Abstract

For years conventional drug design at G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) has mainly focused on the inhibition of a single receptor at a usually well-defined ligand-binding site. The recent discovery of more and more physiologically relevant GPCR dimers/oligomers suggests that selectively targeting these complexes or designing small molecules that inhibit receptor-receptor interactions might provide new opportunities for novel drug discovery. To uncover the fundamental mechanisms and dynamics governing GPCR dimerization/oligomerization, it is crucial to understand the dynamic process of receptor-receptor association, and to identify regions that are suitable for selective drug binding. This minireview highlights current progress in the development of increasingly accurate dynamic molecular models of GPCR oligomers based on structural, biochemical, and biophysical information that has recently appeared in the literature. In view of this new information, there has never been a more exciting time for computational research into GPCRs than at present. Information-driven modern molecular models of GPCR complexes are expected to efficiently guide the rational design of GPCR oligomer-specific drugs, possibly allowing researchers to reach for the high-hanging fruits in GPCR drug discovery, i.e. more potent and selective drugs for efficient therapeutic interventions.

Keywords: GPCRs, dimers, computational methods, molecular modeling, rational drug design

Introduction

G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) are abundant membrane proteins consisting of an extracellular N-terminus, seven highly conserved transmembrane (TM) domains, three intracellular (IC) and three extracellular (EC) loops, and an intracellular C-terminus. Despite their architectural homology, GPCRs can respond to diverse stimuli and initiate various intracellular signaling cascades (Luttrell 2008) in either G-protein-dependent or –independent manners (Delcourt et al. 2007; Lefkowitz 2007). As a result, GPCRs mediate a variety of physiological and pathophysiological processes (Thompson et al. 2008), are the primary targets for about 30% of prescription drugs (Overington et al. 2006), and are likely to be potential targets for new therapeutic drugs (Xiao et al. 2008).

Targeting the orthosteric ligand-binding sites (i.e. the same binding sites recognized by endogenous ligands) of GPCRs for the development of therapeutic drugs has engaged, and continues to engage, many academic researchers and pharmaceutical industries (Lagerstrom and Schioth 2008). However, the growing body of evidence that GPCRs form clinically relevant dimers/oligomers with implications in pain (Finley et al. 2008; Waldhoer et al. 2005), asthma (McGraw et al. 2006), Parkinson's disease (Carriba et al. 2007), schizophrenia (Gonzalez-Maeso et al. 2008), pre-eclampsia hypertension (AbdAlla et al. 2001), and hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (Leanos-Miranda et al. 2005), has generated a great interest in GPCR dimers/oligomers as exciting new targets for novel drug discovery (Panetta and Greenwood 2008).

Small-molecule drug discovery at GPCR dimers is certainly more challenging than conventional GPCR drug discovery at single orthosteric ligand-binding sites, but represents an innovative direction for the 21st century medicine. One of the fundamental challenges in developing GPCR dimer specific drugs is to understand the mechanisms and dynamics governing the interaction between receptor pairs and/or higher-order oligomers. Despite the numerous efforts to explore this issue, the information available is still very limited. This minireview summarizes current progress in the development of increasingly accurate computational models of GPCR oligomers using important structural, biochemical, and biophysical information that has become available in recent literature. These computational models further refined on the basis of detailed structural and dynamic information derived from experiments may provide a more complete understanding of the molecular and energetic basis of GPCR oligomerization, thus facilitating the design of novel GPCR oligomer-specific drugs.

New structural templates for GPCR monomeric models

Over the last ten years, the number of GPCR crystal structures has increased remarkably going from the single crystal structure of bovine rhodopsin in year 2000 (Palczewski et al. 2000) to twenty-four different crystal structures of rhodopsin-like class A GPCRs in year 2008 (Bortolato et al. 2009). Specifically, high-resolution crystal structures are currently available for native and mutant bovine rhodopsin (Li et al. 2004; Nakamichi et al. 2007; Nakamichi and Okada 2006a; Nakamichi and Okada 2006b; Okada et al. 2002; Okada et al. 2004; Palczewski et al. 2000; Salom et al. 2006; Standfuss et al. 2007; Stenkamp 2008; Teller et al. 2001), native bovine opsin (Park et al. 2008; Scheerer et al. 2008), native squid rhodopsin (Murakami and Kouyama 2008; Shimamura et al. 2008), engineered human β2-adrenergic receptor (Cherezov et al. 2007; Hanson et al. 2008; Rasmussen et al. 2007; Rosenbaum et al. 2007), turkey β1-adrenergic receptor mutant (Warne et al. 2008), and engineered human adenosine A2A receptor (Jaakola et al. 2008).

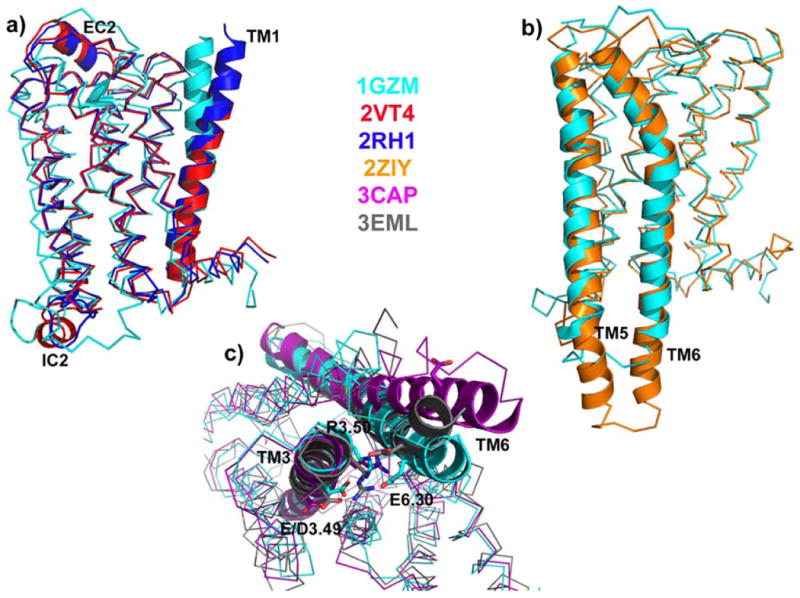

Figure 1 shows global superpositions of representative current GPCR crystallographic structures of bovine rhodopsin, squid rhodopsin, β2-adrenergic receptor, β1-adrenergic receptor, ligand-free bovine opsin, and adenosine A2A receptor corresponding to Protein Data Bank (PDB) (Berman et al. 2000) identification codes 1GZM, 2ZIY, 2RH1, 2VT4, 3CAP, and 3EML, respectively. Although the overall helical-bundle topology is conserved among the different GPCR structures, several differences can be identified from their comparison. Figure 1a shows the largest structural differences between adrenergic and rhodopsin receptors in cartoon representations. For instance, a large difference is observed in TM1 of adrenoceptors compared to bovine rhodopsin due to the lack of a proline-induced kink in this helix. Notably, two of the four β1-adrenergic receptor molecules that were found in the unit cell exhibited a 60° kink in TM1. Another large difference between adrenoceptors and rhodopsin can be ascribed to the pronounced structural plasticity of the EC2 loop of adrenoceptors compared to rhodopsins, and of the IC2 loop of β1-adrenergic receptor compared to all other available GPCR crystal structures. Particularly interesting is the unexpected difference in the conformation of IC2 between β1-adrenergic (short α-helix parallel to the membrane surface) and β2-adrenergic (extended conformation) receptors because of the high sequence conservation between these two cognate receptors. However, one cannot exclude the possibility that crystallographic artifacts and/or experimental conditions may be causing this structural difference.

Figure 1. Structural comparison between representative class A GPCR crystal structures.

