Abstract

Background and purpose:

Activation of muscarinic M3 mucarinic acetylcholine receptors (M3-mAChRs) has been previously shown to confer short-term cardioprotection against ischaemic injuries. However, it is not known whether activation of these receptors can provide delayed cardioprotection. Consequently, the present study was undertaken to investigate whether stimulation of M3-mAChRs can induce delayed preconditioning in rats, and to characterize the potential mechanism.

Experimental approach:

Rats were pretreated (24 h), respectively, with M3-mAChRs agonist choline, M3-mAChRs antagonist 4-DAMP or M2-mAChRs antagonist methoctramine followed by the administration of choline. This was followed by 30 min of ischaemia and then 3 h of reperfusion. Ischaemia-induced arrhythmias and ischaemia–reperfusion (I/R)-induced infarction were determined. The phosphorylation status of connexin43 (Cx43) after 30 min ischaemia, and the expression level of Hsp70, cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and iNOS effected by administration of choline were also measured.

Key results:

Compared to the control group, pretreatment with choline significantly decreased ischaemia-induced arrhythmias, reduced the total number of ventricular premature beats, the duration of ventricular tachycardia episodes and markedly reduced I/R-induced infarct size. Furthermore, choline attenuated ischaemia-induced dephosphorylation of Cx43, and up-regulated the expression of Hsp70 and COX-2. Administration of 4-DAMP abolished these changes, while methoctramine had no effect.

Conclusions and implications:

Our results suggest that stimulation of M3-mAChRs with choline elicits delayed preconditioning, which we propose is the result of up-regulation of the expression of COX-2 and inhibition of the ischaemia-induced dephosphorylation of Cx43. Therefore, M3-mAChRs represent a promising target for rendering cardiomyocytes tolerant to ischaemic injury.

Keywords: M3-mAChRs, delayed preconditioning, arrhythmia, infarction, Hsp70, Cx43, COX-2, iNOS

Introduction

Myocardial ischaemic preconditioning (IPC) is a phenomenon whereby brief episodes of ischaemia–reperfusion (I/R) protect the heart from subsequent prolonged ischaemic injury. This phenomenon, which was first described by Murry et al. (1986), has led to an enormous amount of research to characterize the underlying mechanisms. Studies have demonstrated that IPC reduces infarct size (IS) (Murry et al., 1986; Lott et al., 1996), improves cardiac function recovery (Takano et al., 2000) and also has beneficial effects by attenuating ischaemia- or reperfusion-induced arrhythmias (Shiki and Hearse, 1987; Kaszala et al., 1996). It is well documented that the IPC can be classified into two phases: early preconditioning, which lasts only 1–3 h, and delayed preconditioning, which starts 24 h later and can extend to 72–96 h (Pagliaro et al., 2001; Eisen et al., 2004; Das and Das, 2008). While IPC has been documented in human hearts in vivo and in vitro (Yellon et al., 1993; Ikonomidis et al., 1994; Cohen et al., 1998; Ghosh et al., 2000; Lambiase et al., 2003), using ischaemia to precondition the heart is not a viable, therapeutic strategy.

Interestingly, activation of many receptors has been demonstrated to mimic IPC, including the activation of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (mAChRs). Carbachol can protect the heart from ischaemic insult in a fashion similar to IPC in rabbits and rats (Thornton et al., 1993; Yamaguchi et al., 1997). Acetylcholine has also been shown to induce preconditioning of the dog heart (Yao and Gross, 1993a), reportedly by stimulating muscarinic M2 receptors to couple to the Gi proteins (Yao and Gross, 1993b; 1994;). However, other studies have concluded that muscarinic M2 receptors do not have a role in IPC (Lawson et al., 1993; Liu and Downey, 1993). Other types of muscarinic receptors might be implicated in IPC, as evidenced by our recent work, which demonstrated that stimulation of the cardiac M3-mAChRs protected the heart from ischaemic insult similar to early preconditioning. This included diminishing the incidence and the severity of ischaemia-induced arrhythmias, limiting IS via activation of several survival signalling molecules, reducing apoptotic mediator levels and attenuating intracellular Ca2+ overload (Yang et al., 2005). This work also demonstrated that M3-mAChRs play a role in early preconditioning induced by aconitine or barium chloride (BaCl2) (Liu et al., 2008a,b;) However, these studies did not investigate whether activation of M3-mAChRs can induce delayed preconditioning, and this remains to be elucidated.

Thus, we designed the current study to determine the effects of stimulation of M3-mAChRs with choline 24 h before ischaemic injury, and to address the underlying mechanism.

Methods

Animals

Male Wistar rats weighing 220–260 g were used in this study. The animals were conditioned for 1 week at room temperature (23 ± 1°C), with a constant humidity (55 ± 5%), and had free access to food and tap water according to the GLP. The rats were handled in accordance with the guidelines of the Ethics Committee of Harbin Medical University, China. Wistar rats were provided by the Experimental Animal Center of Harbin Medical University.

