Abstract

This article describes the process of development of the Family Management Style Framework. The FMSF is a conceptual representation of family response to a child's condition that takes into account the views of individual family members to conceptualize overall patterns of family response. The FMSF provides a more complete understanding of family life in the context of a child's chronic condition and directs researchers’ and clinicians’ efforts to assess family response, especially with regard to how condition management is incorporated into everyday family life. Framework development has included conceptual analyses of the literature, empirical studies of family management of childhood illness, and methodological work directed to treating the family as a unit of study and analysis. This article highlights how the interplay of conceptual, empirical, and methodological work advances knowledge development and presents lessons learned over the course of developing the FMSF.

Keywords: family research, family management, childhood chronic illness, family research methods, Family Management Style Framework

The Family Management Style Framework (FMSF; Knafl & Deatrick, 1990, 2003) is a conceptual representation of family response to a child's condition that incorporates the views of individual family members to conceptualize overall patterns of family response. The development of the FMSF has entailed 20 years of conceptual, empirical, and methodological work. Following a brief overview of the FMSF, this article describes the contribution of these three types of work to framework development. Although focusing on a particular framework, our intent is to convey how the interplay of concepts, research, and methods advances knowledge development.

Overview of FMSF

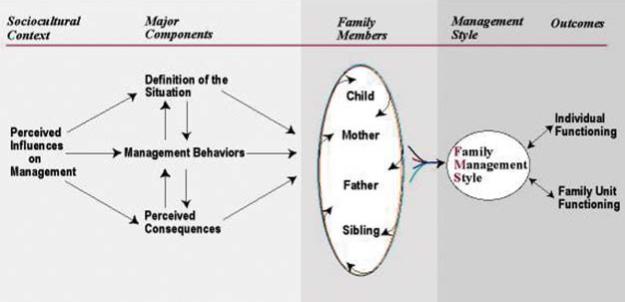

As depicted in Figure 1, the FMSF is a conceptualization of key elements of family members’ efforts to manage a child's chronic condition and incorporate condition management into everyday family life. As such, its focus is more specific than other frameworks that conceptualize overall family functioning (e.g., Symbolic Interaction) or selected aspects of family functioning such as communication or decision making.

Figure 1.

Family Management Style Framework (Knafl & Deatrick, 2003)

The FMSF conceptualizes the interplay of how individual family members define key aspects of having a child with a chronic condition (Definition of the Situation), the behaviors they use to manage the condition (Management Behaviors), and their perceptions of the consequences of the condition for family life (Perceived Consequences). The resulting Family Management Style (FMS) is the pattern of family members’ responses across these three components. The FMSF also includes family members’ perception of factors that influence family life and their response to the child's condition (Sociocultural Context). Different patterns reveal the extent to which family members have shared or discrepant perspectives on these three key elements of family life in the context of a child's condition. Knowing the FMS provides insights into family strengths with regard to condition management as well as areas of difficulty. FMS is conceptualized as mediating individual and family system outcomes.

The intent of the FMSF is to provide a useful guide for uncovering a more complete understanding of family life in the context of a child's chronic condition. It is meant to direct researchers’ and clinicians’ efforts to assess family response to a child's chronic condition, especially with regard to how condition management is incorporated into everyday family life. Typical of a conceptual framework, the FMSF focuses the researcher's or clinician's observations without predicting what they will see. In other words, the FMSF does not specify how the family defines or manages the condition. Rather, as we describe later, it identifies important aspects of the family's definition of the situation, management behaviors, and perceived consequences that shape their management efforts.

Development of the FMSF

Framework development began with a simple question: How do families respond to a child's chronic illness? Nonetheless, despite the apparent simplicity of the question, we are still working on the answer 20 years later. Over that 20-year time span, we have completed conceptual analyses of the literature, empirical studies of family management of childhood illness, and methodological work directed to treating the family as a unit of study and analysis. Conceptual work has focused on knowledge synthesis. We have completed concept analyses and integrative reviews of family management style and of the specific management style of normalization (Deatrick & Knafl, 1990; Deatrick, Knafl, & Murphy-Moore, 1999; Knafl & Deatrick, 1986, 1990, 2003). Empirical studies have focused on family management of chronic illness, genetic information, and cancer survivorship. We also have completed a study aimed at developing a standardized measure of family management. During the course of our empirical studies, we have found it necessary to adapt existing methods to make them more “family friendly”; occasionally, we have created new analytic approaches directed to maintaining our family focus.

