Abstract

Swollenin is a protein from Trichoderma reesei that has a unique activity for disrupting cellulosic materials, and it has sequence similarity to expansins, plant cell wall proteins that have a loosening effect that leads to cell wall enlargement. In this study we cloned a gene encoding a swollenin-like protein, Swo1, from the filamentous fungus Aspergillus fumigatus, and designated the gene Afswo1. AfSwo1 has a bimodular structure composed of a carbohydrate-binding module family 1 (CBM1) domain and a plant expansin-like domain. AfSwo1 was produced using Aspergillus oryzae for heterologous expression and was easily isolated by cellulose-affinity chromatography. AfSwo1 exhibited weak endoglucanase activity toward carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) and bound not only to crystalline cellulose Avicel but also to chitin, while showing no detectable affinity to xylan. Treatment by AfSwo1 caused disruption of Avicel into smaller particles without any detectable reducing sugar. Furthermore, simultaneous incubation of AfSwo1 with a cellulase mixture facilitated saccharification of Avicel. Our results provide a novel approach for efficient bioconversion of crystalline cellulose into glucose by use of the cellulose-disrupting protein AfSwo1.

Cellulose is the primary polysaccharide of plant cell wall and the most abundant renewable biomass resource. Biological degradation of cellulose to soluble sugars has long been considered an alternative to the use of starch feedstocks for bioethanol production. Natural cellulose is an ordered, linear polymer of thousands of d-glucose residues linked by β-1,4-glucosidic bonds. Spontaneous crystallization of cellulose molecules due to chemical uniformity of glucose units and the high degree of hydrogen bonding in cellulose can often result in the formation of tightly packed microfibrils (8), which remain inaccessible to cellulolytic enzymes. No single enzyme is able to hydrolyze crystalline cellulose microfibrils completely. Synergistic effects of cellulase mixtures on crystalline cellulose degradation are well known (1, 7, 21). Nevertheless, cost-competitive technology for overcoming the recalcitrance of cellulosic biomass to enhance enzymatic saccharification is still a major impediment to the utilization of cellulosic materials in bioenergy generation.

Expansins are plant cell wall proteins that cause cell wall enlargement by a unique loosening effect in an acid-induced manner (15, 20). They are also involved in many physiological processes where cell wall extension occurs, such as pollination, fruit ripening, organ abscission, and seed germination (13, 14). It has been proposed that plant expansins disrupt hydrogen bonding between cellulose microfibrils and other cell wall polysaccharides without hydrolytic activity, causing sliding of cellulose fibers or expansion of the cell wall (18, 19, 27). Swollenin, an expansin-like protein, was isolated and characterized from the cellulolytic filamentous fungus Trichoderma reesei. It has a bimodular structure consisting of a carbohydrate-binding module family 1 (CBM1) domain and an expansin-like domain connected by a linker region rich in serine and threonine. Swollenin exhibits disruption activity on cellulosic materials such as cotton and algal cell walls without releasing any detectable reducing sugars (23). However, effects of cellulose disruption activity on degradation/saccharification of crystalline cellulose have not yet been reported.

Here, we report cloning a swollenin-like gene (designated Afswo1) from the filamentous fungus Aspergillus fumigatus. We also report its production by Aspergillus oryzae and characterization of the purified AfSwo1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, media, and growth conditions.

A. fumigatus TIMM0063 genomic DNA was used as a donor of the target gene, Afswo1. Escherichia coli DH5α was used as a subcloning host strain for DNA manipulation. A double-protease disruptant strain, A. oryzae NS-tApE (niaD− sC− ΔtppA ΔpepE) (22) was used for AfSwo1 production. Marker-transformed control strain S-tApE was made by transformation of NS-tApE strain with pgDN (17). Potato dextrose medium (Nissui Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan) and LB medium (1% Bacto tryptone, 0.5% Bacto yeast extract, 1% NaCl [wt/vol] pH 7.0) were used as routine storage media for A. oryzae and E. coli, respectively. Czapek Dox (CD) medium (2% d-glucose, 0.3% NaNO3, 0.2% KCl, 0.1% KH2PO4, 0.05% MgSO4·7H2O, 0.002% FeSO4·7H2O [wt/vol] pH 5.5) supplemented with methionine (0.015%, wt/vol) was used as a selective medium for transformation of A. oryzae. DPY medium (2% dextrin, 1% polypeptone, 0.5% yeast extract, 0.5% KH2PO4, 0.05% MgSO4·7H2O [wt/vol] pH 5.5) was used for AfSwo1 production. A. oryzae transformants were grown in DPY medium at 30°C for 4 days on a rotary shaker with 150 rpm.

Cloning, expression plasmid construction, and transformation of A. oryzae.

