Abstract

Purpose

Responses following BRCA1/2 genetic testing are relevant for comprehension of risk status and may play a role in risk management decision making. The objective of this study was to evaluate a Psychosocial Telephone Counseling (PTC) intervention delivered to BRCA1/2 mutation carriers following standard genetic counseling (SGC). We examined the impact of the intervention on distress and concerns related to genetic testing.

Patients and Methods

This prospective randomized clinical trial included 90 BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. We measured anxiety, depression, and genetic testing distress outcomes at intervention baseline and 6- and 12-months following disclosure. We evaluated the effects of SGC versus SGC plus PTC on psychological outcomes using intention-to-treat analyses through Generalized Estimating Equations.

Results

At 6 months, PTC reduced depressive symptoms (Z = −2.25, P = .02) and genetic testing distress (Z = 2.18, P = .02) compared to standard genetic counseling. Further, women in the intervention condition reported less clinically-significant anxiety at 6 months (χ21 = 4.11, P = .04) than women who received SGC. We found no differences in outcomes between the intervention groups at the 12-month follow-up.

Conclusions

As an adjunct to SGC, psychosocial telephone counseling delivered following disclosure of positive BRCA1/2 test results appears to offer modest benefits for distress and anxiety. These results build upon a growing literature of psychosocial interventions for BRCA1/2 carriers and, given the potential impact of affect on risk management decision making, suggest that some carriers may derive benefits from adjuncts to traditional genetic counseling.

Keywords: Psychosocial intervention, BRCA1/2 mutation carriers, telephone counseling

INTRODUCTION

Genetic counseling and testing for BRCA1 and BRCA2 (BRCA1/2) mutations have become standard care in the clinical management of women with a family history suggestive of hereditary breast or ovarian cancer (1). Although receipt of positive BRCA1/2 genetic test results does not lead to long-term clinically-relevant distress (2–5), numerous studies document both short-term and on-going distress in some mutation carriers (e.g., younger women and those with high pre-test anxiety; 6–9).

Emerging evidence shows that an individual’s emotional state can impact decision making around risk information (10). Thus, even sub-clinical or transient increases in distress following BRCA1/2 testing could potentially influence decisions about management of breast and ovarian cancer risks (11). For example, distress has been identified as a predictor of prophylactic surgery decisions among mutation carriers (12). Moreover, women who have undergone BRCA1/2 testing rate management decision making as highly stressful (11, 13, 14). Interventions are now being developed to address psychosocial concerns and provide risk management decision support during and after receipt of BRCA1/2 test results (15–18). These interventions have led to decreases in depressive symptoms (16), reduced cancer worries (15) and greater information seeking and uptake of prophylactic oophorectomy (17). Moreover, BRCA1/2 mutation carriers who were undecided about risk management reported improved psychosocial outcomes following use of a decision aid (18). These prior interventions have included individuals regardless of BRCA1/2 test result or focused exclusively on decision support.

To date, no research has evaluated an adjunct intervention designed exclusively for BRCA1/2 carriers to address psychosocial concerns. In the present study, we developed a post-disclosure psychosocial telephone counseling (PTC) intervention to address psychological reactions to receiving positive BRCA1/2 test results. The intervention was based on the Transactional Model of Stress and Coping (19), which posits that an individual’s adjustment to a stressor is driven, in part, by their appraisal of the stressor as threatening and their ability to manage the stressor. We hypothesized that the PTC intervention would lead to improved psychological functioning compared to standard genetic counseling (SGC), with improved functioning moderated by perceptions of stress and confidence related to managing genetic testing stressors. Evaluating the impact of disseminable interventions for BRCA1/2 carriers will provide additional information on the value of these programs for psychosocial outcomes and risk management decisions in this population.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Population

Participants were female BRCA1/2 mutation carriers ages 18 and older identified through genetic counseling and testing programs in Washington, DC and Toronto, Canada. Women with metastatic disease or recurrent ovarian cancer and those who did not read and speak English were ineligible for this study. Genetic counseling and testing and psychosocial telephone counseling were provided free of charge. The institutional review boards at both centers approved the research protocol. All women provided written informed consent for study participation at the pre-test genetic counseling session.

