Abstract

The purpose of the present study was to investigate the inhibition of Vibrio by Roseobacter in a combined liquid-surface system. Exposure of Vibrio anguillarum to surface-attached roseobacters (107 CFU/cm2) resulted in significant reduction or complete killing of the pathogen inoculated at 102 to 104 CFU/ml. The effect was likely associated with the production of tropodithietic acid (TDA), as a TDA-negative mutant did not affect survival or growth of V. anguillarum.

Antagonistic interactions among marine bacteria are well documented, and secretion of antagonistic compounds is common among bacteria that colonize particles or surfaces (8, 13, 16, 21, 31). These marine bacteria may be interesting as sources for new antimicrobial drugs or as probiotic bacteria for aquaculture.

Aquaculture is a rapidly growing sector, but outbreaks of bacterial diseases are a limiting factor and pose a threat, especially to young fish and invertebrates that cannot be vaccinated. Because regular or prophylactic administration of antibiotics must be avoided, probiotic bacteria are considered an alternative (9, 18, 34, 38, 39, 40). Several microorganisms have been able to reduce bacterial diseases in challenge trials with fish or fish larvae (14, 24, 25, 27, 33, 37, 39, 40). One example is Phaeobacter strain 27-4 (17), which inhibits Vibrio anguillarum and reduces mortality in turbot larvae (27). The antagonism of Phaeobacter 27-4 and the closely related Phaeobacter inhibens is due mainly to the sulfur-containing tropolone derivative tropodithietic acid (TDA) (2, 5), which is also produced by other Phaeobacter strains and Ruegeria mobilis (28). Phaeobacter and Ruegeria strains or their DNA has been commonly found in marine larva-rearing sites (6, 17, 28).

Phaeobacter and Ruegeria (Alphaproteobacteria, Roseobacter clade) are efficient surface colonizers (7, 11, 31, 36). They are abundant in coastal and eutrophic zones and are often associated with algae (3, 7, 41). Surface-attached Phaeobacter bacteria may play an important role in determining the species composition of an emerging biofilm, as even low densities of attached Phaeobacter strain SK2.10 bacteria can prevent other marine organisms from colonizing solid surfaces (30, 32).

In continuation of the previous research on roseobacters as aquaculture probiotics, the purpose of this study was to determine the antagonistic potential of Phaeobacter and Ruegeria against Vibrio anguillarum in liquid systems that mimic a larva-rearing environment. Since production of TDA in liquid marine broth appears to be highest when roseobacters form an air-liquid biofilm (5), we addressed whether they could be applied as biofilms on solid surfaces.

Attachment of roseobacters to surfaces.

Phaeobacter 27-4 was isolated from a Spanish turbot hatchery due to its ability to inhibit Vibrio anguillarum (17). Phaeobacter strain JBB1001 is a tdaB mutant of Phaeobacter 27-4 and thus unable to produce TDA (12). Phaeobacter strain M23-3.1 and Ruegeria strain M43-2.3 were isolated from a Danish turbot hatchery due to their anti-Vibrio activity (28).

Precultures of roseobacters were grown at 25°C as stagnant batch cultures in 10 ml marine broth (MB; Difco catalog no. 2216) in 100-ml glass bottles for 1 day. Two additional media were used in this study: artificial seawater (IO) (30 g/liter Instant Ocean sea salts; Aquarium Systems, Inc., Sarrebourg, France) and IO supplemented with 4 g/liter d-glucose and 3.5 g/liter amino acids (Bacto product no. 223050 [Casamino Acids]) (IO+).

Five microliters of Roseobacter precultures was inoculated into 195 μl MB or IO+ in each well of an Innovotech polystyrene MBEC (minimum biofilm eradication concentration) assay plate (35). The pegs of the plates were placed in the culture and incubated stagnant at 25°C for 4 days to create a biofilm. For controls, pegs were incubated in sterile MB or IO+. For quantification of bacteria in the biofilms, the pegs were cut off, transferred to 2 ml IO in a 5-ml polystyrene test tube, ultrasonicated for 4 min at 28 kHz (19), vortexed for 30 s, and serially diluted, and the bacteria were plate counted on marine agar (MA). Before the bacteria were plated, it was determined by microscopy that mainly single cells were present. Testing the sonication procedure on liquid cultures demonstrated that roseobacter numbers were not reduced and more than 98% of the adherent bacteria were removed from the peg. The pegs of the MBEC plates were reproducibly overgrown by a monolayer biofilm of 106 to 107 CFU/peg, and no difference in surface growth between the strains was noted.

