Abstract

Deletion of cclA, a component of the COMPASS complex of Aspergillus nidulans, results in the production of monodictyphenone and emodin derivatives. Through a set of targeted deletions in a cclA deletion strain, we have identified the genes required for monodictyphenone and emodin analog biosynthesis. Identification of an intermediate, endocrocin, from an mdpHΔ strain suggests that mdpH might encode a decarboxylase. Furthermore, by replacing the promoter of mdpA (a putative aflJ homolog) and mdpE (a putative aflR homolog) with the inducible alcA promoter, we have confirmed that MdpA functions as a coactivator. We propose a biosynthetic pathway for monodictyphenone and emodin derivatives based on bioinformatic analysis and characterization of biosynthetic intermediates.

Fungi have evolved to produce many natural products that kill or inhibit the growth of other organisms in the ecosystems in which they live. For this reason, it is not surprising that fungal secondary metabolites are rich sources of useful medicines such as penicillin, cyclosporine, and lovastatin (16). Genome sequencing of members of the genus Aspergillus, Aspergillus nidulans, for example (14), has revealed that there are many more gene clusters than known secondary metabolites. This might be due to the fact that most genes responsible for secondary metabolite biosynthesis are silent under normal laboratory growth conditions or that the production levels are below the detection limit of current instruments for structure elucidation, especially nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) (2, 7, 8). Thus, a major obstacle in identifying these metabolites is finding conditions to turn on the expression of secondary metabolite gene clusters (23).

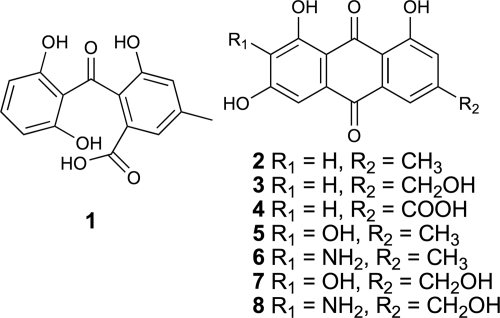

Genome sequencing also showed that many secondary metabolite clusters are located near the telomeres of chromosomes, where transcription is noted to be controlled by epigenetic regulation, such as histone deacetylation and DNA methylation (24). Accumulating evidence of the linkage between epigenetic regulation and secondary metabolite production led us to examine the function of the COMPASS (complex associated with Set1) complex, which methylates lysine 4 on histone H3 (20, 25). Loss of function of a critical member of the COMPASS complex, cclA (an ortholog of Saccharomyces cerevisiae bre2 [20]), activated the expression of at least two secondary metabolite clusters (3). One of the clusters, named the mdp cluster, produced monodictyphenone (Fig. 1, compound 1), emodin (compound 2), and emodin derivatives (compounds 3 to 6) (see also Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Here, we report the elucidation of the monodictyphenone biosynthetic pathway by creating a series of targeted deletions in a cclA null background to determine the genes required for monodictyphenone biosynthesis and characterizing intermediate compounds produced in the deletion strains.

FIG. 1.

Structures of monodictyphenone (1), emodin (2), and emodin analogs (3 to 8).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fungal strains and molecular genetic manipulations.

Deletions of 13 genes, designated AN10039.4 to AN10023.4 (Fig. 2) according to the Central Aspergillus Data Repository designations (CADRE; http:www.cadre-genomes.org.uk), were generated by replacing each gene with the Aspergillus fumigatus pyrG gene in the A. nidulans strain LO2051 (nkuAΔ stcJΔ cclAΔ) (complete genotypes are in Table 1). Strains overexpressing MdpA were generated from LO2026 (nkuAΔ stcJΔ) and LO2333 [nkuAΔ stcJΔ alcA(p)-mdpE] (3). An 86-bp fragment immediately upstream of the mdpA start codon was replaced with a fragment containing A. fumigatus pyroA followed by a 401-bp fragment containing the A. nidulans alcA promoter [alcA(p)] (30) such that the coding sequence of mdpA was placed under the control of the alcA promoter. Fusion PCR, protoplast production, and transformation were carried out as described previously (28), and the primers for fusion PCR are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Three or more transformants for the mdpA promoter replacement and each gene deletion were analyzed by diagnostic PCR (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material) (27). Strains were accepted as being correct only if they gave the expected diagnostic PCR patterns with three different primer sets. Diagnostic PCR with multiple primer sets allows one to determine reliably if correct gene targeting has occurred. It does not allow one to detect additional heterologous integrations, but such integrations are rare (<2%) in nkuA deletion strains (22). At least two correct transformants for each gene deletion or promoter replacement were used for high-performance liquid chromatography-photodiode array detection mass spectrometry (HPLC-DAD-MS) analysis (see below), and it is extremely unlikely that random integrations of transforming DNA would both occur and cause the same alterations of the metabolite profiles.

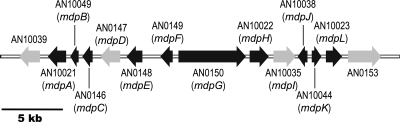

FIG. 2.

Organization of the monodictyphenone (mdp) gene cluster in A. nidulans. Each arrow indicates the direction of transcription and relative sizes of the open reading frames (ORFs) deduced from analysis of the nucleotide sequences. ORFs in black are genes involved in monodictyphenone synthesis, and ORFs in gray are not required for monodictyphenone synthesis.

TABLE 1.

