Abstract

Antisense oligonucleotides (AOs) have the capacity to alter the processing of pre-mRNA transcripts in order to correct the function of aberrant disease-related genes. Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a fatal X-linked muscle degenerative disease that arises from mutations in the DMD gene leading to an absence of dystrophin protein. AOs have been shown to restore the expression of functional dystrophin via splice correction by intramuscular and systemic delivery in animal models of DMD and in DMD patients via intramuscular administration. Major challenges in developing this splice correction therapy are to optimize AO chemistry and to develop more effective systemic AO delivery. Peptide nucleic acid (PNA) AOs are an alternative AO chemistry with favorable in vivo biochemical properties and splice correcting abilities. Here, we show long-term splice correction of the DMD gene in mdx mice following intramuscular PNA delivery and effective splice correction in aged mdx mice. Further, we report detailed optimization of systemic PNA delivery dose regimens and PNA AO lengths to yield splice correction, with 25-mer PNA AOs providing the greatest splice correcting efficacy, restoring dystrophin protein in multiple peripheral muscle groups. PNA AOs therefore provide an attractive candidate AO chemistry for DMD exon skipping therapy.

Introduction

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a fatal muscle degenerative disease that arises from mutations, typically large deletions, in the DMD gene resulting in out-of-frame dystrophin transcripts and ultimately in the absence of functional dystrophin protein. Antisense oligonucleotides (AOs) are short single-stranded nucleic acids with the ability to effect splice correction of aberrant disease-related gene pre-mRNA transcripts in order to restore their function.1 Such AOs have been shown to modify splicing by exon inclusion or in the case of DMD via the forced exclusion of specific dystrophin exons within out-of-frame transcripts, thereby restoring the open reading frame to generate a shortened but functional dystrophin protein product.2,3,4,5,6,7,8

Proof-of-principle for the exploitation of AOs as splice correcting therapeutic agents for DMD was successfully demonstrated in mdx mice carrying a nonsense mutation in exon 23 of the DMD gene, where AOs were shown to restore the expression of functional dystrophin protein following direct intramuscular and systemic injection.4,5 More recently, a similar local 2'-O-methyl phosphorothioate RNA (2'OMePS) AO injection protocol was shown to successfully correct the expression of a mutated dystrophin transcript in DMD patients via the effective skipping of human dystrophin exon 51.9 Systemic correction of dystrophin expression will be important for therapeutic correction in DMD patients. However, in animal models this has proved considerably more challenging. As previously reported, 2'OMePS AOs administered intravenously to mdx mice were shown to restore dystrophin expression in multiple peripheral muscles but splice correcting efficacy was poor with significant inter-muscle variation.5 The use of alternative chemistry phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomer (PMO) has been shown to yield more efficient systemic dystrophin restoration using a high-dose multi-injection protocol, although the levels of restored dystrophin protein were low and correction in cardiac muscle was not seen.10 Several groups have recently reported that systemic correction of dystrophin expression, including in cardiac muscle tissue, can be dramatically improved with the use of peptide-PMO conjugates.11,12,13 In each of these studies, short arginine-rich transduction peptides were covalently linked to the PMO to enhance cellular AO uptake resulting in improved systemic splice correction and amelioration of the disease phenotype.

The 2'OMePS and PMO AO chemistries are the two in most widespread current use;2,3,4,5,10,13,14 the former being utilized in clinical studies undertaken in the Netherlands9 whereas the latter is the therapeutic agent of choice by the UK MDEX Consortium in their clinical trials. Nevertheless other AO chemistries have the capacity for effective pre-mRNA splice correction, which may offer particular advantages under certain conditions. Notable among these are peptide nucleic acid (PNA) AOs. PNAs are nucleic acid analogues formed by replacing the sugar phosphate backbone of the native nucleic acid with a synthetic peptide backbone, which is stable and resistant to proteases and nucleases and shows high-binding affinity and sequence specificity.15 PNAs have been successfully used to antagonize microRNA activity16 and to downregulate viral transcripts,17,18 and we have previously demonstrated dystrophin splice correcting PNA activity following local intramuscular delivery in mdx mice.8 Here, we investigate further the potential of PNA AOs as splice correcting therapeutic agents for DMD by studying their effects in aged animals, their long-term activity in mdx mice, the activity of their peptide conjugates and also the potential for systemic splice correction by optimization of PNA length and dose.

Results

Effective dystrophin exon skipping induced by neutral PNA AOs in aged mdx mice

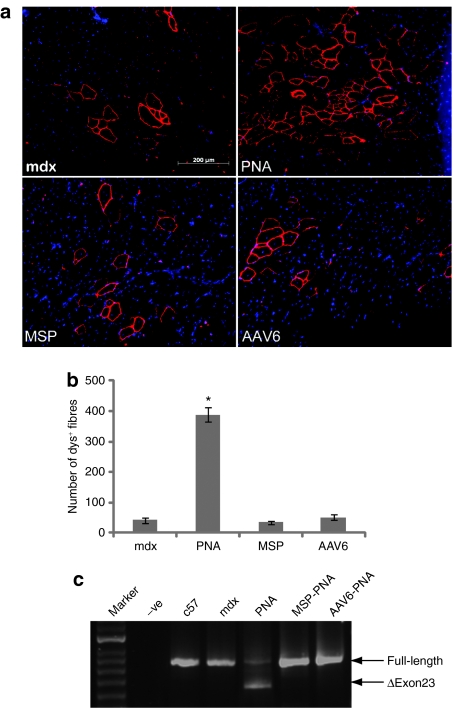

We have previously evaluated neutral PNA20 AOs, which were targeted at the murine DMD exon 23 5′-splice donor site (see Table 1 for AO and peptide sequence information),19 and their peptide conjugates in different ages of mdx mice by intramuscular injection.8 Here, we aim to further evaluate the potential of PNA AOs as splice correcting therapeutic agents for DMD. We first wished to study the potential and applicability of neutral PNA AOs and their peptide conjugate derivatives for the treatment of older DMD subjects by evaluating these compounds in aged mdx mice. Five microgram of neutral PNA AO and muscle-specific peptide—and adeno-associated virus 6 functional domain-conjugated PNA AOs, as previously reported,8 were studied in 12-month-old mdx mice by intramuscular injection into tibialis anterior (TA) muscles. Two weeks following AO injection, dystrophin-positive fibers were identified by immunohistochemical staining in muscle tissue sections. Surprisingly the number of dystrophin-positive fibers detected in neutral PNA AO-treated TA muscles (388 ± 24) was significantly higher than those treated with peptide-conjugated AOs (52 ± 8) and untreated, age-matched control mdx mice (42 ± 8) (Figure 1a,b). Unexpectedly, both tested PNA-peptide conjugates failed to induce as effective exon skipping in old mice as they had previously been shown to do in younger mdx mice,8 findings corroborated at the RNA level by the reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) data (Figure 1c,d).

Table 1.

PNA and peptides used as PNA conjugates: nomenclatures and sequences

Figure 1.

