Abstract

The 22q11.2 deletion is a genetic disorder which is characterized by abnormalities in cardiac functioning, facial structure, neurobehavioral development, T cell functioning, and velopharyngeal insufficiencies. In the presented case study, 22q11.2 deletion was found in a patient who has psychotic symptoms only. A 25-year-old woman with a history of hypoparathyroidism and hypothyroidism presented with auditory hallucinations and persecutory delusions. After three months of treatment with antipsychotic medications, the patient was readmitted with generalized tonic-clonic seizures. The following week, the patient went into sepsis. A fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis revealed the presence of a 22q11.2 microdeletion. This case study suggests that psychotic symptoms can develop prior to the typical symptoms of a 22q11.2 deletion. As such, psychiatrists should test for genetic abnormalities in patients with schizophrenia when these patients present with seizures and immunodeficiencies.

Keywords: 22q11.2 deletion, Schizophrenia, Seizure, Immunodeficiency, Velocardiofacial syndrome

Introduction

The 22q11.2 deletion, also called velocardiofacial syndrome, is a genetic disorder which typically involves cardiac anomalies, facial anomalies, learning difficulties, hypocalcemia, and T cell abnormalities. Additionally, patients with 22q11.2 deletions are at higher risk of developing psychiatric disorders than is the general population. One-third of all individuals with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome develop schizophrenia-like psychotic disorders.1,2 However, it is uncommon for the psychotic symptoms to present as the initial manifestation of a 22q11.2 deletion. As such, genetic abnormalities are generally unsuspected among patients presenting with psychosis, but without velocardiofacial anomalies. A case report of a patient diagnosed with schizophrenia which was later confirmed to be the result of a 22q11.2 deletion is provided.

Case

A 25-year-old female patient was admitted to the psychiatric ward due to auditory hallucinations. Eight months prior to the patient's admittance to the psychiatric ward, she experienced intermittent auditory hallucinations in the form of her ex-boyfriend's voice saying that he would kill her. During the month prior to her admittance to the psychiatric ward, the auditory hallucinations increased in severity and frequency, and the patient developed persecutory delusions. Additionally, the patient came to believe that she had been raped by her boyfriend. The patient also quit her job and withdrew from all social relationships.

The patient had no history or family history of psychiatric problems. The patient had been diagnosed with hypothyroidism and hypoparathyroidism at the age of ten and was being treated with synthyroid and alfacalcidol. The patient's pediatric endocrinologist regularly assessed her thyroid and parathyroid function. After graduating from college, the patient was successfully employed and was maintaining social relationships. Two years prior to the patient's admittance to the hospital, she broke up with her boyfriend.

Upon admittance to the psychiatric ward, the patient was hospitalized for 20 days, during which she was treated with a daily dose of 8 mg of risperidone. During this hospitalization, the patient was diagnosed with schizophrenia. The patient reported that she was no longer having auditory hallucinations 3 weeks after her admission. A computerized tomography (CT) scan of the patient's brain revealed an asymmetric calcification in the bilateral basal ganglia; however, the patient had no history of neurological disorders, including seizures. Additionally, the patient complained of abdominal distension following discharge from the hospital. An abdominal CT scan revealed multiple mesenteric lymphadenopathy; however, the esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy results were normal. The patient underwent screening tests for autoimmune diseases including antinuclear antibodies test, anti-deoxyribonucleic acid test, perinuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies test, and a cytoplasmic anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies test, the results of which were all negative. Echocardiography and electrocardiography were also free of abnormalities. The patient's internist recommended a biopsy for abdominal lymphadenopathy; however, the patient refused.