A. nidulans strains used in this study

| Fungal strain or transformant(s)a | cclA and/or mdp mutation(s) | Genotypeb |

|---|---|---|

| LO2026 | None | pyrG89 pyroA4 nkuA::argB riboB2 stcJ::AfriboB |

| LO2051 | cclAΔ | pyrG89 pyroA4 nkuA::argB riboB2 stcJ::AfriboB cclA::AfpyroA |

| LO2731, LO2732, LO2733 | cclAΔ, AN10039.4Δ | pyrG89 pyroA4 nkuA::argB riboB2 stcJ::AfriboB cclA::AfpyroA AN10039.4::AfpyrG |

| LO2736, LO2737, LO2739 | cclAΔ, mdpAΔ | pyrG89 pyroA4 nkuA::argB riboB2 stcJ::AfriboB cclA::AfpyroA mdpA::AfpyrG |

| LO2741, LO2743, LO2745 | cclAΔ, mdpBΔ | pyrG89 pyroA4 nkuA::argB riboB2 stcJ::AfriboB cclA::AfpyroA mdpB::AfpyrG |

| LO2746, LO2747 | cclAΔ, mdpCΔ | pyrG89 pyroA4 nkuA::argB riboB2 stcJ::AfriboB cclA::AfpyroA mdpC::AfpyrG |

| LO2751, LO2752 | cclAΔ, mdpDΔ | pyrG89 pyroA4 nkuA::argB riboB2 stcJ::AfriboB cclA::AfpyroA mdpD::AfpyrG |

| LO2756, LO2759 | cclAΔ, mdpEΔ | pyrG89 pyroA4 nkuA::argB riboB2 stcJ::AfriboB cclA::AfpyroA mdpE::AfpyrG |

| LO2761, LO2762, LO2763 | cclAΔ, mdpFΔ | pyrG89 pyroA4 nkuA::argB riboB2 stcJ::AfriboB cclA::AfpyroA mdpF::AfpyrG |

| LO2149 | cclAΔ, mdpGΔ | pyrG89 pyroA4 nkuA::argB riboB2 stcJ::AfriboB cclA::AfpyroA mdpG::AfpyrG |

| LO2766, LO2767, | cclAΔ, mdpHΔ | pyrG89 pyroA4 nkuA::argB riboB2 stcJ::AfriboB cclA::AfpyroA mdpH::AfpyrG |

| LO2772, LO2773, LO2774 | cclAΔ, mdpIΔ | pyrG89 pyroA4 nkuA::argB riboB2 stcJ::AfriboB cclA::AfpyroA mdpI::AfpyrG |

| LO2776, LO2777, LO2778 | cclAΔ, mdpJΔ | pyrG89 pyroA4 nkuA::argB riboB2 stcJ::AfriboB cclA::AfpyroA mdpJ::AfpyrG |

| LO2782, LO2784 | cclAΔ, mdpKΔ | pyrG89 pyroA4 nkuA::argB riboB2 stcJ::AfriboB cclA::AfpyroA mdpK::AfpyrG |

| LO2786, LO2788, LO2789 | cclAΔ, mdpLΔ | pyrG89 pyroA4 nkuA::argB riboB2 stcJ::AfriboB cclA::AfpyroA mdpL::AfpyrG |

| LO2333 | alcA(p)-mdpE | pyrG89 pyroA4 nkuA::argB riboB2 stcJ::AfriboB mdpE::AfpyrG-alcA(p)-mdpE |

| LO3530, LO3531, LO3532 | alcA(p)-mdpA | pyrG89 pyroA4 nkuA::argB riboB2 stcJ::AfriboB mdpA::AfpyroA-alcA(p)-mdpA |

| LO3570, LO3572 | alcA(p)-mdpE, alcA(p)-mdpA | pyrG89 pyroA4 nkuA::argB riboB2 stcJ::AfriboB mdpE::AfpyrG-alcA(p)-mdpE mdpA::AfpyroA-alcA(p)-mdpA |

Multiple transformants were used in analyses of secondary metabolite production. All strains carry nkuAΔ and stcJΔ and were produced in this study except for LO2026, LO2051, LO2149, and LO2333 (3).

AfriboB, AfpyrG, AfpyroA are A. fumigatus riboB, pyrG, and pyroA genes, respectively (22), used for replacement of A. nidulans genes.

Fermentation and HPLC-DAD-MS analysis.

The A. nidulans deletion strains were cultivated at 37°C on YAG medium (solid complete medium; 5 g of yeast extract/liter, 15 g of agar/liter, and 20 g of d-glucose/liter supplemented with a 1 ml/liter trace element solution [29]) at 1.0 × 107 spores per 10-cm plate. After 5 days, the agar was chopped into small pieces, and the material was extracted with 50 ml of MeOH, followed by 50 ml of 1:1 CH2Cl2-MeOH, each with a 1-h sonication. The extract was evaporated in vacuo to yield a residue, which was suspended in H2O (25 ml), and this was then partitioned with ethyl acetate (EtOAc; two times with 25 ml each time). The combined EtOAc layer was evaporated in vacuo and redissolved in 1.5 ml of 20% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)-MeOH, and 10 μl was injected for HPLC-DAD-MS analysis.

For alcA(p)-inducing conditions, 5.0 × 107 spores were grown in 50 ml of liquid LMM medium (3) supplemented with pyridoxine (0.5 mg/liter), uracil (1 g/liter), and uridine (10 mM) at 37°C with shaking at 200 rpm. Cyclopentanone at a final concentration of 30 mM was added to the medium 18 h after inoculation. Culture medium was collected by filtration at 48 h or 72 h after cyclopentanone induction and extracted twice with 50 ml of EtOAc. The combined EtOAc layers were evaporated in vacuo and analyzed by HPLC-DAD-MS as described above.