Restoration of dystrophin expression in aged mdx mice. Restoration of dystrophin expression in aged mdx mice following single 5-µg intramuscular injections of PNA AOs in 12-month-old mdx mice. (a) Immunofluorescent staining for dystrophin in mdx TA muscles following 5 µg injection of PNA AO and peptide-PNA conjugates. Nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2 phenylindole. (b) Quantitative evaluation of total dystrophin-positive fibers in treated TA muscles 2 weeks after single intramuscular injection of 5 µg PNA AO and MSP- and AAV6-PNA conjugates. Neutral PNA AO showed significant increase of dystrophin-positive fibers compared with untreated age-match control and peptide-PNA conjugates (*P < 0.05). (c) RT-PCR for detecting exon skipping efficiency at the RNA level, which is shown by shorter exon-skipped bands (indicated by the numbered δexon23– for exon 23 skipping). AAV, adeno-associated virus; AO, antisense oligonucleotide; MSP, muscle-specific peptide; PNA, peptide nucleic acid; RT-PCR, reverse transcription-PCR; TA, tibialis anterior.

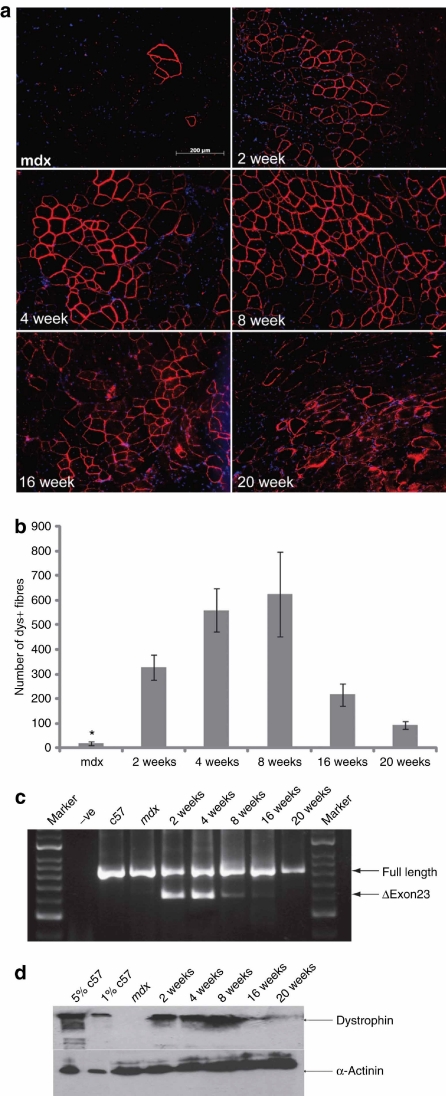

PNA AOs induce long-term production of dystrophin protein following intramuscular delivery in mdx mice

As previously reported, neutral PNA AOs can induce significant exon skipping in mdx mice at a 2-week time point following a single intramuscular injection.8 We therefore wished to examine the duration of the therapeutic effect induced by PNA AOs. TA muscles of 2-month-old mdx mice were injected with 5 µg of neutral PNA20 AO and the efficacy of exon skipping was detected at different time points: 4, 8, 16 and 20 weeks postinjection. Treated TA muscles were harvested and dystrophin expression was examined by immunohistochemical staining. This analysis revealed >650 dystrophin-positive fibers distributed throughout transverse muscle sections at the 8-week time point, when the number of dystrophin-positive fibers peaked (Figure 2a,b). And the PNA splice correction effect was found to persist for >20 weeks, although by week 16 following AO administration, the dystrophin sarcolemmal staining had become discontinuous. Nevertheless the organized muscle structure and dystrophin-positive fibers were still visible at 20 weeks (Figure 2a). The RT-PCR and western blot results were consistent with those of the immunostaining. RT-PCR indicated that the peak induction time for correction at the RNA level was at 4 weeks after injection, where about 50% of the targeted dystrophin transcripts showed splice correction, whereas at the 8-week time point the level of dystrophin protein restored reached ~20% of normal levels. Western blotting showed considerably reduced levels of dystrophin protein by 20 weeks postadministration (Figure 2c).

Figure 2.

Long-term correction of dystrophin expression following intramuscular PNA administration in mdx mice. (a) Immunohistochemistry for dystrophin induction in TA muscles of 2-month-old mdx mice 2, 4, 8, 16, and 20 weeks after one single intramuscular injection of 5 µg PNA AO (bar = 200 µm). (b) Quantitative evaluation of total dystrophin-positive fibers in TA muscles at different time points after a single intramuscular injection of PNA AO. All groups showed significant improvement in comparison with age-matched untreated mdx mice (*P < 0.05). (c) RT-PCR to detect exon skipping efficiency at the RNA level demonstrated up to 50% exon 23 skipping in the TA muscle treated with PNA AO at 4 weeks after injection. This is shown by shorter exon-skipped bands (indicated by δexon23– for exon 23 skipping). (d) Western blot analysis. Western blot for treated TA muscles at different time points after single intramuscular injection of PNA AOs. Total protein was extracted from TA muscles of 2-month-old mdx mice at 2, 4, 8, 16, and 20 weeks after a single intramuscular injection with 5 µg PNA AOs. Fifty microgram of total protein from untreated mdx mice TA muscles and treated muscle samples was loaded. 2.5- and 0.5-µg total protein (5 and 1%, respectively) from C57BL6 TA muscles were loaded as normal controls. No visible difference in the size of dystrophins between muscle treated with PNA and muscle from the normal C57BL6 mouse. α-Actinin was used as a loading control. AO, antisense oligonucleotide; PNA, peptide nucleic acid; RT-PCR, reverse transcription-PCR; TA, tibialis anterior.

In an earlier report, we had identified that peptide-conjugated PNA AOs had the capacity for dystrophin splice correction in mdx mice.8 In particular, a muscle-specific peptide, previously reported as having 50–100-fold enhanced skeletal and cardiac muscle-binding affinities,20 was shown to have appreciable dystrophin splice correcting efficacy in old mdx mice.8 Here, we compared the effects of this muscle-specific peptide-PNA conjugate over a 20-week time course directly with neutral PNA AOs. However, the efficacy of this peptide conjugate was not as great as that of neutral PNA, with the peak in dystrophin restoration reached at 4 weeks after injection and only a low number of dystrophin-positive fibers detectable at 16 weeks (Supplementary Figure S1a,b). We also examined the activity of several other peptide-PNA conjugates including R9F2- and (RXR)4-PNA conjugates for their long-term effects in mdx mice. These showed much reduced activity than observed for neutral PNA AOs (data not shown).

