Abstract

The molecular mechanisms by which chronic hypoxia, whether constant (CCH) or intermittent (CIH), alters the heart rhythm are still under debate. Expression level, control, maturational profile and intercoordination of 54 genes encoding heart rhythm determinants (HRDs) were analyzed in 36 mice subjected for one, two or four weeks of their early life to normal atmospheric conditions or to CCH or CIH. Our analysis revealed a complex network of genes encoding various heart rate, inotropy and development controllers, receptors, ion channels and transporters, ankyrins, epigenetic modulators and intercalated disc components (adherens, cadherins, catenins, desmosomal, gap and tight junction proteins). The network is remodeled during maturation and substantially and differently altered by CIH and CCH. Gene Prominence Analysis that ranks the genes according to their expression stability and networking within functional gene webs, confirmed the HRD status of certain epigenetic modulators and components of the intercalated discs not yet associated with arrhythmia.

Keywords: arrhythmia, connexin43, coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor, intercalated disc, myocyte enhancer factors, plakophilins

Introduction

Chronic hypoxia, whether constant (CCH, as in pulmonary diseases or living at high altitude) or intermittent (CIH, as in obstructive sleep apnea) is typically implicated in hypertension, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, pulmonary hypertension, stroke and cardiac arrhythmias [1- 4]. Experimental data suggest that part of these cardiac disorders are caused by sympathetic overactivity, selective activation of inflammatory molecular pathways, endothelial dysfunction, abnormality in the process of coagulation and metabolic dysregulation [5, 6] induced by oxygen deprivation. However, the molecular mechanisms by which chronic hypoxia induces cardiovascular diseases are still poorly understood. Numerous microarray studies have compared the heart transcriptomes of arrhythmic and non-arrhythmic humans and animal models (e.g.: [7- 13] identifying significantly regulated genes and clustering them according to Gene Ontology (GO) terms and fold expression changes. These studies, reviewed periodically (e.g. [14-16]) have had a high impact in delineating essential genomic alterations induced by or predisposing to the disease and in describing transcriptomic differences between atria and ventricles. Through gene expression microarray we and others have also identified hundreds of genes and several gene clusters as being regulated by chronic hypoxia imposed to mice or rats in their early life, with major differences between the two hypoxia paradigms (e.g.: [17-21]).

New analyses, such as those of expression variability and control of transcript abundance [22], gene networking [23, 24], regulation and perturbation of functional gene cohorts [25] and “see-saw” partnership [25, 26], have been developed to better describe alterations in the genomic fabric. Recently, we have introduced the Prominent Gene Analysis [27] that refines iteratively the functional gene webs by considering both coordination and control of gene expression within the web.

Here, we report how expression level, stability, intercoordination and prominence (new indicator) of 54 potential HRD genes (full names in figure legends) change with age and are affected by chronic hypoxia. Gene selection includes adrenergic (Adrbk1) and Ca2+- release (Itpr1, Itpr2, Ryr1) receptors, ankyrins (Ank2, Ank3), ion channels and transporters (Atp1a1, Atp1a2, Atp2a2, Kcnh2, Slc25a20, Slc8a1), regulators of heart rhythm (Lamp2, Lmna, Sema3a, Ttr), contraction (Dmpk, Gnao1), inotropy (Csrp3, Gaa) and development (Id2, Nfatc3, Tbx5), as well as direct and indirect epigenetic modulators (Hand2, Hdac5, Mef2a, Mef2b, Mef2c, Mef2d, Smyd1) in relation with miR-1. Moreover, since generation of synchronized rhythmic heart contractions requires integration of electrical and mechanical properties, we have also incorporated in this study genes encoding components of the intercalated discs (specialized regions of the plasma membrane that link neighboring cardiac myocytes). Thus, we have profiled several adherens (Jup, Vcl, Vezt), members of the cadherin (Calcium dependent adhesion molecules) superfamily (Cdh13, Cdh16, Cdh2, Cdh22, Cdh5, Dsc2, Dsg2, Pcdh12, Pcdh7, Pcdhgc3) and cadherin associated proteins (Ctnna1, Ctnnal1, Ctnb1, Ctnd1), plakophilins (Pkp2, Pkp3, Pkp4), and tight (Cxadr, Tjp1, Tjp2,) and gap junction proteins (Gja1).