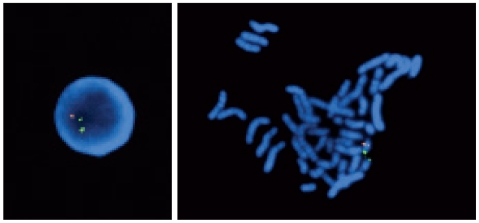

Two months following the patient's initial discharge from the psychiatric ward, the patient was rehospitalized due to the experience of generalized tonic-clonic seizures. A serum chemistry analysis showed normal calcium levels, and a brain CT showed no interval changes compared with the previous scan. The anticonvulsant, lamotrigine, was prescribed, and quetiapine was used in place of the risperidone following the confirmation of seizures with an electro-encephalogram. A week following the rehospitalization, the seizures had ceased; however, the patient developed a fever. The fever subsided after one week and then developed again, resulting in septic shock. No fever focus was found despite various examinations and tests. A T cell test was performed and revealed a decrease in the total T cell count and a deficiency in CD8 cells. A 22q11.2 microdeletion was confirmed by a fluorescent in situ hybridization analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Result of fluorescent in situ hybridization analysis using a HIRA probe (110 kb). Chromosome 22q13 was labeled in green as a control. An orange signal indicates a locus at 22q11.2. There's only one orange signal. The absence of orange signal indicates of the deletion of the HIRA locus at 22q11.2. HIRA: histone cell cycle regulation defective homolog A.

Discussion

In this patient, psychotic symptoms preceded the other symptoms of 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Patients with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome generally have recurrent infections, as well as endocrine and neuropsychiatric abnormalities.3 However, it is uncommon for psychotic features to be the first manifestation of 22q11.2 microdeletion. Additionally, the patient's history of hypoparathyroidism was not indicative of genetic abnormalities. Several studies have reported higher rates of psychotic disorders among patients with a 22q11.2 deletion than in the general population.1,2 Psychotic symptoms typically begin in late adolescence and adulthood. The prevalence rate for psychosis among individuals with the 22q11.2 deletion is approximately 30%,1,2,4 and schizophrenia has been described as a behavioral phenotype of a 22q11.2 deletion.5 However, prevalence of a 22q11.2 deletion among patients with schizophrenia is unclear. Some investigators6-8 have reported greater than 2% prevalence for 22q11.2 deletions among patients with schizophrenia, while other investigators report a less than 1% prevalence rate.9-12 One study12 reported that no 22q11.2 deletions were detected in the approximately 300 patients with schizophrenia who were screened for the study, and other studies9,10 have reported that only one of approximately 300 patients showed a 22q11.2 deletion.

The biological mechanisms which are responsible for the development of psychotic features in patients with a 22q11.2 deletion have not been fully investigated. Catechol-o-methyltransferase is a potential cause of psychotic symptoms,6 which was not replicated in the 22q11.2 deleted patients with schizophrenia or in schizophrenic patients. The PRODH and GNB1L genes are other candidates which may be associated with the development of schizophrenia in patients with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome.13

In the present case, the patient was diagnosed with schizophrenia with well-controlled hypocalcemia. In spite of the patient's history of hypoparathyroidism and abdominal lymphadenopathies, she did not have facial anomalies or cardiac malformations. Additionally, the patient displayed appropriate levels of social functioning prior to the onset of the psychotic symptoms. Additional clinical findings, including seizures, frequent urinary tract infections, and recurrent septicemia, were inconsistent with a diagnosis of a 22q11.2 genetic abnormality.

It is difficult to determine whether the patient's seizures were caused by risperidone. However, it is known that the patient's first seizure occurred following treatment with antipsychotic medication. It is also possible that the seizure was a manifestation of the 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Several case reports have presented seizures as a manifestation of 22q11.2 deletions.14,15 Additionally, it is known that antipsychotic medications may lower the seizure threshold; however, the possibility of developing seizures associated with risperidone is relatively low.16,17 The patient also had calcifications in the basal ganglia, and, as such, the antipsychotic may have further decreased the seizure threshold.

This case reveals that psychotic symptoms may serve as the initial manifestation of 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. It is uncommon for a patient with a 22q11.2 deletion to show no velocardiofacial anomalies, especially in Korea.18 As such, psychiatrists should test for genetic abnormalities among patients with schizophrenia when these patients also present with seizures and immunodeficiencies.