Design and Procedures

The procedures for this study have been described in detail in previous reports (20, 21) and are summarized here. We contacted potential participants by telephone to determine eligibility and complete a pre-test questionnaire assessing sociodemographics, personal and family history of cancer, and psychological functioning. Participants attended standardized pre-test education and post-test results disclosure sessions conducted by a genetic counselor.

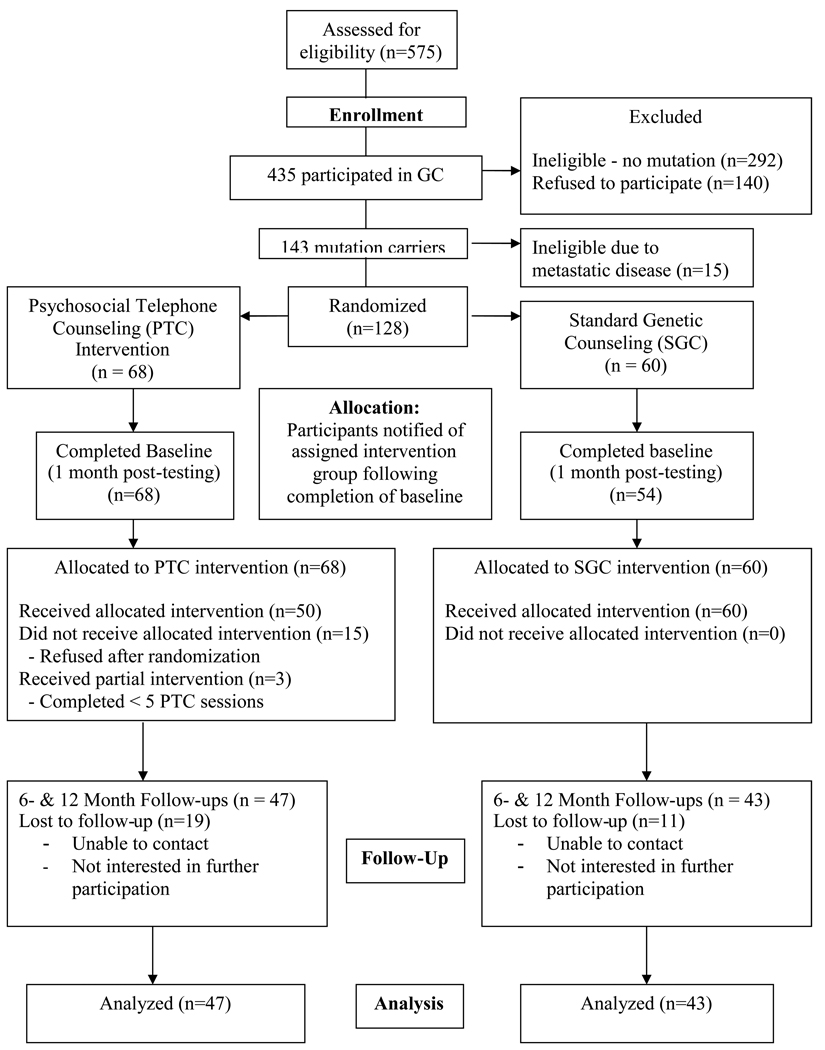

One month after disclosure of BRCA1/2 test results, but prior to notification of intervention group assignment, we contacted participants for a follow-up telephone interview to assess psychological functioning. This interview served as the baseline (pre-intervention) assessment. Interviewers informed participants of their study assignment at the end of this assessment. BRCA1/2 mutation carriers were randomized to receive SGC only or SGC plus PTC (see Figure 1). A computer-generated randomization program stratified intervention assignments by study site. We assigned mutation carriers from the same family to the same intervention group and PTC counselor. Participants completed follow up interviews 6- and 12-months after receipt of their test results.

