Abstract

Mycoplasma gallisepticum is a significant respiratory and reproductive pathogen of domestic poultry. While the complete genomic sequence of the virulent, low-passage M. gallisepticum strain R (Rlow) has been reported, genomic determinants responsible for differences in virulence and host range remain to be completely identified. Here, we utilize genome sequencing and microarray-based comparative genomic data to identify these genomic determinants of virulence and to elucidate genomic variability among strains of M. gallisepticum. Analysis of the high-passage, attenuated derivative of Rlow, Rhigh, indicated that relatively few total genomic changes (64 loci) occurred, yet they are potentially responsible for the observed attenuation of this strain. In addition to previously characterized mutations in cytadherence-related proteins, changes included those in coding sequences of genes involved in sugar metabolism. Analyses of the genome of the M. gallisepticum vaccine strain F revealed numerous differences relative to strain R, including a highly divergent complement of vlhA surface lipoprotein genes, and at least 16 genes absent or significantly fragmented relative to strain R. Notably, an Rlow isogenic mutant in one of these genes (MGA_1107) caused significantly fewer severe tracheal lesions in the natural host compared to virulent M. gallisepticum Rlow. Comparative genomic hybridizations indicated few genetic loci commonly affected in F and vaccine strains ts-11 and 6/85, which would correlate with proteins affecting strain R virulence. Together, these data provide novel insights into inter- and intrastrain M. gallisepticum genomic variability and the genetic basis of M. gallisepticum virulence.

Mycoplasma gallisepticum is an avian respiratory and reproductive tract pathogen which has a significant economic impact on the poultry industry in the United States and worldwide. Elucidation of the pathogenic mechanisms by which M. gallisepticum exerts its effects on poultry is critical for the rational pursuit of improved vaccines and control strategies. To date, few virulence determinants or virulence-associated determinants have been identified. Attachment to the respiratory epithelium is essential to host colonization and is mediated by the primary and accessory cytadhesins GapA and CrmA, respectively (16, 46, 51, 53, 54). PlpA (44) and the OsmC-like protein (27) have been shown to bind host extracellular matrix molecules fibronectin and heparin, respectively, potentially aiding in attachment of M. gallisepticum to eukaryotic cells during infection. The OsmC-like protein also confers organic hydroperoxide resistance for M. gallisepticum in the extracellular milieu and may be essential for survival and pathogenesis in the host (28). The numerous lipoproteins encoded by the vlhA gene family have been shown to mediate phase variation of the bacterial surface architecture and are believed to be involved in evasion of the host immune system (5, 15, 18, 42). Metabolic pathways have also been shown to contribute to M. gallisepticum virulence. Dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase (Lpd), a component of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, has been shown to be required for in vivo growth and survival in the host. A mutation in this gene resulted in the generation of the strain designated MG7, which exhibited reduced ability to cause tracheal lesions relative to the virulent progenitor strain Rlow (25).

The need to control the spread of M. gallisepticum on multiage layer farms prompted the development of the live attenuated vaccine (LAV) strains F, ts-11, and 6/85. The F strain is a naturally occurring field isolate originally isolated in the 1950s in the United States (74). It is attenuated in older chickens yet retains virulence in young chickens and turkeys (2, 38). The ts-11 strain is a laboratory-generated, temperature-sensitive mutant produced via chemical mutagenesis of a virulent Australian field strain (73). Strain 6/85 was generated by serial passage of a virulent strain of M. gallisepticum (10). Although all three of these LAV strains are generally considered safe, the efficacy, transmissibility, and residual virulence of these vaccine strains vary considerably (2). Currently, the genetic basis for reduced virulence of these strains is poorly understood.

The virulent, low-passage M. gallisepticum strain R (Rlow) has been serially passaged in broth culture to generate an attenuated high-passage strain (Rhigh) (34). Comparison of these two strains by SDS-PAGE has led to the identification of proteins specifically absent in Rhigh, including GapA, CrmA, PlpA, HatA, and Hlp3 (44, 54). This analytical approach, however, is limited in its ability to detect the full complement of genes/proteins that are missing or disrupted in Rhigh. The complete genome sequence of Rlow was published in 2003 and has proved invaluable in studies of M. gallisepticum pathogenesis (52). Paralogous redundancy was observed in types of genes where plasticity is likely important for survival in the host environment, including 43 vlhA genes arranged in five multigene loci and 24 ABC transporter component genes. Approximately one-third of the predicted M. gallisepticum genes are of unknown function and/or are unique to M. gallisepticum, and these likely include novel genes important for virulence in the host. A comprehensive analysis of which genes are important for M. gallisepticum virulence is lacking.

In order to better understand the genetic basis of virulence in M. gallisepticum, we have utilized genomic sequencing and comparative genomic hybridizations (CGH) to identify genomic differences between virulent and avirulent strains that may relate to virulence. Here, we present complete genome sequence analysis of attenuated M. gallisepticum strains Rhigh and F and compare them to the virulent strain Rlow as well as CGH data identifying features of the Rlow genome absent from the genomes of strains ts-11 and 6/85. These specific genomic differences provide insights into determinants responsible for the avirulent nature of these strains and may provide targets for mutagenesis in the pursuit of development of a more efficacious vaccine.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, growth conditions, and DNA extraction.

M. gallisepticum strains Rlow and Rhigh were obtained from Sharon Levisohn (The Hebrew University Hadassah Medical School, Jerusalem, Israel). Strains ts-11 and 6/85 were obtained from David Ley (College of Veterinary Medicine, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC). The F strain was purchased from Schering-Plough Animal Health (Kenilworth, NJ). All strains were grown in complete Hayflick's medium (23) at 37°C. Clonal isolates (three isolates) of strains Rhigh and F were selected for sequencing. Total genomic DNA was prepared from mycoplasma cultures using an Easy DNA Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. An MGA_1107 isogenic mutant was constructed through random transposon mutagenesis of strain Rlow as previously described (25) and selected using MGA_1107-specific PCR screening of mutant clones.

Library construction.

Random DNA fragments were generated by incomplete digestion of genomic DNA with the restriction endonuclease Tsp509I (New England BioLabs, Beverly, MA). DNA fragments (1.0 to 5.0 kb and 5.0 to 10.0 kb) were size selected using a Zymoclean Gel DNA Recovery Kit (Zymo Research, Orange, CA) and cloned into EcoRI-digested and dephosphorylated pUC19 plasmid (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA) to generate two libraries each for both the Rhigh and F strains. Plasmids were transformed into Escherichia coli One Shot Max Efficiency DH5α T1 chemically competent cells (Invitrogen) and subsequently extracted using a PerfectPrep Plasmid 96 Vac, Direct Bind DNA prep protocol according to the manufacturer's instructions (Eppendorf, Westbury, NY).

Sequencing and assembly.

DNA sequencing reactions were performed in 96-well format using M13 forward and reverse primers and Applied Biosystems (ABI) BigDye Terminator, version 3.1, Cycle Sequencing Kits (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and cleaned via ethanol precipitation. Reactions were run on an ABI 3730xl DNA Analyzer (ABI), and data were collected, bases were determined, and sequences assembled using ABI Data Sequencing Analysis Software (version 5.2), Phred (11), Phrap (http://www.phrap.org), CAP3 (24), and MIRA2 (8), with manual editing using Consed (17). Finishing reactions were performed using custom primers for PCR amplification to close gaps in the assembly. Final, circularized Rhigh and strain F sequences were derived from assemblies containing approximately 10.3-fold and 10.7-fold sequence coverage, respectively.

Reannotation and correction of the Rlow genome.

The genome sequence of the virulent Rlow strain was published in 2003, but our comparative analyses indicated that reannotation was necessary. This included updating gene predictions utilizing the three translational start sites believed to be used by mycoplasmas (ATG, GTG, and TTG) (58) rather than the eight included in NCBI Codon Table 4. The annotation was also updated to include previously undetected functional assignments for unique and conserved hypothetical proteins and new pseudogene information. Loci discrepant between Rlow and Rhigh consensus sequences were manually examined for support at the trace data level. Sequences ambiguous or erroneous in the original Rlow consensus were PCR amplified from the shotgun-sequenced clonal isolate (Rlow clone 2), cloned, sequenced, and corrected if necessary.

TABLE 4.

Rlow genes absent or divergent in vaccine strains as indicated by CGHa

| Locus | Product | Absent or divergentb |

|---|---|---|

| MGA_0581 | ATP synthase subunit beta fragment | D |

| MGA_1328 | Deoxyribose-phosphate aldolase fragment | − |

| MGA_0604 | tRNA modification GTPase MnmE | D |

| MGA_0801 | Subtilisin-like serine protease fragment | − |

| MGA_0802 | Subtilisin-like serine protease fragment | − |

| MGA_0836 | Putative Holliday junction resolvase | D |

| MGA_1108 | Putative transposase fragment | − |

Genes generating negative hybridization signals and verified by PCR.

D, gene present but divergent; −, gene absent.

Sequence analyses.