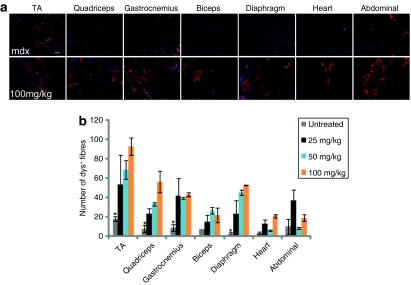

Systemic evaluation of neutral PNA AOs by intravenous injection in mdx mice

To develop AO splice correction therapy for DMD it is essential to establish effective systemic dystrophin correction because DMD is a systemic disease that affects all skeletal muscles, including the diaphragm, and cardiac muscle. Other AO chemistries, including 2'OMePS and PMO chemistries, have been reported to yield variable dystrophin splice correction following intravenous systemic delivery in mdx mice,5,10 with very high doses being required to detect appreciable splice correcting efficacy. Here, we wished to evaluate the potential of neutral PNA AOs for systemic splice correction in body-wide muscles, and initially evaluated a dose-response using single intravenous PNA doses of 25, 50, and 100 mg/kg administered to adult mdx mice via tail vein injections. Dystrophin expression was studied by immunostaining of muscle tissue sections from various peripheral muscles (including quadriceps, gastrocnemius, biceps, abdominal wall, and diaphragm) and heart muscle 2 weeks after AO administration. The immunostaining results demonstrated that the dystrophin-positive fibers were sparsely distributed throughout the transverse sections, some of which were weakly stained with discontinuous membrane staining (Figure 3a). The number of dystrophin-positive fibers detected was low but nevertheless showed a significant increase at 25, 50, and 100 mg/kg doses compared with untreated control mice in all muscle groups except for abdominal muscles and heart (Figure 3b). Whereas no significant difference can be seen when a single 15 mg/kg dose was applied compared with untreated mdx mice (data not shown). An evident dose-dependent response was only observed in quadriceps and diaphragm but not in other muscle groups over the dose range tested. RT-PCR results revealed <5% exon skipping in TA and gastrocnemius muscles at 25, 50, and 100 mg/kg doses and trace amounts or no exon23 skipped transcript product detected in other tissues. Consistent with the RT-PCR, the level of dystrophin protein was undetectable by western blotting at all doses (data not shown). Measures of serum creatine kinase and aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase enzyme levels showed that there was no significant difference between treated and untreated controls (Supplementary Figure S2a,b).

Figure 3.

Systemic delivery of PNA AOs for dystrophin splice correction in mdx mice. (a) Immunohistochemistry for dystrophin induction in body-wide muscles of 2-month-old mdx mice 2 weeks after one single intravenous injection of PNA20 AOs at 100 mg/kg dose (bar = 200 µm). (b) Quantitative evaluation of total dystrophin-positive fibers in all tested muscles from TA, quadriceps, gastrocnemius, biceps, diaphragm, heart, and abdominal wall 2 weeks after single intravenous injection of different doses of PNA AOs. The data indicated significant difference between the treatments with PNA20 AOs at different doses compared with untreated age-matched control mdx mice (*P < 0.05). AO, antisense oligonucleotide; PNA, peptide nucleic acid; TA, tibialis anterior.

Given the identification of a series of novel cell-penetrating peptides generated by mutagenesis of an R6-penetratin peptide, and encouraging dystrophin splice correcting data resulting from the conjugation of these peptides to PNA AOs,21,22 we therefore decided to evaluate these novel conjugates via systemic delivery in mdx mice. The optimal peptide identified following intramuscular administration into mdx mice was Pip2b.21 So we evaluated the efficacy of Pip2b-PNA conjugates via systemic delivery in 2-month-old adult mdx mice and compared this directly with an (RXR)4-PNA AO conjugate containing a well studied (RXR)4 arginine-rich peptide, which is known to function well when conjugated to PMO, as a control.13 A relatively low single dose of 25 mg/kg was evaluated, a dose known to generate efficient systemic splice correction with peptide-PMO conjugates. However, the results of this study indicated that both peptide conjugates were only very weakly effective at this dose (Supplementary Figure S3a). The number of dystrophin-positive fibers detected per muscle section was below 50 in all peripheral muscle groups studied and also in heart muscle (Supplementary Figure S3b). RT-PCR showed trace amounts or no exon skipping and the protein was undetectable by western blot (data not shown).

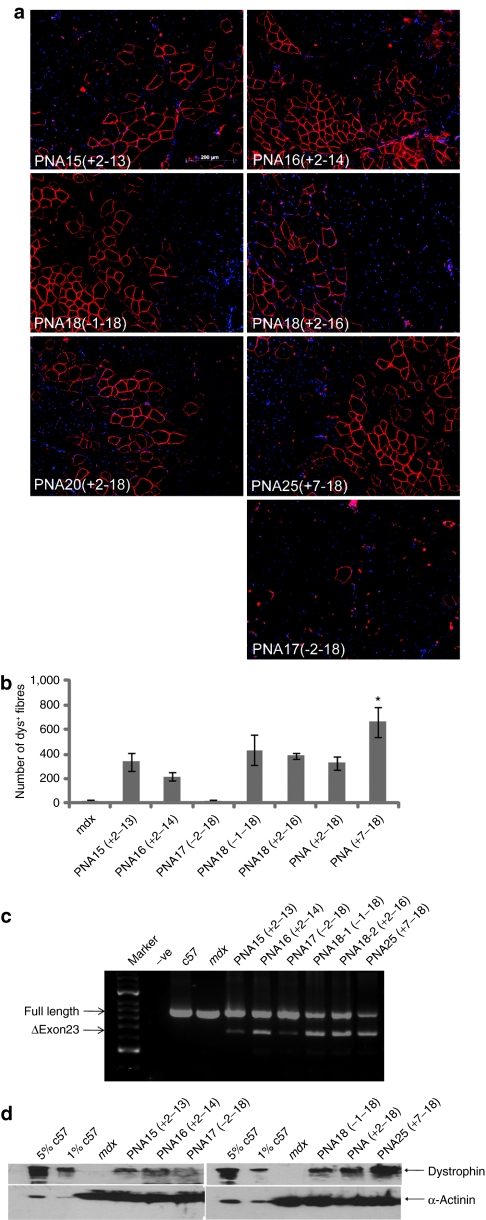

Longer 25-mer PNA AOs are more effective for dystrophin splice correction in vivo

A possible factor to account for the relatively poor systemic activity of the PNA AOs and peptide-PNA AO conjugates compared with encouraging data published for PMO (naked or peptide-conjugated) under similar conditions,10,12,13 is the length of the PNA AO. In comparable studies the relevant neutral PMO were 25-mers, whereas the PNAs used in all DMD studies to date have been 20-mers. It is known that oligonucleotide length can influence splice correcting efficacy; for example the influence of 2'OMePS AO length on bioactivity has been reported23 and the optimal PMO for skipping of human dystrophin exons were found to be length-dependent,24 and in the case of human exon 51 the optimal PMO was a 30-mer compound.25 Thus, we decided to evaluate the effects of PNA length on dystrophin splice correction, initially following intramuscular injection of PNA AOs in adult mdx mice. An earlier study of PNA splice correction in positive read-out EGFP transgenic mice carrying an aberrant human β-globin intron inserted in the EGFP gene had reported successful splice correction using an 18-mer PNA.26 Therefore, we decided to test both shorter and longer PNA AOs than the original 20-mer. PNA AOs of 15, 16, 17, 18 (two evaluated), 20, and 25 nucleotides in length were studied (see Table 1). The TA muscles were harvested 2 weeks after the treatment with various PNA AOs. Two 18-mer PNA AOs showed comparable activity in terms of the number of dystrophin-positive fibers detected by immunohistochemistry compared with the original PNA20 AO (329 ± 51). About 434 ± 124 dystrophin-positive fibers was detected with PNA18-1, whereas an almost completely overlapping PNA18-2 (shifted by two nucleotides) showed slightly reduced activity (387 ± 26), which confirmed that the AO sequence is also a critical factor. All AOs shorter than 18 nucleotides demonstrated reduced activity. In contrast, PNA25 AO showed dramatically enhanced activity, yielding an approximately twofold increase in the number of dystrophin-positive fibers following a single intramuscular injection of 5 µg of AO (663 ± 122) (Figure 4a,b). Approximately 40–50% dystrophin exon skipping was induced by PNA18-1, PNA18-2, and PNA25 AOs and up to 20% splice correction induced by the PNA AOs shorter than 18-mer as shown by RT-PCR (Figure 4c). Western blotting confirmed the relative efficacies shown by the immunostaining and RT-PCR data, with up to 10% dystrophin protein restored with PNA25 AO treatment, whilst as high as 3% was detected with other shorter PNA AOs (Figure 4d).

