Abstract

Filopodia, or the growth of bundles of biological fibers outwards from a biological cell surface while enclosed in a membrane tube, are implicated in many processes vital to life. This study models the effect of capping protein on such filopodia, paying close attention to the polymerization dynamics of biological fiber bundles within long membrane tubes. Due to the effects of capping protein, the number of fibers in the filopodium bundle decreases down the length of the enclosing membrane tube. This decrease in the number of fibers down the length of a growing filopodium is found to have profound implications for the dynamics and stability of filopodia in general. This study theoretically finds that the presence of even a relatively modest amount of capping protein can have a large effect on the growth of typical filopodia, such as can be found in fibroblasts, keratocytes, and neuronal growth cones. As an illustration of this modeling work, this study investigates the striking example of the acrosomal reaction in the sea cucumber Thyone, whose filopodia can grow remarkably quickly to ∼90 μm in ∼10 s, and where the number of fibers is known to decrease down the length of the filopodium, presumably due to progressive fiber end-capping occurring as the filopodium grows. Realistic future dynamical theories for filopodium growth are likely to rely on an accurate treatment of the kinds of capping protein effects analyzed in this work.

Introduction

One of the main important characteristics of life is locomotion, with cell migration being vital to many life processes, and diseases including cancer metastasis for example (1–3). Accordingly, there has been much recent interest in the formation and growth of long, thin cellular protrusions due to the polymerization of bundles of fibers including actin (4–7). Such structures appear on cell membranes as typical filopodia (1,4), but can also appear on neural growth cones (8), as well as in the acrosomal reaction of the sea cucumber Thyone (9–14).

Although the dynamical theory of actin polymerization in filopodia is now fairly well understood (15–17), the role of capping protein in such processes is much less so (18–27). Capping protein typically binds to the barbed ends of actin filaments and prevents both depolymerization and the addition of new monomers. Examples of actin capping protein include β-actinin, CapZ in skeletal muscle, and Cap32/34 in Dictyostelium (18,19).

Filopodia occur in a wide variety of biological contexts, with different capping strategies present in different organisms (4,5,8,9). In the filopodia of motile cells such as fibroblasts or keratocytes, for example (4,5), end-capping of filaments is typically suppressed due to the presence of additional proteins such as VASP (28,29). In this case, the number of fibers at the growing end of the filopodium is typically equal to the number of initial fibers at its base. However, for filopodia involved in the striking example of the acrosomal reaction in the sea cucumber Thyone (9) (whose filopodia can grow to ∼90 μm in ∼10 s), it is known that the number of fibers decreases down the length of the filopodium from ∼200 near its base to ∼10 near the tip (9). This decrease in the actin fiber bundle radius down the filopodium in Thyone is thought to be due to progressive fiber end-capping as the filopodium grows (9,10,12), and presumably (12) contributes to the extraordinarily fast rate of filopodial growth that is typically observed.

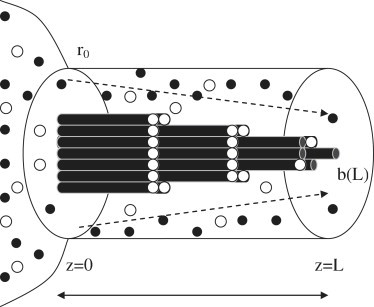

The purpose of this work, as presented here, is to theoretically investigate the role of capping protein on the polymerization kinetics of biological fibers such as actin, within long membrane tubes such as microspikes, filopodia, or spicules (see Fig. 1). This study finds that due to the effects of capping protein dynamics, the number of fibers in the filopodium bundle (and hence the fiber bundle diameter) is able to decrease as the filopodium grows, within an enclosing membrane tube. This decrease in the number of fibers down the length of a growing bundle, as is known to occur in Thyone (9), can have profound implications for filopodium dynamics and stability. It is also found that the presence of even relatively modest amounts of capping protein can have a large effect on the growth of more-typical filopodia, such as that which can be found in fibroblasts, keratocytes, and neuronal growth cones.

Figure 1.

Diagram showing a growing filopodium which becomes progressively capped. A flux (dashed arrows) of actin monomers (solid circles) and capping protein (open circles) from a reservoir concentration of ρa(0) and ρc(0), respectively, at the base of a fiber bundle (z = 0) feeds the growing bundle of nuc uncapped fiber ends (at z = L), within an enclosing membrane tube of radius r0. The diameter of the fiber bundle can be seen to decrease down the length of the growing filopodium as a direct consequence of fiber end-capping due to the presence of capping protein.

This article does not consider the formation or origin of filopodia (or that of lamellipodia, as for example in (6,7)). Instead, in this approach, the filopodium is assumed to already have been initiated, and to have already begun the growing and maturation stage of its development.

Theory

To successfully model the growing filopodia, actin polymerization, capping protein dynamics, and the elasticity of the enclosing membrane tube will need to be taken into account. Similar theoretical methods to those considered here, without the presence of fiber end-capping, have been successfully deployed in previous work (15,17) on modeling long, thin, cellular protrusions. Throughout this study, it will be assumed that any growth of the fiber and tube is quasistatically low. This quasiequilibrium regime is applicable under most physiological and in vivo conditions (1,3). This study therefore ignores any dynamical instabilities (pearling, for instance) that can occur on membrane tubes (30,31). A cell membrane reservoir is assumed to be present that can provide membrane material at a rate sufficient for the growing filopod until its membrane supply becomes exhausted. Note that this fiber bundle can only elongate via addition of monomers to the end furthest from its base, as is typically the case for biological filopodia (1,4). This article will now go on to give a more detailed account of the model used.