A particular interest was to determine the transcriptomic network by which Gja1, the gene that encodes connexin43 (Cx43), controls the HRD gene web, attempting to elucidate the association of altered Cx43 to defects in heart rhythm and development (e.g.: [23, 28]. Cx43 is the primary component of the intercellular gap junction channels in ventricles that provide low resistance pathways for impulse propagation and cytoplasmic continuity between coupled cells for Ca2+ and second messengers [29].

Materials and Methods

Microarray data

The data used in the analyses below were obtained in a previously published cDNA microarray experiment validated through qRT-PCR [17] and deposited as series GSE2271 in http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo. In this experiment we profiled the expression of 4862 well-annotated unigenes in nine sets of CD1 mouse siblings, each composed of two males and two females, subjected for one, two or four weeks of their early life to normal atmospheric conditions (NOR) or to CCH or CIH. While in CCH [O2] was kept constant at 11%, in CIH [O2] was switched between 21% and 11% every four minutes for the entire duration of the treatment.

Detection of significantly regulated genes relied on both absolute >1.5× fold change and >0.05 p-val of the heteroscedastic t-test for the equality of two means with Bonferroni correction applied to the group of spots probing redundantly the same gene [24]. By denoting by D/U/X = down-/up-/not regulation when comparing the expression levels at two successive time-points, we obtained one “passive” (XX) and 8 “active” maturational profiles (DD, DU, DX, UD, UU, UX, XD, XU) [18, 19].

Analysis of transcript abundance control

As illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 1A for 1 week NOR, the expression level of a gene is not identical among biological replicas owing to differences in local conditions. Moreover, this expression variability is not uniform across the genes. Therefore, the genes were ordered as decreasing REV (Relative Expression Variability) score, defined as the midrange of the X2 estimate of the coefficient of variability (= 100stdev/average) within the redundancy groups of biological replicas) within each set of mice. Thus, the first percentile (or Gene Expression Stability score GES < 1) contained the most unstably expressed, and the 100th percentile the most stably expressed genes [22]. High stability indicates a strict control of transcript abundance, presumably because that gene is critical for cell survival or/and phenotypic expression, or/and integration in the multicellular structure [24].

Analysis of expression coordination

Two genes were considered as synergistically expressed (Adrbk1 & Ank3 in Supplementary Fig. 1B) if their expression levels increased and decreased together (positive covariance) within biological replicas, or as antagonistically expressed (negative covariance) when they manifest opposite tendencies (Adrbk1 & Ank2), and as independently expressed when their expressions are not correlated (close to zero covariance, Adrbk1 & Pkp2). In the case of four replicas, the (p < 0.05) cut-off for synergism is pair-wise Pearson correlation coefficient ρ > 0.90, for antagonism ρ < - 0.90 and for independence | ρ | < 0.05. Altogether the HRD genes and their interlinkages define the HRD gene web.

Analysis of gene prominence

We define the gene gi prominence within the web W as the percentile locating its prominence score GPS with the type I error α:

| (1) |

where: {W} is the number of genes in the web W, Ri is the number of spots probing redundantly gene gi, and VAR and COVAR are the variance and the covariance of the expressed levels (x) of the indicated genes within the four biological replicas.

Results

Chronic hypoxia alters the expression level of HRD genes

Figure 1 presents the significantly regulated HRD genes by CIH and CCH with respect to the corresponding normoxic controls. Regulation of key HRD genes proves that chronic hypoxia is an arrhythmogenic factor. However, none of the quantified HRD genes was similarly regulated by CIH and CCH.

Figure 1. Fold change of significantly regulated HRD genes after 1 (A), 2 (B) and 4 (C) weeks exposure to CIH or CCH with respect to normoxic levels.