General nucleotide analyses and comparisons, single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) analysis, and repeat analysis were conducted with DOTTER and programs in the MUMmer, EMBOSS, and REPuter packages (32, 59, 66). Open reading frames (ORFs), potential coding DNA sequences (CDSs), rRNA, and tRNA were identified using EMBOSS, Glimmer (9), and Prodigal (D. Hyatt, L. Hauser, G.-L. Chen, P. Locascio, F. Larimer, and M. Land [http://compbio.ornl.gov/prodigal/]) using a modified genetic code 4 and programs implemented in tRNAscan-SE and RNAmmer (33, 40), respectively. Screening for unusual coding differences in the Rhigh and F genomes (stops and frameshifts) relative to predicted proteins of strain Rlow were conducted using FASTA program packages (55, 56) and BLAST (3). ORFs were used in local searches against nonredundant (NCBI), domain and family profile protein databases, as done previously (52), and against the HAMAP database (37), using BLAST, rpsblast (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/), and HMMer (http://hmmer.wustl.edu/). ORF graphical visualization and manual annotation were aided using Artemis, release 9 (The Sanger Institute, Genome Research Unlimited, United Kingdom). In addition to laboratory computational resources, resources available at the University of Connecticut Biotechnology-Bioservices Center Bioinformatics Facility were used.

CGH.

Oligonucleotide-based microarrays, designed to represent 756 ORFs using Rlow genomic information and used to perform CGH analysis, have been previously described (7). DNA was extracted from mid-log-phase cultures of the respective strains of M. gallisepticum using the manufacturer's protocol 3 of the Easy DNA kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). DNA concentrations were determined from readings of the optical density at 260 nm (OD260), and purity was measured by the OD260/280 ratio using a Thermo Spectronic Biomate 3 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). Four micrograms of genomic DNA was labeled using a BioPrime Array CGH Genomic Labeling System (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), according to the manufacturer's instructions (36), and tagged with Cy3 fluorescent dye (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). Microarrays were hybridized with a single DNA sample overnight at 42°C and washed in decreasing concentrations of SSC buffer (2× SSC plus 0.1% SDS, 1× SSC, 0.1× SSC [1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate]). Image acquisition was performed using a GenePix 4000B microarray scanner (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA) at a photomultiplier tube (PMT) gain of 700. Hybridizations were performed in triplicate.

Analysis of CGH data.

CGH data were analyzed in Microsoft Excel using log2 ratio transformations of the median signal intensity of the test strain compared to the reference strain Rlow [M = log2 μtest/μreference R(low)]. Genes which generated an M value of less than or equal to −2 (4-fold signal reduction in the test strain) were considered to be divergent or absent.

Confirmation of absent or divergent genes.

Genes suspected of being absent or divergent in the attenuated vaccine strains by CGH were confirmed by PCR amplification, cloning, and sequencing. The PCRs were performed with an AmpliTaq DNA Polymerase kit (ABI) using standard procedures and cycling conditions. Initial primers were designed (MWG Biotech, High Point, NC) to be within the ORF and flanking the microarray probe. If a PCR was negative, then a second primer set was designed flanking the ORF. Amplicons were cloned into the Topo TA vector (Invitrogen), and plasmids were extracted using a Qiagen Plasmid Mini kit according to the manufacturer's protocol (Qiagen Inc., Santa Clarita, CA). Sequencing reactions were carried out by MWG Biotech using an ABI capillary DNA sequencer, and contiguous sequences were assembled and analyzed using Sequencher, version 4.2 (Gene Codes Corporation, Ann Arbor, MI) and Artemis, release 9.

Animal challenge experiments.

Challenge experiments were conducted as previously described (12). Briefly, groups of six, 4-week-old, female, specific-pathogen-free, White Leghorn chickens (SPAFAS, North Franklin, CT) were challenged in high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) isolator units, per IACUC protocol (A07-001). Cultures of Rlow and the MGA_1107 mutant were grown from frozen stocks at 37°C with shaking at 130 rpm in fresh Hayflick's medium for 5 h prior to animal inoculation and quantified using the OD620 and color-changing unit (CCU) serial dilutions. Chickens were challenged intratracheally on days 0 and 2 with 200 μl (1 × 108 CFU) of culture or Hayflick's medium alone and humanely sacrificed on day 14 postinoculation.

Chickens were necropsied, and gross pathological findings were noted. Annular segments from cranial, middle, and caudal thirds of the trachea were sampled for mycoplasma isolation and histopathologic assessment. Tissue samples taken for histopathologic study were fixed by immersion in 10% neutral buffered formalin, routinely processed for paraffin embedment, sectioned at 4 μm, and stained using hematoxylin and eosin. Histopathological assessments were conducted in a blinded fashion by a veterinary pathologist, with tracheal scoring adapted from Nunoya et al. (50) and implemented as in Gates et al. (12): 0, no significant findings; 0.5, minimal multifocal lymphocytic or lymphofollicular infiltrates of one to three discrete foci; 1, mild mucosal thickening resulting from (i) multifocal lymphocytic or lymphofollicular infiltrates of four or more discrete foci or (ii) a mild diffuse lymphocytic infiltrate; 2, moderate mucosal thickening resulting from multifocal to diffuse lymphocytic and histiocytic infiltrates with or without lymphofollicular infiltrates or intraepithelial and lamina proprial infiltrates of heterophils; and 3, severe mucosal thickening resulting from diffuse infiltrates of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and heterophils with necrosis or squamous metaplasia of epithelium and luminal exudates. Tracheal sections that varied in severity along segments between two scoring values were assigned mid-range scores, e.g., 1.5 or 2.5. In addition to histopathological lesion scores, tracheal mucosal widths were measured as described previously (25). Using a light microscope and micrometer, the width of the tracheal mucosa was measured from the base of the lamina propria to the top of the epithelium at the base of the cilia. Measurements were made at four equidistant points around the circumference of each tracheal segment. Lesion scores and mucosal widths were analyzed using a nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance on ranks test, with pairwise multiple comparison procedures performed using the Student Newman-Keuls method as implemented in SigmaPlot, version 11 (Jandel Scientific, San Rafael, CA), with a P value of <0.05 used to determine statistical significance.

Tracheal samples taken for mycoplasma isolation were cultured in 5 ml of Hayflick's medium for 4 h, vortexed, and filtered through 0.45-μm-pore-size Millipore filters (Millipore, Billerica, MA) to eliminate nonmycoplasmal contaminants. Cultures that turned acidic (yellow) after being filtered were adjusted to an approximate pH of 7.4 by the addition of 10 N NaOH. Serial 10-fold dilutions prepared to 105 were incubated at 37°C for 28 days to assess CCU.

Accession numbers.

M. gallisepticum strain Rhigh and F genome sequences have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers CP001872 and CP001873, respectively. CGH array data were deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus database under accession number GSM489674.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Reannotation and correction of the Rlow genome.

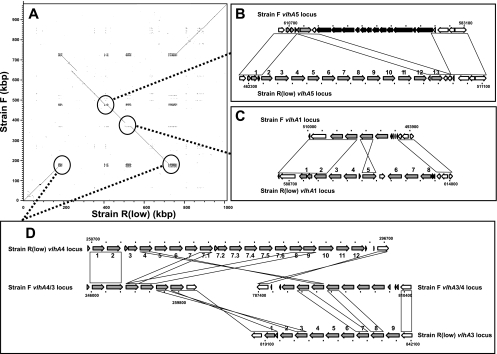

De novo sequencing of the Rhigh genome and comparative analyses ultimately allowed for updates to be made to the previously deposited sequence of the progenitor strain Rlow. These comprised changes at 52 loci and included 19 single nucleotide indels and 21 substitutions, with several leading to incorrect disruption of eight genes (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The changes corrected misassembly in the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) region, a noncoding region characterized by 36-bp exact repeats interspersed by 30-bp unique regions (reviewed in reference 67). Added to the Rlow genome sequence was approximately 2.2 kb of sequence originally excluded from within, and adjacent to, an approximately 1.7-kbp direct repeat within the CRISPR. Also added in the vhlA4 locus region of the Rlow genome was an approximately 14.2-kbp tandem repeat sequence containing six vlhA genes (MGA_1336 to MGA_1342) (Fig. 1, vlhA4.7.1 to vlhA4.7.6). These changes resulted in a revised genome size of 1,012,800 bp for Rlow. Use of standard bacterial start codons altered translational start positions of 419 (58%) previously annotated coding sequences (CDSs), changing their predicted coding and upstream sequences. Finally, reanalysis altered the predicted genetic content of Rlow, with 40 RNA genes, 682 intact CDS gene regions, and 62 potential or likely pseudogenes (784 total genes) now predicted.

FIG. 1.

Major genomic differences between F and R strain genomes. (A) Dot plot of F and Rlow genome sequences. vlhA loci are indicated with dotted lines and expanded to demonstrate gene structure at vlhA5 loci (B), vlhA1 loci (C), and vlhA4/3 loci (D). vlhA genes are indicated with gray arrows and also noted with vlhA numbers in R strain; genes present only in F strain adjacent to the vlhA5 locus are indicated with black arrows. Genes similar and potentially orthologous between the two genomes are indicated with blocks or diagonals.

Genome comparisons of Rhigh and Rlow.

