17 | d | ||

| tuber | 6.4–20.9 | 78–88.5 | 1.7–4.4 | 0.2–1.5 | n | ||

|

| |||||||

| Capsicum annuum | leaf | 86 | 13 | d | |||

| red-ripe fruit | 60 | 40 | o | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Lycopersicon esculentum | leaf | 78 | 23 | d | |||

| red-ripe fruit | 70 | 30 | o | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Vitaceae | Vitis vinifera | leaf | 55.3 | 39.7 | p | ||

|

| |||||||

| V. vinifera cv. Zweigeltrebe‡ | leaf | 48 | 49.5 | p | |||

|

| |||||||

| Convolvulaceae | Ipomoea batatas | tuber | 10.6 | 80 | 10.8 | 1 | n |

| leaf | 8 | 88 | d | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Cucurbitaceae | Cucurbita maxima | leaf | 74 | 26 | d | ||

|

| |||||||

| Cucumis sativus | leaf | 62 | 38 | d | |||

The data reported here are expressed in mol% of total glycosylceramide.

Only composition of monoglucosylceramide has been considered.

This species is considered freezing sensitive compare to the wild type species. CA, cold acclimated (4 wk).

References: Fujino et al. (1985)

Table 4.

Main characteristics of the long chain base (LCB) moiety of plant glycosylceramides

| Family | Species | Tissue | d18 | d18:1Δ4E | d18:1Δ8E | d18:1Δ8Z | d18:2Δ4EΔ8E | d18:2Δ4EΔ8Z | t18:0 | t18:1Δ8E | t18:1Δ8Z | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poaceae | Oryza sativa | seed bran* | 0.3–1 | 1–2.5 | 1–1.8ξ | 13–16.5 | 50–53.3 | 3.3–6 | 3–6.1 | 16.2–25 | a, b | |

| endosperm* | 1 | 5.9 | 2.2ξ | 34.6 | 40.4 | 1.2 | 2.8 | 11.9 | a | |||

| leafy stem | <0.1 | 1.4 | 0.4ξ | 16.3 | 22.6 | 2.7 | 56.6ξ | c | ||||

| leaf | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 11.5 | 34.3 | 0.8 | 3.1 | 49.6 | d | |||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Zea mays | leaf | <0.1 | 0.2 | 1 | 17.3 | 55.7 | 0.4 | 1.6 | 23.8 | d | ||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Avena sativa | leaf | <0.1 | 1.6 | 0.7 | 13.5 | 16.2 | 1.6 | 14.8 | 51.6 | d | ||

| leaf | 35.9ξ | 63.1ξ | e | |||||||||

| leaf (CA) | 31.6ξ | 67.9ξ | e | |||||||||

| root | 100ξ | f | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Triticum aestivum | hypocotyl | 14 | 1 | 25 | 47 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 2 | g | |

| leaf | 0.2 | 1.3 | 3.2 | 5.2 | 9.4 | 0.9 | 6.9 | 72.9 | d | |||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Secale cereale winter rye cv. Puma | leaf | 3 | 14 | 6 | 70 | h | ||||||

| leaf | 1.1ξ | 21.8ξ | 69.2ξ | e | ||||||||

| leaf (CA) | 1.1ξ | 17.1ξ | 66.6ξ | e | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Brassicaceae | Arabidopsis thaliana | leaf | 0.4–1.6 | 22.7–27.9 | 2–4.8 | 1.1 | 21.5–32.9 | 40.9–44.2 | i, j | |||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Brassica oleracea | inflorescence | 18.6 | 3 | 22.4 | 56 | j | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Fabaceae | Glycine max | seed | >95ξ | k | ||||||||

| leaf | 0.3 | 3 | 1.3 | 33.5 | 14.2 | 0.7 | 22.2 | 24.8 | d | |||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Pisum sativum | seed* | 1.8 | 0.4 | 51.1ξ | 9.6 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 35.7ξ | l | |||

| leaf | 0.7 | 17.7–29.3 | 11.5–35.6 | 4.8 | 2.3 | 0.8–1.1 | 5.6–20.8 | 28.4–41.4 | d, j | |||

| root | 30.6 | 14.3 | 9.5 | 2.2 | 21.8 | 21.6 | j | |||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Phaseolus vulgaris | leaf | 4 | 7 | 52ξ | m | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Solanaceae | Solanum tuberosum | tuber | 4.9ξ | 91.4ξ | 3.7ξ | n | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Capsicum annuum | leaf | 1.1 | 21.3 | 29 | 24.2 | 13.4 | 0.2 | 4.7 | 6.1 | d | ||

| red-ripe fruit | 17ξ | 45ξ | 34ξ | o | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Lycopersicon esculentum | leaf | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 57.8 | 20 | 0.3 | 16.9 | 4.2 | d | ||

| red-ripe fruit | 76ξ | 27ξ | o | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Nicotiana tabacum | leaf | 22.1 | 72.3 | 2.2 | 3.4 | j | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Vitaceae | Vitis vinifera | leaf | <0.1 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 18.5 | 55.7 | 0.2 | 5.7 | 18.5 | p | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| V. vinifera cv. Zweigeltreb‡ | leaf | 0.1 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 26.7 | 50.4 | 0.3 | 8.3 | 11.9 | p | ||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Convolvulaceae | Ipomoea batatas | leaf | 0.2 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 14.7 | 17.7 | 0.6 | 12.4 | 53 | d | |

| tuber | 4.4ξ | 86.1ξ | 9.5ξ | n | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Cucurbitaceae | Cucurbita maxima | leaf | 54 | 17 | 19 | 10 | d | |||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Cucumis sativus | leaf | 67 | 2 | 24 | 7 | d | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Amaranthaceae | Spinacia oleracea | leaf | 0.1 | 2.9–5.1 | 0.9 | 44.6–65 | 1.4–5.5 | 0.1–19.7 | 7.4–10.4 | 16.9–21 | d, j | |

The data reported here are expressed in % of total glycosylceramide.