Figure 4.

Effects of PNA length on splice correction activity in mdx mice. We evaluated the effect of AO length on PNA splice correcting activity in mdx mice by studying the activities of seven PNA compounds of 15, 16, 17, 18-1, 18-2, 20, and 25 nucleotides in length, respectively (see Table 1). (a) Immunohistochemistry for dystrophin induction in TA muscles of 2-month-old mdx mice 2 weeks after one single intramuscular injection of 5 µg different lengths of PNA AO (bar = 200 µm). (b) Quantitative evaluation of total dystrophin-positive fibers in TA muscles 2 weeks after a single intramuscular injection of various PNA AOs. TA muscles treated with PNA25 showed significant improvement in comparison with age-matched untreated mdx mice and other PNA AOs (*P < 0.05). (c) RT-PCR to detect exon skipping efficiency at the RNA level demonstrated up to 50% exon 23 skipping in the TA muscle treated with PNA25 AO at 2 weeks after injection. This is shown by shorter exon-skipped bands (indicated by δexon23– for exon 23 skipping). (d) Western blot analysis. Western blot for treated TA muscles after single intramuscular injection of various PNA AOs. Total protein was extracted from TA muscles of 2-month-old mdx mice 2 weeks after a single intramuscular injection with 5 µg different PNA AOs. Fifty microgram total protein from untreated mdx mice TA muscles and treated muscle samples was loaded. 2.5- and 0.5-µg total protein (5 and 1%, respectively) from C57BL6 TA muscles were loaded as normal controls. No visible difference in the size of dystrophins between muscle treated with PNA and muscle from the normal C57BL6 mouse. α-Actinin was used as a loading control. AO, antisense oligonucleotide; PNA, peptide nucleic acid; RT-PCR, reverse transcription-PCR; TA, tibialis anterior.

Given the significant improvement in splice correcting activity of the longer PNA compounds, we wished to know whether such AO length-dependence extended to the activity of PNA conjugates. We therefore studied 25-mer PNA versions of the two previously studied PNA conjugates—Pip2b and (RXR)4—by intramuscular injection in adult mdx mice. Surprisingly, the longer PNA AO conjugates appeared to have no beneficial effect as determined by the number of dystrophin-positive fibers, and in the case of the Pip2b-PNA25 conjugate the longer compound was significantly inferior to that of the naked PNA25 (Supplementary Figure S4a–c).

Evaluation of longer PNA25 AOs for systemic splice correction in mdx mice

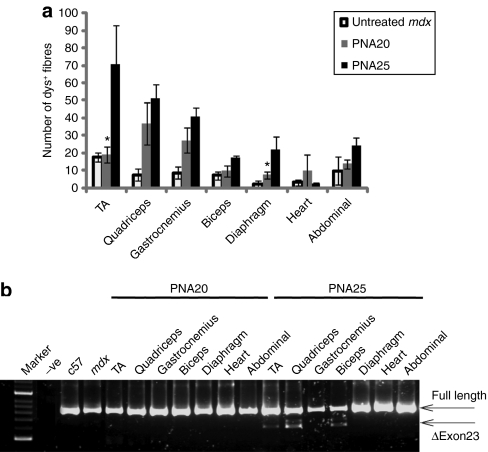

Given the twofold improved activity of the PNA25 AO following intramuscular administration, we wished to study whether systemic administration of this longer PNA AO would have more efficacious body-wide splice correction activity compared with original PNA20 in adult mdx mice. We therefore carried out tail vein injections in mdx mice using a multiple injection low dose regimen, reasoning that it will be a more cost-effective way to discriminate between the longer PNA25 and original PNA20. Three weekly injections of PNA25 and PNA20 AOs at 15-mg/kg dose protocol were applied to 2-month-old mdx mice by intravenous injection. Two weeks after the last injection, all body-wide muscles were harvested and assayed by immunohistochemistry, which showed increased exon skipping efficiency with PNA25 AO compared with the PNA20 AO. Up to 100 dystrophin-positive fibers were seen in TA muscles treated with PNA25 (Figure 5a) and RT-PCR showed about 10% exon skipping in TA and quadriceps muscles with PNA25, greater than that observed with PNA20 AO albeit that the overall level is low (Figure 5b). However, at this dose, no phenotypic improvement was observed, as shown by grip strength test and blood biochemical parameters i.e., creatine kinase level and aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Systemic restoration of dystrophin expression by 25-mer PNA AO compounds. We evaluated the systemic splice correcting ability of PNA25 compounds following their improved activity in an intramuscular screen. (a) Quantitative evaluation of total dystrophin-positive fibers in all tested muscles from TA, quadriceps, gastrocnemius, biceps, diaphragm, heart, and abdominal wall 2 weeks after single intravenous injection of PNA AOs. The data indicated that there was significant difference between the treatment with PNA25 and PNA20 AOs in some muscle groups (*P < 0.05) (b) RT-PCR to detect exon skipping efficiency at the RNA level demonstrated up to 10% exon 23 skipping in the quadriceps muscle treated with PNA25 AO. This is shown by shorter exon-skipped bands (indicated by δexon23– for exon 23 skipping). AO, antisense oligonucleotide; PNA, peptide nucleic acid; RT-PCR, reverse transcription-PCR; TA, tibialis anterior.

Although the intramuscular route represents a relatively simple method for in vivo screening of splice correcting AO activity in the context of DMD, it requires no transvascular escape of the AO within the muscle in contrast to the intravenous route. Therefore peptides which show little efficacy via intramuscular injection may still have utility for vascular escape and muscle delivery following vascular administration. Thus despite their poor intramuscular efficacies, we also studied the systemic effects of the Pip2b- and (RXR)4-PNA25 conjugates at single-systemic doses of 25 mg/kg in adult mdx mice. However, the results here were in accord with the intramuscular studies and both PNA conjugates showed poor efficacy (Supplementary Figure S5a,b).

Discussion

We have previously identified that alternative chemistry PNA AOs have potential as dystrophin splice correcting agents.8 In this study, we have further investigated the potential of these PNA AOs for splice correction of the DMD gene in the mdx mouse model of DMD under a number of conditions. We showed that PNAs have the ability to restore dystrophin expression in aged mdx mice and also for a period of approaching 5 months in 2-month-old mdx mice following single intramuscular AO injections. We also show that PNA length and sequence/position are critical factors influencing in vivo AO bioactivity and exon skipping efficacy, and found that PNA25 AOs provide up to a twofold increase in dystrophin splice correction following intramuscular injection compared with original PNA20 AOs. The benefit of increased length however, does not appear to extend to peptide-conjugated PNAs, which show no increased activity when conjugated to the longer PNA. Finally, we showed that the longer PNA AOs when administered systemically using a multi-injection protocol are able to yield greater dystrophin splice correction than original PNA20 AO in multiple peripheral muscle groups confirming their potential as possible therapeutic agents for DMD.