Actin polymerization dynamics

Actin monomer transport

This study assumes axial symmetry for the cylindrical membranes, allowing the treatment of the local concentration of actin monomers ρa as being dependent on displacement down the tube alone. Given that this study works in the slow, quasiequilibrium regime throughout, with steady growth of the polymerizing fiber, it can be approximated that the actin monomer flux Ja is constant, and given by

| (1) |

The first term on the left-hand side of Eq. 1 describes the contribution to the flux due to actin monomer diffusion, with an associated diffusion constant Da. The second contribution to Ja in Eq. 1 arises due to the advection of actin monomers down the growing membrane tube by the flow of the cytoplasmic fluid (or water) present. Note that in this case, the velocity v is driven entirely by fiber polymerization (i.e., if there is no polymerization, then there is no net flow of cytoplasmic fluid within the membrane tube).

In addition, the boundary condition at the growing fiber tip is needed (15),

| (2) |

where v is the speed of polymerization, δa is the size of a single actin monomer, and nuc is the number of uncapped fibers in the growing bundle. The drift part of the flux is not included in Eq. 2, because the fiber tip and the cytoplasmic fluid are co-moving (15). Included in Eq. 2, however, is the increase of the effective cylindrical area for actin delivery as the bundle of fibers (designated as b) decreases below the membrane tube radius (r0). This effect will typically act to speed up the fiber polymerization dynamics given by v, as b becomes ≪r0, as seen below. It is additionally required that at the other end of the membrane, a reservoir of actin monomers be available that acts to buffer the actin concentration at z = 0, such that ρa(z)|z=0 = ρa(0) = constant.

Given Eqs. 1 and 2, one can then solve for ρa, and find in the quasistatic approximation

| (3) |

Brownian ratchet dynamics for polymerizing actin bundles

The Brownian ratchet mechanism (32–35) has become paradigmatic for describing the polymerization dynamics of many different biological polymers. In this approach, the speed of actin polymerization is given by

| (4) |

where is the rate of actin monomer addition and koff is the rate of actin monomer subtraction. In the quasistatic regime, one can calculate the density at the tip ρa(L) from Eq. 3, and find in the quasiequilibrium limit that the speed of polymerization is consistently given by

| (5) |

Equation 5 shows that for large L it follows that , which leads to the intermediate timescaling behavior for a polymerizing fiber within a membrane tube, in the quasistatic regime, of L ∼ t1/2. This type of behavior is consistent with diffusion-limited growth (2,15), and merely reflects the underlying physical crossover from reaction-limited to diffusion-limited growth, as L(t) increases.

Capping protein dynamics

Capping protein transport

The delivery of capping protein to the ends of a growing fiber bundle follows in an analogous fashion to the example already given for actin monomer transport. The concentration of capping protein ρc is assumed to be dependent on displacement down the tube alone. In addition, given that this study works throughout in the quasiequilibrium regime, the capping protein flux Jc can be approximated as being constant, and it is given by

| (6) |

Equation 6 contains the contribution to the capping protein flux due to diffusion, with an associated diffusion constant Dc, as well as that due to advection. For the capping protein, the boundary condition at the growing fiber tip is also needed,

| (7) |

where nc is the number of capped fibers in the growing bundle. The drift part of the flux is again not included in Eq. 7, because the fiber tip and the cytoplasmic fluid are co-moving (15). This study also requires that at the nongrowing base end of the membrane tube, a reservoir of capping protein be available, such that at z = 0, ρc(z)|z=0 = ρc(0) = constant.

Given Eqs. 6 and 7, one can then solve for ρc, and find in the quasistatic approximation that

| (8) |

Capping dynamics

To describe the capping protein dynamics (18–27), a capping rate equation that caps uncapped fibers at a rate and depends on the concentration of capping protein ρc(L) and the number of uncapped fibers nuc is needed. An uncapping rate is also needed, which depends on the number of capped fibers nc. In complete analogy with the Brownian ratchet dynamics for actin polymerization given above, one is therefore led to the expression for capping protein dynamics,

| (9) |

where the Arrhenius term exp(−fδc/nuc) means that to add capping protein to the ends of growing fibers, work must be carried out against the local membrane force f a distance δc (the typical size of a capping protein monomer). In the quasistatic regime, one can calculate the density at the tip ρc(L) from Eq. 8, and find in the quasiequilibrium limit that the capping rate of uncapped fibers nuc is consistently given by

| (10) |

where n0 = nuc + nc is the total number of capped and uncapped fibers, which is taken to be a fixed constant such that the boundary condition nuc(t)|t=0 = n0 applies.

Fiber bundle radial size

Actin fibers in filopodia typically bundle together tightly to form a parallel fiber bundle, connected often by bundling proteins such as fascin (1). To estimate the radial size b(L) of a bundle of uncapped fibers at the growing end, this study looks at a cross section of nuc fibers, which are assumed, for generality, to be a hexagonally close-packed structure. Using such a construction, one can quantitatively estimate the bundle radius b(L) as a function of the number of fibers nuc as

which approximates to

Such fiber construction geometry is only strictly valid for certain special packing values of nuc, corresponding to a completed hexagonally close-packed fiber arrangement. However, for the purposes of this study, it is approximately assumed that the fiber bundle radius b(L) varies continuously with nuc, which remains valid in an average or mean-field sense.

For typical biological filopodia in vivo, the gap size between the membrane radius (r0) and the fiber bundle radius (b) is usually greater than the monomer size (δ). However, in the acrosomal reaction of Thyone (9), it is typically found that r0 ∼ b—which can have a big effect on slowing down the early time dynamics of Thyone filopodia, as seen in more detail below.