A pair of primers was designed for amplifying the Afswo1 gene based on the available sequence of a swollenin-like protein in A. fumigatus genome sequence database: Afswo-F (5′-GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTCGACGGAATGACTCTTCTATTTGG-3′) and Afswo-R (5′-GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTCTAGGTGAACTGCACTCCCAG-3′). Expression plasmid pgTAFSN was constructed based on a MultiSite Gateway three-fragment vector construction kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) as described previously (17), in which the Afswo1 gene was expressed under the control of the tef1 promoter, and niaD was used as selective marker in A. oryzae. The obtained plasmid pgTAFSN was introduced into the A. oryzae NS-tApE strain using protoplast-mediated transformation (11). Transformants (named the TAFSN strain) were selected on CD agar containing 1.2 M sorbitol and 0.015% methionine (wt/vol) and were then successively subcultured several times on selective medium to obtain a homokaryotic clone.

Cloning of the Afswo1 cDNA.

Total RNA of A. oryzae transformants producing AfSwo1 was isolated from the mycelium with Isogene agent (Nippon Gene, Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The first-strand cDNA was amplified by Moloney murine leukemia virus (MMLV) reverse transcriptase (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan) using oligo(dT)12-18 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) as a reverse primer. Using the first-strand cDNA, the Afswo1 cDNA was amplified by the primers (Afswo-F and Afswo-R). The Afswo1 cDNA was sequenced by ABI 310 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Production of AfSwo1 by A. oryzae transformants.

Among 20 transformants harboring the expression plasmid pgTAFSN, four strains were randomly selected and designated TAFSN1 to TAFSN4. A suspension of 2 × 105 conidia of the TAFSN strains was inoculated into a 100-ml Erlenmeyer flask containing 20 ml of DPY medium. After cultivation for 4 days at 30°C on a rotary shaker at 150 rpm, the culture supernatant was used directly for analysis of AfSwo1 production by SDS-PAGE.

Purification of AfSwo1 by affinity chromatography.

AfSwo1 was purified by cellulose affinity chromatography. The culture supernatant was collected by centrifugation and loaded onto a column packed with 2.5 g of Avicel-80 (Funakoshi, Tokyo, Japan), which was previously equilibrated with 0.1 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.0) containing 1 M (NH4)2SO4. Nonspecific proteins were washed out using the equilibration buffer. AfSwo1 was eluted with distilled water, and elution fractions were taken in 2-ml tubes. Absorbance at 280 nm of eluted fractions was measured to monitor protein concentration during chromatographic separation. The protein concentration was also determined by a Bio-Rad protein assay kit (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA) using bovine serum albumin as a standard. The purified protein was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. The bands were subjected to in-gel digestion with 12.5 ng/ml trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI). The resulting peptides were analyzed by an LTQ liquid chromatography/linear ion trap tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) system (Thermo Electron, Waltham, MA), and the purified protein was identified using the Mascot database-searching software (Matrix Science, London, United Kingdom), which performs protein identification by matching mass spectroscopy data with protein databases at NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

Halo assay analysis with carboxymethyl cellulose.

A halo assay was carried out to qualitatively analyze the endoglucanase activity using carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC; Sigma-Aldrich) as a substrate. Three microliters of the eluted fractions containing AfSwo1 (the sixth and seventh fractions) was dropped onto a 0.1% CMC-containing agar plate in 50 mM acetate buffer (pH 5.0). After incubation at 40°C for 2 to 3 h, a solution of Congo red (1 mg/ml; Wako, Osaka, Japan) was poured onto the plate. The plate was incubated for 15 min and then washed several times with a 1 M NaCl solution.

Analysis of optimal pH and temperature for endoglucanase activity.

In order to determine optimal pH for the endoglucanase activity of AfSwo1, 50 mM acetate buffer (pH 3.0 to 6.0) and 50 mM phosphate-citrate buffer (pH 6.0 to 8.0) were prepared. Ten microliters of the AfSwo1 solution (1 μg/μl) was incubated with 100 μl of reaction buffer containing 5 mg/ml CMC at various pHs for 1 h at 50°C. In the assay for the optimal temperature, an enzymatic reaction was performed in 50 mM acetate buffer (pH 5.0) at different temperatures (30 to 80°C) for 1 h. Released reducing sugar was determined by tetrazolium blue (Wako, Saitama, Japan) according to a previous report (10). One unit of endoglucanase activity was defined as the amount of enzyme producing 1 μmol of reducing sugar per minute.

Binding property of AfSwo1 to polysaccharides.