The 156-passage Rhigh genome was 1,012,027 bp in length and highly similar to that of its Rlow parent, exhibiting no large-scale insertions, deletions, or genomic rearrangements. Genomic differences were observed at a total of 64 loci, with the majority comprised of small-scale changes, including 55 indels of which 53 were located in small repetitive tracts (Table 1). This highlights the variable nature of repeats in M. gallisepticum and is consistent with differences in tandem repeat elements observed between strains of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae (70). Twenty-three indels were located in predicted CDSs, and 32 were in noncoding regions, including 29 located in variable GAA repeat sequences involved in phase-variable expression of vlhA genes (14). Noted were only nine substitutions (five transitions and four transversions), six of which were found in ORFs and were nonsynonymous. Thus, of the 29 differences observed in potential coding regions, all introduced amino acid substitutions or indels, translational stops, or frameshifts that might indicate functional protein differences between Rhigh and Rlow (Table 1). Though some of these genomic changes have been previously described, specifically in cytadherence-related genes gapA (54), crmA (51), plpA (52), and hlp3 (44), mutations in additional genes accumulated over 156 in vitro passages likely contribute to the attenuated Rhigh phenotype.

TABLE 1.

Nucleotide and coding differences identified between genomes of Rlow and Rhigh

| Rlow |

Nucleotide difference (Rlow/Rhigh)d | Rhigh |

Locus and/or protein/region | Effect on Rhigh codingb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position (nt)a | Lengthc | Position (nt)a | Length | |||

| 15684 | 1 | G/T | 15684 | 1 | MGA_0644, glycerol kinase | Stop; 157-aa truncation |

| 46081 | 1 | C/T | 46081 | 1 | MGA_0677, glycerol-3-phosphate transport protein | T417I substitution |

| 65904 | 1 | A/C | 65904 | 1 | MGA_0704, conserved membrane protein | Y64D substitution |

| 218873 | 54 | Repeat/— | 218872 | 0 | MGA_0928, adherence-associated protein Hlp3 | 18-aa deletion |

| 223599 | 0 | —/A | 223546 | 1 | MGA_0934, cytadhesin GapA | Frameshift out 995 aa |

| 255751 | 6 | GAA repeat | 255697 | 0 | Intergenic, VlhA4.03 promoter region | |

| 255971 | 12 | Repeat/— | 255911 | 0 | MGA_0968, VlhA4.03a N-terminal fragment | TPNP repeat deletion |

| 260507 | 3 | GAA repeat | 260435 | 0 | Intergenic, VlhA4.05 promoter region | |

| 262821 | 9 | GAA repeat | 262746 | 0 | Intergenic, VlhA4.06 promoter region | |

| 265255 | 3 | GAA repeat | 265171 | 0 | Intergenic, VlhA4.07 promoter region | |

| 269969 | 3 | GAA repeat | 269882 | 0 | Intergenic, VlhA4.07.2a promoter region | |

| 270185 | 0 | —/Repeat | 270097 | 12 | MGA_1336, VlhA4.07.2.a | TP repeat insertion |

| 272304 | 0 | GAA repeat | 272228 | 3 | Intergenic, VlhA4.07.3 promoter region | |

| 274692 | 6 | GAA repeat | 274617 | 0 | Intergenic, VlhA4.07.4 promoter region | |

| 277009 | 9 | GAA repeat | 276928 | 0 | Intergenic, VlhA4.07.5 promoter region | |

| 279442 | 0 | GAA repeat | 279354 | 15 | Intergenic, VlhA4.07.6 promoter region | |

| 282061 | 6 | Repeat/— | 281986 | 0 | MGA_0979, VlhA4.08 | TP repeat deletion |

| 284335 | 1 | T/C | 284255 | 1 | Intergenic, VlhA4.09 | |

| 284341 | 1 | G/A | 284261 | Intergenic, VlhA4.09 | ||

| 284396 | 6 | Repeat/- | 284315 | 0 | MGA_0981, VlhA4.09 | TP repeat deletion |

| 291716 | 6 | GAA repeat | 291629 | 0 | Intergenic, VlhA4.12 promoter region | |

| 307991 | 3 | ATG/— | 307898 | 0 | MGA_1000, RNA polymerase subunit beta | D repeat deletion |

| 358895 | 18 | Repeat/— | 358799 | 0 | MGA_1071, conserved hypothetical protein | TPTPTP repeat deletion |

| 389142 | 1 | C/G | 389029 | 1 | Intergenic, asparaginyl-tRNA synthetase | |

| 393735 | 0 | —/G | 393623 | 1 | MGA_1117/9, CrmB-like protein | ORF fusion |

| 421612 | 1 | G/A | 421500 | 1 | MGA_1161, conserved hypothetical protein | S323N substitution |

| 448139 | 0 | —/Repeat | 448028 | 17 | MGA_1199, fibronectin binding protein PlpA | Frameshift out 166 aa |

| 480523 | 0 | GAA repeat | 480429 | 3 | Intergenic, VlhA5.03 promoter region | |

| 483041 | 0 | GAA repeat | 482950 | 6 | Intergenic, VlhA5.04 promoter region | |

| 487897 | 9 | GAA repeat | 487810 | 0 | Intergenic, VlhA5.06 promoter region | |

| 490341 | 0 | GAA repeat | 490247 | 33 | Intergenic, VlhA5.07 promoter region | |

| 492725 | 0 | GAA repeat | 492664 | 3 | Intergenic, VlhA5.08 promoter region | |

| 495034 | 3 | GAA repeat | 494974 | 0 | Intergenic, VlhA5.09 promoter region | |

| 495312 | 13 | 13 bp/7 bp | 495250 | 7 | MGA_1251, VlhA5.09 | TP repeat deletion |

| 497434 | 48 | GAA repeat | 497365 | 0 | Intergenic, VlhA5.10 promoter region | |

| 499881 | 18 | GAA repeat | 499764 | 0 | Intergenic, VlhA5.11 promoter region | |

| 594921 | 3 | GAA repeat | 594786 | 0 | Intergenic, VlhA1.02 promoter region | |

| 597248 | 12 | GAA repeat | 597110 | 0 | Intergenic, VlhA1.03 promoter region | |

| 599667 | 6 | GAA repeat | 599517 | 0 | Intergenic, VlhA1.04 promoter region | |

| 606824 | 0 | GAA repeat | 606670 | 12 | Intergenic, VlhA1.06 promoter region | |

| 609365 | 12 | GAA repeat | 609221 | 0 | Intergenic, VlhA1.07 promoter region | |

| 611661 | 3 | GAA repeat | 611505 | 0 | Intergenic, VlhA1.08 promoter region | |

| 657054 | 1 | A/C | 656896 | 1 | MGA_0141, nucleotide phosphodiesterase | N56K substitution |

| 670334 | 6 | Repeat/— | 670175 | 0 | MGA_0162, dihydrolipoamide acetyltransferase | GG repeat deletion |

| 672071 | 0 | —/CTT | 671908 | 3 | MGA_0165, pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 subunit | E repeat insertion |

| 677821 | 0 | —/TGTATTTG (repeat) | 677661 | 8 | MGA_0173, TlyC-like protein | Frameshift out 67 aa |

| 711767 | 0 | —/GA (repeat) | 711615 | 2 | MGA_0221, ABC peptide transport permease | Frameshift out 99 aa |

| 713340 | 20 | Repeat/— | 713188 | 0 | MGA_0223/4, ABC peptide transport permease | ORF fusion |

| 723519 | 1 | T/C | 723348 | 1 | MGA_0237, ABC peptide transport solute BP | D467G substitution |

| 736772 | 0 | —/T (repeat) | 736602 | 1 | MGA_0250, unique hypothetical | 61-aa N-terminal extension |

| 740191 | 37 | Repeat/— | 740020 | 0 | MGA_0256/8, phase variable protein PvpA | ORF fusion |

| 757659 | 12 | Repeat/— | 757451 | 0 | MGA_0287, amino acid permease | 4-aa C-terminal deletion |

| 815905 | 3 | GAT/— | 815685 | 0 | MGA_0368, ABC transport permease | I repeat deletion |

| 821389 | 0 | GAA repeat | 821168 | 21 | Intergenic, VlhA3.01 promoter region | |

| 822227 | 0 | —/ATAT (repeat) | 822027 | 4 | MGA_0379, VlhA3.02 | Frameshift out 218 aa |

| 823701 | 0 | GAA repeat | 823505 | 3 | Intergenic, VlhA3.02 promoter region | |

| 828562 | 12 | GAA repeat | 828367 | 0 | Intergenic, VlhA3.05 promoter region | |

| 833126 | 0 | —/TGGAGT | 832921 | 6 | MGA_0388, VlhA3.06 | TP repeat insertion |

| 835662 | 0 | GAA repeat | 835463 | 12 | Intergenic, VlhA3.07 promoter region | |

| 840488 | 3 | GAA repeat | 840299 | 0 | Intergenic, VlhA3.09 promoter region | |

| 910723 | 581 | 581 bp/— | 910531 | 0 | MGA_0508, fructose-specific PTS component | N-terminal deletion |

| 929813 | 66 | Repeat/— | 929040 | 0 | CRISPR | Repeat deletion |

| 930766 | 0 | —/Repeat | 929929 | 66 | CRISPR | Repeat insertion |

| 938625 | 1 | A/— (repeat) | 937852 | 0 | Intergenic, MGA_0536 ATPase and MGA_0537 hsdM | |

nt, nucleotide.

aa, amino acids.