Negative values indicate down-regulation and zero value non-significant regulation. Note that no gene was similarly regulated by CIH and CCH. Genes: Adrbk1 = Adrenergic receptor kinase, beta 1, Ank2/3 = Ankyrin 2/3, Cdh13/16/2 = Cadherin 13/16/2, Csrp3 = Cysteine and glycine-rich protein 3, Ctnnal1 = Catenin (cadherin associated protein), alpha-like 1, Cxadr = Coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor, Dmpk = Dystrophia myotonica-protein kinase, Hdac5 = Histone deacetylase 5, Id2 = Inhibitor of DNA binding 2, Itpr1 = Inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor 1, Jup = Junction plakoglobin, Kcnh2 = Potassium voltage-gated channel, subfamily H (eag-related), member 2, Nfatc3 = Nuclear factor of activated T-cells, cytoplasmic, calcineurin-dependent 3, Pcdhgc3 = Protocadherin gamma subfamily C, 3, Sema3a = Sema domain, immunoglobulin domain (Ig), short basic domain, secreted, (semaphorin) 3A, Slc25a20 = Solute carrier family 25 (mitochondrial carnitine/acylcarnitine translocase), member 20, Slc8a1 = Solute carrier family 8 (sodium/calcium exchanger), member 1, Tjp1/2 = Tight junction protein 1/2, Vcl = Vinculin, Vezt = Vezatin, adherens junctions transmembrane protein.

Chronic hypoxia accelerates maturation of the heart rhythm transcriptome

As illustrated in Figure 2, the expression level of several HRD genes was changed significantly during maturation. In NOR 10 (19%) of the selected genes presented active maturational profile, although none of them changed significantly in both intervals. The number of age-dependent genes increased to 20 (37%) in CIH and to 24 (44%) in CCH, without anyone presenting sustained up- (UU) or down- (DD) regulation. Together with similar findings for translation regulators and stress response proteins [18], this substantial increase in the number of genes with active maturational profile indicates faster heart ageing in hypoxia.

Figure 2. HRD genes with significant fold change (negative for down-regulation) of the expression level during maturation in NOR (A), CIH (B) and CCH (C).

Note that much larger numbers of genes changed the expression level during the development in hypoxia and the lack of overlap between the effects of CIH and CCH. Genes: Atp1a1 = ATPase, Na+/K+ transporting, alpha 1 polypeptide, Atp2a2 = ATPase, Ca++ transporting, cardiac muscle, slow twitch 2, Ctnna1 = Catenin (cadherin associated protein), alpha 1, Dsg2 = Desmoglein 2, Gaa = Glucosidase, alpha, acid, Hand2 = Heart and neural crest derivatives expressed transcript 2, Mef2a/b/c = Myocyte enhancer factor 2A/B/C, Pcdh12/7 = Protocadherin 12/7, Pkp4 = Plakophilin 4, Smyd1 = SET and MYND domain containing 1, Tbx5 = T-box 5.

Variability and control of HRD genes

Supplementary Figure 2 plots the REV scores in all conditions. One may observe that the expression variability of HRD genes changes with age and is strongly affected by oxygen deprivation. For instance, Slc25a20, the most unstably expressed HRD gene at 4 weeks NOR (GES = 2), was among the most stably expressed genes at 1 week CIH (GES = 99). The most controlled gene in all conditions was Pcdh7 (Protocadherin 7) at 2w NOR (GES = 99.94), while the least controlled one was Ctnna1 (Catenin (cadherin associated protein), alpha 1) at 2w CIH (GES = 0.14).