Experimental design and rat model of myocardial I/R

Sixty Wistar rats were randomly distributed into five groups, with 12 rats per group. The five groups included: control (No ischaemia), ischaemia (MI), choline–ischaemia (Choline), methoctramine–choline–ischaemia (Meth) and 4-DAMP–choline–ischaemia (4-DAMP). Rats belonging to the ischaemia groups were subjected to 30 min occlusion of the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery, followed by 3 h of reperfusion. Choline (5 mg·kg−1, i.v.) was administered 24 h before I/R injuries. In the case of the methoctramine (10 µg·kg−1, i.v) and 4-DAMP (0.5 µg·kg−1, i.v.) groups, these two drugs were given 15 min before choline. The rats were anaesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (40 mg·kg−1, i.p.), and their respiration was controlled by a small ventilator. The standard limb lead II ECG was continuously recorded (BL 420, ChengDu TME Technology Co, Ltd, Chengdu, China) as described previously (Zhao et al., 2008). The surgical interventions used to create the I/R model were as previously described (Yang et al., 2005).

Measurement of ischaemia-induced arrhythmias

During the 30 min occlusion of the LAD, arrhythmias were measured according to the scoring system adapted from Curtis and Walker (1988), which assigns one score per animal based upon the most severe type of arrhythmia: 0, no arrhythmia; 1, ventricular premature beats (VPBs) and/or ventricular tachycardia (VT) of <10 s duration; 2, VPB and/or VT of 11–30 s; 3, VPB and/or VT of 31–90 s; 4, VPB and/or VT of 91–180 s, or reversible ventricular fibrillation (VF) of <10 s; 5, VPB and/or VT of >180 s, or reversible VF of >10 s; 6, irreversible VF. In all experiments, irreversible VF was the only cause of death. VPBs were defined as identifiable premature QRS complexes. VT was defined as a run of more than three consecutive VPBs, and VF was defined as a signal for which individual QRS deflections could not easily be distinguished from one another and for which a rate could no longer be assessed. The total number of VPBs, the duration of VT and the incidence of VF were also measured during the occlusion period.

Determination of IS

On completion of the 3 h of reperfusion, the animals were re-anaesthetized with sodium pentobarbital, and the coronary artery was re-occluded. Evans blue dye (1%) was administered via the left ventricle to measure the ischaemic myocardium [area at risk (AR)]. Then, the heart was excised, the right ventricle was removed and the left ventricle was cut into six thin cross-sectional pieces. These 2 mm slices were incubated in 4% triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) at 37°C in phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) for 15 min. Infarct area was identified as the TTC negative zone, and IS was expressed as a percentage of the AR, which was the non-blue region. AR was expressed as a percentage of the left ventricle. The AR and the area of infarction were measured by an image analyser, Image-Pro plus data Analysis Program (Media Cybernetics, Sliver Spring, MD, USA), as described previously (Sun et al., 2008).

Measurement of haemodynamic function

Haemodynamic function was assessed after 30 min of ischaemia by determining the mean arterial pressure (MAP), left ventricular systolic pressure and end diastolic pressure (LVEDP), and time derivatives of pressure were measured during contraction (+dP/dt) and relaxation (−dP/dt) recorded on a polygraph (BL 420, ChengDu TME Technology). Haemodynamic parameters were monitored throughout the experimental period.

Analysis of sarcolemmal connexin43 (Cx43) phosphorylation and total Cx43 expression

The non-ischaemic hearts and hearts that underwent 30 min ischaemia were excised, and the left ventricles were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. The membrane protein and total protein were prepared as described previously (Yue et al., 2006), and 50 µg of each sample was separated on 10% sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and electrotransferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). The membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk for 1 h at room temperature, and probed overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies of Cx43 (1:200 dilution, Zymed, San Francisco, CA, USA, for sarcolemmal Cx43; Santa Cruz Biotech Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA, for total Cx43), then washed with PBST for 10 min, three times. This was followed by 1 h incubation with secondary antibody at room temperature and washing, as above. The images were enhanced with the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (Li-Cor Bioscience, Lincoln, NE, USA), and the intensity of the bands was determined by Odyssey Software 3.0. The measurements of phosphorylated and dephosphorylataed Cx43 were expressed as a percentage of the total Cx43 content. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate-dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as an internal control.

Quantification of Hsp70, cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and iNOS expression

To determine the changes in total Hsp70, COX-2 and iNOS, rats (n= 16) from the Choline, Meth, 4-DAMP and the control group were re-anaesthetized 24 h later, and the hearts were then excised. Left ventricle samples were homogenized in RIPA lysis buffer containing 4% SDS and protease inhibitors, and then centrifuged at 18400×g for 30 min; the resulting supernatant was collected as total protein. For immunoblot assays, membranes were incubated with the Hsp70 (1:1000 dilution), COX-2 and iNOS primary antibodies, and the detection of was performed as described for Cx43. The immunoreactive bands were also analysed by normalizing with GAPDH.

Data analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical comparisons among multiple groups were performed by anova. If significant effects were indicated by anova, an unpaired t-test with F-test for equal variances was used to evaluate the significance of differences between individual means. Otherwise, the duration of the VT was compared by the Mann–Whitney test, and the incidence of VF was analysed by Fisher's exact test. A two-tailed P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Drugs and materials

The M3-mAChRs agonist, choline Cl, and antagonist, 4-DAMP (Alexander et al., 2008), as well as the muscarinic M2 receptor antagonist methoctramine were obtained from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA). Sodium pentobarbital, TTC and Evans blue were purchased from Shanghai Chemicals (Shanghai, China). GAPDH was obtained from Kangcheng (Shanghai, China).