Membrane force on a growing bundle

Membrane tube elasticity

To describe the cylindrical membrane, this study uses the Hamiltonian Hm for membrane elasticity (36,37) (this study works throughout in units where kBT = 1),

| (11) |

which contains surface tension (σ), and rigidity (κm) controlled terms. In deriving Eq. 11, this study has assumed that the membrane tube radius r is axisymmetric (∂ϕr/r ≪ 1), and varies slowly along the length of the tube (∂zr ≪ 1). This approximation can be shown to hold consistently in the quasistatic regime. This study has also included in Hm an axial membrane force term, f, which arises from the polymerizing fiber, and controls the axial length, L, of the membrane tube. In what follows, any effects that could arise from leaflet asymmetry or spontaneous curvature are neglected.

Minimizing Eq. 11 with regard to r, one obtains

and

such that the force is independent of length. Therefore, to describe the possible end states of filopodium growth due to stalling or buckling, the effects of membrane stretching need to be taken into account.

Depletion of membrane reservoir and membrane stretching

The force f0 derived above assumes that there is enough membrane available to buffer the surface tension, such that σ remains effectively constant over the fiber's growth (38,39). For long, growing filopodia, this may not always be the case, as the supply of membrane to the base of growing filopodia can often be highly regulated in real biological cells (1). If it so occurs that a growing filopod begins to run out of membrane material as it becomes longer and longer, then it will start to feel a concomitant membrane stretching force (38,39). This membrane stretching force fS, once membrane stretching becomes appreciable for long filopodia, will typically be much larger than the value of f0 determined above—and for this study's purposes, it is calculated as follows.

This study introduces the following additional membrane Hamiltonian, HS (36), which energetically penalizes any stretching of the membrane area from its nominal value A = 2πLr,

| (12) |

where KS is the membrane stretching modulus, and A0 is the total amount of area available to a growing filopod from an assumed membrane reservoir. For example, if a growing filopod is thought of as being attached at its base to a spherical membrane reservoir of radius R0, then A0 is simply given by 4πR02.

To obtain the membrane stretching force, the corresponding (normalized) partition function is formed by integrating over all values of the membrane area A, up to the maximum allowed value of A0, weighted by the Boltzmann factor exp(−HS) as

| (13) |

where in the second line of Eq. 13 it is assumed that , and erf(x) is the usual error function. The membrane stretching force fS as a function of filopod length L, is then simply given by minimization of the logarithm of 𝒵 with regard to L, evaluated at r = r0:

| (14) |

The value fS derived in Eq. 14 conforms to my intuition as to how the membrane stretching force should behave as the filopod length L increases. That is, for small filopod lengths , when there is plenty of membrane material available, the membrane stretching force must be negligible: fS ≃ 0. As the filopod grows, more and more membrane gets used up in feeding this growth, and the membrane stretching force begins to slowly increase. Finally, when all the free available membrane in the reservoir gets used up, the force due to membrane stretching fS increases markedly, and crosses over to the large filopod length limit, when , of .

This study thus finds that the total membrane force, f, exerted on a growing fiber tip can now be expressed as f = f0 + fS with the more familiar membrane elastic force, f0, as given above. It is this total membrane force, f, which is required when considering fiber polymerization and capping protein dynamics. Note that one could also have added to f a term describing a possible frictional force between the cytoskeleton and the membrane: f ≃ ξv (40). Given typical values of ξ, however, it can easily be checked (using, e.g., (40)), such that for this case (in the quasistatic limit) one can safely ignore the effects of friction between any cytoskeleton and membrane present.

Actin fiber bundle stalling

The dynamics of a growing actin fiber bundle, as found in Brownian ratchets (17,32–34), is governed by the rate of actin monomer addition, ρa(L) exp(−fδa/nuc), and the rate of actin monomer subtraction, . Note that it is typically assumed that the rate of actin addition to the ends of growing fibers depends on the concentration of locally available monomers, ρa(L), whereas the rate of monomer subtraction does not. In the presence of a local force, f, acting on the growing rod tip, and via elementary Kramers transition rate theory (32,33), it can be shown that the rate constant of actin addition contains the factor exp(−fδa/nuc), which represents the work required to add monomers of size δa to a growing bundle of nuc fibers against the membrane force f. Note that it is usually assumed (32,33) that only the rate of actin monomer addition is modified under the action of the local force, whereas the rate of actin monomer subtraction remains unaffected (32,33). Via elementary thermodynamical arguments (32,33), it is straightforward to see that rod growth stalls when the (force-dependent) rate of monomer addition equals the rate of monomer subtraction, implying, from Eq. 5, the result—fstall = (nuc/δa) ln(ρa(0)/). This result for the stall force fstall expresses the simple idea that rod growth stalls when the energy gain (or loss of entropy), produced by adding actin monomers to the growing tip, exactly balances the corresponding energy cost of doing the required work against the membrane.

For the filopodia considered in this work, there are two possible pathways for actin fiber bundles to stall. If there is sufficient membrane material present, then it can be seen from above that the membrane force f is independent of the fiber bundle length L, such that f ∼ f0. In this case, the condition for stalling of filopodium growth is met when the number of uncapped fibers nuc reaches a critical minimum value. Alternatively, if the membrane reservoir at the base of the filopodium becomes exhausted, then the membrane force f increases rapidly such that now f ∼ fS, and the membrane force is large enough to stall fiber growth on its own.