Crystal structures of bovine rhodopsin (1GZM), squid rhodopsin (2ZIY), β2-adrenergic receptor (2RH1), β1-adrenergic receptor (2VT4), ligand-free bovine opsin (3CAP), and adenosine A2A receptor (3EML) are depicted in cyan, orange, blue, red, magenta, and grey colors, respectively. a) Global superposition of bovine rhodopsin, β2-adrenergic receptor, and β1-adrenergic receptor with regions exhibiting the largest conformational differences (EC2, IC2, and TM1) shown in cartoon representation; b) Global superposition of squid and bovine rhodopsin with TM5 and TM6 helices in cartoon representation; c) Global superposition (intracellular view) of bovine rhodopsin, ligand-free opsin, and adenosine A2A receptor with “ionic lock” residues E/D3.49, R3.50, and E6.30 in stick representation.

The cytoplasmic side of TM5-TM6 helices also exhibits conformational differences as shown in Figure 1b where a comparison between representative crystal structures of squid (Murakami and Kouyama 2008; Shimamura et al. 2008) and bovine (Li et al. 2004; Palczewski et al. 2000) rhodopsin reveals longer TM5 and TM6 helices and/or a unique IC3 loop in squid rhodopsin. This difference may result in a specific coupling mode of squid rhodopsin with its G-protein linked Gq, suggesting a possible reason for rhodopsin signaling specificity between vertebrates and invertebrates. Another clear structural difference is revealed by comparison of ligand-free bovine opsin with all other available GPCR crystal structures. In fact, opsin crystal structure exhibits a pronounced opening at the cytoplasmic side, achieved by a 6-7 Å outward movement of TM6, and consequent rearrangement of the IC2 and IC3 loop regions. As shown as an example in Figure 1c by global superposition of adenosine A2A, bovine rhodopsin, and ligand-free opsin receptors, bovine rhodopsin is the only crystal structure exhibiting an intact network of hydrogen bonds and charge interactions among residues E/D3.49, R3.50 and E6.30, usually referred to as the “ionic lock”. The two-numeral identifiers refer to the generalized Ballesteros–Weinstein numbering system (Ballesteros and Weinstein 1995) with the first number indicating the TM helix, and the second number indicating the position in the helix with respect to the most conserved residue or position 50 in the amino acid sequence. For β2-adrenergic, β1-adrenergic, and adenosine A2A receptors the possibility cannot be ruled out that changes at the cytoplasmic side of these engineered and/or mutant GPCRs are due to their non-native state and/or the special experimental conditions used for their crystallization, and/or percentage of basal activity. Notably, submicrosecond molecular dynamics simulations of β1 (Vanni et al. 2009) and β2 adrenergic (Dror et al. 2009; Vanni et al. 2009) receptors in a lipid bilayer under physiological conditions recover the “ionic lock” that is absent in the crystal structures. This ionic lock is also present in a complete β1-adrenergic receptor crystal structure recently solved crystallographically in the Schertler's lab (Gebhard F.X. Schertler, personal communication).

Important differences among available GPCR crystal structures are also found at the orthosteric ligand-binding pocket site. While the rhodopsin and adrenoceptor ligand-binding pockets are very similar (albeit different) and their bound ligands make most contacts with TM3, TM5, and TM6, the ligand-binding pocket location is completely different in the adenosine A2A structure. In this structure, the ligand appears to be involved in much closer interactions with TM6 and TM7, because of a shift of the extracellular portions of TM2 and TM5 toward the ligand-binding pocket, and a shift of TM3 toward TM5.

Even slight differences in the arrangement of TM helices and large loops of GPCRs can affect the performance of structure-based drug design strategies applied to this family of receptors. Recent computational work on β2-adrenergic receptor has shown an improvement in the predictive power of the β2 adrenergic receptor crystallographic structure compared to rhodopsin-based models for the discovery of novel chemical classes acting at this receptor (Costanzi 2008; Kolb et al. 2009; Sabio et al. 2008; Topiol and Sabio 2008). This observation highlights the need for more high-resolution crystal structures of GPCRs in their native ligand-binding states, hence for the development and assessment of enhanced expression and purification methods, to improve rational drug design at this family of receptors. Since GPCR structural biology projects are quite complex, and usually require several years of persistent work, homology modeling strategies using better templates can be used in the interim to generate enhanced molecular models for most GPCR subtypes of the human genome. In case of low sequence identity between all GPCR templates and target sequences (e.g., less than 30% sequence identity as recently calculated for membrane proteins (Forrest et al. 2006)), the choice of an available crystal structure over another for homology modeling approaches seems to be quite irrelevant, as neither of these templates are expected to yield reliable molecular models of the receptor under study. Recent calculations carried out in my laboratory (Mobarec et al., manuscript in preparation) suggest that, in case of low template-target sequence identity, multiple templates using all available GPCR crystal structures may provide an improvement over single-template homology modeling strategies for the generation of more accurate overall models. However, these models are not necessarily better models for use in rigid protein-flexible ligand docking strategies aimed at drug design.

New biochemical and biophysical data for GPCR oligomeric models

More and more experimental data support the view that GPCRs exist and function as contact dimers or higher order oligomers with TM regions at the interfaces. In contact dimers/oligomers of GPCRs, the original TM helical-bundle topology of each individual protomer is preserved and interaction interfaces are formed by lipid-exposed surfaces. Although domain-swap models, i.e. models in which domains TM1-5 and TM6-7 would exchange between protomers, have also been proposed in the literature, there is limited direct evidence that supports them (Vohra et al. 2007). On the other hand, compelling experimental evidence exists for the involvement of lipid exposed surfaces of TM1, TM4 and/or TM5 at the dimerization/oligomerization interfaces of several GPCRs (see summary in Table 1). For instance, either the employment of various truncated forms of dopamine D2 receptor (Lee et al. 2003) or cross-linking of cysteine mutants of this receptor (Guo et al. 2005; Guo et al. 2003; Guo et al. 2008) supported the direct involvement of TM4 in the homodimerization of this GPCR. Based on observed differences in the rates of cross-linking at specific locations in the presence of agonists or inverse agonists (Guo et al. 2005), we suggested alternative molecular models of the TM4 interface (with or without the simultaneous involvement of TM5; Figures 2a and 2b, respectively) of dopamine D2 receptor homodimers, and inferred about the likelihood of specific conformational rearrangements of this interface (protomer displacement or exchange) over others (TM4 rotation around its own helical axis) using an elastic network model (Niv and Filizola 2008). That TM4 plays an important role in dimerization has also been reported for serotonin 5-HT4 receptor homodimer (Berthouze et al. 2007), serotonin 5-HT2C homodimer (Mancia et al. 2008), α1b-adrenoceptor homodimer (Carrillo et al. 2004; Lopez-Gimenez et al. 2007), C5a receptor homodimer (Klco et al. 2003), chemokine CCR5 homodimer (Hernanz-Falcon et al. 2004), serotonin 5-HT2A-metabotropic glutamate receptor 2 heterodimer (Gonzalez-Maeso et al. 2008), and corticotropin releasing hormone-VT2 arginine vasotocin receptor heterodimer (Mikhailova et al. 2008) using several approaches, such as receptor fragmentation, mutagenesis, bioluminescence and fluorescence resonance energy transfer (BRET and FRET), disulfide trapping, or self-association. However, TM4 association (with or without the participation of TM5) appears to be only one component of larger oligomeric arrangements, as recently demonstrated for α1b-adrenoceptor (Lopez-Gimenez et al. 2007), C5a receptor homodimer (Klco et al. 2003), chemokine CCR5 homodimer (Hernanz-Falcon et al. 2004), serotonin 5-HT2C receptor (Mancia et al. 2008), and dopamine D2 receptor (Guo et al. 2008) using several techniques including three-color fluorescence resonance energy transfer (3-FRET), bimolecular fluorescence (BiFC) and luminescence (BiLC) complementation, or disulfide-trapping experiments. In the proposed oligomeric arrangements of these receptors, TM1 helices form interfaces in addition to those involving TM4 and/or TM5. Notably, the simultaneous involvement of TM1, TM4, and TM5 at dimerization/oligomerization interfaces was first proposed for murine rhodopsin in native rod outer segments based on inferences from atomic force microscopy topographs (Fotiadis et al. 2003; Liang et al. 2004). Although time-resolved FRET and snap-tag technologies have recently provided further evidence for the oligomeric state of both class A and class C GPCRs (Maurel et al. 2008), the proposed oligomeric arrangement of rhodopsin remains controversial (Chabre et al. 2003).