The primary antibodies of Hsp70, Cx43, COX-2 and iNOS were obtained from Stress Gen Biotechnologies (Victoria, Canada) Zymed and Santa Cruz Biotech Inc., respectively. The secondary antibodies were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Results

Haemodynamics

Table 1 summarizes the haemodynamic parameters of all groups. Compared to the controls, occlusion of the LAD induced a significant decrease in MAP, ± dP/dt and an increase in LVEDP. There was no significant difference between the four surgical groups.

Table 1.

Haemodynamic changes during the coronary artery occlusion

| Group | HR | MAP | LVSP | LVEDP | dP/dt | −dP/dt |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (beats·min−1) | (mm Hg) | (mm Hg) | (mm Hg) | (mm Hg·s−1) | (mm Hg·s−1) | |

| Control | 429 ± 4 | 103.2 ± 2.7 | 119.5 ± 1.1 | −17.7 ± 2.4 | 5455 ± 600 | −5012 ± 408 |

| MI | 435 ± 10 | 84.5 ± 2.2* | 109.2 ± 4.3 | −5.0 ± 1.3* | 4626 ± 418 | −3676 ± 320* |

| Choline | 424 ± 5 | 86.5 ± 2.3* | 104.7 ± 3.5 | −7.5 ± 0.9* | 4887 ± 368 | −3389 ± 225* |

| Meth | 431 ± 7 | 85.1 ± 2.7* | 112.5 ± 3.5 | −5.2 ± 2.4* | 4278 ± 575 | −3609 ± 235* |

| 4-DAMP | 428 ± 3 | 88.2 ± 2.4* | 100.8 ± 2.6 | −6.2 ± 3.5* | 6026 ± 547 | −3950 ± 324* |

P < 0.05 versus Control.

Values are mean ± SEM, obtained from 12 rats.

HR, heart rate; LVSP, left ventricular systolic pressure; dP/dt, time derivatives of pressure.

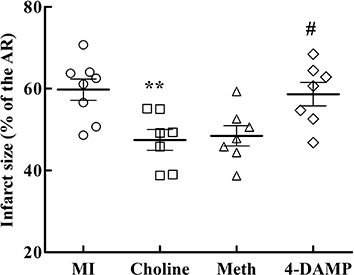

IS and AR

Figure 1 illustrates that the average IS (IS/AR) in the MI group was 59.7 ± 2.6, whereas in rats preconditioned with choline 24 h earlier the IS was significantly (P < 0.01) reduced (47.5 ± 2.5). This suggests that choline induced delayed preconditioning against myocardial infarction. Notably, the AR did not differ among the I/R groups (data not shown). Administration of methoctramine 15 min before exposure to choline did not compromise the preconditioning effect of choline. However, cardioprotection was lost in the presence of 4-DAMP (58.6 ± 2.9).

Figure 1.

Ischaemia-induced myocardial infarction. IS was expressed as a percentage of the AR. Values are mean ± SEM, obtained from seven to eight rats. **P < 0.01 versus MI; #P < 0.05 versus Choline.