Our findings highlight the potential clinical utility of PNA AOs for long-term dystrophin correction in DMD patients in whom muscle degeneration is already proceeding. The efficacy of PNA splice correction in 12-month-old mdx mice, suggests that despite increasing muscle degeneration and fibrotic change in older mice, effective exon skipping is possible and that the PNA AO might have more favorable potential application in aged mdx mice compares with previous data published using PMO in older mdx mice.10,27 The duration of splice correcting effects is likely determined by a combination of the high-PNA intracellular stability15,28 and the prolonged expression of restored dystrophin protein.29 The prolonged duration of dystrophin expression following PNA treatment compares favorably with other AO chemistries currently in clinical trials, with higher numbers of dystrophin-positive fibers detectable at the peak time point and more prolonged dystrophin expression than in 2'OMePS AO-treated mice,4 and comparable results to PMO-treated mice following intramuscular administration.10,30,31 The splice correcting efficacy of naked PNA AOs could not be improved by chosen peptide conjugation; in fact the tested peptides failed either to enhance intramuscular ((RXR)4, muscle-specific peptide) or systemic (Pip2b) PNA activity. The explanation for this is unclear, especially in the case of well-established arginine-rich peptides such as (RXR)4 which have been shown to enhance PMO delivery and exon skipping activity13 or in the case of Pip2b which has been shown to facilitate intramuscular PNA uptake,21 but not systemic delivery in the present study. It is possible that direct conjugation of such peptides might interfere with the activity of PNAs which contain a peptide backbone and could result in secondary structural changes which are either unfavorable for or are directly inhibitory of AO activity. Significantly, these data indicate that peptides which are effective in vivo in combination with PMO are not necessarily suitable for PNA AOs. Further studies are required to understand the optimal structure of peptide-PNA AO conjugates and to identify more compatible peptides for PNA AOs.

Despite the encouraging data reported previously8 and here in aged and young adult mdx mice with PNA20 AOs, very low and variable levels of dystrophin splice correction and protein restoration were found in peripheral muscle groups following intravenous systemic administration. Single intravenous doses of up to 100 mg/kg were studied, lower than those previously reported total cumulative systemic doses for 2'OMePS5 and PMO10 AOs, so it is difficult to draw firm conclusions about the comparable efficacies of alternative AO chemistries. Further study is required to fully explore the potential of PNA AO as an alternative chemistry for DMD and to compare the efficacies of different AO chemistries side by side. A number of factors critically influence the activity of splice correcting AOs.32 Among these factors, the binding energies of AO-target and AO–AO complexes are dependent on AO chemistry as well as on AO length. Indeed previous cellular and in vivo work has shown that AO length can significantly influence splice correcting efficacy23,24,25,33 and we therefore investigated whether the relatively poor in vivo activity of the PNA20 AO could have been due to a failure to optimize AO length. A screen of different length PNA AOs revealed that PNAs as short as 15-mers retained significant splice correcting functions. However, a significant increase in splice correction was found with longer PNAs, notably with a 25-mer PNA corresponding in length and sequence to the most efficacious PMO sequence targeting mouse DMD exon 23. It seems likely that the increased AO-target binding energy offered by PNA25 was the most significant factor explaining its enhanced potency. We therefore wished to study the effects of this more potent PNA AO in comparison with PNA20 AO following systemic delivery in mdx mice. Given the challenge of scale-up of longer PNA AOs, we evaluated relatively low doses of PNA25 compound and we were unable to replicate the experimental paradigm found to be most successful for PMO compounds that utilized 7 weekly intravenous injections at a 100 mg/kg dose.10 Nevertheless, evaluation of the PNA25 at a 3 weekly 15 mg/kg dose and direct comparison with PNA20 revealed that the longer PNA had enhanced systemic splice correcting properties, with dystrophin restoration in peripheral muscles to levels at least comparable with that seen for 2'OMePS AOs.5

PNA AOs therefore have potential as systemic splice correcting agents for DMD and related disorders where the modification of target gene splicing is likely to be of therapeutic efficacy. New synthetic methods to prepare longer, more active PNAs now exist as demonstrated in this report and it will now be important to scale-up this process at reasonable cost for detailed preclinical and clinical studies. Studies of the biodistribution, stability, and possible self-complementarity of longer PNAs will be of interest for future applications. It will now also be important to optimize the dose regimen for PNA AOs in order to evaluate the therapeutic potential of these agents in direct comparison with established PMO and 2'OMePS chemistries and dosing regimens. Further work should also be pursued to study methods for enhanced PNA delivery, including the exploitation of novel cell-targeting peptides that might facilitate more effective systemic PNA delivery without immune effects or compromising splice correcting efficacy.

Materials and Methods

Animals. Two-month-old and twelve-month-old mdx mice were used in the experiments (three mice in the test and control groups). The experiments were carried out in the Animal Unit, Department of Physiology, Anatomy and Genetics, University of Oxford (Oxford, UK) according to procedures authorized by the UK Home Office. Mice were killed by CO2 inhalation or cervical dislocation at desired time points, and muscles and other tissues were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen-cooled isopentane and stored at −80 °C.

PNA and PNA-peptide conjugates. Details of PNA and PNA-peptide conjugates are shown in Table 1. PNA and peptide-PNA conjugates were synthesized with high-performance liquid chromatography purification to >90% purity by Panagene (Daejeon, Korea) or in the Gait Laboratory (Cambridge, UK) as previously described.21 Different PNA AO lengths and positions with respect to boundary region of exon and intron 23 of the murine DMD gene were tested, as shown in Table 1.

RNA extraction and nested RT-PCR analysis. Total RNA was extracted from tested muscle tissues with Trizol (Invitrogen, Renfrew, UK) and 200 ng of RNA template was used for 20 µl RT-PCR with OneStep RT-PCR kit (Qiagen, West Sussex, UK). The primer sequences for the initial RT-PCR were Exon20Fo 5′-CAGAATTCTGCCAATTGCTGAG-3′ and Ex26Ro 5′-TTCTTCAGCTTGTGTCATCC-3′ for reverse transcription and amplification of mRNA from exons 20–26. RT-PCR was carried out as previously reported.8 The primer sequences for the second round were Ex20Fi 5′-CCCAGTCTACCACCCTATCAGAGC-3′ and Ex24Ri 5′-CAGCCATCCATTTCTGTAAGG-3. The products were examined by electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel.

Intramuscular and systemic injection of PNA and PNA-peptide conjugates. For intramuscular studies the TA muscle of each experimental mdx mouse was injected with a 40 µl dose of PNA and PNA-peptide conjugates in saline at a final concentration of 125 µg/ml. For systemic intravenous injections, various amounts of PNA or PNA-peptide conjugates in 80-µl saline buffer were injected into the tail vein of mdx mice at final doses of 15, 25, 50, or 100 mg/kg, respectively.