Avicel-80 (Funakoshi, Saitama Japan), chitin (Wako), and two kinds of xylan (from oat spelt and birch wood; Sigma-Aldrich) were used as binding matrices. A solution of the purified AfSwo1 (50 μg/50 μl) was mixed with 100 mg of binding matrix suspended in ∼300 μl of 15 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 150 mM NaCl. The mixture was shaken for 30 min, and then the supernatant was removed as an unbound fraction. After the sample was washed four times with 15 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 150 mM NaCl, the bound protein was dissociated from the matrix by boiling with SDS-PAGE sample buffer.

Analysis of cellulose disruption activity on filter paper and crystalline cellulose substrates.

Filter paper (603 cellulose thimbles; Whatman, Maidstone, United Kingdom) and insoluble crystalline cellulose (Avicel PH-101; Sigma-Aldrich) were used as solid cellulosic substrates. The purified AfSwo1 (50 μg) was added into 2 ml of 50 mM acetate buffer (pH 5.0) containing 10 mg of filter paper or 100 mg of Avicel PH-101. These samples were incubated at 40°C for 48 h (filter paper) or 72 h (Avicel PH-101) with shaking on a rotary shaker at 100 rpm to increase the interaction between the celluloses and AfSwo1. Furthermore, the optimum condition of cellulose disruption activity toward Avicel PH-101 was determined at various temperatures (30°C to 60°C) and pH levels (3.0 to 10.0) for 72 h. The physical structure of Avicel PH-101 after the AfSwo1 treatment was observed using a light microscope (all-in-one microscope Biorevo BZ-9000; Keyence, Osaka, Japan). Areas of the Avicel particles captured in the picture were calculated with MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Analysis of crystalline cellulose saccharification by AfSwo1 and cellulase mixtures.

AfSwo1 (0 to 20 μg) and 5.0 μl of a cellulase mixture were mixed with 10 mg of Avicel (particle size less than 20 μm; Sigma-Aldrich) in 3.0 ml of 50 mM acetate buffer (pH 5.0). These samples were incubated at 40°C for 72 h with shaking. The cellulase mixture consisted of Celluclast 1.5L (cellulase from T. reesei ATCC 26921; Sigma-Aldrich) and Novozyme 188 (cellobiase from Aspergillus niger; Sigma-Aldrich) at a ratio of 5:1. Released d-glucose was determined with a Biosensor BF-5 (Oji-Keisoku Kiki, Amagasaki, Japan). Conversion of cellulose to glucose was calculated by the following equation: conversion of glucose (%) = [mg of glucose produced]/[mg of glucose units in cellulose] × 100.

RESULTS

Cloning of the Afswo1 gene encoding a swollenin-like protein from A. fumigatus.

We searched for genes encoding proteins similar to T. reesei swollenin (SWOI) or plant expansin in the Aspergillus Comparative Databases (http://www.broad.mit.edu/annotation/genome/aspergillus_group/MultiHome.html) and found one gene encoding a swollenin-like protein in A. fumigatus and its close relative, Neosartorya fischeri. The A. fumigatus gene was cloned from the A. fumigatus TIMM0063 strain and designated Afswo1. Based on a comparison of its cloned cDNA (see Materials and Methods) and the genomic sequence data, it was revealed that the Afswo1 coding region comprises 1,741 nucleotide base pairs interrupted by six introns and encodes a 476-amino-acid protein (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). There is another intron between Cys300 and Cys301 (GenBank accession number AB539167), which is different from the predicted sequence from the A. fumigatus Af293 strain (GenBank accession number XM_742655). The amino acid identity between AfSwo1 and SWOI from T. reesei is 65.4%. Domain analysis by PROSITE (http://br.expasy.org/prosite/) demonstrated that AfSwo1 consists of carbohydrate-binding module family 1 (CBM1), family 45 endoglucanase-like domain of expansin (Expansin_EG45) and a cellulose-binding-like domain of expansin (Expansin_CBD) (see Fig. S1). The CBM1 of fungal cellulases contains three aromatic amino acids that form a hydrophobic flat surface involved in binding affinity to cellulose, where the third residue is conserved as a polar tyrosine (16, 24). In the CBM1 of AfSwo1, WYY residues are also conserved while the corresponding aromatic amino acid residues in SWOI from T. reesei are FWY (see Fig. S1). In the Expansin_EG45 domain, an HMD motif instead of HFD motif is conserved in AfSwo1 as a catalytic motif of glycoside hydrolase family 45 (5). Expansin_EG45 and Expansin_CBD domains in AfSwo1 have similarities to those in plant expansins. A linker region rich in serine (Ser) and threonine (Thr) residues is present between the two domains, CBM1 and Expansin_EG45, in AfSwo1 (see Fig. S1).

AfSwo1 production by A. oryzae and its purification.