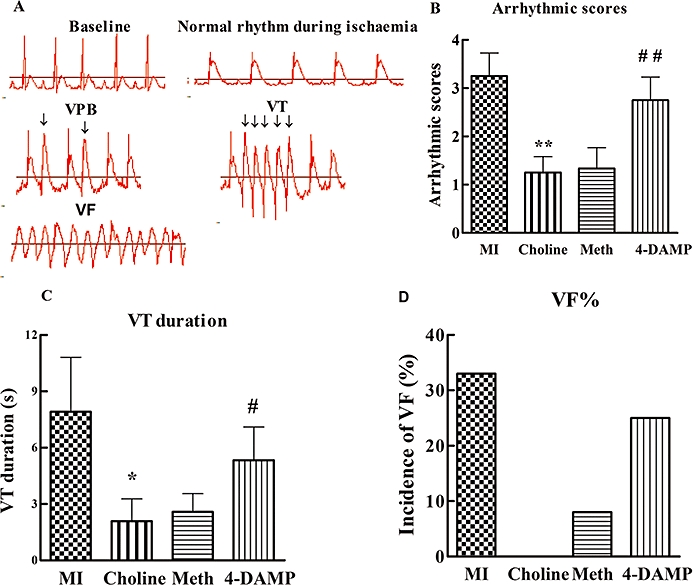

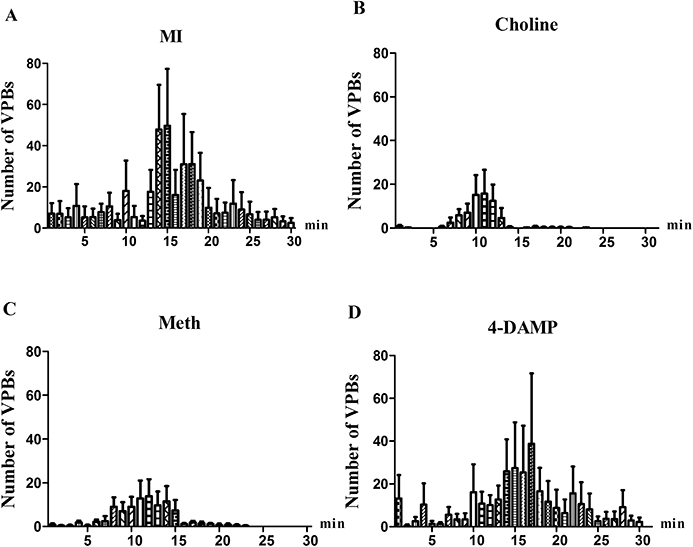

Ventricular arrhythmias and VPB distribution during the 30 min ischaemia period

These results are schematically presented in Figures 2 and 3. Compared to the MI group, preconditioning with choline markedly reduced the arrhythmia scores and the VT durations during the occlusion of the LAD. Interestingly, methoctramine infusion 15 min prior to the administration of choline followed by local ischaemia still significantly inhibited the ischaemia-induced arrhythmias. In contrast, pretreatment with 4-DAMP did not result in reduced arrhythmia scores and VT durations. The incidence of VF was attenuated in all groups; however, no significant difference existed compared to the MI group. Figure 3 shows the distribution of the VPBs and the 30 min myocardial ischaemia-induced abundant arrhythmias. The administration of choline noticeably decreased the total number of VPBs, especially those that occurred at around 15 min, and this beneficial effect was abrogated by pretreatment with 4-DAMP but not with methoctramine.

Figure 2.

Ventricular arrhythmias occurred during 30 min of occlusion of the LAD in all groups. (A) Examples of normal rhythm, VPBs, VT and VF as labelled. Compared to the MI group, in both the Choline and Meth groups, the arrhythmic scores (B), VT duration (C) and incidence of VF (D) were markedly decreased, while in the 4-DAMP group these measurements increased again. Values are mean ± SEM, n= 12. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus the MI group; ##P < 0.01, #P < 0.05 versus the Choline group.

Figure 3.

Distribution of VPBs. A 30 min period of myocardial ischaemia induced frequent arrhythmias, which presented a peak at around 15 min (A); administration of choline markedly decreased the total number of VPBs, especially the peak at around 15 min (B), and this beneficial effect was abolished by pretreatment with 4-DAMP (D), but not with methoctramine (C). Values are mean ± SEM, n= 12.

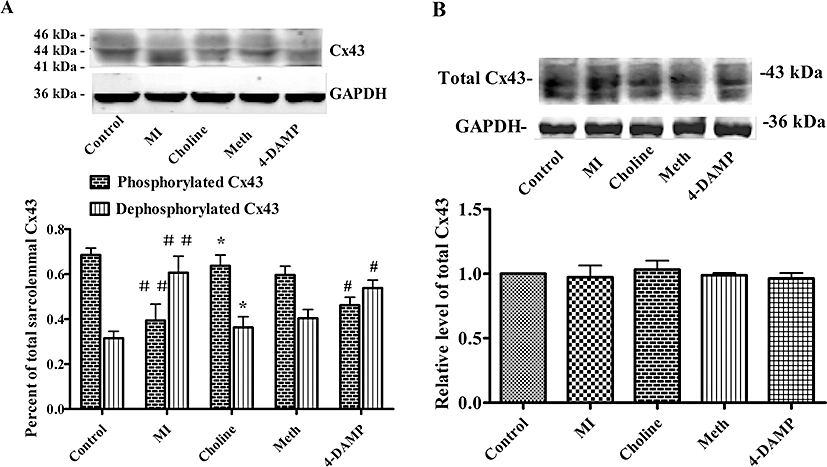

Changes in the sarcolemmal Cx43 phosphorylation status induced by 30 min occlusion of the LAD and the total Cx43 content

The results are presented in Figure 4. In heart samples taken from control rats, the predominant sarcolemmal Cx43 proteins are in the phosphorylated form (68%). However, we confirmed that in response to ischaemia, Cx43 underwent significant dephosphorylation causing the Cx43 phosphorylated form to fall to 39% (Figure 4A). The noticeable reduction of phosphorylated Cx43 was prevented by pretreatment with choline, and methoctramine had no effect on the benefits. In contrast, the phosphorylated form of Cx43 was reduced again (54%) in the presence of 4-DAMP. No significant change in total Cx43 content is apparent in any group (Figure 4B). Our analysis also shows that the total sarcolemmal Cx43 content in 4-DAMP group is a little lower than that in other groups.

Figure 4.

Changes in Cx43 determined after the 30 min occlusion of the LAD. (A) Top panel, representative Western blots for sarcolemmal Cx43 and GAPDH. Bottom panel, a histogram summarizing the Western blots expressed as a percentage of the total sarcolemmal Cx43 content. (B) Top panel, representative Western blots for total Cx43; bottom panel, histogram depicting the analysis of the total Cx43 content. Values are mean ± SEM, obtained from n= 4–5 samples in each group. ##P < 0.01 versus control group, *P < 0.05 versus MI, #P < 0.05 versus Choline.