Only proportion for monoglucosylceramide has been considered.

This species is considered freezing sensitive compare to the wild type species.

Value independent of the isomer configuration. CA, cold acclimated (4 wk).

References: Fujino et al. (1985)

Numerous functions have been ascribed to glycosylceramides in plants and they include membrane stability, membrane permeability and pathogenesis. Glycosylceramides are present on the apoplastic monolayer of the lipid bilayer of plant plasma membranes. In this respect, their localization is similar to those of GIPCs, and they face the extracellular milieu (Warnecke & Heinz, 2003; Spassieva & Hille, 2003; Lynch & Dunn, 2004). Glycosylceramides have been implicated in chilling/freezing tolerance. For example, glycosylceramides containing α-OH monounsaturated VLCFAs appear to be detected mostly in chilling-resistant plants (Cahoon & Lynch, 1991; Imai et al., 1995), and their levels have been shown to increase during cold acclimation in rye leaves (Lynch & Steponkus, 1987). By contrast, in chilling sensitive plants, glycosylceramides containing saturated α-OH FA predominate (Imai et al., 1995).

In addition to the FA moiety, the predominance of particular LCBs in the ceramide cores of glycosylceramides may also be important during cold acclimation. Imai et al. (1997) demonstrated the predominance of the cis isomer of 4-hydroxy-8-sphingenine (t18:1Δ8Z) relative to the trans isomer of 4-hydroxy-8-sphingenine (t18:1Δ8E) in chilling-resistant plants (Imai et al., 1997). It has been proposed that the involvement of glycosylceramides in cold acclimation is due to their role in cryo-stability of the membrane. The primary cause of freezing injury is dehydration-induced destabilization of the plasma membrane (Lynch & Steponkus, 1987; Uemura & Steponkus, 1994; Uemura et al., 1995; Spassieva & Hille, 2003; Warnecke & Heinz, 2003) and glycosylceramides can affect cryo-stability in two main ways. Glycosylceramides can (1) influence monolayer fluidity by intra-molecular and inter-molecular lateral hydrogen bond formations leading to a lower gel-to-liquid crystalline transition temperature, and (2) affect the intrinsic curvature of the plasma membrane leading to reductions in the space between the plasma membrane and the endomembranes. This has the effect of increasing lipid de-mixing, which can result in a higher risk of drought-induced recombination and formation of fatal HII phase. The lipid de-mixing can also affect the functionality of membrane proteins (Lynch & Steponkus, 1987; Cahoon & Lynch, 1991; Lynch et al., 1992; Uemura & Steponkus; 1994; Uemura et al., 1995, Spassieva & Hille, 2003; Warnecke & Heinz, 2003).

Glycosylceramides have also been implicated in drought tolerance, in addition to their role in membrane stability during cold acclimation (Warnecke & Heinz, 2003). For example, a lipidomic study of the vacuolar membrane of the leaves of a C3 and a CAM-induced Mesembryanthenum crystallinum (common ice plant) showed that the vacuolar membrane has a higher level of glycosylceramides in the drought-adapted plant (CAM), suggesting a function in drought tolerance (Warnecke & Heinz, 2003). Similarly, when the plasma membrane glycosylceramide content of the resurrection plant, Ramonda serbica (highly adapted to survive in water deficit conditions), was examined, the results showed a higher glycosylceramide content (10.9 mol%) under dessication conditions, and a lower glycosylceramide content (6.6 mol%) under hydrated conditions (Quartacci et al., 2001).

In animal cells, glycosylceramides with a ceramide core consisting of a trihydroxy LCB (t18:0) and α-OH VLCFA have been shown to increase plasma membrane stability and reduce ion permeability. A similar function has also been proposed for plant glycosylceramides (Cahoon & Lynch, 1991; Lynch et al., 1992; Lynch & Dunn, 2004). Aluminium (Al) is highly phytotoxic when present in excessive amounts in acidic soil and is a major limitation for plant growth. The phytotoxicity of Al is due to its ability to induce programmed cell death in roots cells. Zhang et al. (1997) examined the effects of Al on 2 cultivars of wheat (the Al-sensitive Katepwa cultivar and the Al-resistant PT741 cultivar) and showed that when plants were exposed to 20 μM AlCl3 for 3 d, a slight increase in glycosylceramide content was observed in PT741 whereas glycosylceramide content was reduced in Katepwa.

3. Physiological functions of ceramide

The third class of plant sphingolipids, the ceramides, are less documented compared to the GIPCs and glycosylceramides. This may be attributed, in part, to their lesser abundance in plant membranes compared to GIPCs and glycosylceramides. Vesper et al. (1999) estimated that the ceramide content of plant tissues is c. 10–20% of the glycosylceramide content while Wang et al. (2006) observed a level of ceramide in the range of 4–10 mol% of glycosylceramide content. In rice and Arabidopsis, ceramide content was estimated at 6 mol% in leafy stems of rice and between 2–7 mol% in Arabidopsis leaves (Ohnishi et al., 1985; Markham et al., 2006; Markham & Jaworski, 2007). Ceramides are relatively simple compared to GIPCs and glycosylceramides. A ceramide is formed by the N-acylation of a LCB and a FA (Fig. 2). The main FA moieties of plant ceramides are usually very long chain α-OH FAs, especially in Poaceae although some non-hydroxy FAs have also been identified in noticeably large proportions in rice and potato (Table 5) (Fujino et al., 1985; Ohnishi et al., 1985; Bartke et al., 2006). In addition to differences in the VLCFA component, plant ceramides also exhibit differences in the composition of the LCB. In general, the LCBs that predominate in plant ceramides are the trihydroxy-LCBs (Table 6) (Markham et al., 2006; Markham & Jaworski; 2007).