Immunohistochemistry. Sections of 8 µm were cut from at least two-thirds of the muscle length of TA, quadriceps, gastrocnemius, biceps, abdominal wall, and diaphragm muscles and heart muscle at 100 µm intervals. The sections were then examined for dystrophin expression with a polyclonal rabbit antibody 2166 against the dystrophin carboxyl-terminal region (the antibody was kindly provided by Kay Davies). The maximum number of dystrophin-positive fibers in one section was counted using the Zeiss AxioVision fluorescence microscope (Zeiss, Hertfordshire, UK) and the muscle fibers were defined as dystrophin-positive when more than two-thirds of the single fiber showed continuous staining. The intervening muscle sections were collected either for RT-PCR analysis and western blot or as serial sections for immunohistochemistry. Polyclonal antibodies were detected by goat-anti-rabbit immunoglobin G Alexa Fluro 594 (Molecular Probe, Renfrew, UK).

Protein extraction and western blotting. Protein extraction and western blotting were conducted as previously reported.8 Various amounts protein from normal C57BL6 mice as a positive control and corresponding amounts of protein from muscles of treated or untreated mdx mice were loaded onto sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels (4% stacking, 6% resolving). The membrane was then washed and blocked with 5% skimmed milk and probed overnight with DYS1 (monoclonal antibody against dystrophin R8 repeat, 1:200; NovoCastra, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK) for the detection of dytstrophin protein and α-actinin (monoclonal antibody, 1:5,000; Sigma, Dorset, UK) as a loading control. The bound primary antibody was detected by horseradish peroxidise-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobin G and the ECL western blotting analysis system (Amersham Pharmacia Biosciences, Buckinghamshire, UK). The intensity of the bands obtained from treated mdx muscles was measured by Image J software; the quantification is based on band intensity and area, and is compared with that from normal muscles of C57BL6 mice.

Serum creatinine kinase measurements and other biochemical tests. Serum and plasma were taken from the mouse jugular vein immediately after the killing with CO2 inhalation. Analysis of serum creatinine kinase, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, urea, and creatinine levels was performed by the clinical pathology laboratory (Mary Lyon Centre, Medical Research Council, Harwell, Oxfordshire, UK).

Statistical analysis. All data are reported as mean values ± SEM. Statistical differences between treatment groups and control groups were evaluated by SigmaStat (Systat Software, London, UK) and Student's t-test was applied.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALFigure S1. Duration of dystrophin expression following one single intramuscular MSPPNA conjugates administration in 6-month-old mdx mice. (a) Immunohistochemistry for dystrophin induction in TA muscles of 6-month old mdx mice 2,4,8,16 weeks after one single intramuscular injection of 5 μg MSP-PNA (scale bar=200 μm). (b) Quantitative evaluation of total dystrophin-positive fibres in TA muscles at different time points after a single intramuscular injection of MSP-PNA conjugates. All groups except 16 weeks post-injection showed significant improvement in comparison with age-matched mdx mice (* P<0.05).Figure S2. Measurement of serum levels of creatine kinase (CK), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) liver enzymes in treated mdx mice. (a) Measurement of serum CK levels as an index of ongoing muscle membrane instability in treated mdx mice compared with normal and mdx control mice. Data shows no difference in the serum CK levels in mdx mice treated with PNA AOs compared with untreated age-matched mdx controls. (b) The level of AST and ALT in the blood samples from treated mdx mice with single 25, 50 100 mg/kg PNA AOs showed no difference when compared with untreated mdx mice.Figure S3. Restoration of muscle dystrophin expression following single 25 mg/kg intravenous injections of the Pip2b-PNA20 and R-PNA20 AO conjugates in adult mdx mice. (a) Immunostaining of muscle tissue cross sections to detect dystrophin protein expression and localisation in Pip2b-PNA treated mdx mice (top panel) and R-PNA treated mdx mice (lower panel), showing low levels of dystrophin expression in the treated mice. Muscle tissues analysed were from tibialis anterior (TA), quadriceps, gastrocnemius, biceps, diaphragm, heart and abdominal wall muscles (scale bar = 200 μm). (b) Quantitative evaluation of total dystrophin-positive fibres in all tested muscles 2 weeks after single intravenous injection of Pip2b-PNA, R-PNA conjugates.Figure S4. Evaluation of dystrophin restoration after intramuscular injection of 5 µg PNA25 and Pip2b, R-PNA25. (a) Immunohistochemistry for dystrophin induction in TA muscles of 2-month old mdx mice 2 weeks after single intramuscular injections (scale bar = 200 μm). (b) Quantitative evaluation of total dystrophin-positive fibres in TA muscles after single intramuscular injection of PNA25, Pip2b- and R-PNA25 conjugates. Naked PNA25 showed significant improvement compared with Pip2b- and R-PNA25 (* P<0.05). (c) RT-PCR to detect exon skipping efficiency at the RNA level demonstrated up to 50% exon 23 skipping in the TA muscle treated with PNA25 AO and about 10% exon skipping in Pip2b- and R-PNA conjugates treated mdx mice. This is shown by shorter exon-skipped bands (indicated by Δexon23– for exon 23 skipping). Truncated transcripts deleted for both exons 22 and 23 were also seen as indicated by Δexon22–23.Figure S5. Restoration of muscle dystrophin expression following single 25 mg/kg intravenous injections of the Pip2b-PNA25 and R-PNA25 AO conjugates in adult mdx mice. (a) Immunostaining of muscle tissue cross sections to detect dystrophin protein expression and localisation in Pip2b-PNA treated mdx mice (top panel) and R-PNA treated mdx mice (lower panel), showing low levels of dystrophin expression in the treated muscles. Muscle tissues analysed were from tibialis anterior (TA), quadriceps, gastrocnemius, biceps, diaphragm, heart and abdominal wall muscles (scale bar = 200 μm). (b) Quantitative evaluation of total dystrophin-positive fibres in all tested muscles 2 weeks after single intravenous injection of Pip2b-PNA25, R-PNA25 conjugates.

Supplementary Material

Duration of dystrophin expression following one single intramuscular MSPPNA conjugates administration in 6-month-old mdx mice. (a) Immunohistochemistry for dystrophin induction in TA muscles of 6-month old mdx mice 2,4,8,16 weeks after one single intramuscular injection of 5 μg MSP-PNA (scale bar=200 μm). (b) Quantitative evaluation of total dystrophin-positive fibres in TA muscles at different time points after a single intramuscular injection of MSP-PNA conjugates. All groups except 16 weeks post-injection showed significant improvement in comparison with age-matched mdx mice (* P<0.05).

Measurement of serum levels of creatine kinase (CK), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) liver enzymes in treated mdx mice. (a) Measurement of serum CK levels as an index of ongoing muscle membrane instability in treated mdx mice compared with normal and mdx control mice. Data shows no difference in the serum CK levels in mdx mice treated with PNA AOs compared with untreated age-matched mdx controls. (b) The level of AST and ALT in the blood samples from treated mdx mice with single 25, 50 100 mg/kg PNA AOs showed no difference when compared with untreated mdx mice.