HRD gene web

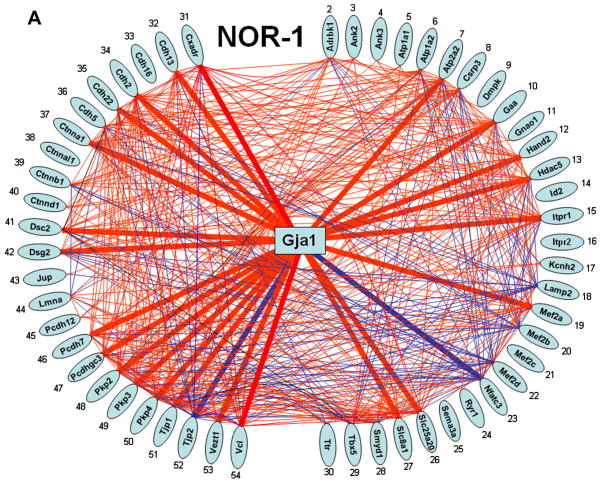

Figure 3 presents the network of the selected 54 HRD genes at 1 week NOR and Supplementary Figure 3 the networks of the same genes in all 9 conditions. Of note is the complexity of the network, how it changes during maturation, and how CIH and CCH differently affect it. The percentages of the coordinately expressed gene pairs were: NOR (42% at 1w, 41% at 2w and 18% at 4w), CIH (20, 30, 16) and CCH (24, 35, 18). The > 40% expression coordination at 1 and 2 weeks NOR may explain why arrhythmia is so rare in early life. Remarkably, although the expression level of most genes was not regulated by the oxygen deprivation, their web was profoundly remodeled. For instance, none of the 3 plakophilins were regulated by 1week CIH or CCH but the high interlinkage in nomoxia (32, 33, 34 coordinately expressed partners for Pkp2, Pkp3 and Pkp4) is reduced at 9, 1, 1 by CIH, and at 3, 8, 4 by CCH. It is likely that this remodeling plays an important role in the perturbation of the heart rhythm. However, the synergistic expression of Cxadr and Gja1 is conserved in 7 (NOR-1, CIH-1, CCH-1, NOR-2, CIH-2, CIH-4 and CCH-4) out of 9 conditions.

Figure 3. Expression coordination of HRD genes at 1 week exposure to normal atmospheric conditions.

Genes of the intercalated disc complex are grouped on the left side of each network. Red/blue color of the connecting lines indicates that the linked genes were significantly synergistically/antagonistically expressed (interlinkages with Gja1 represented by thicker lines). Genes: Cdh2/5/13/22 = Cadherin 2/5/13/22, Ctnnb1/d1 = Catenin (cadherin associated protein), beta 1/delta1, Dsc2 = Desmocollin 2, Itpr2 = Inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor 2, Mef2d = Myocyte enhancer factor 2D, Ryr1 = Ryanodine receptor 1, skeletal muscle.

Prominence of HRD genes

In Figure 4, we plot the gene prominences (GP, see Methods) in each treatment after 1 week and in Supplementary Figure 4 the prominences in all 9 conditions. Like other characteristics, the relevance of the selected HRD genes changes during maturation and is substantially and differently altered by the two hypoxia paradigms. On average for the three durations, the most prominent genes (smaller GPs) in NOR were: Lmna (GP = 6), Pcdh7 (13), Ryr1 (22), in CIH they were: Cdh16 (20), Jup (21), Tjp1 (21), while in CCH they were: Cdh13 (18), Pkp4 (21), Mef2d (22). The least prominent genes (higher GPs) in NOR were: Sema3a (96), Atp1a2 (85), Dsc2 (85), in CIH: Cdh2 (94), Ctnnal1 (87), Gja1 (83), and in CCH: Sema3a (93), Adrbk1 (91), Gja1 (89).

Figure 4. The most and the least prominent genes at 1 week.

The components of the intercalated discs were grouped within the right side of each graph and the prominence of Gja1 identified in all conditions. Note how the prominence hierarchy was altered by hypoxia.

Discussion

Our results indicate that, in addition to regulating the expression level of numerous genes, chronic hypoxia profoundly restructured the HRD web and changed the control and the prominence hierarchy of the composing genes. The alterations are complex and strongly dependent on the hypoxia paradigm and duration of exposure to oxygen deprivation. The observed differences between CCH and CIH effects on HRD gene web extend the list of differential alterations induced by intermittent and sustained hypoxia reported in various papers [17-21, 30-1].

The list of disease biomarkers is usually limited to the genes exhibiting significant regulation of the expression level. We took a broader approach by including also the genes whose expression control, maturational profile and coordination are significantly altered in disease, regardless whether their expression level was significantly regulated. Change in expression coordination indicates remodeling of the functional pathway. Increased control results in more accurate transcription level but also in less adaptability to the dynamic environment and therefore change in expression variability reveals updated of transcription control priorities to the new conditions. Altered maturational profile changes the normal dynamics of the “transcriptomic stoichiometry” [25] and thereby the distribution of outcomes of functional pathways, as discussed in previous papers [18, 19].