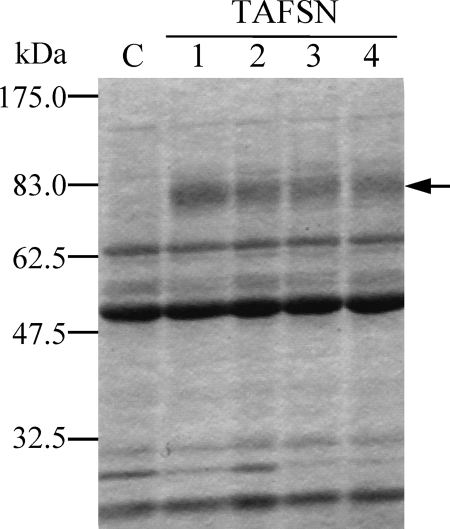

In order to obtain a large amount of AfSwo1 for biochemical assays, we produced it by the A. oryzae transformant. The expression was done using the tef1 promoter that has constitutively strong promoter activity (12). Four transformants (TAFSN strains) expressing AfSwo1 were cultured in DPY liquid medium, and the culture supernatant was subjected to SDS-PAGE analysis. As shown in Fig. 1, the transformants efficiently produced AfSwo1 as smeared bands, which was not observed in the culture supernatant of the marker-transformed control strain.

FIG. 1.

SDS-PAGE analysis of the AfSwo1 produced by A. oryzae. The culture supernatant (16 μl) of each transformant was analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Four transformants (strains TAFSN1 to TAFSN) were used for AfSwo1 production. The arrow points to the bands specifically seen in the TAFSN strains. C, marker-transformed control strain (S-tApE).

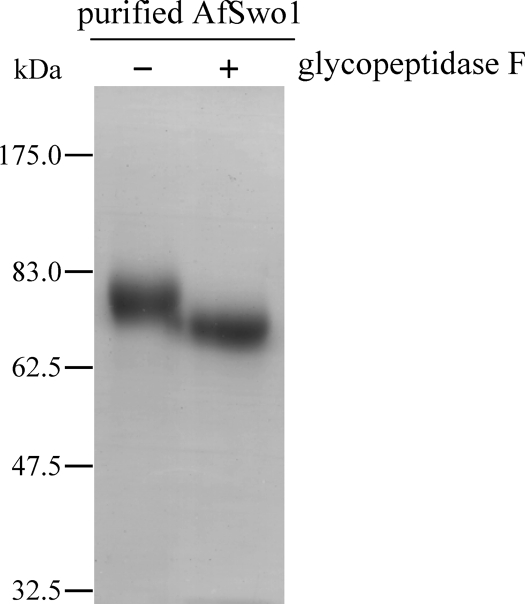

We purified AfSwo1 from the culture supernatant by a one-step process using cellulose-affinity chromatography. The AfSwo1 bound to the crystalline cellulose Avicel and was eluted with distilled water. SDS-PAGE analysis showed that the purified AfSwo1 was detected as a single band with a molecular mass around 78 kDa (Fig. 2), while no bands were detected after cellulose affinity chromatography from the culture supernatant of the control strain. LC-MS/MS analysis using trypsin-digested polypeptides from the ∼78-kDa band confirmed that the purified protein was AfSwo1 with 10 matched peptides (sequence positions 148 to 168, 169 to 190, 219 to 226, 265 to 298, 315 to 335, 336 to 350, 419 to 428, 429 to 438, 439 to 449, 450 to 476) and 37.6% sequence coverage. The amount of the purified AfSwo1 was estimated to be approximately 300 mg from 1 liter of culture medium according to measurement of protein concentration. The molecular size of the purified protein was 1.6 times higher than the deduced molecular mass of 48.4 kDa without the predicted signal peptide. AfSwo1 has six predicted N-glycosylation sites (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material); nevertheless, its band shifted down slightly, to approximately 70 kDa, after removal of the N-glycan by treatment with glycopeptidase F (Fig. 2). O-Glycosylation sites in AfSwo1 were predicted by NetOGlyc, version 3.1 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/NetOGlyc/). All the serine and threonine residues from Thr59 to Thr94 in the linker region were predicted to be O glycosylated except Ser62 residue while all of Ser and Thr residues outside this region were not predicted to be O glycosylated (see Fig. S1). The linker region rich in Ser/Thr is heavily O glycosylated in T. reesei cellobiohydrolase (6). The purified AfSwo1 was used in the following experiments.

FIG. 2.

The purified AfSwo1 and its deglycosylation analysis. The AfSwo1 produced by A. oryzae was purified (− lane) and treated with glycopeptidase F at 37°C for 20 h (+ lane).