Restoration of muscle dystrophin expression following single 25 mg/kg intravenous injections of the Pip2b-PNA20 and R-PNA20 AO conjugates in adult mdx mice. (a) Immunostaining of muscle tissue cross sections to detect dystrophin protein expression and localisation in Pip2b-PNA treated mdx mice (top panel) and R-PNA treated mdx mice (lower panel), showing low levels of dystrophin expression in the treated mice. Muscle tissues analysed were from tibialis anterior (TA), quadriceps, gastrocnemius, biceps, diaphragm, heart and abdominal wall muscles (scale bar = 200 μm). (b) Quantitative evaluation of total dystrophin-positive fibres in all tested muscles 2 weeks after single intravenous injection of Pip2b-PNA, R-PNA conjugates.

Evaluation of dystrophin restoration after intramuscular injection of 5 µg PNA25 and Pip2b, R-PNA25. (a) Immunohistochemistry for dystrophin induction in TA muscles of 2-month old mdx mice 2 weeks after single intramuscular injections (scale bar = 200 μm). (b) Quantitative evaluation of total dystrophin-positive fibres in TA muscles after single intramuscular injection of PNA25, Pip2b- and R-PNA25 conjugates. Naked PNA25 showed significant improvement compared with Pip2b- and R-PNA25 (* P<0.05). (c) RT-PCR to detect exon skipping efficiency at the RNA level demonstrated up to 50% exon 23 skipping in the TA muscle treated with PNA25 AO and about 10% exon skipping in Pip2b- and R-PNA conjugates treated mdx mice. This is shown by shorter exon-skipped bands (indicated by Δexon23– for exon 23 skipping). Truncated transcripts deleted for both exons 22 and 23 were also seen as indicated by Δexon22–23.

Restoration of muscle dystrophin expression following single 25 mg/kg intravenous injections of the Pip2b-PNA25 and R-PNA25 AO conjugates in adult mdx mice. (a) Immunostaining of muscle tissue cross sections to detect dystrophin protein expression and localisation in Pip2b-PNA treated mdx mice (top panel) and R-PNA treated mdx mice (lower panel), showing low levels of dystrophin expression in the treated muscles. Muscle tissues analysed were from tibialis anterior (TA), quadriceps, gastrocnemius, biceps, diaphragm, heart and abdominal wall muscles (scale bar = 200 μm). (b) Quantitative evaluation of total dystrophin-positive fibres in all tested muscles 2 weeks after single intravenous injection of Pip2b-PNA25, R-PNA25 conjugates.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from Action Duchenne UK to M.J.A.W. The authors acknowledge the UK MDEX Consortium for helpful discussions; Kay Davies (Department of Physiology, Anatomy and Genetics, University of Oxford) for providing access to facilities including the mdx mouse colony; Dr Tertius Hough (Clinical Pathology Laboratory, Mary Lyon Centre, MRC, Harwell, UK) for assistance with the clinical biochemistry assays; and Christine Simpson (Department of Physiology, Anatomy and Genetics, University of Oxford) for assistance with histology. The authors declared no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Dominski Z., and , Kole R. Restoration of correct splicing in thalassemic pre-mRNA by antisense oligonucleotides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8673–8677. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aartsma-Rus A, Janson AA, Kaman WE, Bremmer-Bout M, van Ommen GJ, den Dunnen JT, et al. Antisense-induced multiexon skipping for Duchenne muscular dystrophy makes more sense. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:83–92. doi: 10.1086/381039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aartsma-Rus A, Kaman WE, Weij R, den Dunnen JT, van Ommen GJ., and , van Deutekom JC. Exploring the frontiers of therapeutic exon skipping for Duchenne muscular dystrophy by double targeting within one or multiple exons. Mol Ther. 2006;14:401–407. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu QL, Mann CJ, Lou F, Bou-Gharios G, Morris GE, Xue SA, et al. Functional amounts of dystrophin produced by skipping the mutated exon in the mdx dystrophic mouse. Nat Med. 2003;9:1009–1014. doi: 10.1038/nm897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu QL, Rabinowitz A, Chen YC, Yokota T, Yin H, Alter J, et al. Systemic delivery of antisense oligoribonucleotide restores dystrophin expression in body-wide skeletal muscles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:198–203. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406700102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann CJ, Honeyman K, Cheng AJ, Ly T, Lloyd F, Fletcher S, et al. Antisense-induced exon skipping and synthesis of dystrophin in the mdx mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:42–47. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011408598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilton SD, Fall AM, Harding PL, McClorey G, Coleman C., and , Fletcher S. Antisense oligonucleotide-induced exon skipping across the human dystrophin gene transcript. Mol Ther. 2007;15:1288–1296. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin H, Lu Q., and , Wood M. Effective exon skipping and restoration of dystrophin expression by peptide nucleic acid antisense oligonucleotides in mdx mice. Mol Ther. 2008;16:38–45. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Deutekom JC, Janson AA, Ginjaar IB, Frankhuizen WS, Aartsma-Rus A, Bremmer-Bout M, et al. Local dystrophin restoration with antisense oligonucleotide PRO051. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2677–2686. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alter J, Lou F, Rabinowitz A, Yin H, Rosenfeld J, Wilton SD, et al. Systemic delivery of morpholino oligonucleotide restores dystrophin expression bodywide and improves dystrophic pathology. Nat Med. 2006;12:175–177. doi: 10.1038/nm1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jearawiriyapaisarn N, Moulton HM, Buckley B, Roberts J, Sazani P, Fucharoen S, et al. Sustained dystrophin expression induced by peptide-conjugated morpholino oligomers in the muscles of mdx mice. Mol Ther. 2008;16:1624–1629. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu B, Li Y, Morcos PA, Doran TJ, Lu P., and , Lu QL. Octa-guanidine morpholino restores dystrophin expression in cardiac and skeletal muscles and ameliorates pathology in dystrophic mdx mice. Mol Ther. 2009;17:864–871. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin H, Moulton HM, Seow Y, Boyd C, Boutilier J, Iverson P, et al. Cell-penetrating peptide-conjugated antisense oligonucleotides restore systemic muscle and cardiac dystrophin expression and function. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:3909–3918. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aartsma-Rus A, Janson AA, Kaman WE, Bremmer-Bout M, den Dunnen JT, Baas F, et al. Therapeutic antisense-induced exon skipping in cultured muscle cells from six different DMD patients. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:907–914. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen HJ, Bentin T., and , Nielsen PE. Antisense properties of peptide nucleic acid. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1489:159–166. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(99)00145-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabani MM., and , Gait MJ. miR-122 targeting with LNA/2'-O-methyl oligonucleotide mixmers, peptide nucleic acids (PNA), and PNA-peptide conjugates. RNA. 2008;14:336–346. doi: 10.1261/rna.844108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alotte C, Martin A, Caldarelli SA, Di Giorgio A, Condom R, Zoulim F, et al. Short peptide nucleic acids (PNA) inhibit hepatitis C virus internal ribosome entry site (IRES) dependent translation in vitro. Antiviral Res. 2008;80:280–287. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JJ, Ivanova GD, Verbeure B, Williams D, Arzumanov AA, Abes S, et al. Cell-penetrating peptide conjugates of peptide nucleic acids (PNA) as inhibitors of HIV-1 Tat-dependent trans-activation in cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:6837–6849. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann CJ, Honeyman K, McClorey G, Fletcher S., and , Wilton SD. Improved antisense oligonucleotide induced exon skipping in the mdx mouse model of muscular dystrophy. J Gene Med. 2002;4:644–654. doi: 10.1002/jgm.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samoylova TI., and , Smith BF. Elucidation of muscle-binding peptides by phage display screening. Muscle Nerve. 1999;22:460–466. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4598(199904)22:4<460::aid-mus6>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova GD, Arzumanov A, Abes R, Yin H, Wood MJ, Lebleu B, et al. Improved cell-penetrating peptide-PNA conjugates for splicing redirection in HeLa cells and exon skipping in mdx mouse muscle. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:6418–6428. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova GD, Fabani MM, Arzumanov AA, Abes R, Yin H, Lebleu B, et al. PNA-peptide conjugates as intracellular gene control agents. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser (Oxf) 2008. pp. 31–32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Harding PL, Fall AM, Honeyman K, Fletcher S., and , Wilton SD. The influence of antisense oligonucleotide length on dystrophin exon skipping. Mol Ther. 2007;15:157–166. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popplewell LJ, Trollet C, Dickson G., and , Graham IR. Design of phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomers (PMOs) for the induction of exon skipping of the human DMD gene. Mol Ther. 2009;17:554–561. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arechavala-Gomeza V, Graham IR, Popplewell LJ, Adams AM, Aartsma-Rus A, Kinali M, et al. Comparative analysis of antisense oligonucleotide sequences for targeted skipping of exon 51 during dystrophin pre-mRNA splicing in human muscle. Hum Gene Ther. 2007;18:798–810. doi: 10.1089/hum.2006.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sazani P, Gemignani F, Kang SH, Maier MA, Manoharan M, Persmark M, et al. Systemically delivered antisense oligomers upregulate gene expression in mouse tissues. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:1228–1233. doi: 10.1038/nbt759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitiello L, Bassi N, Campagnolo P, Zaccariotto E, Occhi G, Malerba A, et al. In vivo delivery of naked antisense oligos in aged mdx mice: analysis of dystrophin restoration in skeletal and cardiac muscle. Neuromuscul Disord. 2008;18:597–605. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2008.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gambari R. Peptide-nucleic acids (PNAs): a tool for the development of gene expression modifiers. Curr Pharm Des. 2001;7:1839–1862. doi: 10.2174/1381612013397087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad A, Brinson M, Hodges BL, Chamberlain JS., and , Amalfitano A. Mdx mice inducibly expressing dystrophin provide insights into the potential of gene therapy for duchenne muscular dystrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:2507–2515. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.17.2507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher S, Honeyman K, Fall AM, Harding PL, Johnsen RD., and , Wilton SD. Dystrophin expression in the mdx mouse after localised and systemic administration of a morpholino antisense oligonucleotide. J Gene Med. 2006;8:207–216. doi: 10.1002/jgm.838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JJ, Jones S, Fabani MM, Ivanova G, Arzumanov AA., and , Gait MJ. RNA targeting with peptide conjugates of oligonucleotides, siRNA and PNA. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2007;38:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aartsma-Rus A, van Vliet L, Hirschi M, Janson AA, Heemskerk H, de Winter CL, et al. Guidelines for antisense oligonucleotide design and insight into splice-modulating mechanisms. Mol Ther. 2009;17:548–553. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heemskerk HA, de Winter CL, de Kimpe SJ, van Kuik-Romeijn P, Heuvelmans N, Platenburg GJ, et al. In vivo comparison of 2'-O-methyl phosphorothioate and morpholino antisense oligonucleotides for Duchenne muscular dystrophy exon skipping. J Gene Med. 2009;11:257–266. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Duration of dystrophin expression following one single intramuscular MSPPNA conjugates administration in 6-month-old mdx mice. (a) Immunohistochemistry for dystrophin induction in TA muscles of 6-month old mdx mice 2,4,8,16 weeks after one single intramuscular injection of 5 μg MSP-PNA (scale bar=200 μm). (b) Quantitative evaluation of total dystrophin-positive fibres in TA muscles at different time points after a single intramuscular injection of MSP-PNA conjugates. All groups except 16 weeks post-injection showed significant improvement in comparison with age-matched mdx mice (* P<0.05).