Fiber bundle buckling

In the classical treatment, given by Euler buckling (41), a bundle of fibers of length l, and persistence length lp, under the action of a membrane force f, should undergo a buckling transition when the relation first becomes satisfied. This naive argument would seem to suggest an upper limit to the size of filopodia of ∼10 μm, with the fiber bundle inevitably collapsing once the Euler buckling threshold force is reached (fbuckle ∼10 pN). Even accounting for the presence of tight bundling in actin filopodia (due to the presence of fascin, for example) via a quadratic increase of bundle stiffness (lp) with the number of fibers (n) such that lp ∼ n2, it is difficult to explain the physiological observation of filopodia over 10–20 μm in length (15). As an extreme case, it is well known, for example, that filopodia involved in the acrosomal reaction of Thyone can grow to as large as ∼90 μm (9).

In an interesting article (42), this difficulty in explaining the apparent stability of long filopodia has recently been addressed. Pronk et al. (42) provide some simple arguments against the validity of the classical view of Euler buckling when applied to growing filopodia. Firstly, they point out that, for narrow filopodia, the membrane itself will deform in line with that of the bending filament, such that the compressive membrane force will tend to act along the fibers contour, and not its end-to-end distance (42). Secondly, the presence of an enclosing membrane will naturally tend to stabilize a fiber bundle against buckling, by elastically suppressing any lateral displacements of the fiber bundle. Taken together, these arguments imply that within a membrane tube the most plausible conformation of a fiber bundle is one that approximately maintains the bundle's contour length, while also maintaining the membrane tube's length and radius. One is therefore naturally led to consider a quasihelical configuration for a fiber bundle within an enclosing membrane tube (42).

To investigate whether such a helical conformation is energetically favorable, following Pronk et al. (42), the fiber bundle Hamiltonian Hp is studied,

| (15) |

where L is the length of the membrane tube, l is the contour length of the fiber bundle, and the effective persistence length for a tightly bound bundle of n fibers is taken to be lp = κpn2/2 (15), where κp is the bending modulus of a single fiber (κp ∼ 10 μm for actin (2)). A helical conformation for the fiber bundle is given by R(s) = r0(cos(ωs)i + sin(ωs)j) + sl/Lk, where to satisfy inextensibility one must have . Inserting this helical Ansatz for R(s) into the fiber-bundle Hamiltonian from Eq. 15, one obtains (42)

| (16) |

Minimizing Eq. 16 with regard to L, while assuming for simplicity a relatively modest helical fiber bundle deformation such that L/l ≃ 1, one obtains . Inserting this result into the above expression for the helical periodicity ω = N2π/l, where N is the total number of turns in the helix, it follows that .

Direct observation of a helical fiber-bundle conformation might presumably prove experimentally difficult for typical filopodia. However, some signs of a small helical deformation can be seen in the filopodia of Thyone (9). For the moment, it is instructive and highly informative to simply substitute the classical Euler buckling force into the expression for the total number of helical turns N derived above. On doing this, one finds that the total number of helical turns N required for this filament bundle to be stable under the action of fbuckle is given by .

Thus, it can be seen that even a very modest helical deformation of a fiber bundle within a membrane tube is enough to obviate the classical Euler buckling scenario (42).

Example Applications of Model

The model in this study, as outlined above, is now compared to experimental data available in the literature on growing filopodia in biological cells. Firstly, the role of capping dynamics in the filopodia of the acrosomal process of Thyone (9–14) is considered, then the possible effects of even modest amounts of capping protein on more common filopodia is discussed (1,4–7).

Acrosomal process of Thyone briareus

The acrosomal process of the sea cucumber Thyone briareus is extremely rapid, producing a filopodium which can extend 90 μm in 10 s, as Thyone sperm contacts egg jelly (for further details see (9–14)). For comparison, epithelial goldfish keratocyte cells are only able to glide a few microns over similar timescales (4). Thus Thyone represents perhaps the most dramatic example of the possible effects of capping protein dynamics on the assembly of actin fibers in filopodia. Moreover, it is known (9,10,12,14) that the number of fibers in the actin core decreases down the length of the filopodium, a fact which is commonly attributed to the presence of fiber capping. Furthermore, unlike the filopodia of typical cells, there exists a wealth of data in the literature (9,10,14) on the growth of a single filopodium in the case of Thyone, which greatly facilitates comparison to the model in this study.

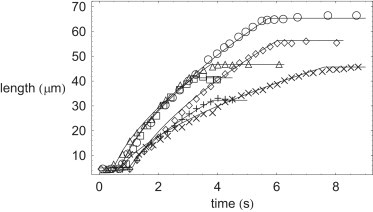

Shown in Fig. 2 are the best fits to the experimental data of Tilney and Inoué (9) on growing filopodia in Thyone. This study follows the same notation as Tilney and Inoué (9), in that Fig. 2 shows the comparison between the theory presented here (solid lines) and experimental data on sperm samples B (open circles), J (open squares), C (open diamonds), D (open triangles), A (crosses), and F (plus-signs) (9). The model parameters used to fit across all Thyone samples are displayed in Table 1, whereas the fitted model parameters for each individual Thyone sperm sample are shown in Table 2. From the fits one can see a remarkably good agreement between the theory presented here, and the experimental data obtained in Tilney and Inoué (9). The model-fit parameters in Tables 1 and 2 are also in excellent agreement with the previous theoretical treatment in Olbris and Herzfeld (13). The model presented in this work is able to capture, quantitatively, the three regimes of filopodium growth. Initially, for early times, there can be seen a lag phase in filopod growth, caused by the presence of a large number of uncapped growing fibers, inside a relatively tight-fitting membrane tube. Secondly, for intermediate times, a crossover can be seen, as more and more fibers are progressively capped, to more diffusionlike growth where L(t) ∼ t1/2, with membrane material being supplied freely from the membrane reservoir. Finally the fiber bundle stalls, due to the relatively few remaining uncapped fibers being unable to oppose the now much increased membrane force, due to the membrane undergoing large stretching, as the filopodium runs out of available membrane from the membrane reservoir at the base of the filopodium.