Antagonism against V. anguillarum by attached roseobacters.

V. anguillarum serotype O1 strain NB10 has caused disease in rainbow trout and was gfp tagged by insertion of plasmid pNQFlaC4-gfp27 (cat, gfp) into an intergenic region of the chromosome (10, 26) (kindly provided by D. Milton, University of Umeå). The sensitivity of this strain to roseobacter culture supernatants was the same as that of the wild type (data not shown). For enumeration of vibrios, tryptic soy agar (TSA; Oxoid product no. CM0131) containing 4 μg/ml chloramphenicol (TSA chl4) was used. Roseobacters were counted on MA as brown-pigmented colonies.

The MBEC lids with attached roseobacters (see above) were transferred to 96-well plates containing V. anguillarum NB10 in different initial concentrations and media. Biofilms grown in MB or IO+ were transferred to MB, IO+, or IO. Positive controls contained the same concentrations of V. anguillarum, but no roseobacters were introduced. Negative controls were sterile medium and pegs. After 3 days of incubation at 25°C, the surviving vibrios were counted. Vibrios were considered absent if no growth was observed after plating 100 μl of pure culture liquid on TSA chl4. All experiments were done in duplicate and were repeated independently, so average values and standard deviations are based on four determinations. Bacterial counts were log transformed before statistical analysis. Significant differences were identified using analysis of variance (Systat 11; α = 0.05).

In all the MB and IO+ controls, V. anguillarum grew to 108 to 109 CFU/ml in 3 days, and in the IO controls to 103 to 106 CFU/ml, depending on the inoculum size (Tables 1 and 2). In contrast, when exposed to pegs with Phaeobacter M23-3.1 or Ruegeria M43-2.3 biofilms, V. anguillarum was killed after 3 days in most experiments (Table 1). Phaeobacter M23-3.1 completely killed V. anguillarum in all media and in every well sampled. A similar effect was seen with Ruegeria M43-2.3 cocultures, except in MB, where low numbers of V. anguillarum survived independently of the preculture medium.

TABLE 1.

Cell densities of V. anguillarum bacteria after 4 days of exposure to Roseobacter clade strainsa

| Preculture medium | Attached strain | Log CFU/ml (mean ± SD) of V. anguillarum after 4 days of exposure in: |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MB | IO+ | IO | ||

| MB | None | 8.7 ± 0.32 | 8.3 ± 0.21 | 3.4 ± 0.28 |

| Phaeobacter 27-4 | 3.0 ± 1.18 | 7.7 ± 1.05 | 1.0 ± 0.07 | |

| Phaeobacter JBB1001 | 7.8 ± 0.63 | 8.5 ± 0.07 | 4.3 ± 0.42 | |

| Phaeobacter M23-3.1 | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 | |

| Ruegeria M43-2.3 | 3.0 ± 0.16 | <1.0 | <1.0 | |

| IO+ | None | 8.5 ± 0.23 | 8.1 ± 0.24 | 3.0 ± 1.03 |

| Phaeobacter 27-4 | 6.1 ± 1.15 | 6.1 ± 0.98 | 4.4 ± 0.81 | |

| Phaeobacter JBB1001 | 7.7 ± 0.12 | 8.4 ± 0.17 | 3.9 ± 0.59 | |

| Phaeobacter M23-3.1 | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 | |

| Ruegeria M43-2.3 | 3.4 ± 0.16 | <1.0 | <1.0 | |

Strains were precultured as surface-attached bacteria in MBEC plates, in either marine broth (MB) or Instant Ocean salts solution with Casamino Acids and glucose (IO+). Exposure occurred in MB, IO+, or IO salts solution. All combinations were tested in duplicate in two independent trials (four replicates), except for M43-2.3, which was tested in only one trial in duplicate. Initial numbers of V. anguillarum were 4 × 102 to 8 × 102 CFU/ml.

TABLE 2.