Table 5.

Main characteristics of the fatty acid (FA) moiety of plant ceramides

| Family | Species | Tissue | non-OH | short αOH FA (C<20) | saturated | unsaturated αOH VLCFA | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FA | αOH VLCFA | ||||||

| Poaceae | seed bran* | 28 | 70 | a | |||

| Oryza sativa | endosperm* | 32 | 1.9 | 66.1 | a | ||

| leafy stem | 30 | <0.2 | 66.9 | b | |||

|

| |||||||

| Fabaceae | Pisum sativum | seed* | 7 | 18.6 | 71.4 | c | |

|

| |||||||

| Phaseolus vulgaris | leaf | 100 | d | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Solanaceae | Solanum tuberosum | tuber | 9.5–71.5 | 34.5–53.5 | 16.5–31 | 0.5–8 | e |

|

| |||||||

| Convolvulaceae | Ipomoea batatas | tuber | 37 | 35 | 29 | e | |

The data reported here are expressed in mol% of total ceramide.

References: Fujino et al. (1985)

Ceramide is a well-established inducer of apoptosis/programmed cell death (PCD) in animal cells (Hannun & Obeid, 2008). In plants, the first evidence for the involvement of ceramide in PCD was reported by Liang et al. (2003). For a discussion of plant PCD, readers are referred to excellent reviews by Lam (2004), Reape & McCabe (2008), and Reape et al. (2008). Liang et al. (2003) isolated and characterized the accelerated cell death 5 (acd5) mutant of Arabidopsis and showed that ACD5 is a ceramide kinase. Knockout mutants of acd5 showed enhanced disease symptoms (hypersensitive lesions) during pathogen attack. The authors also showed that ceramide can induce PCD while ceramide-induced PCD can be attenuated by ceramide-1-phosphate. In vitro activity assays using recombinant ACD5 showed that ceramide containing 4-sphingenine (d18:1Δ4E) as the LCB moiety is a better substrate than ceramide containing sphinganine (d18:0) (Liang et al., 2003). ACD5 does not appear to use diacylglycerol and 4-sphingenine (d18:1Δ4E) as substrates, indicating that it is a bona fide ceramide kinase (Liang et al., 2003). Recombinant ACD5 exhibited an alkaline pH optimum at of 8.2 and an optimum temperature of 30°C (Liang et al., 2003). The authors also showed that Ca2+ is a co-factor important for kinase activity. A role for ACD5 in pathogenesis was further supported by the observation that expression of ACD5 was up-regulated when Arabidopsis plants were inoculated with a virulent strain of Pseudomonas syringae compared to an avirulent strain (Liang et al., 2003).

The ability of ceramide to induce PCD was confirmed by another study by Townley et al. (2005) who showed that 50 μM C2-ceramide can induce PCD in Arabidopsis suspension cell cultures and that C2-ceramide-induced elevations in cytosolic-free Ca2+ ([Ca2+]cyt) acts downstream of C2-ceramide. Interestingly, the authors showed that natural α-OH ceramides or synthetic ceramides with longer FA chain length (C6) were less able to induce PCD compared to C2-ceramide. Additionally, it was demonstrated that loss of potassium ions (K+) is a key feature of ceramide-induced PCD in tobacco (Peters & Chin, 2007). More recent work have demonstrated that naturally occurring ceramides in Arabidopsis contain VLCFAs, and the finding that synthetic C2-ceramide can trigger more PCD than synthetic C6-ceramide suggests that hydroxyceramides with VLCFAs may not be active in regulating PCD. This is important as PCD is a process that must be tightly regulated (Lam, 2004; Reape & McCabe, 2008; Reape et al., 2008). It is envisioned that systematic analysis of naturally occurring ceramides will identify the ceramide sub-species that is important in regulating plant PCD.

4. Physiological functions of free LCBs

The fourth class of plant sphingolipids are the free LCBs. The structures of some free LCBs are shown in Fig. 1. The LCBs can also be phosphorylated (LCB-Ps) as part of their metabolism. The free LCBs and LCB-Ps are potentially interesting mediators of cellular responses (Ng et al., 2001; Coursol et al., 2003, 2005; Xiong et al., 2008). One of the earliest indications that free LCBs may have a role to in mediating cellular processes came from a study in oat mesophyll cells where free LCBs like 4-sphingenine (d18:1Δ4E), sphinganine (d18:0) and 4-hydroxysphinganine (t18:0) were shown to modulate redox activity (Dharmawardhane et al., 1989). Interestingly, the authors reported that the effects of the free LCBs on redox activity were inhibitory or stimulatory in the dark and light, respectively. The significance of these results in the physiological context remains to be determined. Free LCBs like 4-sphingenine (d18:1Δ4E) may also regulate vacuolar pyrophosphatase (V-PPase) activity in Chenopodium rubrum suspension cell cultures (Bille et al., 1992). V-PPases are proton pumps present in the vacuolar membrane and they utilize inorganic pyrophosphate to regulate vacuolar and cellular acidity (Maeshima, 2001). Again, the physiological significance of the effects of sphingenine (d18:1Δ4E) on V-PPase remains to be determined.