Figure 2.

Plotted comparison of filopodium growth dynamics between this study's theory (solid lines) and experimental data from Tilney and Inoué (9) on Thyone sperm samples B (○), J (□), C (♢), D (▵), A (×), and F (+).

Table 1.

Model parameters held fixed across all Thyone samples studied (B, J, C, D, A, and F) to fit the experimental data from Tilney and Inoué (9) on filopodium growth dynamics

| δa | 3 nm |

| 10 μM−1 s−1 | |

| 1 s−1 | |

| Da | 50 μm2 s−1 |

| 42 kDa | |

| 250 kDa | |

| ρc(0)/ρa(0) | 1/12 |

| δc | δa × |

| 3.6 μM−1 s−1 | |

| 4 × 10−4 s−1 | |

| Dc | Da × |

| KS | 0.4 Jm−2 |

| κm | 10−19 J |

Table 2.

Model parameters used for fitting individual Thyone samples (B, J, C, D, A, and F), to the experimental data on filopodium growth dynamics from Tilney and Inoué (9)

| ρa(0) (mM) | n0 | R0 (μm) | σ × 10−5 Jm−2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thyone B | 5.0 | 230 | 1.31 | 1.8 |

| Thyone J | 5.0 | 220 | 1.03 | 1.9 |

| Thyone D | 5.0 | 200 | 1.07 | 2.1 |

| Thyone C | 3.2 | 300 | 1.30 | 1.4 |

| Thyone F | 3.0 | 210 | 0.90 | 2.0 |

| Thyone A | 4.5 | 105 | 0.90 | 4.0 |

To quantitatively fit the experimental data on filopodial growth in Thyone, the above model requires that the presence of capping protein has the effect of decreasing the number of actin fibers in a fiber bundle from an initial value of ∼200 actin fibers at the base of the filopodium, to ∼5 actin fibers when the filopodium stalls its growth due to membrane stretching. Although the precise profile of how the number of actin bundle fibers decreases down filopodia in Thyone is not known, the previous experimental work from the literature (9,10,14) is in roughly qualitative agreement with that presented here. For example, Tilney and Inoué (9) quotes the number of actin fibers in a Thyone filopodium as decreasing from an initial value of ∼150 actin fibers at the base of the filopodium, to ∼18 actin fibers near its end.

Interestingly, for the model to accurately describe the growth dynamics of a filopodium in Thyone, it is required that the capping protein be of molecular mass ≃ 250 kDa, and in a stoichiometric ratio to that of actin (molecular mass ≃ 42 kDa) of 1/12. Proteins with such a molecular weight and stoichiometric ratio are known to be present in the acrosomal cup of Thyone (9), and therefore this modeling work can be seen to provide at least some evidence that these proteins are strongly implicated in actin fiber capping in Thyone.

The additional model parameters shown in Table 1 are relatively well known from existing experimental (9,10,14) and theoretical (11–13,15) work in the available literature. In particular, Table 1 shows that the molecular weight of actin monomers (), the actin monomer size (δa), and the monomeric actin diffusion constant (Da) agree exceedingly well with their experimentally measured values (9,10,14). Given these parameter values for actin, and the molecular weight of the capping protein (), simple size-scaling arguments can be used to estimate δc and Dc by assuming the scaling relationships δc ≃ δa × ()ν and , with an associated power-law exponent ν. To successfully fit the experimental data on Thyone, it was found that the monomeric size of the capping protein should scale in proportion to its molecular weight (ν ∼1). Other power-law type scaling behaviors were attempted (with ν ≠ 1), but none were able to successfully fit the experimental data on Thyone. This could possibly be explained by the capping protein monomers adopting a relatively anisotropic geometry, thus being more rodlike than compact and globularlike. This could further be consistent with the known fact that proteins can change their shape and orientation when they act to polymerize into long, thin fibers, due to a process referred to as monomer activation or structural plasticity (43). Alternatively one could just take the monomeric size (δc) and diffusion constant (Dc) of the capping protein (which are not accurately or well known experimentally) to be independent model parameters required to fit the experimental data on Thyone.

Table 2 shows that to fit individual Thyone samples, the model requires that the initial concentration of actin monomers (ρa(0)) vary slightly in the acrosomal cup of Thyone, as well as the initial number of uncapped actin fibers (n0), and the amount of membrane material (of roughly spherical area 4πR02) contained in the initial membrane reservoir. However, all of these fitted model parameters lay within the range of those found experimentally for Thyone (9,10,14).