Figure 1.

Study Flow Chart.

Counseling Protocols

Standard Genetic Counseling (SGC)

The pre-test education session included a discussion about hereditary breast and ovarian cancer, mutation testing, and the potential benefits, limitations, and risks of genetic testing. The disclosure session included disclosure of test results, information about the risks of developing cancer, and individualized management strategies. Participants received a written summary letter and a standard follow-up call from their genetic counselor 2 weeks after disclosure.

Standard Genetic Counseling plus Psychosocial Telephone Counseling (PTC)

The PTC protocol included all aspects of SGC. Following the completion of SGC, individuals randomized to PTC also received a psychosocial telephone counseling intervention. The PTC intervention consisted of 5 weekly telephone counseling sessions delivered by trained and supervised Master’s level mental health counselors (22). Intervention materials were mailed to PTC participants prior to the first session and included four booklets: “Emotional Responses to Genetic Testing,” “Making Medical Decisions,” “Managing Family Concerns,” and “The CARE Workbook: Strategies to Help Cope with Stressors Related to your Genetic Test Result.”

To facilitate the transfer from SGC to the PTC intervention, genetic counselors provided PTC counselors with case notes and reports, and spoke with the PTC counselor regarding the participant’s primary concerns about medical decision-making, family issues, and emotional reactions. PTC counselors then contacted participants to orient them to the intervention and schedule the five sessions.

The first session of PTC consisted of a semi-structured clinical interview to elicit participants’ reactions to their test results. Sessions 2–4 were individualized to the specific concerns raised by each participant during their disclosure session and PTC Session 1. Although participants from the same family were assigned to the same PTC counselor, counselors did not share information that had been provided by other relatives. Specific coping strategies (e.g., problem solving, role playing) tailored to each participant’s needs were developed and applied during sessions 2–4. The final session focused on integration/closure and development of a plan to execute goals.

Measures

Covariates

We obtained demographic and clinical information during the pre-test telephone interview. We assessed age, marital status, income, education, employment, and personal/family history of cancer.

Moderators

Appraisals: Perceptions of Stress and Confidence

We used the perceived stress and confidence scales (23) to evaluate whether primary (stress) and secondary (confidence) appraisals moderate the impact of the PTC intervention on distress. Both scales consisted of 5 items, with responses made on a 4-point Likert-style scale. Both scales also had adequate internal consistency in the present study (perceived stress α = .73; perceived confidence α = .79).

Outcome Variables

Primary Distress Outcomes: Anxiety and Depression

We measured anxiety and depression using the Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL-25) (24). The HSCL-25 is a 25-item Likert-style instrument that evaluates the presence and severity of anxiety and depressive symptoms during the past month. The anxiety (10 items) and depression (13 items) subscales are each answered on 4-point scales (1 = “Not at All” to 4 = “Extremely”). We did not use the two somatic items from the scale. Internal consistency in the present study was α = .82 and α = .87 for the anxiety and depression subscales, respectively. We calculated an overall distress score by combining the subscale scores. Clinically significant levels of anxiety, depression, and overall distress were calculated by dividing the sum of each subscale by the number of items, with scores above 1.75 defined as clinically-significant (25).

Secondary Distress Outcomes: Genetic Testing Concerns

We used the Multi-Dimensional Assessment of Cancer Risk Assessment (MICRA) scale to evaluate emotional responses to BRCA1/2 test results (6). The MICRA is a 21-item Likert-style scale that assesses affective responses to receiving BRCA1/2 test results. The MICRA has demonstrated solid validity and reliability in prior research (6), and had good internal consistency in the present study (α = .84).