HPLC-MS analysis was carried out using a ThermoFinnigan LCQ Advantage ion trap mass spectrometer with an RP C18 column (Alltech Prevail C18; particle size, 3 μm; column, 2.1 by 100 mm) at a flow rate of 125 μl/min. The solvent gradient system and the conditions for MS analysis were as described previously (3).

Isolation and identification of secondary metabolites.

For structure elucidation, 30 15-cm plates inoculated with A. nidulans strain LO2766 (nkuAΔ stcJΔ cclAΔ mdpHΔ) were grown for 5 days at 37°C and extracted with MeOH and 1:1 CH2Cl2-MeOH as described above. The extract was evaporated in vacuo to yield a residue, which was suspended in H2O (1 liter), and partitioned with ethyl acetate (1 liter; two times). In order to extract most of the acidic secondary metabolites, the water layer was further acidified to pH 2, followed by partitioning with ethyl acetate again (1 liter; two times). The total crude extract in the ethyl acetate layer (∼1.4 g) was applied to an Si gel column (Merck; 230 to 400 mesh ASTM; 40 by 115 mm) and eluted with CHCl3-MeOH mixtures of increasing polarity (fraction A, 1:0; fraction B, 49:1; fraction C, 19:1; fraction D, 9:1; fraction E, 9:1; fraction F, 7:3; all volumes are 500 ml). Fraction F (273.9 mg), which contained endocrocin (compound 9), was further purified by reverse phase HPLC (Phenomenex Luna 5-μm C18 [2]; 250 by 10 mm) with a flow rate of 5.0 ml/min and measured by a UV detector at 280 nm. The gradient system was MeCN (solvent B) in 5% MeCN-H2O (solvent A), both containing 0.05% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA). The gradient system was as follows: 20 to 30% solvent B from 0 to 15 min, 30 to 70% solvent B from 15 to 20 min, 70 to 100% solvent B from 20 to 21 min, 100% solvent B from 21 to 23 min, and 100 to 20% solvent B from 23 to 25 min, with reequilibration with 20% B from 25 to 28 min. Endocrocin (compound 9; 12.4 mg) was eluted at 19.6 min. Some impurities were further removed by using the same HPLC conditions with the following gradient system: 20 to 30% B from 0 to 5 min, 30 to 40% B from 5 to 16 min, 40 to 100% B from 16 to 20 min, 100% B from 20 to 22 min, and 100 to 20% B from 22 to 23 min, with reequilibration with 20% B from 23 to 26 min. Endocrocin (compound 9; 8.2 mg) was eluted at 15.1 min.

Compound identification.

Melting points were determined with a Yanagimoto micromelting point apparatus and are uncorrected. Infrared (IR) spectra were recorded on a Perkin-Elmer 983G spectrophotometer. 1H and 13C nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were collected on a Varian Mercury Plus 400 spectrometer.

Endocrocin (compound 9).

Orange needles; melting point (mp), >300; IR (ZnSe, cm−1): 3400 to 2800, 1718, 1676, 1620, 1256, 1206, 754. For UV and electrospray ionization (ESI)-MS spectra, see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material. For 1H and 13C NMR data, see Table S2 in the supplemental material.

RESULTS

Metabolite analysis of mdp cluster deletion strains.

We have previously reported that deletion of cclA in A. nidulans results in derepressing the monodictyphenone (mdp) gene cluster (3). This allowed us to determine that mdpG encodes a nonreduced polyketide synthase (NR-PKS) required for the synthesis of monodictyphenone (Fig. 1, compound 1), emodin (compound 2), and emodin derivatives (compounds 3 to 6). In addition to compounds 1 to 6, we report two new minor peaks, compounds 7 and 8 (Fig. 3; see also Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Compounds 7 and 8 have similar UV-visible (Vis) spectra to 2-hydroxyemodin (5) and 2-aminoemodin (6), respectively (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). This suggests that compounds 7 and 8 contain the same chromophore as compounds 5 and 6, respectively. In addition, the molecular masses of compounds 7 and 8 are 16 Da greater than the masses of compounds 5 and 6, respectively, suggesting that the methyl group on the anthraquinone ring is oxidized to hydroxymethylene so that the chromophores are maintained.

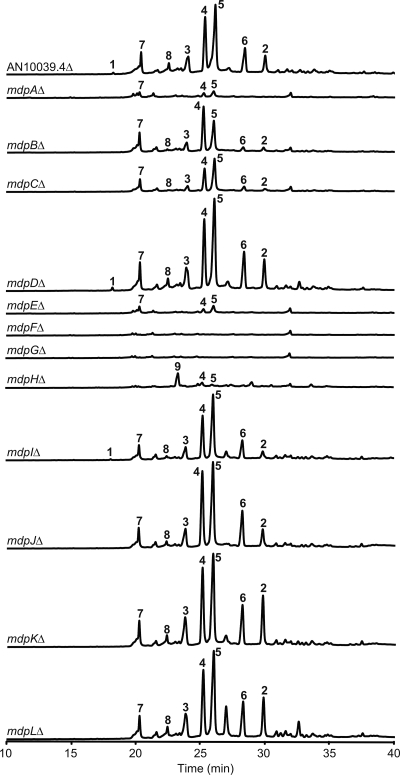

FIG. 3.

Metabolite profiles of mdp cluster gene deletions with UV at 276 nm. All strains carry nkuAΔ, stcJΔ, and cclAΔ. The y axis of each profile was at the same order of magnitude.