Development of the FMSF has been, and continues to be, a rewarding adventure in knowledge development. The Appendix provides a more comprehensive, chronological listing of the grants that have supported framework development as well as the publications reporting our conceptual, empirical, and methodological work. Although the three authors have collaborated on much of the work of developing the framework, the coinvestigators and coauthors in the appendix citations also have made important contributions to framework development. In the next sections, we describe the interplay of conceptual, empirical, and methodological work that has characterized the development of the FMSF.

Initial Conceptual, Empirical, and Methodological Work

Our initial work was conceptual and began with the analysis of the concept of normalization (Knafl & Deatrick, 1986). In completing this first analysis, we realized that normalization was one of several patterns of family response to childhood illness that researchers had identified. Based on this recognition and in search of a better understanding about family management styles, we decided to complete a second concept analysis, focusing more broadly on that concept. We soon discovered that although we had begun using the phrase “family management style” to refer to distinct patterns of family response to childhood chronic illness, it was not a phrase that appeared in the literature. Thus, we focused our review on research that identified different patterns of family response to childhood illness. The analysis identified and defined three major attributes of family management style (Definition of the Situation, Management Behaviors, and Sociocultural Context). Based on this analysis, we developed our initial model of the FMSF, which depicted how the individual family members’ perspectives formed the family's management style (Knafl & Deatrick, 1990).

This beginning conceptual work set the stage for moving to an empirical phase of framework development. The initial formulation of the FMSF provided the conceptual underpinnings for our first major study titled “How Families Define and Manage Childhood Chronic Illness” funded by the National Institutes of Health (Knafl, Breitmayer, Gallo, & Zoeller, 1994, 1996). Our goals in that study were to specify further the three major components of the FMSF and identify distinct patterns (FMSs) of family management. We gathered data from mothers, fathers, children with a chronic condition, and their healthy siblings in 63 families (about 200 family members) in which there was a school-age child with a non-life-threatening chronic condition. It was a mixed method design, though predominantly qualitative study. We elicited detailed accounts from individual family members’ regarding their perspectives on family life in the context of a child's chronic condition. The FMSF shaped the specific aims of the study as well as the interview guides we developed. Family members also completed standardized measures of individual and family functioning.

By the completion of this 5-year study, we had achieved our aims of further developing the FMSF and identifying distinct FMSs (Knafl et al., 1996). We had identified underlying dimensions for each component of the FMSF. For example, we identified three underlying dimensions of the Definition of the Situation component—illness view, child identity, and management mindset. The underlying dimensions reflected key aspects of each component and contributed to a more complete understanding of what family members identified as the important aspects of incorporating condition management into everyday family life. We also identified five distinct FMSs (Thriving, Accommodating, Enduring, Struggling, and Floundering), each of which reflected a different manifestation of the various management dimensions of the framework.

Our initial empirical work also contributed to the development of methods for maintaining the family as the unit of analysis in qualitative research (Knafl & Ayres, 1996; Knafl, Gallo, Breitmayer, Zoeller, & Ayres, 1993). Some of the challenges we faced as family researchers prompted us to adapt existing analytic techniques to support our aim of identifying family patterns of response. The proposal we submitted to the National Institutes of Health had focused more on the systematic analysis of qualitative data than on the preservation of the family as the unit of analysis. However, during the course of analysis we realized that our coding and matrix display techniques were putting us at risk for losing our family focus. Recognizing this, we developed a matrix display format that facilitated comparison across individual family members as well as across different families. We also developed structured family case summaries that made it possible to situate our review of coded data in the context of a summary of all the data we had collected from a family (Knafl & Ayres, 1996). These techniques were invaluable in helping us identify the varying thematic patterns that characterized the five FMSs. Other methodological efforts were directed to developing techniques to link our qualitative and quantitative data (Breitmayer, Ayres, & Knafl, 1993) and applying a narrative analysis approach to sections of our qualitative interviews (Knafl, Ayres, Gallo, Zoeller, & Breitmayer, 1995).

What we learned in that first major study informed our subsequent research. The specification of the three components of the FMSF has been especially useful in developing interview guides for subsequent studies. We continue to use the same approach to constructing matrices of data from multiple family members, and we analyze those matrices in conjunction with case summaries that preserve the family focus of our research. Having developed these methods has streamlined our subsequent analyses, and the fact that we have reported these techniques in refereed journals has provided us with evidence of the credibility of our approaches that we have cited in subsequent proposal submissions.