Cell density of V. anguillarum exposed to surface-attached Phaeobacter M23-3.1 or Ruegeria M43-2.3 cultured in MBa

| Attached strain | Initial Vibrio density (CFU/ml) | Log CFU/ml (mean ± SD) of V. anguillarum after 4 days of exposure in: |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MB | IO+ | IO | ||

| None | 6 × 102 | 8.77 ± 0.28 | 8.54 ± 0.20 | 4.33 ± 0.31 |

| 6 × 103 | 9.17 ± 0.13 | 8.87 ± 0.71 | 4.79 ± 0.18 | |

| 6 × 104 | 8.8 ± 0.12 | 8.52 ± 0.63 | 4.95 ± 0.59 | |

| 6 × 105 | 8.91 ± 0.06 | 8.57 ± 0.04 | 5.79 ± 0.30 | |

| Phaeobacter M23-3.1 | 6 × 102 | 1.12 ± 0.24 | <1.0 | <1.0 |

| 6 × 103 | 3.28 ± 2.63 | <1.0 | <1.0 | |

| 6 × 104 | 6.80 ± 1.73 | <1.0 | <1.0 | |

| 6 × 105 | 6.01 ± 0.38 | <1.0 | 1.68 ± 0.80 | |

| Ruegeria M43-2.3 | 6 × 102 | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 |

| 6 × 103 | 4.60 ± 0.77 | 1.19 ± 0.39 | <1.0 | |

| 6 × 104 | 6.48 ± 0.97 | <1.0 | <1.0 | |

| 6 × 105 | 5.11 ± 0.61 | 3.06 ± 1.64 | 1.37 ± 0.74 | |

Different initial densities of V. anguillarum from 6 × 102 to 6 × 105 CFU/ml were exposed to Phaeobacter in MB, IO+, or IO. Log numbers are averages of quadruplicate determinations.

Phaeobacter 27-4 biofilms that were precultured in MB reduced the numbers of V. anguillarum CFU in MB (P < 0.001) and IO (P < 0.001) but not in IO+ (P = 0.246). When Phaeobacter 27-4 was precultured in IO+, a weaker antagonistic effect in MB (P = 0.006) and IO+ (P = 0.007) cocultures was seen. In pure artificial seawater (IO), no reduction in Vibrio numbers was observed (Table 1). The TDA-deficient Phaeobacter JBB1001 biofilms did not affect Vibrio numbers (Table 1).

We also investigated whether the initial concentration of V. anguillarum NB10 would affect the inhibitory effect of Phaeobacter M23-3.1 and Ruegeria M43-2.3 biofilms, as the low number of vibrios in the inocula (102 to 103 CFU/ml) in the first experiment were completely killed. Biofilms were precultured in MB, and V. anguillarum was suspended in MB, IO+, or IO for coculture. Initial Vibrio concentrations ranged from 6 × 102 to 6 × 105 CFU/ml.

In MB, both Roseobacter strains failed to completely eradicate the pathogen, except with the lowest Vibrio inoculum (Table 2). But Phaeobacter M23-3.1 caused the complete elimination of V. anguillarum in IO and IO+, except with the highest Vibrio inoculum, where low numbers of vibrios survived in two out of four replicates. Also, Ruegeria M43-2.3 generally killed V. anguillarum in IO and IO+, although some vibrios in cultures with the highest inoculum survived.

Vibrio anguillarum killing kinetics.

We conducted a trial in which V. anguillarum bacteria exposed to surface-attached Phaeobacter M23-3.1 were sampled after 24, 48, and 72 h and another trial with sampling after 2, 4, 7, and 24 h. In the latter experiment, we also addressed exposure to planktonic Phaeobacter M23-3.1, grown in MB for 4 days, using the same initial cell numbers as when providing the peg surface-attached bacteria. Experiments were done in duplicate and repeated independently.