In evaluating the heart rhythm prominence of the selected genes we considered how much each one controls the HRD web through expression coordination with the other HRD genes and protects the web though its own expression stability. The prominence scores changed during maturation and were altered by hypoxia owing to both network remodeling and modification of transcription control strength. Such changes can be added to numerous reports regarding the heart development after birth (e.g., [32-6]). Remarkably, genes not previously associated with arrhythmia (such are the epigenetic modulators Hdac5, Mef2b, Mef2d) proved to be relevant under certain circumstances, indicating the ability of our Prominent Gene Analysis (PGA) to refine the functional gene webs.

Owing to its high stability and connectivity, Ryr1 (Ryanodine receptor 1, skeletal muscle), a gene with low expression level in the heart, exhibited high HRD prominence because the encoded receptor controls the cytosolic [Ca2+] transients that are essential for the heart rate (e.g. [37]). Slc8a1 is a key player in extruding excessive Ca2+ from the cytosol, thus returning the cardiac myocyte to its resting state following excitation. It participates also in primary cardiac myofibroblast migration, contraction, and proliferation that contribute to post-myocardial infarct wound healing, infarct scar formation, and remodeling of the ventricle remote to the site of infarction [38]. The significant expression synergism of Slc8a1 with Ank2 (essential for membrane organization of sinoatrial node cell channels and transporters and therefore for physiological cardiac pacing [39, 40]) that we found in the heart of 1- and 2-weeks old normoxic mice is in agreement with the results reported when Ank2+/- mice were compared to their wildtype littermates [41]. Moreover, we found a significant synergism of both Slc8a1 and Ank2 with Inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor 1 (Itpr1) in the heart of 2 weeks normoxic and CCH mice (Suppl. Fig. 3).

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy, a genetic cardiomyopathy characterized by ventricular arrhythmias and structural abnormalities of the right ventricle, has been linked to mutations in desmosomal proteins, including Pkp2 [42-4]. PGA revealed that other plakophilins, Pkp3 and Pkp4 have also high HRD prominence and therefore both of them should be included within the arrhythmia biomarkers. Sema3a is important in maintaining normal heart rhythm through sympathetic innervation patterning. Interestingly, both disruption and cardiac-specific overexpression of Sema3a were associated with reduced sympathetic innervation and attenuation of the epicardial-to-endocardial innervation gradient [45]. Cx43 is known to influence the heart rhythm by modulating the innervation of the cardiac tissue. As we have shown by both transcriptomic and immunostaining comparisons of the left ventricles of wildtype and Cx43 null neonatal mice [23], disruption of Gja1 affects synaptogenesis by down-regulating several synaptic proteins (including synaptophysin) and considerably reducing the density of the sympathetic nerve fibers. Therefore, it is not by surprise that we found a significant antagonistic coordination between the expressions of Gja1 and Sema3 in the case of 2 weeks old normoxic mouse. Moreover, this antagonism is preserved in CIH and (less significant) also in CCH.

The significant synergism of Cxadr with Gja1 in almost all conditions (Suppl. Fig. 3) may explain the findings of other groups that the interplay of tight and gap junction proteins is required for normal cardiac function and determines the mechanical and electrical properties of the heart [46, 47]. Moreover, our results confirmed for mouse heart the significant decrease of the expression level of Cxadr after the first week of life in normal conditions (Fig.3A) and the significant up-regulation weeks after infarction (compare Figs. 2B and 2C from this report with Fig. 3 from [48]) observed in rats.