Subsequent Conceptual, Empirical, and Methodological Work

Of course, others were doing important family research at the same time we were, and we recognized the importance of situating our research in the larger body of knowledge relevant to family management of childhood chronic conditions. Having completed our first major study, once again we decided to focus on conceptual work and to use the literature to assess the relevance and further refine the components and dimensions of the FMSF. We reviewed 55 published studies and found substantial support for the salience of the components and dimensions of the framework (Knafl & Deatrick, 2003). However, we also concluded that we needed to undertake refinement and modification of the framework. Specifically, we redefined two of the three components and added more specificity to our definitions of the eight dimensions (Table 1) that comprised the three components. It has been especially challenging for us to develop the Management Behavior component of the FMSF so that it is applicable to a broad array of chronic conditions. Our research and the literature supported the importance of understanding the underlying goals and values that form the basis for parents’ management behaviors and the extent to which the family has developed a stable routine for incorporating condition management into everyday family life. Parenting Philosophy and Management Approach, the two dimensions of the Management Behaviors component of the FMSF, direct the researcher's and clinician's attention beyond adherence to specific aspects of the treatment regimen to consideration of the implications of the regimen for family life and parenting goals. This conceptualization of management behaviors contributes to the broad applicability of the FMSF.

Table 1.

Components and Dimensions of the Family Management Style Framework (Knafl & Deatrick, 2003)

| Conceptual Component | Dimensions of Component |

|---|---|

| Definition of the situation |

Child Identity: Parents’ views of the child and the extent to which those views focus on illness or normalcy and capabilities or vulnerabilities. Illness View: Parents’ beliefs about the cause, seriousness, predictability, and course of the illness. Management Mindset: Parents’ views of the ease or difficulty of carrying out the treatment regimen and their ability to manage effectively Parental Mutuality: Caregivers’ beliefs about the extent to which they have shared or discrepant views of the child, the illness, their parenting philosophy, and their approach to illness management. |

| Management behaviors |

Parenting Philosophy: Parents’ goals, priorities, and values that guide the overall approach and specific strategies for illness management. Management Approach: Parents’ assessment of the extent to which they have developed a routine, and related strategies, for managing the illness and incorporating it into family life. |

| Perceived consequences |

Family Focus: Parents’ assessment of the balance between illness management and other aspects of family life. Future Expectation: Parents’ assessment of the implications of the illness for their child's and family's future. |

In addition, we completed a second analysis of the concept of normalization (Deatrick, Knafl, & Murphy-Moore, 1999). Normalization was an overarching theme in two of the FMSs we had identified in our research (Knafl et al., 1996), and we wanted to link our findings on the concept to that of others. Our review of 33 articles representing 14 studies resulted in further refinement of the attributes of normalization identified in our original review and provided insights into varied manifestations of normalization across illness and family contexts (Knafl & Deatrick, 1986).

The conceptual work of further refining the eight underlying dimensions of the FMSF dimensions set the stage for our next empirical study, the development of a standardized measure of family management. Through our prior concept analyses, integrative reviews, and research, we had identified key aspects of the family's experience of managing a child's chronic condition. On the basis of this prior work, we were confident that the eight dimensions we had identified shaped the families’ experiences of having a child with a chronic condition. Moreover, we recognized distinct advantages of having a standardized measure of family management. Such a measure would contribute to the more efficient clinical assessment of family management and to further research testing the relationship between FMS and various child and family outcomes.

We recently have completed the development of the Family Management Measure (FaMM). Testing of the psychometric properties of the FaMM was based on data from 579 parents of children with a chronic condition, and there was strong support for the reliability and validity for all the six scales of the FaMM (Child, Concern, Difficulty, Effort, Manageability, and Mutuality). Detailed information on the development, psychometric properties, and use of the FaMM is available at the following Web site: http://nursing.unc.edu/research/fmm.

Reaching Clinical Audiences and Mentoring Students

In addition to our conceptual, empirical, and methodological efforts, we have published in clinical journals to inform practice (Deatrick et al., 2006; Knafl & Deatrick, 2002; Knafl, Deatrick, & Kirby, 2001; Ogle, 2006). These articles address using the FMSF to guide assessment of family management and provide suggestions and examples for interventions based on the outcome of the assessment. They also emphasize the usefulness of our research and the FMSF for identifying family strengths and difficulties related to condition management.

Most recently, Agatha Gallo has taken the lead in reaching clinicians who work with families in which a child has a genetic condition (Gallo, Hadley, Angst, Knafl, & Smith, 2008). Drawing on the results of her study titled “Parents’ Interpretation and Use of Genetic Information,” she and other members of her research team have translated parents’ accounts of their needs and dilemmas related to genetic information into guidelines for supporting parents in their efforts to convey information about a genetic condition to the child with the condition, siblings, and extended family members.