The monodictyphenone biosynthetic pathway has not been determined, and the cclAΔ mutant provides us with the opportunity to study the biosynthetic pathway for compounds 1 to 8. Since genes involved in biosynthesis of a particular metabolite are usually clustered in fungi, we deleted genes surrounding mdpG (Fig. 2; see also reference 3 for the putative function and closest homologs of genes AN10039.4 to AN0153.4) in an nkuAΔ stcJΔ cclAΔ background (Table 1, LO2051). nkuAΔ inhibits nonhomologous integration of transforming DNA fragments (22), and stcJΔ prevents the synthesis of sterigmatocystin, an abundant and toxic secondary metabolite (4). In nkuAΔ strains, approximately 90% of transformants carry a single homologous insertion (22).

Our first goal was to define the borders of this cluster. A previous analysis of putative gene function suggested that AN10039.4 and AN0153.4 were likely not to be involved in monodictyphenone biosynthesis (Fig. 2) (3). We attempted to delete AN0153.4 in several transformation experiments. We recovered multiple transformants in each experiment, but diagnostic PCR revealed that none carried a deletion of AN0153.4. Since our gene targeting system is extremely efficient (22) and since all other transformations efficiently produced the desired deletions, this suggests that AN0153.4 is essential. AN0153.4 encodes a putative 852-amino-acid (aa) protein which contains a Myb-like DNA binding domain that has high amino acid identity to telomeric repeat binding factor 1 (Tbf1) (as revealed by a BLAST search of the NCBI database). A tbf1 homologue (Pneumocystis carinii tbf1 [Pctbf1]) having high amino acid identity with AN0153.4 (E value, 1e−59) has been identified as an essential gene in Pneumocystis carinii (10). We conclude that AN0153.4 is almost certainly an essential gene that is not involved in monodictyphenone synthesis. AN0154.4, the next gene along the chromosome, is predicted to be a transcription factor IID and SAGA complex subunit and is unlikely to be a component of the monodictyphenone pathway. AN10023.4 (mdpL), on the other hand, was required for monodictyphenone (compound 1) synthesis (Fig. 3; see also Fig. S4 in the supplemental material) (Note that monodictyphenone is not particularly UV active and is revealed more clearly by electrostatic ion chromatography [EIC] at m/z 287 [Fig. S4] than UV at 276 nm, the maximum absorption of compound 1 [Fig. 3]). We conclude that one border of the mdp cluster is likely between mdpL and AN0154.4.

AN10039.4Δ strains produced monodictyphenone, emodin, and emodin derivatives (compounds 1 to 8) (Fig. 3; also Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). This result demonstrates that AN10039.4 is not required for the biosynthesis of these compounds. AN10021.4 (mdpA) is important for monodictyphenone biosynthesis (Fig. 3 and Fig. S4; see also discussion below), and these data, coupled with previous gene expression data (3), suggest that the other border of the mdp cluster is between mdpA and AN10039.4.

Our next step was to delete the genes mdpA to mdpL to assess removal of these genes on production of compounds 1 to 8. Deletion of each of three genes (mdpF, mdpA, and mdpE) gave a chemotype similar to that of the previously characterized mdpG mutants, i.e., little or no production of compounds 1 to 8. Deletion of mdpF, encoding a probable β-lactamase, eliminated production of any detectable amounts of compounds 1 to 8 (Fig. 3). This suggests that both MdpF and MdpG are involved in early steps of the emodin biosynthesis (see Fig. 5). The other two deletions that dramatically reduced production of compounds 1 to 8 were in mdpA and mdpE, genes with significant sequence identity to known fungal transcription factors. mdpE is similar to the aflatoxin zinc binuclear activator aflR, and mdpA is similar to the aflatoxin coactivator aflJ and several putative O-methyltransferases. The fact that deletion of either of these genes dramatically reduced production of compounds 1 to 8, coupled with their similarity to transcription factors involved in regulation of secondary metabolism, suggests strongly that both of these genes are involved in regulation of the mdp cluster. The fact that mdpAΔ and mdpEΔ did not completely eliminate production of several emodin derivatives, coupled with their similarity to aflR and aflJ, argues against an alternative, but less likely, possibility that these genes have an early catalytic function in the emodin/monodictyphenone biosynthetic pathway.

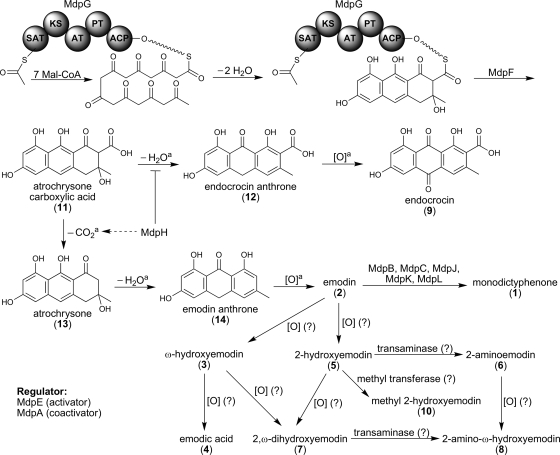

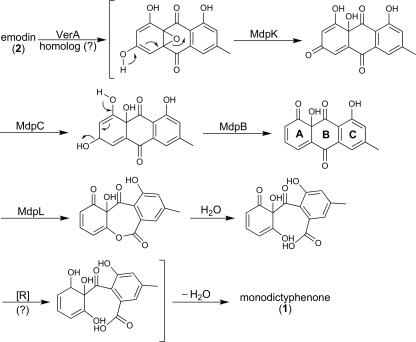

FIG. 5.

Biosynthesis pathway of monodictyphenone (1), emodin (2), and emodin analogs (3 to 10). The superscript “a” indicates that chemical reactions might occur spontaneously. SAT, starter unit ACP transacylase; KS, ketosynthase; AT, acyltransferase; PT, product template; ACP, acyl carrier protein.