Table 1.

Examples of GPCRs whose TM1, TM4, and/or TM5 regions have been proven experimentally to play a role in dimerization/oligomerization.

| GPCRsa | TMs | Experimental Approach | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| D2DR | TM1, TM4, TM5 | Truncated forms, cysteine crosslinking, FRET, BRET, BiFC, BiLC | Lee at al., 2003; Guo et al., 2005; Guo et al., 2003; Guo et al., 2008 |

| 5-HT4 | TM4 | BRET | Berthouze et al., 2007 |

| α1b | TM1, TM4 | Truncated forms, FRET | Carrillo et al., 2004; Lopez-Gimenez et al., 2007 |

| C5a | TM1, TM4 | Disulfide trapping | Klco et al., 2003 |

| CCR5 | TM1, TM4 | FRET | Hernanz-Falcon et al., 2004 |

| mGluR2 | TM4, TM5 | co-immunoprecipitation, FRET, allosteric binding | Gonzalez-Maeso et al., 2008 |

| VT2R | TM4 | FRET | Mikhailova et al., 2008 |

| 5-HT2C | TM1, TM4, TM5 | Disulfide trapping | Mancia et al., 2008 |

α1b; α1b-adrenergic receptor; BiFC, bimolecular fluorescence complementation; BiLC, bimolecular luminescence complementation; BRET, bioluminescence resonance energy transfer; CCR5, chemokine CCR5 receptor; C5a, C5a receptor; D2DR, dopamine D2 receptor; FRET, fluorescence resonance energy transfer; mGluR2, metabotropic glutamate receptor; VT2R, Arginine vasotocin receptor; 5-HT4, serotonin 5-HT4 receptor; 5-HT2C, serotonin 5-HT2C receptor

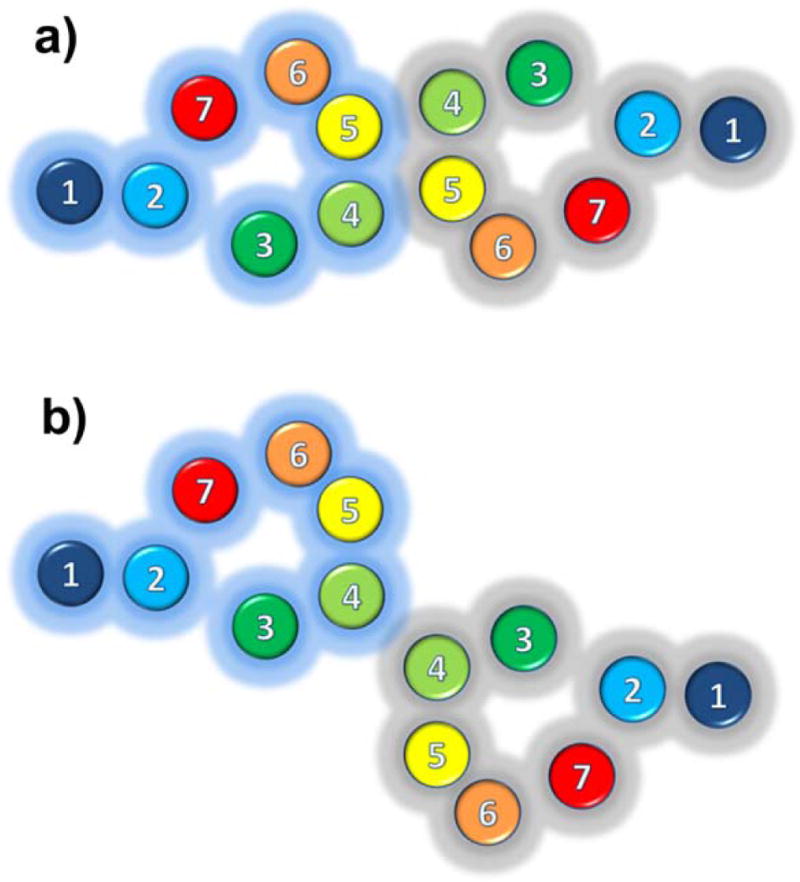

Figure 2. Alternative configurations of the TM4 interface of GPCR dimers.

a) Simultaneous involvement of TM4 and TM5 at the dimerization interface; b) Exclusive involvement of TM4 at the dimerization interface.

Several computational strategies (recently reviewed in (Fanelli and De Benedetti 2006; Filizola and Weinstein 2005; Nemoto and Toh 2006; Reggio 2006; Vohra et al. 2007)) have also predicted TM1, TM4, and/or TM5 as likely dimerization/oligomerization contact interfaces of GPCRs. Among at least 28 different possibilities for TM packing of GPCR homodimers, the preferential involvement of TM4 and/or TM5 in homodimeric interfaces was independently predicted by computational methods for several GPCRs, including adenosine A3 receptor (Kim and Jacobson 2006), dopamine D2 receptor (Filizola et al. 2005; Guo et al. 2005; Nemoto and Toh 2006), rhodopsin (Periole et al. 2007), δ- and κ-opioid receptors (Filizola and Weinstein 2002), and lutropin receptor (Fanelli 2007). Our correlated mutation analysis-based approach further refined on the basis of specific criteria to reduce the number of false positives, identified TM1 and TM4 most often as putative interfaces among experimentally known rhodopsin-like GPCR dimers/oligomers (Filizola et al. 2005; Filizola and Weinstein 2005), including opioid receptors (Filizola et al. 2002; Filizola and Weinstein 2002). In the case of opioid receptors, we predicted TM4 and/or TM5 as the most likely interfaces of δ- and κ-opioid receptor dimerization, and TM1 as the most likely interface of dimerization for μ-opioid receptors. Although it might be conceivable that the molecular determinants at dimerization/oligomerization interfaces can differ even among cognate GPCRs, thus providing a possible rationale for their functional selectivity, it must be kept in mind that the stringent criteria that our original evolutionary-based computational methods used to eliminate as many false positives as possible could be responsible for either missing an actual interface, or favoring a higher-order oligomerization interface in one receptor subtype but not another. Moreover, the accuracy of all these sequence-based computational tools may be impaired by the paucity of amino acid sequences from different organisms available for each GPCR subfamily, which strongly reduces the statistical significance of the dataset used for calculations. Last but not the least, the use of the rhodopsin crystal structure in the original calculations to single out lipid-exposed correlated mutations for predictions of contact dimers/oligomers on the basis of solvent accessibility values may have added an additional level of uncertainty. In fact, the recently revealed differences between rhodopsin and non-rhodopsin GPCR crystal structures are likely to result in some variations in solvent accessibility values at equivalent positions in different GPCRs.

Guided by experiments, we have recently proposed two alternative molecular models of the tetrameric arrangement of dopamine D2 receptor, with both TM1 and helix 8 (H8) at one symmetric homodimer interface, and either TM4 and TM5 or TM4 alone at the other homodimer interface (Guo et al. 2008). Notably, our proposed configuration of the TM1,H8-TM1,H8 interface of the dopamine D2 receptor homodimer based on crosslinking data was obtained using the recent high-resolution crystal structure of the β2-adrenergic receptor (Rasmussen et al. 2007) as a template for each dopamine D2 receptor protomer. The TM1 kink that is present in rhodopsin-based models of dopamine D2 receptor prevented this specific information-driven packing of TM1, which also differed from the symmetric TM1 interfaces of GPCRs in parallel configurations deriving from either crystallography (Cherezov et al. 2007; Murakami and Kouyama 2008; Park et al. 2008; Salom et al. 2006; Scheerer et al. 2008), electron-microscopy (Ruprecht et al. 2004; Schertler 2005), or atomic force microscopy (Fotiadis et al. 2003; Liang et al. 2004). It is worth mentioning here that additional non-symmetric interfaces (e.g., involving TM3 and TM6 helices) were identified in our proposed dopamine D2 receptor oligomeric arrangements, but these additional contacts remain to be tested experimentally.