Data Analysis

We compared the two study arms on sociodemographics and baseline distress using χ2 tests for categorical variables and Wilcoxon tests for continuous measures because of nonnormal distribution of the appraisal and distress variables at baseline. Log and square root transformations were not successful in creating normal distributions for these variables. We also used Wilcoxon tests to identify demographic factors associated with baseline levels of outcome measures and χ2 and t-tests to identify demographic factors associated with study retention and completion of the PTC intervention. We used t-tests to evaluate differences in outcomes between study arms at each time point, as t-tests appear to be robust against most violations of normality (26). To identify the impact of the intervention on clinically-significant anxiety, depression, and overall distress, we used a χ2 test comparing “cases” to “noncases” across study arms. Finally, to evaluate the independent effect of study arm on distress at 6 and 12 months, we conducted multiple linear regression analyses using Generalized Estimating Equations to control for intra-familial correlations. As appropriate, we included baseline levels of each outcome and control variables in the regression models. We evaluated whether the stress or confidence appraisal variables moderated the impact of the intervention on psychosocial outcomes by entering an interaction term into the regression models. We adjusted for multiple comparisons (27) and used an intention-to-treat approach in which we included all participants regardless of whether they completed the intervention. To help inform the design of future cluster randomized trials we estimated the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for the 6-months psychological outcomes (28).

RESULTS

A total of 575 eligible women were identified and of these, 435 (76%) participated in genetic counseling and received BRCA1/2 test results (Figure 1). Of the 435 women who received BRCA1/2 test results, 128 were identified as mutation carriers eligible for study participation. Eligible women were randomized to PTC (n = 68 women, 46 families) or SGC (n = 60 women, 46 families; see Figure 1). The two arms did not differ on sociodemographic characteristics or baseline psychological functioning.

Fifty (76%) PTC participants completed all five telephone sessions, 3 (4%) completed 1–4 sessions and 13 (22%) declined to participate in the intervention. On average, participants initiated the first counseling session 37.9 days (SD=23.4 days) after the intervention baseline assessment and completed all 5 telephone sessions within 35 days (SD=21 days). Prior work has described differences between intervention completers and non-completers (20). Seventy-two percent (n = 43) and 65% (n = 39) of SGC participants completed the 6- and 12-month follow up assessments compared to 69% (n = 47) and 65% (n = 44) of PTC participants. Women lost to follow-up had more years of education than women who remained in the study (χ2 = 3.97, P = .046). There were no other differences between these groups. We controlled for education in all outcome analyses. Final analyses included data from 90 participants for the 6- and 12-month follow-ups. As shown in Table 1, there were no differences in sociodemographic or clinical characteristics between study groups.

Table 1.

Characteristics of sample by intervention condition

| Characteristic | PTC (n = 47) N (%) |

SGC (n = 43) N (%) |

All (n = 90) N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| ≤ 50 years | 36 (76.6) | 32 (74.4) | 68 (75.6) |

| > 50 years | 11 (23.4) | 11 (25.6) | 22 (24.4) |

| Breast/Ovarian Cancer Affected Status | |||

| Affected | 23 (48.9) | 25 (58.1) | 48 (53.3) |

| Unaffected | 24 (51.1) | 18 (41.9) | 42 (46.7) |

| Proband Status | |||

| Proband | 20 (42.6) | 18 (41.9) | 38 (42.2) |

| Relative | 27 (57.4) | 25 (58.1) | 52 (57.8) |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 36 (76.6) | 35 (81.4) | 71 (78.9) |

| Unmarried | 11 (23.4) | 8 (18.6) | 19 (21.1) |

| Education | |||

| Some college/degree | 35 (74.5) | 30 (69.8) | 65 (72.2) |

| No college | 12 (25.5) | 13 (30.2) | 25 (27.8) |

| Employed | |||

| Full time (%) | 36 (76.6) | 33 (76.7) | 69 (76.7) |

| < Full time (%) | 11 (23.4) | 10 (23.3) | 21 (23.3) |

| Annual income§ | |||

| < 75,000 (%) | 20 (45.5) | 25 (59.5) | 45 (52.3) |

| ≥ 75,000 (%) | 24 (55.5) | 17 (40.9) | 41 (47.7) |

NOTE: SGC = Standard Genetic Counseling. Affected=Participants with a personal history of breast and/or ovarian cancer. Unaffected=Participants without a personal history of breast and/or ovarian cancer. Proband = First person in the family to be tested for BRCA1/2. Relative = A person who has BRCA1/2 testing who is a relative of someone positive for the BRCA1/2 mutation.