More-typical filopodia

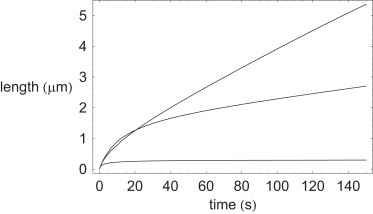

More-typical filopodia, such as are found in neuronal growth cones, keratocytes, and fibroblast cells (8,16), grow at a much reduced rate compared to those found in Thyone (9), and so it could be thought that the effect of capping protein on filopodial growth is much reduced in these cases. Indeed, it is known (1,4–7) that in more-typical physiological cells (such as fibroblasts), for filopodia to be produced (over and above lamellipodia, for example), the effects of fiber capping need to be suppressed close to the leading edge of a cell. In such cells, it is also known (28,29) that proteins such as VASP, protect actin barbed-ends from capping. Furthermore, the available actin monomer concentration (ρa(0)), and the number of actin fibers in a bundle (n0), tend to be much less than those values that appear in Thyone. Nevertheless, the modeling work shown in Fig. 3, demonstrates that even the presence of a relatively modest amount of capping protein can have a substantial effect on the growth of filopodia in more familiar biological cells. Thus the possible effects of capping protein on the dynamics of filopodia in fibroblasts and keratocytes cannot be simply ignored. Fig. 3 shows a plot comparing the growth of a filopod for three different values of the capping protein concentration ρc (from top to bottom, ρc(0) = 0.02, 0.2, 2.0 μM, respectively). Fig. 3 shows that as the capping protein concentration increases, firstly the rate of filopodium growth decreases, and secondly the ultimate length of the filopodium decreases concomitantly. The model parameters for actin polymerization and capping shown in Table 3, which are held fixed for the comparison plots shown in Fig. 3, are taken mostly from Mogilner and Rubinstein ((15) and references therein). The capping protein molecular weight () in Table 3 is taken from Wear and Cooper (18) and Cooper and Sept (19), and the capping rates are taken from Schafer et al. (20), Carlier and Pantaloni (21), Cooper and Schafer (22), Cooper and Pollard (23), Wear et al. (24), Mejillano et al. (25), Mullins et al. (26), and DiNubile and Huang (27). Note that for modeling the more modest growth of typical filopodia (as compared to Thyone), it has been reasonably assumed that membrane stretch effects are negligible in this case, such that fS as defined above can be safely ignored.

Figure 3.

Comparison plot for typical filopodia showing effects of presence of capping protein on filopodium growth dynamics. (Top to bottom) ρc(0) = 0.02, 0.2, and 2.0 μM, respectively.

Table 3.

Model parameters held fixed, and used, for comparing the effects of capping protein concentration on typical filopodium growth dynamics, as shown in Fig. 3

| δa | 3 nm |

| 10 μM−1 s−1 | |

| 1 s−1 | |

| Da | 5 μm2 s−1 |

| 42 kDa | |

| 64 kDa | |

| ρa(0) | 10 μM |

| δc | δa × |

| 3.6 μM−1 s−1 | |

| 4 × 10−4 s−1 | |

| Dc | Da × |

| n0 | 30 |

| f0 | 10 pN |

| r0 | 70 nm |

Discussion

This section will discuss some issues raised by, and some caveats pertaining to, the modeling work outlined above describing the effects of capping protein dynamics on the growth and stability of experimentally observed filopodia.

The enclosing membrane tube radius is essentially set by the membrane tension σ. If the tension is relatively low then the membrane radius is given by the canonical value r0. However, if the tension becomes high enough, then the membrane radius is now effectively given by the radius of the biofiber bundle b. For example, this high tension regime may be fixed by the nucleation phenomenon of the filopodia. In addition, the membrane-stretching term introduced here is completely compatible with that of Raucher and Sheetz (38) and Sheetz and Dai (39), as pertains to their demonstration of the manner in which the cell regulates its membrane tension. As the membrane runs out of membrane material, the surface tension increases, and membrane stretching effects can begin to become important. Moreover, as the limit r0 ∼ b when steric effects dominate monomer transport for tightly fitting membrane tubes is approached, then the theory presented here will necessarily break down. In this case a fuller and more rigorous account of such steric effects would necessitate taking into account the hydrodynamic interaction among monomers, the fiber bundle, the inner-membrane tube surface, and the cytoplasmic fluid, to find the effective monomeric diffusion constant. This study leaves this fascinating and important topic to future work.

The only effect of crosslinking between fibers considered here is that which stiffens the bundle of biofibers via a corresponding increase in the persistence length, leading to greater stability of the filopodium to buckling. In this study, it is assumed that the crosslinking protein does not couple the polymerization of neighboring actin filaments. Investigating this intriguing possibility will be left to future work.

For the filopodia of the sea cucumber Thyone, the number of filaments in a fiber bundle is known to decrease (9) as the growing tip is approached. It would be extremely interesting—though presumably very difficult—to directly image, experimentally, the decrease in the number of filaments closer to the filopodium's growing tip, such as would be demonstrated by the more-typical filopodia found in fibroblasts, keratocytes, and neuronal growth cones.

To accurately describe the acrosomal process in Thyone, it has been proposed in the literature (11,13) that osmotic pressure effects should also be included. The work presented here, which does not include such osmotic pressure effects, can be seen to capture the experimental data on Thyone filopodia rather well. Nevertheless, once the precise form of the decrease of the number of actin fibers in a Thyone filopodium becomes experimentally known, it may well prove necessary to include such osmotic pressure effects (11,13) in future modeling work, to produce a more realistic fiber bundling profile down the length of a Thyone filopodium.

In interesting recent articles (44,45) the role of possible stochastic effects on the dynamics of filopodial growth has been considered. In Lan and Papoian (44), the influence of noise on the diffusion and polymerization of actin is studied. One of the main results of Lan and Papoian (44) is that mean-field type behavior can be considered to be a good approximation to the more complex underlying stochastic behavior of polymerizing biofibers (with a few important caveats)—as long as a select few of the parameters in the model become renormalized (44)). Additionally, it is found in Lan and Papoian (44) that the length distribution of fibers in filopodia is rather narrow, again supporting a posteriori the use of mean-field type models. In Zhuravlev and Papoian (45), it is further suggested that filopodial turnover dynamics may be partially driven by stochastic effects of capping protein, thus leading to a finite lifetime for filopodia. It is also found in Zhuravlev and Papoian (45) that complete retraction of a filopodium is a relatively rare event, which becomes important on timescales much larger than those considered in this article. Moreover, the work presented here is more mean-field-like in approach, and follows in the long tradition of other, similar, mean-field treatments of polymerizing biofibers, such as Brownian ratchets (32) and microtubule dynamics (33–35), for which a vast body of work exists (2,3). Whereas in the case of microtubules, stochastic behavior is known to underlie its growth dynamics (leading, for instance, to dynamic instability (2,3)), mean-field theories are widely used in the literature (33–35) and have proved to be very successful in capturing the behavior of experimental data. Furthermore, as shown by us, the model used is able to accurately fit the experimental data on the filopodial dynamics of Thyone, thus validating, a posteriori, a mean-field-type approach. Stochastic effects could well be important for growing filopodia, however, and any further extension of the mean-field-type model presented here (over and above the possible renormalization of a few select parameters) is left to future work.