Over the years, our conceptual, empirical, and methodological work has provided many opportunities for student involvement. Both undergraduate and graduate students have worked as research assistants on our projects over the years, some for the course of an entire project and some for more limited periods of time. There has never been a shortage of data, and we have benefited from students who have asked new questions of our data or taken a more detailed look at selected aspects. In the appendix, we have underlined the names of our student collaborators.

In addition, the students and other colleagues who have worked with us have sometimes taken the initiative to lead us in new directions. For example, Lioness Ayres advised us to use narrative analysis when we were struggling with how to analyze parents’ accounts of the diagnostic experience (Knafl et al., 1995); Carrol Smith introduced us to performance text as a particularly compelling way to communicate with clinical audiences (Smith & Gallo, 2007). Our goal in working with students always has been to provide them with a guided, meaningful research experience. We recognize, as well, that they have made substantial contributions to our work over the years.

Plans for the Future

We are completing several analyses of data from the FaMM study and are planning for a number of possible future projects as well. Currently, we are working on a cluster analysis based on the six FaMM scales. This analysis will make it possible to compare the initial, qualitatively derived FMSs to the quantitatively derived clusters. The FaMM study included a considerably larger and more diverse sample than in our original study of family management, and we anticipate identifying new patterns of family management. In addition, because we used measures of family and child functioning to validate the FaMM, we are in the process of analyzing the extent to which the FaMM scales mediate the impact of family functioning on child outcomes. Although the FMSF conceptualizes FMS as a mediating variable, we have not been able to test for a mediating effect until now.

Completion of the FaMM has raised some interesting conceptual questions regarding the FMSF. Items for the FaMM were based on the eight qualitative dimensions of the FMSF. Nonetheless, the analysis of data on which the FaMM was based identified six scales. For three scales (Child Identity, Effort, and Parental Mutuality) there is a close fit between one of the dimensions of the FMSF and the resulting scale. However, the other three scales (Concern, Difficulty, and Manageability) include items that cut across all three components of the FMSF, possibly indicating that the scales have synthesized both defining and management themes and thus have done a better job than we did in our qualitative study of capturing the interplay of the three components of the framework. In any case, our intent is to complete additional conceptual work directed to further refinement of the FMSF.

The FaMM analysis presented us with some interesting analytic challenges. We recruited families in which partnered parents participated as well as single-parent families and had a subset of items for the Mutuality theme that were completed only by partnered parents. Thus, we had independence issues for families in which partnered parents participated and missing data issues for single-parent families. During the course of data analysis, we came to realize that although certain aspects of the study design such as eliciting data from partnered parents and including different family structures in our sample were notable strengths, they posed significant analytic challenges. Future publications will discuss how we addressed some of the methodological challenges we faced in developing a family measure.

In addition, Janet Deatrick, Wendy Hobbie, and a group of collaborators at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia are now collaborating to explore the concept of family management within the survivorship population. Most specifically, their research focuses on caregiving within a family context for adolescent and young adult survivors of brain tumors. Translation of this research into practice while working closely with the survivorship population is a priority for these investigators.

Lessons Learned

Our work began with a question, How do families respond to a child's chronic illness? Over the past 20 years, our efforts have been directed toward developing a conceptual framework that provides direction for understanding family response to childhood chronic conditions. The FMSF identifies key aspects of the experiences of a broad array of families. Conceptual frameworks are important; they provide a guide for both clinicians and researchers that can direct observation and action.

We have learned a good deal over the years about building a program of research, the most important lesson being how much we can learn from families and the importance of grounding our conceptualizations in their experiences. Families have a lot to teach us, and they are eager to have us learn. They have been willing participants in our research over the years, and the power of their accounts has been an enduring source of motivation for our research teams. At the same time, we recognize the importance of going beyond what families tell us to “find the findings” in their accounts (Sandelowski, 2002). For us “finding the findings” has been the search for the underlying themes and patterns in the data.

In particular, families have a great deal to teach us about the role of health care providers, who often are major players in their accounts of family life in the context of a child's chronic condition. Their accounts provide useful insights into the nature of effective and ineffective interactions and interventions (Knafl, Breitmayer, Gallo, & Zoeller, 1992). Families also can provide useful insights into how best to conduct family research. For example, in developing the FaMM we carried out cognitive interviews with parents as part of establishing the content validity of our items. Parental input was especially helpful in identifying items where the wording was unacceptable or confusing (Knafl et al., 2007).