Totals do not add to 90 in all cells due to a small amount of missing data on this variable.

Bivariate Comparison of Intervention Outcomes

Bivariate analyses revealed that PTC participants reported significantly lower depression scores at 6-months compared to SGC participants [t(df=88) = 2.12, P = .02). PTC participants were also less likely than SGC participants to report clinically-significant levels of anxiety at 6-months (6.4% vs. 20.9%, respectively; χ21 = 4.11, P = .04). Trends were evident for PTC participants to report lower levels of clinically-significant depression (χ21 = 3.43, P = .06) and overall distress (χ21 = 3.72, P = .05) at 6-months. There were no differences between the SGC and PTC groups at 12-months on any study outcomes.

Multivariate Analysis of Psychological Outcomes

After adjusting for baseline psychological outcomes and other controlling variables (employment, education, income, and affected status), intervention group had a significant independent effect on depressive symptoms (Z = 2.25, P = .02) and genetic testing distress (Z = 2.18, P = .02; see Table 2) at 6-months. Women randomized to the PTC group reported reduced depression and genetic-testing distress at 6-months relative to the SGC group. We conducted identical General Estimating Equation multiple regression analyses for psychosocial outcomes at the 12-month follow-up and evaluated whether stress or confidence appraisals at 6-months moderated the impact of the PTC intervention on 12-month outcomes. Intervention group was not a significant predictor for any of the outcomes at 12-months, nor did the primary stress or secondary confidence appraisals moderate the impact of the intervention on study outcomes.

Table 2.

General Estimating Equation Multiple Regression Analysis of 6-Month Psychological Outcomes among BRCA1/2 Mutation Carriers (n=90)‡

| Dependent Variable |

Predictor‡‡ Variables |

Parameter Estimate |

Z-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline depression | 0.66 | 4.58*** | |

| Depressive symptoms | Employment status | −2.37 | −1.30 |

| Education level | 2.00 | 1.52 | |

| Income level | 0.16 | 0.13 | |

| Cancer history | 0.80 | 0.77 | |

| Intervention group | −2.28 | −2.25* | |

| Baseline anxiety | 0.57 | 5.61*** | |

| Anxiety symptoms | Employment status | −3.48 | −2.20 |

| Education level | 0.04 | 0.03 | |

| Income level | 4.05 | 3.38*** | |

| Cancer history | 0.12 | 0.12 | |

| Intervention group | −1.37 | −1.44 | |

| Baseline genetic testing concerns | 0.71 | 14.12*** | |

| Genetic Testing | Employment status | −7.22 | −3.12** |

| Concerns | Education level | −1.17 | −0.56 |

| Income Level | −0.82 | −0.39 | |

| Cancer history | 0.88 | 0.48 | |

| Intervention group | −3.53 | −2.18* | |

NOTE: Employment status: Employed versus Not Employed; Education level: ≥ College vs. < College; Income Level < $75,000 vs. ≥ $75,000, Cancer history: Affected versus Unaffected; Intervention: PTC versus Standard Genetic Counseling.

Because of a small amount of missing data for outcome variables and the income variable (< 5%), not all models have the same sample size indicated above.

p<.001;

p < .01.

p<.05.