In mammalian cells, 4-sphingenine (d18:1Δ4E), along with ceramide have been shown to promote cell death. Brodersen et al. (2002) reported that the Arabidopsis accelerated cell death 11 (acd11) mutant exhibits spontaneous cell death. Cloning of the ACD11 gene revealed that it is similar to mammalian glycolipid transfer proteins. In mammalian cells, these glycolipid transfer proteins have been shown to regulate the transport of complex sphingolipids across membranes. The authors showed that ACD11 can serve as a sphingosine transfer protein, but does not appear to transport complex sphingolipids (Brodersen et al., 2002). By contrast, S1P (d18:1Δ4E-1-P) has been shown to exhibit pro-survival activity (Spiegel & Milstien, 2003; Hannun & Obeid, 2008). The pro-survival activity of S1P (d18:1Δ4E-1-P) can be attributed to its ability to suppress ceramide-induced cell death (Cuvillier et al., 1996; Spiegel & Milstien, 2003). This has led to the suggestion that the dynamic balance between cellular levels of sphingolipid metabolites functions to regulate cell fate (`cell death rheostat') although the situation is likely to be highly complex due to the inter-convertibility of sphingolipid metabolites (Spiegel & Milstien, 2003; Futerman & Hannun, 2004; Hannun & Obeid, 2008).

Increases in free LCBs have been shown to be involved in programmed cell death in plants. Tomato plants of the genotype asc/asc are highly sensitive to AAL-toxin produced by the nectrotrophic fungus Alternaria alternata f.sp. lycopersici (Wang et al., 1996; Spassieva et al., 2002). The effect of AAL-toxin and other SAMs is the inhibition of de novo ceramide synthesis. The associated accumulation of free LCBs, 4-hydroxysphinganine (t18:0) and more importantly sphinganine (d18:0) was proposed to lead to the induction of PCD (Wang et al., 1996; Brandwagt et al., 2000). Confirmation of this hypothesis was provided by Spassieva et al. (2002) who showed that AAL-toxin-induced PCD can be attenuated by treating leaf discs with myriocin, an inhibitor of serine palmitoyltransferase (SPT), the enzyme responsible for the formation of 3-keto-sphinganine, a precursor in the de novo pathway of sphingolipid synthesis. Myriocin was able to attenuate AAL-toxin-induced PCD by reducing the accumulation of free sphinganine (d18:0) (Spassieva et al., 2002). Takahashi et al. (2009) reported that infection of Nicotiana benthemiana by the nonhost pathogen Pseudomonas cichorii caused the accumulation of the mRNA for the LCB2 subunit of SPT and that treatment with the myriocin compromised nonhost resistance.

It was reported that the Arabidopsis fumonisin B1 (FB1) resistant mutant (fbr11-1) was unable to accumulate free LCBs and to undergo PCD in the presence of FB1 (Shi et al., 2007). The authors showed that direct feeding of sphinganine (d18:0), 4-hydroxysphinganine (t18:0), and 4-sphingenine (d18:1Δ4E) to Arabidopsis suspension cell cultures resulted in reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, leading to cell death. Interestingly, the authors also demonstrated that sphinganine-1P (d18:0-1-P) can attenuate sphinganine (d18:0)-induce ROS production and PCD (Shi et al., 2008). Tsegaye et al. (2007) also investigated the effects of FB1 on Arabidopsis plants and showed that mutants of LCB phosphate lyase (responsible for the breakdown of LCB phosphates) are hypersensitive to FB1 compared to wild-type plants. The authors showed conclusively that AtDPL is a bona fide LCB phosphate lyase and that mutants of LCB phosphate lyase also accumulated more 4-hydroxy-8-sphingenine-1-P (t18:1-1-P) compared to wild-type. Together, these studies support the involvement of LCB metabolism in regulating responses to pathogens.

In addition to their potential role as cell fate mediators, LCB-Ps have also been shown to be key signalling intermediates in the regulation of stomatal apertures (Ng et al., 2001; Coursol et al., 2003). S1P (d18:1Δ4E-1-P) has long been established as an anti-apoptotic agent in mammalian cells, and reported to be involved in different cellular responses such as proliferation, cytoskeleton organization, differentiation (Cuvillier et al., 1996; Pyne & Pyne, 2000; Spiegel & Milstien, 2003). The bioactivity of S1P (d18:1Δ4E-1-P) has been attributed to its ability to mobilize Ca2+ in mammal cells (Mattie et al., 1994). Ng et al. (2001) provided the first evidence for the presence of S1P (d18:1Δ4E-1-P) in Commelina communis and that S1P (d18:1Δ4E-1-P) is able to induce reductions in stomatal apertures in a dose-dependent manner in C. communis. More recently, Michaelson et al. (2009) showed the presence of trace levels of 4-sphingenine (d18:1Δ4E) in C. Commelina. Ng et al. (2001) also showed that sphinganine-1P (d18:0-1-P) was not able to cause any change in stomatal apertures. These results indicate that bioactivity of S1P (d18:1Δ4E-1-P) is conferred by the Δ4 double bond. Ng et al. (2001) also showed that the effects of S1P (d18:1Δ4E-1-P) on stomatal apertures is Ca2+-dependent as the calcium chelator, EGTA was able to inhibit the effects of S1P (d18:1Δ4E-1-P). They also provided direct evidence that S1P (d18:1Δ4E-1-P) can cause elevations in [Ca2+]cyt, in the form of oscillations. Additionally, they were able to attenuate abscisic acid (ABA)-induced reductions in stomatal apertures with DL-threo-dihydrosphingosine, a competitive inhibitor of sphingosine kinase (SphK). These results suggest that ABA may regulate the activity of SphK, thereby modulating the endogenous levels of S1P (d18:1Δ4E-1-P) in stomatal guard cells (Ng et al., 2001).

The results obtained by Ng et al. (2001) were corroborated by Coursol et al. (2003, 2005) using Arabidopsis. Coursol et al. (2003) showed that ABA can activate SphK rapidly (within 2 min) and that ABA-activation of SphK can be inhibited by the SphK inhibitors, DL-threo-dihydrosphingosine and N,N-dimethylsphingosine. These authors showed that S1P (d18:1Δ4E-1-P) can inhibit the inward-rectifying K+ channels (important for stomatal opening) and activate the slow anion channels (important for stomatal closure). The combined effects of S1P (d18:1Δ4E-1-P) on the ion channels are to reduce the turgor of the pair of guard cells that flank each stomatal pore, leading to reductions in stomatal aperture (Coursol et al., 2003). Interestingly, the authors also showed, using knockout mutants of the α-subunit of heterotrimeric G proteins (gpa1) that ABA activation of SphK activity and S1P (d18:1Δ4E-1-P) regulation of ion channel activities are mediated in part through the heterotrimeric G proteins (Coursol et al., 2003).