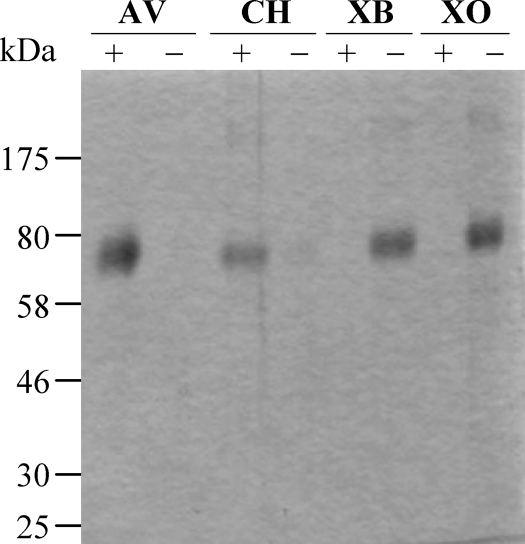

Binding analysis of AfSwo1 with polysaccharides.

Since AfSwo1 has two potential carbohydrate binding domains (CBM1 and Expansin_CBD), we investigated the binding ability of AfSwo1 to several polysaccharides. As shown in Fig. 3, AfSwo1 had a significant binding affinity to crystalline cellulose Avicel among the substrates tested. It also showed an affinity to chitin but no obvious binding affinity toward xylan.

FIG. 3.

Binding assay of AfSwo1 to polysaccharides. AfSwo1 was subjected to a binding assay with a polysaccharide matrix. The bound (+) and unbound (−) fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE analysis. AV, Avicel; CH, chitin; XB, xylan from birch wood; XO, xylan from oat spelt.

Endoglucanase activity of AfSwo1.

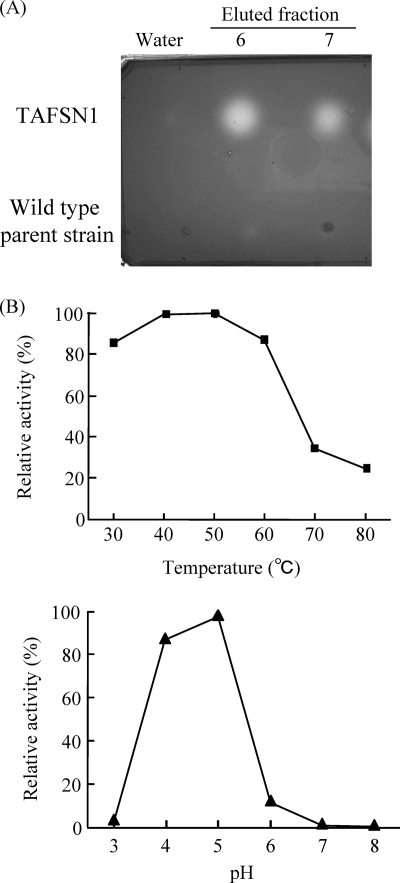

AfSwo1 contains an Expansin_EG45 domain, and part of the catalytic residues for endoglucanase activity are conserved. In order to examine endoglucanase activity of the purified AfSwo1, a halo assay was performed using a carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) substrate. After the plate was stained with Congo red, a clear halo was formed where the eluted fractions containing AfSwo1 had been dropped, whereas spotting with the equivalent fractions of the wild-type parent strain caused no halo (Fig. 4A), indicating degradation of CMC by AfSwo1. Ion exchange chromatography using the affinity-purified AfSwo1 showed that the peak fraction of AfSwo1 coincided with that of endoglucanase activity (data not shown). Furthermore, we quantified reducing sugar released from CMC for optimal temperature and pH of the endoglucanase activity. It was revealed that the optimal temperature was 50°C and that the optimal pH was 5.0 (Fig. 4B). These results indicated that AfSwo1 exhibited endoglucanase activity toward CMC. However, compared with other endoglucanases (26), the specific activity of endoglucanase in AfSwo1 was very low at 2.6 U/mg.

FIG. 4.

Endoglucanase activity of AfSwo1 toward CMC. (A) Halo assay. Three microliters of the eluted fractions including AfSwo1 (see Materials and Methods) were dropped onto the CMC-containing plate. Aliquots of equivalent fractions of the wild-type parent strain (NS-tApE) were also dropped on the plate. The plate was incubated with Congo red solution and washed. Water was used as a control. (B) Optimal temperature and pH. Endoglucanase activity of AfSwo1 was measured under the indicated conditions, and results are represented as relative values (%).