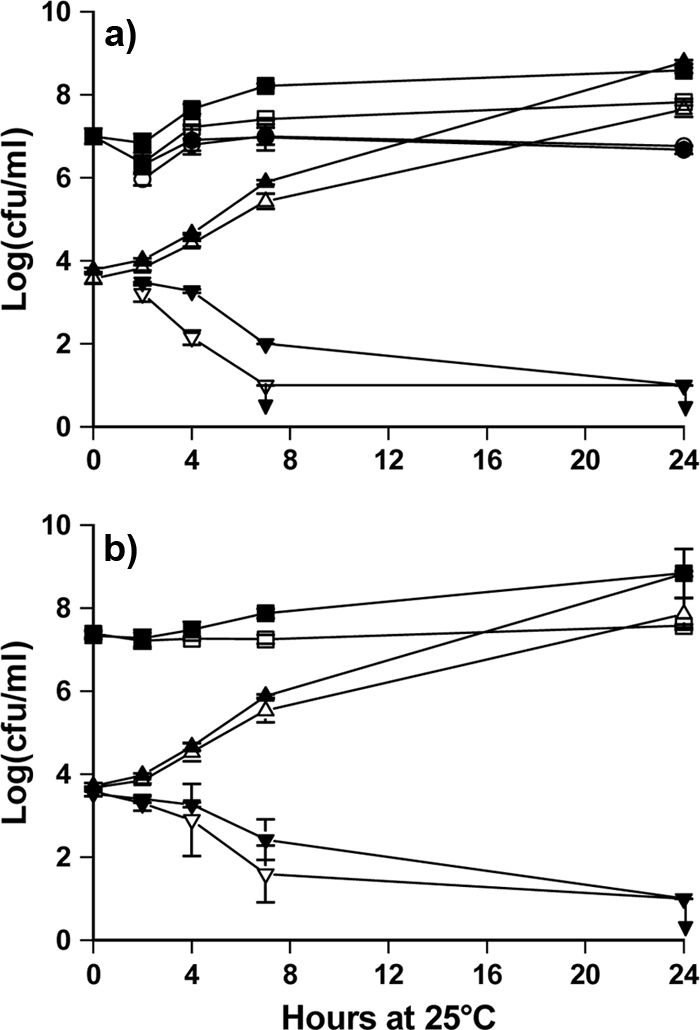

V. anguillarum grew from 103 to 104 CFU/ml to 108 to 109 CFU/ml in 24 h in control vials, but when the bacteria were exposed to Phaeobacter M23-3.1, counts decreased during the first 4 h and no cells were detectable after 24 h (Fig. 1a). Phaeobacter M23-3.1 numbers on the peg surface remained at 107 CFU/peg, whereas the number of dispersed cells reached 108 to 109 CFU/ml in 24 h. The addition of Phaeobacter as suspended cells resulted in a similar, albeit slightly slower, killing of V. anguillarum (Fig. 1b).

FIG. 1.

Vibrio anguillarum was exposed to Phaeobacter sp. M23-3.1 introduced as attached cells on pegs (a) or as suspended cells (b). Counts of V. anguillarum CFU exposed to Phaeobacter in MB (▾) and in IO+ (▿); negative controls were unexposed V. anguillarum CFU in MB (▴) and in IO+ (▵). Growth of Phaeobacter was measured in culture liquid (MB ▪, IO+ ) and on the pegs (MB •, IO+ ○). Points are averages of four determinations (duplicates in two independent trials), and error bars are standard deviations of the mean.

TDA quantification by high-pressure liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry.

TDA concentrations in MB culture supernatants of all strains grown in microtiter plates with and without pegs for 3 days were compared by high-pressure liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry using the semiquantitative method described by Porsby et al. (28).

Each strain produced about the same amount of TDA with and without pegs. For Phaeobacter 27-4, the peak area was approximately 10,000 to 12,000 counts, whereas the counts were 33,000 to 36,000 for Ruegeria M43-2.3, 66,000 to 80,000 for Phaeobacter M23-3.1, and 0 for Phaeobacter JBB1001.

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrate that roseobacters are capable of killing the fish pathogen V. anguillarum in model systems mimicking a fish larval aquaculture environment and that they can be applied as attached bacteria on solid surfaces. TDA appeared to be the essential compound, since the TDA-negative mutant was not effective, and antagonistic efficiency was correlated to TDA production in MB. Introduction of suspended roseobacters also resulted in elimination of the pathogen.

The antagonism of Phaeobacter spp. and Ruegeria mobilis against V. anguillarum in agar-based assays is a known phenomenon (2, 5, 17, 28, 29, 31); however, this interaction has not been demonstrated in a seawater-based system, representing a better model of the aquaculture environment. Studies of roseobacters as probiotics have focused on Phaeobacter 27-4 (4, 5, 17, 27), which seems to be more demanding regarding conditions for TDA production. While strain 27-4 requires stagnant conditions to produce TDA in MB, Phaeobacter M23-3.1 produces TDA under both stagnant and shaken conditions (28) and in larger amounts. It also exerted the strongest killing of V. anguillarum and may be a more potent fish probiont.