More recently, Michaelson et al. (2009) characterized a bona fide Δ4-desaturase from Arabidopsis and showed that it catalyzes the Δ4-desaturation of glycosylceramides. Interestingly, they showed that the Arabidopsis Δ4-desaturase gene is specifically expressed in floral tissues and that knockout (KO) mutants do not appear to exhibit any observable phenotype compared to wild-type (transpirational water loss from detached leaves, ABA-regulation of stomatal apertures, and pollen germination), leading the authors to question the importance of 4-sphingenine (d18:1Δ4E) and S1P (d18:1Δ4E-1-P) in Arabidopsis (see also review by Lynch et al., 2009).

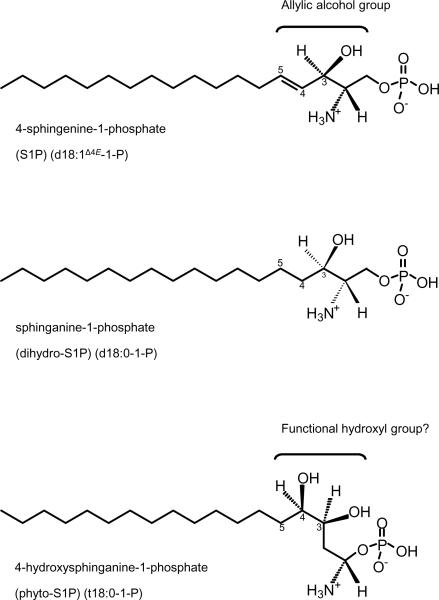

Interestingly, Coursol et al. (2005) showed that 4-hydroxysphinganine-1P (t18:0-1-P) can also inhibit stomatal opening and promote stomatal closure and that the effects of 4-hydroxysphinganine-1P (t18:0-1-P) is also mediated through heterotrimeric G proteins. This raises interesting questions as only trace levels of S1P (d18:1Δ4E-1-P) have been detected in plant extracts. It is possible that the bioactivity exhibited by S1P (d18:1Δ4E-1-P) and 4-hydroxysphinganine-1P (t18:0-1-P) relates to the molecular structure of the LCBs (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Schematic representation of the structure of the long chain base phosphates, 4-sphingenine-1-phosphate (S1P; d18:1Δ4E-1-P), sphingahine-1-phosphate (dihydro-S1P; d18:0-1-P), and 4-hydroxysphinganine-1-phosphate (phyto-S1P; t18:0-1-P). The allylic alcohol group of d18:1Δ4E-1-P comprising the hydroxyl group at C3 and Δ4 double bond (C4) is shown. The position of the carbon atoms are shown in numbers (only positions 3–5 are indicated). In 4-hydroxysphinganine-1-phosphate, a hydroxyl group is present at C4 as opposed to a Δ4 double bond which is characteristic of d18:1Δ4E-1-P.

The bioactivity of sphingenine (d18:1Δ4E) and S1P (d18:1Δ4E-1-P) have been proposed to be due to the presence of the Δ4 double bond (position C4) (Radin, 2004). Analysis of the structure of S1P (d18:1Δ4E-1-P) indicated that presence of an allylic alcohol group composed of the Δ4 double bond (position C4) and a hydroxyl group at C3 (Fig. 5). This allylic alcohol group is absent in sphinganine-1P (d18:0-1-P). Examination of the molecular structure of the 4-hydroxysphinganine-1P (t18:0-1-P) showed the presence of a hydroxyl group at C4. It is possible that the hydroxyl group at C4 in 4-hydroxysphinganine-1P (t18:0-1-P) can confer bioactivity similar to the presence of the allylic alcohol group in S1P (d18:1Δ4E-1-P). The ability of a functional hydroxyl group at C4 to confer bioactivity was demonstrated by Hwang et al. (2001) who showed that substituting the Δ4-double bond of ceramide with a hydroxyl group at C4 resulted in a greater potency for induction of apoptosis in SK-N-BE(2)C and N1E-115 cells. This may provide a plausible explanation for the observed bioactivity of S1P (d18:1Δ4E-1-P) and 4-hydroxysphinganine-1P (t18:0-1-P) in stomatal guard cells of Arabidopsis.

The results from using a pharmacological approach (Ng et al., 2001; Coursol et al., 2003, 2005) have recently been corroborated by Worrall et al. (2008) who reported the cloning of sphingosine kinase 1 (SphK1) from Arabidopsis. The authors showed conclusively that SphK1 is involved in mediating ABA regulation of stomatal apertures and seed germination. Nishikawa et al. (2008) showed using transpirational water loss from detached leaves that mutants of LCB phosphate lyase exhibit slower rates of water loss. The pool of LCB-Ps appear to modulate the overall process of stomatal regulations and/or dehydratation stress since LCB-P catabolism enzymes AtDLP1 (S1P lyase) and AtSSPase (S1P phosphatase) may also be involved in this process (Worrall et al., 2008; Nishikawa et al., 2008). Together, these studies highlight the importance of LCBs and LCB-Ps as key mediators of cellular processes in plant cells. It is envisioned that more research will lead to greater understanding of the roles these sphingolipid metabolites may play in plant cells.