The cluster randomized trial included 90 women (observations) and 72 families (clusters), with an average of 1.25 observations per cluster. The estimated ICCs for the 6-months psychological outcomes were 0 for depressive symptoms, 0.07 for genetic testing concern, and 0.21 for anxiety symptoms. Following common practice we set to 0 the estimated ICC for the 6-months depressive symptoms, since we obtained a small negative estimate, and a negative ICC (i.e. women from the same family are less similar to one another with respect to depressive symptoms than they are to women from another family) did not seem theoretically plausible.

Discussion

A small but growing literature suggests that BRCA1/2 carriers may benefit from post-disclosure interventions over the short- to intermediate-term (17, 29). The current randomized controlled trial evaluated the effects of post-disclosure psychosocial telephone counseling on psychological functioning in female BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. Six months after result notification, BRCA1/2 mutation carriers randomized to PTC reported significant decreases in depressive symptoms, were less likely to meet criteria for clinically significant anxiety, and reported significant decreases in genetic testing distress relative to those randomized to SGC. To our knowledge, this is the first study to report that post-disclosure telephone counseling reduces psychological distress among BRCA1/2 mutation carriers.

Although the beneficial effects of the PTC intervention were seen at 6- but not at 12-months, there is reason to speculate that reducing distress in the immediate aftermath of receiving a positive test result could have important benefits. Considerable evidence documents the impact of affect on decision-making and risk comprehension (10, 30, 31). Given the complexity of decision-making following BRCA1/2 testing (32), an intervention that reduces distress during this crucial decision making period could improve informed decision making, risk comprehension and family communication. Although PTC did not impact participants’ stress or confidence appraisals, future research should further explore the overall role of affect on BRCA1/2 risk management decision making (9–11).

In addition to the potential benefits on risk-management decision making, our results and prior research suggest that adjunct interventions may provide benefits to subgroups of women who undergo BRCA1/2 genetic counseling and testing (9). Specifically, support programs like PTC may be most useful for women identified by genetic counselors as highly anxious or undecided about management options (8). Future studies can explore the best methods for identifying such at-risk subgroups, investigate the theoretical mechanisms by which support programs produce change, and evaluate the most effective timing and delivery approaches for supportive adjunct interventions.

The beneficial effect of psychosocial telephone counseling on depressive symptoms, clinical levels of anxiety, and genetic testing distress should be interpreted in a larger context. First, it is noteworthy that a telephone counseling intervention can have a positive effect on psychological functioning within this specific population. This novel method of care delivery increases the portability of counseling services by overcoming transportation and geographic barriers (33). Second, it is possible that reduced anxiety and distress may improve comprehension of genetic risk information and may facilitate decision-making about screening, managing risk, and communicating risk information (31, 34). Third, it is important to note that although clinically-relevant levels of anxiety were reduced, the level of depressive symptoms reported by participants would not require psychiatric intervention (24), findings consistent with prior research in this area (2). Although psychiatric intervention is not indicated for the majority of BRCA1/2 mutation carriers, interventions that provide short-term support may be beneficial for subgroups of carriers or women who self-select into these types of support interventions.