Both Phaeobacter and Ruegeria spp. are effective against other fish-pathogenic bacteria (29), and we have demonstrated similar activity against a broad spectrum of common fish pathogens (V. anguillarum O1, O2, and O2b, Vibrio vulnificus O2, Vibrio splendidus, Vibrio harveyi, Aeromonas salmonicida, Tenacibaculum maritimum, Lactococcus piscium) (unpublished results). This emphasizes the potential of roseobacters as aquaculture probionts.

Phaeobacter 27-4 does not harm turbot larvae (5, 17, 27), and we have recently found that M43-2.3 and M23-3.1 have no adverse effects on cod larvae (Øivind Bergh, Institute of Marine Research, Norway, unpublished data). Toxic effects of Phaeobacter spp. toward microalgae, as reported by Liang (20), could not be confirmed by exposure of algae to Phaeobacter cells or supernatant, but purified TDA at a concentration as high as 1 mM resulted in moderate inhibition of two species of diatoms (2, 30).

A low number of surface-attached Phaeobacter SK2.10 cells can prevent the attachment of marine biofilm-forming bacteria (30), but the cause of this deterrence has not been elucidated. Our study demonstrates that V. anguillarum is killed by Phaeobacter and Ruegeria biofilms and indicates that TDA is probably responsible for this effect. The genome of Phaeobacter SK2.10 (www.roseobase.org) contains genes essential for TDA production (tdaA to tdaF) (12), and we have detected TDA in Phaeobacter SK2.10 cultures (unpublished data). It could be TDA that had the deterrent effect observed by Rao et al. (30), but other compounds could also be involved. Production of a different antibacterial compound by Phaeobacter strain Y41, which is closely related to Phaeobacter SK2.10, has been reported (36).

Besides factors such as a higher growth rate, motility, or production of antagonizing substances (23), the outcome of a competition may also be influenced by the initial concentrations of the competing strains. Attached Phaeobacter SK2.10 cells at and above 104 CFU/cm2 were a deterrent to other marine bacteria added at densities of 106 CFU/ml (30). Our setup did not allow manipulation of the number of attached cells (approximately 107 CFU/cm2), but we varied the exposed V. anguillarum density from 102 to 106 CFU/ml. Assuming the same mechanisms of interaction in the two setups, we would expect that a lower initial number of roseobacters could also have a detrimental effect on V. anguillarum. Antagonistic Roseobacter biofilms might prevent establishment and proliferation of opportunistic pathogens on a small scale and thus reduce their presence in the system, even if TDA concentrations in the water were too low to kill the pathogen.

Only a few actual field trials of bacterial antagonism against fish pathogens have been conducted (24, 25), as the need for repeated introduction of high densities of the probiotic culture is a major obstacle. Our findings that roseobacters can exert their antipathogen effect when introduced as surface-attached organisms and that already low initial levels are effective are promising in this respect. Biofilters are used in many aquaculture settings (1) and could potentially harbor probiotic bacteria (15). Also, the common association between roseobacters and algae (3, 7, 22, 41) indicates that algae or rotifer cultures could harbor symbiotic roseobacters. Our study indicates that this would be an interesting avenue of future fish probiotic research and development.

Acknowledgments

This study was made possible by an examination grant from the German Academic Exchange Service DAAD to Paul W. D'Alvise. Support was also provided by the Danish Research Council for Technology and Production for Cisse H. Porsby.