Strains with deletions of mdpB, mdpC, mdpJ, mdpK, and mdpL produced compounds 2 to 8 but not monodictyphenone (compound 1) (Fig. 3; also Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). Thus, these genes are not required for synthesis of emodin and derivatives (compounds 2 to 8), but they appear to be required for monodictyphenone (compound 1) biosynthesis. Compounds 1 to 8 were produced in strains carrying deletions of mdpD (a flavin-containing monooxygenase) and mdpI (an acyl-coenzyme A [CoA] synthase). These genes, thus, are not required for the biosynthesis of monodictyphenone, emodin, or emodin derivatives (compounds 1 to 8). These results match our genetic analyses that showed coregulation of all mdp genes with the exception of mdpD and mdpI in the cclA deletion strain (3). Together, the results of our deletion analyses allow us to propose a biosynthetic pathway for compounds 1 to 8 (see Fig. 5).

Identification of a major UV active intermediate from the mdpH deletion strain.

Identification of key intermediates from the deletion strains should provide crucial clues for elucidating the biosynthesis pathway and predicting the function of the unknown proteins transcribed by the cluster. The mdpH deletion strain produced a major UV active metabolite (Fig. 3). This metabolite was purified from large-scale culture followed by extensive column chromatography. The structure was determined as endocrocin (compound 9) by NMR experiments as well as by comparison of the spectrum data with the literature (see Materials and Methods). Heteronuclear multiple-bond correlation (HMBC) also confirmed the assigned structure (see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material). Endocrocin (compound 9) is quite stable during the purification process at room temperature. Accumulation of compound 9 in the mdpH deletion strain but not in other deletion strains suggests that mdpH might encode a decarboxylase. mdpH has weak similarities to genes in both the sterigmatocystin pathway (StcM) (19) and the aflatoxin pathway (HypC and HypB) (9). The mdpH deletion strains still produced small, but detectable, amounts of emodin derivatives, suggesting that some spontaneous decarboxylation occurs or that other endogenous decarboxylases might also catalyze the same biotransformation with less efficiency (see Fig. 5).

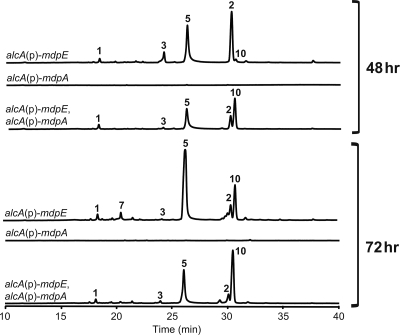

Induced expression of mdpE (a putative aflR homolog) but not mdpA (a putative aflJ homolog) can activate the mdp cluster.

AflR is a transcription factor that has been shown to be able to activate the transcription of sterigmatocystin biosynthetic genes and, thus, sterigmatocystin production (31). Our previous data also showed that inducing expression of mdpE (a putative aflR homolog) turns on monodictyphenone biosynthesis after 48 h of induction (3). It should be noted that a new metabolite (compound 10) that eluted after emodin (compound 2) started to accumulate after 72 h of mdpE induction (Fig. 4). It has a similar UV-Vis spectrum to 2-hydroxyemodin (compound 5) but with a molecular mass 14 Da greater than that of compound 5, suggesting that compound 10 is methyl 2-hydroxyemodin (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material).

FIG. 4.

Metabolite profiles of single alcA promoter [alcA(p)-mdpE or alcA(p)-mdpA] and dual alcA promoter [alcA(p)-mdpE alcA(p)-mdpA] strains after 30 mM cyclopentanone induction for 48 or 72 h. All strains carry nkuAΔ and stcJΔ. The y axis of each profile was at the same order of magnitude.

To see if expression of mdpA (a putative aflJ homolog) alone can activate the mdp cluster, we replaced the promoter of mdpA with the alcA inducible promoter. While induction of mdpE alone led to production mainly of compounds 2 and 5, induction of mdpA with cyclopentanone for 48 or 72 h did not produce any detectable amounts of compounds 1 to 10 (Fig. 4). This suggests that mdpA alone, unlike mdpE, is unable to activate monodictyphenone biosynthesis. AflR has been shown to interact with AflJ, a coactivator in the aflatoxin biosynthesis (6). These results, together with the fact that deletion of mdpA greatly reduced the production of emodin analogs, suggest that mdpA is normally important for turning on the mdp pathway and probably functions as a coactivator. Cyclopentanone induction of the alcA promoter results in high levels of expression (30), and it appears that high-level induction of mdpE partially overrides the requirement for MdpA as a coactivator.

An additional role for MdpA could be that of an O-methyltransferase. When both promoters of mdpE and mdpA were replaced with the alcA inducible promoter, the dual promoter strain produced a much larger amount of compound 10 than overexpression of mdpE alone after induction. A BLAST search revealed that MdpA shares substantial sequence identity with not only AflJ but also several putative O-methyltransferases, such as a putative O-methyltransferase from Penicillium marneffei (accession number XP_002149634; E value, 1e−93) and from Talaromyces stipitatus (XP-002482894; E value, 1e−72). Cyclopentanone induction of the alcA promoter results in high levels of expression (30). It is possible that MdpA has O-methyltransferase activity, and although normal expression of mdpA does not lead to significant accumulation of compound 10, the high levels of expression driven by the alcA promoter may result in enough production of MdpA to catalyze methylation of compound 5. If this is the case, it is not clear why compound 10 is produced, albeit in smaller amounts and at later times, in a strain overexpressing MdpE alone. Perhaps MdpE overexpression induces expression of MdpA or binds to and stabilizes MdpA.