Measurement of serum levels of creatine kinase (CK), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) liver enzymes in treated mdx mice. (a) Measurement of serum CK levels as an index of ongoing muscle membrane instability in treated mdx mice compared with normal and mdx control mice. Data shows no difference in the serum CK levels in mdx mice treated with PNA AOs compared with untreated age-matched mdx controls. (b) The level of AST and ALT in the blood samples from treated mdx mice with single 25, 50 100 mg/kg PNA AOs showed no difference when compared with untreated mdx mice.

Restoration of muscle dystrophin expression following single 25 mg/kg intravenous injections of the Pip2b-PNA20 and R-PNA20 AO conjugates in adult mdx mice. (a) Immunostaining of muscle tissue cross sections to detect dystrophin protein expression and localisation in Pip2b-PNA treated mdx mice (top panel) and R-PNA treated mdx mice (lower panel), showing low levels of dystrophin expression in the treated mice. Muscle tissues analysed were from tibialis anterior (TA), quadriceps, gastrocnemius, biceps, diaphragm, heart and abdominal wall muscles (scale bar = 200 μm). (b) Quantitative evaluation of total dystrophin-positive fibres in all tested muscles 2 weeks after single intravenous injection of Pip2b-PNA, R-PNA conjugates.

Evaluation of dystrophin restoration after intramuscular injection of 5 µg PNA25 and Pip2b, R-PNA25. (a) Immunohistochemistry for dystrophin induction in TA muscles of 2-month old mdx mice 2 weeks after single intramuscular injections (scale bar = 200 μm). (b) Quantitative evaluation of total dystrophin-positive fibres in TA muscles after single intramuscular injection of PNA25, Pip2b- and R-PNA25 conjugates. Naked PNA25 showed significant improvement compared with Pip2b- and R-PNA25 (* P<0.05). (c) RT-PCR to detect exon skipping efficiency at the RNA level demonstrated up to 50% exon 23 skipping in the TA muscle treated with PNA25 AO and about 10% exon skipping in Pip2b- and R-PNA conjugates treated mdx mice. This is shown by shorter exon-skipped bands (indicated by Δexon23– for exon 23 skipping). Truncated transcripts deleted for both exons 22 and 23 were also seen as indicated by Δexon22–23.

Restoration of muscle dystrophin expression following single 25 mg/kg intravenous injections of the Pip2b-PNA25 and R-PNA25 AO conjugates in adult mdx mice. (a) Immunostaining of muscle tissue cross sections to detect dystrophin protein expression and localisation in Pip2b-PNA treated mdx mice (top panel) and R-PNA treated mdx mice (lower panel), showing low levels of dystrophin expression in the treated muscles. Muscle tissues analysed were from tibialis anterior (TA), quadriceps, gastrocnemius, biceps, diaphragm, heart and abdominal wall muscles (scale bar = 200 μm). (b) Quantitative evaluation of total dystrophin-positive fibres in all tested muscles 2 weeks after single intravenous injection of Pip2b-PNA25, R-PNA25 conjugates.