Length in nucleotides.

Specific nucleotides, length of nucleotide sequences, and/or the presence of repeated sequences noted as indels or substitutions between Rlow and Rhigh are given.

Among the genes truncated in Rhigh, two are involved with sugar metabolism, the regulation of which is thought to play a major role in the survival and virulence of mycoplasmas in vivo (reviewed in reference 21). The glycerol kinase gene glpK (MGA_0644) and the fructose/mannose-specific IIABC component gene fruA (MGA_0508) (60) of the phosphoenolpyruvate:fructose phosphotransferase system (PTS) are likely inactive, as both lack significant portions of coding sequence (157 and 179 amino acids, respectively). The fruA lesion (a deletion of 581 bp) is the largest indel observed between Rlow and Rhigh. These genes are predicted to be necessary for transport/utilization of what is believed to be the three primary alternative carbon sources (glycerol, fructose, and mannose) used by M. gallisepticum in glycolysis and subsequent ATP production. Glycerol catabolism has also been implicated in mycoplasmal virulence as it yields very high concentrations of H2O2 per mole of O2 and glycerol consumed (68). In Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. mycoides biotype small colony, glycerol uptake and utilization are strongly correlated with virulence. It is critical for the production of cytotoxic hydrogen peroxide by bacterial l-alpha-glycerophosphate oxidase (GlpO), which catalyzes the oxidation of glycerol-3-phosphate and release of H2O2 (6, 57, 71). M. gallisepticum encodes a homolog (MGA_0646) of the Mycoplasma pneumoniae GlpO, encoded by a glycerol dehydrogenase-like gene (glpD; MPN051), which was recently shown to mediate H2O2 production, thereby affecting host-cell cytotoxicity (22). Thus, glycerol uptake and conversion to H2O2 are potentially significant in M. gallisepticum virulence. The loss of GlpK function could conceivably result in reduced levels of glycerol-3-phosphate available for GlpO-mediated H2O2 production. Notably, one of the observed amino acid substitutions in Rhigh occurs within the ATP binding region of a putative ABC-type, sn-glycerol-3-phosphate transport system ATP-binding protein (MGA_0677), making a functional change in glycerol-3-phosphate transport also a possibility. PTS components have also been implicated as virulence factors. The plant pathogen Spiroplasma citri requires fructose PTS activity for virulence (13), and PTS functions and carbohydrate metabolism have been linked with in vivo survival in extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli (61). The fruA PTS component may also have a conceivable role in M. gallisepticum virulence.

Disrupted in Rhigh are other genes with limited functional commonality. Two disrupted genes had highly similar paralogs elsewhere in the genome and encoded a potential ABC-type peptide/nickel transporter permease (MGA_0221) and a member of the variable lipoprotein family, vlhA3.02 (MGA_0379). These genes have coding sequences that are frameshifted relative to orthologs in Rlow, with Rhigh MGA_0221 lacking two transmembrane helices and a potential substrate binding domain and Rhigh vlhA3.02 lacking the C-terminal 218 amino acids present in Rlow. Paralogs of these genes conceivably provide equivalent functions and thus directly complement MGA_0221 and MGA_0379 mutations. Conversely, disruption in these genes may indicate loss of, and/or functional shift away from, very specific transport or attachment functions affecting virulence, with paralogs conceivably complementing functions with different specificity.

Also disrupted in Rhigh was a gene with no obvious function, the conserved hypothetical gene MGA_0173. Identified in MGA_0173 was a tlyC domain which consists of a duf21 (domain of unknown function) transmembrane domain and a CBS domain potentially involved in ligand binding. MGA_0173 was also similar to M. pneumoniae tlyC, a gene proposed to encode a hemolysin but noted by other investigators as lacking a hemolysin domain (GenBank accession NP_109847). Despite the lack of obvious function for this gene, its disruption in Rhigh makes it an obvious target for investigation as a potential virulence determinant.

Genomic comparison of strains Rlow and F. (i) General comparison.

The F strain genome was similar to that of R strain, sharing 747 predicted gene orthologs in largely syntenic genomic regions. The F strain was predicted to contain 781 total genes, including 688 intact CDS genes and 53 potential or likely pseudogenes. Despite sharing similar overall genomic content, however, the F strain demonstrated features indicating that it is clearly distinct from the R strain. Overall, F strain genes were 2.7% divergent at the amino acid level relative to orthologs in strain R, indicating significant genetic distance between these two strains of the species M. gallisepticum. The F strain genome was 977,612 bp in length, approximately 35 kbp shorter than that of R strain, largely due to a unique and reduced vlhA gene complement. Notable large-scale genomic differences included a genomic inversion of approximately 500 kbp between the vlhA3 locus and the vlhA4 locus (Fig. 1A) and approximately 17 kbp of novel sequence present in the F strain and absent in the R strain (Fig. 1B). Notable in the F strain genome was an insertion of a tandem duplication of approximately 25.7 kbp (duplicated within positions 305536 to 356916) which contained 17 genes corresponding to R strain MGA_0271 to MGA_0312. Other larger-scale indels in non-vlhA and non-CRISPR regions were limited (18 indels of 100 bp or more), with 14 of these present in regions containing only transposons and/or potential pseudogenes in both strains but with others affecting intact genes (Table 2). A total of 126 genes exhibited length differences between F and R strains, but most of these resulted in minor internal or terminal changes in affected proteins (52 genes), amino-terminal changes which likely reflected incorrect start codon prediction (17 genes), or changes in genes predicted to be fragmented in both strains (22 genes). Changes did, however, account for at least 25 F strain genes potentially intact or disrupted relative to strain R orthologs (Tables 2 and 3). Differences in coding potential were examined for clues as to the genetic basis of M. gallisepticum virulence. Of particular interest were differences in genes absent, disrupted, or highly divergent in strain F relative to strain R (Fig. 1 and Table 2; see also Table S2 in the supplemental material).

TABLE 2.

Genes fragmented or absent in strain F relative to strain Ra

| F strain locus | Gene change(s)b | R strain locus | Predicted gene product |

|---|---|---|---|

| MGF_0026f | Fr | MGA_0626 | ABC-type multidrug/protein/lipid (MdlB-like) transport system component |

| MGF_0725 | Fr, I | MGA_0798 | Subtilisin-like serine protease |

| MGF_0748f | Fr | MGA_0805 | Putative ABC-type transport system protein |

| MGF_1439 | Fr | MGA_0957 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| MGF_1750f | Fr | MGA_0323 | Conserved hypothetical membrane protein |

| MGF_1948 | Fr | MGA_0271 | Unique hypothetical protein |

| MGF_2099f | Fr | MGA_1361 | Unique hypothetical protein |

| MGF_3286 | N, Fr | MGA_1305 | MaoC-like dehydratase |

| MGF_3677f | Fr | MGA_1220 | Arginine deiminase |

| MGF_4156 | N | MGA_1100 | Asparaginyl-tRNA synthetase |

| I | MGA_1107 | Conserved hypothetical RmuC-domain protein | |

| MGF_4199 | Fr, I | MGA_1083 | HAD superfamily hydrolase |

| MGF_4219f | Fr | MGA_1081 | Putative transposase |

| MGF_4466 | N | MGA_1027 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| MGF_4633 | Fr | MGA_1343 | Unique hypothetical protein |

| MGF_5191f | Fr | MGA_0516 | Unique hypothetical protein |

| MGF_5319f | Fr | MGA_0541 | Type I site-specific restriction-modification system restriction (R) subunit |

| MGF_5453 | B | MGA_0566 | Unique hypothetical protein |

| MGF_5461/3 | B | MGA_0567 | Unique hypothetical protein |

Genes shorter by at least 10% in length by deletion, frameshift, or premature stop relative to intact ortholog, and not likely the result of incorrect start codon prediction.

Fr, gene fragmented relative to R strain; N, gene encoding protein lacking amino-terminal region relative to R strain; I, gene affected by indel event (>100 bp) relative to strain R; B, gene potentially fragmented in both R and F strains.

TABLE 3.