Bundling of actin filaments has been considered previously, for example in the context of stereocilia and microvilli (46–48). However, it is somewhat problematic to make a precise comparison between the results of this work on filopodia to the literature (46–48), as it is not obvious that filopodia and stereocilia, for instance, are governed by precisely the same underlying processes. Prost et al. (46) finds an exponential dependence on the number of fibers in a bundle down the length of a stereocilium, somewhat similar to the work outlined here, in an appropriate parameter range. Also, Atilgan et al. (47) uses a master-equation-type of approach to describe actin fiber bundling, which should prove to be similar to the mean-field-type approach presented here. Additionally, Gov (48) finds a Gaussian dependence of the number of fibers in a bundle with many interacting stereocilia, whereas this work deals with a single filopodium.

There is no explicit treadmilling considered in this article, as it is assumed that the filopodium polymerizes from one end only. However, the results of this work are valid in the presence of retrograde flow, where the relative rate of filopodial length change, monomer diffusion, and drift processes are unaffected, as pointed out and explained further in Mogilner and Rubinstein (15).

Arising from the work presented in this article, the following effects of protein capping on filopodial growth dynamics can be summarized. Firstly, it can be seen that via the utilization of capping protein, biological cells can have the means of perhaps somewhat paradoxically accelerating filopodium growth. The presence of fewer fibers in a given membrane tube implies an increased effective actin monomer flux to the growing fiber bundle tip. Counterbalancing this growth-promoting effect, however, is the need to have sufficient fibers in a bundle to successfully oppose the membrane force present, and avoid fiber bundle stalling and/or buckling. As seen above, even a modest amount of helical deformation in a polymerizing fiber bundle can ameliorate issues relating to fiber bundle buckling. However, with too few fibers, a fiber bundle is still liable to fiber stalling.

One is therefore naturally led (via inspection of Eq. 5, for example) to discuss issues such as the best strategy, via the tuning of capping protein levels, that a biological cell can adopt to grow a filopodium of a required length, in a requisite time. Of course, various different capping proteins and physiological capping mechanisms are at work in different organisms (as evidenced by this work's comparison of the growth of protrusions in Thyone and in more typical filopodia), therefore, it is evident that a given capping strategy utilized in the filopodia of one organism may not be so effective in another. Nevertheless, one general conclusion regarding capping that arises quite naturally out of this work seems to be that maintaining growing filopodia in biological cells may represent an optimal trade-off between increased capping (increased speed of growth, lower stalling, and buckling threshold) and reduced capping (lower speed of growth, higher stalling, and buckling threshold). It would be extremely interesting in future work to investigate further, whether the underlying capping mechanisms in biological cells are so arranged that the best possible strategy for producing precisely the required filopodia for the given physiological conditions occurs. In conclusion, this study has found that the presence of even a modest amount of capping protein can have a dramatic effect on the growth of typical filopodia. Furthermore, this modeling work can be seen to provide at least some evidence that capping proteins are strongly implicated in the filopodium growth dynamics of Thyone briareus. As a result, any future dynamical theories for filopodial actin growth in membrane tubes are likely to rely on an accurate treatment of the kinds of capping protein effects analyzed here.

Acknowledgments

I thank the anonymous referees for their helpful comments and suggestions.