Although the experimental literature supports more and more the involvement of specific TM helices at dimerization/oligomerization interfaces of GPCRs, the specific contribution of individual amino acids to these interfaces has been more difficult to determine or to generalize. As a consequence, general examples of GPCR dimerization-disrupting mutants of motifs or residues within the TM helices are scarce. For instance, despite the presence of a glycophorin A like GXXXG motif in a few GPCRs, disruption of this motif was suggested to have a detrimental effect on the yeast pheromone receptor dimerization (Gehret et al. 2006; Overton et al. 2003) and the β2-adrenergic receptor (Hebert et al. 1996), but not on the dimerization/oligomerization of α1b-adrenoceptor (Carrillo et al. 2004; Stanasila et al. 2003) or the class B secretin receptor (Lisenbee and Miller 2006). A number of studies employing peptides corresponding to specific TM domains have also been reported to cause GPCR dimerization disruption and/or to modulate function (Harikumar et al. 2006; Ng et al. 1996; Wang et al. 2006). However, although findings of these experiments were generally shown to be specific for the sequences of certain synthetic peptides, a specific peptide-receptor interaction at one site may still modulate the ability of the receptor to form dimers at different interfaces.

Although it is difficult to imagine that single point mutations are sufficient to disrupt entire dimerization/oligomerization interfaces of GPCRs, there are a few pertinent examples in the literature. For instance, mutations of I1.54 and V1.47 of the human chemokine receptor CCR5 were shown to generate nonfunctional receptors that could not dimerize or trigger signaling (Hernanz-Falcon et al. 2004). To facilitate identification of dimerization-disrupting mutants of GPCRs, we have recently contributed to the design of an ad-hoc computational method whose efficacy was tested by comparing experimental data from mutagenesis of the TM helix-helix interface of glycophorin A with computational predictions at that interface (Taylor et al. 2008). Using a rhodopsin homodimer involving TM4 and TM5 at the interface as a template, we predicted sets of three and five dimerization-disrupting mutations, whose effect remains to be tested experimentally.

Small molecules targeting GPCR oligomers

In view of the emerging evidence that GPCR heterodimers can generate very distinct signals from the corresponding homodimers (Milligan 2008), the development of small molecule ligands that are specific for these complexes is attracting a great deal of attention as a potential new way to discover novel drugs with lesser side effects. Co-administration of conventional drugs targeting each of the two protomers in a GPCR dimer may result in limited therapeutic effect due to the potentially different pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of the two drugs. Thus, one must think of alternative approaches (e.g., see approaches schematically depicted in Figure 3) to efficiently target GPCR homo-/hetero-dimers.

Figure 3. Examples of small molecules targeting the TM region of GPCR heterodimers.

(a) Bivalent ligands, i.e. molecules composed of two pharmacophores (green and magenta colors) covalently linked through a spacer (cyan connecting line); (b) Monovalent “drug-like” heterodimer-specific compounds (yellow color), and (c) Interface-disrupting compounds (cyan color).

Bivalent ligands

One proposed approach to target GPCR oligomers is based on the use of so-called bivalent ligands (recently reviewed in (Berque-Bestel et al. 2008)), i.e. ligands composed of two covalently linked (through a spacer) pharmacological recognition units (pharmacophores) which may target the two receptor orthosteric binding sites on a heterodimer simultaneously (Figure 3a). Since these ligands would preferentially bind to the heterodimer in selective tissues and less so to the individual protomers, they are expected to improve significantly receptor selectivity. Portoghese and colleagues were among the first investigators to synthesize in the early 80's bivalent ligands (for opioid receptors), and to suggest that their enhanced potency was associated with simultaneous occupation of proximal recognition sites (Erez et al. 1982; Portoghese et al. 1987; Portoghese et al. 1986a; Portoghese et al. 1985; Portoghese et al. 1986b; Portoghese et al. 1982; Takemori et al. 1990). More recently, they explored the possibility that bivalent ligands could exhibit higher antinociceptive activity compared to that achieved by co-administration of the corresponding individual pharmacophores by targeting a δ-μ opioid receptor heterodimer (Daniels et al. 2005). Specifically, they synthesized several bivalent ligands to δ and μ opioid receptors differing in the length of the spacer between pharmacophores (oxymorphone and naltrindole for μ– and δ-opioid receptors, respectively), and revealed that ligands with certain spacer lengths (e.g., MDAN-18) produced more potent compounds with lesser side effects compared to individual pharmacophores. Portoghese and colleagues also synthesized bivalent ligands composed of δ and κ opioid receptor antagonist pharmacophores (naltrindole and 5′-guanidinonaltrindole for δ- and κ- opioid receptors, respectively) separated by spacers of variable lengths (Xie et al. 2005). One of these bivalent ligands (KND-21) was found to exhibit antinociceptive activity when administered directly to the spinal cord, but not to the brain, thus providing support for the ability of this compound to selectively target a δ- κ opioid receptor complex in the spinal cord. Based on Portoghese's pioneering work, many more GPCR bivalent ligands to orthosteric binding sites have been synthesized over the years (see (Berque-Bestel et al. 2008) for a recent list), although only a few of them have been reported to target GPCR dimers, and to exhibit higher affinity and selectivity in vitro and/or in vivo compared to their monovalent counterparts. Given the recent surge in the number of ligands (see (May et al. 2007) for a recent list) that target allosteric binding sites in GPCRs (i.e. binding sites that lie outside the orthosteric binding sites of endogenous ligands), bivalent ligands targeting simultaneously allosteric and orthosteric sites on GPCR dimers may constitute an additional new source of inspiration for potentially selective new drugs (Antony et al. 2008).

Specific spacer lengths were suggested to be critical parameters for the achievement of optimal bridging and binding to opioid receptor complexes (Daniels et al. 2005). Although an optimal spacer length between 18 and 25 atoms resulted from studies on opioid receptors, there is little or no formal evidence that this observation can be generalized to other GPCRs. Distances calculated between the centers of mass of ligand binding sites of interacting GPCR protomers in refined dimeric/oligomeric molecular models may provide an idea of optimum spacer lengths for bivalent ligands in respect to binding and/or potency for a given receptor. These distances may vary depending on the TM regions at the interface, as well as the specific GPCR dimeric configuration. In our refined dimeric models of opioid receptors (unpublished results), distances between the orthosteric ligand binding sites of the interacting protomers hover around ∼35Å, ∼20Å, and ∼30Å for the TM1-TM1, TM4-TM4, and TM4,5-TM4,5 interfaces, respectively. Nevertheless, it is still unclear how bivalent ligands bind to GPCR heterodimers. Combined efforts by the computational and experimental communities are required to shed light on the molecular determinants that are responsible for selective activation of GPCR heterodimers by bivalent compounds.