There are several limitations to this study. First, the small sample of 90 BRCA1/2 mutation carriers was homogenous; participants were Caucasian and reported high levels of education and income. Results need to be evaluated using larger and more diverse samples to improve power to detect intervention effects and extend generalizability of the results. Second, not all PTC participants completed the intervention and we did not assess the extent to which the women read or used the intervention materials. These concerns are mitigated by our use of intention-to-treat analyses, the fact that the majority (76%) of women randomized to PTC did complete the intervention, and similar rates of study retention between the PTC and SGC groups. Third, the impact of the intervention observed at 6 months was not sustained at 12-months. Future work can explore the best methods to maintain long-term effects. Despite these limitations, the present study is the first randomized clinical trial to demonstrate the beneficial effects of post-disclosure telephone counseling on psychological functioning among mutation carriers. Given the availability of direct-to-consumer genetic testing for a variety of health conditions including online testing for the three BRCA1/2 founder mutations (35), the value of adjunctive support services like psychosocial telephone counseling is likely to increase. Our findings add to the growing literature on adjunct interventions following genetic counseling by demonstrating that a post-disclosure telephone psychosocial intervention is feasible and provides short-to-intermediate term benefits for BRCA1/2 carriers.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by the National Human Genome Research Institute grant #HG01846. Preparation of this manuscript was supported by Department of Defense grant #DAMD17-00-1-0262 (to CHH) and the National Cancer Institute grant #K07CA131172 (to KDG). We would like to acknowledge Caryn Lerman, Ph.D., and Kathleen Garrett, M.A, for assistance with developing the PTC materials; Tiffani DeMarco, M.S., Barbara Brogan, M.S. RN, Elizabeth Hoodfar, M.S., CGC and Danielle Hanna, M.S., CGC for providing genetic counseling to study participants; Camille Corio, M.S. for data management; V. Holland LaSalle, B.S. for conducting telephone interviews; and Susan Marx and Wilma Higginbotham for assistance with manuscript preparation. Most importantly, we would like to thank study participants for their contribution to this research.

Footnotes

An early version of this paper was presented at the Society of Behavioral Medicine Annual Scientific Conference in Baltimore, Maryland in 2004.