Genes intact or present in strain F relative to strain Ra

| F strain locus | Gene changeb | R strain locus | Predicted gene product |

|---|---|---|---|

| MGF_0017 | F | MGA_1322d/625 | ABC-type multidrug/protein/lipid (MdlB-like) transport system component |

| MGF_0872 | F | MGA_0829 | conserved hypothetical lipoprotein |

| MGF_1196 | F | MGA_0908/11 | unique hypothetical membrane protein |

| MGF_2103 | I | putative transposase | |

| MGF_2868 | I | putative transposase | |

| MGF_3370 | F | MGA_1284/5 | ABC transporter ATP-binding protein |

| MGF_3373 | I | unique hypothetical protein | |

| MGF_3468 | F | MGA_1350 | hypothetical protein fragment |

| MGF_3470 | Iu | MGA_1349 | conserved hypothetical protein |

| MGF_3484 | Iu | conserved hypothetical protein | |

| MGF_3486 | Iu | ABC-type maltose/maltodextrin transporter permease MalC | |

| MGF_3501 | Iu | ABC-type maltose/maltodextrin transporter permease MalG | |

| MGF_3505 | Iu | ABC-type maltose/maltodextrin transporter ATP-binding protein MalK | |

| MGF_3514 | Iu | unique hypothetical protein | |

| MGF_3519f | Iu | alpha amylase superfamily protein (fragmented) | |

| MGF_3529 | Iu | GntR-family transcriptional regulator | |

| MGF_3537 | Iu | pullulanase | |

| MGF_3555 | Iu | putative alpha,alpha-phosphotrehalase | |

| MGF_3567 | Iu | MGA_1265 | maltose phosphorylase |

| MGF_3987 | F | MGA_1364 | unique hypothetical protein |

| MGF_4139 | I | putative transposase | |

| MGF_4207f | I | MGA_1083 | PTS lichenan-specific IIA component (fragmented) |

| MGF_4515 | F | MGA_1014 | unique hypothetical protein |

| MGF_5077 | F | MGA_0487 | conserved hypothetical protein |

| MGF_5456 | B | MGA_1358 | unique hypothetical protein |

| MGF_5547 | F | MGA_0583/4 | conserved hypothetical protein |

Genes longer by at least 10% in length by deletion, frameshift, or premature stop relative to intact ortholog, and not likely the result of incorrect start codon prediction.

F, F strain gene of full-length relative to R strain; I, gene encoded in sequence present in F strain but absent in R strain; Iu, gene encoded in 17-kbp unique region; B, gene potentially fragmented in both R and F strains.

(ii) vlhA gene regions.

The F strain genomic regions most variable relative to strain R contained vhlA genes. vlhA loci displayed divergent and nonsyntenic gene complements suggestive of local and inter-vlhA rearrangements and paralogous gene gain/loss, with only the two-gene vlhA2 locus highly conserved between F and R strains (Fig. 1B to D). Indeed, the F strain contained 23 vlhA genes (20 intact), 28 fewer than the 51 present (44 intact) in Rlow. Intact VlhA ORFs demonstrated lower average amino acid identity (88%, ranging from 61 to 99%) to R strain homologs than did non-VlhA homologs (98%). One intact F strain vlhA ORF (MGF_4735; predicted 75-kDa protein) was notably divergent from VlhA ORFs in the R strain (59% amino acid identity to VlhA4.11) yet more similar (73%) to the strain S6 ORF pMGA 1.4 (43). A 75-kDa immunodominant protein specific to the F strain has been previously described (30, 69); however, whether MGF_4735 encodes this protein remains to be shown. The nonsyntenic nature of many interstrain VlhA best-matches and the presence of a large genomic inversion, gene duplication, and indels suggested recombination in and around vlhA loci (Fig. 1). This included potential vlhA3-vlhA4 locus rearrangement bounding the genomic inversion, where genes present in the 3′ region of each R strain locus appear to have recombined and switched positions, resulting in the vlhA3/4 locus and the vlhA4/3 locus in the F strain (Fig. 1D). Additional complexity at these and other vlhA loci makes elucidation of discrete rearrangement events speculative. In addition, the unique 17-kbp sequence adjacent to the vlhA5 locus in the F strain is essentially in the same locus as most vlhA5 locus genes present in the R strain (Fig. 1B).

vlhA genes encode immunodominant lipoproteins and hemagglutinins that undergo phase-variable expression both in vitro and in vivo (5, 15, 41), and they are thought to be virulence determinants which facilitate establishment of chronic infection through immune evasion. Overall, the divergence between F and R strain loci was extreme relative to the single vlhA gene disruption observed between Rhigh and Rlow and, regardless of mechanism, was consistent with phase-variable gene locus variation observed between strains of other mycoplasma species (62). Extreme variation in vlhA complement, be it phase-variable expression or interstrain genetic heterogeneity, likely reflects significant disruptive selective pressure exerted on these genes as they encode major immune targets, and it likely results in elicitation of different serological specificities in the host. Whether frameshifted vlhA genes are expressed directly or though recombination with other vlhA genes, as seen in Mycoplasma synoviae (49), is unknown; however, these, too, could conceivably contribute to antigenic variation in the host. Similarly, a recombinatorial effect on gene order and ultimately phase variation is not known in M. gallisepticum, nor is such a mechanism obvious, given the data here. Notably and despite this variation in vlhA complement, F strain continues to induce immune responses that are generally protective against distinct strains.

(iii) Transposons.

Transposons are mobile genetic elements encoding transposases and are capable of random genomic integration, disruption of coding sequences, and/or mediating movement of nontransposon sequence within or between organisms. Such transposon-mediated changes likely occurred between F and R strains as their transposase gene loci demonstrated variability. These included two distinct F strain transposase insertions (MGF_2103 and MGF_2868) into intergenic regions upstream of potential lipoproteins (MGF_2102 and MGF_2118) and a ribosomal protein. A third F strain transposase gene (MGF_4139) was intact, and it essentially replaced a 2,441-bp locus which contained both transposase gene fragments (MGA_1108/9) and a conserved protein gene (MGA_1107) present in strain R. MGF_4139 was similar to MGA_0910 transposase, which at a different locus disrupts the MGA_0908/0911 hypothetical transmembrane protein (multigene family) gene in strain R but is absent in strain F, leaving an intact MGA_0908/0911 ortholog (MGF_1196) (Table 3). Although a direct transposition between these two loci is possible, similarity to other M. gallisepticum transposases and remnants of MGF_4139 in R strain sequence leave this unclear. Overall, strain F contains 14 transposase genes (3 intact) relative to the 16 genes (2 intact) present in strain R. In addition, transposons may affect indel events in adjacent genes, as six genes with coding potential affected by larger indels in F strain relative to the R strain were adjacent to transposon loci.

(iv) MGA_1107 and virulence assessment.

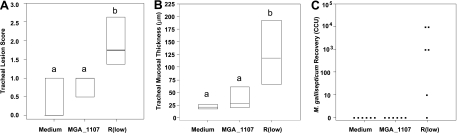

Transposon-mediated genomic changes ultimately may act to alter virulence, host range, or tissue tropism. Notably, this may be the case for the R strain MGA_1107 gene, which again is adjacent to transposase genes and is absent in the F strain. MGA_1107 contains a domain shared among proteins involved in DNA metabolism, including proteins similar to the putative nuclease RmuC, thought to affect DNA recombination of short inverted repeat sequences in E. coli (31, 65). MGA_1107 also shares a relatively high level of amino acid identity (92%) with M. synoviae MS53_0172, indicating that the MGA_1107 gene, and perhaps flanking transposon sequences, have involved or mediated a horizontal gene transfer (HGT) event, consistent with previous observation of a likely vlhA HGT between M. synoviae and M. gallisepticum (48, 70). MGA_1107 genes were identical between Rlow and Rhigh (Table 1). Based on these genomic data and on previous data indicating that MGA_1107 is transcriptionally upregulated in Rlow upon exposure to cells to which M. gallisepticum binds (7), an isogenic mutant of MGA_1107 was assessed in a chicken challenge system for virulence in vivo. Though lung lesions and minor airsacculitis were induced by the MGA_1107 mutant, lung and air sac lesions have been previously reported to be significantly variable in this experimental system and thus are precluded from being used for quantitative purposes (54). Tracheal mucosal thickness was reduced compared to that in the wild type, and histopathological lesion scores were similar to those of negative-control birds (P < 0.05, analysis of variance [ANOVA] on ranks and posthoc pairwise comparison) (Fig. 2). This mutant was recovered from lung and air sac tissues (albeit to a lesser degree than Rlow) but was unrecoverable from the trachea. These data indicate that MGA_1107 contributes in a yet uncharacterized manner to the generation of tracheal lesions typical of virulent M. gallisepticum infection in vivo and that the loss of this ORF may be a factor in the attenuated phenotype of the F strain. This experimental evidence illustrates the utility of the approach of genomic comparison of virulent and attenuated strains in identifying genetic factors that influence survival in the host or the production of lesions.

FIG. 2.

Attenuation of MGA_1107 mutant of R strain in chickens. (A) Histopathological lesion scores in tracheas of chickens infected with Hayflick's medium (Medium), mutant (MGA_1107) organism, and virulent organism (Rlow). Horizontal bars indicate 25th percentile (bottom), median, and 75th percentile (top). Lowercase letters indicate statistically similar groups. (B) Tracheal mucosal thickness. Bar and letters are as described for panel A. (C) Microbiological recovery from tracheas of chickens. Dots indicate titers of samples recovered from individual birds.

(v) Subtilisin-like proteases.

Indels occurred within subtilisin-like protease genes, of which there are five paralogs (three intact) encoded in the R strain. F strain lacks 1,693 bp encoding the majority of the MGA_0798 subtilisin-like gene intact in the R strain. A similarly sized deletion (1,686 bp) removed the majority of the nearby MGA_0801 subtilisin-like locus; however, MGA_0801 was a likely pseudogene and thus was predicted to be nonfunctional in both strains. Orthologous, but fragmented, MGF_5102F and MGA_0517/8 subtilisin-like loci also demonstrated coding variation, with two frameshifts restoring all but the likely N terminus to MGF_5102F. Subtilisins are a ubiquitous family of proteases with a range of functions, including roles in bacterial virulence. All five genes in the R strain belong to the D-H-S subgroup of subtilases encoded in other pathogenic bacteria, including Bacillus anthracis (reviewed in reference 63). Other essential subtilases conferring microbial virulence include dentilisin and SufA. Dentilisin is used by the oral spirochete Treponema denticola to degrade host chemokines, cytokines, and fibrinogen (4, 45) and to rearrange the bacterial outer sheath (26). SufA, encoded by the Gram-positive bacterium Finegoldia magna (an opportunistic pathogen of humans), inactivates antimicrobial peptides and chemokines and is believed to aid in bacterial survival in the host (29).