References

- 1.Alberts B., Johnson A., Walter P. Garland; New York: 2002. Molecular Biology of the Cell. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boal D. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2001. Mechanics of the Cell. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bray D. Garland Publishing; New York: 1992. Cell Movements. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mattila P.K., Lappalainen P. Filopodia: molecular architecture and cellular functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:446–454. doi: 10.1038/nrm2406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pollard T.D., Borisy G.G. Cellular motility driven by assembly and disassembly of actin filaments. Cell. 2003;112:453–465. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00120-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Svitkina T.M., Bulanova E.A., Borisy G.G. Mechanism of filopodia initiation by reorganization of a dendritic network. J. Cell Biol. 2003;160:409–421. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200210174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vignjevic D., Yarar D., Borisy G.G. Formation of filopodia-like bundles in vitro from a dendritic network. J. Cell Biol. 2003;160:951–962. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200208059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitchison T., Kirschner M. Cytoskeletal dynamics and nerve growth. Neuron. 1988;1:761–772. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90124-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tilney L.G., Inoué S. Acrosomal reaction of Thyone sperm. II. The kinetics and possible mechanism of acrosomal process elongation. J. Cell Biol. 1982;93:820–827. doi: 10.1083/jcb.93.3.820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tilney L.G., Tilney M.S. Observations on how actin filaments become organized in cells. J. Cell Biol. 1984;99:76–82. doi: 10.1083/jcb.99.1.76s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oster G., Perelson A., Tilney L. A mechanical model for elongation of the acrosomal process in Thyone sperm. J. Math. Biol. 1982;15:259–265. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perelson A.S., Coutsias E.A. A moving boundary model of acrosomal elongation. J. Math. Biol. 1986;23:361–379. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olbris D.J., Herzfeld J. An analysis of actin delivery in the acrosomal process of Thyone. Biophys. J. 1999;77:3407–3423. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77172-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tilney L.G., Bonder E.M., Mooseker M.S. Actin from Thyone sperm assembles on only one end of an actin filament: a behavior regulated by profilin. J. Cell Biol. 1984;97:112–124. doi: 10.1083/jcb.97.1.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mogilner A., Rubinstein B. The physics of filopodial protrusion. Biophys. J. 2005;89:782–795. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.056515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Argiro V., Bunge M.B., Johnson M.I. A quantitative study of growth cone filopodial extension. J. Neurosci. Res. 1985;13:149–162. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490130111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mogilner A., Edelstein-Keshet L. Regulation of actin dynamics in rapidly moving cells: a quantitative analysis. Biophys. J. 2002;83:1237–1258. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)73897-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wear M.A., Cooper J.A. Capping protein: new insights into mechanism and regulation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2004;29:419–428. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cooper J.A., Sept D. New insights into mechanism and regulation of actin capping protein. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2008;267:183–206. doi: 10.1016/S1937-6448(08)00604-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schafer D.A., Jennings P.B., Cooper J.A. Dynamics of capping protein and actin assembly in vitro: uncapping barbed ends by polyphosphoinositides. J. Cell Biol. 1996;135:169–179. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.1.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carlier M.-F., Pantaloni D. Control of actin dynamics in cell motility. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;269:459–467. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cooper J.A., Schafer D.A. Control of actin assembly and disassembly at filament ends. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2000;12:97–103. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(99)00062-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cooper J.A., Pollard T.D. Effect of capping protein on the kinetics of actin polymerization. Biochemistry. 1985;24:793–799. doi: 10.1021/bi00324a039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wear M.A., Yamashita A., Cooper J.A. How capping protein binds the barbed end of the actin filament. Curr. Biol. 2003;13:1531–1537. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00559-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mejillano M.R., Kojima S., Borisy G.G. Lamellipodial versus filopodial mode of the actin nanomachinery: pivotal role of the filament barbed end. Cell. 2004;118:363–373. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mullins R.D., Heuser J.A., Pollard T.D. The interaction of Arp2/3 complex with actin: nucleation, high affinity pointed end capping, and formation of branching networks of filaments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:6181–6186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DiNubile M.J., Huang S. Capping of the barbed ends of actin filaments by a high-affinity profilin-actin complex. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton. 1997;37:211–225. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0169(1997)37:3<211::AID-CM3>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bear J.E., Svitkina T.M., Gertler F.B. Antagonism between ENA/VASP proteins and actin filament capping regulates fibroblast motility. Cell. 2002;109:509–521. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00731-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Samarin S., Romero S., Carlier M.F. How VASP enhances actin-based motility. J. Cell Biol. 2003;163:131–142. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200303191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bar-Ziv R., Tlusty T., Bershadsky A. Pearling in cells: a clue to understanding cell shape. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:10140–10145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pullarkat P.A., Dommersnes P., Ott A. Osmotically driven shape transformations in axons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006;96:048104. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.048104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peskin C.S., Odell G.M., Oster G.F. Cellular motions and thermal fluctuations: the Brownian ratchet. Biophys. J. 1993;65:316–324. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81035-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dogterom M., Yurke B. Measurement of the force-velocity relation for growing microtubules. Science. 1997;278:856–860. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5339.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kolomeisky A.B., Fisher M.E. Force-velocity relation for growing microtubules. Biophys. J. 2001;80:149–154. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76002-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mogilner A., Oster G. The polymerization ratchet model explains the force-velocity relation for growing microtubules. Eur. Biophys. J. 1999;28:235–242. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Safran S.A. Addison-Wesley Publishing; Reading, MA: 1994. Statistical Thermodynamics of Surfaces, Interfaces and Membranes. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Derényi I., Jülicher F., Prost J. Formation and interaction of membrane tubes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002;88:238101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.238101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raucher D., Sheetz M.P. Characteristics of a membrane reservoir buffering membrane tension. Biophys. J. 1999;77:1992–2002. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77040-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sheetz M.P., Dai J. Modulation of membrane dynamics and cell motility by membrane tension. Trends Cell Biol. 1996;6:85–89. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(96)80993-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hochmuth F.M., Shao J.Y., Sheetz M.P. Deformation and flow of membrane into tethers extracted from neuronal growth cones. Biophys. J. 1996;70:358–369. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79577-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Landau L.D., Lifschitz E.M. Pergamon Press; Oxford, England: 1986. Theory of Elasticity. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pronk S., Geissler P.L., Fletcher D.A. Limits of filopodium stability. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008;100:258102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.258102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kueh H.Y., Mitchison T.J. Structural plasticity in actin and tubulin polymer dynamics. Science. 2009;325:960–963. doi: 10.1126/science.1168823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lan Y., Papoian G.A. The stochastic dynamics of filopodial growth. Biophys. J. 2008;94:3839–3852. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.123778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhuravlev P.I., Papoian G.A. Molecular noise of capping protein binding induces macroscopic instability in filopodial dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:11570–11575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812746106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prost J., Barbetta C., Joanny J.-F. Dynamical control of the shape and size of stereocilia and microvilli. Biophys. J. 2007;93:1124–1133. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.098038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Atilgan E., Wirtz D., Sun S.X. Mechanics and dynamics of actin-driven thin membrane protrusions. Biophys. J. 2006;90:65–76. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.071480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gov N.S. Dynamics and morphology of microvilli driven by actin polymerization. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006;97:018101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.018101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]