We also have learned the importance of sustaining a core team. The three authors have worked together for many years. We have shared as well as distinct interests and skills, and this continues to be a strength of the team. At the same time, we know there are gaps in our areas of expertise. For example, the instrument development study was a methodological stretch for us, and we benefited from the methodological and statistical expertise of coinvestigators and colleagues who both enhanced the quality of our work and contributed to our continuing growth as scholars. We have experienced firsthand the importance and value addition of a diverse research team.

In addition, we have come to appreciate the virtues of being methodological pragmatists. We have not been shy about adapting and developing methods when we felt existing ones were inadequate. In part, all our studies have been methods projects and we think this is a useful mindset for advancing family research.

We believe as well that systematic efforts to continually situate one's work in the field are critical. In our eagerness to build our own programs of research, we must take care to acknowledge and explicitly build on the work of others. Alternating between conceptual work that focused on knowledge synthesis and empirical studies that built on that conceptual synthesis has contributed to the development of the FMSF. We have learned the importance of taking stock before forging ahead with the next study.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Blair G. Darney for editorial assistance with this article.

Biography

Kathleen Knafl, PhD, FAAN, is the Associate Dean for Research and Frances Hill Fox Distinguished Professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Her research focuses on family management of childhood chronic illness. In collaboration with her colleagues Janet Deatrick, RN, PhD, FAAN, and Agatha Gallo, RN, PhD, FAAN, she developed the Family Management Style Framework and completed a series of studies describing distinct patterns of family response to the challenges presented by a child's chronic illness that have been funded by the National Institutes of Health. She is widely published and is recognized as an expert in family and qualitative research. She serves as a consultant to the National Institutes of Health and to universities and researchers. She is on the editorial boards of Research in Nursing and Health, Nursing Outlook, and the Journal of Family Nursing. Recent publications include “Family Management Style and the Challenge of Moving From Conceptualization to Measurement” in Journal of the Association of Pediatric Oncology Nurses (2006, with J. Deatrick), “Changing Patterns of Self-Management in Youth With Type 1 Diabetes” in Journal of Pediatric Nursing (2007, with L. Schilling & M. Grey), and “Parents’Perceptions of Functioning in Families Having a Child With a Genetic Condition” in Journal of Genetic Counseling (2007, G. Knafl, A. Gallo, & D. Angst).

Janet A. Deatrick, RN, PhD, FAAN, is Associate Professor and Associate Director, Center for Health Disparities Research, University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing. Her research encompasses a unique blend of substantive, theoretical, and methodological contributions. She is best known for her research with Kathleen A. Knafl, PhD, FAAN, and Agatha Gallo, PhD, FAAN, in their development of the Family Management Styles Framework and the Family Management Measure (FaMM), which systematically recognizes multidimensional family processes involved in disease management for children with serious health problems. She is currently conducting a study that explores family management with families of adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood brain tumors. Recent publications include “Clarifying the Concept of Normalization” in Image: Journal of Nursing Scholarship (1999, with K. Knafl & C. Moore), “Family Management Styles Framework: A New Tool With Potential to Assess Families Who Have Children With Brain Tumors” in Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing (2005, with A. Thibodeaux, K. Mooney, C. Schmus, R. Pollack, & B. Heib), and “Cultural Influence on Family Management of Children With Cancer” in Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing (2007, with A. Thibodeaux).

Agatha Gallo, RN, PhD, FAAN, is currently a professor in the Department of Maternal-Child Nursing at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Recently, Dr. Gallo has been especially interested in parents’ approaches to managing information within the context of a childhood genetic condition and has received federal funding for her research. Her work has been published in a variety of publication venues and she has presented at the international, national, regional, and local levels. Dr. Gallo has strong expertise in caring for children with chronic conditions and their families as a pediatric nurse practitioner and nurse educator. Recent publications include “Parents’ Concerns About Issues Related to Their Child's Genetic Condition” in Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing (2008, with E. Hadley, D. B. Angst, K. A. Knafl, & C. A. Smith), “Parents’ Perspectives on Interviewing Their Children for Research” in Research in Nursing and Health (2008, with E. Hadley, C. A. Smith, D. B. Angst, & K. Knafl), “Parents Sharing Information With Their Children About Genetic Conditions” in Journal of Pediatric Health Care (2005, with D. Angst, K. Knafl, E. Hadley, & C. Smith).