DISCUSSION

Based on our data, we propose the following pathway for monodictyphenone biosynthesis. The monodictyphenone PKS, MdpG, catalyzes the formation of the octaketide. This enzyme contains the starter unit ACP transacylase (11), ketosynthase, acyltransferase, product template (12), and acyl carrier protein (ACP) domains, as is typical for an NR-PKS, but lacks a thioesterase (TE) domain (Fig. 5). BLAST analysis indicates that MdpF is a β-lactamase-like protein. We previously proposed that a β-lactamase-like protein might catalyze polyketide release from NR-PKS lacking a TE domain (27). This hypothesis has recently been demonstrated to be valid by Awakawa et al. (1). When atrochrysone carboxylic acid synthase (ACAS; a TE-less NR-PKS) and atrochrysone carboxyl ACP thioesterase (ACTE; a β-lactamase-like protein) were coincubated in the presence of malonyl-CoA, Awakawa et al. were able to detect emodin (Fig. 5, compound 2), endocrocin (compound 9), atrochrysone carboxylic acid (compound 11), endocrocin anthrone (compound 12), atrochrysone (compound 13), and emodin anthrone (compound 14) in vitro while no polyketide was detected with ACAS alone. This suggests that spontaneous dehydration or decarboxylation of compound 11 produces compound 12 or 13, respectively, due to the instability of compound 11. Further spontaneous dehydration of compound 13 yields compound 14, which auto-oxidizes to emodin (compound 2). This explains why decarboxylation occurs spontaneously from compounds 11 to 13 but not from compounds 9 to 2 since the β-keto group in compound 11 stabilizes the carbanion by enolate formation (Fig. 5). MdpH, thus, might function as a decarboxylase or dehydration retarder that facilitates the emodin (compound 2) biosynthesis pathway since mdpH deletion strains accumulate endocrocin (compound 9), an auto-oxidized product from emodin anthrone (compound 12). It is not surprising that mdpH deletion strains still produce small but detectable amounts of emodin derivatives, such as compounds 4 and 5 (Fig. 3), since compound 11 spontaneously convert to compound 2 that could be further processed by downstream enzymes. Interestingly, the only monooxygenase near the monodictyphenone PKS MdpG, MdpD, does not catalyze any oxidation step in the entire biosynthesis. Incubation of the cclA deletion strain with antioxidant (glutathione) or cell-permeable spin trap (N-tert-butyl-α-phenylnotrone) from 0.01 to 10 mM did not lead to emodin (compound 2) accumulation (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). This suggests that these oxidation processes are not simply mediated by the free radical. Mueller et al. (21) showed that the formation of ω-hydroxyemodin (compound 3) and 2-hydroxyemodin (compound 5) from emodin (compound 2) is cytochrome P450 dependent. More than 100 cytochrome P450 enzymes have been annotated in the A. nidulans genome (17), and this will provide the opportunity to identify the cytochromes that oxidize emodin (compound 2).

Our analyses indicated that at least five genes in the mdp cluster are involved in the biotransformation from emodin (compound 2) to monodictyphenone (compound 1). A similar biotransformation from versicolorin A to demethylsterigmatocystin has been studied by Henry and Townsend (15), who proposed an oxidation-reduction-oxidation mechanism mediated at least by one monooxygenase (AflN/VerA) and one ketoreductase (AflM/Ver-1) (see Fig. S7 in the supplemental material). Ehrlich et al. (13) and Cary et al. (5) further discovered that aflY/hypA and aflX/ordB might encode a Baeyer-Villiger oxidase and an oxidoreductase, respectively, which are also involved in the pathway. An NCBI nonredundant protein database BLAST search of the five genes involved in monodictyphenone biosynthesis (Table 2) revealed that MdpC has strong amino acid identity with versicolorin reductases, hydrosteroid dehydrogenases, and ketoreductases, including StcU (in the sterigmatocystin cluster) in A. nidulans and AflM/Ver-1 in the aflatoxin cluster of Aspergillus flavus. Based on sequence identity and position in the genome, J. Clutterbuck has speculated that mdpC or mdpB might be the chartreuse conidial color gene (http://www.cadre-genomes.org.uk/Aspergillus_nidulans/geneview?gene=AN0146.4). We did not find that deletions of either gene caused chartreuse conidia, but we did find that spores were slightly altered in color, displaying a slightly blue tint after several days of incubation. MdpK has strong similarity to NAD-dependent epimerases/dehydratases and oxygenases including AflX/OrdB of A. flavus and StcQ of A. nidulans. MdpL is closely related to AflY/HypA of A. flavus, which is involved in aflatoxin production, and to the A. nidulans homolog StcR. MdpB has strong sequence similarity with Bipolaris oryzate Scd1, a scytalone dehydratase involved in melanin biosynthesis (18) and, thus, might facilitate dehydration after ketone reduction by MdpC (Fig. 6). BLAST analysis with MdpJ shows that it is similar to two classes of proteins, including translation elongation factors (EFs) and glutathione S-transferases (GSTs). Although there is closer similarity to EFs, the proposed size of MdpJ is identical to that of GSTs but only one-half the size of EFs. However, it is still not clear of how MdpJ is involved in the pathway although we note deletion of its homolog, stcT in the sterigmatocystin cluster, reduces sterigmatocystin production (19). A putative homolog (DS31) is also found in the dothistromin cluster of the forest pathogen Dothistroma septosporum, but its function is unknown in this fungus (32). Interestingly, the fact that there is no verA homolog among these five genes suggests that another gene, not present in the mdp cluster, might catalyze the epoxidation (Fig. 6). However, how the carbonyl group is reduced to a hydroxyl group followed by dehydration in the last two steps of monodictyphenone formation is unclear. The facts that there is no verA homolog in the mdp cluster and that there is a low yield of monodictyphenone (compound 1) might suggest that compound 1 is not the final metabolite but a shunt product. It is thus possible that another gene cluster at a different location might work together with the mdp cluster to synthesize another secondary metabolite. It should be noted that in the Baeyer-Villiger oxidation, the migrating group is an electron-rich group (see Fig. S7 in the supplemental material) (15). Why the A ring but not the C ring migrates to the oxygen is still unknown (Fig. 6).