Conclusion

Our results provide additional explanations for chronic hypoxia as being an arrhythmogenic factor and evidence of differential transcriptomic effects induced by constant and intermittent oxygen deprivation. The newly introduced comprehensive criterion (gene prominence) allowed us to rank the HRD biomarkers according to their roles within the HRD gene web and to refine this functional gene web by including genes (such as Pkp3 and Pkp4) not initially reported as related to cardiomyopathy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by the Grants R01HL092001 (DAI) and PO1HD32573 (GGH) awarded by the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute (NHLBI). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the NHLBI official views.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Dursunoglu D, Dursunoglu N. Cardiovascular diseases in obstructive sleep apnea. Tuberk Toraks. 2006;54:382–96. Review. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jain V. Clinical perspective of obstructive sleep apnea-induced cardiovascular complications. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:701–10. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1558. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park AM, Nagase H, Kumar SV, et al. Effects of intermittent hypoxia on the heart. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:723–9. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1460. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schweitzer P. Cardiac arrhythmias in obstructive sleep apnea. Vnitr Lek. 2008;54:1006–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parati G, Lombardi C, Narkiewicz K. Sleep Apnea: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology and Relation to Cardiovascular Risk. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;293:R1671–83. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00400.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Theofilogiannakos EK, Anogeianaki A, Tsekoura PP, et al. Arrhythmogenesis in patients with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2008;9:89–93. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0b013e328028fe73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao Z, Xu H, DiSilvestre D, et al. Transcriptomic profiling of the canine tachycardia-induced heart failure model: global comparison to human and murine heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;40:76–86. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim NH, Ahn Y, Oh SK, et al. Altered patterns of gene expression in response to chronic atrial fibrillation. Int Heart J. 2005;46:383–95. doi: 10.1536/ihj.46.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lai LP, Lin JL, Lin CS, et al. Functional genomic study on atrial fibrillation using cDNA microarray and two-dimensional protein electrophoresis techniques and identification of the myosin regulatory light chain isoform eprogramming in atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2004;15:214–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2004.03423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lamirault G, Gaborit N, Le Meur N, et al. Gene expression profile associated with chronic atrial fibrillation and underlying valvular heart disease in man. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;40:173–84. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mirotsou M, Dzau VJ, Pratt RE, et al. Physiological genomics of cardiac disease: quantitative relationships between gene expression and left ventricular hypertrophy. Physiol Genomics. 2006;27:86–94. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00028.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohki R, Yamamoto K, Ueno S, et al. Gene expression profiling of human atrial myocardium with atrial fibrillation by DNA microarray analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2005;102:233–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2004.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberts R. Genomics and cardiac arrhythmias. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:9–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.08.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liew CC, Dzau VJ. Molecular genetics and genomics of heart failure. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2004;5:811–825. doi: 10.1038/nrg1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mangoni ME, Nargeot J. Genesis and regulation of the heart automaticity. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:919–82. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00018.2007. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsai CT, Lai LP, Hwang JJ, et al. Molecular genetics of atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:241–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.02.072. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fan C, Iacobas DA, Zhou D, et al. Gene expression and phenotypic characterization of mouse heart after chronic constant and intermittent hypoxia. Physiol Genomics. 2005;22:292–307. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00217.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iacobas DA, Fan C, Iacobas S, et al. Integrated transcriptomic response to cardiac chronic hypoxia: translation regulators and response to stress in cell survival. Funct Integr Genomics. 2008;8:265–75. doi: 10.1007/s10142-008-0082-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iacobas DA, Fan C, Iacobas S, et al. Transcriptomic changes in developing kidney exposed to chronic hypoxia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;349:329–38. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.08.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu W, Dave NB, Yu G, et al. Network analysis of temporal effects of intermittent and sustained hypoxia on rat lungs. Physiol Genomics. 2008;36:24–34. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00258.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou D, Wang J, Zapala MA, et al. Gene expression in mouse brain following chronic hypoxia: role of sarcospan in glial cell death. Physiol Genomics. 2008;32:370–9. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00147.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iacobas DA, Urban-Maldonado M, Iacobas S, et al. Array analysis of gene expression in connexin-43 null astrocytes. Physiol Genomics. 2003;15:177–90. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00062.