We thank Debra Milton, Umeå University, for providing V. anguillarum NB10/pNQFlaC4-gfp27 and Øivind Bergh, Institute of Marine Research, Bergen, Norway, for sharing unpublished data on infection trials with strains M43-2.3 and M23-3.1.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 29 January 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Borges, M.-T., A. Morais, and P. M. L. Castro. 2003. Performance of outdoor seawater treatment systems for recirculation in an intensive turbot (Scophthalmus maximus) farm. Aquacult. Int. 11:557-570. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brinkhoff, T., G. Bach, T. Heidorn, L. Liang, A. Schlingloff, and M. Simon. 2004. Antibiotic production by a Roseobacter clade-affiliated species from the German Wadden Sea and its antagonistic effects on indigenous isolates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:2560-2565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brinkhoff, T., H. A. Giebel, and M. Simon. 2008. Diversity, ecology, and genomics of the Roseobacter clade: a short overview. Arch. Microbiol. 189:531-539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruhn, J. B., L. Gram, and R. Belas. 2007. Production of antibacterial compounds and biofilm formation by Roseobacter species are influenced by culture conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:442-450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruhn, J. B., K. F. Nielsen, M. Hjelm, M. Hansen, J. Bresciani, S. Schulz, and L. Gram. 2005. Ecology, inhibitory activity, and morphogenesis of a marine antagonistic bacterium belonging to the Roseobacter clade. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:7263-7270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brunvold, L., R. A. Sandaa, H. Mikkelsen, E. Welde, H. Bleie, and O. Bergh. 2007. Characterisation of bacterial communities associated with early stages of intensively reared cod (Gadus morhua) using denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE). Aquaculture 272:319-327. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buchan, A., J. M. González, and M. A. Moran. 2005. Overview of the marine Roseobacter lineage. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:5665-5677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burgess, J. G., E. M. Jordan, M. Bregu, A. Mearns-Spragg, and K. G. Boyd. 1999. Microbial antagonism: a neglected avenue of natural products research. J. Biotechnol. 70:27-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cabello, F. C. 2006. Heavy use of prophylactic antibiotics in aquaculture: a growing problem for human and animal health and for the environment. Environ. Microbiol. 8:1137-1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Croxatto, A., J. Lauritz, C. Chen, and D. L. Milton. 2007. Vibrio anguillarum colonization of rainbow trout integument requires a DNA locus involved in exopolysaccharide transport and biosynthesis. Environ. Microbiol. 9:370-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dang, H., and C. R. Lovell. 2000. Bacterial primary colonization and early succession on surfaces in marine waters as determined by amplified rRNA gene restriction analysis and sequence analysis of 16S rRNA genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:467-475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geng, H., J. B. Bruhn, K. F. Nielsen, L. Gram, and R. Belas. 2008. Genetic dissection of tropodithietic acid biosynthesis by marine roseobacters. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:1535-1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gram, L., J. Melchiorsen, and J. B. Bruhn. Antibacterial activity of marine culturable bacteria collected from a global sampling of ocean surface waters and surface swabs of marine organisms. Mar. Biotechnol, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Gram, L., J. Melchiorsen, B. Spanggaard, I. Huber, and T. F. Nielsen. 1999. Inhibition of Vibrio anguillarum by Pseudomonas fluorescens AH2, a possible probiotic treatment of fish. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:969-973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gross, A., A. Nemirovsky, D. Zilberg, A. Khaimov, A. Brenner, E. Snir, Z. Ronen, and A. Nejidat. 2003. Soil nitrifying enrichments as biofilter starters in intensive recirculating saline water aquaculture. Aquaculture 223:51-62. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grossart, H. P., A. Schlingloff, M. Bernhard, M. Simon, and T. Brinkhoff. 2004. Antagonistic activity of bacteria isolated from organic aggregates of the German Wadden Sea. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 47:387-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hjelm, M., O. Bergh, A. Riaza, J. Nielsen, J. Melchiorsen, S. Jensen, H. Duncan, P. Ahrens, H. Birkbeck, and L. Gram. 2004. Selection and identification of autochthonous potential probiotic bacteria from turbot larvae (Scophthalmus maximus) rearing units. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 27:360-371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kesarcodi-Watson, A., H. Kaspar, M. J. Lategan, and L. Gibson. 2008. Probiotics in aquaculture: the need, principles and mechanisms of action and screening processes. Aquaculture 274:1-14. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leriche, V., and B. Carpentier. 1995. Viable but nonculturable Salmonella typhimurium in single-species and binary-species biofilms in response to chlorine treatment. J. Food Prot. 58:1186-1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liang, L. 2003. Investigation of secondary metabolites of North Sea bacteria: fermentation, isolation, structure elucidation and bioactivity. Ph.D. thesis. University of Göttingen, Göttingen, Germany.