References

- 1.Pulver AE, Nestadt G, Goldberg R, Shprintzen RJ, Lamacz M, Wolyniec PS, et al. Psychotic illness in patients diagnosed with velo-cardio-facial syndrome and their relatives. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1994;182:476–478. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199408000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murphy KC, Jones LA, Owen MJ. High rates of schizophrenia in adults with velo-cardio-facial syndrome. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:940–945. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roubertie A, Semprino M, Chaze AM, Rivier F, Humbertclaude V, Cheminal R, et al. Neurological presentation of three patients with 22q 11 deletion (CATCH 22 syndrome) Brain Dev. 2001;23:810–814. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(01)00258-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shprintzen RJ, Goldberg R, Golding-Kushner KJ, Marion RW. Late-onset psychosis in the velo-cardio-facial syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1992;42:141–142. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320420131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gothelf D, Schaer M, Eliez S. Genes, brain development and psychiatric phenotypes in velo-cardio-facial syndrome. Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2008;14:59–68. doi: 10.1002/ddrr.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karayiorgou M, Morris MA, Morrow B, Shprintzen RJ, Goldberg R, Borrow J, et al. Schizophrenia susceptibility associated with interstitial deletions of chromosome 22q11. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:7612–7616. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wiehahn GJ, Bosch GP, du Preez RR, Pretorius HW, Karayiorgou M, Roos JL. Assessment of the frequency of the 22q11 deletion in Afrikaner schizophrenic patients. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2004;129B:20–22. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.20168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sporn A, Addington A, Reiss AL, Dean M, Gogtay N, Potocnik U, et al. 22q11 deletion syndrome in childhood onset schizophrenia: an update. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9:225–226. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arinami T, Ohtsuki T, Takase K, Shimizu H, Yoshikawa T, Horigome H, et al. Screening for 22q11 deletions in a schizophrenia population. Schizophr Res. 2001;52:167–170. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(00)00192-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ivanov D, Kirov G, Norton N, Williams HJ, Williams NM, Nikolov I, et al. Chromosome 22q11 deletions, velo-cardio-facial syndrome and early-onset psychosis. Molecular genetic study. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;183:409–413. doi: 10.1192/bjp.183.5.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horowitz A, Shifman S, Rivlin N, Pisanté A, Darvasi A. A survey of the 22q11 microdeletion in a large cohort of schizophrenia patients. Schizophr Res. 2005;73:263–267. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoogendoorn ML, Vorstman JA, Jalali GR, Selten JP, Sinke RJ, Emanuel BS, et al. Prevalence of 22q11.2 deletions in 311 Dutch patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2008;98:84–88. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prasad SE, Howley S, Murphy KC. Candidate genes and the behavioral phenotype in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2008;14:26–34. doi: 10.1002/ddrr.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kao A, Mariani J, McDonald-McGinn DM, Maisenbacher MK, Brooks-Kayal AR, Zackai EH, et al. Increased prevalence of unprovoked seizures in patients with a 22q11.2 deletion. Am J Med Genet A. 2004;129A:29–34. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tonelli AR, Kosuri K, Wei S, Chick D. Seizures as the first manifestation of chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome in a 40-year old man: a case report. J Med Case Reports. 2007;1:167. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-1-167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pisani F, Oteri G, Costa C, Di Raimondo G, Di Perri R. Effects of psychotropic drugs on seizure threshold. Drug Saf. 2002;25:91–110. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200225020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gonzalez-Heydrich J, Pandina GJ, Fleisher CA, Hsin O, Raches D, Bourgeois BF, et al. No seizure exacerbation from risperidone in youth with comorbid epilepsy and psychiatric disorders: a case series. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2004;14:295–310. doi: 10.1089/1044546041649075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhang SY, Kim CY, Joo YH, Seu EJ, Ryu HE. A case report of schizophrenia patient with 22q11 deletion syndrome. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 2003;42:528–531. [Google Scholar]