Appendix Family Management Style Framework: Funded Projects and Publications

Funded Projects

“Hospitalization: Child-Parent-Nurse Perspectives” (R01 NU 00615), funded by the Division of Nursing, DHHS, 09/01/77-08/31/79, $123,520. (Knafl, Principal Investigator)

“How Families Define and Manage a Child's Chronic Illness” (R01 NR01594), funded by National Center of Nursing Research, NIH, 5/1/87-8/31/92, $382,504 (last 2 years funded by competitive continuation award), Minority Supplement, 1991-1992. (Knafl, Principal Investigator)

“Parents’ Interpretation and Use of Genetic Information” (R01 HG02036), funded by National Institute of Human Genome Research, 7/1/01-6/30/05. (Gallo, Principal Investigator)

“Assessing Family Management of Childhood Chronic Illness,” funded by the Donaghue Medical Research Foundation, 10/15/01-12/31/02, $50,000. (Knafl, Principal Investigator)

“Assessing Family Management of Childhood Chronic Illness” (R01 NR08048), funded by National Institute for Nursing Research, 04/01/03-03/31-07, $1,111,312. (Knafl, Principal Investigator)

“Family Management and Survivors of Childhood Brain Tumors,” funded by the Oncology Nursing Society Foundation, 05/01/05-04/30/07, $8,806. (Deatrick, Principal Investigator)

“Mothers as Caregivers for Survivors of Pediatric Brain Tumors” (R01 NR009651-01A1), 7/17/2007-5/31/10, $1,014,000. (Deatrick, Principal Investigator)

Research Reports

(Underlined names are those of students)

Gallo, A. (1990). Family management style in juvenile diabetes: A case illustration. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 5, 23-32,

Gallo, A. (1991). Family adaptation in childhood chronic illness: A case report. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 5, 78-85.

Knafl, K., Breitmayer, B., Gallo, A., & Zoeller, L. (1992). Parents’ views of health care providers: An exploration of the components of a positive working relationship. Children's Health Care, 21, 90-95.

Breitmayer, B., Gallo, A., Knafl, K., & Zoeller, L. (1992). Social competence in children with a chronic illness. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 7, 181-188.

Obrecht, J., Gallo, A., & Knafl, K. (1992). A case illustration of family management style in childhood end-stage renal disease. American Nephrology Nurses Association Journal, 19, 255-260.

McCarthy, S., & Gallo, A. (1992). Family management style: A case illustration. Journal of Nursing, 8, 318-324.

Gallo, A., Schultz, V., & Breitmayer, B. (1992). Descriptions of the illness experience of children by children with chronic renal disease. American Nephrology Nurses’ Association Journal, 19, 190-194

Gallo, A., Breitmayer, B., Knafl, K., & Zoeller, L. (1992). Well siblings of children with chronic illness: Parents’ reports of their psychological adjustment. Pediatric Nursing, 18, 23-27.

Gallo, A., Breitmayer, B., Knafl, K., & Zoeller, L. (1993). Mother's perceptions of family life and sibling adjustment in childhood chronic illness. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 8, 318-324.

Knafl, K., Gallo, A., Zoeller, L., & Breitmayer, B. (1993). Family response to a child's chronic illness: A description of major defining themes. In S. Funk & E. Tornquist (Eds.), Key aspects of caring for the chronically ill: Home and hospital (pp. 290-303). New York: Springer.

Knafl, K., Ayres, L., Gallo, A., Zoeller, L., & Breitmayer, B. (1995). Learning from stories: Parents’ accounts of the pathway to diagnosis. Pediatric Nursing, 21, 411-415.

Kirschbaum, M., & Knafl, K. (1996). Major themes in parent-provider relationships: A comparison of the acute and chronic illness experience. Journal of Family Nursing, 2, 195-216.

Knafl, K., Breitmayer, B., Gallo, A., & Zoeller, L. (1996). Family response to childhood chronic illness: Description of management styles. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 11, 315-326.

Gallo, A., & Knafl, K. (1998). Parents ‘ reports of tricks of the trade for managing childhood chronic illness. Journal of the Society of Pediatric Nurses, 3, 93-100.

Knafl, K., & Zoeller, L. (2000). Childhood chronic illness: A comparison of mothers’ and fathers’ experiences. Journal of Family Nursing, 6, 287-302.

Gallo, A., & Szychlinski, C. (2003). Self concept and family functioning in healthy school-aged siblings of children with asthma and diabetes and healthy children. Journal of Family Nursing, 9, 414-434

Sullivan-Bolyai, S., Knafl, K., Deatrick, J., & Grey, M. (2003). Family management behaviors and tricks of the trade: Mothers of young children with type 1 diabetes. Journal of Maternal Child Nursing, 28, 160-166.

Sullivan-Bolyai, S., Knafl, K., Deatrick, J., & Grey, M. (2003). Maternal management behaviors of young children with type 1 diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 28, 160-166.