(vi) HAD-like proteins.

Also affected by indels were genes encoding potential hydrolases of the haloacid dehalogenase (HAD) superfamily, of which strain R contains five paralogs. MGF_4199 lacked the PTS-like N-terminal domain of the R strain ortholog (MGA_1083), a fusion reflecting deletion of additional PTS lichenan-specific IIA component gene sequences (present as fragments in F strain MGF_4207f) from strain R. Two HAD hydrolase genes were duplicated in the 24-kbp tandem repeat, yielding seven HAD hydrolase loci in F strain. Though functions of mycoplasmal subtilases and HAD hydrolases are unknown, the presence of, and variability among, multiple copies in M. gallisepticum suggest a role in host interaction and pathogenesis.

(vii) hsd genes.

Disrupted or variable in the F strain relative to the R strain were host specificity of DNA (hsd) genes adjacent to a fragmented transposase (MGF_5343f). These encode protein subunits of a type I restriction-modification system (R-M) complex which mediates methylation (modification subunit, hsdM), sequence-specific recognition of methylation state (specificity, hsdS), and restriction enzyme activity (hsdR). The F strain hsdR gene (MGF_5319f) is prematurely terminated at nucleotide position 2307 (of 3,198), possibly resulting in a loss of restriction enzyme function. HsdS often contains N- and C-terminal domains of similar structures, but each has discrete sequence specificities (or target recognition domains). Both the R and F strains, however, encode two separate single-domain HsdS units, akin to a single N-terminal domain and similar to the single-domain ORFs present in M. pneumoniae and other bacteria. This is consistent with data indicating that single-domain dimerization confers proper HsdS function in E. coli (1). Notably, while the first copy of HsdS is identical between R and F strains (MGF_5309/MGA_0539), the central domain of the second copy (MGF_5313/MGA_0540) is highly divergent, with little recognizable nucleotide similarity.

Hsd systems primarily protect bacteria from large fragments of foreign DNA such as those encountered during bacteriophage infection and which may interfere with normal cellular processes (reviewed in reference 47). Mycoplasma pulmonis encodes a unique hsd system that undergoes phase-variable gene expression and generates hsdS sequence variation (and likely target sequence specificity) through sequence-specific recombination between two distinct hsd loci (64). In addition, M. pulmonis hsd expression has been associated with bacterial tissue tropism as expression becomes active in the lower, but not upper, respiratory tissues of rodent hosts in vivo (19). While the extreme sequence divergence observed here between orthologous MGF_5313 and MGA_0540 genes could conceivably be generated through a recombination process, lack of both a second hsd locus and obvious inverted repeats bounding the divergent hsdS domain makes this unlikely. Though a role for the hsd system in M. gallisepticum host range and/or virulence is speculative, hsd genes do appear to be under different selective pressures in the R and F strains.

(viii) Transport proteins.

Though none appeared to involve glucose metabolism, multiple solute transporter-like genes were variable in F strain relative to R strain. These included two genes fragmented and two genes intact in F strain relative to R strain. Fragmented in F strain were MGF_0748f, a protein with weak similarity to ABC-transport proteins, and MGF_0026f, a prematurely terminated ortholog of the intact MGA_0626 mdlB-like gene in R strain. MGF_0026f contained a stop site located between the ABC transporter transmembrane domain and the ATP binding domain, likely affecting this protein, which is similar to proteins involved in multidrug efflux and transport of lipids and proteins. Conversely, intact in F strain relative to R strain were MGF_0017, a second mdlB-like gene adjacent to the fragmented MGF_0026f paralog, and MGF_3370, an intact ATPase component of an ABC transport protein of unknown specificity. The MGF_3378f locus contained a fragmented ortholog of the MGA_1283 mtlA-like gene in R strain; however, MGA_1283 itself is similar only to the C-terminal EIIB domain of MtlA. MtlA is a PTS transporter for mannitol and, although all genes required for mannitol utilization are present in the members of the pneumoniae clade, this system does not appear to work in M. pneumoniae (20), and mannitol transport has been reported to be absent in M. gallisepticum strain NCTC 10115 (68). The variability between F and R strains in multiple solute transport proteins indicates that, again, they may affect growth and survival in different hosts or host tissues, likely affecting virulence.

(ix) Other disrupted strain F genes.

Other genes disrupted in F strain relative to R strain have metabolic functions or are of unknown function (Table 2). MGF_3677f is a highly fragmented arcA gene encoding arginine deaminase and is intact in R strain (MGA_1220). MGF_4156 encodes a protein orthologous to the MGA_1100 asparaginyl-tRNA synthetase in strain R, including the AspRS/AsnRS core domain; however, it lacks an N-terminal domain conserved in other species. While these changes potentially affect F strain metabolism, paralogs (MGF_2849 and MGF_4297) conceivably provide compensatory functions. Four conserved and six unique hypothetical proteins are fragmented in F strain relative to R strain. One genomic region containing four small hypothetical proteins (MGF_5453 through MGF_5463) is highly variable between F and R strains, suggesting that, although no intact homolog has been observed, these may represent fragments of a novel gene.

(x) Highly divergent genes.

Many genes demonstrated above-average amino acid divergence between F and R strains (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). While 173 intact F ORFs were identical to R strain homologs at the protein level, the rest differed on average by 2.4%. Among the most divergent protein homologs were those similar to known or putative cytadhesins and cytadherence-related proteins (Table S2). Indeed, of the 37 intact ORFs differing between strains by 5% or more, nine (24%) are putatively involved in cytadherence or tip structure formation, including GapA, CrmA, CrmB, MGC2, and several ORFs with similarity to HMW cytadhesin-related proteins. Also divergent is PvpA, a protein that is localized to the terminal tip structure, undergoes phase variation under antibody pressure both in vitro and in vivo, and is potentially involved in antigenic variation and immune evasion in the host (35, 75). Genomic sequences presented here confirm the loss of about 230 nucleotides previously reported in the direct repeat 1 (DR1) and DR2 regions in the F strain relative to the R strain (39).

(xi) Genes present or functionally intact in strain F.

In addition to genes absent or disrupted, the F strain genome contains several genes that are absent in the R strain genome or that are intact relative to homologs in strain R (Table 3). The most striking of these included the 11 genes present in the approximately 17-kbp sequence adjacent to the F strain vlhA5 locus (Fig. 1). This “17-kbp locus” includes genes involved in acquisition, transport, and metabolism of maltose/maltodextrin and other sugars (Table 3). The ORFs at the 17-kbp locus shared homology with syntenically conserved or semiconserved loci in other mycoplasmas, in particular, members of the hominis group (72). This includes similarity to Mycoplasma fermentans, in which the entire locus was conserved in content and was highly similar at the amino acid level (27% to 71%), and to M. synoviae, another poultry pathogen which contains three genes of the locus which also are highly similar to those in the F strain (59% to 62% amino acid identity). Notably, homologs of genes in this locus were not obvious in other species of the pneumoniae group to which M. gallisepticum belongs. Thus, the 17-kbp locus may have been the product HGT from a species from the hominis group, conceivably a common ancestor of M. fermentans and M. synoviae. In addition, two genes bounding the 17-kbp locus in the F strain (MGF_3470 and MGF_3567) are present as remnants in the R strain (MGA_1349 and MGA_1265, respectively), indicating that the locus was lost from the R strain subsequent to its introduction to M. gallisepticum.

Other genes in the F strain represent genes intact relative to fragments present in strain R (Table 3). MGF_5077 encodes a conserved hypothetical protein fragmented in the R strain (MGA_0485 and MGA_0487) and is located at the 5′ end of the FoF1 ATP synthase operon, where it conceivably plays a part in energy production. The MGF_4515 unique hypothetical protein contains an additional C-terminal 35 amino acids relative to the R strain MGA_1014, which contains a frameshift. Similarly, the MGF_0872 conserved hypothetical lipoprotein gene contains an additional C-terminal 141 amino acids relative to MGA_0829, potentially affecting a surface-exposed domain and the ability to interact with the host. How these and other intact genes affect the phenotype of strain F relative to strain R is unknown, but they conceivably mediate virulence or host range functions.

Notably, sequence analyses using Rhigh and F strains enabled identification of differences in the genome sequence of Rlow that were likely specific to the particular clone selected for sequencing (Rlow clone 2) (52). These included the 37-bp frameshifting insertion noted in pvpA (52) and mutations in the MGA_0223/4 ABC-transporter permease, MGA_0250 unique hypothetical protein, and MGA_1117/9 cytadherence-related molecule B (crmB)-like protein genes that disrupted coding potential in Rlow clone 2. While the effect of these changes on the phenotype of Rlow clone 2 relative to the Rlow wild-type population is unknown, the comparative genomics approach proved a powerful means to discern them.