Monovalent “drug-like” compounds

Bivalent ligands may not be ideal candidates for orally available drugs, given their reduced drug-likeness according to Lipinski's Rule-of-Five (Lipinski et al. 2001). Reasoning that GPCR dimerization/oligomerization may alter the binding sites of the receptor complex by affecting the dynamics of each individual protomer (Niv and Filizola 2008), the development of monovalent “drug-like” heterodimer-specific compounds (Figure 3b) may be more desirable. A few monovalent “drug-like” compounds that preferentially target heterodimers have recently appeared in the literature. Although not totally selective towards δ- κ opioid receptor heterodimers compared to the respective homodimers, ligand 6′-guanidinonaltrindole (Waldhoer et al. 2005), which exhibits in vivo action as a spinally selective analgesic, constitutes one of the first published examples that, albeit not trivial, the development of more “drug-like” compounds targeting selectively GPCR heterodimers might be truly possible. More recently, dopamine D1 agonist SKF83959 was identified as a selective agonist at the Gq/11-coupled dopamine D1-D2 receptor heterodimer by acting as a full agonist for the D1 receptor and a high-affinity partial agonist for a pertussis toxin-resistant D2 receptor within the complex, while failing to activate adenylate-cyclase coupled D1 or D2 receptors or Gq/11 through D1 receptor homomeric units (Rashid et al. 2007). Examples of compounds that do not bind the heterodimer but selectively bind homodimers also exist in recent literature. One of these compounds is the selective antagonist 8-[2-(4-(2-methoxyphenyl)piperazin-1-yl)ethyl]-8-azaspiro[4,5]decane-7,9-dione (BMY 7378) (Hague et al. 2006), which is unable to detect α(1D)-adrenergic receptor binding sites in native tissues co-expressing α(1B)- and α(1D)-adrenergic receptor, possibly due to the masking effect of α(1B)- α(1D)-adrenergic receptor heterodimers. Although more “drug-like”, the mode of binding of these compounds is equally obscure. One possibility is that one of the interacting protomers in a dimer mediates an allosteric effect that is transmitted to the orthosteric site of the other protomer, such as the latter site is sufficiently perturbed to engender a new pocket. To prove or disprove this type of hypotheses, integrated computational and experimental efforts are required to characterize at the molecular level the nature of the binding of either heterodimer-selective (e.g., 6′ guanidinonaltrindole and SKF83959) or homodimer-selective (e.g., BMY 7378) small molecule ligands. In the meantime, large-scale or high-throughput strategies (recently reviewed in (Gupta et al. 2006; Milligan 2006)) can be employed to screen for more “drug-like” small molecule ligands targeting GPCR homo- and/or heteromers with the ultimate goal of discovering novel drugs of therapeutic interest.

Interface-disrupting compounds

There are several examples in the literature hinting at the relevance of GPCR oligomers to disease (recently reviewed in (Milligan 2008; Panetta and Greenwood 2008)). Since oligomerization might also contribute to the side effects of current therapeutics, the discovery of small molecules that are capable of disrupting dimerization/oligomerization interfaces of GPCRs (Figure 3c) may also identify novel pathways for drug discovery. Discovering small-molecule drugs that inhibit protein-protein interactions is an emerging but still very challenging area in drug design (see (Blazer and Neubig 2008; Wells and McClendon 2007; White et al. 2008) for recent reviews), mostly because of the intrinsic characteristics of protein-protein interfaces. Most protein-protein interfaces consist of large and flat contact areas with no well-defined grooves and pockets (Jones and Thornton 1996; Lo Conte et al. 1999), compared with those involved in small-molecule ligand-protein interactions. However, not all interface residues, but rather a few so-called “hotspots”, are usually essential for recognition and binding, and are therefore expected to disrupt protein-protein interfaces if mutated. As for other proteins, identifying the “hotspots” of GPCR dimerization/oligomerization interfaces (see related discussion in previous section) is not a trivial matter. Even if one had a good idea of GPCR dimerization-disrupting mutants, how to use this information to design small-molecule inhibitors of receptor-receptor interactions is rather complex. Identifying small or medium-sized peptides targeting TM dimerization interfaces of GPCRs may be a good starting point, although it is usually difficult to infer about their specificity. The recent successful computational design of peptides that specifically recognize the TM helices of two closely related integrins (αIIbβ3 and αvβ3) in micelles, bacterial membranes, and mammalian cells through optimization of the geometric complementarity of the target-host complex is somewhat encouraging (Caputo et al. 2008; Yin et al. 2007). These peptides may now serve as lead sequences for the development of more drug-like, small-molecule peptidomimetics inhibitors of integrin protein-protein interactions, which might ultimately find applications as clinical diagnostics or therapeutics.

To the best of my knowledge, there are no current examples of small molecules that are capable of disrupting GPCR dimerization/oligomerization interfaces. Given the considerable progress made in the past few years (see (Blazer and Neubig 2008; Wells and McClendon 2007; White et al. 2008) for recent reviews) towards developing small molecules inhibitors of protein-protein interfaces, including inhibitors of several critical components of G-protein signaling pathways (Blazer and Neubig 2008), the expectation is that these and other successes will encourage more interest and research in developing small-molecules targeting the interfaces of GPCR pairs and/or higher order oligomers.

Concluding remarks and outlook

Albeit challenging, targeting GPCR dimers/oligomers has generated a great deal of excitement about a new opportunity to discover more potent and selective drugs with lesser side effects. The wealth of new structural, biochemical, and biophysical information on GPCR monomers and dimers/oligomers that is recently appearing in the literature offers us a unique opportunity to build increasingly accurate computational models of GPCR complex systems. These models, eventually refined on the basis of detailed structural and dynamic information obtained from experiments, may be used in combined efforts by the computational and experimental communities to identify the molecular determinants that are responsible for selective activation of functional GPCR heterodimers, with the ultimate goal of developing small-molecule therapeutics targeting these receptor complexes. This is a non-trivial and very challenging process, as hopefully evinced by this manuscript. Priorities for the future include the development of advanced computational strategies to study at an atomic-level resolution the dynamic activation mechanisms of GPCR oligomers in the presence of their interacting G-proteins and explicit representations of their physiological environment. Integration of these computational studies with newly developed experimental tools able to analyze the influence of heteromerization on GPCR function and pharmacology is expected to produce new major breakthroughs in the GPCR field in the not too distant future with the long-awaited development of novel potent drugs with lesser side effects acting at these receptors. To further facilitate discovery through rational design of new physiological and pharmacological experiments on GPCR oligomers, we are currently developing a GPCR-Oligomerization Knowledge Base (GPCR-OKB) (Skrabanek et al. 2007) that will store up-to-date computational and experimental information on GPCR oligomers under the expert supervision of experimental leaders in the field. This soon-to-be-released database uses recommendations for the recognition and nomenclature of GPCR heteromers defined by the International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology (Pin et al. 2007).

Acknowledgments

Our work on GPCR dimerization/oligomerization is supported by NIH grants DA017976, DA020032, and DA026434 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The author wishes to thank Dr. Andrea Bortolato for helping generate Figure 1.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- AbdAlla S, Lother H, el Massiery A, Quitterer U. Increased AT(1) receptor heterodimers in preeclampsia mediate enhanced angiotensin II responsiveness. Nature Medicine. 2001;7(9):1003–1009. doi: 10.1038/nm0901-1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antony J, Kellershohn K, Mohr-Andra M, Kebig A, Prilla S, Muth M, Heller E, Disingrini T, Dallanoce C, Bertoni S, Schrobang J, Trankle C, Kostenis E, Christopoulos A, Holtje HD, Barocelli E, De Amici M, Holzgrabe U, Mohr K. Dualsteric GPCR targeting: a novel route to binding and signaling pathway selectivity. Faseb Journal. 2008 doi: 10.1096/fj.08-114751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballesteros JA, Weinstein H. Methods in Neurosciences. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 1995. Integrated methods for the construction of three-dimensional models and computational probing of structure-function relations in G protein-coupled receptors; pp. 366–428. [Google Scholar]

- Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, Gilliland G, Bhat TN, Weissig H, Shindyalov IN, Bourne PE. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Research. 2000;28(1):235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berque-Bestel I, Lezoualc'h F, Jockers R. Bivalent ligands as specific pharmacological tools for g protein-coupled receptor dimers. Current Drug Discovery Technology. 2008;5(4):312–318. doi: 10.2174/157016308786733591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthouze M, Rivail L, Lucas A, Ayoub MA, Russo O, Sicsic S, Fischmeister R, Berque-Bestel I, Jockers R, Lezoualc'h F. Two transmembrane Cys residues are involved in 5-HT4 receptor dimerization. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communication. 2007;356(3):642–647. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazer LL, Neubig RR. Small Molecule Protein-Protein Interaction Inhibitors as CNS Therapeutic Agents: Current Progress and Future Hurdles. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008 doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortolato A, Mobarec JC, Provasi D, Filizola M. Progress in Elucidating the Structural and Dynamic Character of G-Protein Coupled Receptor Oligomers for Use in Drug Discovery. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2009 doi: 10.2174/138161209789824768. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caputo GA, Litvinov RI, Li W, Bennett JS, Degrado WF, Yin H. Computationally designed peptide inhibitors of protein-protein interactions in membranes. Biochemistry. 2008;47(33):8600–8606. doi: 10.1021/bi800687h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carriba P, Ortiz O, Patkar K, Justinova Z, Stroik J, Themann A, Muller C, Woods AS, Hope BT, Ciruela F, Casado V, Canela EI, Lluis C, Goldberg SR, Moratalla R, Franco R, Ferre S. Striatal adenosine A2A and cannabinoid CB1 receptors form functional heteromeric complexes that mediate the motor effects of cannabinoids. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32(11):2249–2259. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo JJ, Lopez-Gimenez JF, Milligan G. Multiple interactions between transmembrane helices generate the oligomeric alpha1b-adrenoceptor. Molecular Pharmacology. 2004;66(5):1123–1137. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.001586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabre M, Cone R, Saibil H. Biophysics: is rhodopsin dimeric in native retinal rods? Nature. 2003;426(6962):30–31. doi: 10.1038/426030b. discussion 31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherezov V, Rosenbaum DM, Hanson MA, Rasmussen SG, Thian FS, Kobilka TS, Choi HJ, Kuhn P, Weis WI, Kobilka BK, Stevens RC. High-resolution crystal structure of an engineered human beta2-adrenergic G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 2007;318(5854):1258–1265. doi: 10.1126/science.1150577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costanzi S. On the applicability of GPCR homology models to computer-aided drug discovery: a comparison between in silico and crystal structures of the beta2-adrenergic receptor. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2008;51(10):2907–2914. doi: 10.1021/jm800044k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels DJ, Lenard NR, Etienne CL, Law PY, Roerig SC, Portoghese PS. Opioid-induced tolerance and dependence in mice is modulated by the distance between pharmacophores in a bivalent ligand series. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science U S A. 2005;102(52):19208–19213. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506627102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delcourt N, Bockaert J, Marin P. GPCR-jacking: from a new route in RTK signalling to a new concept in GPCR activation. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 2007;28(12):602–607. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dror RO, Arlow DH, Borhani DW, Jensen MO, Piana S, Shaw DE. Identification of two distinct inactive conformations of the beta2-adrenergic receptor reconciles structural and biochemical observations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(12):4689–4694. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811065106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erez M, Takemori AE, Portoghese PS. Narcotic antagonistic potency of bivalent ligands which contain beta-naltrexamine. Evidence for bridging between proximal recognition sites. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 1982;25(7):847–849. doi: 10.1021/jm00349a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanelli F. Dimerization of the lutropin receptor: insights from computational modeling. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2007:260–262. 59–64. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2005.12.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanelli F, De Benedetti PG. Inactive and active states and supramolecular organization of GPCRs: insights from computational modeling. Journal of Computer Aided Molecular Design. 2006;20(78):449–461. doi: 10.1007/s10822-006-9064-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filizola M, Guo W, Javitch JA, Weinstein H. Oligomerization domains of G-protein Coupled Receptors: Insights into the structural basis of GPCR association. In: Devi LA, editor. Contemporary Clinical Neuroscience: The G Protein-Coupled Receptor Handbook. Totowa, NJ: 2005. pp. 243–265. [Google Scholar]