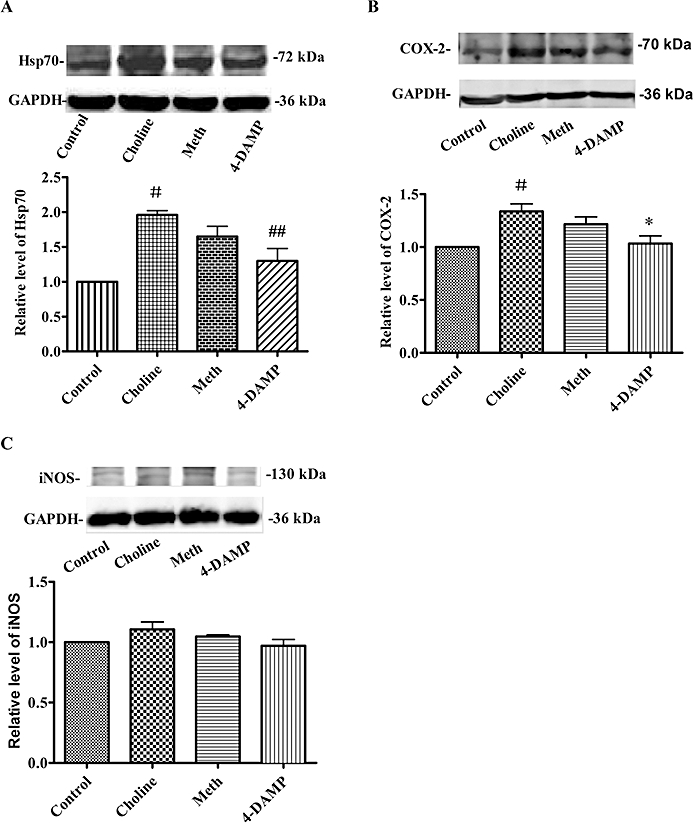

Effect of choline on Hsp70, COX-2 and iNOS expression

Representative Western blot analyses of Hsp70, COX-2 and iNOS are illustrated in Figure 5. The baseline level for the expression of Hsp70 (Figure 5A) and COX-2 (Figure 5B) was very low, and the administration of choline up-regulated their content. Pretreatment with 4-DAMP, but not methoctramine, prior to the administration of choline attenuated Hsp70 and COX-2 expression. Furthermore, there were no noticeable changes in the iNOS content (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Effect of choline treatment on Hsp70 (A), COX-2 (B) and iNOS (C) expression. Top panels, representative Western blot showing expression of Hsp70, COX-2 and iNOS 24 h following treatment in each group; bottom panels, histogram showing relative level of expression of each protein. Values are mean ± SEM, obtained from four samples per group. #P < 0.05 versus control, ##P < 0.01 versus Choline. *P < 0.05 versus Choline.

Discussion

The results from the present study demonstrate that the activation of M3-mAChRs with choline induces delayed preconditioning 24 h later, attenuates ischaemia-induced arrhythmias and reduces I/R-induced IS but has no effect on the haemodynamics. The results also show that activation of M3-mAChRs restores ischaemia-induced reduction of phosphorylated sarcolemmal Cx43, and up-regulates COX-2 expression levels, which might contribute to the beneficial effects.

The current understanding of the cardiac mAChRs involves the coexistence of multiple subtypes, no longer simply the ‘single M2-mAChRs’ theory. In fact, M3-mAChRs are documented to play an important role in both physiology and pathophysiology (Wang et al., 2004). Previous studies have demonstrated the cytoprotective effects of choline-stimulated M3-mAChRs against ischaemic injuries, which were probably achieved by increasing the activities of anti-apoptotic mediators Bcl-2, extracellular signal-regulated kinases and superoxide dismutase, and decreasing the pro-apoptotic mediators Fas and p38 (Yang et al., 2005). Similar beneficial effects have been confirmed in several non-cardiac cells (Budd et al., 2003; De Sarno et al., 2003; Tobin and Budd, 2003). Our recent study found that M3-mAChRs seemed to play an important role in the pharmacological preconditioning induced by aconitine or BaCl2 in rats (Liu et al., 2008a). Nevertheless, all these studies focused on the acute beneficial effects related to early preconditioning. In this study, ischaemic insults were applied 24 h after the activation of M3-mAChRs, and we found for the first time that it continued to protect the heart from I/R injury, resulting in significant reduction of the IS. COX-2 and iNOS proteins have been well characterized as mediators of the late preconditioning, and our data demonstrated a significant induction of COX-2, but iNOS was unchanged by choline. It is therefore conceivable that the infarct-limiting effect of M3-mAChRs can be ascribed to the up-regulation of COX-2 expression.

It has been documented in numerous studies that Hsp70 protects cardiomyocytes against irreversible insults (Suzuki et al., 2000; Tupling et al., 2008). Based on these studies, it seems likely that the up-regulation of Hsp70 induced by choline confers the infarct-limiting effect observed in this study. However, other studies have demonstrated that the induction of Hsp70 is just an indicator of the stressed cardiomyocytes, and might not be responsible for any beneficial effects (Qian et al., 1999; Bolli, 2000). Therefore, further studies are needed to clarify this issue.