CGH of vaccine strains.

Comparative genomic hybridizations of the three commercially available vaccine strains (F, ts-11, and 6/85) were performed, and the fold difference relative to results obtained with Rlow were determined. In an attempt to identify gene divergence/loss associated with M. gallisepticum attenuation, focus was given to features absent in all vaccine strains relative to Rlow. Only seven non-vlhA and non-CRISPR region probes hybridized 4-fold or less in all the vaccine strains compared to Rlow, and these genomic lesions were further probed with PCR and sequencing (Table 4).

Of the seven gene features absent in all vaccine strains, five are located in likely gene fragments and verified subtilisin and transposase gene loci affected by indels in F strain genome analysis (Table 4). Although divergence or loss of sequence within pseudogenes might be expected, these data verified their absence in vaccine strains. Sequences for a GTPase similar to the tRNA modification protein MnmE (MGA_0604) and a putative Holliday junction resolvase (MGA_0836) gene were confirmed to be present in vaccine strains by sequencing, with SNPs within sequence spanning the 50-mer probe responsible for the lack of hybridization signal. Whether divergence in these enzymes might contribute to an attenuated phenotype remains to be proven. In addition to genes that are missing in all three vaccine strains, multiple features were observed to be divergent or absent in only one or two strains (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). Strain-specific phenotypes may be associated with these mutations, supporting the conclusion that M. gallisepticum virulence is complex and multigenic.

Conclusions.

In this study, we used comparative genomic analyses of virulent and attenuated M. gallisepticum strains to identify determinants involved in pathogenesis and survival in the host. Genomes of the attenuated high-passage derivative, Rhigh, and heterologous vaccine strain F were sequenced and compared to the known genome sequence of the virulent, low-passage strain Rlow, revealing mutations in numerous genes and indicating a range of protein functions potentially involved in virulence. While these included suspected or known cytadherence-related functions, which are of primary importance for M. gallisepticum virulence, other novel virulence determinants were indicated. Relative to other genomic changes, those associated with the vlhA major variable lipoprotein genes were highly represented—as promoter region variability in strain Rhigh and as a highly divergent gene complement in strain F—supporting the notion that vlhA gene expression and VlhA phenotypic diversity are important for persistence of M. gallisepticum in the host. Notably, changes in sugar metabolism and solute transport functions were apparent in both attenuated strains, indicating that metabolic substrate utilization may be a significant mechanism by which strains exhibit phenotypic differences in the host. While genes involving metabolism, proteolysis, and restriction-modification were predicted to be compromised in attenuated strains, other potential virulence determinants included genes with no or nonspecific functional prediction and thus of interest for further characterization. We proceeded to characterize one such gene by demonstrating reduced tracheal lesions in chickens infected with an isogenic mutant of the MGA_1107 gene. CGH analysis identified few common genes missing or divergent in vaccine strains F, ts-11, and 6/85, indicating that no single gene was likely responsible for their attenuation. This supports the notion that M. gallisepticum pathogenesis is complex, multifaceted, and multigenic, consistent with these and previous results indicating that independent genes may be essential for virulence. The comparative genomic analysis presented here point to additional factors potentially critical for colonization and virulence in the host, and it provides the framework essential for the rational design of future vaccines.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Amy Gates for necropsy assistance, Kevin Kavanagh for animal care, and Ione Jackman and Denise Long-Woodward for tissue processing and histological preparation.

This work was supported by USDA grant 58-1940-5-520.

Editor: A. Camilli

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 1 February 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://iai.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abadjieva, A., J. Patel, M. Webb, V. Zinkevich, and K. Firman. 1993. A deletion mutant of the type IC restriction endonuclease EcoR1241 expressing a novel DNA specificity. Nucleic Acids Res. 21:4435-4443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abd-el-Motelib, T. Y., and S. H. Kleven. 1993. A comparative study of Mycoplasma gallisepticum vaccines in young chickens. Avian Dis. 37:981-987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altschul, S. F., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Myers, and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bamford, C. V., J. C. Fenno, H. F. Jenkinson, and D. Dymock. 2007. The chymotrypsin-like protease complex of Treponema denticola ATCC 35405 mediates fibrinogen adherence and degradation. Infect. Immun. 75:4364-4372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bearson, S. M., S. D. Collier, B. L. Bearson, and S. L. Branton. 2003. Induction of a mycoplasma gallisepticum pMGA gene in the chicken tracheal ring organ culture model. Avian Dis. 47:745-749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bischof, D. F., C. Janis, E. M. Vilei, G. Bertoni, and J. Frey. 2008. Cytotoxicity of Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. mycoides small colony type to bovine epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 76:263-269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cecchini, K. R., T. S. Gorton, and S. J. Geary. 2007. Transcriptional responses of Mycoplasma gallisepticum strain R in association with eukaryotic cells. J. Bacteriol. 189:5803-5807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chevreux, B., T. Wetter, and S. Suhai. 1999. Genome sequence assembly using trace signals and additional sequence information, p. 45-56. In R. Giegerich et al. (ed.), Proceedings of the German Conference on Bioinformatics. GBF-Braunschweig and University of Bielefeld, Bielefeld, Germany.