TABLE 2.

Gene identities in the monodictyphenone cluster

| Gene | Predicted no. of amino acids encoded | Putative homolog(s) (accession no.)a | % Identity/% similarity |

|---|---|---|---|

| mdpB | 214 | Scd1 (BAC79365) | 54/70 |

| mdpC | 265 | AflM/Ver-1 (P50161) | 66/80 |

| mdpJ | 210 | GST (P30102) | 31/47 |

| mdpK | 265 | AflX/OrdB (AAS90016) | 45/64 |

| mdpL | 446 | AflY/HypA (AAS90020) | 32/51 |

Closest protein with published function(s) found in a BLAST search of the NCBI nonredundant database.

FIG. 6.

Proposed biosynthetic pathway of monodictyphenone (1) from emodin (2).

In conclusion, we have deduced the monodictyphenone and emodin analog biosynthesis pathway by creating targeted deletions in a loss-of-function A. nidulans cclA mutant and analyzing the metabolite profiles of the deletion strains. This should enable us to create and isolate emodin, a compound of pharmaceutical interest (26), including novel derivatives, using molecular genetic and chemical approaches or a combination of both. Finally, our data confirm the value of targeting epigenetic regulation to induce cryptic gene clusters for secondary metabolite biosynthesis, allowing us to discover new treasures from microorganisms.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by grants PO1GM084077 and R01GM031837 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of General Medical Sciences or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 5 February 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Awakawa, T., K. Yokota, N. Funa, F. Doi, N. Mori, H. Watanabe, and S. Horinouchi. 2009. Physically discrete beta-lactamase-type thioesterase catalyzes product release in atrochrysone synthesis by iterative type I polyketide synthase. Chem. Biol. 16:613-623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergmann, S., J. Schumann, K. Scherlach, C. Lange, A. A. Brakhage, and C. Hertweck. 2007. Genomics-driven discovery of PKS-NRPS hybrid metabolites from Aspergillus nidulans. Nat. Chem. Biol. 3:213-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bok, J. W., Y. M. Chiang, E. Szewczyk, Y. Reyes-Domingez, A. D. Davidson, J. F. Sanchez, H. C. Lo, K. Watanabe, J. Strauss, B. R. Oakley, C. C. Wang, and N. P. Keller. 2009. Chromatin-level regulation of biosynthetic gene clusters. Nat. Chem. Biol. 5:462-464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown, D. W., J. H. Yu, H. S. Kelkar, M. Fernandes, T. C. Nesbitt, N. P. Keller, T. H. Adams, and T. J. Leonard. 1996. Twenty-five coregulated transcripts define a sterigmatocystin gene cluster in Aspergillus nidulans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93:1418-1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cary, J. W., K. C. Ehrlich, J. M. Bland, and B. G. Montalbano. 2006. The aflatoxin biosynthesis cluster gene, aflX, encodes an oxidoreductase involved in conversion of versicolorin A to demethylsterigmatocystin. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:1096-1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang, P. K. 2003. The Aspergillus parasiticus protein AFLJ interacts with the aflatoxin pathway-specific regulator AFLR. Mol. Genet. Genomics 268:711-719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiang, Y. M., E. Szewczyk, A. D. Davidson, N. Keller, B. R. Oakley, and C. C. Wang. 2009. A gene cluster containing two fungal polyketide synthases encodes the biosynthetic pathway for a polyketide, asperfuranone, in Aspergillus nidulans. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131:2965-2970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiang, Y. M., E. Szewczyk, T. Nayak, A. D. Davidson, J. F. Sanchez, H. C. Lo, W. Y. Ho, H. Simityan, E. Kuo, A. Praseuth, K. Watanabe, B. R. Oakley, and C. C. Wang. 2008. Molecular genetic mining of the Aspergillus secondary metabolome: discovery of the emericellamide biosynthetic pathway. Chem. Biol. 15:527-532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cleveland, T. E., J. Yu, N. Fedorova, D. Bhatnagar, G. A. Payne, W. C. Nierman, and J. W. Bennett. 2009. Potential of Aspergillus flavus genomics for applications in biotechnology. Trends Biotechnol. 27:151-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cockell, M. M., L. Lo Presti, L. Cerutti, E. Cano Del Rosario, P. M. Hauser, and V. Simanis. 2009. Functional differentiation of tbf1 orthologues in fission and budding yeasts. Eukaryot. Cell 8:207-216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crawford, J. M., B. C. Dancy, E. A. Hill, D. W. Udwary, and C. A. Townsend. 2006. Identification of a starter unit acyl-carrier protein transacylase domain in an iterative type I polyketide synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:16728-16733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crawford, J. M., P. M. Thomas, J. R. Scheerer, A. L. Vagstad, N. L. Kelleher, and C. A. Townsend. 2008. Deconstruction of iterative multidomain polyketide synthase function. Science 320:243-246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ehrlich, K. C., B. Montalbano, S. M. Boue, and D. Bhatnagar. 2005. An aflatoxin biosynthesis cluster gene encodes a novel oxidase required for conversion of versicolorin A to sterigmatocystin. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:8963-8965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galagan, J. E., S. E. Calvo, C. Cuomo, L. J. Ma, J. R. Wortman, S. Batzoglou, S. I. Lee, M. Basturkmen, C. C. Spevak, J. Clutterbuck, V. Kapitonov, J. Jurka, C. Scazzocchio, M. Farman, J. Butler, S. Purcell, S. Harris, G. H. Braus, O. Draht, S. Busch, C. D'Enfert, C. Bouchier, G. H. Goldman, D. Bell-Pedersen, S. Griffiths-Jones, J. H. Doonan, J. Yu, K. Vienken, A. Pain, M. Freitag, E. U. Selker, D. B. Archer, M. A. Penalva, B. R. Oakley, M. Momany, T. Tanaka, T. Kumagai, K. Asai, M. Machida, W. C. Nierman, D. W. Denning, M. Caddick, M. Hynes, M. Paoletti, R. Fischer, B. Miller, P. Dyer, M. S. Sachs, S. A. Osmani, and B. W. Birren. 2005. Sequencing of Aspergillus nidulans and comparative analysis with A. fumigatus and A. oryzae. Nature 438:1105-1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henry, K. M., and C. A. Townsend. 2005. Ordering the reductive and cytochrome P450 oxidative steps in demethylsterigmatocystin formation yields general insights into the biosynthesis of aflatoxin and related fungal metabolites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127:3724-3733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keller, N. P., G. Turner, and J. W. Bennett. 2005. Fungal secondary metabolism—from biochemistry to genomics. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:937-947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelly, D. E., N. Krasevec, J. Mullins, and D. R. Nelson. 2009. The CYPome (cytochrome P450 complement) of Aspergillus nidulans. Fungal Genet. Biol. 46(Suppl. 1):S53-S61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kihara, J., A. Moriwaki, M. Ueno, T. Tokunaga, S. Arase, and Y. Honda. 2004. Cloning, functional analysis and expression of a scytalone dehydratase gene (SCD1) involved in melanin biosynthesis of the phytopathogenic fungus Bipolaris oryzae. Curr. Genet. 45:197-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McDonald, T., D. Noordermeer, Y. Q. Zhang, T. Hammond, and N. P. Keller. 2005. The sterigmatocystin cluster revisited: lessons from a genetic model, p. 117-136. In H. K. Abbas (ed.), Aflatoxin and food safety. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