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iacobas DA, Iacobas S, Li WE, et al. Genes controlling multiple functional pathways are transcriptionally regulated in connexin43 null mouse heart. Physiol Genomics. 2005;20:211–223. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00229.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iacobas DA, Iacobas S, Urban-Maldonado M, et al. Sensitivity of the brain transcriptome to connexin ablation. Biochimica et Biofisica Acta. 2005;1711:183–196. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iacobas DA, Iacobas S, Spray DC. Connexin43 and the brain transcriptome of newborn mice. Genomics. 2007;89:113–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iacobas DA, Iacobas S, Spray DC. Connexin-dependent transcriptomic networks in mouse brain. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2007;94:168–184. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2007.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iacobas DA, Iacobas S, Thomas N, et al. Sex-dependent gene regulatory networks of the heart rhythm. Funct Integr Genomics. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s10142-009-0137-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Danik SB, Rosner G, Lader J, et al. Electrical remodeling contributes to complex tachyarrhythmias in connexin43-deficient mouse hearts. FASEB J. 2008;22:1204–12. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-8974com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duffy HS, Fort AG, Spray DC. Cardiac connexins: genes to nexus. Adv Cardiol. 2006;42:1–17. doi: 10.1159/000092550. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Douglas RM, Miyasaka N, Takahashi K, et al. Chronic intermittent but not constant hypoxia decreases NAA/Cr ratios in neonatal mouse hippocampus and thalamus. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;292:R1254–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00404.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farahani R, Kanaan A, Gavrialov O, et al. Differential effects of chronic intermittent and chronic constant hypoxia on postnatal growth and development. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2008;43:20–8. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Azfer A, Niu J, Rogers LM, et al. Activation of endoplasmic reticulum stress response during the development of ischemic heart disease. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;1:H1411–20. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01378.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bruneau BG. The developmental genetics of congenital heart disease. Nature. 2008;451:943–8. doi: 10.1038/nature06801. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harrell MD, Harbi S, Hoffman JF, et al. Large-scale analysis of ion channel gene expression in the mouse heart during perinatal development. Physiol Genomics. 2007;28:273–83. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00163.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Plageman TF, Jr, Yutzey KE. Microarray analysis of Tbx5-induced genes expressed in the developing heart. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:2868–80. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu H, Baldini A. Genetic pathways to mammalian heart development: recent progress from manipulation of the mouse genome. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2007;18:77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.MacLennan DH, Chen SR. Store overload-induced Ca2+ release as a triggering mechanism for CPVT and MH episodes caused by mutations in RYR and CASQ genes. J Physiol. 2009;587:3113–5. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.172155. Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raizman JE, Komljenovic J, Chang R, et al. The participation of the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger in primary cardiac myofibroblast migration, contraction, and proliferation. J Cell Physiol. 2007;213:540–51. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cunha SR, Le Scouarnec S, Schott JJ, et al. Exon organization and novel alternative splicing of the human ANK2 gene: Implications for cardiac function and human cardiac disease. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;45:724–34. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Le Scouarnec S, Bhasin N, Vieyres C, et al. Dysfunction in ankyrin-B-dependent ion channel and transporter targeting causes human sinus node disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:15617–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805500105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mohler PJ, Davis JQ, Bennett V. Ankyrin-B coordinates the Na/K ATPase, Na/Ca exchanger, and lnsP3 receptor in a cardiac T-tubule/SR microdomain. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e423. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Calkins H. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2008;119:273–86. discussion 287-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hatzfeld M. Plakophilins: Multifunctional proteins or just regulators of desmosomal adhesion? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1773:69–77. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Joshi-Mukherjee R, Coombs W, Musa H, et al. Characterization of the molecular phenotype of two arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC)-related plakophilin-2 (PKP2) mutations. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5:1715–23. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ieda M, Kanazawa H, Kimura K, et al. Sema3a maintains normal heart rhythm through sympathetic innervation patterning. Nat Med. 2007;13:604–12. doi: 10.1038/nm1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fischer R, Poller W, Schultheiss HP, et al. CAR-diology-a virus receptor in the healthy and diseased heart. J Mol Med. 2009;87:879–84. doi: 10.1007/s00109-009-0489-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lisewski U, Shi Y, Wrackmeyer U, et al. The tight junction protein CAR regulates cardiac conduction and cell-cell communication. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2369–79. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fechner H, Noutsias M, Tschoepe C, et al. Induction of coxsackievirus–adenovirus-receptor expression during myocardial tissue formation and remodeling: identification of a cell-to-cell contact-dependent regulatory mechanism. Circulation. 2003;107:876–882. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000050150.27478.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.