Long chain bases with Δ8 double bond are typical of plants and many fungi. Sperling et al. (1998) identified two orthologues of the sphingolipid Δ8-desaturase with a N-terminal cyt b5 domain in Arabidopsis and in rapeseed. The cyt b5 domain functions as an intermediate electron donor in many acyl desaturase (Sperling et al., 1998; Spassieva & Hille, 2003), and is often associated with the ER in plants (Zhao et al., 2003). The sphingolipidomic study of yeast expressing the Arabidopsis or Brassica sphingolipid Δ8-desaturases showed the production of 4-hydroxy-8-sphingenine (t18:1Δ8) (Sperling et al., 1998). Expression of the sphingolipid Δ8-desaturase homologues from sunflower (Helianthus annuus) and Borago officinalis in yeast also led to the same results (Sperling et al., 2000, 2001). Further investigations using hydroxylase mutant strains sur2Δ allowed the authors to conclude that the substrate of the sphingolipid Δ8-desaturases is 4-hydroxysphinganine (t18:0) (Sperling et al., 2000). As sphinganine (d18:0) does not appear to be a substrate, the Δ8-desaturation reaction was therefore proposed to be downstream of the C4 hydroxylation (Sperling et al., 2000).

Recently, the characterization of the sphingolipid Δ8-desaturase from Stylosanthes hamata showed that it has a substrate preference for the cis-isomer of 4-hydroxysphinganine (Ryan et al., 2007). The nature on which 4-hydroxy-sphinganine (t18:0) is presented to the sphingolipid Δ8-desaturase is unclear, although is has been suggested that glycosylceramides may be substrates (Ryan et al., 2007). da Silva et al. (2006) and Ryan et al. (2007) found that expression in yeast of the sphingolipid Δ8-desaturases from Brassica napus, Arabidopsis thaliana, Helianthus annuus, or Stylosanthes hamata conferred tolerance to cytotoxic levels of Al. When the S. hamata sphingolipid Δ8-desaturase was over-expressed in Arabidopsis, it conferred increased Al-tolerance of 2-wk-old seedlings and enhanced root growth in the presence of Al ranging from 300 to 500 μM (Ryan et al., 2007). This is contrast to the observation that maize transgenic lines expressing the Arabidopsis sphingolipid Δ8-desaturase exhibited enhanced Al-sensitivity when compared to parental lines (da Silva et al., 2006). This may be due to the production of 8 times more trans-isomers of 4-hydroxy-8-sphingenine (t18:1Δ8E) than the parental lines catalyzed by the Arabidopsis sphingolipid Δ8-desaturase whereas the sphingolipid Δ8-desaturase form S. hamata preferentially forms cis-isomers of 4-hydroxy-8-sphingenine (t18:1Δ8Z) (da Silva et al., 2006, Ryan et al., 2007). These observations led the authors to suggest that the stereospecificity of the sphingolipid Δ8-desaturase may be an essential feature of resistance or sensitivity to Al phytotoxicity.

IV. Conclusion

It is apparent from recent work that the field of plant sphingolipids is no longer as enigmatic as it was 10–20 yr ago. A better understanding of the roles that sphingolipids play in plant physiology will come from a greater understanding at the level of transcriptomics, proteomics and perhaps most importantly, at the level of the sphingolipidome. It is envisioned that a clearer picture of the essential roles of plant sphingolipids will emerge as more plant sphingolipidomes are characterized. The coordinated effort to develop community-based standards and protocols along the lines of the LipidMaps consortium (http://www.lipidmaps.org/) will be an important way forward for the plant sphingolipid community.

Acknowledgements

C.K-Y.N. is supported by Research Frontiers Programme grants from Science Foundation Ireland (SFI) (04/BR/0581 and 06/RF/GEN034). Y.A.H. is supported by a National Institute of Health (NIH) grant CA87584.

References

- Acharya JK, Dasgupta U, Rawat SS, Yuan C, Sanxaridis PD, Yonamine I, Karim P, Nagashima K, Brodsky MH, Tsunoda S, et al. Cell-nonautonomous function of ceramidase in photoreceptor homeostasis. Neuron. 2008;57:69–79. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartke N, Fischbeck A, Humpf HU. Analysis of sphingolipids in potatoes (Solanum tuberosum L.) and sweet potatoes (Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam.) by reversed phase high-performance liquid chromatography electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-ESI-MS/MS) Molecular Nutition and Food Research. 2006;50:1201–1211. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200600140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat RA, Panstruga R. Lipid rafts in plants. Planta. 2005;223:5–19. doi: 10.1007/s00425-005-0096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielawski J, Szulc ZM, Hannun YA, Bielawska A. Simultaneous quantitative analysis of bioactive sphingolipids by high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Methods. 2006;39:82–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bille J, Weiser T, Bentrup F-W. The lysolipid sphingosine modulates pyrophosphatase activity in tonoplast vesicles and isolated vacuoles from a heterotrophic cell suspension culture of Chenopodium rubrum. Physiologia Plantarum. 1992;84:250–254. [Google Scholar]