- 20.Mueller, J. E., M. Canze, and M. Bryk. 2006. The requirements for COMPASS and Paf1 in transcriptional silencing and methylation of histone H3 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 173:557-567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mueller, S. O., H. Stopper, and W. Dekant. 1998. Biotransformation of the anthraquinones emodin and chrysophanol by cytochrome P450 enzymes. Bioactivation to genotoxic metabolites. Drug Metab. Dispos. 26:540-546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nayak, T., E. Szewczyk, C. E. Oakley, A. Osmani, L. Ukil, S. L. Murray, M. J. Hynes, S. A. Osmani, and B. R. Oakley. 2006. A versatile and efficient gene-targeting system for Aspergillus nidulans. Genetics 172:1557-1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schroeckh, V., K. Scherlach, H. W. Nutzmann, E. Shelest, W. Schmidt-Heck, J. Schuemann, K. Martin, C. Hertweck, and A. A. Brakhage. 2009. Intimate bacterial-fungal interaction triggers biosynthesis of archetypal polyketides in Aspergillus nidulans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:14558-14563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shwab, E. K., J. W. Bok, M. Tribus, J. Galehr, S. Graessle, and N. P. Keller. 2007. Histone deacetylase activity regulates chemical diversity in Aspergillus. Eukaryot. Cell 6:1656-1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sims, R. J., III, and D. Reinberg. 2006. Histone H3 Lys 4 methylation: caught in a bind? Genes Dev. 20:2779-2786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Srinivas, G., S. Babykutty, P. P. Sathiadevan, and P. Srinivas. 2007. Molecular mechanism of emodin action: transition from laxative ingredient to an antitumor agent. Med. Res. Rev. 27:591-608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Szewczyk, E., Y. M. Chiang, C. E. Oakley, A. D. Davidson, C. C. Wang, and B. R. Oakley. 2008. Identification and characterization of the asperthecin gene cluster of Aspergillus nidulans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:7607-7612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Szewczyk, E., T. Nayak, C. E. Oakley, H. Edgerton, Y. Xiong, N. Taheri-Talesh, S. A. Osmani, and B. R. Oakley. 2006. Fusion PCR and gene targeting in Aspergillus nidulans. Nat. Protoc. 1:3111-3120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vishniac, W., and M. Santer. 1957. The thiobacilli. Bacteriol. Rev. 21:195-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Waring, R. B., G. S. May, and N. R. Morris. 1989. Characterization of an inducible expression system in Aspergillus nidulans using alcA and tubulin-coding genes. Gene 79:119-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu, J. H., R. A. Butchko, M. Fernandes, N. P. Keller, T. J. Leonard, and T. H. Adams. 1996. Conservation of structure and function of the aflatoxin regulatory gene aflR from Aspergillus nidulans and A. flavus. Curr. Genet. 29:549-555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang, S., A. Schwelm, H. Jin, L. J. Collins, and R. E. Bradshaw. 2007. A fragmented aflatoxin-like gene cluster in the forest pathogen Dothistroma septosporum. Fungal Genet. Biol. 44:1342-1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.