Gallo, A., Angst, D., Knafl, K., Hadley, E., & Smith, C. (2005). Parents sharing information with their children about genetic conditions. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 19, 267-275.

Knafl, K., Knafl, G., Gallo, A., & Angst, D. (2007). Parents’ perceptions of functioning in families having a child with a genetic condition. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 16, 481-492.

Gallo, A., Hadley, E., Angst, D., Knafl, K., & Smith, C. (2008). Parents’ concerns about issues related to their child's genetic condition. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing, 13, 4-14.

Concept and Theory Development

Knafl, K. A., & Deatrick, J. (1986). How families manage chronic conditions: An analysis of the concept of normalization. Research in Nursing and Health, 9, 215-222.

Knafl, K. A., & Deatrick, J. A. (1987). Conceptualizing family response to a child's chronic illness or disability. Family Relations, 36, 300-304.

Deatrick, J., & Knafl, K. (1990). Family management behaviors: Concept synthesis. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 5, 15-22.

Knafl, K., & Deatrick, J. (1990). Family management style: Concept analysis and refinement. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 5, 4-14.

Deatrick, J., Knafl, K., & Murphy-Moore, C. (1999). Clarifying the concept of normalization. Image, 31, 209-214.

Knafl, K., & Deatrick, J. (2003). Further refinement of the family management style framework. Journal of Family Nursing, 9, 232-256.

Methodological Papers

Knafl, K. A., & Breitmayer, B. (1989). Triangulation in qualitative research: Issues of conceptual clarity and purpose. In J. Morse (Ed.), Qualitative nursing research: A contemporary dialogue (pp. 209-220). Rockville, MD: Aspen.

Knafl, K., & Breitmayer, B. (1991). Triangulation in qualitative research: Issues of conceptual clarity and purpose. In J. Morse (Ed.), Qualitative nursing research: A contemporary dialogue (rev. ed., pp. 226-239). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Breitmayer, B., Ayres, L., & Knafl, K. (1993). Triangulation in qualitative research: Evaluation of confirmation and completeness purposes. Image, 25, 237-243.

Knafl, K., Gallo, A., Breitmayer, B., Zoeller, L., & Ayres, L. (1993). One approach to conceptualizing family response to illness. In S. Feetham, J. Bell, S. Meister, & K. Gilliss (Eds.), The nursing of families (pp. 70-78). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Knafl, K., & Gallo, A. (1995). Triangulation in nursing research. In L. Talbot (Ed.), Principals and practice of nursing research (pp. 492-509). St. Louis, MO: Mosby.

Knafl, K., & Ayres, L. (1996). Managing large qualitative data sets in family research. Journal of Family Nursing, 2, 350-364.

Ayres, L., Kavanaugh, K., & Knafl, K. (2003). Within and across-case approaches to qualitative data analysis. Journal of Qualitative Health Research, 13, 871-883.

Knafl, K., & Deatrick, J. (2006). Family management style and the challenge of moving from conceptualization to measurement. Journal of the Association of Pediatric Oncology Nurses, 23, 12-18.

Alderfer, M. (2006). Use of family management styles in family intervention research. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 23, 32-35.

Knafl, K., Deatrick, J., Gallo, A., Holcombe, G., Bakitas, M., Dixon, J., & Grey, M. (2007). The analysis and interpretation of cognitive interview for instrument development. Research in Nursing & Health, 30, 224-234.

Smith, C., & Gallo, A. (2007). Performance ethnography in nursing. Qualitative health Research, 17, 521-528.

Hadley, E., Smith, C., Gallo, A., Angst, D., & Knafl, K. (2008). Parents’ perspectives on interviewing their children for research. Research in Nursing & Health, 31, 4-11.

Practice Applications

Knafl, K., Deatrick, J., & Kirby, A. (2001). Normalization promotion. In M. Craft-Rosenberg & J. Denehy (Eds.), Nursing interventions for infants, children, and families (pp. 373-388). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Knafl, K., & Deatrick, J. (2002). The challenge of normalization for families of children with chronic conditions. Pediatric Nursing, 28, 49-56.

Deatrick, J., Thibodeaux, A., Mooney, K., Schmus, C., Pollacki, R., & Davey, B. (2006). Family management style framework: A new tool with potential to assess families who have children with brain tumors. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 23, 19-27.

Nelson, A., Deatrick, J., Knafl, K., Alderfer, M., & Ogle, S. (2006). Consensus statements: The Family Management Style Framework and its use with families of children with cancer. Journal of the Association of Pediatric Oncology Nurses, 23, 36-37.