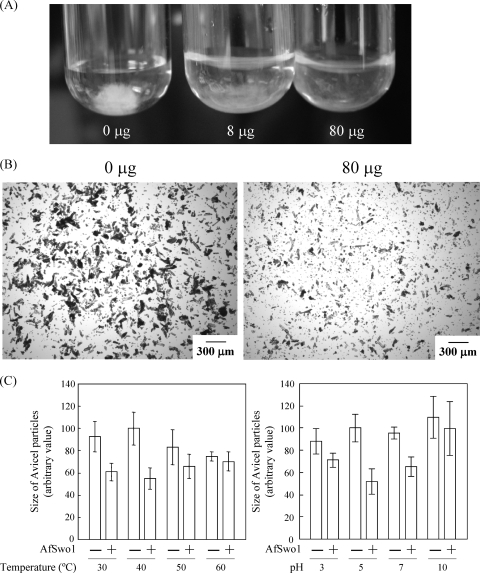

Disruption activity of AfSwo1 toward crystalline cellulose.

The cellulose disruption activity of AfSwo1 was examined using two kinds of celluloses that show different degrees of crystallization. Filter paper and crystalline cellulose (Avicel), were treated with AfSwo1. When filter paper with a low degree of crystallization was used, we observed cellulose disruption in an AfSwo1 concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 5A). In the analysis of disruption activity targeting Avicel with a high degree of crystallization, light microscopy was employed to observe the change in physical structure of crystalline cellulose. Smaller particles were found in the AfSwo1-treated sample than in the control (Fig. 5B). Disruption activity at various temperatures and pH was further analyzed by quantifying the particle sizes of Avicel after treatment with AfSwo1. Greater cellulose disruption activity was detected at 40°C at pH 5.0 (Fig. 5C), and the optimal curves of temperature and pH were similar to those of AfSwo1 endoglucanase activity. No released reducing sugars and glucose were detected using filter paper and Avicel (data not shown). These results indicated that AfSwo1 exhibited disruption activity toward crystalline cellulose without releasing any detectable reducing sugars.

FIG. 5.

Disruption activity of AfSwo1 toward crystalline celluloses. (A) Disruption activity of AfSwo1 toward filter paper. Filter paper (10 mg) was incubated with the purified AfSwo1 (0, 800, and 8,000 μg/g of substrate) at 40°C for 48 h by shaking. (B) Disruption activity of AfSwo1 toward Avicel crystalline cellulose. Light microscopy data that show the physical structure of the crystalline cellulose Avicel after incubation with 0 and 800 μg/g of substrate of AfSwo1 at 40°C for 72 h by shaking. (C) Size of the Avicel particles after the AfSwo1 treatment. Avicel was incubated in the presence (+) or absence (−) of AfSwo1 (800 μg/g of substrate) for 72 h at indicated temperatures and pH. Sizes of the Avicel particles in at least four independent experiments were averaged and are represented as arbitrary values with standard deviations.

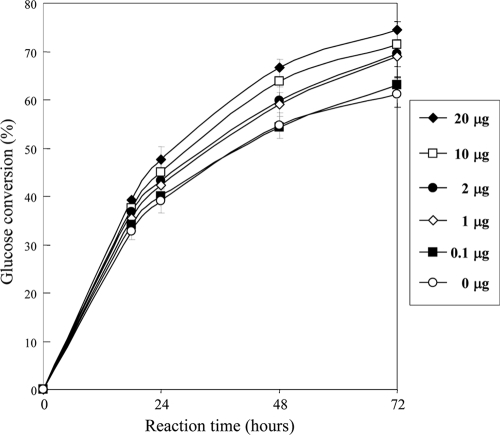

Promotion of efficient saccharification of crystalline cellulose.

We further investigated the potential effect of AfSwo1 with cellulase mixtures in promoting cellulose saccharification. Crystalline cellulose (Avicel) was incubated at 40°C for 72 h with AfSwo1 (0 to 20 μg) and the cellulase mixture from T. reesei and A. niger (see Materials and Methods). The glucose conversion rate in the saccharification process is shown in Fig. 6. In 72 h, the glucose conversion rate was 74.4% (20 μg) and 61.2% (no addition of AfSwo1). The glucose conversion rate rose depending on the amount of AfSwo1 and was improved by 1.2 times with 20 μg of the protein. These results demonstrated that AfSwo1 promoted the degradation of crystalline cellulose into glucose with the cellulase mixture.

FIG. 6.

Promoting effect of AfSwo1 on saccharification of crystalline cellulose by cellulase mixture. Avicel in acetate buffer was treated with the purified AfSwo1 (0, 100, 1,000, and 2,000 μg/g of substrate) and a cellulase mixture from T. reesei and A. niger at 40°C. The amount of released glucose was determined after the indicated times. Averages and standard deviations of glucose conversion (percent) for three independent experiments are represented.