- Bohn M, Heinz E, Lüthje S. Lipid composition and fluidity of plasma membranes isolated from corn (Zea mays L.) roots. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2001;387:35–40. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borner GHH, Sherrier DJ, Weimar T, Michaelson LV, Hawkins ND, MacAskill A, Napier JA, Beale MH, Lilley KS, Dupree P. Analysis of detergent-resistant membranes in Arabidopsis. Evidence for plasma membrane lipid rafts. Plant Physiology. 2005;137:104–116. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.053041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandwagt BF, Mesbah LA, Takken FLW, Laurent PL, Kneppers TJA, Hille J, Nijkamp HJJ. A longevity assurance gene homolog of tomato mediates resistance to Alternaria alternata f. sp. lycopersici toxins and fumonisin B1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science USA. 2000;97:4961–4966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.9.4961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodersen P, Petersen M, Pike HM, Olszak B, Skov S, Ødum N, Jørgensen LB, Brown ER, Mundy J. Knockout of Arabidopsis ACCELERATED CELL-DEATH11 encoding a sphingosine transfer protein causes activation of programmed cell death and defense. Genes and Development. 2002;16:490–502. doi: 10.1101/gad.218202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromley PE, Li YO, Murphy SM, Sumner CM, Lynch DV. Complex sphingolipid synthesis in plants: characterization of inositolphosphorylceramide synthase activity in bean microsomes. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2003;417:219–226. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(03)00339-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahoon EB, Lynch DV. Analysis of glucocerebrosides of rye (Secale cereale L. cv Puma) leaf and plasma membrane. Plant Physiology. 1991;95:58–68. doi: 10.1104/pp.95.1.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantatore JL, Murphy SM, Lynch DV. Compartmentation and topology of glucosylceramide synthesis. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2000;28:748–750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter HE, Brooks S, Gigg RH, Strobach DR, Suami T. Biochemistry of the sphingolipids. XVI. Structure of phytoglycolipid. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1964;239:743–746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter HE, Celmer WD, Galanos DS, Gigg RH, Lands EM, Law JH, Mueller KL, Nakayama T, Tomizawa HH, Weber E. Biochemistry of the sphingolipides. X. Phytoglycolipide, a complex phytosphingosine-containing lipide from plant seeds. Journal of the American Oil Chemists Society. 1958;35:335–343. [Google Scholar]

- Carter HE, Kisic A. Countercurrent distribution of inositol lipids of plant seeds. Journal of Lipid Research. 1969;10:356–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter HE, Koob JL. Sphingolipids in bean leaves (Phaseolus vulgaris) Journal of Lipid Research. 1969;10:363–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Markham JE, Dietrich CR, Jaworski JG, Cahoon EB. Sphingolipid long-chain base hydroxylation is important for growth and regulation of sphingolipid content and composition in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2008;20:1862–1878. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.057851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi MS, Anderson MA, Zhang Z, Zimonjic DB, Popescu N, Mukherjee AB. Neutral ceramidase gene: role in regulating ceramide-induced apoptosis. Gene. 2003;315:113–122. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(03)00721-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coroneos E, Martinez M, McKenna S, Kester M. Differential regulation of sphingomyelinase and ceramidase activities by growth factors and cytokines. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:23305–23309. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.40.23305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coursol S, Fan L-M, Le Stunff H, Spiegel S, Gilroy S, Assmann SM. Sphingolipid signalling in Arabidopsis guard cells involves heterotrimeric G proteins. Nature. 2003;423:651–654. doi: 10.1038/nature01643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coursol S, Le Stunff H, Lynch DV, Gilroy S, Assmann SM, Spiegel S. Arabidopsis sphingosine kinase and the effects of phytosphingosine-1-phosphate on stomatal aperture. Plant Physiology. 2005;137:724–737. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.055806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuvillier O, Pirianov G, Kleuser B, Vanek PG, Coso OA, Gutkind JS, Spiegel S. Suppression of ceramide-mediated programmed cell death by sphingosine-1-phosphate. Nature. 1996;381:800–803. doi: 10.1038/381800a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva ALS, Sperling P, Horst W, Franke S, Ott C, Becker D, Sta A, Lorz H, Heinz E. A possible role of sphingolipids in the aluminium resistance of yeast and maize. Journal of Plant Physiology. 2006;163:26–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dharmawardhane S, Rubinstein B, Stern AI. Regulation of transplasmalemma electron transport in oat mesophyll cells by sphingoid bases and blue light. Plant Physiology. 1989;89:1345–1350. doi: 10.1104/pp.89.4.1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson RC, Lester RL. Sphingolipid functions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2002;1583:13–25. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(02)00210-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson RC, Sumanasekera C, Lester RL. Functions and metabolism of sphingolipids in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Progress in Lipid Research. 2006;45:447–465. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn TM, Lynch DV, Michaelson LV, Napier JA. A post-genomic approach to understanding sphingolipid metabolism in Arabidopsis thaliana. Annals of Botany. 2004;93:483–497. doi: 10.1093/aob/mch071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Bawab S, Bielawska A, Hannun YA. Purification and characterization of a membrane-bound nonlysosomal ceramidase from rat brain. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:27948–27955. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.39.27948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Bawab S, Roddy P, Qian T, Bielawska A, Lemasters JJ, Hannun YA. Molecular cloning and characterization of a human mitochondrial ceramidase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:21508–21513. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002522200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Bawab S, Usta J, Roddy P, Szulc ZM, Bielawska A, Hannun YA. Substrate specificity of rat brain ceramidase. Journal of Lipid Research. 2002;43:141–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujino Y, Ohnishi M, Ito S. Molecular species of ceramide and mono-, di-, tri, and tetraglycosylceramide in bran and endosperm of rice grains. Agricultural and Biological Chemistry. 1985;49:2753–2762. [Google Scholar]