- Filizola M, Olmea O, Weinstein H. Prediction of heterodimerization interfaces of G-protein coupled receptors with a new subtractive correlated mutation method. Protein Engineering. 2002;15(11):881–885. doi: 10.1093/protein/15.11.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filizola M, Weinstein H. Structural models for dimerization of G-protein coupled receptors: the opioid receptor homodimers. Biopolymers. 2002;66(5):317–325. doi: 10.1002/bip.10311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filizola M, Weinstein H. The study of G-protein coupled receptor oligomerization with computational modeling and bioinformatics. Febs Journal. 2005;272(12):2926–2938. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finley MJ, Chen X, Bardi G, Davey P, Geller EB, Zhang L, Adler MW, Rogers TJ. Bidirectional heterologous desensitization between the major HIV-1 co-receptor CXCR4 and the kappa-opioid receptor. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 2008;197(2):114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest LR, Tang CL, Honig B. On the accuracy of homology modeling and sequence alignment methods applied to membrane proteins. Biophysical Journal. 2006;91(2):508–517. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.082313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fotiadis D, Liang Y, Filipek S, Saperstein DA, Engel A, Palczewski K. Atomic-force microscopy: Rhodopsin dimers in native disc membranes. Nature. 2003;421(6919):127–128. doi: 10.1038/421127a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehret AU, Bajaj A, Naider F, Dumont ME. Oligomerization of the yeast alpha-factor receptor: implications for dominant negative effects of mutant receptors. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281(30):20698–20714. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513642200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Maeso J, Ang RL, Yuen T, Chan P, Weisstaub NV, Lopez-Gimenez JF, Zhou M, Okawa Y, Callado LF, Milligan G, Gingrich JA, Filizola M, Meana JJ, Sealfon SC. Identification of a serotonin/glutamate receptor complex implicated in psychosis. Nature. 2008;452(7183):93–97. doi: 10.1038/nature06612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W, Shi L, Filizola M, Weinstein H, Javitch JA. Crosstalk in G protein-coupled receptors: changes at the transmembrane homodimer interface determine activation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences U S A. 2005;102(48):17495–17500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508950102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W, Shi L, Javitch JA. The fourth transmembrane segment forms the interface of the dopamine D2 receptor homodimer. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(7):4385–4388. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200679200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W, Urizar E, Kralikova M, Mobarec JC, Shi L, Filizola M, Javitch JA. Dopamine D2 receptors form higher order oligomers at physiological expression levels. Embo Journal. 2008;27(17):2293–2304. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A, Decaillot FM, Devi LA. Targeting opioid receptor heterodimers: strategies for screening and drug development. Aaps Journal. 2006;8(1):E153–159. doi: 10.1208/aapsj080118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hague C, Lee SE, Chen Z, Prinster SC, Hall RA, Minneman KP. Heterodimers of alpha1B- and alpha1D-adrenergic receptors form a single functional entity. Molecular Pharmacology. 2006;69(1):45–55. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.014985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson MA, Cherezov V, Griffith MT, Roth CB, Jaakola VP, Chien EY, Velasquez J, Kuhn P, Stevens RC. A specific cholesterol binding site is established by the 2.8 A structure of the human beta2-adrenergic receptor. Structure. 2008;16(6):897–905. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harikumar KG, Dong M, Cheng Z, Pinon DI, Lybrand TP, Miller LJ. Transmembrane segment peptides can disrupt cholecystokinin receptor oligomerization without affecting receptor function. Biochemistry. 2006;45(49):14706–14716. doi: 10.1021/bi061107n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert TE, Moffett S, Morello JP, Loisel TP, Bichet DG, Barret C, Bouvier M. A peptide derived from a beta2-adrenergic receptor transmembrane domain inhibits both receptor dimerization and activation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271(27):16384–16392. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.27.16384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernanz-Falcon P, Rodriguez-Frade JM, Serrano A, Juan D, del Sol A, Soriano SF, Roncal F, Gomez L, Valencia A, Martinez AC, Mellado M. Identification of amino acid residues crucial for chemokine receptor dimerization. Nature Immunology. 2004;5(2):216–223. doi: 10.1038/ni1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaakola VP, Griffith MT, Hanson MA, Cherezov V, Chien EY, Lane JR, Ijzerman AP, Stevens RC. The 2.6 angstrom crystal structure of a human A2A adenosine receptor bound to an antagonist. Science. 2008;322(5905):1211–1217. doi: 10.1126/science.1164772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones S, Thornton JM. Principles of protein-protein interactions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences U S A. 1996;93(1):13–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SK, Jacobson KA. Computational prediction of homodimerization of the A3 adenosine receptor. Journal of Molecular Graphics & Modeling. 2006;25(4):549–561. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klco JM, Lassere TB, Baranski TJ. C5a receptor oligomerization. I. Disulfide trapping reveals oligomers and potential contact surfaces in a G protein-coupled receptor. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(37):35345–35353. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305606200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb P, Rosenbaum DM, Irwin JJ, Fung JJ, Kobilka BK, Shoichet BK. Structure-based discovery of {beta}2-adrenergic receptor ligands. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(16):6843–6848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812657106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagerstrom MC, Schioth HB. Structural diversity of G protein-coupled receptors and significance for drug discovery. Nature Reviews in Drug Discovery. 2008;7(4):339–357. doi: 10.1038/nrd2518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leanos-Miranda A, Ulloa-Aguirre A, Janovick JA, Conn PM. In vitro coexpression and pharmacological rescue of mutant gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptors causing hypogonadotropic hypogonadism in humans expressing compound heterozygous alleles. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2005;90(5):3001–3008. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SP, O'Dowd BF, Rajaram RD, Nguyen T, George SR. D2 dopamine receptor homodimerization is mediated by multiple sites of interaction, including an intermolecular interaction involving transmembrane domain 4. Biochemistry. 2003;42(37):11023–11031. doi: 10.1021/bi0345539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefkowitz RJ. Seven transmembrane receptors: a brief personal retrospective. Biochemical & Biophysical Acta. 2007;1768(4):748–755. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Edwards PC, Burghammer M, Villa C, Schertler GF. Structure of bovine rhodopsin in a trigonal crystal form. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2004;343(5):1409–1438. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.08.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y, Fotiadis D, Maeda T, Maeda A, Modzelewska A, Filipek S, Saperstein DA, Engel A, Palczewski K. Rhodopsin signaling and organization in heterozygote rhodopsin knockout mice. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(46):48189–48196. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408362200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, Feeney PJ. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2001;46(13):3–26. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisenbee CS, Miller LJ. Secretin receptor oligomers form intracellularly during maturation through receptor core domains. Biochemistry. 2006;45(27):8216–8226. doi: 10.1021/bi060494y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Conte L, Chothia C, Janin J. The atomic structure of protein-protein recognition sites. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1999;285(5):2177–2198. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Gimenez JF, Canals M, Pediani JD, Milligan G. The alpha1b-adrenoceptor exists as a higher-order oligomer: effective oligomerization is required for receptor maturation, surface delivery, and function. Molecular Pharmacology. 2007;71(4):1015–1029. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.033035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luttrell LM. Reviews in molecular biology and biotechnology: transmembrane signaling by G protein-coupled receptors. Molecular Biotechnology. 2008;39(3):239–264. doi: 10.1007/s12033-008-9031-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancia F, Assur Z, Herman AG, Siegel R, Hendrickson WA. Ligand sensitivity in dimeric associations of the serotonin 5HT2c receptor. EMBO Reports. 2008;9(4):363–369. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurel D, Comps-Agrar L, Brock C, Rives ML, Bourrier E, Ayoub MA, Bazin H, Tinel N, Durroux T, Prezeau L, Trinquet E, Pin JP. Cell-surface protein-protein interaction analysis with time-resolved FRET and snap-tag technologies: application to GPCR oligomerization. Nature Methods. 2008;5(6):561–567. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May LT, Leach K, Sexton PM, Christopoulos A. Allosteric modulation of G protein-coupled receptors. Annual Reviews in Pharmacology & Toxicology. 2007;47:1–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.47.120505.105159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGraw DW, Mihlbachler KA, Schwarb MR, Rahman FF, Small KM, Almoosa KF, Liggett SB. Airway smooth muscle prostaglandin-EP1 receptors directly modulate beta2-adrenergic receptors within a unique heterodimeric complex. Journal of Clinical Investigations. 2006;116(5):1400–1409. doi: 10.1172/JCI25840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikhailova MV, Blansett J, Jacobi S, Mayeux PR, Cornett LE. Transmembrane domain IV of the Gallus gallus VT2 vasotocin receptor is essential for forming a heterodimer with the corticotrophin releasing hormone receptor. Journal of Biomedical Optics. 2008;13(3):031208. doi: 10.1117/1.2943285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milligan G. G-protein-coupled receptor heterodimers: pharmacology, function and relevance to drug discovery. Drug Discovery Today. 2006;11(1112):541–549. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milligan G. A day in the life of a G protein-coupled receptor: the contribution to function of G protein-coupled receptor dimerization. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2008;153 1:S216–229. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami M, Kouyama T. Crystal structure of squid rhodopsin. Nature. 2008;453(7193):363–367. doi: 10.1038/nature06925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamichi H, Buss V, Okada T. Photoisomerization mechanism of rhodopsin and 9-cis-rhodopsin revealed by x-ray crystallography. Biophysical Journal. 2007;92(12):L106–108. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.108225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamichi H, Okada T. Crystallographic analysis of primary visual photochemistry. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2006a;45(26):4270–4273. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamichi H, Okada T. Local peptide movement in the photoreaction intermediate of rhodopsin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences U S A. 2006b;103(34):12729–12734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601765103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemoto W, Toh H. Membrane interactive alpha-helices in GPCRs as a novel drug target. Current Protein & Peptide Science. 2006;7(6):561–575. doi: 10.2174/138920306779025657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng GY, O'Dowd BF, Lee SP, Chung HT, Brann MR, Seeman P, George SR. Dopamine D2 receptor dimers and receptor-blocking peptides. Biochemical & Biophysical Research Communications. 1996;227(1):200–204. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niv MY, Filizola M. Influence of oligomerization on the dynamics of G-protein coupled receptors as assessed by normal mode analysis. Proteins. 2008;71(2):575–586. doi: 10.1002/prot.21787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada T, Fujiyoshi Y, Silow M, Navarro J, Landau EM, Shichida Y. Functional role of internal water molecules in rhodopsin revealed by X-ray crystallography. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences U S A. 2002;99(9):5982–5987. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082666399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada T, Sugihara M, Bondar AN, Elstner M, Entel P, Buss V. The retinal conformation and its environment in rhodopsin in light of a new 2.2 A crystal structure. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2004;342(2):571–583. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overington JP, Al-Lazikani B, Hopkins AL. How many drug targets are there? Nature Reviews in Drug Discovery. 2006;5(12):993–996. doi: 10.1038/nrd2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overton MC, Chinault SL, Blumer KJ. Oligomerization, biogenesis, and signaling is promoted by a glycophorin A-like dimerization motif in transmembrane domain 1 of a yeast G protein-coupled receptor. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(49):49369–49377. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308654200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palczewski K, Kumasaka T, Hori T, Behnke CA, Motoshima H, Fox BA, Le Trong I, Teller DC, Okada T, Stenkamp RE, Yamamoto M, Miyano M. Crystal structure of rhodopsin: A G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 2000;289(5480):739–745. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5480.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panetta R, Greenwood MT. Physiological relevance of GPCR oligomerization and its impact on drug discovery. Drug Discovery Today. 2008;13(2324):1059–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JH, Scheerer P, Hofmann KP, Choe HW, Ernst OP. Crystal structure of the ligand-free G-protein-coupled receptor opsin. Nature. 2008;454(7201):183–187. doi: 10.1038/nature07063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Periole X, Huber T, Marrink SJ, Sakmar TP. G protein-coupled receptors self-assemble in dynamics simulations of model bilayers. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129(33):10126–10132. doi: 10.1021/ja0706246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pin JP, Neubig R, Bouvier M, Devi L, Filizola M, Javitch JA, Lohse MJ, Milligan G, Palczewski K, Parmentier M, Spedding M. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXVII. Recommendations for the recognition and nomenclature of G protein-coupled receptor heteromultimers. Pharmacological Reviews. 2007;59(1):5–13. doi: 10.1124/pr.59.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portoghese PS, Larson DL, Ronsisvalle G, Schiller PW, Nguyen TM, Lemieux C, Takemori AE. Hybrid bivalent ligands with opiate and enkephalin pharmacophores. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 1987;30(11):1991–1994. doi: 10.1021/jm00394a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portoghese PS, Larson DL, Sayre LM, Yim CB, Ronsisvalle G, Tam SW, Takemori AE. Opioid agonist and antagonist bivalent ligands. The relationship between spacer length and selectivity at multiple opioid receptors. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 1986a;29(10):1855–1861. doi: 10.1021/jm00160a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portoghese PS, Larson DL, Yim CB, Sayre LM, Ronsisvalle G, Lipkowski AW, Takemori AE, Rice KC, Tam SW. Stereostructure-activity relationship of opioid agonist and antagonist bivalent ligands. Evidence for bridging between vicinal opioid receptors. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 1985;28(9):1140–1141. doi: 10.1021/jm00147a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portoghese PS, Ronsisvalle G, Larson DL, Takemori AE. Synthesis and opioid antagonist potencies of naltrexamine bivalent ligands with conformationally restricted spacers. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 1986b;29(9):1650–1653. doi: 10.1021/jm00159a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portoghese PS, Ronsisvalle G, Larson DL, Yim CB, Sayre LM, Takemori AE. Opioid agonist and antagonist bivalent ligands as receptor probes. Life Sciences. 1982;31(1213):1283–1286. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(82)90362-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashid AJ, So CH, Kong MM, Furtak T, El-Ghundi M, Cheng R, O'Dowd BF, George SR. D1-D2 dopamine receptor heterooligomers with unique pharmacology are coupled to rapid activation of Gq/11 in the striatum. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences U S A. 2007;104(2):654–659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604049104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen SG, Choi HJ, Rosenbaum DM, Kobilka TS, Thian FS, Edwards PC, Burghammer M, Ratnala VR, Sanishvili R, Fischetti RF, Schertler GF, Weis WI, Kobilka BK. Crystal structure of the human beta2 adrenergic G-protein-coupled receptor. Nature. 2007;450(7168):383–387. doi: 10.1038/nature06325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reggio PH. Computational methods in drug design: modeling G protein-coupled receptor monomers, dimers, and oligomers. Aaps Journal. 2006;8(2):E322–336. doi: 10.1007/BF02854903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum DM, Cherezov V, Hanson MA, Rasmussen SG, Thian FS, Kobilka TS, Choi HJ, Yao XJ, Weis WI, Stevens RC, Kobilka BK. GPCR engineering yields high-resolution structural insights into beta2-adrenergic receptor function. Science. 2007;318(5854):1266–1273. doi: 10.1126/science.1150609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruprecht JJ, Mielke T, Vogel R, Villa C, Schertler GF. Electron crystallography reveals the structure of metarhodopsin I. Embo Journal. 2004;23(18):3609–3620. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabio M, Jones K, Topiol S. Use of the X-ray structure of the beta2-adrenergic receptor for drug discovery. Part 2: Identification of active compounds. Bioorganic Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2008;18(20):5391–5395. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salom D, Lodowski DT, Stenkamp RE, Le Trong I, Golczak M, Jastrzebska B, Harris T, Ballesteros JA, Palczewski K. Crystal structure of a photoactivated deprotonated intermediate of rhodopsin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences U S A. 2006;103(44):16123–16128. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608022103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheerer P, Park JH, Hildebrand PW, Kim YJ, Krauss N, Choe HW, Hofmann KP, Ernst OP. Crystal structure of opsin in its G-protein-interacting conformation. Nature. 2008;455(7212):497–502. doi: 10.1038/nature07330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schertler GF. Structure of rhodopsin and the metarhodopsin I photointermediate. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 2005;15(4):408–415. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimamura T, Hiraki K, Takahashi N, Hori T, Ago H, Masuda K, Takio K, Ishiguro M, Miyano M. Crystal structure of squid rhodopsin with intracellularly extended cytoplasmic region. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283(26):17753–17756. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C800040200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skrabanek L, Murcia M, Bouvier M, Devi L, George SR, Lohse MJ, Milligan G, Neubig R, Palczewski K, Parmentier M, Pin JP, Vriend G, Javitch JA, Campagne F, Filizola M. Requirements and ontology for a G protein-coupled receptor oligomerization knowledge base. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:177. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanasila L, Perez JB, Vogel H, Cotecchia S. Oligomerization of the alpha 1a- and alpha 1b-adrenergic receptor subtypes. Potential implications in receptor internalization. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(41):40239–40251. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306085200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Standfuss J, Xie G, Edwards PC, Burghammer M, Oprian DD, Schertler GF. Crystal structure of a thermally stable rhodopsin mutant. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2007;372(5):1179–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenkamp RE. Alternative models for two crystal structures of bovine rhodopsin. Acta Crystallographica D Biological Crystallography. 2008;D64:902–904. doi: 10.1107/S0907444908017162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takemori AE, Yim CB, Larson DL, Portoghese PS. Long-acting agonist and antagonist activities of naltrexamine bivalent ligands in mice. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1990;186(23):285–288. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(90)90445-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor MS, Fung HK, Rajgaria R, Filizola M, Weinstein H, Floudas CA. Mutations affecting the oligomerization interface of G-protein-coupled receptors revealed by a novel de novo protein design framework. Biophysical Journal. 2008;94(7):2470–2481. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.117622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teller DC, Okada T, Behnke CA, Palczewski K, Stenkamp RE. Advances in determination of a high-resolution three-dimensional structure of rhodopsin, a model of G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) Biochemistry. 2001;40(26):7761–7772. doi: 10.1021/bi0155091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson MD, Cole DE, Jose PA. Pharmacogenomics of G protein-coupled receptor signaling: insights from health and disease. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2008;448:77–107. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-205-2_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topiol S, Sabio M. Use of the X-ray structure of the Beta2-adrenergic receptor for drug discovery. Bioorganic Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2008;18(5):1598–1602. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanni S, Neri M, Tavernelli I, Rothlisberger U. Observation of Ionic Lock Formation in Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Wild Type 1 and 2 Adrenergic Receptors. Biochemistry. 2009 doi: 10.1021/bi900299f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vohra S, Chintapalli SV, Illingworth CJ, Reeves PJ, Mullineaux PM, Clark HS, Dean MK, Upton GJ, Reynolds CA. Computational studies of Family A and Family B GPCRs. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2007;35(Pt 4):749–754. doi: 10.1042/BST0350749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldhoer M, Fong J, Jones RM, Lunzer MM, Sharma SK, Kostenis E, Portoghese PS, Whistler JL. A heterodimer-selective agonist shows in vivo relevance of G protein-coupled receptor dimers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences U S A. 2005;102(25):9050–9055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501112102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, He L, Combs CA, Roderiquez G, Norcross MA. Dimerization of CXCR4 in living malignant cells: control of cell migration by a synthetic peptide that reduces homologous CXCR4 interactions. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2006;5(10):2474–2483. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warne T, Serrano-Vega MJ, Baker JG, Moukhametzianov R, Edwards PC, Henderson R, Leslie AG, Tate CG, Schertler GF. Structure of a beta1-adrenergic G-protein-coupled receptor. Nature. 2008;454(7203):486–491. doi: 10.1038/nature07101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells JA, McClendon CL. Reaching for high-hanging fruit in drug discovery at protein-protein interfaces. Nature. 2007;450(7172):1001–1009. doi: 10.1038/nature06526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White AW, Westwell AD, Brahemi G. Protein-protein interactions as targets for small-molecule therapeutics in cancer. Expert Reviews in Molecular Medicine. 2008;10:e8. doi: 10.1017/S1462399408000641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao SH, Reagan JD, Lee PH, Fu A, Schwandner R, Zhao X, Knop J, Beckmann H, Young SW. High throughput screening for orphan and liganded GPCRs. Combinatorial Chemistry and High Throughput Screening. 2008;11(3):195–215. doi: 10.2174/138620708783877762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Z, Bhushan RG, Daniels DJ, Portoghese PS. Interaction of bivalent ligand KDN21 with heterodimeric delta-kappa opioid receptors in human embryonic kidney 293 cells. Molecular Pharmacology. 2005;68(4):1079–1086. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.012070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin H, Slusky JS, Berger BW, Walters RS, Vilaire G, Litvinov RI, Lear JD, Caputo GA, Bennett JS, DeGrado WF. Computational design of peptides that target transmembrane helices. Science. 2007;315(5820):1817–1822. doi: 10.1126/science.1136782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]