DISCUSSION

It is surprising that a swollenin-like gene was found only in A. fumigatus among all the Aspergillus organisms examined (A. nidulans, A. niger, A. oryzae, A. flavus, A. clavatus, A. terreus). A. fumigatus has a number of glycosyl hydrolases such as cellulases and hemicellulases (25). It may be hypothesized that the pathogenic fungus A. fumigatus has also evolved to be a saprobe by acquiring the ability to efficiently degrade plant cell wall polymers or that AfSwo1 plays an important role in pathogenesis.

Using CMC, which has only a β-1,4-glucosidic linkage and is used as a model substrate for endoglucanase activity, we detected a low level of endoglucanase activity of AfSwo1, which may be consistent with the low activity of T. reesei SWOI toward barley β-glucan (23). We confirmed that no peptides originating from A. oryzae endoglucanases and other proteins were detected in the purified AfSwo1 fraction by LC-MS/MS analysis. An HFD motif which functions as part of the catalytic site of EG45 (5) was found to be conserved in expansin (3, 4), while it was replaced with HMD in AfSwo1 (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). However, plant expansins have not yet been experimentally demonstrated to possess endoglucanase activity. Recently, Bouzarelou and coworkers (2) have studied another class of expansin-like protein (EglD) from A. nidulans which lacks CBM1 and Expansin_CBD domains and in which the HFD motif was replaced with HLD. Nevertheless, they failed to detect the endoglucanase activity toward CMC, and its cellulose disruption activity has not yet been determined. The reason for the differences in endoglucanase activity between expansin-like proteins and AfSwo1 remains elusive.

AfSwo1 exhibited cellulose disruption activity toward Avicel, which is similar to the finding that the highly crystalline cellulose of algal cell wall was partially disrupted by T. reesei SWOI (23). We further showed that optimal curves of temperature and pH for the AfSwo1 disruption activity toward Avicel were similar to those of its endoglucanase activity (Fig. 4B and 5C). AfSwo1 is distantly related to family 45 endoglucanases, as shown in the phylogenetic tree of Igarashi et al. (9). These investigators reported that cellulosic suspensions were dispersed when they were incubated with Phanerochaete chrysosporium family 45 endoglucanase PcCel45C. Hence, it can be hypothesized that AfSwo1 and PcCel45C may share a common mechanism for the disruption activity on cellulosic materials. Molecular dissection of AfSwo1 is required to identify the amino acid residues involved in the cellulose disruption activities. Furthermore, the most noteworthy finding in this paper is that simultaneous incubation with AfSwo1 facilitated saccharification of the crystalline cellulose Avicel with the cellulase mixture (Fig. 6). It is likely that disruption of crystalline cellulose by AfSwo1 increased the surface area, making the cellulose more accessible to cellulases. Although the cellulase mixture (Celluclast 1.5L) used in this study may contain some amounts of T. reesei SWOI, it is suggested that the disruption activity toward crystalline cellulose is limited in commercial enzyme products. This study is the first to demonstrate promotion of the cellulase-mediated saccharification of crystalline cellulose by a protein having the disruption activity.