- Futerman AH, Hannun YA. The complex life of simple sphingolipids. EMBO Reports. 2004;5:777–782. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galadari S, Wu BX, Mao C, Roddy P, El Bawab S, Hannun YA. Identification of a novel amidase motif in neutral ceramidase. Biochemical Journal. 2006;393:687–695. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannun YA, Luberto C. Ceramide in the eukaryotic stress response. Trends in Cell Biology. 2000;10:73–80. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(99)01694-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannun YA, Obeid LM. Principles of bioactive lipid signalling: lessons from sphingolipids. Nature Reviews – Molecular Cell Biology. 2008;9:139–150. doi: 10.1038/nrm2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillig I, Leipelt M, Ott C, Zähringer U, Warnecke D, Heinz E. Formation of glucosylceramide and sterol glucoside by a UDP-glucose-dependent glucosylceramide synthase from cotton expressed in Pichia pastoris. FEBS Letters. 2003;553:365–369. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01058-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh TC, Kaul K, Laine RA, Lester RL. Structure of a major glycophosphoceramide from tobacco leaves, PSL-I: 2-deoxy-2-acetamido-D-glucopyranosyl(α1→4)-D-glucuronopyranosyl(α1→2)myoinositol-1-O-phosphoceramide. Biochemistry. 1978;17:3575–3581. doi: 10.1021/bi00610a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh TC, Lester RL, Laine RA. Glycophosphoceramides from plants. Purification and characterization of a novel tetrasaccharide derived from tobacco leaf glycolipids. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1981;256:7747–7755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang O, Kim G, Jang YJ, Kim SW, Choi G, Choi HJ, Jeon SY, Lee DG, Lee JD. Synthetic phytoceramides induce apoptosis with higher potency than ceramides. Molecular Pharmacology. 2001;59:1249–1255. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.5.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang Y-H, Tani M, Nakagawa T, Okino N, Ito M. Subcellular localization of human neutral ceramidase expressed in HEK293 cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2005;331:37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.03.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai H, Ohnishi M, Hotsubo K, Kojima M, Ito S. Sphingoid base composition of cerebrosides from plant leaves. Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry. 1997;61:351–353. [Google Scholar]

- Imai H, Ohnishi M, Kinoshita M, Kojima M, Ito S. Structure and distribution of cerebroside containing unsaturated hydroxy fatty acids in plant leaves. Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry. 1995;59:1309–1313. [Google Scholar]

- Imai H, Yamamoto K, Shibahara A, Miyatani S, Nakayama T. Determining double-bond positions in monoenoic 2-hydroxy fatty acids of glucosylceramides by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Lipids. 2000;35:233–236. doi: 10.1007/BF02664774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito S, Ohnishi M, Fujino Y. Investigation of sphingolipids in pea seeds. Agricultural and Biological Chemistry. 1985;49:539–540. [Google Scholar]

- Kaul K, Lester RL. Characterization of inositol-containing phosphosphingolipids from tobacco leaves: Isolation and identification of two novel, major lipids: N-acetylglucosamidoglucuronidoinositol phosphorylceramide and glucosamidoglucuronidoinositol phosphorylceramide. Plant Physiology. 1975;55:120–129. doi: 10.1104/pp.55.1.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaul K, Lester RL. Isolation of six novel phosphoinositol-containing sphingolipids from tobacco leaves. Biochemistry. 1978;17:3569–3575. doi: 10.1021/bi00610a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi M, Imai H, Naoe M, Yasui Y, Ohnishi M. Cerebrosides in grapevine leaves: distinct composition of sphingoid bases among the grapevine species having different tolerances to freezing temperature. Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry. 2000;64:1271–1273. doi: 10.1271/bbb.64.1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaya K, Ramesha CS, Thompson GA., Jr. On the formation of alpha-hydroxy fatty acids. Evidence for a direct hydroxylation of nonhydroxy fatty acid-containing sphingolipids. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1984;259:3548–3553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kita K, Okino N, Ito M. Reverse hydrolysis reaction of a recombinant alkaline ceramidase of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2000;1485:111–120. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitatani K, Idkowiak-Baldys J, Hannun YA. The sphingolipid salvage pathway in ceramide metabolism and signaling. Cellular Signalling. 2008;20:1010–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laine RA, Renkonen O. Ceramide di- and trihexosides of wheat flour. Biochemistry. 1974;13:2837–2843. doi: 10.1021/bi00711a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam E. Controlled cell death, plant survival and development. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2004;5:305–315. doi: 10.1038/nrm1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leipelt M, Warnecke D, Zähringer U, Ott C, Müller F, Hube B, Heinz E. Glucosylceramide synthases, a gene family responsible for the biosynthesis of glucosphingolipids in animals, plants, and fungi. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:33621–33629. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104952200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang H, Yao N, Song JT, Luo S, Lu H, Greenberg JT. Ceramides modulate programmed cell death in plants. Genes and Development. 2003;17:2636–2641. doi: 10.1101/gad.1140503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch DV. Enzymes of sphingolipid metabolism in plants. Method in Enzymology. 2000;311:130–149. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)11074-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch DV, Caffrey M, Hogan JL, Steponkus PL. Calorimetric and x-ray diffraction studies of rye glucocerebroside mesomorphism. Biophysical Journal. 1992;61:1289–1300. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(92)81937-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch DV, Chen M, Cahoon EB. Lipid signaling in Arabidopsis: no sphingosine? No problem! Trends in Plant Science. 2009;14:463–466. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch DV, Criss AK, Lehoczky JL, Bui VT. Ceramide glucosylation in bean hypocotyls microsomes: evidence that steryl glucoside as glucose donor. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 1997;340:311–316. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.9928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch DV, Dunn TM. An introduction to plant sphingolipids and a review of recent advances in understanding their metabolism and function. New Phytologist. 2004;161:677–702. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.00992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch DV, Steponkus PL. Plasma membrane lipid alterations associated with cold acclimation of winter rye seedlings (Secale cereale L. cv Puma) Plant Physiology. 1987;83:761–767. doi: 10.1104/pp.83.4.761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeshima M. Tonoplast transporters: organization and function. Annual Reviews of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology. 2001;52:469–497. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.52.1.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao C, Obeid LM. Ceramidases: regulators of cellular responses mediated by ceramide, sphingosine, and sphingosine-1-phosphate. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta – Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids. 2008;1781:424–434. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao C, Xu R, Bielawska A, Obeid LM. Cloning of an alkaline ceramidase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. An enzyme with reverse (coA-independent) ceramide synthase activity. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000a;275:6876–6884. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.10.6876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao C, Xu R, Bielawska A, Szulc ZM, Obeid LM. Cloning and characterization of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae alkaline ceramidase with specificity for dihydroceramide. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000b;275:31369–31378. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003683200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]