- 9.Delcher, A. L., D. Harmon, S. Kasif, O. White, and S. L. Salzberg. 1999. Improved microbial gene identification with GLIMMER. Nucleic Acids Res. 27:4636-4641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evans, R. D., and Y. S. Hafez. 1992. Evaluation of a Mycoplasma gallisepticum strain exhibiting reduced virulence for prevention and control of poultry mycoplasmosis. Avian Dis. 36:197-201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ewing, B., L. Hillier, M. C. Wendl, and P. Green. 1998. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. I. Accuracy assessment. Genome Res. 8:175-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gates, A. E., S. Frasca, A. Nyaoke, T. S. Gorton, L. K. Silbart, and S. J. Geary. 2008. Comparative assessment of a metabolically attenuated Mycoplasma gallisepticum mutant as a live vaccine for the prevention of avian respiratory mycoplasmosis. Vaccine 26:2010-2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaurivaud, P., J. L. Danet, F. Laigret, M. Garnier, and J. M. Bove. 2000. Fructose utilization and phytopathogenicity of Spiroplasma citri. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 13:1145-1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glew, M. D., N. Baseggio, P. F. Markham, G. F. Browning, and I. D. Walker. 1998. Expression of the pMGA genes of Mycoplasma gallisepticum is controlled by variation in the GAA trinucleotide repeat lengths within the 5′ noncoding regions. Infect. Immun. 66:5833-5841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glew, M. D., G. F. Browning, P. F. Markham, and I. D. Walker. 2000. pMGA phenotypic variation in Mycoplasma gallisepticum occurs in vivo and is mediated by trinucleotide repeat length variation. Infect. Immun. 68:6027-6033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goh, M. S., T. S. Gorton, M. H. Forsyth, K. E. Troy, and S. J. Geary. 1998. Molecular and biochemical analysis of a 105 kDa Mycoplasma gallisepticum cytadhesin (GapA). Microbiology 144:2971-2978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gordon, D., C. Abajian, and P. Green. 1998. Consed: a graphical tool for sequence finishing. Genome Res. 8:195-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gorton, T. S., and S. J. Geary. 1997. Antibody-mediated selection of a Mycoplasma gallisepticum phenotype expressing variable proteins. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 155:31-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gumulak-Smith, J., A. Teachman, A. H. Tu, J. W. Simecka, J. R. Lindsey, and K. Dybvig. 2001. Variations in the surface proteins and restriction enzyme systems of Mycoplasma pulmonis in the respiratory tract of infected rats. Mol. Microbiol. 40:1037-1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halbedel, S., C. Hames, and J. Stulke. 2004. In vivo activity of enzymatic and regulatory components of the phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system in Mycoplasma pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 186:7936-7943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halbedel, S., C. Hames, and J. Stulke. 2007. Regulation of carbon metabolism in the mollicutes and its relation to virulence. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 12:147-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hames, C., S. Halbedel, M. Hoppert, J. Frey, and J. Stulke. 2009. Glycerol metabolism is important for cytotoxicity of Mycoplasma pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 191:747-753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayflick, L. 1965. Tissue cultures and mycoplasmas. Tex. Rep. Biol. Med. 23(Suppl. 1):285+. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang, X., and A. Madan. 1999. CAP3: A DNA sequence assembly program. Genome Res. 9:868-877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hudson, P., T. S. Gorton, L. Papazisi, K. Cecchini, S. Frasca, Jr., and S. J. Geary. 2006. Identification of a virulence-associated determinant, dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase (lpd), in Mycoplasma gallisepticum through in vivo screening of transposon mutants. Infect. Immun. 74:931-939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ishihara, K., H. K. Kuramitsu, T. Miura, and K. Okuda. 1998. Dentilisin activity affects the organization of the outer sheath of Treponema denticola. J. Bacteriol. 180:3837-3844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jenkins, C., S. J. Geary, M. Gladd, and S. P. Djordjevic. 2007. The Mycoplasma gallisepticum OsmC-like protein MG1142 resides on the cell surface and binds heparin. Microbiology 153:1455-1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jenkins, C., R. Samudrala, S. J. Geary, and S. P. Djordjevic. 2008. Structural and functional characterization of an organic hydroperoxide resistance protein from Mycoplasma gallisepticum. J. Bacteriol. 190:2206-2216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karlsson, C., M. L. Andersson, M. Collin, A. Schmidtchen, L. Bjorck, and I. M. Frick. 2007. SufA—a novel subtilisin-like serine proteinase of Finegoldia magna. Microbiology 153:4208-4218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khan, M. I., K. M. Lam, and R. Yamamoto. 1987. Mycoplasma gallisepticum strain variations detected by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Avian Dis. 31:315-320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kosinski, J., M. Feder, and J. M. Bujnicki. 2005. The PD-(D/E)XK superfamily revisited: identification of new members among proteins involved in DNA metabolism and functional predictions for domains of (hitherto) unknown function. BMC Bioinformatics 6:172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kurtz, S., J. V. Choudhuri, E. Ohlebusch, C. Schleiermacher, J. Stoye, and R. Giegerich. 2001. REPuter: the manifold applications of repeat analysis on a genomic scale. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:4633-4642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lagesen, K., P. Hallin, E. A. Rodland, H. H. Staerfeldt, T. Rognes, and D. W. Ussery. 2007. RNAmmer: consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:3100-3108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levisohn, S., J. R. Glisson, and S. H. Kleven. 1985. In ovo pathogenicity of Mycoplasma gallisepticum strains in the presence and absence of maternal antibody. Avian Dis. 29:188-197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levisohn, S., R. Rosengarten, and D. Yogev. 1995. In vivo variation of Mycoplasma gallisepticum antigen expression in experimentally infected chickens. Vet. Microbiol. 45:219-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lieu, P. T., P. Jozsi, P. Gilles, and T. Peterson. 2005. Development of a DNA-labeling system for array-based comparative genomic hybridization. J. Biomol. Tech. 16:104-111. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lima, T., A. H. Auchincloss, E. Coudert, G. Keller, K. Michoud, C. Rivoire, V. Bulliard, E. de Castro, C. Lachaize, D. Baratin, I. Phan, L. Bougueleret, and A. Bairoch. 2009. HAMAP: a database of completely sequenced microbial proteome sets and manually curated microbial protein families in UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot. Nucleic Acids Res. 37:D471-478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lin, M. Y., and S. H. Kleven. 1981. Pathogenicity of two strains of Mycoplasma gallisepticum in turkeys. Avian Dis. 26:360-364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu, T., M. Garcia, S. Levisohn, D. Yogev, and S. H. Kleven. 2001. Molecular variability of the adhesin-encoding gene pvpA among Mycoplasma gallisepticum strains and its application in diagnosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:1882-1888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lowe, T. M., and S. R. Eddy. 1997. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:955-964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Markham, P. F., M. D. Glew, G. F. Browning, I. D. Walker, and K. G. Whithear. 1996. Antibody influences expression of pMGA1 of Mycoplasma gallisepticum. IOM Lett. 4:114-115. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Markham, P. F., M. D. Glew, G. F. Browning, K. G. Whithear, and I. D. Walker. 1998. Expression of two members of the pMGA gene family of Mycoplasma gallisepticum oscillates and is influenced by pMGA-specific antibodies. Infection Immun. 66:2845-2853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Markham, P. F., M. D. Glew, K. G. Whithear, and I. D. Walker. 1993. Molecular cloning of a member of the gene family that encodes pMGA, a hemagglutinin of Mycoplasma gallisepticum Infect. Immun. 61:903-909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.May, M., L. Papazisi, T. S. Gorton, and S. J. Geary. 2006. Identification of fibronectin-binding proteins in Mycoplasma gallisepticum strain R. Infect. Immun. 74:1777-1785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miyamoto, M., K. Ishihara, and K. Okuda. 2006. The Treponema denticola surface protease dentilisin degrades interleukin-1 beta (IL-1 beta), IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor alpha. Infect. Immun. 74:2462-2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mudahi-Orenstein, S., S. Levisohn, S. J. Geary, and D. Yogev. 2003. Cytadherence-deficient mutants of Mycoplasma gallisepticum generated by transposon mutagenesis Infect. Immun. 71:3812-3820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Murray, N. E. 2000. Type I restriction systems: sophisticated molecular machines (a legacy of Bertani and Weigle). Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64:412-434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Noormohammadi, A. H., P. F. Markham, M. F. Duffy, K. G. Whithear, and G. F. Browning. 1998. Multigene families encoding the major hemagglutinins in phylogenetically distinct mycoplasmas. Infect. Immun. 66:3470-3475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Noormohammadi, A. H., P. F. Markham, A. Kanci, K. G. Whithear, and G. F. Browning. 2000. A novel mechanism for control of antigenic variation in the haemagglutinin gene family of Mycoplasma synoviae. Mol. Microbiol. 35:911-923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nunoya, T., M. Tajima, T. Yagihashi, and S. Sannai. 1987. Evaluation of respiratory lesions in chickens induced by Mycoplasma gallisepticum Nippon Juigaku Zasshi 49:621-629. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Papazisi, L., S. Frasca, Jr., M. Gladd, X. Liao, D. Yogev, and S. J. Geary. 2002. GapA and CrmA coexpression is essential for Mycoplasma gallisepticum cytadherence and virulence. Infect. Immun. 70:6839-6845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Papazisi, L., T. S. Gorton, G. Kutish, P. F. Markham, G. F. Browning, D. K. Nguyen, S. Swartzell, A. Madan, G. Mahairas, and S. J. Geary. 2003. The complete genome sequence of the avian pathogen Mycoplasma gallisepticum strain R(low). Microbiology 149:2307-2316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Papazisi, L., L. K. Silbart, S. Frasca, Jr., D. Rood, X. Liao, M. Gladd, M. A. Javed, and S. J. Geary. 2002. A modified live Mycoplasma gallisepticum vaccine to protect chickens from respiratory disease. Vaccine 20:3709-3719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Papazisi, L., K. E. Troy, T. S. Gorton, X. Liao, and S. J. Geary. 2000. Analysis of cytadherence-deficient, GapA-negative Mycoplasma gallisepticum strain R. Infect. Immun. 68:6643-6649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pearson, W. R., and D. J. Lipman. 1988. Improved tools for biological sequence comparison. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 85:2444-2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pearson, W. R., T. Wood, Z. Zhang, and W. Miller. 1997. Comparison of DNA sequences with protein sequences. Genomics 46:24-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pilo, P., E. M. Vilei, E. Peterhans, L. Bonvin-Klotz, M. H. Stoffel, D. Dobbelaere, and J. Frey. 2005. A metabolic enzyme as a primary virulence factor of Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. mycoides small colony. J. Bacteriol. 187:6824-6831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Razin, S., D. Yogev, and Y. Naot. 1998. Molecular biology and pathogenicity of mycoplasmas. Microbiol Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:1094-1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rice, P., I. Longden, and A. Bleasby. 2000. EMBOSS: the European Molecular Biology Open Software Suite. Trends Genet. 16:276-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rottem, S., and S. Razin. 1969. Sugar transport in Mycoplasma gallisepticum. J. Bacteriol. 97:787-792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rouquet, G., G. Porcheron, C. Barra, M. Reperant, N. K. Chanteloup, C. Schouler, and P. Gilot. 2009. A metabolic operon in extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli promotes fitness under stressful conditions and invasion of eukaryotic cells. J. Bacteriol. 191:4427-4440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shen, X., J. Gumulak, H. Yu, C. T. French, N. Zou, and K. Dybvig. 2000. Gene rearrangements in the vsa locus of Mycoplasma pulmonis. J. Bacteriol. 182:2900-2908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Siezen, R. J., B. Renckens, and J. Boekhorst. 2007. Evolution of prokaryotic subtilases: genome-wide analysis reveals novel subfamilies with different catalytic residues. Proteins 67:681-694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sitaraman, R., and K. Dybvig. 1997. The hsd loci of Mycoplasma pulmonis: organization, rearrangements and expression of genes. Mol. Microbiol. 26:109-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Slupska, M. M., J. H. Chiang, W. M. Luther, J. L. Stewart, L. Amii, A. Conrad, and J. H. Miller. 2000. Genes involved in the determination of the rate of inversions at short inverted repeats. Genes Cells 5:425-437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sonnhammer, E. L., and R. Durbin. 1995. A dot-matrix program with dynamic threshold control suited for genomic DNA and protein sequence analysis. Gene 167:GC1-GC10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sorek, R., V. Kunin, and P. Hugenholtz. 2008. CRISPR—a widespread system that provides acquired resistance against phages in bacteria and archaea. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6:181-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Taylor, R. R., K. Mohan, and R. J. Miles. 1996. Diversity of energy-yielding substrates and metabolism in avian mycoplasmas. Vet. Microbiol. 51:291-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Thomas, C. B., P. Sharp, B. A. Fritz, and T. M. Yuill. 1991. Identification of F strain Mycoplasma gallisepticum isolates by detection of an immunoreactive protein. Avian Dis. 35:601-605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]