Two hemichannels composed of connexins form gap junctions, which mediate the direct communication and ensure cellular electrical coupling between adjacent cardiomyocytes. In mammalian heart, the predominant connexin is Cx43 (Tribulova et al., 2008). It is well documented that early ischaemia-induced arrhythmias (during the first 30 min) are classified into phase Ia and phase Ib. The Ia arrhythmias occur between 3 and 8 min after the onset of ischaemia, and are due to the rapid changes in the electrical properties of the membrane. On the other hand, Ib arrhythmias occur at around 15 min of ischaemia and are considered to be associated with the cellular electrical uncoupling (Cascio et al., 2005; Papp et al., 2007; Hagen et al., 2009). There is much evidence to suggest that a variety of circumstances, including dephosphorylation of Cx43, act to trigger the onset of cellular electrical uncoupling during cardiac ischaemia (Kleber et al., 1987; Smith et al., 1995; Beardslee et al., 2000; Schulz and Heusch, 2006). In non-ischaemic hearts, most of the sarcolemmal Cx43 is phosphorylated (Figure 4A) (bands at 44–46 kDa), which enables cell-to-cell electrical coupling. In response to ischaemic stimulation, the fraction of phosphorylated Cx43 sharply decreased, and the dephosphorylated Cx43 (41 kDa) accumulated, resulting in electrical uncoupling, and this contributed to an increased occurrence of Ib arrhythmias (Cascio et al., 2005; Papp et al., 2007). Although different phosphorylation sites of Cx43 result in opposite effects on gap junction conductance (Lampe et al., 2000; Solan et al., 2007), previous studies have demonstrated that the phosphorylated status of Cx43, as detected by a rabbit polyclonal antibody (Zymed), was found to coincide with the tissue resistance changes (Beardslee et al., 2000; Papp et al., 2007). Activation of M3-mAChRs preserved the phosphorylated level of sarcolemmal Cx43. This maintained the cellular electrical coupling, which might be responsible for the reduction of arrhythmias occurring in the 30 min period of occlusion of the LAD. IPC has been reported to delay the dephosphorylation of Cx43, and postpone ischaemia-induced electrical uncoupling (Lascano and Negroni, 2007), which delayed or suppressed the occurrence of Ib arrhythmias (Cinca et al., 1997; Papp et al., 2007), and our data show a suppression of Ib arrhythmias. Our previous study indicated that the M3-mAChRs are co-located with Cx43 on the membrane of ventricular cardiomyocytes in rats (Yue et al., 2006). Thus, we speculate that this might be the structural foundation for the observed beneficial effects, although the exact mechanism is unclear. Recently, it was reported that activation of M3-mAChRs down-regulated aconitine or ouabain-induced Ca2+ overload (Liu et al., 2008a,b;), indicating that M3-mAChRs mediate multiple pathways that lead to anti-arrhythmic effects. As to the decreased total sarcolemmal Cx43 in the 4-DAMP group, because administration of 4-DAMP alone without ischaemia did not have this effect and did not produce arrhythmias (data not shown), we presume that 4-DAMP might affect the redistribution of Cx43 during ischaemia.

In addition, the results from the present study confirm that activation of the M3-mAChRs produces slightly negative inotropic and chronotropic effects (Liu et al., 2001), but it is reasonable to assume that activation of M3-mAChRs does not produce transient global ischaemia, which might trigger the delayed cardioprotective effects.

It should be noted that no subtype-specific agonists and antagonists for mAChRs are currently available, but choline and 4-DAMP have been demonstrated to be more selective for M3-mAChRs than for other subtypes, and are used widely. The M2-mAChR is the dominant muscarinic receptor type in mammalian heart. Consequently, the present study was conducted using the M2-mAChR antagonist methoctramine to determine whether the protective effects of choline are mediated by stimulation of M2-mAChRs. Our data show that all the benefits of choline were abolished by 4-DAMP, but not by methoctramine.

In summary, our experiments indicate that activation of M3-mAChRs 24 h before an ischaemic insult induces delayed preconditioning in rats. This preserves the phosphorylated Cx43, which might contribute to the anti-arrhythmic effect, and reduces the I/R-induced IS possibly by up-regulating the expression of COX-2. However, the potential therapeutic benefits of the M3-mAChRs as a cardioprotective target need further investigation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (30672462), the Specialized Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education (20050226010) and the Special Foundation for Key Research Project of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University, China (ZD2008-06).