References

- 1.Nusbaum R, Isaacs C. Management updates for women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. Mol Diagn Ther. 2007;11:133–144. doi: 10.1007/BF03256234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coyne JC, Benazon NR, Gaba CG, Calzone K, Weber BL. Distress and psychiatric morbidity among women from high-risk breast and ovarian cancer families. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:864–874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamilton JG, Lobel M, Moyer A. Emotional distress following genetic testing for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer: a meta-analytic review. Health Psychol. 2009;28:510–518. doi: 10.1037/a0014778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palmer SC, Kagee A, Kruus L, Coyne JC. Overemphasis of psychological risks of genetic testing may have "dire" consequences. Psychosomatics. 2002;43:86–87. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.43.1.86-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwartz MD, Peshkin BN, Hughes C, et al. Impact of BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation testing on psychologic distress in a clinic-based sample. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:514–520. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.2.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cella D, Hughes C, Peterman A, et al. A brief assessment of concerns associated with genetic testing for cancer: the Multidimensional Impact of Cancer Risk Assessment (MICRA) questionnaire. Health Psychol. 2002;21:564–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dorval M, Patenaude AF, Schneider KA, et al. Anticipated versus actual emotional reactions to disclosure of results of genetic tests for cancer susceptibility: findings from p53 and BRCA1 testing programs. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2135–2142. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.10.2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tercyak KP, Lerman C, Peshkin BN, et al. Effects of coping style and BRCA1 and BRCA2 test results on anxiety among women participating in genetic counseling and testing for breast and ovarian cancer risk. Health Psychol. 2001;20:217–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vadaparampil ST, Miree CA, Wilson C, Jacobsen PB. Psychosocial and behavioral impact of genetic counseling and testing. Breast Dis. 2006;27:97–108. doi: 10.3233/bd-2007-27106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Slovic P, Peters E, Finucane ML, Macgregor DG. Affect, risk, and decision making. Health Psychol. 2005;24:S35–S40. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.4.S35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwartz MD, Peshkin BN, Tercyak KP, Taylor KL, Valdimarsdottir H. Decision making and decision support for hereditary breast-ovarian cancer susceptibility. Health Psychol. 2005;24:S78–S84. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.4.S78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graves KD, Peshkin BN, Halbert CH, et al. Predictors and outcomes of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy among breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;104:321–329. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9423-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kenen RH, Shapiro PJ, Friedman S, Coyne JC. Peer-support in coping with medical uncertainty: discussion of oophorectomy and hormone replacement therapy on a web-based message board. Psychooncology. 2007;16:763–771. doi: 10.1002/pon.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Neill SC, DeMarco T, Peshkin BN, et al. Tolerance for uncertainty and perceived risk among women receiving uninformative BRCA1/2 test results. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2006;142C:251–259. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charles S, Kessler L, Stopfer JE, Domchek S, Halbert CH. Satisfaction with genetic counseling for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations among African American women. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;63:196–204. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McInerney-Leo A, Biesecker BB, Hadley DW, et al. BRCA1/2 testing in hereditary breast and ovarian cancer families: effectiveness of problem-solving training as a counseling intervention. Am J Med Genet A. 2004;130A:221–227. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller SM, Roussi P, Daly MB, et al. Enhanced counseling for women undergoing BRCA1/2 testing: impact on subsequent decision making about risk reduction behaviors. Health Educ Behav. 2005;32:654–667. doi: 10.1177/1090198105278758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwartz MD, Valdimarsdottir HB, Demarco TA, et al. Randomized trial of a decision aid for BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation carriers: Impact on measures of decision making and satisfaction. Health Psychol. 2009;28:11–19. doi: 10.1037/a0013147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halbert CH, Wenzel L, Lerman C, et al. Predictors of participation in psychosocial telephone counseling following genetic testing for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:875–881. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hughes C, Lerman C, Schwartz M, et al. All in the family: evaluation of the process and content of sisters' communication about BRCA1 and BRCA2 genetic test results. Am J Med Genet. 2002;107:143–150. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marcus AC, Garrett KM, Kulchak-Rahm A, et al. Telephone counseling in psychosocial oncology: a report from the Cancer Information and Counseling Line. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;46:267–275. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(01)00163-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Halbert CH, Schwartz MD, Wenzel L, et al. Predictors of cognitive appraisals following genetic testing for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. J Behav Med. 2004;27:373–392. doi: 10.1023/b:jobm.0000042411.56032.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH, Covi L. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): a self-report symptom inventory. Behav Sci. 1974;19:1–15. doi: 10.1002/bs.3830190102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sandanger I, Moum T, Ingebrigtsen G, et al. The meaning and significance of caseness: the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 and the Composite International Diagnostic Interview. II. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1999;34:53–59. doi: 10.1007/s001270050112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Edgell SE, Noon SM. Effect of violation of normality on the t test of the correlation coefficient. Psychol Bull. 1984;95:576–583. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sankoh AJ, Huque MF, Dubey SD. Some comments on frequently used multiple endpoint adjustment methods in clinical trials. Stat Med. 1997;16:2529–2542. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19971130)16:22<2529::aid-sim692>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Donner A, Klar N. Design and analysis of cluster randomization trials in health research. London: Arnold; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Daly MB, Barsevick A, Miller SM, et al. Communicating genetic test results to the family: a six-step, skills-building strategy. Fam Community Health. 2001;24:13–26. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200110000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kash KM, Holland JC, Halper MS, Miller DG. Psychological distress and surveillance behaviors of women with a family history of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1992;84:24–30. doi: 10.1093/jnci/84.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lerman C, Lustbader E, Rimer B, et al. Effects of individualized breast cancer risk counseling: a randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:286–292. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.4.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peshkin BN. Breast cancer risk assessment and genetic testing: complexities, conundrums, and community. Breast Dis. 2006;27:1–3. doi: 10.3233/bd-2007-27101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peshkin BN, Demarco TA, Graves KD, et al. Telephone genetic counseling for high-risk women undergoing BRCA1 and BRCA2 testing: rationale and development of a randomized controlled trial. Genet Test. 2008;12:37–52. doi: 10.1089/gte.2006.0525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Esplen MJ, Toner B, Hunter J, et al. A supportive-expressive group intervention for women with a family history of breast cancer: results of a phase II study. Psychooncology. 2000;9:243–252. doi: 10.1002/1099-1611(200005/06)9:3<243::aid-pon457>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. [Retrieved September 25 2009];23andMe. 2009 from URL: https://www.23andme.com [Online].