Disruption activity toward cellulosic materials provides an attractive tool for biotechnological applications. Abundant production of AfSwo1 from the pathogenic fungus A. fumigatus by the safe filamentous fungus A. oryzae would allow large-scale processing of cellulose and also a wide range of industrial applications. The efficient and economical bioconversion of cellulose to glucose still remains a challenging bottleneck for bioethanol production. Our results provide a novel approach for the disruption of cellulose for efficient saccharification of cellulosic materials.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Keisuke Ohsumi (Astellas Pharma Inc.) for providing the genomic DNA of the A. fumigatus TIMM0063 strain.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 19 February 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boisset, C., C. Pétrequin, H. Chanzy, B. Henrissat, and M. Schülein. 2001. Optimized mixtures of recombinant Humicola insolens cellulases for the biodegradation of crystalline cellulose. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 72:339-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bouzarelou, D., M. Billini, K. Roumelioti, and V. Sophianopoulou. 2008. EglD, a putative endoglucanase, with an expansin like domain is localized in the conidial cell wall of Aspergillus nidulans. Fungal Genet. Biol. 45:839-850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cosgrove, D. J. 1997. Relaxation in a high-stress environment: the molecular bases of extensible cell walls and cell enlargement. Plant Cell 9:1031-1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cosgrove, D. J. 2000. Loosening of plant cell walls by expansins. Nature 407:321-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davies, G. J., S. P. Tolley, B. Henrissat, C. Hjort, and M. Schülein. 1995. Structures of oligosaccharide-bound forms of the endoglucanase V from Humicola insolens at 1.9 Å resolution. Biochemistry 34:16210-16220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fägerstam, L. G., L. G. Pettersson, and J. Engström. 1984. The primary structure of a 1,4-ß-glucan cellobiohydrolase from the fungus Trichoderma reesei QM 9414. FEBS Lett. 167:309-315. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henrissat, B., H. Driguez, C. Viet, and M. Schülein. 1985. Synergism of cellulases from Trichoderma reesei in the degradation of cellulose. Biotechnology (NY) 3:722-726. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hon, D. N. S. 1994. Cellulose: a random walk along its historical path. Cellulose 1:1-25. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Igarashi, K., T. Ishida, C. Hori, and M. Samejima. 2008. Characterization of endoglucanase belonging to new subfamily of glycoside hydrolase family 45 from the basidiomycete Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:5628-5634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jue, C. K., and P. N. Lipke. 1985. Determination of reducing sugars in the nanomole range with tetrazolium blue. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods 11:109-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kitamoto, K. 2002. Molecular biology of the Koji molds. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 51:129-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kitamoto, N., J. Matsui, Y. Kawai, A. Kato, S. Yoshino, K. Ohmiya, and N. Tsukagoshi. 1998. Utilization of the TEF1-alpha gene (TEF1) promoter for expression of polygalacturonase genes, pgaA and pgaB, in Aspergillus oryzae. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 50:85-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee, Y., D. Choi, and H. Kende. 2001. Expansins: ever expanding numbers and functions. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 4:527-532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li, Y., and S. McQueen-Mason. 2003. Expansins and cell growth. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 6:603-610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li, Z., D. M. Durachko, and D. J. Cosgrove. 1993. An oat coleoptile wall protein that induces wall extension in vitro and that is antigenically related to a similar protein from cucumber hypocotyls. Planta 191:349-356. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Linder, M., M. L. Mattinen, M. Kontteli, G. Lindeberg, J. Ståhlberg, T. Drakenberg, T. Reinikainen, G. Pettersson, and A. Annila. 1995. Identification of functionally important amino acids in the cellulose-binding domain of Trichoderma reesei cellobiohydrolase I. Protein Sci. 4:1056-1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mabashi, Y., T. Kikuma, J. Maruyama, M. Arioka, and K. Kitamoto. 2006. Development of a versatile expression plasmid construction system for Aspergillus oryzae and its application to visualization of mitochondria. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 70:1882-1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McQueen-Mason, S., and D. J. Cosgrove. 1994. Disruption of hydrogen bonding between plant cell wall polymers by proteins that induce wall extension. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91:6574-6578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McQueen-Mason, S., and D. J. Cosgrove. 1995. Expansin mode of action on cell walls. Analysis of wall hydrolysis, stress relaxation, and binding. Plant Physiol. 107:87-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McQueen-Mason, S., D. M. Durachko, and D. J. Cosgrove. 1992. Two endogenous proteins that induce cell wall extension in plants. Plant Cell 4:1425-1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murashima, K., A. Kosugi, and R. H. Doi. 2002. Synergistic effects on crystalline cellulose degradation between cellulosomal cellulases from Clostridium cellulovorans. J. Bacteriol. 184:5088-5095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nemoto, T., T. Watanabe, Y. Mizogami, J. Maruyama, and K. Kitamoto. 2009. Isolation of Aspergillus oryzae mutants for heterologous protein production from a double proteinase gene disruptant. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 82:1105-1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saloheimo, M., M. Paloheimo, S. Hakola, J. Pere, B. Swanson, E. Nyyssönen, A. Bhatia, M. Ward, and M. Penttilä. 2002. Swollenin, a Trichoderma reesei protein with sequence similarity to the plant expansins, exhibits disruption activity on cellulosic materials. Eur. J. Biochem. 269:4202-4211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takashima, S., M. Ohno, M. Hidaka, A. Nakamura, H. Masaki, and T. Uozumi. 2007. Correlation between cellulose binding and activity of cellulose-binding domain mutants of Humicola grisea cellobiohydrolase. FEBS Lett. 581:5891-5896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tekaia, F., and J. P. Latgé. 2005. Aspergillus fumigatus: saprophyte or pathogen? Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 8:385-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Todaka, N., C. M. Lopez, T. Inoue, K. Saita, J. Maruyama, M. Arioka, K. Kitamoto, T. Kudo, and S. Moriya. 2010. Heterologous expression and characterization of an endoglucanase from a symbiotic protist of the lower termite, Reticulitermes speratus. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 160:1168-1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whitney, S. E., M. J. Gidley, and S. J. McQueen-Mason. 2000. Probing expansin action using cellulose/hemicellulose composites. Plant J. 22:327-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.