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- COX-2

cyclooxygenase-2

- Cx43

connexin43

- 4-DAMP

4-diphenylacetoxy-N-methylpiperidine methiodide

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- IPC

ischaemic preconditioning

- M3-mAChRs

M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors

- VF

ventricular fibrillation

- VPB

ventricular premature beat

- VT

ventricular tachycardia

Conflict of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Alexander SP, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to Receptors and Channels (GRAC), 3rd edition. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153(Suppl. 2):S1–209. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beardslee MA, Lerner DL, Tadros PN, Laing JG, Beyer EC, Yamada KA, et al. Dephosphorylation and intracellular redistribution of ventricular connexin43 during electrical uncoupling induced by ischemia. Circ Res. 2000;87:656–662. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.8.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolli R. The late phase of preconditioning. Circ Res. 2000;87:972–983. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.11.972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd DC, McDonald J, Emsley N, Cain K, Tobin AB. The C-terminal tail of the M3-muscarinic receptor possesses anti-apoptotic properties. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:19565–19573. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211670200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cascio WE, Yang H, Muller-Borer BJ, Johnson TA. Ischemia-induced arrhythmia: the role of connexins, gap junctions, and attendant changes in impulse propagation. J Electrocardiol. 2005;38(4) Suppl.:55–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2005.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cinca J, Warren M, Carreno A, Tresanchez M, Armadans L, Gomez P, et al. Changes in myocardial electrical impedance induced by coronary artery occlusion in pigs with and without preconditioning: correlation with local ST-segment potential and ventricular arrhythmias. Circulation. 1997;96:3079–3086. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.9.3079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen G, Shirai T, Weisel RD, Rao V, Merante F, Tumiati LC, et al. Optimal myocardial preconditioning in a human model of ischemia and reperfusion. Circulation. 1998;98(19) Suppl.:II184–II194. discussion II194–II186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis MJ, Walker MJ. Quantification of arrhythmias using scoring systems: an examination of seven scores in an in vivo model of regional myocardial ischaemia. Cardiovasc Res. 1988;22:656–665. doi: 10.1093/cvr/22.9.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das M, Das DK. Molecular mechanism of preconditioning. IUBMB Life. 2008;60:199–203. doi: 10.1002/iub.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Sarno P, Shestopal SA, King TD, Zmijewska A, Song L, Jope RS. Muscarinic receptor activation protects cells from apoptotic effects of DNA damage, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial inhibition. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:11086–11093. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212157200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen A, Fisman EZ, Rubenfire M, Freimark D, McKechnie R, Tenenbaum A, et al. Ischemic preconditioning: nearly two decades of research. A comprehensive review. Atherosclerosis. 2004;172:201–210. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9150(03)00238-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S, Standen NB, Galinanes M. Preconditioning the human myocardium by simulated ischemia: studies on the early and delayed protection. Cardiovasc Res. 2000;45:339–350. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00353-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagen A, Dietze A, Dhein S. Human cardiac gap junction coupling: effects of antiarrhythmic peptide AAP10. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;83:405–415. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikonomidis JS, Tumiati LC, Weisel RD, Mickle DA, Li RK. Preconditioning human ventricular cardiomyocytes with brief periods of simulated ischaemia. Cardiovasc Res. 1994;28:1285–1291. doi: 10.1093/cvr/28.8.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaszala K, Vegh A, Papp JG, Parratt JR. Time course of the protection against ischaemia and reperfusion-induced ventricular arrhythmias resulting from brief periods of cardiac pacing. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1996;28:2085–2095. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1996.0201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleber AG, Riegger CB, Janse MJ. Electrical uncoupling and increase of extracellular resistance after induction of ischemia in isolated, arterially perfused rabbit papillary muscle. Circ Res. 1987;61:271–279. doi: 10.1161/01.res.61.2.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambiase PD, Edwards RJ, Cusack MR, Bucknall CA, Redwood SR, Marber MS. Exercise-induced ischemia initiates the second window of protection in humans independent of collateral recruitment. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:1174–1182. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00055-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampe PD, TenBroek EM, Burt JM, Kurata WE, Johnson RG, Lau AF. Phosphorylation of connexin43 on serine368 by protein kinase C regulates gap junctional communication. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:1503–1512. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.7.1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lascano EC, Negroni JA. Gap junctions in preconditioning against arrhythmias. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;74:341–342. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson CS, Coltart DJ, Hearse DJ. The antiarrhythmic action of ischaemic preconditioning in rat hearts does not involve functional Gi proteins. Cardiovasc Res. 1993;27:681–687. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.4.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Downey JM. Preconditioning against infarction in the rat heart does not involve a pertussis toxin sensitive G protein. Cardiovasc Res. 1993;27:608–611. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.4.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Wang Y, Ma ML, Zhang Y, Li HW, Chen QW, et al. Cardiac-hemodynamic effects of M3 receptor agonist on rat and rabbit hearts. Yao Xue Xue Bao. 2001;36:84–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Du J, Gao Y, Zhang Y, Cai BZ, Zhao H, et al. Role of M(3) receptor in aconitine/barium-chloride-induced preconditioning against arrhythmias in rats. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2008a;373:511–515. doi: 10.1007/s00210-008-0376-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Sun HL, Li DL, Wang LY, Gao Y, Wang YP, et al. Choline produces antiarrhythmic actions in animal models by cardiac M3 receptors: improvement of intracellular Ca2+ handling as a common mechanism. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2008b;86:860–865. doi: 10.1139/Y08-094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lott FD, Guo P, Toombs CF. Reduction in infarct size by ischemic preconditioning persists in a chronic rat model of myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury. Pharmacology. 1996;52:113–118. doi: 10.1159/000139374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murry CE, Jennings RB, Reimer KA. Preconditioning with ischaemia: a delay of lethal cell injury in ischemic myocardium. Circulation. 1986;74:1124–1136. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.74.5.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagliaro P, Gattullo D, Rastaldo R, Losano G. Ischemic preconditioning: from the first to the second window of protection. Life Sci. 2001;69:1–15. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(01)01113-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papp R, Gonczi M, Kovacs M, Seprenyi G, Vegh A. Gap junctional uncoupling plays a trigger role in the antiarrhythmic effect of ischaemic preconditioning. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;74:396–405. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian YZ, Bernardo NL, Nayeem MA, Chelliah J, Kukreja RC. Induction of 72-kDa heat shock protein does not produce second window of ischemic preconditioning in rat heart. Am J Physiol. 1999;276(1):H224–234. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.1.H224. Pt 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Heusch G. Connexin43 and ischemic preconditioning. Adv Cardiol. 2006;42:213–227. doi: 10.1159/000092571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiki K, Hearse DJ. Preconditioning of ischemic myocardium: reperfusion-induced arrhythmias. Am J Physiol. 1987;253(6):H1470–1476. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1987.253.6.H1470. Pt 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith WTt, Fleet WF, Johnson TA, Engle CL, Cascio WE. The Ib phase of ventricular arrhythmias in ischemic in situ porcine heart is related to changes in cell-to-cell electrical coupling. Experimental Cardiology Group, University of North Carolina. Circulation. 1995;92:3051–3060. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.10.3051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solan JL, Marquez-Rosado L, Sorgen PL, Thornton PJ, Gafken PR, Lampe PD. Phosphorylation at S365 is a gatekeeper event that changes the structure of Cx43 and prevents down-regulation by PKC. J Cell Biol. 2007;179:1301–1309. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200707060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Du J, Zhang G, Zhang Y, Pan G, Wang L, et al. Aberration of L-type calcium channel in cardiac myocytes is one of the mechanisms of arrhythmia induced by cerebral ischemia. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2008;22:147–156. doi: 10.1159/000149792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki K, Sawa Y, Kagisaki K, Taketani S, Ichikawa H, Kaneda Y, et al. Reduction in myocardial apoptosis associated with overexpression of heat shock protein 70. Basic Res Cardiol. 2000;95:397–403. doi: 10.1007/s003950070039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano H, Tang XL, Kodani E, Bolli R. Late preconditioning enhances recovery of myocardial function after infarction in conscious rabbits. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279:H2372–2381. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.5.H2372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton JD, Liu GS, Downey JM. Pretreatment with pertussis toxin blocks the protective effects of preconditioning: evidence for a G-protein mechanism. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1993;25:311–320. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1993.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobin AB, Budd DC. The anti-apoptotic response of the Gq/11-coupled muscarinic receptor family. Biochem Soc Trans. 2003;31(6):1182–1185. doi: 10.1042/bst0311182. Pt. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tribulova N, Knezl V, Okruhlicova L, Slezak J. Myocardial gap junctions: targets for novel approaches in the prevention of life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias. Physiol Res. 2008;57(Suppl. 2):S1–S13. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.931546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tupling AR, Bombardier E, Vigna C, Quadrilatero J, Fu M. Interaction between Hsp70 and the SR Ca2+ pump: a potential mechanism for cytoprotection in heart and skeletal muscle. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2008;33:1023–1032. doi: 10.1139/H08-067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Shi H, Wang H. Functional M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in mammalian hearts. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;142:395–408. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi F, Nasa Y, Yabe K, Ohba S, Hashizume Y, Ohaku H, et al. Activation of cardiac muscarinic receptor and ischemic preconditioning effects in in situ rat heart. Heart Vessels. 1997;12:74–83. doi: 10.1007/BF02820870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B, Lin H, Xu C, Liu Y, Wang H, Han H, et al. Choline produces cytoprotective effects against ischemic myocardial injuries: evidence for the role of cardiac M3 subtype muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2005;16:163–174. doi: 10.1159/000089842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Z, Gross GJ. Acetylcholine mimics ischemic preconditioning via a glibenclamide-sensitive mechanism in dogs. Am J Physiol. 1993a;264(6):H2221–H2225. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.264.6.H2221. Pt 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Z, Gross GJ. Role of nitric oxide, muscarinic receptors, and the ATP-sensitive K+ channel in mediating the effects of acetylcholine to mimic preconditioning in dogs. Circ Res. 1993b;73:1193–1201. doi: 10.1161/01.res.73.6.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Z, Gross GJ. The ATP-dependent potassium channel: an endogenous cardioprotective mechanism. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1994;24(Suppl. 4):S28–S34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yellon DM, Alkhulaifi AM, Pugsley WB. Preconditioning the human myocardium. Lancet. 1993;342:276–277. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91819-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue P, Zhang Y, Du Z, Xiao J, Pan Z, Wang N, et al. Ischemia impairs the association between connexin 43 and M3 subtype of acetylcholine muscarinic receptor (M3-mAChR) in ventricular myocytes. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2006;17:129–136. doi: 10.1159/000092074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao XY, Li GY, Liu Y, Chai LM, Chen JX, Zhang Y, et al. Resveratrol protects against arsenic trioxide-induced cardiotoxicity in vitro and in vivo. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154:105–113. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]