- 21.Long, R. A., and F. Azam. 2001. Antagonistic interactions among marine pelagic bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4975-4983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Makridis, P., S. Martins, T. Vercauteren, K. Van Driessche, O. Decamp, and M. T. Dinis. 2005. Evaluation of candidate probiotic strains for gilthead sea bream larvae (Sparus aurata) using an in vivo approach. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 40:274-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moons, P., C. W. Michiels, and A. Aertsen. 2009. Bacterial interactions in biofilms. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 35:157-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moriarty, D. J. W. 1998. Control of luminous Vibrio species in penaeid aquaculture ponds. Aquaculture 164:351-358. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nogami, K., K. Hamasaki, M. Maeda, and K. Hirayama. 1997. Biocontrol method in aquaculture for rearing the swimming crab larvae Portunus trituberculatus. Hydrobiologia 358:291-295. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Norqvist, A., B. Norrman, and H. Wolf-Watz. 1990. Identification and characterization of a zinc metalloprotease associated with invasion by the fish pathogen Vibrio anguillarum. Infect. Immun. 58:3731-3736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Planas, M., M. Perez-Lorenzo, M. Hjelm, L. Gram, I. U. Fiksdal, O. Bergh, and J. Pintado. 2006. Probiotic effect in vivo of Roseobacter strain 27-4 against Vibrio (Listonella) anguillarum infections in turbot (Scophthalmus maximus L.) larvae. Aquaculture 255:323-333. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Porsby, C. H., K. F. Nielsen, and L. Gram. 2008. Phaeobacter and Ruegeria species of the Roseobacter clade colonize separate niches in a Danish turbot (Scophthalmus maximus)-rearing farm and antagonize Vibrio anguillarum under different growth conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:7356-7364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prado, S., J. Montes, J. L. Romalde, and J. L. Barja. 2009. Inhibitory activity of Phaeobacter strains against aquaculture pathogenic bacteria. Int. Microbiol. 12:107-114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rao, D., J. S. Webb, C. Holmstrom, R. Case, A. Low, P. Steinberg, and S. Kjelleberg. 2007. Low densities of epiphytic bacteria from the marine alga Ulva australis inhibit settlement of fouling organisms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:7844-7852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rao, D., J. S. Webb, and S. Kjelleberg. 2006. Microbial colonization and competition on the marine alga Ulva australis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:5547-5555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rao, D., J. S. Webb, and S. Kjelleberg. 2005. Competitive interactions in mixed-species biofilms containing the marine bacterium Pseudoalteromonas tunicata. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:1729-1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ruiz-Ponte, C., V. Cilia, C. Lambert, and J. L. Nicolas. 1998. Roseobacter gallaeciensis sp. nov., a new marine bacterium isolated from rearings and collectors of the scallop Pecten maximus. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 48:537-542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schulze, A. D., A. O. Alabi, A. R. Tattersall-Sheldrake, and K. M. Miller. 2006. Bacterial diversity in a marine hatchery: balance between pathogenic and potentially probiotic bacterial strains. Aquaculture 256:50-73. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sepandj, F., H. Ceri, A. Gibb, R. Read, and M. Olson. 2004. Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) versus minimum biofilm eliminating concentration (MBEC) in evaluation of antibiotic sensitivity of gram-negative bacilli causing peritonitis. Perit. Dial. Int. 24:65-67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Slightom, R. N., and A. Buchan. 2009. Surface colonization by marine roseobacters: integrating genotype and phenotype. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:6027-6037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spanggaard, B., I. Huber, J. Nielsen, E. B. Sick, C. B. Pipper, T. Martinussen, W. J. Slierendrecht, and L. Gram. 2001. The probiotic potential against vibriosis of the indigenous microflora of rainbow trout. Environ. Microbiol. 3:755-765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Rijn, J. 1996. The potential for integrated biological treatment systems in recirculating fish culture—a review. Aquaculture 139:181-201. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Verschuere, L., G. Rombaut, P. Sorgeloos, and W. Verstraete. 2000. Probiotic bacteria as biological control agents in aquaculture. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64:655-671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vine, N. G., W. D. Leukes, and H. Kaiser. 2006. Probiotics in marine larviculture. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 30:404-427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wagner-Döbler, I., and H. Biebl. 2006. Environmental biology of the marine Roseobacter lineage. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 60:255-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]