Ogle, S. (2006). Clinical application of family management styles to families of children with cancer. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 23, 28-31.

Gallo, A., Hadley, E., Angst, D., Knafl, K., & Smith, C. (2008). Parents’ concerns about issues related to their children's genetic conditions. Journal of the Society of Pediatric Nursing, 13, 4-14.

Footnotes

Editor's Note: Chaired and organized by Dr. Janice M. Bell, the plenary address on Family Nursing Research at the 8th International Family Nursing Conference in Thailand featured three papers by Dr. Kathleen Knafl, Dr. Catherine (Kit) Chesla, and Dr. Janice Bell. Beginning with a historical overview about family nursing research, each paper was a brief overview of a program of family nursing research. Dr. Knafl's paper on the development of the Family Management Style Framework is published here with the hope that the other two plenary papers about Family Nursing Research will be included in a future issue of JFN.

Contributor Information

Kathleen Knafl, University of North Carolina Chapel Hill School of Nursing.

Janet A. Deatrick, University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing.

Agatha M. Gallo, University of Illinois at Chicago College of Nursing.

References

- Breitmayer B, Ayres L, Knafl K. Triangulation in qualitative research: Evaluation of completeness and confirmation purposes. Image: Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 1993;25(3):237–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1993.tb00788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deatrick J, Knafl K. Management behaviors: Day-to-day adjustments to childhood chronic conditions. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 1990;5(1):15–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deatrick J, Knafl K, Murphy-Moore C. Clarifying the concept of normalization. Image: Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 1999;31(3):209–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1999.tb00482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deatrick J, Thibodeaux A, Mooney K, Schmus C, Pollacki R, Davey B. Family management style framework: A new tool with potential to assess families who have children with brain tumors. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing. 2006;23:17–27. doi: 10.1177/1043454205283574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo A, Hadley E, Angst D, Knafl K, Smith C. Parents’ concerns about issues related to their children's genetic conditions. Journal of the Society of Pediatric Nursing. 2008;13:4–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6155.2008.00129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knafl K, Ayres L. Managing large qualitative data sets in family research. Journal of Family Nursing. 1996;2(4):350–364. [Google Scholar]

- Knafl KA, Ayres L, Gallo AM, Zoeller LH, Breitmayer BJ. Learning from stories: Parents’ accounts of the pathway to diagnosis. Pediatric Nursing. 1995;21(5):411–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knafl K, Breitmayer B, Gallo A, Zoeller L. Parents’ views of health care providers: An exploration of the components of a positive working relationship. Children's Health Care. 1992;21:90–95. doi: 10.1207/s15326888chc2102_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knafl K, Breitmayer B, Gallo A, Zoeller L. Final report: How families define and manage childhood chronic illness. Grant No. R01594. National Institute of Nursing Research; Bethesda MD: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Knafl K, Breitmayer B, Gallo A, Zoeller L. Family response to childhood chronic illness: Description of management styles. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 1996;11(5):315–326. doi: 10.1016/S0882-5963(05)80065-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knafl K, Deatrick J. How families manage chronic conditions: An analysis of the concept of normalization. Research in Nursing & Health. 1986;9:215–222. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770090306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knafl K, Deatrick J. Family management style: Concept analysis and development. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 1990;5(1):4–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knafl K, Deatrick J. The challenge of normalization for families of children with chronic conditions. Pediatric Nursing. 2002;28:49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Knafl K, Deatrick J. Further refinement of the family management style framework. Journal of Family Nursing. 2003;9:232–256. [Google Scholar]

- Knafl K, Deatrick J, Gallo A, Holcombe G, Bakitis M, Dixon J, et al. The analysis and interpretation of cognitive interviews for instrument development. Research in Nursing and Health. 2007;30:224–234. doi: 10.1002/nur.20195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knafl K, Deatrick J, Kirby A. Normalization promotion. In: Craft-Rosenberg M, Denehy J, editors. Nursing interventions for infants, children, and families. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2001. pp. 373–388. [Google Scholar]

- Knafl K, Gallo A, Breitmayer B, Zoeller L, Ayres L. One approach to conceptualizing family response to illness. In: Feetham S, Bell J, Meister S, Gilliss C, editors. The nursing of families. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1993. pp. 70–78. [Google Scholar]

- Ogle S. Clinical application of family management styles to families of children with cancer. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing. 2006;23:28–31. doi: 10.1177/1043454205283586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. Finding the findings in qualitative studies. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2002;34:213–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2002.00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C, Gallo A. Performance ethnography in nursing. Qualitative Health Research. 2007;17:521–528. doi: 10.1177/1049732306298755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]